Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 176

May 21, 2020

Confronting the weapon of photography

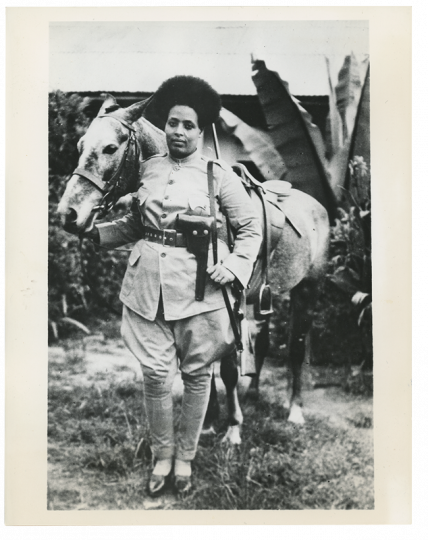

Image credit Maaza Mengiste.

With the establishment of the practice of photography in the 1830s, those who controlled that dark image-making machine���the camera���and its photographs, inherited the imperial claim of monopoly on truth and history. And yet, as the political theorist of photography, Ariella Azoulay, elucidates, the event of photography involves more than just the photographer and the camera; rather, those photographed, and later the spectators of images, also figure into the

Weizero Abebech Cherkos Addis Ababa, 1935. Image credit Maaza Mengiste.

Weizero Abebech Cherkos Addis Ababa, 1935. Image credit Maaza Mengiste.social meanings forged by the shutter���s verdict. This more comprehensive conceptualization of photographic images, and the histories in which they are embedded, uncenters and unsettles the photographer���s gaze, opening up space for alternative histories, memories and stories.

It is with this sense of unsettling the European history of conflict in mind, that Maaza Mengiste���s acclaimed second novel, The Shadow King, confronts the Second Italo-Ethiopian War of the late 1930s. Rather than fixating merely on the war���s most prominent events and depictions, Mengiste transcends the traditional historic frame of the battlefield by exposing readers to the intimacy of her characters��� lives, each with their different vantages to invasion. In the unfolding of the story, she draws from the shadows struggles of both the everyday and the extraordinary, waged on the fronts of class, religion, gender, the body and photography.

To shed light on the deeply textured specter of photography in The Shadow King, which intersects in myriad ways with these other themes, Mengiste generously spoke to us about the imperial legacy of the camera, modes of resisting the colonial gaze, differences in the narrative power of words and images, and her new image-oriented archive initiative���Project 3541.

Zachary Rosen

Photography is one of the threads that is woven throughout the storytelling of The Shadow King. There is a character who uses a camera, though the allusions to the histories and philosophies of photography are very textured and expansive in the story beyond any single character. Did you plan for photography to be a key element when you began writing, or did it emerge along the way?

Maaza Mengiste

I have to think about that. This final version of the published book was not the draft that I had initially written; I got rid of that one. And in that draft there was really nothing about photographs and photography. Once I started thinking about this Italo-Ethiopian War of 1935-41, and the relationships that were developing over the course of those five years or so in Ethiopia, I started thinking about the use of photography as a weapon of war by the Italians and by most colonial forces and imperialist regimes. I���d been writing about photography already. For nearly a decade, I had been collecting photographs that Italians took in Ethiopia. At the beginning, I didn���t know what I was doing. This was even before I was writing; I was not a writer, I was just interested in this. I was collecting these photographs, not knowing but looking, thinking, ���Oh these are beautiful. This is nice, oh, this is not so nice.���

At some point, when I was in Rome doing my research, I became really invested in the photographic history of this war and started diligently collecting the photographs, not clear at that point, still, what I wanted to do with them. It was helping me to look at history through a different lens. No pun intended. I was looking at the intimate aspects of the war, not the big battles, but trying to figure out through these photographs the intimate connections that war forced on groups of people. So when I had that first draft, I had those photographs, and I was looking at them to rewrite history, but not as history. But once I got rid of that initial draft and started thinking, well I can do anything, what would I like to do? I went back to these images and started considering them as their own versions of history; they are preserved memories, but what exactly did they preserve and what were they trying to force us to overlook or forget? Along with the choral voices in the book, the use of photographs became for me another way to upend what we assume history is, and it was enjoyable, but also really insightful. It helped flesh out details of moments and characters for me that just a straightforward narrative wouldn���t have done.

Zachary Rosen

You���ve spoken about how history books are told from certain perspectives, the photographic frame has limitations of what is inside, what is not inside, who is holding the camera, what their intentions are. The narrative of the writing then becomes a way of going beyond the frame, can you speak more to that process of going beyond?

Maaza Mengiste

I think the photographs were a way to go beyond the frame. It also forced some questions on me about the identity of the photographer. And if we imagine the photographs that are taken���the cameras are no longer these big bulky things, they���re handheld���these are not taken by photojournalists or professionals, these are soldiers who are leaving Italy for the first time. For some of them, it���s the first time that they���ve left their small town. These soldiers were there for an African adventure. They were promised a quick easy war. They were promised women as trophies. You get the land, but you can also get the women. And they bring this camera. I started thinking about how they wanted to shape the memories that they brought back with them, because the photographs as candid as they were, were very calculated in terms of who got to see what������when I bring this back home, this set I���ll show my friends, this set I���ll show my family������these memories were curated. I started looking at the photographs like that. As tools for remembrance, but also tools for amnesia, for erasures.

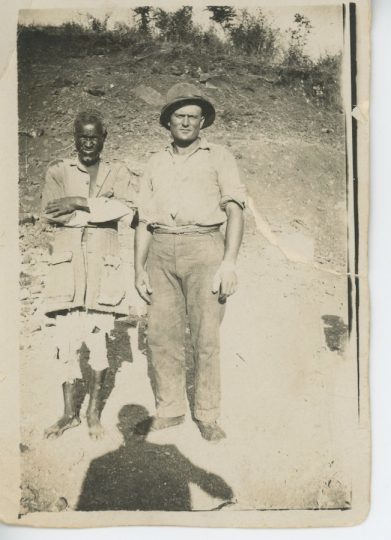

Ethiopian Army. Image credit Maaza Mengiste.

Ethiopian Army. Image credit Maaza Mengiste.Writing about them in the book really enabled me to look in new ways. I���m aware that I have a character Ettore, and he has a camera, and I���m looking at the photographs as part of a conversation that this photographer is having with himself. Something that moves beyond the ground that he���s standing on, and is also going to extend back home. It���s the part of him he wants to take back���this thing that has contact with the exotic, the erotic. Back home, the photographer takes on some of the exotic nature of the photographs. He���s heralded as something different from others in his town, heroic, and in some way as unknowable as those he���s captured on film. These photographs really reflect back on the image maker, and I found that this thinking helped develop the story. It helped me understand a lot more about all of these images that we���ve taken for granted���that I took for granted, even as I was collecting them. Saying, ���Well this is a beautiful picture,��� but actually when you look at a picture of a warrior who is proud with a shield and his spear, and he looks dignified, it doesn���t look like a negative or stereotypical photograph at all. Until you realize the photographer and the man should be enemies. Then, the fact that the photographer is still alive says something about his power and not the person who is being photographed. It���s a photograph of domination.

Zachary Rosen

This book reveals how a central legacy of the camera is as a technology of imperialism. In the story you describe how the Italian forces document their work as evidence of occupation and justification for colonization; how a photographer shoots, captures and steals moments, brings people into focus for their subjugation, how typographies are imagined from photographic prints. With such a burdensome heritage referenced, has the process of writing this book made you consider if photography is irredeemable, or whether it can be valuable as a creative form?

Maaza Mengiste

I think that in the photography world, within the world of photojournalists, we see a clear lack of photographers who are from the places that are being reported on. We see this all the time, most of the photographers are white, they���re male, young photojournalists who are enrolling in journalism schools and imagine this adventure; they���re enamored with the danger of being a photojournalist and going into a war-torn country. That way of thinking is a form of imperialistic ambition. It is war-like in its desire to ���conquer��� to make knowable what seems remote, unknown, exotic. You still see it now.

Recently there was a well-known photojournalist who was advertising for a photo workshop that was going to be online in the coming days but the image that he used was of a young woman in India who was a sex-worker. In the photo, a man is on top of her, it���s in the middle of the sex, you see her face���the blankness���she���s somewhere else and disturbed. And the camera is looking down at this woman. Her face is not covered. Every voyeuristic aspect is at play in that image. This is something that���s used to advertise a workshop. And I���m thinking, what is being advertised here? What���s happening here? I asked the photographer these questions and the image has since been taken down. On Twitter, somebody named Ritesh Uttamchandani���a photographer from India���said, ���I went into the brothels also to photograph and this is what I did.��� And it was brilliant. He photographed from the bed up to the ceiling. So, you get the room, you get what this girl might be looking at, and he said from that vantage point, he was able to see baby photographs, a family, there was a whole world that opened up. It puts you in the position of the person who is there. This makes me think about the ways that photography is done now, and how it has always been done. The power dynamics are skewed, and unless we���re able to see ourselves in the person that we���re pointing a camera at, unless we recognize or seek to recognize some part of us in the images we make, what we���re doing is projecting people���s experiences as fascinations or curiosities or metaphors or lessons in living. And we���re still outside.

I made a very deliberate decision not to put photographs in the book. There are two, the bookends. Writing the word-images inside book was my way of thinking about how to move beyond ���bearing witness������where the witness is always outside and bearing the burden of witnessing���and the act of looking is an unwieldy responsibility that���s put on that person, and it���s not a natural thing, it���s a weight. I���ve been questioning for a long time how to eliminate that. The photograph is a weapon, it���s a sign of power and it���s still being turned on people. Those who are looking are not the ones bearing anything. It is those depicted in the frame who hold the balance of the weight. How do we honor that, respectfully, and see ourselves in every image we make?

Zachary Rosen

Has your interrogation of the way photography transforms people affected how you take photographs, especially those of people?

Maaza Mengiste

I take film and I will shoot and I���ll have rolls of film piled up for three or four years. Eventually, I don���t know what they are, I forget. I keep shooting and then periodically I get a whole bunch of rolls and I send them to my developer and then they come back and it���s always interesting because I don���t know where or when some of the rolls were taken. If photographs are a form of erasure, then perhaps I���m also trying to understand what remains there, preserved, when certain markers no longer exist. In looking at them I try to understand my eye, what is it that I���m looking at? What is it that I���ve always seen? I put mostly portraits up on Instagram and that really tends to be the thing that attracts me. I���m interested in the face and I���m interested in what the face reveals. Photography is something to take me away from writing, from that place that���s continually worded and seeking more words. It���s a good way not to think of writing but I realized I���m always thinking about narrative when I���m looking at the camera. Something very interesting happens when you���ve got your eye behind that viewfinder and you���re focusing���here���s another world that starts to exist within that, and in that way it���s a lot like writing. I���m trying to develop my eye, because that���s the same eye I use as a writer. And the camera is my tool.

Zachary Rosen

You���ve spoken about how some core characters seem to have emerged from archival photos you encountered in your research. How did your interactions with these archival images translate into characters in the story? Did the photographs speak to you?

Maaza Mengiste

I had these photographs before I was writing the book and some of them I had framed. As I was writing, I realized they were helping me envision some of my characters. Then, somewhere along the way, I dug into the photographs of Italian babies I���d collected from the early 1900s. I didn���t know why I had searched for them, years ago, and I don���t know who they were, but I was having trouble developing the Italian Colonel in the story, Carlo Fucelli. I decided to consider him as a baby. So, I put ���his��� baby picture up at my desk and used that to understand his evolution into the man he became. I describe a photo that Ettore has of his parents on their wedding day. I have that photo, I have a photo of a couple. I had been trying to find a way to describe the character Hirut in my head to myself, and I started looking through my photographs and as soon as I came to one particular photo, I knew I had it. I said, that���s her. The V-neck dress I���d been describing, the scar that the dress can hide, that was in the photo, and that���s who she is. I have a photograph that could be Aster, I envisioned this woman in a cape and I had the photograph in my collection. I had done the description���who knows if I had looked at those photos much earlier and they had stuck with me, but they definitely helped me envision an attitude, not a look, but an attitude. When I was writing my Italian characters, if I could not imagine these soldiers as little boys, it was going to be really hard to develop them as complex human beings with both cruelties and vulnerabilities.

Zachary Rosen

The book contains several types of interludes, including a form called ���Photo,��� where ���word-images��� describe pictures without displaying any visuals. How did you envision the function of these fragmented texts? Some of the passages are almost shaped and sequenced like small photographic prints.

Maaza Mengiste

The overarching narrative is that those are ostensibly the photographs that Hirut is looking through when she opens the box in the story, and it���s in chronological order so as each photograph is encountered it unfolds into another part of the war and into the story. The thing that I wanted to make happen within those images was movement; to try and imagine the moments before and the moments after, which is what a photograph will often eliminate for us. It simplifies a moment. I���ve been really inspired by one of my favorite paintings���Rembrandt���s ���Anatomy Lesson.��� You have in that painting medical students who are around a corpse and there���s a doctor in the middle; everybody���s looking in different directions but the doctor is pointing at something and his hand is up. I���ve stared at that for so long, moving from the gazes of the students, to the body, to the doctor, to his hand. At some point I realized he���s pointing to the muscle on the corpse that his hand illustrates, and what he���s doing is mimicking the movement of that muscle and pointing at that. So, this painting is caught mid-act; the doctor���s hand is just a flick of muscle and movement, paused by the painter. It is really a lesson that is in motion and this is not about the corpse, it���s about life, it���s about the hand that���s moving. The anatomy of the living. This way of looking, of moving past what is most obvious to those revelatory details in a frame ��� that has stuck with me ever since I���ve seen that painting.

John Berger writes about this painting, and he writes about its connection to Che Guevara���s assassination photograph, and the eerie coincidental posing of both of these���the way that also in Che���s assassination photograph there are all these soldiers standing around his corpse, looking in different directions while a superior is pointing at the corpse. And again, the lesson is not about death, it���s about the life that���s going to happen beyond that image. Beyond Che���s death. Beyond a revolution that they believe has now failed. I have found it really fascinating to look at those two���the painting and the photograph���as a way to understand the malleability of history, or memory.

Both of these images are on one level about death, but they���re also about who is looking, who is pointing, who is moving and who cannot move. That was the idea that I wanted to translate into the book���s word-images. Who is moving and who cannot move? You think this is about dying, but it���s actually about the person who���s alive and in power. There are levels and layers of looking. When you have that word-image, there���s the reader and then there���s also history that we have to read through to get to the core of what was really being made or taken in that photograph.

Zachary Rosen

There are some incredible moments of resistance to photography in The Shadow King, in which gazes withdraw or accuse the camera, relationships and senses transcend the photographic frame, and quaking bodies defy the limits of the shutter. Can you speak to why you described these disruptions to image making?

Maaza Mengiste

It started from just looking at these photographs and paying attention to what people are actually doing even as they���re standing straight and looking at the camera. If we assume there are really no voiceless people, there are really just people we don���t know how to hear, then my task is to observe what it is they���re telling me that I couldn���t see at first glance. And what I started noticing could be things like just a gesture of the hand, a clenched fist, toes that had been curled inward when that���s not necessarily a natural stance, that blurred movement, the look away, those quick gestures that would happen, the refusal to smile, all of those were small acts of defiance. They���re muted, but they were there if I only knew how to look and that was part of what I was really working on, how to look closer at them, how to listen to them. There are always tell-tale clues, always in these photographs. I wanted to bring that to life, to return to people their due respect for what they did, their acts of bravery.

Zachary Rosen

Who are the image makers who have most shaped how you think about photography and treat its practice in writing?

Maaza Mengiste

Diana Matar, for starters. She has one book out called Evidence and another on the way where she considers what still echoes, invisible but present, in places where state-sanctioned violence took place. She visits those places after the fact and photographs them. She���s really considering the question of what remains? She���s looking at the erasures, but also the memories that still linger in those sites, of those lost lives after a disappearance or after an atrocity. In Evidence, she goes to Libya and looks at locations of Ghadaffi���s executions and where people were disappeared. She then photographs them. Those images are a silent testament to what���s now absent, but also an acknowledgement that, in the looking, something is replaced, affirmed. I was in Brussels before this whole thing kicked in with the virus, and she had an exhibit connected to a new book, My America. In it she traveled across the United States photographing sites of police violence against marginalized people in society. The walls of the gallery were filled with these photographs, with the names of the dead, their ages, the date of death, locations��� these are astounding memorials, and acts of remembrance. I look at her work as another way to consider the power of photography, but also the necessity of remembering even if there���s no visible trace of what was once there.

Along those lines, I���m indebted to the work of an Argentine photographer by the name of Gustavo Germano. The first time I looked at his photographs, they stopped me in my tracks. He works from childhood photographs of people who had been disappeared by the Argentine dirty wars. For example, in a photo, two brothers are running down a hill and they���re young, maybe 10 years old. One of them eventually, years later, was disappeared by the military. Germano photographs the surviving brother on the same hill and captures the same run and then puts those photographs together. You see, very starkly, the absence of that other sibling, the absence of so many memories that make up a life.

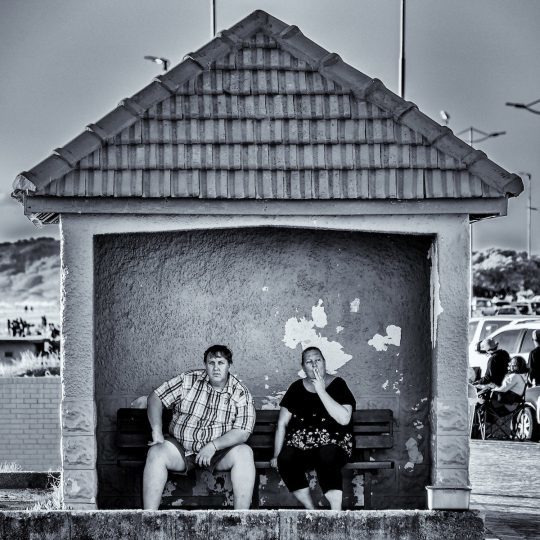

Image credit Maaza Mengiste.

Image credit Maaza Mengiste.Speaking of these disappearances, there���s a wonderful Chinese photographer named Zhang Dali who has published a photobook called A Second History. He considers the propaganda photographs that were printed in the news during the Mao Tse Tung era. He is looking at the manipulation of photos as a way to revise history and collective memory. He shows you what was printed in a newspaper and what was actually the real photograph. It���s fascinating, the way people who were out of favor with Mao Tse Tung were erased, and how, if the size of crowds didn���t reflect on him positively, those were added. People were shifted around, rearranged, or just eliminated. When you see those, it���s a reminder of how flexible truth is, of how fragile history, and memory, and collective memory, and fact are. If you can���t see it, how do you know it actually exists? This is a question I thought about in my book.

The work of those photographers from Africa, who were photographing the post-colonial era right when different parts of Africa were basically shrugging off Western powers. Malick Sidibe is the most obvious one, but there���s Jean Decarava, there are so many more. The life that���s in those photographs I find really exciting and inspiring. Aida Muluneh, Nader Adem, Malin Fezehai, Martha Tadesse���photographers from Ethiopia and Eritrea���are doing some incredible, innovative, sensitive work, but there are so many more that are coming up. They���ve got the cameras in their hands, they just need the assignments. They need representation and to get these agencies to call them and say, ���You���re there already, can you do the work?��� There���s Mulugeta Ayene, an Ethiopian, who just won the 2020 World Press Photo competition. His photography surrounding the Boeing crash in Ethiopia is both epic and intimate. It���s evidence of what happens when the photographer knows the culture, knows how to see and sees himself in every image made. It���s good to see some of those photographers getting recognition, but more needs to happen.

Zachary Rosen

For some time you���ve posted archival photos on Instagram connected to your research for The Shadow King, and now this collection is the foundation of a digital photo archive called Project 3541, which is described ���as an act of reclamation��� in its intimate assembly of images connected to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia from 1935-41. How do you envision the impact and growth of this project?

Maaza Mengiste

This project is a community effort in how to speak about and understand a moment in global history. This history is not just Ethiopian, it���s not just East African. It involves Italians, it involves the British, it involves people who were part of the British colonial forces from India and different places, who remember their family members who went to Ethiopia. I���m looking for some of those photographs. I would like the site to be a hub for this history���for stories. I���m well aware that most East Africans did not have access to cameras, and that the photographs they may have had from that period might have been taken by an Italian. I also have a page up, which is ���Memories Without Faces,��� where I���m asking people to contribute whatever memories they have. Inspiration for that page came from someone saying to me, ���My great uncle was taken to this prison and the last place he was seen was here. There���s no picture but how can I find out more?��� I���ve had an Italian say, ���I know my grandfather had a child by an Ethiopian woman, maybe you can help me find this person.��� And I know there are stories that are not about seeking, but acknowledging, reclaiming, and this can happen without a photograph, too. I���m really excited about this project because this book, The Shadow King, completely changed my life in a way that the first book did not. This book introduced me to a different culture, a different language, but also really introduced me to different aspects of my own history. I don���t think it���s over yet, the book is done, but this thing is not over and I think the photographs are the vehicle to moving it forward.

Eric Garner in Palestine

Image courtesy the author.

Excerpt from Greg Burris’ The Palestinian Idea: Film, Media, and the Radical Imagination (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2019). Book two in the Insubordinate Spaces series edited by George Lipsitz.

Some of the most powerful Palestinian appeals to Black radicalism have come in the form of buses. In November 2011, for instance, six Palestinians in the West Bank disrupted the governing logic of apartheid by simply boarding a bus. Imitating the historic Freedom Rides that took place across the US. South some fifty years earlier, these six Palestinians carried signs and wore T-shirts emblazoned with words such as ���dignity,��� ���freedom,��� and ���justice.��� Included in this group of Freedom Riders was a West Bank professor who writes and teaches about nonviolent resistance and a Palestinian activist who had previously studied at Stanford University with the playwright and Civil Rights Movement historian Clayborne Carson.

The Jerusalem-bound bus these Palestinian activists boarded was filled mostly with Jewish settlers, people who live in Israel���s illegally constructed colonies in the West Bank. When the bus arrived at a checkpoint, several Israeli officers entered it and demanded to see the Palestinians��� identity cards and permits. One of the Freedom Riders, Nadim Sharabati, asked a question of his own: ���Do you demand permits from settlers who come to our area?��� When one of the officers explained that he was simply following the law, Sharabati replied, matter-of-factly, ���Those are racist laws.��� When they refused to get off the bus, all six of the Freedom Riders were physically dragged from it, handcuffed, and arrested. Some of the settler onlookers called them ���terrorists,��� and one of them even told a reporter, ���This is not a Martin Luther King bus.���

Media were a central component of the Freedom Riders��� strategy. Speaking to a journalist, one of the activists���a pharmacist named Bassel al-A���raj, who was later killed by Israeli forces during a raid in March 2017���explained that the primary difference between this action and other acts of resistance was, in fact, the presence of media. Before the Freedom Riders boarded the bus, they notified several journalists about their intent, and after their arrest, they released a statement to the press comparing their action to the original Freedom Rides. It read, in part, ���Although the tactics and methodologies differ, both white supremacists and the Israeli occupiers commit the same crime: they strip a people of freedom, justice and dignity.��� A number of journalists boarded the bus with them, and news of the event was picked up by a variety of established media outlets. The Brazilian-Lebanese cartoonist Carlos Latuff also helped memorialize the event by drawing a cartoon of Rosa Parks sitting on a bus dressed as a Palestinian.

While the 2011 Freedom Ride was just a single occurrence, however, other activists in Palestine have turned it into a regular affair. Since 2012, members of the Jenin Freedom Theatre have organized an annual Freedom Bus that brings together international and local artists, academics, and activists for a one- to two-week trip through the West Bank. Sticking mostly to rural communities and villages, the Freedom Bus aims not only to connect internationals to locals but also to put members of different Palestinian communities in contact with one another, rural and urban, refugee and nonrefugee, diasporic and nondiasporic. Taking its name from the original Freedom Rides that crisscrossed the Jim Crow South, the Freedom Bus is not just a tour; it is a radical cultural event, and artists, bloggers, filmmakers, musicians (including Palestinian rap group DAM), photojournalists, and performers frequently participate. Those on the Freedom Bus take part in political demonstrations in places such as Bil���in and Nabi Saleh, where there are ongoing popular mobilization campaigns against settlements and land theft; they perform acts of community service, such as the planting of trees in the Jordan Valley and the escorting of Palestinian shepherds in the fields near at-Tuwani, where they are daily threatened by violent Jewish settlers; and they attend media and cultural events, including film screenings, musical concerts, and theatrical performances.

It is worth pointing out that several people involved with both the Jenin Freedom Theatre and the annual Freedom Bus are also intimately linked to Black radical movements in the United States. Constancia ���Dinky��� Romilly���the onetime partner of the late SNCC leader James Forman���is the president of the New York���based Friends of the Jenin Freedom Theatre. Also on its board is Dorothy Zellner, another 1960s veteran who helped Stokely Carmichael draw the original panther logo later adopted by the Black Panther Party; she more recently embarked on a university speaking tour called ���From Mississippi to Jerusalem��� in which she discussed the connections between the Civil Rights Movement and Palestine. The Freedom Bus itself has a large list of endorsers, including Angela Davis, Desmond Tutu, Alice Walker, and, before her death in 2014, Maya Angelou, and organizational supporters of the Freedom Bus include the Bronx-based Peace Poets and the Highlander Research and Education Center, the late Myles Horton���s folk school in rural Tennessee that once served as a training ground for such Civil Rights icons as Richard Abernathy, James Bevel, Septima Poinsette Clark, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, and Rosa Parks.

In March 2014, I had the privilege of joining the Freedom Bus. While the connections between it and the Black Freedom Movement were not always explicit, they lurked beneath the surface and occasionally emerged into plain view. In the village of Nabi Saleh, for instance, we met with the longtime peace and justice activists Bassem and Nariman Tamimi. Bassem has been arrested more than a dozen times and spent more than three years in jail for his involvement in organizing protests against the Israeli theft of Palestinian land. He spoke to us about his advocacy of nonviolence and the inspiration provided by other global struggles, including the Civil Rights Movement. We joined him for one of Nabi Saleh���s regular, weekly demonstrations against the gradual takeover of the village���s lands and water spring by the Jewish settlers of Halamish. Armed with only our voices, we were nevertheless met with tear gas. Children from the village, including Bassem���s daughter Ahed, often run to the front lines of these demonstrations, and while some people have criticized their participation at these potentially dangerous events, Bassem disagrees. Speaking to us afterward, he specifically pointed to the example of the Children���s Crusade in Birmingham, Alabama, of 1963, in which Black children were met with Bull Connor���s water cannons and police dogs.

Bassem���s daughter Ahed was quite young at the time of my visit in 2015, but she has since become something of a Palestinian icon. Just a few months after my trip to Nabi Saleh, her image went viral when she was photographed biting the hand of an Israeli soldier in an effort to rescue a boy that he was violently detaining. Even more significantly, in late 2017 a video of her slapping an Israeli soldier was widely distributed via social media, leading to her arrest on assault charges. For the next eight months, she remained behind bars. Remarkably, the discourse surrounding Ahed quickly became a debate about race. Some in Israel had long viewed the Tamimis with suspicion, and it was revealed that the Knesset had once even instigated a classified investigation to determine whether they were a real family or a group of Palestinian actors. According to this conspiracy theory, the Tamimis were all just playing parts, and Ahed was selected for her role because her fair skin and blond hair would elicit Western sympathy. Apparently for her Israeli critics, Ahed was simply too white.

While Knesset members were forming secret committees to solve the mystery of Ahed���s whiteness, others were instead linking her to the Black struggle. In early 2017, Ahed was invited to take part in a US speaking tour alongside Amanda Weatherspoon, a Black feminist liberation theologian. Ahed was forced to forgo the trip after the US Consulate put her visa application under a prolonged ���administrative review.��� Moreover, shortly after Ahed was arrested, a Black journalist from Philadelphia used the occasion of Martin Luther King���s birthday to author an editorial for Al Jazeera in which he compared her to Rosa Parks, and the US-based Civil Rights organization Dream Defenders released a statement likening her to Trayvon Martin, the seventeen-year-old Black martyr from Florida: ���From Trayvon Martin to Mohammed Abu Khdeir and Khalif Browder to Ahed Tamimi���racism, state violence and mass incarceration have robbed our people of their childhoods and their futures.��� The statement was signed by many Black artists, academics, and activists, including Michael Bennett, Angela Davis, Danny Glover, Jasiri X, Robin D. G. Kelley, Alice Walker, and Cornel West.

But to return to the Freedom Bus trip of 2015, one of the strongest manifestations of Black radicalism I witnessed took place in al-Hadidiya, a small village in the Jordan Valley that sits just a few hundred yards from the fortified Jewish settlement of Ro���i. We gathered together under a makeshift tent with the longtime activist Abu Saqr and other village residents for a performance of improvisational ���Playback Theater��� in which the Palestinian actors listened to stories from the audience and interpreted them on the spot. Most of that day���s performances involved incidents of Israeli oppression���namely, confrontations with the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and Jewish settlers. Toward the end of the performance, however, one of the Freedom Bus riders, a young African American woman, related the story of Eric Garner, the unarmed, Black New Yorker who broke up a fight in the summer of 2014, only to be approached by five police officers and tackled to the ground. As he collapsed underneath the force of a chokehold, Garner repeated the words ���I can���t breathe��� eleven times before losing consciousness and dying. The entire event was recorded on video and widely shared on social media, but a grand jury refused to indict any of the officers who murdered him. There, in a tent in al-Hadidiya, amidst squawking chickens and bleating sheep, the Palestinian actor Motaz Malhees reenacted this saga, contorting his face to emulate Garner���s final fatal moments. Most of the Palestinians in the audience had not heard the story of Garner, and seeing this tale of racist US aggression reinterpreted in the context of Zionist settler-colonialism was powerful and moving. It was a moment in which the idea of tying together the oppressed communities of both countries became tangible, a moment in which transnational Black solidarity became more than mere specter.

May 20, 2020

Predisposed to chaos

People take precautions against COVID-19 in Mali. Image credit Ousmane Traore (MAKAVELI) via World Bank photo collection on Flickr CC.

Since early March of this year, we have been inundated with articles and opinion pieces about the ensuing doom of the novel coronavirus and its deadly disease COVID-19 soon to drive the continent of Africa into collapse. As I read the seemingly endless predictions of the ensuing chaos, in both African and western media, as an American in Khartoum, I am reminded of Saidiyah Hartman���s 1997 Scenes of Subjection. Reflecting on the violent spectacles that maintained the institution of slavery in the United States, she asks a series of questions relevant to what Simon Chikugudu has recently described as framing the experience of COVID-19 in Africa as a ���catastrophe-in-waiting.��� Hartman���s opening questions inspire me to ask a similar series of questions. In what ways are we compelled to cooperate with this dominant narrative of an Africa congenitally predisposed to chaos? Are we voyeurs fascinated with and repelled by the satisfaction of the presumed trajectory of global death and disease? What does the exposure of the material shortcomings of African health systems yield? Proof of African mortality, that the affluent world will not suffer alone, or the inhumanity of the system of global capital that transported this disease around the world laying bare the fragility of world-spanning chains of production?

While today the number of cases in the continent begins to exceed 70k, this number, even tripled, pales in comparison to the number of confirmed cases in the affluent worlds of northwestern Europe and the US. The focus of the WHO and the global media has been on the inadequate health systems and national economies throughout much of the continent. WHO director general Tedros Adhanom warned Africa to ���wake up��� to the coronavirus threat, citing the deadly potential of an unmitigated outbreak. Yet, if we situate this sentiment in the genealogy of how African states have been inculcated into the global political economic system, we can, following Hartman, interrogate how we understand the concept of an independent African government to be a ���rational, acquisitive, and responsible��� subject capable of responding to a global crisis. That is to say, we can begin to peel back the layers of our own racialized logic that situates the healthy, strong, rational, bourgeois self outside of Africa. This ideal self animates the ever-unfinished project of whiteness that recruits the university-educated, wealthy and propertied all over the world.

Given the comparatively slow spread of the novel coronavirus on the African continent, there is nevertheless a marked refusal to entertain the possibility that the facts on the ground in Africa may represent a reversal of the global trajectory of sickness and deprivation. It is incumbent upon us to ask what animates this refusal. Why, in this context, have so many dominant voices refused the facts on the ground in lieu of their own expectations? At a foundational level, this refusal seems to emanate from a similar site as what Liisa Malkki has called ���the need to help��� which animates the humanitarian enchantment with the ���world outside��� of the global north. Yet this need, she argues, is remarkably domestic. If we refuse to accept a scenario in which the geography of the ���needy��� has shifted under our feet, it reveals our desire to escape back into a familiar world in which residents of the affluent world can continue to engage in the fantasy of their own immortality. When western media houses recruit African professionals, medical workers and intellectuals, to confirm dominant narratives of impending doom, it fetishizes predictions of a future reality such that they become more valuable and more real than the reality in which we are living.

Yet, as Arundthati Roy and others have pointed out, this virus has followed the trails blazed by international trade and global capital. This pathway has not only frustrated the common sense of who should be falling ill and where widespread death should be taking place, but also, by extension, the very notion of the bourgeois self. The affluent world should be safely sheltering-in-place, sending its thoughts, prayers and donations to Africa rather than reeling from a global pandemic. Despite the facts on the ground that continue to tell us a new and complex story of health and humanity in the context of COVID-19 in Africa, the strength of our desire to right the course of global death reveals the profound destabilization in how we understand ourselves to be healthy, rational and responsible citizens of organized, albeit flawed, state governments. Our nutritious diets, vaccinations and long life-spans allow us to look into the mirror and see a super-human. If we are suffering and they are not, it must only be a matter of time. If not, it would be a matter of humanity. As this disease undermines our sense of security generated by hyper-modern medical technology and expensive privately-owned hospitals, the movement of sickness from over there to right here, threatens the presumption that the affluent shall inherit the world. That world may not last.

Due to decades of global public disinvestment in health and education, there was no preparation for this virus anywhere. Yet, the common sense of where sickness and deprivation should take place, has reconfigured Africa���s unpreparedness as both anomalous and insurmountable. Even as so many African nations have instituted screening and mitigation measures since February, the dominant logic peers into the unseen as though these efforts will amount ultimately to very little. The insistence on predicting a catastrophe-in-waiting reproduces the need for us, our expert knowledge, our superior management capacities, and seemingly endless funding streams that consolidate our sense of self as needful rather than needy. We want to escape into a future to grasp the normal order of things and reassure ourselves that we are in fact still the global north, a safe haven from the chaos of the world outside. This self-narrative has served to assuage the anxieties of the affluent world about its own monstrous self, ill-prepared to maintain the very system meant to indemnify it against destruction.

Arundhati Roy insisted that the pandemic is a portal and it is up to us how we choose to walk through it, either with our prejudices and dead ideas intact or ���with little luggage��� ready to envision a new world. Following this, the spread of the coronavirus also presents us with an opportunity to draw attention to the global understanding of the living geography of health, i.e. who is healthy, and where health takes place. In order to walk through the portal as Roy imagines we could, we must be willing to do so. That is to say, rather than searching for solace in the African catastrophe-in-waiting, we should reckon with the extent to which the presumption of sickness and death in Africa is foundational to the myths that residents of the global north will live nearly forever, that expansive chains of global production insulate them from���rather than expose them to���the health threats of the natural world, that ���hygiene��� is an outstanding issue to be solved elsewhere, and that because Euro-Americanness is synonymous with health and medicine, the rest of the world needs it to survive.

The complex history of skin lighteners

Mogadishu, Somalia. Image credit Tobin Jones for AMISOM via Flickr CC.

Somali-American activists recently scored a victory against Amazon and against��colorism, which is prejudice based on preference for people with lighter skin tones. Members of the non-profit The Beautywell Project teamed up with the��Sierra Club to convince the online retail giant to stop selling skin lightening products that contain��mercury.

After more than a year of protests, this coalition of anti-racism, health, and environmental activists persuaded Amazon��to remove some 15 products containing toxic levels of mercury from its website. This puts a small but noteworthy dent in the global trade in skin lighteners, estimated to reach US$31.2 billion by 2024.

What are the roots of this sizeable trade? And how might its most toxic elements be curtailed?

The online sale of skin lighteners is relatively new, but the in-person traffic is very old. My��book��Beneath the Surface: A Transnational History of Skin Lighteners��explores this layered history from the vantage point of South Africa.

As in other parts of the world colonized by European powers, the politics of skin color in South Africa have been significantly shaped by the history of white supremacy and institutions of racial slavery, colonialism, and segregation. My book examines that history.

Yet, racism alone cannot explain skin lightening practices. My book also attends to intersecting dynamics of class and gender, changing beauty ideals and the expansion of consumer capitalism.

A deep history of skin whitening and skin lightening

For centuries and even millennia, elites in some parts of the world used paints and powders to create smoother, paler appearances, unblemished by illness and the sun���s darkening and roughening effects.

Cosmetic users in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome created dramatic appearances by pairing skin whiteners containing lead or chalk with black eye makeup and red lip colorants. In China and Japan too, elite women and some men used white lead preparations and rice powder to achieve complexions resembling white jade or fresh lychee.

Melanin is the biochemical compound that makes skin colorful. It serves as the body���s natural sunscreen. Skin lighteners generate a less painted look than skin whiteners by removing rather than concealing blemished or melanin-rich skin.

Active ingredients in skin lighteners have ranged from acidic compounds like lemon juice and milk to harsher chemicals like sulfur, arsenic, and mercury. In parts of precolonial Southern Africa, some people used mineral and botanical preparations to brighten���rather than whiten or lighten���their hair and skin.

During the era of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, skin color and associated physical differences were used to distinguish enslaved people from the free, and to justify the former���s oppression. Colonizers paired pale skin color with beauty, intelligence, and power while casting melanin-rich hues as the embodiment of ugliness and inferiority. Within this racist political order, where small differences carried great significance, some people sought to whiten and lighten their complexions.

By the twentieth century, mass-produced skin lightening creams ranked among the world���s most popular cosmetics. Consumers of commercial skin lighteners included white, black, and brown women.

In the 1920s and 1930s, many white consumers swapped skin lighteners for tanning lotions as time spent sunbathing and playing outdoors became a sign of a healthy and leisured lifestyle.��Seasonal tanning��embodied new forms of white privilege.

Skin lighteners became cosmetics primarily associated with people of color. For black and brown consumers, living in places like the United States and South Africa where racism and colorism have flourished, even slight differences in skin color could have substantial social and political consequences.

The mercury effect

Skin lighteners can be physically harmful. Mercury, one of the most common active ingredients, lightens skin in two ways. It inhibits the formation of melanin by rendering inactive the enzyme��tyrosinase;��and it exfoliates the tanned, outer layers of the skin through the production of��hydrochloric acid.

By the early twentieth century, pharmaceutical and medical textbooks recommended mercury���usually in the form of ammoniated mercury���for treating skin infections and dark spots while often warning of its harmful effects. Cosmetic manufacturers marketed creams containing ammoniated mercury as ���freckle removers��� or ���skin bleaches.���

When the US Congress passed the��Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act in 1938, such creams were among the first to be regulated.

After World War II, the negative environmental and health consequences of mercury became more apparent. The devastating case of��mercury poisoning��caused by industrial wastewater in Minamata, Japan prompted the Food and Drug Administration to take a closer look at mercury���s toxicity, including in cosmetics. Here was a visceral instance of what environmentalist��Rachel Carson��meant about small, domestic choices making the world uninhabitable.

In 1973, the FDA banned all but trace amounts of mercury from cosmetics. Other countries followed suit. South Africa banned mercurial cosmetics in 1975, the European Economic Union in 1976, and Nigeria in 1982. The trade in skin lighteners, nonetheless, continued as other active ingredients���most notably��hydroquinone���replaced ammoniated mercury.

Meanwhile in South Africa

In apartheid South Africa, the trade was especially robust. Skin lighteners ranked among the most commonly used personal products in black urban households. During the 1980s, activists inspired by��Black Consciousness��and the ���Black is Beautiful��� sentiment teamed up to make opposition to skin lighteners a part of the��anti-apartheid movement.

In the early 1990s, activists convinced the government to��ban��all cosmetic skin lighteners containing known depigmenting agents���and to prohibit cosmetic advertisements from making any claims to ���bleach,��� ���lighten��� or ���whiten��� the skin. This prohibition was the first of its kind and the regulations immediately shuttered the in-country manufacture of skin lighteners.

South Africa���s regulations testify to the broader anti-racist political movement from which they emerged. Thirty years on, South Africa again possesses a robust���if now illicit���trade in skin lighteners. An especially disturbing element of the trade is the resurgence of mercurial products.

South African researchers have found that over 40 percent of skin lighteners sold in��Durban��and��Cape Town��contain mercury. Mercurial skin lighteners tend to surface in places where regulations are lax and consumers are poor.

The activists��� recent victory against Amazon suggests one way forward. They took out a full-page ad in a local newspaper denouncing Amazon���s sale of��mercurial skin lighteners��as ���dangerous, racist, and illegal.��� A petition with 23,000 signatures was hand-delivered to the company���s Minnesota office.

By combining anti-racist, health, and environmentalist arguments, activists held one of the world���s most powerful companies accountable. They also brought the toxic presence of mercurial skin lighteners to public awareness and made them more difficult to purchase.

May 19, 2020

Financing Africa���s COVID-19 response

COVID-19 testing in Madagascar. Image credit Henitsoa Rafalia via World Bank Flickr CC.

African governments need unprecedented amounts of money to deal with the coronavirus pandemic and its economic fallout. Most policymakers, scholars and economic justice activists agree on the need for greater debt relief and monetized public spending. Both policies aim to increase the resources governments have at their disposal to address the conjoined public health and economic crises. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) estimates a best-case scenario of 300,000 deaths and a 1.8 percent increase in GDP, and a worst-case of over 3 million deaths and a 3.6 percent drop in GDP���plunging an additional 37 million Africans into poverty. We need swift, bold and decisive action on debt relief and monetary creation in Africa in order to face the coronavirus crisis. African finance ministers are calling for US$100 billion for health spending and debt relief and $100 billion for economic recovery���together less than 8% of Africa���s 2019 GDP. This is likely an underestimate; much more money will be necessary.

Africa is expected to be among the worst hit regions given the weakness of its public health systems. One-third of Africa���s population lacks access to running water and over three hundred million Africans live in crowded slums. Most African workers are in the informal sector, with no safety net, and few can work from home. After decades of neoliberal austerity and privatization, Africa���s public health systems are ill-prepared to deal with the surge of COVID-19 cases. There are shortages of protective equipment like masks and gloves, and even basics like running water and soap. The World Health Organization estimates that there are about 5,000 beds in intensive care units in 43 African countries, and fewer than 2,000 working ventilators, compared to more than 170,000 in the United States.

African governments are among the most fiscally constrained, with the lowest tax collection rates and highest borrowing costs in the world. Of the US$8 trillion pledged by governments for recovery, G-20 nations account for 90 percent. South Africa is the only African member of the G-20, and its government announced a R50 billion package worth 10 percent of GDP. Excluding South Africa, ���the average fiscal-support package announced by African governments so far amounts to a meager 0.8% of GDP, one-tenth the level��� of G-20 countries. African governments can expect much lower revenue this year due to shutdown businesses not paying taxes, reduced export earnings as the global economy contracts and capital flight as foreign investors flee���which will spark devaluation and raise the value of foreign debt. Many governments already had high levels of debt before the crisis, with repayments consuming over 20 percent of fiscal revenue in several countries. In 2017, total debt for 44 governments in sub-Saharan Africa was 160 billion, with 90 billion denominated in foreign currencies. Multilateral lenders like the IMF and World Bank hold half of that external debt, the Chinese government is likely the region���s second largest foreign lender, and the rest is held by Western governments and private bondholders.

While the IMF and several governments have pledged to suspend debt payments in 2020 for poor countries, the amounts proposed, so far, are insufficient. The G-20, led by France, announced $20 billion in suspended debt payments for 76 poor countries���including 40 in Africa���that are eligible for concessional lending through the World Bank. This still leaves another $12 billion in payments due. It also excludes highly indebted, middle-income countries like Angola. The IMF promised to cancel debt service payments worth up to $500 million to 25 of its poorest borrowers, many of them in Africa.

In addition to joining the growing consensus for a moratorium on debt service for 2020 and 2021, international NGOs like Eurodad, Jubilee Debt Campaign and the Transnational Institute, are also advocating for significant reductions of debt principal. UNCTAD, for example, is promoting a ���Marshall Plan for Health Recovery��� for low and middle-income countries of $2.5 trillion���roughly equivalent to the amount OECD nations have pledged in annual development aid. It would include $1 trillion for debt relief���50 times what the G-20 recently promised���and $500 billion in grants for health spending. In addition, they highlight the need for capital controls to stem capital flight.

There has also been a remarkable consensus forming on the need for the IMF to create (international reserve) money to help African governments finance recovery. Rich countries have decided to monetize fiscal spending, with governments running massive deficits and central banks agreeing to buy government bonds in unlimited amounts. The conventional wisdom on the monetization of government spending has shifted tremendously in the last few weeks. Governments in the global south, however, cannot meet all their needs through domestic money creation since they need ���hard currency��� (dollars, euros, yen, etc.) to pay for urgent imports of medical equipment and supplies. The IMF created its own quasi-money, the ���Special Drawing Right��� in the late 1970s after the breakdown of the Bretton Woods regime of fixed exchange rates. Global south governments could convert SDRs to dollars and euros to buy the essential goods they cannot produce domestically.

While most economists are debating the appropriate amount of SDR creation, the Trump administration opposes it altogether. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin argues it is too blunt an instrument. The IMF���s allocation formula���based on the size of national economies���would give 70 percent of new SDRs to rich countries that do not need it. Indeed, the last time the G-20 agreed to SDR creation, adding 183 billion SDRs (US$287 billion) in response to the global financial crisis in August 2009, all of Africa received 15 billion SDRs (and South America about 16 billion). Instead of creating SDRs, the Trump administration prefers donor governments contribute to IMF���s traditional lending programs with their usual neoliberal conditions. Nonetheless, even Larry Summers (notorious for once arguing that Africa was ���under polluted��� while chief economist at the World Bank) is calling for 500 million in new SDRs, and blasted the obvious double standard of the Trump administration���s decision as: ���It���s whatever it takes for us and crumbs off the table for the world.���

In response to the allocation problem, UNCTAD proposes 783 million in new SDRs ($1 trillion) but paired with a temporary reallocation of SDRs where rich countries donate their SDRs. Progressive economists like Andres Arauz contend, however, that ���We have no time to make the allocation shares more just, but we have no restriction as to the amounts issued.��� He therefore ambitiously proposes the creation of 4 trillion SDRs ($5 trillion). Even with the IMF���s skewed formula, this would provide approximately 350 trillion SDRs ($475 billion) for Africa. The US Federal Reserve could also simply provide dollars to central banks in Africa via swap lines���either directly or indirectly via the IMF���but such international cooperation is only extended to a handful of other ���major��� countries whose financial collapse would hurt the US economy.

The financial resources available to African governments is only half the equation, however. Equally important is how the money is spent. The Ramaphosa government���s relief package, for example, is less impressive than the headline number. Much of it is not additional spending���merely repurposing public funds���while only half is dedicated to health spending and income support for the country���s poor majority. The other half is devoted to loan guarantees and tax deferments.

Progressive activists and intellectuals across the continent and its diaspora are demanding that African governments spend the money necessary to ensure the response is proportionate to the scale of the disaster. These funds must be used to protect the health and incomes of the poorest and most vulnerable. While taxing the rich and domestic monetary creation are also essential elements of financing the response to the pandemic, we must also stop the drain of foreign debt service and increase African governments��� access to hard currency. If governments and banks in North America, Western Europe and China choose to squeeze African governments for debt payments and hinder their ability to finance a robust recovery, then millions of Africans will be forced to pay for this crisis through more illness, unemployment, hunger and unpaid care work, and for many, ultimately with their lives.

Invitation diplomacy

[image error]

Ahmed Se��kou Toure��. Still from film.

��� Tycho van der Hoog, Monuments of PowerNorth Korea developed an ���invitation diplomacy,��� meaning that more goodwill missions from Africa to North Korea existed than the other way around. The North Korean state, however, took the initiative. Furthermore, the diplomatic style was characterized by cultural, rather than trade diplomacy.

Visual artist Onejoon Che���s documentary Mansudae Master Class (2016) offers a unique insight into the relations of Democratic People���s Republic of Korea (DPRK, also known as North Korea) with several African countries through the lens of monuments and buildings constructed by the overseas project division of the Mansudae Art Studio, the country���s largest art studio. This architectural diplomacy has been the subject of some recent scholarship, including a 2019 monograph on nationalist monuments in Zimbabwe and Namibia, and Che���s own chapter in a recent compendium of essays on revolutionary iconography. Yet, the film provides unseen in-depth exposure to the historical and ongoing relationship.

Mansudae Overseas Projects, the international commercial division of the Mansudae Art Studio, was started in 1974 by then- president Kim Il-sung, at which time it only charged travel fees of clients. Youngwhan Kho���the former North Korean Director of Central Africa Affairs in the 1980s, who sought asylum in South Korea in 1991���explains in one of the film���s interviews that the Tiglachin Monument in Addis Ababa (inaugurated in 1984 but now in disrepair) was built free of charge because General Mengistu Haile Mariam (who brutally ruled Ethiopia between 1977 and 1991) was a pro-North Korean leader. Kho further notes that Kim Jong-Il, North Korea���s second leader, instituted fees for the projects and that they served as a major source of foreign currency.

The 40-minute film is a three-channel video installation, and features interviews, archival footage and panoramic shots of various monuments, often placed side-by-side so that the viewer can see the architectural work being discussed. Especially insightful are the interviews with locals: ranging from Samuel, a security guard at the then under-construction Independence Memorial Museum in Windhoek, Namibia, attesting to the North Koreans being ���skillful��� and ���heavy duty��� architects, to Oustaz Alioune Sall, a local imam in Dakar lambasting the Senegalese government���s investment of CFA14 billion in the nearby DPRK-built African Renaissance Monument, when the money could have been used to create local jobs ���for the young who left this country by sea to go to Spain.��� The shots of Dakar���s outskirts that flank the middle screen���showing the flooding that Sall talks about using the money to fix instead���give the impression that Sall is not the only Dakarois who is more than indifferent about the nearby monument.

Kho is featured prominently in the film, taking a relatively balanced stance on the Mansudae Overseas Projects. While denouncing (alongside Zimbabwean artist Owen Maseko) the DPRK���s assistance to Robert Mugabe���s military forces (which were subsequently used to quash his opposition throughout the 1980s, most notably the murder of more than 20,000 people following independence), Kho explains the motivations of the inter-Korean diplomatic war in Africa as revolving around the DPRK���s desire to amass United Nations votes to oust foreign troops (particularly American ones) from South Korea, adding that the DPRK���s channeling of huge funds to Africa resulted in North Korean children being unable to even ���afford a candy bar.��� Indeed, the Republic of Korea (ROK) also spearheaded similar projects in competition, and the film profiles Jintaek Rho, South Korean former owner of the ROK-built Renovation Department Store in Libreville, echoing Kho in recounting that Gabon���s allegiance���and even that of neighboring countries Cameroon and Republic of Congo���shifted from Pyongyang to Seoul, following then president Omar Bongo���s visit to Seoul and the ROK���s construction project in Libreville.

Che utilizes the three-channel format to display newspaper clippings of support for the DPRK���s desire for withdrawal of foreign troops endorsed by the governments of Mali, Namibia and Uganda. The dominant narrative of the DPRK cozying up to African dictators is partially corroborated by various testimonies lambasting the DPRK���s aid to such leaders, while more anecdotal episodes���such as former Togolese President Gnassingb�� Eyad��ma bursting into tears when Kim Il-sung offered him ginseng to treat a knee injury (recounted by Kho)���add fascinating details not seen in newspaper or academic treatments of this relationship.

Che captures a wide variety of reactions to and analyses of the Mansudae Overseas Projects, resisting simplistic narratives of the projects as ���financial lifelines.��� These range from laconic quips of disapproval like ���they made [Lumumba���s statue] fat when he was not fat in reality��� (Paul Bakwlufu Badibongo, deputy director of the National Museum of Kinshasa), or stronger critiques of ���cheap materials and shoddy workmanship��� (John Grober, an investigative journalist in Namibia), to praise like ���heroic��� and ���has withstood the test of time��� (Doreen Sibanda, the executive director of the National Museum of Zimbabwe) juxtaposed ironically with ���one of these monuments that nobody goes to��� (Grober)���both in reference to the DPRK-built National Heroes Acre in Harare.

The film ends with shots of the Catholic Church of Repentance and Atonement in the border city of Paju, South Korea, featuring priest Geunsun Jang, the son of Pyongyang parents who left during the war, speaking impassionedly about the need for reconciliation and forgiveness of crimes committed on both sides of the war. Overall, the film provides an illuminating, nuanced portrait of a unique transcontinental relationship that resists easy classification. Indeed, in the very same film it is characterized both as a relationship ���of beautiful love��� (Christian Ndong Menzamet, Gabonese artist) and ���an insult, more than anything��� (Michael Nkomo, Zimbabwean politician). Extensive first-hand detail and assiduous analysis on topics subject to such politicization are always welcome.

May 18, 2020

Ending the polarization around South Africa���s lockdown

President Cyril Ramaphosa receives PPEs from Naspers. Image credit GCIS via Flickr CC.

The debate around the management of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa is becoming increasingly polarized. While South Africans were initially broadly united around Cyril President Ramaphosa���s swift and radical proclamation of a National State of Disaster in mid-March, and the sweeping stay-at-home order that followed, we are now in a situation where every aspect of the regulations pertaining to the current ���Level 4��� is being noisily debated.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Fierce contestation of government decisions is part of a healthy democracy. Unfortunately, the debate is now polarized along unhelpful lines: it is being constructed as a binary choice between ���saving lives��� and ���saving livelihoods���; between prioritizing between the political imperatives of fighting the pandemic and the needs of ���the economy���; between solidarity and self-interest; between ���left��� and ���right.���

To make matters worse, some of those within the government who are defending the lockdown regulations are framing the debate as a contest between expertise deployed in the service public good versus ignorance and privilege: as if concerns about the regulations are simply reflecting the views of armchair epidemiologists and middle class whites mainly concerned with their own selfish interests. A regrettable example is the opinion piece recently published in the Daily Maverick by Saul Musker, a speechwriter within the South African Presidency. Musker���s piece dismissed the rising tide of dissent about current regulations as the fulminations of a bunch of uninformed amateurs. He argued that these critics were ���endangering society������and doing so ���on the basis of little more than a hunch, an intuition, or an article they saw in the Wall Street Journal.��� South Africa, Musker warned, should not merely be governed for Claremont but for Khayelitsha as well. (Claremont is a wealthy, middle class and mostly white suburb in the middle of Cape Town and an important center of financial and retail capital. Khayelitsha is a sprawling and impoverished black settlement on the outskirts of Cape Town.)

But the reality is that the voices of concern are not only coming from Claremont. They are coming from all over the country. The choice is not between the lockdown and the economy. The real danger is that poorly conceptualized and implemented lockdown regulations will fail on their own terms. They will not help stop the virus, they are causing great economic damage���and they risk leading to a dangerous crisis in relations between the state and those it means to protect.

There are two basic problems with the conceptualization and the implementation of South Africa���s COVID-19 lockdown. The first is that stay-at-home regulations of the kind implemented in China and emulated across much of the world presuppose the existence of a resilient economy with high levels of stable employment and a strong social safety net. With those elements in place, it is indeed possible for people to shelter at home and minimize their social interactions.

But those conditions aren���t present in South Africa. We are one of the most unequal societies on the face of the planet. More than a third of our population are landless, un- or underemployed, and frighteningly vulnerable. Many depend on a fragile and tenuous informal economy, and on the distribution of scarce resources through thinly stretched and overburdened social networks. Waste-pickers, domestic workers, and informal traders cannot work from home. For this population, the lockdown has been ruinous. Their primary concern is not the pandemic. For 25 years or more, they have already been living in a crisis of ill-health, poverty, and food insecurity. But that crisis has now become all-encompassing. For millions of households, hunger has for decades been a perpetual ghostly presence, always knocking on the door. Now it is inside the house. Palliative measures have brought some limited relief, but they are not nearly enough.

The second problem with the lockdown has been that it has depended on an excessively technocratic vision of government action. The lockdown has unfolded within an imaginary of hyper-development���as if we lived not in South Africa, but in South Korea or Singapore. The regulations assume a highly capable state, proceeding on accurate, clear and up-to-date information, and engaging seamlessly with a formalized and responsive economy and a compliant and trusting citizenry.

But none of those conditions resonate. The South African state is weak and dysfunctional. Data (both epidemiological and economic) are partial and incomplete. Large reaches of our society are invisible to economic planners and epidemiologists alike. And the population is vulnerable, mobile and defiant: dependent on the state but also often highly distrustful of it.

To make matters worse, the conditions prevailing in the informal settlements, impoverished villages and rural slums where a large section of South Africa���s population live, are not conducive to the implementation of basic safety measures. People live in crowded and unsanitary conditions, local health systems are fragmented and overloaded, basic water and sanitation is lacking, and local government systems are in tatters.

This is a frightening state of affairs: where community transmission is established, and where implementing social distancing is difficult, any workable politics of life in response to COVID-19 depends on the active and voluntary cooperation of the citizenry. This is the lesson we learned (or should have learned) from the HIV/AIDS pandemic: fighting a disease like this requires a democratic politics of public health, a social movement that engages people as not as objects of biomedical management, but as partners in their own well-being and that of the people around them.

This we have thus far failed to do. Instead, we have irrational regulations, often brutally enforced by poorly trained police and army. The government is seeking to regulate the sale of tobacco and the conditions under which T-shirts may be bought, while dense gatherings conducive to the spread of the virus are being permitted (e.g. at funerals) or actively solicited (queues for social grants or food parcels). Meanwhile the looming economic meltdown threatens to overwhelm the fragile coping mechanisms that South Africa���s poor populations have relied on thus far. There is a danger that this crisis could fatally undermine the legitimacy of the lockdown regulations themselves. In the long run, it is likely to imperil the social contract at the heart of our democracy, creating deep political problems for decades ahead.

In his live-streamed address on the evening of May 13, President Ramaphosa struck a grave and conciliatory tone, warning South Africans about the threat to life posed by the epidemic, acknowledging the hardship imposed by the lockdown, and admitting that his government has made mistakes. Again, we had the opportunity to contrast his dignified and measured approach with the cynicism and incompetence on display elsewhere in the world. But the difficult questions about the advisability and the fitness for purpose of the current approach to the management of this pandemic will not go away.

In a way, despite the heat and noise generated by many of Ramaphosa���s critics, they underestimate just how deep in trouble we are. We are not in a situation where we need to choose between saving lives and protecting livelihoods. It is far worse. We are in danger of losing both. It may feel comfortable or virtuous to point a moralizing finger at the ridiculous figure of right-wing radio host, Gareth Cliff, or to censure the middle class whites of Claremont. But the stakes are far higher. The lion is already among the cattle. Our whole society is in danger. It is time to think again.

Feminist organizing on digital platforms

Rosebell Kagumire (in focus). Image via

Chapter Four Uganda Flickr CC.

This post is part of our series ���Talking back: African feminisms in dialogue.��� It is dedicated to guest editor Rama Salla Dieng���s late sister, Nd��ye Anta Dieng (1985-2019).

Below is a conversation with Rosebell Kagumire, a writer, award-winning blogger, pan-African feminist, socio-political analyst, and the curator and editor of the African Feminism website.

Rama Salla Dieng

Hello Rosebell, please tell us who you are, and what led you to your activist work?

Rosebell Kagumire

I am a Ugandan journalist and rights defender. I came to my activism work through my journalism, traveling across Uganda and experiencing various inequalities and issues that persisted among everyday Ugandans. I worked on stories on justice after the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) war in northern Uganda, the peace talks between the LRA and government, covered stories from health to political prisoners before going into my masters. That���s what informed my expanded view of struggle, and understanding that our struggles are linked. This extended to various oppressions we face as women, as a country or as a continent.

Rama Salla Dieng

You worked in multimedia communication and blogging before, what lessons did you learn from that experience?

Rosebell Kagumire

I have always been opinionated even as a child. I was always curious and learning beyond the limits. So while working as a journalist I noticed earlier in my career that my voice was not that present in the mainstream way of covering stories. I always felt I had a story, an observation, a question that would not end up in the paper or in a TV story. Therefore, I started to blog as a way to make my own stances, share lessons, journeys out of various trips, encounters and experiences. It was from documenting my own thoughts that led me to really learn more about the issues I was covering and why the situation was the way it is beyond official explanations. I was able to learn more from people that have long theorized issues that I was trying to understand or thought I understood.

Rama Salla Dieng

What is the African Feminism website?

Rosebell Kagumire

It���s a collaborative platform of African feminist writers who document their own journeys and experiences of women in their communities, countries. To be able to share them on the same platform, we learn from each other and about each other. The coverage of African women in the mainstream media continues to be lacking and often problematic. Most Africans still learn about the other parts of the continent through information produced via western media. We thought this would be a platform aided by social media for us to understand our collective struggles and achievements as African women on the continent and in the diaspora. We welcome feminist writing from all women on the continent, and especially shedding light on those issues we would not usually see represented in the mainstream. We also notice that we have great African feminist academic work but we still lack the bridges to bring it down to ordinary women and girls, to relate their experiences to the larger systems in which we live.

Rama Salla Dieng

African Feminism was created as a ���a pan-African feminists digital platform and collaborative writing project between African ��authors/writers����with the long-term ambition of bringing on board at least one feminist voice from each country on the continent.��� How achievable is a pan-African feminist agenda, with digital platforms being potential, as Dr. Cornells West said, ���weapons of mass distraction���?

Rosebell Kagumire