Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 152

October 27, 2020

Enseigner dans les langues Africaines, pr��alable �� la d��colonisation des espirits

Image credit oneVillage Initiative via Flickr CC.

Cet article fait partie de notre s��rie: ��La litt��rature africaine est un pays��.

English version.

Je pense avoir une vue d’ensemble correcte du syst��me ��ducatif s��n��galais puisque j’y ai fait la totalit�� de mon cursus, de la primaire �� l’universit�� Cheikh Anta Diop. J’y ai aussi enseign�� des ann��es durant, �� tous les niveaux, jusqu’au moment o�� j’ai d��cid�� de donner la priorit�� �� ma propre production litt��raire. �� partir de l�� on se pose, sans forc��ment s’en rendre compte, les bonnes questions : quelle est la diff��rence entre ce que j’apprenais �� la Fac de Lettres de Dakar �� la fin des ann��es soixante et ce que l’on enseigne aujourd’hui aux jeunes S��n��galais apr��s six d��cennies d’ind��pendance ? D’avoir successivement enseign�� �� l’universit�� Gaston Berger du S��n��gal et �� l’American University of Nigeria m’a ��galement aid�� �� mieux percevoir les diff��rences entre pays africains respectivement appel��s francophones et anglophones. La pertinence de ces deux appellations est – soit dit au passage – fortement sujette �� caution mais elles permettent au moins de d��limiter grosso modo le champ de l’analyse.

Un observateur superficiel pourrait juger les deux syst��mes ��ducatifs radicalement dissemblables – ils le sont �� certains ��gards – mais dans le fond les similitudes sont assez nombreuses. Au S��n��gal et au Nigeria, les auteurs africains sont enseign��s d��s le d��but du parcours scolaire mais ce sont presque toujours les m��mes depuis les ind��pendances : Senghor, Beti, Semb��ne, Kourouma, Oyono, par exemple, pour les ”francophones” et Ngugi, Achebe, Awonor ou Armah chez les anglophones. Tr��s souvent on explore davantage le seul texte d’un ��crivain que son univers litt��raire personnel. Les lyc��ens arrivent ainsi �� l’universit�� en connaissant bien l’intrigue et les personnages de A Grain of Wheat, Things Fall Apart, Les bouts-de-bois-de-Dieu, Les soleils des ind��pendances, etc. C’est une excellente chose mais tout de m��me cela donne l’impression d’un savoir litt��raire sans vie, que l’on a ingurgit�� passivement pour ��tre en mesure de le restituer tel quel �� l’examen. Et l’oublier �� tout jamais, surtout quand on se tourne vers des activit��s professionnelles sans rapport avec la litt��rature. On peut r��citer ainsi par c��ur “Femme noire” et “Joal” de Senghor, sans presque rien savoir de l’auteur lui-m��me ou du contexte de sa cr��ation po��tique.

Il faut en outre noter l’ironie d’une situation o��, apr��s avoir rel��gu�� au second plan les auteurs fran��ais et britanniques, la p��riph��rie se contente quasi syst��matiquement de re-valider par son enseignement les auteurs africains reconnus au centre, c’est-��-dire �� Paris, Londres ou New York. C’est �� mon avis une situation extr��mement fascinante : en qu��te de l��gitimit�� litt��raire, les auteurs africains utilisant le francais ou l’anglais se focalisent sur des th��mes propres �� s��duire le lectorat occidental et cela les conduit aussi �� ��crire d’une certaine mani��re. Quand on en vient au fond, cela se traduit par une r��p��tion romanc��e des clich��s de l’Occident sur le terrorisme ou l’��migration, pour ne citer que ces deux th��mes “porteurs” en ce moment. On peut avoir ensuite dans les programmes scolaires africains ces ouvrages destin��s par leur contenu et leur forme au public occidental : ce qui peut donner le sentiment d’une avanc��e politique est en fait plut��t une source de confusion.

Dans la r��alit�� on enseigne moins l’Afrique que l’id��e que l’Occident se fait de l’Afrique.

Un travail de ”recentrage”, comme dirait Ngugi, serait certainement le bienvenu. Sans occulter l’apport de la diaspora, les ��tudes litt��raires africaines devraient faire de plus en plus de place aux auteurs vivant sur le continent. Des auteurs locaux existent mais personne ne les voit ni ne les entend. On a par exemple l’impression que toute la litt��rature du Burkina Faso se limite au seul nom de Monique Ilboudo, celle du Tchad �� l’��uvre de Koulsy Lamko, de Guin��e-Conakry �� celle Monenembo et Williams Sassine etc. M��me quand on parle du S��n��gal, de la C��te d’Ivoire ou du Cameroun, le nombre d’auteurs pris en compte est tr��s faible, ne refl��tant en rien l’effervescence litt��raire dans chacun de ces pays. Je sais qu’au Nigeria, sur ce plan, la situation est diff��rente. Le pouvoir d’attraction du Nord y reste ��videmment important �� travers ses m��dias et ses institutions acad��miques mais les auteurs nationaux n’y sont pas ignor��s ou encore moins m��pris��s. Il me semble qu’on peut en dire autant du Kenya, que je connais toutefois moins bien.

J’aimerais soulever, pour finir, ce point qui me semble crucial : les auteurs africains ne figurent dans les programmes scolaires qu’en fonction de leur langue d’��criture. Ainsi les jeunes Nigerians ne savent rien des auteurs camerounais ou ivoiriens et vice-versa. Quand j’ai fait d��couvrir �� mes ��tudiants nigerians des romanciers comme Bernard Dadi��, Mongo Beti et Kourouma, ils ont d’abord ��t���� d��concert��s. L’un d’eux, refl��tant l’opinion de ses camarades, m’a pos�� la surprenante et savoureuse question que voici : ”Pourquoi devons-nous ��tudier David Diop et Emmanuel Dongala alors que ceci est un cours de litt��rature africaine?”

En r��alit��, cette r��action avait surtout �� voir avec le fait qu’ils n’avaient jamais entendu ces noms et qu’ils ne savaient pas comment les int��grer �� leurs sch��mas mentaux. Je crois que l’un des tr��s rares auteurs africains d’expression fran��aise que tous connaissaient est Mariama B��. Mais le malentendu s’est tr��s vite dissip�� car ces ��tudiants nigerians se sont retrouv��s en terrain familier et ont donc d��couvert, non sans un discret ��merveillement, qu’il n’y avait aucune diff��rence notable aux points de vue th��matique et esth��tique entre les ��crivains nigerians et leurs homologues congolais. Il ��tait par exemple facile d’��tablir une jonction entre Kourouma et Tutuola, Ngugi wa Thiong’o et Cheik Aliou Ndao.

Ces deux derniers auteurs ont, justement, la particularit�� de contester la pr����minence de l’anglais et du fran��ais, langues coloniales, comme outils de cr��ation litt��raire et d’enseignement.

�� mon avis, la discussion sur les curriculae ne devrait pas rester prisonni��re des contenus, elle doit aussi explorer le volet relatif aux langues de travaail des universit��s africaines. Une belle exp��rience d’enseignement en pulaar et en wolof – j’en ai ��t�� un des instigateurs – est en cours depuis six ans �� !’universit�� Gaston Berger de Saint-Louis. Elle rencontre un succ��s exceptionnel, qui a agr��ablement surpris tout le monde. Pour la premi��re fois dans l’histoire du S��n��gal, une universit�� forme au plus haut niveau des sp��cialistes en pulaar et en wolof. Pour avoir ��t�� le tout premier �� y dispenser des cours de langue et litt��rature wolof, je m’estime bien plac�� pour dire que la rupture lib��ratrice passera par une r��appropriation du monde dans les langues africaines. �� l’��poque j’ai pu lire tr��s clairement dans les yeux de mes ��tudiants le soulagement de constater avec quelle aisance le r��el leur ��tait devenu intelligible.

Cela ne veut pas dire que ce sera facile : les complexit��s�� de notre douloureuse histoire et la radicalit�� de la destruction coloniale nous rendent toute t��che ingrate au point de paraitre insurmontable. Mais c’est �� cette aune des v��hicules du savoir, la seule ayant �� mon humble avis une r��elle port��e historique, que la d��colonisation des esprits pourra ��tre enfn s��rieusement au programme �� la fois de nos ��coles et de nos vies.

Decolonizing African literature begins with language

Image credit Rachel Tanugi Ribas via Flickr CC.

This post is part of our series: “African Literature Is a Country.”

Version Fran��aise.

I have a fairly accurate understanding of the Senegalese education system having pursued my entire education there; from primary school right up until Cheikh Anta Diop University. I also taught there for a few years, at all levels, until I decided to prioritize my own writing. From this vantage point, it is possible to start asking the right questions though without necessarily realizing it. What is the difference between what I was learning at the university in Dakar at the end of the 1960s and what we are teaching the Senegalese youth now after six decades of independence? I have successively taught at Gaston Berger University in Senegal and at the American University of Nigeria, and this has also helped me to discern the differences between two African countries respectively referred to as French-speaking and English-speaking. Indeed, the appropriateness of such descriptions is highly questionable but it allows us, even if somewhat crudely, to delimit our field of analysis.

A superficial observer might find the two education systems radically dissimilar. They are in some respects but there are several fundamental similarities. In Senegal and Nigeria, African authors are taught from the start of schooling, yet the authors have remained almost the same since independence: Leopold Senghor, Mongo Beti, Ousmane Semb��ne, Ahmadou Kourouma, Ferdinand Oyono for the ���Francophones,��� and Ngugi wa Thiong���o, Chinua Achebe, Kofi Awonor or Ayi Kwei Armah among the English speakers. Very often, there is a tendency to explore only one book by a writer rather than the writer���s unique literary universe. The high school students thus enter university having great familiarity with the plot and the characters of A Grain of Wheat, Things Fall Apart, God���s Bits of Wood, The Suns of Independence, and so on. This is excellent, but it also gives the impression of lifeless literary knowledge that has been passively absorbed as if to be regurgitated for an exam. And then it is forgotten forever, especially when one moves on to professional activities unrelated to literature. Thus, they can recite Senghor���s Black Woman and Joal by heart while knowing almost nothing about the author himself or the context of his poetic creations.

We must note the irony of this situation. After relegating French and British writers to the background, the periphery is content with systematically revalidating the center by teaching the precise African writers who are recognized at the center. By center I mean Paris, London, or New York. I find this to be a really fascinating situation. In their search for literary legitimacy, African authors, writing in French or English, often focus on themes that are likely to appeal to Western readers, and this also makes them write in a certain way. At the heart of it, this translates to a fabricated repetition of the West���s clich��s on terrorism or immigration, to name two ���timely��� themes of the moment. Such works then end up being part of the African school curricula, despite the fact that they are intended for the Western public in terms of their content and form. Sadly, what might give an impression of political advancement becomes a source of confusion.

The truth is, it is the Western idea of Africa that is more frequently taught than Africa itself.

The work of ���recentering��� as Ngugi would say, is very welcome. Without obscuring the contribution of the diaspora, African literary studies should give more and more space to writers living on the continent. Local authors exist but no one sees or hears them. For example, there is a sense that all the literature of Burkina Faso is limited to the single author, Monique Ilboudo. For Chad, it���s Koulsy Lamko; for Guinea-Conakry, its Tierno Mon��nembo and Williams Sassine, and so on. Even when we talk about Senegal, Ivory Coast, or Cameroon, the number of authors considered is very low and in no way reflective of the literary effervescence of each of these countries. I know that in Nigeria, the situation is different. The powerful attraction to the global North obviously remains important there through the media and its academic institutions, but national authors are neither ignored nor despised. It seems to me that the same can be said of Kenya, though I know less about it.

Finally, I would like to raise a point that is crucial to me: African authors only appear in school curricula based on the language they are writing in. Thus, young Nigerians know nothing about Cameroonian or Ivorian authors and vice versa. When I introduced my Nigerian students to novelists like Bernard Dadi��, Mongo Beti, and Ahmadou Kourouma, they were initially taken aback. Reflecting his classmates��� mindset, a student asked me a somewhat surprising and fascinating question: ���Why do we have to study David Diop and Emmanuel Dongala when this is an African literature course?���

In reality, this reaction was mostly to do with the fact that they had never heard these names and did not know how to fit them into their mental patterns. I believe that one of the very few African authors writing in French that they all knew is Mariama B��. But the misunderstanding dissipated quickly because these Nigerian students found themselves on familiar ground and discovered, not without a sort of wonder, that there were no perceptible differences to the thematic and aesthetic points of view between Nigerian writers and their Congolese counterparts. For example, it was easy to establish connections between Kourouma and Tutuola, Ngugi, and Cheik Aliou Ndao.

The last two authors, in particular, have been contesting the preeminence of English and French, the two colonial languages, as tools of literary creation and teaching. I believe that discussions on curricula should not remain trapped only in conversations about the content of literary works. They should also explore all the components of the languages chosen by the African universities for teaching literature.

A wonderful teaching experiment has been taking place in Pulaar and Wolof at Gaston Berger University in Saint-Louis, Senegal, and in fact, I was one of the instigators. It has been exceptionally successful, and this has pleasantly surprised everyone. For the first time in the history of Senegal, a university is training specialists in Pulaar and Wolof at the highest level. I was the very first instructor to offer Wolof language and literature courses there, which means I���m in the position to declare that the emancipatory rupture will require a reappropriation of the world in African languages. I could clearly see the relief in my student���s eyes and see how seamlessly reality had become intelligible to them.

I���m not saying that this will be easy: the complexities of our painful history and the radical nature of colonial destruction manages to make every task thankless to the point of seeming insurmountable. The decolonization of the mind can only become the order of the day if it can engage African languages as the conduits of knowledge. In my humble opinion, it is the only measure with true historical import.

The philosopher king

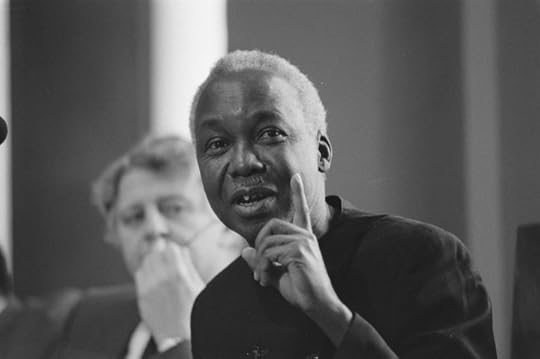

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Julius Nyerere was one of the most important leaders of the twentieth century. Tanzania gained independence from Britain in 1961 and Nyerere, known as Baba wa taifa (father of the nation), became its first president. Under Nyerere���s leadership, the state declared ujamaa (African socialism) as its postcolonial path forward and signaled its intention to build a society based on human equality and dignity. His commitment to nonalignment in the midst of cold war tensions and his support of African liberation movements garnered the attention of many around the world. Even after he stepped down in 1985, Nyerere continued to hold remarkable influence over Tanzanian politics. Today, twenty-one years after his death, his contested legacy continues to loom large in the nation, as his presence in the discussions surrounding the upcoming elections attests.

In early 2020, Tanzanian publishing house, Mkuki Na Nyota, released the three-part biography, Development as Rebellion: A Biography of Julius Nyerere. Penned by Saida Yahya-Othman, Ng���wanza Kamata and Issa Shivji, the books offer an impressively nuanced examination of a man who has been, in the words of the authors, ���revered and demonized in equal measure.��� Yahya-Othman is a retired professor of English Linguistics who taught at the University of Dar es Salaam, Kamata is a Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Dar es Salaam and Shivji is a retired Professor of Public Law and the first holder of the Julius Nyerere Professorial Chair in Pan-African Studies at the University of Dar es Salaam. A detailed exploration of Nyerere���s personal and political lives, this is also a multifaceted history of Tanzania and the political context in which its first and most influential leader emerged. Monique Bedasse had a brief conversation with Issa Shivji about his installment of the biography, Rebellion Without Rebels. Professor Shivji took on this biography after decades of thinking and writing about Nyerere and Tanzanian politics more broadly.

Monique Bedasse

What motivated you and your co-authors to write this biography?

Issa Shivji

It is a long story but I���ll cut it short. Even while Mwalimu [Swahili for ���teacher;��� how Nyerere is generally referred to in Tanzania] was still alive, I used to say half-jocularly that when the philosopher-king ceases to be a king���meaning he has left power���I���d like to do his biography. It never came to pass. Meanwhile, Mwalimu passed on in 1999.�� Between 2008 and 2013, I was the Mwalimu Nyerere Chair in Pan-African Studies at the University of Dar es Salaam under which, together with my co-authors���Professor Saida-Yahya Othman and Dr Ng���wanza Kamata���we organized many intellectual activities around Mwalimu���s ideas generally and his perspective on Pan-Africanism specifically. In the process we learnt that our younger generation knew very little about Mwalimu and his times. Unrelenting criticism, albeit subtle, of Mwalimu���s policies of Ujamaa and its alleged failure during the two decades of neo-liberalism had taken its toll. Our youth had a very lop-sided view of their recent political history. A more nuanced story of Tanzania under Nyerere and his uncompromising stand on nationalism against the constant onslaught of neo-colonial forces needed to be told.

Five years of working together also brought the three of us closer. Fortunately, at the time, the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology under its Director General Dr. Hassan Mshinda was amenable to consider our application for funding. Thus was born the Nyerere biography project. After some six to seven years of extensive research and writing, the three-volume biography was finally published in March 2020 by a leading local publisher Mkuki na Nyota.

Monique Bedasse

One of the strengths of this biography is that you force the reader to confront conflicting accounts of particular histories. An example of this is your treatment of the contested circumstances that led to Edwin Mtei���s resignation after the International Monetary Fund���s mission visited Dar es Salaam in 1979. Not only does this make for an engaging read, but it also ensures that we never lose sight of the fact that Nyerere and the other members of the Tanzanian government with whom he worked were fully human. Furthermore, it reminds us that the IMF���s visit is connected to both the larger story of the ���transition from socialism to neo-liberalism��� in Tanzania within a global context, and to the local history of contestation within the government. You bring together a vast array of sources to provide us with such complexity. Tell me about the research process for this book.

Issa Shivji

Hunh! Monique, it is like you read our minds. Yes, we wanted to tell a story which was both human and social. The widespread belief that Mwalimu always got his way was simply not true. Mwalimu���s ideas were contested and there was the ubiquitous struggle, class struggle if you like, like in any other society.

As for the research process, it was rather unconventional. We did exactly what we warn our PhD���s not to do. We entered the field without any pre-conceived ideas or hypothesis or even a research plan. The only guiding principle we agreed on was that in telling the man���s story we must also tell the story of his country and society; that we should desist from projecting Mwalimu as the hero and, broadly, we should apply the method of historical materialism. I leave it to the readers to assess how far we succeeded. With the wisdom of hindsight, for me personally, I think we succeeded pretty well in our first two objectives, but I am not sure if we equally succeeded in consistently applying the method of historical materialism.

I must say our research was very extensive and intense. We spent considerable time in the United Kingdom combing the UK archives but also visiting several university libraries and conducting interviews. We did over 100 interviews. Thankfully the retired leaders of the ruling party (CCM) and the state were very co-operative. We also were lucky to get access to the CCM archives and Mwalimu���s personal State House files kept at Mwalimu Nyerere Foundation. At the end of the process we found that we had collected piles of material and it was a challenge how to synthesize and analyze without falling into the trap of not being able to separate wheat from the chaff. Having said that, I must also underscore that we did not always eschew details where we felt that they needed to be recorded for future generations. It is the details, I believe, which helped us to bring out Mwalimu as human rather than some abstract political actor.

Monique Bedasse

You write that ���what is specific to Nyerere���s idea of equality is that it is inseparable by definition from the idea of utu���best translated as ���human dignity��� or ���humanness.��� You also argue that at the end of his career, ���he could rightly take pride��� in having successfully made this the basis of the nation he worked to build. I have long thought about Nyerere���s use of the word ���dignity ���and its meaning for postcolonial nations and for non-European peoples in particular. Would you please say more about that?

Issa Shivji

I���m absolutely wedded to the idea of human dignity and Mwalimu in his splendid language clarified this idea to me���it ceased to be a clich�� and became a fundamental concept around which the idea of equality is woven. We, therefore, argued that Nyerere���s idea of equality which has been around for at least a thousand years is fundamentally different from the liberal (bourgeois) idea of equality. For the latter, equality resolves itself in equal rights. For Nyerere, the essence of equality is dignity or humanity which cannot be captured by the notion of rights. Excuse me but I never tire of quoting Mwalimu���s beautiful poem on equality; in particular the following two stanzas. (I quote it first in Kiswahili, then in translation.)

Watu ni sawa nasema, zingatia neno ���watu���,

Siwapimi kwa vilema, ambavyo ni udhia tu,

Siwafanidi kwa wema, ambao ni tabia tu,

Lakini watu ni watu, mawalii na wagema.

Niseme maji ni maji, pengine utaelewa,

Ya kunywa ya mfereji, na yanayoogelewa,

Ya umande na theluji, ya mvua, mito, maziwa,

Asili yake ni hewa, hayapitani umaji.

I say people are equal, note the word ���people���,

I don���t judge them by their disability, which is only a bother,

I don���t compare them by their goodness, which is only a habit,

People are people, holy men and (palm-)wine tappers alike.

If I say water is water, you may understand,

Water to drink, water to shower,

Of dew and snow, of rain, rivers, lakes,

Its ancestry is in air; it does not deviate from its wateriness.

���Humanness��� is the ���wateriness��� of people. In a concomitant article he wrote on human equality, he explained it thus:

Human beings are equal in their humanity. Juma and Mwajuma do not differ in their humanity. In all other matters, Juma and Mwajuma are not equal, but in their humanity, they do not differ an iota. Neither you, nor me, not anybody else, nor God can make Juma to be more of a human being than Mwajuma or Mwajuma to be more of a human being than Juma. God can do what you and me and our fellow beings cannot do���God can create Juma and can make Mwajuma to be a different creature better or worse than a human being, but God cannot make Juma or Mwajuma to be better or worse human beings than other human beings; God can neither reduce nor increase their humanity.

What more can I say? Let me venture to suggest, though, that I think Nyerere���s concept of equality possibly gives us an anchor to construct an alternative discourse from the liberal discourse of equality and rights which is so hegemonic and yet it is so inadequate for postcolonial peoples to locate themselves in.

Monique Bedasse

After stepping down from the presidency, Nyerere spent the time between February 1986 and August 1987 traveling to different regions in an effort to recharge the party. In responding to complaints from the people about the failures of the party leadership, Nyerere reflected on the past and deduced that the leaders lacked the ���same fire and fight��� of their predecessors. As he saw it, ���during the struggle for independence, the party was fighting for freedom and knew its enemy. It was united in its objective and mission.��� As your analysis suggests, the question of ���who is the enemy?��� is an important one. Are you implying that Nyerere would have avoided certain challenges had he sought to answer that question at various points as the political terrain in Tanzania evolved?

Issa Shivji

It is a valid question but, frankly, answering it would be indulging in hypothetical history. What we can say is ���what happened��� rather than ���what could have happened if …!��� Were choices available at strategic conjunctures? Yes, they were. Why was this and not the other course of action chosen? Well, that can be explained only partly by the constraints of circumstances. The individual actor does make choices given his or her own outlook and social interests that he, consciously or otherwise, represents. The driving force for Nyerere was nation-building which demanded unity and which resulted in suppressing diversity or what he believed to be dissipating forces. So, in spite of formulating a beautiful phrase ���development as rebellion���, the title of the biography, he could not tolerate rebels who pointed towards a different course of action at strategic junctures. This is captured in the title of book three of the biography: Rebellion without Rebels.

Monique Bedasse

You end the book with a question: ���Was Julius Nyerere more of Plato���s Philosopher Ruler than Machiavelli���s Prince?��� Many authors attempt to resolve such an analytical problem; to tell us in more pointed terms how we should remember a particular historical figure. Why did you decide to end with a query?

Issa Shivji

We wrote this biography with utmost respect for our readers guided by the dictum, ���People think.��� People are capable of resolving the query in their own way���we have provided sufficient material and analysis. But, more importantly, the query underlines the oft-repeated observation that great persons in history are enigmatic. Enigma is the stuff of which greatness is made. Let me end by quoting from our preface to the biography:

Our biography of Nyerere is grounded in the history of people���s struggles in which Nyerere, the man, was immersed and from which his greatness emerged. Our narrative does not shy away from recounting controversies surrounding Nyerere the man, or providing a reasoned critique, occasionally severe, of Nyerere the politician. All this does not detract from his greatness. Controversies and critiques constitute the stuff of which great men and women of history are made.

October 26, 2020

Not waiting for a savior

Photo by Tai's Captures on Unsplash

Five months have passed since the coronavirus was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). Although Africa is the least affected so far, the number of confirmed cases and deaths in the continent is quickly rising���with 1.6 million confirmed cases and more than 39,000 deaths at the time of writing. Several African countries are bracing for what could become a full-blown health emergency, while at the same time strategizing on how to contain COVID-19���s devastating economic impact; ramifications of which affect far more people than the coronavirus itself.

Despite the challenges many African countries continue to face, the response to COVID-19 has been replete with admirable displays of agency, innovation, and ingenuity, demonstrating clearly that they are not waiting to be saved from the coronavirus. African agency is often dismissed in international relations and international development, yet the early preventive measures of several African countries are hard to overlook. By early March, many nations had already closed their borders, activated new or pre-existing health infrastructures and repurposed existing capacities (human and industrial resources) even though caseloads remained very low. Many in the continent observed the evolution of the outbreak in China, Europe, and the US, and recognized they would need more than an economic plan to respond effectively to the pandemic.

With only a few countries boasting capability to test citizens, procure, and transport supplies at scale, African countries turned to the convening power of the African Union (AU) and the African Center for Disease Control (Africa CDC) to address their shared vulnerabilities. By coming together, African countries worked to overcome their shared challenges���some related to the global market for medical supplies. They set up a joint procurement platform to help African countries bypass the highly competitive global market for personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical equipment, a system which continues to be characterized by price gouging and government protectionism. By resorting to collective and coordinated action against COVID-19, the continent���s response demonstrates the true power of solidarity; not just as a conceptual ideal underlying multilateralism, but a key element of effectiveness when responding to a pandemic or other public crises.

The response to COVID-19 in Africa goes beyond the remit of the state, however. African researchers, civil society, and individual citizens have galvanized their knowledge, finances, social capital, and ingenuity to address their needs. Citizens in Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria self-organized to establish food drives and food banks to help support those disproportionately affected by the economic depression. On social media, examples of African innovation and ingenuity proliferate, from touch-free handwashing tools, home-made ventilators prototyped in Somalia, the manufacture of testing kits under a dollar in Senegal, using drones to drop off testing kits in hard-to-reach places in Ghana, and repurposing production lines to manufacture PPE in Morocco, Ethiopia, and Kenya.

These positive developments have to be contrasted with the popular skepticism in many countries of the existence of coronavirus in Africa and its threats to Africans. This skepticism, combined with public negligence and the difficulty of maintaining social distancing continue to contribute to the growing numbers of COVID-19 cases in the continent. Nonetheless, the various innovations and acts of ingenuity from across the continent prove that local solutions for local problems are more effective than ���copy and paste��� imports. They also demonstrate that African solutions can sometimes respond to global problems.

The fight against coronavirus for most African countries focuses not just on devising national strategies for prevention, but also continental and global responses. Continental representatives are collectively weighing in on the global response to COVID-19, and negotiating with major global players to secure their interests���most notably vis-a-vis COVID-19 vaccine development and access to global capital to manage the economic impact of the pandemic.

African representatives at the United Nations have joined like-minded blocks, such as the European Union, to advocate for the framing of any future vaccine as a universally affordable and accessible product for the global public good. Efforts are underway, in collaboration with global scientific communities, to ensure that clinical trials are conducted on the continent to ensure their effectiveness in African communities.

The pandemic is projected to have a devastating impact on African economies. Currently, economists estimate that the continent will need between USD100 billion to 150 billion to finance its economic recovery. With this looming financial burden, debt relief and access to capital are essential to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic in Africa. The AU has been at the forefront of the global debates about economic recovery, insisting to global creditors and financial regulators that the global economy, as well as local African economies, cannot be rescued without a focus on these critical issues. Through its four special envoys, the AU has been negotiating debt relief and access to capital for African economies struggling to service their debt while simultaneously repurposing their budgets to respond to the costs of the pandemic.

The picture at the national level is rather mixed. Governments are trying to balance responding to the health challenges of the pandemic while simultaneously minimizing its economic impact. At the same time, the pandemic has also laid bare pre-existing governance problems such as corruption, gender based violence, state-sanctioned violence against citizens, diminishing civic and political space, and extension of party/presidential terms.

The picture of how successfully Africa has combated COVID-19 to date may be up for discussion, but the innovation and ingenuity demonstrated in the continent���s response to the pandemic deserves to be reflected in writing on the global response.

The view from the factory floor

Children collecting water from a pump provided by the factory. Image credit Manjusha Nair.

Abraham and Worku wore T-shirts and jeans soiled from laundering cloth in chemical dye solutions in the denim factory. They were 19 and 21 years old, studied until grade 10 and nine, and were working towards part-time diplomas in accounting at Rift Valley University in Bishoftu. When I interviewed them in October 2018, they had been in the factory for six months as laundry workers, where, along with 10 men and four women of similar ages, their job was to dye denim cloth in shades of blue and black. They were paid 900 to 1100 birr (25 to 30 USD) per month, which covered only their rent and part of their expenses on food, cellphone, and student fees.�� For the rest, they relied on their family. But they were happy: they were young, ate injera and shiro at the factory canteen, chatted with fellow workers while taking the free shuttle to and from the factory to the town where they lived with friends. A few of them had small family plots of teff and barley, which their little brothers and sisters harvested, or they helped by doing night shift at the factory. They liked that they had jobs, salary, and urban prospects. Their only complaint was that they were not given milk yet, a supposed antidote to the toxicity of chemicals they dealt with every day.

The 1979 Nobel Prize winning economist from the Caribbean, Sir Arthur Lewis, provided a model of economic development for poor countries that became influential for policy makers in African postcolonial nations: Use the labor from the subsistence economy in the capitalist sector without raising wages or creating skills, reinvest the earnings in further capital accumulation until all of the subsistence sector is absorbed in the capitalist sector and the economy takes off in its path to modernization.

A machine operator inside the factory. Image credit Manjusha Nair.

A machine operator inside the factory. Image credit Manjusha Nair.These and other developmental models, with their teleological predictions, have failed to take-off but have considerable purchase in Ethiopia, where the perception of an era of arrested development due to the prior command economy of Mengistu Haile Mariam (the Derg regime) is deemed responsible for trapping the country in the eternal backwardness of a rain-dependent subsistence economy, and the misery of famine and poverty. Industrial modernization has become a catch-all phrase for the policies of later governments, led by Meles Zenawi, the Marxist rebel from Tigray turned developmental reformer, and now Abiy Ahmed, who envisions a huge economic transformation through integrating Ethiopia into the global market.

Abraham and Worku worked in a denim manufacturing factory in the Keta industrial zone in Bishoftu municipality. The factory, owned by an Indian business group, was one among the many Chinese, Indian, Turkish textile, and garment units that moved to Ethiopia, towing their machines and products through the new expressways and train lines constructed with Chinese financial and technical help. Young Chinese entrepreneurs hung out with the locals in the lobby of the Ethiopian Investment Commission, tried injera listening to music in ���traditional��� restaurants, and drank coffee pressed from complicated Italian machines. They were lured by the young, 50 million-strong workforce ready to work at wages five times cheaper than in China, a duty-free export market enabled by the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) partnership with the US, and state subsidies.

Workers rip jeans to a given pattern. Image credit Manjusha Nair.

Workers rip jeans to a given pattern. Image credit Manjusha Nair.Students with whom I talked at the Ethiopian Civil Service University, my taxi driver Ararsu, and every other person, accused the foreigners, especially the Chinese, of ���looting��� the economy���an attempt to colonize a nation that has never been colonized. Nevertheless, nobody questioned the path of industrialization and economic growth for the transformation of Ethiopia out of a ���backwardness��� of deprivation, and a rurality that was in urgent need of repair. In Bishoftu municipality, 39 miles away from Addis Ababa (distance reduced due to the new Addis-Adama expressway built with Chinese assistance) there were 102 functioning industries manufacturing textiles, instant noodles, woodwork, and metal products. The young municipal administration employee whom I interviewed passionately stated that without these industries, ���there would be crisis in our country.��� Without doubt, industrialization was sought as a panacea to ethnic conflicts, resource crisis, and unemployment.

What prospects did it offer to the youth���more than half of Ethiopian population and the demographic advantage of the country���in the global market? Against the stories of deprivation and exploitation that I read elsewhere characterizing the textile and garment sector, there were evidences of better labor rights in this factory. One reason could be that the Ethiopian government has ratified all eight fundamental conventions of the International Labor Organization to protect labor standards. In the highly automated denim unit, 580 young, agile Ethiopian women and men, dressed in company T- shirts, denim jeans and face masks, operated the machines. They were supervised by equally young Ethiopian men and women, fresh graduates from textile engineering schools. All employees were recruited through job advertisements and there were written contracts. Their monthly salaries (not daily wages) were deposited in the Ethiopian Development Bank, and the factory owners contributed seven percent to the employee pension fund. The management had a collective agreement with the workers��� union, which was formed in 2018, after a prolonged discussion with the workers��� representatives. The agreement was printed in English, Amharic, and Oromia languages, and an English copy was emailed to me, upon request. The benefits included giving time off to employees to attend funerals.

Workers gather at the factory grounds. Image credit Manjusha Nair.

Workers gather at the factory grounds. Image credit Manjusha Nair.Yet, factory work was not preparing the workers for a stable future. The workers often left jobs, getting tired of the work rhythm and meager earnings. They did not learn many skills in their short stint at the factories. There were no state-mandated minimum wages and the workers��� pay barely covered their living expenses. They depended on their farm income and families to survive. There was no guarantee of employment, and eventually there was the chance of the textile and garment sector shutting down if the AGOA fell through, or yet another site for cheap production was identified, as has happened in other places. These youths were in unsustainable futures, and they were not experiencing the social transformations from the time of pastoral temporality to factory rhythms. One of the supervisors, Lydia, lamented about the plight of her fellow Ethiopians: ���The industry is good, but they [workers] have no future. They study up to grade 10, come here and work, get machine injury and leave. Or they wait until farming season and then leave.���

October 25, 2020

On AIAC Talk: End Police Brutality in Nigeria NOW!

#ENDSARS protest in Lagos, Nigeria. Image credit Kaizenify via Wikimedia Commons.

In October, protests erupted in Nigeria calling for the government to #EndSARS. The Special Anti-Robbery Squad was a federal policing unit established in 1992 to respond to a wave of crime that came about in Nigeria���s largest cities like Lagos and Abuja. But, increasingly, these officers (who did not wear uniforms but operated in plain, civilian clothes), became accused of harassment, torture, and extrajudicial killings, starting to mirror the thugs and gangs they were supposedly meant to be targeting, but instead being fond of brutalizing Nigeria���s urban youth.

Although Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari disbanded SARS on October 11, the demonstrations have persisted and have come to represent more than simply opposition to police violence, but a deep frustration with the status quo and the political class defending it. Driven by Nigeria���s youth, the protests are a seminal moment for discrediting widespread stereotypes that they are lazy and complacent, and reflect the disillusionment of young people globally who see the post-Cold War political-economic settlement as delivering nothing but inequality, joblessness, climate catastrophe and downright misery. They want something better.

Joining us to discuss these demonstrations and where they���re next headed, are Sa���eed Husaini and Annie Olaloku-Teriba. Sa���eed is a political scientist based in Lagos and contributing editor to Africa Is A Country, and has previously appeared on the show to discuss Nigerian politics, where he touched on some of the mobilizations which have preceded this moment such as Occupy Nigeria in 2012, the Take It Back Movement of 2018,�� as well as the #RevolutionNow movement started in 2019. How do these protests movements inform what we are seeing today? Considering that the #RevolutionNow campaign had protests as recently as August and is co-ordinated by a party platform, the Coalition for Revolution (CORE), how does its existence and efforts compare with the rapid growth of #EndSARS, which for now steadfastly remains a decentralized movement?

Annie is a British-Nigerian independent researcher based in London, working on legacies of empire and the complex histories of race. On a recent op-ed for Al Jazeera, Annie wrote that ���The movement is being supported financially not only by the large diaspora and Nigeria���s biggest stars, but also by foreign celebrities, such as American rapper Noname.��� Adding to this list are Cardi B, Rihanna, Drake, Trey Songz, Kanye West, Lewis Hamilton as well as football stars like Marcus Rashford, Odion Ighalo and Mesut Ozil.�� How do we make sense of this level of global attention, rare for protests happening in Africa? Does this express a newfound global consciousness around issues of police violence on the heels of #BlackLivesMatter international, or does their susceptibility to celebrity and corporate attention also make them easy to co-opt?

The protests are still happening, and scores of protestors have been arrested, injured or killed by law enforcement. If you are able to contribute to the fundraising for bail and hospital fees, food, water, and other expenses, please do so.

Stream the show Tuesday at 18:00 SAST, 16:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��Youtube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week, we had on Benjamin Fogel and Wangui Kimari to discuss the emptiness of anti-corruption politics, and then Sabatho Nyamsenda and Elisa Greco to zero in on the particular case of Tanzania as well as discuss its upcoming election (happening this coming Thursday!). If you missed the episode, you can watch clips from that show on our��YouTube channel, and the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

End Police Brutality in Nigeria NOW!

Protesters at the #ENDSARS protest in Lagos, Nigeria. Image credit Kaizenify via Wikimedia Commons.

In October, protests erupted in Nigeria calling for the government to #EndSARS. The Special Anti-Robbery Squad was a federal policing unit established in 1992 to respond to a wave of crime that came about in Nigeria���s largest cities like Lagos and Abuja. But, increasingly, these officers (who did not wear uniforms but operated in plain, civilian clothes), became accused of harassment, torture, and extrajudicial killings, starting to mirror the thugs and gangs they were supposedly meant to be targeting, but instead being fond of brutalizing Nigeria���s urban youth.

Although Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari disbanded SARS on October 11, the demonstrations have persisted and have come to represent more than simply opposition to police violence, but a deep frustration with the status quo and the political class defending it. Driven by Nigeria���s youth, the protests are a seminal moment for discrediting widespread stereotypes that they are lazy and complacent, and reflect the disillusionment of young people globally who see the post-Cold War political-economic settlement as delivering nothing but inequality, joblessness, climate catastrophe and downright misery. They want something better.

Joining us to discuss these demonstrations and where they���re next headed, are Sa���eed Husaini and Annie Olaloku-Teriba. Sa���eed is a political scientist based in Lagos and contributing editor to Africa Is A Country, and has previously appeared on the show to discuss Nigerian politics, where he touched on some of the mobilizations which have preceded this moment such as Occupy Nigeria in 2012, the Take It Back Movement of 2018,�� as well as the #RevolutionNow movement started in 2019. How do these protests movements inform what we are seeing today? Considering that the #RevolutionNow campaign had protests as recently as August and is co-ordinated by a party platform, the Coalition for Revolution (CORE), how does its existence and efforts compare with the rapid growth of #EndSARS, which for now steadfastly remains a decentralized movement?

Annie is a British-Nigerian independent researcher based in London, working on legacies of empire and the complex histories of race. On a recent op-ed for Al Jazeera, Annie wrote that ���The movement is being supported financially not only by the large diaspora and Nigeria���s biggest stars, but also by foreign celebrities, such as American rapper Noname.��� Adding to this list are Cardi B, Rihanna, Drake, Trey Songz, Kanye West, Lewis Hamilton as well as football stars like Marcus Rashford, Odion Ighalo and Mesut Ozil.�� How do we make sense of this level of global attention, rare for protests happening in Africa? Does this express a newfound global consciousness around issues of police violence on the heels of #BlackLivesMatter international, or does their susceptibility to celebrity and corporate attention also make them easy to co-opt?

The protests are still happening, and scores of protestors have been arrested, injured or killed by law enforcement. If you are able to contribute to the fundraising for bail and hospital fees, food, water, and other expenses, please do so.

Stream the show Tuesday at 18:00 SAST, 16:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��Youtube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week, we had on Benjamin Fogel and Wangui Kimari to discuss the emptiness of anti-corruption politics, and then Sabatho Nyamsenda and Elisa Greco to zero in on the particular case of Tanzania as well as discuss its upcoming election (happening this coming Thursday!). If you missed the episode, you can watch clips from that show on our��YouTube channel, and the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

October 23, 2020

Food crimes

Photo by Boudewijn Huysmans on Unsplash

The World Food Program received the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize “for its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict.” But many, both within and without the organization, cast aspersion on the merit of these claims. This post, originally published by The Elephant, is part of a series curated by Editorial Board member, Wangui Kimari.

Those who believe that food aid does more harm than good were probably flabbergasted by the decision by the Norwegian Nobel Committee to award this year���s Nobel Peace Prize to the World Food Program (WFP) for ���its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict.���

Fredrik S. Heffermehl, a Norwegian lawyer and long-time critic of the political and bureaucratic processes behind the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize, for instance, stated: ���We recognize the great value of the World Food Program, but the 2020 prize is much less ambitious than [Alfred] Nobel���s idea of ���conferring the greatest benefit to humankind.������

Mukesh Kapila, a former United Nations representative to the Sudan who blew the whistle on atrocities committed by the Sudanese government in Darfur, and who is now a professor of global health and humanitarian affairs at the University of Manchester, was even more scathing. ���It���s a bizarre choice, and it���s a complete waste of the prize, in my opinion,��� he told Devex. ���I don���t think the World Food Program needs this money, and I really object to awarding prizes to people or organizations who are just doing their paid jobs.���

Apart from the fact that WFP���s raison d�����tre is to deliver food to vulnerable populations, and its staff are paid generously to deliver food aid, critics who know the food aid business have in the past pointed out that food aid is, in fact, detrimental in the long run because it suppresses local food production, making it harder for poor or conflict-ridden countries to feed themselves. In fact, studies have found that direct cash transfers are a much more efficient and effective method to alleviate hardship and improve the overall welfare of beneficiary communities.

A few years ago, none other than the European Union (EU)���s representative to Somalia, Georges-Marc Andr�� (now retired), admitted this to me when I was researching for my book War Crimes, which explores how foreign aid has negatively affected Somalia. He told me that United Nations agencies such as WFP might have actually ���slowed down��� Somalia���s recovery by focusing exclusively on food aid instead of supporting local farmers and markets. ���The EU is against food aid that substitutes local food production,��� he said.

His views are also shared by Michael Maren, a former food aid monitor for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in Somalia, whose book, The Road to Hell: The Ravaging Effects of Foreign Aid and International Charity, chronicles how aid became a political tool in Somalia that was manipulated by both the donors and the recipient country. Maren, who lived and worked in Somalia in the 1980s, believes that food aid to Somalia may have actually prolonged the civil war in the country. ���I had learned to view development aid with skepticism, a skill I had hoped to put to good use to help ensure that aid projects, at worst, didn���t hurt people. But Somalia added a whole new dimension to my view of the aid business. My experience there made me see that aid could be worse than incompetent and inadvertently destructive. It could be positively evil,��� he wrote.

In his book, Maren quotes a former civil servant working for Somalia���s National Refugee Commission during President Siad Barre���s regime who told him that traditionally, Somalis never relied on food aid, even during droughts. There was a credit system; pastoralists would come to urban areas where they would take out loans that they would repay when things returned to normal. Aid essentially destroyed a centuries-old system that built resilience and sustained communities during periods of hardship.

Food aid hurts local farmers

Food aid also suppresses local food production. Many Somali farmers have reported that NGOs working with WFP are notorious for bringing in food aid just before the harvest, which brings down the price of local food. They have also complained that the food aid is imported, rather than bought locally. At the height of the famine in Somalia in 2011 (which many believe was exaggerated by the UN), for example, WFP bought food worth ��50 million from Glencore, a London-listed commodities trader, despite a pledge by the UN���s food agency that it would buy food from ���very poor farmers who suffer because they are not connected to local markets.���

Let us be clear about one thing���food aid is big business and extremely beneficial to those donating it. (���Somebody always gets rich off a famine,��� Maren told Might Magazine in 1997.) Under current United States law, for instance, almost all US food aid (worth billions of dollars) must be purchased in the US and at least half of it must be transported on US-flagged vessels.

Most of this food aid is actually surplus food that Americans can���t consume domestically. Under the US government���s Food for Peace program (formerly known as Public Law 480), the US government is allowed to sell or donate US food surpluses in order to alleviate hunger in other countries. Famines in other countries are, therefore, very profitable to the US government and to highly subsidized American farmers, who benefit from federal government commodity price guarantees. (Interestingly, since 1992, all WFP Executive Directors have been US citizens. This could be because the US is the largest contributor to WFP, but it could also be that the Executive Director of the UN���s food agency is expected to promote US policies regarding food aid.)

In a 1988 paper titled ���How American Food Aid Keeps the Third World Hungry,��� Juliana Geran described Food for Peace as ���the most harmful programs of aid to Third World countries,��� and urged the US government to discontinue it. She noted that US food aid often distorts local markets and disrupts agricultural activity in recipient countries.

For example, massive dumping of wheat in India in the 1950s and ���60s disrupted India���s agriculture. In 1982, Peru ���begged��� the US Department of Agriculture not to send any more rice to the country as it was feared that the rice would glut the local market and drive down food prices for farmers who were already struggling. ���But the US rice lobby turned up the heat on Washington and the Peruvian government was told that it could either take the rice or receive no food at all,��� wrote Geran.

But what happened in Guatemala was truly catastrophic, as Geran narrates: ���In 1976, an earthquake hit Guatemala, killing 23,000 people and leaving over a million homeless. Just prior to the disaster, the country had harvested one of the largest wheat crops on record, and food was plentiful. As earthquake relief, the US rushed 27,000 metric tons of wheat to Guatemala. The US gift knocked the bottom out of the local grain markets and depressed food prices so much that it was harder for villagers to recover. The Guatemalan government ultimately barred the import of more basic grains.���

Stealing food to aid militias

One of the most evident distortions caused by food aid (apart from the fact that farmers have no incentive to grow food when the market is flooded with free food) is the temptation to steal it. There have been reports of blatant theft of food aid under the not-so-watchful eyes of WFP. UN monitors have routinely reported the theft of food aid to Somalia, for example, but to no avail. In its 2010 report, for instance, the UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea reported that local NGOs (known in development circles as ���implementing partners���), WFP personnel and armed groups that controlled areas where food aid was being distributed were diverting up to half of the food. WFP vehemently denied these allegations, even though an Associated Press report the following year showed American, Japanese and Kuwaiti food aid being openly sold in Mogadishu���s markets.

It is also important to remember that WFP���s international staff usually do not distribute food directly in conflict or disaster zones; instead they hire local NGOs to do the work. Many of these NGOs are not vetted; in fact, in Somalia, some of them have even been linked to militias who act as ���gatekeepers,��� deciding who gets the aid and who doesn���t.

When Maren was in charge of monitoring food aid donated by the US government to refugees fleeing the Ogaden war of 1977-78, he found that about two-thirds of the food went missing. Trucks would arrive at the Mogadishu port, collect the food and disappear, never to be found again. Even when food arrived at the refugee camps, much of it would be stolen.

Aid thus became a profitable source of income for criminal elements within Somalia. And Siad Barre learned to exploit this well. In fact, Maren believes that international aid not only sustained the dictator���s regime but also facilitated the unraveling of Somali society.

The looting of aid continued even after Barre was ousted in 1991. Battles between warlords were won or lost depending on how much aid each warlord had access to. However, it was not just the warlords who profited from food aid; corrupt NGO cartels also benefited. Because many parts of Somalia were considered a no-go-zone by international humanitarian agencies, and therefore rendered inaccessible, enterprising Somalis formed NGOs that liaised with these agencies to provide humanitarian assistance and services on the ground. These businesses-cum-NGOs signed lucrative contracts with aid agencies; some controlled entire sectors of the aid industry, from transport to distribution. Others were run by warlords, who often diverted food aid, which was then sold openly in markets to fund their militias.

���By engaging with the warlords to ensure the delivery of aid, the United Nations and other actors only encouraged the spread of the conflict and the establishment of a thriving aid-based and black market economy,��� wrote political scientist Kate Seaman in Globalizing Somalia: Multilateral, International and Transactional Repercussions of Conflicts. ���In essence they became a party to the conflict, losing their neutrality and only serving to perpetuate the conflict by providing resources which were then manipulated by the multitude of armed groups operating within Somalia.���

When an international humanitarian agency comes in to provide food to starving people, bad governments are let off the hook, and are allowed to continue with their bad policies that can lead to more famines in the future. Internationalizing the responsibility of food security to UN institutions, international NGOs and foreign governments makes practically everyone across the globe a stakeholder in famine relief. ���The process of internationalization is the key to the appropriation of power by international institutions and the retreat from domestic accountability in famine-vulnerable countries,��� wrote Alex de Waal in his book Famine Crimes: Politics and the Disaster Relief Industry in Africa.

Bad management practices at WFP

If the Norwegian Nobel Committee had bothered to find out how WFP staff view the organization they work for, it might not have been so quick to award WFP the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize. Like at many UN agencies, senior staff at WFP have been accused of abusing their authority, an allegation that has tarnished this Rome-based agency���s reputation. A confidential internal WFP survey of staff attitudes (whose findings were first leaked to the Italian Insider, and then to other news organizations, such as Foreign Policy in October last year) found that 35% of the more than 8,000 WFP employees surveyed reported experiencing or witnessing some form of abuse of authority, the most typical being the granting of ���preferential treatment��� for recruitment to close associates.

���The senior leadership of the World Food Program���once one of the most highly regarded United Nations agencies���have abused their authority, committed or enabled harassment, discriminated against women and ethnic minorities, and retaliated against those who spoke up in protest,��� wrote Colum Lynch in Foreign Policy on October 8, 2019.

What was evident in the survey was that WFP, like the rest of the UN, is extremely hierarchical and authoritarian. Respondents admitted that senior managers ���aimed to further their own self-interest rather than the mission of WFP, and abuse their power to further themselves and their favorites.���

Moreover, 29% of those surveyed said they had witnessed some form of harassment, while 23% said they had encountered discrimination. Some 12% of staff said they had experienced some form of retaliation for speaking up about abusive practices (which is fairly common in the UN, where protection for whistleblowers is virtually non-existent, as I have illustrated here). An even more alarming finding was that 28 of the WFP employees interviewed had experienced ���rape, attempted rape or other sexual assault��� while working at the agency.

The results of the WFP survey (which was conducted by an independent management consultancy) are consistent with other UN surveys on staff attitudes and experiences. Results from a UN Staff Union survey conducted in 2018 in response to the #MeToo movement showed that sexual harassment made up about 16% of all forms of harassment at the UN; 44% of those surveyed said that they had experienced abuse of authority and 20% felt that they had experienced retaliation after reporting misconduct. The survey also found that a large number of staff members��� complaints were never investigated.

It is, therefore, difficult to understand why the Norwegian Nobel Committee found it fit to award WFP the Nobel Peace Prize, given that the UN���s food agency has failed to adhere to almost all best practices in human resources management, and has not done enough to protect those who report internal abuse or wrongdoing. Nor has WFP improved conditions for peace in conflict-affected countries or prevented the use of hunger as a weapon of war, as I have illustrated above.

What then could have motivated the Committee to award WFP the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize���apart from some misguided notion that what the world needs most right now is food hand-outs? In a world that is being ravaged by the coronavirus pandemic, increasing xenophobia, racism and sexism, a global recession and climate change (all of which threaten peace and security), couldn���t the Committee have picked a more worthy candidate?

October 22, 2020

Identity and displacement in Nigeria

Still from The Lost Okoroshi

Masquerades today are seen as emblems of certain cultural festivals, but in pre-colonial Igbo society, they were part of the sociopolitical makeup and had duties that included acting as law enforcement agents. The onslaught of Christianity and Western civilization did not only demonize the masquerade tradition, but also denigrated it.

One of these is the Owu-Okoroshi masquerade society of the people of Oguta, in Nigeria���s Imo State.

In her 1994 documentary film, Owu: Chidi Joins the Okoroshi Secret Society, Sabine Jell-Bahlsen had an Igbo elder and griot narrate this legend. A woman named Ojeru goes fishing in a stream only to come up with an Ofo, a staff that is the Igbo symbol of truth and justice. Her husband Okonya consults Otugwa, a diviner, who informs him that the Ofo is the Owu and instructs him to prepare the Owu masquerade, in order to bring him wealth. When the Owu gains popularity in the community, Ojeru���s father Akunegbu contends with her husband over the ownership of the Owu, since the discoverer was his daughter. The case is settled when the community reminds Akunegbu that the husband had paid for his daughter���s bride price and now owns the woman and all that she possesses.

Director Abba T. Makama���s striking surrealist sophomore feature The Lost Okoroshi, which was first released in 2019, fictionalizes this legend. Makama���s film is also a satirical critique of modernity and its degradation of cultural traditions and practices. Makama debunks Western-influenced misconceptions of traditional masquerades, presenting ancestral spirits as superheroes who shouldn���t be feared but venerated.

His protagonist, Raymond Obinwa (Seun Ajayi), a man disenchanted with city life, is plagued by recurring dreams of masquerades dancing and chasing him. When he speaks to an elderly friend, Okonkwo (Chiwetalu Agu), about the dreams, he���s advised to welcome the masquerades���that they are spirits of the ancestors (in fact, the Igbo word for Masquerade, Mmanwu, loosely translates to spirit of the dead/ancestor) who bear good fortune. On the surface, this is the film���s thematic message, but it goes far deeper than that.

Through animated illustration and narration by Okonkwo, the legend of the masquerade is retold. The Okoroshi is presented as an ancestral spirit of the Igbo people who bears fortune for the good and bad luck for the wicked. In Makama���s exploration of this, Raymond transforms into the terrifying Okoroshi, and we see him perform the cultural duties of the masquerade���punishing a thief and being financially generous with a sex worker.

Still from The Lost Okoroshi

Still from The Lost OkoroshiMasquerades do not exist in isolation in Igbo culture. The Owu masquerade is part of a sophisticated institution known as the Owu-Okoroshi Secret Society, whose ranking of members has the Osere, the gang of leaders, at the top. And at the bottom of the hierarchy are the Okoroshi���young boys who are initiated into adulthood during the New Year festival. It is the initiated Okoroshi who act as law enforcers of the community���exposing and punishing evildoers. In The Lost Okoroshi, Makama takes creative liberties and merges the duality of the Owu masquerade and the Okoroshi of the Owu-Okoroshi Secret Society, portraying the Okoroshi as a masquerade on its own and having his young protagonist transmogrify into the masquerade, rather than be initiated into the Society.

Just as in the Owu-Okoroshi legend, there���s a contention over who or where the masquerade belongs in the film. In the legend, Ojeru���s father and husband contested the ownership of the masquerade by virtue of their relationship with her. While this raises questions about the displacement of women in the Igbo patriarchal society���being torn between their patrilineal and matrimonial identities���Makama���s film takes up a different conversation: the identity of the Igbo or any Nigerian in an ethnocentric Nigeria.

The Okoroshi having appeared in Lagos, a secret society, IPSSHRR, dedicated to the restoration of Igbo culture, claims ownership of it and soon gets into a heated argument over where it belongs. One member believes that the Okoroshi should be returned to its ancestral home in Igboland. Another asserts the masquerade’s right to remain in Lagos, stating that its appearance in the city was divine and ordained by the ancestors, and insisting that ���any land where a whole community of Igbo people have gathered, is Igboland.���

The subliminal message passed in that scene can be understood by many Igbo people. The Igbo are by far Nigeria���s most migratory group, settling and doing business in communities and towns all over Nigeria and beyond. This kind of industriousness has often been met with sentiments that allude to an Igbo domination of Nigeria. The IPPSHRR vice president���s suggestion ���let the masquerade return to the east��� becomes symbolic of the recent fervent calls for many Igbo people in the diaspora to return home and contribute to the development of Igboland. But Makama���s larger argument in that scene is that land and boundaries are essentially a social construct, and people should belong where they exist.

The conversation becomes ambiguous when you consider that Raymond, prior to his transmogrification, was psychologically displaced living in Lagos: he preferred the agrarian life in the countryside. As an ancient Igbo masquerade in Lagos, it became a question of geographical displacement. The metaphoric destruction of the Okoroshi, by a band of touts, lays bare the film���s main concern: the spiritual-cultural displacement in the Nigerian urban setting that has enabled the debasing of spiritual-cultural traditions. One wonders if the Okoroshi would have survived, had it been returned to its ancestral enclave in Igboland, a little more removed from the evils and demerits of modernity.

Identity and displacement in Makama’s ‘The Lost Okoroshi’

Still from The Lost Okoroshi

Masquerades today are seen as emblems of certain cultural festivals, but in pre-colonial Igbo society, they were part of the sociopolitical makeup and had duties that included acting as law enforcement agents. The onslaught of Christianity and Western civilization did not only demonize the masquerade tradition, but also denigrated it.

One of these is the Owu-Okoroshi masquerade society of the people of Oguta, in Nigeria���s Imo State.

In her 1994 documentary film, Owu: Chidi Joins the Okoroshi Secret Society, Sabine Jell-Bahlsen had an Igbo elder and griot narrate this legend. A woman named Ojeru goes fishing in a stream only to come up with an Ofo, a staff that is the Igbo symbol of truth and justice. Her husband Okonya consults Otugwa, a diviner, who informs him that the Ofo is the Owu and instructs him to prepare the Owu masquerade, in order to bring him wealth. When the Owu gains popularity in the community, Ojeru���s father Akunegbu contends with her husband over the ownership of the Owu, since the discoverer was his daughter. The case is settled when the community reminds Akunegbu that the husband had paid for his daughter���s bride price and now owns the woman and all that she possesses.

Director Abba T. Makama���s striking surrealist sophomore feature The Lost Okoroshi, which was first released in 2019, fictionalizes this legend. Makama���s film is also a satirical critique of modernity and its degradation of cultural traditions and practices. Makama debunks Western-influenced misconceptions of traditional masquerades, presenting ancestral spirits as superheroes who shouldn���t be feared but venerated.

His protagonist, Raymond Obinwa (Seun Ajayi), a man disenchanted with city life, is plagued by recurring dreams of masquerades dancing and chasing him. When he speaks to an elderly friend, Okonkwo (Chiwetalu Agu), about the dreams, he���s advised to welcome the masquerades���that they are spirits of the ancestors (in fact, the Igbo word for Masquerade, Mmanwu, loosely translates to spirit of the dead/ancestor) who bear good fortune. On the surface, this is the film���s thematic message, but it goes far deeper than that.

Through animated illustration and narration by Okonkwo, the legend of the masquerade is retold. The Okoroshi is presented as an ancestral spirit of the Igbo people who bears fortune for the good and bad luck for the wicked. In Makama���s exploration of this, Raymond transforms into the terrifying Okoroshi, and we see him perform the cultural duties of the masquerade���punishing a thief and being financially generous with a sex worker.

Still from The Lost Okoroshi

Still from The Lost OkoroshiMasquerades do not exist in isolation in Igbo culture. The Owu masquerade is part of a sophisticated institution known as the Owu-Okoroshi Secret Society, whose ranking of members has the Osere, the gang of leaders, at the top. And at the bottom of the hierarchy are the Okoroshi���young boys who are initiated into adulthood during the New Year festival. It is the initiated Okoroshi who act as law enforcers of the community���exposing and punishing evildoers. In The Lost Okoroshi, Makama takes creative liberties and merges the duality of the Owu masquerade and the Okoroshi of the Owu-Okoroshi Secret Society, portraying the Okoroshi as a masquerade on its own and having his young protagonist transmogrify into the masquerade, rather than be initiated into the Society.

Just as in the Owu-Okoroshi legend, there���s a contention over who or where the masquerade belongs in the film. In the legend, Ojeru���s father and husband contested the ownership of the masquerade by virtue of their relationship with her. While this raises questions about the displacement of women in the Igbo patriarchal society���being torn between their patrilineal and matrimonial identities���Makama���s film takes up a different conversation: the identity of the Igbo or any Nigerian in an ethnocentric Nigeria.

The Okoroshi having appeared in Lagos, a secret society, IPSSHRR, dedicated to the restoration of Igbo culture, claims ownership of it and soon gets into a heated argument over where it belongs. One member believes that the Okoroshi should be returned to its ancestral home in Igboland. Another asserts the masquerade’s right to remain in Lagos, stating that its appearance in the city was divine and ordained by the ancestors, and insisting that ���any land where a whole community of Igbo people have gathered, is Igboland.���

The subliminal message passed in that scene can be understood by many Igbo people. The Igbo are by far Nigeria���s most migratory group, settling and doing business in communities and towns all over Nigeria and beyond. This kind of industriousness has often been met with sentiments that allude to an Igbo domination of Nigeria. The IPPSHRR vice president���s suggestion ���let the masquerade return to the east��� becomes symbolic of the recent fervent calls for many Igbo people in the diaspora to return home and contribute to the development of Igboland. But Makama���s larger argument in that scene is that land and boundaries are essentially a social construct, and people should belong where they exist.

The conversation becomes ambiguous when you consider that Raymond, prior to his transmogrification, was psychologically displaced living in Lagos: he preferred the agrarian life in the countryside. As an ancient Igbo masquerade in Lagos, it became a question of geographical displacement. The metaphoric destruction of the Okoroshi, by a band of touts, lays bare the film���s main concern: the spiritual-cultural displacement in the Nigerian urban setting that has enabled the debasing of spiritual-cultural traditions. One wonders if the Okoroshi would have survived, had it been returned to its ancestral enclave in Igboland, a little more removed from the evils and demerits of modernity.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers