Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 130

April 27, 2021

The new movement against apartheid

Photo by Avel Chuklanov on Unsplash.

Photo by Avel Chuklanov on Unsplash. The US-Africa Bridge Building Project is an initiative to catalyze engagement between local struggles and global problems and promote mutual solidarity between Africans and Americans working to end corruption and tax injustice. This post is republished with their kind permission. It is conceived and run by Imani Countess and William Minter, with whom Sean Jacobs served in the Association of Concerned African Scholars. We hope to collaborate with the US-Africa Bridge Building Project on some of them of their campaigns.

The COVID-19 pandemic has both revealed and deepened structural inequalities around the world. Nearly every country has been hit by economic downturn, but the impacts are unevenly felt. Within and across countries, the people who have suffered most are those already disadvantaged by race, class, gender, or place of birth, reflecting the harsh inequality that has characterized our world for centuries.

This deepening inequality haunts our global future. According to a report released by Oxfam in January 2021, ���Billionaire fortunes returned to their pre-pandemic highs in just nine months, while recovery for the world���s poorest people could take over a decade.���

International scientific collaboration has yielded multiple vaccines against the novel coronavirus. But the most vulnerable people and countries have been last in line for doses, or are not in line at all, threatening a vaccine apartheid. If that continues, it will be impossible to end the pandemic, as the virus will continue to mutate and spread across borders.

The term ���apartheid��� comes from South Africa, notorious in the 20th century as the last stronghold of white minority rule. Political apartheid in South Africa ended in 1994 with free elections open to South Africans of all races. But South Africa and the world are still embedded in an international system of inequality reflecting the history of European conquest and domination.

In this system, wealth and power are still structured by race and place, both within and between nations. Whether or not one labels it global apartheid, there are striking parallels with South African apartheid.

In July 2020, UN Secretary-General Ant��nio Guterres, in the annual Nelson Mandela lecture, addressed what he called the ���inequality pandemic��� and called the world to a ���new social contract.��� Such a contract, it is clear, will not happen quickly. But it will not happen at all unless millions around the world mobilize to make it happen.

South Africa shares a history of white supremacy with other white settler states, including the United States, as Senator Robert Kennedy acknowledged in a speech to students in Cape Town in 1966. Its apartheid regime was part of a world order defined for centuries by hierarchies of racial privileges both between and within countries.

Since the discovery of diamonds and gold in the late 19th century, South Africa and its neighbors in the Southern African region have been linked closely to Western economies, particularly the United States, England, and continental Europe. Internally, apartheid in South Africa was a multilevel system of labor control and differential rights, paralleling the global hierarchy. There were gradations of privilege for whites, Asians, ���Coloureds,��� and ���natives,��� as well as for ���natives��� in urban areas, those in rural ���homelands,��� and ���foreign natives.���

Beginning in the 1960s, when independent African countries joined the United Nations, the end of political apartheid played out on a global stage. Exposure of the South African regime���s inhumanity, including forced labor, torture, and attacks on neighboring states, led the United Nations General Assembly in 1974 to designate apartheid as a crime against humanity.

Over the next two decades, the regime maintained highly visible repression within its borders while also waging proxy wars that devastated the entire Southern African region. The human toll on South Africans and their neighbors mounted into millions of lives lost. South Africa���s Western allies, despite growing willingness to speak against apartheid, stubbornly maintained their military and economic ties with the regime.

In opposing white minority rule, the South African liberation movements relied on mobilizing internal opposition, but they also issued appeals for support worldwide. They called for sanctions against the white minority regime and for direct support for South African liberation, including support for armed struggle. This outreach was essential because of the extent to which rich Western countries both profited from and sustained the South African economy and state.

Those calls were answered in different ways by governments, by multilateral bodies such as the Organization of African Unity and the United Nations, and by hundreds of solidarity organizations in almost every country of the world.

By the 1980s it was possible to speak of a transnational anti-apartheid movement. But it was a movement that drew in many different constituencies, with varying connections to and understandings of the situation in South Africa. For people in Africa and other world regions who had themselves experienced European conquest and colonial rule, the connection was clear. In the United States, too, the long history of the Black freedom movement closely paralleled that in South Africa. And the entire world recalled the anti-fascist struggle of the mid-20th century and its promises of freedom. South Africans seeking solidarity understood that they were speaking to specific audiences, not to an undifferentiated global community, and they strove to meet people where they were.

The fundamental message of the transnational anti-apartheid movement was, and remains, equal rights for all, applicable not only in South Africa but around the world. We must learn to live and work together on the basis of our common humanity, as expressed in the African concept Ubuntu.

That does not mean calling for neutrality or covering up the realities of injustice and oppression. It does mean rejecting the principle of separation (the literal meaning of ���apartheid���) and bringing people into more inclusive communities with a common vision of justice for all.

In the 1980s, activists developed a range of collective action strategies to support South African calls for political liberation. These included divestment of corporate, pension, and municipal funds from institutions invested in apartheid, as well as protests, mobilizations, and campaigns. Local activists used their own experience and knowledge of specific places and specific institutions to craft appropriate strategies and tactics.

The movement drew in politicians and civil servants in national governments, staff of multilateral institutions, leaders of religious, student, trade union, professional, and social justice organizations, and grassroots leaders in local communities. These diverse actors built collective power and worked together for a common cause. In doing so, they had to look beyond racial and national divides, work through internal debates about strategy, and overcome conflicts driven by ideology and personal ambition.

The same general principles apply today to movements confronting a global pandemic, the climate crisis, and rising overt threats from authoritarianism, xenophobia, and racism. But today���s global movements must also confront not only new global realities but also enduring injustices not addressed by the anti-apartheid movement or other national freedom struggles of the 20th century.

The victory we celebrated with the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994 was real, as were earlier�� victories in freedom struggles in other times and places. But that victory was by no means complete. Democratic political rights, in South Africa or any other country, are essential prerequisites for social and economic justice���but provide no guarantees. Indeed, the 21st century has brought steadily widening inequality and mounting threats to democracy, in South Africa and in countries around the world.

Today we have a new set of intersecting crises, with the authoritarian playbook of ���divide and rule��� gaining ground in many countries. In meeting this moment, we can take inspiration and guidance from the collective victories of earlier generations. We must take seriously the truth that none of us are free until all of us are free. This principle, voiced over the years by Emma Lazarus, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Martin Luther King, Jr., must apply across all the intersecting divisions that separate us from each other, including national borders as well as the familiar triad of divisions by race, class, and gender.

The transnational anti-apartheid movement is one powerful illustration of how this principle can be applied. First, the movement built strong personal and organizational ties across borders in�� commitment to a common cause. Second, global leadership came from those most endangered by South Africa���s apartheid regime, namely movements in South Africa and neighboring countries.

But that movement also had internal shortcomings. The greatest limitation, as in other movements targeting national, racial, or class injustice, was the failure to address gender injustice. Despite public celebration of women in the struggle, failure to listen to women���s voices, and even tolerance of gender violence, was more the rule than the exception. That remains the case today worldwide, despite the profusion of pledges to address gender equity.

Over the past decade, as global inequalities have deepened, a wave of movements has been charting new strategies and paths forward. These movements include, to give just a few examples, Black Lives Matter, the climate justice movement, movements for women���s rights and LGBTQ rights, and union organizing among care workers and those in the informal economy, who are disproportionately women and youth.

These emergent movements build on new understandings of history as well as on an analysis of the current moment. As Angela Davis noted in the Steve Biko Memorial Lecture in 2016, our work must be rooted in history and yet must go beyond the limitations of the past. That means building structures that raise the voices of those who have been barred historically from leadership positions in social change movements. From the local to the global level, organizations and movements must feature ���inclusiveness, interconnectedness, interdependency, intersectionality, and internationalism,��� Davis told the audience at the University of South Africa.

The obstacles may seem overwhelming. But we can redefine the possible, argues Varshini Prakash of the Sunrise Movement, the youth movement that has put the Green New Deal at the center of the political debate on climate change in the United States. ���In your demands and your vision,��� she proclaims, ���don���t lead with what is possible in today���s reality but with what is necessary.���

Whether on climate, on the COVID-19 pandemic, or on rising inequalities by race, gender, class, and place of birth, joining forces for justice across national boundaries is not a choice. It is a necessity.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an immediate, critical test of whether we can put this principle into practice. It will not be the last.

April 26, 2021

The demobilization of the South African masses

Image credit Louis Reynolds via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Louis Reynolds via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. It is now widely accepted that many key state jobs in government and municipalities in South Africa are allocated, not on the basis of skills, but via patronage networks of the ruling African National Congress (ANC). This has led to a collapse of state functions and government service delivery across the country. Even historically coercive functions of the state, such as the army and police service, are now commonly viewed as dysfunctional. The ���mass patronage��� function of the state is also significant. Without its ���welfare side������the payment of social benefits to millions of South Africans���the ANC would not, despite all its manifest failings, be returned to power in every election.

It is also undoubtedly true that, despite all of the indignities suffered, and the worsening living conditions endured, the masses keep on voting for the ANC. Like the humble supplicants of medieval times, many of our people have been reduced to a state of modern serfdom, to impoverished supplicants to those in power. The once militant South African masses of the 1970s and 1980s have increasingly become an army of jobless beggars, desperately queueing in all weathers, on the off-chance that they might receive government���s embarrassing R350 ($25) Social Relief of Distress Grant (introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown). (According to one study, over 60 percent of South Africans are dependent on social grants after COVID-19.)

In February, there were 86,363 new applicants for this grant, over and above the 10 million or so already registered for it. But as I write this, it appears that the changeover to a new government financial year may cause a delay in even these trifling payments. Because senior bureaucrats in the relevant departments failed to do their jobs properly, between six and 10 million of the poorest of the poor may have to wait an extra month to be paid out. People on the verge of starvation and absolute destitution cannot be assisted by this government with an amount significantly less than what many government officials happily spend on a bottle of whiskey. Worse still, is that even the miserly R350 grant may soon be cut as tighter fiscal austerity measures will probably result from the current economic crisis, on top of ongoing government incompetence, widespread corruption, and fraud.

One might expect significant protest and resistance to rocketing unemployment and social degradation in light of cuts that are already being imposed. And indeed, some traditionalists on the left have hopes that we may be arriving at some sort of political turning point; that the relative passivity of the masses is coming to an end. They argue that this might indeed be the moment to encourage traditional forms of left wing or socialist organization. But either located in the academy or NGOs, most leftish activists of the previous era now have only limited contact with the poor and likely have insufficient basis for making such judgments. A new layer of younger activists is only now emerging, but is also largely distant from the working class.

So, what do we know about the potential for new kinds of social movements?

It is clear that the country is already in a state of upheaval; social disorder will grow. Much of our understanding of this must, however, be based on personal observation and anecdote due to the general failings of the South African media. Ironically, such is the disarray in all spheres of society that not much hard data on social unrest has been readily available since about 2018. Nor are there many reliable media sources on the subject. In fact, press reports of unrest events seem to be less and less credible, let alone comprehensible, as newspapers of record cease to exist and reporters no longer visit communities or speak to those involved in the unrest. Ironically, radio traffic reports are now often the most reliable source of information on growing social upheaval. Apart from a few noteworthy examples, radical organizations and the labor movement have become increasingly inward looking and have also produced little that is coherent.

We can probably agree that, as municipalities continue to collapse across the country, township residents have regularly blocked highways and set up burning barricades to protest service delivery failures. This will likely get worse as more municipal budget cuts kick in and because public infrastructure has been stolen and destroyed on a large scale. Much of the country���s once extensive rail network has for example been pillaged and destroyed. Ironically, this largely happened under the COVID-19 lockdown when police were meant to be particularly vigilant.

Spontaneous and fragmented protest seems to be growing. But the mass organized movements of the working class and poor that bloomed in the wake of the 1973 Durban strikes and grew into the fragmented, but massive United Democratic Front in the 1980s, hardly seem to exist now. And any radical-sounding state-driven developmental project has also long since been consigned to the scrap heap. The once widely popular Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) is now forgotten and current glossy and much-hyped government plans have no popular traction whatsoever. Popular cynicism and demoralization are about all we have left.

As those of us who were around in the early 1990s soon discovered, controlled post-apartheid decolonization required the exclusion of the masses from political life. The defeat of the mass base of our nationalist movement and unions and the containment of more radical nationalists and leftists since then, were preconditions for the realization of this process. The stabilization of capitalism in post-apartheid South Africa demanded the neutralizing of grassroots aspirations towards social change. In the sphere of politics, the main priority of the ANC regime was to ensure that the urban and rural proletariat should be deprived of its own organizational and political voice���its ability to represent itself. Old militant mass structures had to be put to bed (the UDF was disbanded in the transition).

The post-apartheid ANC and its Alliance partners (the trade unions and communists) initially represented an uneasy alliance between radical and moderate nationalists. However, driven by the demoralization and disorientation of the radicals and old Communists following the collapse of the Soviet Bloc, it was the moderates who were in the ascendancy. The radicals were put on the defensive. Individual radical leaders like Chris Hani, Joe Slovo, and Harry Gwala were merely tolerated during the negotiations phase of the early 1990s in order to strengthen the party���s radical nationalist credentials. Grassroots civics representatives were also humored for a while under the SANCO banner (The South African National Civic Organization). For a while, those affiliated to the Congress of South African Trade Unions (which along with the South African Communist Party, is allied to the ANC),�� played a significant policy role for a while and maintained a militant posture, but grew less militant as union leaders became comfortable with their role in corporatist bodies and more radical rank and file structures were co-opted and tamed.

After 1990 it was only a matter of time before surviving radicals began to be marginalized. Chris Hani, leader of the SACP and spokesperson for the more radical elements of the Alliance, was assassinated in April 1993 during the unrest orchestrated by the old regime preceding the transition to democracy. The radical-sounding RDP, developed with the left���s assistance, was the radicals��� last hope. This was viewed as the cornerstone of government development policy, but it was soon replaced by the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) macroeconomic policy framework in 1996. Cosatu, the ANC���s trade union partner in the Alliance, slammed GEAR as neoliberal but the battle for a radical programme had clearly been lost.

Jay Naidoo, former COSATU general secretary and then RDP minister in the first postapartheid government, was shifted sideways. Most of the relatively small number of radical NGOs that had grown during the 1980s and presented some alternative policy options, lost their foreign donor funding, while many of their activists were absorbed into government or business. This period marked the demise of a more radical-sounding policy grouping in the Alliance and government.

In the post-negotiations era, the radicals lacked any organizational independence. Disorientated by the collapse of the USSR, and without organization or a distinct post-RDP political programme, they could offer no alternative to Mandela, and later Thabo Mbeki. Contained inside the increasingly moderate ANC, many remaining radical leaders were nothing more than individuals with grievances. Worse still, bereft of political direction, a good number of Alliance radicals were co-opted into the grouping around Jacob Zuma after he replaced Thabo Mbeki at the ANC���s Polokwane conference in December 2007. These erstwhile radicals, including avowedly left-wing elements in COSATU, thus merely provided ���left cover��� for the worst sort of parasitic and predatory ANC leadership.

This failure of militant nationalism was no accident. Militants��� involvement in the party machine was a reflection of their isolation from mass politics. In the end they felt more at home inside an increasingly conservative ANC than they did mobilizing the masses.

Formerly radical trade unions were also tamed by their inclusion in Alliance structures, via new industrial relations laws, and through corporatist bodies like the CCMA (to settle workplace disputes), Nedlac (facilitate policy inputs between government, labor, and business) and the SETAs (sectoral, vocational training initiatives). These developments helped to incorporate, privilege and corrupt leadership, while marginalizing rank and file members. Other problems included the deliberate split engineered in the old COSATU, and steeply falling membership, particularly after 2008 and crucially amongst industrial workers. As a result, many union structures disintegrated or became ineffective. Today, under very weak leadership, industrial action often takes the form of a more pre-modern, unmediated, ���physical force���, characterized by incoherent or absurd demands, random violence and destruction of property. Old solidarity networks are mostly defunct. Crucially too, the working class no longer has much of a political voice in policy and negotiating forums the way it once did. Government policymakers proceed largely without challenge.

And aside from the many self-help community action networks that sprang up under lockdown to dole out food parcels and feed the poor via soup-kitchens, the poverty-stricken masses may be too disorganized and beaten down to resist. At least, so establishment political leaders must hope. Ongoing and explosive but fragmentary service delivery protests seem a far cry from the effective mass civic campaigns of old. Their current demands, if any, are mostly incoherent and they are often easily coopted by local political players and criminal warlords and riven with xenophobic divisions.

Having lost faith in mass mobilization, many on the liberal left and in NGOs have encouraged reliance on the courts in search of redress for state failure and ruling party corruption. This has only increased popular illusions in an unelected judicial elite and further weakened traditional cultures of grass-roots organization. The masses are now mostly passive spectators, while expensive lawyers interrogate politicians in endless���and mostly fruitless���public commissions.

With the masses mostly sidelined, ruling party leadership are probably much more worried about their political allies in the Congress Alliance who are becoming increasingly unruly and unpredictable. Formerly secure members of the state bureaucracy are unlikely to take lying down the looming cuts to wages, conditions, and jobs. Many of these people���the party-state ���nomenklatura������may yet turn out to be a real bastion of reaction when their relatively comfortable incomes come under attack. Cloaked in the fake-radical rhetoric of ���Radical Economic Transformation���, leaders of dissident party factions such as those under the banner of the Umkhonto we Sizwe Military Veterans’ Association, are attempting to rally sections of the desperate masses to their cause.

The absence of any significant working-class Alliance component since the 2015 implosion of COSATU is crucial (in 2015, its largest affiliate the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, broke away). The class struggle has become suspended. ���Politics��� has become nothing more than conflict between the party elite. An amalgam of populist politicians and entrepreneurs constitutes the core of the political establishment. The continuous process of shifting alignments between contending groups of politicians indicates that the fierce battles within the ANC are devoid of any ideological significance even when couched in radical-sounding language. Branch officials and members of parliament, members of provincial legislatures and councillors, come and go as one set of alliances breaks down in favour of another.

President Cyril Ramaphosa���s current ANC leadership faces a problem of unceasing factionalism. Serious political discourse and contestation have been replaced by infighting rooted in accusations of corruption and malfeasance, which are often manufactured for solely factional purposes. This is a problem for effective governance as well: the increasing blurring of boundaries between party functionaries and state bureaucrats introduces chronic instability into already dysfunctional state structures. Divisions in the party are replicated in government and state institutions destabilized and brought into disrepute. Some factions are even willing to launch sabotage campaigns targeting state infrastructure for short term factional gain. The masses are perceived only as bystanders, to be wheeled on as stage armies in factional elite battles.

As sociologist Mike Davis points out when discussing future prospects in Planet of Slums: ������the cities of the future, rather than being made out of glass and steel as envisioned by earlier generations of urbanists, are instead largely constructed out of crude brick, straw, recycled plastic, cement blocks, and scrap wood. Instead of cities of light soaring toward heaven, much of the twenty-first century urban world squats in squalor, surrounded by pollution, excrement, and decay.��� He could be describing our own townships and squatter camps.

The left has traditionally placed its bet on the organized working class as the social force for change. But do the increasingly unemployed and poverty-stricken, slum-based masses still have a key role to play in emancipating themselves and transforming this country?

Future prospects will be determined by political processes on the ground, rather than by uncontrollable economic developments, and probably by future slum-based resistance to the system. But will it be possible to mobilize those surviving in a shifting, informal economy, behind radical causes? And will the growth of the informal sector prevent any active proletarianisation of slum dwellers in line with historical precedent? It���s hard to know whether the informal proletariat possesses ���historical agency.��� As Davis asks: ������are the slums volcanoes waiting to erupt? Or will ruthless, state-endorsed competition lead to increased involution and self-annihilating communal violence.”

A weak and divided left faces intense competition from a host of ���alternatives��� on offer: charismatic churches, xenophobic chauvinism, street gangs and local warlords, neoliberal NGOs and ethnic militias, among others.

So will a re-emergent left have anything useful to offer? The demagogues are waiting in the wings.�� And as Davis grimly reminds us: it is no exaggeration to say that the future of the whole of human solidarity depends on the nature of the response of the ���victims of the metropolis��� to the marginality that late capitalism has attempted to assign to them.

Dispossession in the name of democracy

Police use water cannon and rubber bullets to disperse a land occupation in a Cape Town township. Credit Neil Baynes.

Police use water cannon and rubber bullets to disperse a land occupation in a Cape Town township. Credit Neil Baynes. Whenever a new land occupation takes place in Cape Town, agents of the municipality���s Anti-Land Invasion Unit (ALIU) are often among the first on the scene. Lest the reader think occupations are exceptional or even spectacular���they���re not. By some estimates, as many as one in five Capetonians live in informal housing. Even during the pandemic, they have remained frequent, with over 1,000 such occupations occurring since July. Given the scale and frequency of new occupations, what was the city government doing with an Anti-Land Invasion Unit? Why was it evicting residents with nowhere else to go?

This was supposed to be the ���new South Africa,��� a country whose government would remedy decades of apartheid removals and centuries of colonial dispossession. And indeed, the government does claim to do so. The post-apartheid constitution, for example, guarantees residents ���adequate housing,��� freedom from eviction, and a government that will progressively realize both of these goals. This is not merely rhetoric. Since the demise of apartheid in 1994, the government has delivered nearly four million homes. This project was central to the mandate of Nelson���s Mandela���s newly elected African National Congress (ANC) government, which was in power when the constitution adapted language from the ANC���s 1955 Freedom Charter, demanding ���the right to live where [people choose] and be decently housed.���

Considered in the context of the entirety of South Africa���s Bill of Rights, housing���along with employment, health care, and access to basic services���becomes a central component of the country���s democracy. This expanded conception of democracy includes these socio-economic rights along with more conventional political rights, such as protected speech, assembly, free exercise, and so forth. These too were enshrined in the constitution. But the ANC consistently equated socio-economic rights with democracy more broadly. This means that if a program as major as housing delivery were perceived as a failure, it would also represent the failure of the democratic project itself, calling the government���s very legitimacy into question.

The problem is that on the ground, there are two competing conceptions of democracy. Residents want to be consulted when it comes to their housing. This is not just to feel as if they are participating in the process, though this certainly figures into the equation. It is also because consultation has real material effects. For example, what if someone were provided with formal housing but this was located even further from their workplace? It would increase the cost of their commute without providing any additional subsidies. Or what if a resident was perceived as gang-affiliated by virtue of their previous location and their new house abutted the territory of a rival gang? These are issues that could be easily addressed, but only if people are actually consulted. This is not the sort of thing that housing officials can simply figure out on their behalf. It instead requires participatory democracy.

The municipal government was quite aware of this problem, having adopted ���integrated development planning,��� an approach that consciously solicits the input of residents by convening listening sessions. But from the perspective of many housing officials, incorporating all of these voices was an impossible task. This impossibility is a direct consequence of the forced relocation of more than 3.5 million Black South Africans under apartheid. Relegated to underdeveloped rural areas with few job options, hundreds of thousands returned to cities once mobility controls were relaxed in the mid-1980s. This influx of residents continued long after 1994, leading to a nearly ten-fold increase in the number of informal settlements by the late 1990s.

New residents had to live somewhere, after all. And it was not only rural-urban migrants. In addition, intra-urban migrants left relatives��� overcrowded homes, but given the high rate of unemployment, they could not afford to rent one of their own. So instead, they built shacks. Were officials supposed to consult every single one of these residents? And how would they do so given their limited capacity? The national government certainly wasn���t increasing the Department of Human Settlement���s (DHS)budget.

From housing officials��� perspective, this situation requires technocratic democracy. In order to ensure the equitable distribution of housing stock, democracy must be efficiently administered by impartial bureaucrats. This ensures that houses are not distributed through personal favors and that protests do not automatically translate into expedited delivery. Indeed, this is why many housing officials perceive participatory democracy as a threat: input is one thing, but if popular pressure translates into preferential treatment, disorder prevails, and it becomes impossible to deliver at scale, undermining the realization of the larger democratic project.

New occupations mean that the housing backlog���the number of those on the waiting list���is increasing, or at least remaining constant, over a period of decades. From housing officials��� perspective, this represents the failure of technocratic democracy, their very raison d�����tre. In order to clear smaller occupations, politicians and bureaucrats sometimes bump occupiers to the top of the list, even when they want to be left alone. In doing so, government officials actually produce queue jumpers, who they subsequently identify as objects of their ire. They thereby misrecognize occupiers as a cause, rather than a consequence of the state���s failure to deliver. They never consider the perspective of participatory democracy: that residents usually know better than officials what they need in order to flourish, or at least to subsist. Land occupations are an attempt to realize these needs.

An ideal entry on the waiting list is someone ���who expressed a need and actually came forward to register like a good citizen should.��� This is how one DHS official responded when I asked her how people on the waiting list should comport themselves. It���s an interesting formulation precisely because it avoids the question. Most of the land occupiers I encountered had registered with DHS for a place on the waiting list���but it���s just that: a waiting list. Where were they supposed to wait in the meantime?

According to Stuart Wilson, director of the Johannesburg-based Socio-Economic Rights Institute, Cape Town���s average wait time is now roughly 60 years���longer than the UN���s estimated life expectancy for South Africa until 2015. And even if this were a relatively recent phenomenon, wait times have been decades for a while now. This is why people occupy land. Certainly there are exceptions: party-orchestrated occupations do occur, bringing supporters of one party into rival territory. But these are exceptional.

The unfortunate irony is that this situation reveals just how much proponents of technocratic democracy actually rely upon their participatory democratic adversaries to self-provision in the meanwhile. But rather than acknowledge this fact, housing officials tend to wrongly identify squatters as causes, rather than consequences, of the slow pace of delivery. They therefore typically criminalize them.

Yet, it would be equally shortsighted to valorize participatory democracy without its technocratic counterpart. The benefit of land occupations is that they often express the collective locational preference of people in need of housing. This is crucial for any housing delivery program, as location can determine the availability of employment, transportation costs, educational access, and so forth. Likewise, struggling for access to a decent location should never be criminalized. Indeed, many occupiers understand their actions as the self-realization of the constitutional guarantee to housing, a promise seemingly denied by the slow pace of delivery.

The fact remains that no one wants to live on a field in a shack, and even if this increases locational viability, it���s far from an ideal solution. Only in conjunction with the technocratic delivery apparatus can participatory democracy be realized in this respect. But the crucial precondition for this to happen is for government employees to stop criminalizing squatters. After all, what is occupying land other than waiting patiently?

April 24, 2021

Liberation after independence

Image credit Steve Evans via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

Image credit Steve Evans via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0. April 27th is a significant date for two countries on the African continent, separated by more than 5,000 km across the Atlantic ocean. On this day, both Sierra Leone and South Africa celebrate emancipation from minority rule. For Sierra Leone, it was becoming freed from the British in 1961, and for South Africa, the end of apartheid in 1994, some several decades after it became a white republic in 1961. On occasions like these, the national mood is typically festive and nostalgic, replete with commemoration events where those now in power remind us all about the tremendous sacrifice and hardship undergone during the struggles of the past. But, against the common backdrop of enduring poverty, corruption, political dysfunction, and elite capture, ordinary citizens are often left wondering if the struggles have really ever ended.

The period between the moment of emancipation and the contemporary moment marking it has arguably become consequential for considering both country���s fates. In Sierra Leone, that period has been longer as the idea of freedom was at the core of Sierra Leone���s founding over two hundred years ago, and the contestation over the meaning of that concept shaped its political trajectory since. The capital, Freetown, was first founded in the late eighteenth century by British abolitionists, wanting to find a home for both the undesirable poor blacks of England and newly freed former slaves who had helped them fight the American war of independence. This would set up a unique relationship between Sierra Leone and the British empire. The colony sat at the head of the British colonial administration in West Africa, with a ���westernized��� black population fit to fill the ranks of the bureaucracy in its colonizing project. A negotiated independence, won without mass struggle, would leave the work of decolonization incomplete, and a series of coups and military dictatorships, would culminate in a devastating civil war between 1991 and 2002. Following that, Sierra Leone took on another epochal mark, becoming a ���post-conflict state.��� Other than a brief re-appearance to the world as one of the hardest hit places during the Ebola epidemic between 2013 and 2016, plus a general election in 2018, there has been little interest from the international media to go deeper into what���s behind either the successes and failures of the Sierra Leonean national project.

In South Africa, the fascination has often gone the other way���focusing on the country���s�� supposed peace. Indeed, the post-apartheid transition period when the African National Congress (ANC) spearheaded negotiations with the National Party are touted as remarkable for avoiding a collapse into civil war. But South Africa is extremely violent. As Africa Is A Country contributing editor Sisonke Msimang recently wrote for Lapham���s Quarterly, ���After the historic 1994 elections that installed the ANC as the ruling party, there were hopes that the violence would end. Murders and rapes decreased in the years that immediately followed, but violent crime remained high. The gruesome statistics have once again begun to rise.��� And while the mainstream South African media likes to portray this violence�� as cultural pathology, it too arises from deeper social and political realities, being most pronounced when citizens confront the post-apartheid state on its failures. One of many other examples, the 2012 Marikana massacre especially cemented the end of this South African exceptionalism.

So on this week���s AIAC talk we���re asking what liberation comes after independence. We are joined by Sisonke Msimang, Oluwaseun Babalola, and Ishmael Beah. Sisonke is a South African writer whose work is focused on race, gender, and democracy, and on top of writing for a range of international publications, she is the author of Always Another Country: A memoir of exile and home and The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela (2018). Oluwaseun is a Sierra Leonean-Nigerian-American filmmaker; she founded DO Global Productions, a video production company specializing in documentaries. Her focus is to create and collaborate on projects across the globe, while providing positive representation for people of color; and Ishmael, born in Sierra Leone, is the New York Times bestselling author of��A Long Way Gone, Memoirs of a Boy Soldier and��Radiance of Tomorrow, A Novel, with his latest novel Little Family released in 2020.

Join us for the live show on Tuesday at 18:00 in Johannesburg, 16:00 in Freetown and 12:00 in New York.

In our last episode, we discussed�� ���Football and empire���, looking at the historical entanglement of South African football with English football, and what that tells us about politics and sport. We were joined by Chris Bolsmann and Tony Karon, and also touched on what the (now defunct) European Super League meant for the future of football. That episode is available this week on our YouTube channel. Subscribe to our��Patreon��for all the episodes from our archive.

April 23, 2021

A mal interpretation of Cape Flats nightlife

Sanda Shandu in Skemerdans. Credit Zaheer Banderker.

Sanda Shandu in Skemerdans. Credit Zaheer Banderker. Glenn Fortune (Kevin Smith) is up against it. Suave and old-school, dressed in white, the businessman is meant to be celebrating among friends and family at his club, the Oasis. But left and right, people are on his neck. Loans are falling due. He is on the brink of divorce and family members are turning against him as sharks circle to take over his club. Glenn is a good man in a tough situation, facing difficult choices. It���s a kak situation, and he needs to find a way out.

These are some of the opening scenes of the first episode of Skemerdans, a 13-part Cape Flats noir series set to be screened on African streaming service Showmax, run by Multichoice. Written and directed by Amy Jephta and Ephraim Gordon, it casts a darker, grittier view on the Afrikaans Cape Town drama. There is no mountain. No sea. This is the nocturnal world of jazz and whiskey and shady characters: the shadow world of the Cape.

Kim Syster in Skemerdans. Credit Zaheer Banderker.

Kim Syster in Skemerdans. Credit Zaheer Banderker.The cast of actors is familiar from South African television drama and soap operas. Kevin Smith is charismatic enough to pull off the role of a washed-up Glenn Fortune, while his wife, Ilse Klink, brings her familiar mercurial acting to bear on the role of Shireen. It���s a setup for a fierce character that is sure to develop as the series goes on.

There is a streak of humor that graciously cuts the tension from time to time. And that humor takes the form of Denver the barman (who chises the boss���s well-travelled daughter) and Melanie the waitress (who reminds him he only knows three languages: English, Afrikaans, and Kakpraat, or shit talking). While the high-stakes dealings are going on, they have the kind of gat-maakery skinner conversations we have with our friends. And, in a sense, they become the characters that ground the film for the viewer.

What makes it remarkable is that while it feels like you���re walking into an old-time noir novel, the show is also viscerally relatable and immediate because we know these spaces. We recognize the streets and smile at the references. We���ve also jazzed at Club Galaxy, a Cape Flats institution. We���ve seen how smet (dirty) Voortrekker Road can get at night. The old sax is playing ���Montreal��� by The Tony Schilder Trio. We know this scene; we���ve been here. It���s familiar and endearing for this reason. It���s also darker for this reason.

Carl Weber in Skemerdans. Credit Zaheer Banderker.

Carl Weber in Skemerdans. Credit Zaheer Banderker.The episode is beautifully shot, with dark and smoky scenes that bring the club setting and the pensive mood to life. In a way, it presents the Galaxy nightclub as an important but unstated lead character in its own right.

This is not Seven de Laan. The plot creaks with the tension of drama under the surface, of complicated characters, broken promises and double dealing, all shaded by the lights of the Oasis. The noir elements are undeniable: it���s the neon lights reflected in dark gutter water, street lamps and gold chains gleaming in the shadows, a pair of eyes in the rearview mirror. Every moment is loaded with tension. While the transitions feel dreamlike, the sense of doom builds as you watch Skemerdans, and you know that things can escalate at any point. But it is also not your Cape Flats gangster film, like Noem My Skollie, Four Corners, or the drug-addled Dollars and White Pipes. It steers clear of romanticized depictions of masculine hyper-violence, the near-inescapable tyranny of working class life, and grand themes of redemption. Yasss.

The aesthetic is a deliberately stylized one, with the muted shades of the immaculate suits, the metallic sheen of the scotch, the charred gold glint of the old saxophone playing in the club. Black and white piano keys and the final crimson blood splatter that sets up the mystery: who did it?

Carmen Maarman in Skemerdans. Credit Zaheer Banderker.

Carmen Maarman in Skemerdans. Credit Zaheer Banderker.There���s a reference to Edward Street in Bellville when the club owner���s prodigal daughter remarks that she and her friends ���wil vir Edward Street nog wakker maak��� (want to still wake up Edward Street). We enjoyed this reference on two levels: first, because of our early twenties nostalgia for that space. But on another level, there���s a serious and real underworld parallel buried in that reference. Edward Street has a notorious history of shootouts and underworld figures monopolizing nightclub strips by force. Albeit a fleeting reference, it invokes a Cape Town reality of household names forcibly taking over long-standing aboveboard family operations with a ���Name your price���or else������ In fact, this is the central premise of the debut episode.

A delicious one-liner from the show throws this predicament into stark relief: ���Be the showman, be the distraction, entertain the masses with your sequined jacket and your magic tricks, we���ll be the machinery underwater.��� The machinery underwater is exactly what Skemerdans unveils and imagines so well.

Despite the stark interplay between the shadowy threats and the glittering stage, the opening episode continues to feel close. There���s the glitzy dress sauntering down the spiral staircase, the languid entrance of a starlet that feels very Hollywood. But there���s also the daddy-daughter dance after a toast to the rise of a family from Athlone, and the voice of the nightclub host played by Allistair Izobell���a local nightclub legend���which will have you feeling like you���re in your family home listening to the radio. Even towards the end, when the returning daughter gets a dreaded phone call, it���s from her Uncle Trev. Everyone has that Uncle Trev. Through stylistic choices, this noir series makes the familiar iconic.

It is a mal interpretation of Cape Flats nightlife. We can���t wait to see the drama unfold.

April 22, 2021

Songs of freedom

Photo by Carles Martinez on Unsplash

Photo by Carles Martinez on Unsplash The history of Dakar has long been intertwined with the networks of exchange and exploitation that characterize the Black Atlantic. The peninsula that Dakar sits on today was ruled over by the Lebou people until the late nineteenth century. However, nearby Gor��e island was occupied by the Portuguese in the fifteenth century and ruled over successively by every European slaving empire since.

Gor��e became a major exit point for Africans during trans-Atlantic slave trade, and this would (again) mean that the cultures of the adjacent hinterland would go on to leave a significant mark on the new cultures forming in the Americas. When the French consolidated its rule over its colonial territory in West Africa, they would occupy the peninsula, and in 1902 France made Dakar the capital of a territory that stretched from the Cap Vert, across the Sahel to Lake Chad, and down the West coast of the continent. Back in the capital, France would build a colonial outpost that would mirror the logic of apartheid that was emerging across the entire continent.

Under the leadership of the poet-president L��opold S��dar Senghor, Senegal would gain its independence, and Dakar would become a central node in the cultural and political movements for African self-determination. The strong pan-African orientation of Dakar would turn it into a truly Afropolitan city, and today it retains a population as diverse as any capital in the Global North.

Like other post-colonial capitals in the early days of independence, Cuban music served as an orientation for modernity, and as various permutations of the rumba streamed in from the Kinshasa and Conakry, local musicians would try their hand at producing their own interpretation of the sound. Inserting local instruments and rhythms into local bands at the lively downtown music clubs, a popular music started to form called mbalax. This local live music scene would become a training ground for the continent���s biggest musical stars, while the live music scenes in many other post-colonial capitals would suffer the effects of economic decline and conflict. The subsequent global success of such names as Youssou N���dour, Baba Maal, Ishmael Lo, and Thione Seck would inject resources back into the local scene, allowing it to retain a unique vibrancy and local orientation throughout the years.

When hip hop started to make its way into the stereos of middle class youth with diaspora connections in Dakar, they would find a fertile ground from which they could produce, distribute, promote, and perform their experiments in this new genre. As the Senegalese rap scene, also known as rap Galsene, grew, it would come to rival mbalax in popularity, and even surpass it for many youth living at the city���s margins. As an uneasy relationship with the former colonial rulers would continue to plague the politics, economics, and culture of the nation, it was the hip hop scene that would take on a particularly political orientation. By the turn of the century, rappers would play an integral role in mobilizing working class youth to participate in the formal politics of the nation.

So in this show, we take a listen to how various global influences have come together with a strong sense of locality to create an epicenter of the World Music industry, and how the navigation of the post-colonial nightmare served as an incubator for an explicitly political hip hop culture. We are lucky to have a highly informed and insightful guide as we explore the sounds of the city of Dakar, Senegalese rapper, oral literature researcher, and Dakar native, Fehe Sarr.

Tune in to Worldwide FM from 14:00 to 16:00 GMT to catch the show live. You can still listen back on the show page if you miss that time, and follow us on Mixcloud to get notified about new shows, and listen to past ones.

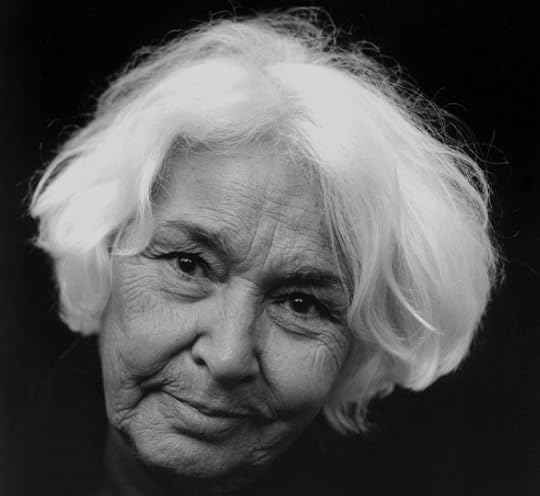

The many lives of Nawal El Saadawi

Image via Melafestivalen-Oslo on Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Image via Melafestivalen-Oslo on Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. ��� Woman At Point ZeroEverybody has to die, Firdaus. I will die, and you will die. The important thing is how to live until you die.

The recent death of Nawal El Saadawi���s has caused reverberations in Egypt, the Arab world, and beyond. A self-proclaimed ���historical, socialist feminist,�����El Saadawi lived a long and politically courageous life���a life in which she experienced imprisonment, job loss, censorship, and death threats, and��over whose course, El Saadawi also erred and adopted arguably disappointing positions.��It is a privilege to grapple with her legacy, to confront the contradictions and challenges raised by the issues she wrote about, issues that many of us in the Arab world wouldn���t have had the courage to think and speak about were it not for her work.

It is fitting that the news of El Saadawi���s death, and the subsequent flood of articles, posts, and tweets that were written in commemoration, were as controversial and complex as the life she lived. The ensuing discourse has touched on themes including how formative her work was, whether it still applies to the current moment, the effectiveness of individual struggle, and, most notably, how we can reconcile our need for political heroes with the fact that our intellectual role models may occasionally disappoint us. For some, she was a feminist icon who tackled ideas about sexuality that were taboo in the Arab world; for others, she was a socialist who fought for national liberation. For some, she was a revolutionary; for others, she was a counterrevolutionary. El Sadaawi���s multiple, complex, and changeable positions mean there is more than one version of her to commemorate, more than one legacy over which to fight.

For me, like for many others in Egypt and the Arab world, reading El Saadawi was a formative experience. It was like being offered a new lens with which to see the world. Her often bold, staunchly anti-capitalist, feminist writings and interviews provided an alternative worldview than the ones presented to us. I remember devouring her works and feeling like I���d found an advocate for Egyptian womanhood, a feeling that I know was shared by many. It was not only what El Saadawi said, it was also the fearlessness and braveness of how she said it.

It was, therefore, a jarring surprise when, many years later, El Saadawi seemed to become an apologist for Sisi���s Egypt. Despite joining the ranks of the revolutionaries in 2011, calling for constitutional amendments and the establishment of a union for Egyptian women, El Saadawi��refused to denounce Egyptian President Abdelfattah Al-Sisi as a counterrevolutionary on several occasions, even going so far as defending him.��In a 2015 Guardian interview, she said, ���There is a world of difference between Mubarak and Sisi. He has got rid of the Muslim Brotherhood, and that never happened with Mubarak, or with Sadat before him.��� She maintained the same position until at least 2018, when she accused a BBC presenter of bringing her on to instrumentalize her as an Egyptian ���opposing view,��� manipulating her as a means to push a Western agenda. In order to understand how Nawal El Saadawi, one of the most important third-world radical feminists of the past century, came to adopt such a position, we need to consider her positionality and the immense difficulty she encountered in speaking to divergent sets of audiences throughout her life. While trying to avoid being pigeonholed under several reductive categories, she was elevated to the dubious honor of being the ���representative Arab feminist.���

Born in 1931, El Saadawi wrote more than fifty books tackling topics such as sexuality, female genital mutilation (FGM), and sex work, topics that propelled her name and books to recognition in Egypt, the Arab world, and beyond. She also held several stances that were considered ���taboo,��� such as calling for equal inheritance between men and women, defending homosexuality, and criticizing the veil.�� However, through her writings, she also���in a less sensationalized way���tackled imperialism, capitalism, and class. According to her own accounts, El Saadawi was radicalized by her life experiences; her own experience of FGM at the age of six, witnessing her paternal peasant grandmother���s clashes with government officials, and facing colorism from her lighter-skinned maternal grandmother were among the experiences that she recounts as formative.

It���s not difficult to imagine why an outspoken female critic of Islam and authoritarian Middle Eastern regimes would gain visibility with Western audiences.�� El Saadawi herself was well aware of how she could be used by Western commentators and audiences to propagate certain agendas, and in several of her works strove to de-sensationalize her writings and preempt her categorization as simply a critic of Islam, a ���third-world dissident,��� or a ���resistance writer.�����In a 2018 interview with The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, she said, ���Female genital mutilation is only one of the topics I write about, and I wrote about many more, which were ignored by literary critics and the global media.�����In much of her analysis, she held the position that��Islamic fundamentalism could be used as a tool of oppression against women in Arab countries, while simultaneously attempting to reject Western critiques of Islam. ���It is important,��� she wrote in The Hidden Face of Eve, ���that Arab women should not feel inferior to Western women, or think that the Arabic tradition and culture are more oppressive of women than Western culture.��� In discussing her life, we need to be cognizant of��narratives that reduce her legacy to being simply ���a victim of Islam��� or a ���dissident of authoritarian regimes,��� as these framings often serve to severely reduce her complex political thought and sanitize her radicalness.

To shelve her feminism under a generic, ahistorical brand of ���feminism against Islam��� or ���feminism against authoritarian governments��� would be to perform a grave disservice to her, in addition to completely removing her from the historical context which framed her beliefs. In fact, El Saadawi���s other political stances are often given less media coverage than her feminism relating to women���s sexuality in Egypt, despite how closely the two are tied.

El Saadawi is a product of a generation of third-world intellectuals inspired by the resistance movements of the 20th century.��During the regime of Anwar Sadat, she professed to feeling ���alienated from my homeland.��� Sadat���s neoliberal ���open door policy��� in the seventies was the impetus that drove her to write about capitalism���s exploitation of women and to insist on several occasions that socialism was necessary for women���s liberation. In her writings, she coined the term ���patriarchal class society,��� pointing to the political and economic factors that contribute to women���s oppression. Indeed, she saw women���s oppression as a result of social and material conditions rather than a given natural state.��When she was subsequently imprisoned by Sadat���s regime in 1981, it was not for her views on sexuality, as some commentators erroneously argue. Instead, it was��for her vehement opposition to and critiques of the Camp David agreement with Israel, Sadat���s ambition to realign Egypt with the interests of the US, and his opening up of Egypt to international financial institutions. (She would bear other consequences for her views on sexuality,��including losing her job in the Ministry of Health after publishing Woman and Sex in 1972). Her release from prison came three months later, after Sadat���s assassination���a historical detail crucial to contextualizing her fight for women���s rights.

El Saadawi also never shied away from her Africanness, stating, ���I stopped hiding my dark skin very early in my life, since I discovered Egypt is in Africa, not in the so-called Middle East. In fact, I never use the term Middle East.��� She was dismissive of the false equivalences of and hated feminist identity politics, calling Hillary Clinton and Margaret Thatcher ���patriarchal women.���

El Saadawi did not limit herself to criticizing the Egyptian government. She was also a staunch critic of imperialism, and her analyses were clear on the role played by colonialism in the subjugation of Egyptian and Arab women. In several English- and Arabic-language interviews, she completely rejected the notion that Egyptian or Arab cultures are inferior to those of the West. In fact, she often held the position that women���s liberation in the third world has to be tied to national liberation, a view which seeped into others of her strongly held opinions, such as her support of the Palestinian struggle and of the Marxist government in South Yemen.

In The Hidden Face of Eve, a text which focuses on patriarchal societies in the Arab world, she discussed working women���s involvement in the fight against the British occupation of Egypt while also framing the 1978 Iranian Revolution as an anti-imperialist victory over the West and critiquing its opponents (the US and Sadat). An internationalist, she vehemently opposed the Iraq War, supported the miners��� strike of 1984���85 in Britain, and campaigned against the First Gulf War, even participating in the 1992 Commission of Inquiry for the International War Crimes Tribunal, which caused her to face further censorship from Sadat successor and US ally Hosni Mubarak.

While trying to stay loyal to and seek solidarity with Egyptian and Arab women and progressives, El Saadawi also faced ostracization from the more conservative circles of Egyptian and Arab society, often finding herself labeled a heretic and facing multiple lawsuits and endless media slander. She left Egypt briefly in 1993 to spend time teaching in the US. Though marginalized and ostracized by society in Egypt, El Saadawi was simultaneously welcomed internationally and by feminists in the global south. Despite pressure from her new audience to turn on Islam, she maintained that patriarchy, colonialism, and neocolonialism were the driving forces behind women���s oppression. She returned to Egypt three years later, and in the late 1990s and early 2000s her house became a space for organizing in the years leading up to the January 2011 revolution. By that point, her main target of critique was what she called ���religious fanaticism.��� In 2010, she even proclaimed she was getting more radical with age.

That El Saadawi was aware of her potential usefulness to Western observers and commentators on Arab and Egyptian politics didn���t make her susceptible to these framings. Nevertheless, El Saadawi was sometimes seen to accept and even welcome narratives that exceptionalized her and positioned her as a representative of Arab feminism, often giving interviews in which she presented her life in a ���rags to riches��� framing: the doctor from rural Egypt who came to speak for Arab women. In a 2015 Guardian interview, in answer to a question of whether it is hard to be a divorced woman in Egypt, she said, ���If you are an ordinary woman, it is. But I���m very extraordinary. People expect everything of me.�����This dichotomy of collective radicalism and individual pride also surfaced in her writing, particularly in Memoirs from a Women���s Prison, which El Saadawi reportedly wrote during her time in jail using an eye pencil and toilet paper. In describing her time in prison, she often paints a picture of the other inmates as overly dogmatic, either in their Marxism or in their Islamic fundamentalism. However, while in prison, El Saadawi also sought to unite women in the Arab world by forming the Arab Women���s Solidarity Association, an organization that was banned by Mubarak. In this instance, the tensions of her positionality appear most clearly: a socialist feminist, but an exceptional one; both a liberator of Arab women and a victim of despotic regimes. In buying into this narrative, she seemed to relish an individualistic framing of her life, even as the content of her work emphasizes the overriding importance of resistance and activism. We may wonder, then, if we should try to understand her apology for Sisi as another instance of the fraught positionality that comes with being a third-world intellectual on a global stage.

It is possible that El Saadawi found herself caught between two identities, one that she embodied in Egypt, and one that she found herself representing outside of her homeland. It is also possible that El Saadawi���s worldview, like those of many other intellectuals, shrank in line with the defeat of left opposition and resistance forces, not only in Egypt but globally. It is also possible that she viewed Sisi, outwardly secular, as much more tolerable than the Muslim Brotherhood, given her lifelong battle with religious fundamentalists. Maybe it���s an amalgamation of these factors, a formula we can never hope to know.

How, then, can we justly remember and commemorate El Saadawi���s many complex political identities? What lessons can we draw from her life to learn about the immensely difficult task of the third-world intellectual? Are these questions we should even attempt to answer? Our multiple griefs at her passing remind us of the problem of making our political and intellectual heroes into icons, condensing the messiness of their historic positions into consistent and incontestable legacies. We see, then, how mourning Nawal El Saadawi is in and of itself a political act. To mourn Nawal El Saadawi is to think about the avenues she opened up to us, the vocabularies of emancipation with which she provided us. To mourn Nawal El Saadawi is to consider the immense responsibilities and contradictions that come with being a celebrated radical intellectual.

April 21, 2021

The decline of Liberia in black internationalism

These images were taken as part of the togetherliberia.org project. Photo by Ken Harper CC BY 2.0.

These images were taken as part of the togetherliberia.org project. Photo by Ken Harper CC BY 2.0. In 2019, the Government of Ghana ran a successful campaign, the Year of Return, marketing the country as a beacon for the African diaspora. Drawing upon commemorations marking the 400th anniversary of the introduction of slavery in the English colony of Virginia, the initiative primarily targeted black Americans and attracted high-profile visitors like Cardi B, Steve Harvey, and Ilhan Omar.

Next year marks the bicentennial of black American settlement under white American direction in Liberia, Ghana���s regional neighbor. The resulting ���Americo-Liberian��� settler group ruled over the country following its 1847 independence from the white-dominated American Colonization Society, only losing power after a military coup in 1980. Even without the drastic curtailing of global travel as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, the prospect of a similar pilgrimage or significant commemoration of Liberia���s unique heritage seems unlikely.

The country, once prominent in the Western pan-African worldview, now infrequently figures in such discussions. A recent ���Conversation��� on black internationalism in the American Historical Review, the official publication of the American Historical Association, did not feature a single reference to Liberia in the body of the discussion. The uneasy product of collaboration between white southern slaveholders and northern abolitionists, Liberia lacks the revolutionary pedigree of a nation like Haiti, or the heritage of armed resistance of Ethiopia���s struggle against European imperialism. A search of posts on Black Perspectives, the blog of the African American Intellectual History Society, with ���Liberia��� in the title returns zero results; ���Haiti��� garners ten.

Historically, Liberia ignited the imagination of black people across the globe. For over a century, it was one of the few countries in an imperialist world system where black people governed themselves. Although Liberia���s colonization was controversially implemented under white American direction in 1822, by the second half of the century, prominent black American theologians like Henry McNeal Turner and Alexander Crummell were promoting black emigration to the only internationally recognized independent nation in west Africa.

Black America���s enthusiasm for Liberia accelerated in the aftermath of World War I. As famed black American intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in the 1930s, ���the success of Liberia as a Negro republic would be a blow to the whole colonial slave labor system.��� Both Du Bois and Marcus Garvey, two of the most prominent American pan-Africanists (Garvey was an immigrant from Jamaica), were bullish on Liberia in the 1920s.

However, each soon drifted away from their veneration of the country, simultaneously foreshadowing and contributing to Liberia���s broader diminution on the pan-African stage. In the final years of his life, Du Bois (along with many other black Americans) actually settled in Accra, Ghana, embracing Kwame Nkrumah���s more revolutionary pan-Africanism. Meanwhile, neither Garvey nor his Black Star Line ever reached the continent, and Liberia was never definitively associated with his movement���s ���Back to Africa��� mantra.

Liberia���s pan-African stature rapidly diminished in the 1960s as celebrated visionary leaders like Julius Nyerere and Nkrumah assumed state power in Africa. Leslie Alexander Lacy, a one-time black American expatriate educator in Ghana, embodied Black America���s disappointment with Liberia at this time, writing, ���politically thinking blacks are critical of [Liberian President] William V. S. Tubman [president since 1944], his dependency on Firestone and Goodyear rubber plantations, and his inability to move toward a more pan-African direction.���

The violent 1980 coup, a long-running civil war (1989���2003), and xenophobia induced by the Ebola crisis (2014���16) all either contributed to the destruction of documentary evidence of Liberia���s pan-African interventions or further undermined the country���s status as a source of revolutionary intellectual thought.

At least the second part of Lacy���s dismissal is questionable. Tubman was indeed wary of the call for a United States of Africa espoused by Nkrumah; the more moderate bloc of African states took the name the ���Monrovia Group,��� after the Liberian capital. However, Tubman���s government actively pursued an anti-colonial policy generally in line with Liberia���s historic position as a beacon for black aspirations.

President Tubman hosted a 1959 summit with Nkrumah and S��kou Tour�� of Guinea which laid the groundwork for the formation of the Organization of African Unity. A Liberian official played a prominent role in creating the African Development Bank. Southern African freedom fighters like Nelson Mandela visited Liberia and received support from Tubman, while other exiles taught at the University of Liberia. Tubman even maintained a long-term relationship with Marcus Garvey���s first wife, the Jamaican-born Amy Ashwood Garvey. His successor, William Tolbert, deepened Liberia���s pan-African engagements, broke ties with Israel, and was President of the Organization of African Unity at the time of the 1980 coup.

Lacy���s critical appraisal of Liberia���s position in anti-colonial pan-Africanism has become ensconced in contemporary Western thought. A recent assessment by a Georgetown University scholar pointing to Liberia���s anomalous historical position emphasizes the country���s reactionary roots by downplaying the country���s erstwhile pan-African allure and focusing on the anti-emigration sentiments of prominent black leaders like Frederick Douglass. Another American scholar, examining the discrimination against those who did not have an Americo-Liberian background, asserted that Liberia���s establishment ���redrew the frontier of the antiblack world.���

One of the few ��migr��s to Liberia in the 19th century to assume prominence in modern discussions of pan-Africanism is Edward Blyden. However, Blyden���s contributions as a diplomat and administrator in Liberia are often overlooked in favor of his intellectual contributions to the ���African personality��� and cultural pan-Africanism. The most recent biography of Blyden makes no reference to his role in co-founding the True Whig Party, one of Africa���s oldest political parties and the political home of President Tubman. Unlike the titans of the Haitian Revolution (Louverture, Dessalines, Christophe), the leading figures of early Liberian nation building (Roberts, Russwurm, Teague) rarely feature in contemporary discussions of 19th-century pan-African icons.

The undeniable disdain the Americo-Liberian elite displayed toward their fellow compatriots from an undiluted African ethnic background may explain Liberia���s marginalization in pan-African circles. Western writing on Liberia often criticizes the black emigrants for reproducing racist American practices in Africa.

While it is important to foreground the lingering malignant impact of white American racism on Liberian society, a move toward a holistic postcolonial praxis would recognize Liberia���s challenges and accomplishments in the face of overwhelming adversity. It would also consider the pressures emanating from the less enlightened contributions of ostensible pan-African allies.

In 1930, Liberian President C.D.B. King resigned in the face of allegations that he had countenanced the recruitment of forced labor to European colonies in Africa. Charles Johnson, who later became the first black president of Fisk University, sat on a League of Nations commission of inquiry into the allegations, which tarnished Liberia���s global reputation. Adom Getachew has recently argued that this body���s hypocritical condemnation was an effort to circumscribe Liberian sovereignty.

Du Bois and Garvey sparred over their visions for Liberia; in fact, the former originally encouraged Lacy���s despised Firestone Rubber and Tire Company to establish operations in Liberia. Although Du Bois soon repudiated this position, other black American intellectuals retained confidence in a capitalist-driven model for Liberian development.

Max Bond Sr., a black American president of the University of Liberia (1950���54), corresponded with Firestone officials in the US and encouraged them to leverage their influence in the region with the aim of ���winning Africa.��� Bond also warned officials at the US Embassy of attempts by UNESCO to ���completely uproot��� the university���s American-style system of education. Unsurprisingly, he frequently clashed with his Liberian boss.

Liberia���s position was further diminished by its strong backing for the US during the Cold War. President-elect Tubman and his predecessor were the first black dignitaries to be entertained at the White House since Booker T. Washington���s visit in 1901. Liberia also hosted a Voice of America relay station and housed the main CIA listening post in Africa.

Genuine attempts to expose neocolonialism and decolonize the academy should seriously consider both the merits and demerits of Liberia���s role in pan-African thought and action. Those looking for inspiration in this regard can direct their attention to efforts primarily led by Liberians and Liberian-Americans. The Focus on Liberia platform hosted several events during Black History Month under the banner ���Liberian History is Black History.����� Registration is now open for the 52nd annual meeting of the Liberian Studies Association, slated for 22���24 April.

The gulf between these efforts and more ���mainstream��� activities highlighting black internationalism fails not only Liberia, but all of those who, as the country���s founders asserted in the 1847 declaration of independence, ���were debarred by law from all rights and privileges of man��� due to their skin color.

WhatsApp and anti-capitalism: should you stay or should you go?

Photo by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash.

Photo by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash. This is one in a series of re-publications, as part of our partnership with the South African publication, Amandla.

What���s up with WhatsApp? In January 2021, Facebook, the parent to the widely popular messaging platform, announced changes to privacy and terms of service policies that will have wide ranging implications for the sharing of WhatsApp users metadata. Following a huge public backlash, Facebook put the changes on hold, but it has signalled its intention to push them through by May 15,�� 2021.

Many on the left rely on WhatsApp for information and organizing. It was in wide use as an organizing tool during the #FeesMustFall protests and that continues in a range of activist activities. However, many are also considering leaving the messaging platform and migrating to other, more secure ones, or have done so already.

So, once the controversial new terms of service come into effect, should you stay and simply accept these changes, or should you leave for another, more secure messaging service? If you go, will your friends, comrades and family follow, or will you find yourself confined to the lonely wilderness of other, less popular, services?

Before tackling these questions, it is necessary to look at what the proposed changes actually are, as well as the broader controversies around the service and other big technology companies that dominate the communication landscape. Underpinning these questions are broader strategic and tactical questions about how anti-capitalists do and should relate to big technology companies like Facebook.

WhatsApp announced changes to its terms of service that would allow it to offer a broader range of business services, including making it easier to communicate with businesses. Businesses may, for instance, use Facebook as a technology provider to chat directly with its customers. Using these services is voluntary.

In defending these changes in the wake of the public backlash, Facebook conceded that it had communicated them poorly and that the public had misunderstood its true intentions. The company claimed that WhatsApp did not intend to share more data with Facebook and with third party providers than it already did.

It appears that WhatsApp also removed a section from its international privacy policy, giving users the right to opt-out of sharing personal information with Facebook. This option still appeared in the privacy policy of my own WhatsApp mobile app, dated�� July 20, 2020. However, WhatsApp will not share data about their users in the UK and Europe. This is because privacy protections are stronger in the region than they are in the rest of the world.

Facebook has made it clear that they will not, and in fact cannot, share the content of WhatsApp messages. This is because messages are end-to-end encrypted, which means that neither WhatsApp nor Facebook have access to their content.