Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 153

October 22, 2020

Refugee debates have an African history problem

Photo by Ninno JackJr on Unsplash

The relationship between refugees and history is a paradox. On the one hand, historical knowledge is valuable for understanding refugees and for supporting displaced people pursuing desired futures. On the other hand, national governments, United Nations bodies, and humanitarian agencies present the global ���refugee problem��� as if it could be solved through proper management of an international system���and without historical knowledge of refugees. Even the academic field of refugee studies tends to focus on information required to manage refugees rather than on understanding the circumstances that have compelled specific people to migrate across international borders, or the construction of ���the refugee��� as a powerful term for categorizing the displaced.

African history has been especially neglected in debates about refugees. For the past 60 years, much of the world���s refugee population has lived in, and hailed from, the African continent. Nevertheless, Africans remain at the periphery of global refugee debates, repeatedly reduced to stereotypes that present refugees either as victims or threats. With attention focused heavily on the refugee politics of Western host nations, the biological needs of refugees, and the biopolitics of refugee management, Africans��� unique histories of displacement and of hosting the displaced are regularly overlooked, seemingly insignificant to know.

Nevertheless, as a marginal but growing body of scholarship attests, refugee history matters���especially histories of Africans seeking refuge in and beyond the continent. Anthropologist Liisa Malkki made this point poignantly 25 years ago, drawing from her now classic ethnography of Burundian Hutu refugees in Tanzania, to call for a ���radically historicizing��� approach to refugees. Since then, other anthropologists have followed suit, offering detailed studies of life in refugee camps and of the significance of historical knowledge among displaced people. More recently, historians have also contributed to this field, tracing Africans seeking refuge before, during, and since European colonization. Moreover, historians have highlighted the development of the international refugee regime, noting that, during the 1960s and 1970s, Africans fit awkwardly within international refugee law and often defied dominant global expectations of what it meant to be a refugee.

Of recent work on these topics, Bonny Ibhawoh���s stands out. In his contribution to the latest issue of African Studies Review (ASR), Ibhawoh writes about the Nigeria-Biafra War and 4,000 children whom relief agencies airlifted from Biafra to Gabon and Cote d���Ivoire in 1968���and whom the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) partially repatriated two years later. As he explains, there was little precedent for the UNHCR in determining refugee status and managing repatriation in Africa before the Biafran crisis. Ibhawoh���s research, therefore, highlights how the global humanitarian discourse surrounding refugees began to emerge, allowing for a critical perspective on now taken for granted norms and practices.

My own work points to the value of biographical research with individuals who were refugees during Southern Africa���s liberation struggles. In my contribution to ASR, I focus on Mawazo Nakadhilu, a refugee born in 1972 to a Tanzanian mother and a Namibian father affiliated with the South West Africa People���s Organization (SWAPO). Mawazo lived with her mother���s family until 1983, when SWAPO first relocated her to a camp in Zambia and later ���repatriated��� her to Namibia just prior to the country���s political independence in 1990. As I emphasize, these circumstances have undermined the ability of Mawazo and other ���struggle children��� to make homes���a significant social issue overlooked in scholarship on exiled nationalist movements, but clearly visible when viewing the lives of individual exiles/refugees.

Other scholarship just published in ASR focuses on Africans displaced over the past two decades, and how their experiences relate to longer histories and contemporary narratives of displacement. For example, Duduzile Ndlovu���s research examines displaced Zimbabweans now living in Johannesburg and how they narrate the Gukurahundi���violence that the Zimbabwean government perpetrated on its own citizens in Matabeleland from 1981 to 1987. As Ndlovu emphasizes, attending to how displaced Zimbabweans narrate the past in the present is largely superfluous to refugee literature, but crucial to grasping the legacies of Zimbabweans��� and other displaced people���s experiences.

Marten Bedert draws our attention to the experiences of refugees from Cote d���Ivoire living in Liberia between 2011 and 2013 in the aftermath of Cote d���Ivoire���s contested 2010 elections. As he highlights, ���refugees��� tend to be stigmatized in long-standing relationships between ���landlords��� and ���strangers��� in this region, because the label ���refugee��� undermines Ivoirians from being accepted as strangers by their Liberian hosts. By drawing our attention to deep histories of cross-border migration and ethnographic research with individual refugees, Bedert tracks issues that refugees face in host communities that are overlooked by programs aimed at refugee management.

Finally, Katherine Luongo discusses Africans seeking refuge outside the continent, focusing on individuals applying for political asylum in Canada and Australia on the premise that they are ���perceived witchcraft practitioners��� or ���victims of witchcraft.��� As she emphasizes, despite significant policy differences, both countries are similarly incapable of evaluating the risks of witchcraft-related violence among asylum seekers because of immigration officials��� insufficient knowledge of the contexts in which the applications are framed and general incredulity towards witchcraft. It follows that these officials should appeal to relevant expertise, including historical expertise, so that they may apply the UN Convention more justly to such asylum seekers.

As each of these studies suggests, addressing refugee issues today requires first seeing that the debates surrounding these issues have an African history problem, and then working, both carefully and urgently to address this matter.

October 21, 2020

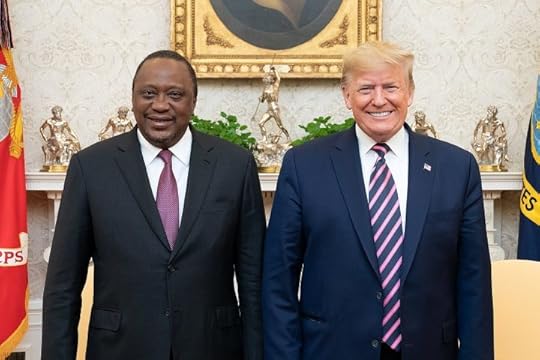

Uhuru Kenyatta can���t have his cake and eat it too

Official White House Photo by Tia Dufour via Wikimedia Commons.

For months now, Kenya has been negotiating a bilateral trade deal with the United States and the United Kingdom. Kenya���s approach to go it alone, if successful, will derail the pursuit of the ongoing Pan-African continental economic integration plan���spearheaded by the still nascent Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The operationalization of AfCFTA, which was meant for July 2020, has now been pushed to December due to the inconveniences caused by COVID-19.

It is not surprising that the US and UK have chosen Kenya as the launching pad for their efforts at undermining Africa���s economic integration, as indicated by the US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer. According to Lighthizer, a successful trade agreement with Kenya will set the pace for similar bilateral trade agreements with other African countries. Of course, these are more likely to serve US interests at the expense of potential regional public goods as promised by the implementation of AfCTA.

Then there���s Kenya���s ruling elites, currently represented by President Uhuru Kenyatta, who have historically wavered when it comes to continental cause. Successive ruling elites in post-colonial Kenya have continually put their own commercial and economic interests first. Those interests just happen to dovetail with the West���s capitalist and imperialist agenda. There is no better indication of this than Kenya���s ���fence sitting��� policy during the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. Indeed, contrary to collective and majority continental aspirations, at the height of the struggle, Kenya continued to maintain more than cordial, albeit covert, diplomatic, and economic relations with the apartheid regime.

The greed of Kenya���s ruling elites and their cronies was best captured by Mwalimu Nyerere, Tanzania���s first president, in the 1970s, when he described Kenya as ���… a man eat man society.��� There is no better indication of this than the fact that the current leadership in Kenya is made up of individuals whose personal interests run through virtually every sector of the country���s economy. Thus, the interests of the elites, at times, might erroneously pass as Kenyan aspirations. It is on the basis of this strong link between Kenya���s ruling elites and Western capitalist interests that the unilateral action of Kenya needs to be analyzed. US President Donald Trump, after all, said to African leaders, that ���Africa has tremendous business potential. I���ve so many friends going to your countries, trying to get rich.���

In the ongoing trade negotiations between Kenya and the US, the key concern for Kenyan officials is the US���s non-commitment to renew the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) post-2025, when the deal expires. While this might seem like Kenya protecting its national interest, by all indications it is reckless and short sighted. First, the AGOA initiative is a fickle unilateral trade deal that can be withdrawn at any time. The admission into AGOA���formed in 2000 and providing select African countries with access to US markets for assorted duty-free exports���depends on terms and conditions provided by the US. In most cases, this access is based on US judgement of the level of market liberalization, or its own skewed measure of democratic governance of any particular African country. Such ���benevolent��� unilateral trade packages should not feature in the core policy preferences for a country or continent that seeks to develop its industrial and manufacturing base for long term, inclusive economic growth and development. At the very least, and in anticipation of the demise of the AGOA trade deal in 2025, Kenya should have fronted a more collective bargaining agreement with the US, involving all 39 countries that that are signatories to the agreement.

Although Kenya has vaguely reaffirmed its commitment to regional integration, there is no doubt that any successful effort or outcome of the bilateral negotiation between Kenya and the US will stifle the AfCFTA���s noble, though still infantile, approach to continental economic integration. The prospects of AfCFTA, as opposed to bilateral trade deals, potentially provides better leverage for negotiations around trade deals. This is due to its capacity to ensure efficient facilitation of trade through institutionalizing policy measures on tariff and non-tariff barriers that will guide how Africa conducts trade with external actors. In this regard, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa projects that AfCFTA, with strong political will from African governments, has the capacity to increase intra-Africa trade up to 15%-25% by 2040 through elimination of tariff barriers. This is significant given the fact that one of the major drawbacks to intra-African trade is import levies by countries within the continent.

Furthermore, AfCFTA, though still at an early stage, promises a more beneficial multilateral platform for trade deals within and outside the continent, when compared to Africa���s smaller, fragmented, and insignificant economies negotiating unilateral trade deals with major global economic players such as the US, China, or the EU. On a continental scale alone, AfCFTA promises a wider continental market of more than 1.2 billion people and a gross domestic product of more than $2.5 trillion. The potential benefits of AfCFTA thus outweigh the current Kenya and US trade volume���an average of $ 1 billion annually. AfCFTA is a more effective guarantor of Kenya���s economic success. So, instead of adopting a myopic approach toward a trade deal with the US, Kenya should rather roll up its sleeves and get ready to engage in the collective, though painstaking, task of actualizing the economic integration of Africa.

If the US���s bid to get Kenya to renege on its 2017 plastic bag ban is an indicator of what may be at stake in the proposed Kenya-US bilateral agreement, as was leaked to the public a few months ago, then Kenyans need to be vigilant and question the necessity of this process. Ultimately, the success of any future agreements requires strong political will that prioritizes the interests of the majority of Africa���s citizens, rather than those of ruling elites and their Western capitalist benefactors.

The academic game

Photo by Edwin Andrade on Unsplash

Writing from the perspective of an island, continents are vast entities with enough space for loneliness and separation.

The world has been mapped such that the journeys between continents are almost ignored���more so the spaces within the oceans of rest, recuperation, and succor.

But currents still link the continents, and the islands between them are critical beads on the chains that bind us. Long distance transportation of goods, ideas, people, and even rats requires knowing islands, and working with/on/against/in/through them. Shipping highways marked onto the sea by traces of oil left in passing wakes.

The industrial machine has been laid upon oceanic surfaces. Vast worlds beneath an echo, sonar, imagination. Internet cables below, marine peons on tight delivery schedules above.

How do we reflect ���Africa��� from here? Mirror, mirage, line on a map, that which is below Mauritius on the Tables of Bureaucratic Development. Point of Departure for some. Point of Arrival for all. Slavery. Indenture. Tax Haven.

���Academic study is like adding one grain of knowledge-rice to the meal of human reference.��� I repeat received wisdom sagely to a graduating student. ���The bowl is all wrong��� was the dry response. She left my office and went to lead a Fridays for the Future march���islands are vulnerable to climate change, and so is Africa.

The bowl is all wrong

After centuries of African Studies that have coincided with slavery, colonialism, the trading of bibles for gold, should we not examine the bowl of our own knowing? What is its shape, materiality, the contours of inside and out, the boundaries of food versus poison? How is it possible that the bowl is still manifest as singular in form���not gourd, not pot, not Coca-Cola-offcut or radiant banana leaf?

How do we reconcile a world where those with currencies forged in plunder still decide what questions are important? Where the gatekeepers of knowledge are often starkly other to the continent?�� Where promotion depends on publication in pay-walled journals that require networks���human, material���to access or be let into? Where often the ���African University��� means only University of the Witwatersrand or the University of Cape Town.

More than that, that international borders are not permeable in both directions? That Zoom only kept the world going because it was going before (how many of us have gasped at our own non-essentialism now).

That the Africans who for decades have educated Africans in African institutions are not perceived as global knowledge leaders unless they package their knowledge into bites that are palatable for occidental constitutions and their academic accounting systems. That knowledge is a rare earth mineral long mined without any compensation. That writing in area studies without attending to connection is like writing on islands and ignoring the sea.

Factories of insecurity

Universities as they stand were forged within extractivism. Neoliberalism has enabled their expansion to the point of blocking off alternative horizons. These are factories of insecurity, with deeply human underbellies. Scared of dismissal, academics write not to change the bowl, but to keep eating from it, to ensure it is not taken from our hands. To maintain our right to think in comfort. A glorious privilege, carefully guarded.

We write for the gatekeepers, to prove our own legitimacy, for the stimulation of conferences and the relief of rising recognition by algorithms. ORCID IDs. Hyperlinks (Please Cite Me!). Our writings are the grains of knowledge we add to pacify the data-driven beast, trail through the forest, proof of productivity while we ourselves consume���but what is the ratio?

Most of us would have liked to be storytellers, teachers, explorers, but there is little money, less status, and too much danger in those roles. Yet, we cannot make new maps of the world���literal or metaphoric���if our job security depends on never questioning the bowl.

Instead we make lists, tick them off, categorize, organize, produce. Lists are more stable on land. Again, we usually do not think about the currents of connection.

Who do we love, and where will we go to die?

On a burning planet, these are the critical questions: who do we love, and where will we go to die? How much should we care about hits on virtual accounting systems, when faced with fire and flood?

How many authors of seminal texts wish to die in the places that have enabled their careers? Are the skins we are seen in to be treated as shrouds, or are they political manifestos, flags, flagellations, flesh, points of encounter? What of callouses on the hands? Languages spoken in dreams?

Curiosity is not enough. We have moved into an era where the questions of bones become the questions we must address.

Love and death. It will show a new map. . On this map of dreams of death by Most Cited Scholars of Africa, ���the continent��� will be an emptiness of Conradian proportions, the oceans drawn with the trail of invisible carbon cast by jumbo jets. Why is this so?

Expertise without love is a hollow straw with a very high carbon footprint.

Like this, the bowl will not change.

Who will mourn us?

When we lay down our bones, we Area Studies Scholars, who will mourn us?

Who will be the people who pause in their tracks to say, ���That ��� was a life well lived���? Where will they be geographically located, where will they gather? What traces will we have left that others may follow when we know for sure once again that flying is a dream only for princes? Which rare earth minerals did we mine from the seams of human knowledge, and who shared the dividends? Have we told stories that expand empathy? Have we enabled care?

Will the ancestors welcome us?

When we die, will the ancestors���fictive, intellectual, of blood���welcome us? Will they be proud?

Are we visible to the ancestors in the places we have described, or will we become but ghosts on the surface disturbing in the afterlife what we interrupted in this one?

What do maps look like when they are drawn by ghosts?

What must we now do?

How might we draw in flesh and spirit and manifold complexity? Can we now expand relationality to allow a deeper presence?

To chart new maps we will require a different way of seeing, different reference points on a compass made with a different goal. As we tip the angle, tilt the frame, turn over the bowl, we will have to write for an audience of living ancestors, and not of ghosts.

We will have to speak in a way that is audible, not whispered at the margins. And we will have to teach in a way that enables a world that we cannot yet imagine, based on structures we have yet to conceive.

Note: This was solicited as a journal article for a special edition in an area studies journal within a former colonial power, which had the goal of reframing/rethinking/reimagining the field of African Studies. The journal got skittery because to talk the talk, one has to walk the walk, and too much attention there could be a little uncomfortable, possibly awkward, possibly a PR nightmare. That it is being published here is precisely the point of my intervention: in scholarship, if one wants to not trip, nor tip, but simply take a close look at the fruit cart, the preference is generally that this be done outside the village gates and preferably also without the farmer present.

October 20, 2020

Lagos gone to seed

Promotional still from ��l��t��r��.

Almost a year after Nigerian film director Kenneth Gyang���s ��l��t��r����(2019) premiered as part of the ���Nigeria Focus��� at the Carthage Film Festival in Tunis, it started streaming on Netflix as the company���s second Nigerian original film���this shortly after producer Mo Abudu and her EbonyLife Films entered a deal with Netflix to produce and distribute a slate of new content.

I suppose it makes perfect business sense for Abudu and her team to unload ��l��t��r����on a streaming platform at this time. The COVID-19 pandemic has essentially ground public screenings of films to a halt, and Nigeria is not exempt. Also, because ��l��t��r�����s subject matter is quite the tough one: Would Nigerian theatre audiences, already used to their cinema���s light and shiny packaging���credit to Abudu���have given a full-on embrace to a dark drama about sex work and sex trafficking? Especially under socially distanced conditions?

It is unclear what price Netflix paid to brand ��l��t��r����relative to the film���s budget, but it would seem that both parties emerged with some feeling of satisfaction. Netflix gets the kind of low-priced, quality-challenged work they consider perfect for���and of���Nollywood. EbonyLife Films explores alternative distribution channels. But what is in it for the rest of us?

Not a lot, sadly.

The title character, played by Sharon Ooja, is a spunky reporter who goes undercover to bust a nefarious sex work and human trafficking ring. She has more passion than good sense, though, and as events play out, isn���t quite equipped to compete in the high stakes world she is suddenly thrust in.

Na��ve and sloppy in ways that one wouldn���t expect from a journalist, Ooja���s ��l��t��r�� is also unwilling to cast her privilege aside. This results in dire consequences for people in her orbit, including at least one tragic ending. No one mentioned to ��l��t��r�� or the filmmakers (bless their bleeding hearts) that regardless of how ���important��� her story is, it remains a story and should never take precedence over the very real lives of the other victims.

In the film���s opening scene, ��l��t��r��, in character as the sex worker Ehi, takes a john away from Vanessa (Wofai Fada), a girl who could actually use the cash, only to proceed on an inexplicable escape mission. In another scene, ��l��t��r�����s clumsiness nearly derails another girl���s chances of moving to Europe when she trails her on a visit to a middleman. It is hard to root for the character because she is more ideal than person and doesn���t come alive on the screen beyond the broadest of strokes.

Ooja certainly has her limitations as an actor (she was last seen in February in the romantic comedy, Who���s the Boss?), but it would be unfair to place this disconnect squarely on her doorstep. The screenplay���credited to Yinka Ogun, a frequent EbonyLife Films collaborator on films like Your Excellency and The Royal Hibiscus Hotel and with Craig Freimond (Material, Jozi)���is a terrible beast, lacking nuance or depth. It plays like someone read a journalist���s account and proceeded to adapt it as a sociology document, accommodating all the major perils of the human trafficking trade but with none of the intelligence or discernment that would make it work for the big screen.

This do-gooder approach by privileged creatives and executives, who have failed to envision their project as a series of inter-linked personal and complex stories, is responsible for the pity porn dressing that covers the film. Sex trafficking is evil, yes, we get that. But what else is new or revealing about this? And how can this obvious-enough topic be told through a fresh lens?

��l��t��r�����s treatment of sex workers is far from progressive. It is uninteresting too. Just about all of the girls are victims. In many ways, indeed they are, but that is not the full picture, is it? The film wastes two characters that could have told a more respectful, nuanced story of the sex workers it so casually flaunts.

Omawumi���s Sandra, the madam who runs the brothel that ��l��t��r�� and her colleagues rent out, doesn���t get enough screen time, and when she does, she is reduced to a frustrated stereotype. Omoni Oboli���s Alero, a former international call girl herself, whose career has taken the successful madam route, has plenty of screen time. But neither actress nor screenplay can rise to the challenge of doing something complex with the arc.

When the film actually stumbles on an interesting observation���the redundancy of the conventional pimp���it has no way of working this subtly into the screenplay. Like other things with the film, this observation has to be screamed out���or, in this case, read out���for the audience, just in case you missed it the first time.

The loud tone that ��l��t��r�� adopts is quite uncomfortable. Director Kenneth Gyang, in a different rhythm from his previous work, dials it up to camp levels, perhaps to satisfy his producers. Which would be well and good if this campiness were intentional. Strangely, it isn���t. Everyone is so self-serious, involved in the righteousness of their project. The dissonance is almost laughable.

The actors are not believable because you can see every single one of them attempting to act. The effort is visible on their faces, in their body language, via the sticks of cigarette they burn through and from the reams and reams of dialogue they are saddled with. There is not one believable scene in the film.

Actually, scratch that: there is one. It arrives somewhere in the final act. Omowunmi Dada, who plays Linda, a sex worker trying to drag her family out of poverty, is ordered to practice her lap dance skills while participating in some form of forced boot camp. The camera pans on her face while she grinds slowly and the mixture of fear, sadness, shame, and determination is written so clearly���each emotion a desperate and silent cry for help. But she appears to be doing this work in spite of���not because of���the screenplay or the directing that she has been provided with.

Gyang���s previous films, the terrific duo of Confusion na Wa (2013) and The Lost Caf�� (2017), grappled with the relationship that young Nigerians have with their country, which makes him seem like a natural fit to tell this story. The reality is quite different. He struggles to establish himself in a drama that is essentially EbonyLife Film���s idea of what a prestige picture should be. The studio has the wrong impression, clearly, and Gyang, who really should know better, seems happy to go along with them.

Which isn���t to say that he doesn���t put in something of his own. The opening scene is a lengthy tracking shot that seems promising enough until the actors start talking. Take away all of that dialogue and the scene would probably be stronger for it.

For whatever reason, ��l��t��r�����s picture is far from flattering, despite all of the bright colors and detailed costuming. There is an argument to be made about depicting the ugliness that surrounds victims of sex trafficking, but the picture that Gyang���s ��l��t��r�� puts out is neither grit nor neorealism. It exists somewhere between Lagos gone to seed and the kind of gaudy prettiness that EbonyLife Films likes to serve. This mix is jarring and doesn���t work in this case.

As if attuned to the lack of depth in play, Gyang tries to compensate by dialing up the blood and gore. None of it works beyond the initial shock value. By the time the action shifts to a drone shot in a village where one character���s mother lives, you almost wish Gyang was making a different film entirely, one in which he feels more comfortable.

Despite the talent and big names involved, the trendy subject matter and socio-relevant themes, ��l��t��r�� does not rise to the artistic challenge, particularly as that was clearly the intention ab initio. Surprising, really, how so many can have their hearts in the right place and yet miss the mark so wildly.

The politics of influence

Photo by Steve Gale on Unsplash

The notion of ���the anxiety of influence,��� theorized in the 1970s by the conservative American literary critic Harold Bloom, now stands to be reconfigured as a means of contesting the same Western canon that Bloom worked so tirelessly to defend.

When it comes to Africa and the West, there is perhaps no better-known case of influence than that of Pablo Picasso. During the years leading up to and through the development of Cubism, Picasso first unexpectedly encountered, and then systematically studied and collected, a limited corpus of African sculptural objects. These diverse objects variously informed, among other works, Picasso���s landmark painting Les Demoiselles d���Avignon (1907), and his first three-dimensional Guitar (1912), a seemingly slapdash but equally groundbreaking constructed sculpture made of paperboard, twine, and adhesives.

Recent international debates have queried the status of African artworks displaced under colonial occupation, including those seen by Picasso in Paris. Meanwhile, a longer-running debate���and a more rarified one���has examined the status of 20th century African modernists, including their complex relationships to modernisms in the West.

As I argue in a new book, artistic influence carries its own political stakes, which are particularly relevant within institutional spaces where African cultures get represented: exhibitions, university curricula, the media, among others. This is what I���m calling ���the politics of influence.��� If influence didn���t have a politics, then people like Harold Bloom probably wouldn���t have bothered getting involved.

For African and modern art, one notorious Bloom-like figure was William Rubin, who in 1967 became curator at New York���s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The analogy to Bloom is not entirely apt, as the two men���s roles, tastes, and trajectories differed. One thing they certainly shared, though, was their own outsized anxieties about influence.

Rubin also shared this with his friend Picasso, who was infamously quoted in 1920 as saying, ���L���art n��gre? Connais pas!��� (���Black art? Never heard of it!���) Whether or not the Spanish artist ever actually uttered these words, the statement was tongue-in-cheek: Parisians already knew how much the artist was beholden to African and Oceanic sculpture, labeled in early 20th century France as ���art n��gre.��� Later Picasso disavowed ���Black��� influence much more cunningly, either by shifting attention toward ancient Iberian stone sculpture (another influence), or by referencing the perceived psycho-spiritual power of African objects. The artist never spoke directly of his formal appropriations.

Rubin would follow the painter���s lead. After organizing a giant Picasso retrospective at MoMA in 1980, the curator again made Picasso the protagonist of a blockbuster survey called ���’Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern” (1984). In principle, this exhibition set out to acknowledge modernist borrowings from so-called primitive or tribal art (a dubious category, carried over from the 19th century, encompassing indigenous material culture from Africa to the South Pacific and the Americas). In practice, Rubin and his collaborators downplayed non-Western formal influence at every turn.

They did this by using two key terms, ���primitivism��� and ���affinity,��� to frame European artists��� engagements with non-Western arts as chance encounters (not colonially determined ones), and then to reinscribe non-Western traditions as ���primitive��� (not modern). Within MoMA���s galleries, these rhetorical moves permitted the curators to misuse art history���s visually-based methods by arbitrarily juxtaposing modernist and so-called tribal pieces whose striking formal resemblances belied their historical incongruity: European artists had not necessarily seen the particular ���tribal��� works on display. This rendered the whole question of influence as moot. Modernist debts became mystical ���affinities,��� while non-Western contexts were summarily dismissed, quite ironically, as irrelevant to questions of form.

None of this went over well in 1984. Edward Said had already published Orientalism, and critics were increasingly attuned to the erasures of indigenous cultures and colonial legacies that routinely took place under cover of modernism. ���Primitivism,��� which was widely scorned, marked an art-historical turning point���a critical shift toward postcolonialism.

What surprised me in the 2010s, as I was researching my book, was the way the post-1984 generation ended up regarding African sculptural influence as: 1) vitally important, especially for dismantling persistent notions of Western cultural supremacy and originality; but also as 2) a foregone conclusion, such that Rubin���s method of arbitrary formal comparison would perpetually return. Although ���primitivism��� had failed, the exhibition���s formalist methodology triumphed, and the conceptual framework of ���primitivism��� was retrofitted in the image of Orientalism, albeit with a crucial difference. Whereas Said���s Orientalism would mutate in the work of later scholars, ���primitivism��� seemed hardly to depart from Said���s original schema, portraying colonialism as a neat oppositional binary wherein only the colonizer ever commands power and attention.

My own work responds to this state of affairs by carefully documenting the presence of African sculptural elements within modernism, and by equally prioritizing considerations of Afro-modernist engagements with African canonical sculpture. Throughout the book���s trajectory���from the Fauves and Picasso to the Harlem Renaissance, and from the work of South African artist Ernest Mancoba to Negritude and the ��cole de Dakar���African sculptural influence re-emerges as both eminently knowable and globally significant.

To assail the nagging category of ���primitive��� art, the book���s research highlights the tumultuous conditions of African colonial modernity under which certain influential African sculptural objects came into being and credits the agency of African cultural producers within those contexts.

The book also aims to modify accounts of African and diaspora modernisms wherever they risk reformulating colonial-era expectations of either authentic ���native��� autonomy or hopelessly compromised cultural assimilation. It takes Afro-modernist appropriative practices as sites of double-citation���referencing both African sculptural works and the ghosts of Europe���s avant-gardes���in which African and diaspora artists ultimately manage to snatch ���influence��� away from its presumptive associations with complete unoriginality, and convert it, instead, into something to be actively negotiated and strategically entertained.

October 19, 2020

Like an infant in a suffocating hold

Protest in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Image credit Fibonacci Blue via Wikimedia Commons.

Lum and several other women lay restless on a haphazard boat headed on a treacherous pilgrimage through the New World. The year is 2019, not to be confused with 1619, and Cameroonian women are crossing a lake into Panama. From Panama, they hope to trek on foot and bus to the southern border of the United States of America. Lum, whose name I have changed to protect her identity, began this trip in June 2019 in Cameroon with a borrowed airplane ticket to Ecuador, a warning, and a glimmering possibility of hope.

From Ecuador, she reached Pasto, Columbia, then Medellin, before moving onward to Panama, where she began a two-week trek through the forest by foot. Lum contracted malaria in Panama, and shuffled between three different immigrations camps, set up like refugee stations for the wanderers: Camp One, Camp Two, and Camp Three. From Camp Three in Panama, Lum was back on the road, this time through Central America to Tapachula, Mexico. It was here that the American ordeal began with a stack of paperwork and bureaucracy that marked the beginning of a long and arduous journey.

The stories of Black immigrants depict a vivid image of unimaginable anti-Blackness through foreign terrain, and a systematic dehumanization and degradation of Black life that permeates every aspect of migration.

Lum had nowhere to go but knew with the utmost certainty that she had to leave Cameroon. When a civil war broke out in 2018, Lum, who was 16 years old at the time, had to drop out of school. That same year, Lum was arrested for six days by a rampaging military committed to destruction in the service of power. The Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon have been in the midst of an intense civil war for the last three years in a conflict that traces its origins to early 20th century European colonization, when the German-occupied territory was divided up between the British and French after World War I. The road to independence was mired with strife, rising nationalisms, and an unwavering faith in self-determination. Tensions have escalated into the current crisis between the Francophone Cameroonian government and English-speaking factions calling for an independent Anglophone state. This continued violent conflict has resulted in tremendous devastation and forced many Cameroonians to flee their homeland. The violence in Cameroon has now claimed more than 3,000 lives and displaced more than 500,000 people according to the International Crisis Group. The crisis has further compelled another 40,000 to flee to Nigeria and deprived more than 700,000 children of education.

Now, at 19, the threats and intimidation directed towards Lum���s life were visibly lethal and escalating. Military officials began to intimidate her and her family by asking her neighbors for Lum���s whereabouts. She fled to Ecuador with three thousand dollars, having heard from her older sister that Ecuador did not require a visa. From Ecuador, she would mount into the womb of American possibility like an infant in a suffocating hold.

My path crossed Lum���s unexpectedly. After her month-long trek across South and Central America, Lum was held in a US ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) detention center in Mississippi���just as the COVID-19 global pandemic began to ravish detention centers, jails, and prisons across this country. As an attorney and Bertha Justice Fellow at the Center for Constitutional Rights, I worked alongside a team of devoted attorneys and advocates to represent medically vulnerable people held by ICE across the deep South. We filed petitions for the release of our clients, arguing that continued detention put our clients at risk of contracting the coronavirus and developing life-threatening COVID-19 symptoms, or worse. This was part of a larger effort to expose the inhumane conditions in detention centers, prisons and jails across the country.

Then Sylvie Bello of the Cameroonian American Council came to legal and advocacy organizations with an urgent call: justice for the detained Cameroonians who were protesting the conditions of their detention. Informed by calls from Sylvie and others, our legal team began interviewing immunocompromised Cameroonians in ICE detention at risk of serious injury or death should they contract COVID-19, which is how I met Lum in March of 2020. We spoke on the phone, often at odd times as it was difficult for us to call her and relied heavily on her availability. She was a prospective client in our suit when I heard her story. She was a reserved young woman who spoke with clarity. She informed me of her conditions in detention, of her life before fleeing Cameroon, and her hopes for coming to America. She told me she came to America through harrowing terrain.

I then spoke to another client, who repeated���almost verbatim���Lum���s itinerary. Then another. Lum was not alone. She was one of thousands making the journey from Africa to South America, and eventually to the US. It was not too long ago that I was a stranger to this country myself, flown out of my birthplace knowing little about where I was headed. I was 19��� Lum���s age���when I was naturalized, simultaneously pledging an oath to my newfound home while struggling to confront the expansive gap between nationality and citizenship. Perhaps it was because of this that meeting Lum left me breathless.

Our work together was no easy feat. The American justice system is not amenable to freedom.

Our cases were at the mercy of appointed judges, doctrines, and procedural postures that proved time and time again to be incapable of articulating a liberatory vision for Black women.

I could not imagine this terrain, this harrowing journey through the unknown and known of anti-Blackness. Lum and the scores of people we spoke to in detention were only several of thousands. The number of Cameroonians applying for asylum in the US more than doubled���from 821 to 1,840���between 2015 and 2017. Cameroonians are now among the top 10 nationalities arriving at the southern border to seek asylum in the US���at least 10,000 Cameroonians have attempted to obtain asylum in the US since 2016.

And finally, there is the matter of American law enforcement, which���as a matter of principle, perhaps���seems incapable of dislodging anti-Blackness from its daily operation. Lum and others were ignored by medical staff, retaliated against for protesting their conditions, and met with a callous judiciary that lacks a full understanding of Cameroon���s fraught, complex political terrain.

Lum and others recount the ways in which Black immigrants were treated in Mexico, many lacking the basic necessities to maintain a life of normalcy and dignity. Matters on American soil are no better. Pauline Binam, a Cameroonian immigrant, was part of a wave of sterilizations that occurred in ICE detention. Forced sterilization, long been considered a form of torture by the United Nations, has been performed at alarmingly high rates on detained women at a Georgia ICE detention center. This, sadly, is not an anomaly. Cameroonian women have long been protesting the medical conditions in ICE detention. More than two Cameroonian women today, Neola and Josephine, are held in detention now, and have a history of treatment from medical professionals who have disregarded their autonomy.

The migration of Black women across land, boundary, and emotional terrain maps and deepens the understanding of home and personhood, of nation-building on the back of suffering, and of commitment to survival that is nothing less than a testament of miracles. Forced into slavery through the Americas, contemporary slavery through Libya, demeaned, and dislodged. Yet, the need for freedom, too, has its own momentum. Here are our women���vocal, fierce and imaginative���that continue to resist through movement and refuse infinite warfare through occupation. Lum, me, and others, are not going anywhere. There is a place in this world for the many of us for whom this world is unimaginably cruel. It is a world that demands the forging of new boundaries.

Lessons from Africa���s past to cope with COVID-19

Photo by Thomas de LUZE on Unsplash

This roundtable is part of the “Reclaiming Africa���s Early Post-Independence History” series, edited by Aishu Balaji, from Post-Colonialisms Today (PCT), a research and advocacy project of activist-intellectuals on the continent recapturing progressive thought and policies from early post-independence Africa to address contemporary development challenges. Sign up for updates here. It is adapted from a webinar of the same name, which you can watch here.

On the value of looking back to the early post-independence period as Africa grapples with the COVID-19 crisis

Omar Ghannam

Patrick Wayman is one of my favorite medievalists, he worked quite extensively on the Middle Ages and on pandemics and major crises, and he quite often says that major crises like pandemics and natural disasters don’t collapse systems or destroy them, they just expose the cracks that are inherent in the system. I think that’s exactly what COVID-19 has done, it has exposed the cracks of the neoliberal system. And so grappling with this crisis necessarily means grappling with the neoliberal and neo-colonial structures that have undermined an effective response, at which point it becomes useful to revisit the early post-independence period as a moment when governments, like that of Gamal Abdel Nasser, attempted to transform their countries relationship with the global economic system. In Egypt, there were a lot of internal limitations that ultimately proved fatal to Nasser���s project, leading to Anwar Sadat’s economic opening and the eventual triumph of neoliberalism with Hosni Mubarak���s facilitations. But it is of value to revisit the policies and thinking of that period in our present-day quest for alternatives.

There is a wealth of lessons to be learnt from the policies and thinking of the post-independence period, when governments pursued policies that were more faithful to the structural realities of African economies and driven by the desire to assert their economic and political sovereignty as a fundamental starting point for development. They attempted to address dependence on primary commodity export, foreign capital, and colonial currency, for example. They certainly made mistakes, many of which ultimately undermined the sustainability of their policies. But the clarity of thought and action in that period around Africa���s challenges in relation to their subordinate place in the unequal global economic order has been lost with the onset of neoliberalism in the 1980s and much of the progress undermined. Today, policymaking on the continent is again externalized to institutions like the IMF or designed according to a market logic that obscures Africa���s structural realities. But luckily, if we are going to effectively address COVID-19 and build societies that are resilient, equitable, and that can command the loyalty of its citizens, we don’t have to borrow ideas from outside the continent. Because the very fractures and deficiencies that have been highlighted by COVID-19 were things Africans themselves were contending with not too long ago.

On the immediate challenges African countries are facing in managing the COVID-19 crisis

Tetteh Hormeku-Ajei

Weak social infrastructure is one, medical facilities are severely lacking in Ghana due to decades of privatization and lack of investment. There were only a couple of places where emergency care units were available so the state was scrambling to create makeshift ICUs.

And similarly, the lack of domestic capacity to produce emergency equipment. Having previously relied on importing PPE, with Donald Trump seizing ships on the high seas, it became clear to African governments if they’re going to supply PPEs to their frontline staff, they have to make them themselves. In Ghana, having not invested in domestic production capacity over the years, we had to mobilize the private sector to sew masks and things like that, but this has not been adequate. And frontline health workers still lack adequate PPE.

Omar Ghannam

Healthcare became more and more dominated by the private sector in Egypt in the 1990s and the early 2000s, and it���s now estimated that over 50% of hospital beds are owned by the private sector. During the pandemic, we have seen an almost complete collapse of the Egyptian healthcare system. Hospital beds are either unavailable or incredibly expensive: we’ve seen prices go up to USD3,000 per day for admission, which in a country where one third of the population makes less than USD300 per month, is roughly the average GDP per capita. So, during a pandemic, people are being asked to pay effectively their yearly earnings for one day in hospital, which is not only morally reprehensible, it also means most people can’t access the care they need, exacerbating the crisis. Another challenge is Egypt’s problems with hard currency, which means whenever there is a devaluation of the pound, the medical supplies we import become scarce.

This is in stark contrast to the centralized planning during Nasser���s regime. This includes the planning of production, which would have ensured that Egypt, in a situation like ours, would have had the medication and the personal protection equipment we desperately need, but also centralized planning of provision in the form of government run hospitals, which used to be the primary form of healthcare for most Egyptians.

Tetteh Hormeku-Ajei

It���s interesting that in Ghana, and I’m sure in many African countries, the hospitals that were built in the immediate post-independence times are the same hospitals we are now relying on; after decades of disinvestment, it is all we have left to use during the COVID crisis. Governments in that period were committed to providing free healthcare for their people so they built modern health infrastructure that has stood the test of time, and the same goes for water, education etc. Having just emerged from decades of colonial rule and the colonial destruction of their autonomy, the state had to play a central role in reorganizing society. But there was also a social contract between the state and its people, in which the state had to meet certain needs while people participated in the post-independence project, and this social contract was translated in terms of intervention in a range of areas that are relevant today.

On the relationship between immediate concerns like healthcare infrastructure and capacity, and the structure of African economies

Tetteh Hormeku-Ajei

Ultimately, the limitations in state capacity and institutions, and the lack of policy or fiscal space to transform this, are all rooted in the structure of our society and our economy. Economies that are structured to be dependent on the international order���that simply produce and export raw materials for the purpose of importing all the manufactured goods needed���are also inevitably politically dependent on regimes that have an interest in diminishing state capacity and weakening public infrastructure through liberalization, marketization, and privatization. For example, structural adjustment programs undermined capital controls in Ghana, allowing people to take money in and out of the country with minimal regulation. COVID-19 caused capital flight, and without necessary resources at their disposal, the government was forced to turn to the international community for more conditional emergency support, something that may not have been necessary were the appropriate mechanisms in place. This translated to a lack of fiscal and policy space for the state to commandeer resources and respond to the crisis.

It is this economic dependence on the global North that has been leveraged to so effectively demonize and weaken the state in Africa over the past four decades of neoliberalism. To dismantle the registrar capacity of the state, its social infrastructure, its cadre capacity, so that finally the state is not in a position to do the things they were called upon to do. And as a result we are facing a crisis of state legitimacy. If the state is unable to provide protective equipment to frontline workers and it can���t command the confidence of ordinary people, very soon, when they are asked to stay home, people will come and say ���I have to go out and work,��� and will defy the order.

Kareem Megahed

In Egypt, rather than being dependent on the export of primary commodities, we are dependent on tourism for generating about 20% of our GDP. In the context of the country needing to import vital medical supplies, 60-70% of our foodstuff, and a lot of intermediate products necessary for factories to run, when a crisis of the scale of COVID-19 strikes and tourism is effectively halted, this creates profound problems for the Egyptian economy on a macroeconomic scale. The government recently released projections for the next year, and in the best-case scenario, we will see an extra 4% of Egyptians fall under the poverty line, and in the worst case scenario, we’ll see 10%, putting the final poverty rates at around 44%. That is a massive devaluation in the ability of millions of people to secure their basic needs. Egypt has become integrated into the global value chains that are the hallmark of neoliberalism, where each part of the product is manufactured somewhere else. Now with COVID-19 and the limitations it has put on production, access to production facilities, and the movement of goods and services across countries, the fragility of these global value chains have been exposed. And so many countries are suffering from their lack of control over the production of their most basic necessities.

One positive is that the inflation rate, which has been at historic highs since 2016, crossing the 30% threshold multiple times, has been at around 5%, due to the constriction in hard currency inflows with the stark decline in tourism. This means that for now, worsening poverty will not be exacerbated by rising inflation. But Egypt is now seeking a new international loan from the World Bank-IMF and other international lenders, which will undoubtedly trigger another round of austerity, spiking inflation and exacerbating the problem. And the country will continue to be trapped in the cycle of increased poverty, lower revenues for the state, international loans, and then austerity measures that in turn increase poverty.

What we’re seeing is that after decades of the neoliberal approach of leaving everything to markets and minimizing state intervention, in a crisis situation when the state is the only actor that is capable of intervening in a meaningful way, it cannot do so because it has been hampered by years of effectively being starved.

Omar Ghannam

Another aspect, one we haven���t been able to quantify in Egypt, is the relationship between COVID-19, economic structures, and gender-based violence. We’ve been seeing reports from around the world that incidences of domestic violence have been increasing during the lockdown and curfews, which has also been exacerbated by rising unemployment. In Egypt, about one third of households rely on income generated by women, and in a lot of these households they are the primary breadwinners. However, most women in Egypt work in the informal sector where they have no formal protections, no unemployment benefits, no pensions or severance packages. This exacerbates gender-based violence as women are less likely to have the financial means to escape abusive relationships, to be able to provide for themselves and their children away from their abusers, and during COVID-19 they are effectively locked in with their abusers with no viable way of escape. So this is another area where we see that although Nasser’s regime was by no means a revolutionary feminist project���it presided over what we���re resigned to call a public patriarchy���it still guaranteed significant rights for women that have since been rolled back. And as a result we���ve seen significant changes in the attitude of society towards working women and their presence in the workplace and the kinds of rights they should be granted, which are brought into stark relief in moments like this.

On the post-independence approach to managing crises like COVID-19

Kareem Megahed

Self-sufficiency was a core tenant of the post-independence projects, they focused on the internal orientation of the economy and believed the economy should be structured to fulfill the people’s needs first and foremost. So the provision of healthcare and other basic needs such as education and housing was a very important part of the social contract. Universal healthcare in particular played an important role in raising the average life expectancy of Egyptians. The Nasser government saw the last epidemic outbreak of cholera and worked significantly on reducing the incidence of other endemic issues such as bilharzia.

The regime also gave special attention to pharmaceutical industries���between 1952 and 1967, workers in chemical production (under which pharmaceuticals were grouped) increased fourfold within the span of 15 years with the gross value added increasing by 700%. They also saw a significant reduction in the reliance on imports, as the domestic production ratio of total supply increased from roughly 50% in 1947 to over 60% by 1967. The regime wasn’t successful in establishing a completely indigenous industry due in part to the serious internal limitations of their incrementalist approach, but there was significantly greater self-sufficiency when it came to medical needs.

On the connections post-independence governments saw between economic transformation and liberation

Tetteh Hormeku-Ajei

Speaking to my example earlier of capital flight, Ghana and other African countries created fiscal space through financial institutions and measures that ensured the wealth being generated in their economies were being used and reinvested for economic expansion. This includes instruments we���re familiar with, like development banks, and also central bank policies that made credit available to the most vulnerable sectors, such as the rural economy.

Above all, post-independence governments intervened to protect their economies within the international economic order. It was not simply a question of building a modern economy, but recognizing what structures they inherited from colonialism and reorganizing their place in the international economic order. Because they recognized that political independence has to be complemented and rooted in economic sovereignty���over their resources, over their people, over their knowledge. In important sectors like minerals, natural resources, and agriculture, they ensured those things were available for and oriented towards their people’s development. Across Africa, whatever their ideology, all post-independence governments nationalized the mineral resources in their countries and took the appropriate steps to negotiate the terms within which foreign investors could participate in extracting these resources, ensuring it was compatible with the development of their people. It was an assertion of sovereignty, to critically reorganize their economies in their continued fight against the legacy of colonialism.

October 18, 2020

On AIAC Talk: The emptiness of anti-corruption politics

African Union Summit in Malabo, Equitorial Guinea. Image via the Embassy of Equitorial Guinea on Flickr CC.

Corruption is always in the global spotlight. Just last week, Sierra Leone���s Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) postponed a hearing by former president Ernest Koroma over findings into alleged corruption during his tenure after Koroma���s supporters gathered outside his residence to stop officials from questioning him. In South Africa, anti-corruption protests led by the labor movement have happened in recent weeks. To be sure, corruption is a serious problem��� but is anti-corruption a serious politics?

This week on AIAC Talk we have contributing editors Benjamin Fogel and Wangui Kimari. Ben, who is also a contributing editor at Jacobin, once argued over there that ���If the Left is serious about wielding and transforming state power, it needs to go beyond a moralistic understanding of state power.��� In our correspondence to bring her onto the show, Wangui summarized anti-corruption politics as ���a kind of vacuous politics taken up by so-called leaders at the cost of a substantive people-centered politics/issues.��� Ben is also a historian of Brazil and South Africa, finishing off a PhD at NYU, and Wangui is a participatory action research coordinator for the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, Kenya, using that experience to help put together our series on life in Nairobi, ���Capitalism in My City.��� As scholars of social movements in South Africa, Brazil and Kenya, we hope that Ben and Wangui can help us make sense of anti-corruption, and if it isn���t the answer��� then what is to be done?

But, one leader whose anti-corruption policies were once lauded is that of Tanzania���s president John Magufuli. Nicknamed ���the Bulldozer��� after coming to power in 2015, Magufuli���s support will be tested on the 28th of October when Tanzanians vote in a general election. Despite their initial popularity, Magufuli���s anti-corruption efforts are now also seen as providing cover for a sharp authoritarian turn involving a crackdown on dissenting journalists and opposition parties. Many are questioning the freedom and fairness of the upcoming elections, but are these fears warranted or overblown?

Joining us then in the second half of the show to discuss Tanzania���s electoral politics are Sabatho Nyamsenda and Elisa Greco. Sabatho is an assistant lecturer at the University of Dar es Salaam and a founding member of Jukwaa la Wajamaa Tanzania (Tanzania Socialist Forum). Elisa is an Associate Professor in International Political Economy and Development at the European School of Political and Social Sciences conducting ethnographic research in Tanzania and Uganda.

Stream the show Tuesday at 18:00 SAST, 16:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��Youtube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

If you missed our program last week, we had on literary scholars Bhakti Shringarpure, Lily Saint and Mukoma wa Ngugi to discuss African books��� reading them, teaching them, and what would constitute the decolonizing of particularly literatures in English. You can watch clips from that show on our YouTube channel, and the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

The emptiness of anti-corruption, on AIAC Talk

African Union Summit in Malabo, Equitorial Guinea. Image via the Embassy of Equitorial Guinea on Flickr CC.

Corruption is always in the global spotlight. Just last week, Sierra Leone���s Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) postponed a hearing by former president Ernest Koroma over findings into alleged corruption during his tenure after Koroma���s supporters gathered outside his residence to stop officials from questioning him. In South Africa, anti-corruption protests led by the labor movement have happened in recent weeks. To be sure, corruption is a serious problem��� but is anti-corruption a serious politics?

This week on AIAC Talk we have contributing editors Benjamin Fogel and Wangui Kimari. Ben, who is also a contributing editor at Jacobin, once argued over there that ���If the Left is serious about wielding and transforming state power, it needs to go beyond a moralistic understanding of state power.��� In our correspondence to bring her onto the show, Wangui summarized anti-corruption politics as ���a kind of vacuous politics taken up by so-called leaders at the cost of a substantive people-centered politics/issues.��� Ben is also a historian of Brazil and South Africa, finishing off a PhD at NYU, and Wangui is a participatory action research coordinator for the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, Kenya, using that experience to help put together our series on life in Nairobi, ���Capitalism in My City.��� As scholars of social movements in South Africa, Brazil and Kenya, we hope that Ben and Wangui can help us make sense of anti-corruption, and if it isn���t the answer��� then what is to be done?

But, one leader whose anti-corruption policies were once lauded is that of Tanzania���s president John Magufuli. Nicknamed ���the Bulldozer��� after coming to power in 2015, Magufuli���s support will be tested on the 28th of October when Tanzanians vote in a general election. Despite their initial popularity, Magufuli���s anti-corruption efforts are now also seen as providing cover for a sharp authoritarian turn involving a crackdown on dissenting journalists and opposition parties. Many are questioning the freedom and fairness of the upcoming elections, but are these fears warranted or overblown?

Joining us then in the second half of the show to discuss Tanzania���s electoral politics are Sabatho Nyamsenda and Elisa Greco. Sabatho is an assistant lecturer at the University of Dar es Salaam and a founding member of Jukwaa la Wajamaa Tanzania (Tanzania Socialist Forum). Elisa is an Associate Professor in International Political Economy and Development at the European School of Political and Social Sciences conducting ethnographic research in Tanzania and Uganda.

Stream the show Tuesday at 18:00 SAST, 16:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��Youtube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

If you missed our program last week, we had on literary scholars Bhakti Shringarpure, Lily Saint and Mukoma wa Ngugi to discuss African books��� reading them, teaching them, and what would constitute the decolonizing of particularly literatures in English. You can watch clips from that show on our YouTube channel, and the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

The grand plan to save forests has failed

Photo by Crystal Mah on Unsplash

This post is part of our series “Climate Politics.”

At the 13th Conference of the Parties (COP 13) in 2007, parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) agreed to a grand plan to use forests to ���save the world��� from the climate change crisis. Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries (named REDD+) was born out of the recognition that forest conservation can significantly reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs). The premise for REDD+ is straightforward: tropical forests are the world���s lungs, storing roughly 25 percent (300 billion tons) of the planet���s terrestrial carbon dioxide���a greenhouse gas. However, since 1990, more than 420 million hectares of forests have been chopped down to make way for farms, housing and shopping malls, releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and reducing the storage capacity of the forests.

REDD+ proposes a simple solution. Developed countries do not want developing countries to of forest-dependent economic development and so are willing to compensate developing countries for this ���lost opportunity.��� For example, the US cleared up 90% of its virgin forests between 1600 and 1900 on its way to industrialization. As part of reducing their emissions, rich countries and their corporations can help ���save��� a tropical forest and claim the resulting carbon credits. Practically saving or conserving a forest could mean funding for the conversion of forests into protected areas, paying local communities to move from forest-dependent livelihoods to alternative livelihoods, or a focus on conserving forests and tree species���like Grevillea robusta, Pinus radiata, Spekboom or Eucalyptus���that are good for the capture of carbon but of little tangible value to local communities.

While the rationale and mechanism of REDD+ seem straightforward, the implementation and the results have been unsatisfactory and mired in controversy. Twelve years of REDD+ have been unable to significantly reduce deforestation. In places like Mai-Ndombe in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), REDD+ has failed to both halt deforestation and benefit local communities. While architects of the program, who mostly reside in the West, are concerned with clean air and greenhouse gasses, custodians of the majority of the forests in developing countries, including indigenous people and forest-dependent communities, are thinking about where the next meal will come from.

As part of my research on Malawi, for example, I have shown that forests are important for the nutrition of forest-dependent communities. Such custodians of the forests, however, were not fully involved in the design of REDD+, nor its implementation on the ground. As Abdul-Razak Saeed and others pointed out, ���while communities were engaged in the REDD+ projects, their engagement was often in an ad-hoc fashion. Decisions were taken before communities were consulted to gauge their reaction.��� In Peru, local communities were only consulted after the project was approved, while in Kinshasa, projects were developed before being shared with communities.

At the core of the REDD+ are neoliberal and corporate-friendly ideas. These ideas are aimed at evading the problem caused by the real polluters by creating a market for carbon to continue to extract profits unabated. Africa as a whole only contributes 3% to GHGs. REDD+ is functioning as a form of governance���a particular framing of the problem of climate change and its solutions that validates and protects the ways of life of capitalism while marginalizing the lives of forest dependent communities and shifting the development trajectory of the developing countries away from what most developed nations did. It is, as others have labeled it, ���CO2loniasm.���

As many critics have argued, REDD+ secures the property rights of global North fossil fuel users while maintaining the opportunities for corporate profit over forest-dependent communities. REDD+ in this context is part of a longer history of neoliberalism, which represents the marginalization of vulnerable groups of people similar to conservation projects, and where success is measured by the number of locals who can be persuaded with money to give up their livelihoods, birthrights, and other forms of identity that are heavily interwoven with forests. These communities have other ways of life that can save the forest beyond what would be required to make the community carbon neutral for the benefit of Western elites.

As some projects that have been implemented under REDD+ have shown, the negative impacts on indigenous and forest-dependent people are rampant. For example, in the DRC, which is one of the early experimental sites with several projects, researchers found that the projects were leading to land grabs. Another example is in Uganda where a Norwegian company bought huge tracts of land to plant fast-growing plants. However, the commercial plantations in this project barred local households from harvesting any timber or other NTFPs, resulting in loss of income for the entire community. REDD+ links forest conservation and more than one billion people who depend directly on forests to global carbon markets���exposing them to volatile commercial power structures. The communities would be at ransom to the price of carbon and the vicissitudes of the financial sector. Whenever the price of carbon increases, the demand for carbon credits rises in tandem pushing more people out of their traditional lands and ways of life.

Solutions arrived at in the big conference halls of the West, implemented in developing countries without the full participation of the people, are bound to fail. New ideas that explicitly involve the forest-dependent communities are imperative. Ongoing research��by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) on the impact of REDD+ initiatives on community livelihoods highlights the need for policies that respond to the unique ways that local communities use their forests. As Alain Fr��chette of the Rights and Resources Institute notes, ���strong indigenous and community land rights and a clear understanding of who owns forest carbon are vital prerequisites for climate finance to succeed in its goals of reducing poverty and protecting forests.���

���To succeed, these projects must include the communities that have managed these forests for generations,��� says Chouchouna Losale of the DRC���s Coalition of Women Leaders for the Environment and Sustainable Development. Western countries will have to face the grim reality that saving the world from the climate catastrophe will not come from African countries, but by addressing the source of the greenhouse gases within their boundaries. African governments need to protect the marginalized and have the right to determine their own path to sustainable development. This will happen when negotiations are balanced and inclusive. For example, a pilot REDD+ project in Nepal was billed as successful because it fully involved the national and community level institutions in decision making and forest conservation. As the authors of the study reported, ���participating communities were enthused���and met more frequently to make community decisions related to forests.���

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers