Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 112

November 28, 2021

Simply filming people���s lived experiences

Still from I am Samuel.

Still from I am Samuel. The Kenya Film Classification Board (KFCB) recently restricted the screening of the film I am Samuel, centered on a gay Kenyan couple, because it did not “promote Kenya’s moral values and national aspirations.” This is the third LGBTQI+ Kenyan film that has been banned by the KFCB, and the producer of the film, Toni Kamau, questions how long this silencing will continue. This series, republications from The Elephant, a content partner with Africa Is a Country, is curated by one of our editorial board members, Wangui Kimari.

I may not agree with what you say, but I���ll defend to the death your right to say it.

We first got introduced to independent documentary filmmaking in 2013, at a gathering of Kenyan filmmakers in a small office of the nascent DocuBox film fund. Pete Murimi, director of I am Samuel, and I, producer, had no idea that it was possible to tell stories independent of a broadcaster or funder. As a service producer, I was used to receiving agency or broadcaster briefs and working according to spec. Pete, as a filmmaker at the UN, was familiar with that style of telling stories.

This intimate gathering of filmmakers (which included directors of The Letter, Kenya���s submission to the Oscars in 2020, and the director of New Moon, winner of Oscar-qualifying 2018 DIFF Best Documentary award) did not know that it was about to embark on an arduous multiple-year journey to tell their stories, and self-release at global festivals. But we all somehow made it through the strength of community and the determination to have complete agency over the stories we felt were important to tell. Pete and I were committed to telling stories of outsiders, people who did not accept the way things were, just because.

Voltaire���s quote above is our fallback when asked about freedom of expression, the freedom we committed to when we decided we wanted to tell these stories. We are a diverse country, with complicated, layered realities. Allowing storytellers to tell these stories, no matter whether you agree with them or not, is a move towards greater inclusivity, democracy, and tolerance.

Shot over five years, I Am Samuel tells the story of a queer man navigating the tension between his life in Nairobi and his rural childhood home. He and his partner Alex want to build a life together, but his father and mother want him to get married, have kids, and live the exact kind of life they have.

This was not an easy documentary to make. Samuel had to give up a lot of his privacy, and trust Pete and I, who were first-time independent filmmakers, balancing making this film with our day jobs. But Samuel allowed us into his life, without restriction. And that was a privilege that we could not afford to take lightly. Alfred Hitchcock once said, ���In fiction films, the director is God; in documentary, God is the director.��� We believe this to be true; life as it happens, with all its messiness and unpredictability, is what makes character-driven verit�� styles so difficult to do, but ultimately so rewarding.

I am Samuel was released at Hot Docs 2020, an international film festival that showcases stories from across the globe. It then toured the Human Rights Watch Film Festivals the world over and showed in South America, the Netherlands, and the UK. But our eventual goal was always to bring it back home. Because we felt this was a Kenyan story, we knew it would connect with audiences back home; mostly because Samuel���s lived reality as a queer, religious, traditional man is not unique. We applied for classification in Kenya to be able to screen it locally, and waited weeks for a response. We were asked to attend a meeting at the KFCB offices on Thursday 23rd September, but we were unable to make it in person. We then heard about the press conference, the ban, and the press release later that Thursday.

We are yet to receive a letter in writing or a certificate that shows our Kenyan rating.

We were deeply disturbed by the discriminatory language used in explaining the ban: they described it as ���blasphemous��� and ���unacceptable, and an affront to our culture and identity.��� The restricted classification of the film contained a number of inaccuracies. It referenced a ���marriage��� that never happened and said we were ���promoting a homosexual lifestyle.��� The board noted a ���clear and deliberate attempt by the producer to promote same-sex marriage as an acceptable way of life. This attempt is evident through the repeated confessions of the gay couple that what they feel for each other is normal and should be embraced as a way of life, as well as the characters��� body language, including scenes of kissing of two male lovers.���

We were simply filming people���s lived experiences.

By banning the film, KFCB is silencing a real Kenyan community and trampling on our rights as filmmakers to tell Samuel���s story. Every story is important. And we are all equal in the eyes of the law and before God, in line with the religion the film board is invoking in this ruling. The arts���from filmmakers and novelists to painters and comedians���hold a mirror up to society and show us some of the difficult realities from which we often try to shy away.

The Kenya Film Classification Board is trying to censor a part of Kenya that has always existed, is a lived reality for millions and will always be a part of us. Several high-profile Kenyans are queer, including government politicians and public figures, but the intolerant atmosphere created by discriminatory statements like those of the KFCB make it impossible for them to live openly���and allow other Kenyans to continue to discriminate, wrongfully so, against LGBTQ+ Kenyans. As I Am Samuel shows, prejudice forces LGBTQ+ Kenyans to live in the shadows, fearful of being beaten up, fired from their jobs, or evicted from their homes. Stigma puts pressure on their families, who fear that if their neighbors find out they have a gay child, they will be ostracized.

In their press statement, the KFCB appealed for content that ���promotes Kenya���s moral values and national aspirations.��� What are these values? The KFCB is assuming that the values of all Kenyans are the same���conservative and Christian. But Kenya is a diverse country and it is the responsibility of our government to represent and serve everybody. Our differences should be acknowledged as a strength, and shown through our filmmaking. Kenya is Africa���s third biggest film producer, after Nigeria and Ghana, making 500 films a year. African filmmakers are attracting international acclaim. Softie won an award at the prestigious Sundance Film Festival last year. The United Nations recently said that the African film and audio-visual industry generates US$5 billion a year and has the potential to create 20 million jobs. I Am Samuel is the third LGBTQ+ film to be banned by the KFCB, following Stories of Our Lives (2014) and Rafiki (2018). Among other movies that have been banned by KFCB are The Wolf of Wall Street (2014) and Fifty Shades of Grey (2015).

Our film is a true record of Samuel���s lived experience Samuel. Gay African men, gay African people, should be recognized and have their rights respected. This includes the right to freedom of expression, freedom of association and freedom from discrimination. Samuel himself is a strong Christian, and Kenya has several LGBTQ+-friendly churches that provide a place for queer Kenyans to worship together. Banning of films is a blow to Kenyan filmmakers as our audience is inherently local, and we need to have a wide distribution to reach audiences, to go regional, to go global, for so many reasons: telling our own narratives, correcting the misguided ones, creating jobs, and widening our own imaginations, exponentially, of what is possible for us as Kenyans. The Lupita Nyong���os and Edi Gathegis of this world should not only exist in a rare and unexplored vacuum.

It is time for the government to accept and support our creative industries, and allow every Kenyan���s voice to be heard���because the banning also leaves us with questions about whether everyone���s point of view truly is listened to. The documentary has been released across Africa on the AfriDocs website, and we hope that African audiences will still get a chance to watch a film that is not accepted in its home country ��� yet.

November 24, 2021

Reading Africa, Africans reading

Abdulrazak Gurnah at the Palestine Festival of Literature. Image via PalFest on Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Abdulrazak Gurnah at the Palestine Festival of Literature. Image via PalFest on Flickr CC BY 2.0. This year is being roundly pronounced as ���a great year for African writing.��� From Zanzibar-born Abdulrazak Gurnah���s Nobel award to South African Damon Galgut nabbing the Booker���the list of African and diaspora writers winning prestigious literary prizes this year is long. Does this represent a paradigm shift in global literature, typically dominated by Western authors? Do these victories do anything to advance African publishing and literary culture? Joining us in this week���s AIAC Talk to unpack these themes, are Ainehi Edoro, Bhakti Shringarpure and Leila Aboulela.

Ainehi Edoro is a Nigerian writer an assistant professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison as well as the founder and editor of Brittle Paper, Bhakti Shringarpure is an associate professor of English at the University of Connecticut, editor-in-chief of Warscapes magazine and is also a founder of the Radical Books Collective; and�� Leila Aboulela is the prize-winning author of Bird Summons, The Translator, The Kindness of Enemies, Lyrics Alley and Elsewhere Home.

Listen to the show below, and subscribe via your favorite platform.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/ae450886-11d4-4431-8304-dbea3897fb44/aiac-talk-african-literature-and-lit-prizes.mp3November 22, 2021

Gangsters as people���s champions

Cape Town. Image credit Brent Newhall via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Cape Town. Image credit Brent Newhall via Flickr CC BY 2.0. In early January 2021, Durban, South Africa���s second-largest city, was rocked by the fatal shooting of alleged gangster and drug kingpin Yaganathan Pillay, also known as Teddy Mafia. According to reports, Teddy Mafia was revered by some in his community of Shallcross as the local Robin Hood. Shortly after he was killed, community members, some of whom were likely Teddy Mafia���s soldiers, took the law into their own hands by apprehending the two alleged shooters, beheading them, and setting their bodies alight in broad daylight.

A few days later, Teddy Mafia was laid to rest. The scene that played out at his funeral echoed the community���s reverence for him, with people praising his name and chanting, ���Viva Mafia, Viva��� and ���Viva, people���s champion.”

What transpired in Shallcross is something that can be found across all of South Africa���s volatile, gang-ridden areas. There are many Teddy Mafia-type gang leaders who possess a great deal of power and influence in the communities they reside in.

Gangsterism has existed in South Africa since the early 1950s. During the 1950s, disadvantaged coloured, Indian, and black working-class communities utilized group vigilantism as a mechanism for protection from apartheid authorities and criminal groups in their areas. As the vigilante groups grew, criminal elements began to filter through their ranks and their focus turned to organized crime. Gradually, people leaving prisons infiltrated the groups, and vigilante groups became indistinguishable from the criminal gangs they initially aimed to eradicate.

South Africa has a complicated history of gangs being used by the apartheid government in the fight against anti-apartheid activists. Meanwhile, other gangs cooperated with anti-apartheid activists and members of Umkhonto weSizwe, the African National Congress���s armed wing, before 1994. In fact, gang leaders such as Rashied Staggie, the leader of the influential Hard Livings gang who was killed in December 2019, argued in 1997 that the ANC owed a debt to these gangs for the support they provided to the movement during the anti-apartheid struggle.

The drastic rise in criminal activity since 1994 has been exacerbated by the lack of meaningful transformation and growing inequalities. Factors that continue to contribute to the growth and expansion of gangs in disadvantaged communities include the lack of access to opportunities and work; marginalization and segregation of coloured and black communities; lack of service delivery, poverty, and deprivation; and the failures of the justice system and policing.

Areas across South Africa���such as the townships on Cape Flats in Cape Town, Northern Areas in Port Elizabeth/Gqeberha, and Chatsworth in Durban, to name a few���have become well-known for their growing gang cultures and criminal gang activities. High levels of violence and crime in townships such as Soweto in Johannesburg and Gugulethu in Cape Town have also been linked to gangsterism and organized crime.

How and why are the gangs and gang leaders so powerful, admired, and/or feared in their communities? How is it possible that so many in Shallcross felt so enamored and indebted to Teddy Mafia that they found it necessary to defend his name and chant praises at his funeral? Are gangsters really the people���s champions?

Gangsters have been able to utilize the failures of the South African government to their own benefit. Socioeconomic challenges, poverty, and inequality have helped the gangs integrate themselves into the social structures of their communities and establish themselves as critical structures in the provision of financial means, food, job opportunities, and other necessities to struggling community members. By assisting their surrounding communities, gangs have been able to win or buy the support and loyalty of their fellow community members.

This is evident in the reaction to Teddy Mafia���s death in Shallcross and the ���Viva people���s champion��� chants at his funeral. Those who murdered his alleged assassins may have been his loyal soldiers, fearful community members, or the beneficiaries of his support. Whoever they are, they have been failed by the society and the country���s transition from apartheid to democracy���and likely had no choice but to either join his gang or accept his support.

For some, Teddy Mafia probably was a champion. He may have provided jobs to unemployed community members, paid school fees for those who couldn���t afford to pay for their children���s schooling or their school uniforms, or bought food for those who were starving. If he did this, it was because he needed the community���s silence or support in order to ensure that his ���business��� activities could go on uninterrupted.

South Africa is not unique in this regard. Pablo Escobar, for example, did the same in Colombia, spending some of the profits of drug sales on building clinics, hospitals, and homes for the poor, as well as on funding food banks. He did this not only to improve his public image and to get local communities on his side, but also to step into the breach where the Colombian state was absent.

For people who live in the disadvantaged areas of South Africa where gangs operate, there are limited options for survival. For many, moving out of these areas is not an option, since moving requires resources that the poor and vulnerable do not have. Some resist the gangs and suffer the consequences, while others sit quietly and hope to survive. There are also those who join the gangs out of sheer desperation, seeing no other options. The same scenario applies to prison gangs, which utilize fear and desperation to force vulnerable incarcerated youth to join gangs in prison.

Gang leaders are aware of the problems and fractures in South African society, and they exploit each and every socioeconomic, political, and other challenge facing vulnerable communities. They do this to recruit members or to buy community support or silence. They also bribe the police, prison wardens, politicians, and government officials.

It should not come as a surprise that these gangsters and criminals, who provide assistance to their communities, are seen as the people���s champions in a country like South Africa. This is a country where the people don���t trust government officials, the police, or their local councils.

This is a country where billions of Rand are stolen or spent irregularly every year by politicians and their friends, and where hardly anyone ever pays the price for corruption and stealing. It is the country where, during the pandemic, government officials stole billions meant for the fight against COVID-19 and for the poor.

If politicians���many of whom keep failing the country and the people while running mafia-style patronage networks and looting taxpayer funds without consequence���can claim to be the people���s champions, who is to say that the gangsters who sometimes provide support to members of their community are not also the people���s champions?

Around the world, gangs have been involved in the local and national politics of many countries. In Jamaica, for example, the past few decades have seen gang leaders use their funds, power, and influence to help politicians win elections. In return, politicians allowed them to operate their ���empires��� with impunity. Elsewhere, gangsters have had political aspirations���Escobar, for example, got elected to the Colombian congress in 1982, although he was forced to stand down after Colombia���s justice minister publicly called him a drug trafficker. Despite this, Escobar was able to run his drug enterprise for many years with the help of threats, assassinations, and by bribing authorities and politicians.

While South African politics is not (yet!) on the same level as what Colombian and Jamaican politics were at one time, there are links between the involvement of gangs in politics and public life. In 1996, gangs in the Western Cape formed an organization called Community Outreach Forum (CORE). The organization claimed to be interested in peace, calling for political engagement with the authorities. CORE also demanded that the government protect its members from vigilante attacks by another organization, People Against Gangsterism and Drugs.

Research conducted by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime shows that in the Eastern Cape province���s Nelson Mandela Bay, gangs have been involved in politics and business since 1994. Gangs have benefited from ���tenderpreneurship������securing of government tenders and contracts for the provision of public services by their formal businesses���through their links with local politicians and councillors.

Elsewhere, Caryn Dolley has written about the involvement of gangsters in South African politics. The political party Patriotic Alliance (PA), for example, is led by former gangster Gayton McKenzie. Rashied Staggie, one of the most prominent South African gang leaders of the past three decades, was also a member of the PA before he was killed.

Every time gang violence escalates in South Africa, there are calls for the army to step in and assist the police in the fight against gangsterism. However, this is not a solution to the country���s gang violence and organized crime. The army is not trained for interventions in civilian communities, and a ���war on gangs��� has never brought stability and peace, anywhere in the world. More plausible interventions include improvements in policing and the justice system.

Other key interventions include addressing the socioeconomic challenges facing underprivileged communities across South Africa and improving the livelihoods of vulnerable people. The government must improve the delivery of basic services and the education system, create employment opportunities, and address apartheid spatial planning. In addition, the government should work closely with those who are already embedded and working in vulnerable communities across the country. This includes working with community initiatives and projects aimed at combating crime and violence in gang-ridden areas. Many of these organizations require support and resources but have struggled for many years to get government support.

Until socioeconomic conditions and realities improve for the millions of vulnerable South Africans, they will continue to be exploited by criminals and gangsters. There may possibly still be a small chance to turn the tide. This requires good governance, the eradication of corruption, better policing, a more effective justice system, and improved public education, job creation, and socioeconomic transformation. Basically, everything that has been promised since 1994 but has yet to be delivered.

November 19, 2021

Kenya is Europe’s dumpsite

E-waste recycling factory. Image credit Judit Klein via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

E-waste recycling factory. Image credit Judit Klein via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. While promising “urgent climate action,” European countries are still dumping electronic waste in Kenya under the veneer of exporting second hand appliances. This e-waste dumping contravenes both the Basel Convention and the European Union Waste Shipment Regulation, and, against insufficient will and regulation to curb this trade locally, does extensive harm to Kenyans lives and our collective environment. This series of articles republished from The Elephant (based in Nairobi, Kenya), is curated by one of our editorial board members, Wangui Kimari.

On a cold Friday afternoon in July, Wambui is standing in the doorway of her roadside shop scrolling on her tablet. The street outside is empty. A woman wrapped in a Maasai shawl sits in a white plastic chair inside the shop. In front of her are plastic toys, vacuum cleaners, and electronic cutting equipment. A CCTV camera is mounted in the ceiling.

The shop is on a busy street in Ngara, Nairobi, and as I approach, Wambui calls to me to have a look at her wares.

���UK fridges are of high quality,��� says the shopkeeper. A small refrigerator with no brand name is going for KSh20,000. ���But I���ll sell it to you for KSh18,000. It is the best I can do,��� she says.

Wambui has been in the business of selling imported second-hand appliances for about a decade. She says it is impossible to recall the number of cooling appliances she has sold, all imported from the UK through a middleman.

Inside the freezer compartment of one of the fridges are phone numbers in blue; 0870 is a premium help number for Domestic and General, a repair company in the United Kingdom, 0121 is a Birmingham number for spares. Birmingham is the United Kingdom���s second largest city.

Large importsDespite being a signatory to international treaties regulating and banning the dumping of damaged and end-of-life electronics, Kenya still imports large quantities of electronic and electrical goods that are considered too inefficient to be sold in the country of origin. The appliances enter the country legally and a tax is paid to customs for their clearance.

Nairobi, Mombasa and Eldoret have thriving second-hand markets for cooling appliances, numerous repair shops and dealers in scrap. I visited some 20 shops, the majority of which were selling appliances from the United Kingdom while others were trading in appliances from Germany, United States, India, and even Sweden in one case.

Nearly all the shops have an online presence, either on Facebook, on Instagram, Pigiame.co.ke, and Jiji.co.ke, while some use WhatsApp groups to post photos of appliances and their prices.

But this trade in obsolete and inefficient second-hand cooling appliances that are harmful to the climate is not regulated. In effect, Kenya lacks a proper e-waste law and does not have the capacity to manage hazardous substances from cooling appliances that have reached the end of their life. An Electronic Waste Bill was formulated in 2013 but was never passed into law.

���Heavy metals like mercury, zinc, cadmium are harmful when they come into contact with the human body or natural resources like water,��� says Boniface Mbithi, the Chief Executive Officer of WEEE Centre, an e-waste recycling company. ���When plants absorb water that is already contaminated with heavy metals, and people eat these plants, [this] causes cancer, kidney failure, or even leads to mental disorders.���

Tony, a fridge repairman, sells fridge compressors and freezers from Germany and the United Kingdom. He cannot afford direct shipments like Wambui but he has his way of getting around that obstacle; sourcing his goods from towns like Mandera and Garissa that border Ethiopia is his best alternative. He is unaware that old, inefficient refrigerators can leak harmful gases into the atmosphere during repair.

Tony, displays EX Germany and EX UK freezers outside his shop. He is unaware old, inefficient refrigerators can leak harmful gases into the atmosphere during repair. Photo Naipanoi Lepapa.

Tony, displays EX Germany and EX UK freezers outside his shop. He is unaware old, inefficient refrigerators can leak harmful gases into the atmosphere during repair. Photo Naipanoi Lepapa.���I have to check if they are working before they are released into the market. Some come broken. I repair them, refill the gas, and change the compressor,��� Tony said. But despite his best efforts, not all appliances are reparable. Those, Tony says, are sold as scrap in the informal recycling sector.

Unaware of the harm refrigerants can cause, scrap dealers release the gases into the atmosphere as they try to recover valuable components from the appliances, contributing to the depletion of the ozone layer and to climate change.

Improper disposalBrian Waswala Olewe, an environmental education specialist at Maasai Mara University, notes, ���Improper disposal of the refrigerant into the environment destroys air quality and affects health.��.��.��. Freon, an odourless gas, cuts off oxygen supply to organs and cells and leads to cardiac arrest and death when deeply inhaled.���

Yet, Kenya does not have accurate data on imports of cooling appliances, especially refrigerators and air conditioners. The Customs Department of the Kenya Revenue Authority claims that it does not have specific records of the second-hand cooling appliances entering the country because most imports of these electronics come in consignments together with other goods.

Although Kenya is a signatory to the Montreal Protocol ��� an international treaty to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances that are responsible for ozone depletion, such as hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) which may be contained in cooling appliances ��� these refrigerants are still finding their way into the country.

A common trend in the Kenyan second-hand market is the sale of electronics without appliance specifications, making it impossible for consumers to determine the quality of the products they are buying. Without these details, it was impossible to identify the refrigerants present (the compounds that provide refrigeration in air conditioners and fridges) in the appliances sold at Hoist Refrigeration Services, a major dealership in Utawala, along the Eastern Bypass in Nairobi.

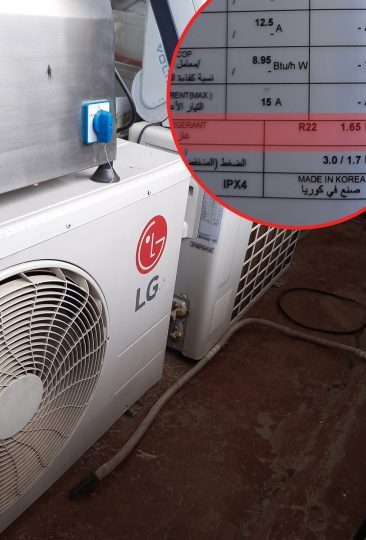

Hoist refrigeration services air conditioner that contain refrigerant R22 (Freon), a refrigerant that contributes to the depletion of the ozone layer and is being phased out. Photo Naipanoi Lepapa.

Hoist refrigeration services air conditioner that contain refrigerant R22 (Freon), a refrigerant that contributes to the depletion of the ozone layer and is being phased out. Photo Naipanoi Lepapa.However, investigations show that the presence of R134a, a hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerant is rife. Although R134a does not pose a threat to the ozone layer because it does not contain chlorine, it is still a potent greenhouse gas with a very high potential to cause global warming and its production is being phased out under Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

���We call it an Ex-UK fridge,��� explains a saleswoman who is clearly ignorant of the chemical makeup of the electronics on display at Hoist Refrigeration Services. ���I have sold so many ex-UK fridges and have never had a complaint about the energy consumption,��� the seller said. But contrary to the seller���s claims, a UNEP report on energy efficiency standards states that Kenyans spend an additional US$50 to US$100 on electricity every year because of using obsolete and inefficient second-hand equipment and appliances.

Banned substancesAn environmental dumping report released in 2020 by the environmental campaign group CLASP and the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development revealed that the air conditioners sold in Kenya contain banned and environmentally harmful substances, with 37 per cent not meeting energy efficiency ratings above 3.0 W/W, a common standard around the world.

According to the report, Kenya imported between 30,000 to 40,000 air conditioners, of which 27 per cent contained R-22 (Freon), a refrigerant that contributes to the depletion of the ozone layer and is being phased out; 4 per cent contained R-32, a refrigerant that contributes highly to global warming; and 69 per cent contained R410a. (One kilogram of this refrigerant has the same greenhouse impact as two tonnes of carbon dioxide.)

The obsolete and harmful refrigerants and appliances were imported from China, Malaysia, Thailand and India.

Tad Ferris, Senior Counsel for the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development and lead author of the joint report, said the units are ���energy vampires���, sucking up vital energy needed to recover from the pandemic and the economic slowdown, and inflating consumer spending on electricity bills.

However, the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) has denied the existence of electronics without labels in the market. In an email response EPRA, which is responsible for monitoring and labelling of quality standards and energy performance of electronic equipment in Kenya, said, ���The Authority does compliance inspections on a monthly basis across the country and has not seen any household refrigeration appliances and split-type non-ducted air conditioners lacking labels.��� The email further said, ���not all cooling appliances are governed by the standards and labelling scheme.���

In Kenya, the energy efficiency label is a red and green tag that awards a maximum of five stars on electronics and electrical appliances such as air conditioners and refrigerators. Minimum Energy Performance Standards are outlined in KS 2464: 2020 by the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS), the country���s quality and standards body. To enter the market, appliances must be inspected and cleared by KEBS and other enforcing agencies, including the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) and Customs.

The Energy (Appliances��� Energy Performance and Labelling) Regulations were introduced in 2016 and promoted by CLASP and the Kenyan government under the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program (KCEP). However, although Kenya has pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 32 per cent by 2030 to comply with the Paris Agreement under the revised National Determined Contributions (NDCs), it has yet to ratify the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal protocol that restricts the production, entry and use of HFCs such as R134a.

Not only do second-hand cooling appliances consume more energy and rely mostly on fossil-based energy to power them, they contain refrigerants that have the capacity to warm the atmosphere thousands of times more than carbon dioxide. A Study shows that the cooling appliances industry contributes significantly to climate change and accounts for 10 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

According to Dr Collins Odote, an environmental lawyer and Associate Dean at the Faculty of Law of Nairobi University, for Kenya to reduce greenhouse emissions and combat climate change, the country must eliminate the importation and use of banned substances, reduce reliance on fossil fuels and use clean energy. Kenya is one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change. The country���s economy depends largely on tourism, agriculture, forestry and fishing, all sectors that are susceptible to climate change, Odote says, adding that the increased temperatures contribute to the loss of billions of shillings through droughts, famine, floods and human displacement.

Bribery and corruptionIn order to get a sense of how these operations run under the radar of the authorities, I presented myself to some of the dealers as a prospective player in the business. It turns out that for bulk imports, which are cheaper, a contact ��� often a relative ��� in the exporting country is required.

Moreover, money to bribe your way out of the port is a necessity some said, and there were allegations that not bribing certain officials could result in clearance delays or impounded goods.

One of the dealers was open to doing business with me against payment of KSh10,000 for a connection to a middleman based in the UK. The deal didn���t go through, however, as a few days later, the middleman declined.

Experts say that rich countries are dumping e-waste in developing countries such as Kenya under the guise of exporting second-hand appliances. Exporting e-waste, non-functioning or near-end-of-life, or environmentally harmful refrigerants is a criminal act under the Basel Convention and the European Union Waste Shipment Regulation.

Yet according to a United Nations University study of transboundary movements of used and waste electronic and electrical equipment (UEEE), between 2008 and 2013, 184 tonnes of used freezers and fridges worth ���1.5 million were exported to Eastern African countries, including Kenya.The study analysed EU exports of second-hand refrigerators, freezers, laptops and desktop computers considered as waste using trade statistics from the EU COMEXT database. The analysis revealed that most exports came from Germany and Great Britain. The study did not capture data on electronics exported unconventionally and therefore the number of cooling appliances could be higher.

This indiscriminate dumping of e-waste from developed countries is exacerbating the problem of e-waste management in Kenya where just one per cent of the 51.3 tonnes of e-waste generated domestically is properly managed and recycled while the rest is discarded carelessly in dumpsites and in rivers, incinerated, thrown into pit latrines or left in homes.

Speaking in an interview, Dr Ayub Macharia, Director of Environmental Education in the Ministry of Environment said, ���Kenya is a victim of illegal movement of e-waste from developed countries.���

To curb dumping of e-waste in Kenya, Dr Macharia declared a ban on the importation of second-hand electronic devices starting January 2020. But the ban mainly affected old cell phones, computers and laptops sent by donors to schools and institutions and not obsolete cooling appliances.

Kenya���s biggest dumpsiteDandora is Kenya���s fourth largest slum and home to the biggest dumpsite in Kenya. It is high noon but the sky here is grey from the swirls of smoke rising from burning waste.

Kevin, a scrap dealer, sits in front of a shack constructed from rusty corrugated iron sheets held together with cable and wire mesh. The middle-aged man agrees to divulge the secrets of his business anonymously.

���A client who imports sells me the broken ones. I get ex-UK, Japan and German-made appliances,��� Kevin says. ���I remove the copper and sell to jewellers or I take the copper to industrial Area, Mlolongo or Cabanas, to be exported to China.���

Kenya does not mine copper but the copper collected at scrapyards like this one is exported to countries like China and the UK, generating significant revenues for the country.

Kevin says he is just a tiny fish in the pond that is Kenya���s copper export market; politically connected people run the big deals. Security operatives visit his shop on a daily basis to collect bribes; he has secretly stashed away a large amount of copper in a storeroom somewhere to avoid exploitation from corrupt ���CID��� officers.

���Utachukua dawa? (Will you buy copper?) ,��� an e-waste scavenger asks Kevin.

The copper trade is flourishing despite the harm caused to the environment and people by the release of refrigerants into the air. Kevin doesn���t have a degassing machine; he doesn���t see the need for one. He leaks refrigerants directly into the atmosphere as he recovers valuables like copper or steel.

���There is no harm. The gases don���t have odour,��� an ignorant Kevin says, adding, ���That is a scientific theory. Even if it had, you cannot compare such pollution with one caused by a motorcycle.���

Kenya does not mine copper, so Kevin cannot get a licence to trade in the mineral. But the illegal trading, the harassment from corrupt government officials and the information that refrigerants cause harm to people and to the climate have not deterred him. Kevin says he���s already teaching his son the business.

���Utachukua dawa?��� (Will you buy copper?), another waste scavenger asks Kevin.

This new business deal brings our chat to an end.

In another area of the dumpsite, James is sitting in his wood and corrugated iron shanty extracting copper from a fridge using a hammer. Around him are sacks containing various bits of scrap. To extract the copper from the appliances, the scavengers around Dandora use crude equipment, exposing other heavy metals and releasing gases into the air in the process. They complain of chest pains that they say are caused by the dark smoke emanating from the dumpsite.

James says he already has KSh200,000 worth of copper in a secret storeroom. The scrap copper is from fridges, construction sites and other sources. He hopes to collect KSh1,000,000 million worth of copper and maybe sell it by the end of the year. The copper will be exported to the United Kingdom, he says.

E-waste scavengers come carrying loads of copper that James weighs and pays for. He cannot tell where the copper brought to him has come from.

As I leave the dumpsite, rain falls from the heavy clouds above. In a few minutes, the water will flow in ditches and find its way into the Nairobi River a few miles away from the slum.

Hazardous substancesScientific studies have confirmed the presence of dangerous elements, such as lead, which present a serious hazard to human health at the dumpsite. A study commissioned by UNEP found high levels of heavy metals in the surrounding environment and in the bodies of local residents.

Lead and cadmium levels were 13,500 ppm (parts per million) and 1,058 ppm respectively, compared to action levels in the Netherlands of 150 ppm and 5ppm for these heavy metals.�� But because of the economic gains that they derive from the business, residents and collectors are not willing to abandon it or to move from the site.

To make matters worse, Kenya ���[does] not have regulations that guide in e-waste management and disposal, we have them in draft,��� says Dr Catherine Mbaisi, Acting Deputy Director, Environmental Education and Awareness, National Environment Management Authority (NEMA).

This means that influxes of obsolete cooling appliances through porous borders will continue to flood the market. According to Dr Mbaisi, the Ministry of Environment has formulated Extended Producer Responsibility Regulations that will render the manufacturer responsible for the entire life cycle of a product including a take-back scheme, recycling, and final disposal. She hopes the bill will be enacted.

Controlled Substances Regulations 2020 have also been formulated but have yet to be enacted. The regulations will promote the use of ozone-friendly substances and products, and ensure the elimination of those that deplete the ozone layer. They need to be urgently enacted because lack of regulation and the lax control of energy-hungry, toxic goods is putting Kenyan lives at risk and harming the environment.

This article was developed with the support of the Money Trail Project. Additional research by Leslie Olonyi.

November 18, 2021

Organic intellectuals

Still from video.

Still from video. This video is from our series Capitalism In My City, presented in partnership with the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, Kenya.

This video is part of the project that Mathare Social Justice Centre, Ukombozi Library and the Organic Intellectuals Network within social movements in Nairobi have organized through Capitalism in My City to strengthen radical political consciousness in Nairobi City.

This video depicts the rise and growth of political consciousness and social justice intellectuals in Mathare, and informal areas around Nairobi. These comrades are motivated to master the art of political freedom and spread its knowledge to the vast majority of inhabitants in these areas. Many of the people interviewed in the video are human rights champions and community organizers.

The interviews took place in the Ukombozi library, a progressive African library in central Nairobi that offers access to reading material of political struggles in Kenya and other parts of Africa. The library has shaped these budding, organic intellectuals and the material they write while reviewing radical books about the history and struggle of the working class in Kenya.

November 17, 2021

You came here on a fucking boat

"You came here on a fucking boat," by Tyra Naidoo. Used with permission from the artist.

"You came here on a fucking boat," by Tyra Naidoo. Used with permission from the artist. This post forms part of the work by our 2020-2021 class of AIAC Fellows.

In South Africa, the past is not yet done with us. For two weeks in July 2021, South Africa was on fire. KwaZulu-Natal province and certain parts of Gauteng saw untold damage, food shortages in certain areas and a level of disaster that has left most in the country speechless. The fire was ostensibly triggered by corrupt ex-President Jacob Zuma being sentenced to jail time, but there is never only one reason for collective anger. It was also connected to the measures to curb the deadly COVID-19�� and how these exacerbated already fraught socio-economic dynamics in the country. On a micro-level, thinly veiled antagonisms�� between the rich and the poor, between Black and Indian South Africans have come to the surface, yet again.

My world is in Durban. I live in Johannesburg, but like many KwaZulu-Natal transplants, my family lives in the coastal province, in working class areas that saw gun fights, fires, food shortages and death in mid-July. As family group Whatsapps urgently pinged in���some containing recycled images and footage from previous moments of disaster, others sharing resources about which neighbor or mosque is distributing bread���feelings of precarity have come to the surface for many Indian South Africans in KwaZulu-Natal. The messages have gone from fear and worry over shops, malls and markets looted to fears about petrol bombs being thrown into yards, increased home robberies and strangers with pangas driving through different units shouting ���wake up motherfuckers.���

There is video footage of Indian South Africans in working-class towns like Phoenix assaulting and killing Black people.

Sandile Ntuli lives in Phoenix with his aunt and uncle. On July 12, Ntuli and a friend went to find petrol. They knew that with violence and looting would come food and fuel shortages. That evening, they went to the local Total garage (gas station), only to find it closed. A short while later, they met a friend on the road, also in search of fuel. The friends drove in convoy to a Shell garage in the area but the road was barricaded. Ntuli was let through, but his friend in the car behind him was stopped, and the armed Indian vigilantes manning the barricade started assaulting him. Ntuli knew some of the attackers and shouted ���Hey, everyone knows us. We all went to school together!��� That is when the bullets started flying. Ntuli was shot in the leg as his friend drove them to safety.

On that same evening, another Phoenix resident, 19-year-old aspiring photographer Sanele Mngomezulu, was coming back home after taking part in the widespread looting. The Quantum taxi van he was in was met with a hail of bullets, as an Indian neighborhood watch group opened fire on the vehicle. All the people in the taxi fled but one person was shot and killed in the attack���Mngomezulu. His murderers torched the vehicle and left his body on Trenance Park Road in Phoenix. His mother Thokozani Ntwenhle Mhlongo mourned his death at her birthday in early August, wondering about the exact circumstances of her son���s murder, with justice seeming a far-off prospect. ���They keep speaking about property, but my son was looted,��� said Mhlongo. ���I just want justice for my son.���

Other Black people in Phoenix, Chatsworth and other so-called Indian areas faced similar racial profiling, thuggery and murder at the hands of their Indian neighbors, ex-school friends and employers. Police Commissioner Bheki Cele released an official count of those who were killed in Phoenix. The state noted that 36 people died in and around Phoenix, however, those like Sanele Mngomezulu are not on this official list. In total, the media reports that 342 people across KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng died in the unrest.

As the dust settles and the state narrative of ���rebuilding��� is parroted by ward councillors and residents alike, there are still no coherent narratives about what happened in Phoenix. What we do know is that Black South Africans were killed, many by Indian South Africans. How do we make sense of these acts of violence, motivated by anti-black racism and others whose motivations are still obscured by the event itself?

Indian South Africans occupy a liminal place in South Africa as an early racialized insider-outsider. To understand how they came to attack Black South Africans in 2021, it is important to understand the feelings of physical and existential vulnerability that have shaped Indians��� experiences since their arrival first as slaves in the years after 1652 in the Cape of Good Hope (many from this migration have formed part of creolized communities racialized as Coloured), and then as indentured laborers in the 19th century. While the chaos of July may have felt new to some, the roots of the present-day conflict lie in that history, and most specifically with the events of 1949.

1949January 13, 1949 was a typically humid day in central Durban. The sluggish weather was a precursor to an event with many names���some call it the 1949 Riots, or the Durban Riots. The events were sparked by a fight between a Black news-seller named Madondo and Indian shopkeeper Basnath.

There are contested versions of who did what to whom, yet it is clear that after the young men began brawling, black vendors and commuters came to Madondo���s assistance and Indian shopkeepers and women who lived above the shops where the melee broke out threw missiles from apartment blocks and rooftops. From first-hand accounts, everyone watching took a side and they based their decision largely on race.

The outbreak of violence between Blacks and Indians living and working in this densely packed area of Durban escalated and by nightfall it had spread to other parts of the city. Police sent reinforcements to quell the skirmish but such was the intensity of the fighting that they struggled to control the crowds. Finally, as a thunderstorm blew in close to midnight, the streets quietened.

Over the next few days, the tensions were exacerbated by police and state officials. Just one year after apartheid had been officially adopted as the law of the land, accounts from Black and Indian witnesses attest that white policemen, in blackface, joined in on the looting and actively instigated violence.

What had begun as racial tension was quickly exploited by authorities and turned into a virulently anti-Indian pogrom, as historian Jon Soske names this event. Indeed, just three years earlier, the Ghetto Act had been passed in order to prevent Indian property ownership in white areas. As Ronnie Govender���s much-lauded play, 1949 shows, white people were worried about a so-called Asian Menace. In the play, white employers spread xenophobic sentiments �� based on their fears of an Indian ���takeover.���

Eventually the riots came to an end and the casualties were counted. Apartheid police and individuals involved in the skirmishes had killed 87 Africans and 50 Indians, and left one European dead. 1,087 people were injured and 40,000 Indians were rendered homeless. More than 300 buildings were destroyed and 2,000 structures damaged.

These were numbers reported by the apartheid state, and Black and Indian newspapers of the time contested the numbers of lives lost and causalities, arguing that the toll was far higher. Still, it is evident that the events had a significant effect not just on those who were killed and injured, or whose property was destroyed. There was a long-lasting effect on Black-Indian relations.

To be sure, the riots were a violently xenophobic response to anti-Black racism amongst some in the Indian community. As Black newspapers like Ilanga and Inkundla pointed out at the time, many Black people were frustrated by the racism they experienced from Indian property and business owners. At the same time, the level of violence and its indiscriminate targeting of all Indians���especially those who lived in poor communities and did not necessarily have the power or authority to exploit Blacks in the way that upper class Indians did��� reflected broader ideas about all Asian communities being alien in Africa and encroaching on highly contested urban spaces. Furthermore, there was widespread resentment amongst Africans about the fact that Indians occupied a more advantageous position in the newly formalized racial hierarchy.

These tensions served as the backdrop to the riots.�� And it was these tensions that were exploited by the newly instituted apartheid state, as it sought to cement its power by its divide-and-rule tactics. The tensions were of course fed by a sustained campaign within the media. White newspapers feared the trade and property accumulation of immigrant Asians in Natal, and Black newspapers, whose readers were being increasingly disenfranchised through white rule and pushed out of the city, often responded with a growing anxiety towards Indian communities. Both, although not in unison, espoused the view that Asians in Africa were non-indigenous and, as always, potentially replaceable.

In A History of the Present, academics Goolam Vahed and Ashwin Desai refer to psychic afterlives of the event through the words of journalist Ranji Nowbath.

Those who have seen their homes destroyed in front of their eyes, those who have seen a lifetime���s savings go up in smoke, those who have seen their children hacked in front of them, and those who helplessly watched their daughters raped, will not, they cannot, forget.

The anti-Indian pogrom serves as an enduring and far too relevant example of the real-world repercussions of political fear mongering. The state���s construction of Indian people in the country was contingent on non-indigeneity, meaning the violence meted on them was a natural result of overstaying their welcome. Indian people were scapegoated, seen as a target for frustrations about socio-economic conditions in the country���a rhetoric that���s often been used against African migrants in post-apartheid South Africa.

The year 1949 is a useful starting point���not in comparison to the events of July, 2021���but as a lesson in how a middleman minority, or a ���buffer race��� as Mahmood Mamdani puts it, are often most easily accessible targets of economic frustration, due to proximity. This is also influenced by conflations of Indian South African communities as agents of white monopoly capital, without understanding the differential effects of white supremacy and capitalism on these communities. The affectual thread runs from 1949 to today.

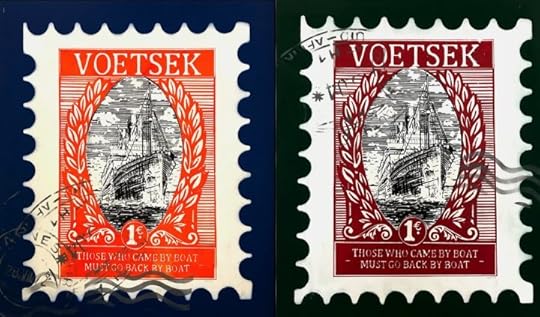

Those who came by boat���Voetsek. Those who came by boat must go back by boat,��� the artwork reads. Minenkulu Ngoyi���s aerosol and silkscreened post stamp piece, is titled ���Said a member of the EFFSC.��� The Economic Freedom Fighters Student Command is the student branch of the South African political party the Economic Freedom Fighters���a party more aligned with ���an economic nationalist front��� according to writer William Shoki, than a left-wing, radical political party.

When I saw this piece at an art fair in 2019, I tried to reassure myself, to minimize the shame of non-indigeneity in post-apartheid South Africa by insisting that it was intended only for European settlers. Maybe it was, but this question of legitimacy has trailed me my whole life, as it does most Indian South Africans. I have often been seen as a tourist in the town I grew up in. I have been called coolie on a playground. These are quotidian experiences of displacement; everyday reminders of non-belonging.

AmaKula (a derogatory isiZulu slang word for Indian people derived from the word ���coolies���) is a popular way to refer to those of South Asian ancestry in South Africa.

Before South Africa���s COVID-19 restrictions kicked in, I was working as a part-time sub-editor in a local newsroom. While we ate our lunches at our desk, the conversation shifted to the word ���amakula.��� My colleagues, some of whom are friends and mentors, were Black and the conversation circled around whether amaKula is a racial slur as some Black communities simply use the word as a racial descriptor. A few people didn���t know the words��� episteme in ���coolie,��� and the histories underpinning its usage in colonial and apartheid times. I explained some of these histories through gritted teeth���confused that I had to explain this to people I felt should know that the word is analogous to the k-word in South Africa. The apartheid hierarchy of races was invoked with some wondering how Indian South Africans could be referents of racial slurs or abuse as their position was just below whites and above everyone else.

In response, a colleague said her mother uses amaKula to describe Indian South Africans because these communities are racist, so why should the offer of non-racist speech be extended to those who see Black people as inherently inferior? She quickly added that she���s tried to address it but her mother���s experience of racial profiling and abuse from Indian South Africans was not something she was willing to forgive or reconcile. I acknowledged that her mother should feel what she does and that I am sorry. Feeling tears well up, I went to the bathroom. The hopelessness of Black and Indian South Africans seeing each other as people with differential but intertwining histories of subjugation and living under white supremacy felt too much to bear at that moment.

Tyra Naidoo, a friend and Indian South African artist was told by a Black student during the Rhodes Must Fall protests at University of Cape Town that she should stay out of these politics because: ���What do you know? You came on a fucking ship.��� The comment stung. Our sense of belonging made contingent; our place in Africa dependent on the mode of transport our ancestors used to get here. Naidoo, in reflection and reclamation created the artwork ���You came here on a fucking boat,��� a sinking cement-cast boat mirroring those that transported indentured labourers to Durban���s shores.

It is in fact the case that the relatives of all Indian South African people who descended from indentured laborers, and passenger Indians did come on ships.�� But to create an equivalence between their journeys here, and those of Europeans who came on ships seems disingenuous at best. Surely the weight of history bears down differently on those whose ancestors were coerced here and those who arrived as part of so-called civilizing missions. The first ships carrying indentured laborers landed in 1861 and the last ship arrived in 1911. The indentured laborers they carried were often kidnapped and coerced by British colonists, and their Indian recruiters���the arkatis���in India. Those who chose to leave had often transgressed social or religious norms in India (such as falling pregnant before marriage, loving or marrying across caste or religion), had been cast out of their social networks in India, and felt pressured to leave. .

Personal accounts from indentured laborers show that many of them were tricked���the contracts they thumb-printed were never properly explained to them and most did not know the brutality that awaited them on the sugar plantations, dairy farms, coal mines and railways they were being recruited to work on.

The Europeans who arrived by boat���those descended from the 1652 fleets and those who arrived after 1820, developed a strict hierarchy of belonging. White South Africans have a long history of monopolizing decisions about who belongs in this country, and who doesn���t. If colonial conquest was not enough to demonstrate this, the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910 was predicated on a pact between Afrikaners and British descendants, whose only similarity was the color of their skins. They had been bitter enemies, until that point, but they came together politically and thereafter economically, in order to build a country in their own image and was governed for their benefit only. In 1948, the apartheid system strengthened the racial pact and codified it in ways both nightmarish and banal. The year 1994 was supposed to present us all with a rupture in these exclusions. The post-apartheid vision was embedded in the first lines of the constitution, ���South Africa belongs to all who live in it.���

More recently, in some quarters, belonging has become linked to indigeneity. The EFF and some in the ANC, as well as some who espouse colored identity politics, profess this brand of politics. The question of authenticity is central to how we see the struggles of South Africans of South Asian ancestry in relation to the struggles of people perceived to be African migrants. Both groups have repeatedly been forced to ���prove��� their allegiance to the country based on ideas of loyalty that have been deeply linked to indigeneity. Ironically, the categories into which both groups have been shoe-horned are inventions; created by colonizers and adhering to colonial logic.

The boundary lines of the South African state were dictated by the British who also decided on the borders of Zambia, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Nigeria���countries whose citizens have been targeted in xenophobic attacks since 1994, when many blue-collar workers from neighboring African states moved to South Africa.

Prior to the arrival of indentured laborers, ���until the beginning of the twentieth century in South Africa all people that were not considered to be ���European��� or ���Black��� were regarded as ���colored.���,��� academic Kathryn Pillay notes. ���The South African state,��� she argues, ���between 1948 and 1994, set limits to the identity choices of ���Indians���.��� Anti-Indian legislation started as early as 1885, with any of the ���native races of Asia��� being disbarred from ���burgher rights��� (citizenship) in the then-Transvaal. This was swiftly followed by other acts and ordinances which restricted Indian movement within and out of the country and payments of taxes and penalties for contravening sanitation or trade laws.

The term ���coolies��� was not the only one applied to racial groups invented by colonizers, of course. They invented the very notion of Africans, who until the arrival of colonizers were distinct ethnic groups with different languages, cultures and histories. When white people placed themselves as the center of human identity, with all other racialized peoples defined in relation to them, they began the process of arbitrarily inventing racial categories���including their own racial category of ���white���. Then there were communities racialized as a colored, whose complex and generational creolization put them in a situation of conditional indigeneity. They were a racial invention too, a product of relations that could not be named given the racial boundaries white settlers had created to maintain racial ���purity.��� The fact that these groups were a complex socially inscribed fiction required their boundary lines to be heavily policed. Hence apartheid laws like the Population Registration Act and the Group Areas Act had to be enforced with violence.

The racial hierarchy then influenced who was seen as foreign and who belonged. White people���as the inventors of the system of apartheid���occupied the center. They belonged here without question. They conceded that some Black people belonged also, albeit in prescribed areas that were in line with racist ideas about tribe and ethnicity. Indians on the other hand, had another home (India) to go to. As the National Party election manifesto states:

The party holds the view that Indians are a foreign and outlandish element which is unassimilable. They can never become part of the country and must therefore be treated as an immigrant community.

Indian population groups are the recognizable other. The Mercury editorial, the settler newspaper of the time, noted the group as a ���very Oriental-looking crowd.��� The British colonial regime, the Union of South African and the apartheid government made it clear through anti-Indian and immigration legislation specifically directed at Asian communities, that South Africa was not our home, and through colonial and apartheid-era media and political discourse, this became the narrative of South African ���Indianness.���

1985In many ways, the events of July demonstrate the racial politics of being a middleman minority. White communities, although also protected by neighborhood watches and patrols, have not experienced the level of destruction seen in racialized communities. There were Indian areas, communities racialized as colored and white neighborhoods that denied Black people entrance to shops, roads and residential areas because of fear predicated on racism. But, the vitriol directed against Indian people as a whole during this time elides many modes of being in Phoenix and areas like it.

Shack-dweller movement Abahlali baseMjondolo surface some of these erasures, citing the work of the Phoenix Residents��� Association, the strong links between Africans of Indian descent with the work of Abahlali and in earlier housing struggles around Durban in the early 2000s. Importantly, they highlighted the local level politics of private security companies and wealthy Indian drug lords and gangsters, who are often involved in evictions, killings and assaults in the area and who Indian and Black residents alike live in fear of.

The events in Phoenix did not transpire out of thin air, and this was not the first time Indian vigilantes policed the borders of the settlement Gandhi created. ���The battle lines formed between Phoenix and Inanda, with Indian vigilantes arming themselves in preparation for an attack on Phoenix,��� writes sociologist Ashwin Desai about the protests and riots of 1985. The resemblances to 2021 are eerie. The events of Inanda, 1985, are etched into the minds of many Indian South Africans who live on KwaZulu Natal���s North Coast���for many of the same reasons 1949 is.

On August 1, 1985, Victoria Mxenge was assassinated by government death squads outside her home in Umlazi. She was a well-loved and respected comrade, fighting apartheid injustices over decades. In response to her murder, a schools strike and boycott, organized by Umlazi youth, spread quickly through Black townships in KwaZulu-Natal. KwaMashu, Lamontville and Inanda all saw protests against the apartheid government.

A few days after the assassination, two homes owned by Indian people living in Inanda were burned down. This led to an exodus of Indian shopkeepers and residents who either lived through 1949, or knew those who did. The displaced people went to their closest neighborhood���Phoenix���for safety. Phoenix and Inanda share a porous boundary. Families and working relationships often cross this boundary and the demarcations were largely predicated on race. A week after the two homes were burned down, 42 shops and homes owned by Indians were destroyed. Two thousand Indian people were displaced, and sought shelter in Phoenix. Black homes and businesses in Inanda were left untouched.

Inanda���s violence, as Desai explains, needs to be understood in the context of the general political turbulence of 1980s KwaZulu Natal. In other townships, African-owned businesses and homes were targeted and destroyed. But in Inanda the tone veered towards anti-Indian rhetoric. This is due a complicated network of Inkatha-aligned fighters (the Zulu nationalist group clandestinely funded by the apartheid state at the time) getting involved to quell the UDF-aligned unrest, and having vested interests in expanding their influence in Inanda. The violence in Inanda was multi-causal and although expressed in some anti-Indian ways, it cannot wholly be described as such because of the youth���s push back of Inkatha forces who they viewed as ���surrogates of the South African state.��� There were anti-apartheid elements of the violence, as well as anti-Indian and opportunistic elements. Writes Desai,

Why would an indigenous majority strike out at a disenfranchised minority rather than at a white ruling class which, after all, set the rules of the game? This has much to do with the structural location of the middleman minority, with an immediate relation to the indigenous population as buyer and seller, renter and landlord, client and professional.

The events of 1985, like 1949, placed Indian South Africans in a precarious position���with the memories of the earlier event compounding feelings of insecurity and displacement. The logics of xenophobia���profiling Indians as stealing land, jobs and opportunities from indigenous populations, Indian shopkeepers as symbolic of privilege, easily expendable and expelled���work hand-in-hand with the tribalism espoused by Inkatha at the time. As with 1949, White South Africans remained above the system, untouched by the violence their ancestors authored.

Many lives were lost on both sides of these riots, and for Indians, it became an abiding memory of fear and sense of vulnerability. The 1985 riots, while not leading to the same violence, immediately raised the spectre of 1949. As in 1949 and 1985, it is a time in which the great expectations of democracy in 1994 have not materialised for the vast majority of South Africans. An insular Indian community meets a resurgent racial nationalism with tribal overtones. It is in this context that the middleman thesis of scapegoating and vulnerability has great resonance.

In constructing Indians as outsiders to African racial nationalism, the hierarchies and dynamics remain intact. A sense of Indian South African racial superiority, built on apartheid logics and class position is one of the reasons this continues. Another, and arguably more potent force, is the insularity Indian communities have actively fostered over time: a secret society with religious, cultural and social dynamics most other racial groups are deliberately not privy to. While closing off can be read as a reaction to the dangerous and violent underlying discourses of otherness and alienness surrounding Indian communities since their indentured arrival, it also undermines the efforts of Black and Indian anti-apartheid and grassroots community activism to heal the ruptures between these two groups.

In the aftermath of 1949, the Black political class in the African National Congress and South African Indian Congress sought to forge better relationships with each other and to struggle together, although this was often in conflict with both constituencies feeling unheard by their political parties, as Jon Soske has noted in his study of non-racialism as politics in South Africa.

Indian South African solidarity with Black South Africans has a long and storied history in the country���anti-apartheid stalwarts such as Yusuf Dadoo, Fatima Meer, Pregs Govender and Ahmed Kathrada come to mind. But I find the work of contemporary community activists, such as the Phoenix Residents Association, Abahlali baseMjondolo and even the 1860 Heritage Center, more important to this post-July moment and the forging of true cross-racial solidarity.

After the July unrest, the 1860 Heritage Museum, which is dedicated to the history of Indian indentureship in South Africa, started a conversational Zulu course. More initiatives like this need to happen. Conversation and language are key elements of dismantling the festering racial hierarchies between Black and Indian South Africans; of both seeing each other as people. One way of wading through this quagmire of anti-Blackness and ethno-nationalism is through honest and uncomfortable dialogue. In this space, conversations between Black and Indian South Africans that are both rigorous and informal, sustained and anecdotal. Cross-racial solidarity must be an on-going process that is not dictated by political elites. As academic and poet Vivek Narayan urges us in his reflections on 1949, ���we must begin to make better use of our multiple positions, and to transgress spaces and silences���carefully ���if we want to build and imagine a truly cross-cultural [and cross-racial] world.���

�� ce que font deux hommes ��

Photo by Edouard TAMBA on Unsplash

Photo by Edouard TAMBA on Unsplash Le 08 f��vrier 2021 �� 20h �� la suite d���un appel anonyme, la police de la communaut�� urbaine de Douala a effectu�� l���arrestation de Lo��c Jeuken dite �� Shakiro �� et Roland Mouthe dite �� Patricia ��, deux femmes transgenres dans un restaurant de Bonapriso���un quartier r��sidentiel hupp�� du premier arrondissement de Douala (Cameroun).

En l���absence de cartes d���identit��s, elles ont ��t�� conduites au commissariat, puis mises en garde �� vue pendant 24heures ou elles ont ��t�� tortur��es, priv��e d���une visite familiale et d���un avocat. Apr��s avoir consulter le contenu des t��l��phones saisis, les gendarmes ont obtenu des photos et des messages �� caract��re sexuels. Par la suite, elles ont ��t�� conduites au tribunal de premi��re instance de Bonanjo sans avocats, ou elles ont ��t�� oblig��es de signer des aveux et puis condamn��e �� 2 ans d���emprisonnement pour �� tentative d���homosexualit�� ��, et ��absence de carte d���identit�� ��. Enfin, c���est dans les quartiers des hommes �� la prison central de New-Bell (Douala), qu���elles ont ��t�� incarc��r��es depuis le 9 f��vrier 2021. �� Shakiro et Patricia ont finalement ��t�� condamn��s �� 5 ans d’emprisonnement chacun plus 472 000 francs CFA d’amende pour “tentative d’homosexualit��”

Selon les activistes des droits humains et les membres de l���organisation non gouvernementale (ONG), Working For Our Wellbeing Cameroon, qui ont pris en charge l���affaire Shakiro et Patricia �� la veille de leur arrestation. Cette situation est potentiellement le lot quotidien des minorit��s sexuelles et de genre dans les 10 r��gions du pays. �� diff��rentes ��chelles, nombreux et nombreuses sont celles et ceux qui naviguent entre les d��nonciations et les suspicions d���homosexualit��, les chantages, les agressions physiques et verbales de la part de partenaires, des proches, des membres de la famille sans compter au mieux les humiliations dans le monde m��dical, juridique et ��ducatif.

Historiquement, la place des minorit��s sexuelles et de genre (MSG) dans le Cameroun pr��colonial ��tait codifi��e et s���inscrivait dans des r��les sociaux, culturelles et religieux d��finis. C���est dans les ann��es 90, qu���apparait quelques sc��nes gays principalement compos��s des hommes ��duqu��s, des classes ais��es et urbaines de Yaound�� et Douala. Nombreux alors, se d��finissent comme Nkoandengu�� �� la place de �� gays �� ou �� Queers ��. Les Nkoandengu��s,����� ce que font deux hommes �� en langue Ewondo���pendant longtemps restent relativement prot��ger des politiques homophobes qui impactent plus grandement les moins privil��gi��s, ne disposant pas d���un capital socio-��conomique important.

Le sentiment de protection que jouit les Nkoandengu��s, disparait au d��but des ann��es 2000 lorsque commence des �� chasses �� l���homme �� et des d��nonciations publiques, parmi lesquels l���on compte l���affaire du �� Top 50 ��. Le 11 janvier 2006 �� Yaound��, le journal La M��t��o publie un article intitul�� : �� l���homosexualit�� dans les cercles de pouvoir ��, assorti d’une liste de onze personnes. Dans la m��me salve, le 24 janvier de la m��me ann��e, L’Anecdote, publie, �� sa une�� �� une liste de cinquante homosexuels hauts plac��s �� et ce sont largement, des personnalit��s publiques et connues y figurent.�� L���on y trouve notamment un ancien premier ministre, des parlementaires, des journalistes renomm��s et des c��l��brit��s qui pour beaucoup porteront plaintes pour diffamation. Dans la grande majorit�� la liste est compos��e d���hommes���les femmes y sont quasiment absentes. Ces d��nonciations publiques sont par la suite reprises par d���autres journaux, et depuis 2006, nombreux sont les m��dias qui ont fait des �� listes d���homosexuels ��, une culture journalistique camerounaise.�� Plus d���une d��cennie apr��s, �� les accusations d���homosexualit��s �� sont pr��sents dans les d��bats soci��taux et politiques.

De nos jours, l���utilisation des appellations telles que lesbiennes, gays, bisexuelles, trans, queers, intersexes et asexuelles dans le vocabulaire des minorit��s sexuelles et de genre du pays apparaissent comme un outil d���affirmation (r��elle ou suppos��e) d���une appartenance �� une classe sociale mais aussi d���un niveau acad��mique. Ces nouvelles appellations, voient le jour majoritairement dans les ann��es 2000 marquant un d��sir plus large de s�����manciper de l���homophobie ambiant et de reproduire plus largement un mode de vie des classes sociales ais��es et queers des pays du Nord���suppos��ment plus respectueuses des droits et des libert��s individuelles.

L���homophobie contemporain s���est si bien culturellement install��e durant et apr��s la colonisation, qu���elle fait consensus et f��d��re la soci��t�� camerounaise dans toute son enti��ret��, au point de devenir une �� homophobie sociale ��. Dans la culture du divertissement, la figure de l���homosexuel���un homme �� eff��min�� �� et �� mani��r�� �����est perp��tuellement moqu��e. Dans leurs chansons et vid��o-clips, des musiciens tels que Petit-pays dans son fameux titre �� Les p��d��s �� ou derni��rement Happy dans le titre �� Tchapeu-Tchapeu �� font ouvertement l�����talage d���une homophobie assum��e et qui apr��s des d��c��nies s���est bien ��tablie dans la pop-culture camerounaise. Au-del�� de l���industrie du divertissement, l���homophobie rev��t un enjeu politique et religieux. Elle rev��t un caract��re politique car pouss��e par des leaders et des rh��toriques politiciennes notamment lors des p��riodes ��lectorales mais pas uniquement, elle est le signe d���un acte militant, d���un rejet de l���imp��rialisme et de la colonisation culturelle de l���occident. Parall��lement, elle rev��t un caract��re religieux quand elle est pouss��e par des personnalit��s et des rh��toriques religieuses des deux grandes religions abrahamiques du pays. Dans ce contexte, il s���agit d���un acte de religiosit�� et d���une r��action de rejet d���un �� p��ch�� �� qui serait la cause des malheurs du peuple, des crises ��conomiques, de la mal-gouvernance etc.

Dans les faits, bien qu���interdit durant la p��riode coloniale (allemande, anglaise et fran��aise), les premiers textes relatifs �� la r��pression des minorit��s sexuelles et de genre au Cameroun, ind��pendant et puis uni en 1972, sont introduits unilat��ralement dans le premier code p��nal camerounais en tant que d��lit, par le pr��sident Ahmadou Ahidjo sous son deuxi��me mandat. C���est via une ordonnance du 28 septembre 1972 qu���entre l���article 347 bis dans le code p��nal, devenue 347-1 au courant des ann��es 2000. Elle stipule : �� Est punie d���un emprisonnement de six (06) mois �� cinq (05) ans et d���une amende de vingt mille (20 000) �� deux cent mille (200 000) francs, toute personne qui a des rapports sexuels avec une personne de son sexe ��. Pour les membres de Working For Our Wellbeing Cameroon, dans un pays ou le salaire minimum est de trente-six mille deux cent soixante-dix (36 270) Francs, sans le soutien des ONG, beaucoup de personnes queers et pauvres finiraient en prison, un environnement particuli��rement dangereux.

Sous pr��texte de lutter contre le terrorisme notamment de Boko-haram dans le nord sah��lien, en 2010, la loi sur la cybers��curit�� et la cybercriminalit�� est impl��ment��e. Loin de criminaliser uniquement les terroristes, elle criminalise aussi les minorit��s sexuelles et de genre dans la sph��re digitale. Elle stipule en son article l���article 83-1:

les propositions sexuelles faites �� une personne de son sexe, est puni d���un emprisonnement d���un (01) �� deux (02) ans et d���une amende de 500.000 (cinq cent mille) �� 1.000.000 (un million) Francs CFA ou de l���une de ces deux peines seulement,�� celui�� qui par voie de communications ��lectroniques, fait des propositions sexuelles �� une personne de son sexe [ les peines ] sont doubl��es lorsque les propositions ont ��t�� suivies de rapports sexuels.

C���est sur le fondement de cet article que Roger Mb��d�� a ��t�� emprisonn�� en 2011 apr��s avoir ��crit �� Je suis tr��s amoureux de toi �� �� un homme.

Produit de la jurisprudence, la �� tentative d���homosexualit�� �� sort du cadre l��gal initialement pr��vu par la loi de 1972. En effet, pour les architectes de cette loi, nul ne pouvait dans la pratique ��tre condamn�� pour homosexualit��. Dans les faits, la preuve de flagrant d��lit ��tait difficile �� obtenir puisqu���elle n��cessitait la violation du droit �� la vie priv��e et la protection du domicile. Ainsi, pour contrevenir �� cette difficult��, les juges et les policiers ont dans la pratique rapidement introduit la suspicion comme preuve d���une �� tentative d���homosexualit�� ��, rendant m��me possible des d��nonciations anonymes par des tiers.