Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 163

July 28, 2020

Goodbye Annar Cassam

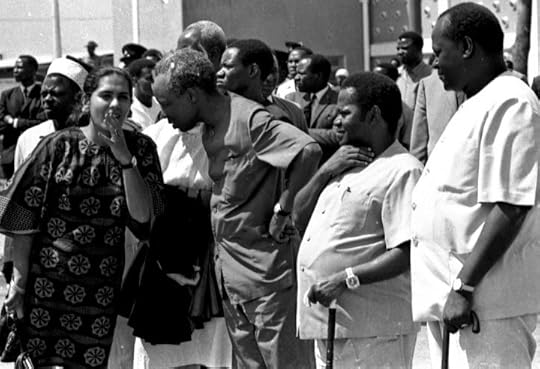

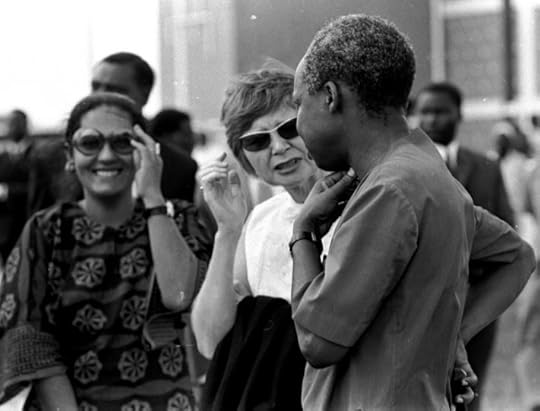

Cassam and Nyerere.

It has been a tragic year. We have lost so many people. A month ago,��Annar Cassam��also left us. She passed away in relative obscurity far away from her home country of Tanzania. Adarsh Nayar,��the personal photographer of the first president of Tanzania, was the first one to break the sad news on social media. ���REGRET informing my friends and colleagues Mwalimu Nyerere���s personal assistant Annar Cassam,�����he posted on Facebook, ���seen here speaking with him, passed away at 05.00 am this morning in Geneva, Switzerland, after a long illness.��� In that photo (reproduced below with permission) one gets a glimpse of the extent in which she was not then obscured in the Tanzanian political scenery. ���Annar, who was in regular touch with me,��� Adarsh recalls, ���had moved to Geneva after Mwalimu���s retirement in October 1985 and worked for the United Nations.��� Yet so little is known, especially among my generation, about this daughter of Tanzania.

There are at least five reasons for this obscurity. First, the most widely known assistant of Mwalimu Nyerere is the late��Joan Wicken. Second, Annar was expected to keep a very low profile during her years in the state house. Third, some people tend to confuse her name with that of the relatively renowned��Al Noor Kassum. Fourth, our national historiography still suffers from what Mohamed Said, following Dossa Aziz, refers to as a position in which��Tanzania is a country without heroes and heroines. By this, they mean there has been a deliberate dearth of historical narratives of some of those who contributed dearly to the struggle for independence and nation building. In line with this, the fifth reason is that Annar did not write much about herself and, in a way, spent most of her time ensuring the legacy of Mwalimu lives on. Yet his legacy was also hers.

It was while she was a student at the London School of Economics (LSE), Annar told me, that she ���first saw and heard Mwalimu��� who ���used always to find time to meet us students during his frequent trips to London in the 60s.��� After specializing in international law, she��went on to Geneva on a fellowship at the International Commission of Jurists. While there, she met freedom fighters for the first time. They were from the South West Africa People���s Organisation (SWAPO). Consequently, her first treatise there was on the illegality in international law of the then apartheid South Africa���s occupation of South West Africa (as Namibia was then called). It is thus not surprising that she was asked to come back home to work at Foreign Affairs in the 1970s. At that time Dar es Salaam was the headquarters of the��African Liberation Committee (ALC)��and Tanzania was instrumental in��supporting Southern African Liberation Movements. Tanzania���s foreign policy prioritized this role as it was a cornerstone of Nyerere���s presidency. With her expertise, she ended up working closely with him at State House. One of her jobs as Mwalimu���s assistant, recalls Adarsh, was to help him with translations of all French correspondence, and also be with the President when he was meeting French speaking leaders. She therefore experienced, at close range, Nyerere���s role in Africa���s liberation.

Annar���s ardent concern for setting the record straight about that legacy is partly what led us to our e-meeting. It all started when Firoze Manji, then editor-in-chief of Pambazuka News and Pambazuka Press, invited me in late 2009 to be a guest editor for��a special issue of Pambazuka News��to commemorate Mwalimu Nyerere on the 10th anniversary of his death. He then e-introduced me to Annar who was eager to share some unpublished articles with us, and was also willing to write an article aptly entitled��Nyerere on Nyerere. That was the beginning of a decade long friendship in which I learned so much from her about Tanzania and Africa.

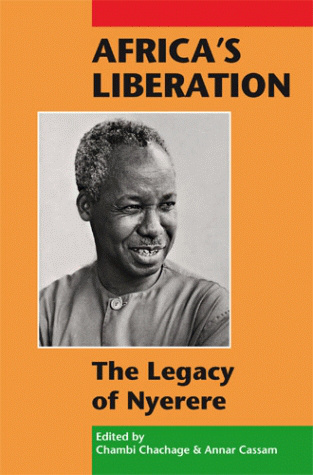

One of the outcomes of this was the publication of our co-edited book on��Africa���s Liberation: The Legacy of Nyerere. No one captures the process of publishing it as succinctly as her. ���Dear Chambi,��� she wrote, ���as your other half in this exercise, as your absent other half, to be precise, I can rely on you to transmit my heartfelt regrets for not being in Dar tonight to celebrate the launching of our book of tributes to Mwalimu on this day, April 13th, his birthday.��� So began a heartfelt letter that she asked me to read publicly��at Nkrumah Hall in 2010 during the book launch.�����As the editor of Pambazuka Press will tell you,��� her letter continued, ���this entire project started with my email to him of August 2009 to consider publishing a special issue of Pambazuka��News in October 2009 in order to remember and celebrate Mwalimu ten years after he left us.���

Until then I had no idea that she was the one who initiated it, itself a testament of how easily we can write out someone from history. After crediting the publishing team, she then wrote:

Through you, I would like to thank the Dar-based authors for their contributions which, by some strange alchemy, have come together to provide coherence and weight to this book despite the fact that it was compiled, edited and published across the oceans, between Dar, Geneva and Oxford. This is surely an example of minds meeting across distances!

To me this is important because the strength of the book derives from its duality. Annar brought into it the continental and diplomatic dimensions with chapters from Chief Emeka Anyaoku, Nawal El Saadawi, Firoze Manji, Ana Camacho, and Mohamed Sahnoun. I drew upon scholarly and national dimensions with contributions from Madaraka Nyerere, Neema Ndunguru, Seithy Chachage, Haroub Othman, Horace Campbell, Marjorie Mbilinyi, Faustin Kamuzora, Ng���wanza Kamata, Issa Shivji, Salma Maoulidi, Vicensia Shule, Helen Kijo-Bisimba, and Chris Maina Peter.

So often have I wondered why I didn���t know about Annar before. What excuse did I have as a scholar of Africa in general and Tanzania in particular? None. Her name appears in the archives that I accessed years later��during my PhD fieldwork. Karim Hirji���s��debate with��Annar��published on Udadisi blog��in 2011, for instance, also hints at her role in engaging with students at the University of Dar es Salaam during its heydays of revolutionary scholarship. ���My fellow editor of Cheche, Henry Mapolu, and I,��� Hirji recalls, ���had two meetings with Annar Cassam in those days.��� He notes that Annar ���came as a representative of Mwalimu (she was one of his assistants).���

Even after reading this tribute to Annar, you may still ask who was she? Why should we know more about her? All I can say is that it is because she was a living library and part of the institutional memory of our country. Take, for instance,��the article she wrote��about Kiswahili. ���During my career at the United Nations Organization for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO) in Paris,��� she notes therein, ���I had the opportunity to follow the literacy-language story from an international angle and so I offer these comments by way of history and context.��� After sharing how the success of Tanzania���s literacy programs for schoolchildren and adults during the Mwalimu years (mid 1960s-mid 1980s) aroused great interest and respect at UNESCO, both among the member states and within the Education Sector in the Secretariat, she commends our lingua franca:

It was obvious to literacy experts from around the world that the fact that these programs were carried out in Kiswahili was a major reason for the success. The advantage of teaching any subject, above all literacy and numeracy, in the language already spoken and understood by students and teachers was clear. This perception led to the design and promotion of mother-tongue methodologies as these provided the fast track to achieving literacy. Of course, in the case of Tanzania, Kiswahili was not strictly speaking the unique mother tongue, but it was as good as any because it was used in schools and was the national and official language of the country���s adults.

Cassam and Nyerere.

Cassam and Nyerere.Her passion was for us to write our own history. When I told Annar in 2015 that I was writing a chapter on��Mwalimu Nyerere as a Global Conscience, she generously offered to ship me her papers on the subject and related matters. Unfortunately, due to an unforeseen event, she wasn���t able to do so. She still managed to offer constructive comments and edits on my draft chapter, affirming that what I was ���recounting in this piece is pure factual history as it happened.��� In her public letter, referred to earlier, Annar also called for a publication that I am now told has been in the pipeline:

My gratitude goes to our brother Salim for honoring the occasion with his chairmanship, together with my ardent hope that he too will publish the record of his long years of close collaboration with Mwalimu.��Salim Ahmed Salim��was his trusted Prime Minister, Defense Minister, Foreign Minister, UN Permanent Representative and Ambassador���his first post was as Ambassador to Nasser���s Egypt at the age of 21. No one else holds such a lengthy and privileged place in the history of Nyerere���s Tanzania and we look forward to reading his account of this unique experience.

The same quest permeated her gratitude to another guest who graced our book launch. ���I am delighted���, she wrote,��� that the Guest of Honour is our most distinguished comrade and poet,��Marcelino Dos Santos, who has agreed personally to launch this very modest salute to Mwalimu���s legacy of liberation.��� He was��a leading freedom fighter��in Mozambique���s Frente de Libertacao de Mocambique (FRELIMO). ���We could not have asked for a more appropriate witness on this occasion,��� intimated Annar, ���for it is Frelimo���s struggles���and victories���that have touched the lives of more Tanzanians more intimately than any other.��� She concluded by stating: ���Here also, there is a story that needs to be told, if I may say so.��� She would be so proud that��Azaria Mbughuni��is writing a book on��Tanzania and the liberation struggle in Southern Africa.

It is my hope her niece, Laila Manji; friends, Anna Pouyat, Walter Bgoya and Mahmood Mamdani, and co-authors of the recently published��Development as Rebellion: A Biography of Julius Nyerere���Issa Shivji, Saida Yahya-Othman, and Ng���wanza Kamata���will make publicly available Annar���s archival materials for posterity. As Laila aptly puts it, these papers are her careful notes and memories of Mwalimu���s extraordinary legacy. May they, together with Annar���s brother, Mohamed Cassam, and their friends, relatives, and compatriots find comfort in what Laila refers to as ���her spirit, her contribution, and her commitment to our common humanity and our Tanzanian heritage.���

Although Annar and I only met once, geographical boundaries did not stop us from furthering such goals. One of the lessons I learned from her is the importance of not mincing words and not refraining from challenging the ideas of others, especially when they depart from historical facts. She once told me: ���Thanks to Pambazuka, I have the luxury of writing what I want outside the mainstream mental habits but always with the essentials in mind, essentials which I learnt under Mwalimu which remain pertinent, for me.��� It was indeed an honor and a privilege to collaborate with someone who christened herself my ���old/aged��shangazi��� (aunt). Fare thee well my dear shangazi.

Toppling statues as a decolonial ethic

Richmond, VA at site of Robert E. Lee Statue. Image credit

<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/mobili/... In Mobili via Flickr CC.

��� Frantz FanonColonialism is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native���s brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of the people, and distorts, disfigures and destroys it.

In the eyes of many Americans, history is unassailable. Absolute. It is a sacred artifact���austere, static and detached from the tumult of everyday life.

Historians have a very different relationship to the record of the past. To them history means contestation, not preservation. In the public discourse, ���revisionist history��� is practically an epithet. But practitioners of history see reshaping and reinterpreting historical accounts as the highest duty of���and perhaps the ultimate rationale for���their craft.

Good history, like a good historian, is never inert. It is dynamic. Restive. Social upheaval is its author, not its adversary. History belongs in the scrum of politics because historical narratives are not merely truth claims; they are assertions of power.

Which brings us to the matter of falling monuments. The current upsurge of struggle has reenergized the Black Lives Matter theme and reinvigorated efforts to remove statues, flags, and other iconography associated with racism, enslavement, and genocide. From Birmingham to Boston to Chicago to Montgomery to Nashville, to say nothing of overseas sites such as the British city of Bristol, protesters have dethroned, decapitated, defaced or otherwise targeted public representations of some of the most venerable members (deceased) of the Great White Canon of Conquest.

Critics often describe such campaigns as attempts to erase history. That outlook generally reflects an entrenched commitment to the defense of racial hierarchy. Yet it also reveals an impoverished understanding of the historical enterprise itself.

The blitz on monuments signifies not the abandonment of history, but rather the rejection of a narrative of modernity created by the heirs of global plunder. Far from an orgy of destruction, the popular assault on the commemorative infrastructure of white supremacy is an act of creation. It is a restructuring���a cleansing of both the public sphere and the consciousness of the aroused masses.

By attacking statues and other emblems of oppression, the demonstrators are fashioning a vernacular counter-history from the depths of alienation and exploitation. They are renouncing the cultural edifice of domination. They are reclaiming history. And in so doing, they may help stimulate a greater intellectual and social awakening.

The spectacle of tumbling monuments recalls other historical episodes in which hated sculptures fell. Through the ages, the toppling of statues has accompanied the overthrow of tyrants. But by practicing an emancipatory philosophy of history, Black Lives Matter activists and others (the latest onslaught on dubious monuments has spread to Native American communities and beyond) are in some ways evoking a rather specific moment of rupture���one rarely imagined, these days, as an analogue to Western experience. Here I have in mind the era of global decolonization.

Today���s street protesters are hardly seeking formal self-government, as were the ���third world��� insurgents of the 20th century. One must be cautious when deploying colonial metaphors. The current uprisings, however, exemplify a cardinal principle of post-World War II anticolonial movements; namely that political revolt requires a corresponding rebellion in the realm of the mind.

The most influential anticolonial thinkers of their day affirmed this idea. Frantz Fanon, a theorist of the Algerian liberation struggle, maintained that the colonized must regurgitate the ruling myths of the colonizer. By severing colonialism���s material and psychological bonds, he wrote, subalterns reorder ���native social forms��� and begin to embody a history of their own design. Amilcar Cabral, a West African revolutionary, believed the mental rehabilitation of subject people occurs on the terrain of historical consciousness. He argued that victims of foreign occupation ���reenter history��� only when they disavow imperialist visions of the past.

In a sense, recent Black Lives Matter mobilizations exhibit a decolonial ethic. The explicit targets of protest are police terror, vigilante violence, and the public emblems of racial subjugation. Yet the uprisings pose a far deeper threat to the status quo. By defying the reigning ideological apparatus, the demonstrations are producing an alternative framework of knowledge. They offer a means of breaking psychologically from the old regime and reconstructing popular consciousness.

The protestors are confronting not only political opposition and police repression, but also a cognitive empire designed to smother critical awareness. As every student of neoliberalism knows, modern capitalism rules by recasting human experience as an endless series of market exchanges. Even the alleged mechanisms of democratic inclusion, from electoral politics to the Internet, aid in the management of collective thought and perception.

The US corporate-political class relies on a continuous loop of propaganda to narcotize its subjects and convert them into supplicants who willingly accept permanent war and obscene racial and economic inequities. The theorist Sheldon Wolin called this process of mass conditioning ���inverted totalitarianism,��� but we might also understand it as a quasi-colonial system of psychological domination.

Mass struggle disrupts that cycle of control. It can help purge imposed values and inspire a collective repudiation of the lies of the dominant order. Once those illusions begin to crumble, the entire system totters. If ordinary people discover that police are unnecessary, or that they (the cops) serve on behalf of the propertied and the powerful, or that a mobilized group of militants can remake society in the streets, then they are apt to question other arrangements as well. They may lose their tolerance for degradation. They may resist the equation of freedom and private consumption. They may reject the notion of an economy, indeed, a democracy, predicated on desperation, debt, punishment, and war.

It may not be inaccurate to view Black Lives Matter as a mode of confrontation politics, based on ideals of radical humanism, that entails a kind of mental decolonization. When all is said and done, police murders may not cease. But another generation of dissidents will reclaim agency and intellectual sovereignty. As long as popular agitation continues, elites will find it more difficult to manipulate the masses and enforce their own version of reality.

Of course, street campaigns have their limitations. The recent antiracist upheavals fall well short of revolutionary events. Nor have most of the protests been overtly antisystemic. Stunned by the breadth and ferocity of the early insurrections, the US corporate and political establishments have scrambled to regain the balance of power and restore the veneer of legitimacy. Their attempts to bureaucratize, coopt, and commodify the antiracist revolt suggest that aspects of the movement remain open to bourgeois capture.

Here, again, anticolonial theory is relevant. During a 1972 visit to the US at the height of the Black Power movement, Am��lcar Cabral, leader of the Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verdean struggle, urged African Americans to address the underlying causes���and not merely the symptoms���of racial oppression. ���If a bandit comes to my house and I have a gun,��� he told a gathering of black activists in New York City, ���I cannot shoot the shadow of the bandit; I have to shoot the bandit. Many people lose energy and effort, and make sacrifices combating shadows. We have to combat the material reality that produces the shadow.���

The assertions of Cabral, who was assassinated in 1973, helped clarify the political task of contemporary African American radicals. At the time, the Nixon administration had joined some African American figures in attempting to redefine Black Power as ���black capitalism.��� Members of the black American left, however, rejected such machinations. Instead they strove to deepen the anticapitalist elements of the domestic freedom movement by demonstrating that the multinational banks and corporations that perpetuated colonial arrangements abroad also presided over the economic marginalization of black communities at home.

Today antiracist organizers face a similar test: they must combat the material realities of oppression while avoiding a dangerous preoccupation with its secondary manifestations. Symbols are important; they can shape consciousness and order people���s lives. But activists cannot allow their struggles to be confined to the arena of symbolic reform.

The decision of Quaker Oats to rebrand their ���Aunt Jemima��� syrup; the proliferation of ���Black Lives Matter��� street murals and lawn signs; and the withdrawal of white actors who voice nonwhite characters in animated series all represent the silhouettes but not the substance of change. Such rituals of racial enlightenment are not merely superficial; they are signs of a system attempting to regain control. Faced with a virtually unprecedented eruption of popular dissent, NGOs, corporate executives, and other administrators are hoping to replace the old frameworks of power with more refined patterns of domination. A generation of freedom fighters once called this style of management ���neocolonialism.���

Whether insurgent forces within Black Lives Matter can resist such schemes and expand the mass rebellion remains uncertain. Police defunding as a fundamental challenge to state violence (rather than as a mere budgetary adjustment) seems essential to any meaningful program of transformation. Yet even more dramatic campaigns may also materialize. The tides of antiracist protest have already mingled with wider currents of economic and social unrest. The George Floyd uprisings would not have been as widespread or prolonged had they not arisen against a backdrop of wildcat strikes and grassroots agitation intensified by COVID-19 and spiraling precarity.

If these and other tendencies continue to interact, the result could be a more sustained insurrection of the vulnerable, the exploited, and the abandoned. Battles against punitive policing and white supremacy could infuse and bolster demands for economic redistribution, unionization, immigrant justice, ecological repair, LGBTQ rights, the dismantling of mass incarceration, and the restoration of indigenous lands. (For Native Americans, it must be said, colonialism is not an evocative metaphor but a devastating historical reality.)

Racial terror is a patent violation of human dignity and has rightfully become the nucleus of modern protest. But it is also deeply enmeshed with the routine forms of violence produced by austerity and capitalist retrenchment.

Decolonization may be a useful analogy for the latest Black Lives Matter counteroffensives because the struggles that emanated from Minneapolis in late May are both epic and, as they stand, incapable of transferring to the dispossessed masses genuine wealth and power. The drama of Third World independence, one must recall, never fulfilled the radical promise of socialist transformation. Nor can toppling a statue reconfigure the political economy that continues to render entire populations disposable.

Yet the form and character of rebellion remain as fluid today as they were in the heyday of the anticolonial crusades. As they grapple with existing relations of power, more George Floyd demonstrators will undergo the revolutionary process that Cabral described as ���a reconversion of minds.��� They will discard the prevailing mythologies and inaugurate a politics commensurate with the crises of our time. Dedicated to truth over tradition, they will craft new pedagogies, rewrite master narratives and reinhabit the stage of history.

July 27, 2020

Reclaiming Africa���s early post-independence history

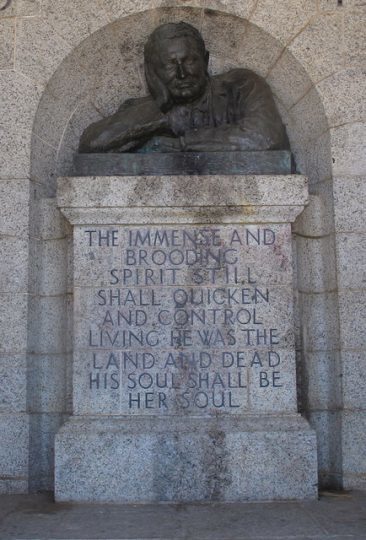

Kwame Nkrumah's Mausoleum. Image credit

Guido Sohne via Flickr CC.

This article introduces the series Reclaiming Africa���s History from Post-Colonialisms Today (PCT), a research and advocacy project of activist-intellectuals on the continent recapturing progressive thought and policies from early post-independence Africa to address contemporary development challenges.

In 1965, Kwame Nkrumah described the paradox of neocolonialism in Africa, in which ���the soil continue[s] to enrich, not Africans predominantly, but groups and individuals who operate to Africa’s impoverishment.��� He captured what continues to be an essential feature of Africa���s political economy. Enforced through neoliberalism in the contemporary period, many African states remain dependent on exporting primary commodities to enrich the global North, with their domestic policy constrained by unequal aid, trade, and investment regimes, and what is now, after almost four decades of structural adjustment, an almost permanent state of austerity. Despite its manifest failures, neoliberalism continues to dominate policy making on the continent, bolstered by an ideological onslaught and a conditionality regime that has stifled any space to imagine and pursue alternatives.

African governments in the immediate post-independence period challenged the neocolonial exploitation of the continent. Whatever their ideological inclinations, governments saw the key task of their time as securing their political and economic agency by breaking out of their subordinate place in the global economic order and imagining a new one. In contrast with the contemporary externalization of policymaking, they responded creatively to the material interests of the majority of ordinary peoples. The state sponsored and/or established industries; provided universal education to foster skills necessary for transforming the economy; built social infrastructure to ease reproductive labor; delinked from colonial currencies; made resources available for domestic producers and women through developmentalist central bank policies; worked to diversify revenue sources; and built regional solidarity.

The post-independence project was undermined and derailed by the active efforts of North governments including their former colonizers. They disrupted African governments through assassination attempts and coups, and opportunistically seized on the 1980s commodity crash that devastated African economies, compelling them to accept World Bank/International Monetary Fund (WB/IMF) loans conditional on liberalization, austerity, and privatization. Four decades later, the ideological dominance of neoliberalism is profound. Spaces of progressive thought and learning have been fragmented, knowledge production has been monopolized by the free market logic, and tendentious misreadings of the post-independence period as ideological, statist, and inefficient abound, facilitating a sense best summed up by the Thatcherite pronouncement that ���there is no alternative.���

Recasting post-independence policies

Three widespread misreadings of the post-independence period were wielded to push structural adjustment programs in the 1980s and continue to underpin the neoliberal hegemony in Africa.

Firstly, the WB/IMF and North governments cast post-independence leaders as excessively ideological in order to discredit the entire experience. In reality, however, while there was an ideological ferment, the range of policies adopted by African governments to assert economic sovereignty were similar across the ideological spectrum. Capitalist oriented Kenya, socialist humanist Zambia, scientific socialist Ghana, Negritudist Senegal, and Houphouet-Boigny���s C��te d���Ivoire (then the Ivory Coast) constructed a central role for the state in post-colonial social and economic transformation, often driven by the collective ethos of meeting society���s needs in the absence of any significant local private capitalist class and the levels of investment necessary for transformation. This often translated to the creation of state-owned enterprises and heavy investment in human capital; interventionist fiscal and monetary policies; and a uniform (if ultimately inconsistent) commitment to import substitution industrialization. The false homogenization of the post-independence development project as a failure of ideology has allowed neoliberalism to be positioned as an ���objective��� and ���rational��� remedy to this period rather than an ideology itself, liable to contestation.

Secondly, the strong role of the state in post-independence development policy has been blamed for Africa���s development problems and used to justify the installation of the market as the solution, laying the basis for large-scale privatization and deregulation. In reality, however, all post-independence economies were largely market-oriented with key sectors dominated by foreign capital, serving as a continuation of colonial patterns. Post-independence governments did, however, set out to regulate foreign capital through, for example, nationalizing strategic industries and capital controls. Ultimately, the failure to curtail the dominance of foreign capital, continued dependence on primary commodity export, and the vagaries of the global economic system worked to undermine the post-independence development project. This reality has been obscured to scapegoat state intervention, justifying the further encroachment of foreign capital and continued integration into an unequal global economic order. Thandika Mkandawire and Charles Soludo outlined the hypocrisy of this narrative, noting that the post-independence project was not outside the dominant policy orientation globally. Post-depression, Europe was being reconstructed through massive state-driven intervention, and the Marshall Plan led by the United States was far from a market driven exercise. As Ha-Joon Chang has noted, the delegitimization of the state as a development actor in Africa denied the continent the very policy instruments used by the North to develop.

Finally, the myth of weak and inefficient institutions in the post-independence period underpinned efforts to dismantle the state and its role in the economy and social provisioning. This misrepresents what was a uniquely consistent policy period on the continent, in which there was stable tariff policy and taxation, and public development plans and budgets. Mkandawire and Soludo suggest neoliberal actors like the WB/IMF simply failed to understand the multiple roles of institutions in the post-independence period: rural post offices were also savings banks and meeting places for the community, the Cocoa Marketing Board in Ghana also raised money to fund education. As such, when they were dismantled and replaced with standardized, monotasked institutions during structural adjustment, it ripped the social fabric that was integral to the post-independence agenda. For example, after the state-run Cocoa Marketing Board was dismantled, universities were forced to raise funds privately, and those donors over time reshaped and de-politicized the curriculum. The resulting sense of dislocation, alienation, and commodification has undermined the deep efforts of post-independence governments to foster socio-economic inclusion.

The post-independence period had a range of limitations, critically related to the failure to adequately address gender imbalances, enable independent workers and peasants movements, or build strong decentralized systems of local governance. However, when compared to the neoliberal era, there was inspiring clarity around the goal of structural transformation and a wealth of policy efforts aimed at transforming the neocolonial patterns that still grip the continent. The questions post-independence governments asked, to which the policies were formulated as answers, were all but ignored by neoliberalism. It is, therefore, of value for Africans to go beyond the persistent narratives that serve to bolster neoliberalism, and reassert Africa���s experiences in this period as an anchor for development alternatives.

White eyes

Image credit Patrick Tomasso (@impatrickt) via Unsplash.

The best way to listen to music is on shuffle���one never knows what comes next or what to expect. The unpredictability, the sudden change of groove as the music shuffles, reminds me of life as we know it���or, perhaps it is like being in a Leye Adenle crime novel, an unpredictable universe. When life gets complicated, I plug into my playlist of Afrobeats songs, listening as the steady groove of Niniola���s Maradona segues into Timaya���s reggae infused Kom Kom. Here, I find a comforting escape. The appeal and power of Afrobeats lies in its heavy danceable musical beats, with vocals riding the waves of the riddim, inviting the listener to konko-below and forget their sorrow. With every note and beat drop, it is clear that the musical team behind the song, just like the listeners, are enjoying themselves.

Contemporary Afropop music is unapologetically local; the lyrics a stream of often vacuous words strung together, just for rhyming effect. This creates memorable rhythm and shared social symbols from random objects���like how cassava becomes a metaphoric phallus or how ���assurance,��� according to�� Afropop superstar Davido���s prescription, is a conferment of expensive gifts as an expression of love. Made without an external white gaze, Afrobeats functions without rules, channeling the spirit and language of the locality of production to have far reaching aesthetic merit and social impact in ways that Anglophone African literature rarely does. This is instructive, perhaps anthropologic: as a genre, Afrobeats���lyrics proudly sung in indigenous languages or pidgin English, interspersed here and there with English or French���grew within the African continent, finds its popularity at home first before achieving fame abroad and still holds strongly to its African identity. Despite its growing popularity abroad, the genre makes no effort to make itself eligible�� to any audience apart from its original constituents in Africa.

The contemporary literary equivalent to endogenous Afrobeats is the market literature tradition in Kano, northern Nigeria. For many years, writers, like Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, writing in Hausa, have explored their lives for themselves and in their language, using paper to quietly challenge a conservative society by telling stories of life and love desired and lived in secret. For these writers, mostly women, there is little need to ���perform Africa��� because their readers are close to home, grounded in their language and the signs it points to, as well as the social meaning it connotes.

The idea of ���performing Africa��� is rooted in pandering to a Western audience by deploying the stereotypes often associated with the continent. Because Afrobeats is made with a local audience in mind, it has stayed above this posturing. However, many Anglophone African writers have had to contend with African critics calling out the stereotypes, the performativity, the false representation, and pandering present in some African literature���or as Makoma wa Ngugi states in his book, The Rise of the African Novel: ���the battle that Achebe carried to Conrad has now become fratricidal to the extent that African writers and critics are accusing other African writers of offering the West a Conradian Africa.��� This alludes to how the sad phenomenon of ���poverty porn��� plays a central role in performing Africa through embodying a historical Western perception and stereotypes of Africa and Africans.

As a discussion within Africa���s literary circle and beyond, critics of poverty porn have, for the last decade, pushed the boundaries of representation. But, perhaps most importantly, they tell the world that African identity isn���t a single, simple idea���one that is riddled with poverty, starving children, helpless women, and jobless men���rather, it���s a complex, multifaceted confluence of ideas and realities. Helon Habila points to this in his critique of NoViolet Bulawayo���s debut novel We Need New Names. And over the last decade, the Nigerian critic, Ikhide Ikhleoa, has called out instances of poverty porn in African literature shortlisted for awards. Given the diversity of the continent and genres, most of the examples used here are culled from Nigeria.

In order to break this poverty porn induced perception of Africa and the performance of Africa in literature, the need then arises to present an alternative story far removed from the endless destitution in media; to produce works that conform to a certain progressive standard and avoid the trap of poverty porn. That is, literary works that show the Western eye a cosmopolitan Africa, with trendy coffee shops and fashion outlets dotting the streets of Yaba, Lagos; the tech revolution sweeping through Nairobi, Kenya; the high-rise buildings dotting the skyline of Johannesburg; or successful, middle class Africans in the diaspora���otherwise called Afropolitans. Makoma wa Ngugi goes on to critique this alternative representation of Africa���particularly in Chimamanda Adichie���s works describing them as suffering ���from an African, middle-class aesthetic��� and ���diaspora slumming��� because Adichie chose not to tell the ���single story of poor, fly-infested Africans.���

Smashed in by historical and ill-informed stereotypes about Africa and critical calls to write a new Africa, it might seem that there is no in-between; an African writer is either writing poverty porn or over-representing by telling stories of successful, latte drinking middle-class family melodrama. This demand on African writers limits the imagination, the scope of their writing and the power to speak truth to power���or as the Nigerian-Ghanaian writer, Taiye Selasi, argues, results in the pigeonholing of African writers and denial of artistic freedom. But if the work of the artist is to create (and stay honest to reality, without prejudice or agenda) and this work ends with creation, does it then make sense to limit the imagination of an African writer with the burden of ideal representation?

Habila, in response to what he calls writes that the better parts of the book occur when ���Bulawayo ��� is enjoying herself���when she doesn’t feel she needs to be both a player and a commentator at the same time.��� Then Habila writes: ���The world is a dark and ugly place, a lot of that ugliness and injustice is present in Africa, but we don’t turn to literature to confirm that. The news is enough. What we turn to literature for is its ability to transport us beyond the headlines.��� Despite his advice, Habila fails to see how his criticism of Bulawayo censors and denies her the privilege of self-expression and enjoyment as she attempts to write and speak her truth. Perhaps an even more dangerous implication of Habila���s criticism is that if Africans fail to tell these stories then others will, �� la American Dirt style. And, on the other hand, he then goes on to confirm the reality of many lives on the continent which Bulawayo writes about.

The death winds of the Spanish Flu bled into colonial West Africa in 1918, an uninvited guest arriving aboard a colonial-era ship filled with infected bodies. With the stench of death in the air, citizens of West Africa���particularly in the hinterlands, far removed from the Atlantic Ocean and news reports���were sent into a panic as they attempted to make sense of this new disease that caused otherwise healthy men and women to drop dead like flies within days. Over the years, historians, scientists, and social scientists have attempted to explore the impact of this imperial disease on British colonies, using facts and figures as an anchor. Yet, despite its reputation as a vessel of objectivity and quantitative data, numbers do not tell the whole story, often obscuring the human face of an issue.

It is through the words of Buchi Emecheta in a Slave Girl and Elechi Amadi in The Great Ponds that we gain a more critical, humane insight into the extent of the damage the influenza pandemic wrought; how small warring communities in the hinterlands of eastern Nigeria sought for an explanation and prayed for deliverance; how the pandemic affected local economics and the little people whose face and lives are subsumed and lost under facts and figures. It is in this same way that Charles Dickens literary works play a crucial role in how we relate to the poverty of London in the Victorian era; and the Bronte sisters recount for us the lives of the middle-class of that era. Should we, in any case, accuse Dickens of writing poverty porn for attempting to represent the otherwise unseen and unheard members of Victorian society whose lives were shaped by poverty and trauma? Or accuse the Bronte sisters of suffering from a middle-class aesthetic fever?

Literary works have aesthetic merit and are social documentaries, giving the future access to the lives of yesterday and today. Literature reflects the mood and sign of times gone by or fast receding. Placed side by side, the works of Dickens and the Bront��s present a fuller picture of the times they lived in, allowing today the opportunity to imagine yesterday from a variety of experiences while giving us language to describe them. To then accuse African writers of either writing poverty porn or middle-class anxieties when they write their reality is to censor and to deny tomorrow access to the variegated life stories being fashioned today. And even more dangerous is the harm criticism of poverty porn wrecks on the confidence of a writer. This burden of presentation in African literature comes with guilt and a political burden when writing: I am writing the truth, but does it cater to a Western lens? Does my writing, true as it may be to the lived experiences of a group within the continent, feed into the unfavorable Western view of Africa? Is there an intentional erasure of the stories of millions of Africans when we label some African literature poverty porn? Slowly, unbeknownst to the critic, these questions feed into a denial of agency and access to self-definition for an African writer who writes what they know. What this does is to bog the writer down with the responsibility to represent a perceived African ideal rather than the reality as they see it, at the risk of the truth.

Perhaps one could argue, and not be entirely wrong, that critics who accuse and berate African writers of writing poverty porn are themselves embarrassed about the reality of Africa���particularly in relation to the West. Often, these critics are in the diaspora from where they look down on Africa, cringing at the news images coming from the continent. Both the critic and the writer worry about representation and the readers��� perception of Africa, perhaps the question we should be asking is: for whom does an African writer write? It stands to be reasoned that the problem is not with what is written, but for whom it is written for. Afrobeats (or even Nollywood, Nigeria���s large film industry) does not carry the burden of representation because its primary audience and market are Africans. If African literature was produced with an African market in mind, would poverty porn be an issue seeing as we Africans are all so familiar with the reality of our states? It makes sense, at this point, to note that although often used interchangeably, a product���s audience and its market are distinct, with the former being more specific and narrowly defined than the latter. Consider for instance Elnathan John���s Born on a Tuesday, a book that is distinctly local to a specific part of northern Nigeria, with a domestic resonance for its audience. Yet, as the book���s international success indicates, the market for such books is global.

This distinction between audience and market for African literature is a result of the publishing economy, and its historical set-up, with deeper implications on the politics of writing. With a well-defined structure, network and a long history, publishing in the West is a bigger enterprise than it is in Africa. This explains why all the major prizes, structures of literary recognition, and other symbolic legitimization are in the West. And why African writers often look to the West for literary and, sometimes, commercial success and legitimacy. The writer, Adaeze Tricia Nwaubani, argues that African writers ���are telling only the stories that foreigners allow us to tell.��� This statement points to the history of contemporary African literature, as it paints an immediate picture of how African writers, in a bid to achieve success and appeal to (often white) publishers, editors, and the market abroad, may pander to stereotypes. The insistence of Western publishing and editorial that an authentic representation of Africa must involve poverty and stereotypes shows that the Western vision of Africa is still Conradian.

Yet, Nwaubani���s statement�� is at once true but also very limited as it assumes that literary success can only be achieved in the West, failing to fully recognize���or refusing to acknowledge���the growing publishing environment in the continent, and that some African literature are commercial success in Africa with sales dwarfing many of the well-known text in the West. I recall when I worked as a communications officer at Cassava Republic Press that Sarah Ladipo Manyika���s debut novel, In Dependence, sold over three million copies in Nigeria alone. Yet, authors like Manyika whose publishers are small independent publishers often do not get as much attention as other authors published by big, Western publishers who have probably never even sold close to that figure.

We must allow writers to write without guilt, to explore and honestly tell the story of Africa in the plural without pandering or pigeonholing, bearing in mind that life���whether lived in Aba or Arizona, Benin or Bahia���is complicated. To do this, however, African writers must first reclaim the narrative, and piece together a mosaic of a contemporary Africa, one written with optimism and hopefulness without denigrating the complexity, diversity, humanity and, most importantly, truth of their own vision and imagination.

July 26, 2020

The state of Lake Chad

Remnants of Chad Lake, Chad, February 2015. Image credit Peter Prokosch via GRID-Arendal on Flickr CC.

On March 23, 2020, Boko Haram launched an attack on the Bohoma Peninsula, in the Republic of Chad, in which nearly one hundred Chadian soldiers lost their lives. Chad���s President Idriss D��by personally oversaw the response, aptly titled ���Operation Bohoma Anger.��� The attack was unprecedented for Chad���s military, but the immediate suffering of the region���s vulnerable inhabitants���Lake Chad hosts four riparian states: Chad, Cameroon, Niger, and Nigeria���was not.

Analysts often characterize Boko Haram as a Nigerian movement, which has ���spilled over��� into neighboring states. This narrative comes up short for two reasons. First: it underestimates Boko Haram���s regional appeal since inception. Second: such language betrays deep rooted norms, stemming from Europe���s post-Westphalian political system, on what it means to be a ���state.��� It���s inevitable, then, that these statist frameworks constrain possible solutions. Yet, Boko Haram (and its offshoots) is the result of years of state negligence, in other words: absence of the formal state. The marginalization Lake Chad���s residents feel vis-��-vis government capitals reinvigorates cultural and linguistic links that have long superseded colonial and post-colonial borders. The crisis in Lake Chad is much more than a ���security vacuum���; it will require less emphasis on military solutions, and increased cooperation among riparian nations at the local level.

Lake Chad, both historically and today, is a culturally contiguous region. That ethnic Kanuris���present not only in Nigeria, but also Chad, Niger, and Cameroon���dominate Boko Haram���s membership is well-known. The Kanuri trace their origins to the Kanem-Borno Empire, specifically the Borno State; in 1884 the Berlin West African Conference divided the Kanuri homeland between the French and English. Even after decolonization, Lake Chad���s inhabitants���whether from Niger, Chad, or Cameroon���often have far more in common with each other than their fellow citizens in Niamey, Yaounde, and N���Djamena.

The trans-national capital of Lake Chad is Maiduguri. Despite falling within present-day Nigeria, the predominantly Kanuri-speaking city has long been home to others. As Alexander Thurston notes, by the 1990s ���the city was full of poor migrants fleeing farms, overstretched households, and drought-ridden Niger and Chad.��� Boko Haram���s founders, Muhammad Yusuf and Abubakr Shekau, were born in the rural Nigerian countryside. They and fellow migrants quickly witnessed grinding poverty, inequality, and criminality; in other words, state negligence.

The Nigerian state���s consistent inability to respond to these issues���and when it does, the state is often more violent than the criminals���was clear not only to Nigerians, but Nigeriens, Cameroonians, and Chadians. Unsurprisingly, thousands of Nigeriens heard Yusuf���s preaching against the state in Maiduguri, while Boko Haram���s Chadian followers carried his message to Chad���s capital N���Djamena.

Indeed, state negligence was not only an issue in Nigeria���s northeast. For Lake Chad���s other citizens, Nigerians��� woes vis-��-vis the government resonated with their experiences at home. Niamey and N���Djamena, for example, have long proven disinterested���both from a lack of resources and political will���in integrating their portion of Lake Chad. Diffa���a small Nigerien city and flashpoint in the fight against Boko Haram���prefers Nigeria���s naira to the local currency. Residents are ���less familiar with [their capital] than with Maiduguri.��� Lake Chad���s islands in Chadian territory similarly have little in common, let alone a relationship with, the government in N���Djamena.

It is not surprising, therefore, that some of Lake Chad���s residents see fixed borders, manned by predatory, corrupt officials, and dream of an alternative. Muhammad Yusuf tapped into these frustrations, preaching in 2008 that colonial powers: ���carried out hideous schemes based on their wisdom. For example, present-day Niger and the northern part of Nigeria were one territory [���] there was no boundary between them. It was all an Islamic territory.��� Boko Haram, at least initially, was offering an alternative to the current state���one which reflected more accurately Lake Chad���s realities.

Thus, Lake Chad represents a particularly difficult paradox for policy makers. The area is highly integrated locally, but differences in official language (Francophone vs. Anglophone), institutions���Niger and Nigeria are part of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) vs. Cameroon and Chad in the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS)���and low levels of trade mean the region as a whole is fragmented. As one paper put it succinctly: Lake Chad is ���historically far more integrated from a bottom-up perspective than it is from a top-down.��� Until this is addressed, Boko Haram, or a different version of it, will continue to exist.

Adding to diplomatic difficulties, the threat of terrorism in the region, from Boko Haram and others, has led to over-militarization at the expense of holistic, regional approaches. Especially with the beginning of the Mali Crisis in 2011, the west and regional states have met the terrorist threat with a ���military approach to conflict resolution��� typical of our post-September 11 world. Yet, flooding the region with weapons, and arming groups against the jihadi threat, has predictably led to militarized intercommunal conflict, separate from the fight against extremism.

Military cooperation, primarily through the Multinational Joint Task Force (MJTF), is mired in the same lack of trust that affect bilateral diplomatic ties. Nigeria, Chad, and Cameroon all continue to dispute certain territories around Lake Chad. Moreover, each country is in the habit of blaming others for their own militaries��� ineffectiveness. The political temptation to declare others ���aren���t pulling their weight��� is frustratingly prevalent. The military response���the ultimate state solution���is coming up short.

The riparian governments have long recognized the need for regional integration. The Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), formed in 1964 with Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria, and as of 2008 including the Central African Republic and Libya, has made efforts to facilitate conflict prevention through water management, conservation, and regional integration. But even the LCBC cites ���neglect of the region by each of the four riparian states��� first among obstacles. Moreover, the LCBC itself suffers from weak staffing, lack of capacity, and inability to coordinate with relevant regional institutions.

The Lake Chad Basin Governors��� Forum���representing Lake Chad���s eight regions���in 2019 reaffirmed the need for cross-border cooperation, emphasizing a comprehensive approach to prosecution, rehabilitation, and reintegration of fighters in the region (PRR). This is a start, especially since it recognizes the need to counter Boko Haram���s ideology in Lake Chad. But the four governments must do much more to divert attention and funding from military solutions and focus on regional integration.

First, the four states in Lake Chad should create a regional council, composed of religious scholars and imams, to address youth radicalization. International conferences can emphasize the role Islam plays in bringing peace and stability to the region. In January, Mauritania hosted a conference of Islamic scholars on ���The Role of Islam in Africa: Tolerance and Moderation in the Face of Internal Struggles.��� The conference sought to harmonize the position of the ���largest Muslim ulemas in Africa��� vis-��-vis the threat of extremism. Religious scholars in Lake Chad should do the same.

Second, on the economic front, citizens of Lake Chad must be able to cross borders freely, at all times. As many humanitarian organizations have frequently noted, international borders greatly affect food security and transportation costs. Counterterrorism operations result in closed borders that disrupt markets, making food unaffordable for residents and exacerbating conflict. Freedom of movement in Lake Chad would be the greatest counterargument to Boko Haram���s ideology of ���false borders.���

In the long-term, local governors in Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria must be able to cooperate amongst themselves to tackle problems, free from outside interference from their respective capitals. This means decentralization and greater autonomy for Lake Chad. Decentralization, however, can only be achieved with greater regional unity.

Kwame Nkrumah recognized the importance of African unity 60 years go. In his famous 1963 speech in Addis Ababa, Nkrumah declared: ���unite we must. Without necessarily sacrificing our sovereignties, big or small, we can here and now forge a political union based on defense, foreign affairs and diplomacy, and a common citizenship [���] We must unite in order to achieve the full liberation of our continent.��� Definitions change over time, but Lake Chadian���s desire for freedom from terrorism, hunger, and poverty will always remain a basic requirement of liberation.

Among all these difficult challenges, there is much cause for hope. The crises of which Boko Haram is a manifestation: state negligence, and its educational, environmental, and socio-economic ramifications, are not unique. All nations now face climate change, rising inequality, and unemployment from technological innovation. These are phenomena that no traditional nation-state is equipped to solve.

Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria have a chance to tackle these issues, together, at the regional level. If they prove successful in Lake Chad, then they will provide a model for all other nations to emulate. They could, as Nkrumah did 60 years before, inspire the world.

July 24, 2020

The second lives of zombie monuments

[image error]

Image credit Kim Gurney.

Five years ago, the toppling of a statue of Cecil Rhodes on a Cape Town campus triggered a social justice movement with global reverberations. In July 2020, a neighboring Rhodes Memorial bust on the slopes of Table Mountain lost its head in an ongoing call and response between global places and spaces where inequities from the past continue to shape the present. Kim Gurney shares a photo series documenting this mutating artwork (2015-2020) and a short backstory to its current fate.

Image credit Kim Gurney.

Image credit Kim Gurney.In July 2020, when law student Chumani Maxwele flung faeces from a portable toilet cannister at the Cecil John Rhodes statue on the University of Cape Town (UCT) campus, he told onlookers that he felt suffocated by the colonial names and memorials. ���Maxwele complained that most black students could not breathe on campus because of the claustrophobia produced by English colonial dominance at UCT,��� wrote anthropologists Shannon Jackson and Steven Robins in a journal article. Maxwele���s protest performance at the base of the statue in April 2015 was politically symbolic: it brought the periphery to the center in a city where inadequate sanitation is just one of many perpetuating inequities. Academics like Jacklyn Cock call this a kind of slow violence, something that extends over time, ���insidious, undramatic and relatively invisible.���

Maxwele���s actions made it all quite plain to see and famously triggered the Rhodes Must Fall movement. This not only eventually toppled the seated bronze figure of Rhodes���carted off in April 2015 by authorities on a flatbed truck���it set off a series of calls and responses for decolonisation and systemic change in society more broadly, which spread to other spaces and places.

Fast forward to 2020 and artworks in public space are once again a vector of rage as public protests ricochet around the globe following the death by asphyxiation of George Floyd, killed by police in Minneapolis in May. Resurgent and sustained Black Lives Matter protests have highlighted the structural racism imbricated into everyday life. These protests have included targeting symbols of colonial, imperialist, and racist pasts. A statue of Edward Colston, a slave trader and merchant, was this month dunked in the harbour in Bristol (UK) and another of Christopher Columbus was decapitated in Boston (US), before being removed by authorities. Following a long and fractious debate, Oxford University (UK) finally decided that it will remove its own Rhodes statue from Oriel College and conduct an inquiry into the issues surrounding it.

Back in South Africa, meanwhile, events this month came full circle.

Image credit Kim Gurney.

Image credit Kim Gurney.At a popular public site on the slopes of Table Mountain, located immediately behind the university campus where Rhodes was in 2015 ousted from his plinth, another iconic Rhodes bust was decapitated with an angle-grinder. Until last week, this bronze artwork gazed out over the whole of Cape Town from its elevated pedestal. It was located at the top of a long flight of steps, with bronze horses and lions to either side, a row of imposing pillars in front; a vast Rhodes Memorial. Now, there is a gaping hole in place of the statue���s head. The right hand is still in situ, where it formerly propped up the pensive head in Rodin-like ���seated thinker��� pose.

It���s the second time this Rhodes statue has been targeted. Five months after Rhodes fell, this same bust in September 2015 lost its nose. It was angle-grinded off in the dead of night and the head was set alight, leaving charcoal marks behind. Bright red graffiti was also spraypainted at the time onto the commemorative stone block underneath: ���The Master���s nose betrays him.��� This in apparent reference to Nikolai Gogol, a 19th century Russian writer, whose absurdist novel The Nose (1836) features a protagonist who wakes up one day to find his nose has left his face and develops a life of its own. His misfortune can be read as downfall brought on by pride. Other graffiti calling Rhodes out was also sprayed alongside. South African National Parks employees, who manage the site, had to scrub it off the following morning.

Image credit Kim Gurney.

Image credit Kim Gurney.An anonymous email sent to an art collective, Tokolos Stencil, at the time suggested the severed nose would go on a journey. The bust regained its nose���a bit of an odd-looking restoration. This aligns with the Gogol script where the nose ultimately returns to its humbled owner. But Rhodes Memorial and other zombie monuments could take a cue from the UCT plinth next door. After Rhodes was removed, the crated void came to symbolically represent a vital open question: how do we deal with the unfinished business of the past? And a surprisingly poetic answer has been spontaneously generated. Far from being empty, the UCT plinth hosts an ongoing performative second life of temporary interventions. These have ranged from graffiti to poetry, performance, signage, art and other disruptions. Together, they contest, negotiate, and enact different ideas of what a common space could be���public space that belongs to everybody and to nobody. The open plinth is a collaborative and constantly mutating art of the commons that can grant some breathing room to reimagine the public sphere.

July 23, 2020

Journalism: The essential non-essential

Image via Internews Europe on Flickr CC.

As a consequence of the pandemic’s financial effects, news organizations have been forced to adapt to the changing times. Many���in Kenya, South Africa, the US and beyond���are closing down or letting staff go. Can journalism survive? Is it our essential non-essential?

This post is from our partnership between the Kenyan website The Elephant and Africa Is a Country. We will be publishing a post from their site every week, curated by Africa Is a Country Contributing Editor, Wangui Kimari.

On April 22, Johannesburg-based Kenyan photographer, Cedric Nzaka, took to Twitter to share his latest conquest. He had shot the cover for South Africa���s Cosmopolitan magazine, featuring Miss Universe, Zozibini Tuni. It was a big deal. Much as Nzaka has worked with various luxury brands over the years, ranging from Vogue to Nike and Netflix, this was his first-ever magazine cover. As he received adulation, Nzaka���s feat quickly morphed from being the guy who shot the latest Cosmopolitan cover to being one who did the magazine���s last cover.

On April 30, Associated Media Publishing, South Africa���s franchise holder for Cosmopolitan, announced that after a four-decade run, the company was permanently closing its doors on May 1, and ceasing publication of all its magazines, including House & Leisure, Good Housekeeping and Women On Wheels, due to the financial crunch brought about by COVID-19. And so, just like that, several editors, writers, photographers, designers, stylists and other production support staff became jobless.

Ordinarily, Nzaka and those like him who are contracted by high-end clients on a need-to-basis may have the privilege of having potential clients lurking in the shadows, but not with COVID-19 in the picture. With event cancelations and a lull in advertising, there is not much work for commercial photographers. For writers and editors, it means going freelance, a not-so-easy ballgame for those accustomed to structured work regimes and timely paychecks. It means sending pitches with no guarantee of being commissioned, an exercise which requires thick skin due to the deluge of rejections accompanying this new reality. Presently, things look bleaker with numerous international publications deciding to no longer engage freelancers.

It wasn���t only glossy magazines that took a hit. The Mail and Guardian (M&G), one of Africa���s better known newspapers, found itself in a tight spot too. On March 27, the editor-in-chief, Khadija Patel, the deputy editor, Beauregard Tromp, and the Africa editor, Simon Allison, led the newsroom in appealing to readers on Twitter to subscribe to the paper. They weren���t sure they would afford to pay salaries in the coming months. Moving with speed to innovate, they launched The Continent, a digital newspaper reporting on Africa that is distributed through email and WhatsApp, a move aimed at growing regional readership and opening up future revenue streams. Then, on May 9, Patel and Tromp pulled a surprise move by resigning as editor and deputy editor, prompting speculation that their departure may be the outcome of the current financial ripples.

As Ferial Haffajee, former editor-in-chief of the M&G and later City Press writes in the Daily Maverick about her conversations with Patel, it wasn���t the first time the paper was in need of support from its readership. Thirty-two years ago, the M&G made an almost similar call to the public.

���Near her office is a 1988 poster of the first��Weekly Mail��(the��M&G���s original name) when then editors Anton Harber and Irwin Manoim ran a campaign called Save the Wail,��� Haffajee writes of her visit to Patel���s M&G office. ���Then Minister of Home Affairs Stoffel Botha threatened to ban the title and on its cover, the paper ran the clarion call ���DON���T LET US GO QUIETLY���, they asked readers. ���Carry on reading us. Carry on subscribing. Make a fuss.������

Patel���s Twitter call for subscriptions delivered an impressive 30 percent increase in paying readers.

The news business isn���t doing so well in Kenya either. On April 2, Radio Africa Group chairman, Patrick Quarcoo, wrote to employees explaining that while job losses will remain an option of last resort, pay cuts were inevitable, considering that revenue streams were fast drying up. Effective April 1, Quarcoo announced, employees taking home a gross salary of over Sh100,000 will take a 30 percent cut, while those earning below this amount will have their salaries reduced by 20 percent. There was a promise that the move (termed interim) would be reviewed periodically.

And even though it had already effected pay reductions, the Nation Media Group clarified on July 1 that salary cuts will last until December 2020���this while breaking the news that starting July 3, a chunk of its workforce will be immediately relieved of its duties.

Earlier on, on March 12, the Standard Group���s Orlando Lyomu sent an internal memo on the impending laying off of 170 employees, a purge staggered over a few months. However, it was the reduction in earnings by between 20 percent and 50 percent at the Mediamax Network that caused a frenzy, leading to resignations and court action. There was temporary relief until the morning of June 22, when over 100 staffers woke up to text messages declaring their roles redundant.

The ‘infodemic’

With the advent of COVID-19, there was a warning by the World Health Organization (WHO)���s director general, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, that as the pandemic rears its ugly head, it has a notorious twin in an ongoing ���infodemic������a flood of misinformation. It was, therefore, upon journalists to take the lead in educating the public in a bid to ���flatten the curve.���

This announcement resulted in a deluge of infographics, explainers, think pieces, and interviews with epidemiologists and other public health practitioners. As governments articulated their responses in war-time lexicon, it was journalists who stepped in and cut out the militarism by being on message about the sorts of individual and communal mitigation measures that were needed to curb the virus. It was journalists who covered newsworthy occurrences that could have been overshadowed by COVID-19, including police violence on the pretext of containing the virus.

It was therefore expected that when the dusk-to-dawn curfew took effect in Kenya, journalists were listed as essential service providers, and were permitted to move around past 7pm and to travel in and out of areas where cessation of movement was enforced.

However, the recent expulsion of journalists from newsrooms makes one wonder whether they are still considered essential service providers. A major concern has been the disconnect between media top dogs and their juniors, with bosses proving that all they need is a flimsy excuse for them to throw their colleagues under the bus.

In his piece, ���Newsrooms are in revolt, the bosses are in their country homes,��� New York Times columnist Ben Smith juxtaposes the realities of the lives of journalists in the US against those of their bosses, where after COVID-19 hit, top media executives retreated to their out-of-town residences with swimming pools and access to golf courses, while reporters who do the donkey work, were left in limbo. Those lucky not to have lost their jobs suffered a massive pay reduction or were furloughed. They remained stuck in the city, unsure of whether their paycheck-to-paycheck existence would sustain them during and after the pandemic.

Smith should know a thing or two about income and other disparities within newsrooms, having himself been the editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed. By shining a light on the opulent lifestyle of those who occupy the higher echelons of journalism (which he himself enjoys, courtesy of his position and income), he is by extension self-indicting in what seems to be the new era of accountability in media and other industries.

‘Churnalism’

In their defense, media bosses always play the redundancy card whenever they need to deploy the axe. One may wonder: how does a newsroom become redundant?

In ���The slow death of modern journalism��� published in The Tribune, an anonymous reporter recounts the travails of working in modern-day newsrooms, where productivity has now been reduced to how many shallow clickbait articles one is required to produce per day for the benefit of advertisers.

���This was the state of journalism before the coronavirus upended our lives, and it is still the state of the journalist in a time of global crisis,��� the anonymous reporter wrote. ���A handful of reporters, probably those you follow on social media, have the time and luxury to produce work in the public interest while many of us, not for want of ambition or ideas, spend our time pumping out rubbish in the knowledge that we can be spiked at a moment���s notice.���

In his 2008 book, Flat Earth News, the investigative journalist Nick Davies called this practice ���churnalism������a reference to the quantity and quality of work reporters are expected to produce. According to the anonymous reporter, churnalism means rehashing content from other platforms that broke the story earlier so that reporters don���t need to leave their desks to produce five pieces a day.

When they see their staff as agents of churnalism as opposed to journalists doing intellectual heavy-lifting, media bosses find it easy to declare them redundant when the opportunity arises. The irony is, it is the same bosses who devise visions for churnalism. With productivity reduced to the bare minimum, staffers become redundant by design from the word go; their being on the payroll appears like an act of benevolence.

Yet media bosses don���t act on their own; behind them are media owners, the majority of whom care about nothing but the bottom line. These ownership intricacies and the cloud of terror hovering over newsrooms, courtesy of profit-by-all-means proprietors, is possibly best captured by Savannah Jacobson, a Columbia Journalism Review Delacorte Magazine Fellow. In a piece on the New York hedge fund Alden Global Capital���s takeover of nearly 200 newspapers and resultant cuts, Jacobson terms the fund ���the most feared owner in American journalism.��� The article exposes how investors��� lives are ���punctuated by summer trips to Luxembourg and the French Riviera,��� while ���pens and notebooks disappear from newsrooms��� due to low budgets.

Using the example of the East Bay Times, which won a 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Reporting, Jacobson illustrates how regardless of how many journalistic highs a newsroom attains, hedge funders, who are not interested in journalism and only care about how much money they can squeeze out of the industry, go ahead to purge newspapers���as if achievement should be rewarded with punishment. Over a two-year period, more than half the employees were sent packing as the hedge fund works even harder to acquire stakes in more newspapers.

���Winning a Pulitzer Prize doesn���t change the economics of the company,��� said the��East Bay Times���s executive editor, Neil Chase, ���so why would it change the attitude of the owners?���

A ‘media extinction event’

As COVID-19 unraveled, there was an increase in think pieces on the financial and other dangers faced by newsrooms in Africa and elsewhere. Writing in The Guardian, journalist Kaamil Ahmed references the feasibility study for the establishment of an International Fund for Public Interest Media (IFPIM) conducted by media philanthropy Luminate, which warns that COVID-19 could be a ���media extinction event.��� Even before the pandemic, Luminate was pushing for the creation of the IFPIM so that media independence and sustainability is guaranteed, especially during turbulent times such as these, without profit-making being the sole consideration.

���The news media needs to be reclaimed as a public good,��� Ahmed quotes former M&G editor-in-chief Khadija Patel, who also serves as vice chairperson of the International Press Institute. ���It should not be seen as the playground of a few billionaires. The saddest sign would be for us to emerge from this pandemic with a handful of billionaires controlling all of our news.���

Revisiting his tenures as editor of the Cape Angus and the Cape Times, South African journalist Gasant Abarder opines that COVID-19 is the final straw that broke the newspaper industry���s already breaking back. Abarder, who says that he has watched print media slowly go to the dogs over a 17-year period, lays the blame on non-responsive editors and owners who did not pay attention and did not move speedily to innovate with the arrival of online classified sites such as OLX, followed by the exponential growth of social media. Abrader laments the edging out of older, more seasoned hands in exchange for a younger lot who may be talented but who ���are paid less to do far more. They must tweet, shoot videos and come back to the office to write a few stories.��� He believes that news organizations still need a few grey heads with institutional memory on their payrolls.

���But the newspapers that grew their circulation were owned by the people who knew this was a long play and that investment in quality journalism brought rewards,������ he writes. ���Look at The New York Times, The Washington Post and the Evening Standard. They invested in quality journalism and are now seeing the rewards after just a few years. The Evening Standard became a free paper to commuters on the London Underground. With guaranteed eyeballs, 650,000 copies were put in the hands of the commuters and advertising yields went through the roof.���

Apart from adapting to the changing times, Abrader makes a strong case for good storytelling. He gives examples of specific interventions he resorted to in trying to salvage what was already a dwindling newspaper when he was recalled as editor to do the firefighting. Not keen on selling the previous day���s events as news, he made a deliberate attempt to introduce powerful reporting, including covering the homelessness crisis in Cape Town extensively, going as far as letting a street dweller write the cover story, and allowing students to edit the paper during the #FeesMustFall protests. He admits that this and other efforts came too little too late. By the time he was leaving in 2016, the Cape Angus had only 10 employees, including Abrader himself, down from 57 staffers in 2009 when he first worked at the paper.

Why we do what we do

Accepting his position as acting editor-in-chief for the Mail and Guardian following Khadija Patel���s exit, investigative environment reporter, Sipho Kings, wrote about the cost of producing impactful journalism, coverage which isn���t always considered sexy at the time of writing and publishing. Paying tribute to those he says are willing to fund journalism as a public good, Kings referenced the M&G���s own history, where in the early days, reporters mortgaged their homes to fund the operation. That was before The Guardian stepped in, after which the non-profit Media Development Investment Fund bolstered things, with employees owning 10 per cent of the company.

���There are few newsrooms that take this kind of reporting seriously,��� Kings wrote regarding his coverage of climate change, and how unfashionable it was at the beginning. ���The M&G is one of them. It costs money to send skilled reporters and photographers to remote areas. It takes bravery to put those stories on the front cover of the newspaper���I am frequently reminded that one of the worst-ever selling editions of the M&G had a climate change story on the cover.���

Yet, much as it is desirable, journalism isn���t strictly about whether the work results in the sale of thousands of newspapers every morning or having stories trending on Twitter, which ties to the fact that it also isn���t about blind profiteering. In exercising oversight, journalism will from time to time be the bearer of unpopular opinions, or find itself alone in championing news causes such as climate change, which take a long time to become popular. In these lonely and sometimes dark streets of pioneering coverage, journalists remain true to their vocation, sometimes paying the ultimate price with their lives and livelihoods. It therefore beats logic that these individuals should be the first to be sacrificed at the altar of capitalism.

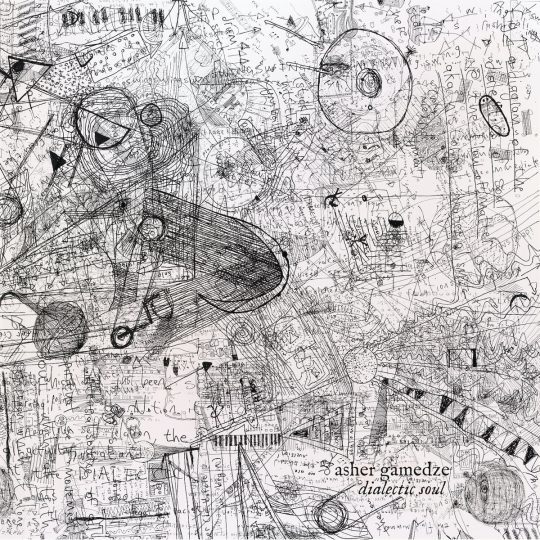

The soul is dialectic

Dialectic Soul album cover.

The drummer Asher Gamedze’s album, Dialectic Soul is out, released in early July 2020 via On The Corner record label. This promises to be the one of the most important releases of the new decade and an important footprint in the history of South African jazz. Through this record, we are taken through the genealogy of the pan-African struggle and resistance against colonialism, capitalism, and slavery both within the continent and in the diaspora. In his introductory essay of the album, the radical historian Robin D.G. Kelley describes it as ���the most joyful proclamation of world revolution���cooler than the Internationale.���