Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 113

November 15, 2021

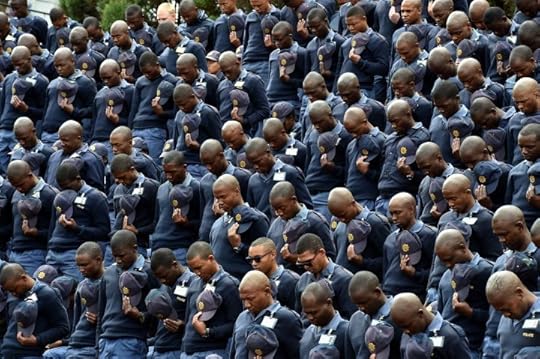

Policing the colony

South African Police Service Commemoration Day, Pretoria. Credit GovernmentZA via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

South African Police Service Commemoration Day, Pretoria. Credit GovernmentZA via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. This is one in a series of re-publications, as part of our partnership with the South African publication, Amandla.

When one of the hundreds of yearly killings eventually makes the news���more than one each day���some of us flare up in anger and tears. Some ask: ten years after Andries Tatane, nine years after Marikana, has anything changed? This is the wrong question to ask, because it assumes that we should expect anything to be different. The transition from apartheid to neoliberalism was endorsed and brokered by corporate capital, allowing capitalists to make their profits but lose their stigma. Apartheid lives on anew, now palatable to global liberalism, and we can see that in policing. Instead, we should ask: is policing as a whole any good?

The story of the police is that they are heroes who protect and serve. The fastest way to end that fabrication is to ask what and who exactly they protect and serve in practice, and who in turn is bullied and brutalized.

Everywhere, overall, the police protect the current order. From their creation during colonization to now, police have served the wealthy against the many, and the white against the rest. In the US, we have seen large-scale mass resistance and outrage against police violence, and yet the situation here is much worse. The lowest independent estimate I have found claims that the South African Police Service kills almost two-and-a-half times more people than US police. You know someone who has been raped by them. Ask any land, housing, or mining activist about their experiences with police, and you will start to see a horrid reality that we all must see always. Despite this, as anti-capitalists, our programs generally do not include principled resistance to policing.

Like the wall of a dam, police are the physical force preventing the redistribution of resources of this land to the people. It is the police who demolish homes and evict poor masses from stolen land when occupiers try to unsteal it. It is the police who, just by doing their job, support the bosses when overstretched workers demand a decent life, dooming workers��� children to that same poverty.

Policing does not solve the issue of crime. More than anything, it is part of the mechanisms that create crime, by maintaining the private property relations that uphold our unequal society and enforcing the everyday criminalization of poor people trying to improve their lives. The harms of policing are not aberrations from the norm. They are what policing is and has always been, because of its systemic function. And therefore it is unfixable. Prisons, too, are a harmful, abject failure, but that is for another article.

Marikana should never have happened because if this were not a colonial nation, no miner would have to strike for a measly R12,500. The human reality is that nobody with a full stomach and a roof over their head for themselves and their loved ones would ever go down into those mines. Those mines are built on extreme exploitation, and while they live, so does colonialism. Among other things, it is the police, standing there, holding it together.

My brief experience in reformist circles is one of people doing earnest work���but with an underlying anxiety. They notice that their solutions are indefinitely postponed, their actions providing only token prosecutions, minimal reforms, and other half-measures that may at best give the appearance of change, and only occasionally do something about the worst abuses. In practice, these changes all just amount to the minimum needed for the whole machinery of the state and capitalism to continue to lubricate its gears with the blood of the marginalized.

At the end of apartheid, there were reforms that came at great financial cost���the police were demilitarized, retrained, and democratized to a significant extent. But all it took was one or two authoritarians in powerful positions to unmake that progress.

Referring again to Marikana, we have seen commissions and panels of experts deliberating and making official recommendations, and then engaging police on those recommendations up until today, nine years later. Hundreds of recommendations that will go nowhere���they are as likely as real redistribution of resources under capitalism, because they are part of the same problem.

Reformists do not take into account the overwhelming depth and cost of the changes they want. For the people that our society values so little, it will not provide them the R12,500 they need.

Our police accountability agency, the Independent Police Investigative Directorate, has been shown repeatedly by journalist group Viewfinder to be systemically useless. It is largely ignored by the police themselves, even when it does make findings against police. Like all purely reformist approaches, in practice this agency only uses up and diverts people���s energy and hope for change in a dead end that they have no real say in. This gives some the false impression that there is police accountability. How many years has it been since Marikana was captured on video, and has a single one of those murderers and those who gave the orders been held accountable? Even less so for less famous cases.

So it is reformism���rather than abolition���that is really unrealistic or ���utopian.���

The twin harms of law and police: let���s decriminalize and defund. Instead of reformist reforms intended to capacitate police, we can limit advocacy to radical reforms, which reduce their capacity to harm. Defunding is not just the removal of police funding; it is the diverting of funding from policing to actual social goods like housing, food security, healthcare, and education. These can help everyone and avoid the reproduction of the conditions that make people feel we need police. Together with that, we should start with the decriminalization of poverty generally, and the removal of the harmful socioeconomic effect of related harassment, fines, and imprisonment of the marginalized. In this way, we can begin the path to completely changing the way that we relate to accountability. The African Commission for Human and People���s Rights has already adopted principles towards decriminalizing petty offenses���you and your organizations can go beyond that.

Delegitimize: police are not on the side of workers or the marginalized. Police are ���workers��� who have chosen to base their livelihoods on the current order. Their jobs depend on defending capital and the ways of thinking that reproduce capitalism, so policing will tend to attract people who are willing to do that. Needing a salary is no excuse for evicting poor families, shooting rubber bullets at hungry students who seek a better life for all, or abusing undocumented migrants. As long as they do their job, they cannot be our allies. Police unions in practice tend to defend some of the worst cops and abuses, while pushing for more money and less accountability. It is for us to denounce the whole institution of police, reject their unions, and demoralize individual officers so that they can leave the force and find themselves on the side of liberation.

These demands are not only for our sake: if South African police are anything like their siblings overseas, compared to other sectors, they have high rates of child abuse and domestic violence and are more likely to commit suicide or suffer from addiction.

Unlike other places, there has not yet been a comprehensive blueprint built for an abolitionist program in South Africa, but we do have precedents. My generation hears some of our elders tell stories of how, during apartheid, regular people organized to push police out of the townships. Many people formed street committees and community groups and student councils to do the work of arranging community safety without police. We can draw from that history���now lost on much of the youth���and improve upon it, as one essential part of our broader anti-capitalist struggle.

Once we recognize that relations of policing are part of the society we wish to change, we must ourselves avoid becoming like police or prison guards. Instead, we must foster organized and strong communities which can deal with their own problems in a human way. The power we hold in our communities and movements cannot be taken away simply when officials are corrupt, laws are changed, or state budgets are cut.

We cannot say exactly what this process would look like in our most unequal society yet. But we can learn from the past, and we can learn from abolitionists across the globe. It is for us to explore what is possible and make it together.

November 12, 2021

Zimbabwe���s second innings

Image credit Jekesai Njikizana �� iZimPhoto.

Image credit Jekesai Njikizana �� iZimPhoto. ��� Maj. Gen. SB Moyo, 15 November 2017Good morning, Zimbabwe. The situation in our country has moved to another level.

��� President Robert Gabriel Mugabe, 20 November 2017Asante sana.

��� Mugabe, 21 November 2017I, Robert Gabriel Mugabe, in terms of Section 96, Sub-Section 1 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe, hereby formally tender my resignation as the President of the Republic of Zimbabwe with immediate effect.

Finally, it rained. I stood on the lawn with arms outstretched like a scarecrow, bare feet rooted to the sodden soil, droplets dancing on skin. They call this city ���Skies,��� and in all weathers the moniker proves apt. From horizon to horizon, a vast glaucous cloudbank roiled and swelled, spilling water in great sheets to quench the earth and clean the dust from the air.

October was not yet fully past when the first rains of the summer arrived that year. I was in Bulawayo to cover a pair of matches between Zimbabwe and the West Indies. It would be a positively profligate ten days of Test cricket���the sport���s longest and highest-level form���at Queens Sports Club in the City of Kings, another of the city���s titles. The change of season had been heralded by a wild fluctuation in the mercury: the week of the first Test, the temperature shot up to 38 degrees before plummeting down to 14. Then the rain arrived, early and dramatic, amid thunder that cracked the sky and gusting wind that shook the trees in the yard around me, spattering and spraying raindrops even under the covered verandah. Signs and wonders.

Zimbabwe stumbled to defeat in the first game, failing to build upon the advantage their bowlers had earned on the first day���but they rallied to save the second. Hamilton Masakadza scored his final Test century (a score of 100 runs by an individual batter in a single inning) versus the same team against whom he���d scored his first, as a teenager, all the way back in 2001; Sikandar Raza���s allround brilliance kept Zimbabwe in the match; and Regis Chakabva and Graeme Cremer batted together for more than two-and-a-half hours to draw the game on the fifth afternoon.

Having arrived so spectacularly, the rain never really left, settling into a steady mizzle that people here call guti. We were listening to the water dripping through the gutters and onto the verandah stonework of that house in Hillside���a suburb a couple of kilometers from Bulawayo���s city center���when the rumors began to circulate. Labeled a ���coup plotter��� by then-First Lady Grace Mugabe, Emmerson Mnangagwa had been dismissed from the vice presidency on November 6th and left the country in dramatic circumstances. His whereabouts were unknown. The following week, tanks and armored personnel carriers were seen moving around the outskirts of Harare, with video clips being shared rampantly across social media.

We scrolled through hot takes, speculation, and memes; blasted Bob Marley’s ���Zimbabwe��� out of subwoofers with bass to rattle your soul; and wondered what would happen next. Our host assured us that he knew all the best caves in the nearby Matopos hills to hide out in, should things come to that. But there was as much curiosity as there was trepidation, and once the situation really started to move, I knew that I had to be in the capital to witness, in person, whatever was going to happen.

The rain beat me to Harare. In fact, it arrived in time to stop play after tea on the second day of the Logan Cup match, where the Mountaineers faced the Rising Stars at Harare Sports Club (HSC) on 13 November. Masakadza played in this game too, but there was no century this time. The Logan Cup is Zimbabwe���s premier cricket competition, the trophy having been contested since 1903. Its cricket games are played over four days with two innings per side, with breaks for lunch and tea in the afternoon and a pace of gameplay that can vary from frenetic to glacial. This is cricket in the classical sense.

On that same drizzly afternoon, General Constantino Chiwenga, the head of Zimbabwe���s army at the time, held a press conference backed by almost 90 senior army officers at military headquarters in Harare. ���The current purging,��� he said, ���which is clearly targeting members of the party with a liberation background, must stop forthwith. We must remind those behind the current treacherous shenanigans that when it comes to matters of protecting our revolution, the military will not hesitate to step in.���

The next day, the military stepped in, with heavily armed soldiers in armored vehicles taking up key positions around the city and entering the studios of the state broadcaster, ZBC, from which Major General S.B. Moyo delivered his famous speech early on the morning of the 15th.

���Good morning, Zimbabwe,��� Moyo said. ���The situation in our country has moved to another level.��� And so it began. Was this a coup? A soft coup? #NotACoup? Schrodinger���s coup, perhaps? Or, best of all, playing on Zimbabwe���s pseudo-currency: not a coup but a ���Bond Coup������it has 1:1 value with a coup but can only be used in Zimbabwe.

Whatever it was, Moyo was insistent on what it wasn���t. ���This is not a military takeover,��� he said, incongruous words for a man clad in military fatigues on an unscheduled dawn broadcast. ���Remain calm, and limit unnecessary movement,��� he added. ���However, we encourage those who are employed and those with essential business in the city to continue their normal activities as usual.���

He can surely not have been thinking of men, in flannels and floppy hats, playing a first-class domestic cricket fixture. But that���s exactly what the cricketers at Harare Sports Club did. It is worth pointing out that the sports club is literally next door to State House, the official residence of the president. So close is the country���s premier cricket ground to the president���s old digs that Nathan Lyon, playing for a visiting Australia A-side in 2014, claimed to have hit a six that landed on the presidential lawn. ���I think Bobby Mugabe was under attack,��� Lyon later claimed. ���Second-last ball of the game, three runs to win, it went the journey.���

When Zimbabwe was a fledgling Test nation back in the early 1990s, Mugabe would often pop across the road to watch some cricket or welcome incoming captains. There are several photos of him at HSC, possibly the most (in)famous of which is that of his handshake with Michael Atherton, the English captain, during England���s ill-fated inaugural tour of Zimbabwe in late 1996. ���Cricket civilises people and creates good gentlemen,��� Mugabe has been quoted as saying (though the quote is possibly apocryphal). ���I want everyone to play cricket in Zimbabwe; I want ours to be a nation of gentlemen.���

The English have not sent a team to Zimbabwe since 2004, and Mugabe moved out of State House in the mid-2000s. But it has remained a potent symbol of state power in the country, fortified and watched over day and night by the presidential guard. Fast forward to 2017, and it was only natural that the place would be the locus of a tectonic power shift���and so, outside the cricket ground were tanks and soldiers. This was ground zero of the palace revolution.

Image credit Jekesai Njikizana �� iZimPhoto.

Image credit Jekesai Njikizana �� iZimPhoto.���There was speculation that something is about to take place,��� remembers Vusi Sibanda, a veteran Zimbabwean international cricketer, and one of the elder statesmen of the Mountaineers side that played that game. ���We knew that being so close, being in the vicinity of it all, that we had to tread very carefully. They said people should just stay away or stay indoors, or something like that, and we were in the middle of the game. I remember being told, let���s just turn up for the game, and see what happens. And if something is to happen, so be it.”

The city center emptied, and for a couple of blocks in every direction, cricketers and soldiers were the only people anywhere near HSC. ���There was a time when everything just went dead quiet,��� explains Sibanda. ���Everything almost just stood still. We didn���t even know what to do. So we decided to just finish the game. We were waiting in limbo, not knowing what was happening next.���

Play on the fourth and final day of that Logan Cup match at HSC, on 15 November, was scheduled to start at 9:30 a.m to make up for time lost to rain earlier in the game. However, the damp conditions overnight delayed it until 10 a.m. Despite being 300 runs ahead, and the likelihood of losing more time to rain during the day, the Mountaineers did not declare their innings closed but continued to bat, with top order batsman Mohammad Eqlakh not out on 135.

Eqlakh���s story could fill a feature all on its own, but it���s worth racing through the key twists and turns of how he found himself playing professional cricket in Zimbabwe. Born in the tiny village of Nevada (population 1,300) in Uttar Pradesh, India, he played age-group cricket for Vidarbha���s regional team and caught the eye of the coach of Zimbabwe���s under-19 squad when they visited India. Expat cricketers are not unheard of in Zimbabwe���the national team���s star allrounder, Sikandar Raza, was born in Sialkot and originally wanted to be a fighter pilot in Pakistan���s Air Force before his path turned to cricket in southern Africa���and it seems that this was the route Eqlakh was pursuing.

Eqlakh arrived in Zimbabwe ahead of the 2017 summer, and in the space of six weeks he cracked a sparkling maiden first-class hundred in that fateful match at HSC, witnessed a putsch first hand, was hit by a car, and endured a torrid experience getting a head wound stitched in a decrepit public hospital. Worse was to follow. In December, it was discovered that Eqlakh���s work visa was not in order, and when he went to Home Affairs to get it sorted, he was promptly detained, and deported back to India days later. That, alas, is not where his story ends. In 2019, Eqlakh was arrested on a murder charge in Nagpur. The case has gone to trial.

But back to the game. On that rainy day in November, Eqlakh was still dreaming big dreams of willow and leather and fame and fortune, and could not have imagined the trouble and woe that lay ahead of him. He raced to 153 not out���his highest score in professional cricket��� setting the game up for his team and turning plenty of heads in Zimbabwe���s cricket community.

The Mountaineers declared their innings closed at 262 for 6, leaving the Rising Stars���essentially an academy side made up of talented but inexperienced rookies���the challenge of batting through the fourth afternoon. As events outside the bubble of the cricket ground moved ahead apace, concentrating on the game became almost as difficult as dealing with the Mountaineers��� slippery pace attack.

���I remember that game very well,��� one of the youngsters who was part of the Rising Stars squad told me. ���Everything happened on day four. It was a scary moment, to be honest, because you didn���t know what could have happened. Anything could have happened on that day. There were what-ifs. What if people just stormed into the ground? What if this happens? What if that happens? What will we do?���

As it happened, of course, nothing happened���at least not yet. The rain forecast for the afternoon did not arrive and Zimbabweans took a softly-softly approach to business as usual. At HSC, wicketkeeper-batsman Ryan Murray battled to 84, shaking off the cobwebs after months of recovery from a back injury, but the Mountaineers��� seasoned pace bowlers made short work of the Rising Stars��� newbies, bowling them out for 144 to win the match by 193 runs.

Meanwhile, in Bulawayo, I had bought tickets for what southern Africans might uncharitably call a chicken bus. A couple of days later, on 17 November, we headed for the capital.

When we arrived in Harare, it was clear that the situation had, indeed, moved to another level. There were people everywhere, in their hundreds of thousands, and a carnivalesque suspension of the normal rules of the city. I saw people streaming through Africa Unity Square like flood water flowing around bedrock. I saw two men dancing in perfect tandem next to a kombi that was so full, people were clinging to the outside of it, its sliding side door wide open. I saw a woman stop four lanes of traffic to dance in the middle of the road with a Zimbabwean flag. I saw a man in a windbreaker LARPing as a revolutionary, carrying a stick wrapped in a belt as if it were an AK-47. I saw masses of people crowding around tanks outside the Munhumutapa Building, the High Court, and Parliament, fist-bumping soldiers and passing babies up to be held by them. I saw a man smoking an enormous joint who just looked at me and laughed, raising the burning saber to say, ���this is the new Zimbabwe, it���s legal now!��� I saw thousands and thousands of smiling people.

Image credit Jekesai Njikizana �� iZimPhoto.

Image credit Jekesai Njikizana �� iZimPhoto.The bus finally pulled into Roadport, the central bus station, and we jumped with our backpacks into the back of a friend���s rattletrap, open-top bakkie, for another drive through the city center. We took in Fourth Street, Jason Moyo Avenue, the Jacaranda-lined tree tunnel that is Milton Street. Every so often, people would leap into the back of the bakkie with us to sing into the crowds or to high-five passers-by. Someone handed me a flag.

We ended up outside Harare Sports Club, a place that holds a very special meaning for me. There is a tradition in my family: at least one of us must be present for every cricket match played here by Zimbabwe. Here, I have cheered and cried; I have witnessed too many excruciating losses and just enough miraculous wins to keep me hoping that the next one isn���t too far away. That hope is the same for any follower of Zimbabwean cricket. Always, there is hope.

But I had never seen anything like this. I put my hands on an armored vehicle parked at the corner of Tongogara and Fourth, just to check that it was real. Then, I looked up at the grandstand behind the trees inside HSC, then down the road to the line of soldiers blocking the crowd from advancing on State House.

In every direction, the streets were filled with people carrying flags and placards. Pastor Evan Mawarire, who had led the #ThisFlag protests the year before, addressed a huge crowd of people from the back of a military vehicle parked outside State House. On Fourth Street, the surging throng of citizens was joined by a group of war veterans. An army tank led the crowds back down to Herbert Chitepo Avenue and Second Street, where yet more people joined them.

There���s a peculiar energy that flows through situations like that. There is a buzz in the air. A static charge. You feel strongly that something meaningful is happening. It is also very much a shared experience, the important thing being not that you are here, but that we are. There���s an almost hyper-reality to it. You can read the pulse in the neck of a person one hundred meters away, even as you can���t quite believe what your eyes are seeing.

Three days, two nights and one ���Asante sana��� later, the crowds were once again out on the streets. This time, it was the celebrations that had moved to another level. And once again, cricket found itself, oddly, at the center of it all. The Rising Stars were playing their next match at Harare Sports Club when news started to spread of Mugabe���s resignation, kicking off a nationwide street party.

���It was probably just after 4:30 pm when we started hearing the noises and everything,��� a player told me. ���I actually didn���t know exactly what was happening. You could just hear cars outside on the road, hooting, people making noise, shouting, singing and everything.���

The team changing rooms at HSC are housed in a multistory building on the northern side of the ground, sitting next to the gabled pavilion that is a throwback to the facility���s colonial origins. Looking out from the team balcony, on your right are concrete grandstands, beyond which stretches the rolling green felt of the Royal Harare Golf Club. To your left, behind a row of enormous fir trees and high walls patrolled by the presidential guard, is State House. In front of you lies the hallowed ground of the cricket oval, lined with jacaranda trees and a pair of floodlight towers. Beyond, the distinctive curved penthouses of the Northfields apartment complex overlook the ground, and two of the city���s major arteries intersect: Fourth and Josiah Tongogara Streets.

���I remember watching the scenes from the balcony outside the change-rooms at Sports Club,��� the same player continued. ���You could just see people waving flags. People singing. People dancing on top of their cars, or on top of someone else���s car. That day was just . . . it was historic in its own way.���

���Obviously, there were distractions from outside,��� another player explained. ���People were on the streets. It wasn���t easy, but I had to concentrate on the game and put myself into a position where I���m focused on the game, not on what���s happening out there. There was a lot of noise, mate, I promise you. People were singing out there. It felt more like something rowdy from high school, you know what I���m saying? It was quite an experience.���

���I was sitting upstairs in the Sports Club changing room, and we could see the people on the other side of the wall, on the road,��� yet another player remembered. ���You could see everyone marching past. I vividly remember that. You could see everyone.���

���The coach managed to get us to concentrate on the game at hand, and keep that out of our minds. But it was tough. Our country was changing before our eyes. It was a bizarre experience. No other words to describe it. It���s nice to see people unite. We were fielding at one point, and I remember a couple of the other team going up to the wall, standing on the wall and looking over into the crowds of people, joining and then coming back. You could hear the people outside. Singing and shouting. Something you won���t forget.���

Across town, another cricket match was taking place in a setting every bit as evocative as Harare Sports Club. While HSC sits next door to State House, Takashinga Cricket Club (CC) in Highfields is adjacent to the Zimbabwe Grounds, where a succession of epochal political rallies have been held over the years. It was here that Bishop Abel Muzorewa, desperate as the Zimbabwe-Rhodesia experiment was crumbling, held a three-day rally in an attempt to shore up support for his government. A year later, in early 1980, it was here that Mugabe, returning from exile in Mozambique, held the ���Star Rally��� months before his political party, Zimbabwe African National Union���Patriotic Front, swept to power in the country���s first-ever elections. The Zimbabwe Grounds were the setting for the chaos and violence that followed the heavy-handed dispersal of an opposition rally in March 2007. And in November 2017, a crowd to rival any that had come before gathered here to march to town in support of calls for Mugabe to step down and, a couple of days later, to celebrate his resignation. The Zimbabwe Grounds have played a pivotal role in the political life of the nation, and Takashinga CC has been equally crucial to the evolution of Zimbabwean cricket over the last quarter century, producing a slew of talented players and several national captains.

On the day that Mugabe resigned, Takashinga CC was hosting a Logan Cup match between the Mountaineers and the Mashonaland Eagles. Mountaineers captain Donald Tiripano won the toss, and his team was in the field when the news started to spread.

���It was strange,��� remembers Sibanda, who also played in that game. ���I can���t put it into words exactly. But when you���re on the field, you���re trying to concentrate on the game itself. There were some whispers and talking about what was happening off the field, that does happen, it���s normal. But we just played the game.���

Eagles opening batsman Cephas Zhuwao was in the form of his life that season, and his bolt into Zimbabwe���s World Cup Qualifier squad started with a string of audacious innings in domestic cricket. On this morning, he launched into the Mountaineers��� bowling attack, thrashing 46 of the 52 runs scored in the first hour of the game. By the lunch interval, he was on 77 not out, with 10 fours and three enormous sixes. But his fireworks on the field were nothing compared to the bacchanalia of the goings-on outside.

Image credit Jekesai Njikizana �� iZimPhoto.

Image credit Jekesai Njikizana �� iZimPhoto.���The noise was there, you could certainly hear what was going on outside the Takashinga ground,��� says Sibanda. ���There were cars hooting, people making noise. Celebrating. It did happen. In other cases, when things like that happen, you might feel very much threatened, like, something���s going to happen, something is going to blow off here. But at this time, it didn���t feel like that. At all. You didn���t sense danger. People were just like, hey, something new is happening here. But, you know, we might as well just carry on.���

I was on the other side of the city, in the house where I grew up, when the news of the resignation started to spread. A man ran down the street holding a flag aloft, announcing the news and calling for everyone to come outside. I don���t remember where I was, exactly. On the verandah, perhaps. In the lounge, maybe. Drinking a cup of tea, almost definitely.

Just another Tuesday in Harare, a city homebrewed in rumor and hearsay. Tangible truth can be hard to locate here. Information comes second- or third-hand, from a friend���s cousin���s business partner, who knows the brother of an important so-and-so. And so it was with the coup that by any other name would smell just as fishy. But the joy writ on all those faces? That was real. The feeling of togetherness? Real. The rumble of the power of the people was as real as rolling thunder, and real, too, the hope that we all felt. Hope and optimism, despite the present difficulties.

Hope takes on a particular hue in Zimbabwe, a faith in the unseen and, perhaps, even the impossible. Consider the expression ���hope against hope������to have hope, even when that which we hope for is unlikely ever to happen���and you will start getting close to the Zimbabwean version. Any Zimbabwean cricket fan will be able to tell you all about it. And who against hope believed in hope, that he might become the father of many nations. As it was promised; so shall your descendants be. But when?

���Obviously, we all had hope,��� remembers a cricketer who played in that game at Takashinga. ���The situation in Zimbabwe at the time wasn���t the best of situations, so you know when everyone is not happy, and then there is that light at the end of the tunnel, you do have hope. So I���ll speak mainly for the young people that I played with during those times. We were very hopeful. We were excited as well. Change is hard, yes, but sometimes when you���re living in the worst conditions, you hope for change, no matter how change would come to you. You don���t know how the change is going to turn out, but you���re still excited to see some changes. You just hope that it is change for the better.���

One is necessarily cynical about the motives and movements of the powerful. In November, we were fistbumping soldiers in the street. By the following August, soldiers were shooting people dead in those same streets. If anything, those heady days in November 2017, and the days since, have shown the locus of real power in Zimbabwe. But they have also shown something else. Even if only for a moment, Zimbabweans heard the rumor of freedom, and hope spread like wildfire. Hope persists.

���After the game, when we were driving off, I���d never seen so many Zimbabweans happy like that,��� remembers one young Rising Star. ���We drove from Harare Sports Club to where we were staying, and all you could see was people singing, dancing, everything, just people with flags and all that. So that was a different experience. Strange times. I���d never seen so many people just happy like that, all over the streets. Everyone just looked so free and happy. The scenes were amazing to witness.���

���Zimbabweans were happy. People were happy. People were excited. It was really good to see people getting together, you know. I think it had been a while since Zimbabweans had actually celebrated together like that. But yeah, the cricket went on. The cricket went on.���

November 11, 2021

The war in Ethiopia

Photo by Alazar Kassahun on Unsplash.

Photo by Alazar Kassahun on Unsplash. https://africasacountry.com/2018/02/the-ghosts-of-adwaIn April 2018, Abiy Ahmed was sworn in as Prime Minister of Ethiopia, and in 2019 he won the Nobel Peace Prize for resolving the long-standing border conflict with neighboring Eritrea. However, since November 2020 when he ordered the military to violently quell an opposition movement in Tigray, a region along the northern border, his international standing and domestic popularity have significantly declined. Now, Ethiopia faces the prospect of splintering.

Prior to Abiy���s election, the government of Ethiopia had been dominated by the Tigray People���s Liberation Front (TPLF), which had effectively ruled the country since 1991 when they joined forces with other armed groups to overthrow the previous government. After Abiy came to power���he had organized the victorious Prosperity Party out of many ethnic-based parties to oust the Tigrayans���the TPLF quit the government and its leadership returned to Tigray where it focused on consolidating its authority in the region, and curtailing the influence of the Ethiopian government and military.

In August 2020, previously scheduled elections throughout Ethiopia were postponed ostensibly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the TPLF considered this a betrayal and held its own elections that the central government deemed illegitimate. This, coupled with the TPLF���s seizure of military bases in Tigray, pushed tensions between Abiy and the TPLF over the brink and shortly thereafter�� Abiy sent the Ethiopian army to Tigray leading to a large-scale armed conflict.

The war has produced a mounting humanitarian crisis in Tigray, with aid workers struggling to bring in more assistance, especially food. The central government, however, has opposed this as it believes it sustains the TPLF. Since July, only 686 aid trucks in total have entered Tigray���far less than the 100 a day needed to avert famine���and none since October 18. Furthermore, there are few aid personnel on the ground to facilitate delivery and distribution. In August, Ethiopia halted operations by the Dutch branch of Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) and the Norwegian Refugee Council. The UN has also reduced its staff from 530 to around 220. On September 30, the Ethiopian government announced the expulsion of seven senior UN officials, including the country heads of UNICEF and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. On November 9, 16 other UN personnel were detained by the government. Currently only about 1,200 humanitarian workers (including the UN) remain in Tigray. Moreover, violence against aid workers has also undermined relief efforts; 23 have been killed in Tigray so far. Currently, despite 5.2 million people in need (over 90% of the population in Tigray) and about 1.7 million displaced, only about 10% of the aid required has been delivered.

As worrisome as the situation in Tigray is, also of concern is that the war appears to be metastasizing���more armed actors are entering the conflict and the areas being fought over are expanding. Earlier this year, the government deployed militias from the Amhara region and allowed intervention from forces in neighboring Eritrea. But, the course of the conflict turned in late June 2021 when the TPLF dealt a severe blow to the central government by�� retaking Mekelle, the capital of Tigray. Shortly thereafter, Abiy appeared to realize he had overreached in attacking Tigray and unilaterally declared a ceasefire. Yet, the TPLF has continued to fight, first pushing out Ethiopian forces from the remaining parts of Tigray, and then turning their attention southwards toward the central government.

Much like the 1991 campaign that toppled Mengistu Haile Mariam���s government, the TPLF has made alliances with other armed opposition groups, and last week a new group emerged, the United Front of Ethiopian Federalist and Confederalist Forces. In addition to Tigrayan forces, it also includes the Oromo Liberation Army, the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front, Agaw Democratic Movement, Benishagul People���s Liberation Movement, Gambella Peoples Liberation Army, Global Klimant People Right and Justice Movement/Kimant Democratic Party, Sidama National Liberation Front and Somali State Resistance. This coalition has indicated that its main aim is to preserve the 1995 constitution that ensures federalism and the right to self-determination.

On November 3, Tigrayan forces captured Dessie and Kombolcha (two towns on the road to Addis Ababa���only about 160 miles northeast of the city) and are now positioned to attack the capital. In response the Ethiopian government has declared a state of emergency and encouraged citizens to take up arms to defend the capital. Will backfire from Abiy���s failed political-military strategy blow up the status quo of single-state Ethiopia?

Aside from the urgent humanitarian conditions, lurking in the background is the issue of who is responsible. If Abiy is deposed and survives, there will surely be calls to put him on trial for war crimes. This demand will partly be for revenge, but also to obscure that atrocities have been committed by all parties in this conflict. According to a recently concluded joint investigation by the UN and the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission of conduct during the conflict in the period of November 2020 to June 2021, the government as well as forces from Tigray and Amhara have committed abuses, such as torture, rape, and civilian killings. Although reports like this are welcome, they overlook the impact of colonialism, its intentionally provocative and fraught political geographies, and the political cycles of its legacies. The constructions of many postcolonial states have been wedded at birth to difficult mixes of ethnic groups whose identities were purposefully politicized in a ���divide-and-conquer��� strategy, thereby creating weakness that allowed European domination.

Although ethnicity is not inherently destiny, these problematic dynamics are playing out once again in Ethiopia, a country with more than 80 different ethnic groups and a population of over 100 million. Since the formal dissolution of colonies, arms sales and proxies have been a staple of influence. Several countries have sold millions in arms to Ethiopia, which has contributed to the violence. In the past five years about $92 million worth of arms have come from Russia ($69 million), the US ($10 million), Israel ($4 million), China ($4 million), France ($2 million), and Germany ($2 million).

The digital frontier is another space for expressing influence and as disclosed in the recent Facebook Papers, the armed conflict in Ethiopia has likely been hastened by social media postings by various militia groups intent on inciting ethnic violence, though no action was taken by Facebook to stop this practice. Therefore, beyond Abiy���s gambit, this situation underscores that the colonial project has backfired and is blowing up Western notions of statebuilding. Abiy should be held to account for instigating this round of violence, and other armed actors should likewise be prosecuted for perpetrating atrocities. But regardless of these legal cases or who rules Ethiopia, will anyone be accountable for configuring these volatile circumstances?

November 10, 2021

Musically, Congo is the mothership

Still from The Rumba Kings.

Still from The Rumba Kings. On October 6, 2021, both Congos���Brazzaville and Kinshasa���submitted a formal proposal to UNESCO to recognize Congolese Rumba as an intangible cultural heritage. When UNESCO announced the list, Congolese Rumba did not make the cut. At least, Morna music from Cabo Verde did. Recognizing a musical genre as an intangible cultural heritage brings with it things like legal protections. Were Congolese Rumba to command entry, it would mark a further centering of African culture in the world���s imagination and priority.

Over the last decade, a concerted effort by producers, filmmakers, historians, journalists, and image-makers worldwide has sought to reinterpret Africa���s image and center its place in modern history. Books, records, films, and an ever shifting gaze away from the metropoles of North America, Europe, and East Asia have wonderfully exposed Africa���s rich offerings.

Each endeavor has its own motivations but each are bound by a consensus that it would be a grave error, and downright idiotic, to continue to ignore the vanquished cultural history and stories that have shaped a continent that sits as much at the center of most conventional maps as Europe.

Musically, Congo is the mothership. Congolese rhythms laid the groundwork for many styles of music across the Atlantic, most notably in Haiti, Cuba, and Brazil. Its guitar styles caressed Africa, inspiring artists from Senegal to Somalia to South Africa to South Sudan. As early as 2011 in Accra, I picked up a copy of one of the best selling albums in Africa in the 1980s, an LP by Rumba maestro Docteur Nico.

With nearly 90 million people, projected to reach 200 million by 2050, bustling cities, a storied culture, and a history that demands rethinking, not least because our so-called modern world runs off the toil of Congolese labor and the fruits of their soil, the world needs a piece of storytelling humanizing a place few will visit or even experience via the internet or TV in their lifetime.

Rumba Kings, a new documentary by Alan Brain, a Peruvian-American filmmaker who boasts an impressive, committed CV, offers a commendable and tireless argument for both an intangible cultural heritage and a centering of the Congolese way���but, like all immense endeavors, is not without flaws.

It excels through its tightly knit narrative and historical recount, not sparing the brutality of Belgian colonizers, as well as a clean, simple structure and edit, making the documentary accessible. The utter lack of western or European voices and faces is most welcome. Congolese musicians are expected, but Congolese scholars and pundits are not as obvious, often easily overlooked. European and American documentaries on Africa have in the past centered a white character or produced something entirely devoid of African voices.

As someone intimately familiar with the intricacies and difficulties of working with archives and sourcing aged imagery, the sheer abundance of archival footage and photography in Rumba Kings is no easy feat. You���re always in charge of the production���the filming, the music recording���but scouring the past for its relics requires good fortune birthed by tenacity and persistence.

Such attention to detail is also evident in the film���s focus on the enduring legacy of Cuban culture on Congolese music. Cuban music is an awesome force in Africa���the soundtrack to the Cuban Revolution���s commitment to African independence struggles embedding itself deeply into the repertoire of many of the continent���s capitals. There is a uniqueness to its presence in Kinshasa, where Congolese music welcomed home a sound that partially found its identity on the rhythms of central Africa. While the West African coast is dotted with enviable interpretations of Cuban music, the Congolese-Cuban sound is exceptionally sweet and deserves a documentary of its own.

Still from The Rumba Kings.

Still from The Rumba Kings.For this record producer, the documentary���s nod to Congolese record labels was short but crucial. Record labels are treated with immense suspicion in the overly moralized Western imagination, but they are the key business engine and vision behind memorable cultural eras. Music needs money and strategy.

That none of the labels featured in the film���the most major record labels in Congo at the time���were owned by Congolese is unsurprising given the nature of capital in the country, but also an important revelation of a vestige that persists today perhaps more than elsewhere on the continent. West Africans owned mega labels like Syllart, East African governments nationalized their music, North Africa���s imprints were mostly all home grown. If, as the documentary says in its promotional slogan, ���Congo���s real treasure does not lie underground,��� it begs the question why the nature of ownership follows a similar structure to the extraction of its mineral wealth���a question the documentary could���ve posed with investigative vigor.

While the figures interviewed are a star list, the film���s insistence on tracing the story through a series of characters and voices rather than developing a small cadre of central characters weakens the transmission of intended feeling: building an endearing emotional attachment to Congo via a few central characters. The Guardian���s short, viral documentary on Somali music from the 1980s is a fine example of this approach.

Rumba Kings also could have dedicated space to the deep roots of Congolese music to discover where the prowess, melodies, and rhythms were born. Some of the most stellar Congolese melodies in Brazzaville derive from ancient folk traditions of smaller towns and villages deep inland, where many musicians migrated from. There is a deeper level of understanding Africa���s relationship with sound that we often ignore. As an Asian, it is the same as tracing the roots of the endlessly diverse cuisines of my home continent, where the trail leads to unsung master chefs in the hinterlands where few venture.

Perhaps the most lamentable aspect of the documentary, for all its good intentions and efforts, was what was left out. It is the same coverage that is neglected in endless columns, articles, analysis pieces, and album liner notes about contemporary African history. What happened? If we���re going to celebrate Congo, its music, and this rich era when everything seemed to be going right, when Zaire hosted music festivals, bands, and boxing tournaments from around the world, when the guitars looked so fresh like they were made in Kinshasa itself, to the dire situation Congo and other African states find themselves in today, we should be compelled to ask what happened? There was no mention of what stripped African countries like Congo of their ���golden era,��� or the energy and exuberance of independence that ushered in a cultural epoch that will be spoken, covered, and featured for generations. A small mention of the manufactured debt crises and structural adjustment, the scars of which are so visible and still bloody on the continent, goes a long way. Without exploring this era of the recolonization of Africa, as Thomas Sankara put it, one unwittingly perpetuates a fallacy that Africans cannot govern themselves, and any abundance that reaches African societies will be short lived.

An issue that affects all African-focused documentaries, not Rumba Kings in particular, is one of control. Distribution of Western documentaries is too tightly controlled and rarely, if ever, finds its way anywhere outside Europe, North America, and maybe Australia. A quick glance at the film festivals screening Rumba Kings has only Brazil as the sole global South audience. This is not a failing of this film in particular of course, but a scathing indictment of the arrogant, incentous nature of the documentary film industry. Who are these documentaries made for? There���s no doubt Rumba Kings is made for a Western audience. Will anybody in Africa or Asia, where 80 percent of humanity lives, be privy to its insight? Music is available worldwide, why is this mostly available at film festivals in European cities that most of the world risks drowning in the Mediterranean to reach?

Lastly, viewers should be cognizant that this was supported by the Africa Museum in Belgium. The museum underwent a $67 million revamp to clean its crass colonial image and depictions of Africa within its walls. Its support for films on King Leopold���s former fiefdom appears to be part of its ongoing mission to paint over its lamentable image with storytelling of such nature, rather than, say, spending $67 million in some form of restitution to the two Congos themselves.

Nevertheless, the subject matter remains infallible and Rumba Kings is a tireless and commendable effort, and a timely, solid case for Rumba���s designation as the world���s latest protected cultural heritage.

November 9, 2021

Haiti’s fire this time

Image credit RNW.org via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

Image credit RNW.org via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. Haiti is going through hard times. From the assassination of a sitting president to an earthquake soon after, preceded by years of economic stagnation and devastating natural disasters. In this episode of AIAC Talk, we chat to Pooja Bhatia about the roots of Haiti���s manifold crises. Pooja Bhatia is a writer and has written about Haiti for outlets such as The London Review of Books and the New York Times.

Though it may seem like Haiti is just a country down on its luck, we chat to Pooja about how the decay of its institutions and the erosion of its sovereignty are the result of centuries of foreign interference���first from France, its former colonizer, and now from the United States, a neocolonial power. Yet, despite the doom and gloom, are there signs that Haitians are collectively mobilizing for a better future, harnessing the legacy of its profound revolutionary past?

Listen to the show below, and subscribe via your favorite platform.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/16907ebc-36ee-48f0-bb9a-4656fba10739/aiac-talk-on-haiti.mp3African indigenous religions and queer dignity

Praying by the waters at Bar Beach, Lagos. Image credit Ethan Zuckerman via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

Praying by the waters at Bar Beach, Lagos. Image credit Ethan Zuckerman via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0. Introduced in 2021 and currently being pushed through the Ghanaian parliament, the ���Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill,��� has led to justified global outcry. The outcry is prompted by the fact that the bill is explicitly intended to ���proscribe LGBTQ+ activities,��� thus criminalizing queer people in the country. Ghana has become just the latest African country to confirm the fact that there are widespread anti-queer attitudes on the continent. Crucial to debates about this widespread anti-queer attitude is the question, what could be the source? In other words, why does the continent appear to be so anti-queer?

The claim that being queer is un-African, un-Christian, or un-Islamic, has been met with strenuous arguments that show the contrary. Those who argue that being queer is not un-African often point to how queer life has existed in many African indigenous societies. Those who argue that being queer is not un-Christian or un-Islamic, meanwhile, draw from theological ideas that enjoin nondiscriminatory ways of encountering the other. Moreover, it is often argued that colonialism is a main source of anti-queer attitudes in Africa, as evidenced by colonial laws which are still being used to persecute nonbinary people in the continent.

What seems missing in these debates, however, is a frank engagement with how some dynamics of African indigenous cultures may be an important culprit in such anti-queer attitudes.

The reticence to engage African indigenous cultures is quite understandable. Modernity has hardly had a good word to say about African cultures. As a result, the study of Africa now seems to be, in a sense, a mission to salvage the battered images of African cultures. This mission seems to enjoin that nothing should be said that portrays African cultures in a bad light. The question of how to speak critically about African indigenous cultures without continuing the racist and colonial baggage that has informed the study of Africa in the past���of how, as Achille Mbembe puts it, to speak rationally about Africa���is still dicey. Hence the reticence in assessing how indigenous cultures may promote anti-queer attitudes.

Mercy Amba Oduyoye, a Ghanaian feminist scholar of African religions, was among the first to see a connection between some dynamics of indigenous cultures and anti-queer attitudes in the continent. According to Oduyoye, Africa���s homophobia may be rooted in the desire for children, a desire that often leads to the stigmatization of childless women���especially married, childless women���in many African societies. Before Oduyoye, some male African scholars of religion, such as the late John Mbiti from Kenya and B��n��zet Bujo from the Democratic Republic of Congo, had read this desire for children as only normal. Mbiti argued that the desire for children was linked to the hope of becoming an ancestor, while Bujo argued that this desire for children could be seen as foundational to the African notion of community. For Bujo, because community is prized in Africa, there is an unavoidable need for the triad of man, woman, and child(ren). The childless and the homosexual, the argument goes, are threats to this salutary vision of life centered on the growth of community.

These men saw in this narrative a way of life that was salutary, but Oduyoye saw a way of life that was hellish, not only to the childless woman but also to queer Africans. In the hands of Oduyoye, therefore, patriarchy joins with homophobia to sap the life out of those who do not conform to societal expectations. Because they are seen as threats to the well-being of society, they are hounded. Here, the hounding of women and the hounding of queer people are linked, and one cannot be addressed without the other.

While Oduyoye has traced anti-queer attitudes in African indigenous cultures,�� Nigerian American Harvard Divinity School professor Jacob Olupona has recently argued that these African indigenous religious cultures are foundational to the continent���s major religions, including Christianity and Islam. If this is true, then it is important to take seriously the proposal that an African indigenous philosophy may underlie how practitioners of these religions think about queer people. Even though colonialism created laws that are used against queer people today, and despite the fact that most devotees of Christianity and Islam in the continent are considerably anti-queer, this attitude may not have originated only with forces that came to Africa from elsewhere. Perhaps we should think of outside forces such as Christianity, Islam, and colonialism as building on a latent dynamic in indigenous cultures. Thinking about anti-queer attitudes in this way may alert us to the fact that the struggle for queer dignity is not just an activist one or one that should focus on Christianity, Islam, or colonialism alone. This struggle should also engage dynamics of indigenous religious cultures and bend them towards the humanistic visions that are believed to be at their core.

November 8, 2021

Sudanese women on the front lines of the resistance

Image credit Rita Willaert via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

Image credit Rita Willaert via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0. There is nothing more difficult than losing a child. There is nothing worse than losing our children as a result of treachery, ignorance, crime and short-sightedness, and this is what is happening in Sudan now. Dozens of young men and women are being killed by the bullets of the Sudanese military.

In the midst of this violence, it is important to acknowledge the contribution of the women of Sudan to the country���s civil transition.

Since the revolution���s instigation, Sudanese women brilliantly coordinated and effectively participated in the overthrow of the Bashir regime, with the proportion of women in the demonstrations in 2018-2019 estimated to have been at least 60%.

In the mid-1990s the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) stated that Sudan had more than 35% women-headed households. Fast-forward more than 23 years, the number of women-headed households in Sudan has probably doubled, if not more. While doing the lion���s share of care work and providing for their families, women have also, since 2019, made incredible strides to assert their agency and presence within households and public spheres. If this coup is allowed to last, Sudanese women will be dragged into a very dark corner.

We all know that the transitional period of the Sudanese revolution has not been ideal, and we are fully aware of the number of challenges and constraints that occurred, but we also fully understand the root causes of these challenges, starting with the disproportionally designed political agreement, which allowed remnants of the Omar al Bashir regime to remain in power. This faction of the transitional government has never been interested in anything other than keeping Sudan captive to the same cycles of violence and poverty that have long been hindering Sudan���s opportunities to achieve stability and peace.

And although there has been no clear progress on legal and institutional reform towards gender equality in Sudan, we cannot deny the achievements made by the Sudanese people, women and men, throughout the transitional period. In particular, the success of Sudanese women in increasing and consolidating their presence in public places.

Women founded sports teams, involved themselves in creative activities, and paved the way for professions that had been preserved for men during the previous regime, such as traffic police, technical professions, car mechanics, carpentry and public car driving. Sudanese women’s voices rose on all platforms, and through their participation in peaceful protests and marches, they demanded their human rights, while spreading awareness about the rights of women and girls.

Since the revolution���s instigation, Sudanese women brilliantly coordinated and effectively participated in the overthrow of the Bashir regime, with the proportion of women in the demonstrations in 2018-2019 estimated to have been at least 60%.

Now, at this critical time in Sudan’s history, the women of Sudan are standing at the front lines, fighting once again to prevent their country from slipping back into dark times.

If this military coup succeeds in taking over the country, Sudanese women will face another cycle of obscurity and violence that may be much worse than the era of Bashir, especially since no legal reform has taken place in the country. Sudan is still not a member of CEDAW, and Sudan has not signed or ratified any of the international protocols or instruments that could have improved the status of women. In addition, Sudan still has active laws that allow gender-based violence and impunity for perpetrators of violence against women and girls.

Moreover, women continue to be arrested for so-called ���moral transgressions,��� despite the repeal of the Public Order Law in Sudan. Punishments are harsh, including flogging, imprisonment and, in some cases, execution. Poor women and girls, internally displaced people, refugees, and those living in areas of armed conflict areas continue to be the most vulnerable to these penalties and organized violence.

A militant militarized system can only exist by eliminating any glimmer of hope towards accountability and the rule of law.

The reasons Sudanese women took part in the revolution in large numbers are the same reasons they are now part of the resistance against this treacherous coup. We are well aware that any military government will seriously jeopardize the rights, security and safety of women, especially with these fundamentalists and warlords at the helm.

The environment created by the presence of armed groups in civilian areas has time and again been accompanied by increases in sexual and gender-based violence. Already there are reports that a group of soldiers representing the coup stormed a hostel for girls in north Khartoum, and assaulted dozens of the female students there.

Sudanese women are well aware that their access to basic human rights and justice are conditioned upon the presence of a civil and democratic system of governance that respects women���s rights and humanity. Only under such a government can women be part of legal and political reform processes that will contribute to bringing about meaningful change. Until then, the women of Sudan remain on the front lines to resist any action that pushes them back or diminishes their humanity and the value of their contribution to society.

Darra

Image credit Andrew Garton via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Image credit Andrew Garton via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. Where I grew up you hardly heard someone say ���dad��� or ���daddy,��� it was always Derrie, Derra or Darra. We called my father Darra [a colloquial name for daddy on the Cape Flats]. His name was Raymond aka Boeta German or Boeta G; literally because he always looked stern. I used to think it was because of his light skin, until someone in my family explained the naming. Trust Capetonians to give you a nickname. He had a friend called slang [Afrikaans for snake] because he was skinny. One other friend was called perdekop [horse’s head]. For years I thought maybe it was because he resembled a horse. I found out it was because he was always placing bets on horse races.

On June 16th 2021, my father had been dead for 16 years. I never felt a need to write about it. His death was so swift and the funeral even faster. Then, recently, I heard a song he liked so much and started thinking about him and our relationship.

He was a complex man. Quiet when sober. Loud and angry when drunk. For years I dismissed him so unfairly for this. I never processed his traumas and, as a man of his age, social standing, and skin color, what this all meant to his life. He started working when he was 12 out of necessity. He kept working and ended up on fishing trawlers. He did so much. He was in construction, cleaning, and fish hawking. He was always skarreling [hustling]. He was the original skarrelkind.

He was also so generous. It was small things I remember: buying a bag of oranges then sharing with the whole Argo Way off of Galaxy Crescent in Mitchell���s Plain. Or how took me and my sister to the opening of Westgate Mall and bought us goema hare [candy floss] and held us in each of his arms so we could see above the crowd.

I don���t think he ever recovered from an assault by the police. He had bought a Mercedes sedan from his boss at the time. The company was the biggest name in construction in Cape Town. One day, he was pulled over by the police and beaten up and asked how a Hotnot [a slur for colored South Africans] could be driving a Mercedes. His boss drove from Newlands, a rich white suburb along Table Mountain, to bail him out and prove he sold him the car; he was making weekly payments.

For a long time I just dismissed him as an angry drunk. He really wasn���t. He was gentle but had no real outlet for his trauma. At the time who did? The men drank and kept drinking. They worked tough jobs with low pay, and still tried to hold back any vulnerable emotions about it. All they knew was aggression.

He calmed down with the drinking in his last years. He couldn���t keep up anymore. I saw more of the real him during this time. I saw the man who taught me to ride a bike; who bought a bike from a postman so I could have the best bike in our street. I saw the man who called in sick from work so he could take us to the Spineview Primary School fair���a local carnival���so we could ride on the Big Wheel. I saw the man who took us to Kalk Bay and taught us about fish and how to cook it well and properly. He actually taught me about food sustainability long before it was fashionable. Insisted we eat the whole fish. No waste.

He was also the first person I was really open with years ago about my sexuality. We would always watch movies and TV shows together. I made a casual remark that I was like one of the characters; all he said was ���Ok, that���s good then.��� It was all I needed from him to never feel shame ever again. He loved music so much. I get the repeat play habit from him. He would ask us to rewind his Engelbert Humperdinck and Patsy Cline tape cassettes over and over for him. He had great taste. He wore bold shirts, and could langarm [a South African dance form] his way around a dancefloor like a pro at any function we attended. He was the problem solver too. He came to so many people���s rescue. To this day people still talk about how Boeta G helped them.

He really loved us and tried so hard not to let alcohol consume him, though it did many times.

See, he was more than the bad parts of him.

He was my Darra.

November 3, 2021

Criminal justice for the rising middle class

Image credit Gilbert Sopakuwa via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Gilbert Sopakuwa via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. The last 18 months have spurred a turnaround in the public discourse around policing in South Africa. South Africans have long decried the ineptitude of their police service. But the killings of Collins Khosa and Nathaniel Julies amidst the eruption of the popular uprisings against police violence in Palestine, Nigeria, Colombia, the US, and neighboring eSwatini have raised questions about whether South Africa, too, might have a problem with police brutality.

In her new book Can We Be Safe? The Future of Policing in South Africa, Ziyanda Stuurman sets out to bring the public face-to-face with the realities of the post-apartheid criminal justice system and chart a course to a better future. Drawing on her training in development and security policy, Stuurman details the many failures, brutalities, and inequities of the country’s police, courts, and prisons.

Written in a conversational style, Can We Be Safe? models itself as a guide to criminal justice for the rising middle class. Opening with a reflection about the author���s own disparate experiences of safety in Gugulethu and Sea Point, Stuurman points out that, while South Africans are united in their mistrust of the police and their fear of crime, it is often the voice of the least victimized who figure most prominently in conversations about crime and policing.

The outsized role of the middle class, she contends, distorts crime policy, encouraging punitive measures without regard for their efficacy or impact on poor and working people. Covering topics ranging from the Khayelitsha Commission, anti-gang operations, and IPID, Stuurman offers an accessible entry into the recent academic and policy literature on policing and criminal justice, especially that originating from those NGOs and think-tanks focused on criminal justice reform like the Institute of Security Studies.

But Can We Be Safe? goes beyond the usual call for reform, arguing that South Africans will only be able to secure true safety for all by pursuing police and prison abolition. Adapting literature tuned for reform to the task of abolition is a difficult needle to thread. And it is one that Can We Be Safe? does not always manage successfully.

A charter for abolition?There are times where Stuurman���s arguments are at cross-purposes. In certain moments, Can We Be Safe? seems to take up a straightforward abolitionist position. She remarks on the futility of reform, calls for more social spending to end poverty and inequality, and advocates for decriminalizing drug use and sex work. At the close, she puts it explicitly: ���We need a big, bold abolitionist future.���

But in other moments, Stuurman seems less sure. When discussing policing in Cape Town, she argues against deploying the military to fight gang violence, but also calls for ���more detectives��� and more ���crime intelligence resources��� to be deployed to poor areas. Closing her chapter on South African prisons, she shies away from advocating for abolishing the institutions altogether, instead asking somewhat limply: ���Should these institutions still exist in the way we know them now?��� At times, Stuurman���s equivocation turns her prose into a logical muddle. In one instance, she calls for a more equitable distribution of police resources to fight gang violence before adding that more resources won’t necessarily lead to safer communities.

By the close of Can We Be Safe?, Stuurman seems to have settled on the abolitionist position. She argues that ���reform has only gotten us so far,��� quotes many prominent abolitionists favorably, and speaks of the need to create ���communities of care,��� a key abolitionist concept. But even this is tempered by her identification of the Freedom Charter as the preferred model for abolition in South Africa. The desire to anchor abolition in South African history is understandable. But it is equally clear that, while the Freedom Charter is an admirable and progressive document, it is not an abolitionist one. In fact, it explicitly calls for imprisonment ���for serious crimes against the people��� and envisions a future where ���the police and the army��� exist as protectors of ���the people.���

One can only speculate why Can We Be Safe? is intent on squaring the circle of abolition. After all, Stuurman seems more comfortable with police and prison reform. Her argument is most cogent when denouncing militarization, discrimination, and police corruption���in short, all those topics that have been the focus of liberal police and prison reformers. Indeed, Can We Be Safe? is one of the freshest calls for police reform to appear in the South African public sphere in many, many years.

The amnesia of reformStuurman���s decision to lean away from her reformist roots is puzzling. Perhaps, it stems from misunderstanding that abolitionists only support reforms that will roll back and eventually eliminate the power of police and prisons. Perhaps, it just seemed pass�� to argue for reform in what some are dubbing ���the age of abolition.��� (Reformism, it���s important to note here, is no less principled a position than abolitionism, though the two are often at odds.)

Or perhaps, it is because invoking abolition allows Can We Be Safe? to elude a thoroughgoing reckoning with the recent failure of police reform. While much of the book deals with the disastrous aftermath of the post-1994 reforms, it has less to say about the roots of that failure. When discussing the reforms of the 1990s, Stuurman argues that the efforts to bring the new SAPS in line with human rights principles floundered due to institutional and societal inertia. In short, too many officers committed to ���the old way��� of doing things. But the fact that there was institutional inertia gives us little sense of why inertia was allowed to persist. Or for that matter why the African National Congress (ANC), a movement powered in large part by popular antipathy for apartheid policing, would embrace law-and-order rhetoric at the height of its power?

In considering this puzzle, it is helpful to remember that South Africa’s experience with crime and policing is not unique. The turn towards ���law-and-order��� is a global phenomenon, visible everywhere from Brazil to the US, Jamaica to Nigeria, the UK to Indonesia. As social theorists Stuart Hall and Ruth Wilson Gilmore have argued, these punitive turns are key ways states and ruling elites have managed crises inherent to capitalism. Panics over crime weld the propertied into durable electoral constituencies despite austerity. Police and prisons offer investment opportunities, provide jobs for the working class, and contain the restless, often racialized, underclass.

By the time the ���new South Africa��� emerged, the playbook of ���policing the crisis,��� as Hall puts it, was already well in place (and indeed, had already been mobilized during the late apartheid period with some success). Faced with a newly unipolar world-order with the American empire at the center, it became incumbent on the ANC to prove that its youthful dalliance with communism was in the past. Fidelity to core capitalist principles like free market exchange, private property ownership, and fiscal and monetary discipline became the price of national liberation. Private and for-profit police became the safeguard of property, while the state police were charged with managing the disorders of a profoundly unequal and traumatized society.

As the post-apartheid ground on, it became clear that the aspirations of most South Africans were incompatible with a global capitalist system that is allergic to market intervention and wary of wealth redistribution. Escalating coercion became essential to dealing with this contradiction and making sure it didn���t erupt into open crisis. This is a global pattern most visible at Marikana, but no less present in the murder of Julies or Breonna Taylor. It is a pattern that ensured police reform failed, and will fail again.

The nation and the melancholy presentRead in this context, Can We Be Safe���s turn to the Freedom Charter as a blueprint for the future speaks to a kind of left-liberal melancholia. After all, we are living in the future of the Freedom Charter. It is a future where the wild hopes of national liberation were shipwrecked on the shoals of the global capitalist system.

Faced with the screaming misery of the present, it is little wonder that South African progressives, cloistered as they are in universities, think-tanks, and NGOs, find themselves looking to the mass democratic movements of the past for solace and inspiration. But it is crucial that one sees that past with absolute clarity, understanding the limitations of those ���freedom dreams��� along with their strengths.

To do so would allow the left to set aside a post-apartheid national culture that is so thoroughly exhausted. It would allow it to see those struggles against police violence elsewhere are not just similar struggles. It is, in fact, the same struggle���from Marikana to Minneapolis, from Minneapolis to Mbabane.

Power to the People

Children cross a stream of sewage in Soweto-on-Sea, Port Elizabeth. Image credit Mkhuseli Sizani.

Children cross a stream of sewage in Soweto-on-Sea, Port Elizabeth. Image credit Mkhuseli Sizani. This episode of AIAC Talk is a replay of the launch of issue 78 of Amandla! magazine, a progressive South African publication devoted to advancing radical left perspectives for social transformation. Since 2020, Africa Is a Country has been fortunate to be in partnership with Amandla! (the Nguni word for “power”) and is pleased to expand the range of content shared across both publications.

The issue was published on the eve of South Africa���s local government elections, which happened on November 1. While South Africa���s political class has run out of ideas to address the manifold crises afflicting the country���s municipalities, this issue looks at the many ideas for change amongst South Africa���s progressive forces, as well as the organizers carrying out some of them. At the launch, Amandla! editorial collective member Shaeera Kalla sat down with issue contributor Ayabonga Cawe for a wide-ranging conversation about municipal decay and what can be done about it.

Listen to the show below, and subscribe via your favorite platform.

To read the whole issue, download your copy here. Select articles have been republished on Africa Is a Country.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/baa77d64-8938-44b3-aa4e-c6e19e385b16/aiac-talk-amandla.mp3Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers