Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 160

September 9, 2020

Carceral feminism is not the answer

Image by Ichigo121212 from Pixabay

Last year, South Africans took to the streets after the tragic rape and murder of Uyinene Mrwetyana, a University of Cape Town student murdered by a postal worker. Mrwetyana became the latest brutal instance of gender-based violence to make headlines. Thousands marched on university campuses, the World Economic Forum on Africa in Cape Town and the South African Parliament asking #AmINext? These protests were neither the first nor the last protests against gender-based violence in South Africa, a country in which seven women and three children are killed every day and which ranks fourth in the world for our rates of femicide. It is understandable, in this horrifying context, that South Africans are angry and that many of the demands and solutions put forward have centered around retribution, policing, and incarceration.

Addressing protestors in September 2019, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared that ���Men that kill and rape must stay in jail for life. The law must change that once you have raped and kill you get life, no bail.��� His statement was a response to various calls to deny bail to those accused of gender-based violence, establish more police stations and special courts, impose mandatory life sentences and even bring back the death penalty. These demands and Ramaphosa���s statement are in line with what is known as ���carceral feminism.���

Carceral feminism views increased and improved policing and imprisonment as the primary solution to violence against women. It has been much criticized by black, queer and leftist feminists but has unfortunately been embraced by an increasingly desperate South African population. In the South African marketplace of ideas, carceral feminism has established a monopoly.

Part of carceral feminism���s allure is in how it presents itself as a logical and ideologically neutral approach. Sure, we must do more to end violence against women, it tells us, but our starting point must always be prison. Imprisoning dangerous rapists is objectively necessary, objectively good. It is easy to buy into this view, especially when reading yet another headline about yet another brutal murder. This approach however, is wholly acontextual. Analyzing the reality of prisons and policing reveals that they are at best unhelpful and at worst actively harmful to victims and the cause.

Most victims do not report abuse or violence. A 2017 study in Gauteng province revealed than only about 1 in 23 women who had experienced sexual abuse reported it to the police. This unwillingness to report is due to a variety of factors, including the fact that most people experience abuse or sexual violence at the hands of someone they know and potentially care about, most often their partner. Many victims want the abuse to stop but do not necessarily want a family member, friend or partner to spend years in prison. An unfortunate reality in South Africa is that many victims also depend on their abuser for financial support, support that would end with their abuser behind bars.

Additionally, many victims are acutely aware that when attempting to report, they will be met by misogynistic, homophobic or transphobic police officers. Numerous studies have reported that police officers have an inadequate understanding of the law, engage in victim blaming and view domestic violence as a private family matter rather than a crime. Social media abounds with stories of victims who have been dismissed and told by police officials to go home to their abusers. Carceral feminism, while recognizing these problems, generally argues that they are easily fixed.

As a result, we have seen activists advocate for equipping police officers with better resources and sensitivity training in the hope that this will create a more welcoming environment for victims. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Sensitivity training has been proven to be largely ineffective. In The End of Policing,�� American sociologist Alex Vitale shows that most police officers view sensitivity training as a political exercise that has no bearing on the reality of their jobs. Additional training and resources simply pours more resources into a failing system. If the South African Police Service is able to effectively quash protests and illegally evict people from their homes with its budget, we must consider that its failure to respond to GBV is a matter of will not of resources.

But even if the system worked perfectly, if police took their jobs seriously, if courts were not groaning under the burden of extreme caseloads���the nature of a criminal trial, with stakes so high that it might end with someone sentenced to years in prison, demands that the onus must be on the state to prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt. This means that victims must rehash their abuse for an audience, endure harsh cross-examination and have their story picked apart in front of them. Often, prosecutors choose not to let victims testify, for fear that their emotional testimony will damage the case, but even where they do testify, victims are at best mere witnesses in trials about their own experiences. It is ultimately the state and not the victim that is a party to the case and that makes decisions such as whether to prosecute, whether to accept certain plea deals, what evidence to raise, which witnesses to call, and what sentence to ask for.

Additionally, the entire process is adversarial, a hostile form of legal combat rather than a truth-seeking exercise. The trial process, even when working perfectly, is one that strips victims of control and relegates them to the sidelines, watching as others make decisions about what happened to them, often in a language that they barely understand. It is an inherently violent process��� and it is generally an unsuccessful one too. Few prosecutions result in convictions because the nature of abuse is such that there are often very few witnesses, very little evidence beyond the claims of those involved and the burden of proof is always in favor of the accused who is innocent until proven guilty. In fact, a national study in 2012 found that only 8.6% of rape cases resulted in a guilty verdict.

On the rare occasions that prosecutions occur and result in convictions, victims are left retraumatized, with generally no reparation, support or closure beyond the knowledge that their abuser is in prison. And the accused is in prison. Many would argue that this is no less than what they deserve and while this response is understandable, it ignores a wide range of literature that has proven that many sexual offenders in prisons in South Africa have histories of dysfunctional families and abuse, childhood trauma, addiction disorders and low socio-economic status. The average offender is not a serial rapist and murderer, but someone who knows their victim and is often a victim themselves, failed by a society rife with abuse and inequality. We banish this person to prison, which is itself a site of massive levels of extreme violence, sexual assault, and rape. There is an assumption that at the very least imprisonment prevents the offender from committing acts of violence while they are imprisoned, but all we really do is contain this violence within prison walls. We rest easy knowing that rather than harming the people ���outside���, imprisoned people are harming or being harmed by people ���inside.���

Furthermore, prisons in South Africa entrench violent masculinity through gang systems and the use of violence and rape as a form of coercive power. Our rehabilitation programs are poorly resourced and poorly designed. In general, people leave prison not having ���learnt their lesson,��� but thoroughly dehumanized, mistreated, and with a decimated support structure. In the case of sexual offenders and abusers, they also leave having had none of their perceptions of women challenged and generally having imbibed an even more violent form of toxic masculinity. As a result, recidivism is rampant in South Africa. It is estimated that between 55-95% of prisoners in South Africa reoffend upon release. Prisons therefore do not end sexual violence but perpetuate it, and leave offenders more likely to use escalated sexual or other violence in the future.

Given the sheer magnitude of evidence pointing to the failure of the criminal justice system to prevent gender-based violence, we must ask ourselves why we continue to put our faith in this system. Most likely because prisons have so effectively cemented themselves in our collective imagination, most likely because it is easier to lock individuals in cages and call it justice than it is to truly challenge the structures that cause gender-based violence. The Santa Cruz Women Against Rape argue that rape cannot end within the present capitalist, racist, and sexist structure of our society. A fight against rape must thus be a fight against all forms of oppression, and prisons that have functioned as tools of colonialism, Apartheid and capitalism for centuries are incapable of furthering this fight.

A solution to gender-based violence that does not include prisons must thus tackle a range of oppressions and must include a network of alternatives working in tandem to crowd out prisons. If we know that many sexual offenders in South Africa struggle with trauma, addiction and poverty, then our solutions should tackle those root causes. The black radical feminist Angela Davis argues that revitalizing the education system, providing free mental and physical healthcare, and addiction services provides powerful alternatives to prisons. Immigrant and refugee women in Canada implemented a strategy that shows on a small scale the success of these interventions in empowering victims to leave abusive situations. They created an informal support group, offering one another emotional support and childcare assistance. They formed a cooperative catering business to allow them financial independence and used the profits to offer housing assistance that enabled women to leave abusive relationships. There are a range of social movements in South Africa similarly advocating for access to quality education, housing, healthcare, economic justice, and social welfare. These organizations may not consider themselves abolitionists, or even feminists, but the services they fight for have the potential to prevent violence and abuse.

Anti-rape groups in the USA have also been successfully exploring a range of alternatives including community block watching, organizing at workplaces to prevent sexual harassment, starting self-defense classes, training people to respond to a call for help, and orchestrating confrontations that allow women to confront their abusers with the support of their families and friends.

South Africa has the potential to embrace these strategies. Some are even mentioned in the National Strategic Plan on Gender-Based Violence and Femicide. Encouragingly, it establishes changing social norms, providing support to victims and economic empowerment as a key pillars of its strategy.

South Africa has also acknowledged the central role of restorative justice in our legal system. Restorative justice is victim-centric, reconciliatory and reparative rather than retributive. It involves families and communities in addressing and preventing harm and has proven its merits. Criminologists Sherman and Strang analyzed the results of 36 studies from around the world comparing the efficacy of restorative justice with conventional criminal justice. The studies showed that restorative justice significantly reduced repeat offending, victim���s post-traumatic stress symptoms and desires for revenge and reduced costs, thus allowing more offenders to be brought to justice. Both victims and offenders reported more satisfaction with restorative justice than with the criminal justice system. Unfortunately, neither restorative justice nor the progressive solutions put forward by the National Strategic Plan have been widely implemented.

We have before us a plethora of alternatives, many of which have proven to be more effective than the status quo. Divesting from carceral feminism will require more than minor reforms and budgetary allowances by the state. It will require the state, as well each of us, to invest in structures of community care and accountability. It will require a complete restructuring of the way we think about justice but it is vital if we are to build a South African feminist movement that is truly dedicated to equality and liberation. Perhaps there is no perfect alternative, but there must be something better than what we have settled for. Putting people in cages is not liberation and prisons are not feminist.

Nigeria’s faltering anti-corruption war

Abuja & Environs. Image credit Juliana Rotich via Flickr CC.

On July 7, 2020, the Nigerian Presidency announced the suspension of its anti-corruption czar, Ibrahim Magu. Hours before, Magu had been forcefully ���detained��� and made to face a panel in the President���s official workplace and residence, Aso Rock. The Nigerian Presidency���s suspension of Magu and the tepid reaction to this decision both highlights the cyclical nature of Nigeria���s anti-corruption drive, but might also signal its end. Since 2017 Magu has led, albeit in an acting capacity (Magu was twice denied confirmation by Nigeria���s Senate), the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). The agency has been at the forefront of Nigeria���s anti-corruption efforts since its formation in 2003. Despite enduring popular support for anti-corruption, the commission���s history, as with many of Nigeria���s other anti-corruption efforts, has been marked by inconsistency and has been unable to make any long-lasting effects on the country���s endemic corruption. While most of the commentary on the arrest of Magu has rightly focused on the government���s disregard for due process or has focused on the power play within the Presidency, these analyses offer a snapshot but fail to proffer a historical explanation for the predictable manner that various administrations, especially in the fourth republic (since the end of military dictatorship in 1999) have treated corruption.

The Nigeria���s government���s approach to tackling corruption has often been phrased as a ���war���. However, in reality, Nigeria has rarely sought to battle the act in its entirety; rather it has focused on selectively enforcing anti-corruption laws aimed at an elite that it is opposed to. In 2015, Nigeria looked to turn the corner with the election of Muhammadu Buhari as President, dislodging a 16-year federal incumbency that had held steady since the country���s return to democracy. Few Nigerian politicians possess a higher degree of valence on the issue of corruption than Buhari. His ownership of anti-corruption as a cause stems from his actions as head of state for a brief period in the mid 1980s (these included freezing bank accounts and military tribunals for public officials accused of corruption) and his austere lifestyle afterwards. His promise to rid the country of corruption seemed to herald a change in Nigeria���s anti-corruption approach. This time it is different: Quite the reverse has ensued as Buhari has made no significant deviation in the tactics employed by previous Nigerian governments on the issue.

Traditionally, the Nigerian anti-corruption approach has often swayed between three approaches: ratifying good governance measures, enacting mass mobilization programs, and a reliance on anti-corruption fighters.

The first (ratifying good governance measures) focuses on adopting legal measures such as public procurement rules that establish procedures for public official behavior, with the creation of agencies with the wherewithal to punish those that err. For instance, the Buhari administration���s commitment to the Treasury Single Account, which consolidates and merges all government revenue within a single central bank account signifies the former. This approach usually confirms to ���best global practices��� or treatises pushed forward by multinational actors such as NGOs, development finance institutions, and global charters. Institutions such as the Nigeria Financial Intelligence Unit (NFIU) largely owe their existence to such measures. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a G7 initiative whose remit was expanded in the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks in the US to counter money laundering and terrorism financing, largely led to the creation of the unit alongside the threat of a blacklist of the country on international financial transactions. The unit has been pivotal not only in providing information to tackle suspicious money flows, but has recently sought to end the nefarious practice of state governments withholding or deducting funds allocated to the local government by the federal governments. Previously, state governments received federal allocations for both themselves and the local governments within them. However, state governments have treated these funds as their prerogative and often spent them with little or no recourse to the original intent of these funds. However, the success of this approach has been limited as Nigeria���s political elite have shown themselves adroit at moving toward reforms suggested or foisted on them by external forces, only to renege or find a way to bypass such commitments when it comes to implementation.

The second approach adopted to fix corruption is through mass mobilization programs, but limited to the messaging and campaigns aspect, often run by the country���s anti-corruption agencies and the National Orientation Agency. The media campaigns that accompany them often consist of tough and aggressive language intended to brook no room for disagreement or noncompliance.

In the run up to the 2015 elections, coverage of the then-opposition candidate, Buhari, provided an avenue to reappraise the achievements of his short-lived military administration in the 1980s. The flagship policy of that administration, the ���War Against Indiscipline,��� was a mass mobilization social orientation program intended to discourage certain ���social vices.��� The program administered by government officials introduced and enforced draconian legislation to ���restore orderliness��� to Nigerians. They included 21-year prison sentences for students cheating on exams, the death penalty for drug offenses or soldiers whipping commuters at taxi ranks for not forming straight lines. Its focus on corruption, specifically on the corrupt everyday activities that Nigerians engaged in, made it initially popular among the masses until its heavy-handedness led to it rapidly becoming unpopular before the regime fell. While the program itself was neutered then scrapped by a successive government, subsequent governments, both civilian and military, have sought to borrow elements of this approach, mostly evidently its��� anti-corruption messaging and orientation campaigns. The main flaw of the mass mobilization approach is the fact that it ignores the fact that the insidious cycle of corruption is spun and kept turning by the political elite. Consequently, a political elite that seeks to wean Nigerians off corruption has shown no disposition toward changing their behavior.

The weariness of Nigerians to this approach was made evident with the most recent iteration. The ���Change Begins With Me��� orientation program launched by the current Buhari administration failed to secure any public goodwill as few Nigerians believe that the government possessed the political will to tackle corruption within the political elite or that the elite were willing to change their behavior. For instance, after the launch of this orientation program, President Buhari was shown to dither after his then Secretary General of the Federation, Babachir Lawal, was implicated in a corruption scandal. The President���s initial decision to back the appointee against the allegations by the Senate, furthered by the fact that the eventual decision to terminate his appointment was made after a six month long committee headed by the Vice-President Yemi Osinbajo, provided indications of unwillingness to tackle corruption within his camp. In comparison to this, it took less than a fortnight to detain, suspend, and fire Magu.

The third and final approach to Nigeria���s anti-corruption efforts is its recruitment of Elliot Ness-like figures to lead its anti-corruption efforts. Eliot Ness led the famous Untouchables, the law enforcement team that brought down Al Capone and enforced prohibition in Chicago. The pioneer chair of the EFCC, Nuhu Ribadu, a police prosecutor, has been the standard that successive anti-corruption chiefs must aspire to. Ribadu was popular among international donors, civil society, and the press.

The anti-corruption war Ribadu waged from his position at the EFCC led to the arrest and conviction of powerful members of the elite, ranging from fraudsters who had avoided foreign law enforcement agencies, bank executives who had misappropriated shareholder funds, state governors, and even his boss the Inspector General of Police. Other high-profile Ness-style players that have sought to tackle corruption since Nigeria���s return to democracy have included ministers such as Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala at certain periods, and arguably, even Buhari himself.

Nigeria is not alone in applying this approach to fighting graft, and it shares similarities with two other African countries that are also significant economic players on the continent, Kenya and South Africa. In her book on John Githongo, Kenya���s own anti-corruption crusader, the journalist Michaela Wrong argued that the promise for the African continent getting it right on corruption, rested on a tripod of countries that consisted of Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa. The assertion seemed prescient as the end of the Cold War had changed the priorities of Western financial institutions, such as the World Bank. James Wolfensohn, World Bank President (1995 ��� 2005) regarded corruption as a development issue and sought to partner with recipient countries to tackle it. His successor, Paul Wolfowitz (2005 ��� 2007) pushed the issue to the top of his agenda during his short-lived stint.�� Furthermore, during this policy shift, the emergence of a different breed of politicians in these countries seemed to herald some promise. Newly elected presidents Olusegun Obasanjo (1999), Mwai Kibaki (1999) and Thabo Mbeki (1999), all seemed to differ from their predecessors and identified corruption as an issue. Each of them bolstered this fight with Ness-like figures, Nuhu Ribadu (Nigeria), John Githongo (Kenya) and Vusi Pkoli (South Africa). The end results were strikingly similar, with initial successes being recorded until these crusaders were forced to prematurely end their efforts as the political will afforded them to tackle corruption waned.

Historically, the Nigerian government has sought to use these approaches concurrently or separately, and even within the administrations that enact them these efforts are rarely sustained. After his 2015 first term, Buhari sought re-election in 2019, and his campaign was largely silent on the issue of corruption. Any mentions were limited to celebrating the implementation of the Treasury Single Account (TSA) as a ���blow against corruption.��� His focus on the use of good governance reforms to tackle graft is far below the standards Nigerians expect, especially since it was the approach that his predecessor, Goodluck Jonathan, claimed to have implemented. In fact, the TSA had begun gradual implementation and was conceptualized by that administration. There is a clear and deserving focus on the high-level corruption perpetuated by Nigeria���s political elite and the measure of an effective anti-corruption approach is ensuring that the most visible scandals that have plagued the country are resolved through both the recovery of stolen funds and an effective prosecution of the participants.

In essence, promises by the President to strike a decisive blow against corruption have largely gone unmet and few believe that this is likely to change, especially since his actions will have to begin within many of the stakeholders within his party and cabinet. Nigeria���s biggest strides in its anti-corruption efforts have historically occurred as a result of external pressure exerted on the ruling elite. The economic crisis of the 1980s led to the welcoming of the war against indiscipline, the blacklisting of Nigeria by the FATF led to the formation of the NFIU and the EFCC, and Nigeria���s perceived entry into its deepest recession in recent years might be the most potent force in its efforts against corruption. Rooting out corruption is an admirable priority; however, the selection of the same tactics, their lackluster application, and the general unwillingness to try any new methods leads to the belief that Nigeria���s political elite have no genuine will to address corruption in order to be accountable to all Nigerians.

September 8, 2020

Religion outside the law

Image credit Adam Rozanas via Flickr CC.

For a long time, the way scholars have associated the connection between religion and physical violence has been with competition between different religious groups where the weaponization of antagonism and resentment in violent clashes served to enhance the power of one group at the expense of the other. From the conflict between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland and clashes between Hindus and Muslims in India, to the violent struggles between Muslims and Christians in Nigeria, violent religion seems to pivot on the sharpening of group boundaries.

Something entirely different appears to have happened on July 11, 2020 when five people were killed in the headquarters of the International Pentecostal Holiness Church in Zuurbekom, outside of Johannesburg. An armed ���splinter group��� violently entered the premises, set alight a car with four people on board, shot randomly inside the church building and held large numbers of people hostage until security forces ended the attack. According to the church leadership, this was just one in a series of attempts by the group to literally capture the headquarters and take over the church (which has an estimated membership of three million people). The fights go back to the death of church leader Glayton Modise in 2016 following which struggles over his succession involved the attackers and Modise���s sons. Ever since, nine people have been killed in violent assaults. While surely spectacular and perhaps unique, I suggest these events illuminate some of the broader dynamics underlying religious life in South Africa and the way it has become embroiled with its criminal economies.

Church schisms and struggles over succession are extremely common in South African Pentecostalism and in fact, are one of its constitutive features. As a highly decentralized part of South Africa���s religious field, Pentecostal churches are usually run by pastors who attract followers with their charismatic gifts, such as their alleged capacity to mobilize the power of the Holy Spirit to produce miracles. In a system where positions of authority are not acquired via formal theological qualification but through socially validated ���callings���, it is the theological idea of spiritual gifts that allows religious contenders to rise to prominence. These are men who, after being called by the Holy Spirit to serve God, at some point feel they have ���matured in the faith���, meaning they are able to open their own ministry and do so by taking part of the flock with them. In my research, time and again I have seen pastors struggling with secession and losing parts of their membership.

Importantly, while for pastors members mean money, most churches are very small and they do not have liquid assets. As a result, they rarely incite the fantasies of predators and conflicts related to schisms remain low key. This is clearly different in churches of the size of the International Pentecostal Holiness Church, which has been able to grow more or less constantly throughout the almost 60 years of its existence. It seems clear that the larger the churches, the more likely they are seen as a rent to be secured in moments of succession or schism, as a prize to be seized and capitalized.

Powerfully playing into these dynamics is the fact that in South Africa, religion is more and more viewed as a market by both pastors and believers. Pentecostalism has become something like a lucrative profession, inspiring the fantasies of spiritually inspired men, and sometimes women, to make a living or even wealth by becoming pastors. This has massively increased the competition in a now crowded field of actors who claim to protect their followers against misfortune and evil spirits, the forces seen as blocking their road to a life of abundance. Fueling rivalries among competitors, churches such as the Brazilian Universal Church of the Kingdom of God work to popularize the so-called ���Gospel of Prosperity��� which promises miracles and wealth in exchange for personal ���sacrifices.��� Poor pastors in the country���s townships have grown increasing wary of this,�� as well as of the rise of new���and in their eyes illegitimate���competitors with no spiritual credentials, calling them�� ���mushroom pastors.���

Already in 2015, these developments prompted the governmental ���Commission on the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities��� to undertake a critical investigation into the commercialization of religion. One central concern of the commissioners was that religious organizations, while being non-profit on paper, were actually profit-driven enterprises; enterprises whose book-keeping they found highly wanting. The upshot of all this is that churches are seen as places for the accumulation of money whose moral status is, in the eyes of an increasing number of South Africans, dubious or at least questionable.

These have drawn religious life into the circuits of South Africa���s illicit economies where they have fostered criminal forms of religious rent-seeking and predatory profit-seeking. Some pastors have been accused of providing spiritual protection for criminal gangs in exchange for money. There are also peculiar links between the world of private security firms and Pentecostalism, with some pastors having part-time jobs as guards to gain access to firearms. What is more, bigger churches have their own heavily armed security teams which operate as militias outside the law. During the hearings of the commission mentioned above, some church leaders entered the venues accompanied by such paramilitary forces parading AK-47s and openly issuing death threats against members of the commission. The suspects arrested after the Zuurbekom attacks include a police officer, a member of the South African National Defense Force and a Johannesburg Metro Police Department official who used their police guns in the assault. The events point to the blurry boundaries between law enforcement, criminal economies and religion. As Abiel Wessie, chairman of the church���s executive council said in a press interview: ���They have decided to take the law into their hands.���

David Graeber, Africanist

David Graeber speaks at Maagdenhuis Amsterdam. Image credit Guido van Nispen via Wikimedia Commons.

I had only one opportunity to see David Graeber speak, over a decade ago now when I was teaching at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This was before Occupy Wall Street and before the publication of his now classic books Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011) and Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (2018).

It was an afternoon event, attendance was low, and there were maybe fifteen people at the most in the room, graduate students primarily. I knew little about Graeber at the time except that he had controversially been denied promotion at Yale, had a reputation for espousing anarchism, and had a foot in African Studies. True to an anarchist sensibility, there was no formal lecture as such. Graeber was introduced, and he proceeded to speak very briefly about his work on ethnography and social movements, a project that would become Direct Action: An Ethnography (2009). He then opened the floor to questions, or, more precisely, conversation. Under normal circumstances, this kind of approach can lead to disarray and disinterest, but with Graeber, it became more interesting and meaningful. Graeber was a storyteller and a listener���comfortable fielding questions with good humor, but equally comfortable receding into the background to let a student speak at length about their work. There was no general conclusion he wanted to transmit, and he was unconcerned with coming across as an authority in his field. In a way both quiet and intentional, his approach that day was one positioned against the hierarchies that define academia and society more generally. He appealed to the possibilities that a classroom held for collapsing social inequalities we encounter on a daily basis, if only for a temporary moment.

���I was first drawn to Betafo because people there didn���t get along.��� This is the first line from Graeber���s Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar (2007), which foreshadows a dominant theme in his subsequent work. I venture that Lost People is his least read book. This is a shame. I won���t provide a review, but first monographs can reveal in detail the origins of later ideas. Graeber did publish two preceding books more conceptual in scope���Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value (2001) and Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (2004)���but Lost People was based on his doctoral dissertation fieldwork, which he pursued under the supervision of Marshall Sahlins at the University of Chicago. Graeber claimed it was his best book. As he notes in the preface, he brought a number of works by Dostoevsky along with him to pass the time during his research, and the Russian master became an unanticipated reference point for his thinking. What follows in Lost People is a freewheeling narrative both descriptive and analytic, full of ideas and characters in a manner similar to a nineteenth-century Russian novel. Though ���magic��� and ���slavery��� are in the subtitle���undoubtedly key words designed to drum up sales���the book also dwells beneath these rubrics to address ideas such as negative authority, concepts of personal character, the hierarchy of tombs, and indigenous practices of astrology. As Graeber further notes in the preface, he was urged by colleagues to reduce the book to a single idea, concept, or argument, which he proceeded to refuse. ���A culture isn���t ���about��� anything. It���s about everything,��� he writes. ���People don���t live their lives to prove some academic���s point.���

Lost People has an all too familiar story at its center: the struggle between those who descended from masters and those who descended from slaves. This take glosses a lot of complexity within Graeber���s account and the diverse ways in which those of ���noble��� status had lost their standing, while those of slave lineage had empowered themselves over time. Pertinent to his later work is his discussion of ���temporary autonomous zones��� (also called ���provisional autonomous zones���). As Graeber describes:

The idea is that, while there may no longer be any place on earth entirely uncolonized by State and Capital, power is not completely monolithic: there are always temporary cracks and fissures, ephemeral spaces in which self-contained communities can and do continually emerge like eruptions, covert uprisings. Free spaces flicker into existence and then pass away. If nothing else, they provide constant testimony to the fact that alternatives are still conceivable, that human possibilities are never fixed.

This perspective, drawn from the anarchist tradition, informs his view of the political conditions observed in Lost People, but it also foretells the politics of the Occupy movement, which emerged two decades after Graeber���s doctoral fieldwork.

Anthropology has a distinguished lineage of thinkers who have engaged anarchism as an approach, including Pierre Clastres and more recently James Scott. Anarchism is often construed as being without moral principle, even violent���a reputation gained through the ideas of the nineteenth-century anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, who lived under the insufferable conditions of Tsarist Russia. This popular impression is misleading on both counts. Anarchism at its best is about working against existing political institutions (direct action) to achieve immediate political participation (direct democracy). Anarchism rejects the constraints of electoral calendars and statist representative bodies. It believes that political action does not depend on such accepted institutional features or, equally significant, on money���political power is there if you seize it. Solidarity with others (mass action) makes this possibility even more concrete. Anarchism, then, is not only a political approach, but also a critical position���one resistant to ideological conformity, political custom, and, as seen in Graeber���s wildly imaginative later work, mainstream academic fashion. Graeber was consistently alive to the possibilities of the political present and the ways in which scholarship could contribute to such conditions���to itself be a form of direct action.

In early November 2011, I visited New York for a weekend and had a chance to witness the Occupy Wall Street encampment in Zuccotti Park in Lower Manhattan���to see the working of Graeber���s ideas firsthand. The scene was what one might expect from watching weeks of news coverage that had started in September when the occupation began: a collection of young student activists with older activists, many of them members of the civil rights generation, populating a block filled with tents that provided shelter, cooking spaces, a library, medical aid, and what looked like classrooms. On the edges of this provisional autonomous zone were people holding declarative signs, delivering extemporaneous speeches, appealing individually to visitors such as myself, helping other occupiers, knitting, and simply reading. Graeber, naturally enough, was nowhere to be seen. The encampment would be forcibly removed by police only a couple of weeks later on November 15, but the lesson was already there���despite the Occupy movement���s limitations, a deep humanism is possible if you are willing to seize it, to organize and create it, without permission of the state or any other authority.

Graeber will undoubtedly be remembered for many things and will be a pivotal figure in future histories of the left since the end of the Cold War. However, I think it is important to assert his origins as an Africanist with some of his best ideas first taking hold in Madagascar. Though his intellectual curiosity and political commitments would take him further afield, it is hard to read Debt or even Bullshit Jobs, a study of office work, without thinking of his discussions of colonialism, labor, moral obligation, and what he called ���magical action��� in Betafo. Indeed, as indicated earlier, ���action��� is a keyword throughout his work, with ���political action��� replacing ���politics��� and ���historical action��� replacing ���history��� in order to highlight ���the play of human intentions��� among the people he encountered, as explained in Lost People. Starting in the Central Highlands of Madagascar, Graeber���s scholarship and activism were ultimately defined by this search for active freedom and the alternative humanisms that could sustain it. In his words, ���[i]t���s not that I am trying to deny the degree to which their lives are shaped and constrained by larger forces; I just don���t want that to be the only point.���

September 7, 2020

The exiled writer from Equatorial Guinea

Juan Tom��s ��vila Laurel with family in Equitorial Guinea. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.

In 2011, Equatoguinean writer Juan Tom��s ��vila Laurel fled his country. He had been on a hunger strike against the 41-year-old dictatorship of President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. Laurel ended up in Barcelona, Spain, his country���s former colonizer. The Catalan journalist and documentarian Marc Serena���s 2019 film El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as (The Writer from a Country Without Bookstores) combines a biopic of Laurel with a critical examination of Obiang���s regime. Originally titled Guinea, el documental prohibido (Guinea, The Forbidden Documentary), the project shifted last year to incorporate Laurel���s life story, resulting in a film with many powerful moments but a slight disjointedness, as if some parts were retrofitted onto an original storyline.

The film opens with a snapshot of Laurel���s place of birth (Annob��n) and early years followed by a quick overview of Spain���s colonial history in Equatorial Guinea (with archival footage), interspersed with quotes from Laurel and shots of his daily life in Barcelona. (Equatorial Guinea was colonized by Spain from the late eighteenth century until independence in 1968.) We see Laurel speaking at a decolonization lecture series and then teaching secondary school students about his home country and the circumstances that led to his exile, and we also start to learn (with Equatoguinean television footage and clips from Obiang���s son���s Instagram account) about the deep-seated corruption in the country. All of this sets the stage for a location shift to Malabo, where the rest of the film takes place, Laurel guiding us through the city.

Laurel teaches students in Barcelona about Equatorial Guinea. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.

Laurel teaches students in Barcelona about Equatorial Guinea. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.Laurel shows us fisherman on the shore, the home of his extended family in Malabo, and some parts of the city before sitting down for a beer with a few friends (among them novelist Trifonia Melibea Obono and musician Negro Bey) where they have a discussion about cultural stagnation in the country and the difficulty of increasing engagement with the arts, particularly amongst youth. Obono flatly points out that even though there is a generation of Equatoguinean youth eager to consume art and culture, there is not a place to do so (alluding to the title of the film). In an August 2020 interview, Laurel elaborated on the title of the film, affirming that there were indeed no bookstores when he was growing up, and although one opened in Malabo in 2010, it was closed when the documentary was being made. In spite of being in the company of other writer friends, very little is said about Laurel���s own literary work apart from the occasional interspersed quote, usually decrying the political situation of the country.

Laurel began writing in his teens (the 1980s), winning prizes for his poetry and plays at the Spanish-Guinean Cultural Center���s literary contests in Malabo. Although his native language is Annobonese Creole, Laurel writes exclusively in Spanish, and to date, two of his more than a dozen books, By Night the Mountain Burns (2014) and The Gurugu Pledge (2017), have been translated into English. Many of ��vila���s fiction and poetry works have autobiographical elements, though he has also written two nonfiction books, Guinea Ecuatorial, V��sceras (Equatorial Guinea, Entrails) and El derecho de pernada: C��mo se vive el feudalismo en el siglo XXI (The Lord���s Right: How Feudalism Lives on in the 21st Century), the latter of which is quoted in the film to explain how the major businessmen of Guinea are ministers or army generals in the government who rely on Obiang and his policies to sustain themselves. American author William Vollmann wrote (of The Gurugu Pledge) ���Here is the voice of someone who has courted and suffered persecution for the sake of a better world,��� and Spanish professor and Equatoguinean literature specialist Elisa Rizo wrote in 2004 �����vila Laurel focuses on the fictionalization of Guinea���s early 20th century colonial past as an opportunity to deconstruct���within the framework of the genre of the novel���the colonial ideology that underpins modern historiographic discourse��� (my translation). Indeed, even from the few charged quotes of Laurel���s in the film, one gets a sense of his dissident zeal, reminiscent of Arundhati Roy���s eschewing of ���prosaic, factual precision when maybe what we need is a feral howl, or the transformative power and real precision of poetry.���

Malabo’s pristine, desolate expressways. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.

Malabo’s pristine, desolate expressways. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.We accompany Laurel to a theatre performance and afterward to a bar, providing a glimpse into Malabo���s nightlife scene. Laurel narrates his own words about the petroleum-based economy of Equatorial Guinea and the symbiotic-nepotistic relationship between the Obiang���s government and the country���s private sector while we see images of poverty on the streets juxtaposed with shining skyscrapers of the petrol companies. Laurel also criticizes Christianity as we watch a church choir singing, commenting that ���Christianity���s idea of the afterlife gives people reassurance that God will judge them, but when you entrust the judgment of your present to a future you do not know, you are lost��� (my translation).

Indeed, the history of Christianity in Equatorial Guinea is a long one. Portuguese colonization of the islands in the fifteenth century brought Catholicism, and Spain���s acquisition of the colonies in the eighteenth century spread it pervasively. A 2010 Pew Research Center study found that 88.7% of the Equatoguinean population was Christian, making it Africa���s tenth-most Christian country by percentage of population, though the second-most Catholic country in the continent (after the Seychelles). Today (and for the past few decades), the Obiang regime appears to have a tight grip on the Church. An anonymous internal ecclesiastical source noted in a 2012 article that ���One way [of offering hope to suffering people] is through homilies, but���We must be very careful, because spies come to the masses to control what is said. All of Guinea is a big prison��� (my translation). Bubi (an ethnic minority���the vast majority of the Equatoguinean power structure is Fang) priest Jorge Bita Caec�� was assassinated in 2011, and another anonymous source notes (in the same article) that ���critical priests are murdered and not even investigated���[yet the bishops] seem to speak only of heavenly music��� (my translation). Laurel���s denunciation of Christianity juxtaposed with the jubilant choir singing uplifting lyrics renders the scene glum, almost farcical.

The broken public infrastucture in Malabo. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.

The broken public infrastucture in Malabo. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.The critique continues with two of Laurel���s friends, discussing the heavy presence of armed soldiers and the draconian penal system. As before, Laurel���s identity as a political activist is foregrounded.

A long montage of television footage ranging from comically laudatory birthday celebrations for President Obiang to television talking heads lavishing praise on the government and Obiang himself, leaves no doubt whatsoever about the extent of media freedom and manipulation in Equatorial Guinea. The film culminates in a live performance of Negro Bey���s ���Carta al Presidente��� (���Letter to the President���). The lyrics (���Disinformation to the population, I call it a conspiracy to the nation���When I look at the big picture, I only see criminals that block culture, and the system defends them,���) openly and boldly criticize Obiang���s maltreatment of the country���s education, healthcare, and social state, and the song clearly shows that Bey is a supremely talented musician who ought to be better known both inside and outside of Equatorial Guinea.

Negro Bey performing Carta al Presidente. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.

Negro Bey performing Carta al Presidente. Still from El escritor de un pa��s sin librer��as.Overall, the film is a damning indictment of the Obiang government and the political and economic state of modern Equatorial Guinea. Laurel���s dialogues with his friends and the scenes from around Malabo breathe life into his political writings, though the absence of his fiction and poetry work and larger focus of the film on Equatorial Guinea as a whole suggest that the original title of the film, Guinea, el documental prohibido (Guinea, The Forbidden Documentary), may have been more fitting.

September 4, 2020

Bill Freund: Historian, Africanist, Intellectual

Bill Freund in Paris in 2015. Image via Wits University Press.

Bill Freund was a traveler. As an economic historian, he explored the ways in which the large forces of labor and capital shaped society over time, indelibly marking the present. As a curious person with an insatiable appetite for art and music and landscape, and an abiding interest in the small quirks of human character, Bill travelled the world, each trip bringing fresh joys and insights. South African academia was fortunate that he found���in its history, its sociability, and in its intellectual stimulations���a place that he could call home.

Bill���s first visit to South Africa was in 1969, when he went to Cape Town to work on his PhD on slavery, which he understood within Marxist terms as a mode of reproduction, arguing against contemporaneous liberal scholarship���s focus on race. His PhD (Yale, 1971) completed, his early career might be described as meandering, with several unsuccessful attempts to find a permanent academic position in the United States. He spent a little time in the UK, in the company of leading South Africanists such as Shula Marks and Martin Legassick. Before moving to South Africa in the mid-1980s, he lived and taught in Nigeria, at Ahmadu Bello University, and developed a love for the smells, tastes and culture of Northern Nigeria. In Zaria, he was appreciative of the brilliant scholars teaching alongside him, Nigerians and others, at what was then Africa���s largest university. He lived and worked in Tanzania, where he engaged with the international community of radical scholars such as Samir Amin, Lionel Cliffe, and John Saul. It is important to pinpoint just how different and alluring these experiences were to the community he joined in South Africa, where the ���model��� universities were white and aspired to Oxbridge, and where it was assumed in the 1980s that South Africa was the most advanced country on the continent.

Into the milieu of apartheid South Africa, Bill brought the eyes of the traveler. He had seen the past (Harvard, Yale, Oxford) and despised its bloated pretentiousness and lack of imagination. He had no romantic or nostalgic illusions about American democracy, seeing America (and its academic institutions) as a place of cramped conformity. He had seen the future (Ahmadu Bello University, Dar es Salaam), especially the coming distance between the postcolonial state and the radical scholars who had utopian dreams of a just society. In Dar, especially, he made friends with the South African academics in exile, and was angered by the ANC���s treatment of the Marxists, like David Hemson, who refused to toe the party line. A long month in India followed his time in Tanzania, observing the effects of Indira Gandhi���s rule which had just ended. It laid down in him a deep distrust of both nationalism and postcolonial political parties. The American who brought Africa to Durban: to appreciate that, we need to recall just how parochial South Africa was at the time. It was excessively important in the global imaginary, of course, as the struggle against apartheid was by this time internationally powerful. Yet on the whole South African academics were at the time mostly less concerned about what was ordinary about the country.

Bill came to South Africa ���for good,��� one might say, at one of its most intense periods, just after the formation of the United Democratic Front in 1983 and just when the state began a renewed and vicious clampdown on political resistance using the states of emergency. It was a heady political time and Bill was an astute and scholarly observer, quite comfortable to name contradictions even of left activism. His work on tin mining and labor, and his magisterial comparative study The Making of Contemporary Africa, are standard texts for courses all over the world. His work on development, sharply observed commentary on economic dilemmas facing postapartheid South African policymakers, strengthened critical scholarship for a generation of his graduate students. His work on Indians in South Africa, though he felt it fell a little short of his best, shows a remarkable grasp of the particularities of a minority community���s complicated navigation of apartheid. The journal that he co-founded and built, Transformation, uniquely retains an independent critical left voice in academia. He wrote with great elegance and ease, and with a self-confidence based on deep reading. He was a Marxist historian in method, carefully attentive to political economy and to the material underpinnings of power, while retaining a critical distance to the political forms that his Marxist friends embraced. He was not romantic about what he had to offer, never feeling the need to perform allyship with the political cause. Mostly, while he was a thorough leftist and egalitarian, he was impatient with the demands of struggle involvement and thought many white leftists were driven by a savior complex. This meant that he had a healthy and dispassionate distance from the factionalism that sometimes characterized South African left academia. The down side of it was that he did not fit easily into those academic cliques either, and as a result was not included to the extent that was justified by his meticulous scholarship. Later in his career, he was indeed sought after as a keynote speaker and invited to all the academic tables, but there were long years when he was appreciated but not celebrated by his senior colleagues. Despite what I thought of as a lack of generosity towards him, Bill was unfailingly generous himself. He read the work of his students and colleagues with care and insight, and with a rapidity that made you think that your work was the most important thing on his schedule. His intellectual range was incredible. I felt this power firsthand. He took me on as an MA student when my first supervisor, Jo Beall, was imprisoned, tortured and forced to flee the country. Despite my choice to work on a feminist reading of Inkatha (far from Bill���s own interests), I was enriched by his skillful ability to bring out the best arguments in my writing. I was especially emboldened by him to develop my anti-nationalist feminist thinking, which we laughingly contrasted to my everyday romance with the collective.

Bill had the gaze of an outsider, a quality that defined much of his life and which made him appreciate the underdog however that was defined. His parents were Austrian Jews who fled just before the war, settling eventually in Chicago in the US where he grew up in a world dominated by European emigres. His parents carried with them socialist beliefs and a complicated commitment to both secularism and Zionism. They had all the qualities of highly cultured Europeans but without the financial means with which to pursue their artistic and musical interests fully. Bill retained a lingering admiration for Viennese culture, and certainly had his own distinctive taste in classical music that he felt was his central connection to his mother. He spoke German, French, Dutch, Kiswahili, some Italian (self-taught), some Afrikaans and wished he had learnt more Hausa. He was learning Zulu. An only child, with a restless spirit, he made Durban his home and his friends his family. He gathered a group of people around him that included unlikely combinations such as feminists and his touch rugby friends. He was a bon vivant, whose love for good food, travel (we could barely keep up with his letters about his latest trip!), music, art and books was infectious and entrancing. He was fond of an afternoon snooze, and no matter if that had to be taken in the middle of a seminar in a hot summer classroom. He was insistently independent, with his friends holding thumbs that he would arrive in Johannesburg after a six-hour drive with his car and body intact (and, indeed, that no one would feel the brunt of his impotent road rage). The collapse of the vibrant intellectual community in Durban, precipitated by the disastrous management of the University of KwaZuluNatal, was keenly felt in the last decade of his life, although frequent trips to teach and visit his friends in Johannesburg alleviated this somewhat. His friendships were always for life and if you sped along with your own interests in a self-centered way, you could rely on Bill to bring you up to speed with news of others. Once retired, he was able to connect more intensely with his extended family of cousins and their children, which brought him great joy. And in his inimitable fashion, he sought out the next generation of brilliant young people in Durban, making them his new friends and family and sharing with us their gifts and achievements just as he once spoke of us.

Bill Freund: An historian���s passage to Africa, is due to be published in May 2021 by Wits University Press.

Missing datasets

Image via the Red Cross Climate Centre on Flickr CC.

I recently came across Nigerian-American artist Mimi Onuoha���s mixed media installation, The Library of Missing Datasets. The Library showcases a physical repository���a filing cabinet���of information that ought to exist, but due to cultural, social or other inherent biases or indifferences, does not. The incomplete list of missing datasets includes undocumented migrants currently incarcerated in the US and how often police arrest women for making false rape reports. This piece of work made me think about all the datasets that are currently blank spots in the response and recovery process to COVID-19 across Africa.

Since the start of the pandemic, there has been a deluge of online surveys on social media from entities such as the Uganda Investment Authority asking, ���Has your business been affected by #COVID19?��� The United Nations (UN) termed the rise in reported domestic violence cases�� ���the shadow pandemic.��� The UN Population Fund estimated that for every three months of lockdown, 15 million more cases of domestic abuse could happen than would normally be expected, and millions of women could lose access to vital services, such as access to contraceptives. Even more devastating than these predictions, the Kenya Health Information survey reported close to 4,000 girls under the age of 19 ���were impregnated��� in a single county during the lockdown. About 200 of these girls were under the age of 14. Now, the very wording of these articles is problematic but provides an important lens to understanding exactly what framing of issues and data are missing and, likely, forever lost since the start of the pandemic. How many teenagers, who didn���t make it into the health survey, resorted to unsafe abortions? How many other children were sexually abused or raped?

Several governments across Africa have done a relatively good job in providing aggregate data on coronavirus cases, though often lacking in granularity, and with considerable challenges in contact tracing. Some countries still remain closed, while others lack structured plans to re-open or to provide income replacement or other forms of assistance to the many millions of citizens who have suffered and lost their livelihoods under lockdown conditions. In Uganda, based on the observed increase in maternal mortality in early March 2020 compared to the preceding 2019-2020 average, an excess 486 deaths are predicted for a six-month period, incurring 31,343 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost. According to a recent Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria survey, 85% of HIV programs, 78% of TB programs, and 73% of malaria programs reported disruption to service delivery due to lockdowns, restrictions on transportation and COVID-19-related stigma. Estimates in some countries predict a 10%, 20%, and 36% increase in HIV, TB and malaria related deaths respectively over a five-year period.

However, these estimates cannot capture the true reality of the health outcomes across the continent. Data on morbidity and mortality from non-COVID causes but due to COVID lockdowns is largely missing���for example, women who died walking to hospital because public transport was cancelled. Data on the number of persons, mostly women, who suffer from Lupus-related pain due to shortages of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is missing. Data on the number of women who faced domestic abuse, and children who were sexually abused, is missing. Data on the response by governments to these women and children is, of course, also missing.

Furthermore, governments have largely ignored the needs of persons with disabilities, and other traditionally marginalized or minority groups, oftentimes resorting to violence to enforce restrictions and curfews. For example, from a global perspective, data released by the CDC in June showed that death rates among Black and Hispanic/Latino people are much higher than for white people, in all age categories. In Britain, Black citizens were up to two times more likely to die than white citizens. Other countries like France are still grappling with the ethics of collect data of race, ethnicity, and religion���affecting the country���s ability to protect the most vulnerable populations from the impact of the pandemic. However, data is crucial in guiding government decision-making, especially in the absence of an appropriate response to the needs of minority groups as articulated by civil society and local communities.

In Uganda, 19 LGBT+ persons were jailed for 50 days after their shelter was raided by police for violating social distancing rules, which banned gatherings of more than 10 people. In Nairobi, a 13-year old was killed by a stray bullet when police officers moved through his neighborhood in an attempt to enforce curfew. Also in Uganda, a young deaf and blind man was shot by a team of Local Defence Units in Agago District, in the northern region for breaking curfew, resulting in the amputation of his leg. How do caregivers for persons with disabilities practice social distancing? How do they get around when public transportation is restricted? How do persons with seeing or hearing impairments receive information on the pandemic?

In terms of educational outcomes, how do we even begin to measure the impact of COVID-19 on student achievement and learning losses? As of June 24, schools in up to 134 countries were either partially or completely closed, affecting more than 1 billion students. While wealthier, urban students can still tap into digital learning resources, their poorer and disconnected counterparts in both urban and rural settings will fall significantly behind. How many students are currently engaged in digital education? How many institutions are offering e-learning programs? What proportion of parents are able to contribute to home-schooling? We really don���t know.

Moving on to economic losses, the gaps in information are massive. Given that up to 85% of employment across Africa is informal, workers often lack any forms of social protection and are not adequately accounted for in research and planning. Market closures, disruptions to transportation, and reduced consumption have caused immeasurable suffering across the continent as a majority of businesses ground to a halt. How many businesses will never recover from the shock? How are people getting by with little to no support from the government?

An alarming assessment by the World Bank found that up to 65% of National Statistical offices were closed in the early months of the pandemic, resulting in major disruptions in the collection of essential and foundational data. These offices have been traditionally underfunded, used as propaganda machines or simply lack the skills, resources, and government commitments to support data ecosystems.

In an attempt to fill these gaps, companies such as TracFM have used SMS and radio polling to collect opinions from listeners, asking questions such as ���What is your main concern during the coronavirus lockdown?��� The World Bank, IMF, and McKinsey have all put out their own predictions on impact across different sectors. However, private companies, NGOs, and foreign consultants stepping in to measure and guesstimate is insufficient. Data is created, processed, and interpreted under unequal power relations and can reproduce the same oppressive and discriminatory norms that already exist in today���s societies. It���s important to understand the motives behind this data collection by foreign enterprises, to focus on supporting national statistical offices to bolster stronger systems and to ensure trust in the general public around the data in circulation.

African governments have been decisive since the outbreak. Safety net responses across the continent have included tax relief, cash transfers, food distribution, and utility bill freezes. It is understandable that collecting data during a pandemic can be a daunting exercise. However, this data is vital to understand where to prioritize recovery efforts. In the face of major economic losses and depleting tax revenues, how will social safety nets be implemented in a way that protects the most marginalized? Finally, how are governments applying gender-sensitive responses in post-crisis recovery plans���ones that address the structural inequalities that disproportionately impact women. Let���s make sure that these do not end up in the cabinet of missing datasets.

September 2, 2020

Seeking refuge in Sahelian cinema

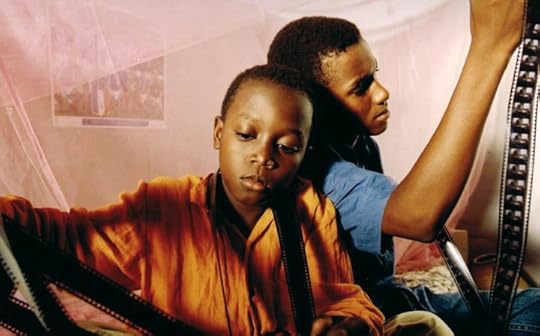

Still from A Screaming Man.

In the midst of a pandemic I���ve found solace in cinema���s Sahelian space of vast isolation, trauma, and a moody depressed tone. There���s something particularly resonating for me about stepping into the frames of Mahamat-Saleh Haroun���s cinema, for instance, as brothers, Tahir (Ahidjo Mahamat Moussa) and Amine (Hamza Moctar Aguid) do in Abouna (Our Father, 2002) as they gaze at the poster of a Mediterranean shoreline whose foamy waters fade into ebbs and flows so that their isolation���like ours���is mitigated by the magic of film.

Since his first feature, Bye Bye Africa (1999), Haroun has remained committed to making films in Chad. ���If I stopped making [films],��� he has declared, ���you would never see images of Chad.��� A landlocked country in north central Africa, Chad is the 20th largest country in the world; more than half of its territory is desert.

Still from Abouna.

Still from Abouna.The Sahel is by definition the expanse that separates the Sahara desert from the savannah. However, Haroun���s noteworthy cinema d���auteur style���a mixed palette of desert hues and vivid yet softened tones, where still frames are overlaid with traveling pans, trilling kora music, and limited dialogue���privileges movement across space. Captured in its fluidity, the Sahel is represented as a transitional and transitory space, as well as one of in-betweenness. Haroun���s films all share the common motif of looming civil war or its aftermath and stories of an absent father. But instead of displaying the violence of war on the screen, he uses the space of the Sahel to provoke thinking about the effects of war, about relationships, love, and history. He never leaves out the politics of African cinema or his deep love for the seventh art. Infusing the fluidity of the Sahel into his aesthetic approach allows Haroun to present these themes with a certain reflective realism and narrative ambiguity.

Perhaps his most stylized film, Abouna reveals the fluidity of the Sahel more than his other works. He accomplishes this through various shot sequences that lead us to question the confinement of the frame. Haroun utilizes the fluid space of the Sahel���its sounds, music, angles, stillness, color palette, lighting; its confined spaces and its movement���to demonstrate the power of cinema as a limitless art.

In the Sahel, people are constantly in movement across space, which Haroun captures using long-take traveling pans, for instance of Adam (Youssouf Djaoro) riding his motorcycle from N���Djamena to Ab��ch�� (almost 500 miles) to find his son Abdel (Diouc Koma), incorporating the same horizontal slow-paced long pan across the still water of the lake when he brings his son���s body back in A Screaming Man (2010). As Grisgris (Souleymane D��m��) swims across the lake, a line of bobbing oil cannisters in tow (Grisgris, 2013), the camera���s closeup wide angle shot captures his movements, just as it does as he zigzags the narrow neighborhood streets.

Still from Bye Bye Africa.

Still from Bye Bye Africa.The Sahelian landscape serves to announce the ambiguity of borders. Even actual borders in Haroun���s films are presented in a way as semi-fluid spaces, as bustling market exchange points, such as the Cameroon/Chad border that brothers Tahir and Amine visit one day in Abouna. Their smallness is framed in a wide pan as they run, play air soccer or walk on their hands across the vast flatness on their journey to and from the border. In hopes of finding their father, the boys��� arrival at the checkpoint is matched with a bustling constant flow of people in a bi-directional cross pattern. ���Over this bridge, you���re already elsewhere,��� Tahir tells Amine. But, curiously, Tahir and Amine do not try to sneak across this border to track their father down, like they do when they run away from a Koranic school. This leads to a question of Haroun���s ambiguous stance toward the construct of the nation as a confined, bordered space; likely it is a comment on migration as well.

We might say that Haroun along with Abderrahmane Sissako are the grand masters of Sahelian style. Sissako���s and Haroun���s films at times echo one another���Haroun himself notes that Abouna is sort of in conversation with Sissako���s Waiting for Happiness, both released in 2002 (Sissako also produced Abouna and Daratt). We see this sort of dialogue between films on visual and sonic planes in the films��� shared emphasis on the desert as transitory space.

For instance, the opening shot sequence of Abouna (Our Father) shows a man���we come to learn he is 15-year-old Tahir and 8-year-old Amine���s father (writer Koulsy Lamko)���walking with a suitcase across the desert. The camera follows him as he nearly disappears in the distant desert horizon then re-centers him in a closeup where he turns slowly and gazes directly into the camera for a moment before turning abruptly then continuing through the sand. Roll opening credits with the accompaniment of melodious guitar picking, the long shot completing the sequence with the small figure advancing further in the distance. Sissako���s opening frames the transitory port town of Nouadhibou, Mauritania, with an establishing shot fixed on a tumbleweed amidst a sandstorm, the sounds of high-speed winds and waves crashing in the distance.

While Haroun was probably thinking of the notion of ���waiting������Abdallah (Mohamed Mahmoud Ould Mohamed), in particular, is waiting for happiness in Sissako���s film, and the boys Tahir and Amine are waiting for their father���s return in Haroun���s���the fluid space of the Sahel is central in both films, as a kind of moving crossroads where people come and go, either to Tangiers in the north or further to try and reach France. But mostly, these films exemplify the fluid space of life in the Sahel.

Still from Grigris.

Still from Grigris.Another shared element is the slow, albeit fluid pacing of the films. The most memorable scene in Sissako���s film La Vie sur terre (Life on Earth) is when the old men move their chairs out of the sun to match the pace of its own slow movement, accented by the flowing soft trills of the kora strings.

In A Screaming Man, several close-up long shots of the protagonist Adam add ambiguity to the reel; the viewer has to work to interpret and understand those silences. Of course, for Haroun, this is deliberate. His last aim is to be a didact. In this and other instances, those long takes of elliptical silence are complex utterances of emotion, which Haroun crafts carefully and thoughtfully.

In Daratt, Atim, whose name means ���orphan,��� journeys to N���Djamena with the sole mission of killing Nassara, the man who killed his father years prior during the war. Atim���s arrival in N���Djamena is signaled through the framing of the large mud wall of Nassara���s bakery and his bread cart; in an elliptical shot sequence, we see Atim cross in front, pause, then cross again in the opposite direction. There are punctuated silences and abbreviated dialogues between Atim and Nassara. This latter himself lost something in the war: his voice box when his throat was slashed, so in order to speak, he needs a prosthetic. Principally for that reason, he chooses his words carefully. Haroun���s camera captures a complex set of emotions, which are ambiguously evoked with few to no words. This aesthetic too is inspired by life in the Sahel. According to Haroun, his characters don���t talk a lot because that is how people are in Chad. ���Against the immensity of the desert,��� he says, ���you feel very small��� you don���t have too much to say.��� (interview 1:12)

Still from A Screaming Man.

Still from A Screaming Man.If Daratt can be considered a fable, its last aim is to moralize. Atim harbors a deep hatred for Nassara, but his hatred is rendered ambivalent in its complexity. His grandfather advises him to take revenge, seek justice after both hear that the Truth and Justice Commission has given blanket asylum to all who killed in the war. Darratt is about unresolved emotions in the aftermath of a war that started in 1965 and has never really ended. Hate in this regard is a complicated emotion. As viewers, we see Atim���s hate and vengeance turn into sadness. He becomes Nassara���s apprentice, and Nassara becomes a sort of father figure to him. Reflecting on his film, Haroun says the essence of Daratt is really that Atim has to decide if he wants to kill (to avenge his father���s murder) and he really only feels free once he knows he is not a killer.

Finally, whereas Haroun���s cinema is deliberately serious���he sees the comedic genre as a luxury���his filmmaking is by no means a somber endeavor. An integral element of Haroun���s poetic brushstrokes are the comedic moments that punctuate his films and make us fall in love with his characters. In Daratt, Atim and A��cha, the baker���s wife, laugh and make fun of Nassara. Abouna has multiple laugh out loud moments throughout the film, such as when the boys��� mother says the father left because he was ���irr��sponsable,��� and Amine���s ingenuous interpretation of the dictionary definition ���Ahh! So, Dad���s not responsible for leaving!��� lightens the mood as the boys carry on. Perhaps the most touching humor of the film comes from the brothers��� camaraderie and playfulness, notable especially in the joke Amine tells his older brother one night as they go to bed: ���Do you know why roosters crow all the time? [���] They don���t want us to hear them farting. Roosters are very proud! Hehehe ha ha ha��� and his laughter carries on, raspy from asthma, as his brother���s reply to the sound of a rooster crowing adds, ���Here���s one that even farts at night!��� causing sustained laughter.

A genuine humor along with soothing music in Haroun���s films adds a certain tenderness to an otherwise deeply solemn tone. Perhaps as we reckon with our human smallness in the vastness of our current global crisis, we can find solace in Sahelian cinema, laughter through our tears, and allow the breaking of freshly baked bread to settle our unresolved emotions.

In the jungles of the Congo

Congo around Makaga Sibiti. Image credit

jbdodane via Flickr CC.

Emerald Labyrinth��is by turns an entertaining and frustrating autobiographical account of an American zoological researcher���s work in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)��in 2008 and 2009.��A herpetologist, Eli��Greenbaum conducted a series of research visits to eastern DRC particularly to research frogs, lizards, and snakes.��It is to Greenbaum���s credit that he was willing to write a book so far removed from his typical audience.��The book assumes the reader has no background in herpetology or Congolese politics.��Greenbaum consciously fits his study in a long history of similar (albeit rather dated) accounts of scientific exploration in Africa.��The ethnocentric legacy of these works is such that twenty-first-century forays in this genre are hard-pressed not to follow well-worn paths of exoticism and exclusions of Congolese knowledge.��This study does put considerable effort to not repeat the flaws of its forebearers, although it is not entirely successful.

The opening chapters provide justifications of his research project. Greenbaum points out that��the dated and very incomplete records left by Belgian colonial researchers are only a foundation for more detailed studies.��He��highlights��the need to document biodiversity and to trace how changes in individual species��� behavior requires much more zoological research in African countries.��Thankfully, Greenbaum also realizes how important Congolese scientists are to this work.��He describes how herpetologist Chifundera Kusamba was a crucial partner throughout the research.��Greenbaum does much better than most of his counterparts in the humanities and social sciences by illustrating the crucial importance of his Congolese assistants beyond rote gestures of gratitude in the acknowledgments section. Chifundera literally manages the entire program.��He regularly negotiated with government authorities, Mai Mai militia leaders, and local communities so that Greenbaum could continue the project.��Greenbaum also recognizes Chifundera as a co-author in his publications, which is much more than can be said for many researchers in the global North.