Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 142

January 26, 2021

The weaponization of memory in Burundi

Rice farm in Burundi. Image credit International Rice Research Institute via Flickr CC.

Rice farm in Burundi. Image credit International Rice Research Institute via Flickr CC. Sometimes called ���Burundi���s Lumumba,��� Prince Louis Rwagasore (1932���1961)���better known as Ludoviko or Rudoviko Rwagasore in his home country���has been one of the few political figures in modern Burundian history to be remembered fondly across ethnic and social lines. Rwagasore became Burundi���s first elected prime minister in 1961. Historian Christine Deslaurier asks, ���How could such a distant prince, comparable to a Tutsi ��� resist ��� the political and military ethnicization, the multiparty system, and the emergence of a public space? How can Rwagasore still be magnified by the Burundians, a priori unanimously, when other heroes of African independence suffer the horrors of memory erosion or historical depreciation?���

African independence leaders such as Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, and Am��lcar Cabral have been immortalized internationally in fictionalized and documentary films, stylized visages and icons, theater and literature, and art works across virtually all media. Rwagasore���in spite of popularity in his home country and his international connections to Julius Nyerere, Patrice Lumumba, and Gamal Abdel Nasser���has received only a fraction of such artistic appropriation, and his memory and legacy have been manufactured, utilized, lionized, and weaponized in equal measure through modern Burundi���s tumultuous political history.

Former Ugandan Ambassador to Burundi Edgar Tabaro writes:

Prince Rwagasore was a towering figure and certainly belonged to the league of Patrice Lumumba, Kwame Nkurumah [sic] and the like. Born of privilege (he was crown prince), he opted instead to champion the cause of the masses. He was a leftist and pursued policies of egalitarianism in a country that had deep-rooted class (some writers wrongly call the classes ethnic groups) system with the Tutsi pastoralists at the top, Hutu cultivators at the bottom and the hunter gatherers, the Twa, largely living on the margins of life.

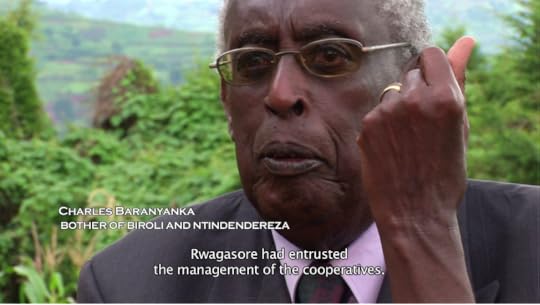

Burundian diplomat Charles Baranyanka explains how Rwagasore���s entrustment of cooperative management to white Belgians eventually led to the destruction of the cooperatives.

Burundian diplomat Charles Baranyanka explains how Rwagasore���s entrustment of cooperative management to white Belgians eventually led to the destruction of the cooperatives.Indeed, class conflicts between the Tutsi (historically the ruling minority) and the Hutu (the historical and present majority) have run through much of Burundi���s post-independence history, including civil wars in the 1970s and 1990s and the assassinations of several heads of state. Rwagasore���s party, the Union pour le Progr��s National (UPRONA), formed in alliance with Hutu leader Paul Mirerekano, sought to mend class-ethnic conflict from the onset, and Rwagasore���s marriage to Marie-Rose Ntamikevyo, a Hutu, ostracized him from the royalty while reinforcing his commitment to the abolition of ethnic division.

His demotic approach to political coalition-building, his advocacy for Burundian self-sufficiency and worker co-operatives, and his increasingly forceful calls for independence prompted Belgian colonial authorities to issue a decree in 1960 prohibiting royalty from running for political office. Rwagasore was placed under house arrest for six weeks and UPRONA consequently lost the 1960 elections, but the intervention of the United Nations in 1961 to oversee new elections saw him elected as prime minister on September 18, 1961. Less than a month later, on October 13, Rwagasore was shot dead in Usumbura (now known as Bujumbura). Though the assassin was Greek national Jean Kageorgis, accompanied by Burundian members of the pro-Belgian Parti D��mocratique Chr��tien, Kageorgis himself accused Belgian colonial authorities of the murder a day before his own execution, and later historians and journalists such as Ludo de Witte and Guy Poppe drew upon recently unsealed archives to point to evidence of a Belgian conspiracy as well. (Burundi officially accused Belgium of the murder in 2018.) Rwagasore���s two daughters died under mysterious circumstances months after his assassination, and his wife died of poisoning in 1973. Since the death of Rwagasore, his memory and legacy as an anticolonial revolutionary has been co-opted and utilized by dominant political parties for the manufacturing of unity to ensure hegemonic control. Christine Deslaurier writes ���his death was put at the service of a hegemonic UPRONA project that was very different from the one he had promoted during his lifetime. In his name, this party was able to claim a monopoly of power dominated by Tutsi elites who sabotaged his open and unitary vision of monarchical government, paving the way for an exclusive one-party regime.���

Banknotes with Rwagasore���s portrait were printed and diffused to the most rural corners of the country, October 13 was made a national holiday, and a mausoleum overlooking Bujumbura was financed by stamps bearing his visage. When Jean-Baptiste Bagaza���also from UPRONA���seized power in the 1976 coup d�����tat, his eleven-year presidency was marked by a distancing from Rwagasore: the October 13 holiday was abolished and the Jeunesse R��volutionnaire Rwagasore were replaced by the Union de la Jeunesse R��volutionnaire du Burundi. This flipped again after the 1987 coup d�����tat, in which UPRONA Major Pierre Buyoya became president from 1987-1993 and revitalized Rwagasore���s memory with the Institut Rwagasore and a call for renewed national unity.

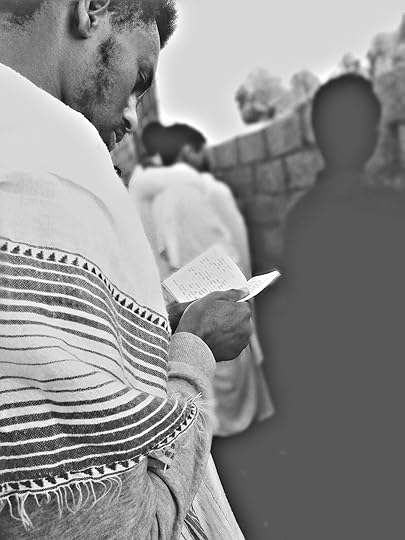

The politically dissident Burundian reggae band Lion Story, living largely in exile since 2014, performing an homage to Rwagasore at the Bujumbura bar Vouvouzella in 2013.

The politically dissident Burundian reggae band Lion Story, living largely in exile since 2014, performing an homage to Rwagasore at the Bujumbura bar Vouvouzella in 2013.So strong was the new UPRONA���s monopoly on Rwagasore���s memory that when the Front pour la D��mocratie au Burundi (FRODEBU) came to power in 1993 after the country���s first multi-party presidential elections, Burundi���s first Hutu president, the progressive Melchior Ndadaye, did not attend the 1993 commemorations and instead sought to distance himself and his party from the UPRONA-ized Rwagasore cult. Ndadaye was assassinated by Tutsi soldiers three months after taking office, sparking the bloody Burundian Civil War (1993���2005). The war ended with the Arusha Accords mediated by Julius Nyerere, which saw the cementing of Rwagasore���s anticolonial legacy as the Accords invoked his name specifically, praising his ���charismatic leadership��� that eschewed ethnic conflict for peace and unity.

When the Arusha Accords clause prohibiting more than two consecutive presidential terms was broken by the controversial third presidential campaign of Pierre Nkurunziza in 2015, major unrest ensued following violent clashes between the military and anti-government protestors: some 1,700 civilians were killed, and hundreds of thousands more fled Burundi, creating a massive refugee crisis which is only now beginning to see repatriation. Although Nkurunziza went on to serve a third term, he forwent a fourth term run and ceded power to his party���s 2020 election candidate, incumbent president ��variste Ndayishimiye. In spite of the state-sanctioned commemorations of Rwagasore every year, the far-right Hutu supremacist ideology of the Conseil National Pour la D��fense de la D��mocratie ��� Forces pour la D��fense de la D��mocratie (CNDD���FDD), Burundi���s ruling party since 2005, shows that the commemorations are largely lip service no different from the pre-Civil War Rwagasore idolatry: lofty political rhetoric masquerading ongoing ethnic conflicts and tensions. Burundian writer David Gakunzi���s aptly titled ���The ideological manipulation of Rwagasore’s legacy is unprecedented in Burundi��� notes that ���the objective of this ritualization of the figure of the prince [is]���to confer a certain legitimacy on the established powers,��� drawing a parallel to Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko���s caricatural lionization of Lumumba while murdering student protestors in Lubumbashi.

Nevertheless, the end of the civil war in 2005 and the inclusion of the Rwagasore in the Arusha Accords (which later served as the basis for the country���s constitution, promulgated on March 18, 2005) marked an end to the vacillation between cult-like adulation and repression of Rwagasore���s public memory in the more than three decades following Burundian independence, paving the way for artistic renderings of his legacy transcending the politicization and weaponization of years past.

Rwagasore: Vie, Combat, Espoir (2012), directed by French-German filmmaker and sound designer Pascal Capitolin and Burundian journalist and filmmaker Justine Bitagoye, was the first feature film to examine Rwagasore���s life and legacy. The film follows Burundian writer and journalist Roland Rugero who goes on a journey of historical discovery through archives and places as we learn about Rwagasore through historical footage and transcripts as well as interviews with his family, contemporaries, and historians. Capitolin stated ���this film has been made as an answer of the request of having a film in Burundi that tells about Burundian history in a country that does not treat history since there���s no way of consensual understanding on history. Rwagasore is the only figure of the past where it has been possible to share history without too high dissent.��� The film���s appraisal of Rwagasore���s rise to the independence struggle, his economic innovations in teaching farmers (alongside Paul Mirerekano) to form co-ops and grow crops to compete with the dominating Greek and Arab expatriate businessmen in Ruanda-Burundi, his short-lived term as prime minister, his assassination, and his legacy does a great service in de-obfuscating the highly politicized panegyrics echoed by the Burundian political establishment.

Screencap of the bust in progress: Ngendakumana and Pili sculpting a bust of Rwagasore.

Screencap of the bust in progress: Ngendakumana and Pili sculpting a bust of Rwagasore.Singer-songwriters Jean Pierre Ngendanzi, Bernice the Bell, and Evode Ntahonankwa as well as the reggae band Lion Story have written and performed music as homages to Rwagasore, with lyrics such as ���Ntiwashize imbere kuramba, washize imbere ukurama kw���u Burundi, mumwidegemvyo amahoro n���iterambere��� (You [Rwagasore] chose Burundian stability, freedom, peace, and progress over your own life) and ���Le prince Ludovico s���est sacrifi�� pour le Burundi, luttant pour le bon avenir des enfants du Burundi, et les r��gimes qui lui succ��d��rent la plupart se r��v��l��rent despotiques��� (Prince Ludovico sacrificed himself for Burundi, fighting for the good future of Burundi’s children, and the regimes that succeeded him, most of them proved despotic), showing a turn away from superficial hagiography to a broader reckoning of Rwagasore���s efforts in context with the history that followed his death. The sculptors Sylvestre Ngendakumana and Juma Pili are shown in Rwagasore: Vie, Combat, Espoir working on a bust of Rwagasore resembling the busts found in Bujumbura today, many of which were made in the decade following his death. More and more art forms are representing, appropriating, and rendering Rwagasore, expanding his image beyond Burundi and adding nuance to the highly politicized rendering of his image in the decades following his death.

Deslaurier writes:

In the end, it was the martyrological dimensions of its anti-colonialism that installed a consensus around [Rwagasore���s] mythical figure, more than his highly articulated political and social thought ��� The political myth is born in the crisis of society. … Ultimately, therefore, it is perhaps when the prince is no longer summoned by contemporary leaders solely for his unitary qualities that we can say that Burundi will be reconciled with itself.

And perhaps while the political class of Burundi has yet to achieve this reckoning, the artist community already has.

A Black woman in Bali

Photo by Artem Beliaikin on Unsplash

Photo by Artem Beliaikin on Unsplash ���The��thing��you always suspected about yourself the minute you became a��tourist��is true,��� Antiguan writer Jamaica Kincaid declares in A Small Place, ���a tourist is an ugly human being.��� She may have been writing about Bali, Indonesia.

A young Black woman from the US, Kristen Gray, moved to Bali amid a deadly pandemic ravaging Indonesia. She posted a Twitter thread���her account is now disabled���extolling the virtues of migrating to Southeast Asia. Her wide-eyed assertions are not uncommon to anyone from the region who has seen it marketed to Westerners and the globally mobile. She boasted of her ���elevated��� and ���luxury��� lifestyle in Bali, where the cost of living is big value for her dollars but less for anyone earning Rupiah. She found solace in Bali���s safety and the Black in Bali community.

Gray has since been deported.

Leaving the US in her 20s was ���a game changer,��� a common refrain of Black Americans who find more peaceful, less traumatic existences elsewhere, even in booming East Asia, where the fear of being gunned down by police officers is non-existent, the daily state of rage that drains one���s soul in Western societies arises far less frequently, and opportunities are abundant. With her girlfriend, they booked ���one way flights to Bali.���

Reactions from all corners of Twitter were strong and swift. Her advertised actions revived animus and unleashed restrained thoughts, a feature of our age, that went far beyond a toxic social media platform���s daily roast.

Some called her out for allegedly violating immigration laws, not having proper work and tax permits, entering the country during a pandemic, and encouraging others to do the same via Indonesian visa agents. Some Indonesians, along with my circles in Southeast Asia, were stunned at the dragging. The sixth-most unequal country in the world, Indonesia suffers many indignities, but it, and The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), are also not helpless children. While the West has devoured itself over the last three decades, Southeast Asia has quietly transformed its economies at an enviable pace. The lingering Cold War Western idea of our corner of the world as a cheap, malarial mega dump, a ���third world shit hole,��� was always trite and now ever more at odds with reality.

Some rushed to her defense, citing anti-Blackness in the accusations. They noted the number of white Westerners who regularly ignore a raging pandemic and continue their travels, let alone the sheer number who have migrated, both legally and illegally, to Southeast Asia with no backlash.

Europeans and Americans traveled widely during winter with the pandemic at its deadliest peak. Tens of thousands sauntered into Dubai and the Maldives. Londoners fleeing Tier 5 lockdowns were among the crowds. Their vacations or new homes were not splashed on Twitter, but visually friendly Tik Tok and Instagram were swollen with egregious displays of carelessness and entitlement. Almost 70,000 Israelis ditched their national lockdown to party in the Emirates. If the argument is exploitation, there are few destinations where cheap labor is screwed over more than Dubai or the Maldives. ���White people get Eat/Pray/Love if they travel,��� Sri Lankan writer Indi Samarajiva tweeted, ���the Global South gets Beat/Detain/Hate.��� Gray is not of the South, but you get his point.

Some on the left had little sympathy. No one raised in the US, they argued, is immune from internalizing the pathologies of imperial thought, of seeing inequity as a natural order to be exploited at every turn. The ill-fated proselytizing mission of John Chau, an Asian-American killed trying to convert the isolated Sentinelese people of India���s Andaman Islands, underscores this theory. The world is also without doubt different for a Black traveler carrying a ���white��� passport, the type that swats borders away like an unwelcome odor, than one carrying an African passport, which confers a lifetime of mistreatment.

But it is also imperial to impose one���s understanding of the world, notions of history, and moral code onto a society and people half a world away. Many became Indonesian experts overnight. ���A triple minority in the US,��� read one tweet, ���but you���re a colonizer in Bali.���

Some tweets read like US State Department press releases. Gentrification was the word of the hour. Such assertions bemuse because they are pulled from the bowels of an Atlantic-centric worldview���or worse, Brooklyn-centrism���which has scant understanding of East Asia and would struggle to name a single Southeast Asian thinker or writer. The vast span of islands, an infinitely complex bundle of nations masquerading as a young country of 270 million called the Republic of Indonesia, where languages change between cities an hour apart, must, like all countries, be understood on its own terms. Bali is not in any way West Papua.

Some would be wise to sit this one out, namely expats in Southeast Asia. One editor living in Vietnam tweeted that his ���main question��� was her use of African-American vernacular: ���what does ���stack bread��� mean?��� he asked, claiming curiosity. An Australian Twitter personality lectured her followers on how ���minorities can still be oppressors.���

Their, um, anxieties speak to a larger changing dynamic in travel, particularly in Southeast Asia. Never mind that many in the Western club entered the region using similar tactics. It���s their reminder that global mobility and the opportunity to settle overseas is built for them, and them alone. They are today the East Asian Raj, a select group of successful, morally charged Westerners who stand on a high pedestal in their welcoming Asian homes, barking at their subjects about everything from human rights to corruption to apparently who ���oppressors��� can be. The loud Raj, drunk off the cheap wine of Western exceptionalism, is, of course, a feature of life in more than the former colony. The Raj is Southeast Asia���s nouveau settlers, not Gray.

This comes from a loss of exclusivity. In my childhood, the beaches of Thailand and the Philippines were entirely the domain of white Western tourists. White folks were so visible in Southeast Asia that, as a child, I believed them to be the largest population of people. Today, they are the minority of travelers. Russians, for instance, were the only non-Asians in the top 10 visitors to Thailand in 2019. Times have changed. Money and power lie elsewhere.

When some East African economies developed a healthy middle class, they flocked to Thailand and the malls and bars welcomed Kenyans and Ethiopians. Prior to the pandemic, the African neighborhood in Bangkok was more bustling than ever. Ethiopian restaurants opened in numbers, with one named Fidel. More Black Americans stroll my neighborhood than ever before. But districts with Black faces, not British and Australian pubs, are also the perennial target of immigration raids.

Ultimately, at the very core of an incoherent discourse, is still a total lack of reckoning with the most powerful currency in our world. A one-way flight is available to such a tiny minority of nationalities, it immediately triggers outrage. Not a single Indonesian citizen could dream of booking a one-way flight to become a digital nomad in Australia, North America, or the EU. Right-wing politicians and news media in the West would have a field day if one Indonesian even tried. For Gray to do so during a pandemic only confirms that the apartheid of citizenship supersedes any other identifier one may carry.

Privileges, opportunities, and discrimination ascribed to citizenship is so normalized it contradicts every single liberal value preached by Western leaders and pundits. Would we ever stand for a travel system that explicitly discriminates based on skin color, gender, or sexual orientation? Yet segregation based on citizenship is wholly accepted. Would Europe���s liberal bastion, the Netherlands, which has one immigration line for the passports of wealthy, mostly Western, countries and one for the wretched rest of us at Schipol Airport, ever create two separate lanes based on race?

���The dilemma,��� wrote citizenship scholar Dimitry Kochenov in a study, ���is thus quite a simple one: either we practice our ideals of human dignity and equal human worth���or we practice citizenship.���

Everyone on the wrong side of global citizenship apartheid has had enough. Consider my viral tweet of Thailand���s now rescinded pandemic travel requirements for European tourists, which demanded a minimum balance of 15,000 euros for six months, a hurdle many of us are all too accustomed to even apply to visit, and for some simply transit through Europe. Holders of unworthy passports���the vast majority of humanity���applauded Thailand���s decision loudly, demanding their own countries take a similar stand. Many reacting in glee were Indonesians. Outrage at Gray���s callous disregard for the untold powers of a US passport is merely another salvo against a despised and unsustainable system of global movement during an opportune moment to radically reform our economies.

But ours remains an open place. We welcome many, an integral part of our ancient Vedic ways. That openness was once structurally reserved for one class of people. Today, Southeast Asia, with its historic ties to Black America and Africa, especially Indonesia, where Afro-Asian unity was cemented in Bandung, has a duty to remain open for Black people worldwide. Our gates should firmly welcome Black Americans seeking escape from a country with rampaging white supremacists. That everyone must respect the law goes without saying. But precedence demands that one of the very few Black women travelers in the region should be allowed to err once without vast condemnation or harsh legal recourse.

I���ve known enough European men arrested and deported for repeated transgressions only to re-enter not long after on the same passport with their records essentially wiped clean. Resentment should be channeled against the 21st century���s apartheid of citizenship that millions before Gray have abused without cognizance or remorse.

Those who live under apartheid in their own societies finally making use of the privileges their papers afford them should be a welcome development. Doing so with wholesome responsibility is the logical next step. Young women of European descent have paraded their lifestyles on the beaches, islands, and rooftop infinity pools of Southeast Asia since social media became a thing. A 20-something Black woman doing the same, while in poor taste, does not deserve anything more than others have received.

Comedian Paul Mooney once said in a live stand up I attended in New York City that the ���most disrespected person in America is a Black woman.��� Southeast Asia is not America. Gray would be wise to heed Jamaica Kincaid���s lessons, recognize the ugliness of a tourist, and abandon emulating those who traveled before her. And if it wants to propel its relentless development, Southeast Asia must guarantee its shores always ferry distressed vessels to safety. If she ever returns, my home will always be open.

January 25, 2021

Remembering Benjamin

Image credit Benjamin Memorial Fund.

Image credit Benjamin Memorial Fund. In memory of Marit Hermansen (1955-2019) and her unflinching commitment to the anti-racist struggle in Norway.

Today, friends and family, local residents, and Norwegian anti-racists will once more gather at a small memorial at ��sbr��ten at Holmlia in Oslo East. They will be lighting candles and placing flowers at the base of the memorial. To the extent that they will be speaking among themselves, they will be speaking softly and pensively. They will be there to honor the memory of a life that could have been, and the ways in which the memory of that life continues to reverberate for many Black Norwegians facing contemporary circumstances which twenty years on for all too many of them have not changed all that much.

For it was a few minutes before midnight on January 26, 2001 that fifteen year-old Benjamin Hermansen was chased by two Norwegian neo-Nazis aligned with the Norwegian neo-Nazi skinhead group Boot Boys, and brutally knifed to death. Benjamin fell to the ground and expired on the wet and icy asphalt a few hundred meters from his home, very close to where the memorial statue now stands. It was only minutes after he been permitted to go outside for a brief late evening meeting with his best friend Hadi in front of a local shop that the two teenage boys were attacked by the neo-Nazis, who had traveled up from the suburb of B��ler earlier that evening.

The January 26, 2001 murder of Benjamin Hermansen is to date the most well-known racist murder in modern Norwegian history. As a proverbial critical event, it remains a central reference point not only for people in his own generation from Holmlia and the wider Oslo East, but also to a new and emergent generation of Norwegian anti-racists of multicultural background. One realizes as much from the many references to Benjamin in the posters seen at the Norwegian demonstrations in support of Black Lives Matter (BLM) and in protest against racism and police violence in the US which saw an estimated 10,000 Norwegians gathered in front of the Norwegian Parliament in Oslo in June 2020.

One sees it too in the ways in which Benjamin has been memorialized in any number of Norwegian prose works by Norwegian authors of multicultural background such as Camara Lundestad Joof, Zeshan Shakar, Yohan Shanmugaratnam, and Sumaya Jirde Ali in recent years. And last, but not least, in the references to Benjamin in the work of popular Norwegian hip-hop bands and artists such as Karpe Diem and Pumba.

In writing about the victims of racist terror, it is a constant temptation to write of them in a manner that reduces them and their lives to respectable exemplars of martyrdom. Benjamin Labaran Hermansen, ���Benny��� or ���Baloo,��� had been born to Habibu Labaran from Ghana, believed to be a Mfantsi and known as ���Bobby,��� and Marit Hermansen from Norway. His parents appear to have met on a night out in downtown Oslo in the early 1980s, near a club called The Leopard. The Leopard was known for playing reggae, and for being one of few clubs in Oslo that had patrons of African and Caribbean backgrounds. Habibu, who appears to have had something of an elite background in Ghana and to have come from family circumstances that enabled him to seek adventures in Europe, worked as an industrial painter. He was something of an African cosmopolitan, having lived in Greece and Germany before he ended up in Norway, and was described by Norwegians who knew him as both friendly, ���keen to integrate,��� and tolerant towards gays. He was also very proud of his first-born son, and was known as a good father.

Benjamin���s mother Marit had a working-class background and came from a close-knit family of four which had struggled with the early and premature death of their mother. Trained as a secretary, she would later become a primary school teacher. Benjamin was born in 1985, by which time the family had moved to Holmlia and ��sbr��ten. Holmlia was then a new housing development and part of the social democratic engineering that had been a fixture since 1945. It promised closeness to both the sea and the woods at affordable rates. ��sbr��ten and Holmlia would soon have some of the most multicultural population in Oslo and in Norway. Against the public and media representation of Holmlia and ��sbr��ten as dangerous urban spaces dominated by immigrants and immigrant gangs���a representation that remains unchanged until this day���people who grew up often provide a counter-memory in the form of a representation of Holmlia and ��sbr��ten as a convivial and safe place.

Benjamin���s father Habibu died in 1989 when Benjamin was only four. People who knew Benjamin describe him as handsome, popular, and a bit of a joker. He was no saint, sometimes inventing the wildest and funniest excuses for skipping his homework (such as alleging that his Labrador dog, Amba, had eaten his homework), pulling mild jokes on friends and schoolmates, eying girls, and getting involved in the occasional fight. He was also a keen and modestly good football player who dreamed of becoming a lawyer as an adult.

It is only on rare and exceptional occasions that news from Norway breaks through and into international news media. But the 2001 murder of Benjamin Hermansen and the 2002 trial against his racist and neo-Nazi murderers was extensively covered by The New York Times, the BBC World Service and The Guardian. In reading these news items 20 years after, one is struck by the extent to which the correspondents of these international news media outlets bought into a narrative of Norwegian exceptionalism in the face of racism and white supremacy. For to anyone familiar with modern Norwegian history and the dark racist undercurrents reverberating through that history,�� it certainly comes as puzzling news that the 2001 murder of Benjamin should have been the ���first racist murder��� in modern Norwegian history. Especially given that it was in 2001 only 11 years since the last recorded racist murder on a public street in Oslo had happened, when Ali Ghazanfar Shah (29), a Norwegian-Pakistani worker and father-to-be, was knifed to death in Oslo���s City Center in 1989.

The murder of Benjamin led to the largest anti-racist mobilizations in Norwegian history, with an estimated 40,000 people marching in a torchlight procession against racism in the Norwegian capital of Oslo, and thousands in other major Norwegian cities.

Gathered in Copenhagen for a meeting, cabinet ministers from the Nordic Council of Ministers adopted a statement condemning the murder and calling for action against racism. In a commemorative speech, the then-Norwegian Labor Party Prime Minister and now NATO Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg, called the murder a ���watershed moment” in Norwegian history and pledged ���never again.��� It would take ten years before he would use the very same rhetorical terms in response to the right-wing extremist terrorist attacks at Government Headquarters and at Ut��ya in 2011.

At ��sbr��ten, Holmlia, hordes of media reporters descended on school children and even on the shattered and bereaved Hermansen family. There were teenage friends of Benjamin���s who in the days and weeks after the murder had to cope not only with their own grief, fears, and terror relating to potential new neo-Nazi attacks in their neighborhood, but also with Norwegian media reporters hiding in the bushes on their way to school and intruding on local school yards in search of interviewees.

The active will to remember Benjamin now as ever stands against strong countervailing social and political currents in Norway. A central part of Norwegian political and intellectual elites��� long-standing mythologizing of Norway and Norwegians has long been to ���exceptionalize��� racism and right-wing extremism in Norway. That ���exceptionalizing��� has the practical effect of safe-guarding an idea of white innocence in which colonialism was, in the face of mounting historical evidence to the contrary, all about other Europeans and never about Norwegians, and racism and white supremacist phenomena pertained only to the far-right fringes in Norway. The idea of Norwegian exceptionalism and white innocence saw�� significant challenges in the 2001 murder of Benjamin, the July 22, 2011 terrorist attacks on Oslo and Ut��ya, and the August 10, 2019 terrorist attack on a mosque in B��rum outside of Oslo, but it still lingers on. One also sees it in the active historical erasure of colonialism, racism, and right-wing extremism in Norway in the best-selling work of certain Norwegian nationalist-populist historians, who in recent best-selling titles attempt to erase racist and right-wing extremist murders such as the murder of Benjamin from the Norwegian historical record.

���The very serious function of racism is distraction,��� Toni Morrison once said.

As in the US, the UK, and France in the Spring of 2020, the anti-racist mobilizations in support of Black Lives Matter (BLM) and the intense focus on anti-racism in Norway was met by a strong backlash in the form of fierce and often scurrilous attacks on anti-racism and anti-racist theory, both by liberal-conservative elites in academia and the media. Much of this was of course designed to distract and exasperate racialized minorities in the country. They, once more, were forced to ask what the point of bearing witness about racism and discrimination was, when a basic commitment to an ethics of listening is still so demonstrably absent among many Norwegians.

As people gather once more to commemorate the racist murder of Benjamin Hermansen at ��sbr��ten in Holmlia, they do so fully aware of the fact that racism remains a persistent challenge faced by Black Norwegians to this date, and that the anti-racist struggle in Norway is likely to be unending. This January has also brought news of years of demeaning racist harassment of some school children of Norwegian-African background at schools in Lillesand in Southern Norway and in Bergen in Western Norway. Empirical research on the experiences with self-reported racism and discrimination in Oslo schools indicate that one out of four minority children have experienced it.

In the public reading of the murder of Benjamin that would become dominant in the years that followed, and not the least through the 2002 trial against his neo-Nazi murderers in the Oslo Magistrate���s Court, these racist murderers would, much like in the case of Breivik merely ten years after, be portrayed as socially marginal and psychologically troubled characters coming from difficult family circumstances. But the main architect of Benjamin���s brutal murder, Ole Nikolai Kvisler, did in fact come from a stable and reportedly well-functioning family at ��sbr��ten, Holmlia, and in fact knew Benjamin very well from his childhood years. He had at the time of the murder been a thoroughly committed and ideologically motivated neo-Nazi for years. The toxicology reports in the police files relating to the murder of Benjamin reveal that Kvisler was only very lightly intoxicated at the time of the murder. It took Kvisler very few hours after the murder to get in touch with his far-right sympathizing lawyer, the Norwegian Supreme Court attorney Erik Gjems-Onstad (d. 2011), who was in Norway known for his long-standing support of the apartheid regime in South Africa and Ian Smith���s racist regime in Rhodesia. Nor has Kvisler ever expressed any remorse for his acts. He remained a neo-Nazi until his release in 2013, and there are many indications that he remains so even today.

One of the cardinal errors of Norwegian society after the murder of Hermansen was to believe that the threat of white supremacism and racism had all but disappeared. After all, Norwegian right-wing extremists had donned suits and abandoned the street fights that had been so central to their identity in the 1980s and 1990s and turned wage their racial war from behind PC screens. A second cardinal error was to retire the entire vocabulary of racism from the greater society. Those very errors would come to haunt Norway and Norwegians only ten years later in 2011.

Twenty years on from the brutal racist murder of fifteen-year old Benjamin Hermansen, the challenge of racism and discrimination is one which many Norwegians of similar background still face in their everyday lives. And this is exactly why the duty to remember Benjamin and his all-too-short life remains so central to many anti-racist Norwegians of all colors and creeds to this date.

From war-torn Europe to peaceful Africa

A group of Polish and African fieldworkers, probably in Tengeru, Tanganyika. From the collection of Katarzyna Oko, courtesy of Fatimah and Amena Amer.

A group of Polish and African fieldworkers, probably in Tengeru, Tanganyika. From the collection of Katarzyna Oko, courtesy of Fatimah and Amena Amer. This post, part of our Histories of Refuge series edited by Madina Thiam, is based on extensive historical research. Tembo���s work on Polish refugees in Zambia will be part of his forthcoming book War and Society in Colonial Zambia, 1939-53 that will be published by Ohio University Press. Lingelbach���s book On the Edges of Whiteness: Polish Refugees in Africa during and After the Second World War has just been published with Berghahn Books.

Less than eighty years ago, the Middle East and, particularly, Africa provided a safe haven for refugees from the misery in Europe. Thousands of Greeks and Yugoslavs fled from the fighting, famine and oppression to Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Ethiopia, Tanganyika (part of modern-day Tanzania), or the Congo. Some of them took the very same routes as today���s Middle Eastern and African refugees���just in the opposite direction. One of the largest refugee groups in Africa was some twenty thousand Polish people, who stayed from 1942 to 1950 in 20 refugee camps spread over Britain���s African colonies. Most of them lived in Uganda and Tanzania (then Tanganyika), a considerable number in Zambia (then Northern Rhodesia) and Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia) and some in Kenya and South Africa. However, their odyssey to Africa and their social position once there, were complicated.

For most Polish people, this odyssey started in 1940 on Poland���s eastern periphery with an angry knock on the door in the wee hours. Soviet occupation forces moved them at gunpoint to labor camps and special settlements in the Soviet interior. Once there, they had to fight for survival until the Polish government-in-exile in London and the Soviets reached a British-brokered agreement. Included in this accord was the release of all Poles in order to form an army to fight with the Allies against the Nazis. This army was eventually set up under British command in Iran. Over 100,000 Polish soldiers fought against the Axis in the Middle East, North Africa, and Italy. However, among the released Poles were not only soldiers, but also people who were not fit for military service. By July 1942, the number of civilians in Iran had risen to close to 40,000.

As the military situation in the Middle East worsened, the region became increasingly unsafe for refugees. Additionally, British strategists regarded the refugees as a problem to military logistics, hence the need to relocate them. Due to the strategic interest in having the Polish soldiers, the British government convinced the colonial administration in British East and Central Africa to host some 20,000 refugees for the duration of the war. While the Polish soldiers fought with the Allies, the civilians (mainly women, children, and the elderly) went to refugee camps in Africa.

The first African country to host Polish refugees was Zambia (then a colony known as Northern Rhodesia). The first party of 350 refugees composed of 131 men, 145 women, and 74 children left Cyprus for Palestine by ship en route to Zambia on July 21, 1941. The majority of them were urban middle-class and were accommodated in hotels and boarding houses in Lusaka, Monze, Mazabuka and Livingstone. The second, and much larger, group were Poles who had been deported to the Soviet Union and arrived from Iran in small batches beginning in mid-1942. By the end of 1943 there were nearly 3,500 Poles in Zambia. Much of the latter party was composed of peasants. They were accommodated in four camps, which had been set up in the towns of Abercorn, Lusaka, Fort Jameson, and Bwana Mkubwa.

Uganda and Tanzania hosted over six thousand refugees each, with the largest camps located in Tengeru (near Arusha), Koja (on a peninsula in Lake Victoria), and Masindi (in western Uganda). To get an idea of the dimensions, we must remember that during the war there were twice as many Poles in Uganda as other Europeans. In Tanzania every second European was a Polish refugee (for visual impressions see here). Kenya mainly served as a transit hub and Nairobi was the African center of the Polish and British refugee administration.

In the Zambian camps, the Poles lived in Kimberley burned brick buildings. The roofs were thatched with elephant grass���in essence showing the low status nature of their living conditions. In many respects, their way of life was not a departure from that of the majority local African population. Their dwellings were also an illustration that these people were meant to be temporal inhabitants, to be repatriated after the war. The camps were characterized by poor sanitation, in some cases leading to disease, prostitution, a shortage of consumer goods, and criminal activity. However, when compared to the living conditions of refugees in Europe at that time and life on the eastern periphery of Poland, the camps were an improvement. While life in the camps was a far cry from the living standards of European settlers, it was easily endurable. As a contemporary historian put it: ���[They] continued to live in favorable conditions in a European though colonial environment, 5,000 miles from European problems and unconcerned about their future.���

Reasons for their relative comfort can be found in the colonial division of society. The colonial administration was concerned about a possible loss of ���white prestige��� and the blurring of the dividing line between colonizer and colonized. Poor, peasant-class, Eastern European whites had much in common with other ���poor whites.��� Consequently, they had to be controlled, isolated (in camps) and lifted to a certain standard. The narrative of Europe in the colonies at the time was of a continent that enjoyed a higher standard of living than was the reality. Subsequently, thousands of Africans were employed to build the camps for the refugees (some were even conscripted), hundreds more worked maintenance at the camps���fetching water, cutting wood, carrying food, guarding, cooking, and emptying latrines. Refugees received sufficient rations, pocket money, healthcare, and accommodation from the colonial administration. The Polish administration established a complete Polish school system in the camps. Additionally, the refugees received donations from the Red Cross, the YMCA, as well as Catholic and Polish diaspora organizations.

When the war ended in 1945, the majority of the refugees did not want to return home to the new Communist regime that had taken power, and the eastern part of Poland had been absorbed into the Soviet Union. Only a few opted for voluntary repatriation. The demobilized Polish soldiers were allowed to settle in Britain and in 1948, about two thirds of the Poles were allowed to join them there. Some were resettled to Australia or managed to obtain visas to travel elsewhere. Only about one thousand Poles were given permission to settle in Africa. Colonial governments and European settlers were reluctant to allow this problematic group to stay permanently. In Zambia, the local English population feared that the job market would be devalued if more Poles were permitted to remain. This is similar to today���s situation whereby thousands of people from poor and war-torn countries risk their lives to seek asylum in the global North, albeit with not much success for all of them. Zimbabwe���s white settlers regarded them as inferior and a threat to British dominance. Throughout the colonies, African activists were challenging British dominance. In this volatile climate, poor white refugees were seen as a complicating factor and colonial governments made it clear that they were not welcome.

The history of Polish (and other European) refugees in Africa shows us that flight directions are changing. Today���s safe havens are yesterday���s battlefields. It is also a reminder that ���the refugee��� was never a universal category. In different places, and at different times, refugees were and are treated differently. Compared to today���s African refugees in Europe, the European war refugees in colonial Africa found themselves in a privileged position.

January 24, 2021

The complete revolutionary

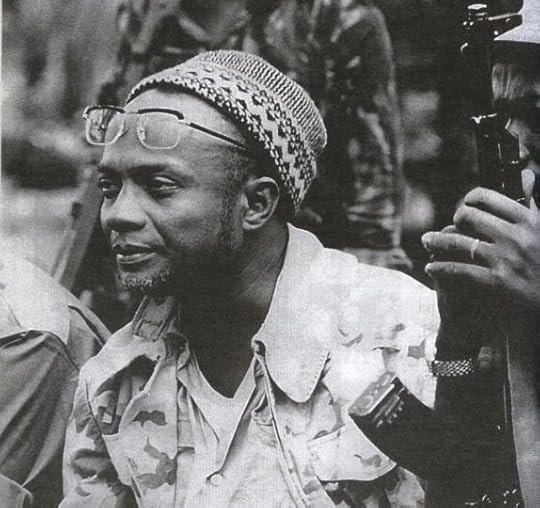

Amilcar Cabral

Amilcar Cabral Am��lcar Cabral was the complete revolutionary: an astute theoretician, fierce fighter and gracious politician (with a professional background as an agronomist to boot). Part of a generation of anti-colonial leaders who were ���gone too soon������which include the likes of Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, and Samora Machel���Cabral succumbed to a similar fate, and was assassinated by collaborationists on January 20, 1973 at the young age of 48.

Cabral led the liberation struggle which culminated in the full independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde from Portuguese rule in 1975. A co-founder of the Partido Africano para a Independ��ncia da Guin�� e Cabo Verde (PAIGC, or African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde), Cabral not only played an integral role in its successful armed struggle which�� caused some to dub Guinea-Bissau ���Portugal���s Vietnam,��� but also steered its ideological orientation and the development of its guiding, revolutionary theory. Cabral famously urged his party���and indeed all of us���to ���Hide nothing from the masses of our people. Tell no lies. Expose lies whenever they are told. Mask no difficulties, mistakes, failures. Claim no easy victories������

Given the historical rarity of his ability to blend theory and practice, of his sensitivity to the particular and the universal, and of his devotion to the national and international, it is no wonder then that Cabral is an enduring inspiration for Africans plus non-Africans alike, including our dear friend and comrade, the late Michael Brooks (1983-2020). Michael���s famous exhortation to ���Be ruthless with the system, be kind with the people,��� reads like a Cabralian phrase par excellence. We���ll be thinking of Michael during this episode, who six months ago also left us too soon.

Joining us then to discuss Cabral���s legacy are Ant��nio Tom��s and Ricci Shryock. Ant��nio is an anthropologist, trained at Columbia University and currently teaching in the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg. Using newly available archival resources, Ant��nio has just written a new biographical study of the life and thought of Cabral, called Am��lcar Cabral, the Life of a reluctant nationalist (forthcoming, 2021). We���d like to ask Ant��nio questions like, why was Cabral a reluctant nationalist? It is this and many other elements of his social and political thought (such as his belief that Portuguese could be an African language), that make Cabral a useful thinker for many of the dilemmas around identity, class and culture that persist in post-colonial states today.

And then, speaking of post-colonial states today����� what has become of Cape Verdean and Guinea Bissauan politics after independence, and after Cabral? This is a much neglected question that we hope Ricci can enlighten us on. Ricci is a journalist and photographer living in Dakar, Senegal, covering West and Central Africa. She is also part of Africa Is A Country���s inaugural class of fellows, working on a project about the role of women in Guinea-Bissau���s liberation war���another neglected topic, and another thing we hope Ricci can enlighten us on.

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 SAST, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

If you missed last week���s episode (our first episode of 2021), we were joined by Achal Prabhala and Indira Govender to discuss the politics of vaccines���who���s making them, how are they being distributed, who���s afraid of taking them and why. It was extremely helpful for anyone as confused as we were by the quick-pace of vaccine-related developments, in a climate of so much disinformation.

Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

January 22, 2021

Death by pesticide

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash Kenyan farmers, horticultural workers, and consumers continue to be exposed to toxic pesticides brought in from China and the EU, the two largest exporters of these chemicals to Kenya. Though flagged for their toxicity in the Europe, a variety of products from BASF, Bayer Ag and Syngenta are used widely in the country and with detrimental human and environmental effects. While civil society actors are campaigning to have these banned in the country, the government remains ineffective and complicit.

Arrive in any remote village or town in Kenya and chances are high that the first thing you will spot is an agrovet shop stocked with all manner of pesticides. These chemical compounds are commonly used in agriculture and animal husbandry to kill pests, including insects and rodents, and to remove fungi and weeds and control disease vectors.

Synthetic pesticides are a child of the Second World War. In her book��The Silent Spring, Rachel Carson notes that in the course of developing chemical weapons, some of the chemicals created in laboratories were found to be lethal for insects. The discovery was not entirely by chance as insects were widely used to test chemical agents intended for chemical warfare.

The association of synthetic pesticides with the Second World War has not deterred their usage across the globe. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that globally, about��4.12 million tons of pesticides��were used in agriculture in 2018. In Kenya, where they are presumed to have been introduced during the colonial era, the demand for these pesticides (fungicides, herbicides, fumigants, and insecticides) skyrocketed from��6,400 tonnes in 2015 to 15,600 tons in 2018.

This demand can be attributed to Kenya���s agricultural sector being heavily dependent on conventional methods of food production. This is often characterized by the heavy application of chemical pesticides and fertilizers in an effort to increase yields. For instance, in the larger tea and coffee plantations in Kenya, herbicides are seen as an effective method of weed control. A��study by Chepkirui, Gatebe, and Mburu reveals that small-scale tea growers in Bomet County preferred to use glyphosate to control weeds in the tea farms, with Roundup (distributed by Monsanto, now Bayer) being the most preferred at 53.7% compared to other formulations of glyphosate (Glycel, Touchdown, Wound-Out).

Glyphosate, a pesticide in the category of organophosphates, was first introduced in 1974 by Monsanto (now Bayer) and has been under great scrutiny for its ability to cause cancer. In March 2015, glyphosate��was classified as probably carcinogenic��to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer based on a positive association between exposure to glyphosate and cancer. One such case was Dewayne Johnson���s, a groundsman in the United States, where��Monsanto was found liable for causing his cancer��through exposure to Roundup.

Organophosphate pesticides (malathion, glyphosate, fenitrothion and chlorpyrifos) have been shown to be��highly toxic��to non-target species including humans, although they are still widely used in households and in agriculture. These chemical compounds were initially developed as human nerve gas agents in the 1930s and 1940s and later repurposed as insecticides.

Their insecticidal properties were discovered by a��German scientist, Gerhard Schrader, in the late 1930s��and soon afterwards the German government saw the value of these chemicals as new and devastating weapons in chemical warfare and the work on their development was declared a state secret. Some such as sarin and tabun were developed into��deadly human nerve gases��while others of a close chemical structure were used as insecticides after the Second World War.

Malathion is a��neurotoxic��organophosphate pesticide that has been classified by the��International Agency for Research on Cancer��as a probable carcinogen. Yet it is still sold in Kenya and is contained in 14 products according to information on the Pest Control Products Board (PCPB) website. Fenitrothion, another organophosphate pesticide that is known to be an endocrine disruptor (alters the hormonal system) and that is not approved for use in the European Union (EU), was��used by the Kenyan government to control the locust infestation that occurred in early 2020.

These and other organophosphates are responsible for thousands of cases of poisoning in Kenya. In 2016,��R.K.A Sang and J. Kimani��reported that 35 out of 716 individuals aged between 15 and 40 years attending Kericho Referral Hospital in March and April of that year suffered from organophosphate poisoning. These harmful effects are not only associated with organophosphates but also with other pesticides.��For instance, a study to examine the��impact of pesticides on the health of residents and horticultural workers in the Lake Naivasha Region��found that horticultural workers who underwent a clinical examination exhibited more cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurological disorders compared to other workers.

These pesticides not only impact our bodies but also the soil, food, and water resources. Organochlorine pesticides (DDT, aldrin and endosulfan) were found in the soils in the Nyando River Catchment in 2015 despite being banned from use in Kenya in 1986, 2004, and 2011, respectively. Kenyan exports of horticultural produce have been rejected by the EU for surpassing the maximum residue levels allowed.��Sukuma wiki (kales) and tomatoes from Kirinyaga and Muran���ga counties��were recently found to contain high levels of harmful pesticides.

Pesticides should therefore be a concern to us and their use and disposal should be more strictly regulated as they have the capability to enter and alter the most vital processes of the body in deadly and sinister ways. In Kenya, the PCPB, a statutory organ of the government, is responsible for the regulation, importation, exportation, manufacturing, distribution, transportation, sale, disposal, and safe use of pest control products. It was formed under the��Pest Control Products Act, Cap 346 of the Laws of Kenya. Since its enactment in 1982, this law governs the registration of many conventional chemical pesticides and biopesticides.

Currently, there are��19 active ingredients not listed in the European database and 77��have been withdrawn from the European market or are heavily restricted in their use due to potential chronic health effects, environmental persistence, and high toxicity towards fish or bees.

The Pest Control Products (Registration) (Amendment) Regulations, 2015��(Form A4 sections 3.7a, 3.8 and 3.9) require an applicant to show proof of registration of any new pesticides in the country of manufacture and in other countries. Also required is information on whether the new pesticide is registered in the country of formulation. It is therefore uncertain on what basis these pesticides were registered for use in Kenya.

Moreover, for any pesticide to be sold, used, or withdrawn from the EU, it must be authorized in the EU country concerned as per��Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009. This legislation regulates the introduction of pesticides in the EU market and lays out the rules and procedures for their authorization.

Following the renewal of approval of an active substance, all pesticides containing that active substance must undergo a renewal assessment to make sure that products comply with the updated assessment of the active substance and with the new scientific and technical knowledge.

It is clear that some pesticide manufacturers do not register or re-register products they know would not be authorized in their home country within the EU but, for profit-making purposes, continue to produce and export those products to other countries such as Kenya. Manifestly, the PCPB does not carry out due diligence before approving such pesticides for use in Kenya despite its mandate to ensure that pesticides sold in the country have been assessed for safety to humans and the environment.

Pesticide registration standards in Kenya are often benchmarked against the EU systems since the EU follows a comprehensive regime and best practices in food systems as well as strictly applying the��precautionary principle. Yet the fact is that the EU is the second-highest exporter of pesticides to Kenya after China, and the products registered in Kenya, which have been withdrawn from the European market, are sold by��European companies (77 products).

Despite there being 36 different European companies in the sector, more than half of the products (57%) are registered by BASF, Bayer Ag, and Syngenta.��Coincidentally, BASF and Bayer were part of the chemical companies that formed I.G Farben, a German chemical conglomerate, in December 1925.��In the 1920s and 1930s, I.G Farben screened Zyklon B (a toxic gas made from hydrogen cyanide and originally developed as a pesticide) for Adolf Hitler���s program to exterminate the Jews and used nerve gases on victims of the Holocaust in concentration camps. I.G Farben also specialized in the production of sarin and tabun, both of which are classified as organophosphates and were used as��nerve gases in the Nazi concentration camps.

Kenyan farmers and consumers are highly exposed to lethal pesticides whose impact goes beyond altering the hormonal system of plants and insects and degrading the environment to also damage the immune and nervous systems of the human body. Given the financial muscle of the manufacturers, the use of these harmful pesticides remains unchallenged by the government agencies supposed to protect Kenyans.

It is on these grounds that civil society organizations such as Route to Food, Kenya Organic Agriculture Network (KOAN) and Greenpeace Africa are seeking support from members of the public through a��petition��to place a ban on these harmful pesticides and encourage the use of biopesticides and plant extracts in food production.

Biopesticides and plant extracts such as Neem, chili and garlic are effective in the control of pests and diseases with no negative health and environmental impacts. Ecological and organic farmers have been using these ecological and traditional methods to combat pests such as the fall armyworm and they have proven to be efficient. These methods have also been shown to increase soil fertility without the use of harmful chemicals, improve farm biodiversity, encourage the use locally available resources (indigenous seeds) and help put producers rather than corporations in control of the food chain.

It is therefore time to advocate for these safe agricultural practices that guarantee us safe food, clean water and healthy soils. Our collective voice is critical in ensuring that our human right to safe food and to a clean and healthy environment, enshrined in our constitution, is upheld.

January 21, 2021

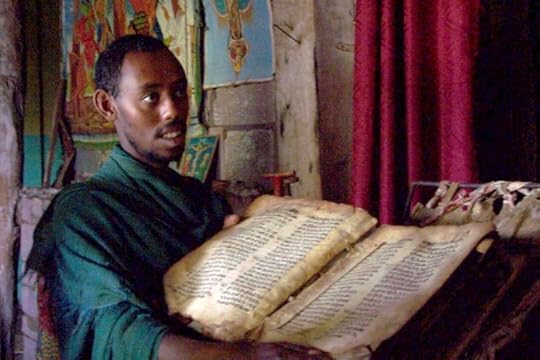

A gateway to the Black Indian Ocean

Image by Afrikit from Pixabay

Image by Afrikit from Pixabay Sometimes when you dive into an internet wormhole, it takes you through a portal, and you pop out in another dimension. At least, that���s what it feels like happened to me when I started to do research for this month���s episode of Africa Is a Country Radio. As I was deciding on which port city in East Africa to focus on, I started wondering about the possibility of applying Paul Gilroy���s theory of the Black Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. Having spent time in both western and eastern Asia, I was already familiar with communities of Afro-descended peoples scattered across that continent (from both ancient and contemporary migrations), so I knew that there was a deep connection between Africa and Asia. What I didn’t realize is how deep and close that connection actually was.

The diversity of experiences across the rim of the Indian Ocean for both African and Asians is what shocked me most. Migrations, often shaped by painful histories of enslavement and colonization, have shaped culture and politics, religion and identity in this part of the world for tens of thousands of years. And the more I learned, the more stories of the Black Indian Ocean began to reveal some sides of human history that I had never considered.

In our contemporary world, the relationship between Asia and Africa has gotten renewed interest in international circles. With China making its mark on the world as a superpower, and investing particularly in the development of many African countries, some of that interest is marked by an anxiety in the West. And perhaps some of this anxiety is justified considering, as AIAC contributor Vik Sohonie wrote for us, there was a time when African and Asian leaders looked to each other for guidance when coming out of centuries of European domination. Today, as the West continues to convulse from various crises, the ties between these two continents might be the nexus of global power in the next century and beyond.

So in this show, we use music as a launchpad from which to think about the long historical relationship between Africa and Asia, how that manifests in contemporary culture and national identity, and ruminate, briefly, on what possible futures a world that revolves around Asian and African exchange might hold.

In the second half of the show, we will zero in on a unique case study, the port city of Djibouti, and will be joined by Vik Sohonie himself, who also runs the Ostinato Records music label and is working on producing albums of Djiboutian music for international release today.

Tune in this Friday, January 22nd, from 2pm-4pm GMT (9am-11am EST) on the Worldwide FM live feed. If you miss it, visit our show page where the show will be archived. For those of you following us on Mixcloud the shows will continue to be reposted there.

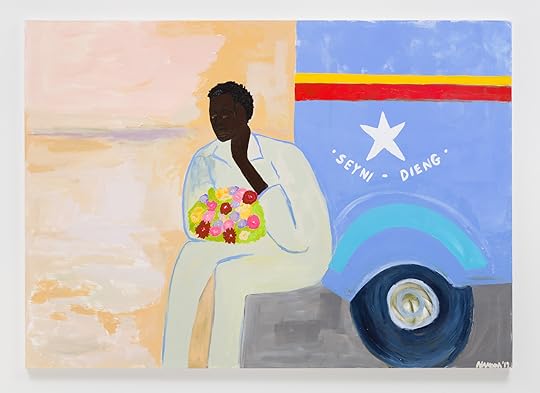

Painting personal histories

Cassi Namoda.

Cassi Namoda. Through her paintings, Cassi Namoda humanizes the lives and stories of often neglected and erased historical actors. Namoda imagines and renders figures previously deemed by society as unworthy of hagiographic visual depiction. The figures she depicts come to her through her own dreams, thoughts, and photographs that she astutely interrogates. She was born in Maputo, Mozambique, but to see her as a Mozambican painter is a narrow lens on her expansive and performative practice that spans from Mozambique to Los Angeles and now East Hampton, New York. (She also grew up partly in Benin, Haiti, and the United States.) Namoda is accustomed to her audiences not knowing how to place her and her artwork. She does not feel the need to fit into artificial collection categories, such as ���African��� or ���American.��� She is proudly peripatetic in her travels and artistic influences, which specifically range from German Expression to the late Kenyan philosopher John Mbiti. Part of her practice involves looking at family, documentary, and colonial photographs. She is attentive to the perspective of photographers, but keenly interested in how photographed sitters look back at the camera. Painting is a way to see from the limits of photography and to imagine anew. Through illustrated moments in time, viewpoints, and emotions that are too easily dismissed, her ultimate aim is to challenge audiences to consider the pain and joy of others.

Namoda is coming off a busy 2020. At the start of the year, she opened at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, Little is Enough for Those in Love. She finished the year with To Live Long is To See Much, her first show in South Africa at Goodman Gallery���s Johannesburg location (November 21, 2020 to January 16, 2021). Namoda spoke from East Hampton, New York to AIAC contributor, Drew Thompson, about her recent exhibitions, the personal histories that inspire her, and how she situates her work within the rich lineage of mostly male Mozambican artists that have preceded her.

Little Is Enough Installation. View 11, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. Drew Thompson

Little Is Enough Installation. View 11, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. Drew Thompson Can we talk about your love for the Mozambican photographer Ricardo Rangel? When did you first see one of his images? I was struck because one of your first exhibitions was called ���Meat is Meat + Our Nightly Bread,��� a rift on one of his most famous series ���Our Nightly Bread.���

Cassi NamodaIn a more personal narrative, or context, to your question, my mother���s middle name is Maria, and I created this character out of Ricardo���s series in ���Our Nightly Bread,��� which was when he documented the red-light district Rua Ara��jo. [Ricardo���s photographs are] some of the best work to come out of African photography to date; there is nothing like it. I studied cinematography briefly, and I was always fascinated with lens art and the essence behind a photograph. I thought about how the world understands African photography and studio photography, and then to be able to look at someone like Ricardo���s work or [the Mozambican press-photographer] Kok Nam, I think stylistically was so different from anything that I had seen in the black-and-white gelatin prints. Then going deeper into it, I find out later that my mom was working with Ricardo, developing photographs at [weekly Mozambican magazine] Tempo [where Rangel worked as a photojournalist]. For me, it was really amazing, this was the time before I delved into painting. There was this cultural and familial connection.

Everyone [in Mozambique] fought for revolution, whether you were a woman or man, and some of the women���s duties were to create these secret farms to feed guerrillas and then to fight.�� But then [during Portuguese colonial rule] you had these women who became street walkers, [who] owned their own agency. [T]he work on paper, ���Meat is Meat + Our Nightly Bread��� (2017), was the prelude to me giving homage, or an ode, to Ricardo and translating it to the medium outside of photography. Those prints are black and white, [and] I was able to reimagine them in color with vibrancy. The three Marias would always show up [in my work] in different scales and scenarios. When I look at Rangel documenting [the lives of women] I am not looking at them as prostitutes. I am looking at these very beautiful women. Maria is a character of polarity, and this polarity is something that I examined in African life. There is�� a lot of polarity in terms of the exhaustion of living. Maria always shows up in different characters, reclined on bed, or in a bar, with a kind of sensitive red eye.

Drew ThompsonThe exhibition ���Meat is Meat. Meat is Meat��� (Los Angeles, CA, 2017) is very dark in subject matter and color. Your show ���Little is Enough for Those in Love��� is lighter and more colorful. How do you account for this transformation, from being engrossed in a personal history and working with varying shades of red and grey to one who is embracing a lighter color palette?

Cassi NamodaFor me painting is personal. I believe in duality. I think you can���t have joy without suffering. In some ways, I needed to provide something for people to walk away with that felt sensitive. I am not only thinking for others. I am also thinking for myself, to my truth. My truth at that moment [was that] we have to accept that a little will take us a long way. I mean that in a metaphorical sense, and literally. When I made that show for Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, I would wake up early. I just got my coffee and would go for walks around the bay. The examining of the nature came really through me. I was looking at the soft pinks of the sand, the pale yellows and blues, and I thought about it in relation to the beauty of African life. When I think about John Mbiti���s writings and sort of societal duties, it [life] is very sinful. You want to be a good member of your village or society, and to do so you must adhere to your responsibilities and those steps: You are born. When you are born, you will be named, but named again once you reach puberty. When you reach puberty, you shed blood for your ancestors for the land, and now you are a real person, real member of society. Now you have real responsibilities and that is to find a partner, to proceed in marriage, to have children�� and that���s the real work, the children, working with children to create homeostasis for your village. So, you have ���Family Portrait in Gur����, 2019���, and I thought about it in a contemporary more dualistic sense. Being a younger family from a town and being in a city in Africa, your family does not really know who you are. [There are] these gazes and those characters. A story that I wanted to give [in the exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery is] that it is not all dark from my side. A lot of people [say,] ���Cassi, you paint these said characters. I find them honest.���

Namoda. Sad Man with Flowers, 2020. Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. Drew Thompson

Namoda. Sad Man with Flowers, 2020. Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. Drew Thompson In that early work, there were such close ups of people and intimate relationships. There seems like there is a certain comfort with the distance, looking in, not as an outsiders but taking perspective. You are comfortable with both proximity and distance.

Cassi NamodaThat also, in a way, is something that I had to explore in my life and also come to understand. I grew up in New York during middle school, and then went to boarding school in West Africa, Benin. In Benin, I spent a lot of time in the home of Vodun. I spent a lot of time observing. When I think of my observations, they were not personal. They were made from a distance looking at a culture. Coming to understand some of the things that I deal with my own flesh. Then there is a class divide. For me someone like Mbiti, who I often refer to because I feel the closest to it, Africans don���t believe in wasting time, but we believe in producing time. I think this show with the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery was an actualization of all of that and then also has a static energy with the sand and flowers. [With the] conjoined twins on sand overlooking the marriage from a distance, there is sensitivity to space and time and progression of life. It feels as if there is circular motion to life. There is a lot of ideas around swimming, the women holding the conjoined twins tenderly, and even the two women peeling corn and papaya. It is less about the depictions and more about how they make you feel or how it makes you understand, relate to a time removed from you. Then, the gaze is something that reminds you that you are not a member of their society.

Drew ThompsonWhat kinds of moments in time are you seeking to capture, especially when considering how photography influences your practice? Could you also talk about where this idea of the conjoined twins comes from in order to think about a twining of portraiture or four sets of eyes that have to look without each other?

Cassi NamodaI am a twin. It is less about me about being a twin. When I did ���The Three Marias��� (2018), there were multiple eyes looking at you. Most of the time they were not looking at you [the viewer] in discourse between themselves. I am fascinated by the gaze. So, to have these conjoined twins, with the gaze maybe penetrating deeper. You are seeing them as one sole individual with multiple eyes. People want it [the significance of the conjoined twins] to be very literal; they want me to explain who the conjoined twins are. When I started painting the conjoined twins, I was not thinking about anyone specifically. Then I started research, and I learned about Christine and Millie McKoy, who were twins born in the 1800s into slavery in South Carolina. The context of [my] Goodman show, ���Too Live Long Is To See Much,��� is a little darker. I am thinking about haunting and enfreakment of the image, and how being in a Black body has been under this category. We have been treated as if we are other. I want to tell stories without overtly telling the same narrative as what is in the stratosphere right now. I have thought about taking agency over Christian and Millie, and rendering them in a beautiful and painterly light. Because their whole life they have been under medical enslavement. You know they were subjugated to doctors. It was a life that was not theirs. At the end of it all, with the money they made after travelling the world, they gave a lot to the Black community. I don���t think we know about them yet. I felt like I wanted to release them in some way. It is very cinematic for me. These characters just come through me. Until they are out of my system, or I need to put them to rest for a little bit, they will keep just showing up. I am very interested in anyone of color that has been sold to the world of queer, who has been de-freaked in a sort of horrible enslavement. It is a calling that I feel I need to bring; it is a sort of digression from how I usually tell stories, [which] are not personal to me but I do understand the idea of ancestral baggage. I think that is something that we can all, as people of color, relate to.

Drew ThompsonWhen I read some reviews of your work, I heard this idea of ���Lusotropical painting��� and how you engage ideas of colorblindness. How are you thinking about the dynamics of race and representation through your rendering of skin color?

Cassi NamodaAs a viewer, we are always thinking about who the painter is. I am not so fascinated with the idea of telling a racial story, but I am more interested in telling stories of a world that people might not seem so knowledgeable about. I am not just talking about Black people in general. [There is] this idea of broadening, or expanding our understanding, of African and Black life, in a world that people don���t know so much. I stress ���Lusophone��� or ���Lusotropical,��� because the real work of the work is with me, as a painter dealing with ���Lusotropical narrative.��� When you look at the titles, ���Smiling Woman in Angoche��� (2019) and ���Young woman makes a dress in Quelimane��� (2020), I think a lot about regionalism. When I am thinking about the character, I am not thinking about a Ghanaian or Kenyan girl, I am thinking about the girl that I know in my personal context in terms of my roots. I want people to feel curious and know more. It is not that I want you to step in and have an idea of what Black fatherhood is like or what it is like being a lady of the night in 1960s Mozambique through my paintings. I want to challenge what you might expect. With ���Little is Enough for Those in Love���, it felt necessary to be sensitive in a way that did not feel photographic. I wanted my viewers to think about what it is to make a painting or to color, composition or something that might be fascinating, and then maybe you can think about the figure. With ���Meat is Meat + Our Nightly Bread��� (2017), it was more about the emotion that you might share, and deep into the human psyche what isolation or sadness might feel like. We all feel that at times. I am interested in the in-between, like that in-between before crying or that in-between before laughing.

Namoda. Little is Enough For Those in Love. Mimi Nakupenda, 2020. Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. Drew Thompson

Namoda. Little is Enough For Those in Love. Mimi Nakupenda, 2020. Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. Drew Thompson I look at your work and I understand the inspiration from German Expressionism. Also, I can see cultural references with Mozambique, and am drawn to think about Mozambican artists like Malangatana Ngwenya and Alberto Chissano. How do you situate yourself in the artistic history of Mozambique just as you turn outwards to understand your personal dimension?

Cassi NamodaI always say to people who are not from Mozambique that the best way to understand Mozambique is through literature and painting. Magical realism is definitely the foundation of Mozambican expression. Malangatana worked off imagination and memory, and he also worked off a lot his dreams and nightmares. I can���t help but not make work thinking about Malangatana and Gon��alo Mabunda. Mozambique is still a young country and it is learning from itself. I feel like I have a duty to keep storytelling and exploring narratives around Mozambique. I feel that part of the identity about being from Mozambique is to be a creative, to be a writer, to make music, to do woodcarving. In my work I will often think about people like Picasso and Brancusi, who looked at African art works and carvings, and sort of implemented in their way [their own visions of Africa] that became in a way a savage work. [When] I think about African Expressionism, I am taking agency between the two, a love for European painting but still keeping it very much in the realm of belonging to the continent. In the work I made for Goodman Gallery, I am looking at Tingatinga. For me, that is African pointillism. I am negotiating how that might feel in the work, with sort of introducing pointillism meeting the two in the middle but keeping with the personal to me. I am sort of in between the two, keeping it open. It is the beauty of painting that you can have the breathing room for so many worlds to enter.

Drew ThompsonIn Mozambique, there are so few painters. So interesting to hear this rich history and connection that you have to photography, which strikes me as the history that would make you a photographer. Yet, you chose to be a painter. Why was that?