Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 166

July 8, 2020

A plagued history of Kampala

colonial regime used a series of plagues to cut Ugandans out of the capital city.

Group photo at the opening of the new Mengo Hospital, Uganda. Image credit the Wellcome Trust UK, CC.

When COVID-19 was first declared a global pandemic in mid-March, the Ugandan government���experienced in controlling Ebola outbreaks in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo���quickly shut the country���s borders, roads, and work, using the state security forces to enforce the closures. In Kampala, on the hilly, northwestern shores of Lake Victoria, videos showing the police beating market vendors and boda boda drivers breaking curfew quickly emerged and spread around the country.

One hundred years ago, the colonial state was conducting a similar violence in the name of different public health threats, and their response continues to define much of the form of Kampala today. To understand the legacy of public health interventions as a state tool, and the violence used to enforce its power, we have to return to the founding of Kampala.

The history of Kampala as twin cities goes back to Kabaka Mwanga II���s rise to the throne of Buganda in 1885, when he established his kibuga (royal court) on Mengo Hill and thousands of his subjects settled around the area. When Fredrick Lugard���later famous for codifying indirect rule in British colonies���reached the area five years later, he decided to build Fort Lugard on a neighboring hill, which to the dismay of the Kabaka was to become known as Kampala.

Extending their settlement to Kololo and Nakasero hills, the white settlers created a competing capital city and used land reforms, poll taxes, and colonial violence to exploit African labor. As their power grew, a tacit agreement was reached between the Kabaka and the British that would see the neighboring settlements of the Kibuga and Kampala remain the homes for the African and foreign populations respectively.

Records are patchy at best, but Europeans��� arrival in the Great Lakes region seem to have been accompanied by a surge in disease. Colonial health archives focus on malaria, sleeping sickness, and the bubonic plague, the last of which reappeared in 1899 in Uganda and was present in all districts within the following decade. It���s estimated that sleeping sickness killed a quarter of a million people in neighboring Busoga from 1900-1920, while plague in Buganda was concentrated in the Kibuga, where nearly 2% of the population died from it in the following decades. To European settlers, having come to an agreement with the Buganda kingdom, but still seeking to expand their powers and protect themselves from the public health crises, an ideal solution existed: segregation as a public health intervention.

In 1915 W. J. Simpson, a visiting academic from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, called for the establishment of segregated residential areas for ���Europeans, Asiatics and Africans ��� and that there should be a neutral belt of open unoccupied country of at least 300 yards in which between the European residences and those of the Asiatic and African.��� Adopting the 1824 Vagrancy Act from the UK allowed the colonial government to de-indigenize Kampala, a common practice across colonial capitals at the time. This law was adapted into the 1950 Penal Code Act as ���idle and disorderly��� laws, which were not seriously challenged until October 2019 when President Yoweri Museveni called for a review of the law. However, state violence is hard to change, and in the current pandemic the police shot several boda boda drivers who were defying the lockdown.

Although not still as segregated by class and race as cities like Nairobi or Johannesburg, real estate inflation and growing income inequality in Kampala nonetheless force many of the city���s poorest to make long treks across town for work, exposing them to the police and other extortionists. And predictably, when the lockdown in Uganda began in late March, Museveni banned popular transport before banning private cars, even though popular transport is responsible for 50% of trips in the city (a further 40% are by foot).

Traders have been sleeping in markets, unable to get home. Police have used the curfew as a blank check to beat street hawkers, market women, and boda boda drivers, heaping additional economic hardship on the urban poor. Even health workers have taken to riding crowded ambulances to get to work in some parts of the country.

While the British no longer directly run Kampala, the green belt segregating the white neighborhoods has become the golf course used by the (still disproportionately foreign) elite living in their former headquarters of Kololo and Nakasero. Meanwhile, the very few people who can work remotely in Uganda are also those with a significantly more stable income than most. Plagues have changed names and elites have swapped out, but the response of the state continues to perpetuate division and political repression.

July 7, 2020

Ubaguzi wa vijana na mapambano ya kijamii

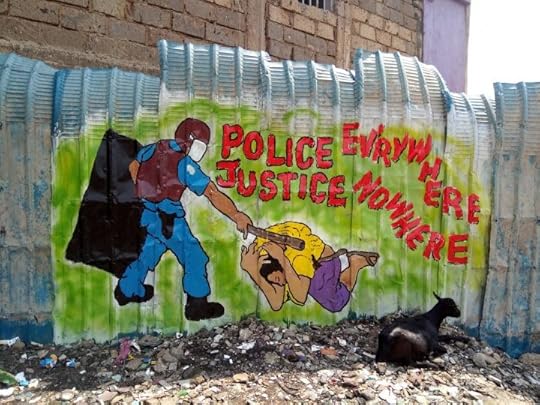

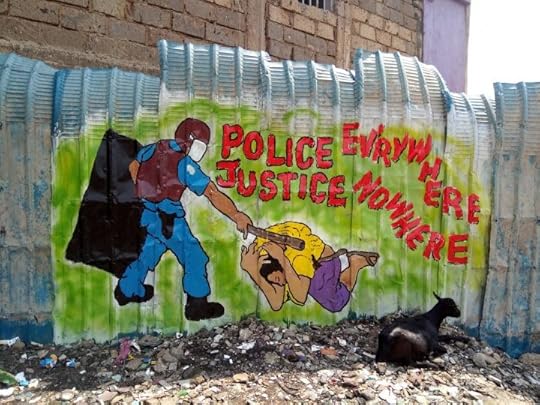

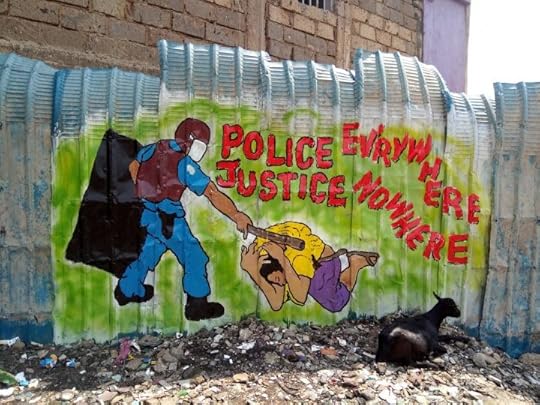

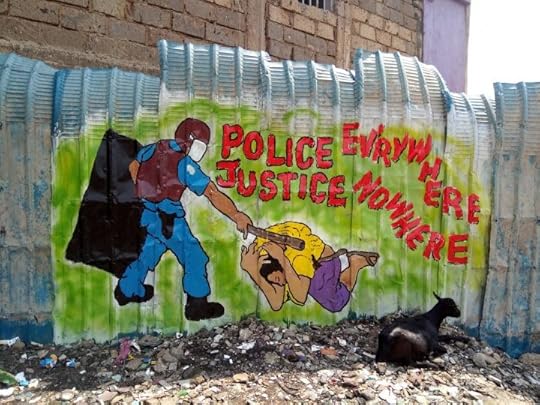

Image credit Mathare Social Justice Centre.

For English click here.

Chapisho hili limetoka kwa Ukiritimba wetu katika safu ya Jiji langu, kushirikiana na Kituo cha Haki ya Jamii cha Mathare jijini Nairobi.

Mimi ni Minoo. Nilizaliwa na kulelewa katika kijiji cha Mukuru. Nimeshuhudia aina zote za ukatili wa polisi na ubaguzi wa vijana, pamoja na hali ya umaskini. Nimekutana na vijana kutoka mitaa ya matajiri na ilikuwa wazi kuwa hawajapambana na hali kama hii ya ubaguzi. Hii ni dhibitisho kuwa umaskini ni uhalifu. Mabepari na serikali wanaohalifisha umaskini ndio wanatusukuma kwenye umaskini ili tunapoomba chakula wanavuna jasho letu na kutulipa pesa kidogo zaidi.

Niliamua kuweka rasta kwenye nywele zangu, ila kama mkaazi wa Mukuru Kwa Njenga, nilikuwa na hofu nyingi sana. Niliona jinsi wenzangu walikamatwa wakiwa na nywele zao za rasta, waliaandikiwa mashtaka ya uwongo ya kupatikana na bangi au matendo mengine ya uhalifu. Hali huo mbovu ya vijana umewafanya watu katika jamii pia kuwaona vijana wenye nywele ndefu za rasta kama wahalifu au wanaotumia dawa za kulevya. Nilishuhudia rafiki yangu Kaparo akinyolewa na kipande cha mabati katika kituo cha polisi. Walidai kuwa alikuwa amepigana na mwana wa jasusi wa polisi. Binamu yangu pia na rafiki zake saba walikamatwa kwa madai ya kuwa na bhangi. Yeye na wenzake wane walinyolewa na mapolisi wakitumia wembe moja kati yao. Waliandikiwa mashataka ya uongo kuwa walikuwa wakipanga kuiba. Ilibidii wazazi wao kutoa hongo ili waachiliwe. Mwaka wa 2019, vijana nane wa kiume walipigwa risasi na polisi walipokuwa na mkutano wa kujadiliana kuhusu ukusanyaji wa takataka. Walikuwa na umri kati ya miaka 16 -24.

Nilisomea shule ya msingi ya Mukuru Kwa Njenga iliyokuwa karibu na nyumbani. Shule hiyo ilikuwa na uwanja mkubwa ambao vijana wengi walitumia kucheza mchezo wa kandanda. Lakini, usiku uwanja huo ulikuwa kichinjio. Kijana mmoja aliyekuwa muuzaji wa kitambo wa bangi alipigwa risasi muda wa saa mbili usiku. Polisi walidai kuwa alikuwa mhalifu na kumwekea kadi nyingi za simu na risasi bandia (bonoko).

Kila usiku, hata wakati mwingine mchana, mimi huskia milio ya risasi kutoka kwenye uwanja. Sikupitia ukatili mwingi sana kama mwanamke lakini nimewaona vijana wenzangu wa kiume wakiteseka kila siku. Wakati mwingine, baba yangu husema anamshukuru Mungu kwa kutopata mtoto wa kiume, kisa na maana hajui jinsi angeweza kumlinda dhidi ya ukatili huu unaofanyika katika mitaa ya walalahoi.

Ni hatari kuwa na mavazi za bei ghali kwani inahatarisha maisha yako. Unaweza kushtakiwa kwa wizi na kupigwa kikatili. Najua rafiki zangu ambao hawawezi kuvaa vizuri kwa sababu wamewahi kuwa jela kwa miaka mingi. Hata baada ya kubadili mienendo yao, maafisa wa polisi bado wana mazoea ya kuwanyanyasa, kuwapiga kikatili wakidai kuwa wanataka kujua walikoiba nguo hizo.

Nimenusurika katika huu mtaa nikiona jinsi serikali inavyopata pesa kwa kukandamiza maisha yetu. Serikali inaeneza woga kwa kutumia vurugu na jela. Tunahisi hali ya athari mahali ambapo tunapaita nyumbani. Nina marafiki wasio na hatia wanaozorota gerezani. Kosa lao ni kuwa maskini na kuishi katika mtaa duni. Hatukuchagua hali hii ya maisha.

Mimi ni Maryanne Kasina. Nilizaliwa na kukuzwa Kayole. Nimekua katika jamii iliyojaa udhalimu na najua umaskini ni vurugu. Nilipokuwa shule ya msingi sikuelewa mbona Kayole kulijaa vurugu. Ndoa ya wazazi wangu iliharibika nilipokuwa shule ya upili. Hapo ikawa vigumu sana kutulea. Mamangu alikuwa na watoto kumi. Ilibidi tutoke shuke ya uma na kuenda shule ya kibinafsi iliyo ya bei ya chini ambayo mama angeweza kumudu. Shule ya kibinafsi mtaani ni za bei ya chini, kwa sababu hakuna walimu waliohitimu na mitambo kama maktaba na maabara.

Baada ya kumaliza shule ya upili, hali ilizidi kuharibika nyumbani. Nilifahamu kuwa sitapata karo ya kuendeleza masomo yangu. Tulilala njaa mara nyingi, na kama mtoto wa pili katika familia ya watoto kumi, ilibidi nitafute njia ya kupata chakula.

Rafiki yangu alinieleza kuhusu wakala fulani wa kunisafirisha nje ya nchi kufanya kazi. Nilijua hatari zilizoko. Nilikuwa nimeskia na kuona kwenye vyombo vya habari namna wafanyikazi walivyoona mateso na wakati mwingine hata kifo. Nilihofia sana lakini ilibidi niende. Wakala iliniarifu kuwa wamepata kazi ya uhudumu Dubai tarehe 13 Disemba, mwaka 2013. Mkataba ulikuwa wa miaka miwili. Visa na tikiti ya ndege pia nilipewa. Niliwauliza kama ni kweli nitafanya kazi kwenye hoteli kwa sababu nilihofia zaidi kufanya kazi ya nyumbani kwani wanapitia ukiukaji mwingi wa haki zao. Kilichonishangaza ni kuwa mkataba huu ulikuwa umeandikwa kwa lugha ya kiArabu, na hata hivyo ilibidi ni tie saini. Tarehe 15 Disemba, mwaka huo, nilisafiri kuenda Dubai. Nilipofika na kuelezwa kinachohitajika kwangu kama mfanyi kazi, mwili wangu uliganda na nikatamani kupata mabawa kurudi nchini kwangu. Nilitamani ardhi ipasuke nimezwe lakini wapi. Hali ya kufanya kazi ilkuwa mbovu zaidi.

Niliporudi sikujua kwa kuanzia, kwa maana kila kijana alitumani kuwa ningekuja kuwaoka katika hali zao duni. Walidhani nitawasaidia kupata kazi ngambo bila kujua jinsi hali ilivyo kama jehenamu.Tulikosa njia mbadala na kufadhaika kujimudu, tuliamua kutafuta njia nyingine ya kujimudu kupitia vikundi vya vijana.

Kikundi cha Gaza kilikuwa cha densi tulipokuwa shule ya upili.Tulishindana na mitaa jirani kwa michuano wa kirafiki. Baada ya kumaliza shule ya upili tulitawanyika wengine wakajiunga na vikundi vingine. Vikundi hivi vilifanya miradi ya kukuza jamii na kulinda mazingira. Harakati hizi zilitishia watu fulani, hivyo wakanza kuhusisha majasusi.

Walifanya hivi kwa kuwapea vijana silaha wapiganie ardhi ya matajiri. Vijana walidhani masiha yatabadilika kwani wangepata kipande cha ardhi ya kufanya ukulima na manyumba. Dhana hii iliwafanya kupiga vita hivi na wakashinda, lakini vita hivi vilikuwa vimechochezwa na mfumo. Baadaye, wakaanza kumalizwa, mmoja baada ya mwingine. Ardhi hiyo ilikuja kuuzwa kwa mamilionea wengine.

Nimepoteza rafiki zangu kwa mauaji ya polisi. Wengi niliokuwa nao wamezikwa. Tuliogopa sana kuonekana pamoja kwa hofu ya polisi kutuandama na kutupiga risasi sote, kutukamata ama kutuwekea mashtaka ya uongo ya uhalifu.

Mwaka wa 2017, Rais Uhuru Kenyatta alipeana amri ya kupiga risasi na kuua. Nilishangaa ni nani hawa ambao watauawa? Ni sisi vijana tuliohalifishwa na polisi na ata jamii, pamoja na wanasiasa walio na malengo ya kibinafsi? Sisi ambao tumekuwa mitambo ya kutoa pesa kwa polisi wanotunyang���anya mapato madogo tunayopata? Sisi tulio katika magereza kwa mashtaka ya uongo ya kuwa na bangi na kukosa kutoa hongo?

Idadi ya vituo vya polisi inashinda ya hospitali za uma katika mitaa duni. Serikali inatudhalilisha na kutuua kwa sababu wameshindwa kutupa mahitaji ya kimsingi. Mfumo wa upebari unawanufaisha wachache. Vijana wanapojipanga wanaingiza majasusi katika harakati zao.

Wengine wetu waliokuwa Gaza wanalipa polisi ili waishi. Wengi wetu ni wahasiriwa ama walionusuru haki ya mfumo huu kutojali. Wale ambao hawana uwezo wa kutoa hongo hawana amani. Polisi wauaji wanawaanika mtandaoni na kuwaua.

Nilikutana na Minoo mwaka wa 2018. Nilikuwa namsaidia kuanzisha kituo cha haki ya kijamii ya Mukuru.Tulijadiliana na rafiki wengine wa kike na kuanzisha shirika la wanawake walio kwenye vituo vya haki ya kijamii���Women in Social Justice Centres movement. Shirika hili inachukua hatua za kisiasa. Tunaunda nafasi salama ya watu wote waliokandamizwa. Vita dhidi ya ubepari vinaendelea. Tunafaa kuikumbatia itikadi ya kike kama njia ya kuelekea ujamaa, kurudi kwenye mizizi yetu na utu wetu.

Tunapoangazia maisha yetu na matukio yanaotokea duniani tumegundua kuwa hatuhitaji mageuzi katika idara ya polisi tu, lakini mageuzi ya mfumo wote. Bado tuko chini ya ukoloni. Bado hatujapata uhuru.

Waandishi:

Minoo Kyaa ni mwanachama wa kituo cha haki ya kijamii na Mukuru na kinara wa wanotumia muziki aina ya reggae kueneza haki ya kijamii. Ni mwanachama pia wa shirika la wanawake wa vituo vya haki ya kijamii. Ni mwandishi na mshairi. Sanaa yake inahati mapambano na upinzani.

Maryanne Kasian ni mwandishi na mpatanishi wa wanawake walioko kwenye vituo vya haki ya kijamii nchini Kenya. Yeye ni mojawapo wa waanzilishi wa kituo cha haki ya kijamii ya Kayole. Kituo hiki kinafanya harakati dhidi ya unyasaji wa jinsia ukatili wa polisi.

Ubaguzi wa Vijana na Mapambano ya Kijamii

Image credit Mathare Social Justice Centre.

For English click here.

Chapisho hili limetoka kwa Ukiritimba wetu katika safu ya Jiji langu, kushirikiana na Kituo cha Haki ya Jamii cha Mathare jijini Nairobi.

Mimi ni Minoo. Nilizaliwa na kulelewa katika kijiji cha Mukuru. Nimeshuhudia aina zote za ukatili wa polisi na ubaguzi wa vijana, pamoja na hali ya umaskini. Nimekutana na vijana kutoka mitaa ya matajiri na ilikuwa wazi kuwa hawajapambana na hali kama hii ya ubaguzi. Hii ni dhibitisho kuwa umaskini ni uhalifu. Mabepari na serikali wanaohalifisha umaskini ndio wanatusukuma kwenye umaskini ili tunapoomba chakula wanavuna jasho letu na kutulipa pesa kidogo zaidi.

Niliamua kuweka rasta kwenye nywele zangu, ila kama mkaazi wa Mukuru Kwa Njenga, nilikuwa na hofu nyingi sana. Niliona jinsi wenzangu walikamatwa wakiwa na nywele zao za rasta, waliaandikiwa mashtaka ya uwongo ya kupatikana na bangi au matendo mengine ya uhalifu. Hali huo mbovu ya vijana umewafanya watu katika jamii pia kuwaona vijana wenye nywele ndefu za rasta kama wahalifu au wanaotumia dawa za kulevya. Nilishuhudia rafiki yangu Kaparo akinyolewa na kipande cha mabati katika kituo cha polisi. Walidai kuwa alikuwa amepigana na mwana wa jasusi wa polisi. Binamu yangu pia na rafiki zake saba walikamatwa kwa madai ya kuwa na bhangi. Yeye na wenzake wane walinyolewa na mapolisi wakitumia wembe moja kati yao. Waliandikiwa mashataka ya uongo kuwa walikuwa wakipanga kuiba. Ilibidii wazazi wao kutoa hongo ili waachiliwe. Mwaka wa 2019, vijana nane wa kiume walipigwa risasi na polisi walipokuwa na mkutano wa kujadiliana kuhusu ukusanyaji wa takataka. Walikuwa na umri kati ya miaka 16 -24.

Nilisomea shule ya msingi ya Mukuru Kwa Njenga iliyokuwa karibu na nyumbani. Shule hiyo ilikuwa na uwanja mkubwa ambao vijana wengi walitumia kucheza mchezo wa kandanda. Lakini, usiku uwanja huo ulikuwa kichinjio. Kijana mmoja aliyekuwa muuzaji wa kitambo wa bangi alipigwa risasi muda wa saa mbili usiku. Polisi walidai kuwa alikuwa mhalifu na kumwekea kadi nyingi za simu na risasi bandia (bonoko).

Kila usiku, hata wakati mwingine mchana, mimi huskia milio ya risasi kutoka kwenye uwanja. Sikupitia ukatili mwingi sana kama mwanamke lakini nimewaona vijana wenzangu wa kiume wakiteseka kila siku. Wakati mwingine, baba yangu husema anamshukuru Mungu kwa kutopata mtoto wa kiume, kisa na maana hajui jinsi angeweza kumlinda dhidi ya ukatili huu unaofanyika katika mitaa ya walalahoi.

Ni hatari kuwa na mavazi za bei ghali kwani inahatarisha maisha yako. Unaweza kushtakiwa kwa wizi na kupigwa kikatili. Najua rafiki zangu ambao hawawezi kuvaa vizuri kwa sababu wamewahi kuwa jela kwa miaka mingi. Hata baada ya kubadili mienendo yao, maafisa wa polisi bado wana mazoea ya kuwanyanyasa, kuwapiga kikatili wakidai kuwa wanataka kujua walikoiba nguo hizo.

Nimenusurika katika huu mtaa nikiona jinsi serikali inavyopata pesa kwa kukandamiza maisha yetu. Serikali inaeneza woga kwa kutumia vurugu na jela. Tunahisi hali ya athari mahali ambapo tunapaita nyumbani. Nina marafiki wasio na hatia wanaozorota gerezani. Kosa lao ni kuwa maskini na kuishi katika mtaa duni. Hatukuchagua hali hii ya maisha.

Mimi ni Maryanne Kasina. Nilizaliwa na kukuzwa Kayole. Nimekua katika jamii iliyojaa udhalimu na najua umaskini ni vurugu. Nilipokuwa shule ya msingi sikuelewa mbona Kayole kulijaa vurugu. Ndoa ya wazazi wangu iliharibika nilipokuwa shule ya upili. Hapo ikawa vigumu sana kutulea. Mamangu alikuwa na watoto kumi. Ilibidi tutoke shuke ya uma na kuenda shule ya kibinafsi iliyo ya bei ya chini ambayo mama angeweza kumudu. Shule ya kibinafsi mtaani ni za bei ya chini, kwa sababu hakuna walimu waliohitimu na mitambo kama maktaba na maabara.

Baada ya kumaliza shule ya upili, hali ilizidi kuharibika nyumbani. Nilifahamu kuwa sitapata karo ya kuendeleza masomo yangu. Tulilala njaa mara nyingi, na kama mtoto wa pili katika familia ya watoto kumi, ilibidi nitafute njia ya kupata chakula.

Rafiki yangu alinieleza kuhusu wakala fulani wa kunisafirisha nje ya nchi kufanya kazi. Nilijua hatari zilizoko. Nilikuwa nimeskia na kuona kwenye vyombo vya habari namna wafanyikazi walivyoona mateso na wakati mwingine hata kifo. Nilihofia sana lakini ilibidi niende. Wakala iliniarifu kuwa wamepata kazi ya uhudumu Dubai tarehe 13 Disemba, mwaka 2013. Mkataba ulikuwa wa miaka miwili. Visa na tikiti ya ndege pia nilipewa. Niliwauliza kama ni kweli nitafanya kazi kwenye hoteli kwa sababu nilihofia zaidi kufanya kazi ya nyumbani kwani wanapitia ukiukaji mwingi wa haki zao. Kilichonishangaza ni kuwa mkataba huu ulikuwa umeandikwa kwa lugha ya kiArabu, na hata hivyo ilibidi ni tie saini. Tarehe 15 Disemba, mwaka huo, nilisafiri kuenda Dubai. Nilipofika na kuelezwa kinachohitajika kwangu kama mfanyi kazi, mwili wangu uliganda na nikatamani kupata mabawa kurudi nchini kwangu. Nilitamani ardhi ipasuke nimezwe lakini wapi. Hali ya kufanya kazi ilkuwa mbovu zaidi.

Niliporudi sikujua kwa kuanzia, kwa maana kila kijana alitumani kuwa ningekuja kuwaoka katika hali zao duni. Walidhani nitawasaidia kupata kazi ngambo bila kujua jinsi hali ilivyo kama jehenamu.Tulikosa njia mbadala na kufadhaika kujimudu, tuliamua kutafuta njia nyingine ya kujimudu kupitia vikundi vya vijana.

Kikundi cha Gaza kilikuwa cha densi tulipokuwa shule ya upili.Tulishindana na mitaa jirani kwa michuano wa kirafiki. Baada ya kumaliza shule ya upili tulitawanyika wengine wakajiunga na vikundi vingine. Vikundi hivi vilifanya miradi ya kukuza jamii na kulinda mazingira. Harakati hizi zilitishia watu fulani, hivyo wakanza kuhusisha majasusi.

Walifanya hivi kwa kuwapea vijana silaha wapiganie ardhi ya matajiri. Vijana walidhani masiha yatabadilika kwani wangepata kipande cha ardhi ya kufanya ukulima na manyumba. Dhana hii iliwafanya kupiga vita hivi na wakashinda, lakini vita hivi vilikuwa vimechochezwa na mfumo. Baadaye, wakaanza kumalizwa, mmoja baada ya mwingine. Ardhi hiyo ilikuja kuuzwa kwa mamilionea wengine.

Nimepoteza rafiki zangu kwa mauaji ya polisi. Wengi niliokuwa nao wamezikwa. Tuliogopa sana kuonekana pamoja kwa hofu ya polisi kutuandama na kutupiga risasi sote, kutukamata ama kutuwekea mashtaka ya uongo ya uhalifu.

Mwaka wa 2017, Rais Uhuru Kenyatta alipeana amri ya kupiga risasi na kuua. Nilishangaa ni nani hawa ambao watauawa? Ni sisi vijana tuliohalifishwa na polisi na ata jamii, pamoja na wanasiasa walio na malengo ya kibinafsi? Sisi ambao tumekuwa mitambo ya kutoa pesa kwa polisi wanotunyang���anya mapato madogo tunayopata? Sisi tulio katika magereza kwa mashtaka ya uongo ya kuwa na bangi na kukosa kutoa hongo?

Idadi ya vituo vya polisi inashinda ya hospitali za uma katika mitaa duni. Serikali inatudhalilisha na kutuua kwa sababu wameshindwa kutupa mahitaji ya kimsingi. Mfumo wa upebari unawanufaisha wachache. Vijana wanapojipanga wanaingiza majasusi katika harakati zao.

Wengine wetu waliokuwa Gaza wanalipa polisi ili waishi. Wengi wetu ni wahasiriwa ama walionusuru haki ya mfumo huu kutojali. Wale ambao hawana uwezo wa kutoa hongo hawana amani. Polisi wauaji wanawaanika mtandaoni na kuwaua.

Nilikutana na Minoo mwaka wa 2018. Nilikuwa namsaidia kuanzisha kituo cha haki ya kijamii ya Mukuru.Tulijadiliana na rafiki wengine wa kike na kuanzisha shirika la wanawake walio kwenye vituo vya haki ya kijamii���Women in Social Justice Centres movement. Shirika hili inachukua hatua za kisiasa. Tunaunda nafasi salama ya watu wote waliokandamizwa. Vita dhidi ya ubepari vinaendelea. Tunafaa kuikumbatia itikadi ya kike kama njia ya kuelekea ujamaa, kurudi kwenye mizizi yetu na utu wetu.

Tunapoangazia maisha yetu na matukio yanaotokea duniani tumegundua kuwa hatuhitaji mageuzi katika idara ya polisi tu, lakini mageuzi ya mfumo wote. Bado tuko chini ya ukoloni. Bado hatujapata uhuru.

Waandishi:

Minoo Kyaa ni mwanachama wa kituo cha haki ya kijamii na Mukuru na kinara wa wanotumia muziki aina ya reggae kueneza haki ya kijamii. Ni mwanachama pia wa shirika la wanawake wa vituo vya haki ya kijamii. Ni mwandishi na mshairi. Sanaa yake inahati mapambano na upinzani.

Maryanne Kasian ni mwandishi na mpatanishi wa wanawake walioko kwenye vituo vya haki ya kijamii nchini Kenya. Yeye ni mojawapo wa waanzilishi wa kituo cha haki ya kijamii ya Kayole. Kituo hiki kinafanya harakati dhidi ya unyasaji wa jinsia ukatili wa polisi.

Most of the friends I grew up with are dead

Image credit Mathare Social Justice Centre.

This post is from our Capitalism in My City series, a collaboration with the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, Kenya.

I, Minoo, was born and raised in Mukuru slums and witnessed all sorts of police brutality and criminalization of young people by the state. It wasn���t just the criminalization of youths but the criminalization of poverty too. I have interacted with youths that come from rich backgrounds, and they cannot relate to a thing when we talk about how youths have been criminalized, and that proves to me that poverty is criminalized. Yet, the capitalists and the state that criminalizes is the same one that pushes us to poverty, so that when we beg them for food, they exploit our labor and give us peanuts in return.

While growing up in Mukuru Kwa Njenga, I decided to grow dreadlocks, but had a lot of fear in me. I had seen how my friends got arrested for simply having dreadlocks: they were framed for possessing bhang (marijuana) or wrongfully accused of being criminals. The negative profiling by police was so bad that even the community started to believe that if you have dreadlocks you were using drugs or were a dangerous criminal. I witnessed my friend Kaparo get his dreadlocks shaved off by police at the police station using a piece of iron sheet. He had been brought there by police informants for fighting with the son of a police informant. My cousin is also a victim of this type of police brutality. He and seven of his friends were found with bhang and five of them, including my cousin, had their head shaved using a blunt razor that was shared among all of them. They were also framed for meeting to organize a robbery, and their parents had to pay a bribe for their innocent sons to be freed. Still in Mukuru, eight young men were shot in 2019 by the police while having a meeting about garbage collection. They were between 16 and 24 years old.

I attended Mukuru Kwa Njenga primary school, which was near my home. It had a very big field where young men loved to go to practice football. At night, however, the field would turn into a slaughter place. A young man I knew who used to sell bhang but stopped was shot there around 8 pm going to buy bhang from another peddler. To justify the inhumane action, the police framed him as a robber by placing many phone sim cards at the crime scene, and a fake gun���a bonoko.

Every night and sometimes during the day, I would hear a lot of gunshots coming from the field. I didn’t experience much police brutality as I am a woman, but I watched my male friends suffer every day. I even heard my dad thank God that he didn’t have a son because he didn’t how he would protect him from the criminalization that happens when you grow up in a slum.

It���s even dangerous to have an expensive gadget here as it puts your life in danger. You will be accused of stealing it and be brutally beaten. I know some of my friends who can’t dress well because they were once in crime, stayed in prison for years, and when they came out they reformed but the police will not give them peace: they are always harassing them, brutally beating them so that they can say where they ���stole��� their clothes from.

I survived in this ghetto watching the state making a living out of extorting us, turning our lives into a living hell. The state installs a lot of fear in us using violence and prisons. We even feel unsafe in a place we call home. I have innocent friends who rot behind bars for the crime of being poor and living in a slum. We didn’t choose this life.

Image credit Mathare Social Justice Centre.

Image credit Mathare Social Justice Centre.I, Maryanne Kasina, was born and raised in Kayole, a poor area in Nairobi. I have grown-up in a society full of injustices, and I know poverty is violence. During my primary school years, I could not understand why the violence was rampant in Kayole. When I was in high school, my parents separated, and it became hard to raise us. My mother had ten children, so things had to change. We were transferred from a public school to the cheapest private school she could afford. Private schools in the ghetto are cheap due to the lack of qualified teachers and the lack of school equipment such as laboratories and libraries.

After I completed my secondary schooling, things were worse at home. I knew we couldn’t afford school fees to continue with my studies: we slept many days on an empty stomach, and since I am the second born in a family of ten, I had to look for something to do which could put food on the table.

A friend of mine told me about an agency that would take me abroad to work. I knew the risks: I used to hear and could see in the media how workers were mistreated, tortured, and sometimes killed. It gave me a lot of fear, but I had to go. The agency told me they had gotten me a waitressing job in Dubai starting on December 13, 2013; a contract of two years, a visa and a plane ticket. The funny thing is that everything I was told to sign was in Arabic; I asked the agency if I was going to work in a hotel because what I feared most was to work as a domestic worker because of the violations they face. They told me I was going to work in a hotel. On December 15, 2013 I left for Dubai, and when I got there, the agency briefed me that what was expected of me was to work in a private house. I froze and wished I had wings to fly and go back to my country. I wished the world could break apart and swallow the whole me, but all was in vain. I ended up staying for two years. The working conditions were excruciating.

When I came back in 2015, I did not know where to begin since every young person I knew felt I was a savior and wanted me to help them go abroad not knowing how hellish it was. Because of no alternatives and the frustrations of survival, we decided to seek the alternative for ourselves through youth groups.

Gaza group was a dancing crew when we were in high school. We used to compete with other neighborhoods in friendly dance competitions. It helped us come together. After completing high school, we broke up and some of us joined existing youth groups. These groups started to do community development and ecological justice work. Their organizing threatened the system and so the system infiltrated them.

How did they do this? By giving them weapons,”bunduki,” to fight over a tycoon’s land. This time they felt life would be different as they would have housing and a plot of land to do farming. Because this was their hope, they fought for the land and won the war but because it was a war instigated by the system, the system started to shoot them one by one. The land which they fought for was sold to millionaires.

I have lost my friends through police executions. Most of the friends I grew up with are 6 feet under. It reached a point we feared sitting together because the police would storm anywhere youths were gathered and either shoot all of you or arrest you and accuse you of criminal activity.

In 2017, President Uhuru Kenyatta gave a ���shoot to kill��� order. I wondered who was to be killed? Was it us the youth who had been criminalized by police and society, then armed by politicians for selfish interests? Was it us, the youth, who had been turned into walking ATM machines for the police, squeezing from us the little that we toil to earn? Was it us, the youth, who are serving prison sentences for possession of bhang because they failed to give the police a bribe?

There are more police stations than public hospitals in the informal settlement. It is to brutalize us and kill us because it has failed to provide basic need to all humans. Since the capitalist system is a system to benefit a few, what the system does is when youths organize themselves, they infiltrate their organizations.

Some of those from the Gaza crew who reformed have to pay police to stay alive. Most of us are victims or survivors of system impunity, and those who cannot afford to give the bribe have no peace: the police vigilantes profile them on social media and kill them.

When we give birth that’s labor but the system is eating our children. It’s time we all arise, it is time women stop giving birth until the environment becomes conducive for all of us. The world is not safe until we make it safe.

I met Minoo in 2018. I was helping her and other comrades set up Mukuru Community Justice Centre. During our groundings with other female comrades, we were able to consolidate our struggle and form the Women in Social Justice Centres movement, a feminist workers movement whose struggle is through political action. In this space, we want to create a safe space for all oppressed human beings. The fight against patriarchy and capitalism continues. We all need to embrace feminism as an ideology towards socialism, getting back to our roots and our humanity.

In our reflections on our lives and the unfolding world events, we realized we do not need police reforms but total change of the system. We are still colonized. It is not yet uhuru.

Most of the friends I grew up are dead

This post is from our Capitalism in My City series, a collaboration with the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, Kenya.

I, Minoo, was born and raised in Mukuru slums and witnessed all sorts of police brutality and criminalization of young people by the state. It wasn���t just the criminalization of youths but the criminalization of poverty too. I have interacted with youths that come from rich backgrounds, and they cannot relate to a thing when we talk about how youths have been criminalized, and that proves to me that poverty is criminalized. Yet, the capitalists and the state that criminalizes is the same one that pushes us to poverty, so that when we beg them for food, they exploit our labor and give us peanuts in return.

While growing up in Mukuru Kwa Njenga, I decided to grow dreadlocks, but had a lot of fear in me. I had seen how my friends got arrested for simply having dreadlocks: they were framed for possessing bhang (marijuana) or wrongfully accused of being criminals. The negative profiling by police was so bad that even the community started to believe that if you have dreadlocks you were using drugs or were a dangerous criminal. I witnessed my friend Kaparo get his dreadlocks shaved off by police at the police station using a piece of iron sheet. He had been brought there by police informants for fighting with the son of a police informant. My cousin is also a victim of this type of police brutality. He and seven of his friends were found with bhang and five of them, including my cousin, had their head shaved using a blunt razor that was shared among all of them. They were also framed for meeting to organize a robbery, and their parents had to pay a bribe for their innocent sons to be freed. Still in Mukuru, eight young men were shot in 2019 by the police while having a meeting about garbage collection. They were between 16 and 24 years old.

I attended Mukuru Kwa Njenga primary school, which was near my home. It had a very big field where young men loved to go to practice football. At night, however, the field would turn into a slaughter place. A young man I knew who used to sell bhang but stopped was shot there around 8 pm going to buy bhang from another peddler. To justify the inhumane action, the police framed him as a robber by placing many phone sim cards at the crime scene, and a fake gun���a bonoko.

Every night and sometimes during the day, I would hear a lot of gunshots coming from the field. I didn’t experience much police brutality as I am a woman, but I watched my male friends suffer every day. I even heard my dad thank God that he didn’t have a son because he didn’t how he would protect him from the criminalization that happens when you grow up in a slum.

It���s even dangerous to have an expensive gadget here as it puts your life in danger. You will be accused of stealing it and be brutally beaten. I know some of my friends who can’t dress well because they were once in crime, stayed in prison for years, and when they came out they reformed but the police will not give them peace: they are always harassing them, brutally beating them so that they can say where they ���stole��� their clothes from.

I survived in this ghetto watching the state making a living out of extorting us, turning our lives into a living hell. The state installs a lot of fear in us using violence and prisons. We even feel unsafe in a place we call home. I have innocent friends who rot behind bars for the crime of being poor and living in a slum. We didn’t choose this life.

I, Maryanne Kasina, was born and raised in Kayole, a poor area in Nairobi. I have grown-up in a society full of injustices, and I know poverty is violence. During my primary school years, I could not understand why the violence was rampant in Kayole. When I was in high school, my parents separated, and it became hard to raise us. My mother had ten children, so things had to change. We were transferred from a public school to the cheapest private school she could afford. Private schools in the ghetto are cheap due to the lack of qualified teachers and the lack of school equipment such as laboratories and libraries.

After I completed my secondary schooling, things were worse at home. I knew we couldn’t afford school fees to continue with my studies: we slept many days on an empty stomach, and since I am the second born in a family of ten, I had to look for something to do which could put food on the table.

A friend of mine told me about an agency that would take me abroad to work. I knew the risks: I used to hear and could see in the media how workers were mistreated, tortured, and sometimes killed. It gave me a lot of fear, but I had to go. The agency told me they had gotten me a waitressing job in Dubai starting on December 13, 2013; a contract of two years, a visa and a plane ticket. The funny thing is that everything I was told to sign was in Arabic; I asked the agency if I was going to work in a hotel because what I feared most was to work as a domestic worker because of the violations they face. They told me I was going to work in a hotel. On December 15, 2013 I left for Dubai, and when I got there, the agency briefed me that what was expected of me was to work in a private house. I froze and wished I had wings to fly and go back to my country. I wished the world could break apart and swallow the whole me, but all was in vain. I ended up staying for two years. The working conditions were excruciating.

When I came back in 2015, I did not know where to begin since every young person I knew felt I was a savior and wanted me to help them go abroad not knowing how hellish it was. Because of no alternatives and the frustrations of survival, we decided to seek the alternative for ourselves through youth groups.

Gaza group was a dancing crew when we were in high school. We used to compete with other neighborhoods in friendly dance competitions. It helped us come together. After completing high school, we broke up and some of us joined existing youth groups. These groups started to do community development and ecological justice work. Their organizing threatened the system and so the system infiltrated them.

How did they do this? By giving them weapons,”bunduki,” to fight over a tycoon’s land. This time they felt life would be different as they would have housing and a plot of land to do farming. Because this was their hope, they fought for the land and won the war but because it was a war instigated by the system, the system started to shoot them one by one. The land which they fought for was sold to millionaires.

I have lost my friends through police executions. Most of the friends I grew up with are 6 feet under. It reached a point we feared sitting together because the police would storm anywhere youths were gathered and either shoot all of you or arrest you and accuse you of criminal activity.

In 2017, President Uhuru Kenyatta gave a ���shoot to kill��� order. I wondered who was to be killed? Was it us the youth who had been criminalized by police and society, then armed by politicians for selfish interests? Was it us, the youth, who had been turned into walking ATM machines for the police, squeezing from us the little that we toil to earn? Was it us, the youth, who are serving prison sentences for possession of bhang because they failed to give the police a bribe?

There are more police stations than public hospitals in the informal settlement. It is to brutalize us and kill us because it has failed to provide basic need to all humans. Since the capitalist system is a system to benefit a few, what the system does is when youths organize themselves, they infiltrate their organizations.

Some of those from the Gaza crew who reformed have to pay police to stay alive. Most of us are victims or survivors of system impunity, and those who cannot afford to give the bribe have no peace: the police vigilantes profile them on social media and kill them.

When we give birth that’s labor but the system is eating our children. It’s time we all arise, it is time women stop giving birth until the environment becomes conducive for all of us. The world is not safe until we make it safe.

I met Minoo in 2018. I was helping her and other comrades set up Mukuru Community Justice Centre. During our groundings with other female comrades, we were able to consolidate our struggle and form the Women in Social Justice Centres movement, a feminist workers movement whose struggle is through political action. In this space, we want to create a safe space for all oppressed human beings. The fight against patriarchy and capitalism continues. We all need to embrace feminism as an ideology towards socialism, getting back to our roots and our humanity.

In our reflections on our lives and the unfolding world events, we realized we do not need police reforms but total change of the system. We are still colonized. It is not yet uhuru.

Society as we know it

Image credit KC Nwakalor for USAID via Flickr CC.

On June 4, 2020, a Twitter user asked: ���why is ending rape so contentious and controversial? Why is it generating so much disagreement?��� The Nigerian writer, editor, and activist, OluTimehin Adeagbeye quoted the tweet and responded:

It���s contentious because ending rape means ending society as we know it. Rape is the primary tool used to keep women in check plus the ultimate manifestation of men���s unchecked power in patriarchy. How do you curtail women you can���t control? And how do you control women you can���t rape?

The entitlement to a woman���s body���and life���is considered the glorious trophy of masculinity. It is sad that this myth has been at the core of Nigerian society���s view of femininity for centuries and we are refusing to let go of it.

At the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the Nigerian government imposed lockdowns at different levels. For five weeks Nigerians were told to stay at home. One of the social souvenirs of this period was a surge in rape and domestic violence.

On Nigerian Twitter, this has triggered the #WeAreTired campaign, championed primarily by women who feel the burning need to address the normalized culture of rape. It spilled into physical protests too. However, despite the preponderance of rape and the recent shocking examples in the rape and murder of a University of Benin undergraduate and other cases, the protest met a rigid sandbag in counter-protests such as #NotAllMen and in systemic sabotage involving police officials who requested ���mobilization fees��� from citizens before doing their job. This act is commonplace���as the police are underfunded, understaffed, mindlessly corrupt, and misogynistic���and provides many opportunities for rapists and sex offenders to evade justice.

All of this boils down to one thing: Rape is not recognized as a big deal. After all, sex is not a big deal. In a country of anyhowness, the Nigerian condition of passive acceptance, and rigid gender inequality, rape can hardly pass the audition in spite of our judicial charade which determines which laws are relevant and which are not.

Simply put, the majority of Nigerians do not understand rape and with this lack of proper understanding little can be achieved. This might seem a harsh generalization but looking at our engagement with the issues of rape and rape culture, there is no denying the near general consensus that rape is a misdemeanor and not a serious violation.

First, rape is a crime. A crime is an action that deserves to be duly punished. It is high time this knowledge found its way into the Nigerian curriculum and social education which glorify patriarchy and undermine a level playing field for both genders. Decades of pervasive ugly norms surrounding rape in Nigeria have made it almost impossible for us to critically engage with rape and rape culture in an honest and open manner.

I once came across a thread on Facebook where a female user posted a question that is common in the ���what if��� imagination of Nigerians. The internet user posted: ���What if your boss rapes you and gives you two million naira?������ The majority of people who commented on this post were women who approved of this kind of imagined scenario, and who saw the offered bribe for silence as a way for economic uplift rather than an attempt to hush the victim. Not a single person made mention of the bribe, or the fact that a crime would have been committed and a rapist would be at large.

Looking at our justice system, it is on record that only a handful of sexual abuse and rape cases have been successfully tried across the whole country. As of 2019, only an estimated 65 rape convictions have been recorded in Nigeria���s legal history, after almost 60 years of independence. This mirrors the internalized misogyny of the justice system and is largely an adverse effect of cultural and religious influence that has seeped into it, not to mention the legacy of colonial jurisprudence.

Rape is a silent epidemic the country faces but nobody in power wants to tackle it. This is because, as Adegbeye said, it will change the society as we know it. An end to rape culture will signal the end of male dominance which has been tightly woven into our consciousness. When you cannot subdue women sexually, there is nothing for you to lay claim to. Rapists and rape apologists understand this; the system knows this.

The few stories that get told like those provided by Mirabel Sexual Assault Referral Centre show that rape is not abating despite protests and mass sensitization. According to a recent survey, one in three Nigerian girls has experienced sexual assault before turning 25. The inertia of the system and failure of the police to investigate these crimes means that ordinary citizens are forced to advocate and raise awareness via social media.

The society as we know it must now be radically disrupted and given a new face, one that assures justice and equality. Nigeria is far behind and women pay the heaviest price.

The society as we know it

Image credit KC Nwakalor for USAID via Flickr CC.

On June 4, 2020, a Twitter user asked: ���why is ending rape so contentious and controversial? Why is it generating so much disagreement?��� The Nigerian writer, editor, and activist, OluTimehin Adeagbeye quoted the tweet and responded:

It���s contentious because ending rape means ending society as we know it. Rape is the primary tool used to keep women in check plus the ultimate manifestation of men���s unchecked power in patriarchy. How do you curtail women you can���t control? And how do you control women you can���t rape?

The entitlement to a woman���s body���and life���is considered the glorious trophy of masculinity. It is sad that this myth has been at the core of Nigerian society���s view of femininity for centuries and we are refusing to let go of it.

At the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the Nigerian government imposed lockdowns at different levels. For five weeks Nigerians were told to stay at home. One of the social souvenirs of this period was a surge in rape and domestic violence.

On Nigerian Twitter, this has triggered the #WeAreTired campaign, championed primarily by women who feel the burning need to address the normalized culture of rape. It spilled into physical protests too. However, despite the preponderance of rape and the recent shocking examples in the rape and murder of a University of Benin undergraduate and other cases, the protest met a rigid sandbag in counter-protests such as #NotAllMen and in systemic sabotage involving police officials who requested ���mobilization fees��� from citizens before doing their job. This act is commonplace���as the police are underfunded, understaffed, mindlessly corrupt, and misogynistic���and provides many opportunities for rapists and sex offenders to evade justice.

All of this boils down to one thing: Rape is not recognized as a big deal. After all, sex is not a big deal. In a country of anyhowness, the Nigerian condition of passive acceptance, and rigid gender inequality, rape can hardly pass the audition in spite of our judicial charade which determines which laws are relevant and which are not.

Simply put, the majority of Nigerians do not understand rape and with this lack of proper understanding little can be achieved. This might seem a harsh generalization but looking at our engagement with the issues of rape and rape culture, there is no denying the near general consensus that rape is a misdemeanor and not a serious violation.

First, rape is a crime. A crime is an action that deserves to be duly punished. It is high time this knowledge found its way into the Nigerian curriculum and social education which glorify patriarchy and undermine a level playing field for both genders. Decades of pervasive ugly norms surrounding rape in Nigeria have made it almost impossible for us to critically engage with rape and rape culture in an honest and open manner.

I once came across a thread on Facebook where a female user posted a question that is common in the ���what if��� imagination of Nigerians. The internet user posted: ���What if your boss rapes you and gives you two million naira?������ The majority of people who commented on this post were women who approved of this kind of imagined scenario, and who saw the offered bribe for silence as a way for economic uplift rather than an attempt to hush the victim. Not a single person made mention of the bribe, or the fact that a crime would have been committed and a rapist would be at large.

Looking at our justice system, it is on record that only a handful of sexual abuse and rape cases have been successfully tried across the whole country. As of 2019, only an estimated 65 rape convictions have been recorded in Nigeria���s legal history, after almost 60 years of independence. This mirrors the internalized misogyny of the justice system and is largely an adverse effect of cultural and religious influence that has seeped into it, not to mention the legacy of colonial jurisprudence.

Rape is a silent epidemic the country faces but nobody in power wants to tackle it. This is because, as Adegbeye said, it will change the society as we know it. An end to rape culture will signal the end of male dominance which has been tightly woven into our consciousness. When you cannot subdue women sexually, there is nothing for you to lay claim to. Rapists and rape apologists understand this; the system knows this.

The few stories that get told like those provided by Mirabel Sexual Assault Referral Centre show that rape is not abating despite protests and mass sensitization. According to a recent survey, one in three Nigerian girls has experienced sexual assault before turning 25. The inertia of the system and failure of the police to investigate these crimes means that ordinary citizens are forced to advocate and raise awareness via social media.

The society as we know it must now be radically disrupted and given a new face, one that assures justice and equality. Nigeria is far behind and women pay the heaviest price.

July 6, 2020

The existing order of things

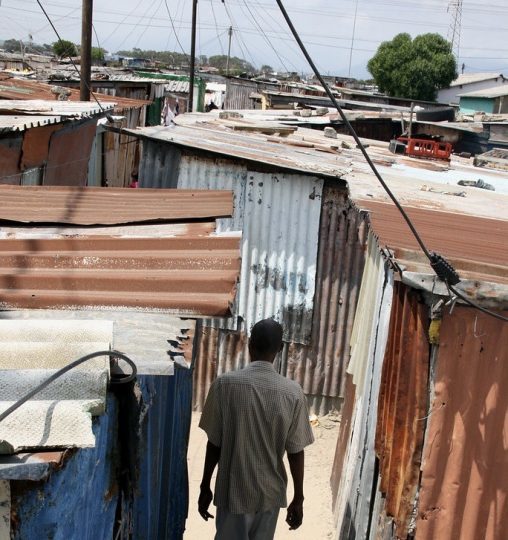

Khayelitsha. Image credit

Michiel Van Balen via Flickr CC.

Last week, South Africans were up in arms after a video surfaced depicting a black man, Bulelani Qholani, being violently evicted from his shack by four law enforcement officers in Khayelitsha, a large township on the outskirts of Cape Town. What distinguished this moment of evictions from all the rest that South Africans are used to is that Qholani was naked���and what are usually unnoticed acts of ordinary cruelty became a recorded episode of spectacular dehumanization. While the anger stirred is warranted, at times it���s implied in the talk about the indignity suffered by Qholani that the real problem is that he did not have clothes on���almost as if to say that evictions are fine if they are done humanely.

Cape Town���s police force has become notorious for evictions, clashing recently with black and coloured residents in a poor part of Hout Bay, a wealthy area on the city���s southern edge. And while the four law enforcement officers that assaulted Qholani were suspended after the video went viral, the city of Cape Town has defended the eviction order, claiming that the housing structures constituted an ���illegal land invasion.��� Never mind that this land belongs to the city of Cape Town itself; this language is not so far off from what we���ve heard before. Not just from the Democratic Alliance (DA) government which governs the Western Cape with an expected indifference to poor black and coloured South Africans (the mayor of Cape Town, also a member of the DA, shamelessly claimed Mr. Qholani���s nakedness was planned so as to embarrass the city), but from the ruling African National Congress which came to power on the hopes that it genuinely cared about the marginalized.

In South Africa, we have historically never been able to think of land as anything but a commodity, a means for facilitating the exploitation of labor (by accommodating and reproducing that labor), or something to be exploited itself (aided by that exploited labor). Any ���unproductive��� use of land���used as simply a site for a home, or as a site where one could independently produce their own subsistence���had to come to an end. And so, the story of colonialism and apartheid is the story of the dispossession of black people from their land and eviction from their homes. It���s a story that���s remained unchanged in plot, shifting only its storytellers.

If there is one manifestly public exercise of power definitive of the South African condition, past and present, it is that of the eviction. That these scenes of breathtaking cruelty are continuous with familiar ones from the apartheid regime, serve both to give us a ready understanding of the horror involved in materially depriving someone of a home, but also add to the success of the eviction as a technology of power because what it represents is so recognizable that we are predisposed to accepting that it will happen; all that changes is why it happens and whether or not we are willing to accept that.

The legitimacy of evictions in South Africa then becomes strictly a technical matter���whether they are lawful or unlawful, whether those carrying them out act reasonably or not. Once again, what seems to matter is that you have the legal authority to conduct the eviction, and that the eviction happens in a way consistent with the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The apartheid regime thrived on this kind of mystification, of obscuring unequal power relations in the guise of an instrumental rationality which makes us concerned with the proper processes of things and not what ends they are serving. But as we now understand, this isn���t exceptional to apartheid, it is how capitalism functions. And contemporary South African capitalism learned from its predecessors an effective regime of exclusion, a means of determining which lives matter and which ones don���t.

The denial of a home and shelter, even ones thrifted together in an act of hasty desperation���is to deny people any sliver of rootedness, any anchor and refuge in their life. It is a denial of citizenship, what Hannah Arendt called ���the right to have rights.��� It is to make refugees of the South African poor, moderating slightly from the apartheid regime which once made total foreigners of them. Contrary to the Freedom Charter which declared sixty-five years ago last month that ���South Africa Belongs to All Who Live In It,��� it doesn���t���but more importantly, it can���t.

The majority of the South African population has to be rendered illegible to the state in order to drive their cheap hyper-exploitation. To successfully deliver social goods to people such as adequate housing, safe and accessible transportation, and decent schooling���where the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the pattern of post-apartheid segregation the most���is to provide the basis from which they can continue to assert their rights and interests. It is to threaten the viability of the South African model of accumulation which depends on a regime of exclusion that literally makes people, basically black people, their lives and their histories easily expendable, at the whim of capital and its changing demands. The worry is not that the masses will get too comfortable and become idle freeloaders, the worry is that the masses will develop their strength. It is to fear that people will realize that democracy should not simply mean getting to choose your leaders, but having the means to exercise real control over your life and its destiny.

The more we ask, the more we plead with the government to do its job (and if they don���t, marching to the courts to compel them to), the more the government gets comfortable with the idea that it has to be asked��� that it is doing the people a favor. The South African ruling class has been waging a protracted war against poor South Africans, having grown comfortable with the idea that the poor and working class have more or less accepted the existing order of things. Indeed, how do you fight back without a roof over your head, or without food to eat? As we enter the next phase of the pandemic, with the months ahead of us heralding austerity and the months behind us characterized by evictions, hunger and death, the words of C.L.R James are already proving relevant: ���When history is written as it ought to be written, it is the moderation and long patience of the masses at which men will wonder, not their ferocity.���

A deafening salvo

Chimurenga: Pan African Space Station at the Vera List Center Forum 2019, Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, The New School, October 23-25, 2019. Image credit Jordan Rathkopf, courtesy Vera List Center for Art and Politics.

In January 1977, over 16,000 artists and musicians from all over the black world, including the United States and Europe, came together in Lagos, Nigeria, for Festac 77, an event paid for by Nigeria���s military government. For one month, the artists took photographs, made music, and put on plays. What resulted was a flawed though remarkable event, which at the time art historian Robert Farris Thompson described as a sort of creative nexus where ���such men and women are operating in terms of total black victory in which disparates have been conjured into co-existence from an overriding idea of utmost reconciliatory power.���

Four decades have elapsed since the festival, which is ample time for not just a renewed appraisal of the gathering in terms of its significance but also a moment to reflect on some of the politico-historical dynamics of the era that compelled Nigeria to gamble its reputation with a high stakes project despite its many socio-economic issues and a fractious internal political landscape. Since then, Nigeria, the region, the continent and global pan-African sphere have undergone mutations in ways not even the most prescient of dreamers could have envisioned.

Surprisingly, Festac���s legacy is a paucity of written memoirs documenting a gathering that congregated some of the continent and its diaspora���s brightest filmmakers, photographers, dramatists, musicians, dancers, poets, writers, and activists. As Ntone Edjabe, the Cameroonian-South African founder and editor of the South African collective Chimurenga summarizes it: ���The people who experienced Festac seemed unwilling to write it, as if bound by an unspoken nondisclosure agreement. And so its stories circulated in the manner of a family secret���a family of millions of people.���

Now Chimurenga has fired the opening salvo in effort to redeem this important chapter in history with a publication that is as much a treat for polyglots as cultural historians. The hydra-headed Cape Town outfit, which describes itself as ���a project-based mutable object,��� is equal parts creative laboratory, bookstore, and digital archive, and has conjured projects including Chimurenga magazine, The Chronic Gazette, African Cities Reader series, and the Pan-African Space Station (P.A.S.S.). With the publication of Festac ���77, the Chimurenga collective shift their gaze from Laurent-D��sir�� Kabila���s 2001 assassination in Kinshasa (Who Killed Kabila I & II) to the blackest and largest ever gathering of artists from Africa and its diaspora in 1977 in Lagos. Festac ���77 distinguishes itself by engaging texts and subjects that speak to a global pan-African aesthetic and spirit that seemed to have retreated to the underground in the 1980s, as geo-strategic feuds, neoliberal evangelists, and the development-industrial-complex (DIC) found fertile ground across the globe.

The publication is an amalgamation of meticulous curation and robust research. And if proximity is blurring, then space and time has afforded the Chimurenga team enough distance to resurrect a seminal gathering whose impact continues to stimulate conversations amongst its intended audience, one that stretches across the continent, and beyond the Indian and Atlantic oceans. In an interview with Kwanele Sosibo of the South African newspaper the Mail & Guardian, Edjabe points out that the Chimurenga team wouldn���t have had access to some of the material compiled in the publication without taking the time to build trust in networks in places they���d never visited. ���We���re fortunate to have brilliant researchers like Stacy Hardy, Graeme Arendse, Duduetsang Lamola, and Ben Verghese in the group. We used side projects to advance the research���for instance we published an issue of The Chronic in 2015 that examines divisions between north and sub-Saharan Africa, a central issue at Festac. Through such prepublications we were able to gather and produce material on some of the key questions of our research.���

But Festac ���77 is much more than a retrospective and readers needn���t teleport themselves to late 1970s Lagos, with detours in Dakar and Algiers, to experience the events captured in its bulky pages. Instead they���ll find details about the geo-political rivalries that resulted in Nigeria���s decision to host the gathering despite being just seven years removed from a costly civil war, the images of which would set the standard for an expanding Western global media particularly fixated on negative images of the continent. It provides rare insights into the cultural and ideological divisions that marked the lead up to the festival���s organization. Africans states were still mildly tipsy from a previous decade when new flags and anthems seemed to promise a new dawn; one which merely two years earlier had just witnessed Samora Machel���s Mozambique gain independence from Portugal, but also one in which Ian Smith���s Rhodesia was still under its white minority rule, where dreams of Namibian independence hadn���t taken as much form, and in which a few months later, Steve Biko was murdered by apartheid police. It is fitting that the contributors, many born around that time, have had the distance and are now old enough to appraise the vanquished promises and fleeting moments of hope that marked their entry into the world, and if older, their coming of age.

Readers will emerge from the image-filled Festac��� 77 with perhaps more questions than answers, especially against the backdrop of a resurgent US based Black Lives Matter movement. They may wonder if a similar gathering today could mobilize the proverbial ���family of millions��� the way South African apartheid mobilized their predecessors. Would the host country have the resources to undertake the task without the backing of a cast of multinationals brandishing the ���Africa rising��� narrative? Would the gathering remain grounded in its pan-African ideals or would it assume an Afropolitan character? Or would the substance and revolutionary spirit of a bygone era as represented by the former be replaced with stylish signifiers lacking in substance?

These and similar questions will likely arise as readers peruse the snapshots of a world that no longer exists, a portal in which they���ll discover previously little known details about its planning, the shifting cast of stakeholders, and the many false starts that marred its launch. They���ll find details like Nigeria���s resistance to Senegalese poet president L��opold S��dar Senghor���s attempts to inflect the Lagos gathering with n��gritude sensibilities; allegations attributing General Yakubu Gowon���s 1975 overthrow to his government���s mishandling of Festac���s preparations; they will read how the Nigerian government circumvented Britain���s reluctance to return the looted royal Benin mask by commissioning a replica from Benin craftsmen for use as the gathering���s icon, subverting the Western art world���s obsession with the concept of originality; they���ll read Guinean president Ahmed S��kou Tour�����s speech at the gathering in which he affirms his country���s autonomy on continental and global issues, but above all, its position on the Palestinian question.

But readers will also find details like Fela Kuti���s objection to the festival and his decision to host a jam session���of course, unrecorded���at his African Shrine that included guests of Festac, including Brazilians Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, Hugh Masekela and Stevie Wonder, and in the process, infuriating the military government of General Olusegun Obasanjo. Former Egypt 80 drummer Tony Allen, who died earlier this year of COVID-19, believed Fela���s dismissive stance towards the festival is the reason the Obasanjo government ordered soldiers to raid Kalakuta Republic the following month, resulting in the death of Funmilayo Anikulapo-Kuti, Fela���s mother, and subsequently the birth of the song, ���Coffin for Head of State.���

According to Edjabe, the festival also resulted in the recording of about 40 other albums, a vast amount when compared to the miniscule volume of writing about it. There were also poems by Audre Lorde and Jayne Cortez, an essay by Wole Soyinka, and historian Andrew Apter���s anthropological book length project, which in his view is intriguing given the number of notable artists, thinkers, and writers that congregated in Lagos.

There���s no doubt that Chimurenga���s Festac ���77 will fill the narrative void about an event that was significant, and its effort must be commended for shattering the silence that governs aspects of our recent history.

July 5, 2020

The Niger Delta, oil, and Trump���s America

Activists from Enviromental Rights Action in Nigeria and Socialist Youth League of Norway explore oil damages in the Niger Delta, April 2010. Image via Sosialistisk Ungdom Flickr CC.

In June 2020, the Trump administration, using the COVID-19 pandemic as an excuse, began to accelerate the rollback of major environmental regulations in the United States. On June 5, Trump signed an executive order aimed at weakening the National Environmental Policy Act, reducing the effectiveness of the Clean Air Act and effectively opening the door for more pollution in the country. The Executive Order accelerates the construction of pipelines and other energy projects without consideration for environmental impact assessments. This new weakening of environmental regulations comes in the wake of many such executive orders, often targeted at weakening protections not only for the environment but blacks and people of color who live in many communities often affected by environmental pollution.

The Trump administration���s disregard for the environment was not new���in 2018, climate scientists, environmentalists and close watchers of the oil industry were once again reminded of the dangers of the Trump presidency to climate concerns when the then Interior Secretary, Ryan Zinke, proposed a vast expansion of oil drilling in the Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic oceans���ending many years of moratoriums on oil drilling in these sites. This followed similar actions regarding the opening up of sacred sites and sites of national monuments to drilling and mining activities across the US. Sites such as The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) in Alaska and others are part of this drilling everywhere initiative. Recently, I���ve been pondering over three interrelated issues���the current protests against the incessant murder of blacks in the US, the Dakota Access Pipelines, and the oil rich Niger Delta region of Nigeria.

These three issues speak to the ways in which blacks and people of color, especially Native Americans in North Dakota, continue to bear the brunt of environmental disasters created by big corporations with the help of policies by the Trump administration the same way that the oil corporations shape policies in Nigeria through their alliance with the Nigerian government. The Black Lives Matter movement is not just about police brutality, but also the brutality daily perpetrated on the environment in which they all live across the world. From the swampy oil polluted Niger Delta in Nigeria to the neglected and polluted environment in the city of Detroit and the poisoned water in Flint, Michigan���the imprint of neglect and abandonment by our governments in favor of big corporations has made the environment where black and people of color live one of the most unbearable in the world.

Today, environmental pollution which disproportionately affects black people continues to be one of the most pressing realities of our time. For example, for over 50 years, oil-related contamination has been a constant reality for the people of the Niger Delta who experience regular oil spills, preponderance of acid rain as a result of gas flaring and other activities of oil corporations. As activists in North Dakota continue to protest the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), police brutality, and other forms of injustices against blacks and people of color in the US continue. There is a connection between the struggles for environmental justice in Nigeria, the protests led by the people of Sioux Rock, and those organized by Black Lives Matter.

Beginning in 1956, when the first oil consignment was shipped to the international market, the economy of the Niger Delta has shifted away from agriculture to become defined by oil production. At the center of this significant change are the people of the Niger Delta, whose lives, livelihoods, and cultural practices depend on the lands and waters where oil is extracted. Displacement from traditional livelihoods, the destruction of sacred sites, and the pollution of the environment have resulted in many years of protests and sometimes armed struggle. The 12-day revolution led by Isaac Adaka Boro in the 1960s marked the beginning of a long and protracted fight for recognition by the people of the Niger Delta. Non-violent protest groups formed, such as the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People (MOSOP). In 1995, Ken Saro Wiwa, the leader of MOSOP and a renowned international playwright, was killed by the Nigerian State after standing up to Shell and other multinational oil corporations. By 2005, new movements emerged, such as the Movement for Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND). This violent insurgency group claimed to represent the interests of all Niger Delta people in their struggle against corporations and the Nigerian state. The insurgency still continues today, though on a smaller scale, mostly overshadowed by the Boko Haram insurgency in the northeast of Nigeria. Insurgency in the Niger Delta is today largely mitigated by monthly ���amnesty payments��� to former insurgents by the Federal Government of Nigeria.

Meanwhile, protesters against the DAPL in the US assert that the pipeline would damage sacred land and pollute the water supply to the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and other downstream communities, just like how many years of oil exploration has rendered the entire Niger Delta region disastrous. For the Black Lives Matter movement and its allies, it is not just about police brutality but also about systemic racism in education, housing, clean water, and a livable environment devoid of pollution���a right to restored land, clean air, clean water and housing and an end to the exploitative privatization of natural resources. For the BLM, the Sioux Tribe, and the Niger Delta communities, land and water are central not only for physical survival, but also for cultural survival. Any arrangement that denies them access to these important resources can lead to loss of livelihood, destruction of sacred sites, and disruption of cultural practices that are vital to community identity.

Denial of access to sacred sites, water (in Detroit and Flint), clean air, and areas of cultural importance is a grave violence whose impact on communities cannot be overemphasized. For example, some of the sacred places threatened by the DAPL are cemeteries where the ancestors of the Sioux tribe are buried. Clearing these cemeteries to make way for oil pipelines will completely erase the connection that the community has to its history.

In my many years of work in the Niger Delta region, I have witnessed firsthand the devastating effects that oil exploration has had on entire communities. I will never forget my work in Ogoniland, a region of the Niger Delta home to the indigenous Ogoni people. In 2011, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) released a report detailing the level of environmental pollution in the area, and estimated that environmental cleanup and restoration could take 30 years and over $30 billion. When I saw the protests in North Dakota and the reaction of the Obama administration to suspend DAPL construction in December 2016, I became hopeful that the Standing Rock Sioux would avoid the horrific environmental conditions that have plagued the Ogonis and other Niger Delta communities for many years.

However, my hope has since turned to anxiety after the Trump administration rapidly began cutting back on environmental regulations. For example, on January 31, 2017, the Army Corps of Engineers announced that it would be granting an easement to allow construction of the DAPL to continue. This followed an executive order issued by Trump calling for construction to recommence.

The Sioux Tribe community was granted a temporary reprieve on March 25, 2020 when a Federal Judge ordered a full environmental review of the pipeline construction. However, the coming months will no doubt prove difficult for the tireless protesters of Standing Rock. Since their first temporary victory in December 2016, many of the protesters have left North Dakota, packing up their tents and returning to their daily lives. Only a few hundred steadfast ���Water Warriors��� remain in spite of the Trump administration���s intimidation. With the vast expansion of drilling in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic oceans, many communities across the US���from Florida to Alaska���may soon find out that they have many things in common with the Ugbo, Egbema, Bonny island, Oloibiri, and other communities of the Niger Delta���chief among them, a degraded environment.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers