Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 128

May 10, 2021

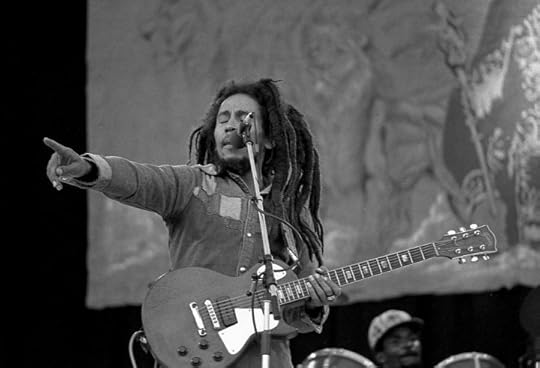

Farther on from Zion

Harajuku, Japan. Image credit Hideki Watanabe via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

Harajuku, Japan. Image credit Hideki Watanabe via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0. Toward the end of his earthly life Bob Marley spoke frequently about death. Such talk was not unusual. He freely shared his views on a fast-approaching judgement, the consequence of a world unraveling because of what he called ���man-made maniac downpression.��� As with most things his vision on death was biblical. Doom hovered low over humankind. The only rescue was salvation.

From 1979 however there was a new urgency to his talk about death. He claimed he could not die. He was, in his words, a “life angel” blessed by His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie I, his Lord and savior, Jah Rastafari. Death was the wages of sin. If you love Jah you will live eternally. ���Love Rastafari and Live,��� was how he sometimes autographed records for fans.

This peculiar take on immortality was a product of the religious space of his upbringing in a deeply Christian Jamaican family and especially his acceptance of Rastafari, the teachings he had absorbed and repeated since his early twenties. Marley���s views baffled many an interviewer eager to draw sooth-saying insights from one of the world���s biggest celebrity musicians. His fame grew each year and by the late seventies the appetite for Marley quotes increased. It was in interviews that he expanded on his views of death. ���I don���t believe in death, neither in flesh or in spirit,��� he told Vivienne Goldman in the summer of 1979. ���Death does not exist for me. I truly know God. He gives me this (life) and my estimation is: if he gives me this why should I take it back? Only the Devil says that everybody has to die.���

It was not a strange position to hold in Jamaica where questions of life and death, godliness and redemption have always carried people through seemingly unending difficulties. When the island got the tragic news in January 1981 that the most triumphant story of its troubled independence years may end with Bob Marley���s fatal cancer, some Rastas claimed that if Bob Marley died it meant he was not a true Rasta; a claim that revealed how much criticism pop stardom brought him back home.

Marley���s own attitude to eternal life was tested with his illness. His desperate fight to beat the melanoma cancer that polluted his body, depositing its cells in his brain, lungs, and liver, by taking a controversial���and painful���alternative treatment at a clinic in Bavaria, seemed a contradiction to those who took his words literally. But it was not. Bob Marley held onto life more than anything else. His lyrics���again more so in his later years���oscillated between laden admonitions on the end of days and a joyous celebration of life as the great gift of Jah.

It was these contrasting aspects of Bob Marley that have in fact lived. After he passed forty years ago this month there seemed little likelihood that he would be forgotten���definitely not in Jamaica where he was given the country���s greatest state funeral that was more a carnival than a mournful wake. To those who adored him in Jamaica, Marley would always be seen as supernatural. A country boy from the faraway district of Rhoden Hall in St. Ann parish���so profoundly nestled in the bush that its residents looked giddy whenever they saw the marginally wider roads of nearby Brown���s Town���Marley came of age in the narrow galaxy of West Kingston.

Everything that was incredible and incongruous of the Jamaican experience was bound up in Bob Marley���s life. All of it, from the jutting rocks that bruised his toddler���s feet to the obscuring high-rise buildings in downtown Kingston fed his creative impulse which produced its own Jamaican uniqueness. His lyrics and style were sown into the popular culture of the place from before his head began to sprout its young bud locks. There was no chance whatever that he could possibly be forgotten there. That Jamaicans, on the days after his death was announced, preferred to listen to his crackling 45s from a more innocent 1960s than his slickly produced international hits (songs like ���Chances Are,��� a 1968 lament on loss, death, and survival were in regular rotation in those introspective months of 1981) revealed how deeply his story blended with their own.

There was always more than one side to Bob Marley. Having had numerous versions of his name by his late teens (Nesta, Lester, Robbie, and others he would sooner forget) he adapted different personas in his years of fame: Natty Dread, Skip, Joseph, Berhane Selassie, and The Gong. For Marley these changing references allowed him to make room for himself in disparate spaces. Most of all the different reflections of his personality helped him to rise up from street-level constraints and break into the international mainstream. When Jamaica existed in that mainstream it was seldom regarded as more than an aching smile on a coastline. Bob Marley became larger outside of the island because he not only had the greatest trust in his talent, but because he knew what it needed to grow. Chance, luck, and opportunity coalesced at the right moment for him and he took what he could from them to build his fame. As he told a reporter in the early seventies, his goal was to take reggae music international and ���become known.���

Four decades after his passing Bob Marley is the most recognizable musician in the world. His songs, it is fair to say, are played every day at some time in some place. The rhythms are remixed, cut, diced, and seamed into other musics and the lyrics come back to us in ever-expanding forms. Taken whole they are integrated into whatever mood is needed: moral balance, religious temperance, love, anger. More often they are revered as rebellious anthems, disaggregated for graffiti, t-shirts, posters, memes, and consumables. For a man who was once chastised for his refusal to smile, it is his wide, warm grin under a canopy of dreadlocks that is the most recognizable feature of this rebirthed Marley. We see his face on walls and bodies. It is a universal face frozen in glorious youth. His bronze skin, high cheekbones, emphasized by hairless cheeks, a sharp nose, thick lips, rounded forehead and lined teeth all bear reflections of one group of people or another. Bob Marley became appealing in the post seventies era because he seemed safe and fit for purpose. Whatever he is recruited for���hedonistic endorsement or to inspire marches���people can find what they want in him.

This is only part of his larger relevance. Bob Marley���s afterlife is the product of an incredibly capacious marketing machine. The release of his posthumous Confrontation album in 1983 created excitement among reggae fans. It was nothing near the astonishing impact of the following year���s blockbuster greatest hits album, Legend. From its cover photograph taken in London in February 1978 of a wizened Marley in philosophical pose, to its expertly chiseled song selection, Legend was the first trumpet of a new Bob Marley career.�� Though the album unfailingly enrages the hardcore fan for its militant economy and quiet on Marley���s strident black consciousness to which he remained fervently attached���not one song from Marley���s 1979 pan-African opus Survival appears���Legend has kept new fans coming to Marley since the eighties. Later Island Records reissues aimed to redress the balance. Songs of Freedom, released roughly a decade after his death, was a career-spanning box set that was smartly packaged and curated and went some distance in telling newcomers of the seriousness of Marley and his music. Still it could not achieve the enduring mainstream presence of Legend. Even new generations of Jamaicans born into a world of spitfire dancehall reduce The Gong to his output on Legend.

Above all its grooviness, Legend made Bob Marley an undying musical force���an eternal man. Global youth latched onto the image and his songs which have become the soundtrack for self-conscious discovery. Even those who resent him for eclipsing the tremendous output of Jamaican music���s other kin, have to concede Marley���s endurance. His lyrics remain ballast for the unapologetic political movements of the young and alive, often leading them to other streams.

There has been another consequence of this posthumous fame. Bob Marley has become a commodity used most extensively to advertise a postcolonial Caribbean myth. Backpackers descend annually on Jamaica in search of a pulsating Bob Marley adventure. Tourists take guided tours outside of all-inclusive hotels looking for another version of the same song. Thanks in large part to Marley���s fame, the tropical image since the late seventies includes dreadlocks, ganja plumes, and three-chord bass lines filling the vista between sun and sea. Marley���s more popular songs like One Love are renditioned by every hustler from Maracas in Trinidad to Negril���s seven mile beach stretch. Bob Marley is today part of a generic Caribbean visitor package.

Outside the resort walls, Caribbean youth of various languages and hues wear Bob Marley t-shirts out of adoration for his image for what he represents more than who he was. Marley is for many of them born into a world remade several times since he left it, a modern Caribbean hero with defiant dreadlocks long dispossessed of their fright.

This easy embrace of Marley, whether by foreigners or Caribbean nationals, has always frustrated fans who believe the marketing of the man is a shocking injustice to his purpose. Nonetheless, it is encouraged by those most responsible for keeping his memory alive. A cottage industry exists within and outside of Jamaica that depends on more people being seduced by Marley magic. Marley���s children, all comfortably settled in middle-age now, and with their own musical progeny and personal achievements to draw on, accept the ubiquity of their father���s voice and face as part of the mission of spreading his music. Marley himself may likely have endorsed this type of attention. In his lifetime, Bob Marley enjoyed wearing Bob Marley t-shirts.

The great risk though is not simply that all this commercialism has made Bob Marley a product. Stardom is a force of its own that cannot be easily controlled once released. What is more troubling is that the place and age that made Marley become reducible to a shadowy backdrop on stage left, billowing to the riddim while the spotlight graces the beatific angles of the great man. Documentary films, news specials, hundreds of biographies, anniversary articles, oral histories, and online interviews with those “who knew him best” seek to remind us of the larger world around Bob Marley. Sometimes they do. Yet, too often they strain to reconcile the life with the afterlife shows. Marley returns to us a saint composed of free-flowing homilies, pithy anecdotes, raw originality, and wise asides, less a person than a man for all times. What is lost is a fair reminder that Bob Marley for much of his life was, as one musician who played with him in the early seventies told me, ���just an asshole like the rest of wi.��� By that he meant, Bob Marley was a survivor living day to day roaming as quickly as he could through the shimmers and soft mauve heat of Kingston city.

Marley���s uniqueness was not the mixed color and class origins of his parentage. That is a story as Caribbean as the sea. It is not that he was one of thousands of country children who came to Kingston in the great migration of the 1950s, dazzled by the size and sounds of the capital. It is not even that he was like many of his company���including the greats who helped him along the way, such as his fortitudinous wife Rita, group members Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, and the dozens of singers, musicians, producers, sound system men, engineers, Rasta bredrin and sistren, ballers, rude bwoys, bad men, good men, caretakers, cooks, sufferers, youth, girlfriends, gorgons, and everyday people of Trench Town who gave him food, lyrics, an example, a bed, plenty of herbs and inspiration���an inveterate dreamer who hoped singing would take him out of the burning oppressiveness of the ghetto and make him famous beyond Half Way Tree. It was that he was able to draw strength from all these common experiences to overcome his circumstances.

Norman Manley, a towering political intellectual in the Jamaica of Marley���s youth, once said that talent was only five percent of success. The rest is preparation. In many ways preparation was the mantra of the generation that came of age after Jamaica���s independence in 1962 and which Bob Marley was very much a part of. Everyone was preparing for something. What it was changed several times, but it was always going to be something better than what they were living. By the early seventies, when Marley began to spread his wings, Norman Manley���s preparation became his son Michael Manley���s struggle. Struggle was part of a process. If it did not happen you could not trust the outcome. Marley���s truest gift was that he understood intrinsically the lesson of his era: that preparation, struggle, rehearsal, craft, discipline, were lifelong commitments. The greater the forces aligned against him and people like him in Jamaica the greater the demands of the preparation.

The politics of the 1970s in Jamaica have become as legendary as Marley, even before he left this earth. In its most accessible version, Jamaica was split into two ideological camps. One party, the governing People���s National Party under Michael Manley (in power for the full length of Marley���s international fame, 1972-1980) trying to define and apply an evolving democratic socialism, and the opposition, the Jamaica Labour Party, doggedly led by future Prime Minister Edward Seaga (elected in 1981 and serving until 1989), defending a capitalist model sold to Jamaicans as “nationalism.” They presented two very different visions for the independent nation that the party faithful defended for dear life. The struggle on the ground was not just ideological. The politics exacerbated preexisting distrust and a competition among Jamaicans���from parliament to the recording studios���to be the leaders of their era.

This struggle was the source from which Bob Marley drew his greatest motivation. Much of his catalogue in these pivotal years were songs about the Jamaican situation. Bob Marley, quite simply, cannot be understood outside of the situation of 1970s Jamaica. Not just the politics and the accents but the full ecology of the thing.

That Marley���s songs had wider appeal is part of their brilliance and a reflection of how much care he took in their preparation. It is what is distilled and unsaid as much as what he wailed that captures the debt he owed to his environment. Marley���s lyrical choices were often drawn from the currency of the street Rastafari worldview stitched to borrowings from elsewhere���the familiar with the unexpected���over a carefully sanded rhythm to achieve the intended effect. The Jamaicans who moved in time with his music understood it instantly. They made the Wailers shining stars long before anyone else took notice. They packed the lower Kingston theaters each Easter and Christmas to cheer on their heroes. And Marley, in song, returned the love by singing about them, taking their joint story to the remote corners where they still echo. Long before international fame found him, the Jamaicans he unfailingly called ���my people��� held him up.

The bolder conquest was how he took all that promise and expectation much farther than anyone ever imagined. Or farther than even seemed possible. We would do well to remember that in the early seventies, when Bob Marley and the Wailers and their tireless, talented peers, started their campaigns to take reggae���”the sound of the seventies” according to clever Island Records marketing���to large markets, music news was still spread by short run papers and word of mouth. To shop a record an artist had to show up, everywhere. For Jamaicans that meant hustling for visas, per diems, and bedsits so they could get on the road and stay on the road. Marley���s intense work ethic and a natural discipline sharpened in Kingston���s studios, unwatered football pitches, and Rasta camps pushed him to show up. Of the many stories said about the man over the past forty years, his enormous capacity for long stretches of work and his devotion to the hard labor of creation is the story most consistently told by those who worked with him.

The more he practiced, the greater his talents grew, and the greater his profile. He was seldom in Jamaica; the concept of home became necessarily mobile as he was in constant movement through airports and across continents. He shared with the other giants of the 1970s���from Bowie to Fela, from Stevie Wonder to Jorge Ben���an ability to make art that seeped through boundaries.

Events in Jamaica shaped Bob Marley���s renown repeatedly in his phenomenal seven years of international fame from 1973-1980. The shooting attack on him at his Kingston home in December 1976���a crescendo moment in his biography���and his courage to perform the Smile Jamaica concert days after, enshrined his legend. His valiant return from exile two years later for his set at the One Love Peace Concert, where he brought the two opposing leaders together, gilded him and has become the quintessential moment of hope in Jamaica���s tough 1970s.

His fame by then seemed to deepen a sincere belief�� that Jamaica could be an example to the world. His closing words at the One Love show were, ���this people must set an example for the Earth to follow. This is where Rastaman is first known. And then Rasta would have to unite from Jamaica first before the Earth could be united. So with this unity we shall keep it together and with the help of Almighty God, Jah Rastafari, Emperor Haile Selassie I, we shall overcome.��� It was the confidence of the claim that Jamaica was the center of the world that reveals just how much the country lived within him.

His thoughts about life and death drew on what he had learned and lived. On his final tour, the abbreviated Tuff Gong Uprising 1980, Marley opened every show with “Natural Mystic.” It was a song written in the mid-seventies when Jamaica���s political violence was still ascending. The violence crested in 1980 with the grim general elections that claimed hundreds. “Natural Mystic” in this context was a meditation on that hard reality. The heaviness of the message onstage was counterbalanced with the uplifting encore which invariably began with “Coming in From the Cold,” a celebration of life���oh, sweet life���and possibility in the middle of gloom.

There was a purpose to this arrangement. Everyone, he seemed to say, had to face the reality of death. But life does not end with it. Those who are living must carry forward the departed to ensure they live forever. As he made peace with his transition from this realm to the higher region of Zion, Bob Marley put his faith in what he was leaving behind: his children, his business empire, his musical legacy, Jamaica, and most of all the monumental canon he had completed by just 36.

People are kept alive by remembrance. Remembering Bob Marley means recalling the journey from his past to his present. To consider Bob Marley today demands we look back across that distance to the place and age that brought him to us, and do as his people did when they laid him to rest at the spot where he first breathed life���listen to his music, grow strong, forget your troubles, and dance.

May 9, 2021

Movement of Jah people

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Image via Wikimedia Commons. On Tuesday, May 11, it will be 40 years since legendary musician and Rastafari, Bob Marley, passed away. It���s hard to even begin to summarize the complicated legacy that Marley left behind. While no one questions the brilliance of his musical output (achieved primarily with his band, The Wailers), it is the fact that Marley wasn���t just a musician that leaves us missing not only his eclectic sounds, but wondering about what would have become of his political and cultural trajectory if not for his untimely passing at the age of 36.

Marley achieved an iconography befitting only the legendary, able to transcend the boundaries of the aesthetic, political, and spiritual in his music and life. But this was not without the contradiction which always befalls the greats. As renowned historian of the black Atlantic Paul Gilroy writes, ���Marley���s stardom also makes sense in the historical and cultural context provided by the end of Rock and Roll. He was the last rock star and the first figure of a new phase identified as the beginning of what has come to be known as ���world music���, a significant marketing category that helps to locate historically the slow terminal demise of the music-led youth-culture which faded out with the embers of the twentieth century.���

There was, on one side, the Bob Marley that emerged as a revolutionary symbol, a representative of the Third World that advanced a critique of global capitalism and the imperial domination it depended upon. Especially in the 1960s and 1970s, a real and palpable belief existed that the anti-colonial struggle in the periphery and the militant struggle against white supremacy in the imperial core would be exploitation and oppression���s gravediggers. As Marley declares in War, ���Until the philosophy which hold one race superior, and another inferior, is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned���everywhere is war.��� Naturally, with an upbringing in this context and explorations in Rastafarian Ethopianism, Africa loomed large in Marley���s life. As AIAC Talk co-host and website founder Sean Jacobs explains, ���Bob Marley, like many other Rastas, shared a desire to visit the African continent or, if possible, to live there.��� Most etched in our memories, was his performance at Zimbabwe���s Independence Day celebrations in 1980 when British and white minority rule ended.

There is also a Marley, one arriving posthumously, that becomes sanitized, commoditized, and packaged for mass production. This is the Marley coinciding with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of history. Mobilized as the poster boy for liberal multiculturalism, the Marley of ���One Love��� became ���an affecting soundtrack to essentially boring and empty activities like shopping and getting stoned��� says Gilroy. Reggae, once a source of not only creative expression but also a spiritual outlook and emancipatory posture, became watered down as just another genre of music for consumers to select from like they do items on a store shelf. What became of the movement of Jah people?

The story of the rebel disarmed is by now familiar to all of us. On the one hand, we can appreciate Marley as the last rock star, as not too far away from us in history for him to still present us with a usable past. But on the other, if he really was the last rock star, how do we make rock intelligible for a post-rock age? Joining us on AIAC Talk to discuss the life and legacy of Marley, are Matthew Smith and Erin MacLeod. Matthew is a professor of history and director of the��Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership (previously, he was professor of history and head of history and archaeology at the University of the West Indies in Mona, Jamaica). He is also co-editor of the new Jamaica Reader, forthcoming from Duke University Press. Erin writes and teaches on identity, culture, class race and geography, and is the author of a book about Rastafari who returned to Africa, Visions of Zion: Ethiopians and Rastafari in the Search for the Promised Land (NYU Press, 2014).

Stream the show on Tuesday at 18:00 in Harare, 17:00 in London, and 12:00 in New York on��YouTube.

It was Marx���s birthday last week, so we provocatively asked if Africans need him. We were joined by returning guest Annie Olaloku-Teriba and Zeyad el Nabolsy to debate and discuss the questions that always come up whenever Marx is mentioned���was he Eurocentric, is he still relevant, and so on and so forth. On whether Africans need him or not���it could be the other way round! To find out why check out the episode, it is now available on our��YouTube channel. Subscribe to our��Patreon��for all the episodes from our archive.

May 8, 2021

The problem with South African football

Image credit Media Club South Africa via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Image credit Media Club South Africa via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. The drive to professionalize all sports in South Africa has killed off community spirit and the sporting rivalries that built social cohesion in the country. The National Department of Sport, Arts and Recreation lacks the imagination, knowledge, and passion to rebuild sport in this country. They have bought into the apartheid ideal of exclusion and exclusivity.

The March 28, 2021, 2-0 loss to Sudan booted South Africa���s national football team out of the grand African Cup of Nations soccer spectacle to be held in Cameroon in January 2022. South Africa may still not qualify for the FIFA World Cup scheduled for Qatar in 2022. The comparisons between the hapless national soccer team, known as Bafana Bafana, and the national rugby team, the ���all-conquering��� Springboks who are current world champions, flooded social media. The British and Irish Lions will visit South Africa in July and August and the patriots on social media crowed about the drubbing the Lions will receive at the hands of the Springboks, advising SAFA (the body that controls football) and Bafana Bafana to keep their notebooks handy. Without batting a historical eyelid, patriotic rugby lovers reflected on the ���proud history��� of Springbok vs British Lions clashes, which started 135 years ago in 1891, despite the fact that most of matches were played by all-white teams representing South Africa.

And therein lies the burning rub: Bafana Bafana has no heritage. Bafana Bafana has no history. They are a new creation, formed out of the euphemistically termed ���unity talks��� of 1991 and 1992 between the various football bodies that operated under apartheid. Despite being a founder member of the Confederation of African Football (CAF) in 1953, South African soccer was out in the cold from CAF by 1960 due to the country���s apartheid policies (FIFA suspended South Africa in 1961 and expelled it in 1976).

Springbok rugby, on the other hand, enjoyed the full support of the International Rugby Board (IRB) and tours to and from South Africa to place throughout the apartheid era. As late as 1980, the British Lions toured South Africa. Ireland still toured South Africa in 1981 and England did in 1984. It was also during this period that Errol Tobias, a black (and coloured) rugby player who was a member of Springbok rugby teams throughout the 1980s, was paraded before the world as ���proof��� of South African Rugby���s dismantling of racism. He made his test debut against Ireland in 1981. The IRB even sanctioned a World XV tour of South Africa to celebrate the white South African Rugby Board���s centenary in 1986. In the world of rugby, the Springboks can proudly reflect on their heritage that dates back to first international contact in 1891, and boast about their 1906 tour of the British Isles; the tour that gave the Springboks their name and gave the world the sad tale of James ���Darkie��� Peters, a player of West Indian/Jamaican descent, who so offended the Springboks that they refused to take the field against him. Only the intervention of a high ranking politician persuaded Paul Roos and his men to take the field against Devon County.

Professional soccer in South Africa, has always been a shadow child of apartheid sport, playing the National Party game of multinationalism by organizing normal sport in an abnormal society. Long before Nelson Mandela and the ANC pushed for South Africa to be allowed back in international sport in the 1990s, South African soccer gave sport the face of legitimacy by proclaiming integration despite apartheid policy.

In 1982,�� two black soccer clubs, Iwisa Kaizer Chiefs and African Wanderers, played each other in the Mainstay Cup final at Ellis Park in front of desegregated bleachers, smearing muck all over the face of the anti-apartheid sports movement. South African soccer, and especially its professional affiliates, never really embraced the non-racial sports movement organized by the South African Council on Sports (SACOS), preferring to court the ideology of multi-nationalism. The latter racial gimmickry served the policies of apartheid more than it served the game of soccer. As it turned out, the game expanded its footprint, but it never grew. At the root of it all was, of course, the money that huge soccer crowds promised. It was a strange situation of apartheid at club level, but integration and ���normality��� at a professional level.

Soccer in South Africa was insular during the apartheid era, and it remains insular today. The ideological inbreeding at the top level, has seen the shadows of who controls South African soccer deepen and grow ever more foreboding. South African soccer has no answers, and without a history with the worldwide controlling body, it has no future.

Rugby on the other hand has a long history with the worldwide controlling body. World rugby needs the Springboks in order to deflect attention away from their support of the apartheid structures in rugby, and their rejection of the anti-apartheid rugby structures of SACOS. In other words, the IRB���that is those who benefitted from, and who represented racism���were preferred over those who fought racism in and through rugby.

The British Lions are sooncoming, and it would be interesting to see whether any of these powerful athletes will be on bended knee in deferent acknowledgement of the Black Lives Matter movement���a gesture completely devoid of any real significance when the controlling body itself sidesteps its complicity in prolonging the life of apartheid. Of course, there are those who are overjoyed at this prospect, because of the so-called benefits to the country. Well, this country has hosted the 1995 IRB Rugby World Cup, the 2003 ICC Cricket World Cup and the 2010 FIFA Soccer World Cup, and the benefits have yet to trickle down to the township sports structures.

With the popular social myth that soccer is the ���black man���s game��� and ���rugby is the white man���s game��� an almost immutable part of South African folklore, the very visible act of ���civilising the black man��� comes through the new missionary project of rugby ���transformation.��� The British and Irish Lions will face a Springbok team led by one of the new missionary project���s successes: Siya Kolisi. The success of the Springboks at the 2019 World Cup in Japan has managed to blot out the dire situation in the country, and the tour of the British Lions will further obscure the view of the South African reality.

The Springboks represent the facade of national success, while behind the facade you will find the reality of a failed state, ably represented by Bafana Bafana. There can be no normal sport in an abnormal society.

May 7, 2021

Ethiopian women making movies

Still from Difret.

Still from Difret. Among the many stories about Ethiopia���s long, multifaceted past and politically complicated present, an extraordinary transformation that has received less media attention is the dramatic leap forward in its movie industry. Before 2004, Ethiopia was producing only a few movies from time to time. But by 2015, almost 100 new, locally produced features were hitting theaters in its capital city, Addis Ababa, each year. Local television has also grown and diversified.

Behind the rise of Ethiopian cinema is an even more remarkable tale of the women who���as writers, directors, producers, and scholars���have been leaders in this transformation.

The prominent role of women in the industry may set Ethiopia apart from most other countries. Across the globe, from Hollywood to Bollywood, film and TV industries have been dominated by men. In the United States, the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University and the website Women and Hollywood have shown that only 12 percent of directors, 20 percent of writers, and 26 percent of producers are women, even though 51 percent of audiences are.

In Africa, the 1960s-era founding manifestos of cinema institutions such as the famous Festival Panafricain du Cin��ma et de la t��l��vision de Ouagadougou (the Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou, or FESPACO) in Burkina Faso demonstrate a clear commitment to decolonization, racial equality, and women���s empowerment���so, in principle, they are more progressive than their counterparts in the United States. Nevertheless, the history of African cinema is generally recounted as a succession of male directors, like kings inheriting the FESPACO throne: Ousmane Sembene, Souleymane Ciss��, Idrissa Ou��draogo, Abderrahmane Sissako. The pattern has stuck despite proactive efforts beginning in the 1990s by festival organizers and institutions such as the Centre for the Study and Research of African Women in Cinema to empower African women to make movies.

So what is different in Ethiopia?

On frequent visits in recent years, I���ve met with some of Ethiopia���s prominent filmmakers as well as professors of film and theater history at Addis Ababa University. They���re well aware of what the movie industries are like in other parts of the world and point out that Ethiopia, too, is no paradise for women. Sexism and gender disparities in financing and lending to entrepreneurs remain pervasive, despite the nation���s constitution prohibiting discrimination. And while no agency in Ethiopia has analyzed the issue of gender in the media industry, my own informal survey of the lists of films licensed by the Addis Ababa Bureau of Culture and Tourism indicates that the gender ratios are similar to the United States.

What���s different in Ethiopia is women���s influence and success in the movie business. In a highly competitive industry where many people never make more than one movie, women have consistently enjoyed more enduring success as writers, directors, and producers. Films made by women have tended to do better at the box office and have won many trophies at the nation���s annual Gumma film awards.

Quite a few of the ���firsts��� in Ethiopia���s cinema history were accomplished by innovative women. After the nation transitioned away from the Derg regime, under which film and television were financed and controlled by the government, the first person to risk privately financing an independent movie was Rukiya Ahmed, creating the 1993 film Tsetzet (directed by Tesfaye Senke on U-matic) about a detective solving a murder case.

Later, one of the first movies to make the switch from celluloid to video was Yeberedo Zemen (translated as Ice Age) by Helen Tadesse. She originally intended the movie as a situation comedy for Ethiopian TV, but, after a contract dispute, she decided to re-edit the episodes into a single movie. In 2002, it was the first Ethiopian movie shot on VHS to be exhibited in a theater, and it sparked a revolution in the nation���s movie industry.

With the switch from celluloid to VHS, and subsequently to digital filmmaking, local cinema culture blew up, with films growing in number and diversity. Many women seized on the new opportunities to follow Tadesse���s lead, and a number quickly became industry leaders.

One such leader is Arsema Worku, a member of the executive board for Ethiopia���s Film Producers Association, which lobbies on behalf of filmmakers. In addition to being an actress, Worku has written, directed, and produced movies for theater release. Her most recent feature is Emnet (2016), a film about a married woman who, feeling trapped managing the home and caring for her baby all day, dreams of an exciting career of her own.

One of Ethiopia���s most prolific and successful directors is Kidist Yilma. Her popular movie Rebuni (2015) won Ethiopia���s most prestigious award, the Gumma. It is about a young woman, Adey, who fights to protect her grandfather���s small farm from being taken over by a corporation. Despite all the success of Rebuni, when I met with her and her husband, actor Amanuel Habtamu, she told me that the film that means the most to her is Meba (2015), a movie that takes the audience inside the head of a schizophrenic patient in a mental hospital.

These films are local productions, with budgets that are relatively small compared to the international films that Americans and Europeans often watch in art-house theaters. But Ethiopia also has some multinational co-productions, the most internationally successful of which was Difret (2014), whose executive producer was American actress Angelina Jolie.

Based on a true story, Difret dramatizes the kidnapping of child brides in rural areas by focusing on the court case of a young girl who shot her would-be husband in self defense. Four years after the film���s release, the real-life lawyer and women���s rights activist Meaza Ashenafi, who inspired the movie���s heroine, became the first woman to be appointed president of the Federal Supreme Court of Ethiopia.

The fame of both Jolie and Ashenafi may have overshadowed the fact that one of the producers and visionaries for the film was Dr. Mehret Mandefro, whose first movie, the documentary All of Us (2008), recounts her experience as a medical doctor treating HIV/AIDS both in New York and in Ethiopia. In that film, she comes to the important conclusion that, in New York City as in rural Ethiopia, poverty and the disempowerment of women have exacerbated the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Men and women in the film and media industry have often worked together to tackle difficult and important subjects such as disease, domestic abuse, mental illness, and conflict between the rich and the poor. For example, a movie that won awards at international festivals was The Price of Love (2015), the third movie written and directed by Hermon Hailay. This brutally honest portrait of the life of a prostitute explores human trafficking and the dark underbelly of urban life. Before writing the script, Hermon researched her subject, spending weeks getting to know some of these women, which is perhaps why the movie feels so real.

Another major film, on the plight of migrant female workers from Ethiopia, is Sewnetwa (2019), written and produced by Eskedar Girmay with financial support from the International Labor Organization and the Ethiopian Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. At its debut, the first woman to be president of Ethiopia, H.E. Sahle-Work Zewde, delivered the opening speech.

Ethiopia is a diverse country of more than 80 ethnic groups. Most filmmakers, whatever their mother tongue may be, make their movies in Amharic, the national language taught in schools across the country. However, some also choose to make movies in their own languages, such as Tigrinya, Afan Oromo, or Somali.

The Oromo, who are one of the largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia, have experienced a cultural renaissance in recent years, revitalizing their indigenous form of democracy known as the ���Gada system��� that in 2016 was recognized by UNESCO as an intangible world heritage. Oromo filmmakers often draw upon Gada principles for their movie production, distribution, and consumption. A common theme in Oromo scripts by both male and female writers is how the indigenous traditions that empower women in their communities can be modernized and adapted to 21st-century life.

Some of the up-and-coming Oromo women making movies today are Seble Wada, producer of the movie Wada; Seenaa Solomon, director of Xiqii; and Hawi Hailu, director of Lafaaf Lafee. The most well-known is Keyirat Yusuf. She got her start as an actress in Dire Dawa before moving to Addis Ababa to join the first Oromo-language show on Ethiopian television, Dhanga. She eventually emigrated to Chicago, where she made her first movie, Asaantii (2015), about adapting to life in America. Her second movie, Siifan (2017), reflects upon the experience of refugee women who have endured sexual and physical abuse. Like many Ethiopian filmmakers, Keyirat is not only an actor and director, but also a writer and producer. In our conversations, she told me that one of the most important skills she learned was editing.

Women have shaped the industry in other ways as well. Until 2014, Ethiopia���s television stations tended to produce their own content���mostly news and a few serial dramas���and there was little connection between the movie industry and television. But an entrepreneur named Feven Tadesse envisioned a different way of doing things. She created the first show on Ethiopian television to not only broadcast new, locally made movies but also discuss them. Viewers can vote on their favorite movies via text message. Tadesse���s company, Maverick Films, has also produced two movies, including the Gumma award-winning Lomi Shita (2011), which is a complex, multifaceted reflection upon Ethiopia���s history and its identity.

All of these filmmakers have had different experiences and offer different views on the position of women in the industry. Some consider themselves feminists, some do not. Some have had mostly positive experiences in the industry, but others feel unsupported. And some hail from unique, international backgrounds, such as New York-based Mexican-Ethiopian filmmaker Jessica Beshir, whose documentary shorts offer poetic portraits of life. The reality on the ground is complicated, and it is changing.

Ethiopia���s various civic and academic venues contribute positively to the changes by fostering discussion of gender representation. For example, the Alatinos Filmmakers Association has provided a forum where aspiring filmmakers can meet, debate, and share work. Another organization called Sandscribe has hosted free film classes for the public. Addis Ababa University, which famously occupies the grounds of one of the former palaces of Ethiopia���s last emperor, Haile Selassie, started a new master���s degree film program in 2014.

A leading expert on the Ethiopian motion picture industry is Eyerusalem Kassahun, a theater arts professor at Addis Ababa University. In addition to teaching classes on stage directing and film history, she has also written, produced, and directed her own movie that was quite successful in theaters: Traffic Cop (2013), a romantic comedy about a female officer who falls in love with a taxi driver.

Kassahun also wrote the first scholarly article on women���s contributions to Ethiopia���s movie industry for a book called Cine-Ethiopia: the History and Politics of Film in the Horn of Africa, published by Michigan State University Press in 2018. Her chapter in that book was a breakthrough. Before she set the record straight, virtually every account of Ethiopia���s movie industry, from scholarly journals to local newspapers in Addis Ababa, had focused exclusively on a handful of prominent men such as Haile Gerima, Michel Papatakis, Solomon Bekele Weya, Birhanu Shibiru, Theodros Teshome, and Henok Ayele. Since her groundbreaking work, perception has begun to catch up with reality.

That book sets the record straight in other ways. Before its publication, the only Ethiopian filmmakers whom Americans knew much about were the two who lived in America: Gerima and Salem Mekuria. The book also shows that Ethiopia���s film industry has a complicated relationship to the various ancient traditions and religious practices of its many different ethnic groups. The artistic work of Ethiopian women, in other words, does not fit neatly into any singular category.

International acknowledgments of women���s leadership role in Ethiopian film and TV remain rare. That���s everyone���s loss, because Ethiopian cinema challenges the stereotypes, common among Americans and Europeans, that Ethiopia is less progressive than they are and that Ethiopian women would find better opportunities if they left. Indeed, women���s success in Ethiopia turns the stereotype on its head, and suggests that it is Hollywood that may need to try harder to keep up.

The women of Ethiopia���s growing movie industry are inspiring. In my conversations with them, they express a love for making movies and a deep appreciation for their colleagues in the industry, both male and female. They also represent a diversity of perspectives. Some make movies foregrounding the value of tradition, family, and community while others champion the aspiration of the individual in a changing world. Some feel quite connected to the centers of power in the movie industry, while others feel marginalized from it or even live in a state of exile from their homeland. Whatever their position, their multicultural contribution to our world is vital.

May 6, 2021

Decolonizing humanity

Image credit IcyU2 via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

Image credit IcyU2 via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0. In his recent book, Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization (2021), critical theorist Achille Mbembe offers Afropolitanism as the name of a cosmopolitan vision for the future of humanity. ���As a matter of fact,��� he asserts, ���the destiny of our planet will be played out, to a large extent, in Africa. This planetary turn of the African predicament will constitute the main cultural and philosophical event of the twenty-first century.��� Articulating his concept of Afropolitanism, Mbembe attempts to reassess the intellectual, moral, and political heritage of African nationalism. What he finds exceptionally salvageable in this heritage is ���the message of joy in a great universal future equitably open to all peoples, all nations, and all species.��� To the extent that it is ���humanity��� that bears the responsibility of creating this universal future���a humanity that is not given, but instead ���pulled up and created over the course of struggles������it will be instructive to explore the sort of humanity Mbembe imagines.

Mbembe recognizes that while ���genomics has injected new complexity into the figure of the human,��� in the meantime, ���race has once again reentered the domain of biological truth, viewed now through the molecular gaze.��� This is a threatening development for what he promotes as ���the project of nonracialism.��� While he does not articulate in detail what nonracialism demands, it is intimately intertwined with ���humanity itself��� as a political project. ���At stake in the contemporary reconfigurations and mutations of race and racism is the splitting of humanity itself into separate species and subspecies as a result of market libertarianism and genetic technology,��� Mbembe finds. Here and elsewhere, despite his own warning that ���humanity is not given���, Mbembe writes as if racism is a way of splitting ���humanity itself������a singular, composite, and collective being. In such constructions, humanity is not only presumed to be a unique ���species,��� clearly discernible in its difference from other forms of life, but also postulated as categorically indivisible into minor components on the basis of race, nation, gender, or class. Little room is left for appreciating the possibility that such ���splits��� and ���divisions��� themselves are different ways of imagining humanity���as a collection of nations, for instance, or as the transnational constituency of a global war between classes.

To the extent that ���humanity itself��� is not an apolitical fact but a contested idea and ideal, its mobilization in struggles for justice, including racial justice, needs careful examination. To raise one pressing question among others: What work does ���humanity��� do as the constitutive language of a ���nonracial��� world, especially in the context of ���a contemporary neoliberal order that claims to have gone beyond the racial?��� Besides the praxis of antiracism, this examination could extend to any politics that names and�� ranks qualities, desires, or dispositions said to correspond to the essence of humanity���including, for example, Mbembe���s own identification of ���this most human expectation of a life outside the law of the market and the right of property.��� While one could partake in Mbembe���s anti-capitalism, it is something else to ground it on expectations or qualities asserted as ���most human.��� To be polemical: How shall we think about human beings who have lived, struggled, or killed for the right to property���are their expectations, inclinations, dispositions any less human?

It is Frantz Fanon, the psychiatrist and militant theorist of decolonization, to whom Mbembe turns when proposing a politics of ���ascent into humanity.��� Through Fanon, Mbembe finds that decolonization aims at ���radically redefining native being and opening it up to the possibility of becoming a human form of being rather than a thing.��� This possibility of becoming human requires, on the one hand, the affirmation of a different humanity, ���the possibility of reconstituting the human after humanism���s complicity with colonial racism.��� On the other, it demands becoming one���s ���own foundation��� for the creation of ���forms of life that could genuinely be characterized as fully human.���

What is a ���fully human��� form of life? Is it possible to propose it without perpetuating hierarchies among different beings, humans and nonhumans alike, and their distinct ways of living and dying? What kinds of struggle does ���ascent into humanity��� require if the possibility of decolonizing humanity is not given? According to Mbembe, ���ascent into humanity can only be the result of a struggle: the struggle for life,��� which consists in rising up from the depths of the ���extraordinarily sterile and arid region��� Fanon called race, or the zone of nonbeing. ���To emerge from these sterile and arid regions of existence is above all to emerge from the enclosure of race���an entrapment in which the gaze and power of the Other seek to enclose the subject,��� insists Mbembe. While the task of decolonization is ���the disenclosure of the world,��� race is an enclosure to be opened up and ultimately eradicated: ���the disenclosure of the world presupposes the abolition of race,��� he declares.

How can race be abolished? By becoming human: in Mbembe���s eyes, by becoming a ���nonracial��� being. In such a scheme, it is as if one can only become human as a nonracial being, while the only way to be nonracial is to become a human being. By implication, it appears, the more racialized one is, the less human, and the more human one is, the less racialized. A critical question arises, then, about the difference between Mbembe���s project of nonracialism and French republicanism, which exercises ���a color-blind universalism��� in its ���radical indifference to difference.��� Is the distinction between the two a matter of (not) recognizing the implicit ���whiteness��� of being human in the tradition of colonial humanism embodied by France? What happens after the implicit whiteness of the human has been recognized���is the task then to insist on the humanity of ���nonwhites,��� as Mbembe does, through (what can only be conceptualized as) deracialization? How does the project of nonracialism differ from the insistence that we must be living in a post-racial age where all lives matter? If we are to decolonize humanity, I submit, these are some of the questions to ponder.

Mbembe���s Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization is a humanist invitation to live up to humanity, to ascend to it from the depths of race and racialization. At times poetic, unusually erudite, it is recommended reading even for those who, instead of leaving it behind, would rather take back the night.

History and the politicians

Image credit Calvin Smith via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Image credit Calvin Smith via Flickr CC BY 2.0. In July 2020, Emmanuel Macron commissioned the eminent historian, Benjamin Stora, to write a report on the memory of French colonial history in Algeria and the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962) in ���a new spirit of reconciliation between the French and Algerian peoples.��� In the introduction to the report, published in late January this year, Stora lists the symbolic actions already taken by Macron to this end: his description, as a presidential candidate in 2017, of colonialism as a ���crime against humanity;��� the recognition of the torture of young communist mathematician Maurice Audin by the French military during the war; and the restitution of the skulls of Algerians killed during the French conquest from the Mus��e de l���homme in Paris to Algiers. The commissioning of such a report therefore joins a list of symbolic measures taken to normalize state relations between France and its former colonies. The report was not, however, officially addressed to the Algerian government, for whom ���it is as if it did not exist,��� as Abdelmadjid Chikhi, director of the Algerian National Archives, commented last month following a long silence from Algerian authorities.

In his report, Stora finds himself in the peculiar position of the professional historian, concerned with documenting the empirical, addressing the statesman, concerned with steering people towards normative ends. Hence Stora���s main prescription to Macron boils down to one of the few normative claims a historian can make in good faith: let���s do more history. Accordingly, he recommends the full opening of France���s colonial archives through 1962, which should, in fact, already have been opened, given the lapse of 50 years stipulated in French law. Stora also echoes Fouad Soufi���s call for jointly-held Franco-Algerian archives to be grouped under the legal category of ���common heritage,��� which would do away with the current distribution of colonial documents, divided across the Mediterranean after independence according to a tenuous legal distinction between ���sovereignty��� archives (France) and ���management��� archives (Algeria). Further, the national education curriculum, writes Stora, ought to ���emphasize the understanding of that very French history of colonialism.��� Full transparency, he argues, would allow for a properly historical understanding of colonialism and the war, as opposed to the fractured m��moires that emerge from the many self-referential communities���National Liberation Front (FLN) militants, Jews, harkis, pied-noirs, French metropolitan soldiers deployed to Algeria���born of colonial cleavages and wartime decisions. Fleshed-out history, argues Stora, ought to replace claims to ���have been right in the past��� (avoir eu raison dans le pass��).

Of course, the report is far more than a historian���s advice to a statesman; it is also a very public affair. And public reaction was predictably critical. In France, the Union nationale des combattants applauded the historian���s decision not to recommend any act of apology, but ended with an obligatory condemnation of his reading of wartime events and a slippery slope argument warning against recognizing Algerian nationalist (���terrorist��� reads the op-ed) demands. In Algeria, it was precisely Stora���s emphasis on ���recognition��� as opposed to ���repentance��� that was the most criticized element of the report; in this country so brutalized by the colonial encounter, anything short of an apology will not do.

The most astute critiques addressed the ambiguous status of the report as a kind of scholarly-review-cum-policy-proposal. On the one hand, Stora strives to be non-judgmental, thereby leaving justice, which demands judgment, to politicians. On the other, the recommendations in his report do, in fact, reveal some kind of judgment. He judges reconciliation, for example, to be a good thing���this is not necessarily an obvious idea in Algeria���and as a result, he tepidly allows himself to play the political game of proposing symbols of Franco-Algerian brotherhood (the mythical Kah��na, for example, or ��milie Busquant, the European wife of early nationalist Messali Hadj, who, together with him designed the Algerian flag).

Media reaction in Algeria seemed to ask: If the report was intended to be political, then why not propose that France apologize? And if it wasn���t intended to be political, then why write for Macron in the first place? Stora, for his part, has said that his report had the modest goal of encouraging people to think beyond the terms of memorial conflict to engage themselves in ���practical works��� of historical research. Despite this basic confusion, the report���s candor won Stora some mitigated approval; to some it signals a sincere French attempt to finally move past the sour Franco-Algerian relationship. It does, after all, publicly state facts���regarding the repossession of land, the systematic devaluation of autochthonous language and culture, as well as torture���otherwise conveniently ignored by various groups formerly committed to an Alg��rie fran��aise.

What then of the man who commissioned the report? In Algeria, the French are now a diplomatic issue; but in France, Algerians are still a domestic one. Domestically, this most recent episode in Macron���s turn towards France���s colonial past can seem incongruous in light of continued policing of populations of immigrant origin, the shutdown of the Pantin mosque (reopened on April 9), and rightward shift as elections approach. There is, however, a logic to Macron���s two-step dance with the colonial past, which was first introduced by the man who led France as it lost its empire, Charles de Gaulle. France���s colonial problems, de Gaulle posited, could be resolved by cutting off political accountability to colonial subjects by granting independence to colonies, while their profitability could be maintained through preserved economic ties with newly independent states. (Stora notes that Algeria and France have remained strong economic partners despite political problems.) By the same token, as Todd Shepard has explained, Algerian independence justified a logic of cultural difference, espoused at one point by both De Gaulle and the FLN: French and Algerians were too different from each other to live together as one country. If Algeria could not be made French, it had to be amputated.

The Stora report and anti-immigrant policies, together, can therefore be read as an attempt by Macron to regularize relations ���over there��� in Algeria, while enforcing Republican values ���over here.��� In a word, it is an attempt to fully amputate. They are both efforts to scrub France clean of its colonial past which, stubbornly, refuses to go away, chiefly because French and Algerians still live together in contemporary France. Immigration to France from Algeria, as with elsewhere from the former French colonial world, is continuous and exists in sundry forms. From the macroeconomic level, this again has seemingly everything to do with how the money flows. The funneling of resources from colonial periphery to metropole continues, and as labor follows, France will be forced, again, to ask itself the legal and cultural question born in colonial Algeria, so far left unresolved: can Muslims be fully French? In contemporary France, where Algerians with any number of historical links to the former metropole live, the question takes many more specific forms. Can harkis, native Algerians who fought on the side of France, be recognized as French heroes of a war rather forgotten? Can children of Algerians who opposed the France they later emigrated to escape social marginalization in the country they know best? And can the more recent Algerian immigrant, whether student or worker, obtain the citizenship papers that will guarantee him a sliver of colonialism���s spoils?

May 5, 2021

Ethiopia’s murderous new era

Image credit Solen Feyissa.

Image credit Solen Feyissa. On a sweltering Sunday afternoon, Effaa���s older son came home running, his face ashier than usual and his eyes wide open. He looked worried, afraid, and confused all at the same time. One of their oxen was bleeding from the mouth, he told her, unable to eat and lying in the dirt. The two ran down the hill to the ox. Effaa could see its wet and bloodied mouth but could not locate visible cuts. No wounds to speak of. Then, mother and son agreed to look inside the ox���s mouth. To their dismay, they saw that their ox was missing the front half of its tongue. This fact had a dire consequence for all three. The ox was about to lose its life, and they, their livelihood.

This was clearly the work of someone looking to harm the family. Oxen are not known to shed their tongues while they are still alive. Crucially, this could not have been the work of one individual. Effaa and her son barely had the strength to open the ox���s mouth to peer inside. Cutting a portion of its tongue must have required at least three people. It was a cruel and well-orchestrated attack, intended, she later told me, to drive the family out of the village in the hopes of commandeering their small plot of farmland.

Effaa poses for the camera in her backyard. Credit Solen Feyissa.

Effaa poses for the camera in her backyard. Credit Solen Feyissa.In better circumstances, Effaa would have a vet examine the ox, but this is rural Ethiopia; veterinary clinics are nonexistent. If vets show up, it is to deliver vaccines sponsored by government or nongovernmental organizations. For Effaa, there was only one practical choice: the ox had to be slaughtered and its meat sold in hopes of recouping enough money to buy a new one���even if, as she intimated to me later, she would end up collecting only a fraction of the money needed.

When I finally spoke to Effaa at my parents��� house eight months after she lost her ox, she wept as she narrated the challenges she faced in the months after the ox incident. ���This would have never happened if Tesfu was alive,��� she told me. Tesfu, my brother, was murdered a little over a year ago. His death changed her and her children���s lives in ways they never could have predicted.

As a widow with young children, Effaa���s material belongings were there for the taking. Although her oldest son was in his mid-teens, he wasn���t old enough to defend their property from hostile takeovers���not without risking his life, anyway.

Since Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed came to power in 2018, his rule has been marked by political upheaval and ethnic strife that have resulted in the deaths of thousands of Ethiopians. The prime minister���s perceived political miscalculations and poor tactics have been well-covered by the local and international press. But what is lost in the discussions of Ethiopia���s bloodshed is the suffering of the children, parents, wives, husbands, and communities left behind to deal with their loss.

Tesfu, short for Tesfaye, which roughly translates to ���my hope��� in Amharic, was one of the thousands of people who have been murdered in Ethiopia over the past three years. In what appears to me to be an act of random violence, a group of men he had never met before murdered him near Akaki, a small town on the edge of Addis Ababa, in cold blood. Tesfu was a father, a husband, a son, a brother, and a beloved member of his community. He left behind his wife, Effaa, and their four children, three sons and a daughter.

Image credit Solen Feyissa.

Image credit Solen Feyissa.Like millions of his fellow Ethiopian farmers, Tesfu couldn���t generate enough money from the small plot of land he inherited to support a family of six. To supplement his income, he also worked for villagers who lacked the means to till their plots of farmland, and during the holidays he sold chibo���bundles of sticks tied together to form torches burned on the eve of Ethiopian holidays. Tesfu never talked to me about what he did in any meaningful detail. I guess it���s the Ethiopian way. You just do your job, not talk about it.

On the morning of Wednesday, September 26, Tesfu had no inkling that less than two hours after leaving his home, criminals would rob him, beat him, and shoot him twice, killing him.

When our sister told me he was murdered, I felt pain in places I could not pinpoint. For a brief moment, I wanted to kneel down and pray. I don���t know why or to what end. Childhood habit, I guess. I felt helpless. I sat motionless on the bed. Overwhelmed. There was nothing to do but listen to my sister narrate the circumstances of his death, all the while asking myself, ���How could this be?��� I hadn���t seen him in six years. He wasn���t supposed to die.

Over the next few months, I could not stop thinking about the circumstances surrounding his death. What exactly happened that morning? I had more questions than answers. Untangling the stories about his death has proven more challenging as time passes. All the people I���ve spoken to, from my mother to our uncles and aunts, tell stories that do not align. Even the medical examiner���s report was barely readable because one of our cousins poorly stored it. The report, they told me, simply stated that he suffered two gunshot wounds, which, as I understand it now, led to hemorrhagic shock. Absent any explanations of how he died or who exactly killed him, I wondered what it must have been like to die alone in the dark. I imagined his agony and terror. What is it like to have all your blood drained out of your body?

Image credit Solen Feyissa.

Image credit Solen Feyissa.According to medical experts, as soon as Tesfu was shot and started to bleed, his body tried to form a clot in an attempt to stop the bleeding. As the loss of blood increased and the total blood volume in his body decreased, his heart kicked up another gear and started to beat faster to pump more blood to the body. But that only made the problem worse, triggering thirst as a mitigating step���a thirst he likely did not quench. As blood loss continued, his brain received less of it, resulting in a feeling of anxiety and probably fear. Soon, his breath came in quick succession and grew shallow. Then the anxiety gave way to confusion and it to lethargy. His body was now ready to begin shutting down noncritical bodily functions. One by one, his organs started to go offline until finally, everything was turned off and he was no longer alive. At sunrise, villagers found his lifeless body soaked in blood. He was no longer a man. He was dead at 38.

Now that he���s gone, I often think about the last time I saw him. I try to remember what we talked about and come up with very little. He had come to visit me at our parents��� house in Addis Ababa. It was the first time I���d been home since moving to the US five years earlier. Tesfu wasn���t feeling well, but he still came to see me. I remember my mom talking to him sternly, because she suspected he was going to a local healer instead of a medical clinic. She worried about him. I remember him laughing and telling our mother he was indeed seeing a medical professional and that she shouldn���t worry about him. More than our conversation, though, what is most salient in my memory is my bickering with our sister, who I thought was pointing the camera at the wrong angle. ���Are you taking a picture of our shoes?��� I grumbled, half-jokingly. I complained about what I perceived to be too many out-of-focus or blurry photos. ���How can you get this wrong? Get the little square thing right on one of our faces and push down the button. And don���t shake the camera,��� I kept saying. Looking back, all of that sounds pathetic and stupid.

What is left in the wake of Tesfu���s murder is a family in distress. In his absence, the family was exposed to attacks from villagers, most of whom, unfortunately, are blood relatives, and who wanted to run them out of their only home. His two older sons dropped out of school to help their mother and work on the farm; his daughter went off to live with her aunts in Addis Ababa in the hopes of protecting her from rural life, which, in Ethiopia, can be cruel to women. His youngest son, Bashada, moved to Addis Ababa to live with his grandparents.

Image credit Solen Feyissa.

Image credit Solen Feyissa.Although Bashada started attending a nearby school right away, it didn���t go well. He had a hard time adjusting to the school and making new friends, partly because he enrolled halfway through the semester and didn���t speak Amharic. At school registration, his grandparents changed his Oromo name to Dawit, after King David of the Old Testament, in the hopes of making him blend in more easily and avoid the bullying that often greeted those with Oromo names. It was flawed logic, and, I believe, made things worse for him. A child who, not long ago, had lost his father was being stripped of his identity as well.

Without professional counseling and guidance for children in his situation, Bashada began to withdraw and disengage. He was eating less, talking less, and moving less as time went by. He sat in the house all day and refused to go outside. One afternoon, his grandmother found him sitting with his shirt smeared in what she thought was key wot, a kind of red curry sauce. She was far off in her analysis. The ���key wot��� was actually his excrement, and it did not end up on his shirt accidentally or by mistake. It was a sign of regression no one had anticipated or prepared for. The family convened and decided it was in his best interest to rejoin his brothers in Yerer. And so he did.

During my visit to their home in Yerer in March 2020, all three boys had dropped out of school and were helping their mother full-time. Effaa told me she wanted to send the kids back to school, but all three refused to go because they wanted to be with her at all times. In their heart of hearts, the boys understand that the only way they can survive is if they stick together. I believe this is why Bashada wanted to return home. He was worried about the fate of his mother and brothers.

Image credit Solen Feyissa.

Image credit Solen Feyissa.Ethiopians in all corners of the country continue to lose their lives as a result of the political order in the country. Tesfu���s murder, one of hundreds of deaths to have occurred very soon after Abiy���s ascent to power, appears to have marked a murderous new era in Ethiopian modern history. While the Ethiopian state has remained the primary force behind the killing of Ethiopians in the past few decades, the current wave of violence against Ethiopians is being perpetrated by other Ethiopian citizens. What���s worrying and, in most instances, exacerbating the problem is the apparent government inaction or, as some suspect, complicity. This, no doubt, must change.

Tesfu is just one of thousands of Ethiopians who have been murdered in a country riven by political and ethnic strife. These Ethiopians may just be a statistic to those who aren���t impacted by their untimely deaths, but their deaths represent an incalculable loss to those who loved and depended on them. Their families, like mine, will never be the same. They suffer pain, poverty, harassment, lost hope, and thwarted dreams. And, perhaps, the loss of their livelihood, in the form of an innocent ox.

The impossibility of the black intellectual

Professor Stuart Hall with colleague, credit The Open University via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Professor Stuart Hall with colleague, credit The Open University via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. There are some scholars and intellectuals whose indispensable work one returns to over and over again. For me, as for so many others, it is the late Cultural Studies��� founding father, professor Stuart Hall (1932-2014). For though much of Hall���s rich oeuvre came in response to�� concerns in the context of Black and anti-racist struggles in his adopted homeland of the UK in a period spanning from the 1950s until his death in 2014, it still feels remarkably prescient and relevant to the present conjuncture.

Though admittedly never the most rigorous or systematic of scholars and intellectuals, the late Hall was fortunate in having so many remarkable students, friends, and colleagues. It is to their credit that his intellectual legacies have been preserved so well in the form of the Stuart Hall Foundation, in any number of publications in his honor, in the films of John Akomfrah and Steve McQueen, and in a series published by Duke University Press. In the latest addition to that series is an edited volume with Hall���s Selected Writings On Race And Difference by Hall���s erstwhile student Paul Gilroy (University College London) and Ruth Wilson Gilmore (CUNY).

At 440 pages, and covering academic essays, journal articles, occasional writings and speeches by Hall from 1959 to 2006, it is obviously an impossible task to detail the myriad themes and problems that Hall explores in this collection. Gilroy, who in 2019 was awarded the prestigious Holberg Prize from the University of Bergen, has in his own work and by his own admission not always seen eye to eye with his teacher and mentor on matters pertaining to race and racism.

One suspects, however, that Hall would have approved of his erstwhile doctoral student���s dissent. For in a telling essay on the great historian C.L.R. James from 1992, Hall in fact argues that:

Major intellectual and political figures are not honored by simply celebration. Honor is accorded by taking his or her ideas seriously and debating, extending, quarreling with them and making them live again.

In an era in which the neoliberal university and scholars and academics beholden to its logic all too often brand robust academic debate as a potential breach of ���collegiality��� and consider it inherently detrimental to the university ���brand��� if such debates take place in public view, these are apt reminders.

In his introduction to this volume, entitled ���Race is the prism���, Gilroy situates Hall���s writings on race and difference in its historical and societal context. Gilroy starts with the observation that he has over the years overheard many distinguished British academics relate their astonishment in discovering that the real Stuart Hall was in fact a Black man from the Caribbean. For Gilroy, as for so many others of Hall���s students, part of Hall���s fundamental importance is also related to him being an embodiment of the very negation of the historical ���impossibility��� of the figure of the Black intellectual. Gilroy writes that:

Discovering Hall���s Caribbean origins or migrant identity could be a shock only in a world where the mission of black intellectuals remains impossible, where being a black intellectual is unimaginable.

Gilroy makes a convincing case for the centrality of race and racism as ���indispensable for coming to terms with the meaning and the politics of his intellectual work as a whole.��� In Gilroy���s rendering, race is for Hall, ���a constitutive power��� and ���a prism��� through which people are ���called upon��� to live through ���crisis conditions.��� Hall is singled out as ���the first academic to highlight the reproduction of racism as common sense.��� As a founding figure of Cultural Studies and the Birmingham School, Hall did as Gilroy rightly notes demonstrate a particular interest in showing how the modern mass media accelerated the�� reproduction of racism. Hall���s essays on that particular topic in this volume, namely ���Black Men, White Media��� (1974) and ���The Whites of Their Eyes: Racist Ideologies And The Media��� (1980) should be compulsory reading for practically any aspiring media reporter.

It bears mentioning as a small caveat here, that though these issues are readily discernible from Hall���s intellectual and personal biography��� including his fraught relationship with the racial hierarchies that ran through his family and childhood in Kingston, Jamaica���his turning towards these issues took time to develop and mature.

There is also to my mind a strong case to be made for the centrality of what another prominent student of Hall, namely the anthropologist David Scott has, inspired by Foucault, characterized as the ���Caribbean problem-space��� in Hall���s thinking on race and difference. The centrality of that very ���problem-space��� is readily apparent from the essays on the Caribbean and on Hall���s fellow Caribbean-born intellectuals included in this volume, such as Hall���s 1996 essay ���Why Fanon?���, his 1992 essay ���CLR James: A Portrait���, and his 2002 essay ���Calypso Kings.���

Gilroy also emphasizes Hall���s seminal role as a ���movement intellectual���, and one that as such was ���a consistent if irregular participant in the public culture forged by black and anti-racist movements in the UK during more than five decades.��� This public culture and the struggles it engaged in, ���sought the extension of democracy.��� If race, as Hall indicated in his essay ���Race, the floating signifier��� (1997)���an essay also featured in this volume���was ever changing, it also meant that racism had to be studied in its concrete historical, social, and political circumstances, rather than as some supra-historical, cross-cultural, and omnipresent ���given.��� Despite the chillingly bleak circumstances unfolding as Hall wrote (the Powellism of the late 1960s, the Thatcherism of the 1980s, the successor-neoliberalism of Blairite New Labour of the 1990s), this collection is also a reminder that Hall���s was never a ���counsel of despair.��� Until the very end of his life, Hall conceived of himself as something of a Gramscian ���organic intellectual��� for whom scholarship was never an end in itself, but was forged in constant dialogue with community concerns. And so, part of what makes this particular collection of Hall���s selected writings so interesting, is that the editors Gilroy and Wilson Gilmore have also dug up fascinating, but lesser known material, even for Hall aficionados. These allow us to observe Hall the ���movement intellectual��� in concrete action, and addressing matters of crucial concern for Black communities in the UK in public addresses in texts such as ���Teaching Race��� (1980), which was first presented to social science teachers in London, and ���Drifting Into A Law And Order Society��� (1979), a lecture presented to the Cobden Human Rights Trust.