Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 169

June 25, 2020

The myth of sustainable jobs in extractives

Image credit Sara Geenen.

Despite extractive industries��� lousy reputation as major polluters, human rights violators, and instigators of social and political conflicts, many observers remain remarkably optimistic, or at least pragmatic, about the potential for mining to create jobs in poor countries. Instead of looking at alternatives to ween the world off extractives���degrowth, disinvestment, recycling���international organizations, governments, and (most obviously) the private sector have doubled-down, emphasizing that mining can actually contribute to achieving the SDGs (specifically SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth).

According to organizations like the ILO, the World Bank, UNCTAD and UNDP, mining is an important source of job creation. Obviously, these jobs will not fall out of the sky, hence we see a general push for local content and local economic diversification policies, which will, allegedly, stimulate domestic linkages and create jobs. And not just any jobs, but decent ones: jobs that afford dignity, security, a sufficient living wage.

Yet perhaps the optimism for “decent” and “sustainable” jobs in extractives should be tempered, especially in low-income African countries. Recent research, e.g. Sara Geenen���s work in Ghana and DRC (part of which has been published here) and Diana Ayeh���s work in Burkina Faso, suggest that local content policies do not provide a quick-fix to the problem of domestic linkages, nor do they necessarily create decent jobs in extractive industries.

Geenen���s research, in particular, draws attention to the fact that such polices are implemented in complex political arenas, where power-holders use them as political instruments to accumulate profits and control rents. Direct and indirect employment are managed by labor brokers: chiefs, community elders, and members of community forums, but also staff of human resources departments, high-ranking people from the parent company, and managers from subcontracting companies, all of whom jostle to arrange employment for their own “clients.”

While these clientelist practices do involve a certain degree of redistribution (via access to jobs), they also inhibit social mobility and structural change, since these are typically precarious, low-wage jobs���a far cry from the “decent” work envisioned by the ILO. This points toward Barchiesi���s observation that the ideal of decent work is all too often subsumed by the actually-existing practice of workers accepting bad jobs as better than no jobs at all.

In 2017-2018, Geenen conducted a survey with 223 Congolese and 226 Ghanaian workers. These individuals may work alongside others directly employed by multinational companies, but are themselves employed through third-party subcontractors (a strategy which, along with hiring for 22-day periods, absolves multinationals of contractual obligations, while also blurring the traditional distinction between direct and indirect jobs).

Not surprisingly, our analysis of this data shows that there is significant variation in both employment stability and wages depending on whether someone works directly for the multinational (better conditions), or indirectly via a foreign or domestic subcontractor (worse conditions). Of course, pay scales can vary across different job titles, but we find that even in cases where workers have the same job title and perform the same work, discrepancies persist. As one Congolese worker lamented: ���We do the same job, working shoulder by shoulder all day long, but at the end of the day he gets a bonus and I don���t.���

A more novel finding is that even within the pool of subcontracted workers, there exists a benefits gap between those working for foreign vs. domestic subcontractors. In the DRC, a mere 3% of the surveyed workers working for domestic subcontractors��� primarily labor-hire firms owned by local elites���have a permanent contract, whereas 30% of those working for foreign subcontractors do. Monthly earnings also vary: the former earn 206 USD/month, the latter 228 USD/month. In the Ghanaian case, we find greater employment stability ���65% of those working for domestic subcontractors and 81% of those working for foreign subcontractors have permanent contracts���but an even more remarkable difference in monthly wages: 169 USD vs. 224 USD, respectively.

Admittedly, the wage differentials could also reflect different job categories���domestic subcontractors may be more likely to be tasked with hiring for positions that pay less across all sectors (e.g. jobs that no do not require special credentials such as a license to operate heavy machinery, etc.), something we will parse in future analysis. However, while this might explain the comparatively lower wages, it does not explain the substantial difference we see in the relative lack of contract stability among those employed by domestic subcontractors. The stability implied by the decent work agenda is intended to apply to all forms of waged work, not just “privileged” categories.

Worse, these contractual hierarchies transcend paychecks, creating new forms of social marginalization and exclusion. ���There is a company bus transporting workers from the site to the city,��� another worker explained, ���but there is a category of sans papiers: the subcontracted workers. Even when they already boarded��[the bus], when company workers show up, sans papiers need to back off.��� Almost all subcontracted workers mentioned how this affects their dignity: not having a contract, in their view (and, apparently, the view of their colleagues with contracts), is not having a job.

Questions of dignity are not peripheral: while we may critique the overwhelming and often debasing centrality of wage work in late capitalist economies, we can still acknowledge that work is often a source of pride and self-esteem, particularly in social contexts where an important aspect of performing masculinity is demonstrating one���s ability to earn. And, it foregrounds questions of how labor is systematically devalued through somewhat arbitrary distinctions between what, precisely, constitutes skilled vs. unskilled labor.

For the subcontracted workers, then, these forms of wage-work hardly constitute the ���decent��� jobs policymakers hoped local content mandates would create. Multinationals offload as many responsibilities as possible on to both foreign and domestic subcontractors, the latter of which (owned by local elites) offer the least stability and lowest wages. This is not inclusion, but adverse incorporation.

Our data also supports Tania Li���s sobering observation that those who have been dispossessed of their lands and livelihoods are typically not included in the capitalist project, not even as low-paid, casual workers: of the 223 workers surveyed in the DRC, only 47 previously counted artisanal mining as their principal occupation, while an estimated 12,000 artisanal miners have been chased from their work areas in these same concessions. In the Ghanaian sample there were only 2 (out of 226).

Has the mining industry created jobs? Yes. But too many of these are precarious, low paid jobs. And, as seen especially in the DCR case study, the industry has simultaneously eliminated a staggering amount of already-existing jobs.

It is time to question shibboleths about extractive industries leading the way to development through job creation, linkages and local content. Clientelist practices and precarious jobs hold little potential for structural transformations at the bottom of the global production network; instead they create new inequalities, as some groups are adversely incorporated, while others are marginalized and excluded from the extractivist project all together.

Born from the soil

Zimplats handing over equipment to a rural district council. Image credit Darryl Chanakira.

The fact that mining in sub-Saharan Africa largely occurs in rural areas has often engendered conflicts between large-scale mining companies and indigenous people. In these areas, traditional chiefs lay ancestral claims to the land. These chiefs, being custodians of the land, are consequently at the center of the conflicts between mining companies and local communities affected by mining operations. Therefore, mining companies are increasingly being forced to forge alliances with these chiefs and making them play a key role in the recruitment of local labor. Such has been the case between Zimbabwe Platinum Mines (Zimplats), traditional chiefs and the local Mhondoro-Ngezi community in which Zimplats operates.

The Zimplats context resulted in the establishment of a local labor recruitment regime centered on chiefs��� and job-seekers��� claims of autochthony (meaning ���born from the soil���). The notion of being born of the soil, as Geschiere argues, is a powerful mobilizing force against perceived ���outsiders.��� As custodians of the land (from which locals claim to be born from), Mhondoro-Ngezi chiefs have the task of articulating the grievances of the local communities who are displaced from their land to pave the way to mining operations and bear the brunt of the environmental and social impacts of mineral extractions.

In the Mhondoro-Ngezi case, since the mining claims which Zimplats sought to exploit were located within an area under the control of traditional leaders, the company had to work closely with the chiefs who claimed autochthonous belonging to the area in order to avoid any conflicts. It is against this background that in 1999 Chief Ngezi conducted a traditional ceremony at Mulota Hills to appease the spirits of his ancestors and grant his consent for the commencement of mining operations in his area. The ceremony also served the purpose of affirming the chief���s authority as the custodian of the land on which Zimplats was about to commence its mining operations and also to forestall any similar claims by rival traditional leaders. Ngezi asserted his autochthonous belonging to the area by claiming that his ancestors were buried in the Mulota Hills. By claiming the presence of ancestral graves at the Mulota hills, Chief Ngezi was making claims to the land and through it the platinum resources beneath it. Such claims were later used by the Chief to negotiate for jobs and to mediate the labor recruitment process.

Mhondoro-Ngezi is divided amongst three Chiefs���Ngezi, Nyika and Benhura���and the three used their claims to autochthony to establish close ties with Zimplats and to demand access to jobs for people in their areas of jurisdiction. This was based on the fact that they lost their ancestral lands to mining operations and were thereby entitled to preferential access to jobs. Failure to establish a recruitment regime premised on this preferential access to jobs for locals would anger the ancestor and cause accidents disruptive to the mining operations.

Zimplats ceded to these demands and it gave the three main chiefs in Mhondoro-Ngezi the authority to register the names of job-seekers from their areas of jurisdiction, and forward them to the company���s human resources department for recruitment. Zimplats’ local labor recruitment regime, therefore, accentuated the power and influence of chiefs in the area.

The waiting lists contained jobs-seekers��� personal details such as name, age, gender, national registration number and village of origin. (The national registration number contains the number which indicates the holder’s district of origin as well as the village they hail from.) Such details can be used to expose outsiders who would usually have to rely on the support of chiefs to have their names registered on the community job-seekers waiting list.

Although Zimplats labor recruitment regime seems to have benefitted the locals affected by the mining operations, the system has had a number of challenges. The case of Chief Nyika, one of the three main chiefs in the Mhondoro-Ngezi area, encapsulates the fraught nature of the community labor recruitment regime managed by traditional leaders.

Chief Nyika is visually impaired, as a result of this impairment, he relies on the assistance of his aides and grandchildren who also managed the job-seekers��� waiting lists from his area. However, it is alleged that the chief���s grandchildren would receive bribes from job-seekers from areas beyond Mhondoro-Ngezi and add their names to the list they would submit to Zimplats. Some job-seekers offered cash and livestock to have their names registered on the community job-seekers waiting list. The manipulation of this labor recruitment regime by chiefs and their aides even today causes a lot of disquiet among locals who complain that outsiders are getting jobs ahead of them.

Although traditional leaders��� manipulation of the local labor recruitment regime generated tensions, the high rate of unemployment played a critical role in engendering the conflicts. Zimbabwe���s economic crisis and the high unemployment rates it created made it difficult for unskilled locals to get access to jobs. A corollary to this was the increasing tensions between local job-seekers and traditional leaders. Rumors about how outsiders were working in cahoots with local chiefs and Zimplats recruitment officers to beat the system also further accentuated the tensions. In addition, the ruling ZANU PF party politicians also submitted their own lists of job-seekers who were usually members of the party���s youth wing. Zimplats accepted the lists from the politicians to avoid tensions.

Faced with the challenges of getting access to jobs generated by the fraught labor recruitment regime, local communities often resort to community protests to get more concessions from the mining company. One such protest broke out in May 2005. The community job-seekers protest was organized by Morgan Mupamombe, a member of the Ngezi chiefly family who had submitted his name for several years but to no avail.

What is apparent is that autochthony is one of the most important tools deployed by local communities in their struggles to access jobs and other resources from the mining company. When it was reported in 2012 that Zimplats��� Bimha Mine was experiencing some structural challenges which rendered it unsafe, local community leaders interpreted it as a sign that their ancestors were not happy. Consequently, when the mine collapsed in June 2014, leading to its closure, the community leaders felt vindicated and they linked the collapse to the anger of their ancestors against mining operations. The community leaders argued that practices such as the desecration of ancestral graves and other sacred places through the mining activities as well as the failure by the mining company to provide locals with jobs were making the ancestors angry.

Although Zimplats proffered a scientific explanation for the collapse of Bimha mine and refused to consider the spiritual explanations which they locals were circulating, the fact that locals believed that there were connections between mine accidents and the anger of their ancestral spirits concerned them. Consequently, in 2014 the company acceded to the demands of the community to conduct another traditional ceremony to appease the ancestral spirits of the area.

Although the mining company did not publicly admit to having initiated this traditional ceremony, what is evident is that it was keen to ensure that their mining operations would not be disturbed by community protests or rumor about mine accidents being caused by angry ancestral spirits.

June 24, 2020

Towards a neoliberal labor regime?

The Central African Copperbelt has long been dominated by large companies, the G��camines in Congo and the ZCCM in Zambia. Since the 1920s, these companies progressively developed a paternalistic labor regime that covered every aspect of their workers��� lives. Since the early 2000s, following the liberalization of the mining sector in both countries and the upsurge of copper prices, companies of different sizes and origins���including American majors, Chinese state-owned enterprises, Swiss commodity trading companies and junior companies from Canada, Australia and South Africa���have flocked to Central Africa to take over G��camines and ZCCM assets and start new mining and industrial projects. Currently, there are about thirty mining projects found in operation in the region. Together, they produce more than two million tons of copper per year���a figure that will increase in the forthcoming years when new projects in the Congo will start production.

Building on the results of the WORKinMINING project, a research project funded by the European Research Council on the micropolitics of work in the mining companies of central Africa, this blogpost aims to share general thoughts about the changes that these new investors have brought to labor. Three general trends in their labor practices are worth noting here:

The new investors claim to break with the paternalism of the past, to focus on their core business���copper production. Those among them who bought mining and industrial assets from G��camines or ZCCM did not take over their housing estates and social infrastructure. When social benefits are prescribed by law, they are generally converted into cash allowances or provided by subcontractors.

Mining companies in the 21st century outsource a much larger range of activities to subcontractors than the state-owned enterprises of the past. Far from being limited to secondary activities such as catering, transport, cleaning, or security services, this practice includes core operations of a mine, including mining or maintenance. Today, between 40 and 60% of the people working on mine sites in Congo and Zambia are contract workers, who tend to have lower wages and fewer benefits than direct workers.

Direct jobs in the mining sector are fewer and more precarious than in the past. Mining companies do not hesitate to organize mass lay-offs to respond to market pressures, most especially in Zambia, where production costs in the old underground mines are higher and the government more vulnerable to pressure on employment numbers.

Together, these trends point to the emergence of what we could call a ���neoliberal��� labor regime. Far from being specific to the Central African Copperbelt, this labor regime can be found to varying degrees in new mining projects all over the world. However, analyzing new investors��� labor practices as the manifestation of a broader neoliberal labor regime risks to overlook the diversity of mining projects characteristic of the recent boom. The comparison between various mining projects in the Central African Copperbelt suggests that, for each trend highlighted above, their labor practices show important variations depending of the type of capital involved (i.e. state vs. private), the area where they are established (i.e. rural vs. urban), and the type of mine being developed (i.e. underground vs. surface). Some investors have taken over existing social infrastructure, or built new company towns. Other companies provide relatively stable jobs to a predominantly permanent workforce.

In addition, an approach focusing on the neoliberal dimension of new mining investors��� labor practices excludes how they are negotiated by various categories of actors locally: HR managers, labor officials, trade unions, customary chiefs, etc. Developing a mining project does not fall within the perfectly controlled implementation of a rational plan: it is a complex process of improvisation and adaptation giving rise to various forms of mobilization, translation and resistance. Having said this, specific case studies developed in the WORKinMINING project indicate that the negotiation margin for the local actors mentioned above varies from one company to another, and tends to shrink with the development of mining projects.

The various categories of actors who contribute to shape mining companies��� labor practices also participate, in doing so, to the transformation of broader power configurations in Congo and Zambia. The WORKinMINING project focused on union politics, gender dynamics, the segmentation of the labor market, and the rise of identity politics. Generally speaking, the analysis suggests that, even though new mining projects have not fundamentally changed existing power configurations, they favored the emergence of new practices and discourses, increased social inequalities, and fueled union and political competition. This competition, however, does not develop along the same lines in Congo and Zambia. For various reasons, labor has been a more important political issue in Zambia than in the Congo.

Highlighting the diversity of mining projects and the complexity of the power games involved in the implementation of new labor practices does not necessarily prevent to see the labor regime currently emerging in Congo and Zambia as ���neoliberal.��� After all, the broader trends associated with this regime are present in both copperbelts, and they have considerably changed the rules of the game. Neoliberalism is best conceived as a Weberian ideal-type, a set of general characteristics which serve as an abstract starting point for comparing the micropolitics involved in the making of labor practices in different mining projects.

Decolonizing the vaccine

Image credit the State of S��o Paulo via Flickr CC.

Reflecting on a potential COVID-19 vaccine trial during a television interview in April, a French doctor stated, ���If I can be provocative, shouldn���t we be doing this study in Africa, where there are no masks, no treatments, no resuscitation?��� These remarks reflect a colonial view of Africa, reinforcing the idea that Africans are non-humans whose black bodies can be experimented on.

This colonial perspective is also clearly articulated in the alliance between France, The Netherlands, Germany and Italy to negotiate priority access to the COVID-19 vaccine for themselves and the rest of Europe. In the Dutch government���s announcement of the European vaccine coalition, they indicate that, ������ the alliance is also working to make a portion of vaccines available to low-income countries, including in Africa.���

In the collective imagination of these European nations, Africa is portrayed as a site of redemption���a place where you can absolve yourself from the sins of ���vaccine sovereignty,��� by offering a ���portion of the vaccines��� to the continent. Vaccine sovereignty reflects how European and American governments use public funding, supported by the pharmaceutical industry and research universities, to obtain priority access to potential COVID-19 vaccines. The concept symbolizes the COVID-19 vaccine (when it eventually becomes available) as an instrument of power deployed to exercise control over who will live and who must die.

In order to counter vaccine sovereignty, we must decolonize the vaccine. Africans have a particular role to play in leading this decolonization process as subjects of colonialism and as objects of domination through coloniality. Colonialism, as an expansion of territorial dominance, and coloniality, as the continued expression of Western imperialism after colonization, play out in the vaccine development space, most notably on the African continent.

So what does decolonizing the vaccine look like? And how do we decolonize something that does not yet exist? For Frantz Fanon, ���Decolonization, which sets out to change the order of the world, is, obviously, a program of complete disorder.���

Acknowledging that the COVID-19 vaccine has been weaponized as an instrument of power by wealthy nations, decolonization requires a Fanonian program of radical re-ordering. In the context of vaccine sovereignty, this re-ordering necessitates the dismantling of the profit-driven biomedical system.

This program starts with de-linking from Euro-American constructions of knowledge and power that reinforce vaccine sovereignty through the profit-driven biomedical system. Advocacy campaigns such as the ���People���s Vaccine���, which calls for guaranteed free access to COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostics and treatments to everyone, everywhere, are a good start. Other mechanisms, such as the World Health Organization���s COVID-19 Technology Access Pool, similarly supports universal access to COVID-19 health technologies as global public goods.

Since less than 1% of vaccines consumed in Africa are manufactured on the continent, regional efforts to develop vaccine manufacturing capacity such as those led by the Africa Center for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as the Alliance of African Research Universities, must be supported. These efforts collectively advance delinking and move us closer toward the re-ordering of systems of power.

The opportunity for disorder is paradoxically enabled by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has permitted moments of existential reflection in the midst of the crisis. A few months ago, a press release announcing the distribution of ���a portion of the vaccines��� to Africans, may have been lauded as European benevolence. But in the context of a pandemic that is more likely to kill black people, Africa���s reliance on Europe for vaccine handouts is untenable, necessitating a re-examination of the systems of power that hold this colonial relationship in place.

The Black African body appears to be good enough to be experimented on, but not worthy of receiving simultaneous access to the COVID-19 vaccine as Europeans. Consequently, Africans continue to feel the effects of colonialism and white supremacy, and understand the pernicious nature of European altruism.

By reinforcing the current system of vaccine research, development and manufacturing, it has become apparent that European governments want to retain their colonial power over life and death in Africa through the COVID-19 vaccine.

Resistance to this colonial power requires the decolonization of the vaccine.

June 23, 2020

A politics of nuisance

Still from Softie.

���There are pigs in the streets.���

���What?���

���There are pigs and blood all over the streets.���

Sitting in the Kenya National Archives in downtown Nairobi, it is common to hear a certain amount of commotion: preachers, healers hawking the latest cure, political rallies. I even recall a bomb scare that kept us holed up for a few hours for what turned out to be two small explosive devices set off in the busses that converge in front of the Archives. But this was a first: in 2013, hundreds of people gathered in the streets in front of Parliament as pigs branded with graffiti targeting ���MP��� greed (for Member of Parliament) and covered in blood were released to protest government corruption. It was an iconic moment, perfectly orchestrated for the social media era under the #OccupyParliament hashtag with emerging political activist and well-known photojournalist Boniface Mwangi as conductor. The story was picked up worldwide, where reporters were quick to note that MPs in Kenya were some of the highest paid in the world (second relative to GDP, according to the Economist in 2013, and still 40 times the average wage in Kenya after a 15% cut in 2017). Riot police fired tear gas and arrested the leaders.

Softie, a new documentary from filmmaker Sam Soko, opens with a montage of elusive figures buzzing around in the night: making deals, buying blood, chasing down pigs among heaps of garbage, and painting the mud-covered swine, all to a pulsating Afrofunk soundtrack, as if harkening back to another era in African politics in the late 1960s and 70s when art and protest were deeply entwined. ���Softie��� is Boniface Mwangi. As the title card bursts on screen, we see Boniface, arms raised, standing in front of a tank, just under a rainbow of tear gas aimed indiscriminately at the crowd of peaceful protestors and onlookers. ���Ng���ong���a wa Mwanjalo������a 1970s East African classic by Nashil Pichen and the Eagles Lupopo���announces ���Softie������the film and the man���with an infectious beat, reminiscent of the late Manu Dibango���s classic soundtrack and final, defiant shot from Ousmane Sembene���s iconic film Ceddo, and a fitting lyrical cue: ���Ng���ong���a,��� a fly that buzzes around filth; sign of contempt; a nuisance that needs to be stopped.

Still from Softie.

Still from Softie.COVID-19 may have interrupted the release schedule of Softie, but the global crisis has, in some ways, made the film���s message even more urgent and relevant, connected to a global, though also intensely local, struggle.

Boniface first rose to prominence as a photojournalist after the 2007 Kenya elections when he was assigned to cover the post-election violence that engulfed the country for two months and left over 1,000 people dead and several hundreds of thousands internally displaced. Twice earning him the distinction of CNN African Photojournalist of the year, Boniface���s photographs of the violence put faces to the trauma and forced viewers to confront the culture of impunity in its aftermath. In 2008-2009, a traveling public exhibit of the photographs entitled ���Picha Mtani��� encouraged Kenyans to interact with the photographs and tell their own stories and became the site of protests. These early scenes in the film capture the energy, immediacy and power of images to shake public consciousness, with viewers literally tearing down the images, sharing stories, and confronting their shared trauma. Producer Toni Kamau remembers interviewing a man during the exhibit who was living in an Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp. Having never spoken before of his experiences, he related his personal history of being a squatter in Nakuru and having his house burned down in the violence, forcing him and his wife to move into the camps with his mother, which for a Kikuyu man was devastating: ���I am not even a man��� next time, I am the one who is going to have a panga [machete].��� It is this cyclical process of elections and violence, hope and corruption, that drives the film, as much as Boniface���s own story.

Softie, which started as an activist manual conceived in the artist/activist collective PAWA-254, takes us on a ten-year journey through Kenya���s recent history from the 2007 elections navigating through elections, wide-spread violence, ICC court cases, protests, deaths, commissions and finally Boniface���s decision to run for office in 2017. His was a people���s campaign, revolutionary in many ways: innovating new fundraising techniques, avoiding the trappings of ���tribal��� or party politics, prioritizing policy and grassroots mobilization. There was at the moment a certain excitement building around the possibility of a generational shift���with the election of Bobi Wine in Uganda and the emergence of activists like Alaa Salah in Sudan among others. His opponent, the flashy musician-turned-politician Jaguar, however, had the backing of the ruling party and patronage to distribute. Death threats that had dogged Boniface���s activism for the past few years escalated and began to extend to his family. The 2017 election was fraught, from the torture and murder of a top election official a week before the election to serious charges of voter tampering that led the Supreme Court of Kenya to nullify the results. But Boniface���s loss was felt immediately, and the film captures the deep sense of ambivalence, aimlessness and futility felt by many.

Still from Softie.

Still from Softie.In his 2015 TED talk, Boniface tells the story of transforming from his youthful persona, ���Softie,��� into a troublemaker, a rebel often standing alone in protest against a corrupt system. With this film, audiences are given a glimpse inside this seeming contradiction: Boniface the tireless, isolated and tormented crusader and Boniface the ���Softie������husband, father, son, neighbor. It is these two scales���one sweeping, fast-paced, full of energy and dangerous, and the other more intimate, slow, and quiet ���that humanize the struggle and make this film so unique and compelling. The photos of the spectacular violence and trauma of 2007-8 are intercut, in life and in the film, with shots of Boniface���s wedding and birth of his first son; pain and joy entangled. The film seamlessly blends an epic political thriller with an intimate family portrait. Nairobi is beautifully captured, saturated in all of its layers, colors and vibrancy while the space of the home provides a sanctuary and sense of play, hope and normalcy. Njeri, Boniface���s wife, becomes an important counter-balance, with carefully chosen words (���I���ve given my children my life, but you���ve given your country your life���), pregnant looks (her silent but piercing reaction to his announcement that he will run for office), and emotional personal asides that remind the viewer that every decision Boniface makes impacts and implicates their family. Nation and family, at odds for Boniface���s love, attention and commitment. And this tension remains until the last frames: Boniface alone on the dark streets of Nairobi after losing his electoral campaign; Boniface alone with his family, smiling into an uncertain future.

It is clear that filmmaker Sam Soko developed not only a close and trusted relationship with the Mwangi family, but also a deliberate approach to the relationship between art and activism: political commitment, comradery and friendship bleed into the film���s fabric. Soko also sees the film as reaching ���beyond Boniface.��� At one point, Boniface laments how one���s very name identifies and betrays you in Kenya���s ethnic politics, seeds planted by colonialism but nurtured and allowed to grow during the postcolonial period as the film thoughtfully illustrates. Soko aimed to center Kenyans as a character: ���This film has to be for Kenyans, for that person that actually wakes up at 5AM goes to vote. That person has to see themselves.��� Kenyan producer Toni Kamau, for her part, has turned her attention to how to get the film out there in the midst of global shutdowns, most importantly for Kenyan audiences, which will take navigating not only the restrictions of the crisis but also the Kenya Film Classification Board, who���ve recently demonstrated the lengths they are willing go to in order to keep certain kinds of content off Kenyan screens: ���when people watch this film, it���s going to open so many wounds. We are not a country that likes to talk about our history, especially when it���s painful, even from independence.��� While filled with a rich tapestry of music, graffiti art and creative protests as backdrop to the stories of its compelling characters, the film is also brave and unflinching in speaking what is so often whispered, or better grumbled, across Kenya. As they discuss different festival, digital, and theatrical options, Soko added: ���We genuinely want Kenyans to reckon with this film ��� in the right way ��� together ��� so that we can have that conversation.��� Following in the tradition of Third Cinema, the film act must include the audience, film as an unfinished dialogue and another weapon in the struggle.

As for Boniface, in the midst of a pandemic, he is still out in the streets, alone and armed only with his camera, documenting police violence, revealing what appear to be the deplorable conditions of Kenyans placed in quarantine, and calling out the corrupt politicians who continue to rule.

Softie, the first African film to capture the coveted position of opening film at the 2020 edition of the prestigious Hot Docs festival, was screened as part of its online (due to the COVID-19 pandemic) film festival. The film will also be broadcasted on PBS���s POV and BBC���s Storyville.

The wife���s tale

Image credit Rod Waddington via Flickr CC.

The Wife���s Tale is based on Aida Edemariam���s 60-hour long conversation with her grandmother, Yetemegnu Mekonnen (Nannye), that spans 20 years. By situating her grandmother as a central agent, Aida Edemariam tells a story that transcends the authority of the official archive, and its assumption to singular and credible knowledge.

In this remarkable book that also strikingly nudged my own memory, Edemariam tells us about Yetemegnu���s ordinary life, which in turn evokes the extraordinary lives of Ethiopian women who lived at a certain moment of history; our mothers and grandmothers whose stories are forgotten in contemporary memory. I vividly saw my own mother���s story through Yetemegnu���s tumultuous but amazing life. The narrative covers almost a century, since Yetemegnu lives to be 98.

Each chapter of the book is titled after a month of the Ethiopian calendar. Pagume, the 13th month, ushers in Yetemegnu���s intimate and exhilarating story. The rain on Ruphael���s Day, and its ���thud, thud, thud��� on the corrugated iron roof reminded me of my own childhood when my mother, just like Nannye, dropped frankincense on ���coals huddled into a low clay pot���releasing sweet smoke that rose and tangled with the smell of roasting coffee.���

Attempting to bring the fragments of Yetemegnu���s rich and vast account into one narrative may have been difficult, and results in an occasional disjointed narrative that is sometimes hard to follow. But the narrator���s profound knowledge of Ethiopian history enjoyably invites us in regardless.

Certainly, what amazed me most is Edemariam���s honed and nuanced understanding of her grandmother���s story through her own critical and profound awareness of the tumultuous 20th century history of Ethiopia. She takes us from the Italian occupation, to the 1960 coup d�����tat against Emperor Haile Selassie, to the revolution of 1974 and back again to the ingenuities of the Orthodox church, and to a sensibility of Ethiopian aesthetic. Along this magnificent and winding journey are many lives and relationships; Yetemegnu���s mother, husband, aunts and uncles, reveal their aspirations and desires. The church of Ba���aata Mariam, which once turned Emperor Tewodros II���s mother away when she brought her son to be baptized because she sold kosso (purgative) to survive, and could not ���afford the two jars of dark beer, two bowls of stew and forty injera they demanded in payment,��� became Edemariam���s major source of inquiry.

Yetemegnu was born in 1916 and married Tsega in 1924 in Ba���aata when she was eight years old. Tsega was born in Gojjam where he had gone to church school and where he had learnt the poetry of Ge���ez. It was Memhir Hiruy ���famed throughout the country for his skill with qin��,��� who first saw Tsega���s exceptional knowledge. He took him to Ba���aata Gondar to continue his studies where he was awarded aleqa-ship in 1926. And so Tsega���s turbulent and at once blissful relationship with Ba���aata begins, which the author dazzlingly portrays. For those of us who were brought up by fathers who were intimately connected to the Orthodox church, Tsega���s story melts with our own experiences and Edemariam helps us claim the story with pride. Being a native of Gojjam ���where everyone knew the evil eye flourished,��� complicated Tsega���s relationship to the people of Gondar and significantly so after he became Aleqa. It is through this brief account of Aleqa Tsega���s life that the subject of the book, Yetemegnu, evolves.

Married as a child, she did not know what the world of marriage meant or comprised. It was in her new husband���s house that she cried and played like a child. As for Tsega, ���he worried whether she ate enough. ���Lij��,��� he���d say. ���My child. My child is hungry.��� Again, it was as if Edemariam was telling me the story of my own mother, who was also a child when she was first brought to my father���s house as his wife. So intimate is Yetemegnu���s narrative to my mother���s life, and to the lives of women who once lived through a particular moment of Ethiopian history, that we the descendants can truly imagine their deferred dreams and their anticipation for possibilities in the rapidly unfolding social and cultural transformations of the 20th century.

���Not infrequently,��� Aida narrates, ���he (Tsega) would arrive home to find her in a corner, weeping. Child, he would say gently, why are you crying���Ayzosh, ayzosh, he would murmur, drawing her to him. He would wipe away her tears and gently soften her taut and salty face. Ayzosh. I will be like a mother to you.��� And at other times, a different Tsega would emerge: ���Come here. Her stomach seemed suddenly to have slid to somewhere around her feet. Come here, I said. He raised a stick, and he did not stint.���

Yetemegnu was only 14 when she had her first child, who later dies. Mariam, Mariam, Mariam, direshilin is a chant by midwives and others that Edemariam repeatedly inscribes to describe the performative setting of Yetemegnu���s 10 entries into motherhood. And through the recurring lines of Mariam, Mariam, the author brilliantly conjures this exhilarating chant that was performed by women during a time when there were no hospitals around. Certainly, what fascinated me most was Edemariam���s returning urge to articulate such types of cultural and social formations that are spread throughout the book. It is as if Edemariam wanted to understand her own unfamiliar journey to such experiences and that she also wanted to urgently remind the reader about notions of culture that were once important but are now completely erased from the memory of contemporary knowledge.

And then there is the absorbing story of the Italian occupation when Yetemegnu takes us to the war and to the prominent personalities of the time such as Ras Kassa, to his son and to his brothers who were executed by Italian fascists, and to Abune Tewoflos who later became the second Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and who was Yetemegnu���s family friend. Tewoflos was executed by the military regime in 1974 with 60 other officials of the imperial government. He helped one of Yetemegnu���s sons, Edemariam, (who is the author���s father), to get a scholarship to Canada to study medicine. And after coming back, the son Edemariam would establish the first medical college in the country. Indeed, there were many other stories that revolved around the Italian occupation; the brothels that were frequented by Italians, Tsega���s administrative duties for 44 churches in Gondar, as well as the prayers of mercy by the deacons and priests of Gonderoch Maryam and Ba���aata. While it was Yetemegnu who told the stories to his daughter Aida, in the book it is as though their two voices have merged.

Another exceptional moment is Yetemegnu���s ���wayward��� experience with the zar, a ritual that can only be captured by one���s own lived experience. But with a vividly cinematic narrative, the author takes us through Yetemegnu���s recurring trance as if she felt and sensed the zar through her own imagination of Ethiopian myths and ancestral spirits. In other words, Edemariam locates the past in such a way that seems to converge with her own memory and identity.

We find in many parts of the book that the recording of Yetemegnu���s experience was not adequate by itself. It is only with the fusion of a deeply researched history and imagination that we get a fuller portrayal of Yetemegnu���s life.

June 22, 2020

Betrayal and community

Crossroads Squatters Camp near Cape Town. Image via UN Photo Flickr CC.

Rosy images of South Africa as a harmonious rainbow nation, and a guiding light for the world, are long gone. Instead, slow economic growth, high unemployment, extreme inequality, rolling blackouts, xenophobic attacks, and gender-based violence plague the society and economy.

The African National Congress (ANC), which came to power in 1994 with Nelson Mandela at the helm, continues to dominate opposition parties despite gradual but consistent decline at the polls. After a decade of corruption under the leadership of Jacob Zuma, the ANC���s new leader��� unionist-turned-Rand billionaire businessman, Cyril Ramaphosa���promised to usher in a ���new dawn.��� Yet factional battles continue to infect the ruling party, which appears to have few solutions to the country���s major challenges.

Against this backdrop (prior to the coronavirus pandemic), there is an ongoing wave of local protests in impoverished black neighborhoods around issues such as housing, water and electricity. Kate Alexander identified the protest wave as a ���rebellion of the poor.��� Residents and media outlets call them ���service delivery protests.��� Regardless of the label, they now define post-apartheid South Africa.

To understand the politics of this upsurge, I spent more than a decade conducting interviews and observations in the places where protests were prevalent. Two themes���betrayal and community ���offered a special promise of social movement and transformation, though they also came with crucial pitfalls.

Betrayal

During the democratic transition, and into the present, the ANC promised to provide a ���better life for all.��� Indeed, the ruling party���s legitimacy rests heavily on the appearance that it is reversing the legacy of apartheid and uplifting the black majority.

As Gillian Hart notes in Rethinking the South African Crisis (University of Georgia Press, 2014), the ANC���s claims of leadership over an ongoing process of national liberation leave the party ���vulnerable to counter-claims of betrayal.��� Feelings of betrayal loomed large in the impoverished townships and informal settlements where protests occur.

One example is the Motsoaledi informal settlement in Soweto, where residents protested many times for housing and electricity. In one public statement, activists explained that, ���the black and ANC government gave [us] an impression ���it will improve the lives of the black and poor majority��� ��� The first democratic government in 1994 promised to bring development ���still nothing has happened ��� This [is] making the lives of people at Elias Motsoaledi Squatter Camp to [feel] ���meaningless��� ��� (original emphasis).

Echoing this sentiment, activists from the Thembelihle informal settlement in Lenasia pointed to the urgency that underpinned a 2015 protest: ���the ANC makes promises, but fails to deliver. When they do not cooperate, residents are left with no other alternative but to engage in mass direct action ��� after 20 years we still live in shacks, we need houses now.���

These ���counter-claims of betrayal��� reflect the critical energy that lies beneath South Africa���s widespread protests. They indicate that residents are not prepared to accept the status quo. The notion of betrayal also provides a moral foundation for resistance, keeping alive promises of equality and prosperity that have yet to arrive.

Community

Building on the history of urban resistance and ���people���s power��� under apartheid, notions of place-based community added to the emotional fuel and facilitated collective organization. The idea of community signaled a closeness to the poor and working class, rather than elites. Notions of community also enabled activists to build solidarity across the many divisions that permeated impoverished urban areas, from employment and immigration status to political party affiliation.

Party politics were especially important. The ANC���s weakening grip, and in turn the growth of opposition parties combined to amplify political divisions. Community enabled activists to build solidarity across this division. As one activist from Tsakane explained, ���We all come from different political parties, but when we march, we march with one voice���community.���

Appeals to community represent a possible point of departure for radical projects. Alluding to solidarity between those who live side-by-side, notions of place-based community seek harmony across various forms of difference, and thus present an avenue for rebuilding the quickly fading rainbow nation. Of course, healthy communities require resources to thrive, and so a politics of community implies a politics of redistribution as well.

As a unit for collective deliberation, community may also serve as a foundation for radical participatory democracy. It is not surprising that activists in protest-affected areas such as Bekkersdal and Thembelihle referred to their organizing spaces as the ���people���s parliament.���

Avoiding pitfalls

Commentators often glorify South Africa���s urban poor as harbingers of progressive transformation. Like any concept or slogan, however, ideas of betrayal and community are malleable. They may align with various political projects.

The evidence from local protests underscores a few potential pitfalls. One pitfall is that betrayal may lead to an emphasis on administrative fixes rather than political ones. In this case, residents look to political leaders and state officials to correct their behavior through narrow actions, rather than demanding and pushing for broader transformation. The idea of ���service delivery,��� which implies that the government must deliver what it has promised, hints at this possibility.

Another pitfall is isolation. This is what has happened in South Africa, as protests by specific communities remain highly localized, with little solidarity across residential areas. Localization can devolve into competition over access to scarce resources, rather than push for redistribution. Protesters frequently demonstrated this danger when they justified protests by lamenting the resources of nearby areas, despite having similar social and economic profiles.

The task, then, is to use the ideas of betrayal and community to move beyond these pitfalls. It is to harness the frustration and anger that underpin feelings of betrayal, and to leverage the powerful idea of community to build solidarity and advance radical projects. This vision is certainly a bit fuzzy, but promising alternatives for South Africa are currently difficult to find.

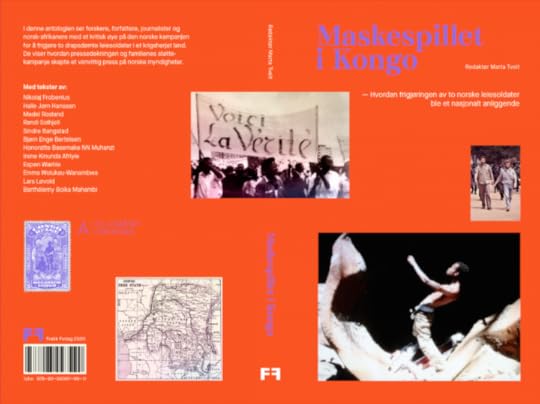

A Murder in Congo

Image credit NTB.

The so-called ���Congo case��� was one of the largest media spectacles of the decade in Norway. It has resulted in about a dozen books, several TV-documentaries, a podcast-series and a full-length feature film with some of Norway���s most famous actors in the leading roles.

A quick recap for those outside of Norway: The case concerns the alleged crimes of two Norwegian nationals, Joshua French (dual British passport) and Tjostolv Moland. In 2009, the two were operating from Uganda as for-hire mercenaries, under the thin guise of a security firm called SIG. As emerged later, the two were ex-Norwegian military, and they worked for a time as security on ships off the coast of Somalia. They ran unprofessional and inhumane training camps for local would-be soldiers in Uganda���as video evidence suggests. But business was not booming, so Moland contacted Laurent Nkunda, then leader of the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD). In 2009 Nkunda���s forces had stormed Kisangani, murdering and raping thousands of women and children. Moland wrote:

We (SIG) wish to offer you our services and our support, mister general. […] I have formed a picture of you as a highly intelligent and well-educated person. Therefore, I know that you will appreciate europeans supporting you in your intelligence-work, because europeans are unlikely to cause suspicion ���

In May 2009, French and Moland went from Uganda into eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) on an unknown mission. On May 5, through a disputed series of events, they allegedly shot and killed their 47-year-old driver Abedi Kasongo, near Bafwasende, Orientale Province. French was arrested on May 9 in the Epulu game reserve, around 200 kilometers from Kisangani. Moland was arrested two days later in Ituri Province, a few hundred kilometers farther northeast.

The two accused asserted their innocence throughout several highly publicized court cases in the DRC. They alleged that the party had been ambushed by government forces, and Kasongo died as a result. In Norway a powerful campaign was launched by Joshua French���s mother, calling for the release of the prisoners. It gained massive support among Christian communities and put enormous pressure on the Norwegian foreign ministry for the return of French and Moland. At one point the foreign ministry even collaborated with the controversial Israeli diamond-billionaire Dan Gertler, who at the time carried considerable influence in DRC.

Moland and French did relatively well in prison at first. They hung up a sign outside their prison-cell that read ���Leopoldville��� (A Norwegian podcast series goes deeper into how the two shared a romantic nostalgia for the bygone era of white colonial Africa). They were fit, had access to servants, and to better food and alcohol from supporters outside prison.

As the years went by, the campaign kept up the pressure, but the situation for the two prisoners deteriorated. Moland wrote a letter confessing to the murder of Abedi Kasongo, which he read aloud in court. However, he was also severely ill with malaria at the time, so French and others dismissed the letter as the ravings of delirium. Moland died in prison in 2013. Norwegian coroners concluded the cause to be suicide. Joshua French served in Congolese prisons for almost eight years, surviving poor sanitary conditions and several rounds of severe illness, until his release and return to Norway in May 2017.

Image credit Marta Tveit.

Image credit Marta Tveit.In the end, as detailed in the Norwegian anthology, Maskepillet i Kongo (Foul Play in Congo), the international struggle for the release of French included ���three Norwegian prime-ministers and four foreign ministers, one former president of the USA, the British prime minister and foreign minister, two Nobel-prize winners, several bishops, a host of Norwegian parliamentarians, and eighteen members of the European parliament,��� among a host of others. There is no official record of how much tax money and other public resources were devoted to securing French���s release, but it has been estimated to be at least 4,7 million kroner ($500,000). Since his return to Norway, French has been touring the country to sold-out crowds, giving lectures about his ���African adventures.���

The case left a bad taste in the mouths of many people. There are questions that we may never get the answers to. Why is Joshua French walking free, when there is mounting evidence that both he and Moland conducted paramilitary ���missions��� that may have contravened not only Norwegian law, but the laws of various African states, as well as international conventions and laws? Why was there such reluctance on the part of the Norwegian public to believe that the two were guilty of anything but an innocent ���boys��� trip��� that veered a little off-track in Africa? Why did we expect an independent nation in which the two had committed a crime to disregard its own judicial system and return the prisoners to Europe? Why does the same concern not apply to foreign nationals imprisoned in Norway? Why are French���s public speaking appearances so popular? Why the focus on the criminals and so little on the victim, who left behind his devastated wife, Bibiche Olendjeke, small children and extended family? What is so special about French and Moland?

Foul Play in Congo attempts to expand the debate to more than two men���s pursuits and motives. The aim of the anthology is to bring forth the largely overlooked Norwegian-Congolese and Norwegian-African perspectives. Furthermore, it attempts to give space to critical voices, of which there are many. Each of the contributors approaches the case from their unique points of view. Espen W��hle, the maritime historian, tells the story of the first Norwegian mercenaries in the Congo, employed in Belgian King Leopold���s army in the 1800s. Halle J��rn Hanssen, the main contributor and the driving force behind the project, offers up his years of investigative reporting about the case. Artist and research scholar, Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, examines the story behind the infamous so-called ���blood-picture,��� the shocking image of Moland wiping blood out of the ambushed Landover with a big smile on his face. (The same image now hangs in the Norwegian colonial exhibition at the Bergen University Museum). Irene Kinunda Afriyie, a Norwegian-Congolese teacher and journalist writes personal reflections, highlighting how Congolese immigrants to Norway have been affected by the case. Lars L��vold and Barth��lemy Boika Mahambi, who both worked with the Rainforest Foundation in Congo at the time French and Moland were active, describe how a vulnerable and incredibly important bilateral rainforest preservation project, worth billions of kroner, fell through due to the French-Moland case. We get an afterword by the celebrated Norwegian anthropologist, Thomas Hylland Eriksen, who writes about tenacious prejudices, historical repetitions, ignorance and, most of all, disappointment.

Joshua French has been mentioned nearly 40,000 times in Norwegian media since the case was first brought to the attention of the public in 2009. The media slant in this case was clear���the Congolese court authorities were ridiculed, Conradian exotification and reductionist analysis abounded, and the whole of DRC was arguably portrayed as a banana republic.

In the prologue of Foul Play in Congo I write: ���This is not a book about Tjostolv Moland and Joshua French. This is a book about Norway and Norwegians.��� Indeed, it is about Norwegian colonial imaginings of Congo, and of Africa. Though Norway���s active role in colonization and the triangle-trade was limited, the European colonial paradigm���especially expressed in the imagining of people with darker skin, reached its long tentacles up north. The residue is tangible in the form of mindsets based on the construction of race, inherited and planted in me, in us, here and now. The case shook our nation. It held up a mirror to one of the world���s most progressive countries, showing us some ugly truths. There is something that does not quite add up in how we like to represent and think about ourselves, and what this case brings out in us. Although we are far north, Norway as part of Europe has been a signatory to the mindset that made colonization, slavery and generally 500 years of European global domination possible. (Both Moland and French declared a deep respect for Margaret Thatcher, and disdain for ���the feminist state Norway,��� which to them was ���anti-white��� and ���anti-men��� (see Kongonotatene).

We are beginning to see it now, thanks to the unceasing efforts of local and global activists. Wrestling with the Congo case is part of the protracted process of understanding, and rejecting the race-contract. It materializes in a series of small and big moments that are about answering the question: How should we as Norwegians respond to increased globalization and contact with less-understood others?

The discourse has reached the point where one begins to look at the inner coloniality that inhabits the many, not just the few. Yet, 15,000 young people screaming ���Black Lives Matter��� in front of the Norwegian parliament recently, washes away some of the disappointment I too have been feeling working on the Congo case, replacing it with hope for the future.

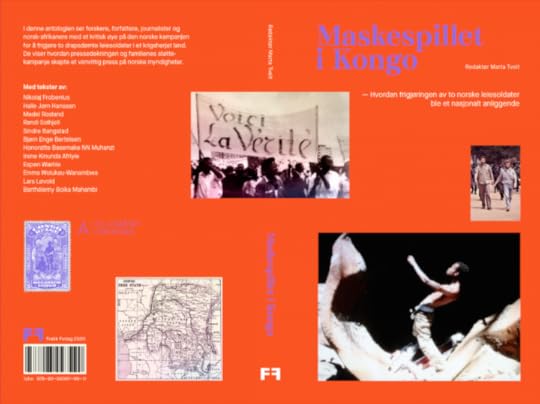

The murder in Congo, a Norwegian drama

Image credit NTB.

The so-called ���Congo case��� was one of the largest media spectacles of the decade in Norway. It has resulted in about a dozen books, several TV-documentaries, a podcast-series and a full-length feature film with some of Norway���s most famous actors in the leading roles.

A quick recap for those outside of Norway: The case concerns the alleged crimes of two Norwegian nationals, Joshua French (dual British passport) and Tjostolv Moland. In 2009, the two were operating from Uganda as for-hire mercenaries, under the thin guise of a security firm called SIG. As emerged later, the two were ex-Norwegian military, and they worked for a time as security on ships off the coast of Somalia. They ran unprofessional and inhumane training camps for local would-be soldiers in Uganda���as video evidence suggests. But business was not booming, so Moland contacted Laurent Nkunda, then leader of the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD). In 2009 Nkunda���s forces had stormed Kisangani, murdering and raping thousands of women and children. Moland wrote:

We (SIG) wish to offer you our services and our support, mister general. […] I have formed a picture of you as a highly intelligent and well-educated person. Therefore, I know that you will appreciate europeans supporting you in your intelligence-work, because europeans are unlikely to cause suspicion ���

In May 2009, French and Moland went from Uganda into eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) on an unknown mission. On May 5, through a disputed series of events, they allegedly shot and killed their 47-year-old driver Abedi Kasongo, near Bafwasende, Orientale Province. French was arrested on May 9 in the Epulu game reserve, around 200 kilometers from Kisangani. Moland was arrested two days later in Ituri Province, a few hundred kilometers farther northeast.

The two accused asserted their innocence throughout several highly publicized court cases in the DRC. They alleged that the party had been ambushed by government forces, and Kasongo died as a result. In Norway a powerful campaign was launched by Joshua French���s mother, calling for the release of the prisoners. It gained massive support among Christian communities and put enormous pressure on the Norwegian foreign ministry for the return of French and Moland. At one point the foreign ministry even collaborated with the controversial Israeli diamond-billionaire Dan Gertler, who at the time carried considerable influence in DRC.

Moland and French did relatively well in prison at first. They hung up a sign outside their prison-cell that read ���Leopoldville��� (A Norwegian podcast series goes deeper into how the two shared a romantic nostalgia for the bygone era of white colonial Africa). They were fit, had access to servants, and to better food and alcohol from supporters outside prison.

As the years went by, the campaign kept up the pressure, but the situation for the two prisoners deteriorated. Moland wrote a letter confessing to the murder of Abedi Kasongo, which he read aloud in court. However, he was also severely ill with malaria at the time, so French and others dismissed the letter as the ravings of delirium. Moland died in prison in 2013. Norwegian coroners concluded the cause to be suicide. Joshua French served in Congolese prisons for almost eight years, surviving poor sanitary conditions and several rounds of severe illness, until his release and return to Norway in May 2017.

Image credit Marta Tveit.

Image credit Marta Tveit.In the end, as detailed in the Norwegian anthology, Maskepillet i Kongo (Foul Play in Congo), the international struggle for the release of French included ���three Norwegian prime-ministers and four foreign ministers, one former president of the USA, the British prime minister and foreign minister, two Nobel-prize winners, several bishops, a host of Norwegian parliamentarians, and eighteen members of the European parliament,��� among a host of others. There is no official record of how much tax money and other public resources were devoted to securing French���s release, but it has been estimated to be at least 4,7 million kroner ($500,000). Since his return to Norway, French has been touring the country to sold-out crowds, giving lectures about his ���African adventures.���

The case left a bad taste in the mouths of many people. There are questions that we may never get the answers to. Why is Joshua French walking free, when there is mounting evidence that both he and Moland conducted paramilitary ���missions��� that may have contravened not only Norwegian law, but the laws of various African states, as well as international conventions and laws? Why was there such reluctance on the part of the Norwegian public to believe that the two were guilty of anything but an innocent ���boys��� trip��� that veered a little off-track in Africa? Why did we expect an independent nation in which the two had committed a crime to disregard its own judicial system and return the prisoners to Europe? Why does the same concern not apply to foreign nationals imprisoned in Norway? Why are French���s public speaking appearances so popular? Why the focus on the criminals and so little on the victim, who left behind his devastated wife, Bibiche Olendjeke, small children and extended family? What is so special about French and Moland?

Foul Play in Congo attempts to expand the debate to more than two men���s pursuits and motives. The aim of the anthology is to bring forth the largely overlooked Norwegian-Congolese and Norwegian-African perspectives. Furthermore, it attempts to give space to critical voices, of which there are many. Each of the contributors approaches the case from their unique points of view. Espen W��hle, the maritime historian, tells the story of the first Norwegian mercenaries in the Congo, employed in Belgian King Leopold���s army in the 1800s. Halle J��rn Hanssen, the main contributor and the driving force behind the project, offers up his years of investigative reporting about the case. Artist and research scholar, Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, examines the story behind the infamous so-called ���blood-picture,��� the shocking image of Moland wiping blood out of the ambushed Landover with a big smile on his face. (The same image now hangs in the Norwegian colonial exhibition at the Bergen University Museum). Irene Kinunda Afriyie, a Norwegian-Congolese teacher and journalist writes personal reflections, highlighting how Congolese immigrants to Norway have been affected by the case. Lars L��vold and Barth��lemy Boika Mahambi, who both worked with the Rainforest Foundation in Congo at the time French and Moland were active, describe how a vulnerable and incredibly important bilateral rainforest preservation project, worth billions of kroner, fell through due to the French-Moland case. We get an afterword by the celebrated Norwegian anthropologist, Thomas Hylland Eriksen, who writes about tenacious prejudices, historical repetitions, ignorance and, most of all, disappointment.

Joshua French has been mentioned nearly 40,000 times in Norwegian media since the case was first brought to the attention of the public in 2009. The media slant in this case was clear���the Congolese court authorities were ridiculed, Conradian exotification and reductionist analysis abounded, and the whole of DRC was arguably portrayed as a banana republic.

In the prologue of Foul Play in Congo I write: ���This is not a book about Tjostolv Moland and Joshua French. This is a book about Norway and Norwegians.��� Indeed, it is about Norwegian colonial imaginings of Congo, and of Africa. Though Norway���s active role in colonization and the triangle-trade was limited, the European colonial paradigm���especially expressed in the imagining of people with darker skin, reached its long tentacles up north. The residue is tangible in the form of mindsets based on the construction of race, inherited and planted in me, in us, here and now. The case shook our nation. It held up a mirror to one of the world���s most progressive countries, showing us some ugly truths. There is something that does not quite add up in how we like to represent and think about ourselves, and what this case brings out in us. Although we are far north, Norway as part of Europe has been a signatory to the mindset that made colonization, slavery and generally 500 years of European global domination possible. (Both Moland and French declared a deep respect for Margaret Thatcher, and disdain for ���the feminist state Norway,��� which to them was ���anti-white��� and ���anti-men��� (see Kongonotatene).

We are beginning to see it now, thanks to the unceasing efforts of local and global activists. Wrestling with the Congo case is part of the protracted process of understanding, and rejecting the race-contract. It materializes in a series of small and big moments that are about answering the question: How should we as Norwegians respond to increased globalization and contact with less-understood others?

The discourse has reached the point where one begins to look at the inner coloniality that inhabits the many, not just the few. Yet, 15,000 young people screaming ���Black Lives Matter��� in front of the Norwegian parliament recently, washes away some of the disappointment I too have been feeling working on the Congo case, replacing it with hope for the future.

June 21, 2020

Artists help us leap into the unknown

The Mobile Museum by Latifah Iddriss outside ANO Institute, Accra, Ghana. Image credit Kim Gurney.

Media coverage of the coronavirus pandemic has focused on the unprecedented nature of the current challenges. Yet lockdowns, socioeconomic precarity, and prevailing uncertainty are not new to many in this generation nor its predecessors. Artists often innovate collectivities, drawn from everyday practices, to surmount such difficulties. It is perhaps no surprise we are seeing the return���in economic shifts, political stance and mutual aid���even as the novel coronavirus keeps us socially distant. Artistic thinking has a lot to offer.

Sitting in my backyard, in self-isolation, with disinfectant swimming in the sink, I picked up a glass sphere that previously formed part of an art installation. Inscribed with a one-liner from my grandmother���s journal, it collapsed past and present: ���In Jeppe [Johannesburg] at the time of the great influenza epidemic people were dying like flies. Mom told that little handcarts went up and down the streets gathering corpses���some houses they found people who had been gone a day or two ��� She told us she had soaked sheets in Lysol and hung them at the doors to prevent infection.���

Shortly afterwards, during national lockdown, I finally completed Saidiya Hartman���s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, sourced from archival fragments of overlooked young black womens��� lives in early 20th century America. Hartman narrates how the generation born after emancipation wanted real freedom. However: ���The state of emergency was the norm not the exception.��� It was the threshold of a new era of attempted social reforms yet defined by extremes from imperial wars to epidemics, racial segregation and riots, threatening new forms of servitude. To live free and otherwise required a leap into the unknown, ���creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical art of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, a transfiguration of the given.���

As Hartman relates, leaping into the unknown is familiar territory for these young black women for reasons that are often structural. I���ve seen a similar relationship between artists and uncertainty in my research. Artistic thinking is a combination of refusals and re-imaginations in response that manifest in strategies of collectivity. It���s resilience through nested capacity.

Take the example of Gordon Froud, an artist whose Cone Virus work I followed back in 2015 when the Johannesburg inner city building he worked in was put up for sale. As a partial solution, when he relocated, Froud started a Stokvel Gallery (a stokvel is like a credit union or an informal savings scheme). It uses the merry-go-round principle where member artists contribute fees on a shared basis and the benefits rotate. Notably, Froud���s innovation derives from the social fabric, from a solidarity economy logic of the stokvel in South Africa and its equivalent in other cities of the South, as a way to pool resources for common good. This logic is also reflected in forthcoming curatorial strategies by artistic collectives such as ruangrupa, from Indonesia, which in 2022 centers documenta 15 around a resource governance model called lumbung or rice barn. It refers to a collective pot or accumulation system where crops are stored as a future shared common resource. The exhibition looks at the city and its systems including alternative education, regenerative economy models and art in social practice.

Such patterns repeat in independent art spaces in five fast-urbanizing African cities where I recently conducted research in a project called Platform/Plotform. They, too, for different reasons were operating in contexts of flux. The working principles of these independent art spaces also redeploy everyday solutions commonplace in urban social life (principles like horizontality, second chance and elasticity). And, like ruangrupa, they believe in institution building as an artistic form.

For instance, standing outside the ANO Institute of Art and Knowledge in Accra, Ghana is a mobile museum. It looks just like a regular ubiquitous trading kiosk, which might house a hairdressing salon or a hardware store. But its walls have wire strands instead of sheeting and it���s collapsible so it can pick up and go. This mobile museum, designed by architect Latifah Iddriss, represents an ongoing project developed by ANO founder Nana Oforiatta Ayim on the concept of a future museum, challenging the white-cube art space model to create more fluid structures that better reflect the imbrication of art and daily life. The project includes travelling around the 10 regions of Ghana, asking people���fishermen, kente sellers, priests, traditional healers, poets, traders and more���what art and culture means to them, and how they would like to see it represented.

Existing innovations using everyday urban logics are easy to overlook. But as Clapperton Muvhanga writes about science and technology in Africa, it���s the ordinary innovations borne out of quotidian realities that are notable, and these are heightened during moments of stress or crisis. Such hacks are what Kenyans might call a panya route���a back route to an official route, a self-invented commons. Artists are particularly adept at such re-routing and path making. As we seek new forms and strategies to remake the social contract, public institutions, and a more equitable global commons following force majeure, when the usual rules no longer hold, we might find inspiration in the collectivities and working principles of artists. We might think of such practices, following Simon Njami, when he curated the 2018 OffBiennale in Cairo, Something Else and described independent art spaces as offering a parenthesis and some ���breathing space.��� At a time of a viral pandemic attacking the lungs, nothing could be more vital.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers