Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 148

November 22, 2020

The price of contamination

Smelter, Zambia. Image credit MMJ via Flickr CC.

This post is part of our series “Climate Politricks.”

In 1907, the first industrial copper mine opened in ��lisabethville (now Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo). Since then, the Central African Copperbelt, which straddles the borders of contemporary Zambia and the DRC, has been one of the world���s most productive copper mining regions. Mining has caused severe air and water pollution, landscape change, and health problems: sulfur dioxide, lead, and mercury levels all exceed permissible international maxima; giant tailings dams and slagheaps, such as Terril de Lubumbashi and Black Mountain in Kitwe, mark the landscape; and pulmonary diseases and skin rashes are abnormally high among Copperbelt residents. Remarkably, protests against the environmental effects of mining on the Copperbelt have remained limited, until recently. A historical approach suggests that this relative lack of protest can be explained more by the political and economic structures, such as mine ownership or national policies, than by absolute pollution levels.

To attract and retain the labor force required for extracting valuable copper, both the British and Belgian colonial governments set up generous ���paternalistic��� welfare provisions. Mineworkers received not only high wages, but also education, healthcare provisions, and housing. After independence mine ownership changed, resulting in the eventual nationalization of mining companies in DRC under La G��n��rale des Carri��res et des Mines (G��camines) in 1966, and in Zambia under Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM) after 1968. Yet welfare services were further expanded into ���cradle to grave��� policies, including the provision of diapers for newborn babies. Morris Chimfutumba, who was born in Luanshya in 1930 and has lived on the Copperbelt all his life, told me in an interview that these policies influenced popular perceptions of pollution. When asked about how sulfur dioxide pollution (known as senta) developed on the Copperbelt, he responded:

In the 1960s and 1970s senta was already there���it was even worse than today because the chimneys could not capture the smoke. But you do not bite the hand that feeds you. How were we supposed to educate our children if the mines shut down?

So, was pollution simply accepted as a negative externality of copper mining? Were polluted water sources and chronic bronchitis the price for the Copperbelt���s Expectations of Modernity? The answer is complicated. If we stick to the example of sulfur dioxide pollution, knowledge of its effects was unmistakable by the 1950s. In neighborhoods located downwind from smelters or close to acid plants, such as Mufulira���s Kankoyo or Likasi���s Usines Chimiques de Shituru, vegetation was completely wiped out by independence. No trees, vegetables or grass could grow in these neighborhoods, and residents rightly attributed this to sulfurous smoke. Yet only after the privatization of the copper mines in the 1990s, which caused the neoliberal scaling down of welfare provisions and mass redundancies, did popular protests over sulfur dioxide pollution gain sway. When Mufulira���s district commissioner, an asthma patient, collapsed and died after inhaling sulfurous smoke in January 2014, mass protests followed. These protests cannot be explained by suddenly heightened pollution levels, as severe pollution had been ongoing for decades. Instead, protestors blamed Mopani Copper Mines���owned by the Swiss multinational Glencore���not only for pollution, but also for dilapidated housing, youth unemployment, and meagre healthcare.

Recent years have seen the acknowledgment of Copperbelt pollution in corporate environmental impact statements, media reporting, and even in international courts. In September 2016, the Zambian High Court ordered Glencore to pay ��30,000 in damages to the widower of Mufulira���s district commissioner, as sulfur dioxide emissions had exceeded legal limits. In April 2019 farmers in Chingola won the right to sue Konkola Copper Mines���a�� subsidiary of Vedanta, which has since been taken over by the Zambian government���in a UK court over pollution of their fields and water sources. In October 2020, the residents of Kabwe, the former lead mining town to the south-east of the Copperbelt (previously in the news as being one of the most contaminated places in Africa), sued mining giant Anglo American over the lead poisoning of thousands of children. How can these claims consider historical legacies of pollution and who should take responsibility for the contamination that has built up over decades?

Current legal cases are quick to blame foreign multinationals for lethal pollution. Protestors point out that these companies make extraordinary profits out of exploiting Copperbelt laborers and resources. But what about the role of colonial mining companies, or ZCCM and G��camines? How to account for the structures of exploitation and environmental destruction these historical actors established? Could their provision of wages, housing and welfare weigh up against the costs of environmental destruction? Historical research into the environmental legacies of resource extraction across Africa���from gold mining in South Africa to oil drilling in the Niger Delta���is urgently needed to better assess contemporary claims over pollution.

November 20, 2020

COVID-19 and cultural rites

Photo by David Clode on Unsplash

For the Luhya in Kenya, circumcision season habitually takes place between August and December. And even with the restrictions to movement and public gatherings, tradition has won over civil obedience. But though community effrontery and defiance of government edicts prevails, this cultural rite must still grapple with the reality of “how to circumcise boys from a meter away.” The series is curated by editorial board member, Wangui Kimari.

Just as the 9 o���clock curfew kicks in around the country, the crickets fall silent at the approach of stomping footsteps: it is the new witching hour at Sitikho Police Post in Bungoma.

Steel bells clink in rhythm to the monosyllabic sound of the whistle���blown repeatedly in accompaniment to the throaty chants of young women singing and men humming the new corona song: ���Beware the new corona disease���,��starts the soloist. ���Keep one meter away,�����the chorus roars back.

The band of up to 50 youths��crowd together with clubs raised above their heads, peering into each other���s faces in the dark as they shuffle in,��circling the police station up to three times before going back to the ceremonial homestead to regale waiting crowds with the new crop of ribald songs that are composed each circumcision year.

The police dare not come out. At the start of this year���s Bukusu circumcision season, which can only occur between August and December every even year, three assistant chiefs, two chiefs and a posse of administration police officers were repelled with sticks and stones from Mechimeru sub-location in Bungoma when they attempted to enforce the nationwide curfew and social distancing measures adopted to slow down the spread of COVID-19.

Messages about social distancing to slow down the spread of COVID-19 have reached every corner of the country, but they are far from lived experience.

Across the country,��police have killed at least 15 people��since the imposition of COVID-19 restrictions for failing to comply with regulations such as wearing face masks in public and being outdoors after curfew.

Circling the police station at the start of curfew is not only an act of defiance but also a dare to the base commander to step out of his house at the risk of certain forced genital cutting. The base commander at Sitikho Police Post is believed to come from a community widely known not to circumcise males.

Although��measures��to restrict movement have remained in place since March 27, the advent of the circumcision season has presented an impossible choice between tradition and civil obedience.

Tradition won, and the new crisis in the community is negotiating the impossibility of circumcising a boy from one meter away.

Bukusu circumcision���which mythology claims began with the first woman,��Sela,��operating on her husband, Mwambu, the first man���is more than the physical cutting of the foreskin. It is a public event invested with ritual and lore that form the core of individual and community identity.

Ancestors are spoken to in cajoling tones from early evening into the night, and animals are sacrificed before the operation at dawn. It is not a dry-eyed daylight affair, but it cannot also be privatized to a hospital surgery without attracting intolerable ridicule. The nightlong ringing of bells, the singing, and ribaldry prepare the candidate psychologically for surgery at dawn, performed in the anaesthetizing August cold after a visit to the river where the body is caked in mud before an icy walk in the nude to numb the pain and slow the flow of blood when cutting occurs back in the homestead.

Every two years, when the tassels of millet and maize begin to dry and the ears are full in readiness for harvest, boys from 12 years and older begin to smith bells from steel and tie stick holders onto them as well as the sisal strands that will create the visual spectacle in preparation for one of the most important rites of passage.

The bells are the calling card to the ceremony���the boy taking the initiative to travel to distant relatives to inform them that he is ready to face the knife. On the eve of the ritual, he visits his maternal uncle to acknowledge his joint heritage and is often feted with a bull���slaughtered and the rumen hang around his neck.

On the afternoon of August 3, the evocatively poignant��sioyaye, a guttural melody that strikes a mixture of trepidation and anxiety in the souls of boys turning into men,��rises to meet the road at Bukunjangabo on the outskirts of Webuye Town, as a group of youth and boys sing and chant as they escort a circumcision candidate back home. He is returning from his maternal uncle with the gift of a bullock.

Behind Lukhokho School, in Matete location of Kakamega County, another band of youths��are dancing and singing as they walk another circumcision candidate back to his home with his heifer.

The air is replete with social license. Men who have inherited the spirit of the circumciser get their knives down from the center pole of their huts and begin to hone them. Once, when I was about 10 years old and learning the esoteric magic of past, present, and future tenses, our English teacher heard the stirrings of the��sioyaye, the soulful, haunting melody that brings the circumcision candidate home from his uncle���or early in the morning from the river.

He bounded over the low wall where space had been left for a future window, and cut across the football field faster than any of his stripling pupils could follow. He reached the candidate���s homestead a kilometer away where the hired circumciser calmed him by letting him hold the knife in his quivering hands.

Once the circumciser���s spirit is upon someone, he is not responsible for what will happen next. And the same license often applies to others who may not themselves be circumcisers.

Local legend in Lugari rehashes the story of a senior manager at the large National Cereals and Produce Board depot who disregarded the counsel to take leave in August and was seized one Saturday as he attempted to rush the day���s collection from the store sales to the bank. A motley crowd collected around him, divested him of his clothing and took him to the river through the market to demonstrate that,��indeed, he was in need of surgery. A circumciser alerted by the singing of the��sioyaye��ran to the scene and performed the surgery in seconds.

Although the matter ended up in court, no conviction was entered, and this has emboldened this form of cultural bullying that sees many teachers and public servants who may not fit in with the culture take leave during the season of temporary madness.

Night after night, village and sub-county administrators have to pretend to be in deep sleep as youths roam the land singing ribald songs as they keep the circumcision candidates awake before the dawn reckoning. It is a fight the government has no stomach for.

During the months when movement into and out of Nairobi, Mombasa, Kilifi, and Mandera was limited by government edict, the Bukusu Council of Elders briefly considered whether or not to postpone this year���s circumcision activities, which would throw a spanner into the age set naming. After a little prevarication, it appeared that the rite would proceed because within the community, circumcising during an odd year can attract bad omens.

The only other time the idea of postponing circumcision was publicly broached was in 2008, in the aftermath of the 2007 election crisis in which over 1,000 people were killed. Some elders at the time felt that it would not be wise to launch a new generation of adults into the world with the stain of that year���s bloodshed, but they eventually overcame their fears.

The cultural pressure to conduct traditional circumcision among the Luyia communities living in Bungoma, Busia, Kakamega, Trans Nzoia and Vihiga counties generally, and the Bukusu in particular, had been obviated by a growing influence of churches which discourage heavy emphasis on traditional rites and sacrifices because they compete with Christian teaching. The church, however, is no ally of the government in the COVID-19 war. The restriction on congregations in places of worship has embittered church leaders and congregants in the region.

Public sympathy for health regulations to contain the spread of the coronavirus has also been severely eroded by restrictive orders around burial, another significant rite for the communities in western Kenya.

Funerals, which would previously be arranged for days and are important sites for performing public politics, are typically concluded in a day, with burials as early as 8 a.m. if the family is poor and cannot stand up to the bullying of the provincial administration and county officials. It is a source of great bitterness, resulting in families secretly exhuming the hurriedly buried dead in order to give them a befitting send-off.

At Kuywa market in Bungoma, a pastor of the Holiness Pentecostal Church was preaching to the bereaved, limited to just 15 as the government had ordered, when the Holy Spirit reportedly descended and threw official social distancing plans into disarray.

Schools remain closed across the country, with the youth roaming villages and hamlets. In public transport across the western Kenya region, the wearing of facemasks is mandatory but at markets, traders and buyers carry on without any of the new encumbrances.

Although the number of COVID-19 cases has reached 30,120 nationally, the five counties where the communities are in the grip of the circumcision dilemma have a combined total��infection��count of just 837 cases. Busia, the inland gateway to Uganda, has recorded the highest count of COVID-19 cases at 770, but this is believed to be on account of truckers crossing the border into Uganda. The neighboring counties of Bungoma and Kakamega, Trans Nzoia and Vihiga have recorded under 20 cases each.

For as long as the spirit of circumcision hangs in the air in the five counties, curfew remains impossible to observe and enforce.

November 19, 2020

Tupac is alive in Africa

"Treasure of Africa" mural in Cape Town. Image credit Jay Galvin via Flickr CC.

Tupac Shakur died on September 13, 1996, six days after a being ambushed in a drive-by shooting on Las Vegas Boulevard. Almost 25 years later, he is still very much alive in countries across Africa. Youth from Kenya, to Liberia, to Zimbabwe strut the streets in t-shirts bearing his image. There are also young Nigerians remixing his tracks on YouTube, and murals that have been painted as monuments to his memory in Sierra Leone and South Africa.

His legacy on the continent has probably been rendered most vividly in these last two countries. During Sierra Leone���s bloody conflict, for instance, Tupac t-shirts doubled as uniforms and his lyrics served as battle cries for young fighters trying to emulate the rebellious bravado of their idol; in South Africa, members of Cape Town���s estimated 130 gangs still revere Tupac as an embodiment of a powerful ���outlaw masculinity��� that valorizes crime, violence, incarceration, and wealth. It is men���especially poor young men���that most obviously connect to the masculine aggression that pulses through songs such as ���When We Ride On Our Enemies��� and ���Hit Em��� Up.���

But Tupac���s influence is not limited to men. A Cape Town-based study published in 2020 in the journal Ethnography found that young men and young women both identify with him. To them, Tupac is a symbol that being young, marginal, and black does not necessarily mean also being powerless. Listening to his songs, males and females alike find a shared refrain in survival and pride, echoing their personal defiance against racism, violence, and poverty in Tupac���s own voice.

Take 36-year-old Kelly (names have been changed ), for instance, who started going by the nickname ���Tupac��� at the age of 14. Like other study participants, she lives in a community where jobs are scant, government services are inadequate, and violence is common. Driven from her home by a physically abusive stepfather, Kelly had to find a way of surviving on streets ruled by the powerful 28s gang. ���I used to listen to Tupac���s songs, all his numbers. He was almost like a motivation for me,��� she said. ���I cut my hair. I cut it bald. And I used to wear my bandana like him [in the front], and a diamond in the nose. And that���s when the gangsters started calling me Tupac.���

Becoming Tupac provided Kelly with a lyrical script and a role model to help her deal with the dangers around her. It also won her respect from local gangsters. ���When they [the 28s] heard it was me, they thought don���t fuck with that girl, because that���s a badass bitch that one. It���s a real west-sider,��� recalled Kelly. ���If they see me, they go: west side, Tupac, or they gave me a westside [hand sign] ��� and when they passed at school and they fight, they won���t touch me.��� Eventually she joined the 28s too. Being in a gang can offer a young woman like Kelly protection against community violence and abuse, and can be a source of status and income.

Of course, joining a gang comes with its own risks. Kelly ended up in prison through her associations with gangster culture���just as her hero Tupac had. She ultimately spent much of her life jailed for various violent crimes, including murder. ���It put me in a fucked-up world. I thought [being Tupac] made me brave and famous, but it led me to a fucked-up world,��� she declared. When I met her, Kelly was living in abject poverty, addicted to drugs, and dying of AIDS. Tupac himself was incarcerated and died young, murdered in a retaliatory gang shooting for an assault he had participated in just hours before his death. It is a sad story that is repeated far too often in Cape Town, a place where gang wars kill hundreds of youngsters every year, in what has become Africa���s deadliest city.

That life mirrors art is a well-known axiom. But art is also subjective. Kelly���s story is just one out of 22 in the study. Each served as a testimonial to the ways that research participants were differently encouraged and inspired by Tupac. Watching his interviews, analyzing his rhymes, and moving to his tracks, helped put some on paths towards gangs, whereas it assisted others in finding alternative routes to school and work; others still gained strength to leave addictions, manage domestic and community problems, and find personal empowerment and strength in other areas of their lives.

Ultimately, how the artist and his art were interpreted depended very much on each person���s perspective; but always these were rendered as a tool formed in opposition to the anemic South African state, its racist societies, its brutal poling, and its exclusionary markets. This is precisely why Tupac is famous on the continent. He conjures ���an image of a defiant, proud antihero, and an inspiration for many of Africa���s young and alienated urbanites,��� as stated in a 2003 Woodrow Wilson Center report on young people in Africa.

Kelly literally turned herself into Tupac. Youth elsewhere are turning to him in their own ways. With every bar that rings into their headphones, and every beat that booms out over their speakers, young Africans are breathing life into Tupac���s memory, channeling his image and his music to be heard and seen in social spaces where they feel neither audible nor visible.

Tupac is alive and living in ���

"Treasure of Africa" mural in Cape Town. Image credit Jay Galvin via Flickr CC.

Tupac Shakur died on September 13, 1996, six days after a being ambushed in a drive-by shooting on Las Vegas Boulevard. Almost 25 years later, he is still very much alive in countries across Africa. Youth from Kenya, to Liberia, to Zimbabwe strut the streets in t-shirts bearing his image. There are also young Nigerians remixing his tracks on YouTube, and murals that have been painted as monuments to his memory in Sierra Leone and South Africa.

His legacy on the continent has probably been rendered most vividly in these last two countries. During Sierra Leone���s bloody conflict, for instance, Tupac t-shirts doubled as uniforms and his lyrics served as battle cries for young fighters trying to emulate the rebellious bravado of their idol; in South Africa, members of Cape Town���s estimated 130 gangs still revere Tupac as an embodiment of a powerful ���outlaw masculinity��� that valorizes crime, violence, incarceration, and wealth. It is men���especially poor young men���that most obviously connect to the masculine aggression that pulses through songs such as ���When We Ride On Our Enemies��� and ���Hit Em��� Up.���

But Tupac���s influence is not limited to men. A Cape Town-based study published in 2020 in the journal Ethnography found that young men and young women both identify with him. To them, Tupac is a symbol that being young, marginal, and black does not necessarily mean also being powerless. Listening to his songs, males and females alike find a shared refrain in survival and pride, echoing their personal defiance against racism, violence, and poverty in Tupac���s own voice.

Take 36-year-old Kelly (names have been changed ), for instance, who started going by the nickname ���Tupac��� at the age of 14. Like other study participants, she lives in a community where jobs are scant, government services are inadequate, and violence is common. Driven from her home by a physically abusive stepfather, Kelly had to find a way of surviving on streets ruled by the powerful 28s gang. ���I used to listen to Tupac���s songs, all his numbers. He was almost like a motivation for me,��� she said. ���I cut my hair. I cut it bald. And I used to wear my bandana like him [in the front], and a diamond in the nose. And that���s when the gangsters started calling me Tupac.���

Becoming Tupac provided Kelly with a lyrical script and a role model to help her deal with the dangers around her. It also won her respect from local gangsters. ���When they [the 28s] heard it was me, they thought don���t fuck with that girl, because that���s a badass bitch that one. It���s a real west-sider,��� recalled Kelly. ���If they see me, they go: west side, Tupac, or they gave me a westside [hand sign] ��� and when they passed at school and they fight, they won���t touch me.��� Eventually she joined the 28s too. Being in a gang can offer a young woman like Kelly protection against community violence and abuse, and can be a source of status and income.

Of course, joining a gang comes with its own risks. Kelly ended up in prison through her associations with gangster culture���just as her hero Tupac had. She ultimately spent much of her life jailed for various violent crimes, including murder. ���It put me in a fucked-up world. I thought [being Tupac] made me brave and famous, but it led me to a fucked-up world,��� she declared. When I met her, Kelly was living in abject poverty, addicted to drugs, and dying of AIDS. Tupac himself was incarcerated and died young, murdered in a retaliatory gang shooting for an assault he had participated in just hours before his death. It is a sad story that is repeated far too often in Cape Town, a place where gang wars kill hundreds of youngsters every year, in what has become Africa���s deadliest city.

That life mirrors art is a well-known axiom. But art is also subjective. Kelly���s story is just one out of 22 in the study. Each served as a testimonial to the ways that research participants were differently encouraged and inspired by Tupac. Watching his interviews, analyzing his rhymes, and moving to his tracks, helped put some on paths towards gangs, whereas it assisted others in finding alternative routes to school and work; others still gained strength to leave addictions, manage domestic and community problems, and find personal empowerment and strength in other areas of their lives.

Ultimately, how the artist and his art were interpreted depended very much on each person���s perspective; but always these were rendered as a tool formed in opposition to the anemic South African state, its racist societies, its brutal poling, and its exclusionary markets. This is precisely why Tupac is famous on the continent. He conjures ���an image of a defiant, proud antihero, and an inspiration for many of Africa���s young and alienated urbanites,��� as stated in a 2003 Woodrow Wilson Center report on young people in Africa.

Kelly literally turned herself into Tupac. Youth elsewhere are turning to him in their own ways. With every bar that rings into their headphones, and every beat that booms out over their speakers, young Africans are breathing life into Tupac���s memory, channeling his image and his music to be heard and seen in social spaces where they feel neither audible nor visible.

Ethiopia’s war of narratives

Photo by Gift Habeshaw on Unsplash.

We are re-publishing this piece from the Addis Standard which gives important history and context to current events in Ethiopia. However, please note that the piece was published on September 30. While it was updated by the authors over the past month, the conflict in Ethiopia has now accelerated to a civil war. We plan to provide more up-to-date coverage. Meanwhile, we recommend this statement by a group of scholars and researchers from the Horn of Africa.

There is an enduring disunity among Ethiopian elites regarding the country���s history and future. Informed by its long, and contentious multi-ethnic history, and fueled by recent shifts in the political landscape in the country, a war of narratives has been reignited. The narrative war is fought between adherents of what we have termed ���Pan-Ethiopianists��� and ���Ethno-nationalists.��� The spillover effect of this increasingly toxic debate has had a negative impact on the lives of everyday Ethiopians and continues to destabilize the country. Indeed, narratives surrounding ethnic identities and ethnic politics in Ethiopia is the one thing that demands the most attention. As it stands today, the way and environment in which the debate is occurring, and the actors involved in it indicates we may be approaching a threshold that cannot be uncrossed.

How the Ethiopian state evolved

Nation-building is a contested process of narrative construction. In his book, Imagined Communities, political scientist Benedict Anderson reminds us that nations are ���imagined political communities.��� Common to all political communities is a set of beliefs in unifying narratives about community special characteristics. These narratives provide explanations to the participating individuals and their leaders about what makes their community unique, especially when compared to others. Nation-building in the Ethiopian context follows a similar pattern.

Faced with the burden of justifying maintenance of the Ethiopian state and their place at the top, Ethiopian rulers of the past relied on religious texts and edicts of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Written in the 14th century, the Kibre Negest, or ���Glory of the Kings,��� provided detailed accounts of the lineage of the Solomonic dynasty���the former ruling dynasty of the Ethiopian Empire���according to which Ethiopia���s rulers were descendants of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. It told the story of Ethiopia and Ethiopians as God���s people, a chosen people.

This narrative of Ethiopia as a chosen place endures to this day. It was in display when many Ethiopians woke up on October 24, 2020 and learned that US President Donald Trump had suggested ���[Egypt] will end up blowing up the [Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD)] dam.��� Many Ethiopian citizens and politicians responded with the assertion that Ethiopia will prevail, not least of which because it has God on its side. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed���s office released a statement that echoed the same sentiment.

Similarly, the 12th century text Fitiha Negest, or ���Laws of the Kings,��� served as the country���s oldest traditional legal code. The Fitiha Negest insisted that kings must receive obedience and reverence. It justified the Kings��� power using scripture, specifically the words of Moses in Deuteronomy 17:15:

Thou shalt in any wise set him king over thee, whom the Lord thy God shall choose: one from among thy brethren shalt thou set king over thee: thou mayest not set a stranger over thee, which is not thy brother.

Ethiopia���s rulers used these texts to justify the state���s existence and their own power. But more importantly, as much as Americans take the Declaration of Independence as their founding moment, the Kebre Negest provided a similar ���origins��� story, albeit a contested one, while Fitiha Negest served as a constitution of sorts by laying out a minimal set of rules that bound the Kings and their subjects. As such, the Kebre Negest and the Fitiha Negest could arguably be taken as the most important founding texts of the Ethiopian state.

The 1700s witnessed the emergence of a new political structure where disparate noblemen usurped power away from emperors of the Solomonic dynasty and began ruling over their own regions, a period known among Ethiopian historians as Zemene Mesafint, or Age of the Princes, named after the Book of Judges. In 1855, Emperor Tewodros II, born Kassa Hailu, rose to the throne after defeating regional noblemen. He recognized the need for a newer narrative that was closely aligned to his vision of Ethiopia as a modern, forward thinking nation. In line with that vision, his first step was to separate church and state, shift its narrative and establish the state on a more secular foundation. To do so, he needed better educated Ethiopians, and thus began an elite-led nation building process. His efforts however did not bear fruit due to fierce internal opposition driven largely by disgruntled clergy, who, fearful of losing their own privilege and power, were unappreciative of his radical ideas.

Subsequent rulers of Ethiopia mended the ���glitch��� and followed the path that almost was dismantled by Emperor Tewodros II, and, as a result, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church remained inseparable from the Ethiopian state, and, with that, the state narrative. That, however, changed with Emperor Menelik II assuming the throne in 1889. Although historical Ethiopia dates back to millennia, Emperor Menelik is widely considered as an architect of the modern Ethiopian state. His epic defeat of Italian colonial power at the Battle of Adwa added another, if not stronger, element to the myth of God���s-chosen-people identity to Ethiopians and the Ethiopian state. As the Ethiopian historian Bahru Zewde recounts in his book, Pioneers of Change, Menelik, eager to modernize Ethiopia, sent Ethiopians to Europe and the US for higher education. Unlike the church-educated elites that preceded them, these early Western-educated Ethiopians broke with tradition and became critics of the state. It may be argued as such that Emperor Menelik could be credited with spearheading the creation of a new intellectual-elite class and with bringing the same to the center of state politics. With that he laid the groundwork for the creation of a new elite class that would later challenge the very essence of Ethiopia as a nation state.

Walleligne and the birth of ethno-nationalism

When Emperor Haile Selassie rose to the throne in 1930, he was acutely aware of the shortage of educated Ethiopians to build Ethiopia���s nascent civil service and bureaucracy. In order to fill in this gap, like his predecessor, he sent many Ethiopians to Europe and the US for higher education that in the words of historian Jon Abbink produced ���a generation of daring, innovative intellectual leaders and thinkers.��� However, sadly many of these intellectuals were annihilated by the Italian colonial power in the late 1930s. This loss of its brightest left post-war Ethiopia with deep psychological scars and decades of stagnation, devoid of social and political change. With the founding of the University College of Addis Ababa in 1950, the future Haile Selassie University (now, Addis Ababa University), Emperor Haile Selassie���s dream of producing educated Ethiopians en masse finally came true.

The 1960���s was when the role of Ethiopian intellectuals in the country���s politics probably experienced its most consequential phase. Starting in the 1960���s, with the backdrop of broader social unrest, university students started to oppose Haile Selassie���s single-man authoritarian rule and the oppressive socio-economic and cultural structures within which the students said the imperial government and its predecessors functioned. They demanded rights and freedom. It was until a more radical wing of the movement, concurrent with the more mundane demand for reform, started to question the equating of the Ethiopian state with the nation. Compared to the reformist intellectuals of the previous generation, Ethiopia���s newly minted intellectuals displayed impatience and lacked foresight in their calls for radical social and political reform. Jon Abbink might not be far from the truth when he observed these intellectuals��� ���wholesale adoption of unmediated Western ideologies and abandonment of Ethiopian values��� had had ���quite disastrous consequences.���

���On the Question of Nationalities in Ethiopia,��� an influential short essay written by Walleligne Mekonnen���who at the time was a second-year political science student at the university, and who was later was shot and killed along with fellow activists while attempting to hijack an Ethiopian Airlines flight���became a founding text of the radical wing of the student movement. In his essay, Walleligne argued that ���Ethiopia is not really a nation��� but rather ���made up of a dozen nationalities with their own languages, ways of dressing, history, social organization and territorial entity.��� However, this reality, according to him, was suppressed by the ruling class. Instead, a ���fake Ethiopian nationalism��� that is based on the linguistic and cultural superiority of the Amhara and, to a certain extent, the Amhara-Tigre, was imposed on the other peoples of Ethiopia, resulting in asymmetrical relations among the ���nations��� of Ethiopia. Therefore, according to Walleligne, the Ethiopian state came to be through the linguistic and cultural assimilation of the peoples of the wider South by the North���the Amhara and their junior-partner-in-assimilation, the Tigre. And, that this project of constructing Ethiopia was aided by the trinity of (the Amharic) language, (Amhara-Tigre) culture and religion (the Ethiopian Orthodox Church). He was, of course, echoing arguments that Joseph Stalin, Rosa Luxemburg and others made about nations, nationalism, and self-determination. (Stalin, for example, lays out his thesis in Marxism and the National Question, as does Luxemburg in The Right of Nations to Self-Determination.)

Walleligne thus called for the dismantling and replacement of this ���fake [Ethiopian] nationalism��� with a ���genuine Nationalist Socialist State��� that he argued could only be achieved ���through violence [and,] through revolutionary armed struggle.��� To be sure, Walleligne did not see ���succession��� as an end in and of itself; nonetheless, he propagated it as a means to building the future egalitarian Ethiopian state, with the caveat that such succession should be rooted in and guided by ���progressivism��� and ���Socialist internationalism.��� He closed his essay with what may be considered prophetic:

A regime [Haile Selassie���s government] like ours harassed from corners is bound to collapse in a relatively short period of time. But when the degree of consciousness of the various nationalities is at different levels, it is not only the right, but the duty, of the most conscious nationality to first liberate itself and then assist in the struggle for total liberation.

Haile Selassie���s government did collapse in 1974.

The constitutionalizing of ethno-nationalism

The movement that Walleligne imagined, spearheaded by the intelligentsia as it were, was hijacked by the Dergue���a collective of disgruntled low-ranking military officers in the imperial army���that not only succeeded in overthrowing Haile Selassie���s government, but also in ruling Ethiopia with an iron-fist for the next 17 years. But the political and armed struggle for ���liberation��� continued. It was in this atmosphere of radicalization of the intellectual-elite class that discourses like ���liberation��� and the ���oppressor-oppressed��� took hold in the Ethiopian body politic and a plethora of liberation fronts mushroomed or revived: the Eritrean Peoples��� Liberation Front (EPLF, 1962)���that succeeded in seceding Eritrea from Ethiopia in 1991���the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF, 1966), and the Tigray People���s Liberation Front (TPLF, 1975) to name but the most important ones. The Dergue���s 17 years in power was marred by the bloodiest times in Ethiopian modern history: the Red Terror, a border war with Somalia (1977-1978) and, more importantly, the protracted civil wars with TPLF, EPLF and OLF.

After 17 years of armed struggle, the Ethiopian Peoples��� Revolutionary Front (EPRDF) defeated the Dergue and controlled Ethiopian state power in 1991. The EPRDF was a coalition composed of the TPLF, The Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM), the Oromo Peoples Democratic Organization (OPDO) and the Southern Ethiopia Peoples Democratic Front (SEPDF). It should, however, be noted that it was only with victory in sight against the Dergue and a desire to expand its sphere of influence beyond Tigray, that the TPLF formed the EPRDF in 1988. Otherwise, the actual power holder within the coalition remained TPLF. Consequently, the EPRDF introduced the 1995 constitution. Adopted in the immediate context of the post-Cold War, in a way that reflects the politics of constitutionalism and especially the shrewdness and pragmatism of the man behind it, Meles Zenawi, the constitution was a compromise between TPLF���s deep-rooted Marxist-Leninist ideological moorings and the post-Cold War euphoric triumphalism of liberal constitutionalism and human rights. So much so that the constitution declares the inviolability and alienability of human rights and freedoms emanating from the nature of mankind. However, as his building a de facto one-party state would later reveal, this was a move that seems to have been motivated more by placating the West than a genuine desire on the part of Zenawi���s EPRDF to champion the causes of human rights and democratic values.

The constitution divided Ethiopia into nine ethnic states that���with the exception of what is called the Southern Nations and Nationalities Regional State���are based on the ethnic identities of residents of those states. Most importantly, the constitution grants the ���Nations, Nationalities and Peoples��� within those states the unconditional ���right to self-determination, including secession.��� In other words, rather than with a people, sovereignty resides in a plurality of peoples of Ethiopia. It is these peoples that came together to form Ethiopia and they are the custodians of Ethiopia, from which they have the absolute right to secede if they so wish. That way, the constitution replaced the age-old notion of Ethiopia as a nation with an Ethiopia as a ���nation of nations.��� Walleligne predicted this almost a quarter of a century earlier: ���What are the Ethiopian people composed of? I stress the word peoples because sociologically speaking at this stage Ethiopia is not really a nation.���

From then on ethnicity became a determinant factor and dominant political currency in Ethiopian politics, bringing with it, in the words of the late sociologist Donald Levine (who taught at the University of Chicago and became a key figure in Ethiopian Studies), an ���epidemic of ethnic and regional hostilities.��� In addition to changing the way the country organized itself politically, EPRDF also sought to reframe the very foundation of what it means to be an Ethiopian and how Ethiopia itself came to be. Not unexpectedly, EPRDF targeted schools and educational institutions in particular as spaces where new narratives of Ethiopian history could be inculcated, so much so that Ethiopian universities became flashpoints of ethnic conflicts among students. Walleligne���s abstract and���as he himself admitted in his writing���incomplete idea found a home in the curriculum. With this entrenchment of a ���new��� history of Ethiopia and a generation educated in the new curriculum and the alienation of ���pan-Ethiopianism��� from the Ethiopian body politic, it seemed that the ���old Ethiopia��� had died and been buried. But, as the 2005 Ethiopian election showed, a pan-Ethiopian party called the Coalition for Unity and Democracy (CUD) almost clinched power in major cities and rural areas if it had not been suppressed and finally expelled from Ethiopian political landscape. In fact, it was that election that gave the close to two decades-long ethnic politics championed by Meles Zenawi, a real challenge and, more importantly, sowed the earliest seeds of the revival of pan-Ethiopian politics.

Abiy Ahmed and the re-emergence of pan-Ethiopianism?

Zenawi���the ex-guerrilla fighter who, as a prime minister, was reported to have made authoritarianism respectable���died in a Belgian hospital in 2012. Although political pundits thought that in his absence Ethiopia would plunge into crisis immediately, his successors managed to stave off social unrest until protest rallies started to emerge in the Oromia region following the unveiling of the so-called Addis Ababa Master Plan (a plan to expand the federal capital, mostly into Oromia) in April 2014. Months of sustained protests resulted in hundreds of deaths and even more people being imprisoned. However, the draconian measures did little to slow the protests. The EPRDF government eventually backed off from its aggressive actions against protestors and shelved its ambitious master plan, but it was too late. The protest had picked up steam and expanded to several other regions, including the Amhara region. Protestors demanded rights, representation, and economic justice. Tellingly, these protests erupted less than a year after EPRDF claimed to have won 100% of the 2015 election and only months after US President Obama praised the government as being ���democratically elected.���

The TPLF-led EPRDF government could not sustain its political power. In the backdrop of a fierce intra-party scuffle, in April 2018, Abiy Ahmed, an ethnic Oromo and member of the OPDO, ascended to power. With his promise of leading Ethiopia through transition to democracy, Abiy immediately began introducing a plethora of reforms, including releasing political prisoners, inviting home all opposition parties, and appointing some prominent public figures to key positions within his government. These and many other earlier reforms won him almost universal support from Ethiopians and the international community. In 2019 he won the Nobel Peace Prize for brokering a peace-deal with neighboring Eritrea, ending a two-decades long stalemate, following the 1998 border war between the two countries that claimed more than a hundred thousand lives.

Despite the indisputably positive changes he introduced and results achieved, Abiy���s Ethiopia also saw its most turbulent years in recent Ethiopian history, including internal displacements, violence that claimed the lives of hundreds���high-profile assassinations, including an attempted assassination on the premier himself, targeted ethnic killings, and ongoing violence perpetrated by a splinter military wing of the OLF in western Oromia region. Abiy���s decision to indefinitely postpone the August general election due to COVID-19 has further destabilized the country and put in tatters his promise of transitioning Ethiopia to democracy. There also is the ongoing tension with the TPLF that governs the Tigray region���that recently held its own regional election in defiance of the central government���s ban on all elections due to the pandemic. As a result, the Ethiopian parliament voted to cut ties with Tigray region leaders, which has the potential to erupt into a full-blown war with the federal government. Further complicating Abiy���s agenda of stabilizing the East African nation is the tension with Egypt in relation to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (the GERD) and broader geopolitical issues.

It was amid this ongoing turmoil Abiy established the Prosperity Party at the end of 2019, which brought together three of the four ethnic-based parties that constituted the EPRDF coalition and other smaller parties, considered within party circles as ���allies��� to the EPRDF. Based on his vision of national unity among Ethiopians that he calls medemer, which literally means ���coming together,��� this re-branding of EPRDF was meant to stave off the ethnically divisive politics and address ethnically motivated conflicts that engulfed the country during EPRDF���s 27 years in power. This seemingly mundane action, however, did not sit well with everyone and it brought to the surface an issue dormant for the last 25 years in the Ethiopian formal political scene, namely: how to historicize Ethiopia. There is now an all-out war of narratives among Ethiopian elites on the history of Ethiopia.

This narrative war is fought between adherents of what we have termed ���Pan-Ethiopianism��� and ���Ethno-nationalism.��� The ethno-nationalist camp takes Walleligne���s thesis as accurate representation of Ethiopia as a nation of nations. As we have noted, in mainstream Ethiopian history, Emperor Menelik is considered the architect of the modern Ethiopian state. He is especially credited with expanding the Ethiopian empire to the south from his northern stronghold of Shoa. To the outside world and to Ethiopians alike, his epic victory over the Italian colonial force in the Battle of Adwa is widely celebrated as a key moment in Black anticolonial consciousness. In stark contrast to this picture, in the ethno-nationalist discourse, Emperor Menelik figures as the archenemy. To the ethno-nationalists Menelik���s supposedly mundane ���state-building��� endeavors were marked by violence, forced assimilation and suppression of cultures of peoples of the South, especially the Oromo. Echoing Walleligne���s thesis, they insist that rather than a nation built on the consent of the ���nations, nationalities and peoples��� of Ethiopia, Ethiopia is imposed on the wider South through conquest, violence and assimilation by Ethiopian rulers of Amhara, and to a certain extent, Tigre extraction. In their view, rather than an inclusive multicultural state, Ethiopia is made in the image of the Amhara and the Tigre.

Quite to the contrary, those in the Pan-Ethiopianist camp embrace the historical Ethiopia and adhere to the idea of Ethiopia as a nation-state. While not ruling out the presence of violence, they reject the ���empire thesis��� of the ethno-nationalists and hold that Emperor Menelik was just engaging in state-building when he conquered and brought the wider South under his Imperial rulership. In the Pan-Ethiopianist narrative of Ethiopia, the supposed assimilationist and imperialist expansion of Emperor Menelik and his predecessors to the South is a normal historical process inherent to state building. There are also some within the Pan-Ethiopianist camp that insist that Emperor Menelik did not actually conquer and control ���new��� territories, but only ���re-claimed��� territories that hitherto were parts of the historical Ethiopia. There are still those in this camp that argue that it is in the nature of an empire to conquer peoples and rule over lands, and hence there is nothing anomalous about Emperor Menelik���s deeds.

Not surprisingly, many in the Pan-Ethiopianist camp saw, at least in the beginning, Abiy���s formation of the Prosperity Party as a move in the right direction with a potential to dismantle the current ethnic-federalism���that adherents of this camp hold is the root cause of the cycles of ethnic conflicts and other problems that the country faces���and eventually realize a unified Ethiopia, albeit federalist. Quite to the contrary, the move did not sit well with the ethno-nationalist camp, the TPLF in particular openly opposing this merger as ���illegal��� on the grounds that all constituent parties of the EPRDF should have consented to the dissolution of EPRDF and the merger. The Oromo activists see in this merger and Abiy���s other reform agenda a return to the old Ethiopia, in which they argue Oromos were culturally and linguistically alienated by the Amhara-Tigre elites that in the past had a monopoly on state power.

Social media and narratives of hate

The elites��� reach and impact has expanded as the means of information sharing and consumption has expanded. It is no more the traditional intellectual-elite class that engages in the production and dissemination of information that advances knowledge. Unlike the closely-knit intellectual class of earlier times, the debate now has a diverse body of actors: activists, political party operatives, and, as oxymoronic as it sounds, intellectual activists. The elites with the loudest voices use low-trust and high-reach communication mediums like Facebook, Twitter, and other social media to peddle their own facts and pursue their own agenda. Social media as it exists today rewards absolute claims, purity, good and evil binaries, and unequivocal declarations of truth that leave little room for compassion, reasoning, careful interpretation, and nuance. Fueled by algorithms that favor combustible content, social media companies orchestrate human interaction that lead individuals to maintain extreme positions and be adversarial towards one another.

The emerging Ethiopian elites in both camps have harnessed social media in ways that have yielded extraordinary influence and power over political discourse that directly and indirectly affects the lives of everyday Ethiopians. They recognize their charisma is more significant to their audience than the contents of their speech or the quality of their argument. Name calling and ad hominem attacks are their currency and they invoke current and historical grievances, and narratives of superiority, to stoke fear and anger. Unfortunately, the narratives these elites broadcast are not without consequences. There is a correlation between recent violence in Ethiopia and the supposed adherents of these narratives.

Nothing makes the dangers of the deep division between the two camps as the murder of the renowned Oromo singer, Hachalu Hundesa in June 2020. This incident has clearly shown their tendency to see and interpret any and every incident or issue in ways that support their respective narratives. Unfortunately, as is quite common in the post-truth social media age we live in, it is as though elites in each camp use different truth-filters, no matter what facts on the ground dictate. So much so that, immediately after the news of Hachalu���s death surfaced, elites in each camp took to social media and, with no evidence at their disposal, started to speculate who might have shot and killed the singer and began pointing fingers at each other. In the ethno-nationalist camp, a conspiracy started to circulate that claimed the killing was orchestrated and carried out by ���neftegna��� and statements like ���They killed our hero��� reverberated around social media, followed by wide-spread Oromo protests in Ethiopia, Europe, and North America. On the other hand, in what appears to be due to Hachalu���s pro-Oromo nationalistic political views, in the Pan-Ethiopianist camp there was either a deafening silence, or some suggesting that the killing was a result of intra power-struggle among the Oromo elite politicians who just ���sacrificed��� Hachalu for their own politically calculated ends. Amidst the confusion and unsubstantiated claims floating around���with even some media outlets broadcasting hate-filled messages���violence ��erupted in the Oromia region claiming the lives of more than 200 individuals, the displacement of thousands, and property damage. The killings were reported to be gruesome and targeted.

If anyone in either camp is insensitive enough to bring havoc to Ethiopia, or even worse, to sacrifice precious human lives in pursuit of political ends or to prove a particular narrative of Ethiopia, then the debate is not so much about liberation and freedom as it is about ideology or some other ends. As Edward Said chastises us:

the standards of truth about human misery and oppression [are] to be held despite the individual intellectual���s party affiliation, national background, and primeval loyalties. Nothing disfigures the intellectual���s public performances as much as trimming, careful silence, patriotic bluster, and retrospective and self-dramatizing apostasy.

We shouldn���t also lose sight of the fact that, while not denying that there are genuinely invested individuals and groups of actors in each camp, there are still many in this ���war��� owing to other factors that have little or nothing to do with a genuine concern for Ethiopia and everyday Ethiopians. The harsh truth is that this is not just a debate about history, identity, or self-governance, but more so about elites��� drive for resource monopolization, the prestige that comes with power, and other factors external to the debate.

Abiy���s government, like the EPRDF before it, is attempting to limit internet access, especially to social media, to quell recent unrest. The government���s desperate act to avoid future incidents like these are understandable. Expanded internet access to all, in theory, at least, is a positive development in the right hands. And it would be misguided to argue that the broadening of access to free speech that has been made possible through social media is wrong or detrimental. The detriment, actually, is with the unchecked nature of social media. As well, the absence of meaningful fact checking and understanding of local knowledge among social media companies make it possible for misinformation to spread easily.

Whither Ethiopia? The way forward

As we noted initially, nation-building is a contested process and the path to consensus is neither linear nor guaranteed. Consensus is especially difficult to achieve in a nation as ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse as Ethiopia. This has become a singularly arduous task especially now that a generation of Ethiopians who have grown up under the EPRDF are increasingly alienated from actual inter-ethnic-lived experiences of Ethiopians of present and past generations. It is also naive to expect the debate to remain even-tempered. Emotions can run high as communities attempt to reconcile their ethnic identity and group status as they negotiate the meaning of their shared history with others. However, prerequisites to making meaningful progress are highly credible communication mediums, shared facts, and shared goals. At the moment, the opposite appears to be true.

There is a glaring absence of willingness on both sides to engage in reasoned debates, leaving no room to explore the authenticity and truthfulness of alternative narratives. It is not an accident that much of the narrative war is being fought on social media. Social media is fertile ground for having one sided debate. For the elites, it is a place where captured attention can be exchanged for dollars and because of it, careful analysis, and nuance���arguably the most important characteristics of intellectuals���are disincentivized.

Even if we disagree on where we started and how we got here, we could at least agree on where we are heading. Denialism, lack of empathy, and cancel-culture are the last traits we should carry into this debate, not only because people���s lives are at stake, but also the future of Ethiopia as a state. Good faith debate based on shared facts and shared goals are required if the historical Ethiopia is to survive another century.

November 18, 2020

From the Niger to the Nile

King Ahmadou 1888. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

This post is part of our series, ���Histories of Refuge,��� made up of essays from participants in the Rethinking Refuge Workshop. It is edited by historian Madina Thiam.

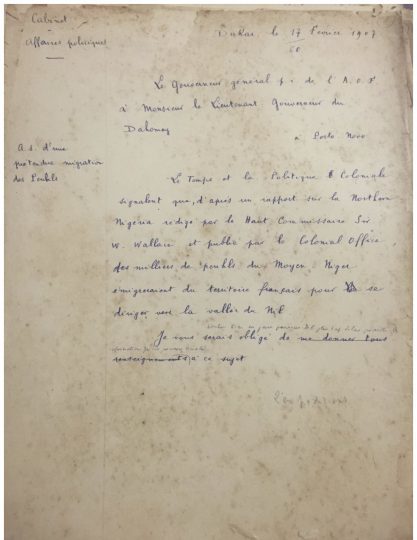

On February 17, 1907, a brief note went out of the Dakar office of the Governor-General of French West Africa, addressed to subordinates. The governor had learned through French newspapers that:

According to a report on Northern Nigeria written by High Commissioner Sir W. Wallace, and published by the Colonial Office, thousands of Fulanis from the Middle Niger [central Mali] might be migrating from the French territory and heading towards the Nile valley ��� I would be grateful for any further information on this issue.

This note reveals the anxieties of both French and British administrations in the early years of colonial rule in Africa, as they faced a set of population movements that trumped the logic of their imperial borders.

The eastwards travels of West Africans toward the Nile valley largely predated European colonization. Among West African Muslims, this phenomenon was rooted in the old tradition of pilgrimage to the holy cities of Islam, Mecca, and Medina, in the Hejaz region of Arabia. Scholars Umar al-Naqar and Chanfi Ahmed have written about how numerous West African pilgrims reached these destinations by crossing the Sahel and Sahara from west to east, via a route called the ���ar��q al-S��d��n (Sudan Road). The road started in Shinqit (Mauritania), Timbuktu or Jenne (Mali), and stretched all the way to the Red Sea ports of Sawakin (Sudan) or Masawa (Eritrea), via Hausaland, Chad, and Darfur. Pilgrims would then sail to the Hejaz.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, the flow of travelers on the Sudan Road grew to include people rejecting European colonial rule. Key to these migrations were the Islamic notion of hijrah (emigration) and the figure of the mahdi, a redeemer set to appear shortly before the end of times. Hijrah is the doctrine whereby Muslims, should they find themselves in an environment hostile to their faith, should leave. In the newly-created French Soudan colony (Mali), members of communities such as the Gabero or the Kel el Suq migrated east, settling along the Sudan Road or traveling all the way to the Hejaz.

Another documented instance of hijrah was that of a group of defeated Fuutanke (a Fulani-speaking community from the Senegal River valley) in the French Soudan, who fled east, settling in Sokoto, Sudan, or Mecca. In the 19th century, Fuutanke scholar and warrior El Hajj Umar Tal led a jihad, conquering and occupying parts of present-day Senegal, Guinea, and Mali, while fighting French encroachment in the region. Tal died in 1864, but by the late 1890s the French army defeated all his successors, including his son Ahmadu, and dismantled his empire. Some of Ahmadu���s companions undertook hijrah, leaving the Niger valley to head toward the Nile, as a 1906 note (in the Archives Nationales du S��n��gal) from a French colonial official in Fort-Lamy (present-day N���Djam��na, Chad) attests:

A���madu���s Tukulor [Fuutanke]���the last remnants of these hardliners who never accepted to submit to our domination���the former Sultan of Sokoto���s supporters, and the malcontents from Northern Nigeria, are going away towards the East, with no hope of ever returning ��� It will be up to the Anglo-Egyptian authorities to watch these newcomers, should they settle on the White Nile.

The Anglo-Egyptian colonial authorities in Sudan indeed had reasons to worry. A few years earlier, another series of events had propelled West African migrations on the Sudan Road, and seriously threatened their regime.

Draft note from the governor-general of French West Africa about the eastbound migrations of Fulanis, 1907. Archives Nationales du S��n��gal.

Draft note from the governor-general of French West Africa about the eastbound migrations of Fulanis, 1907. Archives Nationales du S��n��gal.According to early Islamic prophecies, the world was set to end in the 13th century of the Islamic calendar (1786-1883 AD). The announced end of times was to be heralded by the appearance of a mahdi.

Incidentally, in 1881, an uprising broke out in Sudan, then under Ottoman-Egyptian and British rule. A man by the name of Muhammad Ahmad successfully gathered an army, defeated Ottoman-Egyptian troops, and led a successful siege of Khartoum, killing former British Governor-General Charles Gordon. Proclaiming to be the mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad established a new State, the Sudanese Mahdiyya (1881-1898).

These events further fueled West African migrations eastward along the Sudan Road. The Mahdiyya attracted a number of West African migrants to its ranks, who largely sustained the rebellion, and remained in Sudan following its demise. In fact, one of the mahdi���s most trusted companions, the elderly Muhammad al-Dadari, was a Fulani man from Sokoto. Al-Dadari reportedly played a crucial role in organizing the mahdi���s succession in the moments following his death.

It is difficult to quantify how many among those who journeyed east on the Sudan Road from West Africa did so to take part in resistance, or to seek refuge from European colonization, especially as these migrations blended with other types of mobility. Many people traveled to perform the regular pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, and journeyed back to West Africa. Christian Bawa-Yamba���s book Permanent Pilgrims, and Al Amin Abu Manga���s extensive scholarship, show that many West Africans settled in Sudan and formed diasporic communities, often finding an economic incentive to do so. Gregory Mann has explained that in a 2001 census, Mali counted the number of Malians living in Sudan and Egypt to be 200,000, twice as many as the 100,000 Malians estimated to live in France, illustrative of the fact that Africans migrate a lot more within the continent than outside of it.

These stories enrich our understanding of intracontinental migrations, and give us tools to connect the modern histories of countries rarely thought about in conjunction, such as Mali and Sudan. They also help us rethink the essentializing of African refugees: historically, seeking refuge on the continent has encompassed a variety of experiences, including West African Muslims who chose to emigrate rather than living under European rule.

Nonviolent guerrilla cartographers

Photo by Mohamed Tohami on Unsplash

Since its emergence in December 2018, and during its impressive course, the Sudanese revolution resembles in my mind Deleuze’s description of Foucault: “A new cartographer.” Sudanese revolutionaries created a new, metaphorical space that allowed the revolution to take root. They rejoiced in the space, reconfigured, redefined, and re-demarcated it, closing it off partially or completely according to what these space poets saw fit.

The first exultation with space came on December 19, 2018, via viral videos transmitted on social media. These videos were effectively a livestream of the ruling party���s headquarters set ablaze in the working-class city of Atbara, turning it into pure creosote in Sudan’s nervous system, expelling fear and instilling hope for restructuring solidarity after thirty years of national mass depression. Signs flooded the space and the revolution began to rediscover a power that connected action to a collective existence.

To achieve a sense of solidarity, the Sudanese re-discovered traditional tactics in the form of guerilla urban warfare and attrition maneuvers, but all under the banner of a nonviolent revolution. It was difficult, if not impossible, to directly confront a regime that had in the September 2013 uprising killed hundreds and locked up thousands in its notorious prisons well known for their torture methods. Still the events of September 2013 were an opportunity to lay the foundations of the Sudanese Resistance Committees, which came to be known later as the Neighborhood Committees, playing a leading role in the #Tasgot_Bas (Just Fall) revolution six years later.

In their pamphlet book “Declaration”, the Marxists, Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, drew the common features and characteristics of the 2011 cycle of struggle that began in Tunisia and then Egypt, and eventually spread to the squares of Western metropolises:

These movements do, of course, share a series of characteristics, the most obvious of which is the strategy of encampment or occupation. A decade ago the alter globalization movements were nomadic. They migrated from one summit meeting to the next, illuminating the injustices and antidemocratic nature of a series of key institutions of the global power system: The World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the G8 national leaders, among others. The cycle of struggles that began in 2011, in contrast, is sedentary. Instead of roaming according to the calendar of the summit meetings, these movements stay put and, in fact, refuse to move. Their immobility is partly due to the fact that they are so deeply rooted in local and national social issues.

Since its inception, the #Tasgot_Bas (#Just_Fall) revolution has had its own unique style, stemming from the Sudanese youth���s long experience of resisting Omar al-Bashir regime with its repressive Islamic ideology. But at the same time, it is an experimental albeit pragmatic, open-ended style that can be expressed in one phrase: a routing table. For those who are unfamiliar with the term, a routing table is inside a computer network host: it lists the routes to particular network destinations. It is essentially a map with an infinite number of possibilities radiating outwards from its core.

On December 25, 2018, a signed statement by the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) (a banned independent trade union umbrella) called on people to march in their millions towards Sudan���s Presidential Palace in Khartoum while calling on the president to step down and to hand over power to a civilian government. Even if the procession failed to achieve its goal, it laid the foundation for a poetic valorization between SPA and the revolutionaries. And because the identity of the SPA members was concealed from all, including the forces of the regime and its repressive militias, the link between the power of action and the collective existence was made only through statements and declarations. A published statement on the SPA���s social media page specifying times and routes was enough to mobilize tens of thousands who poured out in a given time and space. This collective action of a mass mobilization broke through fear, but more importantly, new assemblages begun to form in its wake.

For four consecutive months until April 2019, day after day, the Sudanese marched in peaceful processions throughout the country. Processions were called for through SPA statements which included a scheduling of place, time, and slogan. The multitude observed schedules faithfully and betrayed them even more (betrayal is another name for freedom as Deleuze had warned us). Treachery came from the most mysterious bodies, the Neighborhood Resistance Committees, which represented the microphysics of the peaceful movement. Whenever the schedule identified a neighborhood for an assembly, the other neighborhoods also organized marches in clear betrayal of the order. Ultimately, certain neighborhoods (Buri, for example) mobilized so often that they became a practice in devotion to betrayal. It must be mentioned here that these resistance committees were based on a traditional system of values rooted in participation, sheltering all and protecting the oppressed. A system that often worked in the past as a false fantasy, before the revolution transformed it into a spirit of trust and solidarity. The revolution had moved into the most intimate of space, the homes, the family and the conscience of mothers and fathers.

It can be said that the vague, decentralized, and horizontal body of SPA was a product of the Resistance Committees ���loyalty to betrayal���, fueled by a system of solidarity values in which everyone was involved. It is one of the rare moments of the revolutionary praxis maturity in human history.

The cartographer revolutionaries redrew their city. Khartoum’s architecture is no longer what it was. A new city emerged with towering barricades, and murals painted with revolutionary graffiti (many of which resembled the drawings of children and madmen). Bridges linking the capital���s neighborhoods across the Nile and those linking the capital to the state and the states with others were closed off. But we must emphasize here an interesting feature: Often times, the empty streets coincided with the continuation of the revolution. No sooner did the revolutionaries set fire to tires and build barricades in the narrow alleys of their neighborhoods, than security personnel and the police personnel invaded them with their mounted pickup trucks. And so revolutionaries retreated inside houses, climbing onto roofs to film the dullness and stupidity of their assailants, the police cars falling into the traps the people had set up for them. Sudanese rebels discovered, through pragmatic experimentation, the weakness of their opponent. Masked regime militias were falling one after the other in the alleys of the new city, unknown to them. Whenever the security forces wore masks that concealed their faces, the city wore a new map, chanting, “Peaceful oh Khartoum.” In the background, these sound effects of children, women and revolutionaries echoed. Khartoum became a carefully re-mapped city, where only the revolutionaries knew its paths.

These peaceful guerrilla warriors carried out a revolution with a unique characteristic within the cycles of global struggle that began in the 21st century. But we have to be careful here. In a way, the Sudanese revolution is considered a continuation of a continuous and diverse process that had begun before; its causes stem from a localized tragedy of global capital���s greed and its entanglement with the repressive model of Western democracy, linked by a declaration of universal rights that is abstract in its conception of a human. However, at the same time, reflection shows that the action-image of the #Tasgot_Bas revolution had a strategic uniqueness that moves away from the distinction of Negri and Hardt between the two tendencies of the revolution that marked the 21st century. Sudan did not have a ���nomadological��� revolution like Porto Alegre, nor was it as sedentary as Tahrir Square. In its daily deterritorialization and reterritorialization with ���strike and run��� style, the Sudanese revolution resembles more the strategies of the mid-twentieth century liberation movements, the ���barricades��� of the guerrilla wars of the student and labor movements and drug cartels in the sixties, and the attrition tactic of Algerian war of liberation. What collects these models and places them in the Sudanese case is the map, the routing table, that was re-configured and that now offers a number of possibilities moving into the future.

The Arabic version of this piece was published in the October issue of the Lebanese magazine Bidayat. I would like to thank Professor Benoit Challand and Raga Makawi for their valuable comments regarding this English version.

November 17, 2020

History Class

March on Tillary Street in New York. Image credit Doug Turetsky via Flickr CC.

Frederick Cooper, who recently retired from the history department at New York University (NYU) and for many years taught at the University of Michigan, is one of the giants of African studies, history, and qualitative social science. Since the mid-1970s, he has produced ten single-authored books, numerous co-authored and edited books, and more than 115 articles and chapters, many of which have been translated into a number of different languages. The quality and originality of Cooper���s work has shaped not only African studies, but also the theory and methods of the social sciences more broadly. Furthermore, through his commitment to mentoring PhD students, Cooper has played a distinguished role in producing new generations of Africanist historians, anthropologists, and scholars in other fields.

The influence of Fred Cooper���s work has extended far beyond the academy. As he rose to prominence in the 1970s, he became a forceful and influential contributor to debates about African economies and strategies for economic development. In his famous 1981 essay ���Africa and the World Economy,��� Cooper argued for reaching beyond smug assumptions of teleological economic change by which Africa might eventually move toward European-style industrialization and ���modernity,��� while at the same time taking issue with radical stances that blamed African poverty on the continent���s subordination to and exploitation by the world economy. His insistence on the primacy of African actors, and on respecting and documenting the reasons they chose to pursue particular strategies, has influenced scholars as well as development practitioners, economic planners, and public spheres in Africa. Similarly, the power of his work on empire has been a critical counterweight to successive waves of apologists for European colonialism, who not only sanitize the brutal history of empire but argue for reimposing it on countries deemed ���failed states.���

Lisa A. Lindsay

Moses E. Ochonu

In the age of Black Lives Matter, scholars and the general public are paying renewed attention to historical systems of oppression and exploitation���slavery, colonization, racism���and their memorialization and preservation in institutions and structures. What might BLM activists learn from Africanists and other scholars who have studied inequality in different contexts?

Frederick Cooper

There is a real tension between the importance of addressing the pain that comes from the history people of African descent have faced of enslavement, colonization, and racism, and addressing issues of inequality across time and space. This tension can be a source of fruitful exploration.�� The histories of enslavement, colonization, and racism are not ���out there��� but right here; one cannot understand the United States or France any more than Nigeria or South Africa without a focus on these subjects. We live in a day and age when most thinking people will not defend, as was possible until a startingly recent time, these structures, but the way they shaped the institutions we live with remains profound. It is important as well to keep our attention on how political actors have engaged with unequal structures and tried to change them. Revolution and oppositional solidarity are essential parts of the story, but not the only ones. That is why I am drawn to Senghor���s insistence on conjugating horizontal and vertical solidarities. Unequal relationships are still relationships and they can be pushed and pulled on. Studying history gives us instances where small cracks in an edifice of power can be forced open, as well as instances where there has been no realistic alternative to all-out struggle. Studying history doesn���t tell us what strategies should be pursued in the present, and historians should be aware of both the value and the limits of what they have to offer to new generations of activists. But studying history does give us examples of different forms of engagement and their consequences. Right now, the need for political engagement even within deeply flawed structures is particularly acute.

Lisa A. Lindsay

Moses E. Ochonu

As a white American historian of Africa who early in his career had a foot in African American history, how do you interpret the racial politics of our field, which has gone through several phases and tends to resonate differently with different generations of Africanists?

Frederick Cooper