Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 110

January 10, 2022

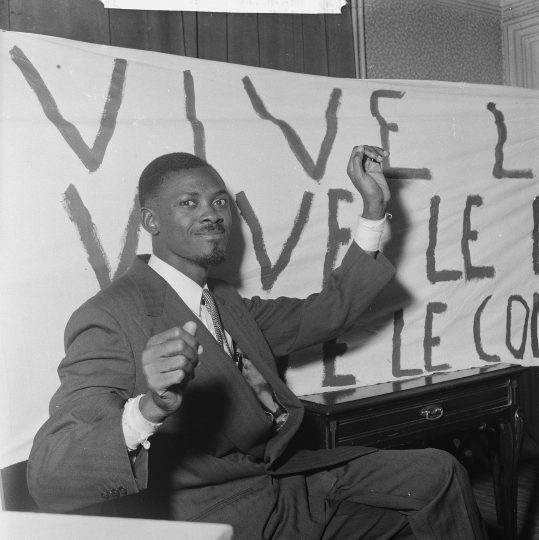

Bring Patrice Lumumba home

Image credit Behrens, Herbert (part of the Anefo archive) via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit Behrens, Herbert (part of the Anefo archive) via Wikimedia Commons. For much of the past year, there have been plans for the sacred human remains of the Democratic Republic of the Congo���s first post-independence prime minister, Patrice ��mery Lumumba, to finally be returned to his children in Belgium, and then repatriated to the Congo. Originally scheduled for a ceremony on June 30, 2021, the 61st anniversary of the country���s independence passed with Lumumba���s remains still in the custody of Belgian authorities. The planned ceremony with Belgian King Philippe, current Prime Minister Alexander de Croo of Belgium, and Congo President Felix Tshisekedi, was postponed until January 17, 2022. The official reason for the delay is the rising number of COVID-19 cases in the Congo, but the pandemic crisis is deeply entangled with a series of other political maneuvers and other crises that are undoubtedly factors in the decision.

At the center of this story, Lumumba���s family continues to be victimized. As Nadeen Shaker recently reported, his children were forced to escape to Cairo during their father���s house arrest, never to see him again. The disturbing fact that the remains of Lumumba spent another Independence Day in Belgium may provide opportunities for metaphor and analogy, but, amid the widespread complicity in this ongoing desecration, the most important outcome must be to respect the ethical and legal claims of his children, which daughter Juliana Lumumba described in an open letter to the Belgian king last year.

The story of the execution and its aftermath is well told by Ludo de Witte in The Assassination of Patrice Lumumba. On January 17, 1961, Lumumba was killed along with comrades Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito by Belgian authorities, with the support of neocolonial Kantangan separatists and the US. Two days later, Gerard Soete, Belgian police commissioner of Katanga, and his brother exhumed the body to chemically eradicate all physical evidence of their crime in order to prevent the kind of mobilization which its identification would inspire. Though the execution was kept secret for nearly a month, its announcement inspired exactly what his executioners feared, as African people throughout the world engaged in protest and other revolutionary acts of remembrance���from the well-known demonstration at the United Nations, and other cities throughout the world to a legacy in a visual, musical, and literary culture that continues to this day.

In February 1961, while the Cultural Association of Women of African Heritage organized a major protest at UN headquarters in New York, Lumumba���s widow Pauline Opango Lumumba led a march of family and supporters to the UN offices of Rajeshawar Dayal in Kinshasa. There, she requested that the UN help her receive the remains of her husband for a proper burial. After Ralph Bunche offered ���apologies��� for the New York protest, Lorraine Hansberry ���hasten[ed] publicly to apologize to Mme. Pauline Lumumba and the Congolese people for our Dr. Bunche.��� Meanwhile, James M. Lawson of the United African Nationalist Movement and other Black activists organized a wake for Lumumba at Lewis Michaux���s Harlem bookstore. When Pauline died in Kinshasa in 2014, she was still waiting to bury her husband. She, and her iconic demonstration, are memorialized in Brenda Marie Osbey���s poem ���On Contemplating the Breasts of Pauline Lumumba,��� which is part of a long line of African American efforts to uplift the Lumumba family. The immediacy of Pauline���s demands remains after 6 years.

While Lumumba���s body was dissolved in sulphuric acid, Soete, like the US lynchers of Sam Hose and so many others, kept trophies of his victims as he traveled from the Congo to Belgium, often displaying them for friends and journalists. After Soete died, his daughter Godelieve continued her father���s tradition, culminating in a bizarre 2016 interview, during which a reporter found the remains in her possession. (In her efforts to defend her father, Godelieve further revealed that his brutality was visited upon his children.) The Belgian police intervened and, for the past five years, Lumumba���s remains have been held by the Belgian government responsible for his death. In September 2020, a court finally ruled they should be returned to the family.

These most recent delays are occurring at a time when the ongoing mistreatment of human remains is receiving public attention. The case of the Morton Collection at the University of Pennsylvania led activist Abdul-Aliy Muhammad to uncover the ongoing desecration of the remains of Tree and Delisha Africa, who were killed when the city of Philadelphia bombed their family���s home on May 13, 1985, leading to the discovery that the city held additional remains of the victims of its violence against the MOVE organization.

Since 2005, in South Africa, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) created the Missing Persons Task Team to identify the remains of the Black victims of the country���s apartheid era. Drawing on the expertise of researchers with experience in similar initiatives in Argentina and elsewhere, this government project has been deliberate in its efforts to include the families of the missing at all stages, while seeing their work as integral to the larger mission of the TRC, and further representative of a larger model of repatriation of human remains and possessions. As different as these cases of violence may be, government sanction���at multiple levels and taking different forms���remains constant.

In an October 2021 program hosted by Friends of the Congo, Juliana Lumumba explained that for her, as the daughter of a martyr, repatriation and memorialization of her father���s remains were not finite events to be completed like items checked off of a to-do list. Rather, the return must be part of a wider and ongoing process: ���I told Belgium, that if we want a reconciliation we need reconciliation of memories because we can not make a reconciliation when our memories [are] so different and so contradictory.��� Juliana���s words carry a particular weight at a time when the Special Parliamentary Commission on Belgian Colonial History has received a sharply critical historical report that may or may not lead to meaningful action of the sort that the family has demanded.

Lumumba���s son Guy-Patrice Lumumba opposes Tshisekedi���s efforts to exploit the repatriation for political gain. Tshisekedi himself is familiar with some of the political challenges of memorialization after the remains of his own father, longtime popular opposition leader Etienne Tshisekdi, spent more than two years in Europe before their return in 2019 after Felix���s election. Felix is quickly losing whatever claim he had on his own father���s mantle (see Bob Elvis���s song ���Lettre �� Ya Tshitshi��� for a recent indictment of the president���s abandonment of his father���s mantle). He may find value in an association with a revered nationalist icon amid political protests from opponents concerned about his overreaching efforts to control the country���s powerful electoral commission as the 2023 election cycle approaches.

Meanwhile, the younger Tshisekedi���s international standing has been consolidated through his position as head of the African Union, where his responsibilities include negotiating for the provision of COVID-19 vaccines for member states. He recently met with President Biden and made an official visit to Israel, the latter of particular concern given its historical involvement in mercenary efforts against pro-Lumumba rebels and its ongoing role in the plunder of the Congo���s resources (to say nothing of Tshisekedi���s support for Israel���s occupation of Jerusalem and its status as an observer at the African Union). Such actions highlight the extraordinary distance between Lumumba���s legacy and Tshisekedi���s leadership.

For decades, the Lumumba family has made a series of unanswered demands through formal inquiries and legal appeals. A group of scholars and activists have also asserted the return of Lumumba���s remains must not be an occasion for Belgium to congratulate itself, but rather an opportunity for a full accounting of the colonial violence that led to the assassination and its subsequent coverup.

Hopefully soon, Lumumba���s family can mourn on their own terms and have all of their demands for justice met immediately and without equivocation.

January 9, 2022

Back from Safari

Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Photo: Sean Jacobs

Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Photo: Sean Jacobs We normally close out the year with our “On Safari” post, but this time, we’re flipping the script. We’re opening the new year with it. On the face of it, 2021 was one more year of the bleakness of the global apartheid of the COVID-19 pandemic and worldwide economic recession, but there were moments of hope that we can carry into the new year. For that, Africans have to turn their gazes away from the West���specifically Euro-America with their right-wing death cult politics or tepid liberal governments���and towards Central and South America as well as the Caribbean (or to some, Latin America) for inspiration.

There���in terms of getting rid of compliant, undemocratic elites whose interests lie with the West, multinational corporations, neoliberalism, authoritarianism, and violence���several key transformations played out (like it did before with South America’s “Pink Revolution”). It suggests our future doesn’t have to be one of neoliberal authoritarianism, ethnonationalism, and Afro-pessimism.

The old year featured a series of shake-ups in South American politics that Africans should be looking to for inspiration. First, there were midterm legislative elections in Mexico around June 2021. It doubled as a referendum for the government of President Andr��s Manuel L��pez Obrador or AMLO as he is popularly known. I was in Mexico City the summer before COVID-19 and while there I happened upon a mass rally celebrating the first anniversary of his win. For more on the kinds of reforms and how AMLO governs, see here, here, and here. I was struck by the wide popular support he enjoyed but was worried whether he could sustain it. Well, the midterm elections for the Chamber of Deputies as well as for state governments proved that his Morena party “will go into the 2024 election as a consolidated, nationwide political force, these results do also offer glimmers of hope for the opposition.”

Around the same time, last year was the election of Pedro Castillo, a leftist, as President of Peru. He won after two rounds of voting. At first, the “opposition” (basically, the right) claimed election fraud by Castillo’s Peru Libre (Free Peru Party). This was all fake news to delay the inevitable. This caused the result to be delayed for at least two weeks. In the end, however, Castillo was elected President. Castillo’s election was unprecedented as it ended, for now, the control of Peru’s elites over the presidential palace. Castillo’s bio has been summarized as “a peasant, rural schoolteacher, community patrol member, and union leader from one of Peru���s poorest provinces.” Castillo’s election slogan was “No more poor people in a rich country.” To achieve that he campaigned to reform the constitution (change the law about making sure ordinary Peruvians see the benefits of the country’s copper wealth, raise taxes on multinationals). Winning introduced a new set of challenges. Castillo won by a small margin and Congress is controlled by right-wing parties, so it will be interesting to see how he governs (his cabinet is decidedly left-wing). At the same time, his campaign also exposed the tensions between economic and social issues for the left. His campaign was unapologetically working class, which was a good thing. However, though he says he will be guided by the constitution, he promoted right-wing positions on abortion and gay rights. For a good summary of Castillo’s campaign and what is at stake in Peru see, “In Peru, the Knives Are Already Out for Pedro Castillo,” “Peru Minister: Our Socialist Government Is Under Attack. But We Can Still Win,” and what I think is the best summary of Castillo’s victory and how much work he has ahead of him, the video commentary by Nando Vila on YouTube.

Then there was the election of Xiomara Castro as President of Honduras at the end of November 2021. She will be sworn in on January 27, 2022. In 2009, her husband, the democratically elected president Manual Zelaya, was overthrown by a conspiracy of the United States government and Honduras’ right-wing elites. (They used Hugo Chavez as a bogey to remove him; predictably the Western media and think tanks fell in line. At the time, Castro was at the lead of those forces resisting the coup.) For some background on the elections in Honduras and their meanings, I can recommend these by Branko Marcetic (“Washington Tried to Destroy Honduras���s Left. Now It���s Back in Power“), Francisco Dominguez (“Honduras Can Break Free of Washington and Neoliberalism“), as well as Suyapa Portillo (“With the Election of Xiomara Castro, a New Feeling of Hope Has Arrived in Honduras“). For the 2009 events around Zelaya’s ouster (Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton had starring roles), we can recommend these pieces by Greg Grandin and Belen Fernandez,

But even more significant than what happened in Honduras and Peru were the elections in Chile at the end of November 2021, which had been the poster child for neoliberalism. And though it has, post-Pinochet, saw the election of a center-left government (Michele Bachelet), the election of 35-year-old Gabriel Boric, an openly leftist candidate to president, ushers in a new era. Before Boric’s election, in an earlier poll, several feminist socialists got elected to run municipal and state governments, including the capital Santiago. Before that, Chileans elected representatives to a new constitutional convention to rewrite the constitution inherited from the Pinochet years. At the head of the convention is a president who identifies as indigenous and an equal number of women (this is a victory) as men are represented. As to the significance of Boric’s victory, these analyses by Rene Rojas are worth watching (here and here). So is this, this, and this.

It would be worth it for social movements and political parties of the left on the continent to study what went down in Chile (and of course Peru, Mexico, and Honduras) in terms of how you build a winning political coalition, present a program that is about economic justice and can win elections. As I tried to relate it to our followers on Twitter, think about what happened in Chile like this: It’s like Fees Must Fall or Rhodes Must Fall took electoral politics seriously, maintained that energy over 10 years, translated it into an electoral platform, found commonalities via coalitions, and took power in South Africa.

Last, but not least, was the example of the Caribbean��island of Barbados. Its Prime Minister is Mia Mottley. African leaders, mostly male and old, can learn a thing or two from her about forthrightness about the two major connected challenges of our time: climate justice and global inequality, not in some corner when no one is watching, but at COP26 and the UN General Assembly. She also oversaw her country, finally, declaring independence from British colonialism. And then to top it all, her government proposed giving all its citizens a universal basic income grant. As a bonus, Barbados named Rihanna (yes, the same Rihanna who spoke out on Israeli apartheid) as a national hero.��

In this new year, we want to especially encourage submissions that explore these connections and lessons, as the examples from the continent are mostly depressing. Please send them in.

Finally, some shameless self-promotion: This will be an exciting year for us; we have two podcasts���AIAC Talk and Africa Is a Country Radio; will increase our video production; will have a new cohort of fellows; will keep bringing you original analysis and opinion; and continue to build partnerships with organizations as diverse as Black Women Disrupt the Web, AJ Plus, Institute for African Studies in Sharjah, Ghana Studies Association and International Congress of African and African Diaspora Studies, among others. Also, check out my new football research and writing project, .

Welcome back.

Back from safari

Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Photo: Sean Jacobs

Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Photo: Sean Jacobs We normally close out the year with our “On Safari” post, but this time, we’re flipping the script. We’re opening the new year with it. On the face of it, 2021 was one more year of the bleakness of the global apartheid of the COVID-19 pandemic and worldwide economic recession, but there were moments of hope that we can carry into the new year. For that, Africans have to turn their gazes away from the West���specifically Euro-America with their right-wing death cult politics or tepid liberal governments���and towards Central and South America as well as the Caribbean (or to some, Latin America) for inspiration.

There���in terms of getting rid of compliant, undemocratic elites whose interests lie with the West, multinational corporations, neoliberalism, authoritarianism, and violence���several key transformations played out (like it did before with South America’s “Pink Revolution”). It suggests our future doesn’t have to be one of neoliberal authoritarianism, ethnonationalism, and Afro-pessimism.

The old year featured a series of shake-ups in South American politics that Africans should be looking to for inspiration. First, there were midterm legislative elections in Mexico around June 2021. It doubled as a referendum for the government of President Andr��s Manuel L��pez Obrador or AMLO as he is popularly known. I was in Mexico City the summer before COVID-19 and while there I happened upon a mass rally celebrating the first anniversary of his win. For more on the kinds of reforms and how AMLO governs, see here, here, and here. I was struck by the wide popular support he enjoyed but was worried whether he could sustain it. Well, the midterm elections for the Chamber of Deputies as well as for state governments proved that his Morena party “will go into the 2024 election as a consolidated, nationwide political force, these results do also offer glimmers of hope for the opposition.”

Around the same time last year was the election of Pedro Castillo, a leftist, as President of Peru. He won after two rounds of voting. At first, the “opposition” (basically, the right) claimed election fraud by Castillo’s Peru Libre (Free Peru Party). This was all fake news to delay the inevitable. This caused the result to be delayed for at least two weeks. In the end, however, Castillo was elected President. Castillo’s election was unprecedented as it ended, for now, the control of Peru’s elites over the presidential palace. Castillo’s bio has been summarized as “a peasant, rural schoolteacher, community patrol member, and union leader from one of Peru���s poorest provinces.” Castillo’s election slogan was “No more poor people in a rich country.” To achieve that he campaigned to reform the constitution (change the law about making sure ordinary Peruvians see the benefits of the country’s copper wealth, raise taxes on multinationals). Winning introduced a new set of challenges. Castillo won by a small margin and Congress is controlled by right-wing parties, so it will be interesting to see how he governs (his cabinet is decidedly left-wing). At the same time, his campaign also exposed the tensions between economic and social issues for the left. His campaign was unapologetically working class, which was a good thing. However, though he says he will be guided by the constitution, he promoted right-wing positions on abortion and gay rights. For a good summary of Castillo’s campaign and what is at stake in Peru see, “In Peru, the Knives Are Already Out for Pedro Castillo,” “Peru Minister: Our Socialist Government Is Under Attack. But We Can Still Win,” and what I think is the best summary of Castillo’s victory and how much work he has ahead of him, the video commentary by Nando Vila on YouTube.

Then there was the election of Xiomara Castro as President of Honduras at the end of November 2021. She will be sworn in on January 27, 2022. In 2009, her husband, the democratically elected president Manual Zelaya, was overthrown by a conspiracy of the United States government and Honduras’ right-wing elites. (They used Hugo Chavez as a bogey to remove him; predictably the Western media and think tanks fell in line. At the time, Castro was at the lead of those forces resisting the coup.) For some background on the elections in Honduras and their meanings, I can recommend these by Branko Marcetic (“Washington Tried to Destroy Honduras���s Left. Now It���s Back in Power“), Francisco Dominguez (“Honduras Can Break Free of Washington and Neoliberalism“), as well as Suyapa Portillo (“With the Election of Xiomara Castro, a New Feeling of Hope Has Arrived in Honduras“). For the 2009 events around Zelaya’s ouster (Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton had starring roles), we can recommend these pieces by Greg Grandin and Belen Fernandez,

But even more significant than what happened in Honduras and Peru were the elections in Chile at the end of November 2021, which had been the poster child for neoliberalism. And though it has, post-Pinochet, saw the election of a center-left government (Michele Bachelet), the election of 35-year-old Gabriel Boric, an openly leftist candidate to president, ushers in a new era. Before Boric’s election, in an earlier poll, several feminist socialists got elected to run municipal and state governments, including the capital Santiago. Before that, Chileans elected representatives to a new constitutional convention to rewrite the constitution inherited from the Pinochet years. At the head of the convention is a president who identifies as indigenous and an equal number of women (this is a victory) as men are represented. As to the significance of Boric’s victory, these analyses by Rene Rojas are worth watching (here and here). So is this, this, and this.

It would be worth it for social movements and political parties of the left on the continent to study what went down in Chile (and of course Peru, Mexico, and Honduras) in terms of how you build a winning political constitution, present a program that is about economic justice and can win elections. As I tried to relate it to our followers on Twitter, think about what happened in Chile like this: It’s like Fees Must Fall or Rhodes Must Fall took electoral politics seriously, maintained that energy over 10 years, translated it into an electoral platform, found commonalities via coalitions, and took power in South Africa.

Last, but not least, was the example of the Caribbean��island of Barbados. Its Prime Minister is Mia Mottley. African leaders, mostly male and old, can learn a thing or two from her about forthrightness about the two major connected challenges of our time: climate justice and global inequality, not in some corner when no one is watching, but at COP26 and the UN General Assembly. She also oversaw her country, finally, declaring independence from British colonialism. And then to top it all, her government proposed giving all its citizens a universal basic income grant. As a bonus, Barbados named Rihanna (yes, the same Rihanna who spoke out on Israeli apartheid) as a national hero.��

In this new year, we want to especially encourage submissions that explore these connections and lessons, as the examples from the continent are mostly depressing. Please send them in.

Finally, some shameless self-promotion: This will be an exciting year for us; we have two podcasts���AIAC Talk and Africa Is a Country Radio; will increase our video production; will have a new cohort of fellows; will keep bringing you original analysis and opinion; and continue to build partnerships with organizations as diverse as Black Women Disrupt the Web, AJ Plus, Institute for African Studies in Sharjah, Ghana Studies Association and IRAADS, among others. Also, check out my new football research and writing project, .

Welcome back.

AFCON is decolonization

Photo by Jannik Skorna on Unsplash.

Photo by Jannik Skorna on Unsplash. The 33rd edition of the African Cup of Nations began today, Sunday, 9 January, in Cameroon. AIAC founder and editor Sean Jacobs joins Will to talk about the history of the tournament, its contemporary politics, and its relationship to the hegemony of European football. The most important question of all, of course, is who will win this year���s showpiece? Listen below for some predictions.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/b6fd133e-d074-478d-82ba-a21563f71884/aiac-talk-afcon.mp3

December 20, 2021

South Africa’s morbid symptoms

Photo by Pawel Janiak on Unsplash

Photo by Pawel Janiak on Unsplash In the final episode of AIAC Talk for the year, Will is joined by AIAC founder and editor Sean Jacobs for a conversation with Steven Friedman; a South African newspaper columnist, former trade unionist, and political scientist who specializes in the study of democracy.

Professor Friedman is the author of two new books reflecting on South Africa���s tortured past and its dysfunctional present, namely Prisoners of the Past���South African Democracy and the Legacy of Minority Rule, as well as One Virus, Two Countries: What COVID-19 Tells Us About South Africa. Why has South Africa been unable to implement wealth distribution for the masses despite its transition to a robust, liberal democracy? In the throes of a political impasse, which social forces are capable of bringing about change? Or is a further slide to disorder more likely?

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/89955ec9-c775-46f4-9741-bccfc63d1b33/aiac-talk-steven-friedman.mp3December 16, 2021

Ignorance, denial and insurgency in Mozambique

Moc��mboa da Praia. Image credit A Verdade via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Moc��mboa da Praia. Image credit A Verdade via Flickr CC BY 2.0. It���s been four years now since a small group of armed men targeted a police post in Moc��mboa da Praia in northern Mozambique, a small act that grew into a major insurgency targeting civilians, occupying territory and forcing out a major energy company preparing to extract gas offshore in the province of Cabo Delgado. To date, 3500 people have been killed in the armed conflict and 745,000 displaced. The insurgency came to an apparent halt this summer after Rwandan armed forces, and then the SADC mission to Mozambique (SAMIM), arrived in Mozambique to fight it. The current relative calm on the battlefield has invited reflections on whether the military approach is working and what should come next. How could the insurgency in Mozambique grow in this way, and is an international military intervention the right response to stop it?

Much of the current debate among policy makers and analysts makes important assumptions about why and how insurgency begins, pointing to either external influences, such as transnational Islamist terrorism, or the long-term lack of development and marginalization of people in the northern region of Mozambique, leading to grievances that motivate the young and poor to join the insurgency. While these aspects certainly have played a role in Mozambique, we need to take into account the government���s response and how it has helped escalate the conflict and strengthened the insurgency. Ignorance and denial have been core government attitudes that left the party in power, Frelimo, with little understanding and capacity to respond to the growing unrest in Cabo Delgado. Instead, the response of choice���severe repression and a lack of respect for human rights���has nurtured the rebellion. The current stability is therefore, in all likelihood, temporary.

A slowly growing insurgencyThe conflict began with the formation of a religious Islamic sect in 2007, which sought to withdraw its members from the state. The first confrontations with the local police took place in 2015-2016, but armed violence only began in October 2017. The group is known as Al-Shabaab (���youth��� in Arabic) or Ahlu Sunnah Wal-Jam��a. It pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2018 and was recognized as a wing of Islamic State���s ���Central African Province��� in July 2019, but it remains unclear what the implications of this relationship are. Although violence initially was small-scale and directed at state armed forces, the insurgency began to target more civilians in 2019 and perpetrated severe forms of violence, such as beheadings, against them throughout 2020 and beyond.

In 2020, the nature of the war changed completely when the armed group managed to occupy district towns in March for a few days, and then captured and occupied the town of Mo����mboa da Praia in August for a year. International attention to the conflict suddenly skyrocketed in March 2021, when the armed group conducted the most sophisticated operation yet, an attack on the city of Palma, with several dozen people dead, including expatriate workers on the liquified natural gas processing plant owned by TotalEnergies. This led to a major evacuation mission conducted mainly by helicopters operated by the Dyck Advisory Group (DAG), a private military company supporting the Mozambican government, and triggered a regional impetus to help Mozambique manage the crisis. TotalEnergies saw the events in Palma as a reason to temporarily halt its gas exploration project on the coast in April.

An inadequate government responseEarly analyses of the conflict pointed to the fact that initial repressive actions by the local government and security forces were a contributing factor in the radicalization of the conflict to armed violence in October 2017. Until early this year, the police forces were in charge of responding to the insurgency, with their infamous Rapid Intervention Unit (RIU), which allegedly committed indiscriminate violence against civilians. In January, the government assigned the task to the military and appointed a new military commander, who, however, shortly afterwards died of COVID-19.

Up until the spring of 2021, the government resisted inviting international military deployments and relied on private companies for military and logistical support and bilateral training missions. Officially, President Nyusi was eager to protect ���Mozambique���s sovereignty,��� in an apparent reference to a history of foreign meddling when Rhodesia and Apartheid South Africa supported the rebel group Renamo on Mozambican soil. Nyusi, instead, relied on old and trusted international partners, but the results were mixed. The Russian Wagner group didn���t stay long, leaving Mozambique in November 2019 after a two-month deployment and conflicts with the Mozambican authorities about the counterinsurgent strategy. In April 2020, the Mozambican government hired DAG, led by Colonel Lionel Dyck who helped Frelimo fight the Renamo rebels in the 1980s. After a year of activity, the Mozambican government let the contract with DAG expire.

Only after the traumatic attack on Palma in March 2021 did the Mozambican government change course and accept international military deployments to fight the insurgency. In July, the Rwandans sent troops to northern Mozambique. The SADC mission was launched in August. In a militarily and symbolically significant operation early August, Rwandan and Mozambican armed forces retook Moc��mboa da Praia from the insurgents. However, many analysts agree that the success of the international forces is only temporary, as the root causes of the conflict have been left unaddressed, and the insurgents���in typical guerrilla style���have dispersed to regroup and attack elsewhere. Refugees have begun to return to their areas of origin, and international aid organizations have promised to support them with aid and projects so that socio-economic reasons to support the insurgency could disappear. But will this work?

The state has lost trust and remains unaccountableFrom the beginning, the Mozambican government did not seem interested in any of the many theories that scholars developed about the origins of the insurgency. The government actively hindered scholars and analysts��� efforts to speak to officials, militants and the displaced in the region, and even detained local journalists and expelled a British journalist covering the insurgency. After blaming various illegitimate groups in society and foreigners, in his statements on the conflict, President Nyusi has largely settled on the perspective that the insurgency has external origins and transnational terrorism is responsible for the violence. This is a perspective that Rwanda supports, as it helps justify why Rwanda is militarily active in Mozambique���an issue that has raised a lot of suspicions. And it has triggered US interest in the conflict; the US designated the armed group an affiliate of ISIS and a foreign terrorist organization in March 2021, an action many observers say will not necessarily help solve the conflict.

Mozambique���s counterinsurgency response has also raised a lot of criticism, as it failed to protect civilians. Problems of coordination between DAG and Mozambican ground forces lead to civilian casualties and friendly fire casualties among the Mozambican security forces. When the government forces took back Palma in March, they looted and vandalized private businesses, including banks, and residences. Amnesty International accused private contractors, such as the DAG, as well as state armed forces of human rights abuses, and the police of harassment and extortion. As a result, the civilian population does not trust the state and its (hired) armed forces to protect them.

The government recognizes that the armed conflict is not over yet. But it does not recognize its own role in escalating the conflict and its comprehensive responsibility in solving it. Joseph Hanlon, long-term observer of Mozambique, inspired by the failures in Afghanistan, frequently cites in his newsletter those voices that warn of military solutions to armed rebellion, emphasizing instead long-term development efforts. But much of the government response is shaped by catering to the oil and gas firms, as a recent reshuffle of ministers after a meeting with Exxon executives���who underlined the importance of further security improvements before their activities could continue���shows. In remarks on Armed Forces Day in September, President Nyusi stated that the main priority is improving security for the gas projects.

Overall, the government has not only obscured the origins of, but also the response to the Cabo Delgado insurgency. Transparency around the government���s counterinsurgency strategy is lacking. Contracts with private security companies are not made public, and Parliament has not had any say in the deployment of foreign troops. It���s no accident then that a recent ISS policy brief recommends completely rebuilding state institutions in the region and freeing them of corruption to build ���islands of integrity.��� A new and different state is necessary to manage the complex problems in the region, but is it possible under the current regime that has fed the conflict?

December 15, 2021

Against a willing amnesia

Benin bronze. Image credit Tommy Miles via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Benin bronze. Image credit Tommy Miles via Flickr CC BY 2.0. The past five years have seen a flurry of activity around issues of restitution of African material heritage, resulting in new reports, new books and even, new returns. Along with this sudden surge in activity there has been an escalation in debate around these questions, where positions once thought to be entrenched, racist, conservative, and considered mainstream, seem to have shifted dramatically. In the frenzy, it can begin to feel as if things are changing and that society is progressing. But we���d do well to pause for deeper dives and more systematic remembering of what has come before.

Two books, B��n��dicte Savoy���s Africa���s Struggle for its Art and Barnaby Phillips��� Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes, do this in different ways, but bring to us the important opportunity to remember again. In calling on us to remember, Savoy and Phillips separately�� recenter the intentions, objectives, and justices that restitution seeks, the violences and obstructions already undertaken, and offer some strategies for ensuring greater success this time around. Savoy, an art historian, who along with Senegalese economist, Felwine Sarr, co-authored a report for the French government on returning African cultural artifacts, states in the new English language translation of her book ��(forthcoming 2022):

nearly every conversation today about the restitution of cultural property to Africa already happened forty years ago. Nearly every relevant film had already been made and nearly every demand had already been formulated. Even the most recently viral videos on social media��� by the Congolese activist Emery Mwazulu Diyabanza, had already been scripted in many minds by the mid-1970s. What do we learn from this?

Phillips is a former correspondent with the BBC and Al Jazeera and his Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes is a detailed telling of the story of�� the approximately 4,000 objects in bronze, wood, and ivory taken violently in the plundering, by British forces in 1897, of the Kingdom of Benin (in present day Nigeria). . The story of the Benin Bronzes is an important one within the restitution discourse for various reasons, but perhaps most specifically because the terms of their taking were so clearly punitive and incredibly violent, and the claims for their return hold a relatively clear moral, geographical, and art historical grounding. Phillips looks to lay out in substantial detail the chronological telling of the context of their making, their theft, and their distribution across museums of the global north.

Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes is written first and foremost from the position of a personal vested interest in the story of the bronzes, and the impact that the violence and destruction that took place in their looting has had on a people, their culture and contemporary society. The book details the majesty and sophistication of the Benin Kingdom, using a range of oral histories, from those of the Benin royal family, their associates, as well as African academic writing on the subject. The bulk of the sourcing comes, however, from extensive historical British records. Phillips tells of the increased British activity in the area and the inevitability of a clash with the kingdom by colonialists. It details the widespread violence and destruction of the city during the British expedition, but also the seemingly indifferent and disconnected claim to the totality of the kingdom���s vast cache of exquisite and sophisticated court art pieces by the British: for the purposes of financial resourcing of the punitive expedition itself. Phillips then tracks the movement of these objects, through dynasties of families in Britain, and through museums of the world. He ends with a discussion of the attempts to have these returned to Nigeria, particularly since its independence in 1960, as part of a rebuilding of a society from the ashes of colonialism, and the Biafran War���the civil war that raged in Nigeria in the late 1960s and divided the country.

The book is sympathetic primarily to the voices and justified demands of Nigerians, and discusses in much detail the many turns of deceit and violence at the hands of the British in this long saga. It is, however, also written in a kind of specifically European tone of hazy ���even-handedness��� that spends overly-significant page space on issues such as the Nigerians��� unwillingness to discuss the rumors of human sacrifice by the Benin Kingdom that the British used to partly justify their actions, and on his argument for the likely accidental setting alight of the entirety of kingdom by the British forces. Both these issues become almost petty in the greater picture of total wanton destruction, violence and death not only at the moment of the expedition but also continuously after it���in physical occupation, and in spiritual and epistemic erasure. This marks the book as perhaps slightly out of step with some of the more contemporary literature emerging out of this moment within the broader restitution issue. This book possibly serves as a useful detailed description for a reader unfamiliar with the subject but offers little to the broader discourse on this issue.

Though Savoy���s forthcoming book tracks histories that strongly overlap with that of Phillips,��� it serves a far more urgent and direct call to remember these histories, and to lay bare the wilful amnesia and hidden obstruction that have previously completely derailed efforts at justice and repair. Savoy���s report that she co authored with Sarr commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron about France���s role in plundering African heritage, was arguably the spark that reignited the now raging fire of restitution of African heritage. Africa���s Struggle For Its Art is concerned primarily with the context of historical West Germany. Nonetheless, her deep working through the archives���initiated first for the commissioned report���reveal a vital understanding of the global story of struggles for African heritage restitution and its historical defeat.

Using primarily the meticulous archiving by West German bureaucrats in museums, foreign affairs bureaus, and embassies, Savoy pieces together the early and relatively substantial attempts at opening dialogue on access to African heritage by Africans. Savoy puts Africans front and center of the dialogue and push for justice���as initiators of engagements on access to African history. She tracks in return, the systematic undermining of these efforts, with obstructive stonewalling and delay tactics that completely dismissed any attempt at even the most modest requests for engagement. Savoy argues also, for the extent to which the arguments against restitution have their roots in long standing racism, in heritage staff whose careers begin through Nazi association and administration, and in attempts by European art historians, museum personnel and curators, and West Germans in particular, to claim place and prestige amongst themselves.

By tracking these arguments and the kinds of internal planning and plotting among museum officials, Savoy also identifies very clearly the shaky foundations of many arguments against restitution still spouted today. Not only are many of these racist, but also Savoy demonstrates the degree to which many of these arguments are based on out-and-out lies. For example, in the 1970s one German museum director, Friederich Ku��maul, cited by Savoy, spouted entirely fictional statistics and made hearsay-based accusations of thefts from African museums���a line Phillips, for example, repeats in Loot as regards hearsay about thefts from the Benin Museum in 1980, and a story easy to corroborate through UNESCO illicit trafficking databases.

Savoy lifts the veil on the construction of an idea of the museum as an institution: as a benevolent custodian of universal heritage, distanced from politicking, lies or corruption and history. Rather, museums have been ruthless in their efforts to retain their hoard and discredit in pernicious ways their African peers. These efforts have been incredibly successful, wearing away at African energies and investments in good faith engagement. They undermined their own structures, such as UNESCO, and left cultural experts and the cultural intelligencia of newly independent African countries empty handed just as Africa���s young nations began to shift away from believing in the potentials of culture that characterised the early days of the Dakar World Festival of Black Arts in 1966 or FESTAC in 1977.

At certain points, Savoy���s historic rendering has an eerie sense of d��j�� vu, and a kind of sinking feeling of realising that the late 1970s looked much like our contemporary moment in terms of efforts toward and a zeitgeist in favor of restitution. Her book serves as a warning that we have been here before and that last time we lost the battle. But it also serves as a kind of arsenal, to not fall for previous tricks, to expose old lies and to build upon what was already built by so many African and allies over decades.

December 14, 2021

A dedicated teacher of the working class

Oupa Lehulere, right, with Lucien van der Walt, left, and Eddie Cottle, middle. Image credit Lucien van der Walt via Facebook.

Oupa Lehulere, right, with Lucien van der Walt, left, and Eddie Cottle, middle. Image credit Lucien van der Walt via Facebook. Oupa Lehulere���s political life began as a schoolchild where he played a central role in organizing the 1976 student uprisings in Cape Town. He would develop into one of the country���s foremost organic intellectuals, with an unmatched grasp on political economic theory and a well-known penchant for a sharp polemic to settle debates.

Over decades he helped build Khanya College, a popular education organization that taught the importance of social movements and precarious worker initiatives. He never wavered in his commitment to revolutionary Marxism and remained dedicated to building working class organizations throughout his life.

Khaya College emerged in the mid-1980s, a tumultuous period in the fight against apartheid. Its primary goal was to create a learning space and bridge to tertiary education for black and marginalized students who could not access white universities. It was established by the South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED), which was at the time led by former Robben Islander, Trotskiest, and educationalist, Neville Alexander.

By 1994 SACHED evolved to NGO status, and Khanya College became a base for activists of many persuasions and backgrounds, and also a home for debates of the time. The motto of the organization was ���Education for Liberation.���

Fast forward two decades, and as young activists, we had been politicized in the wake of the massacre at Marikana and swept up by the struggles in the universities a few years later. The resounding defeat of the Fallist movement left many of us dejected and demobilized. It was Oupa who reminded us that the preconditions for progressive change and revolutionary victory are forged in the historic school of harsh conflicts and cruel defeats.

He took many of us under his wing and pushed us to study, to think, to debate and, most importantly, to continue to engage in organized politics. In the process, he challenged our thinking and our practice. As a teacher and an interlocutor he expertly guided us through a journey to sharpen the contradictions of the ideological debates that were ignited under the banner of Fallism.

Many of our comrades joke that it was Oupa that made us finally meet our ���ideological Damascus moment.��� Oupa waged a persistent struggle to liberate South African Marxism from the chains of Eurocentrism. At the same time, he insisted that class must be central to any liberatory politics. After years of denial, many of our comrades finally committed to revolutionary socialist ideas���to grounding in a deeper understanding of the political economy of capitalism and its development and impact in the South African context.

Once again, our mentor took us on this journey. Between 2017 and 2020, Oupa ran a reading group at Khanya College on Marx���s Capital. Every second Sunday for more than two years we worked through the magnum opus, line by line. The attention to detail was incredible. The slightest moment of miscomprehension was picked up on and thrashed out until, as Oupa would say, we had ���ironed out the slippages.��� Oupa���s approach to theoretical study reflected his approach to struggle. There are no shortcuts to either.

For us, comrade Oupa was not ���one of the activists from the 1980s������he continued to think, to write and to fight until the bitter end. He will be remembered as a teacher and mentor and as a dedicated servant of the working class.

Lala Kahle Comrade Oupa, Robala Kagotso Comrade Oupa.

December 13, 2021

The war on T��ra

Niger riverbed. Image credit Jean Rebiff�� via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Niger riverbed. Image credit Jean Rebiff�� via Flickr CC BY 2.0. On the night of November 26, a French military convoy of around 100 vehicles stopped at the Nig��rien town of T��ra 30 km from the border with Burkina Faso. The convoy, La Voie Sacr��e (the Sacred Way), was transporting weapons and equipment from Ivory Coast to Mali as part of France���s counterinsurgency operation against Islamic State jihadists. It had already faced angry protesters in Burkina Faso but nothing quite like what it was to meet the next morning in T��ra.

By 11am the convoy was surrounded by around 1,000 Nig��riens, throwing stones and wooden sticks, shouting ���Down with France!��� According to eyewitnesses interviewed by the French newspaper Lib��ration, a French Mirage-2000 jet dropped tear gas grenades. ���After that,��� said Faisal Hamadou ���the soldiers gathered and opened fire. They fired in front of them, not above, nor to left or right. It was not a single soldier who fired, several of them opened fire.��� The French commander, Captain Fran��ois Xavier, told Radio France Internationale (RFI) his men used non-lethal weapons. He said rifles were only used for warning shots.

Two protesters were shot dead. A third later died in hospital in the capital Niamey. Thirteen others were wounded, and some are still in a critical condition. The Nig��rien Interior Minister confirmed the casualties but declined to say whether the lethal shots were fired by French soldiers or the Nig��rien gendarmes accompanying them.

TV5 Monde interviewed eyewitnesses and a brother of one of the dead, who maintains the French soldiers did the firing. Videos circulating on social media record a Nig��rien gendarme shouting at the French soldiers to stop shooting. French media, however, has so far chosen to highlight images of five Nig��riens striking one of the convoy���s trucks with wooden sticks.

When we filmed our BBC2 Arena documentary African Apocalypse (now serialized on BBC Global), we were refused permission to travel to T��ra. It was far too dangerous, the authorities told us. We were tracing the route of the French column led by the notoriously brutal commander, Captain Paul Voulet that left tens of thousands of Nig��riens dead. One- hundred-and-twenty years later the memories of those massacres that created the colony (and the country���s current borders) are seared into the consciousness of all those we met, old and young alike. Voulet���s violence is still vivid because it marked the start of people���s deplorable present in the world���s poorest country.

We can only presume that the people of T��ra feel the same. They live at the epicentre of an eight-year conflict between IS-affiliated jihadists and the French and Nig��rien military. More than 500 civilians have been killed this year alone. Populations in more than 100 villages have been displaced to make way for a French military base in nearby Ouallam. In October, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) warned that nearly 600,000 people there are exposed to food insecurity in a ���major crisis.���

T��ra is a significant location in the history of Niger and Burkina Faso, for it was here in 1983 that President Seyni Kountch�� (Niger) and President Thomas Sankara (Burkina Faso) committed their countries to the principles of non-alignment under the T��ra Declaration.

Thomas Sankara remains an icon across Africa. His short-lived radical government made the sort of leaps in land redistribution and mass social welfare that today���s protesters in T��ra could only dream of. His policies and rhetoric made him a threat to the Fran��afrique, a network of business and political connections that have kept Paris one of the foremost powers in Africa since independence. He was murdered in a military coup in 1987 that many suspect was carried out with the support of the CIA and French intelligence. In October this year a trial of 14 men accused of his killing opened in the Burkina Faso capital, Ouagadougou. French president Emmanuel Macron promised in 2017 to release all classified documents on the case. So far three batches have been opened, but none from the office of Fran��ois Mitterrand, the French president at the time of Sankara���s murder.

The opening of the archives on the 1899 Voulet invasion is also among calls by the Nig��rien communities we worked with for our film. In submissions made to the United Nations Special Rapporteur for the Promotion of Truth and Justice they demand a full investigation, a series of memorials and reparations. But first they ask for an acknowledgement from France and an apology to Nig��riens for the 1899 decimation that ushered in its colonial rule.

This week, in the wake of the deaths at T��ra, the Nig��rien authorities refused permission for a demonstration organised by local NGO Tournons La Page-Niger. Earlier, Nig��rien President Mohammed Bazoum defended the French presence in the Sahel, saying its departure would lead to ���chaos.��� The Interior Ministry has opened an investigation ���to determine the exact circumstances of the tragedy at T��ra and locate responsibilities.��� Niger���s Human Rights Commission is also investigating. Let us hope the French military cooperates fully and openly with both inquiries. Perhaps it can be a new step on the road toward a meaningful Truth and Reconciliation for colonialism in Africa���not just by France, but all the former colonial powers.

Lemkin and Nylander���s BBC Arena film continues on BBC Global till December 20.

December 12, 2021

Not much to see here

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa and Herman Mashaba, former mayor of Johannesburg. Image credit Government ZA on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

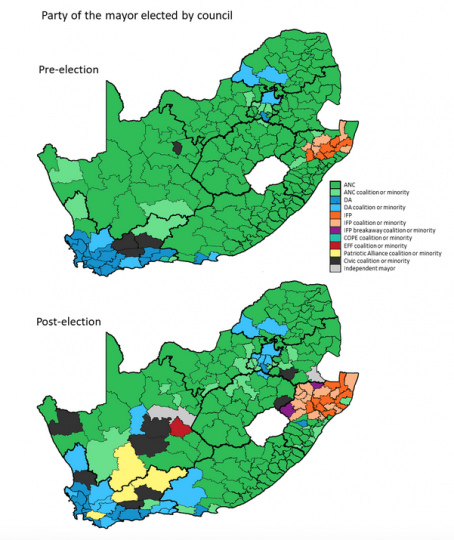

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa and Herman Mashaba, former mayor of Johannesburg. Image credit Government ZA on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. In South Africa���s November 1 local government elections, the African National Congress (ANC) got 46% of the country-wide vote, falling below an outright majority for the first time.

The party���s declining hegemony, its failure to suppress factionalism and to keep a tight rein on state patronage, now the possibility that it will need to form a coalition government after national elections in 2024, these developments are generating a surge in confidence in the prospects of alternatives, encouraging breakaways and formations of other new parties. Commentators have stressed the drama of the result, announcing a period of sweeping change, but the ANC���s own tally obscures lines of enduring continuity.

The party system is fragmenting, but this is happening within a framework of political divisions and alliances constructed by Apartheid and the anti-Apartheid movement. There is no clear process of realignment, no plausible social force around which a new regime might consolidate, with just the tentative emergence of a new right and a resurgent movement of civics and residents��� associations. What this portends is a period of disorganization, government by a disintegrating African nationalist movement, increasingly externalized from the ANC itself into inter-party coalitions.

Lines of continuityThe decline of dominant parties across the world is usually precipitated by breakaways. South Africa is no exception. The ANC has fallen below a majority, but if we count it together with its democratic-era offshoots, then the 62% it got in 2000 is still a fraction above 60% today. The difference with its current total is made up by Julius Malema���s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF, 10%), four other parliamentary parties (2%), along with at least 23 minor additions with seats in local councils (1.5%). These occupy a spectrum from good government to corrupt, and from moderate to radical positions on black economic empowerment. Their weight is towards the latter, an expropriative nationalism, often nakedly capitalistic and increasingly chauvinistic. But the basic point is that the headline story of post-Apartheid electoral history is not so much the rise of novel forces, as the gradual, gathering decomposition of the ANC itself.

The progress of other parties has been limited. The official opposition, the liberal Democratic Alliance (DA), is back where it was two decades ago, at 21% of the electorate. In the interim, it advanced by consolidating the support of racial minorities and by making small inroads into the black vote. In the last few years, however, it has been squeezed by the growth of Afrikaner and coloured nationalism, seen in the advance of the Vryheidsfront Plus (VF+, 2%) and the emergence of the Patriotic Alliance (1%), the Cape Coloured Congress (0.25%), and more local parties (0.1%) such as the Northern Alliance in Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). The DA���s efforts to shore up these bases, by purging black leaders, dropping policies of affirmative action, and playing up its defense of racial minorities, has rolled back earlier efforts to attract black voters. This might have opened up some room along the party���s social liberal left, but the performance of Patricia de Lille���s breakaway GOOD indicates that this space is limited (0.6%).

South African voters, from this vantage point, look stagnant, group-loyal. Indeed, the next largest family of parties is still those that formed around old apartheid Bantustan and ���own affairs��� administrations. KwaZulu���s Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) won 9% of the vote in 2000. Today, with its breakaways, it has 7%. The share of the electorate held by other ���homeland��� parties has been negligible, but they still win council seats in the former Gazankulu (1), KwaNdebele (1), Bophuthatswana (6), and QwaQwa (3), as do the remnants of Indian House of Delegates parties in Durban (2). Beyond these, political Christianity (1%) and Islam (0.25%) have been and remain marginal.

Potential sources of realignmentThe advocates of change stress the emergence of two potential sources of realignment, but these are currently small, partly the product of fragmentation in larger parties, so their prospects remain highly uncertain.

In 2020, the DA���s former mayor of Johannesburg, Herman Mashaba, formed a party called ActionSA. In November���s elections, it centered its platform around a broad South African nationalism. It took a xenophobic line and committed to throwing out the politicians, fixing the state, and unleashing the developmental potential of free markets. It drew off the DA���s fledgling black vote, generated support from racially pragmatic whites in the suburbs, then expanded incursions into ANC strongholds in the townships. Focusing its energies on Johannesburg and surrounds, it won 16% in the city, 9% in the province of Gauteng, but just 2.4% nationwide.

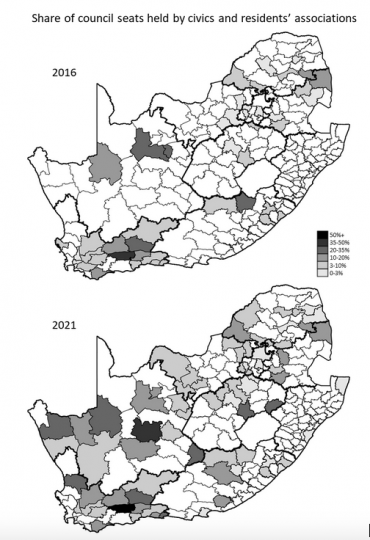

National attention has focused on this metropolitan center, but we also see an equal, sometimes intersecting, but also quite distinct development across the towns and villages of the hinterland. South Africa has an old tradition of local civics and residents��� associations. Historically, these have been fairly strictly divided along racial lines. In some cases they have entered elections, where their impact in post-Apartheid years has been minimal. In 2000, 37 of these associations claimed seats in local councils, with a combined national vote of just 0.8%.

In recent years, a crop of more multiracial, cross-class vehicles is ascendant. In some cases these are the product chiefly of bourgeois initiative, but in many others they are rooted in the efforts of the working class and poor people. A number have been organized in response to the corruption and collapse of municipal administrations and economies. These pursue a project of good government, sometimes supported by another DA departure, Mmusi Maimane���s One South Africa Movement, but other times articulated according to a more left-wing political program, as is the Makana Citizens Front in the troubled university town of Makhanda. In other cases, these associations are the fallout of ANC factional conflict. These have been forged in the crucible of patronage. In some instances, the new civics and residents��� associations express a sense of rural marginalization and exploitation by urban, national institutions and processes. Their project is to cast out the big parties, establish local control of governments, then often to use these to hoard economic opportunities to the exclusion of non-local outsiders.

In 2016, civics and residents��� associations claimed 99 council seats in 45 municipalities, with a chance of entering coalitions in 12 of these.�� In 2021, they advanced both intensively and extensively, with 80 associations taking 216 council seats in 76 municipalities, pushing 37 of these toward coalitions. Their collective haul was 1.8% of the national vote, a half-point shy of ActionSA���s. But whereas ActionSA was heavily concentrated in Gauteng, with only 12 seats beyond in KwaZulu-Natal, the rural bias of the civics gives them a more dramatic geographical reach, with a presence across the breadth of the country.

An absent but potential giant in this politics of realignment is an independent, nationally-coordinated party of socialism. The trade union federation Cosatu and the Communist Party remain entangled in alliance with the ANC, absorbed in its politics and pitfalls. The breakaway South African Federation of Trade Unions (Saftu), the various cliques, movements, and NGOs of the independent left, remain divided by personalities and strategy. Strong currents of movementism, Leninism, and anarchism generate an ambivalence toward ���bourgeois��� parliamentarism and the state, which has been expressed as abstention or in the most abstract ideologism, where parties have stressed purity and abstract critique, rather than orienting themselves to the task of articulating the concrete problems of poor and working people, and building the broad base needed to win power.

In the event, on November 1, a disparate constellation of eight workers���, socialist, and communist parties won seats across five provinces, but incredibly for a country with such a vibrant history of left-wing militancy, these won just 0.15% of the vote. Leftist organizations and individuals played a prominent role in forming, by my count, six civics that took seats, bringing the grand total to 0.3%.

Coalition politicsNewly minted municipal councils spent the month of November cobbling together coalitions and electing mayors. The ANC was able to formulate agreements with the Patriotic Alliance and a number of smaller parties. In this way, it secured executive office in the metros of eThekwini (Durban) and Nelson Mandela Bay (Gqeberha), together with twenty other local municipalities. In recompense, it lit four Cape municipalities yellow for the Patriotic Alliance. It lifted civics into the mayor���s chair in the Karoo municipalities of Kannaland (Ladismith) and Prince Albert. It gave eDumbe in the north of KwaZulu-Natal to an IFP breakaway, the National Freedom Party.

The ANC was otherwise shunned. The party is toxic to many opposition voters. Its larger opponents, especially the DA and ActionSA, made a show of holding it to account for its corruption and mismanagement of national affairs. The IFP, after concluding an early agreement, faced a revolt from the rank-and-file, then found more love in the arms of other parties. The EFF���s strategy was to disrupt the ANC, constricting its access to municipal patronage, which will loosen its hold over votes in township wards. The intended effect, moreover, is to damage Ramaphosa���s standing in his party, benefitting the EFF���s allies in the anti-Ramaphosa faction, strengthening its position on the way to national elections and parliamentary coalition negotiations in 2024.

The ANC, in result, lost control of the metros of Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni (East Rand), along with almost one-fifth of its pre-election local mayoral offices. The DA lost some ground in its Western Cape stronghold, but it claimed the great cities of Gauteng and established a foothold in five other provinces. The IFP reached out across its northern KwaZulu-Natal heartland, winning an additional 14 municipalities, including with a breakaway in the west at Okhahlamba. The EFF formed its first local executive, in Thembelihle in the Northern Cape. Civics and residents��� associations, outside of coalitions with the ANC, took mayoral control of six municipalities in the Western and Northern Cape, the Free State, and Mpumalanga.

The formal opposition entered the elections with executive control of 39 local municipalities. They concluded the process with 68, including half of the metros, enhancing the impression of change. But the EFF is a scion of the radical nationalist tendency in the ANC. It���s strategy entailed handing municipal power to the white-controlled DA, an outcome which could not feasibly be repeated at the level of national government. It was in fact a move entangled in ANC factional struggles, oriented to facilitating a coalition with it in 2024. When we account for this move, together with existing ANC coalition partners, then a more substantive opposition comes out of this election with 48 municipalities, only nine more than it had before.

The apprehension of change, once again, appears illusory. In the absence of an organized�� alternative around which to realign and reconstitute South Africa���s political regime, what we���re seeing is simply the ANC���s own politics spill out into a coalitional game, within basic parameters of continuity and stasis.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers