Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 139

February 15, 2021

Commerce is cannibalism

Still from Days of Cannibalism.

Still from Days of Cannibalism. Director Teboho Edkins��� cinematic verit��, Days of Cannibalism: Of Pioneer, Cow, and Capital, reminds me of a passage from Karl Marx���s Capital, which reads, ���If money, according to Augier, comes into the world with a congenital blood-stain on one cheek, [then] capital comes dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt.��� In other words, a reminder that the exploits of free-market capitalism remain blood-stained and tethered to an insatiable appetite for land.

A type of grief haunts Lesotho. A legacy of land plundered, labor discarded, and livestock made profane. In Edkins��� latest documentary, footage of cattle chomping the skeletal remains of discarded livestock���a once hallowed creature of Basotho culture, now slaughtered by butchers for sale���offers a foreboding impression of a changing society. In the town of Thaba Tseka, the tenuous promise of economic opportunity for new actors on unfamiliar soil, and their native counterparts in Lesotho, all come into view to provide a fascinating look at the presence of Chinese migrants and their effect on Lesotho’s Basotho people. While Edkins��� oeuvre consists of films that range from documenting gangsters in Cape Town to everyday life in Lesotho, in Days of Cannibalism he returns to Lesotho, a place he lived in his formative years.

The film explores the relationship between settler and native, the daily lives of Chinese migrants alongside footage of Basotho people reckoning with this new settler class of traders. Cannibalism magnifies the social costs of capitalism. For the people of Lesotho and Chinese traders, commerce is cannibalism too. It destroys every living thing, from humanity to the animal ecosystem, and its power of dissolution is infinite. As Edkins puts it, ���If people start actively eating and buying from one another, it is an act of cannibalism.��� The world Edkins sketches out includes both the hardships and small joys of living in Lesotho. For Edkins, the small Southern African country landlocked by South Africa provides an impressive backdrop for a more in-depth exploration of the global economic forces leading Chinese merchants to the continent of Africa.

In the moments Edkins captures, Chinese merchants remain insular and understand the advantages of living in Lesotho. As one Chinese man put it, ���Life is good here. There is nowhere to spend money.��� However, the trade-offs are not one-sided. In one scene, a Chinese shopkeeper talks about his son, who he left behind to be raised by his grandfather in China.

Discussions of Basotho tradition and culture by a charming radio host and scenes of everyday life provide an inlet into the lives of Basotho grappling with social shifts and extreme economic uncertainties. In an early scene of the film, a horse race through the rural landscape draws young and old draped in balaclavas. It offers a fuller picture of life in Thaba Tseka, rather than the struggles of everyday living and poverty that many rural-dwelling Basotho contend with. A memorable scene comes to mind when a group of revelers congratulates the winner of the race by announcing, ���That���s how you ride a horse. The nation���s pride.��� Similarly, footage of Chinese migrants in their compound eating, cooking, and playing mahjong aims to draw back the curtain on the contemporary Chinese experience in Africa by demystifying the daily life of Chinese migrants, struggling to make a living in an unfamiliar place. In contrast, in a meeting hall, a group of Basotho men play cards and drink beer, while another plays the accordion, singing acapella while describing the exploitation by Chinese factory owners. Another shot finds a worker call in to a popular radio station Mojodi FM, to tell of a potential strike because of unfair wages in Chinese factories.

A common theme in the documentary reveals how economic disparities, inequities, and opportunities occur side by side. A standout scene, where two Basotho men arrested for stealing cows, most likely for Chinese buyers, admit in front of a judge that their acts were compelled by wide-spread unemployment, especially in the mining industry in Lesotho. The arrested men are ultimately sentenced to jail time. In response, the presiding judge says, ���We need to give you a sentence that shows the court that this is not a playground. So each of you will be sentenced to ten years in jail. No fine is possible.���

The cow���s transformation as a cultural symbol of significance to a commodity of exchange is the central message of the film. It serves as a reminder that the pedestrian conflicts that rest beneath the surface of daily exchanges between Chinese merchants and the Basotho make for an intriguing watch, but the omission of context and history veil critical vestiges of colonial and military rule, now removed for new risk-taking entrepreneurial settlers of a different time and order. As one person in the film puts it, ���My countrymen, stop christening the nations, this cow will eat and finish them all.���

In Basotho culture, cattle possess a sanctimonious value or character, despite this, herders remain in the background. Too often the director flattened the lives of the Basotho in exchange for scenes of public reproach. This position tended to muffle the agency of the people of Lesotho and reinforce a stereotype of victimhood. A scene with a young Mosotho boy admonished in the street by an elder for riding a horse without documentation, or footage of police lecturing crowds about cattle theft pushes Basotho agency into the background, with the narrative of victim and aggressor at the fore. At the film���s end, the director unexpectedly captures a violent robbery in a Chinese wholesale shop. The filmmaker, shopkeeper and workers fell victim to the act, a scene that vividly evoked the film���s sense of desperation in real time.

The best films help us see the world through someone else���s eye. We identify with their plight, daily struggles, happiness, and hopefully appreciate their life���s journey. Days of Cannibalism, reflects the bleak realities and contradictions of social and economic change in Lesotho and provides a rare and candid look at the impact of new capital in rural Africa.

February 13, 2021

Who is afraid of Robert Sobukwe?

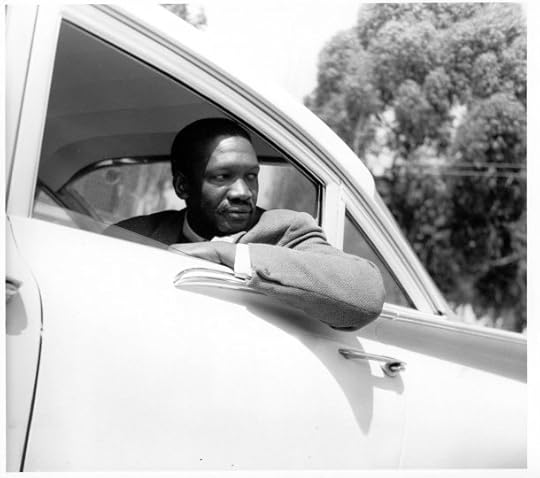

Robert Sobukwe. Image via Twitter.

Robert Sobukwe. Image via Twitter. The 2011 documentary Sobukwe: A Great Soul (dir. Mickey Madoda Dube), features in its opening moments some reflections by the radical American philosopher and activist, Dr. Cornel West. Dr. West recalls a conversation he once had with South Africa���s most iconic political figure, Nelson Mandela (whose release from prison after 27 years in 1990 was recently commemorated). He asks Mandela how come he was widely celebrated (and by extension the liberation movement-turned party he represented, the still-ruling African National Congress), yet the founder of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, was not. For Dr. West, ���There were two great men in apartheid South Africa. The first one was the architect of the apartheid system, Hendrik Verwoerd, and the other great figure was his prisoner, Robert Sobukwe.���

On the 27th of February 1978, Sobukwe died at the age of 53 from lung cancer. At the time he had been languishing in Kimberley for a while, where the apartheid government banished him after being jailed on Robben Island. On Robben Island, Sobukwe was initially sentenced to three years���but Pretoria infamously invented a law with broad powers to maintain his arbitrary detention. Under the ���Sobukwe clause��� of the 1963 General Laws Amendment Act, he was kept in prison for six more years in solitary confinement. Sobukwe���s original ���crime��� provoked one of the apartheid government���s greatest, after the PAC-led, nationwide protest against the Pass Laws on 21 March 1960 resulted in the Sharpeville Massacre. Sobukwe was feared then, and today he is still feared. But by whom, and why?

In a letter comforting Nell Marquard after the passing of her husband, Leo Marquard (a liberal anti-apartheid activist that helped found the National Union of South African Students), Sobukwe concludes by saying: ���The Xhosa have standard words of condolence. They say��Akuhlanga lungehlanga lala ngenxeba (There has not occurred what has not occurred before ��� lie on your wound). God bless you. Affectionately, Robert.��� Reading that, one cannot help but wonder if Sobukwe sensed that what became of his life���its isolation, its decline���would also become of the ideas that outlived him. This week on AIAC Talk, we���d like to help avoid that.

So first, we���re joined first by Derek Hook, a South African-born professor of psychology at Duquesne University, and the editor of a recent collection of over 300 of Sobukwe���s letters (of which the letter cited above is one), called Lie on your wounds: the prison correspondence of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe (Wits University Press, 2019). Given the general disarray of Sobukwe���s body of work (speeches and writings scattered all over the place), we want to investigate if his letters reveal any connection between Sobukwe in private, and Sobukwe in public. Sobukwe is usually stereotyped (by followers and detractors alike) as a hard-nosed Africanist, hostile to any and all whites. But as Hook points out, he is warm rather than cold in the letter to Mrs. Marquard, a white liberal, and Sobukwe addresses a lot of his letters to his life-long friend Benjamin Pogrund, a white man (and his eventual biographer). For a man denied the chance to fully develop his political philosophy, might his personal character serve as a further insight to it?

And then, we turn to Sobukwe���s modern interpreters, those ensuring that his ideas and legacy are not in decline. The generation of students who spearheaded #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall drew from Sobukwe to critique the racialized inequality of post-apartheid South Africa, but also blended it with the Black Consciousness tradition he never lived long enough to engage, and stretched it to contemporary theories like intersectionality. We are then joined by Precious Bikitsha and returning guest Phethani Madzivhandila to explore Sobukwe���s influence today, and what has become of the PAC, the organization he founded (they currently have only one seat in South Africa���s parliament). Precious is a history graduate student at the University of Cape Town, researching the writings and contributions of black women to South Africa���s political history, and Phethani is pan-Africanist historian, activist and AIAC contributor.

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 CAT, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week���s AIAC Talk was on telling stories about Africa. We spoke to Dana Ballout and Adam Sj��berg about The Messenger, a new podcast they produce about the Ugandan musician-turned politician Bobi Wine; and then we spoke to Aim��e Bessire and Erin Hyde Nolan about Todd Webb in Africa, a book they put together which collects the photographs taken in Africa by the renowned American photographer Todd Webb.

Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

February 12, 2021

The music of the Nyayo era

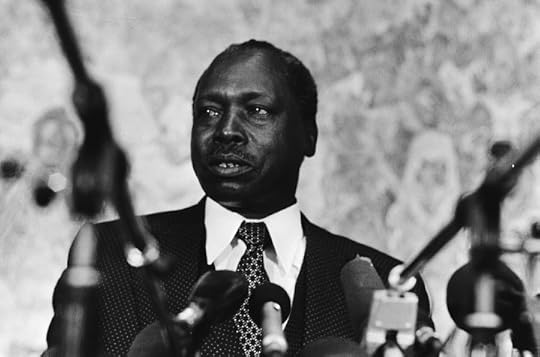

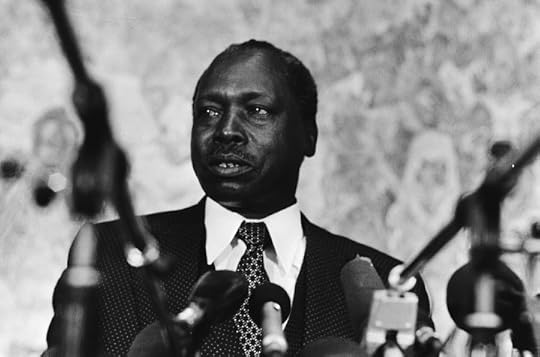

Image credit Rob Croes (Anefo) via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit Rob Croes (Anefo) via Wikimedia Commons. Wangui Kimari has temporarily stepped away from curating our series of reposts from Kenyan publication The Elephant, so various members of our editorial team will take turns curating selections every week until she’s back. Always on the look out for the intersection between music and politics, managing editor Boima Tucker noticed a post from last week marking the first anniversary of the death, and contextualizing the rule, of former Kenyan president Daniel Torotich Arap Moi. So, in the spirit of our Friday tradition of providing you with a Weekend Music Break, we reconstructed it in the form of a YouTube playlist. Listen below.

Last week marked the first anniversary since the death of the second president of Kenya, Daniel Torotich Arap Moi. Indeed, much has been written and said about Daniel Arap Moi, and his death uncorked a litany of previously hidden details and insights into the Shakespearian drama he presided over while in office. But how do we evaluate the legacy of Moi���s agency during his time in office? Is it through the memoirs that will and have been written, the popular slogans that were created by his regime and sang by his supporters, or is it the ���official��� narrative peddled by the state? Or is it, perhaps, the pain his detractors and critics faced or the scars of the victims who suffered his heavy hand? Popular music reflects the culture of our day. Through it, we can observe the blueprint of an age in the lyrics and sound of that time. Perhaps, we argue, that if we listen to the popular music of Moi���s 24 year rule we can observe the fingerprint and maybe get a glimpse of the Man and his legacy.

The following is a chronological account of the sounds and hits that defined the 24 year rule of Daniel Torotich Arap Moi. Hit play on the playlist above to listen along.

1978: Jomo Kenyatta died on August 27, 1978 and President Moi subsequently took over as the second president of Kenya. Kenya is just getting over Daudi Kabaka���s hit “African Twist,” so we must start with his song “Msichana wa Elimu” with lyrics that give advice about marriage. Daudi Kabaka was born in 1939 and died in 2001. He was a popular Kenyan vocalist, known to his fans as the undisputed “King of Twist.”

1979: Nico Mbarga has taken over Africa with Sweet Mother. Locally Slim Ali and The Hodi Boys Band are all the rave, playing in hotel lounges and clubs across the Middle East and North Africa and ended up in Kenya. Slim Ali is from Mombasa. Here, President Moi is still loved and respected by many people. He enjoys popular support from the people. A pull-out from The Nation describes him as a humble and accessible president.

1980: Fadhili Williams re-releases “Malaika.” The song was first recorded by a Tanzanian musician Adam Salim in 1945. Fadhili was born in Taita Taveta in 1938 and died in 2001.

1981: Maroon Commandos and Habel Kifoto produce “Charonyi Ni Wasi.”

1982: The August 1st coup, a failed attempt to overthrow President Daniel Arap Moi���s government, so musicians are under pressure to release unity and praise songs. The biggest hit comes from Them Mushrooms in the form of “Jambo Bwana,” which was featured in Cheetah, a Disney film that had the phrase Hakuna Matata which became very popular when Disney released The Lion King later.

1983: Safari Sounds Band releases That���s Certified Gold. Among the biggest hits was ���Mama lea mtoto wangu.���

1984: Moi has banned Congolese music. But he changes his mind after the release of Mbilia Bel’s “Nakei Na��robi.“

1985: By now the Nairobi live scene has suffered because of the effects of the 1982 coup and Moi���s informal censorship. The dark days of the Nyayo era are at a crescendo. Detention without trial of many political prisoners and others flee the country at risk of facing the heavy hand of the regime. Still, a rebirth happens in the music scene led by Sal Davis and The Establishment. The music isn���t politically conscious, however.

1986: The many detentions of the Nyayo era has also killed the vernacular live scene. State operatives at the time saw these spaces as points of political mobilization, but Joseph Kamaru leads a little uprising popularizing Kikuyu vernacular hits.

1987: D.O Misiani and Orch come to the scene. And Shirati Band releases some seditious tracks among them ���Safari Ya Musoma.���

1988: Mombasa Roots Band arrived on the scene with “Disco Chakacha“���originally released in 1986.

1989: Ten years after it was founded Muungano Choir finally created a pop smash hit ���Safari Ya Bamba.��� The following year they released Missa Luba recorded in Germany after the Berlin wall came down, ending the Cold War era and the triumph of liberal democracy.

1990: Les Wanyika released an earthshaking album. One of the biggest hits was ���Sina Makosa.���

1991: Albert Gacheru makes his way through Kikuyu Pop music. His biggest hit was “Mariru.”

1992: JB Maina releases “Mwanake,” and Japheth Kassanga, Mary Wambui, Helen Akoth, and Mary Atieno are redefining gospel music with the Joy Bringers and Sing and Shine TV shows. But Freshley Mwamburi’s “Stella Wangu” is the hit of the time.

1993: Diversification happens in Kenya���s music industry. Many acts like Sheila Tett, Musically Speaking���later Zanaziki and a boy band called 5 Alive change the music scene. Among the many tracks released by Zanaziki is a popular hit. Also, Okatch Biggy and not to forget Princess Julie who create the soundtrack to the Moi government’s response to HIV in Kenya “Dunia Mbaya.”

Mid-90s: Urban music is now bigger than was ever expected. Another boy band Swahili Nation makes their way into the music scene. The opening up of Kenya���s democratic space after the repeal of section 2a in 1991, the import of American culture, and growth of local media outlets drastically shifted Kenya���s music scene. Two more examples from this era include The Pressman Band from Mombasa and Zannaziki.

Ted Josiah brings out a guy called Hardstone who is loved by the growing young urban population.

Jimmi Gathu and others organize for a musician called Eric Wainaina to do the first version of a new national anthem dubbed ���Kenya Only.���

Shadez O Black are challenging Hardstone for the artist of the year award with the smash hit ���Serengeti Groove.���

Still in the mid 90s, there���s a cultural earthquake that changed the music scene in Kenya. Kalamashaka���s hit “Tafsiri Hii.��� A culmination of poor governance by the Nyayo era, the structural adjustment programs of the 80s and 90s and new young urban generation raised by a staple of America���s hip hop culture and Nairobi���s budding urban culture produces a socially and politically conscious movement of artists who go by the moniker Ukoo Fulani.

Eric Wainaina later drops “Nchi ya Kitu kidogo.” The song that Moi���s government truly hated.

2000s: The music scene expands dramatically and is ungovernable. A growing sign that the years of Moi were coming to an end and that he could not hold on any longer to power. Ogopa Deejays arrive in the music scene, and the biggest song of those first two years, the soundtrack to the exit of Moi, all the way from Okok Primary school, is Gidigidi Majimaji’s “Unbwogable.” This song was used as a slogan by the coalition government that removed Moi from power.

Weekend Music Break: The music of the Nyayo era

Image credit Rob Croes (Anefo) via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit Rob Croes (Anefo) via Wikimedia Commons. Wangui Kimari has temporarily stepped away from curating our series of reposts from Kenyan publication The Elephant, so various members of our editorial team will take turns curating selections every week until she’s back. Always on the look out for the intersection between music and politics, managing editor Boima Tucker noticed a post from last week marking the first anniversary of the death, and contextualizing the rule, of former Kenyan president Daniel Torotich Arap Moi. So, in the spirit of our Friday tradition of providing you with a Weekend Music Break, we reconstructed it in the form of a YouTube playlist. Listen below.

Last week marked the first anniversary since the death of the second president of Kenya, Daniel Torotich Arap Moi. Indeed, much has been written and said about Daniel Arap Moi, and his death uncorked a litany of previously hidden details and insights into the Shakespearian drama he presided over while in office. But how do we evaluate the legacy of Moi���s agency during his time in office? Is it through the memoirs that will and have been written, the popular slogans that were created by his regime and sang by his supporters, or is it the ���official��� narrative peddled by the state? Or is it, perhaps, the pain his detractors and critics faced or the scars of the victims who suffered his heavy hand? Popular music reflects the culture of our day. Through it, we can observe the blueprint of an age in the lyrics and sound of that time. Perhaps, we argue, that if we listen to the popular music of Moi���s 24 year rule we can observe the fingerprint and maybe get a glimpse of the Man and his legacy.

The following is a chronological account of the sounds and hits that defined the 24 year rule of Daniel Torotich Arap Moi. Hit play on the playlist above to listen along.

1978: Jomo Kenyatta died on August 27, 1978 and President Moi subsequently took over as the second president of Kenya. Kenya is just getting over Daudi Kabaka���s hit “African Twist,” so we must start with his song “Msichana wa Elimu” with lyrics that give advice about marriage. Daudi Kabaka was born in 1939 and died in 2001. He was a popular Kenyan vocalist, known to his fans as the undisputed “King of Twist.”

1979: Nico Mbarga has taken over Africa with Sweet Mother. Locally Slim Ali and The Hodi Boys Band are all the rave, playing in hotel lounges and clubs across the Middle East and North Africa and ended up in Kenya. Slim Ali is from Mombasa. Here, President Moi is still loved and respected by many people. He enjoys popular support from the people. A pull-out from The Nation describes him as a humble and accessible president.

1980: Fadhili Williams re-releases “Malaika.” The song was first recorded by a Tanzanian musician Adam Salim in 1945. Fadhili was born in Taita Taveta in 1938 and died in 2001.

1981: Maroon Commandos and Habel Kifoto produce “Charonyi Ni Wasi.”

1982: The August 1st coup, a failed attempt to overthrow President Daniel Arap Moi���s government, so musicians are under pressure to release unity and praise songs. The biggest hit comes from Them Mushrooms in the form of “Jambo Bwana,” which was featured in Cheetah, a Disney film that had the phrase Hakuna Matata which became very popular when Disney released The Lion King later.

1983: Safari Sounds Band releases That���s Certified Gold. Among the biggest hits was ���Mama lea mtoto wangu.���

1984: Moi has banned Congolese music. But he changes his mind after the release of Mbilia Bel’s “Nakei Na��robi.“

1985: By now the Nairobi live scene has suffered because of the effects of the 1982 coup and Moi���s informal censorship. The dark days of the Nyayo era are at a crescendo. Detention without trial of many political prisoners and others flee the country at risk of facing the heavy hand of the regime. Still, a rebirth happens in the music scene led by Sal Davis and The Establishment. The music isn���t politically conscious, however.

1986: The many detentions of the Nyayo era has also killed the vernacular live scene. State operatives at the time saw these spaces as points of political mobilization, but Joseph Kamaru leads a little uprising popularizing Kikuyu vernacular hits.

1987: D.O Misiani and Orch come to the scene. And Shirati Band releases some seditious tracks among them ���Safari Ya Musoma.���

1988: Mombasa Roots Band arrived on the scene with “Disco Chakacha“���originally released in 1986.

1989: Ten years after it was founded Muungano Choir finally created a pop smash hit ���Safari Ya Bamba.��� The following year they released Missa Luba recorded in Germany after the Berlin wall came down, ending the Cold War era and the triumph of liberal democracy.

1990: Les Wanyika released an earthshaking album. One of the biggest hits was ���Sina Makosa.���

1991: Albert Gacheru makes his way through Kikuyu Pop music. His biggest hit was “Mariru.”

1992: JB Maina releases “Mwanake,” and Japheth Kassanga, Mary Wambui, Helen Akoth, and Mary Atieno are redefining gospel music with the Joy Bringers and Sing and Shine TV shows. But Freshley Mwamburi’s “Stella Wangu” is the hit of the time.

1993: Diversification happens in Kenya���s music industry. Many acts like Sheila Tett, Musically Speaking���later Zanaziki and a boy band called 5 Alive change the music scene. Among the many tracks released by Zanaziki is a popular hit. Also, Okatch Biggy and not to forget Princess Julie who create the soundtrack to the Moi government’s response to HIV in Kenya “Dunia Mbaya.”

Mid-90s: Urban music is now bigger than was ever expected. Another boy band Swahili Nation makes their way into the music scene. The opening up of Kenya���s democratic space after the repeal of section 2a in 1991, the import of American culture, and growth of local media outlets drastically shifted Kenya���s music scene. Two more examples from this era include The Pressman Band from Mombasa and Zannaziki.

Ted Josiah brings out a guy called Hardstone who is loved by the growing young urban population.

Jimmi Gathu and others organize for a musician called Eric Wainaina to do the first version of a new national anthem dubbed ���Kenya Only.���

Shadez O Black are challenging Hardstone for the artist of the year award with the smash hit ���Serengeti Groove.���

Still in the mid 90s, there���s a cultural earthquake that changed the music scene in Kenya. Kalamashaka���s hit “Tafsiri Hii.��� A culmination of poor governance by the Nyayo era, the structural adjustment programs of the 80s and 90s and new young urban generation raised by a staple of America���s hip hop culture and Nairobi���s budding urban culture produces a socially and politically conscious movement of artists who go by the moniker Ukoo Fulani.

Eric Wainaina later drops “Nchi ya Kitu kidogo.” The song that Moi���s government truly hated.

2000s: The music scene expands dramatically and is ungovernable. A growing sign that the years of Moi were coming to an end and that he could not hold on any longer to power. Ogopa Deejays arrive in the music scene, and the biggest song of those first two years, the soundtrack to the exit of Moi, all the way from Okok Primary school, is Gidigidi Majimaji’s “Unbwogable.” This song was used as a slogan by the coalition government that removed Moi from power.

February 11, 2021

Thousands of mockingbirds

Image credit Elsadig Mohamed.

Image credit Elsadig Mohamed. This post forms part of the work by our 2020-2021 class of AIAC Fellows.

In the lobby of Al-Moa’lm Hospital in Khartoum, I looked at the corpses and injured bodies around me. Outside the heavy glass doors that we locked, I saw the four-wheel drive vehicles of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) carrying heavily armed soldiers and heard the sound of bullets. Clouds of smoke rose above the burning tents, casting a shadow over our weeks of dreaming of commune and carnival, in the hopes of achieving a nonviolent revolution.

I realized how tenuous life can be, and what it took for me to remain alive; to be able to write these lines: the death of other comrades and protesters who prevented the attackers from storming the hospital and killing dozens, if not hundreds, more. On the morning of Monday, June 3, 2019, when the Transitional Military Council (TMC) ruling Sudan carried out the Khartoum massacre, dozens including myself narrowly found shelter inside the hospital. Outside, more than 150 people were killed, dozens were thrown into the Nile, and both men and women were raped. Many are still missing today.

The sit-in had begun on April 6 at the army headquarters, about 16 weeks after the start of the popular revolution against the Islamic regime led by Lieutenant General Omar al-Bashir. On April 11, under pressure from the sit-in and the intervention of senior officers, Bashir stepped down. After Al-Bashir stepped down, the so-called Transitional Military Council was formed from a group of senior officers of the former regime, headed by the former deputy minister and defense minister. But he resigned after one day due to the continuing protests that saw in him a continuation of the old regime, and demanded a full civilian government to govern the country until democratic elections could be held.

From the dispersal of the Khartoum sit-in, June 3, 2019. Credit Elsadig Mohamed.

From the dispersal of the Khartoum sit-in, June 3, 2019. Credit Elsadig Mohamed.On the night of June 2nd, I entered the encampment at 10 pm accompanied by friends. We headed to our usual spot near the University of Khartoum Clinic. Despite forewarning signs that the TMC was getting ready to disperse the sit-in, the carnival atmosphere of freedom and comradeship joy prevented me, like many others from anticipating the horror to follow. Near dawn, I headed to the last barricade on Nile Street, where I found the youths huddling around a fire and singing, with dozens of military vehicles just meters away. Returning to the camp, I reassured my friends that an attack was impossible. Less than an hour later we heard gunfire and witnessed the chaos of people trying to escape. A mixed armed force poured from the north toward the sit-in. Although witnesses confirmed that the first to reach the sit-in were wearing the blue police uniform, official investigations are still ongoing regarding the identity of the groups that carried out the attack. The police deny their involvement.

While the forceful dispersal was taking place, the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), one of the main groups involved in organizing the sit-in, appealed to the Sudanese army to “fulfill their duty and defend the citizens from the TMC’s militia.” But the soldiers guarding the military headquarters refused to let fleeing people take shelter in the compound. My friend and I attempted to reach his car, but we could only get as far as the public hospital where the injured were arriving. As we sheltered in the hospital, what we witnessed from its windows for the next ten hours became a nightmare.

Outside, army vehicles rolled around, threatening to shell the building. Inside, rescue operations proceeded. The corpses were isolated in one room, urgent cases triaged in another space, while the reception was filled with the wounded whom the hospital staff tried to treat assisted by the revolutionaries���among whom were doctors and nurses. The television hanging on the wall was broadcasting the massacre of our comrades. My phone rang; it was my sister asking in panic about my whereabouts. I informed her of our situation and asked after the safety of others. I sent a message to my wife in Cairo to reassure her, and switched off my phone to preserve the remaining charge. Then I lay on the floor and slept.

By the day���s end, the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), a broad political and trade union umbrella, would declare a general strike and civil disobedience, as well as terminate negotiations with the regime. In the coalition���s view, the massacre was planned in advance and executed by the regime, which it now labeled the ���Coup Council.��� It designated ���combined forces within the Sudanese military, the Janjaweed militias (also known as the RSF), the national security forces and other militias” as responsible for the massacre, as well as for interventions in other cities including En Nahud, Atbara, and Port Sudan. Meanwhile the head of the TMC issued his own statement, also cutting off talks. He announced a nine-month timeline, to end with elections under “regional and international supervision.”

I don’t know how long I slept, but I headed down to the ground floor after I awoke. The place was still crowded with the wounded; some of the injured were outside in the hospital yard. The sound of bullets had somewhat subsided, but the smoke was still rising. Aggressors had destroyed the campsite. Shortly after, when we dared venture outside the hospital, we stood in the street looking toward our wasted land. The scene was reminiscent of images of villages burnt down in Darfur years earlier. There had been a revolutionary slogan: “Oh, you arrogant racist, we are all Darfur!” Now the slogan was actualized.

While standing outside, I saw a 10-year-old boy, and asked about his friends. He told me that they were safe, then and added, “They have betrayed us.��� His statement stuck in my head. The politicians and military had never intended to protect us or the political community flourishing in the sit-in. The revolutionaries did not lack political foresight: attempts to disperse the congregation had occurred since the beginning of the sit-in. Yet this was a betrayal of our faith, of the euphoria the camp represented. We didn’t think anyone could kill a mockingbird.

In September 2019, the Prime Minister of the transitional government, Abdalla Hamdok, ordered an investigation into the massacre, establishing a committee with a three-month deadline, renewable once, to publish its findings. Yet today, some 17 months later, no findings have been issued. Varying reports have estimated the death toll between 100 and 150, while medical reports indicate 70 documented cases of rape of both men and women. But in November 2020, another government committee announced the discovery of a mass grave in Khartoum, which forensic sources linked to the massacre. It contained some 800 bodies.

From the dispersal of the Khartoum sit-in, June 3, 2019. Credit Elsadig Mohamed.

From the dispersal of the Khartoum sit-in, June 3, 2019. Credit Elsadig Mohamed.What did we lose in the massacre? Not only hundreds of lives, but also an idea of Sudan as a commons. Since the revolution began in December 2018, questions of territory and boundaries had followed, including around the sit-in in the weeks prior to the massacre. Where did the sit-in territory start? Where did the protection of protesters end? Did a limit denote restricting revolutionary activities within it? Were all activities outside these boundaries therefore illegal and vulnerable to attacks by law enforcement?

Within its boundaries, the sit-in redrew the mental map of Sudan. It expressed an idea of Sudan that until then had only existed in ideology and hopeful fantasy. All of Sudan was present, and not just in territorial terms, despite the tents bearing signs of ethnic and geographic groups, but also in a fluid and carnival sense that challenged the underlying cartographic fiction, like a map of Sudan drawn by a child.

It was this childish revolutionary map���with its representations, expressions, and potential���that triggered fear and anxiety in the old regime and made clear the impotence of the traditional parties that were supposed to lead change. The negotiations over boundaries of the sit-in area, drawn by a joint security committee including both the military regime and the FFC coalition, had represented, symbolically, negotiations over the destiny of the country itself.

When revolutionaries extended the area of their barricades for security reasons, after a first dispersal attempt on May 13, only to be forced to retreat back to the original lines following an internal conflict within the SPA, it signaled a surrender of entire areas from the recognized ���occupied��� geography. And when one of these areas to the immediate north of the encampment, a poor neighborhood known as Colombia burdened with negative racial and class stereotypes, including tales of alcohol and drug-use prevalence, became the excuse for military intervention, it amounted to a sacrifice of the neighborhood by the moderate protestors on the altar of bourgeois morality. Indeed, the different parties���the TMC, the moderates in the FFC, and the radicals in the FFC���had different maps in mind that translated into different visions of Sudanese society. So far, it is the progressive current that has lost out.

From the dispersal of the Khartoum sit-in, June 3, 2019. Credit Elsadig Mohamed.

From the dispersal of the Khartoum sit-in, June 3, 2019. Credit Elsadig Mohamed.On the morning after the violent dispersal of the sit-in, while I was still at the hospital, I heard about bloody events that had spread to many cities, and the occupation by the RSF of the streets of the capital. Their humiliation of Khartoum residents would continue for more than a week.

Movement had resumed in front of the hospital gate, with a number of people gathering outside. Army personnel, accompanied by a few civilians, had parked in front of the entrance. Their presence, we learned later, was to negotiate safe exit for civilians trapped in the hospital. My friend’s car had been completely destroyed, peppered with bullet holes and the interior vandalized. The soldiers negotiating our safe passage stopped me from joining the evacuating group on account of my dreadlocks, which might provoke the RSF because of an assumed resemblance to Darfuri militants, so I was ordered to go back inside the hospital. I later heard stories of people targeted for this exact reason.

Exhaustion lodged in my body and soul. It is an exhaustion that continues today: we have different reactions to dealing with the trauma of a near-death experience, of knowing dead bodies are held in a closed room next to us, of the fear your body will be mutilated or harmed. Many of those who were there that day are receiving therapy for PTSD. My sister-in-law, who witnessed the massacre first hand, wrote this to me recently:

The Khartoum massacre was one of the most difficult moments in my life, to be surrounded by all this death, destruction, and harm is more than anyone could possibly bear. A moment that I do not like to remember but cannot forget. After the massacre, I returned to Egypt to begin a treatment journey of psychotherapy. The psychiatrist diagnosed me with post-traumatic stress disorder. Her opinion was that I should be admitted to a psychiatric hospital for two weeks to be monitored and treated for the visual and auditory hallucinations accompanied with hysterical breakdowns, anxiety, and constant insomnia. I turned down the admission but I am still taking medication.

The sit-in was the necessary distance to be traveled between the revolution and the state. It was a euphoric space where the old ended, and the new could be built. Its dispersal represented a break in this process, or perhaps fed it with new ideas. It certainly clarified contradictions in the political alliance for change that carry lessons not only for understanding history, but also in planning the future.

The wounds on our bodies represent another kind of map: they tell a story of who was there, and who survived.

Sankara is not dead

Still from Sankara Is Not Dead.

Still from Sankara Is Not Dead. Burkina Faso���s single railway line originates in Abidjan, Cote d���Ivoire on the Atlantic coast and runs northward 600 kilometers to the capital and largest city, Ouagadougou. The railway was established by the French colonial administration and its route remained unchanged until Thomas Sankara came to power in Upper Volta in 1983 through a military coup. In 1985 his government began work on extending the rail line northward. Included in this effort was what become known as the ���Battle of the railways.��� Citizen-workers from villages along the planned route competed in squads to clear the roadbed and lay 100 kilometers of track to connect Ouagadougou with the town of Kaya. The initiative was Sankara���s vision of development by and for the people.

Sankara���s ultimate goal for the railway line was to continue it farther north to Tambao, on Burkina Faso���s border with Niger, where the region���s largest Manganese deposit remained largely inaccessible by road and, therefore, unexploited. The revolution to transform Burkina Faso into a truly independent, self-determined nation cohered socially and politically required capital, and Sankara envisioned manganese as part of the means to that end. The people���s inspired work on the railway line ceased on October 15, 1987, the day Sankara was assassinated and his government was ousted in a coup orchestrated by Blaise Compaor��.

The 2019 film Sankara n���est pas mort (Sankara Is Not Dead), part of this year���s New York African Film Festival, tells a story situated in the euphoria of the 2014 People���s Revolution in Burkina Faso that ended Blaise Compaor�����s 27-year grip on the country. Writer and director Lucie Viver���s film is a beautifully shot and expressively scored portrait of Burkina Faso and its people in this moment of uncertain yet hopeful change. It integrates poetry and travel writing, with splices of Sankara���s speeches and footage of the 2014 revolution to capture people���s experiences in the aftermath of the uprising.

Bikontine, the film���s protagonist and narrator, has concluded his preparations to leave the country for Europe, when he is swept up in the mass demonstrations against Compaor�� and the subsequent celebrations for the end of his regime. Still restless but resigned to remain in the country, at least for the moment, Bikontine embarks on a journey of discovery through his native Burkina Faso���the Land of the Upright Men���from south to north by railway, that would end at the stretch of track abandoned in the wake of Sankara���s murder, short of its destination in Kaya.

At the heart of the film are conversations between Bikontine and the people he encounters in the city, towns, and rural villages along the tracks of his journey north. During his brief moments engaged with them, he immerses himself in their work. These seemingly ordinary people are revealed to be extraordinary through their conversations with Bikontine and the stories they tell of themselves and their lives in the country.

What adds to the film���s richness is its revelatory take on Sankara���s memory and legacy without centering him in the narrative. His speeches and quotes are woven into scenes as backdrops that shape the mode of the film. Still, Sankara���s immense meaning for the country and its people grow increasingly evident to viewers and to Bikontine as his journey progresses.

The film���s subtext is the evident failure of Compaor�����s mission to erase Sankara from public memory. Through what he called the ���rectification period,��� Compaor�� reversed Sankara���s economic initiatives and innovations in the country. He dismantled Sankara���s mobilization schemes to build schools and health clinics, and Sankara���s visionary project to make Burkina Faso reliant on its own resources for its development. Burkina Faso was reduced, once again, to Western dependency. To further strip the country of Sankara���s influences Compaor�� jailed, tortured and forced into exile those who had been loyal to Sankara.

Yet, as the film���s title declares and its story evinces, Sankara is not dead. He helped inspire the people toward the 2014 revolution that brought down Compaor�����s regime and the 2015 mass demonstrations that ensured a democratic transition. These are les enfants de Sankara. They reflect a wave of anti-authoritarianism in the Global South. Through art, popular culture, and a revived interest in Sankara���s speeches and writings, Sankara has emerged as both a lesson on the uncertainties of revolutionary change and the possibilities for people-centered development for the present and future.

February 10, 2021

More than a freedom fighter

Rose Chibambo.

Rose Chibambo. Rose Lomathinda Chibambo (September 8, 1928���January 12, 2016) was a prominent politician and well-known figure in Malawi���s fight for independence from colonial rule. After many years as a successful political and public figure, Chibambo was forced into exile only a year after Malawi gained its independence, after falling out with the newly elected leader of Malawi, Dr. Hasting Kamuzu Banda. Both she and her husband were forced to flee Malawi, without their children, to neighboring Zambia in 1965. Chibambo returned 30 years later in 1995, a year after Malawi transitioned to multiparty democracy from one-party rule. Her husband died in 1968, and she thus returned alone, leading a quiet life mostly out of the public eye until her death in 2016.

In 2019, a book chronicling the life of Chibambo was published. Titled Lomathinda: Rose Chibambo Speaks, and authored as a book-length interview by Dr. Timwa Lipenga, it was originally to include several prominent female voices, with several academics in addition to Lipenga being signed to the project. However, after project funding was suspended, Lipenga continued working on the book alone, deciding to focus on the story of Rose Chibambo. The result is Rose Chibambo���s story in Rose Chimambo���s words. A beautiful and critical historical document that also resides squarely within the realm of literature, Lomathinda lifts the veil of post-colonial romanticism from Rose Chibambo���s story, transforming her into more than a freedom fighter on a banknote (she is currently the featured portrait on the 200 Kwacha note).

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity.

Michelle ChikaondaTell me a bit about yourself: who you are, your academic history, and how long you have been in your particular role, which later anchored your writing of this book.

Timwa LipengaI am a lecturer at Chancellor College. I majored in English and French literature at university, and I���ve always loved books. Before becoming a lecturer, I was a journalist with The Nation (one of Malawi���s major newspapers.). Then I moved on to Chancellor College, where I teach mainly in the French Department.

Michelle ChikaondaWhere did the initial idea for the book come from?

Timwa LipengaSeveral Malawian academics, all men currently in the Malawian diaspora, approached me and a couple of my women colleagues at Chancellor College to say that they would like to hear more about Malawian voices, especially voices from Malawian women. They felt women would be better placed to research those voices and to speak to people.

So, we were given a list of people to interview and were told to add to the list. We were told that they would find funding for the project if we identified women who we wanted to interview, but finding that funding proved to be difficult, and the project was eventually suspended.

But by the time it was suspended, I had already fallen in love with one of the subjects, from the little that I could dig up on her: Rose Chibambo. And I said, Okay, even if there���s no funding, I���m going ahead with this, because I want to know more about her. And that���s how it started. I read a bit on her, and then I asked people if they knew where I could find her. Once I got in touch with her, I discovered she was also eager to tell her story. So, I would say it worked out perfectly for me in that way.

Michelle ChikaondaWhy did you decide to structure this text as an interview, rather than a biography?

Timwa LipengaWhen the suggestion was made to us���this suggestion to go out and interview the women we had identified���we decided to read around the project, read around what happens in a biography. So, there I was, reading and coming up against debates on whose voice comes through in a biography: whose story is it, really? That really shaped how I did things, because I remember reading one particular book where they said some people write someone���s story, but it���s their own voice in the end. So, I said, Okay, how do I make it her voice? I���ll still have to speak in there, but I want it to be hers. And that’s why I decided to opt for the interview structure.

Michelle ChikaondaYou speak so many languages. What language did you conduct the interviews in, and why? It is written in English, but that of course doesn’t necessarily mean that the interviews were conducted in English.

Timwa LipengaFrom the word go, it was in English. Because when I called her and introduced myself, it just happened that I opened the conversation in English. So, we started speaking in English before we���d even met in person. Then, when I first went to her home, I asked her what language she would be most comfortable in, and again, she said she would be comfortable in English.

I didn���t ask her why, but I think I can figure out why. She came from a community where mostly Tumbuka and Ngoni were being spoken, whereas my own mother is half-Yao, half-Nyanja, and I���ve grown up speaking Chichewa. So, I think there would have otherwise been a conflict of languages! We struck a happy medium with English.

Michelle ChikaondaHow long did it take? Was it a single interview? Or was it structured interviews over time? And what editorial decisions did you make in deciding what to include?

Timwa LipengaIt was a series of interviews over time. I would call her and say, I am coming this weekend, and would spend both Saturday and Sunday, speaking with her. Then some months would pass, and I would call again and ask to go over again. As all this was happening, I was still doing outside reading about her, and would sometimes call her and ask what she thought about something in the book I���d read. Sometimes she would confirm what was said, and sometimes she would tell me that wasn���t what had actually happened.

Regarding editorial decisions: there were times when she said, ���I don’t want these names in the book.��� So, when I submitted the first draft to the publisher, I replaced those names with “X.” My publishers made a different decision. They replaced the X���s with pseudonyms. That was something that was done on the editorial side.

Michelle ChikaondaThere���s a lot of really fleshed out detail in the period up to the point she goes into exile in Zambia. But I noticed that she doesn���t go into nearly as much detail about her time in exile. What are your thoughts on that? Did you get the sense that there was stuff that she just didn’t want to talk about, or that she may have been protecting?

Timwa LipengaI think there were definitely things she didn���t want to talk about. I think it was a painful period, because of her husband���s death in 1968, the way it happened in particular [that she was not permitted to return with his body to Malawi to bury him]. Her son tried to come and visit them, and he was arrested for that. She did not see her children again until her return in 1995. So, I think there was a lot of trauma in that time; the whole story is traumatic, but there was a particular kind of trauma tied up in the period in Zambia. And I think that���s why she didn���t really want to talk about it that much.

Michelle ChikaondaWas the book being published now a deliberate decision? Have you been concerned at all about what it is publish a book that contains critique of Kamuzu Banda now, at the same time that Banda���s party, the MCP [Malawi Congress Party], has returned to power���as part of Tonse Alliance���for the first time in 26 years?

Timwa LipengaNo, it wasn���t deliberate. The book would have come out earlier if not for how long it took to find the right publisher. And back then, we didn’t even know that MCP would be back in power. The book actually came out when the previous government was still in power.

My response to anyone concerned about political critique in the book is this: you will see that she���s not just criticizing the MCP. She���s looking at the country as a whole; she���s looking at what came afterwards, what they had expected versus what actually happened. Yes, the MCP is criticized, but so are the other parties, and so are the other events that took place. She was simply talking about Malawi as a whole.

There were things about Malawi she now found disappointing. She returned and found people weren���t the same people she remembered from the 1960s, who would protest like they did back then. Now they were people who seemed resigned.

There must have been hope, certainly, and the joy of returning home, but there was also the sense of ���What did I come home to?��� She talked about finally returning, and about the stares she was getting as she was coming in through immigration; the feeling of being regarded with suspicion. But then she also talked about the warm welcome in the family now that she was back, about the joy of seeing her mother and children again, especially. For Chibambo, there was ultimately the determination to rebuild. She literally rebuilt her house, and the rebuilding was what was most important to her.

Michelle ChikaondaRose Chibambo had to fight so hard to be seen, and her womanhood was often used against her. How you have been thinking about this in light of everything going on right now with the activism around gender-based violence in Malawi? How do you place this narrative inside this larger discussion of giving women their fair stage in a society that continues to marginalize them?

Timwa LipengaI got to learn from one of my colleagues about the whole Herstory movement; how it gave voices to women, and how history at some point focused on women in order to let them tell their story. If you look elsewhere, the idea of Herstory is decades old���but in Malawi we haven’t done it. We���re still in the process of recovering women’s voices. And that is important, and you can never recover them enough.

If we then connect it to the gender-based violence���especially the days of activism���when you hear some of those stories you wonder, are these really happening in this decade? Are they really happening now? Happening during a time when women get university educations and get good jobs? Are there still women who think in a certain way? Or is there still a certain kind of violence that���s perpetrated against women, regardless of where they find themselves?

Only two months ago, I met a woman who talked about having been forced into marriage: how she was actually dragged from home and so on. To her, it was just something that had happened; that���s the life she was living, and she had accepted it. But I said to myself��� how many women are going through this, now? How many women today are forced by their families to leave school and get married? You���d have thought by now we would be more evolved. So, we do need all these voices telling women���s stories.

Michelle ChikaondaTalking about voices and literature, where do you see this book situating itself in the landscape of Malawian literature, or history, or���to a certain extent���politics?

Timwa LipengaI think it has a place in history. But, interestingly, I���ve had students coming from the Department of English to say they���d like to do their dissertation on the literary devices in the book. So, maybe it���s somewhere in between! Some people will see it as literature, in the sense of African literature; others will see it as history. But the ones who have organized panels at Chancellor College were from the Department of English. So maybe there is more of an interest in the literature.

Michelle ChikaondaDid Rose Chibambo ever talk to you about why she was willing to speak now, and willing to speak to you in particular? It’s clear that she had this desire to tell her story, and was so thrilled for you to help her tell it. But did you get a sense that maybe there had been a time when wouldn’t have?

Timwa LipengaI think she always wanted to tell her story. It���s just that no one had thought of asking! I know that people would interview her when they wanted to talk about the cabinet crisis in Malawi���way before I came in���and she would tell them her story, solely in connection to the cabinet crisis. But I think no one had come and said, ���Tell me about you.��� She wanted to talk about Malawi; she really wanted to talk about her experiences. She wanted them to count for something.

Way before we even had a publisher, in fact, she would talk about it as ���our book.��� So, she believed, even before the manuscript was accepted for publication that there would be a book. Even when I told her I hadn���t found a publisher yet, she would talk about that. When she died before I even found a publisher, that was hard. She would have loved to see this. She really wanted to tell her story.

Michelle ChikaondaIt feels like you���ve started a larger conversation with this book. What other stories do we need to go out and look for? What other voices are out there, that we need to get down before they pass on?

Timwa LipengaWhen it comes to voices: some of the stories I attempted to get were rather disappointing. I would go out and approach someone, and the response would be ���Just send me a questionnaire!��� They wanted no interaction. So, there were women out there who were suspicious, who just thought this person was trying to dig into their private life, and would just clam up. But with Rose Chibambo I was fortunate. She didn’t ask to see the questions beforehand. We would just talk.

Recovering women���s voices remains important. Telling a woman���s story is important. Because behind that silence a lot is happening, and we need to keep speaking out. Even if we look at our society, there are more women than men and yet most of the decision makers are men. And because of that, sometimes, some of them don���t understand when you say certain things, for example around violence. So any voice that can speak out on anything that concerns society is important.

Michelle ChikaondaWhat did it feel like, when the project was done?

Timwa LipengaAn emptying, if that makes sense! There was a point at the end, when I was going through it again and again, asking myself if I had represented her faithfully. And then of course you bring it to your editors, and there���s a process of negotiation around what they want and don���t want in the book, which was its own struggle.

For example���at first, my title was ���Lomathinda: Journeys and Interruptions.��� But my editors said, ���No, that’s too dense: you’re thinking like an academic. I really loved ���Journeys and Interruptions,��� but I had to give in. So, we found common ground with Lomathinda: Rose Chibambo Speaks.

One thing that I was always insistent on, however, was the idea of the last word. At the beginning of the project, I had said, I want her to have the last word. But at the end there was a chapter that my editors kept insisting needed to be rearranged, I think they had some kind of commentary they wanted to include, but I insisted that she have the last word.

Michelle ChikaondaWhat is the next project? Are you working on anything now, or are you taking a breather? I imagine this project may have opened up other doors with respect to the future direction of your own work.

Timwa LipengaI am trying to do something academic. I���m reading more on biographies, and what happens if I write a biography, then someone else writes a biography of the same person, and so on over the years? What is it that they are looking for? What do they stay faithful to? I���m actually working on a project where I want to compare four authors who wrote a particular biography on a particular person; I want to see what they kept and what they left out, and why. And I���m trying to specialize in that area.

Michelle ChikaondaWe���ve talked generally about voice, and about Rose Chibambo, and those particular chapters that were interesting, but there are things that I missed, or things you’d want me to understand more?

Timwa LipengaMaybe the most poignant parts of the interviewing process. There was a moment we shared when she was talking about the courtship between her and her husband. When she was telling it, she burst out laughing, and I started laughing too. That was quite a moment; I loved that moment.

I also loved the fact that there was no self-pity, where she was involved. She would talk about her suffering, talk about the good times, but it wasn���t ���poor me, poor me.��� She just told her story. And as a listener, I just encouraged her to speak.

They usually say when you���re writing a biography, you shouldn���t get too close to your subject, because that means you forget how to be objective. And I will confess that was difficult for me���really difficult. Because I just thought she was such a great person!

I definitely had a great experience, yes. Maybe because I do literature, but I had the profound sense of someone passing down a narrative to a different generation. Maybe I just put a romantic spin to it, but it was truly an unforgettable experience.

The global and class inequalities of fossil fuel subsidy reform

Image credit Sosialistisk Ungdom (SU) via Flickr CC.

Image credit Sosialistisk Ungdom (SU) via Flickr CC. Since the G20 meeting in 2009, a range of international organizations have used climate change arguments to press for fossil fuel subsidy reform. A widely read International Monetary Fund (IMF)-study from the same year estimates that the global cost of fossil subsidies in 2017 was about $5.2 trillion, and that cutting these would reduce global carbon emissions by 28%. These amounts include direct subsidies to production and consumption, as well as external costs such as health and environment.

Now, the World Bank, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the International Energy Agency (IEA) want to use COVID-19 as an opportunity to get rid of what it considers inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. The G20 did not achieve much before 2020, only reducing fossil fuel subsidies by 9%. Most of this reduction resulted not from active policies, but from lower costs of the subsidies, due to reduced international petroleum prices.

However, in responding to COVID-19, the G20 is moving in the wrong direction with new subsidies in the form of equity injections, loans, tax exemptions, and the relaxing of environmental standards. G20 countries spent about $170 billion in ���public money commitments to fossil fuel-intensive sectors between January 1 and August 12, 2020.��� In the US, COVID-19 packages to fossil fuel companies cost the public at least $50 million, in addition to the $20 billion annual subsidies. In Norway, a member of the non-G20 country group ���Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform,��� the oil industry got tax postponements worth more than $10 billion.

Through bilateral relations and international institutions, the same governments���mainly in the global North���continue to push for consumer fuel subsidy reforms in the global South. In response, fuel riots against price increases have taken place in 41 countries between 2005 and 2018, including Trinidad and Tobago, Nigeria, Egypt, Nepal, Sudan, Ghana, Cameroon, and Zimbabwe. As the IMF and allied institutions insist that fuel subsidies primarily benefit the middle classes, protests appear not only an obstacle to climate mitigation, but paradoxical and contrary to their own interests.

In Nigeria, there has been regular and successful popular resistance against the removal of subsidies since the mid-1980s, most famously in 1993, when then president General Ibrahim Babangida annulled election results, and almost two decades later, with the Occupy Nigeria 2012 protests. With the combined oil and COVID-19-crisis, pump prices rose again in 2020. In September, the Nigerian Labor Congress (NLC) suspended their announced subsidy strike, marking a historical turn in labor action, both in accepting deregulation and by disengaging with social unionism. Other civil society actors reacted with disappointment and anger, and many protesters included the demand for lower fuel prices in the #EndSARS protests, framed mainly against police violence. Now, the pump price has increased again, the NLC is threatening strike action, and the government may reintroduce the subsidy.

In Sudan, the first attempt to remove subsidies was in 1999 under the government of Omar al-Bashir. The Sudanese Workers��� Trade Union Federation (SWTUF), usually loyal to Bashir, opposed the attempt, but it was not until 2013 that the SWTUF threatened to strike over subsidy reform. Again in 2018 al-Bashir attempted to remove bread and fuel subsidies, which triggered the Sudan revolution. With the independent Sudan Professional Association in the driver���s seat, al-Bashir was forced to step down in April 2019. Today, the ruling alliance under the Forces of Freedom and Change is under pressure over subsidies. The Sudanese Communist Party (SCP) recently announced its withdrawal from the coalition, referring to the government���s plans to remove subsidies.

I talked to trade unionists from the NLC, SWTUF, Ghana Trade Union Congress and Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions to understand why labor opposes the removal of subsidies. While acknowledging climate change, the unionists from all four countries insisted, contrary to the neoliberalist narrative, that fuel subsidy removals are anti-poor and anti-worker. All referred to attempts to remove subsidies as linked to austerity policies, such as Structural Adjustment Programs, dating back to the 1980s.

Increased fuel prices have immediate and inflationary effects and thus impact poor people disproportionately. In 2012 in Nigeria, when President Goodluck Jonathan removed the subsidy overnight, the pump price increased by 141%, and costs of transport, food, and medicine went up immediately. Minimum wages lost their purchasing power. In Sudan and Ghana, unionists explain that loss of fuel subsidies also negatively impact agricultural production.

Africans are particularly vulnerable to climate change, while the continent���s contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions is minimal. In fact, according to the IEA, the COVID-19 crisis is reversing progress on energy access in Africa. For the poor, alternative energy sources, such as using wood instead of kerosene for cooking, can even be worse for public health and the environment. When international institutions argue that the savings from subsidy cuts would be better spent on more pro-poor targeted policies, unions respond that they do not trust the governments to do so. Before subsidy reform, they argue, basic social welfare policy and infrastructure should be in place. Furthermore, in their countries, reform is not aimed at mitigating climate change through budget reallocation, but for budget savings. Recently in Nigeria, the minister of petroleum said there was a choice between low fuel prices (and subsidies) and workers getting paid at all. A Ghanaian unionist presented a simpler solution to the fiscal constraints: Tax the rich.

Climate activists and leftists should tread cautiously when they use the climate argument to support the fossil fuel subsidy reform agenda in Africa. As Sean Sweeny has warned, neoliberal policies and approaches to energy transition ���will produce outcomes that are��considerably worse than the outcomes produced by fossil fuel subsidies.���

February 9, 2021

A thousand portraits of a loyal man

Still from film Marighella (2020).

Still from film Marighella (2020). With the support and incentive of the US government, a wave of military coups swept South America in the 1960s. Brazil was no exception. In 1963, then American president John F. Kennedy made the aim clear: to ���prevent Brazil from becoming another Cuba.��� Although Brazilian president at the time, Jo��o Goulart, was a leftist with an eager eye for structural reforms, he was a critic of both the Cuban and US governments. Nevertheless, in 1964 the US navy stationed a fleet of warships on the Brazilian coast and on April 1 a 20-year era of military state-sanctioned terror began in the country.

Marighella, the film directed by Wagner Moura, tells the story of Carlos Marighella���the most important figure in the resistance against that state terror in Brazil and an inspirational icon for revolutionaries worldwide. Born in Salvador, Bahia, in 1911, to the free daughter of an enslaved Sudanese woman and an Italian immigrant father, Marighella became a Brazilian Communist Party (PCB) militant at the age of 23. Jailed twice during the first dictatorship of Get��lio Vargas (1930 to 1945), Marighella was elected to Congress in 1945, and served there until the Cold War era, when the PCB was banned. After visiting China in the 1950s, at the invitation of the Chinese Communist Party, and as political tensions in Latin America hardened following the Cuban Revolution, Marighella began to doubt and disagree with the PCB executive over the timing and degree of revolutionary actions. When the 1964 military coup occurred and the PCB didn���t have a practical response to it, Marighella left the party. In 1967 he participated in the Latin American Solidarity Organization Conference in Cuba and returned to Brazil that same year to establish the A����o Libertadora Nacional (ALN). Under the political influence of Marxism-Leninism and inspired by Che Guevara���s foquismo, the ALN soon became the most influential armed organization in the resistance. Consequently, Marighella was declared ���public enemy number one��� by the state.

After dropping off the radar and out of the mainstream political discourse for two decades, Marighella���s name has resurfaced in public debate in the past ten years. Just as the era of dictatorships and its admirers, including current Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, have become a sinister specter for the left, so has Marighella���s name for the right. Even before its release, Marighella acquired a story of its own.

Director Wagner Moura is a vocal critic of Bolsanaro. The President, who has often publicly praised the Brazilian dictatorship and its agents of terror, has accused the film���s director and producers of praising a ���bloodthirsty terrorist���, while using the bureaucracy of the national cinema agency to delay the film���s release, originally scheduled for late 2019. A new release date in May 2020 was further delayed by the onset of the global pandemic.

The film director, Wagner Moura, has publicly voiced his opposition to Bolsonaro and that is the impression that I got from before and after watching Marighella: it is a response to Bolsonaro���s election, his praises of the dictatorship and his attacks on Marighella, as much as it is a gift to the liberal left who has lost hegemony to Bolsonaro, and because of its own sins.

As Frantz Fanon wrote in The Wretched Of The Earth, ���colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.��� Of course the Algerian liberation struggle, which Fanon was analyzing when he wrote these words, is far different from the situation the Brazilian anti-dictatorship struggle found itself in during the military regime. But I am concerned with violence. I am concerned with how violence is used and how the people are subjected to its simplicity. To what Jean-Paul Sartre mistakenly concluded from Fanon���s writings, that they were ���an endorsement of violence itself,��� Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak responded:

Fanon insists that the tragedy is that the very poor is reduced to violence, because ������ there is no other response possible to an absolute absence of response and an absolute ������ exercise of legitimized violence from the colonizers. […] many of us think that the ������ real disaster in colonialism lies in destroying the minds of the colonized and forcing ������ them to accept mere violence���allowing no practice of freedom, so that these minds ������ cannot build when apparent decolonization has been achieved���. When it comes to the ������ people on its very receiving end, violence can only be either observed or absorbed.

The Brazilian left, on the other hand, has tended to transform resistance violence into a political taboo, and has even put itself in official opposition to those who have found liberation or revolution through any means necessary. Yet, curiously, it attempts to romanticize a few historical revolutionaries, such as Marighella and Che Guevara, while shying away from contextualizing the means these same figures resorted to. After all, violence is at the core of Carlos Marighella���s political tragedy. He was a highly intelligent man and knew that the laws of liberal democracy could not be the drivers of political action, because those same laws are what reduce the people to violence. Yet, in the film, the most violent acts of resistance are delegated to a specific fictional character, who seems almost erratic and ���too radical��� to be reasonable. Recall Erik Killmonger, the character in Black Panther, who evoked a similar feeling: the more revolutionary, the less reasonable. Since the 1980s, Brazil has been on edge with post-dictatorship fright���as if we are always walking on eggshells, as if we should give the greatest of values to liberal democracy because of the ghost of the dictatorship���making it hard to surpass the contradictions of bourgeois democracy.

For 21 years in Brazil the order of the day was that if you were an artist, a student, a journalist, if you were politically engaged on any level, or simply by virtue of being Black or Native, you risked being jailed without trial, tortured, and killed. The film fails to depict that daily reality. It fails to expose the extent of the state-sanctioned terrorism. If it was not for the brief explanatory text contextualizing the era at the beginning of the film, one could easily mistake it for standard bad cops / good robbers cinema. One wonders if Marighella and his group would have been ignored by the state if they had not robbed banks and trains.

���Down with the fascist military dictatorship! Long live democracy! Long live the Communist Party!��� yelled Marighella just before being shot in the chest inside a cinema theater and surviving, in one of the most iconic moments of his story. On screen, Marighella is limited to just ���Long live democracy!��� Indeed, the film shies away from radical language (in it, Marighella only uses the word ���communism��� twice and only in dialogue with the head of the Brazilian Communist Party and avoids describing himself as Marxist-Leninist, as the real life Marighella proudly did). Marighella, the film is more aligned with a liberal left that shies away from the radical in defense of bourgeois democracy. It was with that mentality that a leftist government invaded Haiti and passed anti-terrorism laws in Brazil to criminalize ���violent protests.��� I wish I could say it is a less widespread mentality, but it is not. Words like ���communism��� and ���anti-fascism��� have caused political disruption since Bolsonaro���s election. In parallel to that, the film also tries to take a stance against his government. Like outgoing President Donald Trump, Brazil���s current leader and his supporters favor criminalizing communist and anti-fascist organizations and so the liberal left has been trying to dodge radical mobilizations to attract neoliberals and moderate conservatives into a ���pro-democracy��� block against Bolsonaro.

This mirrors a tendency of the right in Brazil, which historically, to some degree, has dictated the rules of the game to the left. With the beginning of the military dictatorship there was a surge of right-wing paramilitary groups (just as with Mussolini���s Blackshirts militia in Italy) and they were responsible for many terrorist attacks. Attributing the attacks to the left served as an excuse for the state to intensify its authoritarian abuses, such as the infamous AI-5 (Institutional Act Number 5), that shut down Congress, abolished political and legal rights, the Constitution itself, and institutionalized torture. When democracy was on the horizon, in the 1980s, and general elections were becoming inevitable, the military dictators in power were concerned that the country could go into the hands of the radical left. They searched for someone on the left who could play a controlled part in the democratic elections, who would not present credible threats to liberal democracy, but would undermine the then presidential candidate, Leonel Brizola, a more leftist candidate who had just returned from political exile. They found the personification of that ���controllable left��� in Luiz In��cio ���Lula��� da Silva, who endures as the face of the left in Brazil. During its 13 years in power, with fragile policies and political office nominations, that ���Lulism��� managed to hijack most of the biggest social movements, civil organizations, and labor unions that could now have the potential to put up a fearful fight. Instead, however to this day we still blindly follow those guidelines set by the right.

Mano Brown���a member of the greatest hip hop group to come out of Brazil, Racionais MC���s���was first cast to play Carlos Marighella in the film, but due to scheduling conflicts could not pursue the role. Seu Jorge, a famous Brazilian singer, was cast instead. Carlos Marighella was a light-skinned Black man, closer in looks to Mano Brown than the darker-skinned Seu Jorge. The choice in casting became a controversy in itself, with some Black activists accusing the filmmakers of colorism, and the left as a whole saying it would be impossible to picture Jorge as Marighella, while the right simply denied Marighella���s Blackness altogether. In the lyrics of their 2012 song, Mil Faces de Um Homem Legal (A Thousand Portraits of a Loyal Man) dedicated to Carlos Marighella, Racionais call him ���the mulatto superhero.��� ���Mulatto��� is not a race. But Marighella did not know that precisely because he was not dark skinned. He called himself a mulatto because the unconscious distancing from Blackness by light-skinned Blacks is part of the Brazilian white supremacy project. This is not to say that Marighella was ignorant about race in Brazil, but he did not possess Black Consciousness in the deeper sense, as conceptualized by Steve Biko and others. Hence, the choice of actor to play him onscreen can also be seen in a political context. Ironically, Brown would inadvertently invoke the spirit of the more radical Marighella, when in the 2018 election campaign he was invited to speak at a rally for Brazil���s Workers Party (Lula���s home). There, Brown, who has been an inspiration for generations of Black people (including the one writing this piece), accused the left of forgetting the people when they were in power and that the threat of a Bolsonaro government was the price they were paying for it. So, the ���former��� Marighella indirectly accused the left of being unfaithful to the real Marighella. Brown did not get it right, though. The liberal left has the Brazilian (working-class, poor and black) people exactly where it always wanted them to be: blackmailed by the nightmare of the dictatorship ghost, and deluded by the Workers Party ���Brazilian Dream.���