Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 161

August 30, 2020

Utopias, joy, and the law

Wanuri Kahiu. Image via author.

��� Wanuri Kahiu, April 29, 2019; TwitterThe courts did not rule in our favour today. A sad blow for Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Speech in Kenya. But we believe in our constitution and are glad we have the right to defend it. We will appeal! A luta continua!

In Rafiki, filmmaker Wanuri Kahiu adapted the award-winning short story ���Jambula Tree��� by Ugandan author Monica Arac de Nyeko and transposed the deeply affecting and richly textured story of love and discovery between two young women to the vibrant, bustling streets of Nairobi. In 2018, Rafiki became the first Kenyan film to screen as part of the prestigious Un Certain Regard program at the Cannes Film Festival, to great acclaim. Following this world premiere, the Kenya Film and Classification Board announced the film would be banned in Kenya ���due to its homosexual theme and clear intent to promote lesbianism in Kenya contrary to the law.��� Kahiu sued the government over unconstitutional infringements on freedom of expression, which led to a temporary lifting of the ban to allow the film to screen to packed Kenyan audiences for two weeks and qualify for the Oscars. With the ban reinstated, Kahiu continued to appeal the judicial order over the next two years. On 29 April 2020, a High Court in Kenya upheld the 2018 ban. Immediately following the court���s ruling, the Creative Economic Working Group of Kenya put out an official press release denouncing the ban.

This interview was conducted before the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many others, and the global protest movement against anti-Black racism that persisted and followed in its wake. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Julie MacArthur

On 29 April 2020, a High Court in Kenya upheld the 2018 ban on your film Rafiki. Given our current circumstances, I understand the case was held and verdict delivered over zoom. How surreal was this moment for you, defending a case of ���freedom of expression��� in a time of such widespread crisis and arguably increased need for the defense of ���freedom of expression��� and respect for human rights and constitutionality?

Wanuri Kahiu

It���s mixed because there���s so much going on in the world and there���s such a need to address the global crisis but at the same time there have been such violations of freedom of speech and freedom of expression recently as a result of the crisis as well (increased attack on journalists by police) and we know that if your right to freedom of speech and freedom of expression is threatened then it makes it harder to advocate for any other rights. So it���s mixed. We know it kind of seems like it���s not the most important thing at the moment but at the same time it���s incredibly important because that���s the only way we can ensure that people���s rights are being met, even as the current crisis continues.

Julie MacArthur

It seems actually incredibly timely, strange but timely, that you���re leading this struggle at this moment.

Wanuri Kahiu

Yeah, but I think that any moment is the moment. There���s no good time and there���s no bad time, unfortunately. Especially because, past this, we realize that this is about one film, but it���s such a continent-wide problem. There are so many artists being attacked for what they���re singing, what they���re drawing, their depictions in film, so it���s much larger than that. In times of crisis, there seems to be a further crackdown on these things, so there will never be a good or a bad time, there will just be the time to fight, and that���s what we���re doing.

Still from Rafiki.

Still from Rafiki.Julie MacArthur

Language and history seem so important here. In 2018, the ban [on your film Rafiki] was temporarily lifted by Justice Wilfrida Okwany, whose ruling stated that ���I am not convinced that Kenya is such a weak society whose moral foundation will be shaken by simply watching a film depicting gay themes ��� The undisputed fact is that ��� the practice of homosexuality did not begin with the film Rafiki.��� We could add neither did censorship nor the belief that Kenyans, or Africans more broadly, need to be ���protected��� from certain kinds of content. The Kenya Film Classification Board under CEO Ezekiel Mutua relied on the Films and Stage Plays Act, legislation passed under the British colonial government in 1962 on the eve of independence, legislation that is very similar, in language and intent, to the original 1912 act, ���The Stage Plays and Cinematography Exhibitions Ordinance,��� which was used to censor Hollywood films in particular, to shield ���susceptible��� African audiences from ���undesirable ideas such as kissing, sex, shooting, and nudity.���

And we could continue, looking at the colonial roots of anti-homosexual laws. Activist, poet, and scholar Stella Nyanzi wrote a great piece in 2011 entitled ���Unpacking the [govern]mentality of African sexualities��� in which she argued that ungoverned sexuality threatened the idea of women as symbols of tradition, control, and stability. And we can easily take this out of the realm of ���sexuality��� if we put it within the lineage of the struggles of intellectuals and activists like Ngugi wa Thiong���o, Wangari Maathai, Boniface Mwangi, and many others.

What do you think this ruling, quoting Justice Makau, ���to protect society from moral decay,��� tells us about the legacies of colonialism and postcolonial use of governance and judicial practice to police morality?

Wanuri Kahiu

I think there���s such a disconnect in that already, right? Because what is promoted is this idea of protecting African ideals, and it���s said over and over again: protecting the African family, protecting Kenyan morality. But, the truth of the matter is that we���re just protecting colonial legacy. The contradiction is so glaringly obvious – tracing back the roots of this current law, it goes back to sedition laws, where colonialists were trying to silence anti-colonial voices and anti-colonial propaganda. I feel strongly that the anti-freedom of expression movement is a colonial movement still. It���s a conflict that we are democratic nations now but still perpetuating colonial laws that were made against us: that were made to debilitate us; that were made to oppress us; that were made to create false narratives about us; that literally took our voices away to the point that most of our history is no longer written by us and we���re not contributing to it, apart from the fact that we are all historians. But the idea that so much of identity has been taken away from us by these laws, and these are the laws we are now reinforcing, feels very tragic. Deeply complexing and very tragic.

Julie MacArthur

I���m reminded of the late Binyavanga Wainaina���s comment that it is not homosexuality that is ���un-African,��� it���s anti-homosexuality laws���the epitome of Victorian ideals.

Wanuri Kahiu

Exactly, homophobia is un-African. I really believe that is the thing we should be targeting.

Julie MacArthur

[Kenya Film Classification Board under CEO Ezekiel] Mutua went so far as to take to Twitter to claim: ���you want gay films? Go to countries that have legalized that practice.���

Wanuri Kahiu

Is that what he said? {laughter}

Julie MacArthur

Yes, so this is a slightly facetious question: can a film be ���gay���?

Wanuri Kahiu

{Laughter} Just like can a film be murderous? Mutua is illogical at best. Anyone that can see through it can see that he is using this agenda to advance his own ideology and ambition. It���s so curious, because there are many legal films and TV shows that play within Africa that have LGBTIQ themes in them, because that���s human nature. We���re human, and that���s human nature. Rocketman played in the cinemas, and there was no problem. It���s the fiction of Africans having same-sex relationships, that���s the problem. So it���s as if even by ourselves we are being excluded from the whole breadth of humanity.

Julie MacArthur

And on that line, one of Mutua���s defenses has been that he asked you politely to change some of the scenes and that would have solved the problem. From what I���ve gathered, it was particularly the ending ���

Wanuri Kahiu

It wasn���t particularly the ending, it was only the ending. Because it wasn���t remorseful enough, that���s the word that he used.

Julie MacArthur

That is striking. While following a Romeo and Juliet structure, the film does end on a different note. In a review I wrote of the film, I ended with this: ���As Kena [one of the protagonists] says of her pink-and-purple dreadlocked love interest, this film may not be the ���typical African��� film many have come to expect. But perhaps, as its final image flashes forward to bright, new possible futures, it is the film we want and need.��� Is that what was so threatening, these new possible futures that the film hinted towards, the joy, the hope that the film ends with? Is that really what is at stake?

Wanuri Kahiu

Absolutely. He���s been very clear on saying that he didn���t want people to think that it is acceptable in Kenya for you to love another person of the same sex. He stated very clearly to me that the impression the film leaves is that it is acceptable and he doesn���t want to leave that impression. But he did not go on to define acceptable to whom or why. That���s the curiosity because populations are not made up by one person, or one ideology. He made it seem as if we are all meant to be this one thing, and this is obviously something I strongly disagree with. First, as a woman, and as someone who believes in equal rights for everybody. And the moment we have this ���single story,��� like Chimamanda [Adiche Ngozi] talks about, this idea of a single ideology, single identity, it���s not only concerning, it also cuts out a lot of people who don���t fit into the hetero-patriarchal standards.

Julie MacArthur

Thinking about this idea that it is radical to imagine different kinds of futures – this film is a contemporary love story, but you also made another brilliant, acclaimed film, Pumzi���a sci-fi, post-apocalyptic film. And yet, I think the connections are clear, about imagining different kinds of futures, and that in your work is always entangled with how we think about the present.

Wanuri Kahiu

One hundred percent. The work that I create does not have a stylistic thread necessarily in terms of genre or artistic approach. But there is a thread line in the idea that I am trying to create my own versions of utopia, whether it is in a thought, an attitude, a friendship, or love, or the idea of sacrifice���I feel like those moments of utopia or those moments of hope where we can see different versions of ourselves and different good in ourselves, especially for Africans, is what I work towards. It���s what I would love to leave as an idea of what we can be, what we can work to, and what we already are.

Julie MacArthur

I am currently re-reading Dreams in a Time of War by Ngugi wa Thiong���o, which he begins by calling up T.S. Eliot���s famous line that ���April was the cruelest month.��� Ngugi ends the memoir with a pact, made with his mother, to ���have dreams, even in a time of war.��� This seems to really resonate with these kinds of utopias that you are speaking of, imaginings that are even more crucial at times when they are under threat.

Wanuri Kahiu

Absolutely. Because if we don���t have something to hope for then how do we know what we are fighting for. Life cannot only be about the fight. Life is not only about the struggle. Life is about what happens next. And if we don���t show, as artists, the possibilities of what���s next, then how do we give people a guiding light to move towards.

Still from Rafiki.

Still from Rafiki.Julie MacArthur

In a recent talk, you said, ���We have to see ourselves as people of joy������and I loved the way you connected this to ideas of expression, and to beauty for its own sake, not always functionalist or in need of an anthropologist to explain it as in colonial discourses.

Wanuri Kahiu

For the longest time the African continent has been thought of as a serious continent, as a place where bad things happen to people. Whether it���s war or corruption or famine or disease, it happens to Africans in Africa. So there���s been an overwhelming sense of “over there,” a “them” versus an “us.” One of the things that has fostered that ideology is the images, stories, journalism, and sometimes the way art is framed coming out of the continent. There���s a friend of mine who says you don���t want to wake up in the morning and watch an African film. And what she meant was, African films have been known to be so devastating and so heartbreaking, you���re [watching them] almost as if it���s tax. And that phrase really stuck with me because it���s so curious that we���ve been linked to a continent of pain given if you look into our traditions, our art, our ways of expression���be it music, dance, whatever���there���s always been heavy notes of frivolity ��� And we know to be true that the imagination doesn���t have borders, so why do we try to impose these imaginative borders on Africa too? Why is it that we only consider some type of work important if it���s coming from Africa? And the rest is derivative because it doesn���t deal with serious issues. I think that that is really problematic because it keeps showing Africans as people who are hopeless, desperate, or lost. That is not any way I describe the people that I know. Nor does it describe the people my parents know, nor my grandparents know. Yes, there continue to be moments of hardship, but even within that there is joy. And I think the best example of that is Hajooj Kuka���s film Beats of the Antonov. It has this beautiful series in the documentary where the place that he is shooting [the Nuba Mountains in Sudan] was bombed and people would run away into cave holes or the bunkers that they built themselves to avoid the bombs. And they knew that the bombs were dropped in threes ��� boom, boom, boom ��� and as soon as the third one was dropped, there would be a moment, and then there would be laughter, an explosion of laughter, and teasing each other: ���oh, I saw the way you were running!��� ���you���re running like a goat!��� That is a natural way of dealing with life, it���s seeing the joy in it, and what we���re living for. And if we don���t make an effort to make sure that we continuously see what we���re living for, we���ll begin to believe the lie that has been fed to us, which is we are a desperate continent, or we���re a broken continent. And if it says that about Africa, what does it say about the rest of the world if we imagine that Africa was the cradle of humanity? Are we saying that genetically everybody is linked to a broken, sad beginning? I don���t believe that to be true either. We need to remember our roots and we need to remember our joy in the way that we depict ourselves. That, to me, has become my life���s mission. To make sure that everything that I do has hope and joy in it so that I can show that we are a people of hope and joy. Period.

Julie MacArthur

The kindredness with Hajooj Kuka���s film Beats of the Antonov fits perfectly within this conversation. I remember Hajooj, very openly at the world premiere of the film, saying ���I made this film to overthrow a government.��� And the audience laughed because the film didn���t necessarily feel that way. It felt so joyful. Why does joy seem to be so threatening to some political or moral orders?

Wanuri Kahiu

Absolutely. And I think you���re on to something – which is something I���ve begun to believe more and more���that joy is disruptive. I think joy is political. I think that if we see large numbers of Black people truly enjoying their lives, truly being happy with themselves, I feel like that is challenging to the status quo. Because I truly don���t believe that the world is rigged for people who are considered ���minorities��� to be joyful. So there is a disruption that joy brings. And also, if you look at the work that has been banned across the continent, it���s joyful work. It���s not the remorseful work that they���re saying “Umm, could you change it because there���s a little too much violence or too much hatred”���that���s not the work, unfortunately, that���s being banned. The work that breaks us, and puts us down, and demeans women, and is violent against women or violent against minorities, is not the work that is being banned. And to me that is one of the most problematic things. We���re saying because you are a minority, you have no right to joy, and the moment that we show or we push back and we say this is our joy, then that���s when we���re shut down, and that is ��� painful for me.

Julie MacArthur

That dovetails with a statement that Stella Nyanzi made just recently when being released from prison after 18 months for writing a poem deemed insulting to the president [of Uganda], that she said she would not ���be remorseful������her activism and artistic work has often been called a politics of refusal, engaging in a long tradition of ���radical rudeness��� as Sylvia Tamale and others like Carol Summers have detailed. Nyanzi recently published a book of poems clandestinely written while in prison ���No Roses From My Mouth��� in which she writes: ���I will write myself to freedom!��� And this idea of joy, of love, of sex, and of expression as key to exercising freedom is linked to the work you���re continuing to do, pushing forward this case as it moves into the appeals arena.

Wanuri Kahiu

Yeah, it���s necessary, and I���m the most reluctant activist because I believe that everything I say is in my films ��� What I believe about the world, what I believe about equality, is in my films. But, this time, I think, being pushed into this space, I just felt that I am not in the wrong. I don���t know how else to say it. I just felt truly like I voted for the [2010] Constitution. I remember fighting for the constitution and it was very active. Actually the first time I was in any activist space was when we were advocating for the constitution. I was part of a group mobilizing young women to push through this constitution. And it was very clear, unlike a lot of other African governments, that there was a clause for freedom of expression, which means something to me as an artist. So, when somebody says “No, you���re wrong,” when the constitution you voted for is actually quite clear in its message about the very work that you���re doing, then it���s problematic. It���s as if someone is treating you like you���re ignorant, like you���re not taking your work seriously. And I truly believe that my work is to create stories. And not everybody has to agree with the content of the stories and therefore not everybody even has to watch them, I���m not asking everybody to watch them. But I���m definitely fighting for the right for you to decide to watch them ��� I believe that whatever you believe, even though I don���t believe it, you have the right to say it, unless it is constrained by the very clear instructions that are already in the constitution [propaganda for war; incitement to violence; advocating hate], and none of the things that we���ve done are in conflict with the constitution as it stands. And that���s why I felt like it���s a necessity for me to fight for it because I don���t take for granted that I was alive enough to vote; I was alive enough to advocate; and I will be alive enough to fight for my children���s rights to live in a country where their constitution means something. It has to mean something.

Julie MacArthur

Artist and activist Ayodele Ganiu, currently a fellow at McGill University in Montreal, in December 2019 wrote a really timely piece, in which he argued that:

The popular saying in Nigeria that “the judiciary is the last hope of the common man,” including for an artist who uses creative expression to challenge the status quo, is fast becoming a fallacy in many African countries ��� To protect artistic freedom in Africa and empower artists to exercise their civic responsibilities … Without an independent judiciary, there will be no true art, and no rule of law.

Your film has now come at this nexus of law and art that maybe you didn���t plan for, or necessarily wanted to insert yourself into as an activist, but Ganiu certainly sees it as a civic duty to produce this kind of art.

Wanuri Kahiu

Yeah, and I think it���s my civic responsibility also to fight for it now. Because I didn���t think it was before, but I know for a fact that it is now because if I don���t do it, who am I asking to take up this fight, if I���m not the one doing it? It is difficult, I can���t say that it���s not. I think that it constantly reminds you that patriarchy is real. That it doesn���t matter what the law says. That sometimes people will walk over your rights. But as a result of this censorship, it has also made me investigate the other types of censorship that are not in public arenas, that are not in courts. That are in homes, and the way that we speak to people, and the way we ask them not to tell their stories or we ignore their plights or their existence. There are so many assaults on freedom of expression and freedom of speech in everyday ways and that have come to light. What kind of world are we creating when we actively stop people from speaking or from doing because of, say, economic censorship? No, you can���t tell that story because nobody will read it. No, you can���t make that film, because there is no viewership for it. That economic censorship continues to happen around the world, outside of Kenya. So even as we fight this fight in Kenya, I know there���s a much bigger hearts and minds fight just on the idea of the ability to speak your mind. But I am of the opinion that there is no human rights without freedom of expression and freedom of speech. Because without it, you wouldn���t be able to advocate for anything. Without freedom of expression and freedom of speech, there would be no women���s rights, there would be no LGBTIQ rights, there would be no disability rights, there would be no rights because you wouldn���t be able to express what is happening.

Julie MacArthur

Maybe ending on a more hopeful note, although banned in Kenya, the film is having a life and a journey, both regionally and in the world. Could you speak a little bit about the distribution and the platforms that the film is available through?

Wanuri Kahiu

Across the African continent, the film is available on DSTV, which is the African [satellite] station. So, everywhere across Africa the film is available except Kenya, which is extraordinary to me because there are much more conservative countries than ours. But what it has done for audiences is that it has added to the narrative of Black love, which, unfortunately, there are not enough love stories of people of color. And especially queer people of color. So, it has opened up spaces for people to feel seen, which is all a filmmaker can ever want. To be able to create a film where other people feel seen because they often didn���t belong. Growing up, I never saw people like me falling in love. So to add an experience where that happens is incredibly important for me, so that we know that we���re worthy of love.

August 11, 2020

On Safari

We've always wanted to post these images from a 2006 advertising campaign by Rocawear, Jay Z's clothing company. We hope they have a sense of humor and don't ask us to take it down. It's just for illustration.

On August 16, 2012, South African police shot and killed 34 miners at a platinum mine in South Africa���s Northwest province. The workers had been on strike to demand better pay and an improvement in their working conditions. The mine belonged to a British multinational firm. One of the board members was Cyril Ramaphosa, now South Africa���s President. At the time, it was Ramaphosa who advised the directors of the company to call in the police. Two weeks later, the government appointed a public commission; a favorite South African pastime that outlived colonialism and apartheid and which usually results in no one being held accountable, the problem resolved, or any redress paid to the victims. The Marikana Commission of Inquiry was no exception.

In any case, as AIAC editorial board member, Dan Magaziner, and I wrote at the end of August 2012, the Marikana mine killings in August 2012 showed that South Africa was no longer exceptional: That its problems are no longer specific to the apartheid legacy, but about more global issues of poverty and inequality. We wrote this because in the mainstream media Marikana was framed mostly as disappointment with the new South Africa and its leaders, but as Dan and I concluded: ���Rather than judge South Africa in the wake of this 21st century Sharpeville [with reference to another episode under apartheid where the police shot 21 black people protesting the pass system], the rest of the world ought to ask what kind of community post-apartheid South Africa has joined.���

This is also where we think we are now. In fact, we have been thinking that for a while. That, while it easy to focus on the failures of post-independence Africa (and there���s a lot there), we feel that, going forward, it is more useful to ask what world we joined and what can we do to change that world. And what conversations can we have with fellows in Asia and Africa or with the movements of marginalized people in the global North (and places like Australia and Japan) to arrive at new ideas and new tactics to deal with old and new problems: class inequalities, racism, climate crisis, political representation, authoritarianism, erosion of work, and migration and borders, among others. Luckily, we have a break now to sharpen our tools to take on this task with new energy. Till right after August 28th.

That means we won���t be publishing any new material on our website, produce our livestream show, or videos on our Instagram channel. Of course, we will tweet occasionally and post on our Facebook page, and you can always catch up on the archive.

August 7, 2020

African literature is a country

Image credit Suad Kamardeen via Unsplash.

We would like to thank Henry Vehslage for his assistance in organizing and gathering all the information and Dr. Erin Butler for help in interpreting the data. An additional heartfelt thanks to the late Professor Tejumola Olaniyan for his support and advice on this project.

African literary studies today is a site of deep paradox. On one hand, the last two decades have seen astonishing growth for African literature in the global North and South, evidenced by lucrative publishing deals; new prizes and grants; literature festivals; the establishment of many new presses and imprints; and an increase in blogs and platforms that disseminate and discuss these developments. On the other hand, African literature continues to exist on the margins of the academic mainstream and is also underrepresented within larger reading publics.

For example, Achebe���s Things Fall Apart, was the only book included in a recent survey of the literary canon. African literatures are usually classified and taught within a continental framework���as in the category of ���African literature������a geographical term that implicitly disregards the myriad regional, national, cultural, and economic differences in a continent comprised of fifty-four countries. Indeed the colonial invention of a composite and singular ���Africa��� remains as entrenched in academic institutions as it is in the global imaginary. That���s how we came to survey instructors of African literature at the university level to find out which works and writers are most regularly taught in their courses.

We sent out emails to over 250 academics, a majority of whom were listed as members of the African Literature Association in addition to several others drawn from our own professional networks. One-hundred and five individuals replied, mainly residents in the US or Europe, and a number of Africa-based professors also contributed to the study. Here���s what we found.

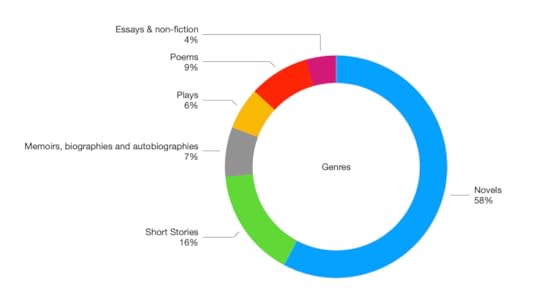

Of the 671 texts that were listed by our respondents, the majority were novels (369) and short stories (101), while memoirs, biographies and autobiographies (46), poems (56), plays (39), essays and non fiction books (28) and anthologies (32) made up the balance.

The majority of authors (407) were men (251), followed by women (155). One author identified as non-binary.�� As for country representation, 45 of the 54 countries that make up the African continent made the cut: South Africa dominated with 106 authors on the list, followed by Nigeria (62) and Kenya (30). Countries with 10 or more books on the list were Senegal (18), Egypt and Zimbabwe (16), Uganda and Cameroon (15), Morocco (11) and Algeria (10). And the total number of languages of assigned texts was 18.

What does all this mean?

Though it was expected that Nigerian and South African texts would dominate the field, we did not anticipate how extreme this would be. Most countries on the continent are represented on curricula by less than five individual texts, whereas 62 Nigerian literary works and a whopping 106 South African are regularly taught.

When it comes to languages, English and French are the source languages of the majority of texts, though a smattering of African languages taught in translation are represented by Acoli, Afrikaans, Arabic, Tigrinya, Xhosa, and Yoruba literary works. A fair number of works written in Spanish and Portuguese are also regularly taught.

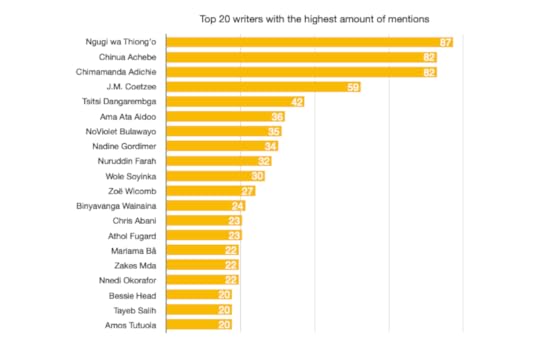

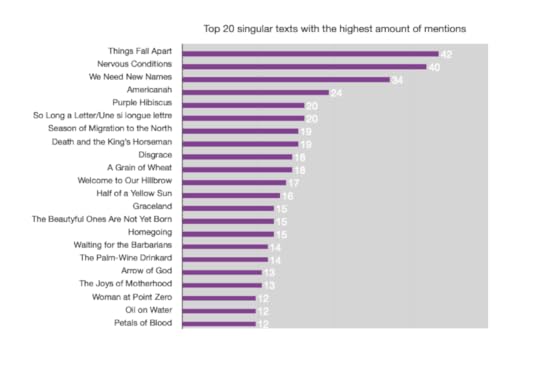

Among authors, Ng��g�� wa Thiong���o is the most taught writer (87 mentions). Nigerians, Chinua Achebe and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, are similarly popular on syllabi (82 mentions each) while J.M. Coetzee is the next most taught author (59 mentions). Achebe���s novel Things Fall Apart is predictably the most frequently assigned novel, followed by Tsitsi Dangarembga���s Nervous Conditions and NoViolet Bulawayo���s We Need New Names (assigned 42, 40, and 34 times, respectively). That two works by Zimbabwean women rank among the top three most regularly taught novels on college syllabi is an encouraging indication of certain changes afoot. Zimbabwe is thus one of the countries best represented on African literature syllabi. Yet this also reminds us how singular works are often instrumentalized to represent not only an author���s entire body of work, but often her country, and even her continent.

Senegalese writer Boris Boubacar Diop told us that its always the same old texts as well: ���African authors are taught in both [Nigeria and Senegal] however they are almost the same ones since the time of independence: Senghor, Beti, Sembene, Kourouma etc. for the ”francophones” et Ng��g��, Achebe for the Anglophones. Quite often, one explores the text more often than the novelistic universe; A Grain of Wheat or Things Fall Apart, God���s Bits of Wood, Suns of Independence���Sometimes it feels like students can recite entire passages from these books but also that they only know these.”

Unfortunately, it���s true that only a few canonical works dominate the field, coupled with the near or total non-representation of many important literary traditions including Namibia and Madagascar, to name two countries with rich literary histories that no one mentioned in our survey.

However, this is not a crisis without the potential for transformation. While literary works from South Africa and Nigeria often serve to include African literature in pedagogical efforts to diversify syllabi and include the continent, scholars and teachers of African literature also teach a dizzying number of other works alongside the predictable ones.

Institutional issues

With contemporary debates about decolonizing academic curricula raging in the global North, we wanted to find out where the teaching of African literature is itself positioned within these discussions. The analysis and criticism that follows is therefore primarily directed towards European and North American institutions.

African literary studies often produces institutional quarrels at departmental levels since it is taught within constrained spaces. Most regularly taught in English and Comparative Literature departments, African literature has also historically found a tenuous home in area studies units. Comprising widely diverging percentages of curricula, it is nonetheless fair to say that, in general, African literature constitutes a very small part of what students are offered in most Euro-American literature departments, and is rarely, if ever, required.

In contrast, European and American literature is often sub-specialized into regions, historical periods and single author courses. Undergraduates can enroll in Medieval English Literature, Renaissance Literature, Romantic Poetry, Early American Literature, Shakespeare, Beowulf and so on. Courses dedicated to Nigerian or Kenyan Literature, or single-author courses on canonical figures like Achebe, Ng��g��, or Djebar, or period courses on precolonial literary Africa are rarely offered. And, of course, other equally important literary traditions (Asian-American, Caribbean, Australasian, African-American, etc.) are in similarly embattled positions within literature departments. In the US, African literature often gets swapped out for African-American works in the push for diversity despite their very different literary histories.

If Africanist scholars were permitted more leeway and given more curricular space, students��� exposure to works from the continent could deepen and increase exponentially. Furthermore, giving students access to this wider range of faculty expertise would disrupt the overreliance on a handful of representative canonical writers who are themselves often opposed to having their work deployed in this way.

African Literature in Africa

Undoubtedly, African literature is taught in widely divergent ways from department to department and from country to country. Though the structures of teaching African literature within African universities are less familiar to us, based on conversations we have had with scholars currently teaching or trained on the continent, the ideological underpinnings of curricula in Africa tend to fall loosely into either a traditional or decolonial model.

At the University of Nairobi and at Makerere University in Kampala, students gain a deep knowledge of African literary traditions with emphasis placed on orature and orality. This, we surmise, is due in part to Ng��g�� wa Thiong’o, Henry Owuor-Anyumba and Taban lo Liyong���s efforts in 1968 to decolonize the curriculum, famously described in the subversive memo, ���On the Abolition of the English Department.��� Though a core text of decolonial theory, so few institutions have put its ideas into practice in the 50 years since it was conceived. Other sites where decolonizing curriculum is at the forefront of campus debates, can be found in certain South African universities: at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg which offers both a BA and MA in African Literature; at the University of Cape Town; and at Stellenbosch University.

In contrast, the second, traditional approach to teaching African literature on the continent describes the vast majority of departments that continue to prioritize Western canonical works over African ones. This Bloomian vestige of colonialism places British or French literature at the heart of literature curricula. Most universities in Cameroon, for example, and several institutions in North Africa are rigorously European in their curricula with very little focus on African or postcolonial writing. It also appears that though there are some attempts to broaden literature curricula in Nigerian universities, quite a few of our Nigerian colleagues, who form a large contingent at the African Literature Association, mention the difficulties in pushing these agendas through the system and in getting Nigerian university departments to embrace decolonized literary models.

Of course, our binary model insufficiently describes the institutional and regional variety of approaches to teaching African literature in Africa. We are aware it also does not adequately represent the curricula in local languages such as Arabic in Egypt, or Swahili in Tanzania.

Going forward

Regardless of the very clear sense that there is much institutional work to be done, the sheer number of discrete literary texts being assigned illustrates the vitality and diversity of the field, and also attests to teachers��� pedagogical commitment to refuse curricula that homogenize the continent. It is heartening to note that this survey���s results suggest that instructors are solidly committed to experimenting with decentered, non-canonical, and potentially decolonial frameworks by assigning texts that cover a wide range of histories, genres, and literary traditions.

This survey is a first step in assessing the teaching of African literature in a multitude of departments. We recognize the vastness of our field and the inherent limitations in our research methods. But this survey and our early observations are first and foremost, a provocation.

These days, the push to ���decolonize the curriculum��� dangerously approaches a facile tokenism we wish to resist. So-called classics continue to get prioritized but with some commentary on racism or sexism folded in. Syllabi get sprinkled with black or brown writers, women writers, and gay writers. But these gestures are nothing more than a cursory nod to diversity. This diluted approach towards decolonizing our curricula that dominates many Western universities has to stop. It is high time that institutions of higher education carved out more space and funding for the study of marginalized literatures, and reckoned with the deeply embedded epistemological biases inherent in curricular design. Individual departments must be willing to alter their definition of diversity itself, to decolonize diversity, if we may. Giving students access to the massive existing body of African literature is just the beginning.

No one is coming to save us

Garment factory Harare, Zimbabwe. Image credit KB Mpofu for the International Labor Organization (ILO) via Flickr CC.

In 2012 former Botswana president, Festus Mogae, gave a talk in Ghana on ���African governance.��� During the question and answer, he was asked: when seeing what was happening in Zimbabwe, why did African leaders choose to remain silent? Why did leaders refuse to admonish a leadership that was killing its people? His response, in summary, was: Zimbabwe was like a relative that you know is making mistakes. You can tell them to change their ways in private, but you cannot force them to see reason. Almost ten years later, nothing has changed in Zimbabwe. And in the face of a global pandemic, the African Union���s silence is a death sentence.

Zimbabwe���s government went from openly mocking countries shutting down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, to begging the international community to fund its national response. Once funded, the health minister ignored healthcare workers��� demands for better personal protective equipment (PPE) and improved working conditions, while actively over-inflating the pandemic budget in order to plunder funds from the nation���s nearly 15 million people. State hospitals in the country���s capital are barely equipped to manage the pandemic; the rest of the country���s healthcare infrastructure is severely understaffed, under-equipped, and on the precipice of a public health disaster that will leave many exposed, if not dead. The state has decided it does not care whether Zimbabweans live or die. And it appears, neither do President Emmerson Mnangagwa���s relatives.

The government has arrested, abducted, and tortured citizens for speaking out against the administration���s failure. Journalist Hopewell Chin���ono was abducted, later confirmed as arrested, and is facing trial for ���incitement to participate in public violence.��� In reality, Chin���ono���s crime is exposing state corruption and looting of the country���s COVID-19 funds.�� Chin���ono demanded transparency, accountability, and encouraged citizens to engage in peaceful protest until the former two demands were met. The calls were made on Twitter, in a country with only 56.5% internet connectivity and likely very few Twitter users. If Twitter activism makes the government this uncomfortable, one can only imagine what else they are trying to hide. In particular, women face the brunt of the government���s draconian retaliation. Police violently beat women in Bulawayo for violating curfew. Police arrested activists calling for a stop to constitutional amendments that are being pushed through without sufficient citizen consultations. And most recently award-winning author Tsitsi Dangarembga and opposition party spokesperson Fadzayi Mahere were arrested along with many others for holding a peaceful, socially distanced demonstration again calling for an end to government violence and persecution.

A national 6 am to 6 pm curfew has been in place for several weeks, and police have been swift to enforce it, even chasing citizens out of the cities at dusk.�� The government banned independent public transportation in the wake of the pandemic, only permitting state-run buses to operate. The buses cannot ferry the volume of people who need transportation out of town, and they are certainly unable to do so while observing social distancing guidelines. Furthermore, the police and the army have become a staple in the Zimbabwean urban landscape. What is taking place in remote parts of the country where Twitter and the internet are not present?

President Mnangagwa���s relatives remain silent, as does the African Union. The silence is infuriating. It should be enough that Zimbabweans are dying. But they are dying at the hands of their ���liberators,��� the men���and women���who waste no time claiming that they fought for the country���s freedom, and only they have the right to determine the scope of that freedom. The Zimbabwe African National Union ��� Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF)���the ruling party since independence in 1980��� has robbed Zimbabwe���s real heroes of their legacy; they walked them into a bigger cage and said self-determination was the same as liberty. It is not and, now Zimbabweans are forced yet again to fight for their freedom.

Should we have seen the oppression coming? Yes. There were many red flags, the massacres of thousands of innocent people in Matabeleland in the 1980s, the violence that preceded the land reform program, the brutality that accompanied the 2008 elections. Only two years ago, the army shot citizens in broad daylight in the middle of the street, and no one has been held accountable! Each one of these incidents showed how little the country���s leadership valued Zimbabwean lives. They should have also been warning signs to an African Union that has ���committed to [an] integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens.���

The sad reality is that many of our presidents are also waging war on their people and tolerating the revival of a slave trade in Libya. With few exceptions, Africa���s patriarchs have proven to be interested in their priorities first, to the detriment of the continent���s peoples. Now, no one will save us but each other.�� We cannot look to parties like Zanu-PF because, in many ways, their work is done. They were necessary to achieve self-determination, but they have proved incapable of facilitating self-actualization. We need a new path, the people���s way. Zimbabweans, Cameroonians, and many others across Africa need a different union, one that is willing to defend and protect all of our rights. Our lives, our future, and that of any generation to come, depend on it. Zimbabweans need your solidarity at this moment to stand up to the system that has broken the country. May your willingness to stand with us signal the emergence of a more powerful people���s Afrikan Union, one that protects us all.

August 6, 2020

Fighting the pandemic in the global South

Garment factory in Bulawayo, Harare, Zimbabwe. Image credit KB Mpofu for the International Labor Organization (ILO) Flickr CC.

Global South countries now occupy six spots in the top ten of the world most affected countries by the coronavirus: namely Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, Chile, Peru, and India. And things are about to get worse.

It is just a matter of weeks before the whole of the global South is faced with the situation that confronted Italy and Spain in March 2020. Due to a history of colonialism, these experiences will play out differently in these countries especially economically and mortality wise.

The majority of the countries in the global South have limited testing capacity, and so the virus as predicted has been advancing undetected. The economic crisis ripple effect has hit us hard already, and we can no longer afford to enforce hard lockdowns in most of our countries. Most governments in the global South have been forced to ease lockdown restrictions, and are now witnessing a drastic rise in COVID-19 infections on top of testing lags. It becomes imperative to question what are these underlying economic factors that force us to do so and why should we save the economy over people’s lives? For instance, after the national lockdowns in South Africa, Bangladesh, and Mexico were significantly relaxed, all three nations reported their highest single-day spikes in COVID-19 cases.

Underdeveloped countries have no freedom of maneuver in relation to world capitalism as scholar Samir Amin notes: ���So long as the underdeveloped country continues to be integrated in the world market, it remains helpless ����� the possibilities of local accumulation are nil.���

In How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Guyanese historian and pan-Africanist Walter Rodney remarks that: ���Colonialism was not merely a system of exploitation, but one whose essential purpose was to repatriate the profits to the so-called mother country… It meant the development of Europe as part of the same dialectical process in which Africa was underdeveloped.���

Rodney embraced dependency theory���s central thought that colonialism condemned poor and colonized countries to stagnation, as he wrote: ���Whenever internal forces seemed to push in the direction of African industrialization, they were deliberately blocked by the colonial governments acting on behalf of the metropolitan industrialists.����� He believed that underdevelopment would continue even after African nations achieved their independence. Rodney, like other dependency theorists, called on intellectuals to break with capitalism and adopt state-directed socialist planned economies. Amin reasoned that imperialism led to the development /underdevelopment dichotomy, arguing that uneven development or historically evolved exploitative structures, leads to unequal exchange, which leads to continued polarization and increased inequality.

The World Health Organization said in April that there were fewer than 5,000 intensive care beds across 43 of Africa���s 55 countries. This amounts to about five beds per million people, compared with about 4,000 beds per million in Europe. It was not only the lack of intensive care beds that this pandemic has revealed as a shortage in Africa; there were at least 10 countries in the continent which did not have ventilators at all. Thanks to the ���generous��� donation from Chinese billionaire Jack Ma at least we now have 500 more. In South Asia, the situation is no better at all, as there is also a shortage of ventilators in countries like India which had 47,000 ventilators at the beginning of their lockdown.

The UK now has 22,000 ventilators, the vast majority of which are not currently needed as the peak has almost passed. In the global South again, the situation is dire as beds and ventilators are quickly running out. If international solidarity was taken seriously, it only makes logical sense that these resources would be diverted to countries that currently need them the most. However, under a capitalist society there are no free favors.

So far, Johns Hopkins University has detailed that in over 118 low- and middle-income nations, the increase in child and maternal death will be devasting.�� Based on a number of possible scenarios carried out by researchers, the least severe scenario over the next six months would result in 2,300,000 additional child deaths and 133,000 additional maternal deaths in this first year of the pandemic as a result of unavoidable shocks, health system collapse in various countries , or intentional choices made in responding to the pandemic.

An HIV modelling report, convened by the WHO and UNAIDS, estimated the effect of potential disruptions to HIV prevention and treatment services in sub-Saharan Africa over one- and five-year periods. It found that a six-month long interruption of antiretroviral therapy (ART) supply would lead to excess deaths over a year which are more than the total current annual number of HIV deaths. In sub-Saharan Africa, this amounts to possibly over additional 500,000 HIV-related deaths. Similar disruptions would also lead to a doubling in the number of children born with HIV.

It is evident that this pandemic has exposed the fragility of the capitalist system and has left many people questioning its importance as a means of production in our lives. However this is not new and has always been the inherent contradiction of capitalism that should it get disturbed, it plunges into turmoil. However, due to the weakness of the left it always finds ways to reinvent and reform itself.

As soon as capitalists��� institutions started to crumble, Northern governments resorted to socialist policies. The Spanish government, one of the worst affected countries after China, nationalized all private hospitals and healthcare providers to fight against the virus. In doing so the Spanish government had reversed their much unpopular post-2008 privatization reforms. Not only did Spain nationalize healthcare but they also announced generous financial aid packages for its citizens, stopped evictions and guaranteed water, electricity, and internet to vulnerable households. Such heightened state spending was also witnessed elsewhere in Europe, with the United Kingdom introducing a ��166 billion stimulus package since the beginning of lockdown: the largest in the country���s history.

By contrast, in the global South where the purse strings are tight, stimulus packages came in the form of loans from the IMF and World Bank as per usual. The IMF announced in April that it ���stands ready��� to use its $1 trillion lending capacity to help countries that are struggling with the economic impact of the coronavirus. If Thomas Sankara, the former Burkina Faso President who was overthrown by the agents of the West, was alive today, he would dismiss this so-called assistance from the IMF as nothing but wolves dressed in sheep skin.

Fanon once remarked that, ���the biggest threat to Africa’s development is not colonialism, but the big appetites of the bourgeoisie and their lack of ideology.��� It is the ���comprador bourgeoise��� according to law professor Tshepo Madlingozi that ���steal public money to buy garish belts, stupid pointy shoes, testicle crushing jeans, shirts with silly emblems, gas guzzling cars, alcohol beverages whose names they can���t even pronounce.��� In South Africa, they already have plundered the COVID-19 relief funds borrowed from the IMF and wasted it among their comrades while they confine us, the poor and the working class, to our shacks and backrooms in the townships.

In Zimbabwe, Minister of Health Obadiah Moyo was fired and arrested for misappropriating funds meant to be fighting the pandemic. He was arrested in mid-June and granted bail on allegations of corruption regarding a US$60-million deal to procure COVIP-19 test kits and medical equipment. (Then the government had the journalist, who broke the story, arrested.) Another Health Minister, this time in Kenya, Mutahi Kagwe, was caught submitting a highly inflated report on some of the products needed for the fight against the pandemic.

It is clear that in the global South the COVID-19 pandemic is set to wreak havoc, due to the unconfronted legacy of colonial underdevelopment which has been further aided by the collaboration between the metropolitan bourgeoisies and the comprador bourgeoises in our countries. The state of our healthcare systems is not equipped by far in comparison with Europe���s systems to deal with the incoming tornado, and neither are we economically stable enough to deal with the ripple effects. If we are to see the other side of the pandemic, we must emerge with a new imagination of how we are to strengthen and build strong working-class movements that will challenge imperialism because only then we can put an end to�� neocolonialism.

Herman Mashaba wants you to forget

Johannesburg CBD. Image credit

Babak Fakhamzadeh via Flickr CC.

Herman Mashaba doesn���t want you to remember. With an abrupt resignation from political office and from the right-wing Democratic Alliance (the official opposition party), the former mayor of Johannesburg, South Africa���s largest city, intends to rewrite his legacy and begin again. He wants to govern for a second time by launching a new political party. It’s not just that he’s attempting to re-enter South Africa���s political scene���Mashaba is reinventing himself without the wreckage he has left behind, the ruins that ruined him, if you will. And while his recent formation of the People���s Dialogue aims to speak to the issues directly negatively affecting ordinary South Africans under the ruling African National Congress (ANC), his political actions as mayor tell a different story.

During his tenure, Mashaba unleashed violent impunity through raids and evictions, particularly in Johannesburg���s inner city. He reinforced xenophobia and deepened inequality while creating a fabled narrative as a unifier with business acumen. And while he didn’t create the inequalities that exist, he hollowed out the laws designed to protect the city���s most vulnerable.

When Mashaba became mayor in 2016, his entry into the political scene seemed foreboding. Unmistakably brash, he immediately vowed to ���clean-up��� the inner city and promised pro-poor policies. Yet early on in his tenure, market-friendly urban development strategies were sidelined for harsher tactics. Police raids, building expropriations, and water tariff proposals shifted seemingly commonplace urban development schemes in the inner city towards more disruptive and brutal methods. Among politicians, some things remain constant: superficial optics and messaging. As mayor, his project ���Buya Mthetho��� or ���Bring Back the Law��� would do the work of meaningful social policy. In inner-city Johannesburg, an area at the crossroads of decay and feverish development, he bludgeoned his vision forward.

Immediately his incendiary remarks about migrants and public condemnation of human rights lawyers tempered expectations about the ambitions of the city���s entrepreneurial mayor. In retrospect, we could concentrate on his inflammatory statements and how he danced between self-importance and crime fighter ideas, but his louder tendencies should not draw attention away from his shrewder actions, particularly in his last year of office.

That period offers a notable, yet understated example. On June 28, 2019, the city of Johannesburg agreed to place residents of the Ingelosi House, in Hillbrow, in emergency housing after their eviction. In 2019, nearly 90 individuals waited for Temporary Emergency Accommodation (TEA) after receiving an eviction notice almost five years earlier. Ingelosi House was considered a “hijacked” building, meaning its residents became illegal occupants despite paying rent and living in the building for several years. As a result, it was targeted by the mayor’s building expropriation plans. In the inner city, when new owners purchase property (often claimed by the city for unpaid debts), old tenants without any legally binding agreement can be forcibly removed. Still, the municipal government must ensure that evicted parties are not made homeless due to their removal.

His administration���s ability to delay the transfer of tenants while ultimately questioning their eligibility for emergency housing reflected a more significant issue. It demonstrated a weakening of constitutional housing rights, but it also belied his sympathies to the “forgotten people”, the ordinary South Africans he long claimed to represent.

Under Mashaba, postponements, obstruction, and lax enforcement abated housing laws. The court documents in Hawerd Nleya and Others v Ingelosi House (Pty) Ltd (���Ingelosi House���) are revealing���here, the city of Johannesburg was taken to court to enforce the order directing them to provide the residents of Ingelosi house with alternative accommodation. Statements by the city suggested that evictees in ���dire��� need must substantiate how desperate their housing needs are to access TEA. City administrators declared that, “There is an onus upon the occupiers to make out a case that they indeed are in dire need and they will be rendered homeless if evicted.” They also argued that, ���The occupiers, inter alia, [are] required to provide evidence under oath and documentary evidence.���

Evictions are grinding, from the time one receives a notice for eviction, to the removal by the ���Red Ants��� (a private security company specializing in evictions and demolitions), or the police. After displacement or dispossession, the ongoing search for shelter makes the process an unceasing torment. For some, it is a return to the places whence they came or to a new home���and often, ones bearing the same conditions deemed necessary for eviction in the first place. His administration argued that residents of a hijacked residence needed to supply qualifying income criteria to be eligible for TEA.

Instead, what poor people in inner-city Johannesburg desperately needed never formalized, nor did any plan to cut deep into the deteriorating conditions in the area and the deepening housing crisis in the city. Yet, as people awaited Mashaba’s plans to “transform the inner city,” his pro-poor mandate became an empty signifier. He will not reinvent his leadership. This is how Mashaba will govern.

When considering Herman Mashaba���s new political plans, the public must reckon with the mayor���s actual record. Under Mashaba, the city of Johannesburg raided the poor, spread xenophobic messages about migrants, and violated constitutional rights to housing and against forced removals. The politics of forgetting used by the Mashaba campaign informs how we should read his politics. Attempts to remove crime and corruption are commendable, but Mashaba���s time in Johannesburg reminds us that as a politician, he will starve the beast to eat the villagers.

Ernest Wamba dia Wamba, a healer from within

The Congo River at sunset, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Image credit Marie Frechon for UN Photo.

In the early hours of July 15, 2020, at the University Hospital in Kinshasa, a brother, comrade, philosopher, historian, thinker, healer, and dreamer left us physically. But like a star in the firmament, he is still there to help us navigate through the current and future times, assuming we understand what he had been trying to accomplish in his life, and how he understood the senselessness of the managers of a dominant system that presumes it must control and own everything.

From wherever he is, Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba would have welcomed the launching of SENS, on August 3, 2020, in Burkina Faso, a movement aimed at ���servir et non se servir,��� which translates as ���to serve and not to help oneself.��� This is counter to the practice of so-called leaders in many African countries, where the state has become the trough. Is it possible to put an end to these kinds of situations? That is one of the questions that dominated Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba���s life.

In his approach to the most urgent problems, Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba always thought and acted as if he were everywhere, seeing things from all possible sides, while being grounded within his native culture of Congo. He knew how to listen with intensity.

In July 2019, he had to go to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to renew his passport, letting it be known that he would be back home, in Dar es Salaam, within a month or so. In hindsight, it is not difficult for anyone who has known him to understand that being close to where he was born, and where he grew up, he would take the opportunity to re-visit his birth place, Sundi-Lutete. The political and economic conditions in the DRC are well known even to people outside of the country. It is one of the richest countries on the planet in terms of natural and human resources. Yet, it is also one of the countries with so-called leaders whose single-minded self-interest has been to accumulate wealth, ensuring that the majority of the population remains poor.

Paying tribute to a person from whom one has learned more than one will ever be able to articulate is challenging.�� I first heard of Ernest Wamba dia Wamba, in the summer of 1974, through a common friend, when I had just finished my Ph.D. and was on my way to my first job, in Los Angeles.�� A few years later, in Mozambique, after four years teaching at the University of Dar es Salaam, I heard from him by way of a critique of a two-part article I had written with Henry Bernstein. He sent me his criticism and I responded to it, mostly agreeing with him.

From then onward, we kept corresponding until we met, face to face, in 1983 when I was invited to be an external examiner for one of the departments at the University of Dar es Salaam. In a world that is dominated by practices of categorization, splitting, and tribalizing, it is impossible to decide where to locate Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba. For some he is a philosopher; others look at him as a political scientist. Marxists and non-Marxists appropriated him.

For many others, the majority, he is seen as a decent human being, someone who could befriend anybody. This kind of ability is rare, especially among those who have achieved a certain level of recognition, through their intellectual and/or scientific trajectory. Speaking of recognition, he was awarded the Prince Claus (from Holland) prize for Culture and Development, in 1997. For his contributions to CODESRIA, he was elected President for the 1992-1995 term. Still, he did not feel superior to others.

For Professor Wamba dia Wamba, the idea that everyone thinks also means that anyone can learn from anyone. In practice, this principle should mean that the hierarchization of knowledge is an anathema. It should mean that a university professor is not necessarily the one who knows best. A university professor must understand that he/she may learn from anybody, regardless of the context and circumstances. Professor Wamba dia Wamba never ceased to remind interlocutors that while history may be written by historians, history will only be changed by the masses.

From his own practices, he observed how individualism is reinforced by the hierarchization of knowledge, not only within the educational system, but also through the imposed culture of the dominant political and economic system.

The construction of a vocabulary, with words and concepts like competition and competitivity, has been one of the most powerful ways in which the culture of white supremacy imposed itself. As pointed out by Ayi Kwei Armah, Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, lamented in his autobiography, the fact that he grew up in a primitive society. When victims of white supremacy become the transmitters of self-destroying historical narratives, the consequences are incalculable.

Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba���s mindset was always rooted in his native culture, which he treated as equal to any other, a constant source of knowledge, wisdom, and inspiration, transmitted through collective and individual processes. In confronting a colonizing culture, the colonized mind must understand itself as equal, if not superior.

It is easy to marvel at Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba���s brilliance as a thinker, who was far ahead of his time; it is more difficult to grasp how he managed to maintain such a vision without being distracted by secondary issues. Although his admiration for Lumumba was unwavering, he nevertheless pointed out that Lumumba himself, hard as he tried, was not able to resolve, in his words, the equation he had faced, as Prime Minister: to transform the colonial state from an instrument of destruction into one that served the interests of all people, especially the ones who have been most exploited.

In his constant search for transforming the country into one that would serve and defend the interests of the people, in the same manner as, for example, Simon Kimbangu did in mobilizing workers and peasants back in the 1920s, Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba took the kind of risks that most academics instinctively avoid. As a result, he landed in one of the most notorious underground prisons of Mobutu from 1980-1982. At the time, the fight to save him from a worse fate pitted two sides: one that argued for doing things quietly and the other that insisted on making as much noise as possible. The latter side won. Mwalimu Nyerere (who knew Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba personally) asked President Mobutu why he was keeping one of his professors in jail. Soon after, Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba was released and eventually returned to Tanzania to continue teaching history at the University of Dar es Salaam.

When confronted with situations he was unprepared to deal with, as was the case, for example, of the 1998 rebellion against Laurent D��sir�� Kabila, he managed to re-orient it in such a way that it would operate for the benefit of all, not just for a group interested in seizing power by military means. For the Congolese Rally for Democracy, to which he was elected, the objective was transformed into getting all Congolese to come together and work towards building a nation that would benefit everyone, and not just an instrument for so-called leaders to enrich themselves.�� Among the consequences, the movement split into two and then three, reproducing the conditions for the perpetuation of the coup d�����tat as the way to secure state power.�� But following the assassination of Laurent Desire Kabila in January 2001, all parties involved in the war, including the government, agreed to meet in Lusaka to discuss how to organize an inclusive Inter Congolese Dialogue under the neutral facilitation of Sir Ketumile Masire, former president of Botswana.

Even if the Inter Congolese Dialogue, which took place in Sun City, South Africa in 2002, did not end once and for all the wars (at that time 11 of them) that had plagued the country since independence, it demonstrated that peace could exist in the DRC and also between the DRC and its neighboring countries.

It does not matter which part of Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba���s life one looks at, any observer will be struck by the same characteristics or qualities: adherence to an ethics of truth, fidelity to solidarity with those who are the wretched of the earth, regardless of the changing circumstances. These are the characteristics he grew up with long before he was attracted to Western philosophers like Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Alain Badiou, to name a few.

Following the rebellion, members of the Bakongo community accused him of being responsible for the death of innocent people, especially among, but not only, Bakongo people. He went through a ceremony of self-criticism and asking for forgiveness.�� Written and oral evidence confirm.

The reason for remembering this singular behavior is connected to what Alain Badiou described as fidelity to the event.�� The event in the case of Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba can be directly linked to the emancipatory politics of people like Kimpa Vita, burned at the stake on July 2, 1706 for standing up against the King of Congo���s involvement in slavery, and to Simon Kimbangu���s call, in the 1920s, long before the emergence of Patrice Emery Lumumba���s Mouvement National Congolais.

To capture the life of Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba is the kind of task that will require a major collective effort by the many he touched, inspired, and encouraged to join him in the project toward emancipation and healing from the most destructive system ever invented by humans���capitalism.

He is no longer with us to help make the corrections he would notice ahead of us; but, by learning from the lessons he has left us, in his published and unpublished writings, we should be able to carry on practicing.

Long after most people his age opted for retirement, Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba knew that retirement could not be an option because the DRC was still operating in the same manner as under Mobutu. Emancipatory politics could not possibly be brought about through controlling a structure that had been mostly unchanged since colonial times. He considered that his most important prescription was to keep pushing for changes for the better for the majority of the Congolese people.

Professor Ernest Wamba dia Wamba���s study of the palaver as a democratic practice for resolving contradictions had nothing to do with ���nativism���, but rather with his understanding of the fact that democratic practices did exist in Africa, long before they are said to have started in ancient Greece.

In the same manner, philosophy in Africa was indeed philosophy, not ���ethnophilosophy���, or a sort of sub-altern branch of philosophy for ���primitive��� people.

In his mind, philosophers like Spinoza, Leibniz Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Alain Badiou resonated like modes of thinking he had already heard as he was growing up understanding Congo culture as a source of knowledge equal to any other culture.�� In his exchanges with Alain Badiou, Wamba dia Wamba understood himself as a peer working toward achieving the same objectives of complete and total emancipation for all human beings.

In 2012, he joined the collective Shmsw Bak, organized by Ayi Kwei Armah to translate ancient Egyptian texts, and make them accessible to African readers who were not conversant in colonial idioms. Professor Wamba dia Wamba provided the Kikongo line-by-line translation for each of the four texts that have been published: SaNhat, Smi n Skty pn, SKHKHT EA, and Pthh-hhtp, into: SANHAT, An Official of Ancient Kemet, The Story of This Peasant, On Love Sublime, The Instructions of Ptahotep. All of these texts are available from PER ANKH, the African cooperative publisher in Popenguine, Senegal.

As far as he was concerned, a human being could not claim to be a human being if she/he was not a spiritual person. Spirituality is not equivalent to religiosity and/or ideology: from his practice, humans who are single-mindedly focused on acquisition of material goods are bound to annihilate, within themselves, the will or possibility of healing from the cumulative destruction of genocide, industrialized enslavement, colonization, apartheid, and neo-liberalism. This is one of the reasons why he became interested in the work initiated by Ne Muanda Nsemi, the spiritual leader who launched Bundu dia Kongo.

If we, his friends, sisters, brothers, and comrades, understand him and accept the challenge he left us, then we shall be able to live up to the heartfelt condolences we have expressed to the family, and, engage without delay toward carrying on the prescription he assigned to himself: bring about total emancipation of all humans.

Given the levels of destruction inflicted on the collective human consciousness, the task at hand may seem daunting and impossible. In this case, we shall remember him telling us, facing an apparently impossible task, that ���to the impossible we must be held to account.���

Dear Ernest, on your way to eternal peace, your heart is weighed against the feather that measures all of the good actions and thoughts of your life. The certainty that you are being warmly welcomed by the ancestors and by your two late sons, Remy Datave Wamba and Philippe Wamba, is small consolation to those you left abruptly: Elaine Wamba, your life companion; your sons Kolo Diakiese Wamba, James-Paul Wamba, and your daughter Cornelia Elaine Brown Wamba; your siblings C��line Kidunga, Martine Luviluka Wamba, Anne-Marie Lukondo Wamba, Julienne Luzolo lua Wamba, and Andr�� Mambueni Wamba.�� To all of them and members of the extended family, we express our most heartfelt condolences. Nenda salaama Ernest.

August 5, 2020

Ghana���s retrogressive Public Universities Bill

The University of Ghana. Image credit Michael Pollak via Flickr CC.

This post updates ideas first raised in posts first published on the Africa at LSE and CIHA blogs.

In 1988, the renowned Ghanaian historian Albert Adu Boahen gave the J.B. Danquah Memorial Lectures, named for an important figure in Ghana���s anticolonial struggle and an opposition figure after independence:

It is my firm belief that no appropriate and effective development of any country can take place, nor can any government be properly kept on its toes or made aware of what is really going on, until and unless there is free flow of information of all sorts, free and public discussion of national issues, and free and frank exchange of views at all levels of society; in other words, unless this culture of silence is broken.

At the time, Ghana was a military dictatorship.�� We wonder what Adu Boahen would make of the current attempts by the elected government of Ghana to control the country���s public universities through a proposed new law.

The Public University Bill (PUB) attempts a work-around of the provisions in the constitution that bars the President from serving as chancellor of a university or appointing officers to institutions of higher education, research or professional training. The PUB seeks to effectively make the President the head of all public universities by having him or her name the chancellor, nominate the chairperson of the University Council, and appoint the majority of Council members. In addition, the bill allows the President to dissolve the Council ���in a case of emergency.����� This could result in the top administration of universities being suspended during a change-over of government, as happens already in many public institutions in the country. Moreover, a sitting President might conceivably manufacture such a crisis for an immediate political end.

Even more inexplicably, Clause 47 of the bill states, ���The Minister [of Education] may give directives on matters of policy through the Ghana Tertiary Education Commission to a public university and the public university shall comply��� (emphasis ours). These directives cover a range of activities from research collaborations to the establishment of new academic programs. This clause, together with others, diminish the autonomy and capacity of public universities to respond to changing research priorities, funding opportunities, and student and faculty needs in dynamic national and global contexts.

The government���s justifications of this executive take-over of universities are far from convincing. The claim that universities are too diverse and that many have ���veered from their core disciplines��� does not acknowledge that all changes to university curricula, administration, and governance are done within existing laws and are overseen by regulatory institutions such as the National Council for Tertiary Education. The government���s second rationale is that universities have evidenced financial improprieties and must, therefore, be better regulated. The idea that public universities would fare better under the direct control of ministries and politicians who are regularly embroiled in corruption scandals is almost farcical. This claim also ignores the existence of the many laws and institutions whose job it is to address instances of financial malpractice in public institutions.

The bill comes as the global coronavirus pandemic has compelled universities around the world to re-examine current forms of teaching and learning and, importantly, to envision a future for higher education that is more equal, more effective, and less pervious to shocks. By contrast, the PUB, if passed into law, would set higher education back several decades. It has compelled Ghanaian academics to move to defend basic academic freedoms that we have long taken for granted.

The 1992 Constitution of the Fourth Republic of Ghana (which ushered in the reintroduction of democracy in 1993), in many ways reflects lessons learnt from the attempts of autocratic and military regimes in Ghana to impose political control on civil society, including academia. One of the worst episodes was in 1978 when university students, medical doctors, lawyers, and other professional groups expressed their disaffection with Ghana���s military dictatorship, the Supreme Military Council, through a series of general strikes. The regime responded with harassment and intimidation; for example, doctors, many from the University of Ghana���s medical school, were chased out of their official residences by weapon-wielding government-sponsored vigilantes. University students in Ghana, as is true in many other African countries, have historically been a political force and have, consequently, been the target of government aggression; on occasion, police have been sent onto university campuses to quell student protests, including recently in 2018.

The 1992 constitution���the third reiteration since Ghana became independent from British colonial rule in 1957���acknowledges this history with an explicit recognition of ���academic freedom���, among other fundamental rights, placing Ghana in a minority of 14 countries on the continent with such a provision..

Why, then, has a democratically-elected government persisted in pushing a bill that has been harshly criticized by many in Ghana, including the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences, as ���dangerous���, ���retrogressive���, and ���totally unnecessary”?