Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 178

May 10, 2020

Announcing the Progressive International

Students at one of South Africa's universities protest for free public higher education and against persistent racism in 2015. Image credit Nicholas Rawhani.

Never before has international solidarity been more necessary���and more absent.

The COVID-19 crisis is deepening everywhere, hitting hardest among the world’s poor. Meanwhile, disaster capitalism is on the rise, as financial speculators and transnational corporations seek to profit from the pandemic. Standing behind them are the forces of the far right, who exploit the crisis to advance an agenda of bigotry and xenophobia.

And yet, at this historic juncture, internationalism has gone missing in action.

The pandemic has laid bare the fatal flaws of ���hyper-globalization���: the breakdown of just-in-time production���coupled with diminished state capacity and a public sector eroded over a half-century of privatization���has ravaged domestic responses to the health crisis.

Yet the widely heralded return of the nation-state will neither end the pandemic nor prevent its political fallout from strengthening the hand of the far right. After all, most countries around the world not only lack basic medical equipment; they also lack the currency to acquire it. Internationalism, for the vast majority of humanity, is not a privilege, but a basic necessity. “The most dangerous illusion,” writes Mike Davis, “is the nationalist one: that a global depression can be avoided by a simple sum of independent and uncoordinated national responses.”

Only a common international front can match the scale of our crises, reclaim our institutions, and defeat a rising authoritarian nationalism.

That is why, on 11 May, we are launching the Progressive International, a global initiative with a mission to unite, organize, and mobilize progressive forces around the world.

In December 2018, the Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25) and the Sanders Institute issued an open call to form a common front in the fight against the twin forces of fascism and free market fundamentalism. “It is time for progressives of the world to unite,” proclaimed the open call. The year that followed has been described as a ‘Wave of Global Protest.��� From Delhi to Paris, Santiago to Beirut, citizens rose up to defend democracy, demand a decent standard of living, and protect the planet for future generations.

2020 is the year that we unite these disparate protests in a Progressive International, bringing together activists and organizers, trade unions and tenant associations, political parties and social movements to build a shared vision of democracy, solidarity, and sustainability. The May launch brings this platform to life, inviting individuals and organizations around the world to become members of the PI and build the movement together.

At launch, the Progressive International is supported by an interim Council of over 40 advisors, including Katri��n Jakobsdo��ttir, Fernando Haddad, Aruna Roy, Noam Chomsky, Vanessa Nakate, Vijay Prashad, Carola Rackete, Yanis Varoufakis, Elizabeth G��mez Alcorta, Pierre San��, Naomi Klein, Varshini Prakash, and many others. In September, the Council will meet for the inaugural Summit of the PI in Reykjavik, Iceland, hosted by the Prime Minister of Iceland and the Left-Green Movement, to analyze the challenges of the 21st century and consider proposals from the PI membership for its strategic direction.

In the meantime, the activities of the initiative are divided across three pillars. The Movement aims to forge a global network of activists and organizers that can coordinate the work across borders. The Blueprint convenes activists, thinkers, and practitioners to develop a policy blueprint for a progressive international order. And the Wire offers a wire service to the world’s progressive forces, partnering with publications around the world to bring grassroots perspectives to a global audience.

All of this work aims to build from past efforts at international organization���and to learn the lessons from both their successes and their failures.

Unlike past internationals, the PI is not restricted to any one kind of organization, or any one kind of struggle. Political parties do not have a monopoly on political organization, and a 21st century international must reflect the diversity of associations in our lives. That is why the PI aims to bring together all progressive forces���from trade unions and tenant organizations to liberation movements and underground publications���to contribute to a common front.

Unlike past forums, the PI is founded on the premise that a social network is not enough. Just as past internationals advanced the demands for a shorter working week and an end to child labor, the PI aims to develop a pragmatic policy vision to transform our institutions.

And unlike past movements, the PI aims to build a lasting infrastructure for internationalism. Rather than relying on temporary campaigns and petitions, the PI strives to be a durable institution that can bind progressive forces together and support them to build power everywhere.

The ambitions of this initiative are undoubtedly high���no higher than the present crisis demands. But the Progressive International is only as powerful as its membership, and to reclaim the world after COVID-19, we will need a powerful movement of progressive forces. So join the Progressive International and work with us to build this common front.

May 8, 2020

Kenya’s prison industrial complex

President Kenyatta, Kenya. Image credit Suzanne Plunkett via Chatham House Flickr CC.

Kenya���s jails were built for 14,000 people and now house close to 50,000 detainees. In 2018, the government established the Kenya Prison Enterprise Corporation to ���unlock��� the ���revenue potential��� of these prisoners, supercharging the local prison-industrial complex. This was written in 2018, but we feel the analysis is as important today as it was then. It also references and relates to other geographies, but is also an important illustration of how this same government that is proposing to hike up the cost of food staples and cooking gas, is exploiting those detained unfairly.

This post is from a new partnership between the Kenyan website The Elephant and Africa Is a Country. We will be publishing a series of posts from their site every week. Posts are curated by Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

In the more than one hundred years between the mid-1850s and 1980s, the State of California constructed a total of nine prisons and two prison camps. But in the five years between 1984 and 1989, nine more prisons were constructed. It had taken more than a century to build the first nine prisons in California, and less than a decade for that number to double. Today, there are 34 state prisons in California, and this is not counting federal prisons or county jails���the equivalent of Kenya���s police cells. The State of California also has 43 prison ���conservation��� camps, whose inmates are procured to fight wildfires and respond to other public emergencies.

That the US is running a prison industrial complex has been well documented. America accounts for just 5% of the world���s population, but 25% of the world���s prisoners. Ava DuVernay���s gripping 2016 documentary, 13th, expertly tracks the policies, systems and forces that have pressed more than 2.3 million Americans���overwhelmingly black and Latino���into the prison system, so much so that in some neighborhoods, going to prison is almost a normal rite of passage.

What the above figures from California reveal is that the processes that produce mass incarceration of an entire demographic can be astonishingly rapid and diabolically efficient.

��� Anonymous submission to #PrisonDiaries (courtesy of @MarigaThoithi)The first thing that happened when we got there is we were told to strip. In the open. All wardens sitting there watching. I think this was the worst thing to happen to us. We were many. The indignity of standing naked in front of strangers

In early October, a press statement from the Presidential Strategic Communications Unit (PSCU) revealed a plan to establish the Kenya Prison Enterprise Corporation, a ���state enterprise��� that would reportedly expand the scope of prison work programs ���with the aim of unlocking the revenue potential of the prisons industry, and ultimately turn it into a reformative and financially self-sustaining entity.���

The new corporation will also contribute to the realization of President [Uhuru] Kenyatta���s Big 4 Agenda, particularly food security, affordable housing, and manufacturing,��� a statement from State House said. The corporation will be mandated to ���organise and manage��� the assets of the Prisons Department, including 86 prison farms with a total of over 18,200 acres of land. The corporation will, at some point, ���foster ease of entry into partnership with the private sector on different spheres������a vague statement that could include private contracting of anything from construction of prison facilities to full operations.

As Michael Onsando at BrainstormKE has argued, the plan to ���unlock the revenue potential��� of the prison industry is linked to the current financial distress in the Jubilee administration, as well as to a desire to make some gains in President Uhuru Kenyatta���s ���legacy��� term.

However, it is horrifying to think that the way to kill two birds���job creation and industrialization���is by the deadly stone of expanding the prison sector, corralling people into a pool of cheap labor with almost no rights. Granted, there are many different privatization models. Private firms can be contracted to build prisons, to manage them, or both. Countries such as the US, UK and Australia have privatized the entire chain of operations from construction to day-to-day operations, while in Europe the trend is to outsource specific functions, such as catering, administration, healthcare and security. In many Asian prisons, the private sector is more directly involved in the prison industry by contracting inmates to work in for-profit factories or firms. Kenya seems to be leaning towards a mixed model, where the corporation, for now, remains fully state-owned but is run with a private sector ethos.

Kenya���s prisons house nearly 50,000 people in facilities designed to hold 14,000. Stories of horrific conditions of disease, vermin and lack of food are common.

Most of the support for the privatization of prisons is in the form of two arguments: one, that the private sector can run prisons better than governments can; and two, that prisons ought to support themselves financially.

The evidence is mixed on the first claim; privatization does not always save money or improve efficiency. A 2011 investigative report by the American Civil Liberties Union revealed that private prisons ���do not save money, cannot be demonstrated to save money in meaningful amounts, or may even cost more than government prisons.���

A value-for-money study commissioned by the Dutch government found that while operational costs in private prisons were reduced by 2-13%, savings disappeared once transaction and other financial costs were taken into account.

Some countries have rejected proposals to privatize prisons. In Costa Rica, although the government had signed a pre-contract to build a private prison with a capacity for 1,200 inmates at US$73 million, it did not proceed with the deal, instead opting to build facilities at its own expense for 2,600 inmates at US$10 million. The Costa Rican government realized that going along with the deal would mean being locked into a contract that would spend US$37 daily per inmate for 20 years, while in the state prisons the amount was US$11. (Inmates in state facilities made up 80% of the prison population.) The government canceled the contract, and opted instead to improve the situation of all inmates, raising the daily per capita amount to US$16 for all those under confinement.

In South Africa, the government took over a private prison in Bloemfontein because G4S���the private security company contracted to run the prison������had lost effective control of the facility.��� Investigations were launched into allegations that some prisoners had been forcibly injected with anti-psychotic medication and subjected to electric shocks.

The second claim���that private prisons should be able to support themselves financially���is deeply rooted in a neoliberal ethos that judges the value of everything through the logic of the market. We see this in the announcement of the plan by PSCU, which stated that unlocking the revenue potential of the prisons industry would ultimately turn it into ���a reformative and financially self-sustaining entity.���

The framing of this proposal is curious, particularly in the way it connects reformation with financial independence. It is neoliberalism offering rehabilitation through success in the market. (No wonder that the phrase ���prominent Nairobi businessman/ woman��� is often used to sanitize the reputation of people mired in scandal.)

Moreover, in a place like Kenya, where government contracts are often irregularly awarded and where corruption is endemic, privatization can actually result in degraded services. Already, detectives are investigating a Sh6.2 billion (US$585 million) scandal at the Prisons Department. A senior detective revealed a few weeks ago that investigators from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations and the anti-graft commission were closing in on suspects behind the suspicious spending on prisoners��� food, which was cleared last year although it is still marked as a pending bill.

Now, by linking the prisons sector with President Kenyatta���s Big 4 Agenda, we are likely to see the emergence of a ���hard-working performer��� at the helm of the prison corporation who will point to the profits at the end of the prison pipeline as evidence of ���cleaning up��� the ailing penal system.

��� Michel FoucaultThe perpetrator is a product of criminal discourse and a victim of institutions that claim to deter crime, but are actually invested in perpetrating a police state where everyone is under surveillance and on the border of falling into criminality.

All this is happening in a worrying context of a criminal justice system that disproportionately targets the young, the poor and the urban. Last year, a damning audit by the National Council on the Administration of Justice revealed that the Kenyan State is essentially at war with informality. In practical terms, poverty is a crime.

Not only that, colonial laws against offenses like vagrancy and loitering remain on our statute books and are vigorously enforced���as Carey Baraka articulated on the perils of being a young man on the streets of Nairobi and being forced to prove your existence by producing an ID card on demand. In fact, demands for ID documents assume that the black body in the city is not legitimate and must be accounted for.

���It���s an assumption that Africans can never be urban,��� says city planner Constant Cap. ���If you are urban, then you are not a real African, and you must explain your presence in the city to the powers that be. Our cities are actually not planned with us in mind���it is like they are not expecting permanent residents, just itinerant workers who trade their labor.���

This means that nearly 70% of court cases in our criminal judicial system are criminally petty, nuisance offenses, or economically-driven (such as being drunk and disorderly, trading without a license, loitering, causing a disturbance, or ���preparing to commit a felony���). The dragnet is so large and indiscriminate that a Kenyan adult has a 1 in 10 chance of spending some time in police custody over the course of a year, although these figures skew heavily towards those who are young, male and poor.

In some ways, it is a logic that leans towards universal punishment rather than supporting universal prosperity���even for the small street trader who is really not doing anyone any harm, and certainly does not deserve jail time. As the economy continues to be depressed, we are likely to see more people who are unable to secure formal employment and who turn to informal trading on the street. This will make them more vulnerable to police harassment and arbitrary arrest.

A recent investigation by Nation Newsplex revealed that there are more pre-trial detainees incarcerated in Kenya than convicted prisoners; 90% of those in remand have been granted bail but cannot afford it even though more than half of the bails were set at less than Sh250,000 (roughly US$2,500). In other words, there are immediate better outcomes for being rich and guilty than poor and innocent.

Meanwhile, the Judiciary is reeling from huge budget cuts this year. It had requested Sh31 billion (US$292 million) to fund its operations for the current financial year but it was allocated Sh17 billion by the National Treasury. The latter figure was further reduced by Parliament to Sh14 billion. This means that judicial officers will likely be under more pressure to arrest and fine, as a prosecutor in the Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP) told me. ���Petty offenses are prosecuted vigorously in the judicial system because they are quick and easy to prove���the only witness needed in most cases is a police officer,��� she said. ���And the fines are now an even important source of money for the Judiciary.���

It doesn���t help that the key performance indicators (KPIs) for judicial officers are convictions. The gravity of the case doesn���t matter because ���a conviction is a conviction, and magistrates get promoted on the basis of the number, not the type, of convictions,��� the prosecutor told me, ���even if the charges are just trespassing, hawking, illegal grazing, and the like.���

How might the profit incentive in the prisons change the trends in convictions and sentencing? ���I definitely see a possibility for it to be more profitable to send people to jail than to fine them,��� the prosecutor said. ���Remandees are often given work to do things like sweep the governor���s compound���a profit motive in prisons will escalate this, and it will be framed as a favor to prisoners.���

But this is not all. The Kenyan education system is undergoing two major changes. On the one hand, the new curriculum has an increased focus on technical and vocational skills, and less of an emphasis on academic subjects. On the other hand, there is increased surveillance and militarization of the school system, with authorities, including the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) and the Education Cabinet Secretary Amina Mohamed, issuing threats of a criminal record and jail time for students who protest or who are implicated in anti-social behavior.

���This is to warn every student from primary school, secondary school, college and university that the DCI is archiving and profiling every criminal act and consolidating charges that may be preferred to each and every student involved in any crime,��� the DCI tweeted in June.

A school-to-prison pipeline is therefore not far-fetched. With the new curriculum putting students on individual ���talent��� pathways, it will be easy to explain student failures on their lack of talent, thereby obscuring the bigger structural issues that might be at play. And now, students cannot complain, or they risk jail time.

���[The] negative characterization of poor and largely nonwhite youth is in sync with the broader push to replace social services with criminalization,��� Alex Vitale writes in ���The Criminalization of Youth,��� an article in Jacobin magazine. ���As more and more deprived neighborhoods are denied access to decent jobs and schools, their young people are criminalized as ���the worst of the worst��� to ensure that the problems in these communities are understood as individual and group moral failures, rather than the result of rapacious market forces and a hollowed-out state.���

��� Steven DonzigerCompanies that service the criminal system need sufficient quantities of raw materials to guarantee long-term growth ��� In the criminal justice field, the raw material is prisoners and industry will do what is necessary to guarantee a steady supply. For the supply of prisoners to grow, criminal justice policies must ensure a sufficient number of incarcerated [people] regardless of whether crime is rising or the incarceration is necessary.

Three new menacing forces���the profit motive of privatized prisons, a depressed economy with fewer formal jobs and more informal trade, and a more militarized school system with jail sentences for unruly students���are likely to work with diabolical synergy to push an increasing number of young people into the criminal justice system.

This should worry us all because mere contact with the system leaves ���a stain of criminality,��� my prosecutor friend told me. ���I���ve seen children and young people enter the criminal justice system for a small reason that could have been handled at home or in the community���and by the time the system is done with them, they are into proper crime: hardened, disillusioned and angry.���

This is not a feature of a broken state apparatus; on the contrary, the state is acting just as it was designed to act, as Keguro Macharia reminds us:

One reads Kenyans demanding colonial systems work better, and weeps.

��� ���we need police to do their work properly���

��� ���we need the laws implemented properly���

��� ���we need the judicial systems to work properly���

If you are being unhumaned, those systems are working properly.

If you are being executed, those systems are working properly.

If you are feeling frustrated and humiliated, those systems are working properly.

The demand cannot be that systems designed to unhuman Africans work properly.

The demand is abolition.

And as for Uhuru Kenyatta achieving the Big 4 agenda through prison ���reform,��� it would be worth looking at how the US government systematically and cynically deprived its black and brown citizens of liberty at a huge cost even to itself. Instead of building good public housing like the Housing Acts of 1949/65/68 mandated, the US rapidly built prisons. So in an evil kind of way, the US did end up investing in public housing���in jail.

‘Queen Sono’ and Netflix���s future in Africa

Production stills from the set of Queen Sono (Chris Duys/Netflix).

Netflix has landed in Africa! Traveling through Johannesburg���s downtown and suburbs, it���s hard to ignore that indeed, Netflix has arrived. Johannesburg���s cityscapes have been painted with posters, billboards and murals promoting the streaming giant���s first script-to-screen production in Africa, Queen Sono. Netflix partnered with Johannesburg-based production company Diprente, and with creator/executive producer Kagiso Lediga (based in South Africa), to produce this series. It���s a Netflix-Diprente coproduction, with Netflix enjoying streaming rights.

Netflix���s presence allows local film and television to reach a global audience and remedy many of the issues that plague many local productions, namely budgetary concerns. Indeed, it���s hard not to be awestruck by both the scale and creativity of Queen Sono���s marketing or the production value of the series allowed by its budget. The stellar cinematography and production design give vibrancy and life to many neighborhoods and landmarks across Johannesburg, gifting the city a cinematic quality it���s long beckoned for. However, behind the spectacle of Queen Sono which both Netflix and the series spend a great deal of time and effort crafting, lingers disturbing prospects for the future of Netflix���s relationship with South African film and television.

American streaming platforms have spent the past few years in a streaming war, pushing and shoving each other in an attempt to prove who’s really about ���great stories��� and who���s more invested in ���content to support a platform.��� (While preparing the launch for Disney+, Disney CEO Bob Iger would go on to differentiate his streaming platform by arguing that ���What Netflix is doing is making content to support a platform ��� We���re making content to tell great stories. It���s very different.���)

It���s a Spiderman-pointing-at-Spiderman meme of various corporations accusing each other of doing the same thing they���re doing. Whoever is to be believed as the true vanguard of cinema, is the platform performing this act best. In that regard, Netflix outshines its competition by an uncontestable margin. It���s an ever-growing entity whose expanse now covers a global scale. The merits of the globalization of film and television bring unprecedented access to foreign content that���s admittedly worth celebrating. While this may be true for content that was made independent of Netflix and subsequently bought and distributed by them, the idea of a ���globalized��� platform presents hidden obstacles for filmmakers outside of Hollywood.

Netflix���s CEO Ted Sarandos didn���t seem particularly concerned about the overwhelmingly negative reception from French critics to Netflix���s first French script-to-screen production, Marseille. Fortune Magazine writer Michal Lev-Ram observed: ���Whether (critics) think Marseille is more merde than merveilleux doesn���t necessarily concern Sarandos (…) What does concern Sarandos is making sure the series ultimately gets more subscribers.��� For international filmmakers making content under a company whose ultimate objective is to get as many subscribers across the globe as possible, the style and format of what they are producing will be determined by these objectives and thus whatever is made will likely be the style of form that���s the least offensive to global sensibilities. Since Hollywood cinematic conventions have been entrenched as hegemonic cinematic conventions, the possibility for international filmmakers to work outside of that mold is almost impossible.

It���s the limited imagination of both the showrunner, Kagiso Lediga, and those imposed by Netflix caused by their mutual desire for global reach that results in Queen Sono, a Hollywood spy drama copy-pasted into Johannesburg with a black female protagonist. Adapting Hollywood conventions into African contexts isn���t necessarily a dead-on-arrival endeavor. One of the many charms of Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambety���s groundbreaking 1973 film Touki Bouki comes from its reconstruction of the Bonnie and Clyde archetype of two young and in love ���rebels without a cause��� on a rebellious quest for a better future, with Mambety using the archetype as a vehicle for a critique of post-colonial Francophilia in 1970s Senegal.

A similar deconstruction of the Hollywood spy drama is, however, absent in Queen Sono, which trades in stylistic and formal reconstruction for copycatting. The Cold War is where the Hollywood spy drama earned its prominence in the West and in Hollywood, with its themes of international intrigue and conspiracy enticing audiences fearing the threat of nuclear war with Soviet Russia. The genre is primarily a fear-mongering device, embellishing conspiracies against the American state from foreign third forces in order to justify America���s increasing militarism. The conditions that necessitate the spy drama in Hollywood are largely non-existent in South Africa, which makes the presence of a conspiratory Russian crime family as the main villain of Queen Sono almost laughable. Far from a thoughtful reconstruction of the spy drama genre in a South African context, most of the series��� shortcomings come from trying to fit a shoe that simply doesn���t fit.

Queen Sono feels all too familiar, chronicling its eponymous protagonist, Queen Sono, a field agent working for Special Operations Group (S.O.G), an intelligence agency that fights covert criminal operations against the state. The first season follows Queen as she fights new threats to Africa, a private security company from Russia aiming to cozy itself with African leaders, and the additional danger of a growing radical paramilitary terrorist group. She fights these external threats all while undergoing a personal journey to uncover the truth behind the assassination of her mother Safiya Sono, a radical freedom fighter portrayed by the series as a hybrid of Winnie Mandela and Chris Hani. If the synopsis makes the series sound muddied and unfocused, it���s because it is. With six episodes, each running at the 40-44 minutes mandatory for prestige American TV dramas, the writers buckle under the weight of each episode���s runtime. Instead of filling the runtime with nuanced and engaging story arcs for its supporting characters, the writers solve the problem by haphazardly giving Queen more things to do. As a result, many scenes feel insignificant and overstay their welcome, convoluted plot developments force the audience to suspend its disbelief a few inches too high and the majority of the supporting characters feel wasted despite a supporting cast doing their best with very little.

Under the confusing plots and awkward pacing lies a theme that can be found through the storylines. Queen Sono tries to ground the impending influence of a Russian syndicate into African states and the conspiracy behind Queen���s mother���s death behind the message that the failures of contemporary South Africa lie with once freedom fighters who���ve taken leadership positions in government, having essentially sold our country and betrayed their comrades for personal gain. Through this, it tries to examine the scars of a wounded country and its people who���ve yet to uncover the depth of their persistent traumas. Queen Sono���s heart is in the right place and in spite of its execution, the attempt is nonetheless worthy of admiration. However, these uniquely African socio-political issues the series wants to tackle require uniquely African modes of storytelling to meaningfully explore.

In the end, Queen Sono could only be so good. In a world where the show was handled by a more competent group of writers and directors, its potential is still capped by a production company more concerned with how the series will attract its growing global audience than whether or not the series does what it���s trying to do effectively. For South African cinema to grow, and for worthwhile sociopolitical questions to be meaningfully unpacked through our cinema, our filmmakers are required to escape from Hollywood tropes and the prioritization of a global audience. A new language is required. While a part of me hopes to be proven wrong, Netflix isn���t the home for a new wave of film and television Africa deserves.

May 7, 2020

The irrelevance of NGOs in Tanzania

President Magufuli of Tanzania at a church in Magomeni. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Nothing has exposed neoliberalism as a hoax as intelligently and most strikingly as COVID-19 has done. (Though at the expense of millions infected and hundreds of thousands dead.) All over the world, people have come to depend almost exclusively on their national governments not only to stay safe against the deadly pandemic but also for economic survival. Against a painful history of relentless assaults on so-called ���big government,��� COVID-19 has grown the size of government bureaucracies and budgets in size to what was hardly imaginable only a few months ago.

This change has brought about another debate about the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Nowhere is this debate about NGOs more palpable than in my home country of Tanzania, where at the time of writing the East African nation had recorded a total of 480 confirmed coronavirus cases, 18 deaths and 167 recoveries. The situation here seems to be getting out of control as more fatalities continue to be reported, exacerbated by the increasing tendency of hospitals, especially in the country���s commercial capital of Dar es Salaam, to reject patients suspected of having the coronavirus disease. Several people (see here and here) have reported having their relatives turned away by hospitals, after which some died. The government has been trying hard to underestimate the magnitude of the pandemic, including by underreporting the number of fatalities and doing night burials.

Nearly every action taken by national governments throughout the world in their efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19, and thus to save lives and communities, goes directly against the dictates of neoliberal fundamentalism. For a number of decades, advocates of this ideology would propose murderous cuts in public spending on critical sectors like health and education. In addition to the breakneck privatization of public services was the massive growth of NGOs whose missions varied widely; from those advocating for government accountability and democratic institutions to those championing girls��� rights, citizens��� agency, and countless others providing services.

This is no coincidence. The missionaries of neoliberal evangelism have been pushing for the social services provision role of governments to be replaced by NGOs and private individuals, arguing that this will ultimately improve service efficiency for governments. Perhaps there���s no stauncher proponent of that argument in Tanzania than former President Benjamin Mkapa���or at least until recently. It was under Mkapa���s administration that both privatization and NGO growth in the country took root. ���Soon after assuming office, in November 1995,��� said Mr Mkapa in his speech at the official launch of Tanzania National Business Council (TNBC) on April 9, 2001, quoted in “A Capitalizing City” by Dr. Chambi Chachage, ���I realised the need to change the way the national economy is managed. This need was made more acute by the fact that our country was moving from a public sector led economy to a private sector driven market economy.��� (Later, Mr. Mkapa would describe the privatization drive unleashed by his administration as the ���worst mistake��� of his presidency in his memoirs My Life, My Purpose.) In the ongoing battle against COVID-19, however, both NGOs and the private sector have been conspicuously absent on the frontlines where the war against the virus is being waged.

The role of NGOs in Tanzania has been made more interesting both by the Tanzanian government���s handling of the pandemic (which I discuss here), and NGOs��� responses (or lack thereof). So far, the responses of NGOs to the pandemic have been simply bewildering, opaque, and ambiguous. Part of this ambiguity, I think, is due to both the history of NGOs in Tanzania and the issues that they continue to remain deadly silent about. In this latter category is what seems to be an almost unanimous agreement among the NGOs, with very few exceptions, of forgoing what they claim to be their main mission, that is: to cultivate a culture of accountable governance as well as the building of strong democratic institutions in the country. This abandonment is disappointing and surprising at the same time, because during a crisis like the one we are in now, one would have expected that the NGOs, far from pretending as if they no longer exist, would double, or even triple, their efforts to force those in power to act more responsibly and deliver to their constituents.

But from the way things appear on the ground, it is as if the coronavirus disease has forced the NGOs to take some time off their work and give the government, whose handling of the pandemic has made Tanzania the laughing stock of the world, a free reign to act as it wishes. One area of concern is the way the government has entirely left people to fend for themselves amidst the crisis. In fact, instead of helping its people, the government���s asking the people to donate to it! The fact that no NGOs have so far called the government out means that the people have not just been abandoned by their government, but also by the organizations that claim to work on their behalf.

The NGOs have failed to condemn President John Magufuli���s statements and actions that threaten to put the lives of thousands at risk. These statements include the recent one he made during a televised address from his hometown of Chato, in the Geita region of northwestern Tanzania where the president has been ���self-isolating��� since the pandemic started. There he urged Tanzanians to consider inhaling steam from a boiling pot of water as a means to cure coronavirus, a suggestion medical doctors have nevertheless advised against. During the rare address, President Magufuli also dismissed the exercise to disinfect public spaces as ���nonsense.��� Earlier, President Magufuli took to Twitter to declare three days of national prayers ���to help defeat coronavirus,��� and his government even organized a national prayer to save Tanzania from the pandemic. All this had Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, concerned, according to journalist Geoffrey York who reported via Twitter. In another address, where Mr. Magufuli accused Tanzania���s lab technicians of conspiring with ���imperialists��� to sabotage the country by increasing the number of positive cases, something which led to the sacking of the national community health laboratory director Dr. Nyambura Moremi, the President said that his government would dispatch a plane to fetch the herbal treatment for the coronavirus touted by the president of Madagascar despite a warning from the WHO that a herbal tonic cannot cure the disease. (One observer of Tanzanian politics described the address as ���totally reckless��� and even called on people to boycott Magufuli���s subsequent addresses on the coronavirus pandemic lest they go bonkers.) Dangerous and irresponsible as these statements and measures seem, not a single NGO that works in the area of public health���and there is no shortage of them���uttered any public criticism of Magufuli.

Nor are the democratic-championing NGOs concerned by the government���s resolve to centralize the flow of information on coronavirus. No NGO, for example, has come out against the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority���s (TCRA) directive to members of WhatsApp groups to screenshot ���fake information��� posted in these groups and report it to authorities. No NGO seems bothered by the Tanzania Police Force���s irresponsible act to storm and interrupt a press conference by the main opposition party CHADEMA intended to give Tanzanians an alternative appraisal of the coronavirus situation from that given by the government. (The party was subsequently able to organize a press conference where its national chairperson Freeman Mbowe outlined twelve issues that he thought were fundamental in the fight against the pandemic.) The same silence on the part of the NGOs was noticeable after a cabinet minister suggested that people should consider using honey when responding to a spike in the price of sugar. (Following a backlash, however, the government later announced a cap on sugar prices.)

While everybody was busy examining their role in combating the coronavirus in the country, some of Tanzania���s ���top-notch��� NGOs were spotted presenting the government with a 79 million Tanzanian shillings check (about US$34,000) to help fight the virus. The NGOs did that while little or nothing at all was known in the general public of the government���s strategy or even how the money will be used.

I find the move disturbingly ironic, however, given the fact that this money was originally supposed to come directly from the donors to the government coffers but the ���development partners��� gave them to the NGOs because, as shown above, they are thought to be best placed to deal with social problems. It is also mind-boggling to find the NGOs donating to the government amidst a funding crisis that has hit NGOs across the continent. If the NGOs themselves are convinced that the Tanzanian government can deal with the COVID-19 crisis far better than they can to the extent of giving it money, what does it say of their ideological justification to exist? To their credit, since then a coalition of Tanzania���s NGOs released a position paper and ���strategic areas��� on COVID-19. In the paper, the NGOs confess to have been caught ���unprepared��� by the pandemic, something that hampered their ability to respond ���promptly.���

A close friend of mine, who works in Tanzania���s NGO sector, thought it was a bad idea for me to go ahead with this piece, saying it was unfair to criticize the NGOs given the fact that I understand the political environment within which the organizations operate and the repression unleashed on them by the state. For a moment I thought this friend of mine was right because it’s true that they work in a tough environment. But then I thought: wasn���t this very attitude on the part of the NGOs to allow themselves to be pushed around by the government responsible for their own miseries, and ultimately, their failure to do what they were founded on?

This led me to revisit 2007, when acclaimed legal and development scholar Professor Issa Shivji published a book, Silences in the NGO Discourse, which served as advice on how Tanzania���s NGOs can remain accountable. He wrote then that if the NGOs are to live up to their missions, which include ensuring democratic reforms in the country, then their entire strategy of engagement with the state would have to change radically. For example, in place of stakeholder conferences, there should be protracted public debates, wrote Shivji. Where previously the NGOs used to dialogue with the state ���in five-star hotels,��� now there should be demonstrations, protest marches and teach-ins in streets and community centers to expose serious abuses of power and bad policies. ���Democratic governance would be an arena where power is contested, not some moral dialogue or crusade for good against evil, as the meaningless term ���good governance��� implies ��� You cannot dialogue with power,��� the renowned author writes poignantly.

In the wake of the ongoing debate on the role and relevance of NGOs amidst a global pandemic, and the government���s ambiguous response, it appears that more than ten years since Shivji���s book, the country���s NGOs have not been able���or willing���to learn a lesson. Nor, telling from the way they behave amidst the current crisis, is there any indication that they will do so in the near future.

The irrelevance of NGOs

President Magufuli of Tanzania at a church in Magomeni. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Nothing has exposed neoliberalism as a hoax as intelligently and most strikingly as COVID-19 has done. (Though at the expense of millions infected and hundreds of thousands dead.) All over the world, people have come to depend almost exclusively on their national governments not only to stay safe against the deadly pandemic but also for economic survival. Against a painful history of relentless assaults on so-called ���big government,��� COVID-19 has grown the size of government bureaucracies and budgets in size to what was hardly imaginable only a few months ago.

This change has brought about another debate about the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Nowhere is this debate about NGOs more palpable than in my home country of Tanzania, where at the time of writing the East African nation had recorded a total of 480 confirmed coronavirus cases, 18 deaths and 167 recoveries. The situation here seems to be getting out of control as more fatalities continue to be reported, exacerbated by the increasing tendency of hospitals, especially in the country���s commercial capital of Dar es Salaam, to reject patients suspected of having the coronavirus disease. Several people (see here and here) have reported having their relatives turned away by hospitals, after which some died. The government has been trying hard to underestimate the magnitude of the pandemic, including by underreporting the number of fatalities and doing night burials.

Nearly every action taken by national governments throughout the world in their efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19, and thus to save lives and communities, goes directly against the dictates of neoliberal fundamentalism. For a number of decades, advocates of this ideology would propose murderous cuts in public spending on critical sectors like health and education. In addition to the breakneck privatization of public services was the massive growth of NGOs whose missions varied widely; from those advocating for government accountability and democratic institutions to those championing girls��� rights, citizens��� agency, and countless others providing services.

This is no coincidence. The missionaries of neoliberal evangelism have been pushing for the social services provision role of governments to be replaced by NGOs and private individuals, arguing that this will ultimately improve service efficiency for governments. Perhaps there���s no stauncher proponent of that argument in Tanzania than former President Benjamin Mkapa���or at least until recently. It was under Mkapa���s administration that both privatization and NGO growth in the country took root. ���Soon after assuming office, in November 1995,��� said Mr Mkapa in his speech at the official launch of Tanzania National Business Council (TNBC) on April 9, 2001, quoted in “A Capitalizing City” by Dr. Chambi Chachage, ���I realised the need to change the way the national economy is managed. This need was made more acute by the fact that our country was moving from a public sector led economy to a private sector driven market economy.��� (Later, Mr. Mkapa would describe the privatization drive unleashed by his administration as the ���worst mistake��� of his presidency in his memoirs My Life, My Purpose.) In the ongoing battle against COVID-19, however, both NGOs and the private sector have been conspicuously absent on the frontlines where the war against the virus is being waged.

The role of NGOs in Tanzania has been made more interesting both by the Tanzanian government���s handling of the pandemic (which I discuss here), and NGOs��� responses (or lack thereof). So far, the responses of NGOs to the pandemic have been simply bewildering, opaque, and ambiguous. Part of this ambiguity, I think, is due to both the history of NGOs in Tanzania and the issues that they continue to remain deadly silent about. In this latter category is what seems to be an almost unanimous agreement among the NGOs, with very few exceptions, of forgoing what they claim to be their main mission, that is: to cultivate a culture of accountable governance as well as the building of strong democratic institutions in the country. This abandonment is disappointing and surprising at the same time, because during a crisis like the one we are in now, one would have expected that the NGOs, far from pretending as if they no longer exist, would double, or even triple, their efforts to force those in power to act more responsibly and deliver to their constituents.

But from the way things appear on the ground, it is as if the coronavirus disease has forced the NGOs to take some time off their work and give the government, whose handling of the pandemic has made Tanzania the laughing stock of the world, a free reign to act as it wishes. One area of concern is the way the government has entirely left people to fend for themselves amidst the crisis. In fact, instead of helping its people, the government���s asking the people to donate to it! The fact that no NGOs have so far called the government out means that the people have not just been abandoned by their government, but also by the organizations that claim to work on their behalf.

The NGOs have failed to condemn President John Magufuli���s statements and actions that threaten to put the lives of thousands at risk. These statements include the recent one he made during a televised address from his hometown of Chato, in the Geita region of northwestern Tanzania where the president has been ���self-isolating��� since the pandemic started. There he urged Tanzanians to consider inhaling steam from a boiling pot of water as a means to cure coronavirus, a suggestion medical doctors have nevertheless advised against. During the rare address, President Magufuli also dismissed the exercise to disinfect public spaces as ���nonsense.��� Earlier, President Magufuli took to Twitter to declare three days of national prayers ���to help defeat coronavirus,��� and his government even organized a national prayer to save Tanzania from the pandemic. All this had Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, concerned, according to journalist Geoffrey York who reported via Twitter. In another address, where Mr. Magufuli accused Tanzania���s lab technicians of conspiring with ���imperialists��� to sabotage the country by increasing the number of positive cases, something which led to the sacking of the national community health laboratory director Dr. Nyambura Moremi, the President said that his government would dispatch a plane to fetch the herbal treatment for the coronavirus touted by the president of Madagascar despite a warning from the WHO that a herbal tonic cannot cure the disease. (One observer of Tanzanian politics described the address as ���totally reckless��� and even called on people to boycott Magufuli���s subsequent addresses on the coronavirus pandemic lest they go bonkers.) Dangerous and irresponsible as these statements and measures seem, not a single NGO that works in the area of public health���and there is no shortage of them���uttered any public criticism of Magufuli.

Nor are the democratic-championing NGOs concerned by the government���s resolve to centralize the flow of information on coronavirus. No NGO, for example, has come out against the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority���s (TCRA) directive to members of WhatsApp groups to screenshot ���fake information��� posted in these groups and report it to authorities. No NGO seems bothered by the Tanzania Police Force���s irresponsible act to storm and interrupt a press conference by the main opposition party CHADEMA intended to give Tanzanians an alternative appraisal of the coronavirus situation from that given by the government. (The party was subsequently able to organize a press conference where its national chairperson Freeman Mbowe outlined twelve issues that he thought were fundamental in the fight against the pandemic.) The same silence on the part of the NGOs was noticeable after a cabinet minister suggested that people should consider using honey when responding to a spike in the price of sugar. (Following a backlash, however, the government later announced a cap on sugar prices.)

While everybody was busy examining their role in combating the coronavirus in the country, some of Tanzania���s ���top-notch��� NGOs were spotted presenting the government with a 79 million Tanzanian shillings (about US $34 million) check to help it fight the virus. The NGOs did that while little or nothing at all was known in the general public of the government���s strategy or even how the money will be used.

I find the move disturbingly ironic, however, given the fact that this money was originally supposed to come directly from the donors to the government coffers but the ���development partners��� gave them to the NGOs because, as shown above, they are thought to be best placed to deal with social problems. It is also mind-boggling to find the NGOs donating to the government amidst a funding crisis that has hit NGOs across the continent. If the NGOs themselves are convinced that the Tanzanian government can deal with the COVID-19 crisis far better than they can to the extent of giving it money, what does it say of their ideological justification to exist? To their credit, since then a coalition of Tanzania���s NGOs released a position paper and ���strategic areas��� on COVID-19. In the paper, the NGOs confess to have been caught ���unprepared��� by the pandemic, something that hampered their ability to respond ���promptly.���

A close friend of mine, who works in Tanzania���s NGO sector, thought it was a bad idea for me to go ahead with this piece, saying it was unfair to criticize the NGOs given the fact that I understand the political environment within which the organizations operate and the repression unleashed on them by the state. For a moment I thought this friend of mine was right because it’s true that they work in a tough environment. But then I thought: wasn���t this very attitude on the part of the NGOs to allow themselves to be pushed around by the government responsible for their own miseries, and ultimately, their failure to do what they were founded on?

This led me to revisit 2007, when acclaimed legal and development scholar Professor Issa Shivji published a book, Silences in the NGO Discourse, which served as advice on how Tanzania���s NGOs can remain accountable. He wrote then that if the NGOs are to live up to their missions, which include ensuring democratic reforms in the country, then their entire strategy of engagement with the state would have to change radically. For example, in place of stakeholder conferences, there should be protracted public debates, wrote Shivji. Where previously the NGOs used to dialogue with the state ���in five-star hotels,��� now there should be demonstrations, protest marches and teach-ins in streets and community centers to expose serious abuses of power and bad policies. ���Democratic governance would be an arena where power is contested, not some moral dialogue or crusade for good against evil, as the meaningless term ���good governance��� implies ��� You cannot dialogue with power,��� the renowned author writes poignantly.

In the wake of the ongoing debate on the role and relevance of NGOs amidst a global pandemic, and the government���s ambiguous response, it appears that more than ten years since Shivji���s book, the country���s NGOs have not been able���or willing���to learn a lesson. Nor, telling from the way they behave amidst the current crisis, is there any indication that they will do so in the near future.

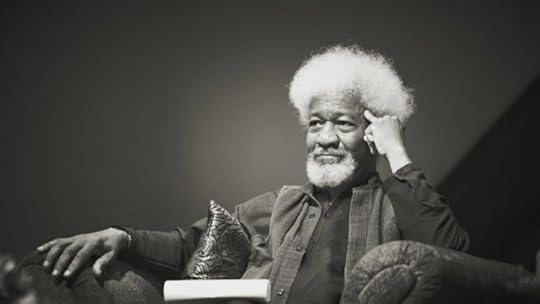

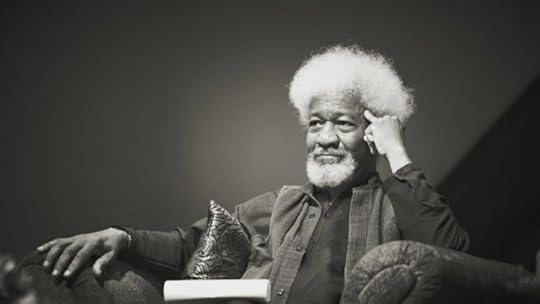

Wole Soyinka’s little known musical endeavors

Screengrab via Youtube.

In response to a query that sought his thoughts on Bob Dylan���s controversial Nobel Prize win in 2017, Wole Soyinka quipped: ���Since I���ve written quite a number of songs for my plays, I would like to be nominated for a Grammy.���

Soyinka is popularly known for a number of remarkable things: he is the first African Nobel laureate; he carries an iconic white fro; he is the protestor who once held up a Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation studio at gunpoint; and more recently, he is that old professor who was asked by a young man to vacate an airplane seat. But in addition to being a Nobel-winning-author, Wole Soyinka, much like his late cousin Fela Kuti, made political music.

For a time in his mid-20s, Soyinka was a cafe singer in Paris. Two decades later, back in Nigeria, he wrote a two-track album named Unlimited Liability Company. Although much of the singing was done by actor and musician Tunji Oyelana & His Benders, Wole Soyinka���s voice also features on both tracks. This musical endeavor was an extension of his artistic activism from the page and stage to wax. His knack for sarcasm���as embodied in the poem ���Telephone Conversation,��� or in a play like Madmen & Specialists���is restated on Unlimited Liability Company. The LP, released in 1983 by Soyinka���s production company, Ewuro Productions, was a satire of the Nigerian political elite, headed at the time by Shehu Shagari. Just as much, it was a critique of the military regimes that preceded and succeeded Shagari.

Side A of Unlimited Liability Company features the LP���s title track (which is more commonly known as ���Chairman���). The main singer addresses a gallivanting chairman whose directors and managers are mismanaging things back at home; ���each time they sneeze, millions of Naira go scatter.��� (It is hard to not think of how similar this gallivanting chairman is to Nigeria���s current president, who barely ever does any sitting at home).

On side B is ���Etike Revo Wetin,��� more popularly known by the tongue-in-cheek phrase that makes the song���s chorus: ���I love my country.��� The singer here narrates the nation���s peculiarities to the listener. For example: ���in this my nation, all is free // to starve to death, you don���t need a fee.��� The record turned out to be commercially successful in Nigeria, in the 1980s. (DJ Cuppy remixed this song for her debut single, ���I Love My Country���).

Altogether, the LP runs just under half an hour of indirect condemnation of a political elite and its corruption, oppression, and bottom-line disregard for the lives and well-being of citizens.

Two Nigerian writers, Helon Kabila and Teju Cole, have stated that Soyinka is perhaps better known to the ordinary Nigerian for his political activism than for his play writing. They are arguably right. On YouTube, a certain B. Ibhas, commenting on a clip from ���I Love My Country,��� wrote: ������ this [���] musical side of Wole Soyinka is little known.��� Ibhas is certainly right, which is why it should be better known that in Wole Soyinka���s oeuvre of sociopolitical critique, there is a long-playing record called Unlimited Liability Company.

Wole Soyinka sang

Screengrab via Youtube.

In response to a query that sought his thoughts on Bob Dylan���s controversial Nobel Prize win in 2017, Wole Soyinka merely quipped: ���Since I���ve written quite a number of songs for my plays, I would like to be nominated for a Grammy.���

Soyinka is popularly known for a number of remarkable things: he is the first African Nobel laureate; he carries an iconic white fro; he is the protestor who once held up a Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation studio at gunpoint; and more recently, he is that old professor who was asked by a young man to vacate an airplane seat. But in addition to being a Nobel-winning-author, Wole Soyinka, much like his late cousin Fela Kuti, made political music.

For a time in his mid-20s, Soyinka was a cafe singer in Paris. Two decades later, back in Nigeria, he wrote a two-track album named Unlimited Liability Company. Although much of the singing was done by actor and musician Tunji Oyelana & His Benders, Wole Soyinka���s voice also features on both tracks. This musical endeavor was an extension of his artistic activism from the page and stage to wax. His knack for sarcasm���as embodied in the poem ���Telephone Conversation,��� or in a play like Madmen & Specialists���is restated on Unlimited Liability Company. The LP, released in 1983 by Soyinka���s production company, Ewuro Productions, was a satire of the Nigerian political elite, headed at the time by Shehu Shagari. Just as much, it was a critique of the military regimes that preceded and succeeded Shagari.

Side A of Unlimited Liability Company features the LP���s title track (which is more commonly known as ���Chairman���). The main singer addresses a gallivanting chairman whose directors and managers are mismanaging things back at home; ���each time they sneeze, millions of Naira go scatter.��� (It is hard to not think of how similar this gallivanting chairman is to Nigeria���s current president, who barely ever does any sitting at home).

On side B is ���Etike Revo Wetin,��� more popularly known by the tongue-in-cheek phrase that makes the song���s chorus: ���I love my country.��� The singer here narrates the nation���s peculiarities to the listener. For example: ���in this my nation, all is free // to starve to death, you don���t need a fee.��� The record turned out to be commercially successful in Nigeria, in the 1980s. (DJ Cuppy remixed this song for her debut single, ���I Love My Country���).

Altogether, the LP runs just under half an hour of indirect condemnation of a political elite and its corruption, oppression, and bottom-line disregard for the lives and well-being of citizens.

Two Nigerian writers, Helon Kabila and Teju Cole, have stated that Soyinka is perhaps better known to the ordinary Nigerian for his political activism than for his play writing. They are arguably right. On YouTube, a certain B. Ibhas, commenting on a clip from ���I Love My Country,��� wrote: ������ this [���] musical side of Wole Soyinka is little known.��� Ibhas is certainly right, which is why it should be better known that in Wole Soyinka���s oeuvre of sociopolitical critique, there is a long-playing record called Unlimited Liability Company.

May 6, 2020

Paying the ultimate price

Teaching scouts about HIV/AIDS in Central African Republic. Image credit Pierre Holtz for UNICEF CC.

The video of Dr. Anthony Fauci, US President Donald Trump���s health advisor, snickering and covering his face in response to Trump���s remarks at a press conference addressing the COVID-19 pandemic has been a source of catharsis for many of the millions of Americans currently sheltering in their homes. It illustrates a juxtaposition: the posturing executive spills out a fluid mix of misinformation, bravado, and cagey defensiveness, to be followed by the calm medical professional who articulates critical guidance, warnings, and corrections.

Dr. Fauci, who has directed the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984, developed and honed these communications skills during the US response to the HIV epidemic. And the interplay between President Trump and Dr. Fauci, as well as the wide variety of public and national responses to the coronavirus, reveals that the majority of Americans, including politicians, failed to internalize the key lessons they should have learned in the AIDS response.

The HIV epidemic originated in Central Africa in the early 1900s when the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV), a disease native to chimpanzees, transferred over to a human, likely a hunter, and became Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). It circulated slowly in its local area over several decades before reaching urban centers in the 1960s and early 1970s, at which point it began spreading across the continent via intercity travel routes. After this second stage of proliferation, HIV began to spread off the continent. The first cases of AIDS in North America began appearing in the late 1970s. The virus was first identified and named in 1981 by American clinicians from the CDC studying an outbreak among gay men living in San Francisco. Simultaneously, doctors in Central and Southern Africa began to notice a massive and unusual outbreak of deaths by illnesses that usually afflict individuals with highly compromised immune systems. Epidemiologists quickly connected these two dots, and by the late 1980s, the global public health community had organized an unprecedented disease response.

The parallels between HIV and coronavirus are legion. A highly infectious virus with a lengthy and asymptomatic incubation period spreads silently and quickly in its geographical region of origin. By the time medical and public health professionals understand it to be a problem of significance, it has already made its way to other regions. Pre-existing social and political structures and divisions set the mold for both the spread of the disease and the response. The disease proliferates rapidly among traditionally vulnerable populations least capable of taking precautionary steps to protect themselves. Knowledge of the epidemic���s region of origin, as well as entrenched attitudes toward the vulnerable classes affected, allow national governments to create scapegoats, which are used either to ignore or downplay the crisis or to promulgate nationalist sentiment.

We see these patterns emerging in response to the coronavirus, just as they did during the HIV epidemic decades before. The virus���s origin and rapid spread in the Wuhan region of China has led Trump and many of his followers to dub COVID-19 the ���Chinese Virus.��� Such xenophobic naming echoes the common characterization of HIV as an ���African��� disease, implying some biological or cultural predisposition to the viral pathogen. Conspiracy theories proliferate. In China, some citizens wonder why this virus seemed to target them in particular. For explanation, many dip into existing political wells. The Chinese government has blamed American service members who visited the Wuhan region in October 2019, playing on geopolitical tensions with the United States. Similarly, many Africans still suspect that HIV was deliberately introduced by westerners seeking to debilitate the continent after the end of formal colonialism.

Yet, in truth, the explanation is far simpler and far less satisfying: the coronavirus affected China���s population most severely in its early days because it is a virus that crossed over into humans in China, just as HIV infected more Africans than any other group for no other reason than it began in Africa. Both diseases possess lengthy asymptomatic incubation periods (though they differ by several orders of magnitude) during which they are highly contagious, and thus both spread with great speed in the places they originated before health or government officials noticed their presence. It is precisely this trait that made both difficult to contain.

Viral crises unearth and widen already extant social divisions. Around the world, nations and publics continue to recycle and repackage familiar scapegoats to explain coronavirus and its spread. In Italy, far-right politicians invoke the familiar bogeyman of migrancy, despite a total lack of supporting evidence. In the US, the state closed borders and issued travel bans long after the virus had taken root. But the true problem lies in the fact that many of these latent social problems (migration, poverty, racism) are built into the very structure of societies, and facilitate the spread of disease. These structures usually render vulnerable those already most likely to be targeted by scapegoating.

Take, for example, the first urban area ever hit by HIV, the city of Kinshasa (then L��opoldville), the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. As Jacques Pepin has shown, Belgian colonial authorities imported men into the city during the colonial era in order to exploit their labor and extract profit for Belgium. They made it enormously difficult for women to migrate into the city to join their husbands. As a result, an illicit market for prostitution emerged. Once HIV reached the city, the dense sexual networks structured by colonial law spread the virus like wildfire among the African population of the city.

Homophobia in the US performed similar work. The illegality of sodomy in multiple states coupled with government-sanctioned discrimination against queer individuals and the growing ties between evangelicalism and the ruling Republican Party in the 1970s and 1980s led many to disconnect from their families and local networks and move to urban areas. Places like New York City and San Francisco played host to burgeoning queer communities, which performed critical social, cultural, and political work, and exploded into the queer rights movement. However, the sexual networks created as part of this reaction to structural oppression placed the gay communities in these cities at the epicenter of the American HIV epidemic.

What HIV teaches us is that social discrimination and the vectors by which disease spreads are inextricable. While slogans like ���coronavirus doesn���t discriminate��� serve an important awareness-raising function, coronavirus discriminates inasmuch as the society it operates within does. As a result, the largely black and brown corps of hourly service workers who, according to the Economic Policy Institute, are far more likely to be paid poverty-level wages than their white counterparts and therefore cannot afford to take time off, are disproportionately likely to come into contact with the virus. Additionally, that same class of individual is least likely to be able to afford the costs for treatment in the US for-profit healthcare system if and when they fall ill. And all the while, the risk of mass infection grows daily in the detention camps along the southern border that house the migrants Trump blames for the crisis.

As scapegoating proliferates, governments utilize these widening social divisions in one of two ways. First, some use discrimination as a tool for excusing and extending inaction, as was the case of the US in the 1980s and in South Africa in the early 2000s. Ronald Reagan���s administration famously refused to acknowledge AIDS until the late 1980s, resulting in, by some estimates, the deaths of more than 80,000 Americans. When questioned by reporter Lester Kinsolving about Reagan���s lack of response, then deputy press secretary Larry Speakes deflected by implying that Kinsolving���s ongoing interest in the disease must mean that he was homosexual. It would be another five years before the administration took any official action in response to the epidemic, under internal pressure from experts such as the young Dr. Fauci and, more importantly, external pressure from activist organizations like ACT UP. In South Africa, Thabo Mbeki engaged in official AIDS denialism starting in 2000, publicly questioning whether or not it was a coincidence that HIV had emerged immediately after the end of white rule in South Africa. By raising the specter of apartheid, Mbeki invoked the most fraught line of fragmentation in South African society, and thereby stalled government action until public campaigns from grassroots organizations like the Treatment Action Campaign forced his hand in 2003.

Second, some states employ the ���othering��� of scapegoating to turn the federal response to the virus into a nationalist propaganda tool. As scholars Ashley Currier and Robert Lorway have pointed out, during the explosion of HIV in Namibia several government officials posited that homosexuals were ���responsible for spreading the epidemic,��� theorizing that Americans had created the disease and introduced it to the homosexual population. Coupled with public assertions that ���governors should see to it that there are no criminals, gays and lesbians in [their] villages and regions,��� and exhortations to police to ���eliminate��� gay and lesbian Namibians, officials made it clear that the national response to HIV required that citizens come together to denounce and even forcibly expatriate non-heterosexual individuals. By framing homosexuality as ���pervert[ed]��� and ���European,��� and accusing Namibians who engage in same-sex practices of ���appropriating foreign ideas in our society [and] destroying the local culture,��� the Namibian government used the HIV epidemic to deny citizenship to an entire class of person and to rally Namibians around a heteronormative form of nationalism.

In his response to COVID-19, President Trump has employed both tactics. On January 22, in one of his first public statements on the burgeoning pandemic, he said ���We have it totally under control. It���s one person coming in from China. And we have it under control.��� Shortly afterward, his administration blocked travel from China alone, despite the fact that 100 cases had been reported in 21 countries, including the US. A month later, he referred to the virus as a ���hoax��� concocted by Democrats to damage his electability, tapping into yet another social division in the US in order to avoid action. In fact, during this time period the administration did virtually nothing to prepare for the imminent crisis, save to redirect blame to familiar targets, much as Larry Speakes had done in the 1980s.

Once the need for immediate action became unavoidably apparent in March, Trump pursued the second tactic. By scapegoating his usual targets, he attempted to consolidate his electoral base and promote his distinctive brand of American nationalism. He repeatedly criticized the way the media has reported the virus and the previous administration���s response to the swine flu in order to deflect criticisms of his own administration, and even blamed former president Barack Obama and former vice president Joe Biden for failures in the current crisis. He began insistently referring to COVID-19 as the ���Chinese Virus,��� going so far as to cross out ���Corona��� on his own speech transcript and replace it with ���Chinese.��� Additionally, he started blaming the Chinese government for the pandemic���s spread. And while publicly scapegoating his enemies, he promoted his own nationalist brand by wearing campaign hats to press conferences, adding campaign slogans to public statements about the virus, and advocating for his preferred xenophobic policies as solutions to the crisis. These three tweets from March illustrate this tactic: On March 10, he shared a Charlie Kirk tweet that reads, ���Now, more than ever, we need the wall. With China Virus spreading across the globe, the US stands a chance if we can control our borders,��� and added the note ���Going up fast. We need the Wall more than ever!���; on March 18, he tweeted ���I always treated the Chinese Virus very seriously, and have done a very good job from the beginning, including my early decision to close the ���borders��� from China���against the wishes of almost all. Many lives were saved. The Fake News new narrative is disgraceful & false!���; and, on March 27, he tweeted ���I love Michigan, one of the reasons we are doing such a GREAT job for them during this horrible Pandemic. Yet your Governor, Gretchen ���Half��� Whitmer is way in over her head, she doesn���t have a clue. Likes blaming everyone for her own ineptitude! #MAGA.���

In between these tweets, Trump declared that immigrants would be barred from crossing into the US from Mexico, where he had already forced asylum seekers to wait in crudely erected, crowded, unofficial refugee camps for months on end. By the time of that statement, the number of diagnosed cases in the US had surpassed 8,000, including multiple infections in every state along the US border. On March 24, Trump stated that the federal government would be willing to hold back aid and supplies from states with Democratic governors unless they stopped criticizing him. And on April 1, The New York Times reported that the Trump administration had sped up construction of the wall along the Mexican border, contending, against the advice of the CDC, that it would slow the spread of COVID-19, days after the US received the dubious distinction of hosting the most diagnosed cases of any nation in world. Despite Dr. Fauci���s warnings, the familiar scapegoats set the mold for the virus response once again.

All of this is not to say that there are no differences between the two viruses. They are genetically dissimilar, operate on vastly different timescales, and spread in distinct ways. The hope for defeating HIV lies in ending its transmission, a future made possible by recent scientific breakthroughs that taking anti-retroviral medication correctly prevents transmission, while the end of COVID-19 hinges on the creation and dissemination of a successful vaccine. However, the most significant distinction between the two may prove to be that coronavirus has reached pandemic status, while HIV remains an epidemic confined predominantly to certain regions, like Southern Africa and Eastern Europe, and, depending on the location, certain vulnerable classes, such as black and queer individuals in the US. And if governments do not begin to take the lessons of the AIDS crisis seriously, lessons learned at the cruel expense of 32 million lives lost, untold millions more will be made to pay the ultimate price.

Reclaiming digital platforms for African feminists

Tiffany Mugo and Siphumeze Khundayi. Image credit TED.

This post is part of our series ���Talking back: African feminisms in dialogue.��� It is dedicated to guest editor Rama Salla Dieng���s late sister, Nd��ye Anta Dieng (1985-2019).

Tiffany Kagure Mugo is co-founder and curator of HOLAA: a Hub of Loving Action in Africa, a pan-Africanist hub that tackles issues surrounding African sexuality. In the following interview she talks about the founding of the platform and the philosophy behind it.

Rama Salla Dieng

How did you meet [co-founders] Christel Antonites and Siphumeze Khundayi, and what led you three to create HOLAA?

Tiffany Mugo

It was the year 200 BC and the War of the Worlds was finally over ��� winter seemed so long that year. Kidding! We met in university. The other two were in a project called ���Women Crossing the Line��� and were doing the Lorde���s work as it were, leading conversations within the University of Cape Town around bodily autonomy and doing sex-positive work before it was cute. I was messing around with Siphumeze and that���s how I got to meet Christel, and how we all took to drinking wine together. That is how HOLAA was born. Like any great idea HOLAA came about from the wine-filled musing of three friends who, due to Dutch courage were sure they could change the world, or at least the blogosphere. We wanted to have a space on the internet that looked like us (African lesbians at the time, we weren���t woke to the diversity of sexuality then) and so decided to do what any university student with access to the internet would do. Start a blog. And once that was up and running, no blog is worth its salt without supporting social media platforms and fast forward a few years and a series of fortunate events later and now we are here being HOLAA. Whatever HOLAA is right now. We would like to lie and say that we did want to save the world, but really we did this for us. Because sexuality was a tricky and lonely space, in terms of visibility, and we would see ourselves in the mirror, even if we had to hold up that mirror ourselves. However, even when we realized we were grown now, and could wander out into the cruel world without HOLAA holding our hands. She had outgrown us by this time, and we realized the need for something like this in the wider world, so we kept going.

Rama Salla Dieng

I like how you refer to HOLAA as ���she.��� You are a writer what do you think is the power of non-fiction? And how have your location, gender, and sexuality influenced your artistic choices?

Tiffany Mugo

HOLAA is our baby. And just like a real child she takes time, energy, money, and keeps us up at night. Non-fiction is a way of using the stories of those around you to have a conversation, one rooted in reality, in something tangible. When someone writes about their story or that of others without coating it in a veil of fantasy, there is a way it hits harder in my opinion. Non-fiction is a tool that is available to everyone because everyone has a reality that they can draw from.