Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 174

May 31, 2020

The class character of police violence

Oakland, USA. Image credit Thomas Hawk via Flickr CC.

Last week, the world watched the grotesque murder of George Floyd, an unarmed black man in Minneapolis, a city in the American Midwest. Floyd, who, despite being compliant in his arrest, helplessly succumbed to his death after a white police-officer knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes despite his cries of being unable to breathe, and protests from frightened onlookers. This happens on the heels of another incident in New York, where a petty dispute between a black man and white woman over her unleashed dog in a park escalated to her calling the cops and falsely claiming that ���an African-American man��� was threatening her. (White people calling police on black people in the US is deemed ominous as it usually results in their death.) After all this, the nature and origins of police brutality against black Americans is once again in the spotlight.

These events have rightly evoked uproar across the world, and South Africans and other Africans on the continent have joined the online chorus expressing solidarity with protesters in Minneapolis, who are leading what feels both like the revival of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as perhaps the beginnings of a bigger uprising against the general inequalities that have characterized the COVID-19 pandemic. So far, 100,000 Americans have been killed by COVID-19, and 40 million Americans have become unemployed.

It is easy, amidst all this, to forget that South Africa is experiencing its own instances of horrific violence from law enforcement agents. The most publicized of these, is the murder of Collins Khoza in the Alexandra township by members of the South African military and the Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department. Even after Khoza���s family successfully took them to court, the soldiers implicated have been exonerated by an internal investigation conducted by the South African National Defence Force, who were also ordered by the court to publish a set of guidelines on how to engage the public during the pandemic. Since South Africa went under a national lockdown in March to curb the virus��� spread, there has been little public anger expressed at the incidences of misconduct committed by South Africa���s security forces, who have killed more than ten people so far. In fact, a lot of people initially cheered their harsh and punitive approach as a kind of necessary evil required to contain the virus��� transmission (the indictment of 230,000 people for breaking lockdown regulations was either celebrated or ignored). Why was there little outrage over police violence at home?

It might first have something to do with the role of social media. Generally, under consumer capitalism, there exists a tendency in our media-saturated society to render all political events as media commodities, constructing a landscape where, as the social theorist Jean Baudrillard once explained, the nature of the real is preceded and determined by its mediatized representation. Society becomes predisposed to a fascination with spectacular and immediate images of violence due to their overproduction���in Baudrillard’s time it was wars in the Middle East, terrorism and football riots��� in ours, it is images of police brutality. Their circulation exists first and foremost for their consumption, and rather than induce sustained action, they often trigger outbursts of anger which quickly dissipate into apathy. This moment will hopefully prove the exception.

So, that Khoza’s homicide lacks footage, effectively excludes it from the market of this attention economy, worsened as the majority of life is migrated online in the era of physical distancing. This was also the case before the pandemic with the countless other incidents of police murder in this country, which per capita, are actually three times higher than in America, a country five times our size. But America’s lasting cultural hegemony means that South Africans routinely import a distinctively American sensibility when it comes to understanding police violence at home, one with anti-black racism at its center. Yet this framework quickly reveals itself to be ill-suited to understanding the dynamics of our situation, given the fact that unlike America, we are a majority black country. And so it is almost always the case that both the perpetrators of this violence, as well as its victims, are black. It cannot simply be, as it is often decried in the United States, that our law enforcement agents are uniformed white supremacists. What else is at play here?

Consider that throughout the lockdown, the majority of the military and police’s presence are in townships and informal settlements. People were right to express surprise that the police, after years of neglect of these communities where dire social conditions increases the rate of crime and disorder, could now suddenly arrive in full force. This contradiction uncovers what many historians have previously pointed out��� that the invention and subsequent function of the police as a professional body of law enforcers, is not as a response to crime, but as a response to the threat that collective action poses to elite rule and the unequal social arrangements which undergirds it. Through rebellions, strikes and other forms of resistance, masses have throughout history contested their domination and exploitation by the ruling class. It is the threat from the masses that means they need to be permanently contained, and this remains the enduring imperative of policing practices.

South Africans in informal settlements and the rural countryside are that part of the population deemed most threatening. Capitalism has made them superfluous to its present profit-making purposes, excluding them from the formal economy and condemning them to a life of mass unemployment, underemployment and indigence. The South African state was mindful of how the lockdown suspended the activity of the tenuous informal economy of which most are dependent. It does not care that the range of protections it introduced to offset worsening poverty are meager, and that it lacks the competent administration to implement them effectively (the government has only managed to successfully pay 9 people a $20 monthly COVID-19 distress grant for the unemployed, of which up to 15 million people qualify). These were never introduced in a sincere effort to sustain livelihoods, but rather to keep people subdued, with the military and police on standby just in case the masses decide that they have had enough of not having enough���as protesting miners in Marikana did in 2012. Back then, after 34 miners were massacred by the police, there were no mass, society-wide protests. That President Cyril Ramaphosa, who played a significant role in those killings, is now mostly warmly embraced by the South African public, shamefully summarizes what the legacy of Marikana has been.

The best example of this South African middle class hypocrisy, comes through one of its most cherished exports, the comedian Trevor Noah. As the host of the Daily Show, he is now being praised for his commentary about American police brutality. However, it wasn���t long ago when he described the murderous action taken by the police at Marikana as being appropriate. ���Which strike has ever ended with teargas,��� he joked.

A more ready identification with the victimization of black Americans then, reveals an unwillingness to confront the class character of police repression. It betrays, in other words, a veiled attachment to the prevailing social order and its continued reproduction, or at least a lack of interest in meaningfully challenging it, since the overriding concern for victims of police brutality is simply that they are black, not that they are black and poor. Black middle class South Africans feel culturally closer to African Americans (much like white South Africans imagining themselves as extensions of Europe, especially Britain, rather than “African”), and aspire to the cultural leadership and metropolitan chic that they have come to globally represent���despite the fact that this ingratiation is unrequited, and is instead usually met with indifference or cultural fetishism (see the film Black Panther), all expressive of a typically American contempt for Africans.

On the flip side, poor and working-class black South Africans, have more in common with their American counterparts��� black, white or latino���than they do with the middle or upper stratas in either country. Indeed, through their shared experiences of economic oppression and state repression, they have more in common with their counterparts in Kenya or India, where police crackdowns during lockdown have not been dissimilar to those here but are underreported still, in Palestine, where Israeli Apartheid continues to harden, or even France, where it wasn���t long ago that the police violently suppressed the gilet jaunes. Nevertheless, spurred by the media visible protests emblazoning America, a cohort of Twitter personalities, NGO professionals and media commentators, are now trying to reconstruct the resistance to police brutality at home as a kind of domestic Black Lives Matter moment.

The American political scientist Adolph Reed has been foremost in critiquing the ways in which Black Lives Matter, emerging fist as a set of protests against police brutality in Ferguson in 2014, has since failed to cohere into a concrete social movement. Approaching the problem of police violence in a mostly race-reductionist way, the problem becomes that it at best can only achieve a set symbolic goals���the chanting of the slogan at gatherings, the memorialization of those killed by the police��� but struggles to develop a coherent vision for social transformation. The most forceful of BLM���s proposals, came through another slogan, that to ���abolish the police.��� What this means in practical terms, is a range of different things, such as reimagining policing as a public good, or gradually disinvesting from it so as to dismantle it altogether. What all of these miss, however, is that so long as there is a capitalist state entrenching private property relations, there will always be some kind of security apparatus to defend it with racism coded into its logic of operation��� it will prevail no matter how hard you try to reform it in order to give it a more human face, or it will simply become privatized, as is very much the case in South Africa already.

The profound explosion of rage in America���for now, knee jerk, and inchoate, will no doubt be mimicked elsewhere as restive populations reach their breaking point. It must be embraced, and channeled towards the objective of sustained organizing for a better world beyond capitalism. When the dust settles and the wreckage is before us, then the real work starts. It was Fred Hampton, the radical Black Panther who himself was first harassed by local police and then brutally assassinated by the FBI, who said, ���We don���t think you fight fire with fire best, we think you fight fire with water best. We���re going to fight racism not with racism, but we���re going to fight with solidarity. We say we���re not going to fight capitalism with black capitalism, but we���re going to fight it with socialism.��� We have to keep fighting, and know not only what it is we are fighting against, but also what we are fighting for.

We cannot reform ourselves out of the times we are in

A protestor in Minneapolis, USA. Image credit Lorie Shaull via Flickr CC.

It is a sad day when Target, a corporation, releases a statement more in touch with the reality of being black in America, than the black former President Barrack Obama. In fact the most hard hitting words in his statement, ���’the knee on the neck’ as a metaphor for how the system so cavalierly holds black folks down, ignoring the cries for help��� are arguably not his, as he is quoting a friend.

Meanwhile, Target in their own words state categorically that, ���The murder of George Floyd has unleashed the pent-up pain of years, as have the killings of Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor. We say their names and hold a too-long list of others in our hearts.��� And, where Obama signals that not all cops are bad, his way of saying there are good people on both sides, the Target statement does not mention the police at all. For those who might have been hoping for a more progressive post-presidency Obama, it is time to simply recognize him as the first black president who gave us hope and leave it at that.

Both statements however do not go enough in understanding that, to put it bluntly, the United States is fucked unless we call for and find radical solutions. They don���t speak to just how weak the fa��ade of democracy and how hollow the claim of being the ���richest nation on earth��� is. The US national debt stands at $25 trillion with about 10% of that being owned by China and Japan. Internationally, the US is becoming more isolationist, withdrawing from international treaties and organizations the latest one being the World Health Organization, and this at a time of a global pandemic. In effect, it is becoming a colossal, irrelevant giant with a military-industrial-complex to match. And, without diplomacy more war is the likely recourse.

43 million people in the US were living in poverty before the pandemic. Jobless claims stand at $40 million decimating the much touted middle class���which was made up of millions of people living from pay check to pay check, in mortgaged homes, and driving loaned cars. To put it another way, the dream never really existed for black people, and it had long died for millions of others. Racialized incarceration rates, always a major concern, and amongst the highest in the world, are now turned deadly by the pandemic.

There are 100,000 COVID-19 deaths, and because we have a government that delayed locking down and is now opening up the country for business without doing the minimum preparation of contact tracing and testing, we can be sure that without a vaccine, more people will die.

And in all these examples, black people have been doing most of the suffering and in today’s context, most of the getting sick and dying.

It is a terrible and worsening economic system, except for the wealthy, that has been driven by racist ideology. White supremacy is the opium of white people. Even the liberals and those on the left are beneficiaries, in the same way the North was benefiting from slavery in the South���money did not respect state borders, trade continued, and money was kept in banks in the North. They need to take responsibility for slavery, the very foundation on which our present racist society rests. No more saying my great-grandparents were not slave owners and/or I am not a racist and therefore it is not my concern.

When US Vice President, Mike Pence, tweets, ���We condemn violence against property or persons��� and in that order, he means white property and white persons. Having previously refused to acknowledge police racism and violence, he is in effect defending his soldiers out in the frontlines of the war against black people���the predators, the thugs, welfare queens and looters. On looting, I have only two words to say, it James Baldwin who said, ���you���re accusing a captive population who has been robbed of everything of looting. I think it���s obscene.���

In a sense I can understand why the police sometimes seem perplexed when people protest, after all they are just doing the job the government has tasked them to do. But as agents and enforcers of a racist state, they must be protested, at least so they can enforce their mandate without shooting and strangling black people to death. So at least we can at least breathe, and live and work to dismantle the system that makes a racist police its foot soldiers.

Given the radical times we are in, both the vacuous and vicious nature of American capitalism and the failure and racism of the Trump regime have to go. Given how deep the hole we are in is, to crawl out there is no real difference between Obama, Trump, or Biden. There was a vast difference between Sanders or Warren and Trump. But the fear that Sanders could not win led us to picking the safer bet in Biden. And for that choice black people, especially, will continue to suffer the most.

For Karl Marx, looking back on revolutionary France and its failure to transform the lives of workers, part of the problem was the impossibility of making change as if the past did not matter. He argued that ���Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.��� To end racism, we will have to change the structures from which it draws its mandate, and get rid of liberal and right-wing politicians who give it oxygen while we are being asphyxiated.

We cannot reform ourselves out of the times we are in.

May 29, 2020

Hip hop futures in Kenya

Khaligraph Jones via Instagram.

Not much is known about the Kenyan hip hop scene outside the country, with Oduku arguing that it has “been nothing but a

graveyard of mixtapes, while offering a glimpse of spirit and experimentation.” But, Testimony 1990, the recent album by Kenya-based Khaligraph Jones offers some optimism since it is an intimate chronicle of the vast challenges besetting youth in Nairobi and across the continent.

This is an edited republication from our partnership with the Kenyan website The Elephant. We will be publishing a series of posts from their site every week, curated by Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

A talent emerged with a vociferous, shrill and piercing cry deep in the heart of Kayole, Nairobi on June 12, 1990. It was an uncertain time. Agitations for multiparty democracy clouded the air amidst arbitrary detentions, torture, and killings. Still, a mother���freed from the listlessness of a third trimester���rocked a plump newborn. As the cries of Robert Ouko���s assassination tapered, it was only fitting that the mother in Kayole thought it wise to name her new hope���Brian Ouko Robert���perhaps as a silent resistance against the dictatorial regime. I do not know. I have not asked. But I know we use names to resist erasure.

Brian Ouko Robert���aka Mr. Omollo aka Khaligraph Jones���was welcomed by a troubled country of barely 20 million people. Exactly 28 years later, this baby released a debut album, Testimony 1990, and gave us a chance to look back not only at this child who has now become a man, but at a country whose population, just like its troubles, has doubled.

Testimony 1990

Testimony 1990 is a testimony of Khaligraph Jones���s life, his troubles, and those of his country. Khaligraph is not an overnight celebrity. His success is not the product of the modern viral phenomenon, where the gods of the internet choose to crown a new artist with a million views on YouTube for some mumble rap. He is not the product of accidental fame but of tenacity.

His interest in music began at an early age in elementary school, and at 13 his love of music was visible and palpable. It helped that his older brother loved music too. Together they released their first rap track in 2004.

But Kenya has one of the most unforgiving hip hop music ecosystems. There are only two options for an artist: have the right connections and money, or be willing to toil for years through venom-infested underground rap battles to gain recognition. Khaligraph made his bones the hard way.

In 2009, The Channel O Emcee Africa tour, sponsored by Sprite, came calling in search of the premier freestyle MC. They dubbed it the Channel O MC Challenge. At the heart of the competition was the desire to initiate awareness of ���street life��� as a sociocultural context captured by local hip hop music. Khaligraph, then a 19-year-old lad, laced his gloves and threw himself into the ring.

It was simple: get to the stage and showcase your lyrical prowess, spitting spur-of-the-moment rhymes, either acapella or on beat boxing, or you could prompt the judges to give you a topic if you thought you had mad skills. Eliminations pitted Point Blank vs Khaligraph for the big prize: $10,000. That is, 780,000 Kenya shillings then. Point Blank floors Khaligraph. Everybody agrees. But this would mark the beginning of Khaligraph���s ascendancy. In that list of 10 MCs, 10 years later, none has been as industrious as Khaligraph. None can challenge him to the throne of Kenya���s top MC today. None dominates the airwaves like he does today. Testimony 1990 is a testament of his focus, the fire lit that Saturday night in 2009. It is warm and optimistic, does not lament and chronicles contemporary challenges besetting a young man in Nairobi. It is not broody lyricism, perhaps because Testimony 1990 comes from an artist who has achieved remarkable success. At the same time, it is not a chronicle of his status now, as an artist, but a sort of reflection of a past lived through, of battles won. It is unlike the legendary Kalamashaka with their gritty rhymes and the personal catastrophe of jumping a thousand hurdles and still not making it to the Promised Land.

Hip hop as a political force

Hip hop is inherently political. With its roots traced to the militant spoken word by groups such as The Last Poets and The Watts Prophets, hip hop has always delivered political missives from the front line. In the 1980s, hip hop chronicled and reacted to the policies of US President Ronald Reagan, which called for widespread tax cats, decreased social spending, increased military spending and the deregulation of domestic markets. Reaganomics led to massive cuts to social programs and widened income inequality, consequences which were particularly worse for African American families. Life outcomes were no better in Kenya. The economy collapsed from a nominal GDP of 7.265 billion USD in 1980 to 6.135 billion USD in 1985. Even worse, Kenya became one of the first countries to sign a Structural Adjustment Program loan with the World Bank. The trade liberalization experience was a gross disappointment and threw the early 1990s into great uncertainty.

The economic devastation that resulted created fertile ground for the emergence of one of the most influential hip hop acts in Kenya, Ukoo Flani, in 1995. The group���s music flourished as a form of protest���authentic, gritty, and startling in its boldness. Ukoo Flani historicized slum life, using Dandora as a poster child for the effects of endemic corruption, breakdown of public service delivery, rampant crime and police brutality, and immense suffering during the Moi dictatorship. Hip hop, belted out in Sheng���to escape the censor of the police state���became a tool for the disenfranchised young men in the sprawling ghettos to voice their dissatisfaction and dissent.

Over the past two decades, hip hop has oscillated from social and political commentary to easy-going party jams, or a mix of both. In Kenya, artists, particularly those of the underground, continued to rail against urban violence and dysfunction, police brutality and extrajudicial killing of young men in slums. Khaligraph���s music attempts to carry both social and political commentary and easy-going party jams. While a majority of his tracks are fashioned for the club, a few explore social and political themes.

The question of whether hip hop can become a political mobilizing force beyond the restrictions of personal protest is an old one. The mixing of commercial success and socially-conscious hip hop is what has made it possible for a commercial artist such as King Kaka to release ���Wajinga Nyinyi��� (2019)���one of the most impactful political protest tracks in recent years. It is not that the track tells Kenyans what they don���t know; rather, King Kaka serializes what is discussed daily on social media, and what is splashed on the front pages of daily newspapers. The lyrics translate the dysfunctions of a nation���clothed daily in civil terms��� into the raw, unadorned, unpretentious language of the streets. #WajngaNyinyi tells Kenyans to stop being stupid and start holding the system accountable.

This is the music culture that Khaligraph grew into, one in which hip hop was broadcast news from the ghetto, the hood. Rappers repped their hoods. Ukoo Flani made Dandora the capital city of Kenya���s hip hop, decked it with rhymes depicting an unforgiving cityscape for adult males and a space of tough love as Zakah na Kah depicted in the eponymic ���Dandora L.O.V.E.��� However, for the most part, away from these pioneering hip hop albums of the late 1990s and early 2000s, Kenya���s hip hop scene has been nothing but a graveyard of mix tapes which, while offering a glimpse of spirit and experimentation, deny listeners the beauty of intention, coherence and completeness.

Moreover, there is a new legion of internet-born artists, genre-bending productions and visuals, serving digital native fan bases with exciting single tracks. Gengetone���perhaps the most significant development in Kenyan music in years���is already stealing the airwaves from maturing acts such as Khaligraph, Octopizzo, and King Kaka. But the new wave is characterized by explicit content, with song lyrics promoting violence and misogyny, and videos promoting the sexual objectification of women. However, as writer Barbara Wanjala notes: ���Kenyan artists have been experimenting to see what will capture the youth. The contemporary sound landscape runs the whole gamut, from songs that speak about debauchery to conscious lyricists rapping with conviction. Other artists straddle both worlds, producing output that has commercial appeal as well as tracks that are socially responsible.���

It remains to be seen whether, in addition to documenting, socio-politically conscious hip hop can engender political mobilization and drive political change in Kenya. Perhaps Wakadinali���s ���Kuna Siku Youths Wataungana��� (2020)���which explicitly calls on youth to organize, mobilize, and take political action���is an encouraging direction for the new decade. For now, the album Testimony 1990 is a condensed piece of work that offers us coherence, thematic focus, and a snapshot of the career progress of the artist.

Hip Hop futures in Kenya

Nairobi.

Khaligraph Jones via Instagram.

Not much is known about the Kenyan hip hop scene outside the country, with Oduku arguing that it has “been nothing but a

graveyard of mixtapes, while offering a glimpse of spirit and experimentation.” But, Testimony 1990, the recent album by Kenya-based Khaligraph Jones offers some optimism since it is an intimate chronicle of the vast challenges besetting youth in Nairobi and across the continent.

This is an edited republication from our partnership with the Kenyan website The Elephant. We will be publishing a series of posts from their site every week, curated by Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

A talent emerged with a vociferous, shrill and piercing cry deep in the heart of Kayole, Nairobi on June 12, 1990. It was an uncertain time. Agitations for multiparty democracy clouded the air amidst arbitrary detentions, torture, and killings. Still, a mother���freed from the listlessness of a third trimester���rocked a plump newborn. As the cries of Robert Ouko���s assassination tapered, it was only fitting that the mother in Kayole thought it wise to name her new hope���Brian Ouko Robert���perhaps as a silent resistance against the dictatorial regime. I do not know. I have not asked. But I know we use names to resist erasure.

Brian Ouko Robert���aka Mr. Omollo aka Khaligraph Jones���was welcomed by a troubled country of barely 20 million people. Exactly 28 years later, this baby released a debut album, Testimony 1990, and gave us a chance to look back not only at this child who has now become a man, but at a country whose population, just like its troubles, has doubled.

Testimony 1990

Testimony 1990 is a testimony of Khaligraph Jones���s life, his troubles, and those of his country. Khaligraph is not an overnight celebrity. His success is not the product of the modern viral phenomenon, where the gods of the internet choose to crown a new artist with a million views on YouTube for some mumble rap. He is not the product of accidental fame but of tenacity.

His interest in music began at an early age in elementary school, and at 13 his love of music was visible and palpable. It helped that his older brother loved music too. Together they released their first rap track in 2004.

But Kenya has one of the most unforgiving hip hop music ecosystems. There are only two options for an artist: have the right connections and money, or be willing to toil for years through venom-infested underground rap battles to gain recognition. Khaligraph made his bones the hard way.

In 2009, The Channel O Emcee Africa tour, sponsored by Sprite, came calling in search of the premier freestyle MC. They dubbed it the Channel O MC Challenge. At the heart of the competition was the desire to initiate awareness of ���street life��� as a sociocultural context captured by local hip hop music. Khaligraph, then a 19-year-old lad, laced his gloves and threw himself into the ring.

It was simple: get to the stage and showcase your lyrical prowess, spitting spur-of-the-moment rhymes, either acapella or on beat boxing, or you could prompt the judges to give you a topic if you thought you had mad skills. Eliminations pitted Point Blank vs Khaligraph for the big prize: $10,000. That is, 780,000 Kenya shillings then. Point Blank floors Khaligraph. Everybody agrees. But this would mark the beginning of Khaligraph���s ascendancy. In that list of 10 MCs, 10 years later, none has been as industrious as Khaligraph. None can challenge him to the throne of Kenya���s top MC today. None dominates the airwaves like he does today. Testimony 1990 is a testament of his focus, the fire lit that Saturday night in 2009. It is warm and optimistic, does not lament and chronicles contemporary challenges besetting a young man in Nairobi. It is not broody lyricism, perhaps because Testimony 1990 comes from an artist who has achieved remarkable success. At the same time, it is not a chronicle of his status now, as an artist, but a sort of reflection of a past lived through, of battles won. It is unlike the legendary Kalamashaka with their gritty rhymes and the personal catastrophe of jumping a thousand hurdles and still not making it to the Promised Land.

Hip hop as a political force

Hip hop is inherently political. With its roots traced to the militant spoken word by groups such as The Last Poets and The Watts Prophets, hip hop has always delivered political missives from the front line. In the 1980s, hip hop chronicled and reacted to the policies of US President Ronald Reagan, which called for widespread tax cats, decreased social spending, increased military spending and the deregulation of domestic markets. Reaganomics led to massive cuts to social programs and widened income inequality, consequences which were particularly worse for African American families. Life outcomes were no better in Kenya. The economy collapsed from a nominal GDP of 7.265 billion USD in 1980 to 6.135 billion USD in 1985. Even worse, Kenya became one of the first countries to sign a Structural Adjustment Program loan with the World Bank. The trade liberalization experience was a gross disappointment and threw the early 1990s into great uncertainty.

The economic devastation that resulted created fertile ground for the emergence of one of the most influential hip hop acts in Kenya, Ukoo Flani, in 1995. The group���s music flourished as a form of protest���authentic, gritty, and startling in its boldness. Ukoo Flani historicized slum life, using Dandora as a poster child for the effects of endemic corruption, breakdown of public service delivery, rampant crime and police brutality, and immense suffering during the Moi dictatorship. Hip hop, belted out in Sheng���to escape the censor of the police state���became a tool for the disenfranchised young men in the sprawling ghettos to voice their dissatisfaction and dissent.

Over the past two decades, hip hop has oscillated from social and political commentary to easy-going party jams, or a mix of both. In Kenya, artists, particularly those of the underground, continued to rail against urban violence and dysfunction, police brutality and extrajudicial killing of young men in slums. Khaligraph���s music attempts to carry both social and political commentary and easy-going party jams. While a majority of his tracks are fashioned for the club, a few explore social and political themes.

The question of whether hip hop can become a political mobilizing force beyond the restrictions of personal protest is an old one. The mixing of commercial success and socially-conscious hip hop is what has made it possible for a commercial artist such as King Kaka to release ���Wajinga Nyinyi��� (2019)���one of the most impactful political protest tracks in recent years. It is not that the track tells Kenyans what they don���t know; rather, King Kaka serializes what is discussed daily on social media, and what is splashed on the front pages of daily newspapers. The lyrics translate the dysfunctions of a nation���clothed daily in civil terms��� into the raw, unadorned, unpretentious language of the streets. #WajngaNyinyi tells Kenyans to stop being stupid and start holding the system accountable.

This is the music culture that Khaligraph grew into, one in which hip hop was broadcast news from the ghetto, the hood. Rappers repped their hoods. Ukoo Flani made Dandora the capital city of Kenya���s hip hop, decked it with rhymes depicting an unforgiving cityscape for adult males and a space of tough love as Zakah na Kah depicted in the eponymic ���Dandora L.O.V.E.��� However, for the most part, away from these pioneering hip hop albums of the late 1990s and early 2000s, Kenya���s hip hop scene has been nothing but a graveyard of mix tapes which, while offering a glimpse of spirit and experimentation, deny listeners the beauty of intention, coherence and completeness.

Moreover, there is a new legion of internet-born artists, genre-bending productions and visuals, serving digital native fan bases with exciting single tracks. Gengetone���perhaps the most significant development in Kenyan music in years���is already stealing the airwaves from maturing acts such as Khaligraph, Octopizzo, and King Kaka. But the new wave is characterized by explicit content, with song lyrics promoting violence and misogyny, and videos promoting the sexual objectification of women. However, as writer Barbara Wanjala notes: ���Kenyan artists have been experimenting to see what will capture the youth. The contemporary sound landscape runs the whole gamut, from songs that speak about debauchery to conscious lyricists rapping with conviction. Other artists straddle both worlds, producing output that has commercial appeal as well as tracks that are socially responsible.���

It remains to be seen whether, in addition to documenting, socio-politically conscious hip hop can engender political mobilization and drive political change in Kenya. Perhaps Wakadinali���s ���Kuna Siku Youths Wataungana��� (2020)���which explicitly calls on youth to organize, mobilize, and take political action���is an encouraging direction for the new decade. For now, the album Testimony 1990 is a condensed piece of work that offers us coherence, thematic focus, and a snapshot of the career progress of the artist.

May 28, 2020

Dear David Chang

Still from Ugly Delicious on Netflix.

��� Anthony BourdainTravel isn���t always pretty. It isn���t always comfortable. Sometimes it hurts, it even breaks your heart. But that���s okay. The journey changes you; it should change you. It leaves marks on your memory, on your consciousness, on your heart, and on your body. You take something with you. Hopefully, you leave something good behind.

The first season of the Netflix series, Ugly Delicious, drew considerable criticism for its lack of representation of women and African Americans. Honestly, only featuring black chefs on the fried chicken episode? Favoring male chefs and celebrities over female voices? What was the rationale for those decisions? But it seemed that the mistake had been recognized and would be addressed in future iterations of the show. At Recode���s 2018 Code Conference, Chang said that he had heard the criticism and promised that, if he were given a second season, he would ���be able to do it better.��� So, now season two is out and, in some respects, Chang did do better. ���Don���t Call It Curry��� may be one of the best episodes of culinary television that I have ever seen, focused heavily on female food writers and chefs in the Indian diaspora���including Padma Lakshmi, Priya Krishna and Sonia Chopra���and overlooked culinary masters like the late Floyd Cardoz. Kudos! But there are still some issues that could be addressed to make the show more impactful and relevant.

Is Ugly Delicious insightful? Often. Star-studded? Absolutely. Balanced? That���s hard to say. This show is about food from Chang���s perspective, and that outlook is inarguably shaped by the foods he himself is known for. The food he ate while working in Tokyo, the Korean meals his family made, the genius food that he created for Momofuku and his other successful restaurants. Of course Chang���s show is going to be heavily tilted toward Asian cuisine���his personality and his palette have been irrevocably shaped by these influences and his perspective is one we haven���t often seen in contemporary food media. But this is a man who begins this show by saying that he wants to learn about why food is delicious���and I think it���s difficult to talk about why food is delicious without considering why African food is delicious. I���m a huge fan of Chang and the show. None of this is intended to take away from the work he���s done to bring attention to underrepresented global cuisines. At the same time, Ugly Delicious focuses on the interconnections of peoples throughout the world through the prism of food. What better microcosm of that story than the impact of African food on the rest of the world, and vice versa?

On more than one occasion, Chang���s explorations have taken him within a stone���s throw of this exact subject matter, not only literally, but also metaphorically. In season one, in the episode ���Shrimp and Crawfish,��� Chang explores the Viet-Cajun phenomenon, visiting Vietnam, New Orleans and Houston. His visit to Houston placed him just blocks away from one of the most vibrant African immigrant food communities in the US, as evidenced in Marcus Samuelsson���s recent episode of No Passport Required. Of course, Chang���s episode focused on the intersections of Vietnamese and Cajun food traditions, and an African perspective on that may not have fit. But Houston is a true melting pot, and the African immigrant population in that city has profoundly shaped the food culture. You wouldn���t know that from watching this episode. In the season one episode on fried chicken, Psyche A. Williams-Forson, the author of Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs, tells Chang that West African slaves had a tradition of cooking chicken in palm oil, which barely registers with Chang before the episode moves forward to another subject. And, in the aforementioned brilliant episode on curry, Chang chooses to use the example of Herta Heuwer and currywurst to illustrate the global reach of curry flavors. How many African cuisines could he have explored that have been fundamentally shaped by the integration of Indian flavors? Bunny Chow in Durban, South Africa? Curry dishes in the Caribbean?

In season two, episode three, ���Steak,��� Chang explores global approaches to eating steak���or, rather, American, Asian, European and Australian approaches to eating steak. In Sydney, on Danny McBride���s recommendation, Chang visits Macelleria, basically a bourgeois shisanyama. What a missed opportunity to talk about how people eat steak in these non-white spaces. In the second season of a show that has visited every other continent save for Antarctica, you can���t help but wonder if the oversight is intentional or if Chang and his production team really have no knowledge of Africa at all.

However, Chang is aware that Africa exists ��� or, at least, South Africa and Morocco. In Ugly Delicious: Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner���a spin-off show that sees Chang travel the world with celebrity friends such as Seth Rogen, Kate McKinnon, and Lena Waithe���he spent a day in Marrakesh, Morocco with Chrissy Teigen. And, during the aforementioned ���Steak��� episode, between his treatises on foodie culture and the absurdity of customers asking for well-done steak, Chang chides artist David Choe for ordering at Outback Steakhouse using a pseudo-Australian accent. ���It sounds like apartheid-era South African,��� Chang says before breaking out in giggles. Bill Simmons, the founder of The Ringer, joins, in saying ���He sounds like Leo DiCaprio in Blood Diamond.��� This exchange gets worse moments later when Outback���s famous Blooming Onion arrives at the table and Choe tells Chang that he thinks the franchise should develop an aboriginal backstory for the appetizer. ���I love it. I think they should make up a whole story. This aborigine went on walkabout and, on his spiritual journey, came up with the blooming onion,��� Choe elaborates. Simmons chimes in: ���His name was John Blooming.��� And Choe delivers the final blow with this gem: ���All the steaks are cooked in the marsupial pouch of a kangaroo.��� Chang shakes his head and wonders: ���Why did we invite fucking Choe?��� Why did you invite fucking Choe?

That raises another point: in each episode, Chang brings together food writers, chefs and celebrities to comment on the food tradition or phenomenon in question. Lolis Eric Elie, the writer and son of noted civil rights attorney Lolis Edward Elie, is a regular participant, but he frequently has to address questions that his white and Asian/Asian American counterparts do not. In season one, while visiting Busy Bee restaurant in Atlanta, Chang asks Elie if he should be referring to the food on the menu as ���black��� food or ���soul��� food. Later, in the same episode, the controversial Southern chef, Sean Brock, waxes poetic about the good intentions of white chefs cooking Southern food, while Chang nods along smiling. I defer to Michael Twitty here on the problematic nature of Sean Brock���s work. Chang has also garnered criticism through his frequent incorporation of comedian and foodie Aziz Ansari, causing some to wonder if Netflix hoped to set up a comeback for the scorned actor. The uneven representation on these ���expert panels,��� and the choices Chang makes in who he invites to participate, raises essential questions about Chang���s goals for the Ugly Delicious enterprise, not just in terms of his incorporation of African food cultures.

Honestly, it���s not Chang���s fault. The overlooking of African food cultures and destinations is endemic in food writing and television programing. For example, Anthony Bourdain���arguably the most important voice in modern food media before his death in 2018���filmed a cumulative 246 episodes of his shows Parts Unknown and No Reservations; only 11 of those episodes focused on the continent. On Somebody Feed Phil, the writer and producer Phil Rosenthal traveled to Cape Town and mostly frequented the white hipster restaurants that the Mother City has become known for���although he did take the advice of a local production assistant and went to grab a Gatsby at Golden Dish. Somebody Feed Phil has its own issues, but what it lacks in terms of insight, it makes up for in his charm and interviews with legendary New Orleans chef Leah Chase. Chang visited Dooky Chase, but didn���t bother getting interviews with Chase or any of her children.

On the most recent season of Bravo���s hit competition cooking show, Top Chef, Ghanaian-American chef Eric Adjepong made it to the final three, before his elimination after cooking the first course of a meal tracking the history of the trans-Altantic slave trade. (Adjepong later cooked his entire menu at Top Chef judge Tom Colicchio���s Craft restaurant in New York City). Adjepong���s elimination came on the heels of a season rife with excitement about his unique flavor profiles and a profound lack of knowledge on them from the judges and fellow chefs. When he made egusi stew, the judges described the dish as ���too gritty��� and, on other occasions, categorized his dishes as too simplistic. The lack of representation among the judges caused Vonnie Williams, writing for Food and Wine, to suggest that Adjepong���s:

season would have been the perfect opportunity to feature other guest judges of color ��� who would���ve been able to provide a more fluent understanding of West African food on the panel. While Adjepong���s third-place showing was admirable, his dishes and their reception were also a case study in the importance of diversity on both sides of the judges��� table���and that what makes a “good dish” can be as culturally subjective as it is personally.

These insights could be applied to the industry as a whole, which continues to highlight other food cultures over those from the continent and the diaspora.

This is a call for Chang to at least consider incorporating Africa into his global food explorations. Perhaps, in season three, Chang will consider including an episode on some aspect of African food and its massive impact in the diaspora. Chang loves to have a celebrity join him on his travels (witness Ugly Delicious: Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner series), so why not celebrities with connections to the continent like Issa Rae, Yvonne Orji, Idris Elba, Trevor Noah, Lupita Nyong���o, Jidenna, Daniel Kaluuya, Danai Gurira, or John Boyega to name only a few? Or, if Chang is looking for chefs or food writers, consider Kwame Onwuachi, Tunde Wey, Osayi Endolyn, Hawa Hassan, Essie Bartels, Eric Adjepong, Yewande Komolafe, Marcus Samuelsson, Pierre Thiam, Vonnie Williams, or Michael Twitty. Chang could even loop in Peter Meehan, the co-author of the Momofuku cookbook and frequent guest on Ugly Delicious, who reviewed several African restaurants in his capacity as restaurant critic for The New York Times, or Lolis Eric Elie who brought up South Africa���s love of Chicken Licken in the first season.

In a recent interview with Eater, Chang expressed his desire to expand his knowledge of food through his travels: ���In the past few years, I���ve realized that there are huge gaps in my understanding of the world ��� For my own sake, I needed to know more.��� Hopefully, even after a second season, he still strives to further expand his horizons.

Beyond the Western gaze

Protecting against COVID-19 in Mali. Image credit Ousmane Traore via Flickr CC.

We all know the feeling���we read an article by a Western pundit, or listen to a broad-brushing intervention on everything that is wrong with Africa, and we feel the need to put the Westerner and their underlying worldview in their place. We have the rebuttals ready: ���Six to seven out of the 10 fastest growing economies are in Africa,��� or ���The internet in Nairobi is faster than in Germany,��� or ���You do know that Africa is not all about huts, death and rape, right?���

I myself have engaged in a series of these rebuttals; it���s only human, and sometimes it���s absolutely necessary to provide balance. Still, we should also be aware of the crimes we might be committing in engaging in and perpetuating this pervasive binary���particularly in a context of crisis and uncertainty, and interrogate what else we could be doing to confront the shortcomings of Western reporting on Africa, particularly in the context of COVID-19.

Case in point: the drama around Madagascar���s ���herbal cure.��� I have nothing against herbal cures in particular. But isn���t it hypocritical to celebrate an untested cure when responding to French doctors��� suggestion that untested cures should be trialed on Africans with outrage? (I hope testing reveals that the cure is indeed useful by the way���but until then it���s irresponsible to engage in premature celebrations. To suggest that skepticism about the cure is merely a product of racism is also reductionist. There are plenty of other reasons to be skeptical about the cure, and the recent outbreak in the Malagasy city of Toamasina highlights that herbal cures in any case cannot replace and should not distract from the need of a comprehensive country-wide containment and mitigation strategy).

To be clear, the language of some Western reporting on COVID-19 in Africa completely erases the agency and ingenuity of African governments, communities, and individuals. But sometimes, Western reporting deliberately sets up a binary in order to ���provoke,��� generate clicks, and outrage only to then swing to the other side of the pendulum.

Many “Africa is doing great with COVID” takes are as problematic as the “Africa is hopeless in the face of this crisis” takes. They lack nuance, downplay the complexity of the situation, and most importantly still operate within the Western gaze. They also lack humility���we still have so much to learn about this crisis, and have to appreciate policy trade-offs associated with the huge social and economic costs of lockdown measures. As Teju Cole recently warned: ���I keep thinking about floods, and how only after the waters recede do the bodies of the drowned become visible.���

���Hopeless Continent,��� ���Africa Rising,��� ���Afro-optimism,��� or ���Afro-pessimism���: These binary meta-narratives are ultimately two sides of the same coin, and they���re equally useless. It’s like when people post pictures of skyscrapers in Nairobi in response to Westerners reducing African countries to slums. Like yeah, I���ve engaged in these responses as well���but the slums still exist.

Bold policy interventions (tailored containment strategies, or innovative approaches to boosting social safety nets), civil society engagement (information sharing, community health workers, solidarity assistance), and innovations (a range of low-tech interventions, solutions from entrepreneurial ecosystems, data sharing) across several African countries are incredibly encouraging. But one simultaneously is exposed to as many disappointments���incumbents using this crisis for authoritarian means (Benin, Burundi, Uganda���to just name a few), rising food insecurity (in the Sahel or the DRC), and policy fragmentation (are African countries coordinating and cooperating as effectively as they could be; are policies actually implemented and do they reach the poorest?). The latter are topics we absolutely must debate and bring attention to as well.

Sometimes the “Africa is doing great” trope takes tend to deliberately avoid talking about certain contexts or countries. Since I’m used to the Democratic Republic of Congo being overlooked as part of “Africa Rising,” I’m familiar with these patterns of deliberate omission. Are countries that struggle or don���t fit into the binary of the day “un-African”? This also results in a lack of global attention on crucial issues: Why have the problematic electoral processes that took place in Benin and Burundi during the last week not sparked more outrage?

Linked to this is a worrying trend, which Kenyan writer and political analyst Nanjala Nyabola coined as ���Man-Africanism.��� According to Nyabola, ���Man-Africanism can only discuss Africa by discussing the West,��� and is repeatedly instrumentalized to protect powerful and rich Africans. Of course, sometimes when those rich and powerful Africans go to the UN to represent our interests it can be a useful strategy to support them. But too often is criticism, such as highlighting widespread poverty, corruption, or lack of structural transformation, being silenced or avoided in order not to ���complicate the story��� or undermine a certain government vis-a-vis the global audience.

Pointing to poverty, and exploitation becomes ���Eurocentrism��� that undermines ���African unity,��� while some elites continue to reinforce the very colonial systems they rhetorically despise in order to cement their grip on power. Most importantly, according to Nyabola, ���Man-Africanism has the hubris of anti-colonial thought, but none of its strategic creativity.��� One could also think about the shared affinity for uncritical celebrations of authoritarian developmental states among both the Western and Africanist punditry, but I digress.

Man-Africanism is deeply engaged in the politics of low-ambitions, and a fertile ground on which African elite complacency, as well as authoritarianism, can thrive. Political scientist Ken Opalo from Georgetown University expanded on this point in a recent blog:

One need not be wearing a tinfoil hat to see the many ways in which African leaders continue to act like colonial ���Native Administrators.��� Some do not even pretend to care about aspiring to govern well-ordered societies. For almost six decades the global state system has accommodated elite mediocrity in Africa. During this period, the collusion between African and non-African elites in the pilfering of the region���s resources was balanced with aid money and other forms of support.

As Opalo emphasizes, COVID-19 and its associated economic fallout is about to make this already incredibly expensive elite complacency ���a lot more expensive.��� In the case of the DRC, which is currently facing a severe recession, multiple public health crises, insecurity, food price increases, while much of the country is focused on a high-level government corruption scandal and ongoing battle for power between coalition partners, the cost of such complacency is obvious.

As we at Africa Is a Country know very well, there are many structural issues and biases associated with Western reporting on Africa, which will obviously not have disappeared when it comes to reporting on COVID-19. Criticizing the shortcomings of Western media is essential, but we also must strategically think about how to dismantle power relations within the media. Political scientist Jan-Werner M��ller stresses that COVID-19 makes vibrant local news coverage vital and more important than ever. M��ller worries that the recent decline of local news ���has reinforced the pernicious polarization.��� Local news coverage is also key to dissect other unhelpful meta-narratives such as ���China is Africa���s friend vs. China is Africa���s new colonizer,��� as I���ve pointed out in previous pieces on local news in Congo, and China���s Belt and Road Initiative. Media partnerships across different African countries and the diaspora such as Africa Is a Country���s partnership with The Elephant in Kenya can also be part of the solution.

Ultimately, following nuanced perspectives, engaging with local realities, and transcending the Western gaze is more interesting and rewarding for anyone involved. This entire back-and-forth “Africa needs help” vs. “No! Africa can teach you lessons!” is tiring, and other than benefiting a few pundits on both sides of the debate���are we deriving any value from it? As members of the diaspora, or as members of the intelligentsia, we should also reflect on Frantz Fanon���s warnings from Wretched of the Earth:

The national bourgeoisie, with no misgivings and with great pride, revels in the role of agent in its dealings with the Western bourgeoisie. This lucrative role, this function as small-time racketeer, this narrow-mindedness and lack of ambition are symptomatic of the incapacity of the national bourgeoisie to fulfill its historic role as bourgeoisie. The dynamic, pioneering aspect, the inventive, discoverer-of-new-worlds aspect common to every national bourgeoisie is here lamentably absent. At the core of the national bourgeoisie of the colonial countries a hedonistic mentality prevails���because on a psychological level it identifies with the Western bourgeoisie from which it has slurped every lesson.

Sometimes it is strategically important to hold your nose, and as Amilcar Cabral put it: ���Mask no difficulties, mistakes, failures. Claim no easy victories.���

Rejoicing that African countries are outperforming countries like the United Kingdom in their COVID response is the definition of claiming easy victories grounded in low-ambition. Almost every nation���s response looks favorable vis-��-vis the UK. Why should a nation in rapid decline dealing with a toxic combination of regional inequality, empire nostalgia, media polarization, and nepotism be a standard for African countries?

Ultimately, COVID-19 is a powerful reminder that we must reclaim African reality in all its forms in order to adequately define and respond to the challenges we face and imagine African futures, which transcend the Western gaze.

As the late Binyavanga Wainaina said so brilliantly in a talk he gave at McGill University: ���Me ��� I don���t care about this whole Africa Rising thing.���

Dog day afternoon

Still from "Clebs."

It is not often that we have the pleasure of receiving an African story that does not make its focus the most ugly precarity the continent has to offer. So much nonfiction about Africa, film or otherwise, portrays lives in immediate need of saving, usually by external forces. But to suggest that “Clebs,” the latest work by Swiss-Moroccan director Halima Ouardiri, merely reverse this dynamic���showing us instead lives already being saved from within���would be an injustice to a film short that is as beautiful and broad as it is deceptively simple.

From its very first shot, “Clebs,” which translates as Mutts, dispels any attempt at straightforward categorization. The location goes unmentioned; no context is provided. But as one after another dog enters, and eventually fills, the frame, our attention is taken hostage. The coat of a single, panting dog envelops the title screen with the spectral richness of its texture and color. The director���s appreciation for the beauty of these animals is as vividly apparent as it is compelling. Yet, the film is far from being an animal rights documentary���it is as much a mixed breed as the animals acting as its subject.

Still from “Clebs.”

Still from “Clebs.”Of these 750-some strays, not one is of an identifiable breed. Reminiscent of mutts the world over, they seem to take their color from the same palette as their surroundings: the chalky reddish brown of crumbling mudbrick, the hazel of shadows cast by the ascending and setting sun, the bleached ochre of a dusty, grassless courtyard.

Taken from static camera angles, a series of long shots captures the movement of the dogs within the walls of their Moroccan sanctuary, drawing us further in by accentuating the quotidian. The dogs, well cared-for and seemingly contented, lounge in the shade and nap in the sun; they play, they fight, they piss, have sex, shake away flies, scratch at fleas, and bare teeth. Innocence yields to hierarchy, to order imposed with violence.

Still from “Clebs.”

Still from “Clebs.”Slowly, as Ouardiri���s patience as a director transmutes into the viewer���s curiosity, the acute awareness of what we are seeing transforms into our search for its meaning. Ouardiri does not give us one���at least not readily.

Any viewer will notice that which throughout “Clebs” is almost perfectly, and intentionally, absent: human life. Though we catch brief glimpses of passing caretakers, it is not until near the film���s end that we first hear a human voice. Streaming in from an out of view radio, the specter of a French news broadcast recites the latest UNHCR migration statistics: ���this figure of 70.8 million, which can be broken down to 25.9 million refugees, and 41.4 million people displaced within the borders of their own country and 3.5 million asylum seekers.���

Still from “Clebs.”

Still from “Clebs.”Just before the voice is heard, we are finally shown the sanctuary���s picturesque surroundings; a dog twice stretches its paws up the height of a wall as if to scale it and escape, and yet another gazes longingly out of a metal grate acting as a window. The preceding images, now supplemented by the voice of Man, suddenly take on profound new meaning. The dogs are no longer simply animals but symbols of our own, human condition.

Absent the distraction of our own form, the film���s intimate focus on the dog allows its subtle allegory to play itself out in full. ���We behave just like dogs,��� Ouardiri said, and indeed we can recognize in their behavior a great deal familiar to our own. Their leisure is our leisure; their stampeding and fighting for food, our own insatiable consumption.

Contained as these animals are within the confines of their compound, “Clebs” could not be more timely in its symbolism. Perhaps they are the millions fleeing Africa for the promise of safety and comfort in Europe, or perhaps they are like all of us���just trying to survive and longing for something better. How could we not, in so observing our proverbial best friend, find a truth about ourselves?

May 27, 2020

A time for farewell, and a return

Ishmael Beah. Image credit Priscillia Kounkou Hoveyda.

In the summer of 1998, I had just arrived in the United States from Sierra Leone and, as every immigrant does, I began the immediate process of recreating myself by observing the ways of being in my new home. I had no intention of absorbing everything so as not to collapse the architecture of my heritage, my identity, everything I had been until then. I was aware that some conformity was needed. It was a confusing time because I knew that no matter the perception of my homeland, it had its own vital wisdom and strength, part of which I had brought with me. However, I quickly realized that people in my new home were either unaware of, or uninterested in anything about where I was coming from or what I had to offer. Whenever I spoke, I was asked to repeat myself, though I enunciated and sounded every syllable with ease and without any haste.

My new family took me to Colorado for the last weeks of summer. There, I met one of many family friends who was introduced to me as a ���thinker, a professor of history and foreign policy, a worldly person.��� So naturally, I wanted to have a conversation with him. My grandmother���s words that, ���every encounter with another person, if done with genuine curiosity, becomes an exchange of knowledge that elevates humanity,��� chimed in my head with urgency. I asked this “thinker” family friend if we could go for a walk the following morning and he agreed. I was ready as early as I could, my mind whirling with questions, and my spirit dancing with anticipation for the pleasure of an exchange with someone who I didn���t have to explain to where my country was and the generalities always associated with the African continent.

I greeted him with excitement as he emerged from slumber. But the mannerism of his responses left me bewildered. ���Did you sleep well?��� he asked. He put his palms together and placed his head sideways on them. I nodded a yes; lost for words. He returned with, ���Do you want to drive or walk to town for coffee?��� and again, acted driving and made a walking motion to accompany his words. I said, ���I prefer walking,��� and marched forward to mimic how he had been signaling his words to me. It took him a minute to get my sarcasm, and I knew that there would be no substantive exchange between us. He had not come with the genuine curiosity needed for an insightful conversation, but rather a preconceived idea that had clouded his point of view. He knew where my country was, but something in his thinking had told him I would have difficulty understanding English, though I had spoken to him in English, come from an anglophone country, and was slated to attend school in the US. None of these things connected and I was left thinking, why? On the walk he talked about his love for Fela Kuti���s music, S.E. Rogie, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Miriam Makeba, he went on. But he still spoke with a deliberate slowness as if I was incapable of understanding him otherwise. Additionally, he began lecturing me about African politics and traditions in general. He had never been anywhere on the continent.

Yes, this fellow in question knew the names of Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, and so on, but just as politicians whose intelligence had to be filtered and explained through the western point of view. When it came to writers he knew only of Chinua Achebe and then, only of his classic Things Fall Apart. He didn���t know any contemporary African writers or thinkers. Yet, he had opinions, strong ones about Africa and our need for leadership.

Another such encounter was in 2014, during a reading and signing event for my second book. A reader commended me on how “good my English is” while holding both of my books written in English.

Why was this? And, what does this say about us, about African thought, knowledge, intellectualism, wisdom? Why is it belittled? Why is it disbelieved? Why is it that even those who don���t know us feel the need to tell us about ourselves? Over the years these questions lingered in my mind as more of such encounters would occur.

I believe one major reason for this is because we, as Africans, have long neglected the merit of our own intelligence, knowledge, wisdom, thinking, and look outside for answers rather than inward. We rarely re-evaluate ourselves, the basis of our knowledge and our traditions on our own terms. We have handed that responsibility to outsiders who only measure us through our failed politics and politicians, and vis-a-vis themselves, they as the solution.

How many African countries use traditional oral storytelling in their curricula or predominantly assign African writers and thinkers in forming the basis of their national educational systems? Yet, if you ran a poll on every African person or anyone of African descent, they will tell you lessons they had learned from hearing stories. It may even be a story that was repeatedly told to them that formed the basis of their values, moral, emotional and psychological foundation. However, when most educated Africans want to flaunt their intelligence, they will quote from Plato, Aristotle, Ren�� Descartes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Spinoza and the likes rather than ideas from an African parable or from Amadou Hamp��te Ba, Thomas Sankara, Mariama B��, Sekou Tour��, Njinga Mbandi, Kwame Nkrumah, Alda do Espirito Santo, Marcus Garvey, Sarraounia Mangou, L��opold Sedar Senghor, Ama Ata Aidoo, Patrice Lumumba, Taytu Betul, Eduardo Mondlane, Frantz Fanon, Wole Soyinka, Albert Camus.

We rely on explaining ourselves and understanding who we are through the theories and traditions of others. Those who have shown through history and current actions to have no regard for our lives, values, thoughts, knowledge, wisdom and traditions. ���No group, however benevolent, can ever hand power to the vanquished on a plate,��� said the South African Black Consciousness leader, Steve Biko.

The power that we are missing lies in the return to celebrating and using our own ideas and ideologies to sustain our way of life. As Fanon stated, ���Imperialism leaves behind germs of rot which we must clinically detect and remove from our land but from our minds as well.��� Our expressions of ourselves and how we perceive the world begins with ideas that are prevalent around us, and as a result we espouse into our being. These ideas always predominantly come from stories, from our traditions and our knowledge base. So, until we return to believing in our own ideologies, everything we build will have a hollow foundation and in time will collapse. To rebuild the architecture of our intellectual foundation, our knowledge base requires a return to our own thinkers, past, and most importantly, contemporary.

Before COIVD-19, a movement of reimagining ourselves on our own terms had already started on the African continent. And now, this global pandemic has exposed behind the curtain of the values, knowledge, and ideologies we had blindly followed while ignoring ours, and they have been found wanting.

There are many things we can learn from this global crisis. One of them, and I believe it is an important one, is that we must return to our own wisdom and intellectual space, fully and irrespective of any other. We can always borrow wisdom, but the predominant knowledge that governs us should be ours only. ���The great powers of the world may have done wonders in giving the world an industrial and military look, but the great gift still has to come from Africa���giving the world a more human face.��� Steve Biko was right, but to give that gift requires re-believing in our own thinking, ideas, ideologies, arts, creativity, our knowledge base, all of which we���ve always had.

For two years I lived in Abuja, Nigeria. Once, I attended a dinner with some guests visiting via a certain foreign embassy. The head of the delegation was of African heritage, born in the west. He told me they were in Nigeria to teach critical thinking to people in the north of the country. I asked if they knew of our traditions of oral storytelling that already teach critical thinking. They had not thought of it. It left me thinking about the countless young men and women I had met on the streets of Abuja, Freetown, Goma, Nouakchott, Kigali, Makeni, Accra, Lagos, Johannesburg, Yaounde, Cape Town, Dakar, Nairobi and so many more, who have to be economist, psychologist, philosophers, anthropologist, geologist, linguist ��� to survive and live daily.

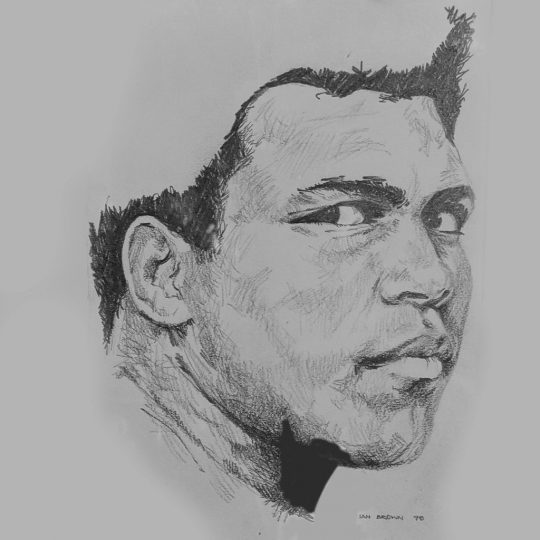

Ivan Vladislavic and Muhammad Ali

Image credit id iom via Flickr CC.

Though born and raised in the Afrikaner stronghold of Pretoria, 62 kilometers to the north, Ivan Vladislavic is a Johannesburg writer down to his bones. He has pantomimed that city���s ebbs and flows for thirty years, beginning in earnest with his 2001 novel The Restless Supermarket and its view from the rapidly ���Africanizing��� neighborhood of Hillbrow in apartheid���s aftermath. Critics bemoan the gap between the respect he commands among those in the know and his enduring relative unknownness, but in this sense his career reflects the setting that shapes it. Vladislavic���s work, like Joburg itself, is tricky to inhabit, thwarting attempts to settle in through clear paths to understanding. It fosters a sense of always hovering just outside the action, as readers grasp at moving parts that don���t quite make a whole. To his credit if not with the result of great popularity, Vladislavic is a master of estranging himself in order to tune into his surroundings.

The apparent focus of his latest book, The Distance (published by Penguin Random House in South Africa; US Edition forthcoming from Archipelago Books), is a Pretoria boy���s fixation on Cassius Clay as he becomes Muhammad Ali. It is narrated as a back-and-forth between two brothers, Joe and Branko, who chronicle their lower-middle-class white childhood with neither nostalgia nor self-centering regret: it was what it was, more for the worse than the better. The Distance jumps from their mutedly violent past to more artful and even ���woke��� Johannesburg present using a set of Ali scrapbooks as springboard, thereby introducing key elements from two earlier Vladislavic works. The first, Portrait with Keys, is a loosely autobiographical 2006 compilation of short texts about the so-called city of gold, and offers a template for the formal and thematic splicing that drives The Distance. The second is his 2011 novel Double Negative, whose investment in the complementarity of photo and text reappears now as a give-and-take between making and interpreting the scrapbooks across time frames. ���Forty years later,��� Joe explains of his present task, ���these books are spread out on a trestle table beside my desk as I���m writing this. Let me also confess: I���m writing this because the scrapbooks exist.���

As with so many Vladislavic lines, it is a wonder that his meta-awareness does not tip over into gimmick. It avoids this trap by laying out a clear purpose for its readers: we are meant to combine and re-combine the various elements that bring any place into composite being, and whose sundriness is especially noticeable in South Africa���s biggest and most bustling city. This is different from mere deconstruction. Every ���data set��� in the book���newspaper clippings, photographs, vignettes���can be interspersed with any other to arrive at a slightly different but no less revealing way of charting South Africa���s past. The scrapbooks, for example, are described as an ���archive��� whose meaning is unstable, but not as one that is ultimately meaningless. Vladislavic is in some sense a ���choose your own adventure��� epistemologist. And in large part, the mixing and matching on which The Distance relies is also a way of re-creating its characters��� memories from afar. ���While boxing in general did not appeal to me,��� Joe recalls, ���my interest in Muhamad Ali was all-consuming. I might have forgotten the full extent of it, as we forget so much of what we thought and did in the past, had it not been for the archive of cuttings.��� The clippings that recreate Ali���s legend also lead back to a forgotten past. A father reading a newspaper in his armchair; its local classified ads and Cold War headlines; the mother knitting in the next room to hold the scene together.

Unlike any number of other white South African writers, though, as they try to make sense of a past that they should not have had, Vladislavic imbues such recollective acts with neither poignancy nor pathos. His self-distancing takes the place of paralyzing self-interrogation, and this is his greatest virtue. There are many things more interesting to Vladislavic than the experience of someone like Vladislavic, and he is constantly attentive to other routes through the text that any momentarily chosen one precludes. All of the Ali clippings have a literal flipside of the violence taken for granted in the South African boyhood setting of their first, real-time encounter. As the brothers trade-off their narration, local stories appear as section headings to form a series of grim historical footholds: ���Krugersdorp���Two African mine workers died after an accident in the West Rand Consolidated Mine near here yesterday.��� Or, a bit later and with more context, ���A story on the back of a cutting catches my eye. It���s about two mineworkers who died in a rockfall at Westonaria Gold Mine.��� Such arid descriptions of death are set off against the bloody play-by-plays of sports journalists describing Ali���s legendary fights.

One reading that suggests itself here is that a white kid in Pretoria sublimates his awareness of the violence all around him into a fixation on a violence that is contained, and so lends itself to poetic description. In comparison with the glumness of being taught by a headmaster who delights in beating his pupils, the artistry of Ali���s punches is an escapist fantasy. With this as a point of entry, The Distance becomes a book about South African sports writing as a genre and historical institution. Joe describes, for example, a ���four-part series��� in the Pretoria News by the sportswriter Alan Hubbard, which gives Ali���s 1972 fight against Al ���Blue��� Lewis in Dublin a theatrical sheen. ���Said Hubbard,��� Joe writes, ���On stage every day at Croke Park, Muhammad Ali is giving a matinee performance as a big, black Buttons. (Hubbard was referring to the servant in the Cinderella panto who always insults the ugly sisters.)��� Another possible reading is that Ali���s global stature depended on the same racial capitalism that underwrote apartheid, a textual experiment in scalable exploitation. Following this thread leads straight to discussion and in one case, filmic representation of the Marikana massacre in the book���s present tense. Both routes to making sense of The Distance are defensible, along with a good many others. Vladislavic���s achievement is to present them all within the same narrative space, while nonetheless forcing our attention to discrete continuities. From this, paradoxically, a map to understanding Johannesburg���s felt discontinuity can arise.

The timeliest dimension of The Distance, with quarantined readers likely to be steeped in their virtual enclaves of choice, is its suggestion that Vladislavic���s quintessentially ���Joburg form��� anticipates the challenges of the Internet. He guides us through a bevy of media with more or less immersive properties, from newspapers through television straight up to present-day infomania. The adult Branko observes of his 1970s childhood that ���South Africa was not the best place from which to observe developments in the mass media,��� which, in turn, meant that ���In the absence of television, sport was still news rather than spectacle.��� By the time he is forced by family tragedy to take over stitching the Ali scrapbooks into some sort of narrative cohesion, his online immersion has made it feel like a lost cause. ���Days go by,��� he admits. ���I���m drawn in by the cluttered sidebars, the insistent pop-ups, the pictures, the tips, the lists. Especially the lists. The 10 Sportsmen You Didn���t Know Were Born With A Cleft Palate. The 5 Best Ways To Lose That Stubborn Fate On Your Midriff.��� And on and on for a thick paragraph of nothing, before confessing, ���I can���t tell where one thing stops and another starts. It all bleeds. It���s a bloodfest.���

These, then, are the stakes of riding Vladislavic���s multilane highway to now: violence meets quiet, action edges toward observation, and personality gives way to place. But where The Distance, like Portrait with Keys before it, asks that the reader build links across and between planes of memory, history, and city, the virtual world with which the book���s past collides is discomfitingly edgeless. Vladislavic is an auteur of this moment of collision. Always hovering just askew of the city he loves, his is a voice for making new spaces within it.

May 26, 2020

What are courts for?

The Constitutional Court of South Africa. Image credit GCIS via Flickr CC.