Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 145

December 14, 2020

Dezember

Wrapping up 2020, we decided to make our last AIAC Talk show of the year festive. So, we will host a rotating cast of guests that appeared on the show this first season.

Tune in Today, December 15th at 12pm in New York City, 7pm in Cairo, and 8pm in Addis Ababa on Youtube, Facebook, or Twitter.

Dezemba

Photo: Antoinette Engel.

Wrapping up 2020, we decided to make our last AIAC Talk show of the year festive. So, we will host a rotating cast of guests that appeared on the show this first season. (The show’s title, #Dezemba, is taken from the colloquial South African term for the annual holiday season, usually a feast of travel by migrants, BBQs (braais, tshisa nyamas) and long days at the beach. Though there, because of resurgent COVID-19 cases, the government is closing beaches in at least two provinces and placing a 11pm to 4am curfew.)

Tune in Today, December 15th at 12pm in New York City, 7pm in Cairo, and 8pm in Addis Ababa on Youtube, Facebook, or Twitter.

Your favorites — guests from this past season — may stop by:

Paul T Clarke

Madina Thiam / @thiamm

Phethani Madzivhandila / @phethani4

Alex Hotz / @alexhotzzz

Anakwa Dwamena / @Kwatrekwa

Benjamin Talton / @benjamintalton

Lily Saint / @LilyLSaint

Sohela Surajpal / @sohelasurajpal

Njabulo Ngidi / @NJABULON

Bhakti Shringarpure / @bhakti_shringa

Dylan Valley / @bro_slovo;

and Zachary Rosen / @zach_rosen

et al.

Soft targets

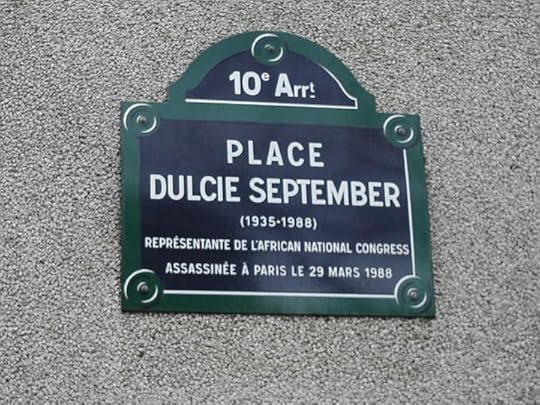

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Of the two high-profile assassinations of the 1980s in Western Europe linked to apartheid South Africa, the murder of Swedish Prime Minister Olaf Palme in 1986 was only resolved in�� June 2020, while that of Dulcie Evon September, the ANC���s most senior representative in France, Switzerland, and Luxembourg remains an unsolved case. At the time, these two brutal murders were met with wide condemnation and, justifiably, inspired a wave of theories. At the heart of these theories was the role of apartheid South Africa and its intelligence agencies.

The making of a revolutionary reformist

Widely considered the father of modern Swedish social democracy, Palme was a proponent of social equality, world peace, and a welfare state. Born into an upper class family (Palme���s family includes communists and landowners), he was shaped by his early experiences, including studying in the US, where he witnessed deep economic inequality and racial segregation. Palme joined the Swedish Social Democratic Party in 1951 at age 24.

Palme was elected as Prime Minister in 1969, aged 42. Hailed as perhaps the most popular head of state in Sweden���s history, Olof���s was described as a ���revolutionary reformist.��� He fought to establish Sweden as a radical welfare state, built upon the foundations of a good life for all. This formed the basis of his politics. His socialist politics and radical policies were met with resistance from Swedish capitalists. His radical opposition to the Vietnam War and apartheid South Africa made him an international hero������particularly in the global South.

On�� Friday, February 28, 1986, he was fatally wounded by a single gunshot on a central��Stockholm��street,��while walking home from a cinema with his wife��Lisbeth. Palme insisted on living like an ordinary Swede, walking around the city and catching public transport. What ensued was one of the biggest and longest criminal investigations in history.

One of the theories surrounding Palme���s death pointed to apartheid South Africa���s involvement. On February 21, 1986, a week before he was murdered, Palme made the keynote address to the��Swedish People’s Parliament Against Apartheid, a two-day event held in Stockholm, attended by hundreds of anti-apartheid supporters, as well as leaders and officials from the��ANC��and the��anti-apartheid movement,��such as��Oliver Tambo. In the address, Palme declared, ���Apartheid��cannot be reformed, it has to be abolished.���

A decade later, in September 1996, in the early years of South Africa���s transition to democracy, Colonel��Eugene de Kock, a former South African police officer and member of a secret apartheid death squad based out of the Vlakplaas farm, gave evidence to the Supreme Court in��Pretoria. De Kok alleged that Palme had been killed because he ���strongly opposed the apartheid regime and Sweden made substantial contributions to the then banned African National Congress (ANC).�����The motive for the assassination was to bring an end to Swedish support for the ANC.

The investigation into Palme���s murder abruptly ended in June 2020, when Swedish chief prosecutor Krister Petersson announced his conclusion that��Stig Engstr��m, also known as the ���Skandia Man��� and who committed suicide in 2000, was the most likely assassin.

Qui se souvient de Dulcie September

���My visit to France would be incomplete if I have not come here (Arcueil) to honor the memory of Dulcie September and see the college that carries her name.��� These words are from President Nelson Mandela���s tribute to September, on his historic visit to Arcueil in the Val de Marne, the Parisian suburb where Dulcie resided from her arrival in 1982. Mandela���s visit in July 1996 coincided with the annual anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille (July 14, 1789), the turning point of the French Revolution.

Within the confines of the small ANC office on the 4th floor at 28 Rue de Petites-Ecuries, September worked tirelessly, despite meagre resources, to mobilize opposition to apartheid in Europe. In France her mission was dependent on contacts with leftist trade unions and sympathetic groups, such as Oxfam, Amnesty International, the French trade union federation, Confederation General du Travail (CGT), the anti-racist Mouvement Contre le Racisme et pour l���Amitie entre les Peuples, and the communist-aligned women���s organization, l���Union des Femmes Francaises. The late Reggie September (not related), who completed a three-month military and intelligence course with her in Moscow, Russia, in the early 1980s, noted that Dulcie September had made huge strides toward exposing the illicit arms trade between France and the apartheid regime. ���The last few years she lived in constant fear of harassment, assault, and death,��� according to Ruth Lazarus, herself an expatriate and close friend, whom September had visited the weekend before her death. ���Dulcie ��tait mis��rable, lamenting how she misses her family and friends, Table Mountain and the fish and chips parcel she would usually buy on a Friday.���

On the terrible morning of Tuesday, March 29, 1988, September was assassinated as she was opening the ANC office after collecting the mail. Her funeral turned into a huge anti-apartheid demonstration, a manifestation of solidarity with the ANC. More than 20,000 mourners paid their last respects to September and marched to the Pere Lachaise cemetery���the scene of the last armed resistance of the Paris Commune of 1871. ���If ever there was a soft target, Dulcie September was one,��� Alfred Nzo wrote in tribute to her in the May 1988 edition of Sechaba, an official publicity organ of the ANC. Nzo claimed that Dulcie died at her post as honorably and with as great a dignity as any fighter who falls on the battlefield. ���That is the memory of her that we must always cherish,��� Nzo pleaded.

The careless and rushed French investigation into the assassination of September was the result of one of the most blatant frame jobs in French/apartheid South African history. Among the damning indictments of France���s blatant betrayal of the struggle against apartheid came from Jacqueline Derens, a member of the French anti-apartheid movement, who worked closely with September: ���The sanctions against South Africa were supposed to be compulsory, as ruled by the UN, but our government was not implementing them. We were incredibly angry, but we were just a group of activists fighting against money and power.���

It is no secret that there was a powerful pro-apartheid lobby in France at the time because France were selling petrol and arms as exposed by Hennie van Vuuren in his superlative account of the vast illegal trade that sustained apartheid���Apartheid, Guns and Money. The same arms were used by the South African army and police to kill those that resisted apartheid in South Africa and beyond.

Nollywood’s political struggle

At the #ENDSARS protest in Lagos. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

As Nigerians trooped to the streets in October to demand an end to police brutality, Nollywood was present. Online and off, actors and filmmakers made themselves useful in the most far-reaching display of people power recorded in Nigeria since the return to democracy in 1999. The demonstrations, known as #EndSARS, began after a viral video uncovered the gruesome murder of a young man by operatives of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), a notorious unit of the Nigerian police force. They ended tragically after members of the army were dispatched to the Lekki toll gate in Lagos to fire bullets at peaceful protesters.

Favorites from Nollywood, Nigeria���s film industry, were active and engaged. From lending their influential voices and drumming up international support, to attending protest venues physically and mobilizing relief materials and useful information. Actresses Kate Henshaw and Rita Dominic were photographed at the Lekki venue, fists clenched and raised in a show of solidarity. Hilda Dokubo made rallying videos that were widely circulated, and Genevieve Nnaji penned an open letter to President Muhammadu Buhari asking that he show some empathy to his electorate. Hint: He did not.

All of this conscious activity may have been surprising to many, but it shouldn���t be really. Nigerian arts have a long, documented history of political activism dating back to the heyday of Fela Kuti. But the film industry has been just as engaged, with filmmakers churning out material that actively engages with the socio-political issues of the time.

This activism has not been clearly defined of late even as���aka Nollywood���has recorded an upswing in international attention this past decade. In June 2020, streaming giant Netflix kicked off its ���Made by Africans, watched by the world��� media campaign that had Nollywood as one of the key anchors.

Nollywood���s appeal has long been based off the persuasion and power of representation. Following years of colonialism and dictatorship, Nigerians were searching for themselves on screens.

Films particularly fiction, remain complex industrial and social engagements. A product of their cultural and social environments, the modes of production, distribution, and exhibition go a long way in determining the content.

Chris Obi Rapu���s exponentially expanded the audience base of the straight-to-video format in 1992. This same mass appeal has alas been the bane of Nollywood. The ultra-low budgets, limited technical capacity, relatable stories, and modest distribution structure that made Nollywood content readily accessible also made it hard for proper investment in films. Thus, Nollywood content is likely to end up on the disposable rather than definitive spectrum.

Even so, filmmakers have striven to reflect the country around them in modest ways. Living in Bondage, for all of its entertainment value, is a critique of the overt greed and fast wealth environment of the 1990s, a period highlighted by a spate of killings and trade in body parts. This wealth was often directed to finance political campaigns. Amaka Igwe���s Rattlesnake details the crippling lack of a social safety net for the underprivileged. Both films���updated recently for a new generation by actor turned director Ramsey Nouah���are proper examples, not just of Nigerian crime stories, but of filmmakers inspired by the communities around them.

These films tended to incorporate positive depictions of police officers as defenders of law. If there was blame to be shared, the bulk of it went to the corrupt system that made it next to impossible for the police to function effectively. Tunji Bamishigbin���s Set It Off rip-off, Most Wanted had hardworking officers pursuing a gang of wily female bank robbers.

With his films Hostages and Owo Blow, Tade Ogidan broke from this narrative, depicting overt abuse of the social contract through acts of police brutality. Hostages in particular features a thrilling chase sequence that has the police at the behest of a wealthy patron, deploy helicopters and fancy weaponry to hunt a private citizen whom he considers an enemy.

With the police force becoming increasingly redundant to the average Nigerians, Nollywood films like Issakaba reflected this self-sourced pivot towards vigilante groups and private outfits to meet the security needs of communities.

Ego Boyo produced 30 Days, the debut actioner by Mildred Okwo about a team of female vigilantes killing off corrupt politicians. 30 Days is packed with subtext that criticizes citizen apathy and calls for a bloody revolution. It was never released widely. Okwo would follow up with the tamer The Meeting, a hilarious send up of bureaucracy in government offices. At the Lagos premiere, the minister of petroleum amongst other political heavyweights was in attendance.

���New Nollywood���

At the turn of the new century, following a spectacular decade run, Nollywood���s video heyday was on its last legs, helped along by uncontrolled piracy and technology. The industry pivoted to the theatres and a new generation of filmmakers were minted. With theatres came the pressure to put bums in seats and film executives began to adopt the impersonal, commercial approach to making films. All-star casts, romantic comedies and a certain glossy aesthetic that favored stories from upper class Lagos. Power players like AY Makun, Filmhouse, and Inkblot soon emerged.

These new power brokers didn���t just have the ears of the political elite who often supported their projects, they also played the media game and were able to attract local and international press for their projects.

The Goodluck Jonathan administration was particularly sympathetic to the arts and deployed resources to benefit the industry. At the same time, beloved Nollywood players began to test the political waters. Desmond Elliot was elected into the Lagos state parliament where he still holds a seat today. Tony ���One Week��� Muonagor held a similar elective position in Anambra state. Richard Mofe Damijo, Nkiru Sylvanus, and Femi Adebayo were all appointed into political positions. It is hard to quantify the impact of this trend beyond personal benefit, but it certainly helped keep the filmmaking elite and government on the same side. The unlikely result was a blunting of the industry���s edges.

Then there was the matter of the Nigerian Film and Videos Censors Board (NFVCB), a government agency that appointed itself the ultimate filter and moral arbiter of what Nigerians were allowed to consume. Films that strayed from the agency���s milquetoast vision of national identity were punished with a sledgehammer.

Fuelling Poverty, the 2012 AMAA winning documentary narrated by Wole Soyinka that detailed the events of the Occupy Nigeria mass movement, was banned from public exhibition. The director, Ishaya Bako would spend the next phase of his career making romantic comedies and kitchen sink dramas. He returned to political filmmaking last year with the NGO supported 4th Republic, a fine if toothless dramatic thriller.

The makers of Half of a Yellow Sun, the big screen adaptation of the Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie classic tome found themselves in hot water when they had to delay the film���s national release after the board declined to approve the film for public consumption. The ban was as Adichie described it, a ���a knee-jerk political response��� to fears that the film would incite violence.

Issues around censorship and classification have been recurring. This year, the censors board demanded edits before classifying The Milkmaid, Nigeria���s second submission for the Oscars best international film category. The Milkmaid is an ambitious epic that deals with female resilience and the protracted Boko Haram crisis in the North East.

Sometimes, it isn���t enough to scale the censorship hurdle. In January this year, the board temporarily recalled the benign romantic comedy, Sugar Rush, at the time the top grossing film in the country. A sister government agency had objected to the film���s negative portrayal of its operations.

Major filmmakers have taken the lessons and decided to steer clear of potentially problematic themes. Portrayals of brutality is high on this list. The record-breaking run of EbonyLife Films��� The Wedding Party movies at the box office also helped solidify a new profitable direction for the film industry: weddings, parties, romance, and generous shots of the iconic Lekki-Ikoyi link bridge.

Regardless, filmmakers have taken advantage of the industry���s diversity to make political work both in the mainstream and on the fringes. Kemi Adetiba���s 2018 feminist gangster thriller King of Boys was a surprise blockbuster success. King of Boys focuses on political corruption at high levels, although the ganger element is dominant and laid bare a familiar society bereft of principles where absolute power corrupts absolutely. The male protagonist, a resolute law enforcement operative, faces a crippling crisis of conscience when he comes face to face with the duplicitous nature of power.

Participating in protests is one thing, creating art that reflects the movement is yet another. Historically, successive mass demonstrations have failed to translate to definitive representation in films. But #EndSARS feels like an awakening in itself. The peaceful protests started as a rejection of police brutality, but it was also a cultural ground shifting, with a new generation learning to assert their readiness to lead.

Director Kunle Afolayan has indicated his interest in making a film about the movement. While his interpretation is likely to be watered down Hollywood derived schmaltz, more exciting are the young voices who were on ground filming and living the experience in real time. The proliferation of streaming platforms as alternative paths of exhibition and distribution offers hope that filmmakers can create challenging art that isn���t afraid to point fingers without negotiating the burden of state censorship.

December 13, 2020

Our distance from dirt

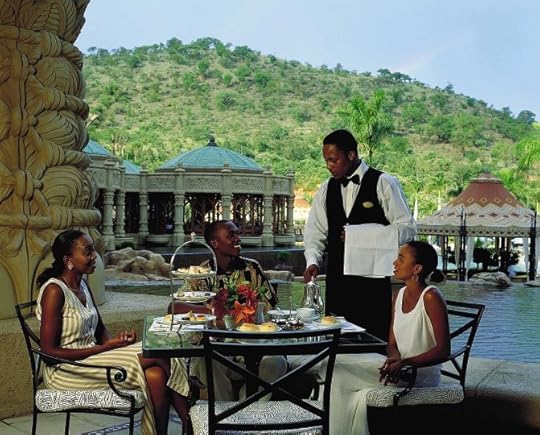

Lost City Eatery, Sun City. Image credit South African Tourism via Wikimedia Commons.

This post is part of our series ���Climate Politricks.���

It seems that every other month, a different segment of the online population awakens to the horrors of unjust extractive labor on the continent and elsewhere in the world. Clips of young children working in fields and toiling in ruthless mines beam up on our coltan-powered iPhones in punchy, bite-sized expository threads that at once arrest and implicate us. We clutch our unethically sourced pearls and confront these ugly truths of our consumption. Some of us linger on the news, some share and sign petitions and others, in the sort of torpor that fast-paced timelines tend to inspire, scroll on. For a moment, we rage but in time, another shareable injustice snags at our attention and we forget.

It is easy to forget when the mines are far away from our mobile phones. Many on the African continent who can consume these goods that are manufactured from violently extracted materials are, ourselves, distant from the land. This distance is built into our world, encoded in our economies and facilitated by how we consume. We pluck our food from shelves instead of branches, and source it from supermarkets rather than unearth it from the soil ourselves. We do not bend to wells or rivers, and our hands do not know the weight of hoes hoisted up into the air and hurled onto the soil. This distance is a part of how we live, and has significant implications on how we seek to make the world more equitable.

Marx���s theory of alienation offers something of a point of departure when I consider this distance. For those who aren���t familiar, Marx asserts that workers under capitalism are alienated from what they have a hand in making, and consumers are alienated from the goods they buy. This alienation accounts for our seasonal, short-lived shock. We are estranged from land and so far from the source of products and produce we use that their impact on people and on the environment is outside our view. But it matters to consider the extent and origins of this alienation, especially as we seek to imagine more equitable and just configurations of our world.

Part of this distance can be attributed to our colonized cosmologies. In them, notions of personhood are individualized, and decouple person from place, as if people exist in staunch separation from others and from the earth that they inhabit. In this framework, land is reduced to a commodity. Where land was once a sociocultural, spiritual, and filial entity, it is increasingly a purely economic one���a thing to be owned, mined, and expropriated, rather than a thing to be revered, protected, or exist in relationship with. This is one of the more insidious causes of our alienation, and is perhaps the one that should cause us the most grief.

A second factor is our discourses of development, which slot us along trajectories that set up Western standards and ideals as our destination. It is necessary for us to problematize these narratives, that are rooted in neoliberal ideas of what ���progress��� is. These aspirations hearken back to colonial frameworks of civilization, under which indigenous ideologies were relegated to the realm of dated primordial practices that are supposedly antithetical to modernity. They do not count our relationship (or lack thereof) with nature. They do not count the impact of our economic activity on our perception of the land.

Capitalism exacerbates this distance. It changes our connection to it from a relationship to a proprietorship. It puts land on a production line, puts tables far from the farm, and siphons water through pipes from distant lakes and rivers. It transforms us from producers of food to its consumers. It detaches us from the truth and violence that its conveniences necessitate. There is much to revisit, return to, and reconstruct in these ideas.

What happens when we reframe our understanding of what land is, beyond asset and capital? Land does, after all, hold significance that transcends discourses of development���land is about origin, about ancestry, and about our very notions of self. Distance from the land, in this sort of ideation, is a distance from ourselves. Re-centering the earth in our notions of selfhood and community is a necessary decolonial reframing. Until we stop considering the matters of land in such disembodied, impersonal ways, we will continue to exact and remain complicit in the kind of violence that capitalism requires for the maximization of profits. For as long as land is merely thought of as object, we will continue to slip further into estrangement from it.

The solution to our alienation from land is partly ideological. It entails radically rethinking our world, calling what we consider normative into question and returning to ways of being that we were asked to shun. It means reconsidering our cosmologies and our theories of not only who, but what has life and is worthy of dignity, and reconfiguring our understanding of personhood as it relates to nature and nature as it relates to personhood. It means acknowledging that our relationship to land informs our relationships to each other and to ourselves.

We need to be able to consider alternative possibilities of living with the earth on this continent. If there is not a restoration of notions of land that do not regard it merely as a thing to be transformed for capitalist gains, our forgetting will continue. Part of the answer to this lies in centering those of us who are closest to the earth���who are not in suits in big boardrooms in tall buildings. Those who are on the outskirts���who do the least damage to the earth and bear the greatest brunt of its degradation. It means forsaking our colonial notions of modernity and turning toward rurality to learn from those whose very survival entails that they live and work in tandem with the earth they inhabit. It is a shirking of systems that demand that we think of land as outside of ourselves. The land is ours, and it is us.

December 11, 2020

Murder as order

Two soldiers from the 1st Division of the Uganda National Resistance Army. Public domain image.

Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni justified the killings of over 60 plus civilians by security forces during the protests in support of Bobi Wine, who was detained while campaigning in late November. Despite the extremity of these actions, a bid to prevent both COVID-19 and “anarchy” have been cited as reasons for the severe heavy handedness of the police. But, as this article argues, this militaristic response to establishing “security” is not just a feature of the present, and emerges from a long history in Uganda of enacting “murder as order.”

This article is part of a series where we republish selected articles from The Elephant. The series is curated by Africa Is a Country editorial board member, Wangui Kimari.

In all too familiar scene, a number of Ugandan civilians were shot dead by men with guns (some in uniform) in the process of the National Resistance Army/Movement (NRA/M) government quelling public unrest in various locations around the country in mid-November. The disturbances, which mainly took the form of wananchi blocking highways with burning barricades, some stone-throwing, and also the emergence into broad daylight of muggers and highway robbers, had erupted because of the arrest and detention of the popular opposition presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi (aka Bobi Wine) and continued after a fashion until he was produced in court some six days later.

This is not to say that the reported sixty or so fatalities (and many more injured), largely from gunshots, were actively involved in the rioting. Neither is it to say it should be an acceptable method of stopping mass disturbances.

The best indications of how willfully random these shootings were are the oldest and the youngest shooting victims, both in Kampala city: Amos Segawa was a 15-year-old schoolboy who was killed while standing next to his mother while she locked up her shop as they prepared to leave town; John Kitobe, a 72-year-old retired former accountant and academic, who happened to be in town on personal business, was shot as he made his way out of an office building towards his car.

The intention was clear: deadly collective punishment in a deliberate act of mass intimidation in the name of ���security.��� This was a continuing fulfilment of a 2016 promise made by the Secretary General of the NRM party, one Justine Kasule Lumumba, to a restive population back then: ���The state will kill your children,��� she stated in a public speech to parents about the then post-election demonstrations. We now know that she meant their grandparents as well.

But this is completely normal. And that is the tragedy of Uganda���s politics. It is also the ultimate triumph of the NRA/M as an organization: to have seduced the country into mistaking the political value of security for valuable politics itself.

Without being forensic, one can trace a direct line from these latest killings back to the 1990 shooting dead of two Makerere University students at a sit-down strike protesting the abolition of student allowances; the military deployments against the repeated 1990s attempts by now-forgotten opposition activist Michael Kagwa to hold demonstrations for a return to multipartyism (eliciting the taunt from President Museveni for them to proceed ���if you wish to see dead bodies���); the increasingly regular violence from the 1996 election onwards; the 2009 Buganda uprising shootings; the 2010 shootings of demonstrators protesting the burning of Buganda���s royal tombs; and the 2016 killings of over one hundred Rwenzururu palace guards and others in Kasese, and so on.

There is absolutely nothing new in what has just happened, how it happened and what will (not) happen next.

The core item that the National Resistance Army brought to the political table in the 1980s was security. This has remained its primary identity, and key selling point���the issue that made many choose to ignore or overlook its multitude of sins, flaws, and contradictions, but also what made it so valuable to imperialism, concerned, as it has always been, with ensuring its grip on this bounty at the headwaters of the Nile, which feeds other areas of its bounty.

The backstory to this is very critical in understanding why the regime can send operatives on the streets���on foot and in random vehicles, without uniforms or insignia���to shoot to kill an assortment of civilians, with no consequences, domestically, internationally, legally or morally.

The space called Uganda has historically been unstable. However, it suffered two particular periods of intense social and political turmoil that resulted in armed conflict.

The core item that the National Resistance Army brought to the political table in the 1980s was security. This has remained its primary identity, and key selling point.

In the first instance, this was the politics that created the country, where, after some twenty years or so of preaching to children, they had raised an army of militant Christians who proceeded to conquer the region. What we call ���Uganda��� is actually the end-product of the 1899 victory of the Anglican Christian militia over the rival Muslim and the Catholic militias intent on the same goal: control the Nile at source, and therefore control Egypt. The victors have since then presented this factional advantage as the introduction of ���order,��� or ���peace,��� or even ���civilization��� to the region, delivering it from centuries of slave-dealing, war-mongering heathen African despots. They conveniently forget to mention that it was their religious activism that started the conflict in the first place. The underlying theme to this had been the propagandistic idea of Africa as a chaotic, brutal place in need of a civilizing order.

In the second instance, it is this very same theme that Yoweri Museveni and the National Resistance Army updated, mined extensively, and carried forward as the essential value of their project: their militarist outfit as the competent sub-contractors for the bearing of the White Man���s Burden, bringing an order to a place bedeviled by mad and incompetent despots. Again, what was not mentioned was how all those previous despots had been installed by the West in the first place.

So, the real ���consumer��� of this security has been the Western corporations, whose investments in minerals, agribusiness, predatory banking and the rest, are kept safe by these excellent askaris. Any local that benefited did so only as an afterthought.

Pax Anglicana

The everyday greeting in the Gisu area of Eastern Uganda is ���Mirembe?��� asked as a question.�� This word literally means ���peace.��� However, this is not the actual indigenous traditional greeting. It is a form of salutation that emerged from the Anglican military conquest of the East for the emerging British colony as its Christian army marched eastwards between 1898 and 190, under the trusted generalship of the Muganda Anglican Semei Kakungulu. It was a statement of affirmation between the greeters that all resistance was over, and the new dispensation was now imposed. Shall we accept it, and call that peace?

This is the birth of the duality in Ugandan political thinking, where the absence of overt conflict is mistaken for ���peace��� as an actual condition. It is a thinking birthed by the contradiction of colonialism: on the one hand, its need to extract and make profit off the colonized space means it must arrive through deception, blackmail, and a lot of violence. On the other hand, there needs to be some kind of order, if not regimentation, for exploitative production to then take place. It is that order that is being misnamed as peace, whereas in fact all it is, is the provision of some kind of security to the new owners.

Even after (southern) Ugandans eventually got tired of reminding each other of how much more ���secure��� their lives had become after the period of the overt military rulers between 1966 and 1986, the NRM continued to do it to them, loud and long, in the decades that followed. Certainly, business-oriented Ugandans (which is most of us) were initially relieved that they could go about their lives without having their homes and businesses invaded, or without being mugged and extorted by individual soldiers jealous of their progress. But they were unable to speak out because such private complaints could then be deliberately misunderstood as public political pronouncements against the government.

It is a thinking birthed by the contradiction of colonialism: on the one hand, its need to extract and make profit off the colonized space means it must arrive through deception, blackmail, and a lot of violence. On the other hand, there needs to be some kind of order, if not regimentation, for exploitative production to then take place.

There were only two flaws with this argument. First, most of north and northeastern Uganda were anything but secure, let alone peaceful, for the first nearly two decades of the NRM period. Second, it is the NRM regime that has gone on to facilitate the robbing, extortion, and mugging of the entire Ugandan society of their historically accumulated wealth by removing all remaining barriers to foreign capitalist looting.

Many could not see it then, in the main. ���Kasita twebaka ku ttulo��� (at least we get to sleep now) emerged as the smug, fatuous and deliberately disengaged response to any attempt to educate them about the new dictatorship being assembled in plain sight. The result is a society of economically and socially insecure, under-skilled, landless underemployed people whose plight has been articulated politically and musically by the very presidential candidate whose arrest sparked these disturbances. They certainly see it now.

So we are back to the stand-off set up in 1897, when the Anglican ���order��� first asserted itself by imposing a ���treaty��� on the throne of Buganda, using a two-day gunpoint ultimatum, in which tax revenue, control of weapons, and trade routes had to be surrendered to the Imperial British East African Company. This anti-native coup d�����tat thus check-mated the intentions toward the Nile of other imperial powers: Leopold���s Belgium from its Congo base in the West, Arab expansionism from Sudan in the north, and even the more remote French, German, and Italian speculations, embedded in the Catholic mission stations, and budding in military bases on the other side of Ethiopia, dreaming of an opportunity.

Whose violence, whose state?

The only violence the West will accept is violence carried out in its own interest, when it is replacing one regime with another, or when its chosen regime is keeping ���order.”

The mass killings in 1966 did not deter Britain from protecting the new government until it also became dispensable. Likewise, after the 1971 coup that brought Colonel Idi Amin to power, the West enjoyed very warm relations with him until he chose the other side in the Cold War.

Britain was deeply involved in seeking to violently destabilize the 1979-1980 post-Amin Marxist-led coalition government, and finally succeeded in toppling it through Paulo Muwanga���s May 1980 coup, which was the stepping stone to returning Milton Obote���s Uganda People���s Congress (UPC) party through the violent rigging of the December 1980 elections.

Britain then went on to heavily backstop the violence that the UPC government meted out to the population in an attempt to steady itself in power. When that government collapsed in June 1985, the West was faced with a choice of two purveyors of political violence: the Okello junta that had overthrown Obote, or the NRA/M, still recovering in western Uganda to where it had relocated following some better organized government offensives against it, just before the coup. Finally, the West settled on the NRA as its latest sweetheart, and after six months of heavy investment, January 1986 happened.

Like the original 1899 Anglican factional victory, it was sold as ���liberation��� and ���peace.��� In reality, it was the latest imposition of violent ���order��� by the real owners of the colony.

With the exception of Rwanda, Uganda is significantly smaller than any of the countries that border it. But these intense imperial maneuverings of over a century and half, plus her permanent presence in the commentaries of the Western media since the reign of Kabaka Muteesa I (r.1837-1884), betray an interest that far outweighs her relatively small size: again, the Nile headwaters, and all that flows from that physically, therefore economically, therefore strategically, therefore politically, and therefore militarily. The leadership of the NRM understood this intimately, and chose a side. And it was not the side of the native.

This is why, by contrast, any spontaneous or autonomous activity, especially one with a capacity for its own violence that cannot be imperially co-opted (as the NRA/M was) is brutally suppressed, as the NRM (now as a tool of the West) has done again and again with spontaneous outbursts, and before that in northern Uganda, to Buganda demonstrators, and to subjects of the Rwenzururu kingdom, as well as far beyond Uganda���s borders to ���secure order��� in the literal Eden, lying between the two Rift Valleys with the Nile at its center, for the Empire.

In all such cases, the West has, and will, look away, after maybe a bit of anodyne hand-wringing, just as a memsahib would not want to know the gory details of exactly how her houseboy removed a rat from her kitchen, only that he did it effectively. She will even indulge in a bit of grumbling about how much of a mess he has left her kitchen in, in the process. But the critical thing is that she wanted the rat killed, and now it is dead. Good boy.

So, political agitation is one thing, an actual uprising is quite another. It does not matter what the issue is, the West will not tolerate an actual popular uprising in Africa. The natives must never develop the means to reclaim what was taken from them at gunpoint in 1897.

Certainly, the natives must be prevented from regaining control over the source of the Nile.

This is why we have almost been workshopped to death by donor activism���to learn how to express our political aspirations within the acceptable (which basically means ineffective) methods and language of political careerism. Once we step outside those boundaries, either spontaneously or otherwise, then Kakungulu���s death machine is activated, and people are killed like kitchen rats until ���order��� is restored.

So, political agitation is one thing, an actual uprising is quite another. It does not matter what the issue is, the West will not tolerate an actual popular uprising in Africa. The natives must never develop the means to reclaim what was taken from them at gunpoint in 1897.

This is why we can experience a mass killing in the middle of a general election campaign, and the elections will still carry on. It is because these are, in fact, two separate ���political��� processes being implemented: one to keep the political classes co-opted, and the other to keep the natives excluded.

Nothing valuable, beautiful or just can be built on such an iniquitous foundation.

We need to be clear: what we have had was never ���peace,��� but simply security for the Empire���s interests.

And without real peace, even that security will eventually disappear.

December 10, 2020

A hug that listens

Still from Farewell Amor

Para portugu��s clique aqui.

The foreground, backlit and moving slowly, announces an airport arrivals terminal; its sounds, and images so recognizable for those leaving one place and arriving in another. The micro-space of airport arrivals and departures depicted in the film Farewell Amor is the perfect representation of the ���liquidity of the world��� that Zigmund Bauman spoke of���an uncertain and unpredictable world, with constant leaving, constant arriving.

Angola���s recent history is one of wars and dislocations. After 14 years of an anti-colonial war against the Estado Novo regime in Portugal, Angola fell into a civil war from 1975-2002. That war slowed entry to the train of the future: peace arrived with the Luena Accords in 2002. Those who escaped the war, leaving the country before the peace, became antennas of a world in constant movement. Many of those Angolans took what was easy to carry���dance, music, and various kinds of spirituality. The Angolan diaspora glued together utopias and futures until the fighting stopped. The slow consolidation of democracy continues to put off the healing of the wounds left by that past.

The Angolan presence in diaspora is distributed unevenly and thinly around the world with no reliable data to make it visible. The civil war caused waves of migration during the 1980s and 1990s. European cities like Rotterdam, Paris, and Lisbon have sizeable Angolan communities. In the US, Houston has a strong community linked to the oil industry. The size of the Angolan diaspora in the US is estimated as seven thousand residents. The film Farewell Amor touches on these communities spread across the world through the story of one family���s reunion.

It is the reunion of a family that had not seen each other for 17 years that is the motive for filmmaker Ekwa Msangi���s feature film debut. Msangi is a Tanzanian-American filmmaker living in Kenya. That is, she has routes and roots that she uses to construct a screenplay that accompanies three members of one family. The narrative alternates between the views of these main characters as they experience this re-encounter in New York City. The film focuses on the gestures and discourses of Walter, the father; Esther, the mother; and their daughter Sylvia. This trinity motivates our discussion of memory, trauma, music, and dance as practices capable of curing wounds, but also of projecting images, unknown sentiments, and the forms that constitute angolanidade (Angolanness).

Walter left first because of the war. He drives a taxi in this stereotypical great world city, the home of the American dream, also known as modernity. The diasporas and desires of many people start and end in New York City. Throughout the film, we learn that Walter is uncomfortable with the re-encounter. He has had to re-make his life���to find new ways of socializing, new lovers. He even learned to cook healthy food. He integrated himself into the routines of the Manhattan peninsula, the place of films and fictions. But that also included breaks to dance semba and kizomba at nightclubs. (The new millennium saw the circulation of these Angolan dances all over the world. The United States was no exception. Many came to know and include kizomba as ���African tango��� on dance floors. These Angolan dances were sold as machines of sensuality in a period of great individualism.)

For Walter, the dance and music are a kind of ritual connecting him to home through the lyrics of Bonga, Carlos Lamartine, and Eddy Tussa. Dance is a place to show off the body in public as well to process private emotions in what Marc Aug�� calls a ���non-space.��� Angola cannot be recreated in New York, but at the same time that ���non-place��� of Angola in North America will never be extinguished and is there in dance and speech. Memories are also made of silences and hiding places. And during 17 years away from Angola, Walter has made new memories. Walter tries to erase the trace of his second love, ���the other,��� in the voice of Angolan singer Matias Dam��sio; the clothes of the woman that he had learned to love and the necklace around her neck just like that of his daughter Sylvia.

Esther starts to intuit what is going on. Her life has been built on waiting and projection. Waiting to have Walter in her arms again and the hope for a better future for their family. In the end, distance dents expectations. The war left its marks. Situations of uncertainty transform priorities. And faith offers a safe spot for Esther. As Walter steadied himself in dance and music, Esther moved closer to the divine. She diluted her dreams in small moralities, not drinking, not wanting to dance, not letting her daughter Sylvia follow her dreams.

Sylvia wants to study, and she wants to dance kuduro. She begins to show the dance at school in New York. Young Angolan women carry this in their luggage���performances capable of attracting important things, like affirmation and vanity. And kuduro offers the power of self-transformation. Presenting herself to her new friends at school, Sylvia goes so far as to say she is the daughter of Angolan diplomats in New York.

Walter had already cautioned her. The city of films can be a terrible place for Black people. At the same time, it can be a place of possibilities. Lost possibilities in an Angola wrapped in the curse of conflict and war, entangled in dilemmas: how could a country full of resources and riches still be condemned to failure?

The film is about the power of love. Of love and affect. The family reunion puts into play three processes of memorialization and trauma. But, also, of an affect that can cure the wounds of the past, can offer forgiveness, and can create a future in the gestures and battles of kuduro. The challenges that are a part of kuduro, the ���beefs,��� as much as the images of war and peace but also of play and pleasure, are generative.

With a carefully curated soundtrack, well-crafted characters, Farewell Amor rephrases the question Waatao? (���what���s next?���) from Puto Prata���s song: ���it���s a big drain, our Luanda��� … while tears streak Esther���s cheeks as she asks: what do we do now? Walter responds with a hug and with his silence, he attempts to heal the damage of many years of trauma and suffering. Sylvia wins the dance competition, and the family reconciliation happens around the dinner table.

Manuel Canza, a great dancer and choreographer I have followed since he won the first edition of the Angolan Public Television (TPA) dance competition, Bounce, in 2008, is the film���s choreographer. The way in which he structured the kuduros steps and all their potential is amply evident in this film. Dance has been an important balm intermixed with the images and politics of Angolans around the world.

Angolans have made themselves in- and outside Angola, in conversation with the world. In the departures and arrivals, they carry with them the intangible and immaterial: intuition, faith, dance, and the sad and deep look of permanent uncertainty. But they also take with them the smile of resistance that can hide sadness and misfortunes.

Perhaps at arrivals and departures there isn���t much to say. Perhaps all that is needed is to listen in silence and with a hug. A hug that knows how to listen.

Um abra��o em escuta

Photo by Bruce Francis Cole, courtesy of Sundance Institute.

For English click here.

O primeiro plano, em contra luz e demorado, enuncia a ��rea de chegadas de um aeroporto, seus sons e imagens s��o por demais conhecidos. Por aqueles que chegam a um lugar, partindo de outro. Esse micro-lugar retratado no filme Farewell Amor, que �� das chegadas e partidas de um aeroporto, a representa����o ��ltima da ���liquidez do mundo��� de que nos falava Zigmund Bauman: o mundo da imprevisibilidade e da incerteza, a constante partida e a constante chegada.

A hist��ria recente de Angola �� uma hist��ria de longas guerras e desloca����es. Depois de catorze anos de uma guerra anti-colonial contra o regime do Estado Novo em Portugal, caiu numa guerra civil que correu de 1975 at�� 2002. O conflito civil atrasou a entrada no comboio do futuro. A assinatura da paz deu-se no ano de 2002 com os acordos de Luena. Quem escapou para o ���exterior���, antes da paz, acabou por funcionar como antenas do mundo em permanente movimento. Muitos desses angolanos e angolanas acabaram por exportar aquilo que tinham �� m��o – a dan��a, a m��sica e espiritualidades v��rias. A di��spora angolana funcionou como cola para utopias e futuros at�� ao calar das armas. A lenta consolida����o democr��tica continuam a adiar o sarar de feridas do passado.

No mundo a presen��a angolana est�� capilarmente distribu��da n��o havendo dados fidedignos. As vagas de migra����o deram-se sobretudo devido �� guerra civil durante as d��cadas de 1980 e 1990. Algumas cidades europeias como Roterd��o, Paris, Lisboa t��m muitos angolanos. Nos Estados Unidos da Am��rica a cidade de Houston tem uma forte comunidade ligada �� ind��stria petrol��fera. A di��spora angolana nos Estados Unidos da Am��rica est�� estimada em sete mil residentes. Farewell Amor fala dessas comunidades espalhadas pelo mundo atrav��s da reuni��o de uma fam��lia.

A reuni��o de uma fam��lia, que j�� n��o se via h�� dezassete anos, �� o mote para o filme Farewell Amor, da realizadora Ekwa Msangi, que se estreia na realiza����o de longas metragens. Uma realizadora que �� da Tanz��nia e da Am��rica e que vive na Qu��nia. Rotas e ra��zes que permitiram tra��ar este gui��o que acompanha tr��s membros de uma fam��lia.

A narrativa em altern��ncia segue as viv��ncias desse reencontro familiar na cidade de Nova Iorque. Os gestos e discursos de Walter, o pai, Esther, a m��e e Sylvia, a filha. Esta trindade ser�� o mote para discutirmos a mem��ria, o trauma e a m��sica e a dan��a como compet��ncias capazes de curar, mas tamb��m de projetar imagens, afetos t��o desconhecidos, as formas de que se reveste a angolanidade.

Walter partiu �� frente por causa da guerra. �� taxista numa cidade estere��tipo da grande metr��pole, ao mesmo tempo do sonho americano, mas tamb��m daquilo que se entende por modernidade. As di��sporas e desejos de muitas pessoas terminam e come��am em Nova Iorque. Ao longo do filme percebe-se que Walter est�� desconfort��vel com o reencontro. Afinal teve de refazer a sua vida. Encontrar novas sociabilidades, novas amantes. At�� aprendeu a cozinhar de forma saud��vel. Integrou-se nas rotinas da pen��nsula de Manhattan, lugar de filmes e fic����es. E claro, as pausas para dan��ar semba e kizomba na discoteca. O novo mil��nio assistiu �� explos��o e expans��o da circula����o destas dan��as angolanas um pouco por todo o mundo. Os Estados Unidos n��o foram excep����o. Muitos at�� come��aram a enquadrar a kizomba naquilo que nas pistas de dan��a se escutava como ���african tango���. A poderosa m��quina da sensualidade que estas dan��as angolanas conseguem vender numa altura de grande individualismo.

Para Walter a dan��a e a m��sica atua como ritual de liga����o �� terra atrav��s das letras de Bonga, Carlos Lamartine e Eddy Tussa. As passadas da vida feitas desejo, no entra e sai da pista de dan��a de um bar. A dan��a como lugar para mostrar o corpo em p��blico, ao mesmo tempo processar as emo����es privadas daquilo que Marc Aug�� chama de ���n��o-lugar���. A ideia de que aquele lugar chamado Angola nunca se consumar�� em Nova Iorque, ao mesmo tempo aquele n��o-lugar de Angola, na Am��rica do Norte, nunca se poder�� apagar. Porque as mem��rias s��o feitas de sil��ncios e esconderijos. Walter tenta apagar o rasto do segundo amor, ���a outra��� na voz de Matias Dam��sio. As roupas da mulher que entretanto aprendeu a amar, o colar no peito, igual ao da filha Sylvia.

Esther come��a a intuir o que se est�� a passar. A sua vida foi feita de espera e projec����o. Espera de voltar a ter Walter nos seus bra��os, a projec����o de um futuro melhor para a fam��lia. Afinal, a dist��ncia acaba por fazer mossa. A guerra deixou as suas marcas. A incerteza transforma prioridades. E a f�� pode ser o porto seguro. Enquanto que a dan��a e a m��sica seguravam Walter, Esther foi-se aproximando do divino. Foi diluindo os seus sonhos em pequenas moralidades, n��o beber ��lcool, n��o querer dan��ar, n��o deixar a filha Sylvia perseguir os seus sonhos.

A Sylvia quer estudar, mas tamb��m quer dan��ar kuduro. Mostrar-se no liceu em Nova Iorque. As angolanas levam isso na bagagem: performatividades capazes de trazer duas coisas importantes, afirma����o e vaidade. E o kuduro tem o poder de transformar imagens. At�� quando Sylvia mente e diz que �� filha de diplomatas angolanos em Nova Iorque.

Walter j�� tinha chamado �� aten����o. A cidade dos filmes pode ser um lugar terr��vel para quem �� negro. Ao mesmo tempo pode ser um lugar de possibilidades. Possibilidades perdidas em Angola envolta numa maldi����o de conflitos e guerra, enredada em dilemas: como �� que um pa��s cheio de recursos e riquezas continua votado ao falhan��o?

O filme �� sobre o poder do amor. Do amor e dos afetos. A reuni��o da fam��lia coloca em cena tr��s processos de memorializa����o e trauma. Mas tamb��m de afectos capazes de curar as feridas do passado, o perd��o, capazes de fazer o futuro nos gestos de uma batalha de kuduro. Os desafios, os ���bifes��� de kuduro como imagem de ���guerra��� e paz, mas tamb��m de brincadeira e folia.

Com uma banda sonora muito cuidada, personagens muito bem trabalhados, Farewell Amor reformula a pergunta ���Waatao���? da m��sica do Puto Prata: ���muita drena, nossa Luanda���… enquanto caem as l��grimas da cara de Esther seguindo da pergunta: O que fazemos agora? Walter responde num abra��o e em sil��ncio tenta curar as feridas de muitos anos de traumas e sofrimentos.

Sylvia consegue ganhar o concurso de dan��a e no final a reconcilia����o familiar acontece em torno da mesa e da comida. A di��spora angolana tem com este filme mais um contributo. Um deslocamento que acontece h�� centenas de anos entre a viol��ncia e genoc��dio do tr��fico escravista e a necessidade de fugir da guerra colonial e civil.

A parte coreogr��fica e cin��tica do filme est�� a cargo do grande bailarino e coreografo Manuel Canza, que felizmente acompanho desde o seu in��cio quando ganhou a primeira edi����o do concurso de dan��a Bounce emitido em 2008 na Televis��o P��blica de Angola. A forma como tem estruturado os passos do kuduro e as suas potencialidades t��m neste filme especial destaque. A dan��a tem sido um importante b��lsamo para a altera����o das imagens e pol��ticas dos angolanos e angolanas no mundo.

Os angolanos e angolanos t��m-se constru��do socialmente tamb��m fora de Angola e em di��logo com o mundo. Nessas partidas e chegadas levam uma bagagem do intang��vel, o imaterial: a intui����o, a f��, a dan��a e o olhar triste e profundo da permanente incerteza. E o sorriso como resist��ncia ��ltima de se esconder a tristeza, os infort��nios da vida.

Talvez �� chegada e na partida n��o seja preciso falar muito. Talvez seja preciso escutar em sil��ncio e num abra��o. Um abra��o em escuta.

Andr�� Soares trabalhou como jornalista cultural na r��dio e televis��o e �� actualmente doutorando em Antropologia na Universidade Nova de Lisboa e no ISCTE-IUL estudando semba como patrim��nio cultural intang��vel em Angola.

Unfinished liberatory agendas

Image credit Nii Nikoi (niinikoi.com) CC.

This article is part of the “Reclaiming Africa���s Early Post-Independence History” series from Post-Colonialisms Today (PCT), a research and advocacy project of activist-intellectuals on the continent recapturing progressive thought and policies from early post-independence Africa to address contemporary development challenges. It is adapted from a webinar of the same name, which you can watch here.

Amina Mama

Akua, you and I have a shared historic, intellectual, and political vantage point as the generation that immediately followed independence, the first generation of nationhood, when most of our nations won flag independence. I call it flag independence, as many of us do, because of the incomplete nature of our struggle. And yet, despite realizing that the process that began with decolonization was incomplete, much of our generation sees independence providing the basis for feminism on the continent, because it did not afford equal freedom to women. This is also the basis for socialism because the freedom of all people was not completed. So, all this is unfinished business, and yet few of us have seriously studied the first attempts at building our nations. We are once again in crisis, to be hit with the COVID pandemic, while at the same time, Black resistance is re-forming under the Black Lives Matter movement in the US. This is also happening just after the ���Year of Return��� in Ghana, so it���s an especially good time to reappraise what Africa tried to do and what its revolutionary post-independence leaders tried to offer, because we���re in another moment, one that may be as significant as the 20th century decolonization period was for our parents.

I had the pleasure of reading your paper on development planning in post-independence Tanzania and Ghana, which is part of the forthcoming Post-Colonialisms Today publication. I���m looking forward to discussing it, but my first question is more personal: What are your memories of the years of Nkrumah���s government? I know you were young, but as someone born, like me, just before political independence, what do you remember?

Akua O. Britwum

My memories are more of what happened after the coup. In 1966, when the coup occurred, I was in what was called an experimental school, which were schools in the public education system that were experimenting with new teaching and learning methods. After the coup, family members and the parents of friends were arrested and, over time, the economic and political situation in the country took a nosedive. My mind goes back to some of the things I took for granted, thinking back to the systems and the structures that we had���the buildings, the washrooms almost surgically clean, and our teachers, and the classroom space���that disappeared. There was a sense of insecurity that emerged. There is a lot to be said of the broader political moment: we were told Nkrumah was bad, that he was going to institute socialism where you couldn���t speak your mind, but those very things increased after Nkrumah was overthrown. But my memory is of those privileges that my school represented that we lost, of being involved in an experiment that was going to revamp our public educational system, that was suddenly gone.

Amina Mama

Yes, I���m currently busy retracing childhood memories and experiences of what were profound historic events that we didn���t realize at the time. When the coup happened in Nigeria, it affected all of us; I think many of our generation have an entry point where we knew there was great hope and then that great hope was crushed by decades of military dictatorship.

I do know that there were differences between Nkrumah and Nyerere’s philosophies. I understood Nyerere to be for the unity of separate nations, while Nkrumah’s vision was pan-African in the sense of a united states of Africa and very audacious. Was that the source of their different approaches to planning, or are there other factors���they were both socialist, but was their socialism different? Or was it the scale of their politics that differentiates?

Akua O. Britwum

I think it was more their politics that differentiated them, because, as I was pleasantly surprised to learn, Nyerere also had a Pan-African vision, but their two visions were very different. Both Nkrumah and Nyerere followed a socialist model because they saw capitalism was exploitative and felt socialism responded more to African communalist values. These communalist principles, almost humanist principles, were less adversarial and less exploitative, so they positioned African societies to leapfrog over capitalism straight into socialism, avoiding a disruptive socialist revolution. They were inspired by the gains Eastern Europe had made, with socialism giving them the basis to drive their economies and catch up with, and even overtake, the West.

The differences in Nkrumah and Nyerere���s politics become clearer when you compare who they saw as the economic agent and how this defined the problems of the nation state they sought to address.

Nkrumah sought to break away from the economic stranglehold of the West on Ghana, whereas Nyerere concentrated more on rural transformation based on a set of African values and thinking derived from his understanding of rural African ways of living. This is why Nkrumah recognized threats to the experiment more than Nyerere. In Nkrumah���s writing you find a certain clarity on the international political system that Nyerere never gained.

Amina Mama

Yes, I came away from your paper with the sense of Nkrumah as a visionary on the world stage and Nyerere taking a more localized, rural-based perspective. And I know that the kind of support they got internationally was different, and it���s clear Tanzania did not run into confrontation with the US the way Nkrumah did. So, I wonder, perhaps it���s that Nkrumah confronted US capitalism because it was globalizing in a way that Tanzania didn���t, so Americans didn���t fear Tanzania.

Nkrumah and Nyerere also had different gender politics, and this is embodied in the difference between Hannah Cudjoe and Bibi Titi Mohammed. Cudjoe disappeared from the archives of national history but was a major woman leader in Ghana under Nkrumah, responsible for national security, national propaganda for the whole nation. She was highly educated and politically competent, and it seems Nkrumah then leapt ahead of Tanzania in putting women in his government and on the world stage. Bibi Titi Mohammed from Tanzania is different; she reminds me of Gambo Sawaba from Nigeria���non-literate, popular, a brilliant performer, and neither ever learned to read or write. So, what was the difference in the gender politics of the men and of the societies in the two countries?

Akua O. Britwum

Something striking in both countries was the role ordinary women played in the whole nationalist struggle. In Tanzania, if ordinary women had not devoted time and resources to the nationalist struggle, it would have suffered, because they had the networks and they mobilized resources for nationalist movements. They could also appreciate the politics, they knew how to play their cards, and they had nothing to lose because of their place within the economic system. This is often missing in our historical account; that these nationalist movements, their lifeline depended on the actions of all these ordinary women like Bibi Titi and market traders in Ghana.

The difference between the two men was that Nkrumah wanted to reward these women and recognize their contribution, so he created space for them in political decision making, which didn���t happen in Tanzania. Women���s groups that had supported the nationalist struggles quickly disintegrated, so there was demobilization. More efforts were spent trying to gain the qualifications, including through Western education, to benefit from the opportunities independence presented.

So, in Ghana, the face of women after independence was women with a Western education. These educated women were asked to ���help their poorer sisters,��� the very women who had led the national struggle.

Part of a broader tendency in Nkrumah’s government was the clear division between what was considered elite, often people who felt they had a better Western education, and Nkrumah���s ���Verandah boys,��� activists with less formal education who held important positions in the government. There were efforts to provide adult education but this tended to be apolitical, focusing on literacy and numeracy.

Amina Mama

How interesting, and the only reason we know about women like these two figures that I picked out is because feminist scholars like yourself have actually excavated their role and brought them back into the national profile.

It���s hugely important you excavated these development plans, which didn���t fail because they were wrong; they were the first steps. And had it not been for global systemic forces and covert interventions, presumably those experiments would have continued, and they would have developed and grown. Instead, they were constantly interrupted, as you bring up quite clearly.

Today Africa is once again subjected to these global policies, which basically forbid African governments from investing in their people and their societies. The model has become more extractivist, more anti-people; Africans pursued independence for development understood as being people focused���to end ignorance, poverty, and disease, and bring public goods to the people from the wealth of their own nations. But, to date, we have not achieved economic independence, and women know this better than anybody else because of their double subjection, with the national government now collaborating with the global system in ways that are, to be frank, anti-African. Development is not what the state does anymore, so this work of revisiting what ���development��� is and re-reclaiming our right to develop.

All of that suggests that we���re thinking about freedom again, because half a century after we got flags and nation states and universities, we���re at a moment of stupendous failure, made even more evident by COVID-19. Looking at Ghana or Tanzania in the early post-independence period, what do you think we should reassess, and pick up again with new energy?

Akua O. Britwum

You���re right that it���s an important moment, it���s not just Africa questioning the system and what it has done to us, COVID has very clearly exposed the bankruptcy of capitalism. People are ready to listen to alternatives, but we also must recognize there���s a pushback and that this system is not going to go down gently, because the system is durable and adapts to mask its own contradictions.

In this moment we have to ask: How we can shape the discourse to highlight what our real problems are? A key difference between Ghana and Tanzania is the way critical scholarship developed in Tanzanian universities, something we didn���t have in Ghana. This was a result of the coup and the subsequent demonization of Nkrumah, so younger people in Tanzania perhaps have a bigger scope to frame their issues. In Ghana, people are realizing that what carries the country forward is the foundation Nkrumah laid.

A key consequence of structural adjustment is not just the collapsing of our economies, but the erosion of claims citizens could make on governments. With the retreating state, citizens have been finding ways to meet their needs, but now people are realizing there���s only so much we can do as individuals, the bigger system has to work, so how do we get it to work?

Amina Mama

There���s a question about what our education systems were doing between independence and now, and I think you���ve flagged it. The great University of Ghana was intended to be for the whole continent, but that shifted during military rule, whereas in Tanzania, while Dar es Salaam was a much smaller institution, it���s where Africa���s radicals took refuge. Some individuals we know left Ghana and went to Dar es Salaam during those years, to sustain their radical political and intellectual development, so we still have an underground of radical thinkers that���s alive and well, but they are not the people in power.

The African public university can no longer serve its society because everything has to be income-generating. It is a very sad state of affairs, professors now have to go out and raise foreign money to teach and to maintain graduate research capacity. That compromises African academic autonomy. Governments have a big role to play in making intellectual freedom a possibility for Africans.

This forces us to take on the question of autonomy. I���d say that feminist movements have become particularly adept at negotiating autonomy in order to push for change. What will it take to get African people as a whole out from under the foot of global imperialism in its current extractive, militarized, diseased, and frightening form? What can we do at home?

Akua O. Britwum

What we can do at home really is about how we frame peoples��� conditions. How do we get people to frame their conditions and what accounts for them? I think that this is what is missing. I think education and the political discourse around alternatives are really very important. In short, it needs to begin with activists and intellectuals���intellectuals not necessarily based in universities, but who are interested in real change. We need to create spaces, in both rural and urban communities, where we can hold these discussions.

People feel they cannot make demands on the state anymore. More and more, especially in urban communities, people are developing their own subcultures that do not require the state. I think people need to make demands on the state, and that if the state cannot deliver, ask what kind of state can we put in place to deliver? Maybe, I shouldn���t use the term state here because I know there are also questions about the state as a capitalist institution. Maybe I���m talking about a centralized system because it can���t be just individuals doing things for themselves.

Amina Mama

I share, and many Africans share, this desire not to throw the baby out with the bathwater���whatever good we���ve been able to do has been a result of strong states, so I think there���s a lot of new interest in the state. There���s nowhere you have a well distributed, equitable society without a state, so I hear you when you say we need to make demands on the state. Do you have any ideas about what those demands might be? We know the kinds of things that women, for example, have demanded of the state over many years���law reforms and policy reforms���and a lot has been achieved through that route, but it seems to me you���re proposing something a bit different.

Akua O. Britwum

Yes, the feminist space has really been exciting, and has offered opportunities in ways that other spaces have not. As we pursue greater demands to address women���s interests we soon come up against the bigger systems and structures, so the economic justice work of networks like NETRIGHT recognize that it���s not enough to pursue affirmative action policies or legal reforms, because if you don���t have adequate investment in those spaces then the legal reforms don���t work. If the state is unable to invest, it doesn���t matter how many women you put in parliament, it���s still the same patriarchal norms that you have to deal with. But it���s possible to take a critical look at development policies and the kinds of global policies we���re entering into.

Feminists also recognize that we have to work together at the continental level and at the global level. It is really within this feminist space, and the demands that we���re making on national, regional, and international institutions, that it is possible to talk about alternative discourses. And so, this is where I get excited. What I want is for all of us to invest our resources to ask the deeper questions that you cannot ask in the broader mainstream space.

Learn more about Akua O. Britwum���s research on Tanzania and Ghana���s early post-independence development plans:

December 9, 2020

The strange case of Portugal���s returnees

Still from Portuguese Returnees from Angola (1975).

The year is 1975, and the footage comes from the Portuguese Red Cross. The ambivalence is there from the start. Who, or maybe what, are these people? The clip title calls them ���returnees from Angola.��� At Lisbon airport, they descend the gangway of a US-operated civil airplane called ���Freedom.��� Clothes, sunglasses, hairstyles, and sideburns: no doubt, these are the 1970s. The plane carries the inscription ���holiday liner,��� but these people are not on vacation. A man clings tight to his transistor radio, a prized possession brought from far away Luanda. Inside the terminal, hundreds of returnees stand in groups, sit on their luggage, or camp on the floor. White people, black people, brown people. Men, women, children, all ages. We see them filing paperwork, we see volunteers handing them sandwiches and donated clothes, we see a message board through which those who have lost track of their loved ones try to reunite. For all we know, these people look like refugees. Or maybe they don���t?

Returnees or retornados is the term commonly assigned to more than half-a-million people, the vast majority of them white settlers from Angola and Mozambique, most of whom arrived in Lisbon during the course of 1975, the year that these colonies acquired their independence from Portugal. The returnees often hastily fled the colonies they had called home because they disapproved of the one party, black majority state after independence, and resented the threat to their racial and social privilege; because they dreaded the generalized violence of civil war and the breakdown of basic infrastructures and services in the newly independent states; because they feared specific threats to their property, livelihood, and personal safety; or because their lifeworld was waning before their eyes as everyone else from their communities left in what often resembled a fit of collective panic.

Challenged by this influx from the colonies at a time of extreme political instability and economic turmoil in Portugal, the authorities created the legal category of returnees for those migrants who held Portuguese citizenship and seemed unable to ���integrate��� by their own means into Portuguese society. Whoever qualified as a returnee before the law was entitled to the help of the newly created state agency, Institute for the Support of the Return of the Nationals (IARN). As the main character of an excellent 2011 novel by Dulce Maria Cardoso on the returnees states:

In almost every answer there was one word we had never heard before, the I.A.R.N., the I.A.R.N., the I.A.R.N. The I.A.R.N. had paid our air fares, the I.A.R.N. would put us up in hotels, the I.A.R.N. would pay for the transport to the hotels, the I.A.R.N. would give us food, the I.A.R.N. would give us money, the I.A.R.N. would help us, the I.A.R.N. would advise us, the I.A.R.N. would give us further information. I had never heard a single word repeated so many times, the I.A.R.N. seemed to be more important and generous than God.

The legal category ���returnee��� policed the access to this manna-from-welfare heaven, but the label also had a more symbolic dimension: calling those arriving from Angola and Mozambique ���returnees��� implied an orderly movement, and possibly a voluntary migration; it also suggested that they came back to a place where they naturally fit, to the core of a Portuguese nation that they had always been a part of. In this sense, the term was also meant to appeal to the solidarity of the resident population with the newcomers: in times of dire public finances, the government hoped to legitimize its considerable spending on behalf of these ���brothers��� from the nation���s (former) overseas territories.

Many migrants, however, rebutted the label attached to them. While they were happy to receive the aid offered by state bureaucracies and NGOs like the Portuguese Red Cross, they insisted that they were refugees (refugiados), not returnees. One in three of them, as they pointed out, had been born in Africa. Far from returning to Portugal, they were coming for the first time, and often did not feel welcome there. Most felt that they had not freely decided to leave, that their departure had been chaotic, that they had had no choice but to give up their prosperous and happy lives in the tropics. (At the time, they never publicly reflected on the fact that theirs was the happiness of a settler minority, and that prosperity was premised on the exploitation of the colonized.) Many were convinced they would return to their homelands one day, and many of them proudly identified as ���Angolans��� or ���Africans��� rather than as Portuguese. All in all, they claimed that they had been forcibly uprooted, and that now they were discriminated against and living precariously in the receiving society���in short, that they shared the predicaments we typically associate with the condition of the refugee.

Some of them wrote to the UNHCR, demanding the agency should help them as refugees. The UNHCR, however, declined. In 1976, High Commissioner Prince Aga Khan referred to the 1951 Refugee Convention, explaining that his mandate applied ���only to persons outside the country of their nationality,��� and that since ���the repatriated individuals, in their majority, hold Portuguese nationality, [they] do not fall under my mandate.��� The UNHCR thus supported the returnee label the Portuguese authorities had created, although high-ranking officials within the organization were in fact critical of this decision���in the transitory moment of decolonization, when the old imperial borders gave way to the new borders of African nation-states, it was not always easy to see who would count as a refugee even by the terms of the 1951 Convention.