Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 114

November 3, 2021

Qu’est-il advenu des accaparements de terres en Afrique?

Oil palm plantation in Sierra Leone. Photo credit: Maja Hitij

Oil palm plantation in Sierra Leone. Photo credit: Maja Hitij Des actes de violence perp��tr��s contre des d��fenseurs des droits fonciers en Ouganda et des manifestants anti-mine en Afrique du Sud. De vastes palmeraies rasant des for��ts au Liberia et sur l’��le de S��o Tom��. Des d��chets industriels provenant de plantations de canne �� sucre qui polluent l’environnement et portent pr��judice aux moyens de subsistance des villageois au Nigeria.

Ce ne sont l�� que quelques manchettes du mois dernier. De tels reportages n���ont cess�� d�����tre diffus��s depuis que la hausse des prix des denr��es alimentaires et du carburant en 2007 et 2008 a men�� �� l���appropriation par des int��r��ts priv��s de terres et de ressources dans le monde entier. L’Afrique constitue le continent le plus vis�� par les acquisitions fonci��res �� grande ��chelle en termes de nombre de transactions effectu��es et de superficie totale concern��e. Au cours des deux derni��res d��cennies, la ru��e mondiale sur les terres africaines a ��t�� provoqu��e par des pr��occupations li��es �� la raret�� des ressources, conjugu��es �� la croyance erron��e que l’Afrique regorgerait de terres �� vides �� ou �� inoccup��es �� souffrant de ce que la Banque mondiale a qualifi�� d����� insuffisances de rendement ��lev��s ��.

Mais c’est l�� que r��side un paradoxe : bien que les investisseurs �� la recherche de terres manifestent un int��r��t constant pour l’Afrique, le continent abrite ��galement la plus grande proportion de ce que certains observateurs ont appel�� des transactions fonci��res �� rat��es �� (au sens ��troit du terme, �� savoir que les n��gociations et les contrats ont ��t�� annul��s). Selon le Land Matrix, entre 2000 et 2020, la moiti�� des transactions fonci��res agricoles transnationales cat��goris��es comme ����rat��es���� ont pris place en Afrique subsaharienne. Une autre ��tude souligne que les investisseurs actifs dans les secteurs agricole, ��nerg��tique, forestier et autres en Afrique sont fr��quemment impliqu��s dans des conflits avec les communaut��s locales, entra��nant ainsi des retards importants dans l���ex��cution de leurs projets.

Dans un nouveau forum de l���African Studies Review intitul�� �� Understanding Land Deals in Limbo in Africa ��, nous creusons ces questions �� travers l���examen de projets fonciers en suspens au S��n��gal, en Tanzanie et en Zambie. S’appuyant sur des ��tudes ethnographiques approfondies, les quatre articles du Forum illustrent que m��me lorsque les projets fonciers sont annul��s, bloqu��s, r��duits, repris par de nouveaux propri��taires, dormants ou sp��culatifs, ils peuvent g��n��rer des cons��quences dommageables, lesquelles passent souvent inaper��ues.

Comment expliquer ces r��sultats impr��vus ? Comment les diff��rentes parties prenantes ��� les ��tats h��tes, les investisseurs ��trangers et nationaux, ainsi que les communaut��s locales – n��gocient-elles l���avenir incertain des projets partiellement r��alis��s? Qui sont les gagnants et les perdants de ces projets en latence ? Ces questions doivent figurer au premier plan des d��bats et d��cisions politiques sur la gouvernance fonci��re, le d��veloppement rural et les transformations agraires en Afrique. Nous soulignons ici trois th��mes cl��s du Forum qui sont porteurs d’enseignements plus larges pour comprendre des dynamiques similaires dans d���autres pays sur le continent.

La premi��re le��on concerne les d��fis que posent le contr��le et la gouvernance des terres. Comme l���illustrent les quatre articles, m��me lorsque les ��tats ont formellement transf��r�� des terres aux investisseurs, ces derniers rencontrent r��guli��rement des difficult��s dans la prise de possession effective de leur assiette fonci��re. Prenons le cas de la Zambie. Comme le montrent nos coll��gues, des investisseurs dans ce pays ont eu du mal �� ma��triser les rouages d���un syst��me foncier complexe et �� r��unir des centaines de titres de propri��t�� diff��rents pour cr��er une vaste exploitation d���un tenant, en vain. Fondamentalement, les terres que les gouvernements allouent aux investisseurs sont souvent d��j�� occup��es par des usagers coutumiers, comme le montrent les cas d�����tude du Forum. Bien s��r, certains investisseurs ont us�� de la force pour d��poss��der les populations locales de leurs terres, mais il s���agit souvent d���un choix impopulaire pour ceux souhaitant pr��server leur image d’entreprises �� responsables ��.

Dans la plupart des pays d’Afrique, o�� les institutions ��tatiques g��rent les acquisitions de terres, les investisseurs ont tout int��r��t �� ��tablir et maintenir des relations cordiales avec les gouvernements h��tes, m��me si cela n��cessite de r��aligner les objectifs de leurs projets sur les priorit��s de ces derniers. Il demeure que les investisseurs risquent de voir l’��tat r��voquer arbitrairement leurs titres de propri��t��, comme cela s���est produit dans de nombreux pays de la r��gion. Cette situation r��sulte souvent de la n��cessit�� pour les ��tats de balancer les imp��ratifs d’accumulation de capital par l’extraction de ressources d���une part avec d���autre part la pr��servation de leur l��gitimit�� politique et de la stabilit�� sociale en zones rurales, o�� une majorit�� de leurs ��lecteurs sont situ��s.

La deuxi��me le��on �� tirer est que les incertitudes entourant les projets fonciers entrav��s d��voilent la complexit�� des jeux politiques locaux et contribuent parfois �� renforcer les in��galit��s sociales existantes. Le Forum souligne comment des n��gociations prolong��es peuvent permettre �� divers groupes, dont des r��sidents locaux, des migrants sans terre et des ��lites domestiques, d’occuper et/ou de vendre des parcelles situ��es �� l���int��rieur des concessions allou��es, limitant ainsi la capacit�� des entreprises �� contr��ler le foncier. Les mouvements locaux de r��sistance, tels que les manifestations publiques et les poursuites judiciaires, peuvent temporairement interrompre les projets fonciers ou forcer les ��tats �� r��viser les contrats conclus, comme le montrent les ��tudes de cas en Tanzanie et au S��n��gal. Mais ces campagnes d���opposition peuvent aussi accentuer les fractures sociales en excluant les femmes, certains groupes ethniques ou religieux et les personnes les plus susceptibles d’��tre d��plac��es. Pour leur part, les investisseurs peuvent tenter de soutirer le consentement d’acteurs influents pour ��viter des d��lais suppl��mentaires et contenir le m��contentement populaire.

La derni��re le��on concerne les limites du capital. Malgr�� les promesses de millions de dollars en investissement et en avantages socio-��conomiques, les investisseurs se lancent souvent sans fonds propres, en particulier les projets �� grande ��chelle partant de z��ro. Dans de nombreux cas, dont ceux discut��s dans notre Forum, les investisseurs sont confront��s �� des difficult��s pour lever les financements suffisants, survivre aux fluctuations des cours mondiaux des mati��res premi��res, g��rer les risques financiers, r��pondre aux attentes des actionnaires et, dans le cas de l’agriculture, s’adapter �� des contraintes ��cologiques de production que ni l���argent ou la technologie ne peuvent enti��rement r��soudre. De nombreux investisseurs ne poss��dent pas non plus d’exp��rience en agriculture tropicale. Les acquisitions fonci��res �� grande ��chelle en Afrique ��� auparavant consid��r��es comme un moyen �� s��r �� pour les investisseurs du Nord de se pr��munir contre l’inflation et les p��nuries alimentaires et ��nerg��tiques – n’ont gu��re fourni de solutions ais��es aux crises internes du capitalisme.

En bref, les interactions complexes entre les modes de gouvernance fonci��re, les dynamiques politiques locales et les contradictions propres au capitalisme peuvent pousser les projets fonciers dans des directions inattendues. N��anmoins, les projets inachev��s peuvent consid��rablement limiter l’acc��s �� la terre et les moyens de subsistance des populations, entretenir des craintes de d��possession et intensifier les conflits locaux. Dans certains cas, ces retards peuvent conduire �� des processus d’arbitrage international entre les ��tats et les investisseurs ��trangers, lesquels servent rarement les int��r��ts des communaut��s rurales.

Alors que la pand��mie de COVID-19 se poursuit, les entreprises con��oivent de nouvelles tactiques pour expulser les fermiers de leurs terres, tandis que divers gouvernements acc��l��rent les r��formes l��gislatives pour faciliter les acquisitions fonci��res. Pour que le d��veloppement agricole s���av��re r��ellement durable et ��quitable, les d��cideurs politiques doivent tenir compte des co��ts invisibles que les accaparements de terres, en cours ou inachev��s, imposent aux diverses communaut��s rurales concern��es.

Youjin Chung est professeure adjointe en durabilit�� et ��quit�� �� l’Universit�� de Californie �� Berkeley.

Marie Gagn�� est chercheuse postdoctorale en science politique �� l’Universit�� Concordia.

November 2, 2021

The second Scramble for Africa

Image credit Regina Hart via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Image credit Regina Hart via Flickr CC BY 2.0. The International Union for Conservation of Nature Congress in September 2021 was a key platform for the elaboration of the European Union’s NaturAfrica plan, which aims to build on the contentious conservancy model of conservation in 31 African states. Mordecai Ogada reflects on his experiences at the congress, and whether Africa’s “… heritage salesmen and saleswomen are facilitating the second scramble for Africa delivered in the guise of conservation.” This post is republished as part of a partnership with The Elephant. It is curated by Wangui Kimari.

Dear natives, do you know any conservationist who was in Marseille, France, in the last couple of weeks? If you���re a conscious African citizen, you need to ask them exactly what they were doing there and what they discussed at the IUCN World Conservation Congress. Personally, I was there as part of a group organizing resistance against the relentless advance of colonialism throughout the global South under the guise of conservation. Like most conservation conferences today, this meeting was full of backslapping and self-congratulatory nonsense exchanged between celebrities, politicians and business people. This is the ultimate irony because this is the group of people most responsible for the consumption patterns that have landed the world in the climate predicament we���re in today.

They created the most effective filter to keep out people from the global South (where most biodiversity exists), the students who may be learning new scientific lessons on conservation, and the independent-minded practitioners who would be there to share their views, rather than show their faces, flaunt their status and prostitute their credentials for the benefit of their benefactors. This filter was the registration fee. The cheapest rate was the ���special members fee��� which was 780 Euros.

While most of the Kenyan conservationists are now back from Marseille gushing about the beauty of the South of France (which is true), I come back home a worried man, even more perturbed than I was before about the march of colonialism under the guise of conservation. For any African proud of their heritage, this worry is heightened by the unending queue of Home Guards and Uncle Toms lining up to sing for the crumbs and leftovers from Massa���s table: the small jobs, big cars and trips to conferences where the only thing prominent about them is their dark complexion and not the intellectual content of their contributions. These heritage salesmen and saleswomen give themselves all sorts of fancy titles, but their brains are of no consequence to the European colonizers. They are as much props as the obviously (physically, mentally, both?) uncomfortable woman unfortunate (or foolish?) enough to have her ridiculous image carrying a pangolin used on the blueprint for the new Scramble for Africa.

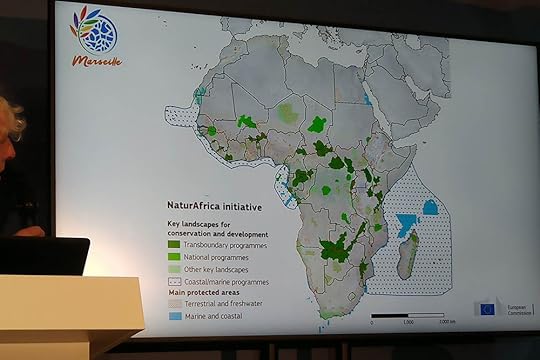

The biggest thing out of Marseille was the European Union���s grand plan to capture Africa���s natural heritage through a program called NaturAfrica. Since they know that they have selected partners in Africa to whom prostitution comes easily, they drowned the announcement in noise about doubling of funding for conservation on Twitter.

EU���s Philippe Mayaux presenting the NaturAfrica initiative

EU���s Philippe Mayaux presenting the NaturAfrica initiativeIn the first photo above, you can see the EU���s Philippe Mayaux presenting the audacious grand plan. He expressly stated that they are going to use the ���Northern Rangelands Trust model��� which has served them well thus far. I���ve been saying for the last 5 years that NRT is a model for colonialism and some invertebrates here have been breaking wind in consternation at my disrespect for their cult. The financiers have now said that it is a pilot for their planned acquisition of Africa���s natural heritage. What say you now? Who���s in charge of the plantation? Do the na��ve majority now understand the violence in northern Kenya? Do the na��ve majority now understand why foreign special forces are training armed personnel (outside our state security organs) to guard the so-called conservancies?

Following this extravagant declaration by Mayaux, the CEO of the NRT, Tom Lalampaa, barely containing his joy, took to the podium and gushed that ���NaturAfrica will be welcomed by all Africans.��� Only the irrational excitement brought on by Massa���s praises can cause a mere NGO director to purport to speak for the 1.3 billion inhabitants of the world���s second largest continent. Kwenda huko! Get out of here! We can see through the scheme!

Tom Lalampaa, CEO of the NRT

Tom Lalampaa, CEO of the NRTOn the map presented by Mayeux, youcan see the takeover plan (the dark green areas); Tsavo, Amboseli and Mkomazi in northern Tanzania is a colony of the WWF ���Unganisha��� program. To the west is The Nature Conservancy colony consisting of the Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association in Kenya, and the northern Tanzania Rangelands Initiative. The rest are the NRT colony (including the Rift Valley, which is clearly marked) and the oil fields in northern Kenya. East Africa���s entire Indian Ocean seascape is marked for acquisition; spare a thought for the island nations therein, because they have been swallowed whole. The plan has already been implemented around the Seychelles and documented.

I will repeat this as often as necessary: the biggest threat to the rights and sovereignty of African peoples in the 21st century is not military conflict, terrorism, disease, hunger, etc. It is organizations and governments that seek to dominate us through conservation. They will bring their expatriates, their militaries, and their policies. If you look at the map, the relatively ���free��� countries���like Nigeria, Congo, Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, etc.���are those where international conservation NGOs haven���t been able to get a foothold. Here in Kenya, our state agency, the Kenya Wildlife Services, is busy counting animals, not knowing that it is well on the way to becoming an irrelevant spectator in our conservation arena. If you think this is far-fetched, ask someone there why there are radioactive materials dumped by the Naro Moru gate to Mt. Kenya National Park. Or why the Kenya Forest Service is standing by without any policy position while the Rhino Ark goes on about fencing Mt. Kenya Forest, a UNESCO world heritage site.

Has anyone asked the EU why this grand plan isn���t global, but only focused on Africa? Are there no conservation concerns in Europe, Asia, or the Americas? Ours is the land of opportunity and this is why they want it. The funding will facilitate immigration and pay to employ the expatriates that will look after their interests in our homelands. Their militias will keep us out of our lands which they need for ���carbon credits��� so their industries can continue to produce and pollute unabated. Lastly, they need our land for export dumping of their household rubbish, toxic waste, and, most of all, radioactive material. This is obviously a continental initiative, but addressing my compatriots, can you now see what I have been talking about for years, even as the European colonists tell Maasais, Samburus and other pastoralist communities that they shouldn���t listen to me because I am Luo? Can you now see how miniscule that school of thought is, how easily your attention has been diverted to discussing irrelevant minutiae in the face of the scale of their grand scheme?

As I said in the beginning, my mission, together with colleagues in Survival International, is the de-colonization of conservation in Africa and the global South. The routine violation of indigenous people���s rights, and the violence constantly meted against them, is the most visible symptom that brought this problem to our notice. But, we must understand that the violence isn���t just for sport, as much as these organizations revel in it. Like 18th and 19th century colonialism, it is a commercial venture where political interests follow in its wake because it is too big to remain private. When Leopold���s Belgians massacred people in Congo, it wasn���t just for sport (although at some point it looked like that)���they were there to collect rubber and other resources. The conservation militias don���t just kill indigenous Africans for sport. They are here to protect colonies on behalf of capital interests. It is not about the wildlife���that is just the window dressing. After all, the people and the wildlife were here for thousands of years before their militias came.

This is why we cannot afford to give up. It���s not just about biodiversity. It���s also about our identity, our resources and our children. This is why we must fight intellectually to develop our own conservation philosophy and reject this violent and elitist Tarzanesque Western model. In order to restore the rights of indigenous peoples, we must tackle the reason why they are being oppressed, tortured and sometimes killed. It is commerce. Conservation is just the attire in which it is clothed.

Find an African who was in Marseille and ask him or her what they were doing there. If they cannot demonstrate that they spoke against this colonial project, they had better show you a lot of photos of them shopping and spending a wonderful holiday in the south of France. If they can do neither, then be sure they were in France selling or facilitating the sale of our heritage to corporate pirates.

November 1, 2021

A journey to Harar

Still from Faya Dayi.

Still from Faya Dayi. A Harari folktale relates the story of Azurkherlaini, an elderly emir who speaks to God in a dream as his death looms near. To quell his fears, God commands him to seek out Maoul Hayat���the water of eternal life���and he embarks on the journey with two other emirs, Khedir and Elias. Khedir, who finds the water first, is transformed into daylight after a drink, while Elias, the next to arrive, turns into the darkness of night when he sips on the muddy remnants. Azurkherlaini arrives too late, the water having dried up. God instead grows khat in its place, telling him that ���whoever eats khat will always remember you.���

More than simply offering a narrative structure, the story of Azurkherlaini weaves together many of the themes in Mexican-Ethiopian director Jessica Beshir���s stunning debut documentary feature film, Faya Dayi (2021). It interlaces the landscapes and ecology of eastern Ethiopia and the Harar plateau in particular, the dreams and disappointments of its inhabitants, the role of history and collective memory, the centrality of Islamic religiosity, and, of course, khat. Like coffee, the leafy stimulant plant is native to the Horn of Africa and has a long history of use in social rituals as well as in Sufi Muslim spiritual practice.

A scene in Faya Dayi echoes Azurkherlaini, bringing the histories of the two stimulants together as a group of Oromo farmers cultivating khat drink coffee under the shade of a tree. ���Our coffee was beautiful,��� a man tells the others, reminiscing over how he and his father once grew coffee, ���but it needed a lot of rain. We replaced it with khat.��� As they return to laboring in the khat fields, we hear the title of the documentary as an expression within an Afaan Oromo work song, its rhythms synchronizing their movements: faya dayi, give birth to health.

Khat, which requires less water and attention than coffee, is Ethiopia���s most lucrative cash crop. The walled, ancient city of Harar and its adjacent areas of Oromia, the focus of Beshir���s directorial gaze, constitute the largest khat-producing and exporting area in the world. Beshir, however, chooses to introduce the viewer to khat as more than an increasingly important export product in a capitalist economy; she finds ways to capture khat���s roles and meanings in everyday Harari life. Our first glimpse of khat come with the slow-moving, black and white imagery that characterizes the film: an incense smoke-filled room, partial views of men in traditional sarongs, tasbih prayer beads, kufi skull caps, and the sounds of Quran recitation, prayer, the buzzing of house flies, the pounding of a mortar and pestle. This is Harar, the city of Sufi saints and Islamic learning, the thoroughfare bridging the Ethiopian highlands and the Somali coast.

Faya Dayi is not your usual documentary. There are no talking heads informing us about the political economy of khat, no interviews with its cultivators, exporters, sellers, or consumers. Instead, what Beshir offers is an immersive experience that uses hazy, dreamlike sounds and images to evoke and mirror the experience of chewing khat and its addictive high known in the region as merkhana (or mirqaan). Individual stories are told in non-linear fragments: teenage boys discussing how to migrate to Europe, a group of women preparing for a wedding, an elderly man singing of heartbreak, a lonely wife lamenting over the loss of her husband to merkhana. These narratives come in and out of focus, winding through Faya Dayi and almost mimicking the labyrinthine geography of historic Harar Jugol and its narrow, maze-like alleys. The many fragments combine to piece together a deeply human, affective picture of the inner lives of Harar���s residents, bound as they are to khat���s pleasures and discontents. Harar, the center of khat���s production and distribution in the Horn of Africa���and, indeed, khat itself���are the film���s most consistent and enduring characters.

Time in Faya Dayi is elusive, but the lifecycle of khat offers some semblance of temporal structure. Khat leaves begin to wither and lose potency within 48 hours of harvesting; trucks deliver fresh khat to other Ethiopian cities and across the border to export markets in Somaliland and Djibouti. The film slows down the breakneck, controlled chaos of the khat industry, with close scenes of farmers harvesting the plant; of warehouse laborers sifting through and bundling the leaves; of truck drivers loading up thousands of kilos of product and distributing the bundles to khat sellers in the market. We see glimpses of its consequences, too. One scene shows a teenage boy starting a job in one of the khat warehouses, replacing his late father as the family���s breadwinner; a fellow worker urges him to continue attending school during the day. The immediate scenes that follow include a khat truck that has run off the road in a serious accident, silently gesturing toward what may have happened to him not long after.

Apart from the folktale of Azurkherlaini, which is interspersed throughout the documentary and completed towards the end of the film, the personal narrative that receives the fullest treatment is that of Mohammed, a teenage boy we see in the khat fields early on but more often delivering khat and tobacco to neighbors in the city. We learn that his mother has left the family and migrated elsewhere, presumably across the Mediterranean or Red Sea, and that his father is abusive and addicted to khat. Mohammed���s father���a younger man whose solitary chews involve listening to pop music on his phone when he is not barking insults at his son or cursing his absent wife���represents a modern iteration of khat use, in contrast to the older men of faith we see chewing as a part of communal religious practice. The merkhana that was once a mode of achieving spiritual ecstasy and closeness to God, ritualized in its use like incense and menzuma chants and praise songs, has been divorced from traditional Sufi Muslim worship in our present.

What emerges in tandem with khat���s rise as a cash crop in Ethiopia is complete dependency: biopsychosocial and economic. In a context of high unemployment, the khat industry offers one of the very few avenues for meaningful work in eastern Ethiopia, yet it is also unemployment���and disillusion with life in Ethiopia more generally���which fuels what is fast becoming an addiction crisis. For Mohammed and many other youths, the only future they see for themselves is abroad, and they are therefore willing to wager their lives to make the dangerous journey to and across the Mediterranean. This palpable sense of hopelessness and despair runs against a feeling of cautious optimism that is rooted in the Islamic belief in the power of the divine to change one���s circumstances, a lesson embedded in the story of Azurkherlaini. One man is shown praying for God to ���make our dreams come true,��� while another cries, ���the Creator fulfils . . . the times are cruel, may He help us.���

The times he refers to, as we see later, are those of the ongoing, violent state suppression of Oromo political expression, which only intensified after a brief moment of democratic opening brought on by the 2014���2016 Oromo protests. In one scene, a woman describes the mass detentions and their impact on her family as her friend comforts her with the words that ���everything is in God���s hands.��� In another scene, a young man involved in the movement says that as Oromos, ���our struggle is not new, our grandparents and great grandparents went through it.��� This moment recalls a khat farmer���s earlier remark that ���every regime has kept us from working our own fertile land,��� reminding viewers that much of Ethiopia���s political challenges are rooted in its histories of land, labor, and ethnic domination.

Faya Dayi is an impressive film, a kaleidoscopic look at everyday life in eastern Ethiopia through the lens of khat and Oromo Muslim subjectivity. Its genre-defying, experimental qualities raise the question of the extent to which scripted and fictional elements were used; similarly, the lack of interviews and overarching narrative voice can make it somewhat difficult to follow or learn more about its subject matter. These concerns cease, however, when one approaches the film as an experience like merkhana���allowing Jessica Beshir to immerse you in the Sufi Muslim world of Harar.

Who is the Black man?

Still from "Malcolm X: Struggle for Freedom" (1967).

Still from "Malcolm X: Struggle for Freedom" (1967). Lebert Bethune is a poet, educator, author and filmmaker who became involved in the pan-African expat circles during the 1960s. Born in Kingston, Jamaica, he migrated to the US as a teenager and graduated from NYU. He then traveled to Europe where he studied and worked for a number of years. In Paris during the early 1960s, Bethune became involved in the Black expatriate community. He collaborated with photographer John Taylor, combining his writing with Taylor���s cinematography to create two films, Jojolo (1966) and Malcolm X: Struggle for Freedom (1967). Check out our explainer���edited by myself���about Bethune���s life and artistry and watch the full conversation by Matthew J. Smith with Bethune as part of the African Film Festival in New York.

October 31, 2021

The Lord’s Chief Justice

President Cyril Ramaphosa with Deputy President David Mabuza and Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng at the swearing-in ceremony of the new National Executive at the Tuynhuis, in Cape Town. Image credit GCIS via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

President Cyril Ramaphosa with Deputy President David Mabuza and Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng at the swearing-in ceremony of the new National Executive at the Tuynhuis, in Cape Town. Image credit GCIS via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. Mogoeng Mogoeng, South Africa���s erstwhile chief justice, retired from the Constitutional Court on October 11. His appointment by former president Jacob Zuma in 2011 was highly controversial. It followed an unsuccessful attempt by Zuma to extend the term of office of Sandile Ngcobo, who was chief justice then. At the time, Mogoeng had only been a judge of South Africa���s highest court for two years. Before that he had been a puisne judge; the head of the High Court in Mahikeng, a small town in the northern part of the country. He had no constitutional law experience, had not appeared as an advocate before the appellate courts, and had not published any academic papers (when asked about the lack of published papers, he responded that he had ���no passion��� for writing, a strange remark by a judge, whose job is to write). In sum, he was an unlikely candidate for appointment. Naturally, Zuma appointed him.

When Zuma nominated Mogoeng as chief justice, ahead of the more celebrated and experienced deputy chief justice, Dikgang Moseneke, the legal establishment, non-governmental organizations, trade unions and political parties vocally opposed his appointment to varying degrees. Of course, with the nomination came greater scrutiny. As legal professional bodies pored over his record and read his judgments, a grim picture began to emerge. In fact, many wondered how he had been appointed to the Constitutional Court in the first place.

Objecting to his nomination as chief justice, South Africa���s largest trade union federation, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), highlighted several judgments which, in its view, rendered Mogoeng unsuitable for the post. COSATU took issue with his approach to adjudication in gender-based violence cases. In one case concerning rape, Mogoeng had reduced a 10-year prison term to five years, reasoning that because the victim had been in a long-term relationship with the rapist (���virtually husband and wife��� in his own words), the situation had to be distinguished from a ���rape of one stranger by another.��� He also said that because the victim���s relationship had not been abusive ���the assault ��� was not serious.��� COSATU remarked that Mogoeng���s attitude displayed ���general insensitivity to gender-based violence,��� that he had trivialized rape ���and the understanding of what constitutes consent.��� In another case, Mogoeng reduced a two-year sentence for assault to a fine, where the accused tied a woman to the bumper of his car and dragged her for about 50 meters. Mogoeng found, among other things, that the woman had provoked the accused and that he had pleaded guilty to the charge, which demonstrated his remorse. COSATU referred to at least three other cases where Mogoeng treated the perpetrators of (mostly sexual) violence against women leniently, in each case expressing worrying views about gender and sexual ethics.

His nomination to South Africa���s highest judicial office therefore baffled everyone. Even after he had been appointed to the Constitutional Court, Mogoeng infamously dissented from a portion of the court���s judgment without providing reasons. The case concerned a defamation claim by the deputy headmaster of a well-known high school against three boys who photoshopped a picture depicting him and the headmaster ���sitting next to each other in sexually suggestive and intimate circumstances.��� The court had found that it was not an actionable injury in law ���to call or depict someone as gay������that it was not defamatory to do so regardless of whether or not the person disliked or disapproved of such a depiction. Mogoeng disagreed without providing reasons. Even when probed at his public nomination interview for his reasons, he failed to answer, saying only that in hindsight he should have explained his dissent. For Section 27, a Johannesburg-based NGO, his dissent coupled with the fact that he was a lay preacher at a church known for its anti-gay stance, Mogoeng posed a danger to the rights of LGBTQI people. He rubbished claims that he was homophobic, saying that his church���s position on gay marriage was ���not something peculiar to it��� and that it was ���based purely on the Biblical injunction that a man should marry a woman and that there shall be a husband and a wife.���

As expected, after two days of a gruelling public interview, Mogoeng was recommended as the country���s chief justice with his critics still unconvinced that he was the man to lead the largely progressive court. In the course of his 10-year term at the helm of the judiciary, Mogoeng is seen by many as having proven his critics wrong. Appointed at the start of Jacob Zuma���s turbulent 9-year presidency, Mogoeng steered the courts through a difficult period in South Africa���s history. One moment in particular stands out.

In 2015, former Sudanese president Omar Al Bashir attended an African Union summit in Johannesburg. Before his arrival the International Criminal Court (ICC) had served South Africa with a request to arrest and surrender Al Bashir to the court, were he to enter the country, so that he may stand trial for his international crimes. The South African government took no steps to arrest and surrender Al Bashir once he had arrived in the country and on the day before he was due to depart, the Southern African Litigation Centre made an urgent court application to have the government���s failure to arrest Al Bashir declared unconstitutional. The government asked for a postponement to prepare its court papers and the court granted the postponement to the next day on the condition that Al Bashir would not be allowed to leave the country. On the day the case was heard, the government���s lawyers assured the court that Al Bashir was still in the country. After a full day of argument, the court issued an order declaring the government���s conduct unconstitutional and directing that Al Bashir be arrested and surrendered to the ICC. The government���s lawyers, almost immediately, stood before the court and reported that Al Bashir had left the country, some hours earlier, rendering the order obsolete.

What followed in the weeks after the incident was nothing short of an onslaught. Politicians accused the court of playing politics and of overreaching into areas it was not competent in. These attacks came from senior leaders of the ruling African National Congress. In response, Mogoeng took the bull by its horns and marshaled the country���s senior judges into a meeting after which they appeared at a press briefing to denounce the attacks on judges and to request a meeting with Zuma to discuss the damage wrought by the public attacks. It was a tense moment in the life of the South African judiciary, perhaps surpassed only by Zuma���s own arrest and the violent riots it precipitated in July this year. Mogoeng was praised, rightly, for his courageous stance and willingness to stick it. Perhaps his critics were wrong. Or were they?

The Al Bashir moment was soon followed by Mogoeng���s historic Nkandla judgment, written for a unanimous court, in which he found Zuma to have broken his oath of office and ordering him to pay back millions to the state for personal benefits accrued to him, following a report issued by the public protector (an ombudsman of sorts) to the same effect. That episode also garnered praise for Mogoeng. But his subsequent conduct suggests that he may have indeed been overcome by his colleagues and that the outcome in that case was not devised by him. Written almost as a sermon, the Nkandla judgment drew comparisons between David and Goliath on the one hand and the public protector and Zuma on the other. It described corruption and maladministration in almost identical terms as The Serpent whose ���ugly head of impunity��� ought to be chopped off its ���stiffened neck��� by the ���mighty sword��� wielded by the public protector, our biblical David. In many ways, Mogoeng saw corruption as a repudiation of his Christian ethics, a kind of moral stain that had to be removed by all means.

His religious fervor for accountability did not extend beyond issues of corruption. Indeed, in a subsequent case dealing with whether parliament had breached the constitution by failing to make rules for the impeachment of the president, Mogoeng penned an angry dissent accusing his colleagues of ���textbook judicial overreach.��� Mogoeng caused a national kerfuffle when as Justice Chris Jafta was delivering the judgment, he demanded (unusually) that Jafta read his dissent in full, on national television. He continued to adopt a contrarian stance to his colleagues as he reached the twilight of his tenure, often willing to overlook the provisions of the law to reach a desired outcome. To be frank, as a judge, Mogoeng was not much to write home about.

People often describe Mogoeng as a conservative. Not many interpret that statement in the same way that Americans perhaps may. When South Africans refer to a judge or a lawyer as ���conservative��� it is often in reference to the lawyer���s approach to legal method; their preferred interpretive theory for example. Judges for whom legislative text is primary in legal interpretation are often branded in this way, as opposed to judges who prefer to look beyond the text to discern, and in some cases divine, the meaning of laws. When used in reference to Mogoeng, the classical understanding of what it means to be a conservative comes to mind. For he was by no means a conservative judge. In many cases, Mogoeng often appealed to the values underlying laws even where those values, in the process of interpretation, yielded results directly in conflict with the explicit wording of laws.

In a challenge by president Cyril Ramaphosa to a public protector report in which he was alleged to have engaged in money laundering during his fundraising campaign for the ANC presidency, Mogoeng went as far as saying it didn���t matter that, when deciding whether or not a reasonable suspicion of money laundering by Ramaphosa had been established, the public protector referred to the wrong statute���which did not deal with the offence at all���her job was merely to alert the relevant authorities. She had directed the prosecution service to initiate an investigation into the money laundering claim and to prosecute Ramaphosa. How she could establish the probable existence of an offense the elements of which she did not know remains a mystery.

In an earlier case, Mogoeng had come to the defense of Busisiwe Mkhebane, the beleaguered public protector who took over from anti-corruption star Thuli Madonsela, and has, by my estimation, lost more cases than she has won. There, she conducted an investigation into whether a late-apartheid, billion rand loan advanced by the central bank to a financially distressed bank had been concluded illegally. In the course of her investigation, the public protector engaged in conduct that can only be politely described as shady. The loan, otherwise referred to as a ���lifeboat,��� had been investigated on at least three previous occasions before the public protector took it up. Each time, it was found to have been unlawful and the government had been asked to recoup the cash. It did not do so. In her report, Mkhwebane found the government���s inaction to have been improper, ordered that it recoup the loan, and stunningly, directed the South African parliament to amend the country���s constitution to change the central bank���s main objective and to alter its relationship with its treasury minister.

The central bank challenged the report and won. It also asked the court to order Mkhwebane to pay the costs of the litigation out of her own pocket as a mark of displeasure over her conduct. The court obliged, finding that she had failed to disclose meetings she had had with the country���s spy agency and the office of then-president Zuma; had not kept records or transcripts of those meetings; had engaged in unilateral discussions about the investigation without the bank���s input; and that she had been less than frugal with the truth. On appeal, Mogoeng was willing to overlook Mkhebane���s actions, which he referred to as ���minor and harmless infractions��� (the rest of the court found them to have been ���egregious������including a ���number of falsehoods���), in order to deal with the real issue: the lifeboat. Mogoeng lamented that ���the brightly highlighted apparent corruption, fraud, illegality or impropriety involving the ��� bailout of Bankorp [the financially distressed bank] ��� has virtually disappeared,��� even going as far as accusing the central bank of being ���a vindictive litigant that yearns for untouchability.���. The contrast between the judges��� views of the matter could not be more stark. For Mogoeng, legal niceties, however pronounced, could not stand in the way of taking on Goliath and his legion of minions, those pesky ���economic markets.��� For Mogoeng, where the law was an obstacle to achieving a particular result, an appeal to the open-ended and often vague values underlying legal texts was all that was necessary to dispose of it.

Mogoeng���s brand of conservatism is conservatism in the true sense: an earnest commitment to tradition, authority and religion. In cases where these values were implicated, Mogoeng would feature prominently, often waiting until his colleagues had exhausted their questions before intervening to interrogate counsel. Sometimes his questioning tended to be somewhat tangential, betraying a lack of preparedness and perhaps a bit too much passion. When one reads closely those cases which did not make the headlines, the run-of-the-mill cases, there appears to be a discernable pattern.

On questions of the exercise of executive authority he preferred to side with the executive, often appearing exasperated by his colleagues��� otherwise interventionist attitude over the control of executive power. In a tort claim for damages following an unlawful arrest, Mogoeng dissented from a majority opinion attributing liability to the minister of police for the claimant���s court-ordered detention on remand. The court had found that the arresting officer was aware that the arrest was unlawful, that remand proceedings were almost mechanical with the result that the claimant would in all likelihood be remanded for further detention���the unlawful arrest notwithstanding���and that she had reconciled herself with that possibility and therefore could not escape liability for the continued unlawful detention.

Mogoeng disagreed. The further detention could not be attributed to the minister. Instead, the mere fact that the claimant was brought to court after the arrest was an independent new event which broke the causal chain of events; the police���s liability had been discharged, the courts were responsible for the further detention, not the minister. It was a stunning judgment, turning established tort law principles on their heads but predictably did not raise eyebrows in the media. It just wasn���t sexy enough.

Another area where Mogoeng was prominent was in cases involving family life, from marriage to corporal punishment by parents. Mogoeng took any and all opportunities to write on these areas. One of his most recent judgments was in a constitutional challenge to a statute that did not allow unmarried fathers to register the births of their children in the absence of their mothers (in this case the mother was an undocumented foreign national, and the father a South African citizen). The court ultimately found that the statute was unfairly discriminatory on the basis of marital status. Mogoeng took the opportunity to extol the virtues and societal value of marriage over all other forms of familial relation. Finding no unfair discrimination, Mogoeng defended the law, arguing that marriage was central to its objectives and pointing out that allowing unmarried fathers to register their children���s births would lead to random men claiming babies in hospitals in order to traffic them on the black market. To the majority���s complaint that such an approach was prejudicial against unmarried fathers���because married men can also be human traffickers���Mogoeng had a simple answer: the father would simply have to produce a marriage certificate linking him to the mother (no consideration appears to have been given to the very real prospect of falsified marriage certificates, apparently).

Mogoeng���s penchant for conspiracies had only emerged later in his tenure as chief justice, but was very apparent in his public life. In December 2020, when South Africa had just entered its deadly second wave of the pandemic, Mogoeng gave a speech at a government function where, as one does, he led the faithful in prayer. He called on God to destroy any ���vaccine that is being manufactured to advance a satanic agenda, the mark of the beast, 666 ��� for the purpose of corrupting the DNA of people.���

A furore followed, with several sectors of society repudiating his views. Naturally, he doubled down, adding at a press conference that he did not think vaccines should ever be mandatory. It didn���t seem like the speech would have much of an impact at the time, given that South Africa���s vaccination program was not even off the ground. But the slow uptake of vaccines by especially vulnerable groups has shown that it may have been instrumental in encouraging vaccine hesitancy.

Mogoeng of course defended his views on the basis of religious expression. He reiterated that he wasn���t saying anything about the efficacy of the vaccines, he wasn���t a scientist, but was merely doing his part ���as a prayer warrior.��� His Christian faith was never a private matter, that���s for sure. He famously knelt to pray during televised parliamentary proceedings over which he presided, and gifted Ramaphosa with a Bible at his inauguration as South Africa���s president.

In the earlier years of his tenure, following his tumultuous nomination, his religious life had been somewhat subdued. But towards the end it was all anyone could talk about. Mogoeng drew the ire of all manner of people in June 2020 following his remarks at a webinar hosted by The Jerusalem Post, where he expressed concern about South Africa���s foreign policy on Israel and Palestine, viewing it as essentially unbiblical, and expressing an almost unqualified love of and for Israel. Mogoeng���s comments were made a day before South Africa���s government was set to raise its objections to Israel���s planned annexation of the West Bank and the Jordan Valley at the UN Security Council, suggesting that the organizers of the webinar had intended for him to publicly contradict his government���s actions. Faced with judicial misconduct complaints following those remarks, he again raised the religious expression defence. The judicial conduct committee found him guilty of breaching his office���s code of conduct and ordered him to apologize. He refused and appealed the decision.

In May, Mogoeng opted to take an extended leave of absence from office which conveniently coincided with his retirement, leaving in his wake a judiciary in ruins. Reflecting on his time in office, former member of parliament Koos van der Merwe (for the Inkatha Freedom Party), who is famous for having asked Mogoeng whether God wanted him to be chief justice (you can guess the answer), said it became clear to him ���that [Mogoeng���s] true ideal was to become the president of South Africa.��� Perhaps Van der Merwe is correct. Mogoeng appeared to have grown frustrated with the constraints of judicial office and seemed to have fully embraced populist politics. In fact, in 2018 he was reported to have sat in less than half of the cases heard by the Constitutional Court that year, spending his time travelling internationally and delivering talks instead (and raking up millions of rands in taxpayer bills in the process). He appeared publicly with increasing frequency and was not at all afraid to court controversy.

His Nelson Mandela Lecture in 2019 would seem to many to have been the springboard for his new public career as chief opinionista, but in fact, it was a little known TEDxTalk delivered in Mahikeng in September 2019 that signaled a change in his persona. In it, he reminisced about a time ���when rocks were soft��� and bemoaned the state of South African society, which had fallen very far off from the days when ���obedience to lawful authority was the order of the day.��� Mogoeng rhetorically asked his audience how to fix it: ���do we think that we should return to basics ��� or do we think that perhaps something more sophisticated can be gathered from books that will change us into the kind of society we need to be? I think we need to go back to basics������ He gave an impassioned speech rich with anecdotes of his simple village upbringing which was the pinnacle of the society he wanted to see, going as far as questioning whether South Africa���s vast yet somehow inadequate social security system was ���sustainable.��� He wondered how many more jobs could we create with those billions of rands we spend on social assistance every month? If you are at all familiar with South African politics, you will know that these are your everyman���s talking points. The ground is fertile for such politics.

Mogoeng espouses all of the characteristics of a modern day conservative. Traditional values like the primacy of marriage and family in society; obedience to and veneration of authority; a Christian ethic of politics��� a disgust of corruption and greed; distrust of experts and intellectuals; preferring tradition over reason; and above all, an almost civilizing commitment to religion. His quiet departure from office surprised everyone who had known him to be quite boisterous and pompous���an example of his eccentricities being his annual parade of judges in robes at the Constitutional Court while he delivers his ���Judiciary Annual Report,��� a sort of ���State of the Nation��� address but for judges���leaving them to wonder why he would choose to go out so sad.

Had the controversy of the preceding months finally taken its toll or was something more sinister afoot? His actions towards the end pointed to something on the horizon. While speculation over the reasons for his early exit mounted, he quietly emerged from his withdrawal from public life in late September. He did not go on webinars or radio shows or the like. He went back to his flock; the faithful. Ever so fiery, he stood on pulpits across the country, delivering sermons so overflowing with moral indignation that they would put St. Paul the Apostle to shame.

On October 31, the South African weekly Sunday Times reported that Mogoeng had been approached by an organization called the Independent Citizens Movement, a grouping of pastors and professionals, to stand as its presidential candidate in the 2024 national elections. Mogoeng, characteristically responded that he would only stand for public office ���if God wants him to.��� Indeed, President Mogoeng is here; delivered by the Lord himself. The chief justice hath become his true self. We have reached Damascus.

October 29, 2021

The lives of refugees

Dadaab (Image: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, Via Flickr CC).

Dadaab (Image: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, Via Flickr CC). For almost a decade, Kenya has consistently threatened the closure of Dadaab refugee camp in order to aggressively attain favorable political-economic arrangements from Western governments and international funding agencies. The camp is the third largest refugee camp in the world and resembles a town. Nearly 224,000 registered refugees are housed there. Usually terrorist threats in the camp are offered as a (rarely proven) motivator for the threatened closure, but this time it’s the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) ruling in favor of Somalia, and against Kenya, in a maritime case, that has prompted this recent “playing politics” with Dadaab lives. This post is republished as part of a partnership with The Elephant. It is curated by Wangui Kimari.

For several years now, Kenya has been demanding that the UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, close the expansive Dadaab refugee complex in north-eastern Kenya, citing ���national security threats���. Kenya has argued, without providing sufficient proof, that Dadaab, currently home to a population of 218,000 registered refugees who are mostly from Somalia, provides a ���safe haven��� and a recruitment ground for al-Shabaab, the al-Qaeda affiliate in Somalia that constantly carries out attacks inside Kenya.�� Threats to shut down have escalated each time the group has carried out attacks inside Kenya, such as following the Westgate Mall attack in 2013 and the Garissa University attack in 2015.

However, unlike previous calls, the latest call to close Dadaab that came in March 2021, was not triggered by any major security lapse but, rather, was politically motivated. It came at a time of strained relations between Kenya and Somalia. Kakuma refugee camp in Turkana County in north-western Kenya, is mostly home to South Sudanese refugees but also hosts a significant number of Somali refugees. Kakuma has not been included in previous calls for closure but now finds itself targeted for political expediency���to show that the process of closing the camps is above board and targets all refugees in Kenya and not only those from Somalia.

That the call is politically motivated can be deduced from the agreement reached between the UNHCR and the Kenyan government last April where alternative arrangements are foreseen that will enable refugees from the East African Community (EAC) to stay. This means that the South Sudanese will be able to remain while the Somali must leave.

Accusing refugees of being a security threat and Dadaab the operational base from which the al-Shabaab launches its attacks inside Kenya is not based on any evidence. Or if there is any concrete evidence, the Kenyan government has not provided it.

Some observers accuse Kenyan leaders of scapegoating refugees even though it is the Kenyan government that has failed to come up with an effective and workable national security system. The government has also over the years failed to win over and build trust with its Muslim communities. Its counterterrorism campaign has been abusive, indiscriminately targeting and persecuting the Muslim population. Al-Shabab has used the anti-Muslim sentiment to whip up support inside Kenya.

Moreover, if indeed Dadaab is the problem, it is Kenya as the host nation, and not the UNHCR, that oversees security in the three camps that make up the Dadaab complex. The camps fall fully under the jurisdiction and laws of Kenya and, therefore, if the camps are insecure, it is because the Kenyan security apparatus has failed in its mission to securitise them.

The terrorist threat that Kenya faces is not a refugee problem���it is homegrown. Attacks inside Kenya have been carried out by Kenyan nationals, who make up the largest foreign group among al-Shabaab fighters. The Mpeketoni attacks of 2014 in Lamu County and the Dusit D2 attack of 2019 are a testament to the involvement of Kenyan nationals. In the Mpeketoni massacre, al-Shabaab exploited local politics and grievances to deploy both Somali and Kenyan fighters, the latter being recruited primarily from coastal communities. The terrorist cell that conducted the assault on Dusit D2 comprised Kenyan nationals recruited from across Kenya.

This latest demand by the Kenyan government to close Dadaab by June 2022 is politically motivated. Strained relations between Kenya and Somalia over the years have significantly deteriorated in the past year.

Mogadishu cut diplomatic ties with Nairobi in December 2020, accusing Kenya of interfering in Somalia���s internal affairs. The contention is over Kenya���s unwavering support for the Federal Member State of Jubaland���one of Somalia���s five semi-autonomous states���and its leader Ahmed ���Madobe��� Mohamed Islam. The Jubaland leadership is at loggerheads with the centre in Mogadishu, in particular over the control of the Gedo region of Somalia.

Kenya has supported Jubaland in this dispute, allegedly hosting Jubaland militias inside its territory in Mandera County that which have been carrying out attacks on federal government of Somalia troop positions in the Gedo town of Beled Hawa on the Kenya-Somalia border. Dozens of people including many civilians have been killed in clashes between Jubaland-backed forces and the federal government troops.

Relations between the two countries have been worsened by the bitter maritime boundary dispute that has played out at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The latest call to close Dadaab is believed to have been largely triggered by the case at the Hague-based court, whose judgement was delivered on 12 October. ��The court ruled largely in favor of Somalia, awarding it most of the disputed territory. In a statement, Kenya���s President Uhuru Kenyatta said, ���At the outset, Kenya wishes to indicate that it rejects in totality and does not recognize the findings in the decision.��� The dispute stems from a disagreement over the trajectory to be taken in the delimitation of the two countries��� maritime border in the Indian Ocean. Somalia filed the case at the Hague in 2014.�� However, Kenya has from the beginning preferred and actively pushed for the matter to be settled out of court, either through bilateral negotiations with Somalia or through third-party mediation such as the African Union.

Kenya views Somalia as an ungrateful neighbor given all the support it has received in the many years the country has been in turmoil. Kenya has hosted hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees for three decades, played a leading role in numerous efforts to bring peace in Somalia by hosting peace talks to reconcile Somalis, and the Kenyan military, as part of the African Union Mission in Somalia, AMISOM, has sacrificed a lot and helped liberate towns and cities. Kenya feels all these efforts have not been appreciated by Somalia, which in the spirit of good neighborliness should have given negotiation more time instead of going to court. In March, on the day of the hearing, when both sides were due to present their arguments, Kenya boycotted the court proceedings at the 11th hour. The court ruled that in determining the case, it would use prior submissions and written evidence provided by Kenya. Thus, the Kenyan government���s latest demand to close Dadaab is seen as retaliation against Somalia for insisting on pursuing the case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Closing Dadaab by June 2022 as Kenya has insisted to the UNHCR, is not practical and will not allow the dignified return of refugees. Three decades after the total collapse of the state in Somalia, conditions have not changed much, war is still raging, the country is still in turmoil and many parts of Somalia are still unsafe. Much of the south of the country, where most of the refugees in Dadaab come from, remains chronically insecure and is largely under the control of al-Shabaab. Furthermore, the risk of some of the returning youth being recruited into al-Shabaab is real.

A program of assisted voluntary repatriation has been underway in Dadaab since 2014, after the governments of Kenya and Somalia signed a tripartite agreement together with the UNHCR in 2013. By June 2021, around 85,000 refugees had returned to Somalia under the programme, mainly to major cities in southern Somalia such as Kismayo, Mogadishu and Baidoa. However, the program has turned out to be complicated; human rights groups have termed it as far from voluntary, saying that return is fuelled by fear and misinformation.

Many refugees living in Dadaab who were interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had agreed to return because they feared Kenya would force them out if they stayed. Most of those who were repatriated returned in 2016 at a time when pressure from the Kenyan government was at its highest, with uncertainty surrounding the future of Dadaab after Kenya disbanded its Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA) and halted the registration of new refugees.

Many of the repatriated ended up in camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) within Somalia, with access to fewer resources and a more dangerous security situation. Somalia has a large population of 2.9 million IDPs�� scattered across hundreds of camps in major towns and cities who have been displaced by conflict, violence and natural disasters. The IDPs are not well catered for. They live in precarious conditions, crowded in slums in temporary or sub-standard housing with very limited or no access to basic services such as education, basic healthcare, clean water and sanitation. Thousands of those who were assisted to return through the voluntary repatriation program have since returned to Dadaab after they found conditions in Somalia unbearable. They have ended up undocumented in Dadaab after losing their refugee status in Kenya.

Camps cannot be a permanent settlement for refugees. Dadaab was opened 30 years ago as a temporary solution for those fleeing the war in Somalia. Unfortunately, the situation in Somalia is not changing. It is time the Kenyan government, in partnership with members of the international community, finds a sustainable, long-term solution for Somali refugees in Kenya, including considering pathways towards integrating the refugees into Kenyan society.�� Dadaab could then be shut down and the refugees would be able to lead dignified lives, to work and to enjoy freedom of movement unlike today where their lives are in limbo, living in prison-like conditions inside the camps.

The proposal to allow refugees from the East African Community to remain after the closure of the camps���which will mainly affect the 130,000 South Sudanese refugees in Kakuma���is a good gesture and a major opportunity for refugees to become self-reliant and contribute to the local economy.

Announcing the scheme, Kenya said that refugees from the EAC who are willing to stay on would be issued with work permits for free. Unfortunately, this option was not made available to refugees from Somalia even though close to 60 per cent of the residents of Dadaab are under the age of 18, have lived in Kenya their entire lives and have little connection with a country their parents escaped from three decades ago.

Many in Dadaab are also third generation refugees, the grandchildren of the first wave of refugees. Many have also integrated fully into Kenyan society, intermarried, learnt to speak fluent Swahili and identify more with Kenya than with their country of origin.

The numbers that need to be integrated are not huge. There are around 269,000 Somali refugees in Dadaab and Kakuma. When you subtract the estimated 40,000 Kenyan nationals included in refugee data, the figure comes down to around 230,000 people. This is not a large population that would alter Kenya���s demography in any signific ant way, if indeed this isis the fear in some quarters. If politics were to be left out of the question, integration would be a viable option.For decades, Kenya has shown immense generosity by hosting hundreds of thousands of refugees, and it is important that the country continues to show this solidarity. Whatever the circumstances and the diplomatic difficulties with its neighbor Somalia, Kenya should respect its legal obligations under international law to provide protection to those seeking sanctuary inside its borders. Refugees should only return to their country when the conditions are conducive, and Somalia is ready to receive them. To forcibly truck people to the border, as Kenya has threatened in the past, is not a solution. If the process of returning refugees to Somalia is not well thought out, a hasty decision will have devastating consequences for their security and well-being.

October 27, 2021

Late nights in Lisboa

Image credit Ondas de Ruido on Flickr CC

Image credit Ondas de Ruido on Flickr CC Contrary to the prevailing idea that Portugal lies at the margins due to a disadvantaged economic positioning in the EU, that small country on the Atlantic coast was actually central in the making of modern Europe. That is, it was from ports such as Lisbon that the subjects of the Portuguese Christian kings, only a generation or two removed from the rule of the Umayaad Caliphate, sailed south hoping to circumvent the trade routes that snaked through the much wealthier and African and Asian kingdoms of the time. On their way to the Indian Ocean, they set up trading posts along the African coast that would eventually turn into outposts for the brutal European expansionism, enslavement, and resource extraction that would define the next 500 years.

It is that centrality to the story of European colonial history, combined with that underdog status in contemporary Europe, that stands out in relief when considering Lisbon’s contemporary cultural stew. Because, after the fall of the Portuguese empire in only 1974, the country is going through a cultural revolution in which the children of the formerly colonized are seizing the identity of a nation and making it in their own image. In that process of re-making, of colonization in reverse, these children of S��o Tome, Cabo Verde, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, and Brazil have made Lisbon one of the most exciting cities for Black Atlantic musical experimentation in the world.

The theme for this season of Africa Is a Country Radio is ���Clubbing across the Continent��� inspired by the Goethe-Institut’s Ten Cities project. In the final episode for the season, we jump over the Mediterranean to see how generations of immigrants from Africa have shaped the music and culture of that city. We talk with one of the co-founders of the seminal Afro-Portuguese electronic music group Buraka Som Sistema, DJ Branko, about his time growing up going to clubs in Lisbon, and about what it means to make Portuguese music in a post-colonial multicultural city.

Listen below or on Worldwide FM.

Organize or Starve!

Sunset over the Port Elizabeth, beachfront, Eastern Cape. Image credit Rodger Bosch via Media Club South Africa on Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Sunset over the Port Elizabeth, beachfront, Eastern Cape. Image credit Rodger Bosch via Media Club South Africa on Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. This is one in a��series of re-publications, as part of our partnership with the South African publication,��Amandla.

On November 1, 2021, South Africans head to the polls to elect candidates for district, local and metropolitan municipalities in the country���s nine provinces. As it stands, 325 political parties are contesting and more than 60,000 candidates will be fielded for the elections. These unprecedented numbers are testament to the widespread dissatisfaction with South Africa���s ruling and opposition parties, chiefly the African National Congress and the Democratic Alliance. Until the last elections, in 2016, the ANC comfortably controlled all but one of South Africa���s big cities, Cape Town. But from 2016 when the DA won narrow majorities in Johannesburg, Pretoria, and Gqeberha, the ANC lost power and parties like South Africa���s third-largest, the Economic Freedom Fighters, became coalition kingmakers. With poor service delivery, corruption and maladministration persisting against the wider backdrop of skyrocketing unemployment and inequality, many South Africans are disenchanted with the mainstream, with July���s unrest only deepening widening sentiment that South Africa���s political class is more concerned with preserving power than serving their constituents.

With political space more open than ever, South Africa���s progressive left is taking its chances too. After the Socialist Revolutionary Workers Party���s humiliation at the 2019 general election following a rushed campaign (it amassed only 25,000 votes, below the threshold required to obtain at least one seat in Parliament), South Africa���s left was once again roaming in the political wilderness, ever more weary of the electoral road to social transformation (The SRWP decided it would sit these elections out). However, with social crises accumulating and grassroots activists on the frontline, it has become difficult to ignore local government as a key site of political contestation and struggle.

Amandla! interviewed representatives of three popular organisations that have decided to stand candidates in the local government elections. They are:

Peter Lobese from Active United Front and former Mayor of Bitou Municipality on the southeastern coast of the Western Cape province.Motsi Khokhoma from Botshabelo Unemployed MovementAyanda Kota from Unemployed People���s Movement / Makana Citizens FrontThe three organisations are collectively running under the banner of the Cry of the Xcluded, a popular front launched in 2020 by the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU), the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) and the Assembly of the Unemployed (AoU) to unite South Africa���s working class���employed and unemployed���in the struggle for jobs, services, and dignity. Their election manifesto can be read here.

AmandlaTell us about your organizations and how they began.

Peter LobeseActive United Front derived its origin from United Front. It is a result of the NUMSA moment in 2013, when the United Front was established as a front that unites the struggle of communities and the workplace. And then in 2016, United Front at a national level indicated that they are not ready to contest at a national or provincial level. But they will allow those communities who are ready to contest to do so.

We just put an ���A��� in front of United Front. We used Active United Front in order to contest. As it happened, we won one seat in the election, and the ANC and DA won six seats each. So we held the balance of power and our councillor, Peter Lobese, became the Mayor. Despite the fact that Peter Lobese was ousted by the ANC and DA, AUF has grown. We are now contesting at a District Level���the Garden Route District. (PL)

Khokhoma MotsiBotshabelo Unemployed Movement (BUM) was founded in 1999 to address massive issues of unemployment, democratic control and social injustices in a non-sectarian manner. We aim to serve both the rural and peri-urban poor communities of our province. Botshabelo is a large township outside Bloemfontein. We have registered for the election as Botshabelo Unemployed Movement and they regard us as a political party. But we know, we are not a political party, because we are operating only at the local level.

Ayanda KotaUnemployed People���s Movement (UPM) / Makana Citizen���s Front was formed in 2009 because there was a vacuum. We started by attending IDP (Integrated Development Plan) meetings, and�� people were saying that we���ve got to do something. These people are taking us for a ride. Then there was a shut down in Makhanda on June 16 and a decision was taken to say, ���We are sick and tired of political parties that are cruel, that are corrupt, that are not honest, that are lying, that have failed us. We must dismiss them. We must recall them. We must dissolve them.��� And one way to do so, is to participate in this local government election, as a community. So we were given that mandate to form this civic structure, Makana Citizens Front.

AmandlaWhat made you stand in this election?

Khokhoma MotsiCorruption, outsourcing of work, clinics of municipalities not functioning, roads bad, factories closing at the municipal level, no investments coming in, local economy falling apart, inequality growing, unemployment growing. All the municipalities are dysfunctional. But when you go to the budget of a ward, that ward every year is being given a particular amount of money that can change the lives of the people. But these things are not being done.

Ayanda KotaWe have marched to the City Hall to highlight the scourge of rape in our society, the scourge of unemployment in our society, the scourge of the collapse of governance. They say ���It is not our competency.��� What bullshit. They are failing to collect the refuse, they are failing on the electricity, they are failing on roads. But they think we must only fight for roads. They don���t understand that these things are intertwined. They don���t understand if they don���t deliver on their constitutional obligations, like lights, it makes certain people vulnerable. There is nothing that can ever be delivered by the current status quo. It���s run out, it���s torn out, it���s finished.The only thing that they can do, over and over again, it���s promises and promises and promises.

Peter LobeseAbuse of power, poor service delivery, and the high cost of services, land questions and many other issues that the community were not happy with. People in the communities are suffering. We are at a grass-root level; we are seeing this suffering on a daily basis. It���s going to be worse now with COVID-19.

Politicians don’t care Khokhoma MotsiWe have seen what happens when people are taking their mandate from political parties. Politicians don���t care about people. But when they are going to election, they suddenly remember them, because they want them to put them again in power. They are not implementing whatever the communities are asking them to do.

Ayanda KotaAnd one must be honest to say, these guys, they don���t listen, they don���t care. To them, it���s all about promises, it���s not about accountability.�� It���s coming over and over again with the same promises, with the same promises and different promises. The right to govern our people has been appropriated by the politicians. There was a slogan ���The people shall govern��� and that slogan has been appropriated by politicians, and it is the politicians that are in government now. It is politicians that govern now.

Peter LobeseThere are two organizations that are dominating politics. It is ANC and DA. And people are tired of those two organizations, they do not want them. They do not trust them anymore. And these organizations, they don���t even change their leaders. You find that there are leaders that have been leading in this organization since 1994, they have been councillors since 1995 and they are still councillors today. And they have done nothing for the community.

AmandlaWhy do you think you can do better?

Khokhoma MotsiWe are not a political party. We are activists. So when you are an activist, you should be involved in issues that are affecting your community. You can’t just relax when you are an activist. You became an activist because of things that you see on the ground that are not going well. And that is why we are fielding comrades in terms of them being councillors. Because we want to change the status quo.

Ayanda KotaWe are activists. You cannot separate our interests and those of the community, because we live in the community, we are part of that community, and we are pursuing the problems of that particular community. So, I think that makes us distinct from a political party.

Peter LobeseWe are community activists who are championing the struggle for the working class at a local level, at a grassroot level. So, we are a hand of the community, we are not a political party. You can say we are a movement, a community-based movement. At times, political parties have a tendency to divide the community. Ours is just to embrace the community struggle, because we are encouraging citizens to be active. Hence we are saying Active United Front, it means active citizens. You will find members from various political parties in the United Front, from the ANC, from the EFF, from DA and others. But even in the election, they said they will stand by what United Front is going to do and they will vote for United Front.

Our pledge Khokhoma MotsiWe have signed a pledge including: A living wage for councillors. Communities must have full control of our councillors, because they are not going to get that full salary. If you are getting R50,000 in PE, the organization and communities will agree to pay you the living wage���R15,000, R12,500 at least.

Ayanda KotaNo corporate boards: We will refuse to sit on any boards of corporations. Politicians are serving in all these corporate boards, whose sole interest is to maximize profit. And it���s capturing them.

Live locally: if we get elected, our comrades will continue to stay where they are currently staying, in their respective wards. They will not hire trucks in the deep of the night and put in their furniture and go stay somewhere.

Subject to recall: we respect the right of recall. If our member is recalled, we will not be consulting with a political party whose head office is in Joburg. That makes us an activist organization. But also, that makes us a community organization.

Caretakers of the pledge Ayanda KotaThis pledge is important. Your councillors have committed to this oath. And most important, you have a very strong UPM outside, which will also be carers and caretakers of that pledge, to forever remind you that you have committed to this. That will continue to play that critical role that it���s playing now. I think that can give us a peaceful night.

Before we started attending, IDP meetings were conducted in English and a bit of vernacular. But the details are hidden in English. English really excludes a majority of people. But all that the politicians were worried about was to get the white cloth on the table, the bottles of water, and their chairs covered.�� We were challenging those details because they were excluding our people. Some of these wards are quite vast. It was important to organize transport for people to attend the meetings. And also make sure to give notice on time. And accounting to the community: to say, ���We were here and this is what we promised. This is what we have done and this is how we are moving forward.���

Mandate from our communities Khokhoma MotsiWe must take the mandate from our communities. Everything will come from communities. What they need, what they are thinking, what you can do in council. So that is the backbone of us participating in this election. The mandate from the communities, the suffering of the community, the demand of the community.