Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 116

October 14, 2021

God was everywhere in the street

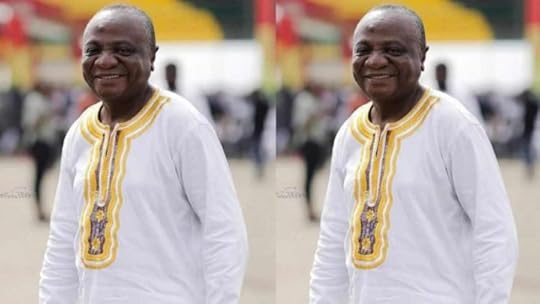

Nana Kwame Ampadu. Image via Twitter.

Nana Kwame Ampadu. Image via Twitter. On June 21, 2007, I arrived at a compound house in La Paz, a suburb of Accra, Ghana. A relatively modest house, it was the home to Nana Ampadu, international recording artist and highlife legend, who died last week. As the Ghanaian guitarist Kyekyeku recounted in an Instagram memorial, ���3 decades ago Nana Ampadu declared that he wanted to make his music his ���own way��� at a time when the musical landscape was fast changing and the dose of ���foreign��� elements and influences was overwhelming.��� As the leader of the African Brothers Band, which was formed in 1963 and became known as the ���Beatles of Ghana,��� Ampadu went on to write more than 400 songs in his decades-long career. Ampadu was recognized as Nwontofohene (Singer-in-Chief) by the government of Ghana�� in 1973. In the interview below, which is excerpted from a longer interview conducted as part of dissertation research on the history and culture of driving in Ghana, Ampadu discusses his experience as a musician in the tumultuous 1980s and 1990s, and we talk about the role religion played in the public sphere of our respective countries during that time. I began by asking him about his 1983 hit song, ���Driver Adwuma��� (or ���Driver���s Work��� or Adwuma Yi Ye Den (Drivers) [���This Work is Hard���], popularly known as ���Drivers���).

Jennifer HartYeah, we were talking about your song [���Driver Adwuma���]. You said it was released in 1983, but you started in 1977, starting to collect the songs?

Nana AmpaduYeah, I started [in] 1977. I said, I want to sing about drivers���the inscriptions on their cars. Because when you read some of them, they are very entertaining. Some of them are thought provoking. Some of them are insinuating ��� writings. Some of them, you will laugh, you know? So, I said, no, I can make music out of this. So what I will do is I will start to collect the inscriptions. And it took me six good years before I could come out. I got about 140 plus, and I seek them. I scribed through and picked those others that I felt ���

Jennifer HartThe 70 that you thought were good. Yeah.

Nana AmpaduYeah, so it was 70. If you have got the record, read it and you see it. Thirty-five for the old cars, and 35 for the new [laughing]. It became so popular and it is still popular���still people buy it. It���s not forgetting because it was the first of its kind in the country. Nobody has, you know, come out with such a beautiful piece.

Jennifer HartYou���ve started a new one? ��� For your new song?

Nana AmpaduUh huh. For the new song, but for the drivers, this time to advise them, their behavioral attitude, how they must behave. When they are entering the main road, they have to stop and look and then I will add their inscriptions as I did with the first one.

Jennifer HartAha, I see. So me, um, I see a lot more religious ones from what people have told me before … So now you see a lot of ���My God is Able��� and ���God is King��� and ���God First��� and ���Onyame Adom��� and ���Nyame Nhyira wo.���

Nana AmpaduYeah, some of them are sung in Ewe …�� In Ga, ���L��l��ny��.��� That is the Mantse [chief].

Jennifer HartYeah, and ���Abedi��� and ���Abele.���

Nana Ampadu���Abele.��� ���Abele��� means ���corn.���

Jennifer HartYeah, and there was one in Arabic or something as well. ���Aquay Allah,��� or something ���

Nana Ampadu���Acquay Allah,��� that is Hausa. ���Acquay Allah,��� meaning [God exists]. You may not see it today on [a] car.�� ��� Things are changing.�� ��� On what they want to write. ��� These times, if you don���t go to the hinterlands, you���re not going to see inscriptions like ���Obi dea ba.��� You get it? Those letters that portray wretchedness. In the cities these young boys will not write anything that will deprive ��� no! ��� demoralize ��� no! ����� ��� a little. But in the villages you can still have some of those cars.

Jennifer HartEven when they have old cars now, I met a boy, a young man, who was driving a car, an old car and it said ���Destiny,��� and he told me that he was so confident that he was going to do better things. He said, ���Today I may be here, but tomorrow, you don���t know. I may be teaching at the university or something.��� And so, I think, even when they have the old cars now they still ��� they want to be confident in their future, and they think God helps them get it.

Nana AmpaduIn those generations, that was the tyranny in the system. You know, we could feel, poverty was an element of havoc. You see? People tempted those who were poor. And so they had some consolation to write �����nye se ano mu, eye.����� Don���t expect that you will see me in these tattered clothes in the next future.

Jennifer HartBut now they don���t like to admit that they have the tattered clothes to start with?

Nana AmpaduYeah. Now Christianity is unfolding everywhere. That is what���s changing the minds of the people. They���re getting a new perception���a perception of positiveness. Unlike their old times where people would be brooding over life.

Jennifer HartAnd now because of Christianity they think that things will get better …

Nana AmpaduThey think, they���re teaching talk better for yourself and it will happen because you expect it. You get it? Talk better things. Like the one who wrote, ���Destiny��� and he was telling you, ���Maybe today you will see me, I���m a driver���s mate, but next time you see me a teacher. A step forward in the right direction in life.

Jennifer HartUm, yeah, it���s similar to some of the preachers who say, you know, they like this ��� they call it ���Gospel of Prosperity,��� and so they say if you believe then you will be rewarded. You will be prosperous, you will succeed.

Nana AmpaduSo you collected the names of the churches also?

Jennifer HartYeah, I���ve had some of the names of the churches, yeah. The new Pentecostal ones, the charismatic ones. Those are the ones that are the most interesting I think.

Nana AmpaduMy church is, um, you know I���m an evangelist? They told you? ����� Center for Christ Mission.

Jennifer HartYeah, and so do you sing anymore or no? You sing in your church?

Nana AmpaduI sing in my church. I sing at big funerals, big functions. Yeah, this year when we had the 50th independence I was drawn up with other prominent musicians, yeah, to sing at a concert. A very big concert for dignitaries. And we were given some awards.

Jennifer HartBut you ��� choose to go sing gospel music after you stopped the highlife?

Nana AmpaduNo, [I went to perform] highlife ��� let me tell you one thing. People misconstrue and have a different conception of what is highlife. Highlife is the rudiments of rhythms in Ghana, you see? Highlife is Ghana, when you talk about music. Highlife is the beat, so you can sing the secular music using the highlife tempo, like America is for jazz. You can sing gospel with jazz, you can sing secular with jazz, but people don���t understand it. The moment you sing secular, they say you are playing highlife while somebody sings and says ���Oh Lord, I love you!��� They play it with the highlife rhythm, they will say it is gospel and forget about mentioning highlife. The highlife is the tempo, the recognized tempo, the indigenous tempo of Ghanaians.

Jennifer HartSo you’re an evangelist and a musician at the same time?

Nana AmpaduYeah, the meeting [connection between the two���being an evangelist and a musician] is an inborn kind of thing. The other day I was telling people, in music you can say I���m going for a timing. It���s not like government officials when they will just check your age and say you are 55, you are 60, go on retirement. Dr. Ephraim Amu retired when he was about 85. He was still a musician when he died.

Jennifer HartIt���s true, yeah. Very true. So, as a preacher, what do you think of these ��� or an evangelist���sorry���what do you think of these people now and the new kinds of signboards you see on the taxis?

Nana AmpaduMost of them are good. I mean, comparing to the old times. Except that some of them are coined ��� some of them are coining ��� coinages, you know? Innuendos. They just wrote ��� coined them themselves, but most of the other writings or inscriptions are very healthy. Reading that ��� they use to mention God, it encourages a lot of people. You get it? You see, I saw one of them said ���Jehovah will do it.��� You see? It���s encouraging. God will do it, so it���s not daunting. I like them! That���s why I said I want to repeat it.

Jennifer HartAnd so what will the new song talk about? Because in the first song you talk about how a driver���s life is ���

Nana AmpaduThe tiresomeness of driving. You know, how the passengers would come and infuriate the driver ��� certain pedigree. But now ���

Jennifer HartYeah, if you go too fast they say, ���Oh, where are you going that you have to go so fast!?��� But if you go too slow, they say ���Oh, do you want us to sleep in the road?���

Nana AmpaduYeah, so I want to advise the drivers on their mode of ethics���driver errors���I want to tell them so that when they want to enter the major roads, you look your right side first, look your ��� before you enter. Driver, the country loves you. If you know you are drunk, don���t drive. And then I will coin and add their writings. To make them happy. And this one I���m going to do.

Jennifer HartSo is there a particular reason why you were interested in taxis? Because I look at the ��� there���s also the signboards on the lorries and the trotros [privately-owned minibuses that serve as the primary mode of transportation in Accra] and the shops there ��� In the hinterlands we had the old lorries so most of the old ��� the wretched ones ��� The Bedfords?

Nana AmpaduNo, the ���Wretched Ratchets��� were the old lorries like ���Obi dea ba,��� ���Dwene wo ho,��� ���Onyame nae,��� some ���ebeye yie,��� ���yesi ��nom eye��� ��� all were on lorries. Mammy truck ��� we call them mammy truck lorries where the woman sat in to go to market places.

Jennifer HartThe [signs] were not on shops?

Nana AmpaduYeah, some of them were on shops. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Like ���Onyame nnae,��� ���ebeye yie.����� Most of them were on shops. ���God is King��� ��� you���ll find some on shops.

Jennifer HartI think it is interesting because people don���t often put them on private cars. So you don���t put it on your own car or your own house or these things. Often they ���

Nana AmpaduFew private cars now have them ��� But in our days they were very minute, but now you can see, most of these young boys, as I was telling, they will coin a name like ���Sakota��� or ��� ���Tola,��� ���Big Boy��� ���

Jennifer HartYeah, ���Binghi Man,��� I saw ���Binghi Man.���

Nana AmpaduDo you see this in America?

Jennifer HartNo, see, we don���t have this, so this is why I think it is so interesting. Because people come ��� when I came to Ghana the first time, the thing I noticed was all the signboards about religion, about God ��� everywhere. All around. All in the street. God was everywhere in the street. You get me? So, we don���t have that in US. You don���t ��� so, people are even surprised when they see a billboard that has the Ten Commandments on it and there are a few of those on the side of the road. Very few. But you don���t see the writing on cars in this way. And painting on the cars and, um, shop names, the shop names tend not to be religious, but in Ghana there���s so many ���

Nana AmpaduSo do you think that religion in America is minute? In some of the states?

Jennifer HartUm, I think it is just different. So I think that people understand or ��� experience religion differently and maybe think about it differently.

Nana AmpaduAnd they don���t like to express it in public.

Jennifer HartYeah, it���s private.

Nana AmpaduYou express it within.

Jennifer HartIt���s a private thing. It���s like the missionaries used to tell you that ��� they used to preach that religion is a matter of your personal salvation. It���s not about ���

Nana AmpaduBut when I was in America, I saw that before I could study America I had the same perception, you know, like many Ghanaians, that when I went to America, I saw many TV channels that were religious channels.

Jennifer HartYeah, it���s true. It���s very true.

Nana AmpaduAnd there were a lot of people. I mean, they preach to people on the TV, so I say, ���Oh, so these people, they understand God.” You know, when we were in Africa we thought that America was just a helpful paradise [laughing]. I was so sorry about that thing. So when I came back, I was telling them.

Jennifer HartMany people go to church. It���s true! Yeah, and there���s many big churches just like in Ghana.

Nana AmpaduSo is it the only African state that you have visited in your research? Have you gone to Nigeria and the other? They are all there ���

Jennifer HartI haven���t gotten to go to Nigeria, no.

Nana AmpaduNigeria, it���s worse!

Jennifer HartI have heard, yeah. Yeah, they tell me. [laughing] I���ve only been to Togo, so it���s not so much there. Because they���re Catholic there, you know. They don���t do these things. But I���ve been told by several other people ��� I know some people who do this work in Liberia.

Nana AmpaduOk.

Jennifer HartAnd also a bit in Nigeria from, like, the late 1980s, I guess. And they also collected slogans���they call them slogans���inscriptions from taxis. And, um, the ones in Nigeria, some of them were religious but not all of them.

Nana AmpaduOk.

Jennifer HartNot as many as are in Ghana now.

Nana AmpaduIn Nigeria there are some of them, when you go to the Yoruba area they use ��� most of them use their gods ��� the names of their gods on them, on their cars.

Jennifer HartYeah, the Onitshas.

Nana AmpaduYeah, I���ve been to Nigeria before. I toured there with my band a couple ��� about four times and we experienced all these kinds of things.

Jennifer HartI haven���t myself seen it. I only have this writing by this man, this Nigerian man who wrote about a similar thing ��� about the taxi inscriptions … He���s a�� ��� I don���t know if he���s an anthropologist or what … and then I met some people who work in Liberia. And they also said ��� they listed all these taxi slogans, taxi inscriptions, and I went up to them afterwards and I said, ���I study these ��� the religious ones in Ghana,��� and they said, ���Oh, in Ghana, of course they���re religious.” So, somehow Ghana is known to be so religious.

Nana AmpaduIn Ghana we are religious. Very, very religious, you know. We come to know ��� because of the missionary schools, you see, I myself was brought up in Anglican church. I grew with it. I was baptized in it. Like my compatriots, all of us. So the moment you come out as a Christian, when you get married and bring forth [children], automatically you won���t let your children go wayward. You will just bring them into it. And this is what we are missing. Whether we understand it or not, we have to let people know that we are Christians. We have it there. Unlike in America where somebody will worship in his heart that you won���t display it. But here somebody will display that he is a Christian, but his ways are opposite of what is expected, you know. Opposite the norms and values of the Christians. But he just goes to the church to let people know that he knows God.

Jennifer HartRight, but I wonder because people talk about how in Ghana and Nigeria the religion is so much more than in some place like maybe Kenya or South Africa or Zimbabwe where they also had mission schools and ��� and yet somehow religion didn���t become quite as popular as it did in Ghana and Nigeria.

Nana AmpaduYeah, well maybe that is our style. The way we want to make it. Like, let���s go off a bit and [compare it to] soccer. In Britain [soccer is] their most popular game, but when you go to [the US], it���s not their religion, … soccer.�� They have a different [relationship to soccer] ��� So [with religion] this is how Ghanaians, they want to take it, ok? It���s good with us.

Jennifer HartYeah. Do you see an increase in the number of religious signboards and inscriptions or do you see the same number?

Nana AmpaduOh, every time! Every time, it���s springing up! Every time! No, the rate, it���s being accelerated. Yeah! Every time.

Jennifer HartAh, why do you think that may be?

Nana AmpaduUh ��� let me take it to the first ��� the attribution of spiritualism. You know, nobody knows how God works with his people, but the other time I was interviewing on radio and I said, when you hear that a church has sprung up from another church, don���t get annoyed. Because there���s somebody over there where the new church is going who hasn���t repented yet. And so maybe through that church ��� because he might be a deprived person ��� he can���t take a car or walk all that the long way to visit a church, but when it���s at his doorstep, I think he can get it. The access to get there will be easier. So, that alone is another way to promote the Christianity. So it���s good. I���m not saying I fully support it, but it���s good for God. That is why it is springing up.�� Unlike Muslim ��� even the Muslims have even started. Formerly, when we got this land in 1978, we had only one church, one ��� mosque. But now, just this area, we have about six. You see, so they too, they are springing up.

Hear more from Nana Ampadu in this recorded interview.

Read the full text of the interview in this blog post.

Africans and the creation of the modern world

Elmina, Ghana, in 2018. The invading Portuguese erected a castle there in 1492, the first trading post built on the Gulf of Guinea, and the oldest European building in existence south of the Sahara. Credit Konrad Lembcke via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

Elmina, Ghana, in 2018. The invading Portuguese erected a castle there in 1492, the first trading post built on the Gulf of Guinea, and the oldest European building in existence south of the Sahara. Credit Konrad Lembcke via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. In early September 2021, a statue of Robert E. Lee, who fought on the losing confederate side of the American Civil War, was taken down in Richmond Virginia, the former capital of the confederacy. Lee had good company. Two months earlier, in Sao Paulo, protestors set fire to the statue of Borba Gato, a seventeenth century Portuguese ���fortune hunter,��� who enslaved indigenous Brazilians. A statue of Belgium���s King Leopold II in Antwerp had a similar fate. From Colombia to New Zealand, South Africa to France, statues, busts, plaques, and other memorials tied to the history of enslavement and colonization have been pulled down. In Born in Blackness, (to be published on October 12 by Norton) Howard French, career foreign correspondent and former New York Times bureau chief in the Americas, Africa, and Asia scrutinizes the received history of ���the West.��� He fills in crucial gaps and pulls down the assumptions, narratives, and myths that exclude Africans and Africa from the formation of the modern world. I spoke to French about this and other themes from his book. The conversation has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Anakwa DwamenaThis book challenges the common narrative of the historical relationship between Europe and Africa. Particularly the idea that European nations were presumptively somehow always superior to their African counterparts���whether in wealth, scientific knowledge, state power, or technology. I was struck by a point you make, that the high demand for guns from the African states for instance, actually fueled and ultimately led to Europe���s mastery of the technology.

Howard FrenchMost of what we’re taught about African history and indeed about the history of the modern era, and the history of the Atlantic world, completely skips this era. This is one of the primary motivations of writing a book about this. I make the argument that the main reason for the creation of the modern world, as we understand it, and for Europe’s separation, politically and economically from other previously more powerful parts of the world, is not the complex of Judeo-Christian ideas or work ethic, or even the scientific method. I don’t say that because I don’t think those weren’t important things. But that’s all we heard for the last 500 years, and in such a way that it smothers out everything else. So much that we have lost sight of what is hiding in plain sight, which is that it was the expropriation of billions and billions of man hours of African labor, and the seizure and expropriation of square miles of territory, in the so called New World, that gave the West the wherewithal that forms the very basis of the creation of the West���by which I mean the condominium between Europe and the New World.

The creation of the West would have been utterly impossible, unthinkable without the expert expropriation of these billions and billions of man hours of labor. I go into some degree of detail about not just the crude creation of wealth and power in Europe’s ascent, but the impact of all of this on European society and culture and on English first and then British society and culture. Especially first and foremost, in the period prior to the Industrial Revolution, in which I say for example, the impact of all of these cheap calories that were derived from African labor in the New World, revolutionized the English and subsequently the European diet and gave English workers and subsequently other European workers caloric basis to increase their productivity. New crops in great quantities like coffee, and cocoa, a bit later tea, together with sugar, which is the most important economic product of this entire era. They change the culture of civic discourse, because of the creation of the coffee shop which is an outgrowth of African slave labor. Africans grew the coffee. Africans grew the sugar that made the coffee palatable. Newspapers thrives in the coffee shop because for the first time you have a captive audience of people who instead of being drunk in a tavern are sitting around drinking stimulants, and a culture of discussion of the affairs of the day based on published information known as the newspaper takes root for the very first time.

Anakwa DwamenaHow did you embark on this in the first place?

Howard FrenchIt’s really a combination of things. The first is a remarkable coincidence that I have worked in prolonged ways in so many parts of the world that serve as the backdrop for this history. So I would have to have been a pretty insensitive person not to have begun to try to stitch a big picture together. I also spent more than a decade working in East Asia, and one of the mostly silent, but ever present sentiments or ideas that runs through society has to do with Asia’s relationship to the West. Why is it that the West became ascendant in the time that it did? Especially vis-a-vis East Asia, whose civilizations are older. What brought that about? What was innate to Western versus Eastern civilization? How much of this was foreordained? How much of it is fated to be semi-permanent or much longer lasting? Because it was in the air everywhere I went in Asia, it helped jar me, or jostle some of the big picture questions I had about the Atlantic world that that were partly an outgrowth of my personal experience, and got me to think in long timescale historical terms about how it happened that the West rose the way it did. When I scratched around the story of Africa’s role in this, I saw that having Africa or Africans turns out to have been the primary reason why Europe and subsequently what we call the West, came to be ascendant over the East. The East didn’t have a continent whose resources, both natural and human, it could train to its own purposes. It only had its own resources and its own labor. I say that if Europe had not had the benefit of [Africa���s] natural resources, and then subsequent centuries of African labor, Europe would have been a marginal player in world history in the era that’s under discussion. I don’t mean to say Europeans had no talents or no qualities, or that they wouldn’t have had their own fair share of achievements.

Anakwa DwamenaWithout this drain of natural resources and labor, what level of development would you imagine the African continent could have been capable of?

Howard FrenchAlright, so this is a question that fascinates me, and that I first began to explore in my very first book, A Continent for the Taking. We can’t really say with certainty with big picture counterfactuals, how things would have worked out. There’s just too much complexity involved. But a couple of things stand out to me. One of them is that Africa in the early Middle Ages, or in the late Middle Ages, and in the early modern era, was in the process of quite advanced state formation in some places. Kingdoms in present day Ghana, Nigeria, what is commonly called Sudanic Africa, were among them. The other big example is Kongo, spelled with a K. The counterfactual answer to your question that seems most persuasive to me is that if Africa had not had the accidental history of the 15th and 16th century, where by the Portuguese and then subsequently other European powers, begin to engage south of the Sahara and to first trade for large quantities of gold, and then subsequently seduced African powers into the trade in slaves; if those things had not happened, Africa as a continent, especially the Atlantic part of the continent, would have been afforded much more time and space to advance or to continue this process of state formation. In the book I make a very detailed argument about the demographic impact of the slave trade. Here, I’m making a political argument that if Africa had been afforded more space and time in that critical era, then African states would have continued on their development and probably would have emerged much larger, extensive���geographically speaking���and more powerful and more capable, most importantly perhaps, of resisting or holding their ground, vis-a-vis European powers. If the contact had come later, one can imagine a scenario whereby maybe gun technology would have spread in Africa. Buying guns from other places, but maybe, also made in Africa as there were quite exquisite metalworking capabilities.

Anakwa DwamenaYou express surprise, on arrival at important historical sites whether in Ghana, or Barbados or the Canary Islands, at how little locals are aware of their own histories. What did this suggest to you about our current understanding of the world we live in?

Howard FrenchI talked about going to places like Barbados, which was the first place that Britain or, at the time England, initiated its plantation complex, and where extraordinary wealth starts to be produced from the fruits of African labor, being stunned by the absence in what is now and has been, for some time, an independent country, with a government run by people who are descendants of Africans. This created a shock of awareness in me. I’m American, and I’m deeply familiar with the lack of that very thing in my own society. I find that I later go to Brazil, the largest black population of any society outside of Africa and find the same phenomenon. I go to Ghana which played such a foundational role in the creation of the world, the world that is at the heart of my book and a society that, in the last 70 years, has played a foundational role in the creation of the modern politics of independence for Africa. But, even in Ghana, very little awareness of the beginning of the true nature of the beginnings of this world, very little public effort, at remembrance and of celebration and exploration of these ideas. This created a pain, and urgency, as a person of African descent, to speed up this excavation and to become more active in the digging up of this history, to become more willing to probe deeply into the past, or the beginnings of the modern age, and to cast off the very pat explanation about how we arrived at this moment. Erasure is mostly not an active, or certainly not a violent thing. It’s mostly a subliminal thing. African Americans have for centuries been taught versions of history that write their ancestors out of the picture. Through a series of images and archetypes that are present in literature, and advertising, and entertainment, and one thing after another, we have been subliminally induced to devalue ourselves, or our ancestors and their role in building the world that we all live in. So this notion that our ancestors might have played a really important role in building up the modern world is something that is building momentum. W.E.B. Du Bois started this a long time ago, but we’re only just now achieving some momentum, we’re excavating ourselves out of this deep hole where we ourselves as people of color, allow ourselves to be invested in understanding these stories and to reassess our own importance in the building of the world. And bring those stories to a broader public and force a reckoning with the broader public in terms of understanding that the modern world was not just built by Europeans, based on the most positive kinds of European values that we are all taught to celebrate, and to respect that a lot more was involved.

Anakwa DwamenaLet’s talk about Kongo with a K, which you spend quite some time on. It completely blew my mind, as a precolonial state that had longstanding, equal diplomatic relations with Europe and the Vatican until being undone by internal wars of succession.

Howard FrenchI first encountered this as a foreign correspondent working for The New York Times, covering the Mobutu period in then Zaire [after Mobutu was overthrown in 1997, a new government changed the name of the country to the Democratic Republic of the Congo]. And the story of this kingdom has been with me ever since in a haunting, persistent way. I discovered the correspondence between the king of Kongo, and the king of Portugal, and in it, the king of Kongo is more or less imploring the king of Portugal to suspend the slave trade. He’s saying to the king of Portugal: I thought we were brothers. But now, what’s happening is by the avarice of your people, you’re destroying my kingdom. And the king of Portugal replies, listen, that’s too bad. I’m terribly sorry. But people are the only thing that you have, and we wish to purchase them.

But when I got to work on this book, and dove into the archives, I discovered a much thicker history even than I had suspected back then. The Portuguese arrived in Kongo just a few years after they arrived in Elmina. When the Portuguese come ashore,�� it becomes clear and evident to the Kongolese that the Portuguese have as a religious symbol, the cross. Well, by extraordinary coincidence, it appears that the cross was already one of the most important religious symbols in the Kongolese religion at the time. So on this basis, the Kongolese are intrigued enough to be seduced into an initiation into Christianity. A church is built very quickly there. The Portuguese take a few Kongolese back to Europe,and train them in Portuguese. And then they visit the Kongolese capital. Political relations are established. All of the Kongolese royalty begin to learn Portuguese, become fluent in Portuguese language and literature, and use the Portuguese language as a means of mastering Christianity. The Kongolese King sends all kinds of envoys including his children to go to school and the children of other nobles to go to school in Europe. Kongolese priests begin to be ordained by the Catholic Church, and by the Vatican itself. There are bishops serving as representatives in the Vatican. They acquire an understanding of the statecraft of Portugal, and of other European countries. There’s no question whether or not the Portuguese could conquer these people. The Portuguese had no ability to project force in anything like the numbers that would have been required to conquer anybody.

Anakwa DwamenaReading this section, I couldn���t help but think about how a number of enslaved people came directly to the New World with firsthand experience in confronting European powers. You talk a bit about this too in the section on the Haitian Revolution.

Howard FrenchThis is another one of these powerful coincidences that make history so fascinating. The eventual success of the Haitian Revolution was probably in part helped by the fact that many of the Africans who were imported to Haiti, as enslaved peoples, in the 18th century came from areas in Africa that had advanced states involved in very complicated warfare. As the common received story of slavery in the West would have it, Africans had few qualities, except their being able to work in hot conditions bending over cropland, producing commodities for Europe. These Africans who came from nearby part of what is now Angola, and from places like Benin and Nigeria, and in Ghana, for example, all had experiences often directly of having been subjects of pretty advanced states. So they had an awareness of not just what it meant to be free as an individual, but to be part of a polity that was independent and self governed. On top of that, they had an experience in many of these examples, especially the ones I’ve just cited of Kongo, Angola, Benin, and Nigeria, places in Dahomey, for example, and in Ghana, of intense and highly organized warfare. They have really complicated ideas about how the world is made up, what it means to be a free person, and what it means to have your own polity and what it means to fight a war. So the French didn’t really know what they were getting into in that sense. When the Haitian Revolution came together, those capacities and experiences were a resource for people like Toussaint L’Ouverture, who was able to lead these black armies to extraordinary and history-making political victories against a series of white armies.

Anakwa DwamenaAny other themes or regions we haven���t touched on in the conversation that you would like to share a bit more about.

Howard FrenchI guess there’s one thing that we haven’t really talked about, and that is the history of the United States itself. We don���t learn about how the Haitian Revolution changed the course of American history. It made Napoleon, who had ambitions on many fronts desperate to liquidate his position in continental America. He sold the territory that comprises the Louisiana Purchase for a pittance, to the US, and essentially created a nearly continental sized country called the United States. Americans talk of the expansion to a continental sized country in terms of the pluck and the courage and willingness to conquer ���the untamed West.��� But this all begins with Haiti. Once this happens, the Mississippi River Valley becomes a site of economic exploitation on a very large scale by white people. These territories became the focus of cotton cultivation. And cotton cultivation, like sugar cultivation, was performed by black people, the descendants of people brought from Africa in chains. Cotton became, in a shockingly brief period of time, the world’s most important commodity, and the only commodity that other countries were basically desperate to buy from the US. It was the largest export of the US, incomparably greater than any other product from the beginning of the 19th century until the Civil War. That cotton, which was essential to England, and its industrial revolution, was produced by the descendants of people brought from Africa in chains, enslaved peoples, and so cotton in this era replaces sugar and is the most important factor in the driving of this ascension of the West and the rise of the US economically as a power. And the deepening of the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain.

Anakwa DwamenaYou argue for a reappraisal of the African���s role in the creation of modernity. What do you hope to see come out of engagement with this work?

Howard FrenchI think that we have an opportunity now to overcome something inflicted upon us, but also something that involves a degree of self-infliction. African Americans, for a very long time, have been disinclined to be deeply interested in Africa. In a previous era, we were actually encouraged to be disinterested in Africa, and to be furthermore ashamed of Africa, to seek to defer distance ourselves from Africa. By the same token, Africans have, through some strange process, felt it attractive to disclaim or express a disdain for members of the African diaspora. Especially African Americans. Yes, they can consume some of the culture here and there at the margin. But there’s this petty chauvinism that one can frequently come across. Where Africans talk about African Americans and people in other parts of the African diaspora as inferior or fundamentally different from them, or irrelevant to their lives. I say this is a self-inflicted wound, because it is so tragic. The greatest resource that Africans and Africans in the diaspora have is each other. Understanding their history, which is a common history, is the way to grasp that and to re-stitch a world that has more coherence to it. A world where we take a deeper understanding of the profound ways in which our histories have been intertwined. We share responsibility for the creation of everything you can point to in the world. And that is our product as much as it is of a Judeo Christian thing, or of a scientific method thing, or a Protestant work ethic thing, or any other thing that you can point to. For our own good, we need to come to that realization and begin to work across the ocean and build and restore those bridges. That is vital to reclaiming or restoring our proper place in each of these scattered parts of the Atlantic world, in the bigger, broader world together.

October 13, 2021

Growing pains

At the 2014 edition of Afropunk in Brooklyn, New York (J-No, via Flickr CC).

At the 2014 edition of Afropunk in Brooklyn, New York (J-No, via Flickr CC). This #ThrowbackThursday post was first published the South African newspaper, Mail and Guardian, in May 2017, when Afropunk first expanded to Johannesburg.

Afropunk comes to Johannesburg, all grown up. With that comes potential and grown-folk problems.

The festival has its origins in a 2003 film about the experiences of black punks in a mostly white music genre. It then morphed into a message board and a do-it-yourself music festival, and has since evolved into a colossal commercial attraction (a reputed 70���000 people attended last August���s two-day edition in Brooklyn, New York) with franchises in Paris, London, Atlanta and, as of December 2017, Johannesburg.

Organizers are cagey about defining Afropunk. It is a feeling, we are told. It is about agency, evolution, black people being weird, not having to explain themselves, ���part of my DNA��� (that���s neosoul singer Janelle Monae), energy, liberation, individuality, a culture, a movement, a festival. It means everything and nothing.

The crucial thing about Afropunk is that both its admirers and detractors have political expectations about it. That it is definitely not like mega-festivals such as Coachella, once dismissed as ���an oasis for douches and trust-fund babies���. It has something to do with where Afropunk started; the sense that its origins were associated with musical radicalism.

The neighborhood where I have lived for the past 16 years is the cradle of Afropunk. Fort Greene, a cluster of brownstones in Brooklyn, was a mecca of black creativity in the 1990s; at one point Spike Lee, Kara Walker, Chris Rock and Lorna Simpson lived here within a few blocks of one another.

But, particularly over the past decade, gentrification has transformed the neighborhood into an enclave of wine shops, ���farm to table��� restaurants, $20 burgers, pet spas and affluent white families.

High-rises and a branded sports arena have sprouted along its edges; the storied Albee Square Mall (immortalized in a 1988 song by Biz Markie) is now a slick, glass-walled building with fancy shops and a planned gourmet food hall. As the novelist Colson Whitehead���he used to live around the corner���wrote, sadly, of the new Fort Greene: ���Is it the death of Fort Greene? It���s the death of Fort Greene.���

The evolution of the Afropunk festival can���t be separated from this process. When it began in 2005, the audacity of a festival (it included film, skateboarding and stalls) that presented 21st-century black musicians and their fans in all their complexities���not just as neosoul singers, rappers or Daisy Age retreads���got everyone���s attention, including mine.

Behind the festival was James Spooner, the director of��Afropunk: The Movie��and Matthew Morgan, the film���s producer. It began at a local performance hall and spilled into the neighborhood���s streets and main park. I can���t remember whether the white neighbors complained about the color or the ���noise��� (the usual), but by 2008 Afropunk moved to the more working-class surroundings of Commodore Barry Park, at the edge of the neighborhood in the middle of a series of housing projects and under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Even as it was being pushed to the edges of the whitening, homogenizing neighborhood, though, Afropunk was beginning to exhibit 21st-century Fort Greene contradictions. In making the transition to a mainstream festival with huge sponsors, Afropunk seemed to leave its do-it-yourself, creative chaos behind.

It was also around this time that Spooner left the festival. As he told MTV: ���We will have succeeded when Afropunk is no longer relevant. Clearly we are not there yet, but I would like to believe that we are on our way. When that day comes, there will no doubt be a 14-year-old kid who flips off Afropunk and says, ���I���m starting my own thing���, and that���s what they should do.

���I think that���s the nature of scenes, and I wouldn���t be mad at them. I would be, like, ���Can I come to your show?���������

Spooner wasn���t talking about the future. He was talking about the then. Too many things were bothering him. At the 2008 show, he went on stage and publicly called out a band who did a cover of Buju Banton���s homophobic dancehall song,��Boom Bye Bye. To quote Spooner: ���Just because you play live instruments, doesn���t make you alternative.���

The organizers��� main role was to ensure that the festival was free; then they were thinking of charging people. That���s also around the time big commercial sponsors really began to make their presence felt. It was about matching ���market segments��� and ���audiences��� with advertisers and brands. ���Which do black youth prefer? The yellow or the red Mountain Dew?���

By last year Afropunk was charging an entry fee. Journalists did not search hard to find residents of the surrounding housing projects who deplored this: ���I wasn���t tryin��� to pay $85. If it was lower, we would have went. It���s too high,��� one man told��The��New Yorker.

Afropunk was now faced with the clich��d conundrum every independent artist or entity messing with capitalism has to face: How do you grow, make money and not lose your soul? It didn���t help that in 2010 CNN Money declared Afropunk ���the new counterculture���. It was like��The��New York Times declaring your neighborhood cool and happening���a clear sign that your neighborhood was cool about a decade ago.

But scaling up also brought other tensions. Over time, overwhelmingly most of the featured artists were already signed by major record labels; artists you could easily see at another festival such as Coachella: Janelle Monae, Ice Cube or Tyler the Creator (last year fans questioned his choice as a headline act, because of his homophobia). Every space is now plastered with company logos. What is so punk about that?

So is Afropunk now just a black Coachella? The quick answer is no. Coachella makes no political statement. Coachella is unabashedly commercial and owned by a right-wing billionaire who supports anti-LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual) and climate change-denying foundations and organizations. In any case, very few people expect radical politics from Coachella.

You could argue that an unfair burden is placed on black artists and festivals to be political. But then Afropunk���s creators set up that expectation themselves. People expect them to be ���woke���. (Remember when they removed M.I.A. as the main headliner from Afropunk London because of a perceived slight against #BlackLivesMatter?)

Since the criticism about Tyler the Creator, they have plastered the sides of stages with slogans: ���No Sexism. No Racism. No Ableism. No Ageism. No Homophobia. No Fatphobia. No Transphobia. No Hatefulness.���

This is affirming for many young black people. To give a personal example, when my now 11-year-old was in a mostly white preschool and was getting self-conscious about her thick, curly black hair, young black women in wild outfits constantly came up to her and told her she was beautiful.

So can Afropunk keep walking the line between a commercial festival and a punk affirmation of blackness?

To do so it will have to find new sources of creative energy. It could do that where it lands���finding and amplifying what might be Afropunk in those new cities. So far, the outlook on that front is not promising.

The organizing for Johannesburg may still improve but a marketing email blast sent out last weekend has little that one might recognize as ���punk���, and for local specificity reaches only for the kind of rainbow bromides that young black South Africans now challenge: ���Modern South Africa is proof of the victory of otherness over historical precedent, and of the country���s desire to mold a society based on virtues that are at the core of Afropunk.���

Young people in South Africa who take part in struggles such as #FeesMustFall, #RhodesMustFall and attempts to deracialize housing and public space in mostly white town centers and suburbs or that their public schools in townships are under-resourced will doubtless be surprised to discover that they are already victorious.

But then, for all the grief Afropunk gets, it still manages to bring people, mostly black, together over two days for a pretty great party.

Last year���s Afropunk in Brooklyn���the first one I missed���included a set by punk veterans Fishbone, Bad Brains and Living Color, joined by George Clinton of Parliament and Funkadelic, who brought down the house and pointed to new beginnings.

So there���s hope.

I might fly in for Afropunk Johannesburg when I hear they have invited The Genuines, South Africa���s greatest-ever punk band. But they may still surprise me.

Some kind of personal comfort

Of all the things we���ve lost in the COVID-19 pandemic, spontaneity is perhaps the easiest to overlook. Compared to loss of life, of income, health or home, the freedom to engage with life on an impromptu basis seems almost frivolous. And yet that is where so many of life���s small joys are found, and when the spur of the moment lies dulled and blunted from underuse, we yearn for the sharpening whetstone of free impulse.

With After The Night, The Day Will Surely Come, South African jazz pianist and composer Kyle Shepherd has wrought an antidote to despair, and a contemplation of hope, and the album sprung from a moment of desperate, defiant spontaneity in the depths of lockdown. ���I just sat down and played,��� says Shepherd.

���I went into the studio without much of a plan, but I wanted to play more as some kind of personal comfort. Just to play that music again, and to really feel the beauty of an acoustic grand piano. I was unsure as to whether it would be released or not, but I thought let me do some playing.���

Just sitting down and playing is something that Shepherd has not done much of over the five years since he last released a jazz album. While he had continued to tour and play shows occasionally in the interim, much of Shepherd���s time was taken up with a side gig that quickly developed into a second career: scoring for film and television.

Having taught himself the art from scratch, Shepherd contributed an award-winning score to the film Noem My Skollie in 2016. He followed that up with work on the feature film, Fiela Se Kind, which also won Best Original Score at the Silwerskerm Film Festival. More scoring work followed, including the film Barakat, directed by Amy Jephta, action thriller Indemnity, and the second season of the popular Netflix series Blood and Water.

In other words, he���s been busy���too busy to devote much time to his first passion: jazz piano. ���Working 10 to 12 hours a day on a film or Netflix series or whatever, as I���m doing now and have been doing for almost five years at least, I just had no time, unfortunately, to play the instrument in that context,��� Shepherd says.

���Contrary to my work in the film world, where you spend three months on something, I wanted to not spend that kind of time on trying to perfect a production. I wanted to get back to the rawness of improvising in the moment, of taking the leap off the cliff so to speak, and I wanted to just play. I played in a long form, an hour and a bit without stopping. A few months later, I listened to the recording and I thought ok, this is something we can work with. And that was it, to be honest.���

What flowed during that hour-and-a-bit is a remarkable aural odyssey articulating the journey of the human spirit and all that that entails: pain, grief, loss, memory, hope, joy, connection, love. Improvisation and recital here become a cipher that shines prismatic, somehow combining these contradictory emotions and impulses into something that is all these things, and yet is indivisible, showcasing a delicate, gestalt beauty. This album blooms brightly from the shadows of pandemic and tragedy and considers what it means to be South African, African, human, here and now.

This is a solo work, and it does indeed provide a singular and utterly original vision, but one that knows where it���s from, that is grounded in material reality, is begat by South Africa���s history, and finds in that history not a stifling weight, but a deep well. The warp and weft of a musical heredity is weaved into something that is honest and profound, and alive in the moment. The wellspring of spontaneous inspiration cannot but be sincere. It is the inside, unfiltered.

As Percy Mabhandu notes in his liner notes, this is ���alert, alive pianism. Shepherd crafts a base of superbly controlled chordal underpinnings to every bit of sweet lilting lyricism in laments and levities, or a faintly echoed call of the adhan; the staccato of the incantatory Xhosa, or the faded /Xam-ka tongues and modern Cape Malay street scamto.���

The themes of this album are universal, yet it is unmistakably South African. It marks yet another chapter in the role that jazz has played in the national narrative. ���I read a quote from Herbie Hancock just the other day,��� Shepherd explains, ���and he said that jazz is a great example of democracy in action. When musicians come together to play jazz, everybody has an equal opportunity on the bandstand to express him or herself. When one musician takes a solo, the rest of the band is performing, but they���re also expressing themselves as they support him, then he concludes his solo, and it switches to the pianist or the saxophone player, and the same process happens. And that���s a wonderful example of, as we call it in South Africa, this idea of Ubuntu, right there on the bandstand.���

���I���ve always enjoyed situations where musicians can come together and completely be on equal ground in terms of your self expression. And I love that about the music and I think that it sets this music called jazz apart in that way and it makes it very advanced, because it’s very difficult to play in that way. It requires each musician to firstly be absolutely committed to what they are doing and secondly also completely committed to listening to what everyone else is doing all the time. So the relevance to, especially our society, and showing that as an example is very important, because that���s the cornerstone of who we are, or at least what we���re trying to be, post ���94.���

The album opens with a poignant, improvised tribute to Keith Jarrett, the legendary jazz pianist and composer who suffered a series of strokes in 2018 that robbed him of the ability to play his instrument: reading the news about Jarrett ���actually kind of broke my heart,��� Shepherd says. The album also includes the song Sweet Zim Suite, composed in honor of saxophonist Zim Ngqawana, who was a mentor and friend to Shepherd before his death in 2011.

Indeed, grief looms large here, but hope larger, particularly through the second half of a longform recital that is almost cinematic in scope, as if there has been some osmosis between the two halves of Shepherd���s artistic impulses: freeform jazz and structured film score. The whole thing culminates in a remarkable rendition of the song ���Zikr��� (alluding to one of the central devotional acts of Sufism) that achieves a miraculous feat of transubstantiation, turning a piano into a kora and sculpting sound in a way that is truly surprising.

To belabor the fact that the album contains no new compositions would be to miss the point, for it is precisely the way in which known and loved songs are reshaped and stitched together that gives this album emotive power. The curious thing is that, while the final form displays a coherent narrative arc, its inception was entirely spontaneous.

���I���m very open in saying that I had not planned this album at all,��� says Shepherd. ���All of these things were happening in the moment. I felt there was an opportunity to find something new in that music. In fact, I feel that it���s the mandate of the music, and it puts it on the musician to explore these compositions in a new way every time you play them. I was just kind of submitting to how it was happening.���

This is Shepherd���s seventh album, and his first to be pressed on vinyl by South African label Mastuli Music, something that is ���very important��� to him. Indeed, the vinyl form is apt here. This album, on vinyl, is a beautiful object containing within itself beautiful sounds.

���I think there���s something to be said for the package of a vinyl also being a work of art, from the cover to the writing to the act of putting the vinyl onto a record player,��� says Shepherd. ���There���s just something about pulling out a vinyl and sitting down with it, looking at it, holding it in your hands. That’s a process that we don���t quite find the time for anymore, just to sit down and listen to some music.���

Jazz is not music that is meant to be overly intellectualized. It is meant to be felt. After The Night, The Day Will Surely Come should be listened to as one listens to the deep roll and crash of the Atlantic or the South Easter whistling through the trees, as one hears the muezzin, the defiant songs of city birds rising over traffic, the laughter of children. So, stop what you���re doing, and allow the spontaneous moment in. Log off. Shut that browser. Close your eyes. Listen. Feel.

Kyle Shepherd���s After The Night, The Day Will Surely Come is available from Matsuli Music here.

October 12, 2021

What happened to land grabs in Africa?

Oil palm plantation in Sierra Leone. Photo credit: Maja Hitij

Oil palm plantation in Sierra Leone. Photo credit: Maja Hitij Violence against land rights defenders in Uganda and anti-mine protesters in South Africa. Oil palm plantations razing forests in Liberia and the island of S��o Tom��. Industrial waste from sugarcane plantations polluting the environment and damaging livelihoods in Nigeria.

These are just some of the headlines from this past month. Reports such as these have not abated since the food and fuel price hike of 2007 and 2008 sparked new enclosures of land and resources across the world. Africa has been, and still is, the most heavily targeted continent for large-scale land acquisitions in terms of the total number and size of land deals reported. The past two decades��� global rush for African land has been driven by concerns about resource scarcity and misguided assumptions that Africa abounds in ���empty��� or ���idle��� land that suffers from what the World Bank has called ���high yield gaps.���

But herein lies the paradox: whereas land-seeking investors show continued interest in Africa, the continent is also home to the largest proportion of what some observers have called ���failed��� land deals (in the narrowest sense that negotiations and contracts have been canceled). According to Land Matrix, a public database on global land deals, half of all ���failed��� transnational agricultural land deals between 2000 and 2020 occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. Another study highlights that investors involved in agriculture, energy, forestry, and other sectors in Africa have frequently been mired in disputes with local communities that lead to significant project delays.

In our new, guest-edited African Studies Review forum on ���Understanding Land Deals in Limbo in Africa,��� we take up these issues further by examining the contentious politics of incomplete land grabs in Senegal, Tanzania, and Zambia. Drawing on long-term ethnographic research, the four studies in the forum show that even when land deals are canceled, stalled, downsized, transferred to new owners, or stay dormant and speculative for many years, they can still produce far-reaching consequences that often go unnoticed.

What explains these contingent results? How do different parties involved���host states, foreign and domestic investors, and local communities���negotiate the uncertainties and anticipations surrounding not-yet-realized projects? Who are the ultimate winners and losers? These questions must be at the forefront of policy debates on land, development, and agrarian transformation in Africa. Here, we highlight three key themes from the forum that have important lessons and broader relevance for understanding similar dynamics across the continent.

The first lesson has to do with the challenges of land control and governance. A common pattern we find across the case studies is that even when states have formally transferred land to investors, investors have a hard time taking possession of it on the ground. Take the case of Zambia: as our colleagues show, investors there have struggled to navigate a plural land tenure system in which they had to assemble hundreds of different title deeds to physically create a large-scale block farm���an effort which proved to be in vain. As all the cases in the forum show, the tracts of land which governments allocate to investors are often already occupied by customary resource users. Of course, some projects can and have used force to dispossess local populations, but this is often an unpopular choice for investors concerned with maintaining their image as ���responsible��� companies.

In most parts of Africa, where state institutions directly control the land acquisition process, investors are compelled to perform and sustain amiable relationships with host governments, even if that requires repeatedly realigning their project objectives to meet government priorities. Even then, investors still bear the risk of the state arbitrarily revoking their title deeds, as we have seen in numerous countries across the region. This is often a consequence of nation-states needing to juggle the competing demands of capital accumulation via resource extraction on the one hand, and preserving their political legitimacy and social stability among majority rural voters on the other.

The second lesson is that the uncertainties surrounding stalled land deals lay bare the complexity of local politics and, at times, reinforce social inequalities. The forum highlights how prolonged negotiations can create opportunities for diverse groups of people, including local residents, landless migrants, and local elites to occupy and/or sell plots within investment areas, thereby foiling corporate attempts at land control. Local resistance efforts, such as protests and lawsuits, can temporarily halt land deals or force states to revisit contracts, as the studies from Tanzania and Senegal show. But they can also deepen local fault lines by excluding women, certain ethnic or religious groups, and the people who are most likely to be displaced. Investors, for their part, may try to co-opt consent from a small group of powerful actors to avoid further delays and deflect popular dissent.

The final lesson speaks to the limits of capital. Despite promises of millions of dollars of capital outlays and socioeconomic benefits, investors seldom come with cash in hand, particularly for large-scale ���greenfield��� projects. Numerous cases, including the ones featured in our forum, demonstrate the difficulties investors face with raising start-up funds, withstanding fluctuations in the global commodity market, managing financial risks and shareholder expectations, and, in the case of agriculture, adapting to ecological production constraints that capital and technology cannot fully resolve. Many investors also do not have the necessary experience with tropical agriculture. Large-scale land acquisitions in Africa���once thought of as a ���safe��� way for investors in the global North to hedge against inflation and food and energy shortfalls���have yielded little success in providing easy fixes to capitalist crises.

In brief, the complex interplay of land governance, local political dynamics, and capital���s own contradictions can push land deals in different and unexpected directions. These inconclusive land deals, however, can still severely limit people���s land access and livelihoods, perpetuate fear of dispossession, and intensify local conflicts. And in some cases, they can lead to international arbitration processes between states and foreign investors���processes which seldom serve the interests of rural communities.

As the world continues to grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic, companies are devising new tactics to evict farmers while governments fast-track legislative reforms to facilitate land acquisitions. To make agricultural development truly sustainable and equitable, policymakers must take heed of the invisible costs that both ongoing and unfinished land grabs impose on diverse rural communities.

The cry of Black worldlessness

Photo by LT Ngema on Unsplash

Photo by LT Ngema on Unsplash ���Ilizwe lifile!��� The world is dead!

���Ilizwe lifile!��� Our ancestors cried as the 1779-1879 Wars of Dispossession expanded the reach of 1652���s settler colonial conquest deep into the South African interior. Our ancestors cried that it was not only Black people who suffered a social death, but the land, indeed, the world, suffered death too. Our ancestors��� cries of the end of the world sounded a cosmological rupture that reverberates across generations, and could be heard throughout the land as their dispossessed descendants wielded the unrest and protest that decisively called the end of the ���post���-apartheid rainbow���the end of a world in which they have no stake in, the end of a world built by their continued dispossession.

The cry was heard two months ago, as South Africa convulsed under the worst public violence since�� apartheid���s official end. ���Ayikhale!��� came the rallying cry from former president Jacob Zuma���s supporters, as they protested his July 7 prison sentencing for contempt of the constitutional court in the midst of an ongoing state corruption commission. Across Zuma���s home province of KwaZulu-Natal and the economic hub of�� Gauteng, many answered the call to render the nation ���ungovernable������targeting supermarkets, furnishers, and clothing and electronic stores. In the carnivalesque chaos, the smash and grab, they were soon joined and outnumbered by ordinary citizens answering to a different rallying cry. Citizens grabbing bread and maize meal and diapers jostled alongside those grabbing cake and couches and flat screens, plunging the nation into a cacophony, which the chattering middle classes and their pundits struggled to decipher. As the ���Rainbow Nation��� went up in flames, the old cry of the ���swartgevaar��� mobilized property-defending racial laagers which, to the shock of their Black middle class neighbors, turned away and targeted Black citizens regardless of class. With the Phoenix Massacre, the vigilante violence reached its apotheosis with 36 Black people murdered in Durban���s historically Indian township.

If ���Ayikhale��� was the mobilizing cry that a small but effective group of politically motivated actors answered to, there was another cry���deeper, more resonant���-that mobilized the marginalized majority as they staged what can be understood as post-apartheid South Africa���s most decisive insurrection.

���Ayikhale!��� rang out in a nation already crying out in crisis. The economy was in recession before the country recorded its first COVID infection in March 2020. In one of the world���s most spectacularly unequal societies, the state imposed several years of austerity. Once the pandemic hit, a $30 billion COVID stimulus package���equivalent to 10% of the country���s GDP���had been stolen by government officials. By the first quarter of 2021, unemployment���concentrated among Black people���rose to a record high of 43,2%, the highest in the world. Likewise, the 74.7% unemployment rate, among the generation of�� Mandela���s ���bornfrees��� raised in the post-apartheid era, is also the world’s highest.

Overwhelmingly, the face of post-apartheid poverty and hopelessness is Black and female. Under what former president Thabo Mbeki infamously christened as South Africa���s ���two economies��� in his trickle-down empowerment evangelism, poor Black life is rendered surplus and superfluous.��Week in, week out, scenes of burning tyres and stone- barricaded township roads, are, at best, euphemized as ���service delivery protests��� and, at worst, criminalized. Without consequence, the post-apartheid state murders poor Black people during protests or eviction.

It is unsurprising then that the demand���the cry���to be recognized as human is central to the language of Black popular protest. In their statement to the South African Human Rights Commission���s 2015 Hearings, ��Abahlali baseMjondolo, the Durban shack dwellers��� movement whose members have faced arrest, assault and assassination in their struggle for post-apartheid liberation, cried out that poor Black people ���are not counted as human beings.��� To the question posed by bureaucrats and chattering classes perplexed by their nation���s status as ���the world���s protest capital,��� their answer is simple: ���The demand for land and dignity is the underlying reason for protest. If people were respected and recognized as human beings there would be no need for protest.���

Indeed, amidst the confusion and chaos, the baton and bullet wielded on Black skin in search of bread and being in the world���s most unequal society, theirs is a cry of historic and cosmological proportions.

���Ilizwe lifile!��� Our ancestors cried as the 19th century���s minerals revolution burnished Southern Africa Black with dispossession. In that Gilded Age, where gold had just become the foundation of the global economic system, Southern Africa���s Minerals Revolution began when diamonds were discovered in Kimberley in 1866 and accelerated when 40% of the world���s gold stores were discovered on the Witwatersrand in 1886. From the intense pressure of this Black furnace, one of the world���s most dramatic social and industrial transformations produced the dynastic wealth that made ���Randlords��� of white men like Cecil John Rhodes and the dispossession that made chibaro���slave labor���of the peoples of the last independent African polities. Rhodes��� feverish imperial dream was Africa���s furious inferno.��

Stimela! Hugh Masekela cried of the coal trains, the iron bulls of settler colonial modernity, charging through the hinterlands of Southern and Central Africa, conscripting African men, young and old, as chibaro in the compound mining system pioneered by one Welsh engineer named Thomas Kitto ���borrowing��� from Brazilian slave-mining compounds. Under the gun���s ring and the sjambok���s crack, enslaved Southern Africans mined the world���s richest mineral stores, producing Black death at a rate as high as one in ten miners.

Today, Black Death continues to produce the Rainbow���s riches. Eighteen years into the arc of the Rainbow Nation,��post-apartheid South Africa���s��third Black president consigned 34 Black mine workers to death for the crime of striking for a living wage of R12,500 (USD1500). Marikana 2012. The worst state massacre since Bulhoek 1921, Sharpeville 1960 and Soweto 1976. Once again, we hear Winston Mankuku Ngozi���s horn: Yakhal���inkomo. The cry of the bull on the way to slaughter. This time when we hear their cry, it is not Verwoerd or Vorster, it is our third Black President, Cyril Ramaphosa, who calls for Black slaughter. Sitting on the board of Lonmin, the transatlantic monstrosity founded as the London Rhodesia Company in 1909, at the very heart of that bloody minerals revolution, our Black president instructed the police to take ���concomitant action��� against people who dared contest a rainbow world where it would take a Black miner 93 years to earn what the average mining baas receives as annual bonus.

Are we going forwards or are we going backwards?

���Ilizwe lifile!��� Our ancestors cried on the eve of the 1913 Native Land Act‘s cataclysm.

���Awakening on Friday morning, June 20, 1913, the South African native found himself, not actually, a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth.����� So begins the famous opening line to Sol T.��Plaatje���s classic Native Life in South Africa���a singular witness to Black life, death and dispossession as landlessness became the cornerstone of what South Africa���s Marxists later named ���racial capitalism.��� By forcing the Black majority onto seven percent of the country���s arable land, the settler state reserved the lion share for white settlers, who conscripted Black people into the cheap labor needed to fuel its voracious mining and agricultural furnaces.

Inspired in part by W.E.B. Du Bois��� The Souls of Black Folks, Plaatje���s Native Life bore witness to Black people���s spiritual strivings under dispossession of dazzling contradiction and paradox that still circumscribes our lives today and testified: It is one thing to live the double consciousness of a minority, it is quite another to live the double consciousness of a minoritized majority. To be a pariah in the land of your birth is to live the spiritually and psychically disorienting paradox of exile at home. With no home, we are condemned to a wandering spectral existence, haunting the world. Then, as now, Black people are pariahs of the world. Half a century after Plaatje, Barbadian poet Kamau Braithwaite asked questions of this exilic nature of Blackness,

Where then is the nigger���s

home?���

Here

Or in Heaven? ���

Will exile

never

End?

Hear this.

More devastating than the landlessness and homelessness that spools out from Native Life‘s famous opening line, Plaatje confronted more cosmologically devastating questions after encountering the wandering Kgobadi couple, stricken by the loss of their infant who had just succumbed to the privations of their landless life: ���The deceased child had to be buried, but where, when, and how?���

Amidst the grief of eviction, the young wandering Black family, condemned to a spectral and fugitive existence on the public roads������the only places in the country open to the outcasts if they are possessed of a travelling permit������could not even right the cosmic aberration of a child���s death. With no land, they could not bury and return the child to the ancestors. They had no place on earth. Where, when and how to live? Where, when and how to die? These are questions of spatial-temporal alienation that haunt Black beings in the world. More than questions of landlessness, more than questions of homelessness, these are questions of worldlessness: To have no place to live nor to be buried. To have no place to be alive nor to be dead. To have no place to be in the world���what the pre-eminent Black psychologist Manganyi Chabani called ���Being-Black-in-the-World,��� is the state of worldlessness.

���Ilizwe lifile!��� Settler colonial conquest dispossessed us of our fathers, who were conscripted as the ���mineboys��� and ���farmboys,��� who picked and ploughed the spectacular wealth that would never reach their own tables. It dispossessed us of our mothers, who were conscripted as the ���housegirls,��� who raised white children who grew to despise us and them. It is this violent migrant labor system, Southern Africa���s systematic spatial dispossession and destruction of the Black family that creates the ���wounded kinship��� that saturates Black life and death. It is this racial violence that compelled South Africa���s Marxists to be the first in the world to confess and name the existence of the term that has come to define this global Black Lives Matter moment������racial capitalism.��� While the Marxists could quantify our material crisis, they could not begin to account for our deep psychic, spiritual, and existential crisis. What African-American poet Nathaniel Mackey calls ���wounded kinship��� is the bedrock of racial capitalism. If the worker���s crisis begins with their alienation from work, the Black���s crisis begins with our alienation from the world.

Today, if we listen carefully, we can still hear the cry of Black worldlessness and wounded kinship. Today, Black people continue to cry out that we have no land to live, nor land to bury, no land to be at a time when white South Africans, nine percent of the population, hold 72% of the land, while we, Black people, 79% of the population, hold one percent. In 2014 Oxfam warned us, two white men��� Johann Rupert and, Nicky Oppenheimer, the inheritor of Rhodes��� murderous empire���own as much wealth as the bottom half of the land.

Poet Mongane Wally Serote���s 40-year lament, still haunts us: ���it is only in our memory that this is our land.��� The land haunts our memory, and, in turn, we haunt the land���s memory.

Today, fifteen seasons in, ���Khumbul���ekhaya���(���Remember home���), a reality show attempting to gauze and stitch our wounded kinship, to re-member Black homes dismembered by dispossession, is a compulsory Wednesday night fixture in Black homes across South Africa. That this televisual is just as, if not more popular than the most entertaining of our soapies, is our national confession of wounded kinship, our deep longing to khumbul���ekhaya, to re-member home, haunts our emotional universe.

���Indeed, memory or ���rememory,������ South African novelist Yvette Christianse��, invoking Toni Morrison, reminds us, ���is the gift that the living give, constantly, daily to the dead. Memory is the gift of a survivor and, as a gift, it is the medium of obligation … [to] those who have gone before and those who come after.���

Then, in the wake of the 1913 Land Act, South Africa���s most revered Black composer Reuben Tholakele Caluza sounded our Black cry of wounded kinship and worldlessness in ���Si lu Sapo or iLand Act,��� which for a time was the African National Congress��� anthem before ���Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika����� (���God Bless Africa���) replaced it:

S���kalel��� ingane zaobaba

Ezimihamb��� im��� ezweni zingena ndawo yokuhlala

Elizweni lokoko betu

(We cry for the children of our fathers

Who roam around the world without a home

Even in the land of our ancestors)

Already, Caluza���s anguished cry of worldlessness had sounded the South African Blues that jazz legend Jonas Gwangwa described in 1990,�����If you listen carefully to all South African music, that cry is there. I don���t care whether you raise the tempo ��� You could raise the tempo but when it starts playing, that lament is there. Lament ��� I hear it. I hear it.���

Can we hear it?

It is there in the rushed breath of Black Commuters stranded by in-fighting taxis, now making the rushed trek from Khayelitsha township to Cape Town���s Central Business District by foot, lest they lose their jobs.

It is there in the idle laughter of majita, magenge, majimbozi convening ekoneni���the young Black men often criminalized and consigned to the 75% of youth marked by our economy as unemployed or unemployable.

It is there in the shivers of abomama���s shoulders as they queue in the cold for the USD23 COVID relief grant that stands between their families and hunger.

It is there in the carnivalesque grab of cakes, cool drinks and couches, which we have no need for as we run for chase.

It is the cry of want in the midst of waste.

It is the cry of wounded kinship.

It is the cry of worldlessness.

Are we listening?

October 11, 2021

The end of Tunisian democracy?

Oued Ellil, west of Tunis, capital of Tunisia. Image credit Xinhua for Pan Chaoyue via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Oued Ellil, west of Tunis, capital of Tunisia. Image credit Xinhua for Pan Chaoyue via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. In a widely supported move in July, Tunisia���s president Kais Saied suspended parliament, sacked the prime minister, and assumed emergency powers. In September, he suspended parts of the constitution, announced rule by decree, and appointed Najla Bouden as the country���s first female prime minister. Many Western commentators are now wondering, is this the end of Tunisian democracy?

This week on AIAC Talk, we chat to Maha ben Gadha, the economic program manager at the Tunis-based, North Africa office of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. We dig into the roots of the political crisis, uncovering how Tunisia���s political class has lost legitimacy since the 2011 revolution by failing to deliver social transformation. Beyond the right to vote, Tunisians want a democracy that includes jobs and dignity too. With fiscal pressures growing and an IMF loan on the cards, will the president be able to respond to popular demands?

Listen to the show below, and subscribe via your favorite platform.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/ffcf3383-4f98-4cb5-b243-13e26dc142bc/aiac-talk-s3-ep-3-audio.mp3October 10, 2021

Not mere intellectual dissenters