Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 165

July 14, 2020

Black Atlantic Lives

Conakry, Guinea. Image credit Jeff Attaway via Flickr CC.

Last month, the brother of George Floyd appealed to the UN Human Rights Council to stop racist violence and the killing of black people in the US. While the current US administration continues to ignore and amplify systemic racism, Philonise Floyd looked well beyond his national borders for help. As he declared, ���Black lives do not matter in the United States of America.��� Floyd���s statement comes alongside weeks of anti-racist protests in cities across the world, with activists and ordinary citizens mobilized and enraged by events in the US. However, this ���global conversation��� on American racial injustice is not a new one. Movements for solidarity across the black Atlantic have a long history, accelerated in the mid-20th century by struggles for decolonization and civil rights. The example of a small country like Guinea shows how intimately black Atlantic lives are connected through shared pain, protest, and hope.

Guinean people have long had an ambivalent relationship with the US. The country has a proud history of anti-colonial politics, launching a socialist cultural revolution in the 1960s, and developing close ties with China and the USSR. Yet, Guinea also maintained friendly relations with the US throughout the Cold War and thereafter. Although the newly independent nation approached the US as a strategically useful ally, it also actively supported dissident black politics and culture, in line with its own commitments to pan-Africanism. Stokely Carmichael and Miriam Makeba fled the US for exile in Guinea in the 1960s, where they were warmly welcomed by the ruling regime. Makeba even went on to deliver Guinea���s annual address to the UN General Assembly in 1976.

Older Guinean artists and audiences reveled in the message of Black Power and the sounds of jazz, funk, and soul���translating these genres into local sounds. At the same time, black audiences in the US admired Guinea���s cultural politics and even adopted the regime���s slogan, ���Ready for the Revolution!��� These ties have continued over the subsequent decades through dance and music���from the Ballets Africains to Y��k�� Y��k�� to hip hop���and through the crisscrossing of people, styles, and ideas. In this process, Guineans have not entirely separated Black and white America. American leaders, from JFK to George Bush and Bill Clinton, have also been celebrated in the country. Guinea���s capital, Conakry, is dotted with posters of Barack Obama as well as places like the Hillary Clinton literacy center.

Guinean people know that US foreign policy is steeped in paternalistic views about the rest of the world. As political commentator Tafi Mhaka recently stressed, America cannot lecture Africa on human rights. However, Guineans also admire many aspects of American political and popular culture. Even as they keenly follow stories of election hacking and interference in the US, they also discuss the merits of its system, its open discourse, and its laws.

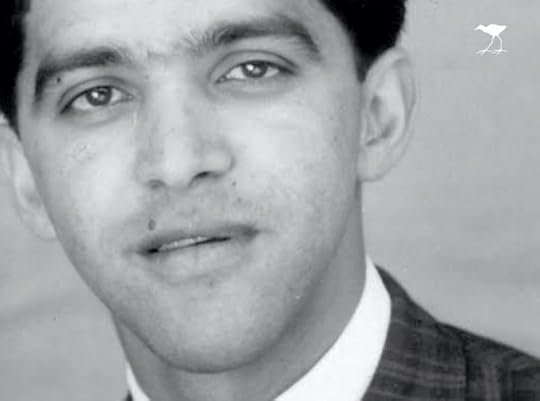

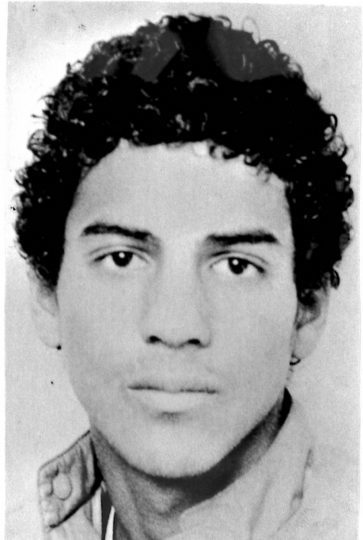

Guinea is also the home country of Amadou Diallo. Diallo was a 23-year old man from the small highland town of L��louma in central Guinea, who eventually moved to New York City to build a life for himself and his family. On February 4, 1999, as he stood outside his apartment building in the Bronx on his way home after dinner, Diallo was senselessly murdered by four officers of the New York City Police Department. They fired 41 shots, killing Diallo in a tsunami of bullets. The police claimed to have seen Diallo holding a gun, when he was, in fact, holding his wallet. The policemen were indicted for second-degree murder and ultimately acquitted on all charges. Their bullets not only killed a young man, but also the hopes of an entire family and a community, who looked to a successful son as a symbol of inspiration and support for others. Amadou Diallo represented a collective dream that was forever extinguished by racist and militarized policing.

Many Americans know of Diallo as ���a West African immigrant,��� but people in Guinea are deeply aware of his national roots. He was a Guinean man who had looked to the US for his future. Local musicians recorded songs about his killing, and how it was linked to racism. Last year, a Guinean newspaper interviewed his mother, Kadiatou Diallo on the 20th anniversary of his murder. As an advocate for criminal justice reform and the head of a foundation named after her son, she is still fighting for justice and said that almost nothing has changed in the US since her son was killed.

Over the past few weeks, Guinean activists and commentators have used the airwaves and social media to remember Amadou Diallo, and to denounce police brutality in the US, just as they have for years protested against police and military violence in Guinea. On the country���s most popular news program, one of the presenters described the US as ���a hotspot for crime,��� while another remarked that with these ���atrocities ��� the state is committing violence.��� As the Guinean sociologist, Dr. Alpha Amadou Bano Barry, tells us, ���America was born in violence. Violence against black people is a fundamental trait of its existence and has always been normalized.��� Barry, along with many of his compatriots, also believes that the swell of protest shows that political reform and cultural change away from the reflex of violence are, finally, now at hand.

This is the view from Guinea. Although the current US President insults countries in Africa, Guinean people see, clearly, what the US is���both good and bad. In speaking out against racist violence, they are speaking directly to Philonise Floyd and his fellow American activists. They signal that the world is watching and listening, and not looking for leadership from the US, but pushing in solidarity for change.

Let us remember Amadou Diallo and say his name, and let us collectively continue the history of struggle and solidarity.

Black Atlantic lives

Conakry, Guinea. Image credit Jeff Attaway via Flickr CC.

Last month, the brother of George Floyd appealed to the UN Human Rights Council to stop racist violence and the killing of black people in the US. While the current US administration continues to ignore and amplify systemic racism, Philonise Floyd looked well beyond his national borders for help. As he declared, ���Black lives do not matter in the United States of America.��� Floyd���s statement comes alongside weeks of anti-racist protests in cities across the world, with activists and ordinary citizens mobilized and enraged by events in the US. However, this ���global conversation��� on American racial injustice is not a new one. Movements for solidarity across the black Atlantic have a long history, accelerated in the mid-20th century by struggles for decolonization and civil rights. The example of a small country like Guinea shows how intimately black Atlantic lives are connected through shared pain, protest, and hope.

Guinean people have long had an ambivalent relationship with the US. The country has a proud history of anti-colonial politics, launching a socialist cultural revolution in the 1960s, and developing close ties with China and the USSR. Yet, Guinea also maintained friendly relations with the US throughout the Cold War and thereafter. Although the newly independent nation approached the US as a strategically useful ally, it also actively supported dissident black politics and culture, in line with its own commitments to pan-Africanism. Stokely Carmichael and Miriam Makeba fled the US for exile in Guinea in the 1960s, where they were warmly welcomed by the ruling regime. Makeba even went on to deliver Guinea���s annual address to the UN General Assembly in 1976.

Older Guinean artists and audiences reveled in the message of Black Power and the sounds of jazz, funk, and soul���translating these genres into local sounds. At the same time, black audiences in the US admired Guinea���s cultural politics and even adopted the regime���s slogan, ���Ready for the Revolution!��� These ties have continued over the subsequent decades through dance and music���from the Ballets Africains to Y��k�� Y��k�� to hip hop���and through the crisscrossing of people, styles, and ideas. In this process, Guineans have not entirely separated Black and white America. American leaders, from JFK to George Bush and Bill Clinton, have also been celebrated in the country. Guinea���s capital, Conakry, is dotted with posters of Barack Obama as well as places like the Hillary Clinton literacy center.

Guinean people know that US foreign policy is steeped in paternalistic views about the rest of the world. As political commentator Tafi Mhaka recently stressed, America cannot lecture Africa on human rights. However, Guineans also admire many aspects of American political and popular culture. Even as they keenly follow stories of election hacking and interference in the US, they also discuss the merits of its system, its open discourse, and its laws.

Guinea is also the home country of Amadou Diallo. Diallo was a 23-year old man from the small highland town of L��louma in central Guinea, who eventually moved to New York City to build a life for himself and his family. On February 4, 1999, as he stood outside his apartment building in the Bronx on his way home after dinner, Diallo was senselessly murdered by four officers of the New York City Police Department. They fired 41 shots, killing Diallo in a tsunami of bullets. The police claimed to have seen Diallo holding a gun, when he was, in fact, holding his wallet. The policemen were indicted for second-degree murder and ultimately acquitted on all charges. Their bullets not only killed a young man, but also the hopes of an entire family and a community, who looked to a successful son as a symbol of inspiration and support for others. Amadou Diallo represented a collective dream that was forever extinguished by racist and militarized policing.

Many Americans know of Diallo as ���a West African immigrant,��� but people in Guinea are deeply aware of his national roots. He was a Guinean man who had looked to the US for his future. Local musicians recorded songs about his killing, and how it was linked to racism. Last year, a Guinean newspaper interviewed his mother, Kadiatou Diallo on the 20th anniversary of his murder. As an advocate for criminal justice reform and the head of a foundation named after her son, she is still fighting for justice and said that almost nothing has changed in the US since her son was killed.

Over the past few weeks, Guinean activists and commentators have used the airwaves and social media to remember Amadou Diallo, and to denounce police brutality in the US, just as they have for years protested against police and military violence in Guinea. On the country���s most popular news program, one of the presenters described the US as ���a hotspot for crime,��� while another remarked that with these ���atrocities ��� the state is committing violence.��� As the Guinean sociologist, Dr. Alpha Amadou Bano Barry, tells us, ���America was born in violence. Violence against black people is a fundamental trait of its existence and has always been normalized.��� Barry, along with many of his compatriots, also believes that the swell of protest shows that political reform and cultural change away from the reflex of violence are, finally, now at hand.

This is the view from Guinea. Although the current US President insults countries in Africa, Guinean people see, clearly, what the US is���both good and bad. In speaking out against racist violence, they are speaking directly to Philonise Floyd and his fellow American activists. They signal that the world is watching and listening, and not looking for leadership from the US, but pushing in solidarity for change.

Let us remember Amadou Diallo and say his name, and let us collectively continue the history of struggle and solidarity.

We are all brothers

Luqman Abdul-Hakeem (82), a close follower of Malcolm X that chauffeured the African American activist around and introduced him to Cuban leader Fidel Castro in September 1960, shows a picture of him (on the left) with the two leaders published in Rosemari Mealy's book "Fidel & Malcolm X. Memories of a meeting", in his home in Sidi Maarouf, a district of Casablanca, Morocco, on May 14th 2016.

Malcolm X visited Africa in 1964, two years after Algeria���s independence from French colonial rule, and one year before his martyrdom. During that visit, he noticed the stark similarities between the brutality of colonial state violence in Algiers and the ���occupying armies��� of the police in Harlem. On his return, he addressed a labor forum in New York City in March 1964:

I visited the Casbah ��� with some of the brothers���blood brothers. They took me all down into it and showed me the suffering, showed me the conditions that they had to live under while they were being occupied by the French ��� They lived in a police state, Algeria was a police state. Any occupied territory is a police state, and this is what Harlem is. Harlem is a police state. The police in Harlem���their presence is like occupation forces, like an occupying army. They���re not in Harlem to protect us; they���re not in Harlem to look out for our welfare ���

Malcolm X recognized the commonality between colonialism in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, and the subjugation of black people in the US. He also explained the need for a common resistance to this oppression:

[The Algerians] also showed me what they had to do to get those people off their back. The first thing they had to realize was that all of them were brothers; oppression made them brothers; exploitation made them brothers; degradation made them brothers; discrimination made them brothers; segregation made them brothers; humiliation made them brothers. And once all of them realized that they were blood brothers, they also realized what they had to do, to get that man off their back.

The past year has seen a resurgence of resistance movements across the global south. Nonviolent protests, which began in Algeria, framed their demands as a continuation of the struggle against the colonial indignities and injustices that Malcolm spoke about. Protestors made a point about the urgent need for a restructuring of the political and economic system that has proven to be at the service of the ���political-financial mafia,��� and its continued ties to French and other European economic and cultural colonialism. Simultaneously, black people���many of whom operate out of an ���economic South in the geographic North,��� have called for a reckoning of the US police state, and the persistence of the white supremacist racism that kills black bodies. In Palestine, plans by the Israeli settler colony for further land theft has led to a global Day of Rage. And in the last year, protests emerged in Sudan, Lebanon, and Iraq, as well as Chile, Colombia, and Venezuela. In all of these cases, there has been a growing realization of the common thread between state repression and its ties to global power.

However, as the Algerian writer Malek Bennabi explained in 1956 of the then-nascent Third-Worldist movement,�� the recognition of common conditions of oppression does not necessarily produce a Third-Worldist consciousness and program. For this reason, thinkers, politicians, and activists in the 20th century worked to forge a program of global, Third-Worldist resistance to global power. Protestors in Algeria, the US, and elsewhere must likewise begin to imagine what a new, grassroots Third-Worldism of the 21st century might look like.

As Algerians plan to resume protests to coincide with the 58th anniversary of Algerian independence on July 5th, and this in the wake of mass protests following the murder of George Floyd in the U.S., renewed attention to the history of Third-Worldism and Algeria���s role as a mecca of revolution might help inspire such a program. Both contemporary movements have already recognized the ties to predatory global capitalism and continue to resist them; both movements have also celebrated and been celebrated globally, with symbols of solidarity being exchanged in many directions.

Following independence in 1962, revolutionaries from the Americas, Asia, and Africa similarly flocked to Algeria in attempts to forge a ���third-way������global ties of resistance to both Euro-American and Soviet colonialism and neocolonialism in the second half of the 20th century.

This movement took strong root in independent Algeria. Eldridge Cleaver led the office of the International Section of the Black Panther Party in Algiers (though in a sometimes tense relationship with the Algerian state). Frantz Fanon���s writings from his base in Algiers became field guides for black radicals in the US, and Nina Simone headlined the Pan-African Festival of Algiers in 1969. Shortly after Algerian independence, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. met with President Ben Bella in New York, of which he wrote:

All through our talks [Ben Bella] repeated or inferred, ���We are brothers.��� For Ben Bella, it was unmistakably clear that there is a close relationship between colonialism and segregation. He perceived that both are immoral systems aimed at the degradation of human personality. The battle of the Algerians against colonialism and the battle of the Negro against segregation is a common struggle.

According to historian Jeffrey Byrne, however, and despite Third-Worldist rhetoric of global solidarity, the movement often replicated, and thus re-inscribed, the primacy of the sovereign nation state. By extension, the model of Third-Worldist policies and international conventions, for example the Bandung Conference, often mimicked the political organization of the Cold War that privileged international bodies based around individual sovereign states. Perhaps because of this, a movement that rallied around ideals of Third-World unity may have worked to create a more state-centric and divided world.

Beyond nostalgia, this memory of the internationalism that was a prominent element of the post-colonial nation-state building projects of the 20th century should highlight the lessons of Third-Worldism and Afro-Asianism that was best captured in the spirit of the Bandung Conference of 1955. From these lessons, new strategies for connecting struggles against colonial capitalist domination must be forged, as Malcolm X insisted, from the streets of the Casbah to the hoods of America.

Algerian activists, however, must address serious problems that have persisted since Algeria���s independence���connected to a globalized racism that they are not immune to. Examples of xenophobia and pathologizing of blackness are well documented at both the popular level as well as among government officials. Even more, recently, social media activists have engaged in disturbingly racist performative solidarity with the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement.

As Algerians return to the streets to demand transparency in the constitutional referendum process, a legitimate democratic transition, freeing of all political prisoners, and the removal of entrenched and corrupt leadership, an eye should be kept on beginning to forge ties of global solidarity that are not dictated along national lines, and that redress Algerians��� problematic relationship to blackness. Despite these persistent problems, and as Malek Bennabi, Malcolm X, and others noted of the previous century, the conditions of repression that continue to plague black people in the US empire and Algerians in the current dictatorial and neocolonial regime remain connected. Thus, resistance to them must be connected as well.

July 13, 2020

The new ‘invisible enemy’

March on Tillary Street in New York. Image credit Doug Turetsky via Flickr CC.

In 2005, Middle East Report (MERIP) published an article by political scientist Hisham A��di, ���Slavery, Genocide and the Politics of Outrage: Understanding the New Racial Olympics.��� MERIP recently decided to re-publish A��di���s piece on the Save Darfur movement. In this post, A��di compares the current Black Lives Matter protests to the Darfur mobilization.

In hindsight, June 16, 2015 was a turning point, a date critical to understanding today���s political tumult. That was the day Donald Trump announced his candidacy for president, theatrically descending the escalator at Trump Tower, then giving a rambling speech that linked illegal immigration, terrorism, and the offshoring of American jobs. It was the moment when he introduced the phrase ���Make America Great Again��� and vowed to build a ���great, great wall on our southern border.��� The media would focus on his derogatory remarks about Mexicans ���bringing drugs, bringing crime.��� Trump���s candidacy would cause an immediate spike in hate crimes and send political groups scrambling to join forces with���or distance themselves from���whichever group he targeted next. His following surged as he rode the wave of white nationalist backlash to immigration, failed wars and a black incumbent.

Among the more intriguing developments in the wake of Trump���s candidacy was the rise in anti-Muslim speech from Hispanic celebrities and public figures. Conservative Hispanic politicians had long argued that immigration reform was stalling because of Muslim terrorists slipping through the southern border. For example, New Mexico Governor Susan Martinez had called for more security at the US-Mexico border in 2013, after Border Patrol agents found candy wrappers with Arabic writing. But Trump���s brutal joining of the question of Hispanic migration with terrorism, of Islamophobia, and Hispanophobia (long linked in French and English colonial thought, but not in the American imaginary) would unleash a torrent of anti-Muslim speech on Spanish talk radio and social media. Miss Puerto Rico Destiny V��lez tweeted that Muslims ���terrorize innocent Americans,��� adding that, ���Mexicans, Arabs, Jews and anything in between aren���t the same thing.��� In August 2015, Ramon Escobar, a youngish Hispanic American diplomat who had handled State Department engagement with the Muslim world, ranted to a handful of journalists about his tour in Saudi Arabia, saying that in the Gulf���s failed societies ���it���s always the will of Allah��� and expressed outrage that Latinos were being associated with terrorism. As the campaign unfolded, more prominent Hispanic politicians sounded off: Texas Senator Ted Cruz called for law enforcement to patrol Muslim neighborhoods while Florida Senator Marco Rubio denigrated President Barack Obama for visiting a mosque in Baltimore. This rhetoric was aimed at distancing Latinos from Muslims, to signal that Latinos were not a national security issue.

Trump���s candidacy and rise to office ultimately proved as politically cataclysmic as the events of September 11, 2001, generating unexpected animosities, alliances, and bizarre new discourses. Thirty percent of Latinos ended up voting for Trump, while Hindu nationalists rallied behind his stances on terrorism and immigration. But Trump���s ascent also precipitated much solidarity on the left, as groups mobilized against the Muslim ban and to defend DACA. Resistance to Trump also coalesced to produce wins for progressive candidates nationwide, including four women of color (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib) elected to Congress in 2018 who became known as The Squad. These victories occurred alongside a surge of hate crimes against Jews, Muslims, and Hispanics, with a terrible mass shooting of Hispanics at a Walmart in Texas in November 2019. As groups integrate into the American political process, they often reflect the country���s deep rifts, frequently manifesting in a split between those wanting to express solidarity or opposition to the Muslim other. Unsurprisingly, the Trump years have been characterized by a rise in Hispanic Islamophobia, including the tragic high-profile murders of Muslims by young Hispanics, most prominently of Nadra Hassanen in Washington, DC and Imam Maulana Akonjee and Thara Uddin at a mosque in Ozone Park, Queens.

In early 2005, I was a postdoctoral fellow at the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland, trying to understand a social movement that was spreading rapidly across US campuses and cities, and eventually to France and Britain. The Save Darfur movement took off in early 2004���in circumstances not unlike the present moment���as a buffoonish, flailing Republican president ran for a second term against a lackluster Democratic candidate in a war on terror context. I subsequently published an essay in Middle East Report titled ���Slavery, Genocide and the Politics of Outrage: Understanding the New Racial Olympics��� that sought to explain why of all the civil wars in Africa and humanitarian crises in the world, it was the mass violence in western Sudan that had gripped the American imagination. The answer, I argued, lay in the post-September 11 domestic political scene:

Unlike other hot spots across Africa, the Darfur tragedy reverberates deeply in the US because it is represented as a racial conflict between Arabs and indigenous Africans, because Sudan is where the ���moral geographies��� of black, Jewish and Christian nationalists overlap and because the Darfur crisis offers a unique opportunity to unite against the new post-Cold War enemy.

The Save Darfur movement started on college campuses to counter pro-Palestinian agitation. When Students for Justice in Palestine would bring Israeli refuseniks to speak, the American Anti-Slavery Group founded by Charles Jacobs���who would also launch Save Darfur���would respond by bringing Sudanese ���lost boys��� to speak about Arab racism. Jacobs was also the founder of The David Project, which monitored Middle East Studies departments for alleged anti-Israel prejudice and funded the film��Columbia UnBecoming, which claims to document incidents of bias in that university���s Department of Middle East and Asian Languages and Cultures.

To show how these three American nationalisms���evangelical, Jewish and black���overlapped in Sudan, I highlighted three frontiers: the colonial and Huntingtonian so-called faultline between Africa and the Arab world that ran through Sudan; the urban periphery where competing conceptions of the Middle East co-existed uneasily and where Latino immigration was leading to fears of ethnic succession; and finally the US-Mexico border where Hispanic migration had led to Minuteman vigilantism and to Samuel Huntington���s warning of a ���demographic Reconquista��� and a backlash from whites fearing ���replacement.���

The current protest movement against police brutality���unfolding during a horrific pandemic crisis that has exposed and deepened societal fissures���clearly differs from the Save Darfur movement. For starters, the current protest is against American state violence, specifically the recurring spectacle of police cruelty against black men. Black Lives Matter is not calling for military intervention, and in fact has an anti-colonial facet. Save Darfur activists, on the other hand, would often chant ���Out of Iraq, Into Sudan.���

Since the COVID-19 crisis began in February, the global war on terror seems to have faded away; the war on the new ���invisible enemy������and the Trump administration���s hapless response���have dominated headlines. The absence of a Muslim bogeyman seems to have created space for new alliances and coalitions, as the establishment foreign policy hawks have receded from view. Another difference is that while, in 2005, some older Afrocentrists (like the late comedian Dick Gregory) supported Save Darfur, the majority of black (and minority) leaders steered clear of the movement. Save Darfur ended up being a largely white movement led by a Jewish-Christian coalition. Jewish organizations, which agitated on campuses in the mid-2000s, have been relatively silent in recent years, perhaps because their policy objectives have been achieved. The Department of Education has moved to sanction and deny Title VI funding to a number of Middle East Studies programs deemed biased, the US embassy has been relocated to Jerusalem and Israel is moving to annex additional Palestinian territories.

The current movement, under the aegis of Black Lives Matter, is multi-ethnic and multi-racial, and while it has inspired protests globally, it is focused domestically on police violence and reparations. If Trumpism was a response to the humiliation of failed wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (it is no coincidence that the Minuteman Project began patrolling the southern border days after the Abu Ghraib story broke) then Black Lives Matter is protesting the militarization of urban policing resulting from those same unending wars. The decades of counterinsurgency abroad have boomeranged back home with the expansion of mass surveillance under Obama and the continuation of the Pentagon���s 1033 program that has transferred $7.4 billion of surplus military equipment (such as armored vehicles and rifles) to law enforcement departments nationwide.

In February 2015,��The Guardian broke a story about a ���black site��� operated by domestic law enforcement in Chicago, echoing the secret detention facilities used by US defense and intelligence agencies to interrogate and torture prisoners overseas. The militarization of policing may have been newsworthy in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014 after the death of Michael Brown at the hands of the police, but it barely registered in 2012 when then-Mayor Pete Buttigieg shared a New York Times��article titled ���With Green Beret Tactics, Combating Gang Warfare��� with the comment: ���Interesting use of counter-insurgency tactics to address gang violence.��� Nor was much made of Minnesota Governor Tom Waltz���s recent claim that the unrest made American cities look like Baghdad or Mogadishu.

Now, 15 years after Save Darfur, American power and prestige are vastly diminished. In 2005, the neo-cons calling for intervention in Sudan were in part vexed by China���s access to Sudan���s oil, as well as Beijing���s refusal to isolate the regime of former Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir. (Stephen Spielberg famously withdrew as adviser to the Beijing Olympics because of China���s Darfur policy.) Today as Chinese-American relations are in free-fall, China has surpassed the United States as Africa���s biggest trade partner and Trump allegedly appealed to Chinese President Xi Jinping for help in the upcoming election.

But the parallels and continuities between Save Darfur and the current movement are striking���the three frontiers are still politically relevant. At his inaugural speech, Trump warned that ���places like Afghanistan are safer than our inner cities.��� The president is still intrigued by comparisons of Islam���s ���bloody borders��� with the southern US border and continues to link the two, as when he threatened to designate Mexican drug cartels terrorist organizations, or when he placed Venezuela on the updated Muslim ban list because the Maduro government was allegedly granting Venezuelan passports to Hezbollah militants.

Prima facie, the president���s fascination with the inner city may appear less comprehensible than his obsession with the southern border; but these two frontiers are critical to understanding his persona. Trump���s America First worldview, we are told, is rooted in Jacksonian nationalism, which harks back to Andrew Jackson, the notorious slave-owning and slave-selling president and architect of the Indian Removal Act, whose portrait currently hangs in the Oval Office. In his well-regarded��Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World (2002), Walter Russell Mead describes the Jacksonian tradition as the honor-based, Scotch-Irish ethno-nationalism of the American frontier, a folk community hostile to elites, immigration, and international law, which believes the US should deploy ruthless military power whenever threatened. In an aside, Mead argues that despite their white supremacist roots, Jacksonian values had a major influence on African American culture in the South and also in the gang culture of inner cities which have re-created ���the atmosphere and practices of American frontier life.���

Few would think of Trump as a blend of hip hop and Jacksonian swag, but a case could be made. Trump was an icon in hip hop culture for decades, a symbol of ostentatious wealth, his name mentioned in some 300 rap lyrics. As Charles Blow of��The��New York Times wrote, the Queens-born real estate magnate rose alongside the genre in 1970s New York watching ���the moguls it made, the bravado it brandished. He liked it, envied it, aped it.��� And for all his disdain for poor minorities, soon learned ���how to assert white privilege and emulate black power.��� In fact, Trump weaponized New York city���s hip hop culture, appropriating���in Blow���s words���the ���coarser side��� of black culture to build a blustering populist brand that propelled him to the country���s highest political office. It is ironic that as gangsta rap declined in the mid-2000s (making way for a gentler, more up-lifting Kendrik-Drake sound), its echoes can still be seen in the Oval Office and among populist strongmen elsewhere. Consider Brazilian leader Jair Bolsonaro, who has a coterie of MAGA-hat-wearing rappers who compose lyrics in support of his reactionary platform. Still, it is worth emphasizing that in the US (and Brazil) the hip hop community turned overwhelmingly against Trump once he was in the White House.

As during the Darfur crisis, the Muslim grocer in the inner city is still a source of contention. In November 2005, liquor stores in Oakland owned by Muslim immigrants were vandalized (one store burnt down, and an employee kidnapped.) In 2015, following the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson outside a store owned by an Indian immigrant, a boycott was organized of immigrant-owned stores. Anger at the figure of the Muslim grocer has surfaced again since the death of George Floyd, when it emerged that the call to the police was made by an employee of a Palestinian-owned grocery, prompting more calls for boycotts as well as attacks against Middle Eastern and South Asian-owned businesses in a range of cities. The debate continues among African Americans on the merits of solidarity with Arab/Muslim organizations. In 2005, Arab and Muslim activists were focused on lobbying the US Census Bureau to add a new MENA (Middle Eastern and North Africa) minority status category that would allow Americans from the region to claim non-white identity, and thus qualify for various civil rights protections (including special status as potential hate crime victims) as well as benefit from affirmative action policies. An energized black-Palestinian left emerged in 2014 speaking of a Gaza-Ferguson nexus, but a self-described school of Afropessimism continues to be wary of forming solidarities, especially with the Arab world where these critics say ���anti-blackness��� is ���foundational.���

Given that the Trump White House has flatly opposed the census request, these young anti-racism activists from Arab and Muslim backgrounds have turned their energy to countering police violence and surveillance as well as addressing the image of the anti-black Muslim shop-owner. Multiple initiatives have been launched by Middle Eastern and North African Americans���scholars and activists���most recently ���Arabs For Black Lives��� that attempt to mediate between Muslim grocers and their patrons by providing training in cultural difference, de-escalation, and support for these merchants to ���go green��� and carry produce in lieu of liquor and junk food. The generation that was in high school during the Darfur crisis has now come of age. But there remains a political gulf between this younger generation of woke Muslim activists, who are eager for acceptance into BLM and similar coalitions, and who are harshly critical of the much-maligned grocer���sometimes speaking of them as settlers and exploitative colonists���and the older generation (among them the shop-owners) who do not understand the difference between a Becky and a Karen, and do not see why they should be criticized for selling the alcohol and tobacco products their customers demand. Ironically, some of this local opposition leads Muslim grocers to relocate to Hispanic neighborhoods, where immigrant merchants selling such products have been less likely to draw criticism. Despite the Islamophobic rhetoric from political hopefuls, a recent poll shows that among whites, blacks and Hispanics, Hispanic Americans score the lowest on the Islamophobia Index, with Hispanic Americans five times more likely to hold favorable opinions of Muslims than negative ones (51 percent versus 10 percent).

In my 2005 essay, I concluded by observing that the topic of racism in North Africa and the Middle East has long been dominated by external interests and actors and marked by official suppression of all discussions of the region���s legacies of slavery and racism. But even in the mid-2000s, one could see the emergence of an anti-racism discourse in the Middle East, enabled by the internet. That process has accelerated. The final sentence called for a celebration and mobilization of Afro-Arab identity against tired Arab nationalist narratives and colonial separations.

Since the 2011 uprisings in the Middle East, and especially with the passage of Tunisia���s anti-racism law in October 2018, social media abounds with Afro-Arab activists and new collectives. These black Arab voices run the gamut from socialist pan-Africanist feminists who quote Angela Davis to Afrocentrists who quote John Henry Clarke and his theory of Arabs overrunning Africa, a discourse last heard during the Save Darfur moment. The past is preface.

Geopolitically, much has changed���and not changed. The Sudanese strongman Omar Al-Bashir was toppled by a protest movement and is in prison awaiting an International Criminal Court trial for war crimes committed in Darfur. Yet Sudan is still in America���s crosshairs. The mass violence in South Sudan has not resonated with the American public, but the new Sudanese regime is still under heavy pressure from Washington to recognize Israel in exchange for a lifting of sanctions���coercion that could derail Sudan���s transition. Brand activism continues as well. Save Darfur drew celebrities and corporate actors, as companies began selling Darfur underwear, video games, and Timberland boots. Today retail companies are scrambling to capitalize on Black Lives Matter. Walmart has pledged to stop locking up so-called multicultural hair products in display cases and BAND-AID has released new bandages in different skin tones.

In conclusion, it is worth recalling that before America���s grand ���awokening��� of 2020, there were protest movements in Sudan, Lebanon, Chile, Algeria, France, and Spain centered on exclusion and state violence. It is exhilarating to watch a protest movement against state brutality, white supremacy, colonial memory, and Trump-inspired racist contagion spread around the world. But it is not clear that an American-style anti-racism can counter racism in societies elsewhere, with their own race regimes and constructs. More importantly, it is worth noting that a backlash to the current protests is in the offing. This counter-movement could easily attempt to unify a polarized nation with time-honored tactics of division and distraction: by smashing current links of solidarity and directing the collective anger and bereavement caused by American policy failures toward a domestic or international other, be that Iran, Venezuela, Sudan, or mosques in America, as happened in 2005.

Plus ��a change���

A debased tradition

Book cover of The Murder of Ahmed Timol.

October 22, 1971, may have seemed quite an ordinary day for Ahmed Timol. He and a friend had set off that Friday night in a yellow Ford Anglia, bound for a party, when they were stopped at the top of Fuel Road in Coronationville. The police manning the roadblock were not looking for terrorists. They stopped him because he flagged their suspicion. Because he flagged their suspicion, he was searched. Because he was searched, they found materials (pamphlets and posters) they considered to be subversive.

From that night until the weekday morning six days later when he was thrown from the tenth floor of John Vorster Square, life continued to pass in an ordinary and unremarkable way for everyone except the family of Ahmed Timol. The fiction of the ordinary allowed everyone else to carry on as usual. While people were waking up, going to bed, playing golf, test driving their new car, celebrating birthdays, mowing their lawns, or doing small out-of-the-way things, in one of apartheid���s belligerent concrete landmarks a man was being tortured. Presumably there were some people going about their business on that day who saw or heard Timol clatter on to the pavement of Commissioner Street. Nobody came forward.

I began reading Imtiaz Cajee���s The Murder of Ahmed Timol while South Africa was restlessly dealing with a Covid-19 lockdown that resulted in an astonishing number of people dying from violence meted out to them by the police. A free press means that these deaths could not easily be suppressed or explained away in the callous manner that Timol���s killing was. As the controversy over how police were handling their duties simmered in South Africa, a stark absence of shrouding enabled the world to watch (not witness) the murder of George Floyd. Images and videos circulated, the outcry reverberated and gained momentum. It was singularly jarring to experience the piercing interruption of this brutal event amid the unfolding saga of catastrophe and death that has been 2020.

The policeman who choked the life from Floyd���s body and his fellow officers who looked on seemingly unperturbed did so because they felt fairly safe in the fact of their being police. That fact granted them a measure of power that has been possessed by the modern police force since its instantiation as a by-product of modernity at the turn of the twentieth century. Their power is the right to decide when someone is so dangerous that their life can be taken from them. Timol, by most accounts, was hardly a dangerous saboteur intent on slitting the throat of white South Africa. The subversive material he was caught with amounted to a few pamphlets and posters in support of an Anglican priest who was fasting on a mountain in Cape Town to protest against the death in detention of Imam Abdullah Haron. No poster has ever overthrown a government. It didn���t matter why he was arrested. The reasons are always trivial: a traffic stop also sealed Steve Biko���s fate. A casual traffic stop, as we have seen in numerous shaky video captures from the United States, has the potential to become something life ending very quickly.

After Timol���s murder, a desultorily convened commission declared that there was nobody to blame. The magistrate who presided over the sham concluded that Timol had committed suicide, and that before he died he had been treated in a civilised and humane manner. A court whose magistrates and judges were committed followers of apartheid, who conducted themselves as sycophants of the criminal regime, was always going to debase itself. In the landmark court judgement that reopened the case forty-two years later, Judge Billy Mothle said the following of these complicit functionaries: ���These persons betrayed and demeaned their respective oaths of office by participating in inquest proceedings that became a sham; concealing the atrocities committed by the Security Branch and ensuring that the judicial system finds no one to blame.��� He rejected the evidence presented by the apartheid state in 1972 as a crude cover-up ���conjured to conceal the truth���.

The debased tradition of police murdering civilians has a rich index in South Africa. Because the country itself is based on absurd violence, there is often a puzzled resignation before the absurdity of state-enacted murder. When the Marikana massacre took place in August 2012, you wouldn���t have had to go too far to find people expressing sentiments that boiled down to, ���Yes it���s a pity, but what did they do to bring it about?��� We understand that policing operates in a particular way and so, when confronted with news about policing gone wrong, the default for many people is to assume that the glitch was caused by the victim. When Timol���s death was announced, the protests on university campuses and public calls for a commission of inquiry were quelled by a sham trial that brimmed with contemptuous lies. His is a story that could never be told while apartheid was present. It is a story that echoes through the stories of seventy-one other prisoners who died in police detention between 1963 and 1990���all under suspiciously opaque circumstances.

The man who was ostensibly the last person to see Timol alive, Joao Rodrigues, is captured in a police photograph of the room in which Timol was being held, standing with his back to the camera. Cajee���s description of him paints a picture of the banality of Special Branch:

taken from behind, it shows a man dressed in Afrikaner male fashion of the day: knee-length socks and a light-coloured safari suit with short pants. He was facing an open window. It was the window from which he claimed that my uncle jumped to his death.

Rodrigues has painted himself as a rank-and-file functionary of the secret police, someone who delivered salary cheques and other mail. Yet he is, according to his own story, someone who was trusted with the guarding of Timol. A conveniently vague witness, whose passivity in the photograph heavy-handedly pantomimes his lack of involvement. Rodrigues has maintained a version of the story that exonerates himself and his colleagues from any blame for Timol���s departure through the window. At the 2017 reopening of the investigation, Cajee describes his shock at the sight of the man who was attempting to evade scrutiny through claims of decrepitude:

The first time I saw Rodrigues in the flesh I was taken aback by his size. Nudging eighty years old and walking with a cane after a recent surgery, he showed no signs of a shuffle or a stoop. At 1.88 metres tall, he appeared just as fit, erect and strong as he did in the photograph, taken nearly fifty years before. I had had decades to ponder the events that took place in that room on the top floor of the security police headquarters in Johannesburg. I had imagined my uncle���s last moments over and over again. The bullying, humiliation, assault and, finally, the murder of my beloved uncle by hefty policemen.

Nobody applied for amnesty in connection with Timol���s murder. The policemen responsible for his death used to joke among themselves that “Indians can���t fly.” And yet when peace was brokered, they removed themselves, slipped into civvies, and were carelessly allowed to disappear into the post-apartheid scene. The distaste for recrimination that has presided in the years since 1994 has brought with it a concomitant reluctance to commit to the adjustments required for fundamentally changing the system. They even kept John Vorster Square, site of countless bludgeonings, electrocutions, and other artless forms of truth-extraction (many of which would later be excused with equal artlessness as suicide). The building was regarded as infrastructure rather than symbol, just as the methods and tactics of civilian suppression witnessed in South Africa during the Covid-19 pandemic are infrastructural retentions we are not supposed to pay attention to. When the army was called onto the streets to police the lockdown restrictions, they almost immediately began to demonstrate what they believed policing was. The viral videos of camo-clad oafs abusing and humiliating the populace���chasing people with whips, beating and kicking them���are clear evidence of the imaginatively deficient view of policing that continues to hold sway.

The past is buried when people dig in their heels and say “nothing will be gained from excavating and uncovering.” The brusque dismissal of calls for the past to be raked over is part of the pretence and delusion that apartheid disappeared with the arrival of the first Black government. But while many evasive figures expired in drooling denial without seeing justice for the crimes they authorized, others are still very much alive. They appear in public to demand apologies because they believe they have been calumnied. They lead foundations from which they issue historically revisionist falsehoods.

In the preface to his book, Cajee suggests, of the key witness in his uncle���s death:

I am mature enough to know that context is important and that Rodrigues was a minor player in an insidious and dirty war against black emancipation; it would have been very difficult for him to resist whatever instructions he was given to cover up my uncle���s murder. But that was then, and this is now. We���ve had more than two decades since the end of apartheid to recalibrate our positions on morality and justice.

Reading Cajee���s book during this time has drawn me into a complex consideration of the impact of structural racism in the wake of its exhausting and repetitive violence against Black people. In the hands of someone who has dedicated themselves to reassembling a hidden narrative, The Murder of Ahmed Timol jolts us back to the reality of a mode of violence that refuses to disappear. Timol���s story, in other words, provides a structure for thinking about what this moment might be saying to us. What continuities can be drawn from his death in apartheid Johannesburg to the murder of Eric Garner in New York City, or to the killing of Floyd in Minneapolis? Looking at the story of Timol���s death allows us to perceive a history of violence that has resisted fundamental change. It is a story that extends easily forwards in time to Marikana, or across to Britain, where Jimmy Mubenga died on a plane as he was held down by security guards. It is a story that extends to Breonna Taylor, shot dead by police in Kentucky in March. It is a story that stretches back to the death of Suliman Saloojee, rarely mentioned, or of David Oluwale in Leeds, now transformed into a symbol of urban regenerative glad-handing. Each is a single story, and each deserves its own telling. But what facts would you use to tell the story in a meaningful way?

July 12, 2020

Face-me-I-face-you

Lagosians struggling to access government sponsored COVID-19 emergency food bags. Image credit Kunle Ogunfuyi via Flickr CC.

In all its contexts, the crisis caused by COVID-19 has illuminated the stark inequalities which plague society. As the virus has inched across the world, patinas of equality have been torn away. As it turns out, access to financial support, medical care, and public health infrastructure are nakedly organized along pre-existing lines of privilege and wealth. Those at risk of catching, and dying of COVID-19 are themselves much more likely to be poor. Any naive assumptions that the coronavirus would act as a ���great leveler��� have been thoroughly discredited. Yet in Lagos, Nigeria���s commercial capital, these trends are further compounded by the architecture of the city. As the most populous urban center in Africa, Lagos is home to an estimated 20 million residents. It is also the smallest state in Nigeria, constituting a land mass of approximately 3,345 square kilometers. In the era of coronavirus, the distribution of space in Lagos has overlaid responses to, and implications of, the pandemic. While public calls to stay at home are blasted on social media from the villas and mansions of celebrities, the working class are stuck in overcrowded housing, exposed. The implications of the coronavirus crisis in Lagos are refracted through the cartography of class, as we illustrate here.

One of the manifold corollaries of the coronavirus pandemic in Lagos has been its magnifying of the class divide. Indeed, class privilege has long manifested itself within the politics of space in the city, inherited from colonialism. While the dimensions of the city have expanded, and urban architecture on (much of) the mainland has been reformulated, certain sections of the axis of Lagos known colloquially as ���the Island��� (i.e. Victoria Island, Ikoyi, Lekki, and Banana Island) have retained their collective identity as the home of the rich and the powerful.

These residential areas for the wealthy carry with them a genealogy of exclusion. The high-brow areas of today���s Lagos, Victoria Island, Ikoyi, and the Government Residential Areas (GRAs) were almost exclusively reserved for the bungalows of colonial officers in pre-independence Lagos. With the advent of self-determination, these locales represented access to capital and power for Lagosians with aspirational dreams of upward socio-economic mobility. Characterized by green spaces, cavalcades of trees, and a (rare) abundance of quietude, residency in one of colonial Lagos��� sought-after districts offered access to space, which was at odds with the architecture of the city at large. While Lagos became increasingly congested due to increasing migration, the sheer cost of land in places like Ikoyi limited the encroaching urban sprawl.

Detached houses and buildings one can actually walk between, novelties elsewhere in the city, continue to dominate in the playgrounds of the wealthy. This is not to say that areas such as Ikoyi and Victoria Island have not born witness to the cramped living conditions experienced by Lagos��� poor in recent years. As the numbers of those migrating to Lagos continue to grow and working-class residents are increasingly displaced by development projects, the boundary between affluent neighborhoods and poorer districts has become blurred. Yet the extraordinary range in what people of the city call home remains very much predicated on socio-economic status.

The scarcity of affordable housing in Lagos has seen an increase in the population of residents in makeshift slum settlements. Successive administrations have sought to evict residents of these areas, such as waterfront communities Tarkwa Bay, and Makoko, reported to be the world���s largest floating slum. As the number of homeless people in Lagos continues to rise, left to find makeshift shelter under the city���s bridges, state authorities have relentlessly sought to take land from the poorest, and at the expense of the city’s ecology. Over the last two decades, there have been ongoing efforts to dredge up and ���reclaim��� land lost to the Atlantic Ocean. An attempt to meet the high demand for accommodation for the affluent, these aggressive dredging projects have seen new settlements emerge on ���the island���, such as the ultra-expensive Eko Atlantic (launched by former American President, Bill Clinton) (https://www.ekoatlantic.com/latestnew...) and much of Lekki peninsula.

The last time substantive measures were put in place towards providing adequate housing for the underprivileged in Lagos was during the administration of Governor Lateef Jakande (1979-1983). Jakande, one of the foremost disciples of Obafemi Awolowo (a revered nationalist figure and post-independence government minister), enacted basic social-democratic policies in keeping with the political philosophy of his mentor. Jakande constructed over 30,000 housing units, known as low-cost estates, to cater to the demand for affordable housing by working-class families. These houses, still in existence today, are still popularly known today as ���Jakande houses.��� Another neologism in the collective lexicon of public housing in Lagos is ���face-me-I-face-you.��� Face-me-I-face-you is a pidgin expression used to describe a particularly popular architectural style of housing in various urban settlements across Nigeria, but predominantly in Lagos. The houses are utilitarian in design and affordable for low income earners. Their primary function is to accommodate as many tenants as possible within very minimal space. In design, the buildings usually have a tight cluster of one or two-room apartments with the entrance to each apartment facing that of another with a narrow hallway separating them. The kitchen, shower, and toilet spaces are usually communal for all the occupants of the building.

What does this architectural landscape mean for the implications of the coronavirus crisis? To say that space is a scarce commodity in Lagos, a luxury only available to a few, is not an original sentiment. Yet interim measures to stem the spread of the virus are predicated on the very access to space that so many Lagosians simply do not have. Public health strategies centered around social distancing and self-isolation are alien concepts, and moreover, practically impossible for the majority of the city���s residents. The irony of preaching social distancing to those living in face-me-I-face-you buildings exposes the crass nature of class disparities in Lagos. This reminder of the stark difference in the lived realities of Lagosians across the class divide seems to be what counter cultural musical rave-of-the-moment, Naira Marley, was alluding to when he crooned ���Owo wa l���Eko, awon kan wa okay���: there���s a lot of wealth in Lagos, quite a few are living very well. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3nhO6...)

As of June 30, 2020, Nigeria has reported 25,000 confirmed cases of coronavirus, and 573 deaths stemming from the physiological effects of COVID-19 (https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/). A high proportion of these cases are in Lagos state. On March 30, 2020 the neighboring state Ogun and the national capital Abuja were placed under lockdown. Although such measures are now being eased, the lingering restrictions and calls for social distancing disproportionately impact those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

Narratives around the alleged earliest cases of coronavirus transmission in Lagos only serve to further underscore the intersection of class and health amid the pandemic. It is said that on March 10, 2020, members of the Lagos-centric affluent class trooped to London to attend the 80th birthday celebration of Nigeria���s High Commissioner to the UK and Northern Ireland (and retired Supreme Court judge), George Adesola Oguntade. This party took place at the London Hilton Hotel on Park Lane in Mayfair, one of the most expensive areas in London, and one of the earliest areas in the UK to see serious transmission of the coronavirus. Some of Oguntade���s guests then returned to Lagos shortly after the celebration. For everyone else who missed out on the revelry in London, it was televised locally, thanks to the Bisi Olatilo Show���a television program that caters to members of Nigeria���s elites by showcasing special events they are involved in. The Nigerian dailies shortly after began reporting that two individuals who attended the London party died of the coronavirus afterwards (https://punchng.com/london-party-atte...). Around the same time, reports confirmed that the late Abba Kyari (https://africasacountry.com/2020/05/t...), President Buhari���s chief of staff (whose medical report had to be sent to Nigeria by his doctor in St. John���s Wood) and other politicians had contracted the virus. The subsequent public response unsurprisingly invoked both some degree of schadenfreude, and the initial popular perception of the coronavirus as the ���rich man���s disease.��� (https://www.lrb.co.uk/blog/2020/march...)

While not an epidemiological correct assertion, there is an unintended sociological rightness to this perception. It could be argued that the rich of Lagos who comprised the first known group of carriers of the coronavirus across Nigeria are now also best placed to avoid infection by virtue of their access to space. In a city where the large majority of low-income earners are employed within the informal economy, working menial jobs, the imposition of lockdown measures by the government has brought untold hardship. For many, the prospect of missing a day of work could result in nothing short of starvation. And, for the thousands who live underneath the city’s bridges, and the millions crammed in face-me-I-face-you houses across Lagos, social distancing or self-isolating is an option that has never been on the table for them in the first place.

July 10, 2020

Nothing to write home about

UN Security Council, 2015. Image credit Eskinder Debebe for UN Photo via Flickr CC.

After a second round of votes, Kenya beat off Djibouti to become one of five new non-permanent members of the UN Security Council in June 2020. The Kenyan government asserted that this new role would give Africans the opportunity to shape the global agenda, but, in view of the governance record in Kenya and at the UN Security Council, can we expect anything but the militarized status quo?

This post is from our partnership between the Kenyan website The Elephant and Africa Is a Country. We will be publishing a post from their site regularly, curated by our Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

The Kenyan government has been congratulating itself for securing a seat at the United Nations Security Council, perhaps believing���mistakenly���that such a ���privilege��� will somehow allow it to influence security issues affecting the African continent and will bestow on Kenya some kind of legitimacy that it did not enjoy before.

After Kenya was voted into the Security Council last month (after beating Djibouti in a second round of voting), the country���s Foreign Affairs Cabinet Secretary, Rachel Omamo, stated: ���Kenya will [now] have an opportunity to shape the global agenda and ensure that our interests and the interests of Africa are heard and considered. We now have a voice at one of the most important decision making forums.���

Kenya has now joined a long list of countries that eventually held membership in the Security Council, which is rotational except for the five countries that have permanent seats and veto-holding power, an arrangement that was made by the victors of World War II, who assigned themselves permanent status in the Council, ostensibly because they could be most relied on not to start another world war. The Council consists of 15 members, of which 10 are rotational non-permanent members elected for two-year terms. The non-permanent members may have a say in decisions made by the Security Council, but the ultimate decision rests with the five permanent veto-holding members, namely the United States, Britain, France, Russia, and China ���also known as the P-5.

The UN Security Council is not a club of equals. The ten non-permanent members of the Council do not pose a serious threat to the P-5, though membership does give these countries the illusion of being influential. In fact, one might even say that Security Council resolutions amount to little, and are acted upon only if all of the five permanent members agree on them unanimously. Disagreements within the P-5 can stall and even stop resolutions and decisions from being implemented.

So non-permanent status has little or no impact on important security-related decisions. The only countries whose opinions matter are the P-5. And the P-5 can make unilateral decisions with only cursory or tokenistic reference to the non-permanent members. So, in essence, nothing moves at the Security Council without P-5 approval.

Let me give you just a few examples of how ineffectual occupying a non-permanent seat in the Security Council can be.

The Security Council did not intervene in Rwanda to prevent a genocide

Rwanda was elected as a non-permanent member of the Security Council in 1994, the very year a horrific genocide took place in that country. The UN Security Council did little to prevent the genocide that ravaged the country and left at least 800,000 people dead. There is speculation that France (a P-5 member) did not want to interfere in the conflict; in fact, Rwanda���s president Paul Kagame has often accused France of being party to the genocide, a claim the latter has denied.

On its part, the US had a hands-off approach towards conflicts in Africa, having burnt its fingers in Somalia the previous year when 18 American soldiers were killed in Mogadishu during a so-called humanitarian operation, and so it looked the other way when Rwandans were being slaughtered. Meanwhile, Rwanda, the non-permanent member, sat back and watched the genocide unfold before the world���s eyes.

So if the role of the Security Council is to prevent crimes against humanity and war crimes and to promote peace, why is it that it failed miserably in preventing mass killings in a small African country? In fact, why did the UN���s Department of Peacekeeping Operations, which takes instructions from the Security Council, withdraw troops from Rwanda just when the country needed them most? And why did Kofi Annan, the head of UN peacekeeping at the time, order Rom��o Dallaire, who was in charge of the peacekeeping mission in Rwanda, to not to take sides as ���it was up to the Rwandans to sort things out for themselves���? (Annan later explained to the journalist James Traub that ���given the limited number of men Dallaire had at his disposal, if he initiated an engagement and some were killed, we would lose the troops.���)

In his book Shake Hands with the Devil, Dallaire talks of being extremely frustrated with his inability to convince the UN in New York to allow him to take actions that could have saved lives, if not prevented the genocide from taking place in the first place. In fact, prior to the genocide, when Dallaire informed his bosses that militias were gathering arms and preparing for mass killings, ���the matter was never brought before the UN Security Council, let alone made public���, according to the writer David Rieff, author of A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis.

The UN���s tendency to flee a country experiencing conflict or disaster is very common, as many Rwandans will attest. As g��nocidaires roamed freely in Rwanda, UN officials were busy packing their bags and catching chartered flights to neighboring countries. And the UN Security Council members, including Rwanda, remained mum.

The UN Security Council���and by extension, the UN as a whole���has lost its moral authority over other human rights issues as well. For example, at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests in New York (where the UN Secretariat is based), Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary-General, issued a memo to all UN staff asking them to refrain from participating in the demonstrations, ostensibly because as international civil servants, they were expected to remain apolitical and neutral. Maina Kiai, the former UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Assembly, condemned the Secretary-General���s directive, saying it was ���conflating the right to protest and racial equality with political partisanship.���

The Black Lives Matter protests occurred when the US was experiencing a rise in COVID-19 cases and deaths. The pandemic, which has the potential to become an international security issue (economies that suffer high levels of unemployment and inequality tend to generate disaffection and political unrest, which can sometimes result in armed conflict), has yet to be discussed at the Security Council.

The Security Council did not impose sanctions on the US and Britain for going to war with Iraq

The UN Security Council did absolutely nothing to prevent the US and Britain from going to war with Iraq in 2003. In fact, the US went ahead and invaded Iraq in March of that year shortly after making a rather unconvincing argument at the Security Council that Saddam Hussein was harboring weapons of mass destruction. (No such weapons were found in Iraq.) Yet no member of the Security Council (except France, which made an impassioned plea against the war) had the clout to force the US and Britain not to go to war.

Even though the then UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, declared the war ���illegal���, as it did not have the unanimous approval of the Security Council, there was nothing much he could do. And despite widespread anti-war protests around the world, President George Bush and Prime Minister Tony Blair went ahead with their misguided plan, which some estimate cost more than 600,000 Iraqi civilian lives. Further, the Security Council did not vote to impose sanctions on the US and Britain for waging an illegal war for the obvious reason that the countries waging the war were part of the P-5.

Ironically, but not surprisingly, a decade earlier, in 1991, the Security Council had imposed sanctions on Iraq for invading and annexing parts of Kuwait.

The Security Council has failed to protect civilians caught in conflict

Now let���s go to peacekeeping, the raison d�����tre of the Security Council. Currently there are 13 UN peacekeeping missions around the world, mostly in African countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mali, South Sudan, and Western Sahara. However, as the case of Rwanda shows, there is little evidence that the presence of peacekeepers significantly reduces the threat of conflict in these countries or protects civilians.

The UN���s largest peacekeeping mission is in the DRC. Since 1999, MONUSCO, the UN���s stabilizing mission in the DRC, has deployed thousands of troops to the country. Yet the DRC, arguably the world���s most mineral-rich country, remains the site of much poverty, conflict, and human rights abuses as militias and the Congolese army fight to control mining areas and extract taxes.

Human rights organizations have for years raised the alarm on human rights violations, including rape, committed by both the army and armed groups, but the violence and abuse doesn���t seem to stop. It is estimated that millions have died as a result of resource-based conflicts in the country. The mineral-rich eastern part of the country has also been described as ���the rape capital of the world���, where sexual violence is systematically used as a weapon of war.

The question arises: Despite a large presence of peacekeeping troops in the DRC, why are civilians still not safe? Could it be that some peacekeepers might in fact be party to the conflict? Scandals involving the illegal sale of arms by UN peacekeepers have been reported. In May 2007, for instance, the BBC reported that in 2005 UN peacekeeping troops from Pakistan had been re-arming Congolese militia (whom they were supposed to be disarming) in exchange for gold. A Congolese witness claimed to have seen a UN peacekeeper disarm members of the militia one day only to re-arm them the following day. The trade was allegedly being facilitated by a triad involving the UN peacekeepers, the Congolese army, and traders from Kenya.

UN peacekeepers in conflict areas have also been reported to have sexually abused or exploited populations they are supposed to be protecting. An investigation by the Associated Press in 2017 revealed that nearly 2,000 allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation by UN peacekeepers had been made in troubled parts of the world. (This number could be a gross underestimation as the majority of victims of sexual exploitation or abuse do not report their cases.)

Peacekeeping missions have also been reported to have underplayed the scale of a conflict in order to prove that they are doing a good job of keeping the peace. When Aicha Elbasri, the former spokesperson for the African Union-United Nations Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), reported that UNAMID and the UN���s Department of Peacekeeping Operations routinely misled the media and the UN Security Council about crimes, including forced displacement, mass rape and bombing of civilians, committed by Sudanese government forces in Darfur, the UN failed to investigate her allegations. It only carried out an internal inquiry after she resigned in protest in 2013 and when the International Criminal Court (ICC) ordered the UN to do so; to this day the UN has not made the inquiry���s findings public, contrary to the ICC���s demand that such an inquiry be ���thorough, independent and public.���

Elbasri later publicly released thousands of emails, police reports, internal investigations, and diplomatic cables that exposed the failure of the UN to protect millions of Sudanese civilians under its protection.

The P-5 have a vested interest in the military-industrial complex

It is not lost on many people that the P-5 have a vested interest in wars in faraway places because wars keep their military-industrial complexes running. The weapons industry is huge, and countries that supply arms and military equipment would not like the threat of war to fade away.

When wars occur in far-off places, arms manufacturers have a field day. Wars in former French colonies in Africa keep France���s military industrial complex well-oiled. Wars in the Middle East are viewed by British and American arms manufacturers as a boon for their weapons industries. If there were no wars or civil conflicts in the world, these industries would not be so lucrative.

It was no surprise then that Donald Trump���s first official foreign visit was to Saudi Arabia, which has been buying arms worth billions of dollars from the US for decades. Arms from the US have kept the Saudi-led war in Yemen going. The connection between arms sales and the arms manufacturers��� silence on human rights violations committed by countries which buy the arms became acutely visible during that visit. This also explains Trump���s lukewarm response to the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

The Security Council has put no pressure on the US���which contributes almost a quarter of the UN���s budget���to rethink its policy towards arms sales to Saudi Arabia and other countries. On the contrary, the UN���s campaign in Yemen, for example, is not about ending the war, but raising donations for the millions of Yemenis who are suffering as a result of Saudi-led bombings.

Make the Security Council more representative

The UN Security Council was established 75 years ago at a time when countries went to war with each other, and when Western powers had experienced severe physical and economic destruction and the loss of millions of lives. However, today���s most deadly wars are being waged by insurgents or terrorist groups, such as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, which have become transnational. The Security Council is not equipped to handle this new threat. New forms of international cooperation are required.

If Kenya wants to have real influence in the UN Security Council, it should lobby for the Council to be expanded and be made more representative and democratic. Countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (regions that hold the majority of the world���s population), must demand to be included as permanent members. Permanent membership should be allocated to those countries that have no vested interest in the weapons industry and which have not waged war in other countries since the Security Council was established in 1945���countries that are genuinely committed to world peace. No country should have veto powers. Maybe that would make membership in the Council more democratic and meaningful.

However, even if this happens, membership might not amount to much as long as the UN���s purse strings are controlled by a few rich and powerful countries which can sway other countries to vote in their favor and as long as some members have an interest in ensuring that their military-industrial complexes remain operational for a long time. Kenya, being a donor-dependent country, can therefore easily be influenced by rich donor countries. This is how the world, including the Security Council, operates.

July 9, 2020

Moving forward while standing still

Mogadishu. Image credit Mohamed Duale.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Somalia���s independence from Britain and Italy, a milestone that is weighing heavily on the minds of Somali people around the world. Somalia���s descent into civil war and state collapse in the early 1990s dealt a severe blow to the dreams of an independent and unified Somali homeland. This was reinforced by Western hegemonic narratives which have characterized Somalia as the quintessential ���failed state.��� In the past decade, the ���failed state��� discourse has somewhat shifted, aided by the ���Somalia rising��� counter-narrative following the installment of two consecutive internationally recognized governments. Countless diaspora Somalis have since returned from neighboring and Western countries to contribute to national reconstruction.

However, women have been excluded from meaningful participation in rebuilding Somalia. Somali politics is dominated by older men from the Western diaspora and local elders. A festering schism between diaspora (qurbojoog) and ���stayees��� (qoraxjoog) has evoked anxieties about citizenship and belonging. Stayees, resentful of diaspora efforts to ���save��� Somalia, have contemptuously labeled returnees as dayuusbora, or ���ill-mannered diaspora,��� a clever play on words that exasperates the tension.

Fouzia Warsame is a Somali-Canadian returnee who has played an important role in rebuilding the country���s first and only public university. As Dean of the Faculty of Education and Social Science at the Somali National University, she is one of the most prominent academics in the country. I first met Fouzia in 2018 at a York University workshop on refugee education where she invited me to visit Somalia, the country I had fled and not seen since childhood. I took up the offer and returned ���home��� in December 2019. In Mogadishu, I was welcomed by Fouzia and her team of dedicated educators and students.

Fouzia notes that the tensions between diaspora and stayees create an added difficulty for professional diaspora women as patriarchal norms seek to maintain ���a woman���s place within Somali society.���