Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 151

November 3, 2020

When Americans took a global health crisis seriously

Brooklyn, NY. Image credit Zach Korb via Flickr CC.

In May 2014, I moved to Liberia to work with one of the many NGOs that sprouted up in the country after the civil war ended in 2003.

Several months earlier, the first reports of an unprecedented outbreak of the Ebola virus disease (previously unknown in West Africa) had emerged. At the time, I largely ignored them. As I uprooted my life for what I expected to be a prolonged residence in Liberia, I had no inkling that the virus would shortly insinuate itself in my life in a dramatic way.

Much like the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, Ebola revealed global inequities and exerted a debilitating psychological drag alongside its medical effects. My fellow Americans, who were so quick to condemn West Africa(ns) during the Ebola crisis, would be well served to recall their recent alarm as they struggle to address the coronavirus.

After reports of a spate of Ebola cases in March and April 2014, there appeared to be a lull in the virus��� spread. Few cases were reported in Liberia during the month of May when I arrived.

This proved to be the calm before the storm, however. By late June, communities in Monrovia were beginning to be considered epicenters of the outbreak, whereas previously the preponderance of cases had been confined to the northern borderlands.

However, it was only with the July death in Nigeria of Patrick Sawyer, a Liberian-American consultant for Liberia���s Ministry of Finance, that the tempo of everyday life really began to change. Sawyer���s passing was quickly followed by that of Samuel Brisbane, a leading doctor.

An environment riddled with tension and angst enveloped Monrovia, as a previously weary populace began to accept the seriousness of the unfolding developments. This situation contrasted markedly with the US response to COVID-19, where the country���s views on the gravity of the epidemic have been divided, even as cases skyrocket.

I soon left Liberia behind for the remainder of the year, but my colleagues later told me of a grim, intense period of earnest work. My employer was involved in work around good governance, but we quickly pivoted to a number of projects raising awareness about Ebola, as did practically every NGO in the country.

In early August, I departed on a previously scheduled business trip.�� The scene at the Monrovia airport, was grim, with worried masked individuals crowding the low-capacity airport. Conversely, despite the disruption COVID-19 has wreaked on American lives, and the explicit guidance to wear masks in public settings, it is not uncommon for travelers to refuse to wear masks.

I thought I would soon be back in Monrovia, perhaps having to delay my return by a few extra weeks. However, as with those who anticipated that the coronavirus pandemic would only briefly interrupt their routines, I was severely mistaken.

When I arrived in the US in October, Americans were firmly in the grip of Ebola hysteria, although the country had seen only a handful of cases.

In a marked reversal of the current politicized response to the coronavirus in the US, Republican governors in New Jersey (Chris Christie) and Maine (Paul LePage) took a hard-line approach, advocating for an American nurse who treated Ebola patients in Sierra Leone to remain in isolation. The nurse had initially displayed an elevated body temperature, but subsequently tested negative for Ebola.

Republicans in Congress also attempted to restrict travel to the US from the West African nations affected by Ebola. They were backed by Donald Trump, then a private citizen, issuing a string of tweets expressing his concern with the virus and urging the US to ���Stop the Flights!���

Conversely, in Liberia, George Weah, then in opposition, was on the same page with the government. He raised awareness about Ebola through song and also served as the government���s Peace Ambassador until November 2014.

Americans denigrated West Africans for not taking the crisis seriously and refusing to follow international health guidance, such as cremating loved ones who passed away from the virus.�� The inability of the US to get the coronavirus epidemic under control as a result of massive resistance to expert guidance shows how hypocritical these judgments were.

In September 2014, a team of Ebola health experts was massacred in Guinea, drawing widespread, incredulous criticism among Western expats in Liberia. Yet just a few years later, President Trump called on Americans to ���liberate��� states who had imposed stringent lockdowns to stem the coronavirus spread. His rhetoric apparently spurred armed protestors to demonstrate at the capitol building in the US state of Michigan.

Beyond illuminating American hypocrisy, West Africa���s experience with Ebola holds a number of sobering lessons for coronavirus-ravaged nations in the economic sphere as well.

The core of central Monrovia is not the same post-Ebola. My favorite Liberian club, Pepper Bush, closed, never to reopen. The same was true of my favorite rooftop drinking spot, the Bamboo Bar. In perhaps a sign of the changes Western nations may expect as they recover from the coronavirus, Monrovia���s development has increasingly centered on the more spacious Sinkor suburb (there are notable exceptions).

Liberia���s international connections have also failed to bounce back to their pre-Ebola levels.�� British Airways and Delta halted flights to Liberia during the Ebola outbreak and never returned. Regionally, Gambia Bird, The Gambia���s national carrier, collapsed as a result of Ebola-induced pressure.

The international attention Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea received as a result of the outbreak had little lasting impact. Billions of dollars were pledged to Ebola relief���although only a third of it has been disbursed, according to the United Nations. Furthermore, most of what was spent provided for the implementation of temporary stop-gap measures, rather than long-term improvements.

For several weeks during the latter part of the Ebola outbreak, the Liberia Water and Sewage Corporation was unable to provide piped water to most of Monrovia. Shockingly, the government of Liberia and the international community were not able to leverage the moment to transform the delivery of the good essential for the hygiene practices needed to contain Ebola. Yet, West African countries were able to mobilize contract-tracing efforts in a way that the US has utterly failed.

Comparisons between Ebola and the coronavirus are inexact. Nonetheless, a coterie of officials from the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf administration, including the president herself, penned opinion pieces in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic, highlighting Liberia���s lessons learned and success in beating back the virus. These pieces were generally laudatory of the administration���s response.

African nations have learned much from their Ebola experience���Senegal seems to have been particularly effective in proactively working to minimize the spread of the coronavirus, offering a bed to all infected (and their contacts). However, given the poor American response to coronavirus, focusing on the grim outcomes and lost opportunities of Liberia���s Ebola crisis might make for think-pieces that better resonate with American policymakers.

Ebola hysteria prevailed among many Americans in 2014. While their sentiments were misguided and rooted in discriminatory and xenophobic attitudes, recalling them would at least remind Americans of a time when they took a global health crisis seriously.

November 2, 2020

Africa’s forgotten refugee convention

The High Commissioner for Refugees, Sadruddin Aga Khan (right) and OAU Secretary General Mr. Diallo Telli at the signing of the OAU Convention on 13 June 1969 in Geneva, Switzerland. �� UNHCR

Every year many of the about 200,000 refugees from dozens of countries across the continent in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya turn out to celebrate World Refugee Day on June 20. But when asked, few of them remember that this day marks June 20, 1974, the entering into force of an African answer to an international refugee convention. The Organization of African Unity (OAU), founded in 1963 as an aspirational pan-African project, started discussions about formulating an African refugee convention just one year after its inception. The OAU���s Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa finally came into being in 1969 and was ratified in 1974. However, as Marina Sharpe and others have shown, the convention struggled to significantly ameliorate the situation of African refugees across the continent as implementation challenges amounted. To understand the coming into being of the 1969 convention, we need to examine the global historic context, and the regionally specific confluence of decolonization struggles and ideas about pan-African solidarity.

After World War II, refugees became codified in international law. As a response to large scale population movements, the world���s first legally binding refugee convention came into being, the 1951 Convention relating to the status of refugees (referred to as the Geneva Convention). African heads of state saw the Geneva Convention, with its emphasis on individual, political, and civil rights, as the product of a European tradition. They were motivated to draw up an agreement that would render international refugee legislation applicable to the African context and reflect African circumstances and values around refugee protection. Central to this were notions of African solidarity, pan-Africanist support for decolonization refugees and advances in responsibility sharing, temporary protection, and voluntary repatriation. This, however, proved to be more challenging than originally envisioned. The drafting process lasted from 1964 to 1969 and involved various working groups consisting of ambassadors and legal experts and resulted in presentations of five drafts at different conferences across Africa. After much discussion and false starts, one of the first and few legally binding documents the OAU ever produced emerged. The document is said to have paved the way for group-rights to claim refugee status, to have first codified the principle of voluntary repatriation, introduced the prohibition of refoulment (expulsion of refugees), and to have framed asylum as a peaceful, non-political act. At a Seminar for National Correspondents and Meeting of the Consultative Committee in 1970, the OAU���s own Bureau for the Placement and Education of African Refugees celebrated the convention as ���a very progressive document, which can efficiently help towards a permanent solution to the Refugee problem in Africa��� and further demanded that ���all those dealing with the refugee problem in Africa ��� should make of it their bible.��� This, however, was not to be as ratification and implementation were slow and enforcement inconsistent. The OAU lacked the political power and a body that effectively oversaw the broad adoption of the 1969 convention into national laws. This gap regarding the supervision of the 1969 convention remains to this day.

To understand the 1969 convention���s origin three things are important. First of all, before the 1967 protocol to the Geneva Convention was ratified, African refugees were excluded from international refugee law, which limited its application to European World War II refugees. After the 1967 protocol, one of the initial reasons for beginning the drafting process disappeared and it now became a question of how to supplement the Geneva convention rather than to draft the first convention applicable to African refugees. The UNHCR, protective of the Geneva convention, became involved in the later drafts, so the African convention did not emerge in isolation but close cooperation with an international organization that saw itself as the custodian of the Geneva Convention and its protocol.

Secondly, refugee numbers within Africa were not only on the rise, but because many displaced people hailed from decolonization struggles, supporting them was a crucial political project for the OAU. In 1964, there were about 400,000 refugees; by 1972 the number had risen to about 1 million. Anti-colonial solidarity emerged as an important organizing principle in both the creation of the OAU and the 1969 convention. Refugees-as-freedom-fighters were worthy of protection, but so was the territorial integrity and political sovereignty of the newly independent states. These negotiations revealed the tensions between securitization and sovereignty and pan-African solidarity.

And thirdly, pan-African ideology was central to the creation of the OAU and the treatment of refugees within the continent. Ethiopian Ato Kifle Wodajo, the first Secretary General of the OAU, in 1964 penned an article about Pan Africanism in the Ethiopian Observer, underscoring the destructive role of colonialism and the imperative that ���the only way to salvation for the African people is self-government.��� The simple but effective message was that Africa���s strength lay in its unity as decolonized continent. This thought also motivated the refugee convention. Young independent nations like Tanzania, for instance, followed an ���open door policy��� and saw refugees not as ���problems��� but as potential for national development. Referred to as ���settlers,��� refugees effectively functioned as what Joanna Tague calls ���displaced agents of development,��� building infrastructure like roads, clinics, and schools in remote areas of the country. The convention was intended to codify refugee protection across the continent, thereby providing a set of principles to be applied in refugee management.

Refugees have not become a global topic only in the 21st century. Part of a global conversation about refugee rights and protection, the OAU refugee convention served in part as an inspiration for the Latin American Cartagena declaration of 1984. The study of refugees from a historic perspective is pertinent as much of Europe, the United States, and other parts of the world, from Bangladesh to South Africa, have been preoccupied with what is often labelled a global ���refugee crisis.��� As of today, we know too little about seeking and providing refuge in the global South, where the majority of refugees have been and continue to be hosted. This blog series is a contribution towards illuminating the African context specifically, and refocusing our attention to stories that have been written out of national histories for too long. The global ���refugee crisis��� today is at its core a human crisis that generates hopes, fears, and expectations which ultimately influence political and legal agendas. Understanding what historical conditions once made possible a more generous and hospitable reception of refugees than we can imagine would be enshrined in law today and thinking through historical alternatives can inspire us to think anew about alternate possibilities for the future.

Coming to America?

Max Ostrozhinskiy, via Unsplash.

On Tuesday, America heads to the polls in what is being billed as its most important election in recent memory. For good reason, as it presents the chance to vote out of office Donald Trump, an incompetent demagogue whose callous handling of the COVID-19 pandemic provides final testament to the disaster that has been his presidency.

But is Trump really the worst thing that���s happened to America? As Jamelle Bouie wrote in The New York Times not so long ago, ���Everything we���ve seen in the last four years���the nativism, the racism, the corruption, the wanton exploitation of the weak and unconcealed contempt for the vulnerable���is as much a part of the American story as our highest ideals and aspirations.��� No group of people know the nature of America as this paradox of lofty dreams and failed state���open to all but selectively so���more than the people who desperately try to get in, and who in turn, America desperately tries to keep out.

Joining us on this week���s episode of AIAC Talk to speak about African migration to the United States, are Abraham T. Zere and Aya Saed. Abraham is a US-based Eritrean exiled writer/journalist, and in a recent piece reflecting on his experiences travelling as a stateless person for Al Jazeera, he wrote that ���immigration systems are built to make immigrants feel like they pose a threat to their host country and the world at large.��� Why are Africans treated as the biggest threat, and not only in Europe where their dangerous journeys for a better life are much profiled, but in America as well, where little is spoken about them at all?

A few weeks ago, reports came out that US immigration officers tortured Cameroonian asylum seekers to force them to sign their own deportation orders. Although deportations and anti-migrant sentiment are a continuous feature of American politics, what���s striking about Trump���s presidency is how much he has emboldened entities in border control and immigration enforcement like ICE���such that they���re adopting Gestapo tactics and cementing themselves as a genuinely fascistic element in American politics, and one bound to outlive Trump.

Aya Saed is a Bertha Justice Fellow at the Center for Constitutional Rights challenging unlawful detentions, counterterrorism practices, the criminalization of dissent, and systemic unlawful policing practice. How have these organizations become a logic unto themselves? Who else is empowering them? How has their evolution been enabled by successive US presidents, and why are they so hard to reign in? As Aya recently wrote on the site about American law enforcement ������as a matter of principle, [it] seems incapable of dislodging anti-Blackness from its daily operation.��� How then, can it possibly be transformed?

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 SAST, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on Youtube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

If you missed our episode last week, we were joined by Sa���eed Husaini and Annie Olaloku-Teriba to discuss #EndSARS and the politics of race, class and movementism in Nigeria. Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

November 1, 2020

Energy transitions and colonialism

Photo by khaoula ben on Unsplash

This post is part of our series ���Climate Politics.���

The year 2020 has seen an unprecedented oil price crash, causing a shock to the fossil fuel industry. The impact has been brutal among oil companies, especially in the high-cost US shale oil sector. As for oil-producing African countries, such as Angola, Algeria, Libya, and Nigeria, more economic strain has been added to their economies with mounting budget deficits and a hemorrhaging of their foreign exchange reserves. Against this backdrop, some analysts have rushed to speculate that the pandemic could kill the oil industry and help save the environment. Caution however must be exercised in face of such euphoric claims and wishful thinking.

In times of crisis or otherwise, if we are serious about moving beyond oil, it is crucial to closely examine the linkages between fossil fuels and the wider economy and address the power relations and hierarchies of the international energy system. These relations are rooted in colonial and neocolonial legacies, as well as practices of dispossession, plunder of resources, and land grabs, especially in the global South.

When we talk about energy in the popular imaginary, we talk about coal, oil, and gas. Most of these resources (especially the latter two) come from the South. The mode of controlling and plundering these resources is called extractivism. It was set into motion in 1492 with the conquest of the Americas and has been structured through colonialism, slavery, exploitation, and sheer violence. It continues today with the creation of ���sacrifice zones��� with ���sacrificial people,��� as well as in the form of imperialist war machinations and the militarist governance of the world.

The economies of the global South are inserted in a subordinate position within a profoundly unjust global division of labor: on one hand as providers of cheap natural resources and a reservoir of cheap labor, and on the other as a market for industrialized economies. This situation has been imposed and shaped by colonialism and attempts to break away from it have so far been defeated by the new tools of imperial subjugation: crippling debts, the religion of ���free trade���, structural adjustment programs (SAPs), among others. Much of this has happened with the backing of parasitic domestic elites.

These tools of domination not only lock countries in the global South into an outward-looking economic model���geared toward responding to the demands of the rich countries���but also limit the policy space for making sovereign decisions, such as moving away from fossil fuels. A telling example in this respect is the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), a dangerous investment agreement that allows the fossil fuel industry to keep hold of resources and continue harming the planet.

Agribusiness is another locus where imperialist domination and climate change intersect. It is one of the drivers of climate change and, moreover, keeps many countries in the South prisoners of an unsustainable and destructive agrarian model. This model is based on the export of cash crops and the exhaustion of land and the rare water resources in arid and semi-arid regions, such as Egypt and Morocco.

Although certain Western governments portray themselves as pro-environment by banning fracking within their borders and setting carbon emission-reduction targets, they offer substantial support to their multinationals corporations to exploit shale resources in their former colonies, something that France did with Total in Algeria. Displacing the costs of such a destructive industry from North to South is one strategy of imperialist capital in which environmental racism is wedded to energy colonialism.

Transitions to renewable energy can be extractivist in nature. Two examples from North Africa show how energy colonialism is reproduced in the form of green grabbing. The Ouarzazate Solar Plant was launched in 2016, and was praised to be the largest solar plant in the world. But scratching under the surface reveals a gloomy picture. First, the plant was installed on the land of Amazigh agro-pastoralist communities without their approval and consent. Second, this mega-project is controlled by private interests and has been financed through $9 billion worth of debt. Third, the project is not as ���green��� as its proponents claim it to be. It requires extensive use of water to cool and clean the solar panels. In a semi-arid region like Ouarzazate, diverting water from drinking and agriculture can be fatal to the locals. The same is true for the Tunur Solar Project in Tunisia, which delivers low-cost power to Western Europe while depriving Tunisians from much needed energy. Familiar colonial schemes are being rolled out in front of our eyes: the unrestricted flow of cheap natural resources (including solar energy) from the South to the North, while Western Europe fortifies itself to prevent human beings from reaching its shores.

A green and just transition must fundamentally transform and decolonize our global economic system, which is not fit for purpose at the social, ecological, and even biological level. It also necessitates an overhauling of the production and consumption patterns that are energy-intensive and utterly wasteful, especially in the global North. We need to break away from the imperial and racialized (as well as gendered) logic of externalizing costs that if left unchallenged, only generate green colonialism and a further pursuit of extractivism and exploitation (of nature and labor) for a supposedly green agenda. The fight for climate justice and a just transition needs to acknowledge the different responsibilities and vulnerabilities of the North and South. Ecological and climate reparations must be paid to countries in the South that are the hardest hit by climate change and have been locked by global capitalism in a predatory extractivism.

In a global context of an imperial scramble for influence and energy resources, any talk about green transition and sustainability must not become a shiny fa��ade for neocolonial schemes of plunder and domination.

October 30, 2020

Blackness in Amsterdam

BLM protest in Amsterdam. Image credit Jan van Dasler (Shutterstock.com).

Amsterdam’s black history is being brought to the fore by the efforts of black activists challenging racism and the institutional erasure of Dutch participation and subsequent prosperity from slavery. Reflecting on both the suppression and weaponization of stories of blackness beyond the infamous Zwarte Piet, Oyunga Pala reflects on black presences and solidarity in this city. This post, from our partnership with The Elephant, is part of a series curated by member of our editorial board, Wangui Kimari.

The Dam square, a major tourist trap in Amsterdam, is one of its busiest locations, often teeming with visitors flowing from the streets of Kalverstraat, Damstraat, and Nieuwendijk in the heart of the Amsterdam canal zone.

Dam Square is within walking distance of the Red Light district and the Amsterdam Central Station. On the east side of the tram tracks is the Amsterdam national monument, a prominent obelisk erected in 1956 in memory of the World War II soldiers, that I hardly noticed when I arrived in Amsterdam in September 2019 from Nairobi, Kenya.

Dutch historian, Leo Balai, author of the book��Slave Ship De Leusden, noted that there are two stories of the Amsterdam canal zone. Amsterdam���s golden age in the 17th century is a story of pride and prestige but also one of astonishment shrouded in shame.

The Dam square is an architectural marvel that is of great historical significance to the makeup of the city. Built as a dam in the 13th��century at the mouth of the Amstel river to hold back the sea, the city grew around it and the modern metropolis of Amsterdam would emerge from these origins. This square was considered the birthplace of capitalism when the first��stock exchange in the world opened in 1611.These were to be my impressions of Amsterdam���s history were it not for two significant events that happened in 2020. The first was the coronavirus pandemic and the second was the murder of George Floyd. The Dam square morphed into an intriguing site of conflated memories, depending on who you asked.

At the height of the coronavirus health restrictions in early June, I broke protocol to join a massive crowd that filled every inch of the square in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in America following the lynching of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Despite stringent public gathering restrictions, residents of Amsterdam showed up in full force. The gathering was in violation of the 1.5m distance rule and despite the pragmatic Dutch sense, it was impossible to observe the social distancing demanded by the organizers.

The protest, galvanized by a collective of anti-racism activists in the Netherlands, attracted a multicultural crowd. Young Dutch nationals of all extractions gathered to listen to fiery speeches from a group of select speakers, the most prominent being the organizers of the KOZP (Kick Out Zwarte Piet,��or ���Black Pete���) campaign in the Netherlands. All of the speakers were black. Activist after activist, reiterated the same message, Black Lives Matter in America and in the Netherlands too. An African American man who had lived in Amsterdam for 27 years told me this kind of black agency was unprecedented in the Netherlands.

Out of the many stories of the black experience in this country, it is the story by Jennifer Tosch, a Dutch cultural historian and the founder of the Black Heritage Amsterdam Tour, that enlightened me the most, being one of the few English speakers. I did not know that slavery was a central part of Amsterdam���s legacy. The city hall that overlooks the Dam square was built in 1648 and became the home of the Society of Suriname, established in 1683, when the city of Amsterdam became a share holder in the colony of Suriname.

A month earlier, another unprecedented event occurred in this same square. On May 4, the King of the Netherlands, Willem-Alexander, walked into an empty Dam square, to lay a wreath. (May 4th is a day of remembrance of fallen war heroes in the second World War.) King Willem-Alexander asked for an apology pointing out that the profiling of the Jews started with a sign in the famous Vondelpark that said ���No Jews Allowed Here.���

My Afro Dutch friends pointedly maintain that the black people of the Netherlands are still waiting for their apology. Presently many Dutch people like to say they do not see race and express great pride for being a society that espouses high social principles.

As an African categorized as a black person, it is easy to recognize racial undertones in a series of cultural mannerisms that define relations with non-white Dutch citizens. Perhaps none more jarring than the Dutch cultural phenomenon of Zwarte Piet, the helper of Sinterklaas, where white people traditionally appear in black face being the highlight of the festivities. This tradition is so deeply embedded in the Dutch cultural psyche that I have met several Afro Dutch citizens who grew up loving Zwarte Piet as a benign folk festival character, being none the wiser to the racial stereotypes it reinforced. In 2020, Prime Minister Mark Rutte stated that the government had no role in banning Zwarte Piet, which was described as a folk tradition, even as he empathized with the sentiments of those opposed to it.

As an African from Kenya, examining the demographics of the city, one can recognize institutional racism, based on where the black immigrants stay and how they slot into society as labor, basically essential workers on the lower tier. Europe���s black presence is tolerated as long as black people do not challenge the established status quo or as James Baldwin famously put it, ���As long as you are good.���

Observing the largest gathering of black people I had ever seen in Amsterdam, I realized, their pain was familiar, yet we knew so little of each other, separated not just by geography and language but also a suppression of our stories.

In Africa, we identify with ancestry and nationality and typically develop race consciousness when we travel abroad and discover we are ���black.��� In the Netherlands, I was confronted with the politics of color and belonging. In my regular commute, I often ask black Uber drivers if they are Dutch. Typically, the reply would be: ���I am born and raised in the Netherlands, but my parents are from Morocco (or Suriname, Aruba, Curacao or Ghana).���

One generally identifies with where one truly belongs, all others just become labels, necessary for navigation in an unequal world. I see a generation of young Dutch who hail from immigrant backgrounds, grappling with the nationalism of the country where they were born. Where the notion of belonging is beholden to whiteness as the singular representative of authentic Dutch nationality.

In July, one month later, I returned to the Dam square, this time as a participant in a tour organized by Jennifer Tosch. She organizes tours presenting the reality of Black experience in Amsterdam hiding in plain sight, in the built architecture as a testament to a memory from another time, a past hauntingly never really vacating the city.

It is fascinating to discover that just a little above eye level are symbols to the city���s past held in time. The tour starts at the Obelisk in Dam square where Jennifer points out that black contribution to the struggle against Nazi-occupation is notably minimized. The history of the Dam square is a tale of two peoples, one held glorious in time and another forgotten and erased.

Jennifer���s tours are borne out of her search for belonging, as a child of Surinamese��parents who immigrated to America, and a desire to reconnect with her Dutch heritage. She was soon to discover that memories accorded to Black people of the Netherlands are sparse, and only recently getting mainstreamed.

The tour involves an interrogation of Amsterdam���s architecture from the Golden Age and how the city remembers its black presence revealing how racial superiority can be built into architecture. Coming from Kenya, where colonial records were expunged and burnt, Amsterdam���s slavery heritage seems treasured as valued memory, representing an age of prosperity.

As Jennifer poses, what does one do with this knowledge? What does one do when one becomes aware of what these symbols mean and represent? In Dutch schools, like in Kenyan schools, the critical colonial history is scantly taught. It is more the reason why we need new stories to help us bridge these gaps in knowledge.

The aim of a story is to give root to cultural foundations but stories have to be true even when they are painful to recollect. Institutionalized racist systems are still a challenge given the various ways they manifest around the globe.

Our duty should be to challenge stories that have been weaponized against people of color. The goal of solidarity is enhanced by access to stories that open up avenues for cross cultural perspectives on shared histories. As novelist Arundhati Roy noted, ���There���s really no such thing as the ���voiceless���. There are only the deliberately silenced or the preferably the unheard.���

The Black Heritage tour ends at Rokin street, a few meters from the Dam square. Here we are confronted with the tableau of a black figure on the gable of a city house facing the street. Jennifer tells us that it is the figure of a black moor owned by Bartholemeus Moor, who was a slave trader and original owner of the property. This is about all the information she has managed to gather on this individual so far.

I stare at this unknown figure and in it, I see a waking reminder of why we have to look back into our past with critical eyes. In the spirit of the Twi-Ghanaian tradition of Sankofa, look back for that which is forgotten to gain the wisdom and power needed to craft a new future.

October 29, 2020

Kenyan statues must fall

Statue of Jomo Kenyatta in Nairobi. Image credit

Rogiro via Flickr CC.

In the last few months, Kenyans on Twitter have been circulating images of statues of political elites replaced by deserving national heroes. Most notable is the replacement of the statue of the first president Kenyatta with that of Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi. This movement has been spurred by the toppling of statues in the US and Europe, where protestors are demanding that their countries grapple with the protracted systemic racism that pervades quotidian Black life.

Calls for the removal of statues that serve as colonial and racist relics have become common means of subverting power structures. In 2015, the #RhodesMustFall movement at the University of Cape Town in South Africa successfully called for the removal of British colonialist Cecil Rhodes statue. Rhodes, a British imperialist and mining magnate, was at the forefront of laying the foundations of apartheid in South Africa. This decolonizing movement sparked similar outrage on other campuses, as in Oxford, where protesters are now demanding the removal of the Rhodes statue by the university. Similarly, in the US, the politics of memorialization remain contentious, as calls for institutions to atone for their involvement in slavery continue.

Closer to home, in Kenya, what does the fall of statues mean for most postcolonial cities that are mired in complex and intricate histories, whose architecture centers colonial rulers and the postcolonial elite? Cities were, and remain, arenas of power contestations, political games, and socio-cultural constructions. These conjunctural spaces are important sites of study in that they not only inform us about the larger political situations in the country, but also the relationship between the nation-state and its citizens, the pre-independent state, and its former metropole. Borrowing from Marxist thinker Henri Lefebvre who contends that conceptions of space have always been political, analyzing city structures is paramount.

Attempting to trace the history of Nairobi���s statues and monuments brings up the city���s deep ties to British colonialism, manifested in the politics surrounding this memorial architecture. During the colonial period, England���s proclivity for erecting monuments and naming streets and physical features to honor their own heroes was a tool for their imperial project as they established Western dominance. For example, the Duke of Connaught unveiled the Queen Victoria statue in 1906, signifying the ascendancy of British rule in Kenya. Alibhai Jevanjee, an Indian who owned a shipping company that worked with the Imperial British East Africa Company���a colonial enterprise that administered the protectorates before the British government assumed full responsibilities���paid for its construction. The Queen���s statue was located in the Jevanjee Gardens in the Central Business District until 2015 before it was vandalized. And, in celebration of King George V���s 25-year reign, his life-like statue graced the newly built High Court Square in the city center. Later, during a state of emergency (1952-1959) imposed by the British colonial government in response to growing anti-colonial upheavals, the administrators erected the East Africa Memorial and the King George VI Memorial. The East Africa Memorial, built in 1956 in the Nairobi War Cemetery, recognized the efforts of the multi-racial troops that fought in Italian Somaliland, Southern Ethiopia, Kenya, and Madagascar in an effort to prop up loyalty to the colonial government. In 1957, the King George VI memorial plaque was put up along Connaught Road, now Parliament Road, to assert colonial presence. These statues and monuments were taken down in 1964 after Kenya was recognized as a republic, signaling the end of British rule.

Some might argue that the tearing down of colonial monuments reduced Nairobi���s significance as a site of memory, however telling accurate history to prevent erasure of the past should be emphasized. Initially, removal of the statues, as well as renaming exercises, were a means to promote nationalism and reduce imperial domination in post-colonial Nairobi. Political elites co-opted this process to position themselves at the forefront of the country���s independence struggle, erasing the efforts of deserving nationalists and groups that fervently fought colonization, such as the Mau Mau.

The erection of monuments in Nairobi after independence was strategically undertaken to inscribe power and shift the landscape. These notable monuments were important instruments in asserting authority over Kenyan citizens and especially those who lived in the city and interacted daily with these structures. In 1973, the government commissioned a London-based sculptor, James Butler, to design a twelve-foot seated statue resembling President Kenyatta, showing continuity with the colonial monumental landscape by replacing King George VI plaque at the city square. The statue stands as an island in front of the Kenyatta International Conference Center (KICC) square���the conference center being one of the more salient buildings in Nairobi. The KICC was the tallest building in the city for about 26 years, underpinning the strategic position of the Kenyatta statue. Interestingly, President Kenyatta launched the conference center and the statue during the 10th anniversary of Kenya���s independence.

President Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi came to power in 1978, after Kenyatta���s sudden death and his era was also riddled with monuments as commemorative tools. Just as Kenyatta had the Harambee (pulling together) philosophy, which emphasized collective participation and self-help in development, Moi developed Nyayo, (footsteps) as he was keen on following Kenyatta���s ideals. Nyayo, intended to be a moving force and denoting peace, love, and unity, would later be legitimized as Kenyan law. To be ���anti-Nyayo [was] to be anti-Kenya.��� Moi set about building monuments all over the city that reflected an ideological philosophy that those around him deeply espoused. On the 20th anniversary of Kenya���s independence in 1983, two monuments were launched: a grand water fountain in Central Park and an intricate National Monument at Uhuru Gardens, just outside the city.

Prior to these celebrations, rumors spread of an alleged coup by Charles Njonjo, a member of the cabinet challenging Moi���s credibility. In response, Moi called for impromptu elections, ensuring that Njonjo���s cronies would be kicked out of the government. The decision to erect these two monuments at the end of the year was, therefore, a strategic signifier that the Moi/Nyayo government was still in power. Geographically, the locations of these monuments were no coincidence either. The Nyayo Fountain was built in Central Park, one of the few remaining public green spaces that most Nairobians frequented to unwind and where most political rallies were held. The National Monument was erected at Uhuru Gardens, the site for the symbolic lowering of the Union Jack at independence. This prominent white Nyayo monument was flanked by two black sculptures to show, ironically, that the government stood for peace and purity.

Erecting statues, as well as renaming streets, institutions, and buildings in Nairobi was meant to signal new political leadership and ideologies. It was also meant to recognize freedom fighters, whose efforts the independent government criminalized and largely ignored. Memorialization is ongoing to date, and despite the practical justifications to erect statues in memory of freedom fighters, the motives of such projects have remained deeply political. For example, it was not until 2007 when Dedan Kimathi���s statue was unveiled, finally recognizing the tremendous efforts of the Mau movement. This statue was put up following surviving fighters��� outcry to honor their marshal. Previously, Kenyan leaders had considered the movement a ���terrorist��� organization, dropping this colonial-era categorization in 2003, more than 50 years after it was imposed. This would finally allow freedom fighters to demand compensation from the British government for the torture they endured during the rebellion. While Kimathi���s statue is a pride of the city and remains a site of protest and prayers, it has been neglected���unlike Kenyatta���s statute that remains guarded in a controlled space. Furthermore, despite this symbolic recognition of the war heroes, Kimathi���s family, as well as other Mau Mau veterans, continue to live in squalid conditions dispossessed of their land, as the political dynasties plunder our country.

Nairobi remains a space where imperial and postcolonial ideas continually collide to create a new political hybrid that uplifts elite actors while disenfranchising the majority. Monuments celebrating members of the political elite dominate the political landscape, shaping public opinion through farcical reputation-building. As , we also insist on not only interrogating and falling our physical structures, which belie the deeds of our ���founding fathers,��� but also providing history about these monuments that foregrounds the efforts of those who actually fought for our independence.

Guinea’s authoritarian afterlives

Image credit Nomi Dave.

As the world���s media focuses on the US elections, we should consider another 2020 ballot, also featuring an unpopular incumbent president, a deeply divided nation, questions about the integrity of the electoral system, and interference from Russia. This is the situation in Guinea, where presidential elections were held on October 18. The results of that vote are still under dispute, as both the sitting president Alpha Cond�� and the opposition leader Cellou Dalein Diallo have declared victory and the police and military have subsequently rained down violence on protesters.

Local news sources are describing the Guinean situation as ���electoral pandemonium.��� State authorities have shot and killed dozens of civilians, destroyed houses and private property, and cut off internet services for several days. What happened to the promises of a new democracy that were made only ten years ago?

Guinea has been making uneasy progress towards democratic rule for decades, from a market women���s revolt against S��kou Tour�����s economic policies in 1977 to pro-democracy demonstrations in the 2000s and continuing to the present day. While the country has seen a succession of authoritarian leaders since 1959, writers such as Laye Camara and Djibril Tamsir Niane, countless journalists, and everyday citizens have risked their lives and livelihoods to demand change. Social ideals of interdependence and truth to power are rooted in the precolonial Mande empire, and remain at the center of popular debate around leadership and responsibility today.

Image credit Nomi Dave.

Image credit Nomi Dave.Yet Guinean people are also wary about protest, as it disrupts economic activities, jams the streets, and often leads to police brutality and spectacular state violence. To many, authoritarian rule offers stability and familiarity, particularly in a region that saw civil wars in C��te d���Ivoire, Liberia, and Sierra Leone through the 2000s. Authoritarianism has also long been entangled in feelings of nostalgia, collectivity, and national pride. Guineans remember the Tour�� era with mixed feelings���twenty-six long, bloody years but a moment of independence, pan-Africanism, and anti-imperialism. They remember their glorious history rooted in the Mande empire, a history that postcolonial dictators such as Tour�� consciously evoked. These memories offer a sense of certainty and self-recognition, in contrast to the unknowns of a democratic future.

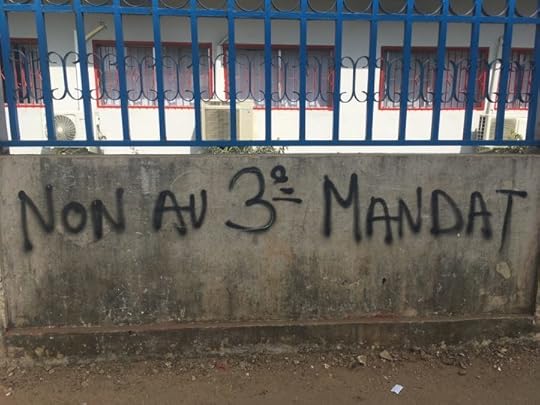

After years of reforms and demonstrations, Guinea held its first democratic elections in 2010. Many people hailed Alpha Cond�� for his history of exile and opposition and his training and work as a lawyer. Yet the Cond�� years have been disastrous for Guinea, with ever-deteriorating living conditions, cuts to schools and basic services, and the senseless crushing of oppositional voices. Democracy has proved a mirage, as presidential and legislative elections are continually mired in conflict and Cond�� has inflamed ethnic divisions between Fulbe and Maninka people. With vocal support from Russia, Cond�� recently pushed through a new constitution to allow him to run for a third (and eventually, fourth) term, effectively erasing his first two terms from the count.

What Guinean people have learned over the past decade ��� perhaps what they already knew ��� is that democracy is not easy, its meanings and goals are not clear, and it takes work well beyond elections. As Moses Ochonu recently noted in the case of Nigeria, despite the insistent rhetoric of promise they carry, elections do not represent an endpoint in the search for dignity and rights. Nic Cheeseman reminds us that elections may be the all-important symbols of success for donor nations and international observers, but they rarely reshape daily experience for ordinary people.

Image credit Nomi Dave.

Image credit Nomi Dave.Fortunately, in the case of Guinea, the country has two resources that offer some hope. First, since media reforms in 2005 and 2006, the country has seen a creative explosion of political commentary and news broadcasts well beyond state channels. Private radio and TV stations and newspapers have proliferated and are unafraid to voice dissent. In particular, feminist news outlets such as Actu-elles inform and mobilize young women, while a number of vocal female broadcasters such as Moussa Y��ro Bah further bridge the close worlds between private media and activism in Guinea. The Cond�� government has taken a hard view of these oppositional voices, and has subjected journalists to censorship and violence, including the death of a young journalist Mohamed Diallo in 2016. But although embattled politically and economically, private, dissident journalism in Guinea���through old and new media���is a growing force.

The second resource that many Guineans hold is a patriotism twinned with a healthy skepticism towards power. Love of country does not blind them to the violence and violations of the state. Rather, they mobilize love and wave the flag as a call to opposition and a better Guinea. While patriotism and love have historically been wrapped up in Guinean authoritarianism, in memories of a glorious past linked to postcolonial Big Men, protesters and journalists are reappropriating this narrative and these feelings for dissidents to claim, for a genuinely post-authoritarian future.

The Guinean present is tense and the future remains deeply uncertain. But as many throughout the globe find ourselves teetering on the thin line between authoritarianism and its other, we can recognize and salute the work and love of those there who are fighting for hope.

October 28, 2020

Dismantling and transcending colonialism���s legacy

Photo by berenice melis on Unsplash

This roundtable is part of the ���Reclaiming Africa���s Early Post-Independence History��� series from Post-Colonialisms Today (PCT), a research and advocacy project of activist-intellectuals on the continent recapturing progressive thought and policies from early post-independence Africa to address contemporary development challenges. Sign up for updates here.

In ���decolonial��� discourse, the African leadership landscape is flattened to the point of becoming a caricature. In an earlier variation of this caricature, Kwame Nkrumah���s injunction of ���seek ye first the political kingdom��� was presented by political scientist Ali Mazrui as a deficient obsession with political power to the neglect of the economic. In the current variation, the neglect of epistemic ���decoloniality��� is characterized as the deficient underbelly of the ���nationalist��� movement.

Kwame Nkrumah, S��dar Senghor, and Julius Nyerere are not only three of the most cerebral figures of Africa���s ���nationalist��� movement, but unlike Amilcar Cabral they lived to lead their countries in the aftermath of formal colonial rule.

Contrary declarations notwithstanding, Senghor, Nkrumah, and Nyerere were acutely aware of the colonial epistemological project and the need to transcend it. Indeed, philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne���s re-reading of Negritude as epistemology argued that its salience lies in the dissolution of the binary opposition of subject and object in the logic of Ren�� Descartes. Whatever one���s take on the specificity of Senghor���s claims of Africa���s modes of knowing���by insisting on the interconnectedness of subject and object���he deliberately sought to mark out what is deficient in modern European epistemology and valorize African systems of knowledge. This epistemological project is built on a distinct African ontological premise.

Nkrumah and Nyerere were most acutely aware of the urgent need to displace the epistemic conditions of colonization. In the case of Nkrumah, the imperative of epistemic decolonization was most forcefully expressed in the 1962 launch of the Encyclopedia Africana project, initially with W.E.B. Du Bois as editor, and the 1963 launch of the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana, Legon.

Nkrumah���s 1963 speech at the launch of the Institute stressed the epistemic erasure at the heart of colonialism, linking political and epistemic freedom. ���It is only in conditions of total freedom and independence from foreign rule and interferences that the aspirations of our people will see real fulfilment and the African genius finds its best expression,��� Nkrumah argued. If colonialism involves the study of Africa from the standpoint of the colonialist, the new Institute of African Studies was charged with studying Africa from the standpoint of Africans. Its responsibility, Nkrumah argued, is the excavation, validation, restoration, and valorization of African knowledge systems.

Nkrumah exhorted the staff and students at the new Institute to ���embrace and develop those aspirations and responsibilities which are clearly essential for maintaining a progressive and dynamic African society.��� The study of Africa���s ���history, culture, and institutions, languages and arts��� must be done, Nkrumah insisted, in ���new African centered ways���in entire freedom from the propositions and presuppositions of the colonial epoch.��� It is also worth remembering that the subtitle of the most philosophical of Nkrumah���s writings, Consciencism, is ���philosophy and ideology for de-colonization.���

Much is made about Nyerere surrounding ���himself with foreign ���Fabian socialists.������ Yet the most profound influence on Nyerere���s thoughts and practice was not the varieties of European ���socialisms��� but the ���socialism��� of the African village in which he was born and raised���with its norms of mutuality, convivial hospitality, and shared labor. Nyerere���s modes of sense-making (which after all is what epistemology means) was rooted in this ontology and norms of sociality. For Nyerere, the ethics that are inherent in these norms of sociality stand in sharp contrast to the colonial project. It was, perhaps, in Education for Self-Reliance (1967) that Nyerere set out, most clearly, the task of the educational system in postcolonial Tanganyika, one that is not simply about the production of technical skill but the contents of its pedagogy. It is a pedagogy that requires the transformation of the inherited colonial system of education (Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism, 1968). The pedagogy is anchored on the three principles of Nyerere���s idea of a society framed by African socialism: ���quality and respect for human dignity; sharing of the resources which are produced by our efforts; work by everyone and exploitation by none.��� It frames the ethics of a new, postcolonial society.

Whatever their limitations, it was not for lack of aspiration and imagination. Nyerere is the one who most aptly communicated to us the responsibility of the current generation to pick up the baton where the older generation laid it down. The struggle for political independence was never understood as an end in itself. The ���flag independence��� we so decry makes possible the task that subsequent generations must undertake and fulfil. The task of realizing the postcolonial vision is as much a responsibility of the current generation as it was of the older generation.

Finally, as Mwalimu reminds us, on matters concerning Africa, ���the sin of despair would be the most unforgivable.��� Avoiding that sin starts with acknowledging and embracing the positive efforts of the older generation while advancing the pan-African project today.

The need to dismantle and transcend colonialism���s legacy

Photo by berenice melis on Unsplash

This roundtable is part of the ���Reclaiming Africa���s Early Post-Independence History��� series, edited by Aishu Balaji, from Post-Colonialisms Today (PCT), a research and advocacy project of activist-intellectuals on the continent recapturing progressive thought and policies from early post-independence Africa to address contemporary development challenges. Sign up for updates here.

In ���decolonial��� discourse, the African leadership landscape is flattened to the point of becoming a caricature. In an earlier variation of this caricature, Kwame Nkrumah���s injunction of ���seek ye first the political kingdom��� was presented by political scientist Ali Mazrui as a deficient obsession with political power to the neglect of the economic. In the current variation, the neglect of epistemic ���decoloniality��� is characterized as the deficient underbelly of the ���nationalist��� movement.

Kwame Nkrumah, S��dar Senghor, and Julius Nyerere are not only three of the most cerebral figures of Africa���s ���nationalist��� movement, but unlike Amilcar Cabral they lived to lead their countries in the aftermath of formal colonial rule.

Contrary declarations notwithstanding, Senghor, Nkrumah, and Nyerere were acutely aware of the colonial epistemological project and the need to transcend it. Indeed, philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne���s re-reading of Negritude as epistemology argued that its salience lies in the dissolution of the binary opposition of subject and object in the logic of Ren�� Descartes. Whatever one���s take on the specificity of Senghor���s claims of Africa���s modes of knowing���by insisting on the interconnectedness of subject and object���he deliberately sought to mark out what is deficient in modern European epistemology and valorize African systems of knowledge. This epistemological project is built on a distinct African ontological premise.

Nkrumah and Nyerere were most acutely aware of the urgent need to displace the epistemic conditions of colonization. In the case of Nkrumah, the imperative of epistemic decolonization was most forcefully expressed in the 1962 launch of the Encyclopedia Africana project, initially with W.E.B. Du Bois as editor, and the 1963 launch of the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana, Legon.

Nkrumah���s 1963 speech at the launch of the Institute stressed the epistemic erasure at the heart of colonialism, linking political and epistemic freedom. ���It is only in conditions of total freedom and independence from foreign rule and interferences that the aspirations of our people will see real fulfilment and the African genius finds its best expression,��� Nkrumah argued. If colonialism involves the study of Africa from the standpoint of the colonialist, the new Institute of African Studies was charged with studying Africa from the standpoint of Africans. Its responsibility, Nkrumah argued, is the excavation, validation, restoration, and valorization of African knowledge systems.

Nkrumah exhorted the staff and students at the new Institute to ���embrace and develop those aspirations and responsibilities which are clearly essential for maintaining a progressive and dynamic African society.��� The study of Africa���s ���history, culture, and institutions, languages and arts��� must be done, Nkrumah insisted, in ���new African centered ways���in entire freedom from the propositions and presuppositions of the colonial epoch.��� It is also worth remembering that the subtitle of the most philosophical of Nkrumah���s writings, Consciencism, is ���philosophy and ideology for de-colonization.���

Much is made about Nyerere surrounding ���himself with foreign ���Fabian socialists.������ Yet the most profound influence on Nyerere���s thoughts and practice was not the varieties of European ���socialisms��� but the ���socialism��� of the African village in which he was born and raised���with its norms of mutuality, convivial hospitality, and shared labor. Nyerere���s modes of sense-making (which after all is what epistemology means) was rooted in this ontology and norms of sociality. For Nyerere, the ethics that are inherent in these norms of sociality stand in sharp contrast to the colonial project. It was, perhaps, in Education for Self-Reliance (1967) that Nyerere set out, most clearly, the task of the educational system in postcolonial Tanganyika, one that is not simply about the production of technical skill but the contents of its pedagogy. It is a pedagogy that requires the transformation of the inherited colonial system of education (Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism, 1968). The pedagogy is anchored on the three principles of Nyerere���s idea of a society framed by African socialism: ���quality and respect for human dignity; sharing of the resources which are produced by our efforts; work by everyone and exploitation by none.��� It frames the ethics of a new, postcolonial society.

Whatever their limitations, it was not for lack of aspiration and imagination. Nyerere is the one who most aptly communicated to us the responsibility of the current generation to pick up the baton where the older generation laid it down. The struggle for political independence was never understood as an end in itself. The ���flag independence��� we so decry makes possible the task that subsequent generations must undertake and fulfil. The task of realizing the postcolonial vision is as much a responsibility of the current generation as it was of the older generation.

Finally, as Mwalimu reminds us, on matters concerning Africa, ���the sin of despair would be the most unforgivable.��� Avoiding that sin starts with acknowledging and embracing the positive efforts of the older generation while advancing the pan-African project today.

Neocolonization on a plate, with a soda to go

Photo by Erik Mclean on Unsplash

The headline, which caught my attention as I glanced through the results of my ���coronavirus UK��� Google search, was ���Clear link between COVID-19 complications and obesity.��� Reading the article, which summarized the findings of a report released by Public Health England, I was reminded of a conversation I had with my aunt one year earlier. She expressed her displeasure with the insufficient number of McDonald���s-type fast food outlets in Ibadan, which made her visits back home less enjoyable.

Since I moved to the UK five years ago to continue my studies, I have met many people like my aunt; people who, despite having moved out of Nigeria before I could string sentences together, seem to have all the answers to Nigeria���s problems. To easily spot them in conversation, these ���the kind of things we can eat��� people, as Chimamanda Adichie called them in Americanah, look out for phrases like ���what Africa needs to is������ and ���how we do things here in London������

I told my aunt I believed it was a blessing that these fast food chains were not common in Ibadan, pointing out the steps taken by the UK and several other high-income countries to reduce consumption of fast foods���such as calorie labelling, sugar reduction programs, and advertisement restrictions. ���Why do we want to eat ounje oyinbo (white people���s foods) once we get a little rich?��� I said frustrated. While my aunt unsurprisingly met my tirade with condescension, this conversation made me reflect on my own relationship with fast food growing up in Ibadan. The memory of eating my first burger remains vivid; my uncle, who unlike anyone else in my home at the time had travelled outside Nigeria, bought burgers for my siblings and I from the first KFC in Ibadan a few months after it opened. The heavy creaminess of mayonnaise and the crunchiness of the onions gave the burger an uncooked feel, one strikingly different from the foods I normally had for dinner.

As my parents rose up the socioeconomic ladder over the years, the number of the Western chains in the city increased, along with our appetite for fast food. For the vast majority of people in Ibadan, buying pizza from Dominos continues to represent more than buying food; it is a means to enhance perceived social status. It is not uncommon for the more privileged individuals to post photos on social media mocking lower-income individuals for having photoshoots in places like Dominos, KFC or the South African-owned supermarket, Shoprite. This preference for foreign products, known as consumer xenocentrism, often stems from people viewing their products, ideas, and lifestyles through the lens of colonial prejudice.

Beyond shaping dietary choices, consumer xenocentrism is deeply ingrained in the social fabric of Nigeria, with this relic of colonization influencing early responses to COVID-19. In April, the Nigerian government invited a team of 18 Chinese doctors to assist the response to the pandemic, because apparently the experienced medical personnel in the country were incompetent. This decision was met with huge backlash from Nigerian frontline healthcare workers, due to receiving inadequate support from the government during the pandemic and ongoing accusations of Chinese neocolonialism in Africa. This xenocentric mindset resulted in several African countries, including Nigeria, importing policies from countries such as the UK regardless of their applicability to these African countries.

For my master���s degree thesis, I analyzed obesity control policy documents across sub-Saharan Africa using a discursive sociological approach. My research shows that the rise in obesity levels was commonly presented as an individual problem, with most of the proposed solutions emphasizing the promotion of interventions to increase healthy eating and engagement in physical activity. This emphasis tends to discount the societal structures that drive unhealthy food choices in African societies, with the impact of colonization and neo-colonization on culinary habits remaining under-analyzed. While the rise in obesity levels is a global situation, the peculiarity of the situation in African countries stemmed from the relationship between risk of obesity and socioeconomic status.

There seems to be a consensus that the burden of obesity tends to shift from the rich to the poor as a country���s gross national income (GNI) per capita, or income level, increases. However, my research shows that, unlike in their European counterparts with comparable income level, the risk of obesity increases with socioeconomic status in several African countries. The common presentation of the dietary transition occurring in several African countries as an inevitable consequence of economic development masks the process of colonization, neocolonization, and acculturation as it pertains to food structures and choices in African societies. The export of Western food culture, from consumption to preparation, into African societies is an extension of the destruction of traditional food systems by European colonizers through the creation of cash-crop economies in the colonial era.

The rise in obesity, and obesity-related diseases in African countries, risks putting additional strain on already stretched national health budgets, potentially making these countries more vulnerable to future disasters such as COVID-19. There is a clear opportunity to arrest this rise by emphasizing the need for decolonization of personal and collective identity, by promoting campaigns to increase consumption of locally produced traditional foods, and promote healthier cooking methods. Will future policies address this? My aunt probably doesn���t think so.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers