Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 164

July 20, 2020

The mark of the former colonizer

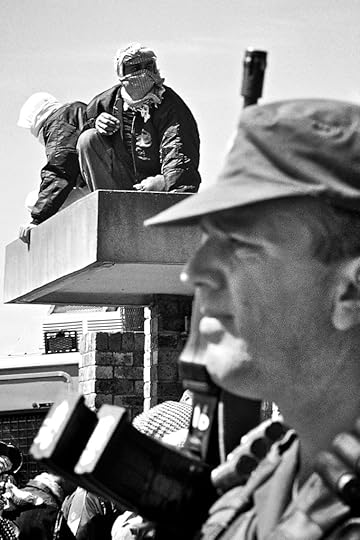

Faidherbe���s statue in Saint-Louis in September 2017, via the Senegalese collective against the celebration of Faidherbe.

Since the assassination of George Floyd, statues celebrating slave-traders, colonialists and segregationists have been toppled all over the world. The Faidherbe Must Fall campaign has been calling for the removal of French colonial general Louis Faidherbe���s statues in Senegal and France. In this interview, Khadim Ndiaye (researcher in history and member of the Senegalese collective against the celebration of Faidherbe) and Salian Sylla, PhD, (an activist at Survie and the Faidherbe Must Fall collective) argue for the emancipation of public spaces from the glorification of a hideous past.

Florian Bobin

Khadim Ndiaye, in your recent article, ���The disturbing presence of the statue of Faidherbe in Saint-Louis,��� you write: ���Faidherbe laid the ideological foundations for the French occupation of Senegal and West Africa. He was the great actor in this colonial enterprise that ushered in an era of oppression and subjugation.��� What was Louis Faidherbe���s role in the French colonization of Africa?

Khadim Ndiaye

Faidherbe was a French colonial soldier sent to Guadeloupe and then to Algeria, where Marshal Thomas Bugeaud committed the worst atrocities, burning entire villages and killing resistance fighters, in defiance of all humanitarian rules. It was in Algeria that Faidherbe was introduced to violent repressive methods. He arrived in Senegal, where he was appointed battalion commander and then governor of the colony at the end of 1854. One of Faidherbe���s first actions was to put erudition at the service of colonial conquest. Knowledge of the men and the country was necessary to succeed in his mission. Faidherbe is also considered to be the ���true founder of the French Africanist school.��� History, ethnology, anthropology, linguistics, and topography were the instruments at the service of hegemony. This mass of knowledge also conveyed the worst racist ideas maintained at the time by the so-called scholars of the Paris School of Anthropology, of which Faidherbe was a correspondent. This is what President Senghor did not understand when he said that Faidherbe was a friend of the Senegalese, because he had got to know them and made himself Senegalese with the Senegalese. Of course, Faidherbe did not want to get to know them just to know them; he wanted to understand their living environment, habits, and customs to better subjugate the people.

Faidherbe organized the military conquest of the territory and established the principle of cultural assimilation. It was he who created the famous Hostage School in Saint-Louis where the sons of village chiefs and notables, brought back from tours in the interior of the country, were forcibly enrolled and ���civilized��� to the core. He created the corps of ���Senegalese tirailleurs��� in 1857, motivated mainly by racist ideas. Blacks make good soldiers, he said in 1859, ���because they don���t appreciate danger and have very poorly developed nervous systems.��� Faidherbe advocated union with indigenous women. Such a union, made without priests and with its share of illegitimate children, also served the colonial cause by re-motivating the soldiers who had come from the metropole and were threatened by loneliness and depression. Faidherbe made young Diokounda Sidib��, a 15-year-old girl, his ���country wife.��� Pinet-Laprade, his right-hand man, took Marie Peulh, whom he presented in France as his maid.

For Faidherbe and his collaborators, any action must serve the colonial cause. Nothing was done to please the people. And it was by the force of bayonets and gunboats that ���pacification��� was carried out by Faidherbe and his successors. Thousands of people were killed, and dozens of villages burned down. Faidherbe himself took part in several military expeditions. This ���pacification��� is a ���tranquility��� and a ���peace��� obtained at the price of a ferocious military conquest. It was the condition for the establishment of the trading economy, forced labor, colonial education, cultural assimilation, and the placing of the colony in dependence.

Florian Bobin

Until the end of the 1970s, a statue of Faidherbe still stood in Dakar���s presidential palace. His statue in Saint-Louis stands on a square that still bears his name, where French President Emmanuel Macron chose to deliver his speech during his official visit to Senegal in 2018. Already in 1978, director Sembene Ousmane wrote to President Senghor:

Is it not a provocation, an offence, an attack on the moral dignity of our national history to sing the Lat Joor anthem under the pedestal of Faidherbe���s statue? Why, since we have been independent for years in Saint-Louis, Kaolack, Thi��s, Ziguinchor, Rufisque, Dakar, etc., do our streets, our arteries, our boulevards, our avenues, our squares still bear the names of old and new colonialists?

After heavy rains in September 2017, Faidherbe���s statue in Saint-Louis fell, but the authorities sharply put it back up. What explains, to this day, this deep attachment to Faidherbe���s figure in Senegal?

Khadim Ndiaye

There is an attachment to Faidherbe because he was presented by colonial propaganda as a savior. For example, in Jaunet and Barry���s 1949 history textbook for schoolchildren in French West-Africa, Faidherbe is portrayed as an honest and upright man who loved to protect the weak, the poor, and who punished the oppressors. There are also, among the Senegalese authorities, some who presented him as a ���friend.��� For example, Senghor used to say: ���If I speak of Faidherbe, it is with the highest esteem, even friendship, because he got to know us.��� In an interview in 1981 with French diplomat Pierre Boisdeffre, who was passing through Senegal, Senghor insisted on the conqueror���s sympathy: ���Faidherbe became a Negro with the Negroes, as Father Liberman would later recommend. He thus became Senegalese with the Senegalese by studying the languages and civilizations of Senegal.���

The statue of Faidherbe, the bridge of Ndar and the streets that bear his name, reflect a certain ���Faidherbe myth��� that has long existed in Senegal. Some even place him in their filiation. One speaks of ���Maam Faidherbe��� (the Faidherbe ancestor). They have made him a kind of tutelary genius that must be commended at every entrance or exit of the city of Saint-Louis. But this myth is now shattered. Thanks to excellent awareness-raising work on social media, young people are aware of the negative impact of his actions. And they can���t believe it when they discover that the native of Lille has hands stained with the blood of their ancestors.

Florian Bobin

In the aforementioned letter, Sembene Ousmane goes on to ask: ���Has our country not given women and men who deserve the honor of occupying the pediments of our high schools, colleges, theatres, universities, streets and avenues, etc.?��� In fact, the Faidherbe High School of Saint-Louis was renamed Cheikh Omar Foutiyou Tall High School in 1984. You explain that ���Faidherbe���s statue in Saint-Louis means, for all of Senegal���s students, the torturer honored and glorified. Toppling such a statue is, therefore, to free oneself from the coloniality of the being and space.��� Many cities in Senegal, and more broadly in Africa, still bear the marks of glorification of the former colonizer. These street names, schools, avenues, or statues generally bear no clear inscription of the role of such characters in the history of the country. To ���free ourselves from the coloniality of the being and space,��� who should be celebrated in the public space in Senegal, in place of figures like Faidherbe?

Khadim Ndiaye

Sembene Ousmane is right, in my opinion. I think it���s important to celebrate the memory of the resistance. That was Algeria���s option after independence. The people of that country were terrified of someone whom Faidherbe considered to be his master. This is the opinion of the historian Roger Pasquier, who studied Faidherbe���s Algerian influence on the conquest of Senegal. Bugeaud killed thousands of Algerians and burned many villages. He is the initiator of the burning of Algerian resistance fighters. His statue, like that of Faidherbe in Senegal, was erected in Algiers by the colonizers to immortalize the memory of the conquest. After independence, the Algerians removed the statue and, instead, installed a statue of Emir Abdel Kader with the sword raised as a sign of resistance. The Algerians give their point of view on history with this demonstration, which serves to inculcate the memory of the resistance.

In Senegal, we cannot continue to give the point of view of the oppressors. Moreover, the Gor��e City Council, in response to citizen demand, understood what was at stake when deciding to rename the ���Europe Square��� as the ���Liberty and Human Dignity Square.��� It is important to respect the memory of the oppressed.

The colonizers did not erect the statue of Faidherbe in 1887 by chance. It was when the power of the gunboats defeated all the resistance fighters that Faidherbe���s statue was erected in the middle of Saint-Louis as a sign of rejoicing. Lat Dior was assassinated in 1886, and the statue was inaugurated on March 20, 1887, to celebrate the victory over the resistance fighters; to show the greatness of the metropole. This colonial statue is therefore a symbol. It is an attribute of domination. It is the consecration of a murderous ideology based on supremacy. For someone whose ancestors lived through the misdeeds of military conquest and the torments of the Code of the Indigenate, it is good to honor historical figures who reinvigorate lost pride and esteem. It is important to make decisive choices that give meaning to the present and the future when the time comes to celebrate historical figures in a former colony.

Florian Bobin

Khadim Ndiaye, thank you very much. At the call of the Faidherbe Must Fall collective, 200 people mobilized on June 20 in front of the Faidherbe monument in Lille to demand its removal. Salian Sylla, what does the figure of Louis Faidherbe represent to you?

Salian Sylla

At the time, in 2018, when this campaign was launched, it was to draw attention to the fact that Faidherbe occupied a special place in the public space in Lille. The city of Lille, which is twinned with the city of Saint-Louis, is a city where the figure of Faidherbe can be found in many aspects. There is a high school that bears his name, a very large avenue that goes to the very heart of the city, the Gunnery Museum where you have a number of figures, usually military men, who are on display and where Faidherbe occupies a central place. In Lille, you also have a site that is quite central, Republic Square, which is not an ordinary place in the collective memory in France. In front of this square, is a huge equestrian statue of Faidherbe. You can���t come to Lille without being confronted with this character.

At the time, there were many French personalities who distinguished themselves for their support to French colonialism. Jules Ferry, who marked the history of France having established compulsory schooling, notably declared that ���colonization was a daughter of the industrial revolution��� and that ���the superior races had the duty to civilize the inferior races.��� It was indeed a commercial project put forward to annex other territories and convert them to their way of life and economic system. It represents a whole aggregation of illustrated, documented, written thoughts throughout the years, which was very decisive in the perception that the French had of Africans at the time. There was also Joseph Gallieni, who distinguished himself in the massacres in Madagascar; and Hubert Lyautey, who was also Gallieni���s discipline.

Thomas Bugeaud, the invader of Algeria, declared that ���the aim is not to run after the Arabs, which is useless; it is to prevent the Arabs from sowing, harvesting, grazing, enjoying their fields. Go every year and burn their crops, or exterminate every last one of them.��� Detached in Algeria under his leadership at the beginning of his career in 1844, Faidherbe was a great admirer of Bugeaud. Having fought in Algeria, Faidherbe came to Senegal in the 1850s and did much of the same. ���You see a war of extermination, and unfortunately, it is impossible to do otherwise,��� he said when he was in Algeria, ���we are reduced to saying: one Arab killed is two fewer Frenchmen killed.��� So, there is a historical continuity in the work of these generals, which later earned them the tributes and honors of France, in defiance of all the massacres they committed in Africa.

Why the Faidherbe Must Fall campaign? There are several events that have taken place over the years. In 2015, in cities like Pretoria and Johannesburg, people continued to celebrate figures like Cecil Rhodes, the father of British colonization in South Africa, and the Rhodes Must Fall campaign decided to put an end to that and make his statues disappear in the country. Leopold II, also considered a great character, who did many things in terms of infrastructure in Belgium, has his dark, gloomy side; he was a bloodthirsty king. The massacres in Congo constitute one of the greatest genocides in Africa: we are talking about ten million people who lost their lives. It was in 2017 that statues of Leopold II were dismantled and toppled in Belgium. Also, in 2017, we have Charlottesville, USA, where there was a demonstration by right-wing extremists who refused to allow the statue of General Robert Lee, who led the Confederate troops during the Civil War, to be toppled by the town council. There was a counter-demonstration led by antifascists, which resulted in the tragic death of a lady, crushed by a far-right extremist who [drove a car] into the crowd.

It was during this period in 2018���there is a historical continuity���that the municipality of Berlin decided to rename a series of streets that bore the names of several personalities who distinguished themselves during German colonization in Africa. Namibia, in particular, resisted German colonization between 1904 and 1908, which led to what has been named ���the first genocide of the 20th century,��� i.e. the extermination of the Hereros. This Berlin municipality decided to give these streets the names of African resistance fighters, such as Rudolf Manga Bell and Anna Mungunda. It was the first time that, symbolically, a city decided to rename not to give the names of those who massacred African populations, but of those who resisted.

We get to 2020, with the assassination of George Floyd in the United States, which sparked chain reactions all over the world. This is what has revived Faidherbe Must Fall. Today, what we are told when we talk about Faidherbe is that: ���He is someone who defended Lille when the Prussians invaded us in 1870. While the whole of France was on its knees, he managed to stand up to them.��� That may be true. Except that Faidherbe���s resistance during this period lasted only three months, whereas what I���m telling you about him is a whole career during which he massacred without remorse, killed, exterminated, pillaged, and imposed an economic system through peanut cultivation, central to the colonizing project. In Africa, the specialization of the colonies (Senegal with groundnuts, what would become Ivory Coast with cocoa) and the gradual disappearance of food crops still pose a problem today because we have an economic system based on a model that was oriented towards the metropole. We still have the consequences of this phenomenon, i.e. an extraverted economy geared towards outside needs rather than self-sufficiency to meet local demand.

Florian Bobin

On several occasions already, the Faidherbe Must Fall collective has questioned the authorities about the Faidherbe statue in Lille. For the bicentenary of his birth, the city council decided to restore the monument erected in his memory. In an open letter to Mayor Martine Aubry in 2018, you called for ���the removal of the statue of Louis Faidherbe and all symbols glorifying colonialism from public spaces in Lille.��� Elsewhere in France, avenues, streets, and subway stations still celebrate him. In your opinion, what explains this reluctance to discuss the permanence of symbols honoring slave traders and colonialists in the public space, both in Lille and in the rest of France?

Salian Sylla

We had, at the time, written an open letter to Martine Aubry. We had asked for a reflection on the presence in Lille of figures who represent a racist and xenophobic vision of the world. Unfortunately, we did not find any interlocutor. That goes to show the ambiguity that part of the left in France has with regard to colonialism. And it���s a shame because if we are still, in 2020, talking about this subject, it���s because in 2018 we weren���t heard. We are still in a situation where the left, which has always been, at least in its principles, on the side of the dominated, has not lived up to its historical role.

It is difficult to establish a dialogue in France in 2020 on certain issues because, as soon as we start talking about colonization, we will immediately come to be the ���people who are enemies of France.��� We are perceived that way. When we were in the street demonstrating to demand that the local authorities remove the equestrian statue of Faidherbe, who was there against us? Right-wing demonstrators, protected by the police. That���s what the debate in France is all about; when you talk about certain subjects, they caricature you and throw stones at you.

Many people have been fighting for a while, particularly against police violence, against unequal policies, for social justice, and all these people have become, overnight, ���identitarians.��� They are the ones who have become the racists in the end! That���s the irony in France. As long as you���re talking about George Floyd, Michael Brown, police violence taking place in the United States; of course, everyone agrees in France; of course, this phenomenon exists in the United States; of course, the American system is deeply, systemically racist! But as soon as we start saying: ���Well, now, let���s sit down and look at things in France, what���s happening today,��� when we talk about Adama Traor��, and we start listing, we are told: ���Ah no no no, the French police is not racist!���

It is a matter of questioning a system that allows people to die. The colonial issue has not been settled. People have been taught to construct a whole imaginary, a whole bunch of representations about the descendants of those from the former colonies in Africa. As long as historical issues are not settled, as long as they are denied, as long as we keep avoiding them, it���s not going to solve the problem. You can���t bring the temperature down just by breaking the thermometer. That is the dynamic we are in today. As soon as questions are raised, people try to caricature, to discredit by using certain words: separatism, communitarianism, anti-white racism.

This Republic has always toppled, named, unnamed, baptized, debaptized; it has always been done. The proof is that one of Lille���s main arteries was called, a few years ago, Paris Road and now Pierre Mauroy Road, the city���s former socialist mayor. To say that we can���t get rid of Faidherbe���s statue is a lie. Because, until 1976, we had the statue of Napoleon III in the heart of the city; this statue was removed and is now in the Museum of Fine Arts. In 1945, the statue of General Oscar de N��grier, another colonizer, was taken down and mysteriously disappeared from the public space. And these are not the only examples.

Florian Bobin

On June 22, the Faidherbe Must Fall collective sent an open letter to the candidates of the Lille municipal election held on June 28. Recalling that ���the debate on the celebration of figures related to slavery, colonialism or segregationism has resurfaced in many countries,��� you write, ���for many demonstrators, including us, the racism (and particularly negrophobia) that runs through Western nations has its origins in the criminal history of the slave trade and colonial domination.��� According to you, who should be celebrated in the public space in France, in place of figures like Faidherbe?

Salian Sylla

This year, I learned from my daughter, who is in middle school, that the city of Lille is organizing a civic week, which consists of sending children to visit some historical sites that are part of its heritage to help them discover its history and ���heroes.��� And these ���heroes��� are, very often, soldiers. You have a guide who explains that Faidherbe was a great man, who built Senegal, built roads, built hospitals, dug a deep-water port, modernized Senegal and that all Senegalese children are grateful to him today. She reacted by telling one of her friends that she thought it was false. You can imagine; a 9-year-old girl questioning the words of an adult supposed to be a fine connoisseur of Faidherbe���s history. It was all the more shocking because I had been in the Faidherbe Must Fall campaign in 2018, and at the end of 2019, it came back to me through my daughter to send me the image of Faidherbe as a benefactor to Senegal. It was unbearable for me.

So, we programmed a visit to this Gunnery Museum. Even with the presence of a Black man, this guide reiterated the same words, saying that Faidherbe was a heroic figure, that he had built Senegal through roads and hospitals. We gave him our position, even if we found it difficult to get him to agree to hear us out. He���s in this same narrative; for years, he���s been doing just that, nobody has ever questioned his version of history.

That���s what we���re still presenting in France in 2020 to children who will certainly never, like my daughter, have the opportunity to have someone else say ���no, it���s not true,��� to have someone who is involved in a campaign to make such a sinister figure disappear from the public space, to have another perception of a part of France���s history in relation to its former colonies. Can you imagine the number of children who have gone through this, who have listened, who have drunk in the words of this gentleman, who have considered that Faidherbe was someone who really did good for the history of Lille, and left the museum enraptured by the fact that they heard he was a hero?

That���s why, measures like ���we���re going to sort it out, put up an explanatory plaque��� are minor for me. It is better to take our responsibility to entrust a problematic statue to museums that can take care of it, and, with historians, anchor it in a broader history to allow museum visitors to better understand its ins and outs. It is better to place it in a context where people will be able to analyze it and put it into context. As long as I see this equestrian statue representing women underneath, which Faidherbe seems to be despising with his eyes, celebrating the power of a heroized man, Martine Aubry will be able to say whatever she wants. Still, for me, she will always be at odds with the principles she claims to defend. And unfortunately, her environmentalist opponents aren���t doing any better.

A city that decides to give someone���s name to a street, an avenue, a statue is simply a political act. And only a political act can deal with it. This is what we have been working on for the past few years through this unprecedented mobilization to ensure that the darkest part of Faidherbe���s legacy, which remains unknown, is accessible to everyone.

The marks of the former colonizer

Faidherbe���s statue in Saint-Louis in September 2017, via the Senegalese collective against the celebration of Faidherbe.

Since the assassination of George Floyd, statues celebrating slave-traders, colonialists and segregationists have been toppled all over the world. The Faidherbe Must Fall campaign has been calling for the removal of French colonial general Louis Faidherbe���s statues in Senegal and France. In this interview, Khadim Ndiaye (researcher in history and member of the Senegalese collective against the celebration of Faidherbe) and Salian Sylla, PhD, (an activist at Survie and the Faidherbe Must Fall collective) argue for the emancipation of public spaces from the glorification of a hideous past.

Florian Bobin

Khadim Ndiaye, in your recent article, ���The disturbing presence of the statue of Faidherbe in Saint-Louis,��� you write: ���Faidherbe laid the ideological foundations for the French occupation of Senegal and West Africa. He was the great actor in this colonial enterprise that ushered in an era of oppression and subjugation.��� What was Louis Faidherbe���s role in the French colonization of Africa?

Khadim Ndiaye

Faidherbe was a French colonial soldier sent to Guadeloupe and then to Algeria, where Marshal Thomas Bugeaud committed the worst atrocities, burning entire villages and killing resistance fighters, in defiance of all humanitarian rules. It was in Algeria that Faidherbe was introduced to violent repressive methods. He arrived in Senegal, where he was appointed battalion commander and then governor of the colony at the end of 1854. One of Faidherbe���s first actions was to put erudition at the service of colonial conquest. Knowledge of the men and the country was necessary to succeed in his mission. Faidherbe is also considered to be the ���true founder of the French Africanist school.��� History, ethnology, anthropology, linguistics, and topography were the instruments at the service of hegemony. This mass of knowledge also conveyed the worst racist ideas maintained at the time by the so-called scholars of the Paris School of Anthropology, of which Faidherbe was a correspondent. This is what President Senghor did not understand when he said that Faidherbe was a friend of the Senegalese, because he had got to know them and made himself Senegalese with the Senegalese. Of course, Faidherbe did not want to get to know them just to know them; he wanted to understand their living environment, habits, and customs to better subjugate the people.

Faidherbe organized the military conquest of the territory and established the principle of cultural assimilation. It was he who created the famous Hostage School in Saint-Louis where the sons of village chiefs and notables, brought back from tours in the interior of the country, were forcibly enrolled and ���civilized��� to the core. He created the corps of ���Senegalese tirailleurs��� in 1857, motivated mainly by racist ideas. Blacks make good soldiers, he said in 1859, ���because they don���t appreciate danger and have very poorly developed nervous systems.��� Faidherbe advocated union with indigenous women. Such a union, made without priests and with its share of illegitimate children, also served the colonial cause by re-motivating the soldiers who had come from the metropole and were threatened by loneliness and depression. Faidherbe made young Diokounda Sidib��, a 15-year-old girl, his ���country wife.��� Pinet-Laprade, his right-hand man, took Marie Peulh, whom he presented in France as his maid.

For Faidherbe and his collaborators, any action must serve the colonial cause. Nothing was done to please the people. And it was by the force of bayonets and gunboats that ���pacification��� was carried out by Faidherbe and his successors. Thousands of people were killed, and dozens of villages burned down. Faidherbe himself took part in several military expeditions. This ���pacification��� is a ���tranquility��� and a ���peace��� obtained at the price of a ferocious military conquest. It was the condition for the establishment of the trading economy, forced labor, colonial education, cultural assimilation, and the placing of the colony in dependence.

Florian Bobin

Until the end of the 1970s, a statue of Faidherbe still stood in Dakar���s presidential palace. His statue in Saint-Louis stands on a square that still bears his name, where French President Emmanuel Macron chose to deliver his speech during his official visit to Senegal in 2018. Already in 1978, director Sembene Ousmane wrote to President Senghor:

Is it not a provocation, an offence, an attack on the moral dignity of our national history to sing the Lat Joor anthem under the pedestal of Faidherbe���s statue? Why, since we have been independent for years in Saint-Louis, Kaolack, Thi��s, Ziguinchor, Rufisque, Dakar, etc., do our streets, our arteries, our boulevards, our avenues, our squares still bear the names of old and new colonialists?

After heavy rains in September 2017, Faidherbe���s statue in Saint-Louis fell, but the authorities sharply put it back up. What explains, to this day, this deep attachment to Faidherbe���s figure in Senegal?

Khadim Ndiaye

There is an attachment to Faidherbe because he was presented by colonial propaganda as a savior. For example, in Jaunet and Barry���s 1949 history textbook for schoolchildren in French West-Africa, Faidherbe is portrayed as an honest and upright man who loved to protect the weak, the poor, and who punished the oppressors. There are also, among the Senegalese authorities, some who presented him as a ���friend.��� For example, Senghor used to say: ���If I speak of Faidherbe, it is with the highest esteem, even friendship, because he got to know us.��� In an interview in 1981 with French diplomat Pierre Boisdeffre, who was passing through Senegal, Senghor insisted on the conqueror���s sympathy: ���Faidherbe became a Negro with the Negroes, as Father Liberman would later recommend. He thus became Senegalese with the Senegalese by studying the languages and civilizations of Senegal.���

The statue of Faidherbe, the bridge of Ndar and the streets that bear his name, reflect a certain ���Faidherbe myth��� that has long existed in Senegal. Some even place him in their filiation. One speaks of ���Maam Faidherbe��� (the Faidherbe ancestor). They have made him a kind of tutelary genius that must be commended at every entrance or exit of the city of Saint-Louis. But this myth is now shattered. Thanks to excellent awareness-raising work on social media, young people are aware of the negative impact of his actions. And they can���t believe it when they discover that the native of Lille has hands stained with the blood of their ancestors.

Florian Bobin

In the aforementioned letter, Sembene Ousmane goes on to ask: ���Has our country not given women and men who deserve the honor of occupying the pediments of our high schools, colleges, theatres, universities, streets and avenues, etc.?��� In fact, the Faidherbe High School of Saint-Louis was renamed Cheikh Omar Foutiyou Tall High School in 1984. You explain that ���Faidherbe���s statue in Saint-Louis means, for all of Senegal���s students, the torturer honored and glorified. Toppling such a statue is, therefore, to free oneself from the coloniality of the being and space.��� Many cities in Senegal, and more broadly in Africa, still bear the marks of glorification of the former colonizer. These street names, schools, avenues, or statues generally bear no clear inscription of the role of such characters in the history of the country. To ���free ourselves from the coloniality of the being and space,��� who should be celebrated in the public space in Senegal, in place of figures like Faidherbe?

Khadim Ndiaye

Sembene Ousmane is right, in my opinion. I think it���s important to celebrate the memory of the resistance. That was Algeria���s option after independence. The people of that country were terrified of someone whom Faidherbe considered to be his master. This is the opinion of the historian Roger Pasquier, who studied Faidherbe���s Algerian influence on the conquest of Senegal. Bugeaud killed thousands of Algerians and burned many villages. He is the initiator of the burning of Algerian resistance fighters. His statue, like that of Faidherbe in Senegal, was erected in Algiers by the colonizers to immortalize the memory of the conquest. After independence, the Algerians removed the statue and, instead, installed a statue of Emir Abdel Kader with the sword raised as a sign of resistance. The Algerians give their point of view on history with this demonstration, which serves to inculcate the memory of the resistance.

In Senegal, we cannot continue to give the point of view of the oppressors. Moreover, the Gor��e City Council, in response to citizen demand, understood what was at stake when deciding to rename the ���Europe Square��� as the ���Liberty and Human Dignity Square.��� It is important to respect the memory of the oppressed.

The colonizers did not erect the statue of Faidherbe in 1887 by chance. It was when the power of the gunboats defeated all the resistance fighters that Faidherbe���s statue was erected in the middle of Saint-Louis as a sign of rejoicing. Lat Dior was assassinated in 1886, and the statue was inaugurated on March 20, 1887, to celebrate the victory over the resistance fighters; to show the greatness of the metropole. This colonial statue is therefore a symbol. It is an attribute of domination. It is the consecration of a murderous ideology based on supremacy. For someone whose ancestors lived through the misdeeds of military conquest and the torments of the Code of the Indigenate, it is good to honor historical figures who reinvigorate lost pride and esteem. It is important to make decisive choices that give meaning to the present and the future when the time comes to celebrate historical figures in a former colony.

Florian Bobin

Khadim Ndiaye, thank you very much. At the call of the Faidherbe Must Fall collective, 200 people mobilized on June 20 in front of the Faidherbe monument in Lille to demand its removal. Salian Sylla, what does the figure of Louis Faidherbe represent to you?

Salian Sylla

At the time, in 2018, when this campaign was launched, it was to draw attention to the fact that Faidherbe occupied a special place in the public space in Lille. The city of Lille, which is twinned with the city of Saint-Louis, is a city where the figure of Faidherbe can be found in many aspects. There is a high school that bears his name, a very large avenue that goes to the very heart of the city, the Gunnery Museum where you have a number of figures, usually military men, who are on display and where Faidherbe occupies a central place. In Lille, you also have a site that is quite central, Republic Square, which is not an ordinary place in the collective memory in France. In front of this square, is a huge equestrian statue of Faidherbe. You can���t come to Lille without being confronted with this character.

At the time, there were many French personalities who distinguished themselves for their support to French colonialism. Jules Ferry, who marked the history of France having established compulsory schooling, notably declared that ���colonization was a daughter of the industrial revolution��� and that ���the superior races had the duty to civilize the inferior races.��� It was indeed a commercial project put forward to annex other territories and convert them to their way of life and economic system. It represents a whole aggregation of illustrated, documented, written thoughts throughout the years, which was very decisive in the perception that the French had of Africans at the time. There was also Joseph Gallieni, who distinguished himself in the massacres in Madagascar; and Hubert Lyautey, who was also Gallieni���s discipline.

Thomas Bugeaud, the invader of Algeria, declared that ���the aim is not to run after the Arabs, which is useless; it is to prevent the Arabs from sowing, harvesting, grazing, enjoying their fields. Go every year and burn their crops, or exterminate every last one of them.��� Detached in Algeria under his leadership at the beginning of his career in 1844, Faidherbe was a great admirer of Bugeaud. Having fought in Algeria, Faidherbe came to Senegal in the 1850s and did much of the same. ���You see a war of extermination, and unfortunately, it is impossible to do otherwise,��� he said when he was in Algeria, ���we are reduced to saying: one Arab killed is two fewer Frenchmen killed.��� So, there is a historical continuity in the work of these generals, which later earned them the tributes and honors of France, in defiance of all the massacres they committed in Africa.

Why the Faidherbe Must Fall campaign? There are several events that have taken place over the years. In 2015, in cities like Pretoria and Johannesburg, people continued to celebrate figures like Cecil Rhodes, the father of British colonization in South Africa, and the Rhodes Must Fall campaign decided to put an end to that and make his statues disappear in the country. Leopold II, also considered a great character, who did many things in terms of infrastructure in Belgium, has his dark, gloomy side; he was a bloodthirsty king. The massacres in Congo constitute one of the greatest genocides in Africa: we are talking about ten million people who lost their lives. It was in 2017 that statues of Leopold II were dismantled and toppled in Belgium. Also, in 2017, we have Charlottesville, USA, where there was a demonstration by right-wing extremists who refused to allow the statue of General Robert Lee, who led the Confederate troops during the Civil War, to be toppled by the town council. There was a counter-demonstration led by antifascists, which resulted in the tragic death of a lady, crushed by a far-right extremist who [drove a car] into the crowd.

It was during this period in 2018���there is a historical continuity���that the municipality of Berlin decided to rename a series of streets that bore the names of several personalities who distinguished themselves during German colonization in Africa. Namibia, in particular, resisted German colonization between 1904 and 1908, which led to what has been named ���the first genocide of the 20th century,��� i.e. the extermination of the Hereros. This Berlin municipality decided to give these streets the names of African resistance fighters, such as Rudolf Manga Bell and Anna Mungunda. It was the first time that, symbolically, a city decided to rename not to give the names of those who massacred African populations, but of those who resisted.

We get to 2020, with the assassination of George Floyd in the United States, which sparked chain reactions all over the world. This is what has revived Faidherbe Must Fall. Today, what we are told when we talk about Faidherbe is that: ���He is someone who defended Lille when the Prussians invaded us in 1870. While the whole of France was on its knees, he managed to stand up to them.��� That may be true. Except that Faidherbe���s resistance during this period lasted only three months, whereas what I���m telling you about him is a whole career during which he massacred without remorse, killed, exterminated, pillaged, and imposed an economic system through peanut cultivation, central to the colonizing project. In Africa, the specialization of the colonies (Senegal with groundnuts, what would become Ivory Coast with cocoa) and the gradual disappearance of food crops still pose a problem today because we have an economic system based on a model that was oriented towards the metropole. We still have the consequences of this phenomenon, i.e. an extraverted economy geared towards outside needs rather than self-sufficiency to meet local demand.

Florian Bobin

On several occasions already, the Faidherbe Must Fall collective has questioned the authorities about the Faidherbe statue in Lille. For the bicentenary of his birth, the city council decided to restore the monument erected in his memory. In an open letter to Mayor Martine Aubry in 2018, you called for ���the removal of the statue of Louis Faidherbe and all symbols glorifying colonialism from public spaces in Lille.��� Elsewhere in France, avenues, streets, and subway stations still celebrate him. In your opinion, what explains this reluctance to discuss the permanence of symbols honoring slave traders and colonialists in the public space, both in Lille and in the rest of France?

Salian Sylla

We had, at the time, written an open letter to Martine Aubry. We had asked for a reflection on the presence in Lille of figures who represent a racist and xenophobic vision of the world. Unfortunately, we did not find any interlocutor. That goes to show the ambiguity that part of the left in France has with regard to colonialism. And it���s a shame because if we are still, in 2020, talking about this subject, it���s because in 2018 we weren���t heard. We are still in a situation where the left, which has always been, at least in its principles, on the side of the dominated, has not lived up to its historical role.

It is difficult to establish a dialogue in France in 2020 on certain issues because, as soon as we start talking about colonization, we will immediately come to be the ���people who are enemies of France.��� We are perceived that way. When we were in the street demonstrating to demand that the local authorities remove the equestrian statue of Faidherbe, who was there against us? Right-wing demonstrators, protected by the police. That���s what the debate in France is all about; when you talk about certain subjects, they caricature you and throw stones at you.

Many people have been fighting for a while, particularly against police violence, against unequal policies, for social justice, and all these people have become, overnight, ���identitarians.��� They are the ones who have become the racists in the end! That���s the irony in France. As long as you���re talking about George Floyd, Michael Brown, police violence taking place in the United States; of course, everyone agrees in France; of course, this phenomenon exists in the United States; of course, the American system is deeply, systemically racist! But as soon as we start saying: ���Well, now, let���s sit down and look at things in France, what���s happening today,��� when we talk about Adama Traor��, and we start listing, we are told: ���Ah no no no, the French police is not racist!���

It is a matter of questioning a system that allows people to die. The colonial issue has not been settled. People have been taught to construct a whole imaginary, a whole bunch of representations about the descendants of those from the former colonies in Africa. As long as historical issues are not settled, as long as they are denied, as long as we keep avoiding them, it���s not going to solve the problem. You can���t bring the temperature down just by breaking the thermometer. That is the dynamic we are in today. As soon as questions are raised, people try to caricature, to discredit by using certain words: separatism, communitarianism, anti-white racism.

This Republic has always toppled, named, unnamed, baptized, debaptized; it has always been done. The proof is that one of Lille���s main arteries was called, a few years ago, Paris Road and now Pierre Mauroy Road, the city���s former socialist mayor. To say that we can���t get rid of Faidherbe���s statue is a lie. Because, until 1976, we had the statue of Napoleon III in the heart of the city; this statue was removed and is now in the Museum of Fine Arts. In 1945, the statue of General Oscar de N��grier, another colonizer, was taken down and mysteriously disappeared from the public space. And these are not the only examples.

Florian Bobin

On June 22, the Faidherbe Must Fall collective sent an open letter to the candidates of the Lille municipal election held on June 28. Recalling that ���the debate on the celebration of figures related to slavery, colonialism or segregationism has resurfaced in many countries,��� you write, ���for many demonstrators, including us, the racism (and particularly negrophobia) that runs through Western nations has its origins in the criminal history of the slave trade and colonial domination.��� According to you, who should be celebrated in the public space in France, in place of figures like Faidherbe?

Salian Sylla

This year, I learned from my daughter, who is in middle school, that the city of Lille is organizing a civic week, which consists of sending children to visit some historical sites that are part of its heritage to help them discover its history and ���heroes.��� And these ���heroes��� are, very often, soldiers. You have a guide who explains that Faidherbe was a great man, who built Senegal, built roads, built hospitals, dug a deep-water port, modernized Senegal and that all Senegalese children are grateful to him today. She reacted by telling one of her friends that she thought it was false. You can imagine; a 9-year-old girl questioning the words of an adult supposed to be a fine connoisseur of Faidherbe���s history. It was all the more shocking because I had been in the Faidherbe Must Fall campaign in 2018, and at the end of 2019, it came back to me through my daughter to send me the image of Faidherbe as a benefactor to Senegal. It was unbearable for me.

So, we programmed a visit to this Gunnery Museum. Even with the presence of a Black man, this guide reiterated the same words, saying that Faidherbe was a heroic figure, that he had built Senegal through roads and hospitals. We gave him our position, even if we found it difficult to get him to agree to hear us out. He���s in this same narrative; for years, he���s been doing just that, nobody has ever questioned his version of history.

That���s what we���re still presenting in France in 2020 to children who will certainly never, like my daughter, have the opportunity to have someone else say ���no, it���s not true,��� to have someone who is involved in a campaign to make such a sinister figure disappear from the public space, to have another perception of a part of France���s history in relation to its former colonies. Can you imagine the number of children who have gone through this, who have listened, who have drunk in the words of this gentleman, who have considered that Faidherbe was someone who really did good for the history of Lille, and left the museum enraptured by the fact that they heard he was a hero?

That���s why, measures like ���we���re going to sort it out, put up an explanatory plaque��� are minor for me. It is better to take our responsibility to entrust a problematic statue to museums that can take care of it, and, with historians, anchor it in a broader history to allow museum visitors to better understand its ins and outs. It is better to place it in a context where people will be able to analyze it and put it into context. As long as I see this equestrian statue representing women underneath, which Faidherbe seems to be despising with his eyes, celebrating the power of a heroized man, Martine Aubry will be able to say whatever she wants. Still, for me, she will always be at odds with the principles she claims to defend. And unfortunately, her environmentalist opponents aren���t doing any better.

A city that decides to give someone���s name to a street, an avenue, a statue is simply a political act. And only a political act can deal with it. This is what we have been working on for the past few years through this unprecedented mobilization to ensure that the darkest part of Faidherbe���s legacy, which remains unknown, is accessible to everyone.

Gangs and activists

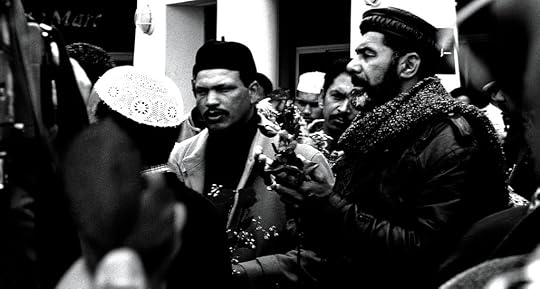

Image credit Suren Pillay.

In February 2020, the anti-crime group, PAGAD or People Against Gangsterism and Drugs, returned to the headlines in South Africa. They had torched the house of an alleged drug dealer in Ocean View, a largely working-class township on the southern edge of Cape Town. PAGAD blamed the occupants of the house for the murder of a seven-year-old boy days earlier. A few months earlier, PAGAD had made the headlines for celebrating the assassination of Rashied Staggie, a former gangster leader. PAGAD���s decision to comment brought up memories of an earlier period, in the mid-to-late 1990s, when PAGAD launched a campaign of terror against gangsters in Cape Town. It culminated in the shooting and burning alive of Rashied���s brother, Rashaad, in August 1996. Political theorist and anthropologist Suren Pillay, researches violence and grew up in Cape Town. He observed the rise of PAGAD up close in the 1990s. In 2002, Herman Wasserman and I asked Suren to write about PAGAD. The result was published in Shifting Selves: Post-Apartheid Essays on Media, Culture and Identity (Cape Town: Kwela Books, 2003) as ���Experts, Terrorists, Gangsters: Problematizing Public Discourse on a Post-Apartheid Showdown.��� Three years later Suren published the essay below in Men of the Global South: A Reader, edited by Adam Jones (Zed Press).

A few years ago, I found myself among some youths who were familiar to me. I did not recognize them at first, because their faces were covered by the checkered scarves that we associate now with the Palestinians. It was in a community called Rylands, one of the two group areas designated by the apartheid state for so-called ���Indians��� in Cape Town. It was also the neighbourhood I grew up in. The last time I had seen youths covering their faces in this manner in the neighbourhood was about ten years earlier. And at that time I happened to be one of them. It was during the school boycotts of 1985. We used the scarves to protect our faces from identification by the police as we set up barricades of burning car-tires in the street, and when we hurled petrol bombs at the ubiquitous canary-yellow police vehicles that surrounded our schools.

This time the youths I met were participating in a march organized by a newly-formed group called PAGAD���People Against Gangsterism and Drugs. It was formed by local community leaders, particularly teachers, who were fed up with the proliferation of gang violence and the drug trade on the Cape Flats. Their unhappiness was framed within a particular religious-moral discourse. They were overwhelmingly Muslim, and it was to Islamic scripture and symbolism that they turned to articulate their desire to, in their words, ���rid the community��� of gangs and drugs. The strategy was to call public meetings, at the end of which a march would proceed to the house of a drug dealer. He or she would be given a 24-hour ultimatum to cease selling drugs, or face the consequences. Most people covered their faces during these marches for fear of retribution from the drug dealers and the gangs they were part of. Some did it, no doubt, because the drug dealers might recognize them as former clients.

Image credit Suren Pillay.

Image credit Suren Pillay.The movement grew rapidly, but largely unnoticed by the mainstream press in Cape Town. That is, until one of these marches, to the house of Cape Town���s most feared and powerful gang leaders, became a spectacle. The Staggie twins, Rashied and Rashaad, were leaders of the Hard Living Kids���the HL���s, as they are known on the Cape Flats. By the mid-nineties, a turf war was unfolding between the Hard Livings and the other big gang on the Cape Flats, the ���Americans.��� As the marchers stood outside the house, one of the twins, Rashaad, arrived in his SUV. He drove into the thick of the crowd, jumped out of the vehicle, and started mocking those assembled. A scuffle broke out, and in the darkness, shots rang out. When the crowd surrounding Rashaad moved back in panic, he remained standing, shocked, with blood oozing from a gunshot wound. Within second, more shots penetrated his body, and he fell into the gutter. A petrol-bomb was flung at this limp body, bursting into flames upon impact. In a surreal moment, Staggie then stood erect and briefly walked, arms flailing, shrouded in flames, before finally collapsing on the tarred road. I can describe this event in detail, because it was recorded and photographed by the press contingent present. The image of the flame-shrouded Rashaad Staggie���s final steps were played over and over on the local news in the following days, and the pictures were similarly ubiquitous. Pagad was no longer just an organization that those of us from the Cape Flats knew about. It was now a national security concern���more so than the issues its members sought to address.

My concern at that time was with the representation of Pagad in academia and the media. Even though this was long before the hysteria post-9/11, all kinds of Orientalist phobias about Pagad were circulating, such as that it was instigated by the Iranians. In the months that followed, I went to Pagad marches, spoke with members, and attended their meetings. That���s when I realized that I knew some of the youths involved. They were part of what was called the G-Force���a group whose identity was closely guarded, because they were armed, and were most likely involved in a spate of pipe-bombings that ensued during this time. I had been to school with some of them; I knew others from around the neighbourhood. A number of key gang leaders were killed in drive-by shootings, all after having been warned by a Pagad march. When I asked some of them why they were resorting to violence, they said they felt that the new South Africa was not protecting them sufficiently, and they had to take the law into their own hands. Of course, the state could now allow its monopoly over the legitimate use of force to be threatened, and Pagad itself was quickly criminalized.

I had grown up in Rylands���a mostly middle-class, so-called ���Indian��� neighbourhood. It is more homogeneous in class than ethnic terms, however; and in racial and religious terms as well. Rylands is bordered by working-class communities, then designated for ���coloured��� people. Silvertown, Bridgetown, Mannenberg, Bonteheuewel, Heideveld: these neighbourhoods were also the product of the Group Areas Act, which dumped people into strictly-racialized neighbourhoods. They were also places where some of the most powerful gangs on the Cape Flats flourished. Our neighbourhoods were not sealed off; people moved among them, and many kids from surrounding areas attended the local schools in Rylands.

Between 1983 and 1984, when I was around twelve, my friends and I were passing through a painful process of male puberty and its attendant horrors. Some of this involved the opposite sex, of course, as well as cars. But we were also deeply fascinated and fearful of those older boys at school who belonged to the gangs. One character in particular, Youssy Eagle, filled us with awe. He was a member of a gang called the Five-Bob Kids, and was a few years older than us. He would challenge anyone to a fight, and was known to carry a knife longer than the palm of your hand in the inner pocket of his school blazer. We had all clamoured to see him beat the daylights out of some poor contender at the back of the school where the fights usually took place.

We found ourselves talking the gangster talk and walking the gangster walk. This meant using the colloquial phrases of gang language, which were unavoidable on the Cape Flats. It also involved wearing American-style clothing���not the hip-hop influences of today, but the zoot-suit look of button-down shirts, pleated slacks, Jack Purcell sneakers, or the really prized Florsheim shoes. And your pants had to hang down really low at the back, indicating that you were a veteran Mandrax smoker���because one of the side-effects of Mandrax was that your butt disappeared. Mandrax at that time was the most widely-used drug on the Cape Flats. You crushed up the tablet and smoked it with marijuana out of a bottleneck. And you had to carry a three-star Okappi, a pocket knife which you could buy at most corner shops, and which, after hours of practice, you could flick open in one single-handed rhythmic maneuver.

Image credit Suren Pillay.

Image credit Suren Pillay.Like myself, most of my friends did not, strictly speaking, come from working-class families. Most of us did not have any traumatic family history. We mostly went to bed with a full stomach, slept on a comfortable bed, and had mothers intensely concerned with our well-being���a teenage boy���s nightmare, of course. Yet there we were, talking like gangsters, hanging out with gangsters, dressing like gangsters. If there was a hero at that time, other than the iconic Bruce Lee or Rambo, it was the local gang leader, whose recognition we craved. We were, in retrospect, wanna-bes. We didn���t aspire to a life of crime; rather, we dabbled in stealing apples from the local shop in order to establish our criminal credentials.

My own future as a gangster���not that, by all indications, it would have been a particularly successful one anyway���was disrupted by the intrusion of student politics in 1985. I grew attracted to a different vision of personhood, and a different vision of society. But it was also a vision that glorified the figure with a gun. This time, it wasn���t the gangster who was idolized, but the AK-47-wielding guerrilla fighter, operating in secret, striking at the state, and landing a blow for justice. This was violence that needed no justification: it was on the right side of history.

I became a member of the student representative council, chairing it for two years during the state of emergency. SRCs were banned under the state of emergency, so it was rough going. Some of the activities we organized were mass rallies, which brought together diverse schools on the Cape Flats. We would often walk to the neighbouring schools, and sometimes students would get robbed by gangsters along the way. I would have to negotiate with the gangsters to return what they had stolen. Perhaps I���m prone to nostalgia, but the gangsters would often return the goods. After all, we wielded greater violence than they did, and our form was condoned by large sections of the community. Some gangsters would tell us they thought we were crazy���they spent all their time evading the police, and we were fighting them in the streets. But they also grudgingly respected us.

There were schoolmates, or rather comrades, who were in charge of organizing this violence. At our school we called them the A-Team���the action team. Their faces were always covered when they went out to stone or petrol-bomb a police or army vehicle. By 1986, the army had been permanently installed in our areas, and there was an abundance of targets and battles to plan. Successfully blocking off a road for a few hours became a huge cause for celebration. For a few hours, it was a liberated zone. Without psychologizing, I do think some were better-disposed than others towards these kinds of activities. And some would probably have joined criminal gangs if they hadn���t been in our political gang. In fact, some gangsters, like the much-feared Johnny Laughing Boy, renounced their gang membership and became some of the bravest of the street-battlers. Skipping the country to become a guerrilla fighter was the ultimate status symbol for many. It was widely aspired to, but few of us summoned the courage to progress from stones, petrol-bombs, and militarist posturing to ���taking to the bush,��� as we called it. At the end of the day, I suspect that many of us found mother���s cooking and the girl we had a crush on more captivating!

Some of my school-friends did graduate from wanna-bes to hardened criminals; some are still in gangs, and some are drug-dealers. One is in jail for rape. The last time I heard, our lead gangster at school, Youssy Eagle, was in jail for murder. But others do more socially-accepted things, like being lawyers. Youssy���s brother is now a member of the ANC.

Image credit Suren Pillay.

Image credit Suren Pillay.The violence of the gangs, and of the young students, had one thing in common. And it was not their common relation to the means of production, as Don Pinnock, for example, has argued in the most well-known text on the Cape Flats gangs. It was the image of heroic grandeur that was most captivating, and that provided something to aspire to. It is that grandeur that provides the ethical sensibility governing the self���s conduct in the everyday existence of the gangster, or the young political soldier who moves from the wanna-bes to the veteran, to���in the words of the criminologist���the ���hardened.��� A profound sense of one���s own conduct is required to be a gangster; it is not a condition of lawlessness. The ���skollie,��� as the gangster is derogatively called on the Cape Flats, is intensely governed by law. But it is not a law whose founding violence is legitimated by invocations of ���the nation,��� or ���the community,��� or of ���national security.��� The skollie is anti-social, if you view him as a member of one form of the social. But to the aunties, mothers, and supporters who lined the streets at recent trials of notorious gang leaders in Cape Town, who have spoken glowingly about the positive roles they play in the community, about how they pay rents, take care of school fees, resolve disputes���this is another account of the social. It is an account that sublimates its own founding violence, and the violence which keeps its own laws in place, to its own sublime objects of desire.

July 19, 2020

Mali: Les dieux sont tomb��s sur la t��te

[image error]

Bamako. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Last weekend, Bamako saw major protests. The death toll remains unclear. Official sources reported 11 killed while protesters mentioned 23 killed and 124 injured. The triggers for the protests were the disputed legislative elections and the severe insecurity in the country. Protesters demand the resignation of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (popularly known as IBK), who is perceived as ineffective in dealing with the country���s major challenges. As the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is mediating the crisis, it is important to remember the origins of the conflict.

IBK, the decay of a myth

All started well. IBK was elected in 2013 with more than 77% of the vote. Elected with record turnout in a country where participation is generally low, IBK quickly became unpopular. A December 2019 opinion poll of residents of Bamako put his favorability rating at just 26.5%. Indeed, the ���Mande Massa��� has been incapable of dealing with the country���s main challenges. Criticisms include being overly beholden to France, ineffective and authoritarian.

During his tenure, the security condition has worsened. IBK’s campaign slogan, ���Mali First,��� quickly turned into ���My Family First��� as the president surrounded himself with family members for a clan management of power, setting up a system of widespread corruption. At the center of the system, his son Karim Keita was elected as a member of the National Assembly and Chairman of the National Defense, Security and Civil Protection Committee (he resigned from the Committee in the wake of the recent protests). The Military Guidance and Programming Act (LOPM) voted to maintain and improve the performance and equipment of the Malian Armed Forces (FAMAs) with an investment of 1.23 trillion francs CFA���1.91 billion euros over the period 2015-2019. These funds were allegedly largely diverted to the benefit of the presidential clan. The IBK era was thus marked by an extractive management of power, as in the darkest times of post-colonial Africa, such as the time of Mobutu and Bokassa.

Despite the LOPM, the reform of the security apparatus did not yield satisfactory results. FAMAS continued to record huge losses and humiliations on the ground in successive and increasingly deadly attacks. In 2019, several attacks were reported against the military camps of Indelimane (50 dead), Boulkessi and Mondoro (38 dead), and Dioura (23 dead). Soldiers killed were most often young men in the prime of their lives, sent on the field without adequate equipment or even complete military training.

Civilians are bearing the brunt

The state was unable to defeat jihadists exacerbating intercommunal violence. In central Mali, the Katiba Macina Jihadist insurgency lead by Amadou Koufa and other armed groups are capturing vast rural areas and expelling state officials. These movements have won large support in local communities by capitalizing on socio-economic and political grievances. The state���s weakness, abuses, and atrocities committed by security forces���combined with endemic poverty and food insecurity now worsened by the impact of COVID-19���are putting pressure on people all over the country. In rural areas, people have enlisted into armed groups creating self-defense militias to protect themselves. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), in total, 580 people were killed in the first half of 2019 in Central Mali. Several villages were attacked in 2019: Ogoussagou 1 (160 dead); Ogoussagou 2 (35 dead); Sobane-Da (35 dead including 22 children under 12 years); Gangafari and Yoro (at least 41 dead); and recently Bankass (30 dead and many missing). The modus operandi of these attacks always seems to be the same: armed groups surprise sleeping villages, burn everything, kill people, and take away livestock.

On the social front, the IBK regime has engaged in a conflict with various trade unions, teachers, doctors, and magistrates resulting in a long paralysis of basic social services in the country: education, health, and the judiciary. As a result, children were deprived of education for many months. Mali’s fragile progress towards sustainable development is now seriously compromised.

Mali has become a Wild West where the majority of the national territory is beyond the control of the state. In the extreme north of the country, Kidal is almost a de facto autonomous enclave. In the central region, AQIM affiliated groups, Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin, and the Islamic State of the Greater Sahara are fighting for control of these areas and trafficking routes, while civil administrators and other central state officials desert because of insecurity, leaving civilians with no protection or basic services.

The presence of international forces, notably the French operation Barkhane (5,000 troops) and the UN Stabilization mission (MINUSMA, around 12,000 armed troops) has attracted international terrorist groups. Their impact on the ground in terms of security gains is insufficient for Malians, who continue to suffer huge losses while Paris regularly claims “tactical gains.” France’s role is ambiguous in the conflict. Many demonstrations regularly call for the departure of French troops. The UN forces, as usual, are totally useless with an inadequate mandate to manage a conflict as is the case in Mali.

What are the options for a de-escalation?

There are three main options to consider.

First, a collective effort of three bodies (M5-RFP) is leading the protests, helmed by imam Mohamed Dicko. They are calling for the president’s resignation. Such an option is not unconstitutional as some international observers claim. Certain provisions of Article 36 of the constitution of Mali provide for the vacancy of power by the President. However, this option entails several issues. It brings together a religious leader, political party leaders, civil society, and a former army general. Imam Dicko has opposed social changes in the past, including reform of the code of persons and families. The rising of political Islam is worrisome and threatens the secularism of the state and the separation between power and religion and gender equality.�� However, it seems that most people are in favor of a political Islam due to widespread dissatisfaction toward political leaders.

Second, the presence of foreign forces makes a military coup unlikely. However, if the protests that have turned into urban guerrilla struggle continue, the already fragile country risks collapse, or the conflict could turn into a civil war. The takeover of parts of the country by armed groups is not excluded as was the case in 2012. If IBK accepts an honorary role, as proposed by the M5-RFP, which is unlikely, there would be a transition led by a prime minister. Elections would be held as scheduled in 2023.

The last option, which seems more likely, is that IBK will cling to power by proposing fa��ade reforms to save time. This would lead to a dangerous escalation and radicalization of dissent.

Mali is a resilient nation. Let us hope Malians long tradition of dialogue and multicultural understanding will prevail in the end.

July 16, 2020

Kenya’s electoral authoritarianism

Image credit Tavia Nyong'o via Flickr CC.

Three decades after Kenyans took to the streets demanding political and constitutional reforms during the first Saba Saba day protest on July 7, 1990 (the leaders were detained and brutalized, but it is credited for ushering in multiparty democracy there), the conditions that prompted this dissent remain. In this article, the former Chief Justice of Kenya, Willy Mutunga, arrested in an earlier crackdown by Moi’s regime and which led to his exile and then return Kenya after Saba Saba, reflects on this and tackles the following question: “Why after three major successful transitions over three decades���multipartyism, a power transition in

2002, and a new constitution in 2020���are we still being frustrated by our politics and economics?

This post is from our partnership between the Kenyan website The Elephant and Africa Is a Country. We will be publishing a post from their site every week, curated by our Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

Three decades ago, driven by a quest to reclaim their sovereignty and recalibrate the power relations between the state and society, the people of this country went to the streets to push for political and constitutional reforms, a major inflection point in the history of our nation. Through a protracted, peaceful struggle by Kenyans in the country and in the diaspora, the country finally transitioned into a multi-party democracy.

The struggle is not over; Kenya���s politics have taken a backward trajectory, moving towards dictatorship in the midst of an intra-elite succession struggle that could descend into violent conflict, chaos, and even civil war.

Kenya is a fake democracy where elections do not matter because the infrastructure of elections has been captured by the elites. There is a danger of normalizing electoral authoritarianism, where the vote neither counts nor gets counted. The judiciary is under constant attack and disparagement by the executive while parliament is contorted into a body increasingly unable to represent Kenyans and provide oversight over the executive���s actions. The security services are unleashed on the poor and the dispossessed as if they are not citizens but enemies to be hunted down and destroyed.

A range of constitutional commissions are in a state of contrived dysfunction while our media business model is failing, accelerated by political interference. Grand corruption���perpetrated by a handful of families and by the elites collectively���has been normalized and the fight against corruption has been politicized. In the creeping descent into dictatorship, civilian public services have been militarized and the 2010 Constitution that was in many ways a culmination of the struggle that started on July 7, 1990 when the late Kenneth Matiba and Charles Rubia called for a meeting at the Kamukunji grounds in Nairobi, is being deliberately undermined.

We have a duty and a responsibility to defend Kenya���s constitution; to resist efforts to undermine devolution in particular; to resist those determined to continue looting an economy already on its knees; to stand up against efforts to brutalize, dehumanize, and rent asunder the essential human dignity of Kenyans as a people.

Three decades is a generation. The generation that voted for the first time in 1992 is a venerated demographic that is 48 years old today. It is the generation of freedom (the South African equivalent of the ���born-frees���), and a significant part of the cohort that participated in the struggle as teens or young adults. It is the generation that bore the brunt of the struggle for freedom but which has been denied the opportunity for real political leadership. That part of its membership that has had access to state power is drawn from the reactionary wing of the group���the scions of the decadent YK���92 and drivers of the ���NO��� campaign against a new constitution.

Despite having successfully fought for a new constitution, three decades after Saba Saba, the frustration felt by this generation and its children runs deep. Why? Power is still largely imperial, exercised in a brutal and unaccountable manner, as institutions flail and falter. The country is still ethnically divided, the fabric of our nationhood is fraying and its stability remains remarkably and frighteningly fragile. Foreign domination, exploitation, and oppression is still with us. Poverty and inequality still reign as a tiny economic aristocracy consolidates wealth at the top, while a large pool of the poor underclass expands at the bottom. Why is this the case? Why, after three major successful transitions over three decades���multipartyism in 1992; power transition in 2002; and a new constitution in 2010���are we still being frustrated by our politics and economics? Why is our quest to advance Kenya as a prosperous, democratic and stable country floundering? I see five main reasons why Kenya���s democratization and development have been stymied.

First, and most importantly, is the moral bankruptcy of Kenya���s elite. It is the loyal facilitator of our continued colonization by the imperialism of the West and the East. We have a political elite who���together with their acolytes in the middle classes���view this constitution as inconvenient and who have in the last decade taken every step to undermine it, now even audaciously threatening to overhaul it. This mythmaking of how the constitution ���doesn���t work for us���; or how it is ���expensive��� (despite analytical evidence to the contrary), or how it ���does not promote inclusivity���, is basically political mischief-making that must be roundly denounced and firmly rejected.

But this hostile attitude by the political class towards the constitution should not surprise us. The constitution was imposed on them by the people through a people-driven process. And we must remember that they proposed more amendments to it on the floor of the House than there were articles in the constitution. To be sure, when the political class finds a constitution, a law or an institution to be an inconvenience, that is a clear indicator of success.

We must actively resist the schemes by the political class to hijack, mangle and wreck the constitution, and thus remove the checks that make the exercise of political power onerous. The constitutional product is only as good���and as secure���as the process that creates it. And whereas we must salute the decision of Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga to stop the grandstanding and step back from the brink to save lives, the framework for dealing with the issues that created the problem in the first place (such as electoral theft right from the party primaries to the general election, ethnicity, police brutality, and vigilante massacres) should have been broader, more structured, and more inclusive than the present process which is private, exclusionary, unstructured, and partisan.

The moral bankruptcy of the political elite is pushing us into a false choice between ���dynasties��� and ���hustlers������a very superficial and shallow narrative masquerading as a class-based political contest yet it is merely a joust between gangs. It is a (mis)-framing that obscures the underlying forces that create underdevelopment, instability and violence and those who benefit from the end result. We must not buy into this misframing of our political choices, whose guile in placing a confederacy of familiar surnames on one side, and a well-known economic rustler of public assets on the other, seeks to hide the common denominator of those two groups: the plutocrats within the state that are the beneficiaries. Both are extractive and extortionist, only distinguished by the differences in their predatory styles and their longevity in the enterprise of shaking down the Kenyan public. This is a club, a class of state-dependent ���accumulationists��� and state-created ���capitalists��� united by a history of plunder of public resources and unprincipled political posturing, and only divided by the revolving-door cycle of access to the public trough.

My second argument as to why, despite the many progressive political and constitutional transitions the country still feels restless and dissatisfied, has to do with the performance and the posture adopted by parliament. Whereas the judiciary has emerged as an effective and consequential arm of government since 2011, simultaneously playing defender and goalkeeper of the constitution, parliament, has since 2013, and even more so now, acquiesced as an adjunct to the executive. In a complete misreading of the presidential system, parliament sees itself as an extension rather than a check on the executive. The senate is even worse; instead of playing its constitutive role of protecting devolution against the excesses and encroachment of the national government, senators got into the most parochial contest of egos with the governors, bizarrely siding with the executive to stream-roll and undermine devolution. It took the judiciary, through a number of bold decisions, and the public, who rallied around devolution, including in the ruling party���s backyard, to save devolution from an early collapse.

Third is the suboptimal output from devolved governments. Devolution has been good but is not yet great. Because of a hostile national government and endemic corruption in the counties, devolved governments have not performed optimally although, compared to the central government���s record of the last 50 years, they have made a big difference in people���s daily lives. Although devolution has been revolutionary, a combination of frustration from the top (especially from the Treasury, the Devolution Ministry (particularly the first one) and the Provincial Administration) and the extremely poor and corrupt leadership of some governors have delayed the devolution dividends.

I dare say that without the strong backing of the judges���a raft of decisions by the High Court and two decisions by the Supreme Court on the Division of Revenue Bill���devolution would long have unraveled. These decisions are part of the reason for the animosity towards the judiciary that we have witnessed in the last decade.