Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 111

December 9, 2021

Back to the future

At the Mau Mau memorial monument. Image credit Jothee via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

At the Mau Mau memorial monument. Image credit Jothee via Flickr CC BY 2.0. Mau Mau histories continue to be either silenced, rewritten or confined to the past by those in power. But the haunting narratives of those Mau Mau veterans who remain, and the angsts of their grandchildren and great grandchildren, amplify the grievances that prompted these original freedom fighters to take up arms: the demand for land and freedom. This post is part of a��series of republications from The Elephant, curated by one of our editorial board members, Wangui Kimari.

Mau Mau has always been a dangerous topic in Kenya. Marked by the brutality of the British counterinsurgency against it, Mau Mau is acknowledged by historians to have been simultaneously a nationalist war of independence, a peasant revolt, a civil war within the Kikuyu ethnic group, and an attempted genocide of the Kikuyu people. This plurality of meanings, which successive generations of citizens, politicians and historians have attempted to smoothen out and fit into neat categories, refuses to be tamed. Instead, the struggle for Mau Mau���s memory continues unabated, with little sign of a ceasefire.

The general contours of the Mau Mau war are widely accepted. On 20 October 1952, the Colonial Office declared a state of emergency in Kenya in response to the growing threat posed by the Mau Mau, a revolutionary military group, who had taken up arms in the forests of the central highlands, demanding ���land and freedom.��� Primarily involving the Kikuyu, Embu and Meru ethnic groups, but also the Maasai, the Luo and Kenyan Indians, among others, the uprising tore through central Kenya, sweeping up not only the guerrilla fighters hidden in the forests and their British adversaries, but entire communities. Forced to pick between Mau Mau adherence and ���loyalist��� British allegiances, both of which carried immense personal and ideological risks, rural communities were set ablaze���sometimes literally���as the war ripped families apart and forced people to choose sides in an increasingly complex and violent conflict.

By the most conservative estimations, tens of thousands of people died, mainly Mau Mau fighters and supporters, but also African ���loyalists��� and a few white settlers. Many hundreds of thousands more were forcibly displaced by the fighting, and by what was termed ���the Pipeline,��� a systematized network of concentration camps and forced villagisation that set out to quash the movement by ���converting��� Mau Mau adherents into loyal colonial subjects by any means necessary. By 1957, after the capture and execution of Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi, and with the majority of the forest fighters dead or interned, the war was officially over. However, the violence continued.

Shaken by Mau Mau���s surprising military and ideological resilience, and determined to ensure that nothing like this would ever happen again, the colonial government doubled down on the Pipeline system, detaining, and often brutally torturing anyone suspected of harbouring Mau Mau sympathies. In the ensuing decade, it became clear that the rebellion had been quashed. But the writing was on the wall, underlined by the scandalous revelations of the colonial government���s conduct, Kenya���s independence was inevitable and urgent.

As one struggle was ending, however, another was just beginning. Now, the race was on for ownership of Mau Mau���s history. For the British, that meant Operation Legacy, a systematic destruction and removal of all evidence of their criminal conduct during the war. For the incumbent post-independence government, it meant carefully curating a Mau Mau narrative marked more by silences and omissions than by commemoration of the events of the war.

For the hundreds of thousands of citizens who were survivors of the war, it meant finding ways outside of the public history-making to process the trauma and preserve the memories of the war. While the British government has been rightly condemned for its attempts to cover up the atrocities they committed and commissioned during the war, far less has been said of the Kenyan government���s complicity in the public silences around Mau Mau. For Jomo Kenyatta and his government, the past was a politically dangerous topic that needed to be carefully managed. Mau Mau, he proclaimed, was not to be discussed, and the organisation remained a banned terrorist group. The last holdouts in the forests were rounded up and persuaded to surrender, or arrested, and those who spoke about the movement publicly outside of officially sanctioned narratives often ended up in prison, in exile, or in the morgue.

Mzee Kenyatta���s mandate was clear: Mau Mau was to be forgotten, and not to be discussed publicly. The organisation remained an illegal terrorist group throughout the Kenyatta and Moi eras, and was only legalized after Mwai Kibaki���s inauguration in 2004. The ���forgive and forget��� policy of Kenyatta and his successor had several interlinked purposes. A generous assessment is that Kenyatta wished to promote national unity and to focus on a shared future rather than a divided past. However, this is only part of the truth. Personal interests needed to be protected, especially those of former loyalists who now held top government positions. In addition, land justice and redistribution, the key demand of the Mau Mau, and later the Kenya Land and Freedom Army���which emerged after the war, and named among its members many Mau Mau hold-outs���would not be a cornerstone of the post-independence political policy. In fact, many veterans returned from forests and camps to find that what little land they did have had been taken from them, and that the only recourse for them to regain it or acquire new land would be to buy it from the government.

Since Mau Mau had been a full-time commitment, and concentration camps did not award salaries, while loyalist Home Guards were paid, an inequity emerged between those who were able to afford land and those who weren���t, which fell along lines of allegiances during the war. A final reason for Kenyatta���s desire to silence any public discussion of Mau Mau was that British interests still needed to be protected. If Kenya wanted to emerge from the 1960s as part of the global economy, it would have to dance to the tune of its former colonizers, which meant not embarrassing them with tales of their past atrocities. All in all, it would be better to forget the whole sorry affair.

In practice, this meant a careful selection of which fragments of the truth of Kenya���s Mau Mau past could be discussed and by whom. As a student of Kenya���s national curriculum, if you learned anything at all about the history of decolonisation, it adhered to a specific narrative: colonialism came to an end when Jomo Kenyatta and other brave constitutional nationalists came to an agreement with the British. Depending on your age, you may also have learned the names of some long-dead Mau Mau heroes and heroines who helped win Kenya���s freedom.

Certainly, there would not have been any discussion of the ideological roots of the Mau Mau movement, rooted in land justice and economic freedom or a critique of the betrayed promises and the land-grabbing by the post-independence political elite. The issue is not that these things are untrue���although from a historical perspective, some of them are inaccurate���but that they are presented as complete truths. While it is true, for example, that Jomo Kenyatta was tried and imprisoned along with five other nationalist activists at Kapenguria for being a Mau Mau ringleader, historians now agree that Kenyatta���s conviction was based on trumped up charges that did not align with Kenyatta���s ambivalent relationship to the militant guerrilla movement.

Kenyatta was an African nationalist, but he was not a Mau Mau leader. Outside of the national curriculum, selective amnesia could most clearly be observed on national holidays, particularly Independence Day and Kenyatta Day. On such occasions, speeches glossed over the painful past, and focused on the economic development of the future. President Kenyatta and his successor Daniel Arap Moi seldom spoke explicitly about the history of the Mau Mau movement, instead alluding to the vague need to ���commemorate Mzee Kenyatta and the blood that was spilled in our struggle for independence.��� The careful ambiguity about whose blood that was, and why it might need to be commemorated speaks to the fact that Kenya���s Mau Mau past remained politically dangerous. Veterans could be used to mobilize voters in specific regions of the country, but would otherwise remain nameless, and, more importantly, silent.

My research as a historian has focused on what happened to the memories of Mau Mau in the face of this public silencing, and seeks to understand what grassroots memorialisation looks like in the face of political amnesia. Working with oral histories from veterans and their families, alongside archival material, I have been consistently struck by the plurality of experience that characterizes the Mau Mau war. There is no one definitive historical truth, and a key part of the mishandling of Mau Mau histories in the decades since independence has been rooted in the ill-fated attempts to discipline the complicated and fragmentary history into something that might fit neatly into tales of heroes and villains.

Through my research, I have found that a rich material culture of Mau Mau has existed in rural communities since the end of the war, one that was astutely aware of the history-making endeavours, but did not adhere to them. While the archival material on Mau Mau was systematically destroyed at the national level, it was carefully preserved by thousands of individuals across Kenya, for whom forgetting the war was never an option. Veterans pulled out boxes of photographs and documents, personal archives carefully preserved far from the censorial eyes of public history-making. Many pulled up their sleeves or skirts to reveal scars, offering their very bodies up as living monuments to the war. Away from the ceremonial lip service of national holidays and hero-worship of the official narratives, these veterans found ways of memorialising Mau Mau on their own terms.

For many years, Mau Mau history was marked more by what is not said in public than by what is said. It has, for successive generations of Kenyans, been characterized by profound silences: family members who never came home, land that was lost, unmarked graves, and gaps in family trees. However, this should not be confused with forgetting. In fact, the silences around Mau Mau and who was permitted to speak of it have often served to amplify the unhealed traumas of the past, which sit just below the surface of everyday life.

In 2003, President Kibaki���s un-banning of Mau Mau allowed veterans to organize publicly for the first time, and saw the beginning of attempts to memorialize the conflict and to portray Mau Mau fighters in a positive light, as heroes of independence. However, there is still no national museum dedicated to histories of the struggle, and national institutions remain reluctant to address the complexity and unhealed traumas of Kenya���s Mau Mau past. This period in the early 2000s coincided with the emergence of a new generation of urban youth, enlivened by stories of the ferocious fighters and their brave struggle for land and freedom, who created their own myths and memorial cultures of Mau Mau.

In Nairobi today, Mau Mau sightings are a frequent occurrence. Yes, there are a few national monuments, and a small display at the National Museum of Kenya, but, more importantly, Mau Mau appears in more quotidian forms. Dedan Kimathi sits astride a matatu, weaving through traffic, sandwiched between Tupac Shakur and Bob Marley. The words ���Mau Mau��� are spray-painted on walls and on the mud flaps of trucks. Young men wear dreadlocked hair and t-shirts with Kimathi���s face.

These representations of Mau Mau history have a lot to say about how memories of the war have come to take on new meanings for Kenyan futures. Mau Mau in general, and Kimathi in particular, have entered into an iconography of revolutionary history that holds a strong sense of continuity for young urban Kenyans today. After all, the grievances of this generation are disturbingly similar to those of the generation of the 1940s who took up arms in the Mau Mau movement. For both, it is about land and freedom. The slum demolitions and police brutality that animates young people in Nairobi and Mombasa and Kisumu have their roots in a not-so-distant colonial and post-colonial past. Increasingly expensive and precarious living situations, lack of economic opportunities, and a government more interested in accruing wealth and resources for a small elite than in ensuring the welfare of all citizens led to the Mau Mau war, and this struggle continues.

In this sense, contemporary popular representations of Mau Mau speak to the fact that Mau Mau cannot be neatly placed in the box marked ���distant past��� only to be opened under governmental supervision on Mashujaa Day, when veterans are wheeled out to recite carefully crafted histories of heroes and heroines. Mau Mau is still a living present. Despite their best attempts to bury the bodies, they lie in very shallow graves.

The lack of public history has led to a grassroots memorial practice that is as imaginative as it is true. The material cultures they have created around Mau Mau speak to an active attempt to reclaim histories of the struggle. What archival material has been revealed and declassified in the UK and in Kenya is coloured by the colonial gaze, so that there are still questions of authorship that remain to be answered by national historical institutions. What does addressing these archival inequities mean? Ignored by institutionalized history-making and, at times, actively silenced, new generations have continued the veterans��� practice of personal histories, crafting their own living monuments to the war. The model of a museum is unsuited to such histories, which are marked by their strong emotional truth more than their historical accuracy, and which need to live defiantly within communities, not cloistered behind the guarded gates of national museums.

This rejection of the conventions of public history, often characterized by material cultures produced by the elite, has liberated Kenyans to imagine their pasts, and, in turn, their futures. Following in the tradition of writers and artists of the 1970s and 80s, who often paid dearly for their representations, Kenyans use fashion and hip hop and graffiti to write into the decimated historical archive, harnessing their imaginative power to unravel the silences and reawaken a revolutionary sentiment.

National history projects like clear lines and straight narratives of heroes and heroines, but Mau Mau cannot and will not fit into such simple constraints. Mau Mau historical plurality reminds us that there is an urgent need to redress the injustices of the past, not by presenting a simple counter-narrative to the official sanctioned myths surrounding the war, but through embracing the plurality of experiences around Mau Mau pasts, presents and futures. These histories were never forgotten. They were deliberately obscured, but have lived active lives throughout the years of political forgetting. They are infused into our national consciousness, into our knowledge of who we are and were and might be.

December 8, 2021

The earth below the surface

Still from We Are Zama Zama.

Still from We Are Zama Zama. Johannesburg is a sprawling, arid city in the heart of South Africa. The terrestrial high points that outline the city center, jut out of the land and resemble mountains. On one of my first visits to Johannesburg, I vocally admired the ���high mounts��� protruding out from the vast flat topography of the city. In response, a friend gently told me, ���those are not mountains;��� they are mine dumps.

The sheer size of these tall, expansive ridges struck me. In South Africa, much of the country’s legacy wrestled with the earth below the surface. The descent underground for lucrative minerals like gold and diamonds created wealth and deprivation. The rural-to-urban movement of migrant labor, either from the countryside towns of South Africa or neighboring countries, supplied the country���s segregated economic, political and social structure with human capital. The fortunes extracted from land and labor became the economic engine of South Africa and maintained its social arrangements.

Still from We Are Zama Zama.

Still from We Are Zama Zama.In We are Zama, Zama, the filmmaker Rosalind Morris offers a snapshot of the lives of three undocumented Zimbabwean migrants, Bheki, Pro, and Jahman. These men participate in work known as Zama, Zama. The term loosely translates to ���someone, who illegally searches disused mines for valuable minerals and metals.��� And in Zulu, it can refer to someone who ���tries and tries again.��� Set in Johannesburg, the film begins in the dark. You follow a group of men with headlamps, crawling and descending into makeshift shafts while dodging falling debris. One miner describes the job as akin to gambling. Throughout the film, miners risk death on unstable rocks, inhale polluted underground air, or face head-on the peril of losing their way. In unison, huddled they pray ���without your guidance, we will be lost.��� The risk/reward of finding gold surpasses the reality of hungry bellies or rent for a shack in the informal settlements where these men live.

Rosalind Morris, an anthropologist, and scholar drew on her ethnographic fieldwork to inform the film���s portrayal of ���afterlives��� or the ���social worlds��� of mines exhausted from mineral viability. Conceptually, the term ���afterlives��� also refers to the livelihoods of these miners and the worlds they have created. As much as the film focuses on migrants who mine illegally for gold, it is a social commentary on the failures of post-colonial liberal democracies in Southern Africa���from smugglers courting migrants from Zimbabwe, to a never-ending search for employment in post-apartheid South Africa.

Still from We Are Zama Zama.

Still from We Are Zama Zama.At its best, the film powerfully offers a glimpse into the everyday lives of these miners. With cameras strapped to the headlamps of the miners, we see them eat, sleep, and crawl through the mines in anticipation of a shaft���s possible collapse. Using mallets, pickaxes, and occasionally dynamite, these men risk death. The extraordinary footage draws in the viewer. As the camera follows the miners, deep into the mines, with emptied bags of millet strapped to their backs, pickaxes, hammers, and short sticks of dynamite, you sense both the resolve and terror these men experience. After days underground the miners ascend from below the surface and the formation of the mineral into gold begins. Footage of women pounding dirt and processing minerals reminds the viewer of the human toil of processing gold without equipment. These are the social worlds.

Unfortunately, the film elides a longer history of insurgent politics by organized miners and the swift, often deadly repercussions those labor activists faced during apartheid as well as in the post-apartheid era. These men live beyond absolute suffering and everyday coping strategies. On a lighter side, a scene of a miner and his wife dancing to Steve Winwood���s ���Higher Love��� on a red wind-up radio, or the group of miners joking and laughing over a game of pool, offer dimension to the film.

Still from We Are Zama Zama.

Still from We Are Zama Zama.The power of We are Zama Zama is the way it captures a slice of a long history of trying to exploit what lies beneath the earth���s surface. Those who descend into the darkness cross the line between survival and discovery. The underground is a place of intrigue and also something to be conquered. We witness how material conditions heavily outweigh the gamble of injury or death. When one miner cuts his hand on a jagged piece of rock, he says, ���Where there is gold, always blood is there.���

December 7, 2021

Disappearing from view

Returning to Lilongwe along Route S122. Image credit Lars Plougmann via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Returning to Lilongwe along Route S122. Image credit Lars Plougmann via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. One day, when I was 13 years old, I had a visit planned with a friend in my neighborhood in Lilongwe, the capital city of Malawi. They lived about a 10-minute walk away from my family���s house. My parents almost always drove my siblings and I between our homes and our friends��� homes back then, no matter how close or far, but they must have been out that afternoon, and my friend and I had already made our plans.

I believed���with good reason���that I needed to ensure as best as I could that I wouldn���t be a target on that short walk. I���d had to quit one of my extracurricular activities the year prior, after being harassed by one of the male grounds staff at the activity site. I had been 12 at the time, so I knew that my age wouldn���t be a deterrent. Before leaving my house that afternoon, I dressed as androgynously as I could: baggy jeans, baggy shirt, big jacket even though it was midday in summer, a baseball cap���facing forward so as to hide my face���and high-top basketball sneakers. To onlookers along my route I must have looked ridiculous, but it was what I thought I had to do to keep myself protected against sexualized attention.

Last October, an��11-year-old girl��doing the same thing as I was that day���walking from her home to the home of someone she knew, in her case an aunt���was raped en route to her aunt���s home by a man who pretended to merely be offering her a ride on his bicycle. Since then, the case has become the central narrative of Malawi���s #MeToo moment, the latest in our ongoing fight against gender-based violence. She is far from the only girl child whose victimization has made public headlines, though: the month before, the mother of a 14-year-old girl who had been sent to live with one of her uncles filed a police report alleging that the girl had been the victim of repeated rape at the hands of her uncle over the course of several months. Last November, another girl, this one 12 years old, was raped by an employee at her grandmother���s home.

Almost a quarter century on, the fears I had held at 13���fears that I would become the victim of sexual violence, even at my young age���stand, brutally, just as correct.

The legal term used in Malawi for the rape of an underage female is ���defilement.��� It is a legacy of Malawi���s colonial era, when the law specifically designated girls under the age of 13���now 16���not as people in their own right, with sexualities of their own, but rather as the property of their families. (There is no term for the sexual violation of boys under any age; it doesn���t exist in the current legal code, a separate problem entirely.) The legal nomenclature of defilement���rather than statutory rape���is critical to understanding the ongoing problem of the rape of underage girls in Malawi and the relatively lax sentences handed down to offenders, should cases even make it successfully through the court system.

When a girl is conceived of as an object���as the property of the men who effectively own her rather than as a person in her own right���then the sexual violation of that girl is, at most, the sullying of property, not violence against a person and their fundamental human rights. Though I would not have had the words for it back then, my 13-year-old self understood that had I ended up a victim���in other words, had my harassment experience as a 12-year-old been transposed to a more extreme point on the same continuum of sexualized violence���I would have been held at least somewhat responsible for not protecting the virtue of the property that was my body, and so would my parents.

According to a 2020 national report, ���Situational Analysis on the Increase of Sexual Violence in Malawi,��� there was an 11% increase in reported cases of the violation of underage girls between 2018 and 2019, and a 19% increase between 2019 and 2020. While there is debate as to whether or not cases have truly risen or whether it is merely the reporting of the crime that is on the rise, the fact is that the endemic sexual violation of underage girls remains a dark stain on Malawian society���a society that otherwise purports to hold deeply conservative and religiously informed values around sexual piety for both men and women and to value the role of women in families and communities.

Even to report these crimes is often to subject not only the victim but her family to revictimization by way of Malawi���s broken criminal justice system. Laws do exist to penalize the people who commit these acts against girls, but the road to getting there is riddled with obstacles. These range from the money required to even engage legal counsel, to the myriad paperwork and reporting requirements of pursuing a case, to the sheer time involved that can take away from working family members��� paid employs, not to mention the numerous corrupt actors within the system who flat out will not do their jobs unless covertly provided with additional financial incentives beyond their standard paychecks. Many endeavors to obtain justice, then, are preemptively arrested by the structural violence of the criminal justice system itself.

The consequences of living inside this cauldron of violence against girls���and specifically girls who are not conceived of as people but as instruments subject to the wills of the men in their environs���cannot be overstated enough. Though the lasting effects of sexual trauma are well documented, there is the much larger question of all the ways in which girls slowly disappear from societal view as a result of the violence they experience, as well as the ways in which they are considered dirtied after the fact, rather than faultless victims deserving of justice, restitution, and, in a perfect national context, societally supported healing. Instead, young victims of sexual violence are frequently silenced, whether through active instructions not to speak of the atrocities to which they were subjected, or worse, by being married off to their abusers in a contrived attempt to protect the girl���s worth and erase the stain of her so-called defilement from the object that is her body.

Over my adolescence and teenage years, I left three after-school activities as a direct result of the sexualized attentions of men involved with those activities. In each moment, I saw these decisions as necessary, made each one alone, and do not recall having feelings about each instance of deciding to quit other than, ���well, that���s that then.��� But I am a woman from a family of privilege, and those decisions ultimately did not, in any significant way at least, arrest my progress toward the life I eventually made for myself. They shook my sense of safety in my world, though, and made me hypervigilant about what things I could do���whether after-school activities to enroll in or classes to sign up for. For each activity, I considered whether I stood even a slight chance of ending up a victim, and then, based on that calculation, decided not to undertake those things. That vigilance was its own form of disappearing from the world, insofar as it caused a notable retreat from wholehearted engagement with my surroundings and opportunities.

For so many girls in Malawi, though, their disappearance from society is magnitudes worse: it ends up becoming a total derailing from their lives��� original tracks. Girls regularly have to leave school after becoming impregnated by a schoolteacher, for example, or after being married off in their teen years in an attempt to alleviate their family���s poverty. The lost potential of so many girls is immeasurable, not just in their own lives but on the larger scale of the very shape of society. That we are effectively okay, as Malawians, with this state of affairs���insofar as this problem continues to insistently remain one���is frustrating, even painful, for myself as a woman now watching the next generation of girls growing up in our country. As I do so, I wonder how long they will be able to keep their beliefs in the great potentials of their lives before the inevitable point, still in their girlhoods, when a man they trust first strips that away from them.

When I was 14, a few months after I got my first period, my grandmother told me I could no longer ���be playing with boys.��� This was her euphemism for the necessity���now that I could get pregnant���of me taking defensive measures against potentially finding myself in trouble at the hands of a boy or man with dishonorable intentions. Her advice underscored the notion of making proper choices with respect to the company of men. Yet that talk would not have saved the 11-year-old rape victim in Chikwawa nor the 12-year-old rape victim in Nkhotakhota; in fact, it was given over a year after the day I donned all those absurd layers of clothing just to walk 10 minutes to my friend���s home. To presume choice as a factor in a girl���s victimization is to grotesquely place the burden of their protection on girls alone.

The persistent scourge of young girls��� sexual victimization cannot merely be seen as solvable through her own or her family���s powers of defense against her so-called defilement and subsequent devaluation. Our entire society must see this protection as important, and this importance must be baked into the institutions that keep our society standing���from healthcare, to education, to justice. Precious little will change otherwise���not until a critical mass of people stop colluding in conceiving of this violence as acceptable.

December 6, 2021

Mo Ibrahim does not have all the answers

Mo Ibrahim listens to a delegate at his foundation's "African Youth: Fulfilling the Potential," in Dakar, Senegal in November 2012. Image via the Mo Ibrahim Foundation on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

Mo Ibrahim listens to a delegate at his foundation's "African Youth: Fulfilling the Potential," in Dakar, Senegal in November 2012. Image via the Mo Ibrahim Foundation on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. Launched in 2006, the Mo Ibrahim Prize aims to “celebrate” former African heads of state who have shown “excellence” in leadership and worked to “strengthen democracy.” It has, however, only been awarded seven times in its sixteen year history, and one can question whether this “bribing” of African leaders is working since democracy on the continent is in decline. This series of republications from The Elephant is curated by one of our editorial board members, Wangui Kimari.

Few have done more to entrench democracy in Africa than Mohamed Ibrahim through his Mo Ibrahim Foundation established in 2006. The foundation���s signature effort is the Ibrahim Prize. Three years after leaving office, an ���exceptional role model��� former head of state or government is awarded US$5million over a period of ten years, and an additional US$200,000 every year for life. Despite such a generous offer���over three times the Nobel Peace Prize���the Mo Ibrahim Prize has been awarded in only seven of the 15 years of its existence. The late Nelson Mandela was an honorary laureate in 2007. No worthy candidate has been found in the years since.

Design flaws and the changing global dynamics doomed the Ibrahim Prize. While the prize is the most generous of any awards out there in monetary terms, it was never close to what African leaders can ���make��� while in power. The presidency offers more than just direct financial rewards; there are indirect gains too that cannot be satisfied by monetary compensation. ���Bribing��� African leaders to be models of good governance misses the point that there is no ceiling for greed, and greed is insatiable.

One year after the Mo Ibrahim Foundation award was launched, the United States launched AFRICOM (United States Africa Command), and a year later, the global financial crisis hit. Combined, these factors stymied democratization in Africa.

While, of course, Africa���s democracy cannot be predicated on a single prize, there has been no discernible improvement since the award was launched and it is fair to question whether the award is even necessary. For, despite the award, Africa���s democracy has been in far worse shape since it was launched.

Democratic boom and slideThe late 1980s and 1990s was a period of immense optimism across Africa. The Berlin Wall came down, the Cold War came to an end, and Nelson Mandela was released from prison, going on to lead South Africa into the first multi-racial election. These events collectively engendered a sense of buoyancy across Africa, and others started looking at Africa through rose-tinted glasses.

After a slow start, electoral democracy began taking root in Africa. According to Freedom House, during this buoyant period Africa went from having two-thirds of its countries classified as ���Not Free,��� with only two countries���Botswana and Mauritius���classified as ���Free��� in 1989, to two-thirds of all African nations being classified as either ���Free��� or ���Partly Free��� by 2009.

Many civilian and military dictatorships were swept away, paving the way for the establishment of rule-of-law-based governance systems characterized by constitutionalism and constitutional government, including reforms such as the imposition of term limits.

That decade also saw the coming into power of former rebel leaders in Uganda, Ethiopia, and Eritrea���Yoweri Museveni, Meles Zenawi and Isaias Afwerki. This cohort was uncritically embraced and christened the ���new breed��� of African leaders. Decades later, with the exception of Meles who has died, the rest have their countries in a firm grip.

In 2021, Freedom House rated only eight countries in sub-Saharan Africa as free. Half of these are small island states���Cape Verde, Mauritius, Sao Tome and Principe, and Seychelles. The number of African countries that Freedom House rated ���Not Free��� has grown from a low of 14 in 2006 to 20 in 2021.

Presidential term limitBecause of Africa���s post-independence history, most constitutions included a presidential term limit to safeguard against presidential overreach in the absence of a strong legislature, judiciary, and civil service. Of almost 50 constitutions passed during Africa���s wave of democratization, more than 30 had a presidential term limit. Some even included age limits beyond which a president cannot stand for election or serve.

But this attempt at full-proofing against presidential overreach has come under assault, with presidents attempting to extend their terms by fiddling with the constitution. Between April 2000 and July 2018, presidential term limits were changed 47 times in 28 countries, with at least six failed�� attempts to change the law: Frederick Chiluba of Zambia in 2001, Edgar Lungu of Zambia and Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria in 2005, Mamadou Tandja of Niger in 2009-2010, and Blaise Compaor�� of Burkina Faso in 2014. All failed in their attempts.

Leaders extend their terms using various means. Some increase their terms from five to seven years, as was the case in Guinea (2001), the Democratic Republic of Congo (2002), Rwanda (2003) and Burundi (2018). In Chad (2018), the term was increased from five to six years while South Sudan (2015 and 2018) and DRC (2016) used the conflict in their countries to postpone elections thus prolonging their presidents��� stay in power.

In the case of Zimbabwe (2013), the Democratic Republic of Congo (2015), and Rwanda (2015), terms of office were reset through constitutional amendments once the president reached the term limit.

In other countries, the incumbent removed the term limit altogether, as in the case of Guinea (2001), Togo (2002), Tunisia (2002), Gabon (2003), Chad (2005), Uganda (2005), Algeria (2008), Cameroon (2008), Niger (2009) and Djibouti (2010). The lack of effective term limits means that Africa has ten leaders who have ruled for over 20 years and two family dynasties that have been in power for more than 50 years.

The propensity of leaders to extend their terms is in complete dissonance with the disproportionate number of citizens opposed to it. According to a 2015 Afrobarometer survey, about 75 per cent of citizens in 34 African countries favor limiting presidential mandates to two terms. Moreover, democracy is the preferred form of governance for 67 per cent of Africans.

Extending presidential term limits is associated with adverse social-economic outcomes. All eight African countries facing civil conflict (excluding insurgencies by militant Islamist groups) are without term limits. Of the 10 African countries that account for the largest number of Africa���s 32 million refugees and internally displaced populations, seven countries do not have term limits.

The War on TerrorThe 9/11 terror attacks and the 2008 financial crisis combined saw Western countries pivot away from promoting democracy in Africa.

The continent became the next frontier of the war on terrorism after Osama bin Laden was forced out of Saudi Arabia and settled in Sudan in the 1990s. This sufficiently alarmed the US, which then made security the dominant lens through it���and the rest of the West���viewed Africa and became the basis for policy formulation and engagement with the continent. Inevitably, the promotion of democracy was deprioritized with the attendant decline in spending and other resources.

In the same manner how Africa���s former Big Men had positioned themselves as the vanguard against the spread of communism in Africa, a new crop of leaders instrumentalized the War on Terror and fashioned themselves as the last defense against terrorism. This opened the taps of Western largess, training and political support and protected them from being held accountable. On the domestic front, these leaders passed some of the harshest anti-terror laws in line with President Bush���s neat Manichean dichotomy���you are either with the terrorists or with us.

The anti-terrorism laws became a blunt instrument with which to beat any organized opposition by reflexively declaring it terrorism, which inevitably meant using extra-legal means, including holding opponents in safe houses, and using torture, forceful disappearances and extrajudicial killings. All these eroded the burgeoning democracy.

The reflexive reaction to the events of 9/11 spawned an interlocking web of covert and overt military and non-military operations in Africa. Initially deemed necessary and temporary, these efforts have since morphed into a self-sustaining system complete with agencies, institutions, and a specialized vocabulary that pervades every realm of America���s engagement with Africa. AFRICOM has become the primary vehicle of America���s engagement with the continent.

No president has exploited the War on Terror to their advantage more than the late Idris D��by of Chad and Yoweri Museveni of Uganda. Museveni used the War on Terror to turn Uganda into the anchor state in East Africa and the Great Lakes region, as he became repressive domestically. Debby made Chad the gateway to the Sahel region. In the political arena, Museveni pronounced Kizza Besigye and Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu���known by his stage name Bobi Wine���terrorists and visited terror upon them and their supporters.

The Mo Ibrahim Foundation Award was first awarded in 2006; in 2007 AFRICOM was formed, in 2008, the global financial crisis hit. Privileging counterterrorism in engagement with Africa securitized everything, and the financial crisis limited the West���s ability to continue funding democracy. In their place stepped African leaders who put themselves at the service of assuaging the West���s security anxieties and thus severely damaged the nascent democracy. Unsurprisingly some of the Western-trained military leaders are now emboldened to overthrow elected leaders and replace them with military governments.

Sudan���s revolution and counterrevolution

Image credit Jeanne Menjoulet via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Image credit Jeanne Menjoulet via Flickr CC BY 2.0. Since the signing of the 2019 power-sharing agreement between the Sudanese military and the civilian pro-democracy coalition, the Forces for the Declaration of Freedom and Change, there has been a consistent level of tension and conflict between the demands of the resistance on the one hand and the policies and decisions of the ���power-sharing��� government on the other. The resistance���organized in neighborhood resistance committees initially charged with field operations like organizing protests, building barricades, and distributing pamphlets���has since evolved to become the political voice of the streets over the past two years. In fact, the resistance committees��� work has led to several conflicts and protests against government policies, from the delay of investigations and trials for the victims of the June 2019 massacre, to economic liberalization policies. These protests always began with polite, reassuring support for the government, followed by the mention of protesters��� demands���a strategy�� caused by the messaging of the government and the ruling block, which repeatedly asserted that any objection to the government would lead to handing power back to the military.

In the weeks leading up to the coup, tensions rose between the military and the civilian coalition in government. Military leaders gave speeches about the failure of the civilian government, citing the negative impacts of economic liberalization measures, which have led to increases of over 150% in costs of living in the last year alone. (It is worth noting that the head of the coup, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, would endorse the same policies in his first press conference the day after the coup.) Amid these tensions, resistance committees, labor unions, and other groups started preparing for the coup, with some unions issuing proactive strike announcements effective the moment a coup should occur. Resistance committees called for and successfully organized the October 21st Millions March, uniting under the slogan, ���Down with the partnership of blood.��� It was clear to them by then that power cannot be shared and that a partnership with the military is a partnership with criminals and, as such, a compromise on justice.

On the morning of October 25th, Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, woke up to clear signs of a coup: the scrambling of radio stations, an internet shutdown, more army vehicles in the streets than usual, and rumors that the prime minister and his cabinet had been detained. That same day, people occupied the streets and built barricades as early as 6 a.m., strike calls were activated, and the country was shut down. By the end of the day, four martyrs had been killed at the hands of the military coup. The coup would harden the position of the public and the resistance committees against the military, giving rise to the call for a total removal of the military from politics. This call, which had been widely seen as radical and idealistic until a few days before the coup, is now the mainstream position of the Sudanese people.

Resistance committees are currently leading the movement on the ground in Sudan. They are organizing protests, enabling civil disobedience inside neighborhoods by providing basic goods and services to their populations, and in some areas even working on electing and appointing local governments. The committees are also collaborating to produce joint sets of demands. This exercise has paved the path for revolutionary discussions that imagine different forms of governance and constitution making while also reviewing those scenarios, demands, and imaginations more critically. The committees are engaged in intellectual work as much as they are in protesting and building barricades.

Nevertheless, you can watch news about Sudan on regional and international networks for days without hearing a word about resistance committees. The media is both unable and unwilling to understand and reflect their real role. But the committees and their organizing is what stopped the coup from being successful, and they are the main tool that we as Sudanese people would like to share with revolutionaries around the world.

Sudan���s resistance committees are united against the coup, with a clear position���known as the ���Three No���s������against the military: ���No negotiations, no partnership, no legitimacy.��� The main obstacles to the fulfillment of these slogans are international mediators and others working to restore the pre-coup power-sharing situation. Major parties involved in or promoting mediation efforts include the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Sudan, as well as the US Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa, who has called the demand of removing the military from politics an unrealistic one. The US envoy has also described the military���s violent reaction as ���exercising restraint,��� despite the killing of tens of protesters. A number of Sudanese businessmen and regional players have also been involved in promoting mediation and a new compromise.

But these efforts have been publicly rejected by the resistance committees, and as a result, attempts have been made to control and co-opt their revolutionary work. This includes a recent invitation from the prime minister in detention (since released) to resistance committees to visit him for an ���update on the status quo.��� The committees publicly rejected the invitation, instead offering to arrange public meetings for the prime minister in which he would address his people in the streets. Moreover, they announced that they are not interested in such negotiation and mediation efforts. This rejection of closed-room politics is brand new to Sudan���as are many of the actions and decisions of resistance committees.

Under these circumstances, it must be highlighted that the best support that the Sudanese revolution can get from international revolutionary allies is for them to reject and fight their own governments��� efforts to force a government of killers on Sudan for the second time. Ask where and what your government is spending money on in Sudan, and call out any efforts toward another ���compromise��� and any other attempts to legitimize military rule.

December 3, 2021

A new star in the southern sky

Malcolm Jiyane Xorile. Image by Tseliso Monaheng.

Malcolm Jiyane Xorile. Image by Tseliso Monaheng. Genius and perfection are not synonymous. In fact, the two can be quite at odds. The pursuit of perfection cannot be but single-minded. It is a monolithic, and sometimes even destructive impulse. Conversely, truly virtuosic artistic endeavor does not proceed by diktat. It is heterodox. It is an act of creation. With the album UMDALI (meaning: creator), Malcolm Jiyane’s debut as a bandleader, the South African creative polymath has showcased the full bloom of his enigmatic genius. On the album, he conducts his band, the Malcolm Jiyane Tree-O, to empyrean musical alchemy with a perfectly imperfect slice of liminal South African jazz.

The backstory of the album’s creation offers up the small quotidian miracles that make up the stuff of life while everyone waits on spectacle. At the end of 2020, with Jiyane ground down by lockdown and inaction, the label Mushroom Hour Half Hour offered him the chance to record an album (Mushroom Hour had also been behind the October 2020 release of the soundtrack to Sifiso Khanyile���s documentary UPRIZE! a project which Jiyane had participated in as part of Spaza). But, before Tree-O had assembled for a second recording session in 2021, sound engineer Peter Auret discovered another album the band had recorded and shelved in 2018. The team then decided that this first album���s time had come, and so that is what has now been released.

Malcolm Jiyane Xorile. Image by Tseliso Monaheng.

Malcolm Jiyane Xorile. Image by Tseliso Monaheng.But great stories have deep roots, and this album is the culmination of a journey that began decades ago. Jiyane grew up in a place called Kid���s Haven, which is a shelter for vulnerable children in Benoni. One day, as the story goes, the legendary educator and musician Dr. Johnny Mekoa brought his big band to play for the children. Jiyane heard their rendition of “Bags��� Groove” and that was that. He joined Mekoa���s Music Academy of Gauteng as a drummer at the age of 13, and as an adult became one of the most hardworking and generous jazzmen on the Joburg scene. A multi-instrumentalist and multi-disciplinary creative, he was a fixture at Steve Kwena Mokwena���s venue, Afrikan Freedom Station.

UMDALI itself was workshopped and recorded over two days in 2018 (and was mixed and mastered over three weeks, three years later). Mokwena was instrumental to the process, and explains in the album���s liner notes that it is an ���honest snapshot��� of Jiyane���s circumstances while it was recorded: Jiyane had been grappling with the deaths of his mentor Mekoa and bandmate Senzo Nxumalo, and the birth of his daughter���whose image graces the album cover with a tender dignity. ���These life-altering events give shape to the music���s emotional register and its thematic concerns,��� Mokwena writes.

It is thus that the opening stanza of “Senzo seNkosi,” the first track on the album and one dedicated to Nxumalo, sets the tone with an elegiac flourish, a requiem in woodwind and brass. “Umkhumbi kaMa” lets the percussion rise to the fore, raising the tempo and adding a searching, restless energy. It is a song that shows why jazz and funk play well with others, but hold a sibling closeness to each other.

“Ntate Gwangwa���s Stroll” is a slow-burning blues tribute to Jonas Gwangwa, the late trombonist who was an artistic embodiment of South Africa���s struggle for freedom and cultural expression under apartheid, and another of Jiyane���s mentors. On it, horn contemplations ooze over pensively paced percussion, spreading like raw honey over steaming uJeqe.

UMDALI album cover.

UMDALI album cover.���When I started playing trombone,��� Jiyane explains, ���the players I studied and listened to weren���t South African: JJ Johnson, Curtis Fuller, Albert Mengelsdorf, et al. I then started researching South African trombone players, and what I found in Mosa Jonas Gwangwa���s body of work blew me away. What Ntate Jonas did as a composer, arranger, producer and freedom fighter is very close to my heart. We share the same bone.���

“Life Esidimeni” tells the story of the unfathomable tragedy of the deaths of 143 people, from starvation and neglect, in South Africa���s state-run psychiatric facilities. The refrain “lendaba ibuhlungu” (this story is painful) rings through a song which expresses solidarity with those society has forgotten, and rises toward a crescendoing ending that performs a catharsis so exultant as to appear almost miraculous, carrying all with it���grief, pain, love, beauty���in a great, humanizing flood.

The album closes with “Moshe,” a song so beautiful that it escapes whatever words I may be able to hold up to it. Suffice to say, the track���s vocals open up unexpected vistas, speaking in tones that offer a direct line to the universality at the core of all music. Phrases that have previously been gestured toward find their full expression here, and the call and response between the various instruments catalyses something elemental, like wind speaking to fire, like water writing poems for the earth.

And through it all���five songs in just under 45 minutes���the album is punctuated by fingers scratching on bass strings, the breath of life issuing through wind instruments, and Jiyane���s own spontaneous exclamations and encouragements. It all brings to mind the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, a worldview centered on the beauty and acceptance of transience and imperfection. Brought fully to life by its tiny, organic imperfections, UMDALI is as unlikely and miraculous as a Barberton daisy blooming through a cracked Benoni sidewalk.

This is both a jazz album, and an overheard conversation between artists, a musical dialogic. UMDALI is the soundtrack to mentorship, comradeship and connection. It slips the restricting binds of genre and expectation, and shows that the greatest gift the elders offer is not didactic or dogmatic, but emancipatory in nature. It shows us that talent���and genius���will out. There is a new star in the southern sky.

December 1, 2021

What’s happening in South Africa?

Photo by Pawel Janiak on Unsplash

Photo by Pawel Janiak on Unsplash The arrest in July of former president Jacob Zuma in connection with an investigation into widespread corruption sparked an eruption of unrest and violence, mainly in the province of his base, KwaZulu-Natal. Yet the upheaval reflects a broader crisis underpinned by the failures of the African National Congress (ANC) to deliver on the hopes of national liberation, and the neo-liberalization and contradictions of the ANC in power. Soaring levels of unemployment and inequality have been exacerbated by the pandemic and government austerity policies, and in November, municipal election results (where the ANC and official opposition Democratic Alliance under-performed) confirmed widespread discontent.

In this conversation hosted by Africa Is a Country, Haymarket Books, Internationalism From Below, and Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE), AIAC founder and editor Sean Jacobs and staff writer William Shoki spoke to Lee Wengraf (contributing editor at ROAPE) about the roots of South Africa���s political crisis.

Listen to the show below, and subscribe via your favorite platform.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/c05d41a8-3122-4fda-bea4-03674ccd56da/aiac-talk-what-is-happening-in-south-africa.mp3November 30, 2021

Music makes the past alive

Fendika. Image credit Ninara on Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Fendika. Image credit Ninara on Flickr CC BY 2.0. Moving on from ���clubbing across the continent,��� Africa Is a Country Radio is back on Worldwide FM with a new season. This time, each show will be inspired by a different work of African literature. In the first episode, we visit Ethiopia with Kenyan-American author Mukoma Wa Ngugi, who has just released a new novel called Unbury Our Dead with Song on Cassava Republic Press. In his latest work, Mukoma uses the Tizita, and its birthplace of Ethiopia, as an entry way to ruminate on the intricacies of love, war, life and death, the past, the future, faith and human expression. The Tizita, according to the book���s main character, John Manfredi, is:

��� not just a popular traditional Ethiopian song; it was a song that was life itself. It had been sung for generations, through wars, marriages, deaths, divorces and childbirths. For musicians and listeners exiled in Kenya, the US and Europe, or trying to claim a home in Israel as Ethiopian Jews, the Tizita was like a national anthem to the soul, for better and worse.

Released in the shadow of Ethiopia���s latest conflict, the book is eerily relevant to the current moment. In this show, we will play some music inspired by different moments and characters in the book, and talk with Mukoma about his work.

Listen below or on Worldwide FM.

Music keeps the past alive

Fendika. Image credit Ninara on Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Fendika. Image credit Ninara on Flickr CC BY 2.0. Moving on from ���clubbing across the continent,��� Africa Is a Country Radio is back on Worldwide FM with a new season. This time, each show will be inspired by a different work of African literature. In the first episode, we visit Ethiopia with Kenyan-American author Mukoma Wa Ngugi, who is set to release a new novel called Unbury Our Dead with Song soon on Cassava Republic press. In his latest work, Mukoma uses the Tizita, and its birthplace of Ethiopia, as an entry way to ruminate on the intricacies of love, war, life and death,�� the past, the future, faith and human expression. The Tizita, according to the book���s main character, John Manfredi, is:

��� not just a popular traditional Ethiopian song; it was a song that was life itself. It had been sung for generations, through wars, marriages, deaths, divorces and childbirths. For musicians and listeners exiled in Kenya, the US and Europe, or trying to claim a home in Israel as Ethiopian Jews, the Tizita was like a national anthem to the soul, for better and worse.

Released in the shadow of Ethiopia���s latest conflict, the book is eerily relevant to the current moment. In this show, we will play some music inspired by different moments and characters in the book, and talk with Mukoma about his work.

Listen below or on Worldwide FM.

November 29, 2021

South Africa needs power, not apologies

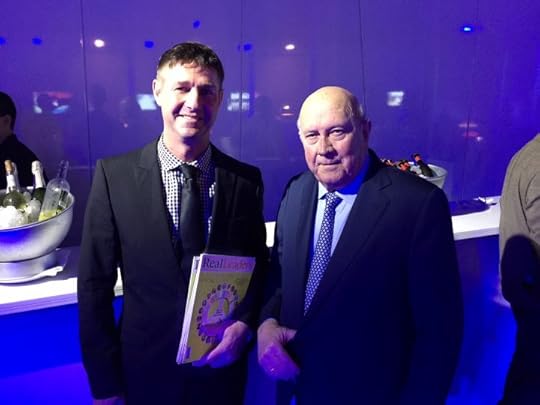

Grant Schreiber with former South African President F.W. de Klerk at the World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates in Barcelona 2015. Image credit George Caulfield via Wikimedia Commons.

Grant Schreiber with former South African President F.W. de Klerk at the World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates in Barcelona 2015. Image credit George Caulfield via Wikimedia Commons. Reading the testimonies recorded by the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, I am always disturbed by the scale and severity of the apartheid regime���s brutality. Established in 1996, the TRC was an ambitious attempt to realize restorative justice. Tens of thousands of victims testified, alongside thousands of perpetrators in order to excavate a common understanding of South Africa���s violent past and move towards healing relations between the wretched of the earth and their former conquerors.

Testimonies told of bodies that were irreparably mutilated from days of torture, thousands of activists abducted never to be seen again, human flesh seared by the hot flash of a discreetly concealed bomb, policeman holding onto the limbs of their victims like trophies won on a safari, and families terrorized by desperation, seeking answers in order to mourn those whose lives were stolen by assassins, askari���s, soldiers, and policemen.

One can���t help but wonder why people were willing and eager to unleash such calculated cruelty upon other human beings? The American writer James Baldwin once wrote that ���power is the arena in which racism is played out��� and he was right. Understanding the use, distribution, and rationalization of power is central to comprehending the project of apartheid. Moreover, realizing the material conditions and historical processes in which power was exercised pulls us into an intimate clarity on why white minority rule collapsed under the indomitable pressures of a changing South Africa.

If we fail to unveil the sources and functions of power we can never mobilize to radically alter its unjust and unsustainable configuration. In the past decade South Africa has been immersed in a series of perpetual crises: ever-widening inequality, nearly half the population locked into poverty, an unemployment��rate of 44% that has left millions hungry and undernourished, and nihilistic despair. Accentuating the country���s gradual decay is its governance by a class of politicians who lack the interest, will, and imaginations to design or effectively implement policy that could ameliorate our myriad socioeconomic issues. In part, it is the subtle camouflaging of power that has pushed the country into an explosively precarious situation. You can���t act against that which you do not see.

F.W. de Klerk, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and apartheid���s last president, died on November 11. The varied reactions to his death, and the contentious debates on his legacy, reveal a society trapped in discourse,�� obsessed with the actions of individuals, and anxious to find answers through the moralizing of political dilemmas. This tendency was amplified by De Klerk himself beyond the grave. The day of his passing, The F.W. de Klerk Foundation released a seven-minute video recorded before his death, in which the former National Party leader clarified his unequivocal condemnation of apartheid and his commitment to the principles of South Africa���s democratic constitution. (In 2012, De Klerk told CNN that apartheid had been beneficial to black South Africans. Last year, February, he told an interviewer on South Africa���s public broadcaster, SABC, he was ���not fully agreeing��� that apartheid was a crime against humanity.)

It was a solemn plea for forgiveness from a man desperate to purify his controversial legacy. De Klerk���s final words also worked to deploy the mystifying abilities of moralism. Since his death, conservative and right-leaning liberal commentators praised De Klerk for being a courageous and pragmatic leader who released Nelson Mandela, alongside unbanning liberation movements such as the African National Congress, which has governed South Africa since 1994. And of course such perspectives grant De Klerk great esteem for his participation in the arduous multi-party negotiations that moved the country towards its first national democratic election. Other commentators even asked that South Africans seriously contemplate forgiving De Klerk in order to liberate themselves from bitterness and resentment.

But we must ask, does forgiveness matter? The stark reality is that the content of De Klerk���s soul or of his moral character were inconsequential to the end of apartheid and the vitality of its phantoms in the present. Indeed, forgiveness can be profoundly therapeutic. It can be a crucial step for victims seeking to overcome trauma and help perpetrators of oppression digest the gravity of their crimes. However, forgiveness does not undo nor produce solutions to the vast destruction caused by unjust systems of power,such as racial capitalism, which have organized South African society for centuries.

Subverting or ignoring critical questions of power with the hammer of moralism is not an exclusively South African phenomenon. Throughout 2020, as Black Lives Matter protests occurred across the US, liberal talking heads called for a ���racial reckoning.��� It was a seemingly earnest call to confront America���s ���original sin of slavery��� and acknowledge not only the sufferring caused by centuries of white supremacy, but also an invitation for white Americans to admit how racism had corroded America���s moral character and their own hearts. In harmony with South African politicians, American liberals and centrists indulge in talking left while walking right. Discussions of a racial reckoning performed acrobatics, yet always dodged dealing with the economic relations and the political order that have sustained racism into the 21st century. As noted by political scientist Toure F. Reed, issues such as healthcare, the criminal justice system, and poverty are likely to be discussed in moralistic language that offers hollow symbolic gestures and moderate reforms, which in turn�� do little or nothing to change the material conditions under which many black Americans live.

In both the rebuke and lionization of De Klerk there is an attempt to squeeze power into the zone of emotional sentiment. Instead of contemplating his relationship to power, we become entangled and disorientated in debates about his bravery or his failure to expand his moral framework and become a symbol of sincere white attempts at reconciliation.

I���m deeply sympathetic to those who wished De Klerk would admit his complicity in apartheid���s horrors as its last dictatorial ruler. His death means some families will never know what happened to their loved ones whose lives were taken by his regime. Appearing before the TRC, De Klerk lied to the nation, claiming he and his government, in dealing with anti-apartheid activities, had never authorized ���assassination, murder, torture, rape, assault or the like.��� Through tireless work the commission produced further evidence of widespread human rights abuses conducted by state security forces (then known as death squads) during his presidency, yet De Klerk remained resolute that he and senior leadership of the National Party were not responsible for the ���criminal actions of a handful of operatives,��� and that such actions were�� ���not authorized and not intended��� by his government.

The move towards representative liberal democracy in South Africa was characterized by mass violence and unstable negotiations. The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), a Zulu nationalist movement and political party led by Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi, orchestrated a crusade of ethnic chauvinism throughout the 1980s and 1990s, resulting in the death of hundreds of citizens in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. The IFP and National Party had a mutual interest in sabotaging the country���s steps towards democracy. Both parties were propelled by narrow nationalism that protected the interests of elites. For the IFP,�� the shift toward a democratic order threatened the power of the Zulu monarchy; and Afrikaner nationalists feared that a democracy governed by the ANC would result in the persecution of white citizens, but more crucially they feared that the Tripartite Alliance would upturn property relations, in which white minority power was embedded.

Eventually it was revealed that the IFP had co-operated with the apartheid���s security forces by receiving on-the-ground assistance, weaponry, and training from apartheid���s military and police in order to carry out massacres. One would be a naive fool to believe that De Klerk, the executive leader of a totalitarian regime, would have had no knowledge of the operations of the state���s security forces.

After a brief term as deputy president to Nelson Mandela, De Klerk retired from politics, establishing the F.W. de Klerk Foundation. Through his foundation and reputation as a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, De Klerk was able to sanitize his reputation. His opinions on contemporary South African politics were valued by international journalists, he was courted as a great statesman and reformer by world leaders, given honorary degrees by esteemed universities and he even spoke before the Oxford Union in 2014. De Klerk also used his platforms to weave audacious apartheid apologetics. In a 2020 interview with the South African Broadcasting Corporation, De Klerk refused to call apartheid a crime against humanity. He argued that it could not be compared in scale to other grand injustices of the 20th century and that the designation of apartheid as a crime against humanity was a plot by the Soviet Union and ANC to demonize white South Africans. The F.W. de Klerk Foundation later apologized for this statement after it provoked outrage from politicians, commentators, and ordinary citizens.

Witnessing De Klerk���s arrogance and his strange transformation from maligned dictator to a respected leader, one sees why people wanted an unambiguous, unqualified apology from the man. De Klerk���s mentality reflects that of far too many white South Africans today; those who enjoy prosperity paid for through exploitation and blood, while reluctant or totally refusing to digest and admit the scope of apartheid���s devastation. As cathartic as white guilt may be, and catharsis can be healing, it is largely unproductive. Professing the numerous inheritances of white supremacy does not halt the abuse of black workers, it does not strengthen food security, curtail the rampant brutality of the South African police, or halt the governments reckless pursuit of austerity measures that are suffocating citizens.

Politicians are not priests or imams from whom we can seek metaphysical justice. What we must demand from politicians is accountability and justice as tangible as the suffering their governance can create. White South Africans, like De Klerk, indulge in feigned ignorance not because their hearts are at fault, but because the economic relations post-apartheid have created conditions in which this ignorance and apathy can blossom.

Racism is an ideology. It is a potent assortment of myths and narratives that function to justify domination. Racism spawned in South Africa to legitimize colonial accumulation of land and livestock. With a growing settler population and industrialization, racism evolved to rationalize class hierarchy, disrupt interracial working class solidarity and justify the exploitation of Africans, Indians and Coloureds. Racial chauvinism, subtle and overt, persists in the present, so we must look towards material conditions and not just internal prejudice.

Instead of asking ���Could De Klerk have done more to ensure a peaceful transition, while also contributing towards an egalitarian future?���, we must ask ���What were the interests and external conditions that stopped De Klerk from becoming a great reformer?��� In asking the former, one can realize that De Klerk���s actions were the result of a collision between his power and rapidly changing circumstances in South Africa. Moreover, De Klerk is not exceptional in his deception at the TRC or his choice to free Nelson Mandela and begin negotiations. It is highly likely that any senior member of the National Party would have initiated such changes.

To describe apartheid merely as a system of racial segregation misses the objectives of the regime. Apartheid aimed to amass wealth for the exclusive benefit of white citizens, in particular Afrikaaners, the descendants of Dutch, German and French settlers. Racial segregation was the mechanism through which wealth was accumulated and it required the draconian control of black labor and the repression of black political organizing. It is vital to remember that Indian and Coloured people also endured persecution for the same reasons.

From 1976 a new generation of profoundly committed anti-apartheid activists and thinkers re-ignited the liberation struggle in South Africa; resistance poured from townships, rural areas and even elite spaces, such as universities. Apartheid���s economy was drastically waned in strength by capital flight, action by black labor movements, foreign sanctions and the exorbitant cost of military defense and futile attempts to contain internal anti-apartheid resistance. With the collapse of the Berlin Wall and end of the Soviet Union, Western nations that had once supported apartheid���seeing the regime as an ally in the Cold War against communism���withdrew explicit support and advocated for regime change. By the late 1980s it was pristinely clear that apartheid was unsustainable. Its contradictions manifested as the conflict that necessitated change. Divisions within the National Party, which began in the early 1970s, escalated as ���moderates��� and a minority of hard right-wingers disagreed on the future of the white society they had spent decades crafting.

Moderates within the NP were adamant to preserve white economic prosperity and soon realized it could be maintained without political supremacy. Global and local capital may have had moral problems with apartheid, but South Africa���s economy, based largely on an extractive industrial complex and cheap African labor, had to remain intact. The ANC had mostly abandoned the socialist features of its rhetoric as it also isolated leftists within the party and broader anti-apartheid movements during and leading up to negotiations. Fearing economic isolation in an age of global neoliberal hegemony and without support from the USSR, concessions had to be made. De Klerk and his party orchestrated disruptive violence and pressured the ANC (with the assistance of global capital) into a series of economic compromises because the conditions previously discussed provided the National Party leverage to enact their interests. It was a question of power, not moral character.

Apartheid was not privatized, rather capitalism endured and evolved. The uncontested reign of capitalism is pushing South Africa to become a Hobbesian nightmare, where life for millions is ���solitary, poor, brutish and short.��� De Klerk���s death reminds us that we are stuck in a stagnant present where apartheid���s legacy lives on and a new future cannot be born. Apartheid���s last president has died and yet a new black elite wields its power to pursue interests that�� mirror the objectives of an authoritarian regime they once gave their lives to defeat. The ANC has grown to become what Frantz Fanon described as the ���national bourgeoisie,��� working as ���intermediaries between capitalism and the post-colony��� and dedicated to presiding over a mode of production that has given them extravagant wealth while their subjects wallow in destitution.

The centuries-long struggle for self-determination unified millions. There may have been contentious disagreement on the nature of white supremacy and strategies to overcome its domination, but it was relatively easy to identify a common enemy. ���Born-free��� South Africans must take on the herculean task of defining their generational mission and mobilizing against a common enemy. Moralism and individualistic analysis has led some citizens to think their enemy is white monopoly capital or vulnerable migrant communities. Only when we open ourselves to seeing the true nature of power in post-apartheid South Africa can a new future be born.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers