Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 159

September 15, 2020

The culture wars are a distraction

Photo by Reginald Sebopela on Unsplash

Almost six months ago, South Africa entered into a lockdown to curb the spread of COVID-19. The lockdown is still in place, but back then the restrictions imposed were incredibly severe: no one could leave their home unless to purchase food or medicine, and the now familiar category of ���essential workers��� were the only ones permitted to travel for work. Now that these rules have been lifted, some people are desperate to soak in the warm weather and taste a slice of normality. It���s easy to forget that the implementation of lockdown spelled confusion and disaster for most;�� easier still, to ignore the fact that despite the gradual reduction of reported cases, the economic impacts are only really appearing now, and things are looking grim.

And so, the debacle unfolding last week over retail company Clicks��� use of a racist advert on its website, is the clearest illustration of the erratic consciousness which characterizes South African public life. The advert, selling the American hair care brand TRESemm��, depicted a white woman���s hair as ���fine & flat��� and ���normal��� while a black woman���s hair was described as ���dry & damaged��� plus ���frizzy & dull.��� It goes without saying that the ad is reprehensible, offensive, and deserves the outrage its sparked. Yet, this is not the first thing Clicks has done in the last six months which is objectionable���in April, its workers accused them of forcing them to work without pay. It was also at one stage accused of price gouging, and, it wasn���t the only company implicated���across the board and throughout the lockdown, corporations partook in unfair labor and pricing practices in order to shift the economic burdens of the crisis to workers and consumers. Why did these practices produce little outrage?

The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), South Africa���s third largest party and one officially styling itself as ���Marxist-Leninist-Fanonian��� (they copy the late Hugo Chavez���s Bolivarian movement in their red uniforms), has been leading the moral crusade against Clicks. In doing so they have been incredibly effective, beginning last week with country-wide protests at a range of Clicks stores, and ending it by reaching an agreement with Clicks��� holding company to remove all TRESemm�� products from its stores to be replaced by locally produced ones, as well as to donate 50,000 sanitary pads, sanitizers and masks to rural settlements chosen by the EFF.

These actions marked the return of the EFF to South Africa���s political scene after a long hibernation during most of the lockdown. In its initial stages, the EFF���s most notable call was for people to be quarantined on Robben Island. As it then became apparent that the state���s socio-economic response was lacking, prompting a mass civil-society mobilization to organize food parcels, extend social grants provision and ensure that there was basic support for the poor and vulnerable, the EFF was glaringly absent. But, this is supposed to be South Africa���s working-class party, and much as some on the left have long been disabused of the notion that the working-class is whom they represent, for the most part it���s still believed that the EFF is radical in some meaningful sense.

When the EFF first emerged as a political party in 2013, it was widely cheered as being a viable option to fill the void left in working-class politics in the wake of the Marikana massacre as the ruling African National Congress��� hegemony began to crumble. While the composition of its admirers included a diverse range���disgruntled local businesspeople, university students and the urban unemployed���its militant populist style was touted as left in orientation given its advocacy for policies such as nationalizing South Africa���s mines (which it is no longer that committed to), and land expropriation without compensation. (Two years later, as South Africa���s campuses erupted with #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall, the EFF won SRC elections on many campuses.)

Nowadays, the party has become too loaded with contradictions for it to be considered left-wing in any credible sense, both in its ideology and practice. Besides its lack of internal democracy and the cult of personality surrounding its leader Julius Malema, some of the EFF���s lead figures have been embroiled in various financial scandals including municipal tender fraud and the ransacking of a mutual bank primarily serving informal rural, friendly societies. Throughout its history, the EFF has never had any moorings in the organized working class; it lacks any trade union affiliation (it enjoyed some informal links to the Marikana workers union, AMCU, but it was never formalized), nor does it have any concrete ties to other social movements like those for the unemployed or in mining affected communities. Despite this, it clings vehemently to the rhetoric of class, and proclaims its opposition to capitalism although playing almost no part in trying to build a working class movement in South Africa. How then, are they still venerated by most as progressive, and taken at their word by even their naysayers who believe them to be sincerely anti-capitalist?

What explains this is that the terms of radical politics in the public discourse, have shifted from a materialist, class-rooted mode, to an identity-based, culturalist one, and the EFF have contributed to this shift and are its biggest beneficiary. In South Africa, where race is deeply embedded in everyday thinking and experience, the EFF has capitalized and revived the idea that black people possess a distinctive, social identity, therefore constituting a ���people��� whose political and material interests are uniform. By positing some homogenous ���black interest,��� the EFF is able to flatten the contradictions of its political project, which at this point looks simply like a kind of economic nationalism, less opposed to capitalism per se, and more opposed to the fact that South Africa���s capitalist class continues to be dominated by ���white monopoly capital.��� The EFF���s biggest problem isn���t that capitalism concentrates wealth in the hands of the few, but that this few are predominantly foreign, white or Indian.

In this crucial way, the EFF���s class project is actually just continuous with that of the ruling African National Congress, which since 1999 has been facilitating the rise of a supposedly patriotic, black bourgeoisie whose economic upliftment is meant to be synonymous with the progress of black people as a whole. South Africa���s political class in the main has never parted with this thesis. All that���s really contested, is how swiftly or not this is happening. According to the EFF���along with the Radical Economic Transformation (RET) faction of the ANC, led from the shadows by Malema���s former mentor and former president Jacob Zuma���it is not happening quickly enough. Instead of�� being a serious challenge to the ANC���s apparently declining hegemony, the EFF is more accurately an expression of its resilience. The EFF���s sustained inability to articulate a coherent political identity on its own stems from the simple fact that rather than being fascist (as some proclaim), it simply is just a wandering faction of the ANC, its prodigal son.

Yet, it is Frantz Fanon himself who warns against thinking that this project of establishing a state-led, indigenized capitalism is in any meaningful sense progressive. As he writes in the Wretched of the Earth:

Yet the national bourgeoise never stops calling for the nationalization of the economy and the commercial sector. In its thinking, to nationalize does not mean placing the entire economy at the service of the nation or satisfying all its requirements. To nationalize does not mean organizing the state on the basis of a new program of social relations. For the bourgeoisie, nationalization signifies very precisely the transfer into indigenous hands of privileges inherited from the colonial period.

Even if we could successfully transform the capitalist class so that it was demonstrably black, the underclass to which it is causally connected to, whose deprivation makes possible the other���s wealth, would still be black! Framing inequality primarily as racial disparity misses that it is now actually intra-racial inequality that is contributing more to total inequality. But more importantly, it expresses a fundamentally misplaced concern about the problem. As Adolph Reed Jnr. and Walter Benn Michaels recently wrote, ���What we���re actually saying every time we insist that the basic inequality is between blacks and whites is that only the inequalities we care about are those produced by some form of discrimination���that inequality itself isn���t the problem.���

The racism that was on display in the advert approved and displayed by Clicks is very much present in our society. But, it is not the definitive issue of our time, nor does it have to be for us to give it appropriate concern and attention. In corporate workplaces, university settings, Model-C or private schools and hospitality venues like hotels or restaurants, racial discrimination and prejudice very much persist and must be opposed. But ultimately, these are also (elite) spheres where the majority of the country are excluded from altogether, and the consequences of the struggles for recognition operative in them have little bearing for the lives of most poor, black people.

Racism does have a significant bearing on their lives, but to paraphrase and modify Stuart Hall���s turn of phrase, it is an experience of race lived through the modality of class. Consider how throughout most of the lockdown for example, dangerous stereotypes were peddled about the working class. When an increase of the child support grant was being considered, poor and working black people were often cast as financially irresponsible and bound to use the funds on drugs. When the lockdown began easing and returning workers refused to work in unsafe conditions, they were lazy and selfish. When the alcohol prohibition was lifted, and there were spikes in trauma incidents at hospitals, it was poor and working class people who were blamed. It was the middle class and ruling elite of all races and across the political spectrum that happily took part in this demonization.

As my friend and comrade Awande Buthelezi once eloquently put it to me (channeling Walter Rodney), in post-apartheid South Africa, it���s not so much that people are poor because they���re black, but they are black because they���re poor. What this means is that that the most egregious racialization, that is, literally treating particular groups as possessing characteristics inherent to their nature, happens concomitantly with their particular economic subjugation. What people now often refer to as ���classism��� is actually just racism by another word. The word classism was only popularized to accommodate the false notion that black people couldn���t be racist, not least against their own race���which misses the important point that while race isn���t real, racism definitely is. And to express contempt for working class people, treating them as if they were a cultural identity (an apparently primitive and conservative one at that), and not an objective social relation rooted in political economy, is precisely to engage in racializing them. The basic insight of all this is that racial ideology provides the justification for continued economic exploitation. As the American sociologist Oliver Cromwell Crox explains, ���to justify humanly degrading labor, the exploiters must argue that the workers are innately degraded.”

Why then, are people poor? It���s always been because of capitalism, and at the moment every single opposition force in South Africa treats it as its perennial premise. To borrow a phrase from Karen and Barbara Fields, people treat apartheid as if its chief business was producing white supremacy rather than mining gold, diamonds and platinum. Our society is essentially classist, therefore it is essentially racist. But, what is liquidated in the turn of understanding social cleavages exclusively through identity is the class antagonism which actually grounds the material interests which shape political life���the antagonism between wage labor, capital, and the professional managerial strata in between. In forever using race as a proxy for class, we ignore that race is no longer a reliable predictor for class position, and that this was always bound to become the case in a country where black people are a substantial numerical majority. The interests of black people are not, could not be the same, and to posit them as such is to make possible a public sphere in which actual working class interests are sidelined and ignored. With the public sphere now more or less being entirely the vapid abyss that is social media, a significant portion of the country is excluded from public life; for example, only 53% of South Africans have access to the internet.

The gravity of the issues facing the majority of South Africans such as skyrocketing unemployment, a deepening hunger crisis, water shortages and drought, as well as the crisis of social reproduction which manifests in escalating gender based violence made last week���s debacle feel painfully myopic. South Africans have always known the magnitude of the challenges before us, but what we are still unwilling to admit is that we are in the grips of a global, systemic, and worsening capitalist crisis, not simply seeing through a passing pandemic or set back by temporary issues of governance and state incapacity.�� In the face of all this, the EFF���s actions are nothing more than asking that corporations be woke in their profiteering, leaving production for profit unchallenged as the basic principle of social organization.

No political party in South Africa today presents a credible alternative, not even the Democratic Alliance, the official opposition who recently announced that it was officially adopting a policy of ���non-racialism������which is as laughable as the EFF claiming to be Marxist-Leninist-Fanonian. The DA sits on a pretend moral high ground and professes to be against racial identity politics while being committed to it in practice. This year, the DA has campaigned to have farm murders (of white farmers) be declared a national emergency and categorized as hate crimes, treading not far from the right-wing conspiracies that claim there is a white genocide ongoing in South Africa.�� Rather than accepting, as the evidence shows, that this falls part of the general pattern of violent crime and social disorder and that poor black people are crime���s main victims (a symptom of worsening poverty and inequality), the DA tries to construct some special victimhood for white South Africans, despite remaining firmly wedded to the current economic system.

The culture wars in South Africa are simply a battle for the soul (read race) of the ruling class, the political elite scrambling to be captains of the Titanic while the ship sinks and the world around it burns. It���s all a distraction, and what���s left of the progressive left must ignore it. It is only the working class and its constituent social movements presenting a credible vision for social transformation in the short and long term, emphasizing that the emancipation of the working class is the emancipation of all. That there is a way out���and not merely drifting aimlessly and precariously on a lifeboat trying to survive, but towards a society free of domination and exploitation, one that is truly non-racial and non-sexist.

It is exactly this universalist impulse driving the solutions being put forward by a collection of burgeoning movement coalitions, such as the COVID-19 People���s Coalition, the South African Food Sovereignty Campaign and the Cry of the Xcluded, and include things like introducing a basic income grant for all, to adopting a people���s climate justice charter and green new deal that ends our original sin of mineral extractivism while shielding us from ecological catastrophe. As the old order crumbles, rather than present solutions underpinned by a substantive vision of what constitutes the good society, South Africa���s political class resorts mostly to empty and inane posturing. When our political parties have recourse to the realm of identity and culture, it is a smokescreen for their lack of political legitimacy and programmatic content. It is cynically unpolitical. It���s all bullshit.

And sincerely, there is no time for bullshit. The stakes are too high. The left re-emerging in South Africa must declare unapologetically: no war but class war.

September 14, 2020

After the monuments have been removed

The statue of Louis Faidherbe, a French colonial general in St Louis, Senegal. Image via Pikist.

As interesting and necessary as it may be, it seems to me that the current critique of the presence of colonial symbols in our public spaces needs to be, as of this moment, reexamined.

Let me emphasize ���as of this moment.��� I readily acknowledge that there will be some who believe the time has not yet come for internal criticism of a process that remains incomplete and that has even, in a certain sense, just begun. Is there not, as they say, a time and place for everything? Should we not prioritize certain actions and deeds? Demolish all of the problematic statues first, rename certain spaces, and only then, once we have recovered the feeling (or the illusion) of a sovereign liberty beyond all humiliation, turn our thoughts to other challenges?

This argument is well taken, but I would counter it with another. The problem posed by the presence of colonial symbols in public space is only the visible part of a deeper and more widespread crisis: that of the relationship a people���the Senegalese people in this case���maintains with its so-called symbols. More fundamentally, this is a crisis in the actual knowledge that this people has of the symbols they are exposed to. It is not clear that replacing the current colonial symbols with figures that are judged more authentic will mean that the greater part of the local community will take more interest, identify more clearly, or be more attached to them.

The moment we are currently witnessing does not therefore seem to me to be a simple prelude to a time when our relationship to historic figures will be less problematic. Tragically, this moment has already (or again) tested our true knowledge of our history, and the result is damning. Not only do we not know our own history, but we don���t even really care to know it.

From an ethical perspective, the statue of Faidherbe that still stands imperiously over Saint-Louis presents a definite problem. I am in favor of taking it down from its pedestal and moving it to a place where the painful memory it represents can be brought into the light and reflected upon as lucidly as possible.

But from an epistemological perspective, which is to say from the unique perspective of the knowledge an era produces or possesses about a fact, an event, or a person, this statue poses the same questions that would be posed, in its place, by a statue of Lat-Dior, Ndat�� Yalla or her sister Ndj��mb��tt Mbodj, Aline Sito�� Diatta, or Koli Tenguela.

What do I really know about this person standing on a pedestal, or whose name has been given to this street? Have I really been taught their history? Why are they here? What values and virtues did they possess, that they should serve as inspiration for my own life?

I am not the only one to have asked this question since the debates over Faidherbe���s statue began to rage. How, for all these decades, has this statue stood without anyone really taking an interest in its meaning? Is it because our struggles were focused elsewhere? Because one did not consider this symbol all that important? Because the demands of daily life prevented people from taking the time to wonder why this statue was presented to them? Because we cannot be engaged in all causes with the same intensity? Each of these hypotheses have their element of truth, but there is one, I believe, that should be given more weight than the others, since it encompasses them all in its undeniable obviousness: if we were not so worried about the statue of Faidherbe, it���s because we didn���t really know Faidherbe. Or rather: it���s because what we did know about him, what we had been taught about him, only overlapped every so partially with his sinister deeds and his life.

I do not mean that nobody knew of the horrors committed by Faidherbe, nor do I accuse historians of failing to document the most gruesome aspects of what he did. What I mean is that those who knew this history were a tiny minority (and remain so overall). Unfortunately, the works of academics such as Iba Der Thiam or Abdoulaye Bathily, to mention only the best known, have not been discussed more widely. It is in no way their fault alone. It involves a whole system which has not allowed these works to infuse or penetrate the social fabric so as to leave a more lasting mark. This process has, for multiple reasons, failed. The knowledge that it was meant to convey has not successfully moved beyond a circle of initiates to the moment when one sews the first crucial seeds of knowledge: childhood.

The memories I have of Faidherbe from primary school���and Lord knows I had some excellent teachers, admirably cultured and pedagogically well-trained���vaguely involve a man who ���pacified��� a specific territory and ���repelled the attacks��� of some invader or other who attempted to conquer or break up the country. And perhaps he did; but he also did other things. These other things, these terrible other things, took me years to discover. Until then, I spent several years in Saint-Louis and I passed by Faidherbe���s statue hundreds of times without paying it any attention.

This is my point: as far as symbols are concerned, though it could also be said of anything else, the more specific knowledge we have, the better we are able to reflect and react emotionally. This, in turn, defines our collective and individual relationships with the figure in question. As long as this knowledge continues to be mutilated, embellished, distorted, poorly taught (I would say not taught at all), apocryphal, or even mythologized, we can place any figure we like on a pedestal and most of the population will remain indifferent. What is happening in this moment is a welcome opportunity to open a deeper debate about: the knowledge we possess about the major figures of our history (Faidherbe is but one of them); the manner by which this knowledge is adapted, communicated, digested, and reformulated so that it can be transmitted to the public; and the relation that the masses have with the very idea of using symbols in public spaces. (I use the term ���masses��� here with no contempt, to refer to those who have not always had the opportunity to go to school and who, either geographically or mentally, live far away from big intellectual debates held in French about collective memory).

Make no mistake, I do not consider Faidherbe the same as, let���s say, Aline Sito�� Diatta. However, I do hope that the second, if she ever finds herself on a pedestal one day, is not reduced to a few vague details and then gradually condemned to a general indifference broken�� only by periodic insights into her life, by quarrels among specialists about this or that episode in her biography, or by some forced tribute.

I also hope that the current debate can avoid seeing these problems only through the lens of colonialism���with all the polemical, emotional, and ideological baggage that comes with it. It would be hypocritical to say, on the one hand, that we are reclaiming the entire history of our country while systematically relating all of our debates about this history back to the colonial enterprise, as if nothing else existed outside of it.

Finally, I would hope that the current movements to take down old statues arrive at some end other than noisy and hollow symbolism. Overloading symbols with ideology or power with no concern for their impact on our collective situation would make no sense. The ideological pride of renaming a university after one of our own eminent scholars (Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar) remains vain and superficial if, within this university, one is concerned with everything except knowledge for its own sake and the quest for truth. Naming a street after a courageous female figure drawn from our own history is an empty act if, on this street and on plenty of others, a woman���s dignity can be violated by men at any moment and in any way (including the most vile).

I will conclude with a more general and open reflection on historic figures, be they colonial or Senegalese. Perhaps, most fundamentally, it is the act of ���statue-fying��� a human being that poses a problem today. As we know, a certain number of ���great men��� in our history were also ruthless conquerors who massacred other peoples, or they were notorious slavers, or schemers who, by allying themselves with colonists for strategic reasons, betrayed their alliances with ���their own people��� without hesitation. If we begin with the premise that most historic figures were not perfect or pure, and if we acknowledge that some of those whom we take for heroes are seen as executioners or ���traitors��� elsewhere, perhaps not too far away, how do we justify building a statue to their glory or giving their name to particular spaces? What are the criteria for promoting certain figures from Senegalese history to the rank of national symbols when we know at what cost their achieved their greatness?

I don���t have the answer���and perhaps I am not even asking the right questions. Nevertheless, I remain convinced that the events put into motion over the last few weeks will soon surpass the framework of colonialism, which can both inform the debate or simplify it down to less useful binary ways of thinking. The question will then no longer be whether there is support for or opposition to Faidherbe���s statue in the street���this opposition alone is insufficient and unproductive���it will be whether we can discover, through Faidherbe, the meaning and background of all the symbols in our public spaces and in our history.

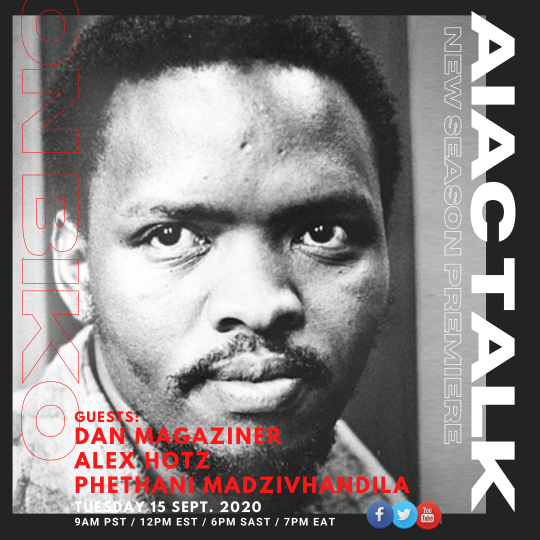

Introducing ‘AIAC Talk’

After a brief publishing break, Africa Is a Country is back and proud to announce the launch of AIAC Talk! Premiering this Tuesday, and streaming every Tuesday thereafter, co-hosts Sean Jacobs and Will Shoki and a revolving cast of guests will take an hour-long look,��from the left, at the most pressing issues facing the continent today.

Produced from Cape Town by Antoinette Engel, our first official episode streams this Tuesday, September 15th, at 12:00 EST and 18:00 SAST on Youtube, Twitter and Facebook.

If you want to download the show or listen to it on your podcast app, we are also happy to announce that as a reward for subscribing to our newly minted Patreon page, you can have access to the entire AIAC Talk archive and to a private RSS podcast feed, which will include all the shows from our pilot season.

The inaugural show coincides with the anniversary of a dark period in South African history, Black September, and yesterday, September 12th, marked the anniversary of the day that Biko, arguably most exciting leader of his time, was murdered by apartheid police in 1977. Biko���s ideas have continued to resonate long past his death, and have especially shaped the convictions of the new generation of activists emerging from #feesmustfall to #blacklivesmatter. So our first episode will focus on his legacy.

We will interview historian Dan Magaziner (from Yale University and an editorial board member of Africa Is a Country). Magaziner wrote the book, The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968-1977. We will also be joined by two young South African activists and thinkers of the current generation to talk about what Biko means today: pan-Africanist historian Phethani Madzivhandila and University of Cape Town student activist Alex Hotz.

The violence in Ethiopia

Photo by Gift Habeshaw on Unsplash.

The deadly violence that rocked Ethiopia this summer following the death of artist Hachalu Hundessa has been a subject of much speculation and contention. The facts as we know them are that immediately following the assassination close to 250 people died and thousands were jailed, mostly in the regional state of Oromia and Addis Ababa. What is contested, and less clear, is the nature of the violence, its perpetrators, and victims. Two prominent narratives have emerged following the crisis to explain what unfolded. One holds that the violence was a brutal government crackdown on Oromo protesters grieving Hundessa���s death. The other describes the events as targeted attacks by armed Oromo youth against ethnic and religious minorities. While both narratives contain elements of truth, ignoring one or the other is either ignorant or intentionally misleading.

A recent Africa Is a Country article highlighting the poor coverage by Western media of the situation in Ethiopia, for example, makes no mention of ethnic and religious violence, aside from denouncing media outlets that reported it. Rather, the author���s objective is to ���set the record straight��� by showing that the underlying cause of violence and instability in Ethiopia is the consequence of a political struggle between an oppressive government and Oromos who have been and continue to be marginalized. Such a viewpoint is erroneous and polarizing in the current political climate. To advance a narrow agenda, it glosses over human rights violations and the brutal killing of innocent bystanders by non-state actors.

To provide more context, the agenda I speak of is tied to the Oromo struggle for greater autonomy and recognition. That struggle, which paved the way for Abiy Ahmed to assume power as the first Oromo Prime Minister two years earlier, now seeks his departure. At the heart of this reversal is the Prime Minister���s consolidation (rather than actual dismantling) of the ruling ethnic-based EPRDF coalition into the Prosperity Party, which has, nonetheless, left intact Ethiopia���s unique system of federalism based on ethnic majoritarianism. Leaving that aside, the EPRDF had always been a highly centralized institution in practice, and the mere symbolism of this move, in addition to the Prime Minister���s rhetoric about unity, have left some Oromos feeling betrayed. Furthermore, fractionalization among Oromo elites, including within the former Oromo Democratic Party (ODP) faction of the EPRDF (now Prosperity Party), which recently ousted key leader and Defense Minister, Lemma Megersa, has divided and weakened the movement.

Within this broad movement, one vocal part led by diaspora-based Oromo elites and recent returnees has galvanized the energy and anger of many Oromo youth behind a perspective of anti-Ethiopiawinet (anti-Ethiopian-ness). The ���us versus them��� mentality pits Oromo nationalists against an enemy that has been described manifestly and repeatedly by the terms Abyssinian and Neftegna (���rifle bearer���). Though prominent Oromo activists stand behind their use of these terms, those who are familiar with the context know that these labels are loaded with ethnic connotations.

The night of Hachalu Hundessa���s murder, the Ethiopian government quickly shut down the internet, while a social media whirlwind erupted abroad as Oromo activists insinuated that Hundessa was killed because of his support for the Oromo cause. Accusations that ���they killed him��� were recklessly thrown around and left open for interpretation. Within hours of the assassination, allegedly at the behest of Oromo leaders like Bekele Gerba, targeted attacks against non-Oromos unfolded. In towns like Shashamene and Dera in the Oromia region, several accounts of killings and looting targeting Amharas and other minorities by Oromo youth have been independently verified, in addition to accounts of police and federal forces injuring and killing civilians. Witnesses describe how perpetrators relied on lists detailing the residences and properties of non-Oromos and circulated flyers warning bystanders to not help those being targeted (or risk reprisal), indicating a significant level of organization.�� Minority Rights Group International, accordingly, sounded the alarm, warning that these actions bear the hallmarks of ethnic cleansing. Despite this and concerns from Ethiopians throughout the world, Oromo activists and other prominent human rights groups, such as Amnesty International, have remained largely silent about these attacks while condemning the government���s violent response to Oromo protestors.

Government figures provide an ethnic breakdown of the July causalities with the majority of those killed being Oromos within the Oromia region, followed by Amharas and other smaller ethnic groups.�� Yet, rather than disproving, as some claim, that targeted attacks by Oromo mobs occurred, this highlights what scholar Terje Ostebo describes as the complexity and inherent interconnectedness between ethnicity and religion within Ethiopia.�� According to Ostebo, ���the term Amhara, which is inherently elastic, has over the last few years gradually moved from being a designation for Ethiopianess to gaining a more explicit ethnic connotation. It has, however, always had a distinct religious dimension, representing a Christian.��� Hence, in parts of Oromia some Orthodox Oromos were referred to and referred to themselves as Amhara. For example, one Oromo farmer interviewed by local journalists reportedly said, ���we thought Hachalu was Oromo��� after watching the singer���s televised funeral rites that followed the traditions of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo church.�� According to investigations undertaken by the church, a large number of its parishioners (at least 67 confirmed cases) were among the July causalities���a troubling trend, which also includes a spate of church burnings and attacks on Christians that brought large numbers of Orthodox followers out into the streets in protests last year.

To be clear, the violence that occurred was not only ethnic and religious violence. Growing state violence in Oromia and SNNPR has been and continues to be of great concern. As Oromo activists have made clear, it is necessary to end the abuse of force and ensure accountability for these crimes. Yet, when concerns and demands for accountability for non-state violence are raised, these same advocates deny, ignore or dismiss them as part of a propaganda campaign to discredit the Oromo movement. In effect, this dishonesty, itself, has discredited the movement and lost it support by many Ethiopians���both non-Oromo and Oromo.

The recent political turmoil lays bare that the future of an Ethiopian state is hanging by a delicate thread. The polarization that exists today goes beyond disagreements on institutions and policies to the very question of whether we can continue to co-exist as a multi-ethnic nation. Regional elections in Tigray, slated for this week despite the disapproval of the national House of Federation (HoF), and its aftermath may bring these tensions to a boil, again. As unrest, violence and grievances continue to mount, it is clear that Ethiopia is far from consolidating its transition to a stable democracy. The government continues to curb freedom of speech, jail political opponents and is responsible for violence against civilians. But, if history teaches us anything, it is this: the imminent and existential danger to Ethiopia is not Abiy Ahmed and an oppressive government. It is violent ethno-nationalism.

September 11, 2020

What Chinese people eat

Image via Pikist.com

The consumption of “unacceptable” animals in China has been popularized as the cause of COVID-19, placing this virus in a parallel zoonotic racialized lineage to that claimed for Ebola, and often even AIDS. But the West, whilst disparaging consumers in “wet markets” and of “bush meat,” engage in their own consumption of “unacceptable” animals, laying evident the contradictions in COVID-19 reportage and ostensive conservation practices. This post, originally published by The Elephant, is part of a series curated by Editorial Board member, Wangui Kimari.

In pre-colonial Africa, before the Berlin conference that led to the ���Scramble for Africa��� among European countries and the subsequent creation of arbitrary territorial boundaries we now refer to as countries, ���states��� were defined by some form of shared heritage, not just in the form of hard tangible artefacts, but in culture���practices and knowledge that are acquired by peoples in situ. When populations moved, they carried this heritage with them and adjusted it to fit in with the new realities they encountered in their new homelands.

The current crisis precipitated by the COVID-19 global pandemic has severely restricted travel for recreation and business and the sharing of experiences and ideas across the world. In a manner of speaking, it has put globalisation on ���pause��� as countries must look inwards for ways to mitigate its impact on health, social, and economic systems.

The complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic lies in the fact that there is still no universally accepted approach to its mitigation or management. Individual countries have, therefore, been compelled to draw on their own intellectual and material resources to address the impact of the pandemic, with varying levels of success. Some countries have taken a reactionary approach, while others struggle to find direction, illustrating the need for us to retake control of our living heritage and re-imagine ourselves in the light of our own needs and aspirations.

Double standards

The true origins of this pandemic may never be known, so those of us who are lay people take what the media give us. The spectre of a zoonosis ���jumping��� from wild animals into humans through the consumption of their meat and the sheer speed of communication (or mis-communication) about this are among the most startling features of this pandemic.

When the pandemic started, the media were instantly awash with (frankly revolting) images of people of Asian descent eating whole bats in soup. Suddenly, newly-used terms like ���wet markets��� were de rigueur in news bulletins, as were images of Chinese markets with live and dead creatures of all kinds for sale, either whole, live, or in various stages of dismemberment. It was only a matter of time before the racist dog-whistle ���bush meat trade��� hit the airwaves (nauseatingly familiar to those of us who work in the conservation sector).

I have often spoken about how the portrayal of the consumption of wild animals is one of the most overt and widely accepted expressions of racial prejudice in our times. It has long been an accepted norm that the meat of wild animals must be described in genteel terms when it is consumed by white people, as is the killing of all manner of creatures. The nature of conservation discourse has normalised the use of the different terms ���game meat��� and ���bush meat��� even to describe consumption of flesh from the same animal species, based on the ethnicity of the procurer. Slaughter is routinely described as ���sport��� and dignified as ������noble��� all over the world when perpetrated by white people, and occasionally elites of colour. After 20 years as a conservation practitioner, I am familiar with the cult-like manner in which we pursue the cause. It is considered above reproach, and all manner of ills can be visited upon human societies as long as they can be demonstrated to be serving some environmental conservation goal.

It was, therefore, a feeling of d��j�� vu when the tone taken by the Western media portrayed the outbreak almost as some kind of ���divine retribution��� visited upon the Chinese people for the consumption of meat from wild animals. (This was before the virus spread globally and stopped being regarded as a Chinese problem.) Indeed, scientists were falling over themselves to look for coronaviruses in all manner of trafficked animals, like pangolins. Racial undertones have always been part of global conservation practice, and that is the reason why Europe and the United States have largely escaped the opprobrium that has been visited on China for the ivory trade, despite it being third globally behind the former two in this vice.

When wildlife is used as food in the global South and East, it draws near universal revulsion in the West with regards to the ���cruelty��� of the activity. Those who have visited the United States, however, are familiar with the seasonal hunting and eating of deer, elk, moose, squirrels, opossum and rabbits, not to mention turkeys, ducks, and other wild birds.

Those who are so irked by ���wet markets��� would do well to familiarise themselves with the ���rattlesnake roundup���, an annual activity in the state of Texas in the United States. The roundup is a display of extraordinary cruelty where thousands of rattlesnakes are collected from the wild, mostly by being flushed out of their dens with petrol. It takes around two weeks to collect the required number of snakes for the festival, during which time the captive reptiles are kept in the dark without food or water. Come the weekend of the festival, the entertainment of visitors will include the ritual decapitation of snakes and the participants (including children) competing to strip skins off the still writhing snake bodies and flaying them for meat (which is served on site and consumed with a variety of drinks). Children also engage in making murals from hand prints in snake blood, amongst other activities.

A close observation of the reportage on this reveals the degree of effort put into ���cleansing��� this strange ritual, notably its description as a ���celebration of culture��� that brings in $8.4 million into the town of Sweetwater, Texas. The scale of the carnage hit a record high in 2016 when 11 tonnes (24,262 pounds) of rattlesnakes were reportedly harvested. The reporting didn���t specify that this represented around 10,000 snakes (calculation made from the average weight of a rattlesnake).

How then does the Western media contrive to maintain this critical focus on ���unacceptable��� animal consumption practices in the global South while maintaining studious silence on the same in their own countries? What then is a ���wet market���? Can the Texas rattlesnake roundup be described as such, and if not, why not?

Characterising the consumption of reptiles, rodents, chiroptera (bats), marsupials (opossums) as ���Asian��� traits is simply racial prejudice. Similarly, the capture, caging and sale of wild animals in Asian markets is described as cruel whereas sport hunting, whaling, and foxhunting by Caucasian peoplesare accepted, celebrated, and even defended robustly, when need be.

Conservation, tourism and dietary tastes

Personally, as an individual with very conservative (some might say pedestrian) tastes in food, travelling is full of challenges in terms of foods that I encounter around the world. I remember particularly an incident of a Maasai colleague being perturbed by a dinner offering of ���venison��� at a lodge in rural Quebec in Canada. I had to clarify to him that venison is deer meat.

The Maasai are traditionally livestock producers and are known to frown upon the consumption of meat from wild animals. But this was a relatively mild challenge for him, compared to various raw meats, raw fish, marine crustaceans, and snails that he and I have encountered on our travels to different continents.

The variety of dietary tastes and preferences around the world are one of the most prominent indicators of human diversity, and have long been celebrated and studied by travelers and scholars. This pandemic, however, has upset the genteel veneer with which we present our differences and has left our class, racial, and cultural prejudices ruthlessly exposed. If indeed the slaughter of wildlife is a vile aspect of human nature, then why is Theodore Roosevelt���s 1909 hunting safari in Kenya so celebrated by a conservation body (The Smithsonian Institution) over a century later? This expedition was a bloodbath, where the hunters killed and trapped more than 11,000 animals, including multiple specimens of the ���big game��� species that Roosevelt took particular pleasure in killing.

Conservation and tourism have long been an arena that struggles with racism and classism, and my country Kenya has for the last 100 years been the poster child for what is good and wrong about the nexus of conservation and tourism in Africa. Due to travel bans and lockdowns, tourism in the country has largely collapsed. The obsession with foreign tourists (referred to lovingly as ���arrivals���) has left established facilities struggling to appeal to indigenous and local clients for whom they had very little time under normal circumstances.

The real tragedy, however, is in the wildlife conservancies, where conservation NGOs had been going out of their way to convince and coerce previously resilient pastoralist communities to spurn their livelihoods and identities (that were based upon livestock production) and to share landscapes with wildlife. The narrative was that livestock was bad and their numbers had to be suppressed. The landscape didn���t belong to the people, but to the wildlife, and the wildlife had no intrinsic cultural value. It was for tourists, and pastoralists��� livelihoods would reside in service to the tourists.

To be a ���good��� (read: compliant) community worthy of handouts, the community needed to move to the periphery of their lands, leaving the best parts for tourism They had to reduce their herds (or move them away to go and overgraze someone else���s turf), and learn to serve (be a waiter, ranger, cook, or beadwork maker) at the altar of tourism.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, reports from community conservancies invariably feature penury���communities struggling to make a living and depending on food handouts, all due to the collapse of tourism. For those who understand the livestock economy, pastoralist communities depending on food handouts is unthinkable in a year that has seen such abundance of rainfall and pasture growth. The conservation cult had succeeded in compromising the resilience of entire communities.

The language of environmentalism and assistance

Students of political history will experience d��j�� vu; 200 years after its initial foray, Western neoliberalism is once again bringing rural Africa to its knees by destroying resilience and creating dependency. The only difference is that this time it is hidden in the language of environmentalism and assistance.

The world today needs to wake up to the threat to social stability posed by the global environmental movement fashioned in the West. The pursuit of its goals is relentless, and has the hallmarks of a cult. Nonagenarian Westerners like Sir David Attenborough routinely prescribe future goals to young populations in the global South (backed by environmental cinema that deliberately excludes human populations from the frame). As our youth struggle with the visions of old Westerners, our leaders are confronted with advice and ���guidance��� from a European teenage girl, delivered with the glib assurance of someone who doesn���t have anywhere near the amount of knowledge required to confer a modicum of self-doubt.

As African students of environmental sciences strive to make their voices heard in academia, they get confronted by ludicrous theories like the half-earth theory, proposed by E. O. Wilson, a pioneer of ecology from Harvard University, one of the pinnacles of academia. This theory proposes that half the earth should be ���protected��� for the survival of biodiversity.

However, what proponents of this theory don���t state is that this biodiversity will be protected mostly in the tropics, because the temperate lands do not have biodiversity worth protecting in such a drastic manner. Any attempt to actualise such a move would amount to genocide, but the world routinely accepts such fascism when environmental reasons are used to support it.

Indeed, the United Nations and other global bodies like the Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD) have taken up the cause, proposing to raise the recommended percentage of land under protection, from the current 14 per cent to 30 per cent. The voices pushing this movement are varied, but two uniformities persist���the voices are of white people and they say nothing about the difference in consumption patterns between themselves and the global South.

So-called ���global��� environmental targets must be tailored to meet the needs and aspirations of individual nations, or we run the risk of imperialism. Yellowstone National Park was created by violence and disenfranchisement, but it is still used as a template for fortress conservation over a century later, and celebrated as a world heritage site.

For generations, our consumption patterns have never been spoken about globally, because to do so would be to acknowledge that we in the global South have always been sustainable societies. Logic dictates that our consumption patterns shouldn���t now be used to vilify us as the source of a scourge, which strangely appears not to have affected us in the way the global North expected.

The term ���new normal��� has been bandied about ad nauseam to describe the post-COVID19 world. In reality, the manner in which the people and the environment of the global South have been exploited by the Occident over generations has been abnormal. The coronavirus crisis may have just set a few things right.

September 10, 2020

Sadio Man��, made outside Africa

Still from Made in Senegal.

This series of posts is based on a Sports Africa Live Round Table held on May 2, 2020 about the documentary film, Sadio Man��, Made in Senegal. The panelists were sports scholars Simon Adetona, Akindes Peter Alegi, Tarminder Kaur, and Ousmane S��ne, from the West Africa Research Center (WARC) in Dakar. Martha Saavedra (University of California, Berkeley) acted as moderator. Prof. Ousmane S��ne (UCAD) was a panelist but did not submit written text. His remarks, however, are featured in the YouTube video recording of the event, as are Martha Saavedra���s comments as panel moderator.

Sadio Man�� was made in Senegal but he was also made outside Senegal. Born and raised in the remote Senegalese village of Bambali, Man�� did internalize some of the values cultivated and promoted in villages across Africa: respect for family and elders, gratitude, humility, generosity and sense of collective responsibility. These values are amply exhibited in his actions: his assertion ���When I am in Senegal, I am never alone. We live as a community��� resonates with me. I am not romanticizing village life, but cooking, eating, working, playing, and doing other things together are still common behaviors, with regional nuances. This community spirit might also imply that since he left Senegal for a career as a professional footballer (with stops in Metz, Salzburg, Southampton, and now Liverpool) he has primarily lived in more individualistic societies in Europe, where practices of neighborliness, family, and friendship differ.

In the new documentary film, Sadio Man��: Made in Senegal, an indefectible spirit of hospitality, transactional and reciprocal, between extended family, the Muslim community and himself is demonstrated wherever Man�� goes, in Dakar or his hometown Bambali. In Senegal, this fa��on d�����tre, in public and private spaces, is known as teranga, a wolof term and concept to signify a welcoming character, friendliness, solidarity, togetherness, and mutual understanding. This concept has been branded by Senegalese tourism authorities to symbolize Senegal where food, tourism, and even corporations name themselves after the term to consolidate their identities and polish their images.

Man�����s humility, respect for self and others, and his altruistic values are pure products of his village and Muslim upbringing. In Bambali, an individual is not bigger than the collective and giving back or passing goodness on is a societal norm. His uncle, a simple farmer, supported his passion and took care of him in his adolescence. Now Man��, out of gratitude, rewards him with a house and a transportation business.

An umbilical cord connects Man�� to his people and to Senegal as a whole, a country which has yet to win the Africa Cup of Nations (they���ve appeared in two finals; 2002 and 2019) despite having produced high caliber, world-famous players prior to the Man�� generation, such as Boubacar Sarr, Oumar Gueye S��ne, Christophe Sagna, Aliou Ciss��, Jules Bocande, Yatma Diop, and El-Hadji Diouf. (Other footballers born in Senegal like Patrick Vieira and Patrice Evra have represented France.) Man�� captains the Senegalese team, which roots him firmly in the national psyche. He is the ultimate symbol of Bambali pride, but also of national identity. As his Liverpool teammates observe, Man�� is hardworking, laser-focused on success, performance, and winning; values that capitalism loves for its hegemonic narratives, and values that most Senegalese need to survive. Liverpool���s sponsor, sports equipment manufacturer New Balance (they produced the film), is aware millions are watching and following him. Therefore, Man�� naturally fits the role model narrative, a subtle and circumvented way of admonishing ���If you���re failing, it���s because you���re not doing like me.���

Man�����s mother, Satou, appears onscreen twice: first, fleetingly in a phone call that lasts twenty-five seconds, and the second time in a quick scene where he has another phone conversation with her. The mother figure occupies a central place in African athletes��� lives and they profusely praise them, but it surprisingly not the case with Man��. She does not even feature in a third-person story. Man�� has mentioned his mother in other interviews, but often to indicate how she disagreed with his passion for football, and how she was so emotional that she would not watch his games. Also absent from the film are Man�����s brothers and sisters. All of them have been eclipsed by the uncle who facilitated his making it outside of Senegal.

But how was Man�� made outside Africa? First, he took advantage of an outward-oriented channel, the football academy Generation Foot, from Dakar to the French Ligue 1 Club Metz. African players have followed similar paths since imperial conquest. This process of ���muscle extractivism��� empties Africa of its promising stars and leaves behind a football structure that cannot fulfill the minimum aspirations of players and other involved in the game. More than 525 Senegalese players are currently plying their trade outside of Senegal, and in the years 2018-2019, more than 203 players have left Senegal. This phenomenon favors local and foreign-based football elites and officials, and politicians who cash in on such success, neglecting the rest and leaving in its trails an inadequate and unorganized football structure. Man�� acknowledges that ���many skillful players I played with did not get the chance to become a professional.��� One should wonder what happened to both the skilled and the average players who dreamt like him? Narratives such as Man�����s hide and even silence the stories of the vast majority who are unsuccessful.

Second, the film does not provide any information about the football academy ecosystem in Senegal, even though G��n��ration Foot has a partnership agreement with Metz that finances the academy���s operations in exchange for the rights to recruit the best talent and take the young men to France. Man�� spent six months at G��n��ration Foot before being ���discovered��� and its director, Mady Tour��, proudly states in the film that ���my objective is to bring as many players as possible to Europe.���

Third, the film indirectly raises the question of the utility of Man�����s model of building a school and a hospital for the community. To what extent will these structures help Bambali solve their economic and social problems in the long term? Can his model be widely emulated? Can it reduce the gap between Bambali and Dakar, between urban and rural areas? I doubt the model will create a viable football industry in Senegal. Can Senegalese football develop through charity? Furthermore, a few important stories are missing from the film: the role of marabouts, especially in Casamance where African spiritual beliefs and practices are strong; political tensions (Casamance has experienced an independence-seeking rebellion since 1982); racial experiences in European football, and how Senegal ���makes��� its players.

Sadio Man��, Made in Senegal is a beautiful commercial, well crafted, and very incomplete story, built around a t-shirt wearing, humble Sadio, with flashbacks into his past, from Bambali to Liverpool. However, the story perpetuates a perennial, powerful, enduring illusion: one has to get out of Senegal and Africa to make it. It is an illusion that, with other factors, stifles the growth of local sports (not just soccer) and the blossoming of different football styles and identities. It contributes to the standardization of football, reducing it to the measurable outcome of winning and the production of statistical data. With about half the documentary focused on Man�����s prowess and achievements in Europe, the most powerful message of the movie could just as much be ���Sadio Man��, made outside Africa.���

Sadio Mane is a Senegalese (Fairtrade) brand

Still from Made in Senegal.

This series of posts is based on a Sports Africa Live Round Table held on May 2, 2020 about the documentary film, Sadio Man��, Made in Senegal. The panelists were sports scholars Simon Adetona, Akindes Peter Alegi, Tarminder Kaur, and Ousmane S��ne, from the West Africa Research Center (WARC) in Dakar. Martha Saavedra (University of California, Berkeley) acted as moderator. Prof. Ousmane S��ne (UCAD) was a panelist but did not submit written text. His remarks, however, are featured in the YouTube video recording of the event, as are Martha Saavedra���s comments as panel moderator.

Here���s what we learn from the documentary film Sadio Man��: Made in Senegal: Sadio Man�� is a footballer of exceptional caliber; professional football is among the most fetishized entertainment industries of our times; and popular sports-talk relies on clich��s and therefore requires more than literal translation to understand the conveyed sentiment.

Sadio Man��: Made in Senegal tells the story of a child, whose seemingly impossible dream comes true in the most spectacular of ways. It is a real-life fairy tale. It narrates the life and making of one of the most successful professional footballers of recent times, largely in his own words. The title, Made in Senegal, also conveys SMan�� as a product���an export product in the most fetishized industry of the contemporary world. His net worth is about US$20 million, and he takes home a weekly salary of US$121,000. But he is not merely an export product. He is a brand, an African, a Senegalese brand. Sadio Man�� is an export brand, finest of the kind, made in Senegal.

The documentary presents Man�� almost as a ���fairtrade brand.��� There is ample evidence to support the argument that professional sport operates like an entertainment industry and professional athletes are not just labor, but products, bought and sold in their respective sports markets. What Man�����s story tells us about him as a football product or brand is that this global transaction���a talented footballer extracted from Africa, exported to Europe��� is done in the fairest of manners. Labor is rewarding and rewarded, not just in material terms, but in appreciation and honor. While it is important to bear in mind the exceptional quality of this brand, this ���fairtrade footballer��� goes beyond individual success and prosperity. His success has direct material benefits to the village he was once extracted from.

Football fans across the planet are likely to be aware, and in awe, of the quality that the Man�� brand produces on the field. The documentary introduces us to the man behind the brand. We learn about the dreamer, the professional, and the person, who is negotiating the incongruent worlds of extreme inequality at the height of his success. Observing the loud celebrations of his football achievements in the streets of Dakar, Man�� reflects: ���It���s an extraordinary moment. You see people suffering, singing, dancing���When you see these kinds of people and all the offerings in front of the house, you think, ���Wow! I have to work even harder for them.��� ���

There is an ambivalence in this reflection that expresses both familiarity with and disconnection from the everyday sufferings of the Senegalese. And what does he do with this ambivalence? He redirects it to his football: ���I have to work even harder for them.��� This is the moment in the documentary that beautifully situates football in the larger human drama, which takes place both in and out of Senegal. To this end, I agree with Simon Akindes, Sadio Man�� is both made in and out of Senegal.

Still, to really hear Sadio Man��, the person, requires turning down the noises and the cheers of celebration, as well as the clich��s that connect dreams to success. It is then that you hear a child, a dreamer, who is so human, so relatable, and yet so unrelatable, so unreachably impressive, in his football artistry. I wish there was more footage of Man�� playing football in the film. It would have reminded us that we are listening to not just a humble man sharing his journey to success and what he does with it, but to an exceptional athlete, among the finest the world has seen in years. And the two are inseparable. Still, we do get his excellence described by others. For example, Olivier Perrin, the man who ���discovered��� Man�� (in Man�����s own words), shares his earliest impression of watching Man�� play at a game in Senegal: ���When I arrived he intercepted a ball in the penalty area and proceeded down the entire field before making the decisive pass to the guy who scored. It almost looked like���a video game. It wasn���t normal.���

A video game?! From all that I know of watching Man�� play, I would have called it a work of art���a dream performance that one practices over and over in imagination that never quite gets corporealized, except, of course, by the likes of Man��. He challenges us to dream even bigger, before he makes it a physical reality performed on the football field. Adjectives like ���abnormal���, ���crazy���, ���insane���, ���unbelievable���, ���impossible���, are used to describe the exceptional ability of Man��. It is not his football facility, but the simplicity with which Man�� describes ���the worst day of [his] life��� that brings us closest to the child in him and the footballer in every child.

Throughout the documentary, he refers to dreaming of becoming a footballer. Already in the opening scene, we hear him say: ���All I ever wanted to be is a footballer!��� As the film unfolds, we get more detail about what becoming a footballer means to him. At first, a lot of this sounds like clich��: ���You���ve a dream in life. My dream is to write history and win all the trophies. It���s a dream of a child, of course.���

Of course, it is a child���s dream. All the many football-mad children I have come to know would say just the same���they want to become professional footballers! They want to win all the trophies! And many of those dreams take on elaborate and sometimes very practical versions���from paying me back for my petrol as I give them a ride to the field to all that they might do or bring to their villages, once they become champions.

But here���s the rub: Man�����s commentary in the film is illuminating his childhood dreams with the benefit of hindsight, after he has actually achieved the ���impossible.��� His on-field performance may well inspire many more to dream, but dreams only go as far as an individual���s talent for a sport allows. If dreams are socially constructed, conviction is socially affirmed. Even before stepping out of Bambali, his home village, he ���was considered the best player in the village, in the region, even.��� Man�� had people in his remote village affirming the exceptional football unfolding in front of their eyes. His best friend, Luc Djiboune, shares: ���Sadio, like Ronaldinho, but also El-Hadji Diouf, who really spurred us on to play football. He told me: One day I���ll be at their level.��� Later, Man�� himself declares: ���I was 100% convinced that once I left the village I could become a footballer. The only question was: How? That���s what I dreamt about.��� His wizardry gets its first exposure at the Generation Foot (GF), the largest football training centre in Dakar, where Man�� arrives in 2009, at 17 years of age. Man�� spends about six months at GF and before his 19th birthday, he arrives in France as an intern with FC Metz. Reflecting back on his early games with FC Metz in 2011, Perrin exclaims: ���He really played football like the greats.��� Apart from an early injury that could have cost him this opportunity, Man�� swiftly moves towards his stardom, leaving everyone in awe.

His football career progresses swiftly: from his first try-out at the GF in 2009 to FC Metz, then Salzburg FC, then Southampton FC, and finally to Liverpool FC and lifting the Champions League trophy in 2019; it cannot get better. I would argue that Man�� is a prodigy���a wunderkind���not just a dreamer. While this point is only suggestive, not explicit, it is important to be reminded that his success was not simply because he was able to dream big, he was showing signs of his exceptional talent at an early age and was determined enough to follow through on them.

His story is also a fairtrade story, in which his labor is fairly and competitively rewarded, free of dodgy agents or exploitative conditions for an African migrant. We are told a story in which his on-field heroism is based on his merit alone. And just as Peter Alegi draws our attention to ���a white man serving a black man��� (as Man�����s agent Bjorn Bezemer does), we see and hear hordes of predominantly white Liverpool fans worshiping a black man. A kid in Liverpool reds with English Midlands���s accent speaks to the camera: ���He���s fast, isn���t he? He���s like a lion���you won���t stop him till he get it [ball] to the goal!���

At least according to this documentary, Sadio Man��, extracted from Africa for the industry based in Europe (but followed across the world), is fairly treated and appropriately remunerated. But the fairtrade footballer brand of his goes further than that. And for this, we are taken back to Senegal, from Dakar to Bambali, in 2019. It is almost an hour and ten minutes into the film when Man�� appears on the first floor of his village school and addresses the home-crowd: ���I know you want many things. But education is the priority for our generation. School comes first. You should be in good health before you go to work. So, let���s finish the hospital.���

Just as the fairtrade accreditation demands, the whole of the community should benefit from the extracted export product, and the brand Sadio Man�� does even that. The testimonies of his generous contributions to his village as he mingles with the people fills a warm and emotional feel to the closing scenes. His uncle shares in a slow and impactful voice: ���His success has made us really win a lot of things.���

The story Man�� tells us is almost villain-free. There are no bad guys, not even the football industry, as brutally competitive and cut-throat as it is; the film is sponsored by New Balance. Man�� returns the love the football industry gives him. It is in his focus on education, schools, homes, and hospitals that we must extract the greater message: football is not necessarily a ticket to riches; Sadio Man�� is exceptional.

I have come across nothing to dispute the genius of Man��, both on and off the football field, both as a footballer and as a person. Still, there is an irony to his message. At the age of 15, he secretly ran away from his village and school to pursue a career as a footballer. For two weeks, he stayed in Dakar without the knowledge of his family. He recalls: ���The day I returned to the village was the worst day of my life. I felt hate for my family. I said ���I���m returning to the village on condition that I only have one more year of school. That���s it!��� And they respected my decision.���

And in the long term, he respected theirs���. Born in a family of imams, he was not allowed to play football. He was expected to ���be a good example��� in the village by achieving success through education, not sports. Thirteen years down the line, after achieving success through football, after defying the expectations of his family, he addresses the crowd of young fans with the words: ���education is the priority for our generation. School comes first.���

In these few words, there is pride and grounded awareness of his exceptional football talent and achievements. This is, indeed, an incredible story. He does set ���a good example��� in his village, but also for the celebrities of the world who seem to have greater influence on young people than any other institution: education and health are the priorities and celebrity earnings can be devoted to such superior causes.

More than a two-dimensional African celebrity

Still from Made in Senegal.

This series of posts is based on a Sports Africa Live Round Table held on May 2, 2020 about the documentary film, Sadio Man��, Made in Senegal. The panelists were sports scholars Simon Adetona, Akindes Peter Alegi, Tarminder Kaur, and Ousmane S��ne, from the West Africa Research Center (WARC) in Dakar. Martha Saavedra (University of California, Berkeley) acted as moderator. Prof. Ousmane S��ne (UCAD) was a panelist but did not submit written text. His remarks, however, are featured in the YouTube video recording of the event, as are Martha Saavedra���s comments as panel moderator.

The documentary film, Sadio Man�����Made in Senegal, is a classic ���rags-to-riches��� film. Funded mainly by New Balance, the technical sponsor of Liverpool Football Club, it tells the story of the West African footballer who rises from a humble upbringing in rural Senegal to become a global superstar with Liverpool���s UEFA Champions League-winning side.

Man�� is both the subject and narrator of the film, which uses a mix of on-camera interviews with family, friends, and coaches, among others, as well as graphic novel-like illustrations and selected highlights to help tell his story. The film opens with the striker speaking in French from the comfort of his living room. Viewers are immediately confronted with familiar sportspeak: Man�� looks straight into the camera and tells us he was ���born to be a footballer.��� His dream was always to make it as a pro, to sacrifice and succeed.

Despite the clich��s, the film���s structure is interestingly non-linear. It begins in Bambali, Casamance, a politically tense area of Senegal located south of The Gambia. Man�� grew up around the corner from the dusty village pitch. He fell in love with the game and came to understand it as the only way to avoid spending his life farming for his family.

In an unexpected temporal and spatial pivot, Man�� welcomes the cameras into his spectacularly luxurious summer residence in Spain. He swims in the pool, looks out at the sea, and generally projects a feel of wealth, comfort, and success. We also meet Bjorn Bezemer, his very white European agent, who shows his dutiful reverence by cooking Man�� a tasty breakfast.

Spain is also where Liverpool holds its pre-season camp, and the film briefly takes us there before leaping quickly to the buildup of the return leg of the famous Champions League semifinal against Barcelona. In a legendary comeback, the Reds win 4-0 to overturn a three-goal deficit and qualify for the final. An unsubtle nod to Liverpool technical sponsor suddenly interrupts the film���s rhythm as Man�� does a glam photo shoot for New Balance.

Then, the film makes yet another unexpected move back in time. We are transported to 2008 in Man�����s home village, where we learn about his childhood nickname: Ballonbowa (ball wizard). This is where some of the most revealing storytelling takes place. We learn about the devastating impact the death of his father had on Man�� at the age of seven. We see that his family is devoutly Muslim, with a long tradition of imams in the male line; a family that values education above all else, so the ���ball wizard��� does not have support for his dream of becoming a professional footballer. He decides to leave without his parents��� permission and embarks on an arduous journey through The Gambia en route to Dakar. His family is furious and eventually retrieves him, forcing Man�� to return to school. Once he completes his schooling, however, he is allowed to return to Dakar where he enters the Generation Foot Academy, directed by Mady Tour��.

Not unexpectedly, Man�����s skill, discipline, hard work, and bonhomie impresses coaches and, most importantly, a scout from Metz FC in France (which funds the Academy). He gets his big break and signs a contract with Metz. Culture shock and sports hernia surgery prematurely end his season. The next season, however, he returns stronger than ever. He plays for Senegal in the 2012 London Olympics, a moment of well-earned patriotic pride. The story moves quickly here: in 2012-13 he���s off to RB Salzburg in Austria and then joins Southampton in the English Premier League in 2014-15. After he scores a brace against Liverpool, Jurgen Klopp brings him to Anfield for the 2016-17 season. At Liverpool, Man�� strikes gold. The film now returns to the 2019 Champions League final against Spurs, an opportunity to show Man�� at his successful best.

In a nice touch, the film does not end on a conventional celebratory high. Rather, it follows Man�� back to Senegal, where he prepares for the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations. There are beautiful scenes of him with his extended family in Dakar, as well as his ���prodigal son��� return to Bambali, where he built a school and a hospital���a fine expression of his civic mindedness and social responsibility. That this closing segment unfolds in a Senegalese context encourages the audience to understand Man�� as more than a two-dimensional African celebrity. It highlights the importance of family and Islam to who he is as a human being. Still, there is a stereotypical message embedded in the film���s conclusion, which shows Senegal���s 1-0 defeat to Algeria in the final of the African Cup of Nations: losing is part of sport, but superstars like Man�� turn those lessons into motivation to pursue victory and win, again and again.

The absence of politics is one of the film���s shortcomings. For example, there is one passing mention to ���rebels��� in Casamance toward the end, without even a basic description of the separatist Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC) that emerged in the early 1980s, and its struggle against the Senegalese government and military. (Perhaps this helps to explain why Man�����s Jola background is left largely unexamined.) A different kind of politics overlooked in the film has to do with power relations within football itself. How did Man�� navigate the Generation Foot Academy and, later, the shark-infested waters of professional football in France, Austria, and England? To what extent was Man�����s apolitical character the result of a strategic choice on his part? The filmmakers��� detachment from these tensions tends to reinforce the fallacy that sports and politics do not intersect. Another shortcoming of the film is the superficial coverage of Sadio Man�����s personal life. Viewers learn very little about his off-the-pitch experiences, interests, and relationships.

As ESPN���s series, The Last Dance, exploring Michael Jordan���s final season with the Chicago Bulls recently showed, the commercial sports film genre has clear limitations. Sadio Man��, Made in Senegal is no different. Nevertheless, it is an enjoyable film that should appeal to a broad audience beyond obsessive football fans and devoted Africa scholars.

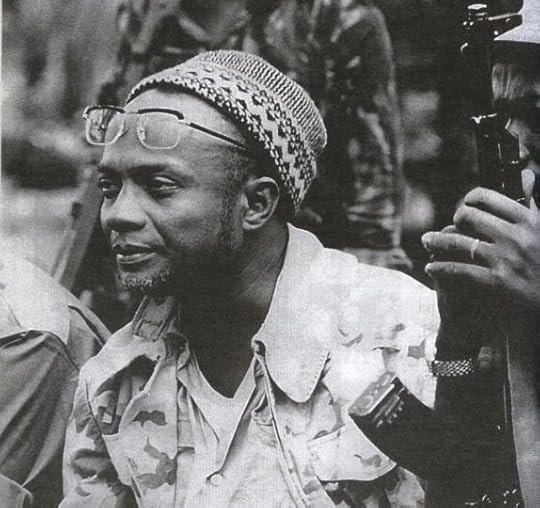

The legacy of a ‘simple African’ revolutionary

Amilcar Cabral

On January 20, 1973, a charismatic African leader was assassinated in Conakry, the capital of the Republic of Guinea. The country was the host of Cabral���s liberation movement, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC). The armed struggle against Portuguese colonial domination in neighboring Guinea-Bissau had entered its 10th year. The murder of Cabral by one of his comrades, in collusion with the Portuguese, reverberated around the world and provoked loud condemnations of Portugal. The New York Times profiled Cabral as ���one of the most prominent leaders of the African struggle against white supremacy,��� while The Times of London portrayed him as ���one of the most extraordinary leaders and thinkers of modern Africa.��� In February 2020, Cabral was voted second greatest leader of all times (after Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Sikh Empire) by more than 5,000 readers of the BBC World Histories Magazine, which commissioned historians to compile a list of 20 great leaders in world history.