Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 167

July 3, 2020

Independence Day

A mural of George Floyd in Minneapolis, a city with the largest Somali diaspora in the US. Image credit

jpellgen (@1179_jp) via Flickr CC.

��� A Somali proverbDab aan kullaylkiisa la arag dambaskiisa lagama leexdo.

(Until you know how the fire burns you are not afraid of the ashes.)

Writing in October 2019, in the wake of yet another xenophobic rally held by United States President Donald Trump in Minneapolis, Minnesota, political scientist Joe Lowndes reflected on the lessons that the Somali community in the Twin Cities held for a new vision of the country. In particular, Lowndes highlighted the work of Minnesota’s own US representative, Ilhan Omar, whose success, he argued, stemmed predominantly from her experiences as a Somali refugee. And Omar is not alone, continued Lowndes, Somali workers had organized at plants and factories throughout the Twin Cities metropolitan region to push for change in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. “Here,” Lowndes concluded, “the autonomous, unapologetic movements of the marginalized are pointing new ways forward toward an egalitarian and democratic future.”

Now, over eight months later in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests stemming from George Floyd���s death in police custody, and as COVID-19 cases in the US steadily climb upwards, Ilhan Omar and the Somali-American population in the Twin Cities continue to stand at the forefront of change in Minnesota and the United States more broadly. Although many would fail to link the situation in the Twin Cities with what some have called “Africa’s most failed state,” Omar Jamal, in an interview for the New York Times, highlighted the similarities between his experience as a black man in Minnesota and as a Somali refugee: “I couldn’t distinguish between being in Somalia and being in St. Paul.”

Minnesota is home to more than 75,000 Somalis who began immigrating to the United States en masse in the early 1990s following the outbreak of civil war. Although many asylum seekers initially resettled in other parts of the country, the job opportunities for unskilled workers near the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul attracted increasing numbers of resettled East African immigrants. At workplaces like the Pilgrim���s Pride chicken processing facility in Cold Springs, the Amazon fulfillment center in Shakopee, the JBS pork processing plant in Worthington, and the Jenny-O Turkey plant in Melrose, East African workers comprise large percentages of the workforce. This initial connection to the North Star state via industrial workplaces embedded a deep connection between community and political organizing, one that continues to place Somalis squarely at the center of social transformation in the Midwest.

East African immigrant workers have stood at the center of protests against unfair labor practices at the same factories that drew many to the region. Most notably, many of these workers have faced off against Amazon, the global capitalist behemoth that opened a fulfillment center in Shakopee, MN, in July 2016. As the New York Times and WIRED magazine would report in features on how these workers mobilized, Amazon recruiters focused their efforts on the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis; a community often referred to as “Little Mogadishu.” Although Amazon officials initially offered major incentives for immigrants to come work at the Shakopee facility, including free bus service and manageable work expectations, it wasn’t long before workers at the center began reporting discrimination, religious intolerance, and inhumane working conditions. In particular, the lack of accommodations for the Muslim workforce’s daily prayers and concessions for Ramadan began to strain relations between the Somali workers and the corporation. The cancellation of the free shuttle service to the facility further aggravated relations between the corporation and its workers; in this climate, the Minneapolis-based Awood Center (Awood means “power” in Somali) under the leadership of co-founder Nimo Omar and executive director Abdirahman Muse began organizing the East African workers at MSP1 to push for more concessions from Amazon.

In early fall 2018, after months of small-scale protests and airing of grievances, workers had two private meetings with representatives from Amazon, marking what many labor experts insist is the first instance of workers bringing Amazon to the bargaining table. In the wake of this massive accomplishment, conditions at MSP1 continued to deteriorate and organizers decided to make a bigger statement. On December 14, 2018, less than a week before Christmas, workers at MSP1 walked out in the midst of the pre-holiday rush, marking the first coordinated strike at an Amazon facility in North America.

Although these movements brought increased attention to the struggle of Somali workers at the facility, Amazon has found ways to punish those workers, with workers reporting fewer full-time hires and reporting harassment from management. In July 2019, the Awood Center organized a Prime Day rally but it was minimally attended. So what have these protests accomplished? They have brought attention to the unfair labor practices at Amazon, the struggles of unskilled workers in the United States, and no doubt contributed to a congressional call to investigate Amazon for workplace abuse. Perhaps more than anything, however, these protests have put a face to a largely invisible struggle. Khadra Ibrahin, a single mother of two who stood at the forefront of the 2019 protests against the media giant, pleaded for customers to think about the people behind their digital orders in a 2019 interview with Chavie Lieber for Vox: ���I wish for customers to know that behind every Amazon order is a human being, and we deserve to be treated fairly.���

The struggle for fair treatment is one that Somali immigrants and Somali Americans living in the Twin Cities have publicly embraced. They have been prominently active in Black Lives Matter protests since the deaths of Minneapolis locals Jamar Clark in 2015, Philando Castile in 2016, Thurman Blevins in 2018, and Shirwa Hassan Jibril in 2019. Their presence in the protests against police brutality has taken many forms, from demonstrating in the streets to volunteering in food banks and participating in cleans ups in the aftermath of the protests. The death of George Floyd in South Minneapolis on May 25, 2020 hit particularly close to home for the Somali community, as this area is home to the largest Somali malls and mosques in the state in addition to the Somali Museum of Minnesota. Although older Somali immigrants report a lack of connection with the Black Lives Matter protests, the deaths of black men at the hands of police have radicalized young Somali immigrants and Somali-Americans who reject the divisions between themselves and their African American brothers and sisters. In an interview with Ibrahim Hirsi for MPR News, 22-year old Abdihakim Abdi rejected the separation between his identity as a Somali-American and his status as a black man in the US: ���When it comes to the cops, we���re all the same thing.���

In addition to the ongoing struggle against police brutality, black Minnesotans face disproportionate exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nationwide, it is well-established that COVID-19 disproportionately affects people of color, laying bare structural inequalities often veiled by nationalist rhetoric. In the Twin Cities metropolitan area, these racial disparities are most clearly exhibited in the skyrocketing infection rates at the same factories staffed in large part by Somali immigrants and Somali-Americans. At the MSP1 facility, an internal memo recently revealed that Amazon officials were aware of at least 45 COVID-19 cases, making the infection rate at the facility 1.7% (four times higher than any county in the Twin Cities metropolitan area, according to Matt Day reporting for Bloomberg). Similarly, at the Pilgrim���s Pride factory in Cold Spring, where 80% of the workforce is Somali, workers staged a walkout over safety concerns following revelations that over 200 at the facility have tested positive for COVID-19, demanding accountability from the corporation and the implementation of more stringent safety measures. Nimo Ibrahim, a chicken deboner at the plant who tested positive for COVID-19, expressed her fears of losing her job due to being quarantined: “Keeping the job is a priority. This is the only thing that I know and have been doing for a long time.”

At the center of these interconnected struggles stands Ilhan Omar, who Africa Is a Country founder and editor Sean Jacobs insists is the most exciting African politician right now. This claim is difficult to argue with as Omar pushes for change while also standing firm against Trump’s consistent, blatant harassment. In 2018, Omar became the first Somali-American legislator in the US, standing as a symbol of hope for her community in the Twin Cities and as a true American success story. Born in Mogadishu in 1982, Omar came to the US in the early 1990s with her widowed father and her sister Noor, eventually settling in Minnesota. Omar���s background, combined with her experience in community organizing and local Twin Cities politics, makes her a key actor in the turbulent times that she is seeing her constituents through.

At the MSP1 protests in 2018, Omar stood with the Awood Center and the Amazon workers, connecting her own labor history to their struggle. Breaking from leading the crowd in a rendition of the Somali solidarity anthem “Aan Isweheshano Walaalayaal,” Omar spoke about her own experiences with working in the US: ���I���ve had many jobs. I clean officers. I worked on assembly lines, I was even a security guard once. I���ve had jobs where we did not have enough breaks, where we used to try to go to the bathroom just so that we could pray. Amazon doesn���t work if you don���t work. It���s about time we make Amazon understand that.���

Early last month, at a memorial for George Floyd, Ilhan Omar spoke to the crowd about the frustration that black Twin Cities-residents felt at this historical moment. “This is one of the liberal havens, where in every single measure of society, everyone has the best life except for blacks and minorities,” Omar cried out. “When it comes to social and economic success in this state and in this city, we are at the bottom of every single measure ��� what we want is the ability to not just breathe, but to live and thrive.” The next day, Omar introduced a package of bills in collaboration with Ayanna Pressley and Sheila Jackson Lee to address police brutality on a national level, putting real political leverage to work in response to the struggles of her constituents. Less than two weeks later, Omar announced the death of her father, Nur Omar Mohamed, from COVID-19 complications. Omar sees no dividing lines between her own experiences and the struggles of her constituents; this personal connection drives her politics and her plans for social transformation in Minnesota and beyond.

In a June 29, 2020 opinion piece penned for the Star Tribune, Omar laid out a plan for how Minnesota could lead the way towards social transformation. She asked the readers: ���Will we have the moral courage to pursue justice and secure meaningful change or will we maintain the status quo?��� This is a question that all Americans should ask themselves at this historic moment. Will we display the same moral courage that Somali workers in factories throughout Minnesota have shown as they face off against corporate giants? Will we fight against the status quo as Ilhan Omar has done, first in her historic congressional run and now as she pushes for systemic changes to expose and address structural inequalities in this country? Somali immigrants and Somali-Americans have had to organize in order to find community, support, and justice in a country that, more often than not, sees them as a burden and, increasingly, as threats. On American “Independence Day,” we should all stop to think about what independence means and how we can move forward towards a truly democratic future. The challenges facing us at this historical moment require organization and determination; let’s hope that many take the cases described here as an example to follow.

Feminism, religion and culture in Senegal

Two women walk to prayer at the mosque in Touba, built in honor of Cheickh Amadou B��mba, founder of the Mourid brotherhood. Image credit Jay Galbraith via Flickr CC.

Following yet another TV show in Senegal which featured intolerable misogynous and sexist content, I had a conversation with two impassioned feminists, Maimouna Thior, a France-based doctoral researcher on gender and religion in Senegal, and Adama Pouye, a communications student. We decided to focus on gender norms and values and their intersection with discourse on religion and modernity, as well as Maimouna���s and Adama���s views on what it means to be young women and feminists in Senegal and its diaspora today.

Rama Salla Dieng

Hello Maimouna and Adama, it’s a pleasure to have recently discussed with you about Senegalese current events. Could you please introduce yourselves?

Maimouna Thior

Hello Rama, thank you for giving us this opportunity to debate these issues. My name is Maimouna Eliane Thior, and I am 26 years old. I am in my second year of doctoral studies in sociology, working on the political and socio-religious history of Senegalese women and their relationship to globalization: between Western feminism and Islamic feminism. I am interested in the evolution and/or the change of the identity of Senegalese women shared between Islamic tradition and the influences and legacies of Western culture accentuated by globalization and modernity through social media.

Adama Pouye

Hello Rama, it’s a pleasure to meet you. My name is Adama Pouye, and I am 23 years old. I am an MA student in communications and a librarian by training. I started to get really involved in feminist issues recently. I am currently working, as part of my master’s thesis, on the place of the female body in advertising.

Rama Salla Dieng

What is your definition of feminism? And what influences and inspires your feminism?

Maimouna Thior

My definition of feminism is very simple. I will borrow Mariama B�����s answer in So Long a Letter: ���If defending the interests of women is to be feminist, then, yes, I am a feminist.��� I am inspired by African American women, who suffer all forms of discrimination that may exist. Beyond the discrimination due to the social relations that every woman in the world suffers, African American women are confronted with discrimination related to race, religion, capitalism, etc. I also see African immigrant women suffering these same injustices��� I very often use the ���intersectionality��� framework, which in sociology is a notion of political reflection developed by an American academic (Kimberl�� Crenshaw) to evoke the situation of people simultaneously undergoing several forms of discrimination. This concept allows me to analyze the different oppressions that Senegalese women face at a local level, but also to situate them in the global hierarchy in terms of race.

Adama Pouye

For me, feminism is a demand for women’s rights, an aspiration towards equity. Equity instead of equality to be more precise, equity will mean that in all areas we will see women beyond their gender, nothing will be based on sex. Feminism is a denunciation to move towards a more just and humanistic society. One of my great influences is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie with her ���happy feminism��� [in which] she mentioned ���We are all feminists.���

Rama Salla Dieng

Every month, we notice sexist scandals on Senegalese TV shows. We all remember the Songu�� scandal���a prominent high school teacher saying on TV that female students make men rape them, without suffering any consequences while the rapists go to jail���and recently the Sen TV talk show, which also featured intolerable misogynous comments. How do you read these events?

Maimouna Thior

I think that these TV programs reflect the reality of our society. These shocking utterances actually reflect what most of us believe. It shocks us because it���s on TV and we are able to put faces to these words. You have to watch these programs to know how people think in order to raise awareness and find solutions to change certain beliefs. The last talk show on Sen TV revealed that there are different categories of women in our society: those who defend polygamy, those who want a possessive and demanding husband, those who prefer to not work and to serve their husband exclusively, those who seek higher degrees, the radical feminists… not to mention the men who cling to their power. This should remind us that for feminists there is still a lot of work to be done in occupying the public space, the media and even impacting the national education system. We can���t give up and retreat; we must carry on the work begun by our feminist elders who have enabled us to go to school on a massive scale. Now that we have all been to school in large numbers, the challenge would be to make the next generation more autonomous and freer in their life choices.

Adama Pouye

These many outrageous debates in the media are, in fact, driven by the demand from the audience. The more shocking these TV programs are, the more viewership they attract. Also, these offensive discussions on women are not limited to the broadcast media. Last December, L’Observateur, one of the most widely circulated newspapers in Senegal, had on its front page: ���Object of all desires: the iPhone makes Senegalese women lose their minds. They are ready to sell their body for an iPhone.��� Some young people protested here and there on Twitter, but that was it. The authors almost always come out of these scandals unscathed. Returning to the Sen TV talk show, there were women on the set who even seemed to encourage these statements, one of the women openly said ���dama b��gg goor bu tang��� (I like men with a bad temper); certain abuses suffered by some women are normalized and even appreciated. Five women were there and none of them reacted to a man comparing women to dogs. I denounced these statements on my Twitter account and on WhatsApp. Most of the reactions were like, ���They only meant it figuratively.��� Our society itself has associated women with acceptance and silence, and women have accepted this in the most natural way.

Rama Salla Dieng

Are these statements merely a reflection of Senegalese society? Do you think they are due to the ambivalence of our society straddling Islamic and Western cultures? Should we speak of one patriarchy or many sets of patriarchies?

Maimouna Thior

As I said earlier, these comments are not that outside of the mainstream, the people who expressed these views on TV merely shared their opinions on subjects related to our social relations. Indeed, Senegal is divided between its Islamic and Western [colonial] heritage. These comments are very often shocking because when debating women���s issues, we often refer to our religious texts to lock in the debate. A large number of the Senegalese people grew up with this religion-based rhetoric and ended up believing that there were no alternative debates outside of the confinement of the religion. But I believe that religious texts are subject to different interpretations depending on culture, time, context, etc. There are also those Senegalese who are fundamentally attached to the traditional practices and views, who can make amalgams between traditions and the precepts of Islam. They do not believe in any evolution of culture in the name of modernity or globalization. In the same way, they retain a rigid interpretation of a religious verse which, however, derived from a specific context or situation. In such cases, the cocktail of our African traditions and Islamic culture can be explosive.

In terms of Western influences, many Senegalese are allergic to modern concepts such as feminism. It is seen as a pervasive tool that seeks to destroy the Senegalese ecosystem. Dakar can exist apace with Paris in terms of fashion, current events, way of speaking, eating in a nuclear family, but retracts when it comes to emancipating or empowering women. Although the power of women in professional spheres may be well regarded, the phobia lies mainly in the repercussions at the household level or the distribution of domestic roles.

Adama Pouye

Indeed, as Maimouna said, these discussions reflect the Senegalese reality. The conditions of existence for the majority of Senegalese women remain precarious, despite the fact that the women themselves may think otherwise. Many anti-feminists use religion as a basis for rejecting the place that women should occupy in social, professional and religious life. Islam is interpreted to assert the dominant position of men, to satisfy the desires of an irresponsible husband���who refers to religion to justify his wrongdoings, to maintain his privileges that are not based on any merit. Yet, Islam can be viewed as one of the most feminist religions, wherein women occupy a central place. Some may think that women should not hold high positions of responsibility or lead men, but the Prophet Muhammad was employed by Khadijah, whom he later married. She was a very successful merchant at the time, and therefore an entrepreneur or businesswoman in her own right, and she is the model woman in Islam. See the contradiction with what preachers want us to believe.

Some sources, particularly the sociologist of religions, Bryan Turner, tell us that in some pre-Islamic Arab tribes there were practices of infanticide of girls and that the status of women was mediocre. It has been reported that Ibn Abbas, one of the companions of the Prophet (PBUH), spoke of it: ���If you want to discover the ignorance of the Arabs (before Islam), read the verse of the Quranic chapter El An���am: ���Those will have lost who killed their children in foolishness without knowledge and prohibited what Allah had provided for them, inventing untruth about Allah. They have gone astray and were not [rightly] guided��� (Qur���an 6:140). Islam has made it possible to abolish such practices and to value women. Islamic culture cannot therefore be the reason for such a great misunderstanding of gender relations in the discourse of some Senegalese.

We must therefore look for the reasons for the subjugation of women on the side of Senegalese traditions and the values it inculcates. Kocc Barma, cited as a reference in the field of Senegalese traditional wisdom, said ���Jigeen sopal te bul woolu��� (Love your woman, but never trust her). The poet Oumar Sall, recently showed that this could be a distortion, and the correct saying is rather: “Jigeen soppal, du la woolu” (love your woman, who, by the way, will never trust you). Other expressions like these are repeated all day long to men and to women���such as the famous ���jigeen moytul��� (with women, stay alert) or ���jigeen day mugn ngir am njabott bu baax��� (a women must accept hardships in order to have successful children), or when the child misbehaves, ���doom ja, ndey ja��� (the child is a reflection of the mother). All these misogynous messages are conveyed in learning how to become an adult, at various stages in life, and especially in the allocation of household tasks; they all create a subconscious that cannot conceive of a certain equality in law and dignity between women and men. It is an implicit, subtle message that Senegalese people pass from generation to generation without necessarily realizing it.

Rama Salla Dieng

In Senegal, what are the most established stereotypes associated with feminists (angry, sexually frustrated, anti-men)? What explains them? Do you think they are due to the supposed incompatibility between African or Senegalese culture with feminism?

Maimouna Thior

I think they���re trying to rehash a clich�� that comes from elsewhere. The first European feminists were called hysterical. Today they are accused of thinking too much because feminism has become an intellectual discipline that is accepted at the university level. In a society where marriage determines the value of women, I do not see how Senegalese women can be viewed as anti-men. In a society where sex education (even from a religious point of view) is taboo, where the erotic aspect of the couple���s life is reserved only for women, I don’t think those women actually know enough to realize whether they are well laid or not. Senegalese people need a specific definition of feminism that applies to our context. This is very normal because there are as many feminisms as there are countries. Feminism adapts to the needs and specificities of each society. If the Senegalese people need to be convinced that our feminism is not copying the Western model, then Senegalese feminists must be the ones making that case. It is very often said that African women have always been feminists in practice, where Europeans have had freedom of ���speaking��� their feminism. We then have a basis on which to add modern notions that reflect the realities of our times.

Adama Pouye

It is important to know that in the Senegalese popular mindset, the essence of the woman derives from her rapport with men. For them, a fulfilled woman is above all one that it married and has children. From this perspective, a happy woman does not need to complain and adopt feminist concepts that are ���imported��� from the west. The work of contemporary Senegalese feminists will have to focus on deconstructing that mindset. Feminism is broad and involves several struggles. It is up to us to contextualize each of our demands, so that the feminist issues we raise are ours, in line with our society and expressed in a language that speaks to fellow Senegalese. In this way, I think that as time goes by, the general public will find their way around and these clich��s will gradually disappear. We must persist.

Rama Salla Dieng

A word on gender-based violence?

Maimouna Thior

Gender-based violence is increasingly being denounced, and people are speaking out thanks to social media and the mechanisms put in place by men and women to eradicate this scourge. However, it is also a matter of informing and educating women so that they know their legal rights for their own well-being, but also for their children. Many women are reluctant to leave their oppressive marriages, because of lack of means, they do not know whether they should receive alimony or not. It is encouraging to see that there is a growing awareness in this area because physical and sexual violence against women is an attack on their dignity, safety and autonomy.

Adama Pouye

News about gender-based violence is recurrent in the press, and in everyday stories. The work that needs to be done is, above all, to make people understand the limits of the ���muu����� (patience) and the ���sutura��� (silence) that keep some women in the households where they are victims. Violence is not only physical, it can be also verbal and just as destructive as the former. Every woman must be aware that it is an offense to her dignity that must be denounced; that the fear of ���xawi sa sutura��� or ���I can’t afford it��� is an obstacle to bringing the perpetrator to justice. Women���s associations must think about how to support these women, in terms of housing, vocational training or social, moral and psychological support.

Rama Salla Dieng

In your opinion, how can we change the patriarchal discourse, norms and values, and realities?

Maimouna Thior

Raise awareness, communicate, debate. These are the key words for a social paradigm shift. A culture is not fixed, but an abrupt change could offend. We have a lot of good values to preserve and share with the rest of the world, which should not prevent us from opening up to others to enrich ourselves and evolve in time and space.

Adama Pouye

I would also say that we have to go back to the roots, change our education system. It���s important to understand what patriarchy and feminism is. In the home, balancing each other���s rights and teaching both women and men household chores. It is also important to abandon or rephrase all the sexist proverbs in the Wolof dictionary and to have knowledgeable women interpret the Quran. Schools should also have courses through which messages of gender equality are conveyed.

Rama Salla Dieng

What is the role and place of male hegemony, accepted and magnified by women, and of capitalism in this social critique of Senegalese society?

Maimouna Thior

I very often say that patriarchy is a system perpetuated by men and women against all women. It is women who maintain patriarchy in a conscious and/or unconscious way, and they convey over many generations practices that undermine the moral and physical integrity of women. Even Senegalese men are victims of this system, because they are raised by mothers who treat them as kings who are not required to participate in any domestic tasks, among other things. The few men who do domestic chores for instance are seen as emasculated or ���toubabs,��� while some of them think that they are doing a ���favor��� to their wife when it is their shared household, and their shared children if they have any. This male supremacy is at the root of all our struggles, but I think that men are just as ready to fight against us to preserve their privileges.

Adama Pouye

I agree with Maimouna. That���s exactly what all this criticism is based on.

Rama Salla Dieng

Why do you think it is taboo to talk about sex and female pleasure among younger Senegalese women?

Maimouna Thior

Hmmm, personally I don���t see that it is taboo to talk about sex. In fact, I have the impression that sexuality is all we talk about in social media. Girls thinking of marriage have good plans related to intimacy. If in the past, girls were seriously prepared to face marriage according to the rules of their ethnic group or family, today they share ���feem��� or tricks to keep their man. This is my impression.

Adama Pouye

All that Maimouna said, in addition to the fear of being accused of being ���caga,��� of being a slut. The fear that what a young woman says about her sexuality could be reported to her parents, making them aware of the young woman���s active sexual life, in a society that values chastity. The debate about sexuality is confined to married women.

Rama Salla Dieng

How, in your opinion, has the COVID-19 pandemic increased gender inequalities in Senegal where you live, Adama? And in France where you live, Maimouna?

Maimouna Thior

In France, I noticed that those deemed ���essential workers��� tended to be women, black women or women of color. I noticed them in the supermarkets, the two women janitors in my building did not get to stay home, and a young student of Senegalese origin kept working at the gas station. There is also a spike in domestic violence, which has increased because of the stay-at-home orders. Toll numbers have been made available to denounce one���s spouse in case of domestic violence, or if one���s neighbor is in danger. Personally, I will not hesitate to call if necessary because there is no justification for any form of gender-based violence.

Adama Pouye

Women are already at high risk of this disease. The majority of health workers are women (53% of the total workforce, according to a 2015 study), so they are at the front lines and exposed to the virus. In households, it is also women who are often in charge of grocery shopping, who take care of domestic tasks, and are vulnerable to the disease. In a recent article, Dr. Selly Ba talks about the ���feminization of poverty.��� She argues that ���the COVID-19 may further reinforce the feminization of poverty which in turn may limit women’s participation in the labor market and [increase] inequality in access to ��� resources.��� In addition, domestic violence is exacerbated by the fact that household members are confined at home.

Rama Salla Dieng

What is your self-care routine?

Maimouna Thior

My first source of well-being is to communicate regularly with my relatives in Senegal. Constantly talking to my parents makes me feel good. They support all my projects and know all my activities. The simple fact of knowing that I can count on them despite my adult age is comforting.

I’m also passionate about vintage images and videos, I love everything that is images, films, old school music related to Senegal. I spend time collecting these beautiful archives.

Reading and writing are also therapeutic for the learner that I am. I wipe my tears with writing, because I often cry when I���m depressed by the loneliness, the gloom, the dull of France.

I also like fashion; I really care about my dressing style because it���s part of my identity. As soon as the weather warms up, I put on my Senegalese outfits. Knowing that I���m doing things, such as dressing up in my Senegalese clothes, makes me feel closer to home. And that does me a lot of good. I���m a Senegalese at heart, after several years in France, I still feel like I left my soul in Dakar, and that it only reconnects with my physical body when I���m back in Dakar. Basically, my life only makes sense in Senegal.

Adama Pouye

I don���t really have any, I���m a day-to-day person. My Monday routine can be different from Tuesday and any other day of the week. I follow my desires when I wake up, but I can say that a good night���s sleep, a good hot shower, and a perfect outfit make me feel the happiest!

My little pleasures revolve around reading, photos, fashion and conversations with my loved ones.

July 2, 2020

The battle within

Uhuru Kenyatta (left) and William Ruto (right) in better days. Image via the Anglican Archives on Flickr CC.

Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto are president and deputy president of Kenya respectively since 2013. They started their political careers in separate political parties, but were brought together by the cases around the 2007-2008 election violence that ended with them being charged at the International Criminal Court at the Hague. Now the formerly same-tie-wearing pseudo anti-imperialism-fueled bromance between the two appears to be on its death-bed. This, according to Dauti Kahura, has all the hallmarks of betrayal, brinkmanship, deception, fraud and subterfuge.

This post is from our partnership between the Kenyan website The Elephant and Africa Is a Country. We will be publishing a post from their site regularly, curated by our Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

��� VoltaireLord, protect me from my friends; I can take care of my enemies.

The above quote is one that Deputy President William Ruto could well be spending lots of time brooding over, especially in these times of coronavirus. Since official recognition of the pandemic���s arrival in Kenya over just three months ago, Ruto���s political battles���not with his enemies, but with people he had counted as friends���have intensified. The battles that are being fought in the Jubilee Party, the party of President Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta, are internal and among erstwhile friends.

Coming barely 30 months after the forceful UhuRuto duo won a controversial fresh presidential election on October 26, 2017, the two political brothers looked set to finish their second term the way they started the first: as a formidable team of like-minded captains, with the lead captain passing the baton to his comrade once his term expires. But that today is a dream: the waters have been poisoned and the former buddies are no longer swimming in the same direction, leave alone swimming in the same waters. The breakdown of the alliance has all the hallmarks of betrayal, brinkmanship, deception, fraud, and subterfuge.

Jubilee Party mandarins did not see the break-up coming; if they did, they all pretended they were not aware of the imploding scenario. The ruling party is now a house of two diametrically opposed camps led by their respective protagonists: President Uhuru Kenyatta, who coalesces around the Kieleweke (it shall soon be evident) camp and William Ruto, who is spearheading the Tanga Tanga (roaming) team.

���We can no longer pretend that the current war being waged against William Ruto is not from within and therefore not from friends, or people he had presumed were his political friends,��� said a Ruto confidante I spoke to. ���To think otherwise now would, like the proverbial ostrich, be burying our heads in the sand. It is better to be fought by your enemies, who you have fought several times before and therefore you already know to deal with them, rather than be fought by friends, who have turned the tables against you, all the while posing as your compatriots.���

���Uhuru is employing political terrorism against his number two and to be honest, it is something we had not anticipated,��� said Ruto���s friend of many years. ���Yes, it has taken us by surprise, the intensity and all, but we must stay and fight back, even as we devise a strategy to stem the political bloodbath. It is all about the politics of succession in 2022 and there is no hiding the fact that Ruto obviously wants the seat. If you have been a deputy president for seven years, what else would you want as a politician in that position? It is also true that once Uhuru and Ruto were sworn in for the second and final term, we started popularizing our candidate immediately���it was the natural thing to do���hitting the ground running. This was misconstrued to be a campaign, but even if it were, we weren���t doing anything outside of the constitution.���

The coronavirus appeared just in time to help President Uhuru fight his political battles, reasoned the DP���s bosom buddy. ���He is now using the pandemic to wage war against his deputy. The semi-lockdown and the curfew are strictly not about COVID-19, but about clamping down on Ruto���s forces in the party and in government.���

���Uhuru is maximizing on the COVID-19 pandemic as much as possible because he knows his antagonist, the DP, cannot organize and mobilize for his counter-attack, which he is good at. The people have been locked down, they are restricted, they cannot move, they are scared and are caught up with survival. President Uhuru can therefore wreak havoc in Ruto���s camp with as little distraction as possible,��� he added.

But unlike the last election, the president does not have the unflinching support of his own people. ���Uhuru���s biggest problem is that the Kikuyus have turned their back on him,��� said a friend of Uhuru who also counts Ruto as his friend. ���He thought he owned them and he could do whatever he wanted with them. He also thought they would always go back to him and do his bidding. Now, they seem dead set in ignoring him completely and the fact of the matter is, as a political leader, you can do little if you cannot galvanize the support of your people. You cannot claim legitimacy, you can only impose yourself on them and that is always counter-productive.���

Because of this, said the Jubilee Party mandarin, President Uhuru���s current headache is how to de-Rutoise central Kenya and the larger Mt Kenya region. ���He���s been trying to tell the Kikuyus that Ruto has been disloyal to him, that he wants to grab their power, that he���s not fit to ascend to the presidential seat because he���s corrupt and power hungry. But they have refused to listen to him. With each passing day, he���s getting furious with the Kikuyus��� recalcitrant stand against him. Now, he has turned to appointing Kikuyus in prominent positions, including the recent reshuffles in Parliament to appease his Kikuyu base.���

The duo���s friend told me that President Uhuru���s allegations about his deputy���s insubordination was a red herring. ���What disloyalty is Uhuru is talking about? When he was busy drinking, we held fort by taking care of government business, even as we covered his social vices. Now he has the temerity to talk about disloyalty. We���re not afraid of him. The Jubilee Party/Kanu coalition agreement is illegal as per our Jubilee Party constitution and it was cobbled up to stop Ruto from vying for the presidency.���

All the president���s men

To fight Ruto, President Uhuru Kenyatta formed an advisory team that meets at State House. Part of the team comprises David Murathe, Kinuthia Mbugua, Mutahi Ngunyi, and Nancy Gitau.

Murathe has for the longest time been President Uhuru���s sidekick. His father, William Gatuhi Murathe, was one of the wealthiest Kikuyus, courtesy of Uhuru���s father and the country���s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, During Jomo���s time, the senior Murathe was the sole distributor of wines and spirits countrywide.

The Tanga Tanga team describes Murathe as ���Uhuru���s attack dog���. They believe that when Uhuru wants to communicate an important message, he uses Murathe. And they���ve learned to decipher his messages.

Kinuthia Mbugua is the State House Comptroller; he keeps President Uhuru���s diary. He served as Nakuru County governor for one term. Eagerly looking to serve for a second term, he nonetheless lost the Jubilee Party nomination to Lee Kinyanjui. He was furious, and even looked to run as an independent, but was persuaded by Uhuru to join the presidential campaign team, with a promise of a bountiful reward once the campaign was over.

Mbugua to date believes William Ruto rigged him out of a nomination when he was left to man the Jubilee Party headquarters at Pangani during the chaotic and hectic nominations. He carries the grudge like an ace up his sleeve.

Mutahi Ngunyi is a private citizen who has immersed himself in state (house) politics and has distinguished himself as a maverick, a person who can swing like a pendulum and still remain standing, without falling. In the lead-up to the 2017 election, he made Raila Odinga, the opposition coalition leader of the National Super Alliance (NASA), his punching bag, terming him a ���punctured politician���, an epithet that his detractors used to describe Raila���s father Jaramogi Oginga Odinga in the 1970s.

After Uhuru and Ruto romped back to State House, Mutahi quickly (perhaps too quickly) identified with Ruto���s camp and decreed that Ruto will be the next president come 2022. A crafty mythmaker, he even came up with the Hustler vs Dynasty narrative to define the rivalry between Ruto and the sons of prominent Kenyan leaders, including Uhuru Kenyatta, Raila Odinga, and Gideon Moi. He wildly claimed in a May 2019 tweet that the only person who could liberate Kikuyus was Ruto. (Mutahi has since deleted all his tweets that were singing Ruto���s praises.) Then, beginning this year, Mutahi flipped, disavowed his hustler narrative and claimed that Uhuru Kenyatta was ordained to rule Kenya.

Nancy Gitau has been the resident State House adviser from the time of Mwai Kibaki. Before becoming a state aficionado, she worked for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). While at USAID in the 1990s, she was involved in the democracy and governance sector, which was being heavily funded by the United States and other donors. The last big project that she oversaw was a partnership between Kenya���s Parliament and the State University of New York (SUNY, Albany)���s Centre for International Development (CID), which Sam Mwale and Fred Matiang�� managed. Both Mwale and Matiang�� would later become civil servant bureaucrats, serving as Permanent Secretary and Cabinet Secretary, respectively.

Gitau was very well-known within the civil society and the NGO sector and interacted with many of them. ���Gitau was one of the architects of a report implicating Ruto in the post-election violence and so there is no love lost between her and Ruto,��� said Ruto���s aide. The deputy president is still upset about Gitau singling him out.

Expunging Ruto���s men

The Gitau-led advisory team ostensibly meets every Sunday morning at State House and during weekdays at La Mada Hotel located in the New Muthaiga residential area in Nairobi.

One of the team���s main jobs is the expunging of Ruto���s men in the Senate, with Kithure Kindiki, the Senator of Tharaka Nithi County, being the latest casualty. Until 22 May 2020, Kindiki was the Senate���s Deputy Speaker. The first two casualties were Kipchumba Murkomen and Susan Kihika, the former Majority Leader and Chief Whip, respectively ���The two were removed because the president and his men didn���t have the majority in the Jubilee Party���s National Executive Committee (NEC),��� said a ���renegade��� senator, who accused President Uhuru of ���using strong-arm tactics to coerce senators to vote according to his whims.���

Senators were allegedly paid Sh2 million to vote to remove Murkomen and Kihika. ���On the day the senators were summoned to State House, President Uhuru didn���t have enough senators to push his motion,��� said the senator. ���The Jubilee Party had only 11 senators, Kanu, three and one independently-elected senator, Charles Kibiru. If you count Raphael Tuju and President Uhuru they made 17 votes. Tuju is the secretary general of Jubilee Party. So, they were way short of the required majority of 20 votes.��� The senator claimed that the president had to send helicopters to pick senators from their far-flung regions.

���Uhuru can send choppers to senators who are supposed to be in lockdown and in quarantine, but he will not send planes to rescue and send food to flood victims. That���s how much he cares for the unity of this nation,��� complained the senator.

I asked a Ruto confidante why his boss had gone quiet. Was the heat becoming unbearable? ���This is not the time to speak. We actually advised him not to open his mouth. There���s a time that he will speak, but not now.��� The confidante also reminded me of another saying: “The man who speaks little makes mistakes, but what about the man who talks a lot? He makes big mistakes.”

Buddha in Africa

Still from film Buddha in Africa.

When he was orphaned at age four, Enock Bello was taken into a Chinese owned and run orphanage in Malawi. The difference between this orphanage and many others in Malawi is that the children are expected to learn Chinese, Buddhism, and martial arts. Essentially, they are being trained as young Chinese people even though they are Malawians. This conflict is the center of the narrative tension in the film, Buddha in Africa.

Buddha in Africa takes us on a journey with Enock from childhood to the day it is time to go to college. Along the way, Enoch finds himself lost between two cultures with no real peace in either. His family is from Mangochi, Malawi, where the Yao people are from. The Yao are predominantly Muslim and their language is known as Chi-Yao. Most Malawians are Christians who speak Chi-Chewa. Enock is surrounded by Chi-Chewa speakers in the orphanage and learns Chi-Chewa but cannot speak Chi-Yao. This results from the inability to leave his orphanage and visit Mangochi, where his people are from, once a year for two weeks.

My father was also a Yao so I know how different their culture in Mangochi is from the rest of Malawi. It is a bit of a world apart. All of life there tends to revolve around farming and happens at a slow pace. The filmmaker does a brilliant job of capturing the nuances of village life. It is slow, family oriented and completely revolves around farming mostly for chimanga (corn) to make nsima, which is a porridge made stiff enough to eat as a sort of soft bread.

This story, like many others before it, is the story of what happens when two cultures collide. The native culture is being replaced by a culture from a faraway land because things have fallen apart in Malawi, in many of the ways they did in Chinua Achebe���s Umuofia. The difference is that the encroaching culture is now Chinese instead of British (the former colonizers). Orphans anywhere are forced to learn the language of a colonizer and survive by their proximity to the culture of the foreigner. Religion is one of the many ways a colonizer puts their stamp on new lands.

The cinematography and filming are of an incredibly high caliber. The camera���s eye follows Enock as he travels to his village, to New York City and to Hong Kong. Every place that Enock goes is documented in vivid colors, both up close and from wide angles. He travels to many places as a representative of the orphanage, performing incredibly tough martial arts moves as part of a fundraising scheme. Although he is fascinated by the world, he never really gets to spend much time in his own culture. He also seems to move from place to place working to raise funds for the orphanage but never really getting to stay long enough to really experience any of the places he performs in.

In an article for Hot Docs, the film���s director Nicole Schafer, a white South African woman, says, ���The film sets up its key debate through the internal conflict of the protagonist. Enock���s internal conflict of trying to hold onto his own culture on the one hand and the sacrifices that come with embracing the opportunities afforded by the Chinese culture on the other reflects the greater dilemma around African development within a globalized context���not only in its relation to China, but to other foreign nations, including its former colonizers.��� Throughout the film you sense Schafer is dubious of the relationship between Malawi and China and how it will go for African children caught in the middle. This raises important questions.

However, we are forced to wonder if a documentary of this caliber would ever be funded if a Malawian sought to make it. It raises important questions about the colonial situation in Malawi but reiterates the idea that those who were colonized often have their stories told by outsiders, which continues the colonial relationship in another way. Should you see this documentary? Absolutely. Good work is good work. At the beginning of the film, Enock wants to be a filmmaker but by the end, his dreams have changed. We are left wondering if the protagonist will ever find his way to the other side of the camera to be the real owner of his story.

However, the reason this sort of film can���t be made by a black Malawian filmmaker is tied to Malawi���s own colonial relationship with South Africa. Kamuzu Banda, who was Malawi���s dictator for 30 years, was the only African leader to support the apartheid regime in South Africa. He hid much of the money he accumulated from supporting the West and apartheid in banks in Europe. None of it was returned to the people of Malawi when he was removed from power in 1994.

So, today as Malawi is being colonized by China, it is logical that the person shooting it all is a white South African. She is from a country that moved ahead economically between 1948-1994 while playing a large role in keeping Malawi from developing. During apartheid, men from Mangochi were forced to seek labor in the mines of South Africa. This system destroyed the possibilities for development in Mangochi and destroyed families that were left fatherless by the constant migration of able-bodied men. In this film, you see no adult men in Enoch���s village. That problem started with the help of apartheid South Africa. This is not the filmmaker���s fault but it is the nature of the history of the region. The filmmaker has given us a wide lens in which to see China���s current strategy. I only ask that you open the lens a little wider and see how one colonial hand opens the door for another to stand back holding the camera, as the cycle continues.

July 1, 2020

Lumumba���s iconography in the arts

Sam-Ilus, "Les p��res de la d��mocratie et de l'ind��pendance," 2012. Courtesy: Philip Buyck, Lumumba Library. Photography: Matthias De Groof

Patrice Emery Lumumba���s career as Congo���s first post-independence prime minister lasted only three months before he was arrested and executed five months later. Yet he lives on as idea, meme, symbol, icon, model, logo, metonym, specter, image, figure, and projection.

For four years I edited a book, Lumumba in the Arts, that examines Lumumba’s iconography. That book is now available.

Although Lumumba has won a place equal to other political icons like Malcolm X, Che Guevara, and Nelson Mandela, and although an equally rich or even richer imagery has developed around him, his iconography has remained underexposed and unannotated.

In fact, it is a rich iconography. It includes a whole range of renderings and portrayals, spans the whole range of media, and encompasses a variety of representations. It is no coincidence that a historical figure such as Patrice Lumumba has taken on an imaginary afterlife in the arts. After all, his project remained unfinished and his corpse was never buried.

Lumumba’s diverse iconography already started with the different names he received such as ��lias Okit’Asombo (heir of the cursed), Nyumba Hatshikala l’Okanga (the one who is always implicated), Osungu (white), Lumumba (a crowd in motion), Okanda Doka (the sorcerer’s wisdom), or Omote l’Eneheka (the big head who detects the curse), starting from his childhood. His iconography was furthered during his lifetime, especially through songs and by the press, but most expressions, however, arose after his death.

Since his murder, Lumumba has been appropriated through painting (e.g. Ch��ri Samba, William Kentridge), photography (e.g. Sammy Baloji, Robert Lebeck), poetry (e.g. Henri Lopez, Ousmane Sembene), music (e.g. Pitcho, Miriam Makeba), film (e.g. Raoul Peck, Zurlini), theater (e.g. Aim�� C��saire), and literature (e.g. Barbara Kingsolver) as well as in public spaces, stamps, and cartoons. No single form of art seems to escape Lumumba. While at first sight his iconography seems to oscillate between demonization and beatification, it is the gap between these two opposites that has proven to be fruitful for a very polymorphic iconography, one which, amongst many things, observes the memory and the undigested suffering that inscribed itself upon Lumumba’s body and upon the history of the Congo.

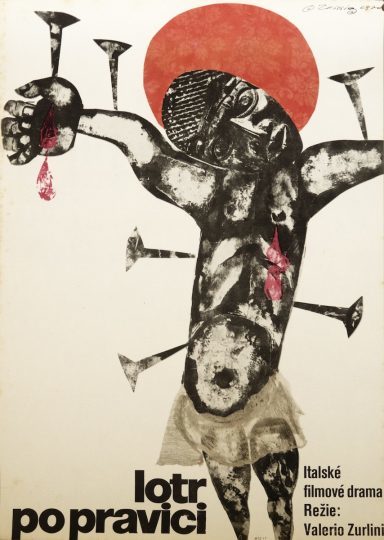

Karel Teissig, Czech poster of Valerio Zurlini���s 1968 Black Jesus, 1970. Courtesy of Judy and Jozef Mrofka.

Karel Teissig, Czech poster of Valerio Zurlini���s 1968 Black Jesus, 1970. Courtesy of Judy and Jozef Mrofka.Notable exceptions such as Patrice Lumumba entre Dieu et Diable. Un h��ros africain dans ses images, edited by Pierre Halen and J��nos Riesz, and A Congo Chronicle. Patrice Lumumba in Urban Art, edited by Bogumil Jewsiewicki, are foundational and seminal to my work on Lumumba���s iconography in regards to mostly literature and poetry in the first case, and to painting in the second one.

Two questions guided our work: What iconography arose around Lumumba and why is that iconography so diverse? One of the most striking paintings about Lumumba is Les p��res de la d��mocratie et de l’ind��pendance by Sam-Ilus (2018). The painting demonstrates both the beatification of Lumumba and the political recuperation of his figure. It critically shows that artistic creations of Lumumba’s figure and the scenes in which he is reconfigured provide anything but a window on historical veracity; rather, they often reinvent him for political reasons. In this example, Patrice Lumumba is aligned with the anti-Lumumbist Etienne Tshisekedi, who followed Albert Kalonji on his secessionist adventure in Kasai against the central government of Lumumba, and who is the father of the current president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Felix Tshisekedi. In contrast to the more realistically depicted Etienne Tshisekedi (who died in 2017), Lumumba���who died almost sixty years earlier���is more abstracted and iconized. In the image, Lumumba is the reference: the model to aspire to. Tshisekedi tries to pose like him and identify with him, looking for political legitimation and atonement from sin. But whereas Lumumba has both arms up, Tshisekedi is still trying to find the right balance and is not very confident of receiving expiation. Lumumba does not seem to be very happy being cast in this reunion with his foe. His upper body, which is slightly averted from his companion, betrays some discomfort. Not only does Lumumba “seem distrustful because Tshisekedi is probably complicit in his death,” as the artist Sam-Ilus explained to me in a personal interview, but���I would add���also because his figure is being appropriated and dragged into a misplacement. Apart from the beatification, political recuperation, and the contrast with history, Sam-Ilus’s painting also illustrates that the meanings ascribed to Lumumba depend on the interplay of differences and oppositions within the construct. Moreover, these meanings are not fixed but deferred along l’hors cadre: those people below Lumumba holding their protest signs, that is, and also the other artworks in the book, as well as those not reproduced in the book, and those yet to come. The cover thus functions as a possible portal to other fictions that defy to a greater or lesser extent what Alexie Tcheuyap calls the triple censorship inflicted on Lumumba: censorship against his person (his murder), against his discourses, and against all attempts to constitute an alternative discourse on his existence.

The answer to the first question���as to what iconography arose around him���depends on the different art forms, which the book discusses in relation to historiography in the first part, and which the book divides into different chapters in the second part (cinema, theater, photography, poetry, comics, music, painting, and public space). Throughout the different art forms, we can distinguish an iconography that has been grafted onto a Judeo-Christian tradition (as both diabolization or beatification) from a more profane trend. Remarkably, the Janus-faced figure of the scapegoat/martyr���the most recurrent figure among all the different and even contradictory things that Lumumba stood for���are to be found in both. The answer to the second question���why such a diverse iconography ��� will be answered from as many angles as there are authors. However, four interrelated realms keep recurring: the spectral, the postcolonial, the martyr, and the political.

By discussing the rich iconographic heritage bequeathed to us by Lumumba and by reflecting on the different ways in which he is being remembered, we do not only answer the two questions that guided our work, but hope equally to contribute to this imagery by making his absence more present, though without laying his legacy to rest.

An ambivalent sense of belonging

Image credit Naddel via Flickr CC.

��� Janet McIntoshNationalist gestures, resented privileges, and acute defensiveness���all are components of what it can mean to be a white Kenyan today ��� their self-consciousness and uncertainties suggest that in some respects, they are of two minds about their entitlement to belong.

In Kenya, the place occupied by descendants of British settlers in the country is a contentious issue. At times, it explodes into controversy and debate, for instance in 2017 when conflicts occurred between pastoralists searching for grazing land and private white landowners in Laikipia. In 2006, angry debates about the racism and colonial history of white Kenyans erupted when Tom Cholmondeley, the heir of an influential colonial settler in Kenya and a large-scale landowner, shot and killed a man whom he believed was poaching wildlife on his family���s farm. This was the second such incident: a year earlier, he had shot and killed another man on his land.

The uneasy nature of white Kenyans��� sense of belonging in the country is unraveled and analyzed in Janet McIntosh���s fascinating book Unsettled: Denial and Belonging Among White Kenyans. Based on extensive in-depth interviews, and structured poetically into different themes which explore varying components of the white Kenyan experience, McIntosh���s book reveals the complex and often ambivalent positions of white Kenyan subjectivities in contemporary Kenya. She explores their relationships to the land, to Kiswahili, to domestic workers, to other black Kenyans and to their own white community. The last chapter is dedicated to white Kenyans��� relationship to the occult and how they justify or explain their participation in practices that transcend a ���rational��� European worldview.

Through her interviews, McIntosh discovers an interesting dynamic at play in the white Kenyan consciousness. Their uneasy sense of belonging is expressed through the notion of a ���moral double consciousness,��� a term borrowed from the phrase ���double consciousness,��� defined by W.E.B. DuBois, and which in McIntosh���s book is used to describe what results when white Kenyans look at themselves through the eyes of others, and experience the shock of seeing that their community is being seen. They were raised to think of their settler families as good, but now have to grapple with the fact that they were in fact, oppressors and that they are also seen through the same lens. They experience an inner self-doubt, and shift between a moral self-assurance and a sense of anxiety elicited by their critics. As they cannot for long dwell in shame about themselves or about their colonial past, some settle into a ���defensive stance��� in order to remain in their comfort zone and mystify their structural advantages. Others focus on their felt bonds to Kenya and insist that their personal intentions take precedence over history. A very small number try to find ways to empathize with black Kenyan perceptions. In today���s Kenya, argues McIntosh, white Kenyans are no longer looking to rule, but to belong.

White Kenyans who try to maintain their comfort zone adopt a kind of ���structural oblivion;��� a position of ���ignorance, denial and ideology��� which comes from occupying an elite social position, and involves refusing realities like the reasons for the resentment towards them from less privileged groups. This oblivion operates alongside their taking for granted a hegemonic model of the way the world should be���in other words, a liberal individualistic model of personhood and a capitalist model of the economy. In this view of the world, white Kenyans are to be seen as individuals, and cannot be held responsible for the crimes of their forebears.

Perhaps the most glaring and contentious area in which the presence of white Kenyans in the country comes to the fore is around the question of land. As McIntosh notes in her second chapter, land is already a ���painful theme��� across Kenya which often plays out in terms of which ethnic group was on the land first. Taking the reader back in history, she describes how the British colonial government expropriated land and imposed individual land rights to encourage agricultural production and ���proper��� land use. The Crown Lands Ordinance of 1902 imposed English property law and forced Africans to give up land that was not occupied or developed, enabling the colonial state to give huge swathes of it in the Rift Valley to European and South African settlers. These fertile areas, so desirable to white settlers, were places where Maasai pastoralists practiced seasonal migration under a complex system of rights to land and water. As the colonial administration created more room for white settlers, the Maasai were coerced into signing away their lands. In 1911 and 1912, thousands of Maasai were herded toward the south at gunpoint and by 1913, they had lost between 50 and 70 percent of the land which they had previously used.

The settler descendants that McIntosh interviews about this history do not seem to know about the land expropriations. Operating out of what she describes as ignorance, collective defensiveness and possibly systematic whitewashing, settler descendants spin their narratives to assert that the Laikipia territories were fairly purchased from the Maasai, or that Laikipia was a no-man���s land at the time of settler arrival, echoing the classic settler frontier ideology of terra nullius. Many believe that their forebears worked to develop the land, and do not think that they should give it up or compensate the Maasai. One settler descendant understands the Maasais��� grievances but cannot accept that they deserve any kind of reparations. In his words, ���It���s a romantic effort to recreate an impossible past.��� Echoing their colonial predecessors, some of McIntosh���s interviewees undermine the Maasais��� pastoralist lifestyle, deeming it haphazard, unfocused and based on ���feelings��� rather than deliberation or pattern, in comparison to European notions of responsible land use and ownership. Several of her interviewees evoke childhood memories when describing their attachment to the land and wildlife, encouraging an idea of white belonging as ���innocent.��� McIntosh writes that ���black pastoralists are often seen as abusing the land, whereas white���s relationships to land are described as intimate and sensory,��� and white Kenyans can assert that they appreciate the land in ways the Maasai do not.

Although these ways of thinking may seem outrageous today from a non-white Kenyan perspective, they have successfully enabled white Kenyans to assert their entitlement to land in the present day. Those who are sitting on some tens of thousands of acres can claim that they are acting as stewards of the land. This positioning justifies the extensive involvement of white Kenyans in the conservation industry and the expansion of community-based conservation initiatives now widespread on much of the land belonging to settler descendants in Kenya. Although couched in language about empowering local communities, conservation projects do not level the playing field between white and black Kenyans. Rather, as McIntosh writes, ���whites reproduce the larger relationship of patrons to black Kenyans;��� local communities must rely on the support of white conservationists for their survival and well-being, while whites are re-inscribed in a privileged position. Helping communities has become for some progressive whites, a kind of ���cover story��� in order to hold onto their resources ���in the face of a public that objects to radical inequality.���

The paternalism present in land-based conservation initiatives also carries over into domestic spheres. McIntosh writes about how white Kenyans occupy an ambivalent position, expressing a fondness and kinship for their domestic staff and yet paying lower wages than recently arrived expatriates. When cash is needed for special requests, they dole out extras, encouraging a dependency on the part of the domestic staff while they in turn experience a sense of feeling needed and embedded in the lives of their staff. Such relationships work to create ���a sense of belonging to the Kenyan people and, in turn, to the nation.���

Race-class boundaries are trickier to navigate when it comes to marriage and relationships. McIntosh observes how interracial marriages are less common among Kenyans from settler families than among white expatriates. While they profess a desire to belong to a multicultural country, white Kenyan���s intimate relationships are for the most part with other whites and they tend to self-segregate. While interracial marriage is often frowned upon in the white settler community, speaking African languages offers a safer way to connect with black Kenyans. White Kenyans��� attitude toward Kiswahili is described by McIntosh as a kind of ���linguistic atonement��� that enables them to ���mitigate a history of colonial discrimination.��� Whereas before independence, Swahili was something that ���one condescended��� to speak, today, speaking Kiswahili is important to white Kenyans as a way of signaling their belonging to Kenya. For some, it also creates the impression that the race and class-based playing field has been leveled and Kenyans ���of all backgrounds can connect with mutual pleasure.��� However, their primary use of English over Kiswahili for more intellectual conversations reveals a linguistic hierarchy at play; English remains the language of authority and Kiswahili is essentialized as a less intellectually sophisticated language than English. White Kenyans can therefore move fluidly between the authority of English and the authenticity of Kiswahili, enabling them to feel both white, and privileged, as well as Kenyan and ���cosmopolitan.���

One area in which there are some interesting ambiguities is around the occult which until now has been largely thought of in the settler consciousness as the domain of Africans and not whites. In Unsettled, some settlers claim that the occult has no real force, but at the same time, they seem bewildered by how it operates and keep open the possibility that it does have some power. Some even consult occult help to restore their health or to police difficult employees. McIntosh notes that this signals a significant departure from the contempt settlers had for African beliefs.

Things have certainly changed in the decades since Kenya���s independence, and white settlers have attempted to adapt to these changes. Yet, as McIntosh observes, their desire to belong straddles an ambivalent position. They want to integrate, but not to the extent of practicing interracial romance; they want to see the country united, but they self-segregate along ���cultural��� lines; they feel a kinship with their domestic staff, but ���secure affection through economic dependency.��� As McIntosh eloquently sums it up, white Kenyans are ���wrestling with the incoherence of a consciousness founded on colonialism that is confronted with the imperative to renounce it.���

McIntosh���s book provides brilliantly written, nuanced and insightful analysis into white Kenyan subjectivities in contemporary Kenya. One area in which the book could arguably offer further insight is in analyzing the role of Asian Kenyans in the racial hierarchy, who as she notes ���aren���t certain of their entitlement to belong either.��� McIntosh explains this absence to her decision to focus on denial and belonging as centering on the anxieties that white Kenyans have towards their community���s treatment of black Kenyans. They must ���reckon��� with black rather than Asian Kenyans. Nevertheless, given how long and how entrenched the white-Asian-black hierarchy has been in Kenya, some analysis on those dynamics would be a welcome addition.

In considering the question of white Kenyans��� entitlement to belong, it is worth asking what is at stake in their desire to belong. As noted in the book, it is ���convenient��� to belong when ���one wishes to stake a claim to land, jobs or other entitlements.��� Instead, the question of whether white Kenyans do in fact belong in the country must assume secondary importance to the question of how Kenyans contend with a legacy of a past which still impinges on the present. This legacy continues in ongoing land dispossessions, in the disproportionally powerful role occupied by white Kenyans in conservation, in the erasure of Kenya���s extremely violent colonial history in public narratives, and perhaps most significantly, in a capitalist development model which is built on the crimes of the past. Perhaps one way for white Kenyans to truly commit to belonging to the country is to accept responsibility for the past, as individuals and as a collective, and to agree to demands for reparations for the crimes of their ancestors.

June 30, 2020

Six LGBTQ+ figures from African history

Image credit Sheila Sund via Flickr CC.

As Pride month comes to a close, it offers us an opportunity to reflect on the history of sexuality in Africa. Despite the propaganda spouted by some conservative political, religious, and other forces on the continent, a close look at African history reveals that it is not gender queerness that is ���un-African��� but rather the laws that criminalize it. Historically, many Africans were unapologetic about their sexuality and gender non-conformity, though their personal stories remain difficult to uncover. LGBTQ+ scholarship in Africa finds that several anthropologists actively ignored or hid these realities. The multitude of accounts have been passed down through oral tradition leaving them open to misinterpretation and misconstruction, while a standard of heteronormativity remains largely unquestioned. Nevertheless, recognition and representation have a way of personifying and enabling us to better understand our identities, especially for the many undocumented queer people who are today subverting gender roles in Africa. It is important to document LGBTQ+ stories and history to reverse the erasure primarily caused by colonialism and fundamentalism.

Historically, several African cultures believed that gender was not dependent upon sexual anatomy, but was instead more energetic. The Dogon of Mali reportedly traditionally worshiped ancestral ���teachers��� who were described as intersex and mystical. Androgynous deities like Esu Elegba, the Yoruba god/ess of the crossroads, or Mawu Lisa, the Dahomey creator god/ess, can be viewed through a contemporary lens as possible patrons for LGBTQ+, despite being historically demonized. Many ancient matriarchal structures in Africa practiced female husbandry, where women attained wives and assumed economic responsibility over the children. In recent history, Black Dandyism (i.e ���La Sapologie��� in DR Congo) continues to challenge gender performativity and binaries.

Colonial powers once denigrated Africans as having primitive, bestial sexuality as proof of their inferiority. Ironically, many of these Western states now condemn the sodomy laws they installed during colonial rule. Arguably, it was not homosexuality, but rather homophobia, that was imported to Africa from the West. While contemporary labels were not affixed the same way in precolonial Africa, non-heteronormativity (self-identifying and not), is encompassed here under the umbrella of LGBTQ+ for the purpose of language. It is important to note that nuanced understandings of queer African identity may not have been constructed in the same way had they been adequately documented. This further highlights the role of language in a complicated history of othering, and why contemporary critical discourse must continue to engage, uncover, and more accurately inform our futures.

Here are 6 LGBTQ+ figures in African history that you should know

Queen Nzingha Mbande (Angola) (1600s)

Queen (or Female King) Nzingha Mbande (1583���1663) ruled the kingdoms of Ndongo and Matamba in the north of modern day Angola. She assumed power after the death of her father and brother, during a period of rapid growth in the slave trade. Nzingha led a four-decade military resistance against Portuguese dominion and is revered for her intelligence, military tactics, and diplomatic brilliance.

Nzingha���s dubious sexual identity finds different accounts pointing to a heterosexual marriage, to female wives, and to a harem of men who dressed as women. She certainly transgressed gender binaries, answering only to ���King,��� leading troops into battle, and wearing both men���s and women���s clothing. Her female husbandry illustrates the ���queering��� of gender roles in Africa, traditionally less closely identified with biological sex. Nzingha���s ability to perform a queer identity can be partly attributed to her royal status and power. However, this doesn���t delegitimize the reality of relationships between ordinary women based on love and desire during her time. African lesbian sexualities have largely been shaped by silence, secrecy, and repression.

King Mwanga II (Uganda) (1800s)

King Mwanga II (1868���1903) became the 31st Kabaka of Buganda (Uganda) at age 16. He was openly gay (or bisexual), a grave offense under the British Empire who tried to convert him from his ���hedonistic and satanic��� ways. Mwanga antagonized the British who he saw as intruders, fighting to free his country of their influence during his reign. His controversial story is associated with Martyrs��� Day in Uganda which is often co-opted into a political anti-LGBTQ agenda, as Mwanga is said to have killed several of his male companions (martyrs) leading to his exile in 1899. Mwanga���s pre-colonial story is proof that homosexuality was not an ���import from the West��� as is often claimed.

Area Scatter (Nigeria) (1970s)

Area Scatter was an Igbo gender non-conforming folkloric musician from southeast Nigeria. In the 1970s, he disappeared into the wilderness, reemerging seven months and seven days later, spiritually reborn and beautifully adorned as a woman. She claimed to be endowed by the gods with musical gifts, and her new name ���Area Scatter��� meant ���one who comes to disorganize a place, to shock, and to reclaim.��� Very little is known about ���the curious case of Area Scatter��� aside from a rare video clip of her performing to royalty. She led a band called Ugwu Anya Egbulam famously playing her thumb piano. She was admired, praised on the streets, and widely respected at the time. Area Scatter���s story shows how gender came to acquire a Eurocentric understanding and performativity in many African contexts, where queer identity and fluidity was not always subject to ridicule, threats, and attacks.

Simon Nkoli (South Africa) (1970-90s)

Simon Nkoli (1957���1998) was one of Africa���s most prominent anti-apartheid, gay rights and AIDS activists. In 1983, he formed the Saturday Group, the first public, black LGBTQ+ group in Africa, established in response to implicit racism by the predominantly white Gay Association of South Africa (GASA). Nkoli was arrested in 1984 and faced the death penalty on charges of treason for his anti-apartheid activism. He came out to his colleagues in the United Democratic Front in prison, a courageous act that broke the silence around homosexuality in the liberation movement. He was acquitted and released in 1988, and soon founded GLOW which organized the first Pride parade in South Africa in 1990. Nkoli received several human rights awards globally and was one of the first gay activists to meet with President Mandela in 1994, campaigning for the protection from discrimination in the 1994 Constitution and for the repeal of the sodomy law. In 1996, South Africa became the first country in the world to provide constitutional protection to LGBTQ+. Among the earliest publicly HIV-positive African gay men, Nkoli is widely referenced and heralded; there���s even a ���Simon Nkoli Day��� in San Francisco.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode (Nigeria) (1980s)