Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 170

June 20, 2020

The book of his life

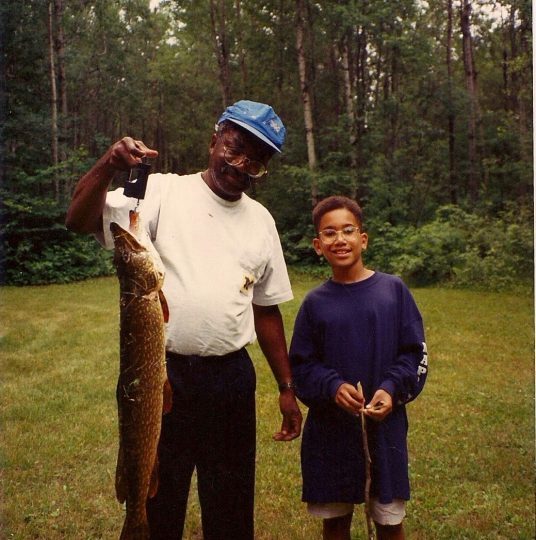

Image via author.

I sat bedside in the Intensive Care Unit room, uneasy with all the commotion, discomforted by the beeping machines and tubes. My Dad was more alert than two days before, and that at least, was a relief.

It was that night, shortly after I had landed at O���Hare Airport in Chicago and drove up to Milwaukee, that my mother received a call from the hospital. It was an emergency. My Dad was moved to the ICU to be monitored, just in case they had to put him back on the ventilator. I thought to myself how strange a word ���intubate��� was. Change one letter and it signifies a completely different stage of life. We rushed to the hospital to find my Dad in intense pain, and a resident doctor telling us that he could have two or three days left.

But on this day, things had calmed down. A specialist in charge happened to be visiting when I arrived and told me not to worry, that the were only using the ICU as an extra precaution. I relaxed a bit, for the first time in over 48 hours, and believed that this visit was to lift my Dad���s spirits, to get him through this fight and out to the other side. I also knew that the other side meant a period of aloneness for him, as the hospital was closing itself off to ���non-essential visitors,��� so as to protect its patients from the looming COIVD-19 outbreak headed our way.

On this visit, we talked about my family, my wife (that I should take her to Jake���s to eat corned-beef), my three year old son (take him to explore the woods and the creek in the back of their house), all the plans he had for us. I asked him what he wanted, what he needed, a visit from my brothers? Anything to help give him the strength to fight?

He said, ���Boima, I���m tired, and I���m not sure there���s anything left for me to accomplish in life.���

I said, thinking that this would be an encouragement, ���Yes! Now is the time for you to relax a little and be a grandpa, enjoy this less stressful stage of your life.��� Thinking back, it pains me a bit to think that we were on different pages of the book of his life.

My father did in fact live an extraordinary life.

He was born in Bonthe, Sierra Leone, and spent his early life on Sherbro island off the coast of British colonial Sierra Leone. He lived as a typical West African country boy, fetching water and fire wood in the mornings with peers, making interludes to forage fruit and seafood from the forest and sea. In his later years, when he was in a storytelling mood, he would tell us about when he went to New Orleans and saw all the seafood food people were paying top dollar for, and would brag “lobsters and oysters were what I used to eat in Africa when I was poor!”

At school age, he was sent to a Catholic school in Bo, a hundred or so miles ���upline��� in southern Sierra Leone. Christ The King College was a Catholic boarding, school set-up as an alternative to the British founded Bo School, and run, at the time, by an Irish priest. He excelled and would become one of the school���s first top students and assistant teachers (Senior Prefect). Upon graduation, he would spend a brief time in Freetown, a city at the time steeped in the spirit of independence. It was through the government of Sir Milton Margai, the first president of Sierra Leone, that he would receive a scholarship to study in the US as part of a program to place Sierra Leonean students at historically black college and universities (for me, a surprisingly pan-African relic of the time).

He landed at Fisk University in the American state of Tennessee, just as the Civil Rights Movement was hitting its stride. He would tell his kids stories of cultural misunderstandings between him and Americans, both black and white, and even about an encounter with the KKK (he had initially thought one of their processions through downtown Nasvhille was a parade). A series of strange coincidences would cause him to loose his scholarship, and he would become abandoned in this new strange land. He would then move into a friend���s apartment in Washington DC���s Columbia Heights neighborhood (he told us he slept in a kitchen full of roaches), and worked at the Sierra Leonean embassy, trying to navigate America as an undocumented immigrant.

My Dad always used hard work to get ahead, and from the margins of American society he would work his way up through the system. Embodying the American immigrant dream, taking advantage of its social mobility through education, he would jump at every opportunity that crossed his path. From teaching Krio and Mende to Peace Corps volunteers in Kingston, Jamaica, to getting back into college in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, eventually entering Medical School at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and becoming, for many years, one of the only (the only?) black doctors in Milwaukee, a majority black and Latino city.

My father came to be a very proud Wisconsinite, and found unquestionable success in the United States of America. He believed fully in the American Dream, all the way through the Obama Presidency. But, in recent years he started to question if the US was indeed past its prime, even approving of my decision to seek a life outside of the country.

That afternoon I was visiting with him, he told me some of the observations he had been making in the hospital���how the racial discrepancies bothered him with all the doctors and nursing staff being white, while the assistants and cleaning staff were black. This bothered him, seeing something broken in a society that had allowed him to rise up.

One of the last things I told him was that Trump was mishandling a pandemic, and because of that he wouldn���t be able to have visitors at the hospital. He chuckled. He looked at the clock, signaling that he wanted to rest. I expected my mother to visit in the afternoon, and throughout the rest of the week as his care-taker. She did visit that afternoon, but came back telling me that the hospital had closed itself to all visitors while he was in the ICU. A couple of days later he was transferred back to the cancer wing he had been stationed in for the past three or so months. We were relieved, he seemed to be doing better. That week my mother celebrated her 69th birthday, and we took time that week to relieve some of her stress. Later in the week we were able to get the nurse to answer my dad’s cellphone and have a video chat with him. He seemed ok, but still tired. I called for my son to talk to him but he wasn’t in the house and my Dad didn���t have the energy to wait for him to come back. I showed him his house and his yard, then we hung up.

The next day another phone call like the one the week before. ���Your father is not doing so well,��� my mother told me. They allowed her to go to the hospital ���to increase his morale,��� she said. A few hours later another call, ���Boima, come now.���

My mom, my sister and I saw my Dad that evening. He was in bad shape. It was time to say goodbye. He had refused treatment, and now it was just about comforting him for the rest of his time on this Earth. He passed away the next day���from what they told me, I was parking the car in the garage underneath the hospital, on my way to see him.

My father didn���t have the coronavirus (we think), but he had a very similar condition which caused comparable suffering. I felt compelled to write this essay after reading about the many people who also have died in the hospital these months, whose spirit was damaged by a lack of visitors, whose family are haunted by the specter of ���what if?��� It isn���t a great feeling, but it is perhaps made less sharp being a collective one. So I write this for my Dad, and for anyone who needs this.

June 19, 2020

Homeless in the city

Nairobi, Oct. 2009. Image credit Maji na Ufanisi via Flickr CC.

In the first two months of Kenya’s pandemic lockdown, Nairobi’s administration evicted 7000 people from their homes. With no warning, compensation or alternative housing provided, many of these residents, whose livelihoods were already jeopardized by the lockdown, are living in the open ruins of their former houses. Against the threat of looming evictions, this article details the Kibera evictions of 2018 and the formal anti-people politics of housing for the poor that persists in Nairobi.

This post is from a new partnership between the Kenyan website The Elephant and Africa Is a Country. We will be publishing a series of posts from their site every week. Posts are curated by Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

It has been a long time since waist-high concrete beacons dropped down along the middle of the Kibera slum in Nairobi, marking the corridor of a future road and serving as an omen of change. But for almost two years, they stood rather impotently, largely ignored and even vandalized a few times, as no road came. Legal battles had frozen the encroaching highway in its tracks.

The road that was yet to come was Missing Link 12, a Sh2 billion (18.5 million USD) four-lane highway partially funded by the Japanese government, one of many other ���missing links��� that would connect major highways in Nairobi. In the meantime, life in Kibera carried on for years between the beacons in that 600-metre-long corridor.

This changed on July 20, 2018, when Maxwell (who requested that his surname not be used), who lived in Mashimoni, squarely within the road corridor, heard an announcement on the radio: ���There will be a demolition on Monday morning.���

Word was starting to get around, but many were still making light of the news. After all, the road had been in the works for years and the Kenya Urban Roads Authority (KURA), the government body responsible for construction of this road, had just completed the first stage towards developing a Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) only days before. Maxwell recalls the radio ads sounding more like warnings for motorists to avoid the area because of possible demonstrations. He felt confident that the residents would be given a stronger warning the day before the actual demolition, but, just in case, he moved his belongings to his cousin���s home in Makina, a safe distance from the demolition zone.

Maxwell made the right call. At approximately 7am on Monday, July 23, three bulldozers, accompanied by hundreds of heavily armed Administration Police officers, descended on houses, kiosks, churches, and schools from the Ngong Rd end to the Lang���ata Rd end of the corridor. The concrete beacons became marshals for a swift and total demolition.

KURA spokesperson, John Cheboi, told��The Elephant that 2,182 structures within the corridor were targeted. According to Amnesty International Kenya, over 10,000 residents were displaced. It was the largest eviction to occur in Kibera since the 2009 relocation of 5,000 people from Soweto East under the Kenya Slum Upgrading Project, for which decanting sites were built in Lang���ata.

Several other Missing Links throughout the city will also require evictions, including at the Deep Sea slum in Parklands, which is scheduled to be cleared to complete Missing Link 15, a mass eviction which may affect another 3,000 people. On July 19, the Multi-Sectoral Committee on Unsafe Structures released a public notice requesting that residents of Kaloleni, Makongeni, Mbotela, Mutindwa, Dandora, and Kenyatta University (Kamae) move voluntarily in advance of ���the removal of all structures.���

Legal framework on evictions

For a problem that is set to continue, Kenya has a comparatively imprecise legal framework on evictions. ���There are enough constitutional provisions that would forbid the government from doing what it did that morning, but there is no eviction law,��� says Ir��ng�� Houghton, the Executive Director of Amnesty International Kenya. Article 43(1b) of Kenya���s Constitution guarantees the right of every person to ���accessible and adequate housing��� and Article 40(4) affirms that, in the case that the state deprives any person of property, ���provision may be made for compensation to be paid to occupants in good faith of land acquired under clause (3) who may not hold title to the land.��� The Internally Displaced Persons Act of 2012 also holds that people displaced by ���large-scale development projects��� are entitled to a human rights-based process of eviction.

In addition, Kenya is party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the African Charter on Human and Peoples��� Rights. All of these uphold the right to adequate housing and, to varying degrees of specificity, provide guidelines for humane evictions within a human rights framework. Article 2(6) of the Constitution makes any treaty or convention ratified by Kenya part of Kenyan law.

There are also eviction guidelines from the Ministry of Housing that give, for example, conditions under which evictions should not occur, several of which were flagrantly violated in the Kibera demolition: no evictions in inclement weather, while students are in school, or without completion of a Resettlement Action Plan (RAP).

There have also been several major judicial precedents set in the last few years that interpret the Constitution to prioritize human rights, regardless of land ownership or tenancy status. In 2011, police and unidentified youth evicted more than 1,100 residents and destroyed 149 homes on public land near Garissa that was to be used for a road. The High Court, however, ordered the government to restore the evictees to their land, rebuild their homes, and pay Sh220 million in compensation, citing that evictees��� ���rights to housing and to be treated with dignity and respect had been violated.���

Then in 2013, after the railway pension board gave residents of Muthurwa Estate in Nairobi 90 days to vacate before demolition, the High Court ruled that the board had violated evictees��� ���rights to adequate housing and sanitation, and human dignity, and violated children���s rights to protection after it sent bulldozers to demolish hundreds of homes at dawn.��� Judge Isaac Lenaola, in this ruling, added, ���I must lament the widespread forced evictions that are occurring in the county coupled with a lack of adequate warning and compensation which are justified mainly by public demands for infrastructural developments.���

In the case of Missing Link 12, the High Court issued a similar order for Petition 974 (2016) requiring that a full RAP be completed before demolition. Shafi Ali Hussein, the director of the Nubian Rights Forum and one of the petitioners in that case, was present when KURA met with the Kenya National Human Rights Commission, the National Land Commission and Kibera community leaders. KURA agreed to roll out the RAP ���with immediate effect,��� according to Hussein. In the next few days, KURA staff began enumeration, the first step of a RAP where the number of structures is counted and basic information on affected residents collected.

However, according to Hussein, KURA seemed ill-prepared to carry out the exercise, and the forms that staff members used for the questionnaires did not have serial numbers. Enumeration finished on Friday, July 20, the same day Maxwell heard the radio announcement warning of evictions. The following Monday, it was to continue by verifying the data that had been collected, the next step necessary for setting up a compensation scheme. ���But on Monday, unfortunately, we saw bulldozers,��� said Hussein.

According to KURA spokesperson, John Cheboi, residents and owners of structures within the corridor had been notified to vacate by July 16. When The Elephant asked Cheboi why they began the enumeration exercise days after residents were allegedly told to vacate, he responded that they were called back for the exercise.

Anti-poor urban design

Nairobi has remained true to its origins as a city designed for its elite, leaving for its working class what were literally and now figuratively remain ���labor reserves���: unserviced, unrecognized crevices between its formal parts. Though the colonial urban management philosophy that Africans were unfit for city life was in effect a ploy to keep cheap African labor available for European commercial farms in Rift Valley���s ���White Highlands,��� the result was chronic under-investment in urban spaces for indigenous Kenyans.

Kefa Otiso, professor of geography at Bowling Green State University, explains that, in addition to other race-based policies that prioritized European and Asian access to land and other economic resources within Nairobi, this ���return to the land��� policy resulted in many indigenous Kenyans settling in unsafe urban and peri-urban areas; they became, in his words, ���the precursor of many modern slum and squatter settlements that are vulnerable to forced evictions.���

Nairobi���s population is set to hit 6 million by 2030, according to the World Bank, and currently 60 percent of its residents live in informal settlements. Much of this growth is propelled by rural-to-urban migration. At the current rate of urbanization, this means almost half a million new slum dwellers every year. At the same time, land prices in and around Nairobi are skyrocketing due to a growing influx of illicit money laundered primarily through real estate and property markets. For the growing number of low-income, working-class households looking for affordable housing in Nairobi, this leaves few options outside of informal settlements.

In many ways, Nairobi���s anti-poor urban design today is a facsimile of colonial plans. Many low-income households are forced into the city���s ���low-quality, high-cost trap,��� where landlords are free to pursue economic incentives without administrative oversight or protection for tenants.

Lucrative and efficient, slum real estate allows landlords to quickly buy ���rights��� to build on the land and see a return on investment without truly being held accountable for structural integrity, or in the case of the Kibera, demolition. Landlords actively continued to build within the Missing Link 12 corridor even though there was impending construction, and with the shortage of cheap urban housing in Nairobi, one could always find tenants.

In the ruling of the 2013 Muthurwa case, Judge Lenaola gave the Attorney General 90 days not only to outline the government���s policies on evictions and explain whether they meet international standards, but also to explain what positive steps they would take to realize the right to accessible and adequate housing as guaranteed in the Constitution. ���The right to adequate housing cannot be aspirational and merely speculative,��� Lenaola said. ���It is a right which has crystallized and which the State must endeavor to realize.���

The everyday, systemic violence that policy wreaks on the urban poor is often obscured by the obvious, photographable violence of events like the July 23 demolition. But even the sensational images���like the viral photograph that uncomfortably compressed into a single frame two Kibera evictees standing on rubble and golfers preparing to tee off just a couple of hundred meters away���sent a simple message worth emphasizing: that alleviating the suffering of certain people, even when the opportunity cost is low, is not worth it. A little more humanity���a few more hours��� notice, perhaps���still could not justify delay in progress.

���That breeds a sense of historical injustice, this sense that we���re tenants of the city, we don���t really own it,��� says Houghton of conversations he has had with affected residents of Kibera, one of whom said, ���The city belongs to others and we just move in and out of the pieces of land that they don���t want, until they want it.��� That���s the cynicism that a lot of people in the community have now, according to Houghton.

The images from Monday were perhaps then a more honest reflection of how the city sees its poor, something usually otherwise masked by political mobilization. The Kibera demolition would not have happened before the elections last year, says Maxwell from Mashimoni, and certainly not before ���The Handshake.��� Neutralized by bridges and alliances, the local and national leaders who would have otherwise drawn energy from Kibera, an adversarial hotspot, and taken a staunchly antagonistic position at least in rhetoric, were too quiet.

Rights and laws aside, the Kibera demolition has already happened, and it cannot be disputed that in the moment it rendered, in Houghton���s words, ���people indistinguishable from property���: simply a large, inconvenient unit of ���unsafe structures��� that must be removed to make space for development. It took two days to clear the entire corridor.

Art and the politicization of African bodies

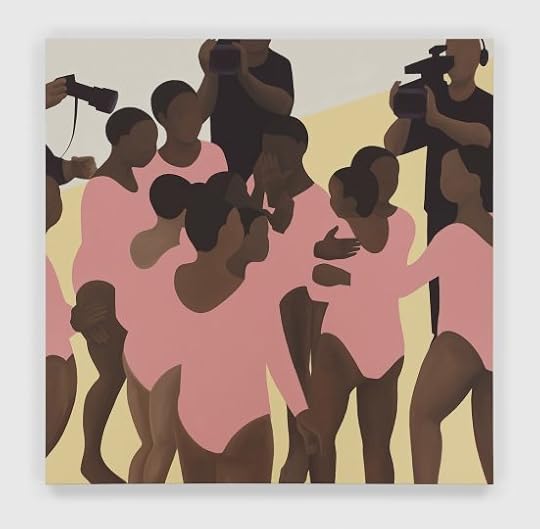

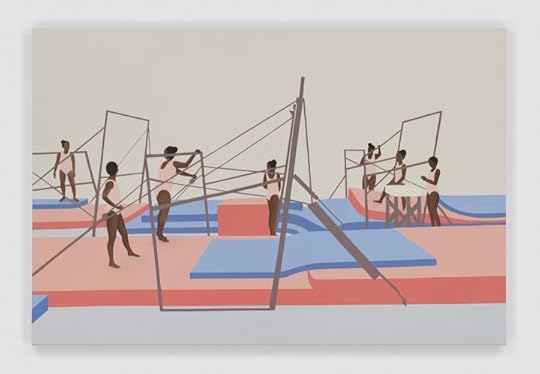

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi. All images �� Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg, SA. Photo: Nina Lieska.

The painter Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi doesn���t appear disappointed that the public did not get to view her first solo show Gymnasium at Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg. Nkosi is someone who, in her words, likes to ���undermine the exclusivity of the art.��� The Instagram version of the exhibition provided audiences an opportunity to see her paintings ���in the same way.���

A profound interest in how people inhabit space and how certain spaces come to occupy people���s historical imagination have animated her practice; first as a designer and now as painter. In Gymnasium, there is an interrogation of the art market���s valuation and validation of figuration instead of abstraction and formalism as modes of expression adopted by African contemporary artists. As someone who is fluent in the visual language of abstraction and formalism, but mindful of the politicization of African art and black bodies, Nkosi poetically and tellingly invites audiences to see a predominantly white space, like that of gymnastics, through the color brown. Spectators, gymnasts and judges display brown skin color and are depicted interacting with each other and the space they occupy through wonderfully vibrant and intricately mixed pastel colors. Nkosi displays a unique comfortability in rendering spaces in the absence of actual figures. In so doing, she asks her viewers to consider what it means to stand directly on the floor mat used by gymnasts for floor exercises. Other scenes feature crowds of spectators and judges or of gymnasts at work, tumbling, high-fiving and hugging. As a painter, she feels excited by a new generation of South African artists, including Bonolo Kavula and Mmabatho Grace Mokalapa, who do not feel compelled to follow the trends of the art market.

Nkosi spoke to Drew Thompson from Johannesburg about the evolution of her practice and how she locates herself in contemporary African art as a painter interested in abstract forms and experiences.

Spring Floor IV (2020). Oil on canvas 134 x 134cm.

Spring Floor IV (2020). Oil on canvas 134 x 134cm.Drew Thompson

What is your relationship to abstraction, formalism and minimalism? How did you come to these visual languages as modes of expression?

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

I had a small design practice that ran parallel to my studio practice, and design was the commercial part of my work. Abstraction and minimalist art would inform my design work. Then, it started to infiltrate my painting practice. I was starting to pare things down to their essential forms and see what are the basic elements that you need to understand a human figure or to describe a space. [This process] coincided with my interest in architecture, which was at the beginning of my painting life. I was painting architectures, specifically buildings that were apartheid architectural designs, so built between 1948 and 1980s, in Johannesburg, mostly banks, apartment buildings and monuments. I started to think about how the figure and geometry work together to make an architectural space.

Drew Thompson

In art historical discourses, especially as they relate to Africa and the diaspora and other non-white contexts, design is often a missing element. Were you able to explore things in painting that you couldn���t explore in design?

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

In my first paintings I was thinking about African architecture and looking for what is an African architecture in South Africa. At the time, I was really interested in Ndebele art and design on houses and the link to storytelling. Also, I was thinking about Zulu beads, which similarly use geometric shapes for communication. Those works for me were really a perfect midpoint between art and design. They were aesthetic for aesthetic reasons but also had this ability to communicate complex ideas. And there was great regard for the people who made the designs, which for me links back to this idea of artists being valued in a way that designers aren���t. To me I feel it is important to remember that the categories���craft, art, design���are not natural, but rather are inherited from a particular European mode of thinking that make these distinctions. Maybe these things are not so different.

Team (2020). Oil on canvas 150 x 150cm.

Team (2020). Oil on canvas 150 x 150cm.Drew Thompson

Some of the paintings in the Gymnasium series you have labeled on your website as ���architecture��� and others as ���figures.��� How are you thinking about the series in terms of architecture and figuration?

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

When I started the Gymnasium series about three years ago, I���d been immersed in portraits for a long time; the move from faces to wider scenes and architectures felt like a real break, a very different interest. But soon after that, figures emerged in these spaces���gymnasts and judges. When they did, I began to read about the history of gymnastics, and started to learn about the role race has played in that history. I immediately started to feel resonances between the series, a sense of continuity as opposed to rupture. Beneath their surface differences���the specificity of the faces on the one hand, and the facelessness on the other���lie the same questions I���ve been wrestling with for years: about blackness in historically white spaces (portraiture and elite gymnastics), and about the role and meaning of the individual.

What the Gymnasium paintings offered me was a chance to explore an interest I���ve had for years, which is the relationship between the human figure and the space around it. Since my early days of painting I���ve been thinking about the different levels that architecture works on. Architecture is about physical structures���planes and angles, etc���but it is also about the less tangible structures created through our perceptions and ideas. I like to remain conscious of how architecture is used as a tool of social control. The structures we live in, and with, deeply affect how we feel and act. The dynamic that is created on the canvas when you place a human form inside a particular architecture therefore interests me on many levels: visual, psychological, ideological. Inside the Gymnasium I have the opportunity to work through these ideas in different ways.

Drew Thompson

Building on that, it is very easy to forget that you do have a larger body of work that you have been doing for some time. What kinds of questions did Gymnasium allow you to answer that you developed in your larger body of work, like ���The End of History��� and ���What it is you keep forgetting?���

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

I think what came together here [in Gymnasium], and what is the apex for me, is thinking about my own identity as an artist, as a woman, [and] how people perceive me as a black woman of color. Finally, I found a way to deal with the discomfort I feel in having that be such a large part of the narrative around my work and even about my work. I had never painted black women in my work [until Gymnasium]. I never painted myself in [that] way. I think the other work was about being sure to sort of paint that part of who I was���those obvious markers���out of the work. It was very much an effort to not paint that part of myself. There was always this feeling that I should be making work that was around my racial and gender identity, but I never wanted to do that in this very forward way. Not that I was not interested in people who were making work like that. It was very useful for me to see myself reflected in that kind of art, in art that was dealing with blackness and black girlhood or womanhood. I felt like I had so many other things I was also talking about, and I wanted to be able to talk about them without having this signature: this is my identity. Gymnasium was the first time I was addressing this question, this is the work where my identity is most apparent, and I am also making a comment about that.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by STEVENSON (@stevenson_za) on Mar 26, 2020 at 9:14am PDT

Drew Thompson

I think what is so interesting is how you are making a critique about that identity that is being thrusted on so many artists who identify as black American, African and/or of the Diaspora. In Gymnasium, such a critique comes to the fore. In so many ways, we could read this work as about ���black��� girls, the spaces they travel, and how they are looked at in particular spaces. But I think here you are asking a certain set of new questions.

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

For years there has been a question for me about what people do with the paintings when they don���t give you the figure. How do you read this work? In terms of the market, it has been interesting to see which works sell and which works don���t. The biggest painting in the show, ���Spring Floor,��� is an abstract painting with almost nothing in it. It is a large painting that is a lot wider than the other big paintings in the show. I really like that painting. It has not sold. Conceptually it is one of the more interesting ones for me as it implicates you as a viewer. When you stand in front of it you are on the implied floor, which extends beyond the bottom of the painting. In this moment, when black figuration is really desirable, I wanted to test to see: can a smart figureless painting in this body of work compete at all? I felt like this was a bit more challenging. Will it be valued as much? And, I am not sure.

Drew Thompson

I was interested in your treatment of the gaze, the choice not to paint eyes or mouth���features that allow one to identify figures. Here, I was reminded of how American portraitist Amy Sherald uses the painting style grisaille as an identifier of blackness. How did you arrive at this point, this decision not to paint the facial features of certain subjects?

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

That pretty much started with how I started to paint. It was something of an intuitive thing. I wanted to take people and places out of context, and sort of create some universal figuration. It started when I was using historical photographs for my paintings, and I wanted to remove any contextual markers and leave basic information about people. I felt it would assist in people creating their own narratives and identify[ing] with characters that they would not immediately identify with. I have used that technique very deliberately in the ���Heroes��� series of portraits, which I paint in high relief and remove information. But those portraits still need to resemble their subjects. ���Heroes��� [an ongoing series] is about expanding the idea of which names and faces are memorialized. So specific faces play an important part in that. In Gymnasium I could remove even more information, including facial features. This then has brought other ideas into play. The faceless figures have a broader symbolic potential. I am interested in the idea of a black woman standing in as the ���every person.���

Drew Thompson

I know in the ���Heroes��� series you embark on portraiture and the relationship to ID photos in South Africa history. What was it like for you to explore portraiture and painting together���a seemingly different subject matter from design?

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

I stumbled into the portraiture. I was at the Bag Factory [artist studios] at the time, 2012, and as part of a project some of us were involved in, we were given a square canvas to do something on. I looked at the square, and it immediately made me think of ID photos. I started looking around for ID photos that I was interested in. I���d recently watched a film about Thomas Sankara and I was looking for still images of him. I found this picture of him as a cadet, a beautifully washed out, barely in color photograph of him as a young soldier. I decided to use that image as a source for a painting, and once it was done, I realized that this could be a perfect project for me: to begin working on painting people into history���people that I wanted to memorialize. This format would work both formally and metaphorically. This idea of picking up everyone���s ID photo and taking this pretty valueless thing and making it into something that you wanted to keep.

Trials (2020). Oil on canvas 100 x 150cm.

Trials (2020). Oil on canvas 100 x 150cm.Drew Thompson

What kinds of questions of identity and representation surfaced as you were thinking about exhibiting these works?

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

So as the first few portraits leaned against the wall of my studio, I had this feeling that I hadn���t had until then with any other paintings. I felt like I was doing something important for myself, most of all. It was this ���personal pantheon.��� These were people I was thinking about, reading about, dreaming about. So then when these portraits started to find public recognition, particularly when they were chosen to be part of the ���Being There��� exhibition at Foundation Louis Vuitton’s ���Art/Africa, Le nouvel atelier���, it felt strange at first. What were these very personal paintings doing in that space? What do they mean now? Do they lose their original meaning? Are they compromised? I felt torn, in a way. But soon I realized they might be working in another way out there, doing something else now, beyond my studio, beyond me. I liked that visitors to the exhibition in Paris would be asking themselves: Should I recognize this person? Should I learn about that person? That���s where the title of the series also played an important role for me. ���Heroes,��� [but] whose heroes are we talking about? And what is a hero in the first place?

Gymnasium exhibition. Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town and Johannesburg, SA. Credit Nina Liesk.

Gymnasium exhibition. Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town and Johannesburg, SA. Credit Nina Liesk.Drew Thompson

How do you find yourself complicating blackness through color in your paintings?

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

I ask myself this question every time I start mixing browns. Maybe it is something that is still in progress for me. I have these mixes that I use to depict brownness. I have been thinking about the work of Amy Sherald, Meleko Mokogosi, Kerry James Marshall, and others who work in figuration and complicate how to paint black people. I am trying to create a wide range of browns that is close to skin color. I will [often] stand next to my paintings and put a hand out, and say: Am I in there, and are people with darker, richer skin color in there, and are people with lighter skin color in there? Maybe it has to do with my own strange position here in South Africa. I spent my childhood in the United States, where my blackness was not in question in any way. I knew I was black; we did not use the word bi-racial in my house. I knew I was Zulu and Greek and black. And when we came here, to South Africa, suddenly there was this question around my identity���my blackness was constantly questioned, but I was not exactly ���coloured��� either. This inability to be neatly categorized, while also still feeling ���black��� was something that I wrestled with (inwardly and with others) for much of my teenage years. I think that in some ways, the range of skin colors that I���m painting has grown out of that experience. To make sure we are all included in there, in my image of blackness.

June 18, 2020

Access delayed is access denied

Image credit Luis Melendez via Unsplash.

Among the many unsolicited recommendations that African governments are being pelted with presently, those pertaining to patents and the pricing of a potential COVID-19 vaccine are arguably the most expedient. It is certain that the vaccine will arrive in a cocoon of patents which will make it significantly costlier than a generic version.

Even before COVID-19, some health economists argued that low vaccine prices cause shortages. As the global nature of the pandemic guarantees the potential vaccine���s scarcity, such arguments are likely to rationalize high prices, prolonging the access lag for the global south significantly.

Recently, the COVID-19 vaccine donor conference and a pharmaceutical company have been reassuring about the common and public nature of their efforts. However, beyond warm words, and in spite of the Doha Declaration which sought to prevent patent misuse rather than fundamentally question whether or not they should apply, there are currently no political or legal frameworks within the global multilateral trade regime that support these claims. All things remaining equal, COVID-19 presents the perfect opportunity for pharmaceutical companies to reap what they sowed in the 1970s and 1980s, and tested in the late 1990s. However, history also shows that resistance to this kind of nascent necropolitics is not futile.

December 10, 1998: on the steps of the St. George���s Cathedral in Cape Town, a dozen placard-totting comrades gather for a protest. They demand that the South African government develop a comprehensive and affordable treatment plan for all HIV positive South Africans and distribute azidothymidine (AZT) to HIV positive pregnant women to prevent mother to child transmission during childbirth. In a statement afterwards, the fledgling Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) emphasized that the high prices meant that people could not afford the medicine: patents were a key problem in the fight against the epidemic.

TAC is commonly referred to as the most innovative social movement in the 21st century, and its early work was dominated by drug pricing and access-related issues. TAC supported a proposed amendment of the South African Medicines Act to create competition in the medicines market, leading to lower prices. The Act also allowed parallel importation of medicines and made generic substitution of medicines whose patents had expired mandatory.

The activists soon learned that in an unprecedented move backed by the US government, a coalition of around 39 multinational pharmaceutical companies had sued the Mandela government in February 1998 seeking to sabotage the amendment. Deploying protest, shaming and transnational publicity, TAC immediately moved to stop the case, which they deemed an unreasonable attempt to deny South Africans access to affordable HIV treatment.

The global political economy within which the 1997 amendment was to occur was hostile for several reasons. The main one was the agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), part of the then novel World Trade Organization framework that replaced the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs. TRIPS, effective on January 1, 1995, introduced comprehensive international minimum standards for the protection of copyrights, trademarks and patents. All members of the WTO were required to implement these into national law.

The narratives���and possibly, parts of the final agreement���were shaped by pharmaceutical industry associations in the USA from the 1970s until the 1980s. At that time, they advanced a discourse around the importance of intellectual property rights for international trade and framed their violation as a trade issue, proposing sanctions as a solution. Convinced by these arguments, the US government took legal action to protect intellectual property rights worldwide, including in South Africa, where the case dragged on in the courts.

Meanwhile, on an October 1999 trip to Thailand, two TAC activists returned with 3,000 capsules of Biozole���a generic brand of Pfizer���s fluconazole, which is used to prevent and treat candidiasis or fungal infections���in their luggage in violation of both Pfizer’s patent and national law. They confessed this at a press conference the following day after successfully going through customs. For the price of the 3,000 capsules they bought in Thailand, they could only buy 60 capsules of Pfizer’s brand in South Africa. With public opinion in their favor, the authorities pardoned them. They had made their point.

On the day of the court hearing on March 5, 2001, there were protests in thirty countries in response to TAC���s call. TAC had kickstarted the first transnational protest campaign of the 21st century. In Pretoria, five hundred people camped near the court overnight. Just before the hearing (which was promptly adjourned), five thousand people marched on the US Embassy. When the case resumed on April 18, 2001, the plaintiffs requested adjournment and withdrew from the case the next day. With the amended medicines act in sight, the first of many hurdles was out of the way.

A few months later, the new WTO negotiation round���the Doha Round���began. The corresponding ministerial conference adopted the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health in November 2001, addressing some of the issues raised by TAC. In essence, it recognized intellectual property protection���s negative impact on medicine prices, although it was generally considered to promote innovation. Per the declaration, the global south was disproportionately affected, hence the need for the TRIPS to address the issue. It asserted that public health measures ought to take precedence over a restrictive TRIPS interpretation.

But since 1995, and even after the 2005 amendment resulting from the Doha Declaration that strongly encouraged the use of TRIPS flexibilities such as compulsory licensing to ensure access, TRIPS has curtailed rather than incentivized access to medicines in most African countries. This is chiefly because it has legitimized pharmaceutical companies to sell drugs at prices that are out of reach for most African governments and citizens, creating a systemic access problem. On their part, most African countries have often viewed TRIPS flexibilities as a measure of last resort, because the ���least developed country��� transition period, which runs out right when a vaccine is likely to be released (July 2021), still applies. Compulsory licensing is when a state includes in their patent legislation provisions for use of pharmaceutical products without authorization of the patent-holder. It applies particularly for public non-commercial use, in national emergencies or other circumstances of extreme urgency. Consequently, African governments must be assertive in their use of TRIPS flexibilities, as Brazil has repeatedly done, to ensure that Africans have simultaneous or minimum-lag access to the COVID-19 vaccine as it becomes available. To state the obvious, the COVID-19 crisis is the last resort.

COVID-19 and challenges to teacher education in rural Ghana

Image credit Stephan Bachenheimer via Flickr CC.

Ghana recorded its first case of the coronavirus on March 12. By March 16, President Nana Akufo-Addo���s government had put in place a series of measures to slow the spread of the virus in the country. One of these measures was shutting down primary, junior and senior high schools, leaving teachers and parents to deliver alternatives to in-person teaching.

This shutdown presented challenges to Ghana���s vaunted teacher education system. Ghana���s first institution of higher learning was The Presbyterian College of Education, established in 1848. Today, there are 46 public colleges of education across the country working to train Ghana���s next generation of teachers, and that network is widely seen as the backbone of Ghana���s education system.

It is a system that has been working with considerable success toward a series of reforms in recent years. The Ghanaian educational system has historically focused learning on students��� abilities to memorize and reproduce what they learned from memory. But in the last six years, the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the National Council for Tertiary Education (NCTE), via its Transforming Teacher Education and Learning (T-TEL) initiative to train teachers to foster critical thinking, problem solving and creativity in their classrooms. But the disruptions of coronavirus are presenting an additional challenge to the work of bringing a more vital, student-centered pedagogy to Ghanaian schoolchildren.

Like many tertiary institutions in Ghana, colleges of education began emergency online education on April 27, and are working fervently to ensure the success of their e-learning programs. But this is complicated by a number of factors. For example, at the Gambaga College of Education in the North East Region where students usually would walk two kilometers to attend classes due to a lack of housing facilities at the college, online learning has been limited by problems with internet access, poor internet connectivity, and intermittent power outages that disrupt synchronous lessons and sometimes leave damaged electronic gadgets in their wake.

Expenses related to hardware and cellular data are also problems, particularly in rural Ghana where cellular data may be the only way for students to access the internet, and data rates are higher than in countries like Tanzania, Rwanda and Kenya. Students also describe lack of vital equipment such as smartphones. These accessibility issues often make it impossible for students to participate in online lessons or even download course material to learn on their own time. Moreover, economically marginalized students, especially in rural communities, may belong to the digital generation, but that doesn���t always guarantee meaningful exposure to and familiarity with digital technology.

Still, students, educators and other stakeholders are making real efforts to forge ahead despite these difficult circumstances. For example, tutors at the Gambaga College of Education are employing various pedagogical strategies to optimize learning. Madam Raabi Darkon reports that voice recording has been especially helpful. ���When you submit your voice recording,��� she notes, ���the one responding to you will also use voice recording. With voice recording you get to feel the presence more than text messages. If I use voice recording, it���s just like the same as you and I are speaking. I can hear you; you can also hear me.��� This works better for many students, and ���since I���m there to serve them, their choice is what I will follow.��� Another instructor, Meshanu Hamesu Kasimu, reports that training in online teaching from the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences has given him a sense of the relationship between content and platform. ���Before the training, we would take our course material and just cut it and paste. But through the training I got to know that you have to package in a manner that will make it easy for students to read and understand.���

All of these efforts, along with initiatives like T-TEL���s efforts to work with colleges of education in getting smartphones to students that need them, are doing much to respond to this immediate crisis. At the same time, they highlight the infrastructure challenges and inequalities that complicate the work of bringing new pedagogies to Ghanaian learners at all levels. And of course, teacher education only goes so far. For the longest time, trained teachers (graduates of colleges of education) have lamented low salaries and poor remuneration for the services they provide in training Ghana���s future leaders. In teacher circles, there is the running joke that ���the reward of the teacher is in heaven��� since there have not been many efforts to properly address inadequate teacher pay. The innovation and creativity being brought to bear in the Ghanaian teacher education system is laudable. But it will only get us so far until the system provides the resources that students require, and properly compensates educators for their work.

June 17, 2020

Pandemic in the city

Located on Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd between 133rd and 134th Streets, The Shrine Live Music Venue is owned and operated by a Burkinabe who named it after Fela Kuti's Shrine in Lagos. It is a place of social gathering for African immigrants. Image credit Boukary Sawadogo.

These days New York City���s streets see far fewer African immigrants as their lives have come to a halt. For instance, no more young West African immigrants on their electric delivery bikes speeding through traffic; also missing are the buzz of hairdressers busy working in salons, street vendors and stalls dotting 125th Street, and the constant traffic in and out of African restaurants. The space of social gathering for young Burkinabe immigrants on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard between 134th and 133rd streets has become eerily quiet.

At the peak of the crisis, wailing sirens of ambulances often broke the silence in this part of Central Harlem, which is usually bustling with business activities and nightlife. African Uber and taxi drivers became rare in the streets of Harlem and the Bronx from March through May. Though, like many other immigrants and working-class New Yorkers trying to balance health and livelihoods, a few still got behind the wheel for in-demand doorstep grocery delivery services. And, Uber drivers returned to the streets after rearranging the interior of their cars by partitioning them with see-through plastic to maintain physical barriers with backseat passengers. After all, how long can one endure hunger in confinement during Governor Cuomo’s “Pause” executive order?

The francophone West African immigrant enclave in Harlem began to form in the late 1980s and early 1990s when Senegalese, Malians, Nigeriens, and Guineans moved en masse to the neighborhood. Later, in the early 2000s, growing numbers of Burkinabe also came, drawn to the neighborhood���s association with blackness and its historical standing as the mecca of black culture and politics.

West African immigrants have transformed Harlem economically and culturally. Their contributions to the neighborhood are evident from the proliferation of live-music venues, restaurants, stores, places of worship aimed at their various communities. These activities are particularly noticeable around enclaves such as Little Senegal, on 116th Street between Lenox Avenue and Frederick Douglass Boulevard, and what I refer to as Burkina Land on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard between 133rd and 134th streets. Contextualizing West African immigration to Harlem within the larger migratory patterns to the United States, the scholar Zain Abdullah underlines in his book Black Mecca: The African Muslims of Harlem (2010):

While most West African immigrants to the United States have come from English-speaking nations with Christian leanings such as Nigeria and Ghana, the recent surge of African immigrants into Harlem originates in French-speaking countries. As a result of major changes in the US immigration laws of 1965, which allowed an unprecedented arrival of new immigrants from Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa.

In his book Money Has No Smell: The Africanization of New York City (2002), the anthropologist Paul Stoller demonstrated the Africanization of New York through the economic, spatial, and communal presence of African street vendors. These migrants, mostly from francophone West African countries, have successfully navigated the politics of space to establish a presence in Harlem (Malcolm Shabazz Market and Little Senegal) and lower Manhattan (stalls on sidewalks). This is particularly significant for migrants who often have both limited English language command and access to the city���s decision-making circles. The stories of African immigrants in Harlem and across the city are emblematic of a certain resilience and adaptability.

Little Senegal. Image credit Boukary Sawadogo.

Little Senegal. Image credit Boukary Sawadogo.However, this resilience has been stretched to it’s outer limits by the pandemic’s arrival in New York. With hourly shifts in restaurants, cafes, hotels, transportation companies, retail business, and restaurants suddenly vanished, many African immigrants had no income or savings to weather the difficult times.

The 90-day moratorium on residential and commercial eviction proceedings declared by Governor Andrew Cuomo in March���extended for an additional 60 days until August 20th���gave some reprieve regarding housing matters. But this mitigating measure was not helpful for the many African immigrants tripling or quadrupling up in apartments with leases in someone else���s name���often a someone who kept demanding timely rent payments. Thousands of African immigrants in New York found themselves in this situation, and needless to say, social distancing is particularly difficult to maintain in overcrowded apartments.

These realities help explain the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color across the nation. In New York City, for instance, black and Latinx New Yorkers were twice as likely to be hospitalized as whites, and also more likely to die, with African Americans accounting for almost 30 percent of deaths but only 24 percent of the city���s population.

Undocumented immigrants also, bore a disproportionate share of the burden, but their stories remained mostly under the radar of news headlines, and absent from data released by local and state governments. According to the New York Times, it is estimated that there are thousands of undocumented African immigrants in New York. Undocumented immigrants in the US are ineligible for emergency assistance, such as unemployment benefits or the economic impact payments of up to $1200 per individual paid out by the federal government. Yet, these immigrants���mostly low-paid essential workers���form a key part of the labor force that kept New York City running under the stay-at-home order. Many African immigrants in particular work in ���essential��� occupations such as delivery workers, grocery store clerks, cab drivers, cleaners, homecare aides, health care workers, and more, without protection mechanisms such as health insurance.

African Square located on Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd and 125th Street. Image credit Boukary Sawadogo.

African Square located on Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd and 125th Street. Image credit Boukary Sawadogo.The African immigrant communities of New York have been able to remain resilient in the crisis by calling on members to rise up to the challenge that COVID-19 presents. Donations and outreach initiatives by voluntary associations and members of the African community have helped address food insecurity and provide necessary information in order to access healthcare. For instance, the Association of Burkinabe in New York (ABNY) is actively involved in anti-COVID-19 efforts in Burkinabe immigrant communities in the boroughs of Bronx, Manhattan, and Brooklyn. The association has set up a COVID-19 Task Force whose two-pronged role is to connect infected Burkinabe with medical personnel in the community, and to collect donations for weekly distributions to community members who face food insecurity. Since March 29 to present, ABNY has collected $44,902 in monies and in-kind donations that went to 1,800 family beneficiaries. In total, more than 5,000 immigrants have received assistance from ABNY. In addition to community organizations, individual members of the community are volunteering to distribute collected food and to regularly share information on COVID-related resources on social media platforms. However, the tens of thousands of African immigrant residents of upper Manhattan and the Bronx are in dire need of a safety net, beyond solidarity from their own community.

The African immigrant experience in New York City during the COVID-19 crisis should be understood in the larger context of how the crisis has exposed the fault lines in race, class, gender, and immigration status in American society. For Africans, the compounding effects of being an immigrant, whether documented or undocumented, and living in under-resourced neighborhoods, like upper Manhattan and the Bronx, have made them acutely vulnerable in the crisis, facing issues of food insecurity, lack of access to healthcare, and housing instability. This pandemic has laid bare the need for profound socioeconomic changes, including access to information, a reimagined and inclusive public health system, and shared accountability and responsibility to collective well-being beyond any considerations of immigration status. Will we rise to the challenge?

Omar Blondin Diop’s revolution in Senegal

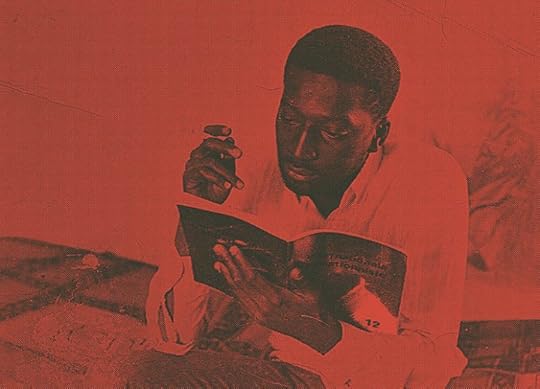

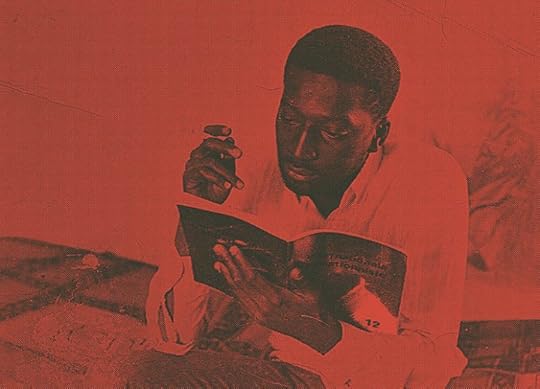

Omar Blondin Diop reading the Internationale situationniste. Image credit Vincent Meessen via Bouba Diallo.

In 2013, the family of Omar Blondin Diop organized a memorial ceremony for him, forty years after his death on the island prison at Gor��e. Centuries before, the island had been a major transit point for ships transporting enslaved African captives to the Americas. As part of the commemoration, Diop���s relatives installed a portrait of him in his former cell, now an exhibit of Senegal���s main historical museum. The picture captured him in 1970 just after he had been expelled from France, where he had been living for a decade. When the photograph was taken, he was a 23-year old student-professor in philosophy. Like many other students at the time, he was swept into the May 1968 protests. But five years later, he was more than a radical dissident���Omar Blondin Diop became a myth. When he died in prison fourteen months into his three-year sentence for ���being a threat to national security,��� authorities in Senegal claimed he committed suicide. Most had good reason to suspect he was murdered. Ever since, his family has tirelessly demanded justice be done, and artists alongside activists have taken the lead in holding on to his memory.

The assassination of Omar Blondin Diop cannot be understood as an isolated incident, but as one tragic episode in a long series of tenacious acts of state-led repression in Senegal. Decolonization in Africa has often been the story of the birth of newly independent states in the 1960s. However, the persistence of foreign interests backed by national governments became a common sight in former French colonies. Well into nominal political independence, burgeoning autocracies largely stifled revolutionary prospects of emancipation from capitalism and imperialism. We don���t often hear of resistance movements in Senegal during L��opold S��dar Senghor���s rule (1960-1980) because his regime successfully marketed the country as ���Africa���s democratic success story.��� Yet, under the single-party rule of the Progressive Senegalese Union, authorities resorted to brutal methods; intimidating, arresting, imprisoning, torturing and killing dissidents. Omar Blondin Diop was one of them.

Omar Blondin Diop was born in the French colony of Niger in 1946. His father, a medical practitioner, had been transferred from Dakar, the administrative capital of French West-Africa, to a small city near Niamey. He did not hold radical positions, but colonial authorities suspected him of anti-French sentiment because of his involvement with trade unionism and support of the socialist French Section of the Workers��� International. The metropole monitored what it labeled ���anti-French elements��� because of their fear of growing anti-colonial movements. Once Blondin Diop���s family was allowed to return to Senegal, he spent the better part of his childhood in Dakar. At the age of 14, he settled in France, where his father enrolled in medical school.

For much of the 1960s, Blondin Diop lived in France. He spent most of his secondary education in Paris, where he attended a prestigious teachers��� college and pursued his study of classical European thinkers, from Aristotle and Kant to Hegel and Rousseau. There, he began frequenting leftist circles. This is a time when anti-capitalist movements in Europe drew inspiration from China���s Cultural Revolution and strongly opposed American military interference in Vietnam. Usually, Africans who pursued activism in France focused on politics from their home countries. Blondin Diop, for his part, had a foot in both worlds. Shortly after hearing about the Senegalese activist, radical filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard selected him to act in the film, La Chinoise (1967). In 1968, the 21-year-old student-professor actively partook in debates organized by far-left groups. Inspired by the writings of Spinoza, Marx, and Fanon, he cultivated theoretical eclecticism���in and out of Situationism, Anarchism, Maoism, and Trotskyism, he never exclusively held onto one given ideology. (You can find clips online.)

Due to his political activities, Blondin Diop was expelled from France to Senegal in late 1969. Alongside other Senegalese comrades who had studied in Europe, he participated in the Movement of Marxist-Leninist Youth. The grouping later gave birth to the influential anti-imperialist front And J��f (To Act Together), suppressed and forced into hiding until the early 1980s. Pushing back against formal structures, Blondin Diop promoted artistic performance. He developed the project of ���a theater in the streets that will address the concerns and interests of the people,��� closely related to Augusto Boal���s ���Theatre of the Oppressed.��� Expanding on art���s revolutionary potential, Blondin Diop wrote:

Our theater will be a collective and active creation. Before playing in a neighborhood, we shall know its inhabitants, to spend time with them, especially the young people […]. Our theater will go to the places where the population gathers (market, cinema, stadium). […] It is especially important that we make whatever we can ourselves. […] Moral conclusion: Better death than slavery.

Independent Senegal was also a neocolonial space. Senghor had initially opposed immediate independence, advocating instead for progressive autonomy over twenty years. So, when he became president, he regularly called upon France���s support. In 1962, Senghor hastily accused his long-time collaborator Mamadou Dia, President of the Senegalese Council of Ministers, of attempting a coup against him���Dia was later arrested and imprisoned for over ten years. (Among others, Dia served as the first Prime Minister of an independent Senegal.) In 1968, when a general strike broke out in Dakar, the police suppressed the movement with the help of French troops. By 1971, Senghor���s embrace of France seemed to reach its peak with the state visit of French president Georges Pompidou, a close friend and former classmate. For over a year, Dakar had been preparing for Pompidou���s 24-hour stay. On the official procession���s main route, authorities rehabilitated roads and buildings, attempting to ���invisibilize��� the city���s poverty.

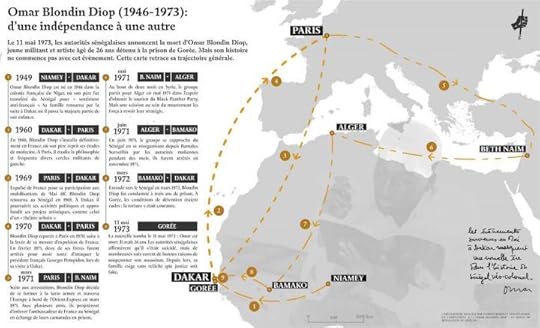

This map retraces Omar Blondin Diop���s main travels (1946-1973). Image credit Florian Bobin and Tristan Bobin (click for larger view).

This map retraces Omar Blondin Diop���s main travels (1946-1973). Image credit Florian Bobin and Tristan Bobin (click for larger view).To young radical activists, Senegal���s reception of the French president was an open provocation. A few weeks prior, a group inspired by the American Black Panther Party and the Uruguayan Tupamaros set fire to the French cultural center in Dakar. During the actual visit, they attempted to charge the presidential motorcade. But they were caught. Among those convicted were two of Blondin Diop���s brothers. He, too, believed in direct action but was not involved in planning this attack. He had returned to Paris a few months earlier, after the lift of his entry ban. Distressed, Blondin Diop decided, with close friends, to leave France to train for armed struggle. Aboard the Orient-Express, they crossed all of Europe by train before arriving in a Syrian camp with Fedayeen Palestinian fighters and Eritrean guerilleros. Their plan was to kidnap the French ambassador to Senegal in exchange for their imprisoned comrades.

Two months into military training, Blondin Diop and his comrades left the desert for the city. They were hoping to garner support from the Black Panther Party, which had briefly opened an international office in Algiers. A split within the movement, however, forced them to reconsider. After swinging by Conakry, Guinea, they moved to Bamako, Mali, where part of Blondin Diop���s family lived. From there, they reorganized.

In Novembre 1971, the police arrested the group days before President Senghor���s first state visit to Mali in over a decade. Intelligence services had been monitoring them for months. In Blondin Diop���s pocket, they found a letter mentioning the group���s plan to free their imprisoned friends. Extradited to Senegal, he was sentenced to three years in prison. For the more significant part of their days at Gor��e, detainees were not allowed to leave their cells. To minimize interaction, experience of daylight was restricted���half an hour in the morning, another half hour in the afternoon. Days became nights, nights were endless, and torture was the norm.

Omar Blondin Diop was reported dead on May 11, 1973. He was 26 years old. The news came as a bombshell. Hundreds of young people stormed the streets and graffitied the capital���s walls: ���Senghor, assassin; They are killing your children, wake up; Assassins, Blondin will live on.��� From the very beginning, the Senegalese state covered up the crime. Going against official orders, the investigating judge started indicting two suspects���he had discovered in the prison���s registry that Blondin Diop had fainted days before the announcement of his death, and the penitentiary administration had done nothing about it. Before the judge had time to arrest a third suspect, authorities replaced him and closed the case. Every May 11 until the 1990s, armed forces would surround Blondin Diop���s grave to prevent any form of public commemoration.

For decades, Omar Blondin Diop has been a source of inspiration for activists and artists in Senegal, and elsewhere. In recent years, exhibitions, paintings and movies have revisited his story, one which sadly resonates with contemporary politics. The authoritarian methods deployed by Senegal���s current administration illustrate how impunity feeds off of the past. President Macky Sall���s regime has repeatedly sought to suppress freedom of demonstration, embezzle public funds, and abuse of its authority. So long as governmental accountability serves no other purpose than an attractive concept to international donors, practices from the past are bound to live on. In Senegal today, people are still imprisoned for demonstrating; activists like Guy Marius Sagna are time and again intimidated, arrested and unlawfully detained. In this context, the state has unsurprisingly refused to reopen Omar Blondin Diop���s case. Nonetheless, as his family���s saying goes, ���no matter how long the night is, the sun always rises.���

Seeking revolution in Senegal

Omar Blondin Diop reading the Internationale situationniste. Image credit Vincent Meessen via Bouba Diallo.

In 2013, the family of Omar Blondin Diop organized a memorial ceremony for him, forty years after his death on the island prison at Gor��e. Centuries before, the island had been a major transit point for ships transporting enslaved African captives to the Americas. As part of the commemoration, Diop���s relatives installed a portrait of him in his former cell, now an exhibit of Senegal���s main historical museum. The picture captured him in 1970 just after he had been expelled from France, where he had been living for a decade. When the photograph was taken, he was a 23-year old student-professor in philosophy. Like many other students at the time, he was swept into the May 1968 protests. But five years later, he was more than a radical dissident���Omar Blondin Diop became a myth. When he died in prison fourteen months into his three-year sentence for ���being a threat to national security,��� authorities in Senegal claimed he committed suicide. Most had good reason to suspect he was murdered. Ever since, his family has tirelessly demanded justice be done, and artists alongside activists have taken the lead in holding on to his memory.

The assassination of Omar Blondin Diop cannot be understood as an isolated incident, but as one tragic episode in a long series of tenacious acts of state-led repression in Senegal. Decolonization in Africa has often been the story of the birth of newly independent states in the 1960s. However, the persistence of foreign interests backed by national governments became a common sight in former French colonies. Well into nominal political independence, burgeoning autocracies largely stifled revolutionary prospects of emancipation from capitalism and imperialism. We don���t often hear of resistance movements in Senegal during L��opold S��dar Senghor���s rule (1960-1980) because his regime successfully marketed the country as ���Africa���s democratic success story.��� Yet, under the single-party rule of the Progressive Senegalese Union, authorities resorted to brutal methods; intimidating, arresting, imprisoning, torturing and killing dissidents. Omar Blondin Diop was one of them.

Omar Blondin Diop was born in the French colony of Niger in 1946. His father, a medical practitioner, had been transferred from Dakar, the administrative capital of French West-Africa, to a small city near Niamey. He did not hold radical positions, but colonial authorities suspected him of anti-French sentiment because of his involvement with trade unionism and support of the socialist French Section of the Workers��� International. The metropole monitored what it labeled ���anti-French elements��� because of their fear of growing anti-colonial movements. Once Blondin Diop���s family was allowed to return to Senegal, he spent the better part of his childhood in Dakar. At the age of 14, he settled in France, where his father enrolled in medical school.

For much of the 1960s, Blondin Diop lived in France. He spent most of his secondary education in Paris, where he attended a prestigious teachers��� college and pursued his study of classical European thinkers, from Aristotle and Kant to Hegel and Rousseau. There, he began frequenting leftist circles. This is a time when anti-capitalist movements in Europe drew inspiration from China���s Cultural Revolution and strongly opposed American military interference in Vietnam. Usually, Africans who pursued activism in France focused on politics from their home countries. Blondin Diop, for his part, had a foot in both worlds. Shortly after hearing about the Senegalese activist, radical filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard selected him to act in the film, La Chinoise (1967). In 1968, the 21-year-old student-professor actively partook in debates organized by far-left groups. Inspired by the writings of Spinoza, Marx, and Fanon, he cultivated theoretical eclecticism���in and out of Situationism, Anarchism, Maoism, and Trotskyism, he never exclusively held onto one given ideology. (You can find clips online.)

Due to his political activities, Blondin Diop was expelled from France to Senegal in late 1969. Alongside other Senegalese comrades who had studied in Europe, he participated in the Movement of Marxist-Leninist Youth. The grouping later gave birth to the influential anti-imperialist front And J��f (To Act Together), suppressed and forced into hiding until the early 1980s. Pushing back against formal structures, Blondin Diop promoted artistic performance. He developed the project of ���a theater in the streets that will address the concerns and interests of the people,��� closely related to Augusto Boal���s ���Theatre of the Oppressed.��� Expanding on art���s revolutionary potential, Blondin Diop wrote:

Our theater will be a collective and active creation. Before playing in a neighborhood, we shall know its inhabitants, to spend time with them, especially the young people […]. Our theater will go to the places where the population gathers (market, cinema, stadium). […] It is especially important that we make whatever we can ourselves. […] Moral conclusion: Better death than slavery.

Independent Senegal was also a neocolonial space. Senghor had initially opposed immediate independence, advocating instead for progressive autonomy over twenty years. So, when he became president, he regularly called upon France���s support. In 1962, Senghor hastily accused his long-time collaborator Mamadou Dia, President of the Senegalese Council of Ministers, of attempting a coup against him���Dia was later arrested and imprisoned for over ten years. (Among others, Dia served as the first Prime Minister of an independent Senegal.) In 1968, when a general strike broke out in Dakar, the police suppressed the movement with the help of French troops. By 1971, Senghor���s embrace of France seemed to reach its peak with the state visit of French president Georges Pompidou, a close friend and former classmate. For over a year, Dakar had been preparing for Pompidou���s 24-hour stay. On the official procession���s main route, authorities rehabilitated roads and buildings, attempting to ���invisibilize��� the city���s poverty.

This map retraces Omar Blondin Diop���s main travels (1946-1973). Image credit Florian Bobin and Tristan Bobin.

This map retraces Omar Blondin Diop���s main travels (1946-1973). Image credit Florian Bobin and Tristan Bobin.To young radical activists, Senegal���s reception of the French president was an open provocation. A few weeks prior, a group inspired by the American Black Panther Party and the Uruguayan Tupamaros set fire to the French cultural center in Dakar. During the actual visit, they attempted to charge the presidential motorcade. But they were caught. Among those convicted were two of Blondin Diop���s brothers. He, too, believed in direct action but was not involved in planning this attack. He had returned to Paris a few months earlier, after the lift of his entry ban. Distressed, Blondin Diop decided, with close friends, to leave France to train for armed struggle. Aboard the Orient-Express, they crossed all of Europe by train before arriving in a Syrian camp with Fedayeen Palestinian fighters and Eritrean guerilleros. Their plan was to kidnap the French ambassador to Senegal in exchange for their imprisoned comrades.

Two months into military training, Blondin Diop and his comrades left the desert for the city. They were hoping to garner support from the Black Panther Party, which had briefly opened an international office in Algiers. A split within the movement, however, forced them to reconsider. After swinging by Conakry, Guinea, they moved to Bamako, Mali, where part of Blondin Diop���s family lived. From there, they reorganized.

In Novembre 1971, the police arrested the group days before President Senghor���s first state visit to Mali in over a decade. Intelligence services had been monitoring them for months. In Blondin Diop���s pocket, they found a letter mentioning the group���s plan to free their imprisoned friends. Extradited to Senegal, he was sentenced to three years in prison. For the more significant part of their days at Gor��e, detainees were not allowed to leave their cells. To minimize interaction, experience of daylight was restricted���half an hour in the morning, another half hour in the afternoon. Days became nights, nights were endless, and torture was the norm.

Omar Blondin Diop was reported dead on May 11, 1973. He was 26 years old. The news came as a bombshell. Hundreds of young people stormed the streets and graffitied the capital���s walls: ���Senghor, assassin; They are killing your children, wake up; Assassins, Blondin will live on.��� From the very beginning, the Senegalese state covered up the crime. Going against official orders, the investigating judge started indicting two suspects���he had discovered in the prison���s registry that Blondin Diop had fainted days before the announcement of his death, and the penitentiary administration had done nothing about it. Before the judge had time to arrest a third suspect, authorities replaced him and closed the case. Every May 11 until the 1990s, armed forces would surround Blondin Diop���s grave to prevent any form of public commemoration.

For decades, Omar Blondin Diop has been a source of inspiration for activists and artists in Senegal, and elsewhere. In recent years, exhibitions, paintings and movies have revisited his story, one which sadly resonates with contemporary politics. The authoritarian methods deployed by Senegal���s current administration illustrate how impunity feeds off of the past. President Macky Sall���s regime has repeatedly sought to suppress freedom of demonstration, embezzle public funds, and abuse of its authority. So long as governmental accountability serves no other purpose than an attractive concept to international donors, practices from the past are bound to live on. In Senegal today, people are still imprisoned for demonstrating; activists like Guy Marius Sagna are time and again intimidated, arrested and unlawfully detained. In this context, the state has unsurprisingly refused to reopen Omar Blondin Diop���s case. Nonetheless, as his family���s saying goes, ���no matter how long the night is, the sun always rises.���

June 16, 2020

The universal right to breathe

People leaving Antananarivo, Madagascar during the COVID-19 pandemic. Image credit Henitsoa Rafalia for the World Bank via Flickr CC.

Already some people are talking about ���post-COVID-19.��� And why should they not? Even if, for most of us, especially those in parts of the world where health care systems have been devastated by years of organized neglect, the worst is yet to come. With no hospital beds, no respirators, no mass testing, no masks nor disinfectants nor arrangements for placing those who are infected in quarantine, unfortunately, many will not pass through the eye of the needle.