Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 157

September 28, 2020

O desafio da governa����o aut��rquica em Angola

Photo by Jorge S�� Pinheiro on Unsplash

For English click here.

No final de mar��o 2020, ap��s aprova����o parlamentar, o Conselho da Rep��blica de Angola recomendou que as primeiras elei����es aut��rquicas na hist��ria do pa��s se realizassem no pa��s antes do fim de 2020. Para al��m da posterior incerteza causada pela pandemia global COVID-19, este parecia ser um desenvolvimento positivo na complexa e tortuosa caminhada de Angola para a democracia nos seus mais de quarenta anos de independ��ncia. Ap��s a independ��ncia em 1975, Angola entrou imediatamente numa guerra civil que durou quase consecutivamente at�� 2002. Nesse per��odo, o regime angolano passou de um sistema de partido ��nico de corte socialista para uma ���social-democracia��� multupartid��ria que, em qualquer caso, apenas conheceu um partido no poder: o MPLA. Concomitantemente, a hist��ria legislativa do pa��s tamb��m tem sido complexa, com a acumula����o de textos constitucionais provis��rios at�� a aprova����o final da atual Constitui����o da Rep��blica de Angola em 2010.

A reforma constitucional de 2010 incluiu a Se����o VI que colocou em pr��tica um processo de descentraliza����o do ���Poder Local���, mas ap��s dez anos do novo quadro jur��dico o processo nunca passou ���do papel para a pr��tica���, com constantes atrasos e adiamentos.

No entanto , ap��s as elei����es de 2017, o novo presidente Jo��o Louren��o anunciou o compromisso p��blico de abordar a quest��o das elei����es aut��rquicas atrav��s da promo����o de um ���debate p��blico global���. Posteriormente, um memorando do Minist��rio da Administra����o do Territ��rio e Reforma do Estado de 2018 revelou um plano espec��fico com fases para a implementa����o efectiva das autoridades locais atrav��s de um processo gradual. Neste contexto, a decis��o de Mar��o de 2020, emergindo na v��spera da pandemia COVID-19, foi outro importante e necess��rio passo para a t��o esperada realiza����o de elei����es. No entanto, apesar da implementa����o de elei����es municipais ser uma das poucas propostas pol��ticas que re��ne consenso geral no espectro pol��tico angolano, a mesma tornou-se, no momento pr��-COVID -19, ba principal batalha pol��tica no pa��s. Por exemplo, no passado m��s de agosto de 2019, enquanto o parlamento angolano aprovava por unanimidade o pacote legislativo municipal, realizou-se uma manifesta����o �� porta da Assembleia Nacional, com dezenas de jovens activistas a protestar contra a mesma.

Quais s��o, ent��o, as raz��es para este protesto?

Os participantes na manifesta����o eram na sua maioria membros de v��rias plataformas c��vicas locais que surgiram ap��s 2016, no rescaldo do not��rio processo ���15 + 2��� – a deten����o e julgamento de 17 ativistas em 2015, acusados de tentativa de golpe de estado . Muitos dos detidos eram activistas do chamado Movimento Revolucion��rio ou ��� Rev�� ���, que surgiu em Angola em 2011, na sequ��ncia da Primavera ��rabe e liderou v��rias manifesta����es contra o ent��o presidente Jos�� Eduardo dos Santos e o seu gabinete. Ap��s o julgamento, v��rios ativistas se reagruparam em plataformas focalizadas em abordar problemas locais e regionais, ao mesmo tempo que trabalhavam em rede uns com os outros. �� o caso, por exemplo, do Projeto Agir, uma plataforma, que surgiu da mobiliza����o de activistas no distrito de Cacuaco, a norte de Luanda. Da mesma forma, outras plataformas surgiram em Luanda : PLACA (Plataforma Cazenga em A����o) e LDM (Liberttadores de Mentes) no distrito de Cazenga , Mudar em Viana, PIKK (Plataforma de Interven����o do Kilamba Kiaxi) no Kilamba Kiaxi e NBA (N��cleo de Boas Ac����es) em Benfica. E fora de Luanda, tamb��m surgiram outros movimentos de cidad��os: Okulinga (Matala), Kintwadi (Uige), Laulenu (Moxico), MRB (Movimento Revolucion��rio de Benguela, no Lobito), Balumukeno (Malanje).

Estas plataformas, como referimos, est��o organizadas em torno de problemas e lutas locais. Por exemplo, ao longo de 2018 a PLACA, Agir e outras plataformas promoveram diversos protestos contra o administrador do distrito do Cazenga, Tany Narciso, devido �� crescente inseguran��a, falta de acesso �� ��gua e desvio de fundos. Da mesma forma, em Setembro de 2019, a plataforma Laulenu aproveitou a visita presidencial de Jo��o Louren��o �� regi��o do Moxico para organizar um protesto contra o governador local Gon��alves Muandumba devido �� sua governa����o corrupta e falta de resposta na solu����o dos problemas dos seus constituintes. Ao mesmo tempo, no entanto, as mesmas plataformas abra��aram a quest��o das autarquias como um dos seus principais focos , atrav��s da converg��ncia numa rede nacional chamada ���Movimento Jovens Pelas Autarquias���. Aqui, ao mesmo tempo que necessariamente convergem com o projecto do governo de Louren��o de implementa����o de elei����es municipais, o movimento contesta vigorosamente o mecanismo de implementa����o, que de acordo com o artigo 242 da Constitui����o de 2010 �� estabelecido atrav��s de uma l��gica gradualista, determinada pelo pr��prio governo, sem consulta p��blica ou presta����o de contas. Subsequentemente, em 2018 o MPLA adoptou uma abordagem geograficamente gradual, segundo a qual, seguindo um crit��rio de ���m��rito���, apenas 55 dos 164 c��rculos eleitorais poderiam votar numa primeira fase, enquanto outros o fariam apenas numa fase posterior. Coincidentemente ou talvez n��o, circunscri����es como o Cacuaco e outros distritos ou munic��pios tradicionalmente n��o alinhados com o MPLA foram deixados de fora da lista inicial. Portanto, do ponto de vista do Agir e das outras plataformas , este foi um movimento enganoso: embora o governo estivesse ciente da ambi����o de seu eleitorado de uma representa����o mais direta, tamb��m estava ciente da possibilidade de perder inst��ncias de governan��a para partidos de oposi����o (nomeadamente a UNITA). Ao mesmo tempo, o MPLA simulava publicamente um movimento de abertura de governan��a para a cidadania, mas f��-lo apenas em termos que permitiam a sua auto-perpetua����o no governo.

Em resposta, estas plataformas n��o s�� promoveram uma den��ncia cr��tica do Pacote Legislativo Aut��rquico do governo em manifesta����es recorrentes em frente �� Assembleia Nacional, como tamb��m promoveram v��rios debates, mesas redondas e onjangos (reuni��es comunais coletivas) para discutir o processo e conscientizar os cidad��os. A PLACA e o Agir tamb��m co-autoraram a sua pr��pria revis��o do pacote legislativo, onde oferecem argumentos para a implementa����o de um sistema aut��rquico n��o gradual, horizontal e universal, baseado na l��gica de ���devolu����o do poder �� cidadania���. O ponto de partida para tal �� a ideia de que a autonomia municipal, n��o sendo a solu����o para todos os problemas de Angola, �� certamente um instrumento de governa����o mais eficaz e leg��timo do que o ctual centralismo da administra����o do Estado, por si s�� um obst��culo ao desenvolvimento sustentado para uma democracia transparente e justa: a falta de responsabiliza����o, a concentra����o de recursos, a falta de representa����o popular, a fraca participa����o c��vica e o controlo monopartid��rio das comunidades locais.

Em Julho de 2020, em plena crise do COVID-19, o parlamento angolano aprovou mais um pacote legislativo para a implementa����o do sistema eleitoral municipal. No entanto, apesar do avan��o na agenda em tempos t��o cr��ticos, o ambiente em Luanda �� de incerteza quanto ��s pr��ximas elei����es aut��rquicas . J�� em Setembro, a suspeita foi finalmente confirmada, ap��s o Conselho da R��p��blica anunciar oficialmente um novo adiamento sine die, “at�� que as condi����es certas estejam estabelecidas”.

Assim, para muitos cidad��os angolanos, entre as quais plataformas activistas como o Agir, PLACA, PIKK e outras, a incerteza decorre menos da poss��vel data de celebra����o de elei����es e mais do consenso fict��cio constru��do em torno do processo, que continua como sempre a ignorar as opini��es e expectativas da cidadania angolana. Neste sentido, para os activistas angolanos, a luta continua.

Ruy Llera Blanes, antrop��logo, professor associado da Escola de Estudos Globais da Universidade de Gotemburgo.

Hitler Samussuku, licenciado em Ci��ncia Pol��tica pela Universidade Agostinho Neto e ativista dos direitos humanos.

The Cold War’s unfinished legacy

Photo by Simon Infanger on Unsplash

Historians of the Cold War have only recently begun to highlight the role of the third world in what has long been understood (at least in certain circles) as a distinctly bipolar conflict, one pitting American capitalism against Soviet communism. Of course, both political-economic systems claimed spheres of influence that included large swaths of the global South, which quickly became a proving ground for competing ideologies���its inhabitants often unwilling pawns in complex geostrategic games. Consult some of the best revisionist and ���post-revisionist��� histories of the Cold War, and you will not find mention of Indonesia���or, for that matter, of Nigeria or Mozambique. So consistent has been this tendency to overlook the third world that many of those currently writing about the Cold War are still obliged to identify continental lacunae���to assure their readers that the cast of national characters in fact encompassed more than Castro���s Cuba and the Eastern bloc countries in addition to the two superpowers.

As journalist Vincent Bevins suggests in The Jakarta Method: Washington���s Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World, centralizing the Third World in the historiography of the Cold War is not an eccentric or ���politically correct��� gesture but a necessary, even logical, step toward a basic understanding of the decades-long conflict. The term itself was a Cold War coinage, the conceptual product of anticolonial nationalisms���the pivot of independence movements from Ghana to Vietnam. ���When the leaders of [newly independent] nation-states took up the term,��� Bevins writes, ���they spoke it with pride; it contained a dream of a better future in which the world���s downtrodden and enslaved masses would take control of their own destiny��� For much of the planet, the Third World was not just a category; it was a movement.���

More than mere historical accuracy is at stake here. Bevins��� argument, distilled in the book���s subtitle, is that a global history of the Cold War is required for a clearer comprehension of today���s world. The Jakarta Method is a sweeping account of some of ���the most important events in a process that has fundamentally shaped life for almost everyone���whether you are sitting in Rio de Janeiro, Bali, New York, or Lagos.��� The US has long sought to refashion the world in its own image, or, at the very least, in ways conducive to its economic interests. Its methods have included the kind of hysterical anticommunism that is making a comeback in the country���s political affairs (if it ever really went away). Homegrown fascisms, fueled by anti-immigrant sentiment and committed to the preservation and expansion of the underclass, have all too obvious overseas counterparts, from Poland to Brazil. Completed around the time that Jair Bolsonaro ascended to the Brazilian presidency, The Jakarta Method couldn���t be timelier. It is a triumph of reporting that powerfully demonstrates that some of the 20th century���s ugliest episodes are still unfolding.

That the US ���suffered��� the ���loss��� of China in 1949, and that of North Korea around the same time, is well understood. Less clear, perhaps, is that such ���losses��� precipitated frenzied attempts both to secure perceived territorial and geopolitical gains and to ensure the defeat of left-leaning administrations in other parts of the world, from Brazil to Indonesia���two countries at the center of Bevins��� analysis. ���It���s very often forgotten,��� the author points out, ���that violent anticommunism was a global force, and that its protagonists worked across borders, learning from successes and failures elsewhere as their movement picked up steam and racked up victories.���

One of the challenges of writing a global history of the Cold War is to shed light on little-known participants (often, if somewhat misleadingly, referred to as ���proxies���) without ignoring or underplaying the conflict���s true scope���to attend to national and regional realities while keeping the bigger geographic picture very much in mind. Another challenge is to acknowledge the Cold War���s continuities with earlier antagonisms���its roots in tensions that preceded even World War II. The Jakarta Method succeeds in meeting the first challenge, offering as it does a welcome comparative study of Southeast Asia and Latin America, one that also, for good measure, mentions Africa���s role in this saga. The second challenge demands an even longer view than the author���s methodology, with its reliance on the accounts of living survivors of historical atrocities, allows���or than, admittedly, the book, at a mere 300 pages, is designed to provide.

Bevins is a journalist, not an historian, and if The Jakarta Method privileges reportage, it is often for the better. The book is full of the voices of the victims of anticommunist violence, some of whom escaped Suharto���s Indonesia only to be terrorized in Brazil or Chile. This is a unique strength: such biographical mini-narratives illustrate not simply the human stakes of imperialist aggressions and US-backed autocracies, but also the impossibly wide net cast by anticommunist fervor. Try though they invariably did, Bevins��� peripatetic contacts simply could not escape it. ���My choice of focus, and the connections that I saw, were probably dictated to some extent by the people I was lucky enough to meet,��� writes Bevins, who was the Brazil correspondent for the Los Angeles Times before covering Southeast Asia for the Washington Post, ���but���their story is just as much the story of the Cold War as any other is, certainly more so than any story of the Cold War that is focused primarily on white people in the United States and Europe.���

Bevins is correct, of course, but such a disclaimer downplays his mastery of secondary sources. The author has read widely and well. The Jakarta Method synthesizes some of the best scholarship on the Cold War, decolonization, and the Non-Aligned Movement, offering an indispensable introduction to a dizzying array of sociopolitical contexts. The book is a monumental achievement, written, at times, with the grace of a gifted novelist. The concluding passages, which take elegant inventory of the past���s saturation of the present, are simply breathtaking.

Calling for ���a full view of the Cold War and US goals worldwide,��� Bevins draws attention to ���a traumatic rupture in the middle of the 1960s������to the titular formula for eliminating all opposition to crony capitalism: mass murder. The systematic annihilation of some of the world���s largest communist parties, appalling in itself, caused considerable collateral damage and, in many cases, the entrenchment of ruthless military dictatorships that, operating as pro-US puppet regimes, recalled and even exceeded the depredations of colonial rule.

Bevins��� chronicle of Indonesia takes stock of those late-colonial efforts that anticipated the more successful methods of US imperialism. Much as the French were intent on returning to ���their��� Indochina after World War II, the Dutch had designs on the Java that had been wrested from them by Imperial Japan. Never mind that indigenous populations had set up their own governments in 1945: the Dutch, like Europe���s other colonial powers, desired a revivification of pre-war imperial conditions. What makes Indonesia such a crucial, magnetizing case study, Bevins argues, is the Bandung Conference, set up just a few years after the Dutch were finally expelled from the country. Bevins offers a fine, nuanced sketch of Sukarno, the independence leader who became the first president of Indonesia, only to be removed from power amid a coup whose strategic mystifications preceded the anticommunist mass killings of 1965-1966.

Sukarno was no radical, but he remained outspoken on the subject of imperialism. At the Bandung Conference of 1955, which helped inaugurate a third world project rooted in shared Asian and African concerns regarding the scope and persistence of imperialist ambition, Sukarno delivered a speech in which he implored his listeners to resist ���think[ing] of colonialism only in the classic form��� familiar from decades of European rule. ���Colonialism,��� Sukarno continued, ���has also its modern dress, in the form of economic control, intellectual control, actual physical control by a small but alien community within a nation. It is a skillful and determined enemy, and it appears in many guises. It does not give up its loot easily.���

Like Kwame Nkrumah, Sukarno openly relied upon the term ���neocolonialism��� in order to succinctly describe the conditions of forced dependency in which so much of the Third World found itself, despite the ostensible achievement of national self-determination in the aftermath of formal colonial rule���and despite, as well, the rhetoric of sovereignty that the United States continued to peddle so hypocritically. While Sukarno endeavored to maintain Indonesia���s non-aligned status, powerful American leaders decided that ���[a]nyone who wasn���t actively against the Soviet Union must be against the United States.��� Thus, even Sukarno���s moderate policies placed him in a vulnerable position.

Within three years of the Bandung Conference, the CIA was executing a massive anticommunist operation in Indonesia, complete with aerial bombardments. That, of course, was hard power���a show of imperialist force. But soft power played a role, too, as Bevins points out. His explorations of the cultural dimensions of anticommunism are never less than stimulating; they provide useful evidence of the imprinting power of American-style capitalism, which had to be ���sold������and not simply imposed���abroad. Bevins��� descriptions of the growing demands of Western governments and international financial institutions (particularly the IMF) do even more than that. Together, they furnish additional support for Quinn Slobodian���s contention that neoliberalism, which conventional periodization dates to the 1980s���to the reigns of Reagan and Thatcher���in fact has older, deeper roots, located, particularly, in parts of the world that have too rarely received adequate scholarly attention.

The additive power of Bandung, which brought together populations from across Asia and Africa, had its horrific obverse in the Indonesian politicide that followed just ten years later. In addition to members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (the PKI) and suspected communist sympathizers, the purge targeted Gerwani women, Javanese Muslims, and Indonesians of Chinese descent. The political upheavals that convulsed Indonesia beginning in the fall of 1965 are notoriously complicated; some of them remain downright inscrutable. To his credit, Bevins does not attempt to downplay these obstacles to politico-historical comprehension. He admits that much is not known (and perhaps cannot be known) with any real certainty���not least because the CIA, the Indonesian military, and many other organizations have not released all of the documentary evidence that they surely possess. But there is also much that is now available to researchers, and Bevins avails himself of these sources, citing, for example, now-declassified US State Department cables that reveal that Washington, eager to prevent Southeast Asia���s most populous country from evading its grasp (and ejecting its oil companies), ���quickly and covertly supplied vital mobile communications equipment to the [Indonesian] military.��� America���s support for the purge was not simply rhetorical, a measure of the outspoken anticommunism of the country���s political establishment; it was also material. As Bevins points out, US Army installations���particularly Fort Leavenworth, in Kansas���provided extensive training to thousands of Brazilian and Indonesian military officers who would go on to commit various atrocities in their respective countries.

Bevins��� careful accounts of third worldist publications reveal that his transnational methodology, though it may be unfamiliar to some readers, is really nothing new. It has, in fact, had a long, noble, vibrant life in anti-imperialist reportage. Throughout the 1950s, The People���s Daily, the newspaper run by the PKI, routinely ���paid very close attention to���events���half a world away,��� Bevins writes as he details the activities���and political motivations���of journalists committed to uncovering American imperialism in Guatemala and other locations far from Jakarta (at least geographically). Such individuals, increasingly aware that even the mildest of social reforms were incurring the wrath of the US, ���reported [far-flung] events more accurately than the New York Times.��� Bevins��� honesty regarding the shortcomings of mainstream journalism is refreshing; this is one American reporter who clearly understands the limitations of the ���paper of record.��� Bevins also shows how the concentration of media ownership has material effects, including in Brazil, much of whose mainstream media is controlled by ���a few powerful landowning families.��� The ���mystifications of an anticommunist industry��� are, then, exactly that: the obfuscatory efforts of a privileged minority for which political understanding is dangerous���a threat from ���below.���

On the opportunistic tendency to depict as dangerously communist even minor or incremental reforms���like national literacy campaigns and the extension of voting rights���Bevin is particularly strong. But he is not a trained historian, and his account of the global contexts in which the eponymous strategy was forged is perhaps too speedy, too economical���an instance of ���reader-friendliness��� working against itself, raising more questions than it can possibly answer, even with endnotes. Sorely missing is an index���an indispensable navigational tool, one that would assist the reader in juggling so many names, so many places. (Detailed political maps would also help; the book���s sole map is included as an appendix, and it is neither sufficient nor particularly navigable.) Some key names���those both of historical figures and of the private actors who were the author���s interviewees���reappear after rather lengthy intervals; an index would have allowed the reader to efficiently refer back to their earlier appearances���to reestablish biographical contact with a truly international cast of characters.

Readers of Africa Is a Country will want to know how the campaigns that Bevins describes actually played out on the African continent���whether the so-called Jakarta Method was in fact applied there. As he must, ill-fated Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba looms relatively large here. While Bevins does not promise to offer a comprehensive account of the Cold War���s effects on Africa and Africans, he provides an accurate overview of some of the ultimate effects of Portuguese colonialism in Angola and Mozambique. His occasional references to Nigeria, however, beg certain questions about that country. Like Indonesia, Nigeria boasted a population size that rendered it impossible for the superpowers to overlook. A brief consideration of Nigeria���s Cold War experiences substantiates many of Bevins��� claims about the universal application of anticommunist pressures. Throughout the first half of the 1960s, American leaders repeatedly articulated their fear of ���losing��� Nigeria, if not to Communism, then to the sort of insufficiently ���cooperative��� capitalism that troubled them nearly as much. The riots in Nigeria that followed Lumumba���s assassination served to galvanize Washington���s anticommunist forces. Worrying over a so-called ���Soviet pattern��� in Nigeria, one influential American cited ���Communist and pro-Communist infiltration into youth groups,��� as well as ���anti-white and anti-American��� attitudes among the vast and growing population. Others insisted that ���many Nigerians seem pro-West and pro-American in their attitudes,��� and sought to reassure ���American businessmen��� who were already installed in and around Lagos. ���In foreign affairs generally,��� concluded one anticommunist, ���the Nigerian government has been leaning rather strongly toward the West. When it seems to take an anti-West stand it is often because it cannot afford to appear in the eyes of other Africans as a Western puppet…���

Throughout The Jakarta Method, Bevins does an admirable job of addressing commonalities while simultaneously respecting differences���no easy feat. He is aided by the aforementioned survivors of state-organized extermination campaigns, who lend his polemic the authority of firsthand experience. Bevins��� original biographical sketches are deftly woven into accounts of the bigger politico-historical picture, as the author urges us to question received knowledge. ���I fear,��� he writes at one point, ���that the truth of what happened contradicts so forcefully our idea of what the Cold War was, of what it means to be an American, or how globalization has taken place, that it has simply been easier to ignore it.��� But if the truth has been ignored, it has also been actively distorted, as Bevins shows: organized state violence has repeatedly been recast in apocryphal terms���as the ���story of inexplicable, vaguely tribal violence,��� which is, of course, ���so easy for American readers to digest,��� because it plays to (and derives from) a deep-seated ethnocentrism.

One piece of received wisdom that, regrettably, Bevins does not question has to do with World War II. ���In that war,��� he writes in the opening chapter, ���the better angels of American nature came to the fore,��� and ���a generation of American boys came back from that war rightfully proud of what they had done���they had looked an entirely evil system in the face, stood up for the values their country was built on, and they had won.��� This reiteration of the ���Good War��� myth is a rather odd choice for a book about US imperialist violence, though it is likely meant to bolster the author���s assertion that the so-called Jakarta Method was without precedent in American foreign relations. But counterinsurgency was hardly born with the CIA. The US did not require the threat of postcolonial nationalism or trade unionism in order to propose and pursue seismic mitigation strategies. State power, embodied in and exercised through the armed forces, was itself sufficient to motivate all manner of imperialist activities, expansionism being the pulse of the American state project.

Anticommunism was an important pretext for these pursuits, but it was not the first (or the last), and it was scarcely tempered, during World War II, by the marriage of convenience between the US and the Soviet Union. What���s more, an abundance of documentary evidence suggests that it wasn���t pride but bitterness and confusion that characterized that ���generation of American boys��� to which Bevins refers. Not for nothing did the young Norman Mailer describe World War II as a ���mirror that blinded everyone who looked into it.��� The ���Good War��� myth is thus the product of precisely the kind of aggressive disinformation campaign that Bevins so rightly sees as having been applied to populations throughout the third world. During World War II, service members of color well understood their country���s racist devotion to territorial empire. Black men were disproportionately rejected by the Selective Service; those who were ���included��� in war work were subjected to the extreme stresses of life in the Jim Crow military, where simply complaining about segregation was grounds for a psychiatric discharge. The wartime expansion of American military installations was extreme, reaching from Jamaica to the Solomon Islands. On the domestic front, hate strikes were a regular feature of racial strife that extended far beyond Detroit and Los Angeles. The Jakarta Method is not about World War II, but it would certainly benefit from an acknowledgment of some of these realities.

Though Bevins later concedes that ���Washington���s anticommunist crusade had actually started well before World War II,��� the notion that the conflict represented a kind of lull���a period of d��tente���in the US-led opposition to Marxism plays too prominent a part in his opening chapters. Far stronger are the book���s analyses of post-1945 developments. Bevins makes abundantly clear, for instance, that when Truman, speaking in 1947, pledged ���to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures,��� the US president���s sentimentalized reference point was the world���s non-communist population, and only its non-communist population. Bevins��� condensed account of the Truman Doctrine is, however, marred by the factually inaccurate assertion that napalm was used ���for the first time in history��� in 1948, during the Greek Civil War. Developed at a secret Harvard laboratory in 1942, the gel was actually employed extensively���and enthusiastically���throughout the European and Pacific theaters of World War II.

If Bevins��� na��ve reliance on the ���Good War��� myth is troubling, it is partly because of a later reference to Barack Obama, who, with his anthropologist mother, famously lived in Indonesia as a child. Bevins quotes extensively (and uncritically) from Obama���s 1995 memoir Dreams from My Father, in which the future US president describes his dawning recognition of some of the atrocities of Indonesia���s past, those committed with the explicit as well as tacit approval of the US, and partly in the name of the very American imperial project that Obama would himself serve and extend. If Bevins believes the familiar liberal-utopian myth about World War II, perhaps he also believes the one that still surrounds Barack Obama, the ���good��� president. It is difficult to tell. The eighth chapter of The Jakarta Method ends with a block quote from Dreams from My Father. Bevins does not make any direct connections between Obama���s prose, which tells of an early encounter with the harsh realities of power asymmetries, and his presidential legacy. Perhaps he doesn���t need to. The Jakarta Method is damning enough. No reader of this book could possibly come away with the impression that the US was simply a benign observer of the traumas of the latter half of the 20th century. Bevins even underscores the bipartisan nature of the country���s culpability, writing, ���From 1975 to 1979, while both Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter sat in the White House, Washington���s closest ally in Southeast Asia annihilated up to a third of the population of East Timor, a higher percentage than those who died under Pol Pot in Cambodia.���

For its part, Indonesia has undergone transformations emblematized in the word ���Jakarta��� itself. By 1965, that word ���had come to mean not cosmopolitanism, not Third World solidarity and global justice, but rather reactionary violence. ���Jakarta��� meant brutal elimination of people organizing for a better world.��� Today, such peace is available only to those wealthy few who, like Elizabeth Gilbert, author of the memoir Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman���s Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia, travel to Bali (which Gilbert describes as ���a strange and wondrous thing���) in order to ���find themselves������often, as Bevins says, on sands that, not long ago, were littered with corpses. A transnational history of CIA-backed covert actions, The Jakarta Method is essential reading.

September 27, 2020

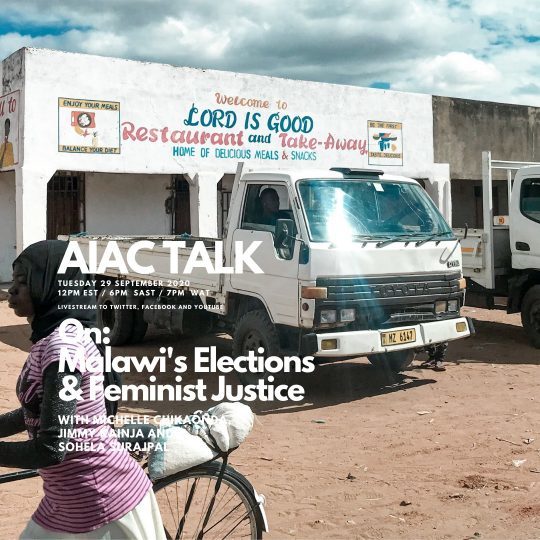

AIAC talks Malawian elections and feminist justice

Last week on AIAC Talk we featured a discussion about the legacy of Kwame Nkrumah. The transcript of the interview with Anakwa Dwamena, who happens to be a contributing editor of Africa Is a Country, and Ben Talton, another frequent contributor and historian, was just published on Jacobin magazine���s website. Watch highlights from all our shows on our YouTube channel, where you can also watch an interview with Grieve Chelwa who is coordinating a project on ���Climate Justice, Tax Justice and Extractives in African spaces.��� (On the site, the series is archived as “Climate Politics.”) To access the entire show���s archive, download or listen as a podcast, subscribe to our Patreon.

Our next episode is this Tuesday, September 29, on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter at 12:00 EST and 17:00 GMT (that’s 6pm in Johannesburg and 5pm in Lagos). In that episode, we will talk to Michelle Chikaonda, a Malawian essayist, who wrote recently about the recent elections in Malawi for Africa Is a Country, and Jimmy Kainja, a media scholar, about what we can learn about the future of democracy from the Malawi example. We will also interview the legal scholar Sohela Surajpal on reimagining what we mean by feminist justice.

September 25, 2020

The linguistic famine

Nick Owuor, via Unsplash.

Ngugi wa Thiong’os acceptance speech for the 31st Catalonia Literature Prize in September was in Gikuyu, his mother tongue. But “the burial of African languages by Africans themselves,” prevented many at home from understanding it. This “linguistic famine,” argues the author, is enabling our own erasure. This post, originally published by The Elephant, is part of a series curated by Editorial Board member, Wangui Kimari.

We all know Kenyans who, after a short stint in the United States, come back home with a mangled American accent���the kind you know is put on or forced and which makes you cringe because you know how much effort it has taken for the speaker to develop it.

It makes you wonder what it is about America that makes people quickly put on accents that are not theirs. Is it lack of self-esteem, or is it a fervent desire to fit into White America? Do people who adopt American accents believe they have a better chance of being assimilated into American society? Or do they believe that they can only move ahead in their careers if they are better understood by their American audiences? Is changing one���s accent a route to career advancement?

The Sri Lankan journalist Varindra Tarzie Vittachi wrote about this phenomenon in his book The Brown Sahib, in which he describes post-colonial Indian administrators and top-level civil servants who became mere caricatures of the British and Britishness when the colonialists left India. Eager to please their former masters, they went to great lengths to adopt British accents and mannerisms���not realizing that: a) they could never pass off as British no matter how hard they tried, and b) by denigrating their own language and culture, they generated even more contempt for themselves among the British, who viewed them as mimicking buffoons who had no dignity or respect for their own culture and identity.

I lived in the United States for five years when I was a student there, but did not come home with an American accent. I think it���s partly because I am multilingual (I���ll explain why this matters later) and also because I don���t like the loud nasal screechy tone of American accents. I find the accent off-putting. It lacks the subtle sensuality of French, the lyricism of Urdu or the sophistication of coastal Kiswahili.

Later on, when I worked in the diverse multicultural environment of the United Nations, I realized that American accents were the minority, and had very little to do with career advancement, so there was no need to put them on. Though race and gender mattered when it came to getting the top management jobs, it was not rare to have a Senegalese with a heavy French-Senegalese accent heading a department or a Russian with very little knowledge of English running an IT section. Most UN staffers are valued not for their knowledge of English, but for their fluency in a variety of languages. So speaking English with an American accent was hardly a plus point.

Kenyans who develop American accents overnight remind me of something Sharmila Sen, an American writer of Indian origin, wrote. In her recently published book, Not Quite Not White, Sen talks about how she used to rehearse speaking with an American accent when her family migrated to America from their native India when she was a child. Her family had moved to Boston from Calcutta and she was afraid that her Indian Bengali accent would be mocked by her classmates. So she spent hours watching American television, learning to speak like the characters in Little House on the Prairie and Dallas (probably not realizing that accents vary across America; Texans speak with a specific drawl that is quite distinct from the speech pattern of someone born and raised in New England).

When the twelve-year-old Sen arrived in America with her immigrant parents, she was fluent in three languages: Bengali, Hindi, and English. But in her almost all-white school, she pretended that she did not know any Indian language and did not even watch Indian movies, even though she loved them. She was afraid that her classmates might find out that Bengalis eat with their hands and that she would be the laughing stock of the entire school, so she never invited friends home. Her parents, keen to assimilate in their new country, insisted on using forks and knives, even though they had little desire to use them. She says she and her family didn���t want to be associated with ���fresh off the boat��� people in America, who fail to assimilate into American society, and live cocooned lives in ghettoes. Most importantly, she didn���t want to appear ���threatening, unnatural, or ungrateful.���

She also smiled a lot, which she says is common among brown and black people living in America. As an African American man, a fellow doctoral candidate, explained to her, ���We smile because it is the only face we can show. If we stop smiling, they will see how angry we are. And no one likes an angry black man.���

Sen says that as she grew older and understood white privilege, she decided to ���go native��� and not smile too much because she was tired of being the entertainer, the storyteller, the explainer of all things Indian to white audiences. She also did not want her sons and daughter to be viewed as ���people of color��� (a designation she resents).

Another writer who decided to go truly native is our very own Ng��gi wa Thiong���o. In Ng��gi���s case, not only did he not adopt an American accent when he went into self-imposed exile in the US, but he decided to abandon the English language altogether in favor of his mother tongue, G��k��y��. Perhaps that is why his acceptance speech for an award he received recently was entirely in his native tongue.

Ng��gi believes that when you erase a people���s language, you erase their memories. And people without memories are rudderless, unconnected to their own histories and culture, mimics who have placed their memories in a ���psychic tomb��� in the mistaken belief that if they master their colonizer���s language, they will own it. Because erasure of memory and culture is a condition for successful assimilation, the burial of African languages by Africans themselves has ensured their total immersion into colonial culture. He calls this phenomenon a ���death wish��� that occurs in societies that have never fully acknowledged their loss���like trauma victims who resort to drugs to kill the pain.

Many people of my generation are multilingual because they were encouraged to speak their mother tongue at home. While I was taught in English in school, I learned to speak and understand Hindi and Punjabi at home and picked up Kiswahili on the streets. Later, I picked up a bit of French in high school, and Urdu as well, because my father loved Urdu poetry and ghazals.

All these languages have enriched my life in ways that would not have been possible had I not learned them. Without them, I would have never been able to understand the subtle meanings and nuances embedded in certain Punjabi words. I would not have been able to communicate with my grandmother or watch and enjoy Bollywood films. Nor would I have realized that President Moi���s speeches in English were very different in meaning and tone from his speeches in Kiswahili. I would not have developed an understanding of my own and other people���s cultures or developed empathy and tolerance for other races and ethnic groups had I not been multilingual. Language is the pathway to a culture���s soul.

Sadly, the generations that come after me have abandoned their native tongue in favor of English. Some parents even encourage their children not to speak their mother tongue at home because it might ���contaminate��� their English accent.

At a public lecture he gave at the University of Nairobi a few years ago, Ng��gi derided Kenyan parents for discouraging their children from speaking their mother tongues, a phenomenon that has led to what he called a ���linguistic famine��� in African households. This would never happen in countries such as Germany or France, where German and French children learn their own language before they learn English. Nor would it happen in China, India or Brazil, all of which are emerging economies. (I have yet to meet a Chinese person who feels ashamed about not knowing English.)

Even in neighboring Tanzania and Somalia, people become fluent in Kiswahili and Somali, respectively, before they learn other languages. A few years ago, I participated in a two-day local government meeting in Dar es Salaam which was conducted in just in one language ��� Kiswahili. Like many Kenyans who visit Tanzania, I became painfully aware of the fact that my mastery of this beautiful language was woefully inadequate. My only (lame) excuse for this is that in my school days, Kiswahili was not a mandatory subject.

Knowledge of many languages promotes inter-cultural dialogue and understanding, and is essential in a globalizing world. If Kenyans are to be successful citizens of the world, they must learn their own and other people���s languages. And we should stop putting on accents just to impress others. Putting on an accent that is not natural is not just silly and painful to watch; it is also a sign that those who feel compelled to change their accents have a large amount of self-loathing going on, which is just plain sad.

The late Wangari Maathai said that ���culture is coded wisdom���, and must be preserved. Language is one of the vehicles through which that culture is transmitted. We must preserve our languages for the sake of present and future generations.

Beyond African royalty

Still from Black Is King.

The year is 2020. The Lion King, Disney���s beloved classic���a tale about an anthropomorphized pride of royal lions���has bizarrely secured its place at the heart of a growing canon of redemptive narratives of blackness���of Africa���on screen. Beyonc�� has reframed the animal tale, and turned it into a stunning visual album���Black Is King. The film premiered a month ago in the United States, and was made available on the African continent for only 24 hours on one of Africa���s most expensive satellite service providers.

The film has all the strengths and flaws of the American superstar. Like Beyonc�� herself, Black Is King is at once empowering and stilting in its contradictions. Globalized Black women watching Beyonc�����wherever we happen to live���are able exercise our bodily autonomy. We are at liberty to inhabit a range of selves. Her aesthetic allows those in business suits or with weaves or long-ass acrylic nails to claim space without shame and to pay no mind to those who challenge us on grounds of ���decorum.���

Yet, Black Is King sits uncomfortably. Like much of Bey���s highly curated persona, it is evident to this African woman, that I am likely not included in her imagined audience. Africa and its people are peripheral props in her version of Blackness.

In recent years, themes centering the African heritage of Black people globally have gained prominence in popular media. Yet Western media remains hegemonic and Western sensibilities continue to be privileged.�� This means that even films and TV shows that purport to center Black people who are also Africans (Black Africans) are not for us. As Black American identity in particular has ���gone global���, with Beyonc�� as its chief ambassador, Black Africans have had to learn to make do with morsels of representation. No matter how carefully curated, and no matter how breathtakingly delivered, images of Africa continue to be deeply problematic, hewing to old, frustrating tropes.

The entwined histories of Black Americans and Black Africans are complicated. They are fraught with gnawing tensions birthed by violent estrangement. These chasms show up everywhere: in the academy, in television shows and in think pieces that have come to form part of ���diaspora wars.���

These diaspora wars reveal themselves in the dissonant opinions Black Africans and Black Americans have of ���African-themed��� film and media produced in the West. As Black Americans seek to reclaim a lost past, Africans shift uncomfortably in their seats. Black Panther played with romanticized notions of Africa. Yet even as the cries of ���Wakanda Forever��� had died down in the US, Africans on the continent were debating the merits of Black fantasy. Black Is King has already inspired similar conversations.

Like Black Panther, Black Is King is fixated on themes of royalty. The titular Black Is King resounds as refrain throughout the visual album. It is apparent in how notions of severed ties and returns to the ancestral are artfully explored. Indeed, rather than creating a generic Africa, Black Is King departs from multiple points of specificity. It references religious Yoruba imagery, features the Kanaga masks and celestial charting of the Malian Dogon, and nods to various other indigenous mythologies and cosmologies from across the continent through its fashion and narrative. (It at times is so specific to places that are far removed from one another on the continent that I wonder if a layperson on the streets of Lilongwe or Luanda might readily recognize its references without explanation. The demonization and erasure of African beliefs and knowledge systems is, after all, as much a product of colonial rule on this continent as it was of chattel slavery in the Americas).

However noteworthy it is in its specificity, the film also makes some strange choices. In one of the most striking scenes, which closely precedes the song�� ���Mood 4 Eva,��� the camera pans onto the grounds of an ostentatious palace as Mbube (���The Lion Sleeps Tonight���) plays.

Wimoweh…Wimoweh…Wimoweh…Wimoweh…

This scene feels familiar. The camera cuts into a bejeweled bedroom, where a sleeping Beyonc�� is roused from her slumber by the sound of a violin.

This scene is familiar. It is exactly how Prince Akeem awakens in Coming To America��� another beloved Black American classic. As if Mufasa���s wisdom, interspersed throughout the film in his stately, orotund voice is not enough, this moment of cinematic nostalgia punctuates the refrain: Coming to America���s Zamunda says Black Is King more emphatically than Pride Rock ever could. But one wonders why a film that seems to spoof Africans deserved such homage in one that professes to be for us all.

Released in 1988, Coming to America grossly under-complicated Africa. The film was about an ���African Prince,��� from a fictionalized land called Zamunda. Eddie Murphy played the lead role as Prince Akeem, and he was chaperoned by Semmi, who was played by Arsenio Hall. Prince Akeem travels to America to ���sow his wild royal oats��� one last time before he is married off to an African woman. He lands in New York and (obviously) goes straight to Queens to find a paramour.

Predictably, the film thrived on reductionist typecasting. It was a parody of�� Africa even as it pretended to pay homage to the continent as ���motherland.��� Throughout the film, Semmi hurls absurd insults. ���You sweat from a baboon���s balls��� he says at one point. Later in the film, he exclaims that something is, ���hippopotamus shit.��� These phrases are laughable, and not because they���re funny. In the gratuitous referencing of wild animals���as though that is the only way into Africa���it is evident that Africans are the butt of the joke.

Zamunda���like Wakanda���relies on notions of royalty, material power and dominance. Its aspirational framework raises questions.�� What is the fixation on royalty in our myth and truth-making? What does it mean for all the Black people who have ever lived���not as royals but as regular folk? The questions raised by these hyperbolized fictional imaginaries are not directed at Black Americans alone.�� They are seductive for many within African audiences on the continent as well.

Still, these representations are easily shrugged off by those whose umbilical cords are buried in African soil. For those whose ancestors were stolen and sold in slavery, the appeal of royalty remains resonant.

Last year during Ghana���s Year of Return, African-American actress Lisa Raye announced her ���crowning��� as ���Queen Mother of Ghana.��� There is of course no such thing. Ghana is a modern state���the product of colonization. The Ashanti, Fanti and other nations have various royal leaders���but the state certainly does not. Raye was seemingly unaware of this fact. Duped by enterprising Ghanaians who had sold her a fabricated Queen motherhood, Raye went on a mini media tour, flying her newly dubbed title high without a hint of irony.�� Ghanaians everywhere were flabbergasted.

The ideas of Africa in Coming to America and Black is King uncritically cast Africa as a place that can be returned-to, a place of kings and queens who are untethered to the world���s political economies. The imagined Africa that allows Lisa Raye to be Queen Mother, or lets Eddie Murphy���s Akeem have an unlimited budget, pretends that slavery and colonization did not have a structural and systemic effect on the continent and its people. The Africa to which they return is lodged in a permanent state of primordial waiting. It is an Africa that was not wounded by their departures. There is no space for mourning and loss in these renderings of Africa and there certainly aren���t any ways for African cities to be what they are���complicated and uneven and distinctly un-royal.

Must Black be king? What if Black is pauper, apprentice, farmer, radical scholar? What if Black is non-binary? What if it does not fit neatly into this gendered notion of kinghood? What if Africans are not royals, but instead are mothers in markets, grandmothers on the outskirts, children at the rugged intersections of indigeneity and modernity, with neither territory nor subjects?

There are flickers of hope.�� Beyonc�� knows that Africa is not a country, and that it lives beyond her imagination. She knows this because the scenes of urban West Africa are too vivid to be ignored. She knows this because her list of credits to African creatives is long. And yet she still insists in this latest work, on pursuing an under-interrogated preoccupation with nobility. Putting what she knows of Africans in conversation with what she wishes to express on film is an important next step. If there is a global Black person who can open up opportunities for usurping the metaphor of monarchy in order to expand the possibilities of what a worthy Blackness and Africanness is and looks like, it is Beyonc��. She has the wealth and the reach to shift debates and this is at once a burden and threat.

To be clear, I am not arguing that we will only find the sweet spot when we turn the camera lens away from what is rural and marginal. Quite the opposite. I am drawn to reframing the disregarded parts of Africa. I am interested in engaging what is down in the dirt and dignified without romanticizing poverty and suffering. This is a different kind of ideation. It is these deeply complicated liminal spaces that are worthy of examination, of visual treatment and of Beyonc��-level production. This is where most of us on this continent live.

If we look beyond the confines of royalty, we just might find one another.

September 24, 2020

The pitfalls of African consciousness

Still from Black is King.

African American imaginings of Africa often intermingle with���and help illuminate���intimate hopes and desires for Black life in the United States. So when an African American pop star offers an extended meditation on Africa, the resulting work reflects not just her particular visions of the continent and its diaspora, but also larger aspirations for a collective Black future.

Black is King, Beyonc�����s elaborate, new marriage of music video and movie, is a finely-textured collage of cultural meaning. Though it is not possible, in the scope of this essay, to interpret the film���s full array of metaphors, one may highlight certain motifs and attempt to grasp their social implications.

An extravagant technical composition,��Black is King��is also a pastiche of symbols and ideologies. It belongs to a venerable African American tradition of crafting images of Africa that are designed to redeem the entire Black world. The film���s depiction of luminous, dignified Black bodies and lush landscapes is a retort to the contemptuous West and to its condescending discourses of African danger, disease, and degeneration.

Black is King��rebukes those tattered, colonialist tropes while evoking the spirit of pan-African unity. It falls short, however, as a portrait of popular liberation. In a sense, the picture is a sophisticated work of political deception. Its aesthetic of African majesty seems especially emancipatory in a time of��coronavirus, murderous cops, and vulgar Black death. One is almost tempted to view the film as another iteration of the principles of mass solidarity and resistance that galvanized the Black Lives Matter movement.

But��Black is King��is neither radical nor fundamentally liberatory. Its vision of Africa as a site of splendor and spiritual renewal draws on both postcolonial ideals of modernity and mystical notions of a premodern past. Yet for all its ingenuity, the movie remains trapped within the framework of capitalist decadence that has fabulously enriched its producer and principal performer, Beyonc�� herself. Far from exotic, the film���s celebration of aristocracy and its equation of power and status with the consumption of luxury goods exalts the system of class exploitation that continues to degrade Black life on both sides of the Atlantic.

That said, the politics of��Black is King��are complicated. The picture is compelling precisely because it appears to subvert the logic of global white supremacy. Its affirming representations of Blackness and its themes of ebony kinship will resonate with many viewers, but will hold special significance for African Americans, for whom Africa remains an abiding source of inspiration and identity. Indeed,��Black is King��seems purposefully designed to appeal to diasporic sensibilities within African American culture.

At the heart of the production lies the idea of a fertile and welcoming homeland.��Black is King��presents Africa as a realm of possibility. It plays on the African American impulse to sentimentalize the continent as a sanctuary from racial strife and as a source of purity and regeneration. Though the movie does not explicitly address the prospect of African American return or ���repatriation��� to Africa, allusions to such a reunion shape many of its scenes. No doubt some African American viewers will discover in the film the allure of a psychological escape to a glorious mother continent, a place where lost bonds of ancestry and culture are magically restored.

The problem is not just that such an Africa does not exist. All historically displaced groups romanticize ���the old country.��� African Americans who idealize ���the Motherland��� are no different in this respect. But by portraying Africa as the site of essentially harmonious civilizations,��Black is King��becomes the latest cultural product to erase the realities of class relations on the continent. That deletion, which few viewers are likely to notice, robs the picture of whatever potential it may have had to inspire a concrete pan-African solidarity based on recognition of the shared conditions of dispossession that mark Black populations at home and abroad.

To understand the contradictions of��Black is King, one must examine the class dynamics hidden beneath its spectacles of African nobility. The movie, which depicts a young boy���s circuitous journey to the throne, embodies Afrocentrism���s fascination with monarchical authority. It is not surprising that African Americans should embrace regal images of Africa, a continent that is consistently misrepresented and denigrated in the West. Throughout their experience of subjugation in the New World, Black people have sought to construct meaningful paradigms of African affinity. Not infrequently, they have done so by claiming royal lineage or by associating themselves with dynastic Egypt, Ethiopia, and other imperial civilizations.

The danger of such vindicationist narratives is that they mask the repressive character of highly stratified societies. Ebony royals are still royals. They exercise the prerogatives of hereditary rule. And invariably, the subjects over whom they reign, and whose lives they control, are Black. African Americans, one should recall, also hail from the ranks of a service class. They have good cause to eschew models of rigid social hierarchy and to pursue democratic themes in art and politics.��Black is King��hardly empowers them by portraying monarchy as a symbol of grandeur rather than as a system of coercion.

There are other troubling allusions in the film. One scene casts Beyonc�� and her family members as African oligarchs. The characters signal their opulence by inhabiting a sprawling mansion complete with servants, marble statues and manicured lawns. Refinement is the intended message. Yet the conspicuous consumption, the taste for imported luxury products, the mimicry of European high culture and the overall display of ostentation call to mind the lifestyles of a notorious generation of postcolonial African dictators. Many of these Cold War rulers amassed vast personal wealth while their compatriots wallowed in poverty. Rising to power amid the drama of African independence, they nevertheless facilitated the reconquest of the continent by Western financial interests.

Black is King��does not depict any particular historical figures from this stratum of African elites. (Some of the movie���s costumes pair leopard skin prints with finely tailored suits in a style that is reminiscent of flamboyant statesmen such as Mobutu Sese Seko of the Congo.) However, by presenting the African leisure class as an object of adulation, the film glamorizes private accumulation and the kind of empty materialism that defined the comprador officials who oversaw Africa���s descent into neocolonial dependency.

Black is King��is, of course, a Disney venture. One would hardly expect a multinational corporation to sponsor a radical critique of social relations in the global South. (It is worth mentioning that in recent years the Disney Company has come under fire for allowing some of its merchandise to be produced in Chinese sweatshops.) Small wonder that Disney and Beyonc��, herself a stupendously rich mogul, have combined to sell Western audiences a lavishly fabricated Africa���one that is entirely devoid of class conflict.

Anticolonial theorist Frantz Fanon once warned, in a chapter titled ���The Pitfalls of National Consciousness,��� that the African postcolonial bourgeoisie would manipulate the symbols of Black cultural and political autonomy to advance its own narrow agenda.��Black is King��adds a new twist to the scenario. This time an African American megastar and entrepreneur has appropriated African nationalist and pan-Africanist imagery to promote the spirit of global capitalism.

In the end,��Black is King��must be read as a distinctly African American fantasy of Africa. It is a compendium of popular ideas about the continent as seen by Black Westerners. The Africa of this evocation is natural and largely unspoiled. It is unabashedly Black. It is diverse but not especially complex, for an aura of camaraderie supersedes its ethnic, national, and religious distinctions. This Africa is a tableau. It is a repository for the Black diaspora���s psychosocial ambitions and dreams of transnational belonging.

What the Africa of��Black is King��is��not��is ontologically African. Perhaps the African characters and dancers who populate its scenes are more than just props. But Beyonc�� is the picture���s essential subject, and it is largely through her eyes���which is to say,��Western��eyes���that we observe the people of the continent. If the extras in the film are elegant, they are also socially subordinate. Their role is to adorn the mostly African American elites to whom the viewer is expected to relate.

There are reasons to relish the pageantry of��Black is King, especially in a time of acute racial trauma. Yet the movie���s mystique of cultural authenticity and benevolent monarchy should not obscure the material realities of everyday life. Neoliberal governance, extractive capitalism, and militarism continue to spawn social and ecological devastation in parts of Africa, the Americas, and beyond. Confronting those interwoven realities means developing a concrete, global analysis while resisting metaphysical visions of the world.

How to Curate a Pandemic

[image error]

Sabelo Mlangeni, A Selfie with Social Media Influencer James Brown at a Party (from the series "Royal House of Allure"), 2019. Courtesy blank projects, Cape Town

There is an institutional and cultural reckoning with legacies of racism, oppression, and inequity unfolding within and around global art institutions. COVID-19 forced the mass closure of museums and staff layoffs, exposing the inequalities of the art world and raising questions about the role of museums as institutions of care. The continual and unjust killing of black people by police (especially in the United States), and the widespread protests and calls to action that resulted, have only heightened concerns over the staffing, exhibiting, and collecting practices of the global art market. Longstanding calls for dismantling exclusionary practices and the need to reimagine museums have gained new urgency.

The continent of Africa and the disciplinary field of African art is no stranger to discussions of racism, institutional imagination, and calls for decolonization. Before the pandemic and protests, the Felwine Sarr and B��n��dicte Savoy Report (commissioned by the French government; Sarr is a Senegalese economist and musician and Savoy a French art historian) called for the return of African artworks held in French museum collections. In tandem, artists and curators based on the continent and in the diaspora spearheaded a number of pathbreaking exhibition platforms that challenged how people think about African art as a field of study, and rethink the role of museums and curators. Africa Is a Country contributor Drew Thompson asked three prominent curators���Antawan Byrd (Associate Curator of Photography and Media, Art Institute of Chicago), Sandrine Colard (Assistant Professor of African Art History, Rutgers University, Newark), and Serubiri Moses (Writer and Adjunct Assistant Professor, Hunter College)���to�� comment on how they are (re-)situating their respective curatorial practices in relation to the current moment.

The Way She Looks Exhibition. Image credit RIC.

The Way She Looks Exhibition. Image credit RIC.Drew Thompson

I know you each had done or planned major curatorial projects. Could you speak to what those projects were and where they stand?

Antawan Byrd

My most recent project was the 2nd Lagos Biennial of Contemporary Art (2019), for which I was one of three curators, working with Oyindamola Fakeye and Tosin Oshinowo. We brought together 40 artists���half based in Nigeria and the others practicing internationally���whose work explored questions of architecture, urbanism, and the built environment. Some of the spatial concerns central to the biennial resonate with several other projects I���m currently working on at the Art institute of Chicago, including a forthcoming solo exhibition of new work by Kenyan artist Mimi Cherono Ng���ok that will open next year. The show will elaborate on Ng���ok���s abiding interest in using photography to bridge experiences of disparate locales and how botanical life informs experiences of place across the Global South.

Sandrine Colard

2019 was a very busy year for me. I curated three shows on three continents. Based on the holdings of the Artur Walter Collection, The Ways She Looks was an exhibition last fall at the Ryerson Image Center about women���s portraiture and female gazes throughout African photography history. The Wiels Contemporary Art Center in Brussels invited me to curate a show with works by African artists who had been in residence. The result was the exhibition Multiple Transmissions: Art in the Afropolitan Age, showcasing Georges Senga, Simnikiwe Buhlungu, Sinzo Aanza, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Jean Katambayi, Nelson Makengo, P��lagie Gbaguidi, and Emeka Ogboh; and, it reflected on the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe���s idea of ���Afropolitanism��� in relation to the phenomenon of artist residencies, as well as individual artists��� physical and mental mobilities, their artistic legacies, and the transmission of their works. Finally, I curated the 6th edition of the Lubumbashi Biennale, which I called Future Genealogies: Tales from the Equatorial Line. By positioning Congo on the equator and framing the equator as an imbrication rather than an imaginary line, the biennale presented 30 African and other international artists who map new connections and genealogies artistically, politically, socially, and ecologically.

Serubiri Moses

I worked previously as a curator with the Berlin Biennial of Contemporary Art, and Kunst Werke Institute for Contemporary Art in 2017 and 2018. It���s hard to historicize this project, but when asked about it, I often talk about the effort at working primarily through commissioned artworks and artist residencies. Work produced in this method made up about three-quarters of the final exhibition. In such a case, the 10th edition invited many artists to Berlin, where they spent several weeks prior to the exhibition, working on the site; though some residencies took place outside Germany, such as in India. As an exhibition, it brought a strong focus to practitioners in Latin America and the Caribbean. It was an ambitious exhibition, which intentionally pulled back the scale of production that we have witnessed in the past two decades. I am currently working towards a survey of contemporary art at MoMA PS1, as a guest curator working alongside curatorial staff at MoMA and MoMA PS1, and that work is only at the beginning stages.

Drew Thompson

As you executed or conceptualized your respective projects, what most surprised you about interest in and audience reception of contemporary African art?

Antawan Byrd

When I returned to Lagos in 2018 to pursue biennial research, I was blown away by the city���s range of new art and cultural initiatives, particularly experimental art platforms like Treehouse founded by Wura Natasha-Ogunji, and the growth of a subculture/skate scene cultivated by WAFFLESNCREAM. I could sense that the city���s art public had changed, partly spurred, I think, by a recent influx of Nigerians returning to Lagos after living abroad. Such perceptions helped mitigate some anxieties I had about particular commissions I wanted to pursue. One of these was South African artist Sabelo Mlangeni���s Royal House of Allure (2019), a phenomenal photographic essay produced for the biennial during the artist���s six-week residency in Lagos. The series chronicles the daily activities of LGBTQIA+ subjects who live together in a safehouse designed to provide support and shelter for members of this community. Given the conservative, and at times oppressive, regard for LGBTQIA+ subjects in Nigeria, we were keen to include work that spoke about the crucial role that housing plays in extending social protections to marginalized groups in the country. Mlangeni���s photographs achieved this in such a critical way, the reception was great and took me by surprise.

Antawan Byrd.

Antawan Byrd.Sandrine Colard

While curating the Lubumbashi Biennale, I was continually mesmerized by the pure and

undeterred energy deployed by the local community of artists to pursue their practice and make

the event possible, in spite of all the difficulties. The Biennale was founded by PICHA!, a collective of artists, including the photographer Sammy Baloji. The number of artists for a city of two million people, and the quality of their work, is truly amazing. Other artist-based initiatives have flourished, such as Centre Waza, KinArt Studio, and Eza Possible in Kinshasa. All these spaces have become central to the dynamism of the Congolese arts ecosystem, and have stepped in where government assistance is absent. This was the 6th edition of the Biennale, and it

benefited from the works of all the curators who came before me. It has grown tremendously, and this time it was extremely rewarding to see the expansion of its international audience. I think more and more people realize that you cannot be interested in contemporary African art and be content with seeing it only in New York City or Paris.

Serubiri Moses

A crucial aspect for me as a curator was the question of becoming, which was borrowed from psychoanalytic readings of Chilean biologist Francisco Varela���s term ���Autopoiesis.��� These readings emphasized that while ���sameness��� is a dominant theme in Sigmund Freud, difference operates more directly in this process of becoming as a part of un-making and re-making. I think this implied a direct confrontation with historical anxieties about ���being���, and assumptions about various forms of subjectivity. This definitely includes categories of art. It was important to recognize the erasures. An example that was central to the curatorial team of the 10th Berlin Biennale was the empty plinth on which the Cecil Rhodes statue had sat for eighty years, after its removal during the #RhodesMustFall campaign in 2015. As Gabi Ngcobo, the convening curator asked in their catalogue essay, “What future possibility does this open space hold or enable us to foretell?” This was not about championing the postcolonial as a monumental break from white rule, or indirect colonial rule; but rather it was about interrogating the conditions of participation. It was also an opportunity to reflect on events that led to the fall of the Berlin wall, this reflected in artworks notably by Dineo Seshee Bopape. Elsewhere, we wondered if the planting of Mugumo trees, symbolic in their spiritual and cultural significance in Kenya, signified an alternative history?

Drew Thompson

Where in the field of curating African, African-American art, and diaspora is there room for development? What kinds of questions have plagued the field and how are you and the artists you exhibited grappling to break free of these questions and/or chart new lines of sight?

Antawan Byrd

Recently I���ve been obsessed with the history of exhibitions in Africa. The importance of this is something that the much-missed curator Bisi Silva stressed in her work and to the many curators she influenced. While there is fairly ample scholarship and documentation on African art exhibitions that occurred in the West, there is a lot of work to be done on the history of exhibitions on the continent prior to, say, the 1980s. Exhibition documentation offers critical knowledge about audiences and the kinds of ideas and narratives imputed to artworks at the time of their public debut; it���s very easy for this insight to become divorced from objects over time. Moreover, such histories are essential to reorienting exhibition canons, which tend to focus on shows in Europe or America. Fortunately, there���s some exciting work being done, especially in the realm of archives and anthologies. Lately I���ve been studying the impressive FESTAC ���77 compendium that Chimurenga published last year with the arts publication Afterall as part of the latter���s Exhibition Histories series.

Sandrine Colard

When it comes to curating African art, and Congolese art in particular, I have constantly worked to correct the under-representation of female artists. The contingent of Congolese women artists for this edition of the Lubumbashi Biennale has been one of the most important so far, and I am very happy to see some of them gaining international recognition for the works that they showed. Gosette Lubondo is a nominee for the CAP Prize; Pamela Tulizo has just won the prestigious Christian Dior Prize from Arles Photography Festival. Others, like Hadassa Ngamba, were able to come to Europe to pursue an artistic education. But I also strongly resist the gender pigeonhole, and an exhibition like The Way She Looks was precisely conceived around the idea of turning on its head the sort of perpetual focus of women artists as working on exclusively feminist issues and the question of the body. Artists like Lebohang Kganye and Mimi Cherono Ng���ok are great examples of that. I am a big admirer of the work of the American painter Jordan Casteel, and how she, as a black female artist, paints the black male body.

Sandrine Colard.

Sandrine Colard.Serubiri Moses

Curating as a practice is still under revision. American art historian Hal Foster���s recent book, What Comes After Farce? (Verso, 2020) on Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist is a good example of the debates that are emerging from recent analyses. Foster and others use specific disciplinary tools to try and categorize the work Obrist is doing, without much success. Between Obrist and American art historian Bruce Altschuler, there is a major difference in approaches and methods to the question of curating. Methods in curating African art vary greatly and are hard to place. Constantly keeping abreast of the field and studying both its history and its present is crucial.

Drew Thompson

In recent weeks, we have been barraged by images of police brutality and the cruelty of COVID-19 on communities of color. We have also been inspired by the protests in the wake of police brutality in the US and elsewhere. How do you read and situate these dramatically��differing images? Also, how are these images informing how you think of your roles as scholars and curators?

Antawan Byrd

As a curator of photography, I���ve been really interested in the kinds of violence and transformations that images endure in the process of exposing and redressing anti-black racism. At the Art Institute, I recently co-curated an exhibition of anti-apartheid political posters by the Medu Art Ensemble, which is the subject of a forthcoming catalogue I co-edited with Felicia Mings. I spent a lot of time thinking about the history of anti-apartheid iconoclasm and how, during the ���70s and ���80s, Medu���s posters participated in a visual economy of protest that was partly driven by the reworking and recirculation of images of violence. I think about this today, when I see stills from the George Floyd video appearing on placards during protests, or when one looks at how the quality of the video degrades as a consequence of its widespread circulation. So, beyond efforts to personally reckon with these images and the systems of oppression that produce them, I try to situate such imagery within a broader historical continuum. Elizabeth Alexander���s classic essay, ���Can You Be BLACK and Look at This?��� is exemplary of this kind of work, with its linking of the Rodney King video to images of Emmett Till and 19th century narratives of violence written by enslaved subjects.

Sandrine Colard