Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 135

March 15, 2021

Capital in flight

Bus stop Lagos, Nigeria. Image credit Ebun Akinbo for the IMF via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Bus stop Lagos, Nigeria. Image credit Ebun Akinbo for the IMF via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. This post is part of our series ���Climate Politricks.���

At least 3.7% of Africa���s GDP leaves the continent as illicit capital. This translates into $88 billion annually. Most affected are countries rich in mineral and natural resources though capital flight is not limited to these countries, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Pilferage of government funds often happens as a result of grand corruption and collusion through illegal transfers of money out of a country. This is particularly egregious as COVID-19 demand that governments institute measures aimed at protecting citizens from the pandemic���s consequences.

Success in addressing the pandemic and its effects have to a great extent depended on programs and policies governments already had in place. Countries with functional policies before the onset of the pandemic are better prepared to handle the health, social, and economic needs of their citizens. On the other hand, countries with limited social policy regimes have resorted to reactive, disjointed, and insufficient measures to protect from the vagaries of the pandemic. The need for a functioning social policy regime has never been more pressing than it is now.

Social policy relates to state interventions that directly affect social welfare, social institutions, and social relations. Social policy therefore aims to provide basic services such as water, education, health, and sanitation to citizens through the state. Recently the role of social policy has been limited to poverty reduction. Success during and after the pandemic requires social policy that transcends the instrumental role of poverty reduction. Transformative social policy does this by proffering multiple instruments capable of promoting production, protection, reproduction, redistribution, and nation-building.

Financing of social policy is often a major obstacle to implementing and expanding schemes. Before the current crisis brought about by COVID-19, health, education, and social policy budgets in countries were already constrained. With the current economic crisis, budgets may face additional constraints, further deepening financing gaps. For budget stabilization and to repair public finances, governments might cut social spending, despite households being in greater need of protection following losses of jobs and income. Poverty levels might rise as a result. The current crisis precipitates urgency for governments to expand social services particularly in health, and social protection measures to cushion households from the effects of the pandemic.

Governments often highlight constrains of affordability as the main hindrance to social policy expansion. Traditionally, to finance social policy, governments have increased fiscal space through official development assistance (ODA), additional borrowing, improving revenue collection and reprioritizing expenditure. However, these sources of financing are becoming inadequate and dependence on these forms of revenue might compromise expansion of already constrained budgets. Usual sources of financing such as development aid could decrease as donor governments deal with the pandemic in their respective countries.

To meet the current and future demand for social spending, countries in Africa need to seek other sources of financing. One of these sources of revenue are recoveries from illicit financial flows (IFFs). The continent is one of those most negatively impacted by IFFs, as pointed out earlier. Other acts include misconduct by multinational companies complicit in dodging taxes, mis-invoicing, and transfer pricing, and cross-border illegal activities, such as dodging customs duties, trafficking in natural resources, and hiding wealth in offshore havens. The amount lost through IFFs is almost equivalent to annual inflows of official development assistance.

Financing from recoveries from IFFs can assist in closing the underinvestment gap. This gap can be overcome by stopping the hemorrhaging of resources, reclaiming stolen assets, and using the resources to expand social policy. State capacity is important in stopping the hemorrhage of resources. Governments have to strengthen anti-corruption laws to curb enablers of IFFs. Increased fiscal space can free other resources, thereby creating fiscal capacity to expand existing social policy interventions or to implement new programs. Curbing IFFs can potentially increase the revenue source of capital to finance social policy and investments in social development.

To curb IFFs, cooperation at international level is important and includes structuring reforms in the international tax system, which foster transparency and enhance cooperation between different tax jurisdictions. Improving transnational and trans-agency governance of illicit flows can further help in promoting the recovery of assets and IFFs. Also, countries with strengthened laws to deal with revenue loses through corporate tax avoidance could thereby increase their tax base. Countries with tax treaties that promote IFFs need to renegotiate such treaties. At national level, citizens can build coalitions to agitate for reforms and better distribution of resources, as well as openness and transparency in tax systems.

Curbing illicit financial flows is important for increased social spending but not sufficient to determine financing of social policy. Available resources do not necessarily reflect how resources are distributed and how much of the revenue reaches lower income groups. Although institutional capability is important in curbing illicit financial resources, the political context determines how resources are distributed. Financing of social policy is more a political choice than one of affordability. Persistent focus on affordability draws away from questions of how politics shape social policy and what determines how governments distribute resources.

Norms upon which social policy is implemented shape financing. Framing social policy around principles of equity, inclusivity, and solidarity can enhance social cohesion among citizens and stimulate government social spending. Universal provisions generate greater solidarity amongst citizens. Targeted schemes, on the other hand, impede mobilization for collective demand. The norms that underpin transformative social policy are foundational in enhancing a sense of citizenship to create demand for increased social spending.

Nations in Africa can free themselves from dependency on ODA and donor funds toward financial independence that inspires the sovereignty necessary for structuring appropriate social policy.

Abandoning racial language

Photo by Hennie Stander on Unsplash.

Photo by Hennie Stander on Unsplash. As racism remains a topical issue in public and scholarly discourse, so too do strategies for bringing about its end. In trying to create a future free of racism, there are those who believe that our linguistic patterns play a central role. One strategy arising from this perceived importance in South Africa relates to the role of ���racial language��� in our societies. While there are many South African articles which address the use of racial language in specific instances, such as in policy, hiring practices, university funding and/or placements, I will be considering the more general assertion that races should not be referred to at all. Such a view, as I will explain, supports the valid rejection of biological racial realism. However, by deeming all race terms to be meaningless it seems to lead us to a position in which we are unable to address racism.

Race talk, or racial language as its referred to in the South African media, is the use of racial terms (Black, white etc.) in a way that presupposes the usefulness of using such a term in some or other way. There are those who hold that the continued use of these terms upholds false categorizations which, in turn, lend themselves to racism. In other words, racial language is what reifies race and therefore, if we want a society free of racism, we ought to stop using racial language in all instances. Proponents of such a view sometimes refer to themselves as holding a position of ���non-racialism.��� This term is clouded by its prior uses in anti-apartheid activism as well as the South African Constitution of 1994. To be clear and specific, I will therefore not refer to this position as one of non-racialism, but as positing the abandonment of race talk.

The specific anti-race talk argument that I will address holds, firstly, that racism���the discrimination against people based on their race���is, and has historically been, a moral bad. Moreover, it manifests in relational ways of thinking, acting, and speaking that we should seek to end. To eliminate this racism, we can begin by abandoning racial language to reflect that such language fails to track anything meaningful in the world. In other words, the best strategy to end racism is to begin by altering our linguistic patterns of speaking, presumably altering our ways of thinking and acting. The anti-race talk position can be referred to as a sort of racial eliminativism, although perhaps devoid of some of the philosophical nuance it is afforded by well-established theorists on race, such as Phila Msimang.

The position to end race-talk finds its support in a curiously ideologically diverse set of groups including, perhaps ironically, both those on the Marxist left who argue that class is the primary (if not the only) useful social category, as well as neoliberal capitalists who assert that racial categorization gets in the way of meritocracy and undermines individuality. What is common among those who suggest discontinuing reference to race is the view that not only is the biological basis of race (eugenics) flawed, but the categorization is groundless in every possible sense. Proponents thus posit the invalidity of deploying racial language, which can be understood more simply as claiming that racial language is meaningless.

To understand what is implied when we say some word or term is meaningless, it is worth pausing on what meaning itself entails. There are many theories of meaning at our disposal, but one that seems to function particularly well, including with regard to race, is the causal-historical understanding of meaning. Saul Kripke developed the causal-historical theory as one in which the meaning of a term is explained by its historical patterns of use. Among other reasons, it is an appropriate theory for the consideration of race because it offers a plausible alternative to those which suggest that meaning primarily (or exclusively) arises from the speaker���s intentions.

Although it does not preclude the possibility that intention has a role in influencing meaning, it suggests that this alone is an insufficient reflection of how terms help to point out things in the world (what they refer to), as well as what they mean. Speaker intention sometimes fails to explain what goes on when a given term is used. If, for example, someone uses a racial slur and subsequently purports to have done so in a jovial and innocuous manner, this intention is insufficient as a moral justification for such an act. That is, even if the intended meaning was not discriminatory, the actual meaning might be. Although related to the intended and unintended effects, my argument is specifically that there is the possibility that the intended meaning of a term does not reflect the actual meaning in view of a certain history.

The causal-historical theory of meaning allows us to take account of the speaker���s intention while still holding that the slur carries some meaning arising from the ways it has historically been used. Such a theory lends itself to the nuanced consideration of who may say what, and why a theory based on intention cannot make sense of such concerns. To deny then that racial terms have meaning is to also suggest that there is no historical basis for such terms. While we might agree that there is no true scientific/biological basis for racial terms, it seems that their historical use has meant that now, racial terms seem to do some explanatory work in the world. Although the exact way racial terms have meaning is up for discussion, it seems difficult to deny that, throughout history, race talk has successfully lent itself to the classification of people on this basis. Although these terms are inherited from oppressive regimes, they have meaning.

Rekang Jankie, who in his eloquent discussion, made reference to my use of racial language in a previous piece, suggests that continued use of racial language unduly reifies race precisely because of its roots in eugenics; in other words, its causal history. Jankie suggests that the fallacious biological and original meaning of racial terms makes impossible the use of terms in a different sense. That is, it is not enough that we should actively criticize racial terms as falsely based on biology���any use of racial language affords purchase to this biological view even if it does not do so actively.

For Jankie, it is the continued use of racial language that upholds racialism and enables racism. Such a view posits that it is language that reifies race where it would otherwise have no reality. This presumes an answer to a chicken-and-egg question. It is more probable that the reality of race occurs in tandem with the use of racial language, rather than simply as a result of it. It is also not obvious that the abolition of racial language will spell the end of race as a social reality, and as the basis of discrimination. Moreover, just because biological understandings of race were scientifically incorrect does not mean that the terms were never meaningful. This becomes clearer when we see the scientific outcome of eugenics too as a social construction.

There is often a sharp distinction drawn between race as biologically grounded and race as a social construct. Those who posit that racial categorization is useful generally uphold one of these two views and they are typically seen as mutually exclusive. It is possible to consider that that these views are different not because of their position on racial meaning but because of their capacity to function in the world. Given its profound falsity and its justification as a product of bad science, eugenics itself can be thought of as a social construction. That is, those who felt the need to justify their racism and exploitative practices with supposed scientific fact would search for basis, theorize about eugenics, and then go about their racist practices with little concern that they might be (scientifically or morally) wrong.

This fallacious eugenicist basis of racial terms does not imply that the terms had/have no explanatory value, it suggests precisely the opposite. Eugenics sought to provide a more generally acceptable basis for an already prevailing set of socially reified, racial categorizations (there are/were many others too���German/Jew, the caste system, etc), for those who wanted to take advantage of such categorizations. It served as a ���scientific��� and thus supposedly indisputable justificatory basis for subjecting Black people to the horrendous reality of slavery, among other things.

Understood like this, the view of biological racism is not in opposition to the view that race is socially meaningful but subsumed by it. It explains the way in which contemporary forms of race and racism came to arise���including its (re)invigoration through the bad science of eugenics. If this holds, then racial language appears to denote something socially meaningful. This is upheld by acknowledging the fact of racism wherein we admit that race explains something if nothing other than a basis of discrimination. Those against the use of race talk, then, face a difficulty in addressing racism if they deny themselves the conceptual and linguistic tools to do so.

Those who reject the justifications for race talk, as I have been describing them, see themselves as responding to the problem of racism. A difficulty arises with this view when we consider our capacity to name, or point to, racism as such. If racial terms are thought of as meaningless in every sense, then it follows that an apparently racist instance must also be called meaningless. This is because the use of racial words, for the non-racialist, are seen as meaningless and devoid of reference. If such a line is taken, it is unclear how we would ever be able to accuse anyone of racial discrimination despite the fact that this is precisely the sort of thing we wish to address.

For example, if someone in a company were to say, ���I do not hire black people here because of their incompetence,��� those who suggest the abandonment of racial terms would hold that the term ���Black people��� is an empty signifier, so the statement is meaningless. They would also argue that this person ought to stop using the term. Nowhere in such a case, would an anti-race talk assertion address the problem that Black people are explicitly being discriminated against. The potential consequences to this way of thinking are wide-reaching.

There is a great risk attached to this commitment if upheld by racist people and institutions. It will be quite simple for them to escape the charge of racism by merely appealing to the absence of race talk in their language and policy, despite the fact that racism need not be explicit for it to remain present. Moreover, the anti-racist proponent of this view I have been discussing would be restricted by their linguistic arsenal, and not able to suggest otherwise. To put it simply, non-racialism disallows us to name racism and to therefore hold racist people and institutions to account. In this vein, Phila Msimang argues that, ���so long as it is the case that racial concepts have social currency and correlate with lived experiences within the social world, racial terminology is a useful tool to track social facts associated with race.���

Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah also posits that racism must be ended before racial terms can be abandoned. Appiah suggests that racial identitarianism is not something that should be promoted, but nevertheless, there is a ���place for racial identities in a world shaped by racism.��� We ought to apply ourselves to the question of how we might apprehend the way(s) in which race bears on subjectivities, rather than to cease referring to it at all.

March 14, 2021

Unearthing the past

Robben Island / Mayibuye Archive.

Robben Island / Mayibuye Archive. For most South Africans, the 29th of March is an unremarkable date, a day like any other. Few recognize the name Dulcie September, or know of her brutal murder in Paris on this day. September was the ANC chief representative for France, Luxembourg and Switzerland in the 1980s, and was the only high-profile ANC member to have ever been assassinated outside of Southern Africa. As Rasmus Bitsch and Kelly-Eve Koopman write in Africa Is A Country, ���Her murder has never been solved and September is not a household name in South Africa. Neither of those things are coincidental.���

So, who exactly was Dulcie September? At the time of her death she was 52 years old, and had devoted her entire life to fighting apartheid. A short while after her six-year imprisonment for organizing with the National Liberation Front in October 1963 in Cape Town, where she was from, she departed for Europe and joined the exiled ANC which was by that point already banned by the apartheid government. Until recently, her name existed in deep obscurity, but thanks to recent efforts by the investigative research outfit Open Secrets (which produces a podcast with Sound Africa called ���They Killed Dulcie���), as well as the publication of Evelyn Groenink���s book Incorruptible (which is also about the murders of Chris Hani and Anton Lubowski), the story of her murder is starting to break through.

A new documentary, Murder in Paris, makes a notable contribution to this welcome trend. The two-part film is set to be broadcast on a channel of South Africa���s public broadcaster on Human Rights Day on the 21st of March (which commemorates the Sharpeville massacre), and on the 28th of March, which is the day before the 33rd anniversary of her assassination. Directed by Enver Samuel, whose most recent films include Indians Can���t Fly in 2015 (about the death in detention of anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol), as well as Someone To Blame in 2017 (about the eventual inquest into Timol���s death), the film, which features Groenink’s quest to get to the bottom of Dulcie’s murder, adds to a body of work that seeks to relook at unresolved and buried apartheid traumas. This week on AIAC Talk, we are pleased to be joined by Enver and Evelyn to discuss the film.

The film���s release comes at an apt time where many South Africans have spent the last decade or so reflecting on whether we have been able to meaningfully reckon with the horror of our apartheid past. It was not long ago that as the #BlackLivesMatter protests in the United States prompted some to call for an American truth and reconciliation commission, that South Africans again wondered about how effective our own TRC was. There are many families��� like that of Ms September���s��� who until now don���t know who took their loved ones, or where they disappeared to. For many, the scars are still fresh, the anger still deep. So next on this episode, we want to talk to Madeleine Fullard, who leads the Missing Person���s Task Team, an organization that emerged from the TRC and which is responsible for finding the remains of murdered anti-apartheid activists.

Catch the show the show on Tuesday at 19:00 CAT, 17:00 GMT, and 13:00 EST on YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

On last week���s episode, we had on Shireen Hassim, Rama Salla Dieng and Rosebell Kagumire to commemorate International Women���s Day and discuss the struggle for women���s liberation on the continent. It was a wide-ranging conversation that also touched on the ongoing protests in Senegal as an example of where credible allegations of sexual violence are side-lined by movements for social change.

Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but as usual, best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

March 12, 2021

The value of care

Soccer in a yard in Newlands, South Africa during the lockdown. Credit James Oatway for the IMF via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Soccer in a yard in Newlands, South Africa during the lockdown. Credit James Oatway for the IMF via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. This post is from our series of reposts from Kenyan publication The Elephant. It was selected by William Shoki.

In 2020, I learned the elasticity of time. How every new day arrives with so much need for adaptation and emotional processing that the day before it feels like it happened 10,000 years ago. How the ���old normal��� of what I have taken to calling ���the before times��� can be imperfectly resurrected by rituals we used to participate in without concern, but which now seem worryingly, potentially harmful���my sister-in-law blowing out candles on her birthday cake, for instance. Are we still allowed to share birthday cake?

In 2020, I learned the visceral life-saving power of care. How much all of us who are managing to navigate the pandemic are being given that gift of being able to manage by���and at the expense of���a newly-recognized class, the ���essential workers��� whose jobs require them to care for us. These are the people who keep our hospitals functioning, the people who keep our grocery stores open and make it possible for some of us to move our consumption online, the people who keep freight trains and long-distance trucking going, and���in island nations���the people who work at our borders and our ports. They are also people on whom our lives depend: factory workers who make personal protective equipment (PPE), sanitation workers, and janitors at hospitals, bus drivers, meatpackers, and farm workers.

2020 makes me think of the poignant conclusion American journalist Barbara Ehrenreich drew, a generation ago, from her experiments with trying to live on a minimum-wage job in Bill Clinton���s America (spoiler: you can���t���not in any way that encourages human flourishing). Speaking of the attitude she thinks we ought to adopt with respect to ���the working poor���, Ehrenreich insists that ���the appropriate emotion is shame���shame at our own dependency . . . on the underpaid labour of others.��� Presenting this exploited and neglected segment of the labour market as ���the major philanthropists of our society,��� Ehrenreich explains that ���[w]hen someone works for less pay than she can live on���when, for example, she goes hungry so that you can eat more cheaply and conveniently���then she has made a great sacrifice for you, she has made you a gift of some part of her abilities, her health, and her life.���

I have considerable sympathy for the view that those of us who live well should indeed feel great shame in the face of all the people who provide us with the things we are not able to provide for ourselves. Every paved road, every functional traffic light, the towel I used after my morning shower; I couldn���t provide these for myself no matter how many bootstraps you might give me. But writhing in shame is neither a productive attitude nor an interesting one. It will not absolve our past heedlessness of our dependence on people whose labor is essential���and is devalued so that it can be affordable for us. It will not build a world in which all of the people we now see as necessary are adequately valued.

It has been a really hard year. But oddly, I still find bits of hope and consolation in the fact of this being a truly global experience, possibly the first of my lifetime. Every year is hard for the people who get cruelly sorted into underclasses and marginal subject positions. And there are events so devastating that they reach even into pockets of privilege and become a country���s (or a region���s) shared experience. But this? Everybody, everywhere, has been touched by this pandemic somehow. While the impacts are of course differently distributed, we are all grappling with the same crisis, and I can���t help but wonder whether this might be a moment in which we���all of us, as human communities���can start to see the enormous and under-rated value of care. So many of the people who have been shoved to the margins of global power structures���whole countries of the global South, indigenous populations within wealthy global North nations���have been revealed as people on whom our multinational inter-connected lives depend, or as ���elders��� who have a lot to teach us about community survival.

Those of us who live well should indeed feel great shame in the face of all the people who provide us with the things we are not able to provide for ourselves.

The first piece I wrote for The Elephant was an analysis of strands of decolonization theory that are resonating today through the Black Lives Matter movement (BLM). Black Lives Matter began as an African-American activist movement to honor blackness and to protest the culture of policing implicated in the killings of unarmed black boys (Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown). Less than a decade after its emergence in the United States, the movement marked 2020 as a year of global protest against American policing in the wake of the killing of yet another unarmed black man, George Floyd. I noted in that first piece BLM���s commitment to ���unapologetic blackness��� and to building inclusive, intergenerational solidarity against state-sponsored violence, both locally and around the globe. I noted too the unmistakable echoes of decolonizing theorists Frantz Fanon and Sylvia Wynter in BLM calls for solidarity with (for love of) the men and women of color whose lives have been taken from them.

Both Fanon and Wynter take on the discursive politics of domination that render our social worlds places where people of color combat a perception that they must prove their humanity���or, even more toxically, learn that they cannot ever prove this humanity of theirs conclusively enough to establish themselves enduringly as persons of value. In her analysis of these ongoing struggles for recognition, Wynter indicts Eurocentric-North American epistemological commitments to hierarchy and to the belief that those at the top of the hierarchy are both the most worthwhile and the most fit to survive. For her, the monetization of everything in our social worlds results in a warping of our capacity to see humanity, and the consequent capacity to see the value in all human lives. To cast her point in the language of the lessons of 2020: we must rethink what counts as value, in order to learn how to care (better).

Going back to what I wrote in 2019 after living through 2020 brings me that sense of elastic time I cited at the outset as one of this year���s lessons for me. I see in all of the pieces I have contributed to The Elephant a thread of awareness that survival and solidarity are linked. But it has taken the events of this past year for me to fully appreciate how much decolonization theory and social-justice activism depend on care���both the practice of care work and the theorizing of ethics of care. And it is only in retrospect that I see so clearly why empathy-building has been (has needed to be) such a central goal of the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements that I was writing about here and elsewhere throughout 2019. Empathy can be built into solidarity, which (when well directed) manifests as the care that keeps us alive. This observation, I should note, is conceptually a restatement of critical race theorist and Occupy Wall Street activist Cornel West���s dictum that justice is what love looks like in public.

Black Lives Matter has been doing this empathy work���asserting that black lives are indeed among all the lives that matter���through protests and online awareness campaigns that confront and contest police narratives of criminality and justified response through pushing into public consciousness the names, faces, and life stories of individual persons of color who have been killed. Their success in building a solidarity that can withstand law enforcement���s hostility and the public���s apathy was made evident in 2020; George Floyd���s name, face, and story have been in the foreground of the protests that have taken place in countries as far away as New Zealand.

In similar fashion, the #MeToo movement invokes traditions of solidarity and community-building that very clearly aim at normalizing and propagating empathy, and are embedded in its very name. ���Me too��� was the catch-phrase around which Tarana Burke, an African-American community activist against sexual violence, built her outreach efforts (which, years later, were introduced to the global online world through actress Alyssa Milano���s tweet, just as news stories of Harvey Weinstein���s sexual predation were first being published). Burke���s explanation of this catch-phrase that became, first, a community-organization project, then an online archive of survival testimonies, was that it was the phrase she wished she had had the presence of mind to utter to the first young girl who disclosed a story of sexual abuse to her. In my 2019 analysis of the ���black roots��� of ���me too���, I argued that this phrase needs to be understood within the context of African-American musical and linguistic conventions: a call demands a response. ���Me too���, I noted, is a response resonant of these African-American call-and-response traditions, traditions that build relationship and community through recognition of shared perspectives: ���me too��� ��� ���you too?��� ��� ���yes, me too.���

Frantz Fanon, one of the most fiercely beating hearts of decolonization theory during the days of postcolonial independence that birthed the Third World, knew the importance of both empathy and care in building independence movements and new nations. His account of how Algerian independence forces reached the point of realizing that their war against French colonizers would succeed (L���An V de la r��volution alg��rienne, published in English as A Dying Colonialism) is rich with examples of both. Pan-Africanism, in all its variants, is built on appeals to ���feeling with��� (the literal meaning of ���empathy���). What is new���what 2020 has given us���is an archive of heart-breaking examples of the need for care labor and the politically transformative power of care as an orientation towards others. I think, for instance, of the singing and music-making on balconies around the world as community responses to ���lockdown isolation���, and the heroic decency of hospital workers who connected people on their deathbeds to loved ones via iPads so they didn���t die entirely alone.

Those of us who are gleaning inspiration and encouragement from online streaming during lockdowns of 2020 might recognize ���black traditions��� of care work as they are modelled (imperfectly) in Netflix���s The Queen���s Gambit, through the supporting character of Jolene. The show has been criticized for its instrumental use of its most significant character of color; Jolene is present in the story only as a source of care for the white girl whose life is the story���s focal point. That criticism is fair���Jolene is not drawn with as much nuance as she deserves, nor is her story given adequate weight���but there is something I see in the show���s presentation of her that goes beyond these criticisms. Yes, as a character, she is subordinated to Beth, the center of the story. (And yes, that is a criticism that needs to be leveled against the show; it ought to bother us that black characters in the show are personified only slightly more than chess pieces.) But it misses the power of what I saw in how Jolene cares. This power of her care is notably (perhaps only?) on display in the scenes where she comforts Beth after the death of the man who taught her to play chess.

Empathy can be built into solidarity, which (when well directed) manifests as the care that keeps us alive.

I���m not at all certain that I would have seen those scenes the way I did if I had watched the show without having lived through 2020. Through this lens, however, I see something about the way Jolene was able to acknowledge the dark, unfair elements of life and death and was able to comfort with clear eyes (characterizing the main character���s unexpected grief as ���biting off more than you can chew���) that has stayed with me as emblematic of the orientation to care that I think we need in the wake of 2020.

In the white-dominated, (post)British-colonial cultures that raised me, there is a standard response to grief and trauma that involves dismissing or downplaying the trigger incident (it���s not so bad) and encouraging minimized emotional reactions (stiff upper lips). Jolene���s care in the face of grief does neither of those things; she can acknowledge the devastating, shattering experience of grief that Beth is undergoing and can sit with Beth through it. In this model of care, grief is not nothing, or a little thing, or not so bad. And the person who is grief-stricken is not broken, needing to be fixed. The grief-stricken person has been wounded and, in their healing, needs care from others���needs empathy and the authentic comfort that we find in solidarity. All of this strikes me as true of trauma as well as grief, which is why I see ���how Jolene cares��� as an attitude so well suited to our pandemic times.

All of us who have experienced 2020 have shared a year which has been traumatic for many. Practicing ���how Jolene cares��� is a project of acknowledging these individual traumas in our ongoing encounters with those who carry them as burdens. And it is a project of searching for ways to give practical, basic-needs-oriented care���not in the triage-inflected leveling-down of care to the barest necessities that characterized so many rushes to lockdown in 2020, but with attention to the other���s needs-within-their-healing-process that, for many of us who have wrestled with either grief or trauma (are they always distinct things?), is the ground out of which trust might be nurtured and grown and is the first nascent re-connection to a world that has been so wounding. If sustained practice of this care model also teaches us to see how much care we are receiving from others every day, all the time, it has the potential to be radically transformative���in exactly the way that Fanon and Wynter���s decolonization theories urge.

At the very end of 2019, I wrote a piece about Haiti in which I offered an extended digression on a New Year���s Day tradition that builds and celebrates solidarity (January 1 is also celebrated as Haiti���s independence day, the anniversary of its decolonizing declaration of itself as a free black nation). This tradition, the making and sharing of a gourd-based soup known as joumou, is a ritualized act of care through food, intended to inspire Haitians to re-dedicate themselves to each other in the coming year, and to build upon the promise of human dignity that was the Haitian Revolution. In that piece, I urged readers of The Elephant to honor the spirit of Haiti���s New Year���s Day tradition, and to recognize the role that Haiti���s revolution has played in creating a world that slowly���incrementally, but undeniably���is becoming less hostile towards blackness. Returning to my discussion of joumou with 2020 behind us, I want to bring to the fore the idea of food as love���something I think I elided in my earlier discussion of food as political symbol.

Many years ago, as a much younger woman, I waitressed in restaurants. I hated being treated like a servant by restaurant patrons, but there were many aspects of that work that I enjoyed and that have stayed with me over the years as behavioral habits. The thing I loved the most about waitressing was being able to bring someone a steaming plate of hot food on a cold day. (This was when I lived in Canada; there were many cold days.) That act of giving one person something they need to sustain their life and well-being was always a deep pleasure for me, because it always made me feel deeply connected to all my fellow human beings. This, I think, is the essence of what is being ritualized in the Haitian tradition of sharing joumou on the first day of the new year. Giving care���giving love, giving what is needed to sustain life���and receiving it can, at its most powerful, form connections among the people in a particular care-interaction that can also weave them all together into a larger community.

When I first discussed the idea for this article with my editor at The Elephant, his judgement was that he too thought ���we should end the year with some empathy.��� It took a long time to pull together my thoughts���so long that I rendered an end-of-year wish for empathy outdated. What I now offer readers instead is my profound hope that we can begin 2021 with empathy enough to make the new year one in which each of us is empowered by the care that we receive, and by the care that we give.

March 11, 2021

South African history through new ears

Reconstructed amaQhugwane near the main entrance of uMgungundlovu. Image credit JMK via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.

Reconstructed amaQhugwane near the main entrance of uMgungundlovu. Image credit JMK via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0. We���re now three months into 2021 and while the dawn of a new year and the global rollout of COVID-19 vaccine provided a much-needed preview of a new era in the pandemic, for many very little has changed. For those of us based outside the continent, this ���new normal��� means that it is unclear when we will be able to return to our research sites, our second homes, our families. There is no way to know how long it will be before travel restrictions are lifted or when we will feel safe enough to venture beyond the confines of our socially distanced pandemic bubbles. While the warm embrace of streaming services have provided much-needed escape for many from the quotidian coronavirus struggles that wear us all down, for others podcasts represent a welcome alternative that combines information and entertainment. And the listening options available for those interested in the Diaspora are substantial.

From podcasts focused on current events/news to Afro-Diasporic music to African Studies, the options available for Africanists are plentiful but they also tend towards the contemporary. They also tend towards the informational, which is true of the format broadly. But what is the next phase in podcasting generally, and specifically in an African Diasporic context?

In the early 1900s, amateur historian, James Stuart recorded accounts of life in the Zulu capital uMgungundlovu. While his recordings were not aural, a new project from the University of Cape Town���s Archive and Public Culture (APC) research initiative attempts to imagine what the mid-19th century would sound like. uMgungundlovu: through the eyes of the izinceku demonstrates the possibility of this experiential approach. Directed and produced by Dan Corder and combining an original musical score by Thokozani Mhlambi and recitations of firsthand accounts of precolonial KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) history, uMgungundlovu immerses the listener in a highly localized soundscape in the former Zulu capital of the same name.

Launched in September 2020, this project represents the first of a series of podcasts based on materials contained within the APC���s 500 Year Archive, a digital research project designed to allow interested parties ���to dive into the southern African past up to five centuries before colonialism.��� The podcast project is also geared towards recovering ���South Africa���s past before colonialism,��� according to Carolyn Hamilton, NRF Chair of the APC project and a noted historian/anthropologist. ���We are sharply aware of the dearth of accessible, publicly appealing, historical materials concerning South Africa���s past before colonialism . . . especially in local African languages,��� Hamilton explained in an interview earlier this year:

Remedying this situation is challenging. For a start, very few researchers work in this area. You might well ask why that is the case. One of the reasons is that there seems to be very little source material and a lot of what there is, is scattered and firmly stitched up in colonial thinking and categorizations. Actually there is quite a lot of material but it is tricky to mobilize in publicly accessible ways.

The two-part podcast offers a sonic interpretation of life at Zulu king Dingane���s capital of uMgungundlovu in the 1830s. In particular, the podcast centers on accounts of life in the Zulu capital recorded in the early 1900s by amateur historian, James Stuart and recited in isiZulu for the production by historian Mbongiseni Buthelezi. Testimonies by Lunguza kaMpukane,��Thununu kaNonjiya��,��Ngidi kaMcikaziswa,��and��Sivivi kaMaqungo each appeared in a school reader, uKulumetule, in 1925 and, later, in volumes of the James Stuart Archive, the multi-volume project collecting interviews with Stuart���s informants. Although the pieces presented in this podcast are mediated by Stuart (a fact that has garnered considerable historiographical debate over the years), Hamilton explains that the accounts do not ���stand as authoritative incontrovertible history but as pieces from the archive.���:

We cannot, and do not, claim that these are exact versions of what they said, but the accounts come some way down that road. On the ���do not��� claim: we want these pieces not to stand as authoritative incontrovertible history but as pieces from the archive. Thus, when you encounter the podcasts you are continually directed into the archive yourself. Even if these pieces could somehow be shown to be verbatim what these men said, unmediated by anything, these would be their particular views, their particular memories. Others might have seen things differently.

Even the musical score of the podcast continually directs the listener into the archive. The musical excerpts are from cellist and composer Thokozani Mhlambi‘s ���Ukudibana kwezimpondo��(The meeting of the tusks).�����In the spirit of the project, Mhlambi approached the composition process as an opportunity to disentangle the historical site of uMgungundlovu from the oversight of European oversight; he believes that ���creative methodologies are the ones best posed to re-shape our understanding of the site based on African perspectives.���

There are already plans in place to expand on this project, including commissioning translations of the uKulumtele excerpts into seSotho and English ���to foster multilingual experiments, experiences and engagements.��� (You can stay up-to-date with the project���s progress on the 500 Year Archive Website.)

Is the future of podcasting a show featuring exclusively isiZulu retellings of 19th-century African life combined with an original soundscape composed with a revolutionary ethos? I certainly hope so. In this era of travel restrictions and social distancing, perhaps the next evolution of the podcast format will be towards experiential podcasts that combat wanderlust and homesickness by depositing the listener in a different place and time. uMgungundlovu: through the eyes of the izinceku charts an exciting path forward.

Death by betrayal

Photo by Hugo Ramos on Unsplash

Photo by Hugo Ramos on Unsplash A fellow journalist complained recently about being mistreated by the Medical Association of Tanzania (MAT) president, Dr Shadrack Mwaibambe, during a phone call. The reporter wanted to find out a few things about the current COVID-19 situation from the leader of Tanzania���s healthcare staff union. To the reporter���s annoyance, however, instead Dr. Mwaibambe shouted at him, calling him names and even declining to answer the reporter���s questions.

I am convinced that there is only one explanation as to why Dr. Mwaibambe felt the urge to react the way he did: a guilty conscience. And I would like to be fair with him by pointing out that he is not alone. Each and every person in Tanzania who knows that there is a responsibility they shirked in relation to COVID-19 would have reacted in the same way as the medical doctor did. These include leaders of trade unions who, for reasons best known to themselves, have failed to protect both the safety and welfare of their members amidst a public health crisis that has claimed the lives of so many Tanzanians.

In recent days, with reports of the arrival of a new and far deadlier coronavirus variant in Tanzania, death announcements have been circulating on various social media platforms in rapid succession. Reports of deaths have been so frequent that the word pole, Swahili for sorry, trended on Twitter. Many of the deaths announced are of high-profile, current, and former senior civil servants, university professors, and religious leaders. It is not known how many ordinary Tanzanians die every day given the authorities��� reluctance to record case counts and share updates with the public.

The new wave of COVID-19 did Tanzanians a favor by making the government abandon its false and dangerous claims that Tanzania was COVID-free. It has forced President John Magufuli to admit that the deadly virus is indeed present in Tanzania, though ignorantly blaming it on Tanzanians who went abroad to get vaccinated. Despite the alarming number of deaths, Magufuli has insisted that he does not intend to lockdown the country, therefore allowing businesses to go on as usual���a risky decision, but welcomed by many Tanzanians. The government has nevertheless urged people to take precautions against the disease, including, of course, using traditional medicines.

It is not clear how Tanzania is going to contain the spread of COVID-19 when schools and colleges remain open and protection measures are limited. No doubt students, their tutors, and staff will be exposed to the virus and risk losing their lives. A few privately-owned companies and entities have closed their offices and renewed their arrangements of working from home. Many public institutions, however, haven���t adopted that arrangement and workers in this sector�� are most often reliant on public transport, where safety measures are anything but desirable.

Despite these concerns, not a single trade union has so far come forward to protest the government���s stance on allowing business as usual. In fact, the utter indifference and lack of solidarity in Tanzania���s labor fraternity is blatant. One case involves the reprimand of Professor Elifas Bisanda, Vice Chancellor of the Open University of Tanzania, for merely acknowledging the presence of COVID-19 in the country and urging the university community to take necessary care. For this Professor Bisanda was reprimanded by the Ministry of Education and required to apologize, with no support from the Tanzania Higher Learning Institutions Trade Union (THTU).

There are few exceptions, however, with the Tanganyika Law Society (TLS) providing a model of what workers and professional associations are supposed to do during a pandemic of this nature. On February 19, the Bar Society issued a statement demanding the government tell people the truth about the presence of COVID-19 in the country. Uncharacteristically, the TLS revealed that between January 1 and February 19, a total of 25 of its members died of various diseases including COVID-19, and it urged authorities to ramp up protective measures.

There are many explanations for the lack of militancy in Tanzania���s trade unions, but the biggest factor has been state interference in unions��� daily operations. This is combined with the infiltration of trade unions by cadres of the ruling Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM). The relationship between the trade unions and the ruling party is visible at local level where CCM district or regional leaders make their way into union leadership positions, or former trade union leaders contest for public office on the CCM ticket.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the fragility of Tanzania���s democracy. Power rests in the hands of a few, who have the ultimate luxury to decide how they can wield it, with little to no accountability to the citizens who elected them. Tanzania���s workers are counted on to produce the wealth of the country, but their unions are participating in their sacrifice at the altar of the egos of the ruling elites.

March 10, 2021

If we lie down, we are dead

Image via Deux Heures pour Nous, Deux Heures pour Kamita Facebook Page.

Image via Deux Heures pour Nous, Deux Heures pour Kamita Facebook Page. This post forms part of the work by our 2020-2021 class of AIAC Fellows.

���Nan lara an sara! Nan lara an sara!���: A crowd of roughly 300 students throngs the ���freedom square��� and chants defiantly, clenched fists in the air. The scene is the campus of Universit�� Joseph Ki-Zerbo, in Ouagadougou. The students are members of Deux Heures pour Nous, Deux Heures pour Kamita (Two Hours for Us, Two Hours for Kamita; referred to here as DHK). ���Kamita��� is an Afrocentric term, designating the continent. The group is a throwback: A radical student organization dedicated to ideology and analysis, that intends to break from the complacency that has taken hold on African campuses in recent years.

As the meeting builds, a young man roars in the middle of the circle, a megaphone in his right hand, his left hand following the rhythm of the crowd: ���nan lara!��� (if we lie down!). The crowd responds ���an sara!��� (we are dead!). After several minutes of call and response, the young man opens the meeting. ���Comrades, welcome! Thank you for dedicating two hours today for our beloved Kamita. Today, we seek wisdom from one another in addressing the topic before us: the presence of French military on the free and independent land of Burkina Faso.��� He proceeds to lay out the agenda of the day, and the modalities for taking the floor.

Meetings like this one, which I attended in August 2019, take place every day, from 1 to 3 pm, on the campus. They have continued even during the COVID-19 pandemic which compelled attendees to wear facemasks; I have kept in touch with members and interviewed leaders as well as occasional attendees. The meetings are arranged in an open space and amplified with loudspeakers. No position is invalid. No topic is taboo. The group emphasizes innovative radical thinking about democracy, social change, and liberation. But weak arguments are booed, while carefully crafted ones are applauded���especially when they are considered ideologically sound, in the tradition of Frantz Fanon or Thomas Sankara.

Student militancy has revived in Burkinab�� public universities over the past decade. As older student organizations become ossified and discredited, emerging ones seek credibility by leaning toward pan-African ideologies. The country and its politics offer a particularly fertile scene for the youth to develop ideological and political organizations that aim to transform society. Slogans such as ���Plus rien se sera comme avant!��� (Nothing will be as before!) and ���Nan lara an sara!��� signal such a desire for change and willingness to act. DHK represents a new militancy, with power and potential���but also contradictions and challenges.

DHK formed in 2013, a time when social discontent was growing in Burkina Faso. Workers��� strikes paralyzed many sectors, including higher education. Civil society groups and opposition parties were engaged in a power struggle against then-President Blaise Compaor��, who was attempting to pass a constitutional amendment to extend his rule. The academic community was caught in this malaise. It was in this context that students at Joseph Ki-Zerbo University chose to experiment with a new form of participatory democracy by creating a performative venue on campus.

Over the years, DHK has become prominent among the burgeoning youth movements in Burkina Faso. Beyond the boastful, intellectual verbiage and rhetorical skills that its members show, the organization has built a reputation as a leftist movement that focuses on social justice, political emancipation, and environmental stewardship���both at the national and international levels. In February 2019, for instance, the organization sent a delegate to Venezuela ���to support the people of Venezuela in their struggle against imperialism,��� a post on its Facebook page reads.

Developing and sustaining a pan-African ideology on a campus where student conferences and intellectual exchange outside the curriculum are almost non-existent is a challenging task. Yet DHK has managed to establish a respected forum where uncensored conversations take place every day, gathering up to several hundred attendees. Every week, a series of discussion topics is chosen and published on Facebook. Often, they respond to the news of the day. At other times, the reflection is oriented toward historical events. There are guest speakers, such as Kemi Seba, the Franco-Beninese activist, or Yacouba Sawadogo, a Burkinabe farmer known as ���the man who stopped the desert��� for successfully bringing to life a 40-hectare forest on a barren land.

The daily gatherings constitute moments of deliberation, healing, strategizing, and planning. On the day that I attended, social media abounded with polemical information about the alleged opening of a new French military base in Djibo, a small northern town 45 kilometers from the border with Mali. The meeting was an opportunity to condemn the base and discuss the role of France���s counterterrorism activities in the region. Participants equated France���s current presence with its 19th-century pacification doctrine that justified colonialism. ���We are inviting France to the school of civilization. We invite her to finally learn to be a nation that respects the sovereignty of other nations,��� one man said.

Sometimes, the organization brings speakers who do not have formal education, such as farmers and small craft traders, challenging the perception of what constitutes knowledge in a university setting. This initiative is ���an uninhibited approach to learning by uninhibited students who have conscience that development is homemade,��� Bayala Lianhoue Imhotep, secretary general of DHK, told me. ���No one has the monopoly of imagination. Our farmers are an inexhaustible source of knowledge if we cared to listen to them.���

At first, campus authorities rejected DHK for its radical positions concerning the university and student life. They sought to shut it down and push it off campus. Now, civil society movements beyond campus including Balai Citoyen seek them out. They constitute a force that can mobilize adherents, an antidote to the general fatigue among youth following the 2014 popular revolution.

DHK represents in many ways a revival.

Universit�� Joseph Ki-Zerbo has a tradition of being a center of social movements, with student strikes that often led to a general paralysis of the capital city. The roots of Burkinab�� student militancy go back to student unions in the 1950s in Dakar and in France, where Burkinab�� and other francophone Africans went to study. Those unions were an avant-garde in political mobilization, a breeding ground of activists in the late colonial period and after independence.

In the early post-independence era, student activism aligned ideologically with the emerging political tendencies in the country. In 1966 the Voltaic Student Union supported the popular insurrection that ousted President Maurice Yameogo. The successive military regimes did not favor the emergence of a strong student unionism. However, during the Sankara years (1984-1987), college students mobilized to support the revolution. In the following two decades, student activism became progressively belligerent toward the Compaore regime. In the 1990s when the Structural Adjustment Programs compelled the government to adopt a much more democratic attitude, granting civil liberties, student militancy reclaimed a momentum. While student militancy never ceased to exist, it suffered in its vivacity since internal divisions and state repression weakened toward the end of the 1990s.

Recent renewal of political consciousness among Burkinab�� youth took form through events such as the assassination of the investigative journalist Norbert Zongo in 1998, long worker strikes in 2011 and 2015, student protests leading to violent confrontations with police, and the closing of the university for over three months in 2008 and 2011. Other contributing factors were changes in Franco-African political dynamics following French intervention in C��te d���Ivoire in 2010-11 to topple President Laurent Gbagbo, along with a persistent perception that the international community is hypocritical. Along the way, the memory of Thomas Sankara and his political discourse have re-emerged in popular music and activist rallies.

What is the potential of this revival? On one hand, student militancy today has inherited unresolved structural problems and grievances from their predecessors: deficient infrastructures, mismanaged academic calendar, deteriorated social services, etc. On the other hand, however, the ideological foundation behind student militancy is much more profound. Student activists are not only seeking to resolve their immediate needs, but they question the root causes of their predicament. While their struggle is locally rooted, it is open to other currents from the South. They often extrapolate their perception of inequalities at home with the struggles of other peoples elsewhere such as in Palestine, Venezuela, and Taiwan. They adhere to an Afro-centric understanding of history in their attempt to take control of their destinies as young Burkinab��.

For groups such as DHK, the traditional student associations and unions have become irrelevant, not because they lack grievances to address, but because they do not propose any sound ideology to solve them. DHK positions itself as an anti-imperialist movement, but also one that is opened to the struggles of other contemporary Black liberation movements. At the August 2019 meeting where attendees discussed French counterterrorism in the Sahel, some participants pointed out that the French could easily rid the Sahel of its insurgent groups if France really wanted to���peddling some conspiracy theories that were already circulating in the social media.

DHK is a promising unconventional revival activist group that promotes intellectual and democratic debates. Since its creation seven years ago, it has grown in membership and its ability to mobilize for action. At times however, it can be provocative in its ideas and approach when it connects with controversial figures such as Kemi Seba or when it takes side in some global issues without expertise in their historical complexity such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Nonetheless, this revival is taking place under the radar of most scholars and media attention, who often gloss over it as ���growing anti-French sentiment.���

In Ouagadougou, university student militancy is the last stronghold of students��� civil discourse. It is one that still grapples with its own issues, but nonetheless is ideologically promising. As foggy and muddy as some of their thoughts and ideas may be, the youth of DHK are informed by their quotidian reality. It is an ideology rooted in a Sankarist ideology that is daring and even risky at times. But this discourse still represents the clearer demarcation line between civil discourse and what is perceived as growing radical or fundamental discourse in Burkina Faso. Unlike the growing non-state armed movements that are terrorizing the country, student ideological militancy is disruptive, but it is still organized within the limits of free speech and freedom of association guaranteed by the constitution.

Today, the days of grand pan-African reveries espoused by the likes of Kwame Nkrumah and Thomas Sankara seem far behind. The dominant neoliberal economic systems that African nations have adopted and the persistence of neocolonial meddling in the post-colony blunted Afrocentric idealism. Even in academic research, we talk about it in the past and we do not envision it in the present. Two Hours for Us, Two Hours for Kamita gives us a compelling case study to rethink that position.

People are the state

Image credit the Government of South Africa via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

Image credit the Government of South Africa via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. This post forms part of the work by our 2020-2021 class of AIAC Fellows.

A tide of populism and authoritarianism on both sides of the Atlantic has facilitated the rise of particular groups to power and underscored that political control of the state can produce significant changes in society. These events highlight that it is people working within the state that control how government institutions operate and produce effects that impact society.��Rather than impersonal institutions that reflect normative criteria, these dynamics suggest that people are the state. But what are the implications of conceptually framing the state as people? What might happen if different groups of people were able to transform state policy based on the principles of social justice?

I tell that story in my new book. The HIV/AIDS movement in South Africa���constituted by activists, healthcare workers, NGOs, and others���occupied the state to transform policy, renovate health institutions, and sustain the lives of people living with HIV. The movement leveraged political principles developed by the anti-Apartheid movement to build a broad coalition that changed national HIV policy and increased access to treatment through institutional transformation. The result was a revamped state health system. The HIV/AIDS movement���s struggle shows how the state can enable the representation of different voices in a pluralistic society.

The campaign for treatment access underscores that it is people that produce social effects associated with states, and that activists, NGOs, and other entities can alter policy and transform state institutions to produce dramatic changes in society. The South African HIV/AIDS movement was able to occupy the state to expand treatment access, an outcome that required overcoming the opposition of a powerful group of state elites that stringently limited access to treatment, questioned the scientific link between HIV and AIDS, and actively supported scientifically unproven remedies as treatment. Notably, this clique of ���AIDS dissidents��� included then president Thabo Mbeki and his serving health minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, among others.

Accordingly, the history of the South African HIV/AIDS epidemic necessitates that we consider how afro-pessimistic perspectives distort our understanding of the state and contemporary politics in Africa. Indeed, normative conceptualizations of the state have often been deployed to characterize African polities and political dynamics as failed, deviant, or associated with criminality, and thus requiring external intervention to redirect these processes. Rather than reproduce colonial depictions of African societies, I contend that reframing the state as people enables a new approach to studying the dynamics of state and society that allows one to circumvent the deployment of normative Anglo-European conceptions of the state.

Following people, whether they are HIV/AIDS activists, members of NGOs, or state representatives, allows us to see their lives as they are actually lived. Moving alongside people involved in HIV/AIDS politics allowed me to witness the development of policy and exercise of power as it happened and use this information to study the state, rather than rely on abstract conceptions of power and politics. Employing this methodology facilitates a different understanding of state power as the amplification of particular people���s ideas and actions, rather than the product of a nameless, faceless bureaucracy.

For example, the development of a provincial HIV/AIDS policy was redirected by the politics surrounding a grant renewal with the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria in the Western Cape province. The actions of particular people and organizations redirected a national policy development process that aimed to rapidly expand HIV/AIDS treatment access. The social process that led to this outcome was the result of actions carried out by people working within, and on the margins of, the state. This history shows how the success or failure of activist-led HIV/AIDS policy initiatives did not depend solely on technical issues, but were instead contingent on the constellation of people, organizations, and institutions that interacted and produced power dynamics and policy outcomes at the different levels of the state.

While the HIV/AIDS movement eventually emerged as triumphant in the struggle over treatment access, for many poor and working-class South Africans, including those involved in the movement, the victory has not addressed the socioeconomic conditions that structure their lives and drive HIV/AIDS infection. Analyzing the significance of the campaign for treatment access alongside limited social transformation, my research suggests that limited social transformation, as seen through social, political, and economic conditions, continues to drive the ongoing expansion of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. This conclusion underscores that rights-based social justice activism and access to treatment may not be sufficient to change the social determinants of health and end the HIV/AIDS epidemic in post-apartheid South Africa.

March 9, 2021

Ghana’s moral panic

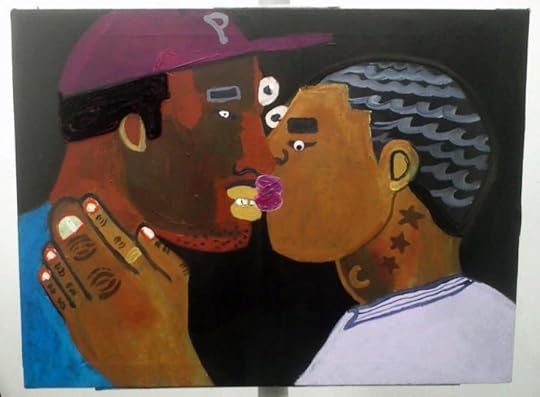

Jonathan Chase, "KISSIS." 2013, acrylic on canvas. Photo credit Trent Kelley on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Jonathan Chase, "KISSIS." 2013, acrylic on canvas. Photo credit Trent Kelley on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. The last few weeks have witnessed intensive homophobic rhetoric across the Ghanaian media landscape in response to news of a fundraising, office inauguration, and rights advocacy event by the Ghanaian LGBTQI+ community in January. The ���dress rehearsal��� for the current situation occurred in 2019, when the National Coalition for Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values (comprising the Christian council, traditional leaders, the Catholic Bishops Conference, Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council, Atta Mills Institute, Coalition of Muslim Organizations, and others) rose against proposals to include Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in the Ghanaian school curriculum arguing that it was an attempt to promote LGBTQI+�� rights in Ghana. The government buckled under the pressure and the proposals were dropped, but the scale of misconceptions peddled at the time and in the ongoing saga demonstrates the sore need for sexuality education and advocacy in Ghana.

Aspects of the commentary are based on the old chestnut that anything other than heterosexual relations and male / female identity is unnatural, seemingly completely oblivious to the abundant evidence of same-sex relations and intersex births from the dawn of history. Others swear to high heaven that LGBTQI+ are against Christianity, Islam, and other religions even as they themselves fornicate, lie, cheat, steal, and commit every sinful act forbidden by their religion. They cite passages such as Leviticus 18:22, but fail to give credible responses when asked whether we should also start stoning to death women who are found not to be virgins on their wedding night (Deuteronomy 22:13-30), or challenge women���s leadership in society, as commanded by 1 Timothy 2:12. There is also the no small matter that in a plural society one���s religious belief is a strictly personal matter and cannot serve as basis for how others should live. Isn���t this what supposedly sets us apart from Boko Haram, for example, whose followers believe that others should adhere to their religious standards or face death?

The fact that January���s LGBTQI+ event was attended by the ambassadors from Australia, the EU, and Denmark, is also presented as sure sign that rich, powerful Western nations are trying to impose LGBT+ ideology on Ghana. Yet, it is prohibitions against same-sex relations that are the Western imports. It was British colonizers who introduced anti-sodomy laws in the then Gold Coast. So, commentary casting same-sex relations as alien or foreign imports sadly reflect an ignorance of colonized history, not to mention traditional���relatively tolerant���attitudes toward difference, such as kwadwo besia (a male with stereotypical female features and behaviors) and obaa barima (a female with stereotypical male features and behaviors). The irony is deeper still because such rhetoric is also aligned with Christianity and Islam, religions that were used by colonizers and slaver traders to delegitimize indigenous Ghanaian worship forms, systems of marriage, family systems, and other culture. Furthermore, evangelical churches, conservative groups and other actors based in the US have spent at least $280 million around the world��to influence policies and public opinion against sexual and reproductive rights. So much for the argument that LGBTQI+ advocates are rather being sponsored by the West.

The current situation is a classic example of a moral panic. The operative word here is irrational, for moral panics are often based on unfounded fears. They are usually created by those with influence or power, such as politicians, religious actors and the media, while those at the receiving end of the attacks can usually be found among relatively powerless and marginalized social groups.

Moral panic involves five key stages, all of which are evident in the ongoing anti-LGBT+ campaigns. First, the LGBTQI+ community is labeled deviant and as more threatening than COVID-19, for simply raising funds and opening a community space to offer protection and support to people vulnerable to rights violations. The second step is a classic case of give a dog a bad name and hang him. The LGBTQI+ community is portrayed in caricatured, exaggerated, and ludicrous ways to entrench fear and falsehoods. Third, these caricatured portrayals feed the incitement and public calls for action against the supposed threat. Stage four is a self-fulfilling prophecy in which those at the helm continue to amplify what they see as the problem and promote ���remedial��� measures. Notably, they beseeched the President to stand against gays, close offices, and criminalize LGBTQI+ advocacy, and target for dismissal those ambassadors supportive of LGBTQI+ rights.

In the fifth stage such pressure tends to result in achievement of the antagonists��� desired goals. On February 24, the police raided and shut down the LGBTQI+ office. This was followed by a declaration against same sex marriage by President Nana Afuko-Addo. Yet, the prohibition of ���unnatural carnal knowledge��� in the constitution notwithstanding, the legality or illegality of same sex relations in Ghana is not settled, as those with a much better grasp of the law have noted.

Today LGBTQI+ Ghanaians who openly declare their status potentially risk family and social ostracization, and even violence. But the march toward LGBTQI+ rights in Ghana is a movement whose time has come. Already, for the first time in the history of LGBTQI+ advocacy in Ghana, the community has received messages of support and solidarity from voices from diverse backgrounds. Such support will only increase as more people understand that one does not have to be gay or lesbian (or be a paid agent as suggested by some commentators) to get involved in LGBTQI+ rights. It is a simple matter of accepting the basic rights tenet that all humans are equal and must be treated with fairness and dignity regardless of their ethnic, religious, sexual, gender, and other identities. Such support is also fundamental to creating a just, open, and tolerant society.

Take the soul from everyone, and the liberty of all

Photo by Francesca Noemi Marconi on Unsplash

Photo by Francesca Noemi Marconi on Unsplash This is written in anger; I could no longer be satisfied with simply admiring the outbursts of bravery of a youth who only have the street to call out their clay-footed rulers. Admiration gave way to regret as I realized that the streets had become the ultimate theatre of expression of the people. This inevitably feeds the political discourses aiming to demonize us, we the young people, to paint us as a homogenous mass with no (political) conscience, to desecrate us and worse, to kill us.

This is an article that applauds the salutary manifesto of 102 Senegalese academics on the crisis of the rule of law in Senegal. It notes with surprise the reaction of Abdou Latif Coulibaly, Secretary General of the government, to which this brilliant text by Hady Ba and Oumar Dia responds. The latter text rightly underlines two important points:

One, no matter the circumstances, an accusation of rape is a serious accusation and must be the subject of an investigation; and

Two, this matter has been politicized from the start not only by the attitude of the accused, but also by the interference of political actors who are close to power and who have surrounded the accuser. The text concluded that in ���instrumentalizing the law for electoral reasons, he (Macky Sall) has placed us in a judicial instability which means that any decision of the justice will be interpreted not as a legal act, but as a political one.���

These debates echoed a webinar that I had a few days earlier, together with fellow academics, on COVID-19, Governance and Human Rights, which warned of this crisis of the rule of law in Senegal. Far from being an exception, as of the last decade or two, Senegal is a democracy only in name.

Therefore, it is important to recontextualize the need to continue to liberate voices, because the danger of the current, dominant discourse is a censorship of future victims of rape or sexual violence. Since the beginning of this case, we have noted unjust treatment of both parties. On one side, Adji Sarr has been dragged through the mud by the press and her life put on display for public consumption, while Ousmane Sonko has been painted as innocent before any legal inquiry. The same Sonko is at the same time facing a judiciary dealing with this rape case with unusual speed and zeal, which has led him to prison for disingenuous motives quite different to those originating from the rape allegation.

This combination of factors lifts the veil on a very Senegalese socio-cultural characteristic and leads the majority to lean toward victimizing the presumed oppressor (Sonko)���himself oppressed by Macky Sall���s regime. Doing so, the blame has shifted to the alleged victim, Adji Sarr, the 20-year-old woman accused of being at the heart of a plot cooked up by those close to the ruling presidential coalition. We will not, therefore, content ourselves with an omission of the facts (in this case, an accusation of rape), which sparked the fire, amplified and fed by frustrations that have been building since 2012.

This is the result of a combination of factors:

One, the perpetual erosion of our legal architecture through the violation of the constitution;

Two, the creation of a Republic of privileges that profits a happy few; and

Three, the repeated flouting of the boundaries between the executive, the judicial, and the parliamentary.

It is important to remember that in any case, Adji Sarr is either a victim of Sonko, or of her employer, Sweet Beaut�� salon (the beauty salon where the opposition leader Ousmane Sonko allegedly raped Sarr), or a guilty party, alone or together with those who hatched this supposed rape conspiracy. In any event, the case is representative of the treatment and the stigmatization of victims of rape and sexual violence, and the culture of rape, in our country���one whose governance remains hopelessly masculine.