Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 182

April 18, 2020

Reading List: Ronnie Close

Image credit Alisdare Hickson via Flickr (CC).

When researching my book on the ultras phenomenon in Egypt, Cairo���s Ultras: Resistance and Revolution in Egypt���s Football Culture (2019), I was surprised to discover how little has been published on football literature concerning the Middle East and North African (MENA) region. Apart from a limited number of journal articles, newspaper reports of different sorts, and various types of book publications, little has been written on football culture in Egypt per se. In particular, the Cairo ultras had not been looked at in a meaningful way as a significant social movement in recent years. However, as I began to write this reading list, I was pleased to hear of a new pending book by anthropologist Dr. Carl Rommel and look forward to more publications of this kind in the future.

Therefore, my own reading list was wide-ranging because my approach to the Cairo ultras was based on my own experiences during the Arab Spring and its immediate aftermath. This research project on football cultures began with a film, More Out of Curiosity; from which I went on to develop two subsequent films of football and politics in Brazil and Palestine. The readings that developed my Cairo���s Ultras book looked at the ideology underpinning sports organizations, media networks, and ultra fan resistance to the culture of capitalism. This placed the football fan in a wider debate on representational politics that focuses on collectivity in the live event, and how the aesthetic experience shapes the political.

In this way, the writings of Jacques Ranci��re were formative, and his book The Emancipated Spectator (2008) provided a key framework to consider the politics of the aesthetic moment. In this publication, Ranci��re continues his philosophical thinking on aesthetics and how social agency lies behind appearance. His examination of politics explores various art practices and radical theater works where the audience is challenged beyond straightforward passive spectatorship. Ranci��re���s argument considers the viewer as an actor to move from a position of submission to one of active participation, in what he calls “Choreographic Community.” The closure of the gap between performer and audience is in fact a radical transformation of inequality itself and becomes a political act based on the removal of labels that are underwritten by the hierarchies of knowledge. Drawing on his earlier works, such as, The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation (1991) and Platonic discourses, he weaves together a political and poetic book that, in some ways, summarizes much of his philosophical canon into a short but deeply provocative and engrossing publication.

Research into aesthetics brought me to an accomplished publication, Art, Anthropology and the Gift (2014) by Spanish anthropologist Roger Sansi. Sansi successfully identifies shared methodologies of both art practice and anthropology through the reading of the role the aesthetics play in forming and shaping collective bonds and community. What was most useful to my research was how he expanded the concept of aesthetics, often understood to privilege the Western cerebral perspective, to embrace a wider global critical thinking that includes diverse cultural practices. Specifically, the notion of ���Corpothetics��� coined by fellow anthropologist Christopher Pinney in relation to his research on Indian photography. Here, the sensual, corporeal, tactility of the somatic is emphasized over the contemplative in an inversion of bio-politics, a disciplinary mode of domination. This form of bodily aesthetic experience is based in movement. While, Ranci��re���s work remains closely attached to Enlightenment ideals of aesthetic experience, Sansi���s book outlines different anthropological debates on the immediacy of the sensorial in praxis, which closes the gap between subject and object and the detachment of the senses from everyday social life. This visceral vitality in the everyday patterns and rhythms of life removes hierarchies to emphasize collective identity over individual needs and the human imagination over commodity culture.

This research on the sociological approach to the role of aesthetics was extended to think about the Global North-South relations and debates about resistance to neoliberalism. Amongst the critical theory literature I was indebted to was the book Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (2016). Authors Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams present a radical economic vision of a future world where work is no longer central to human life and society as automation replaces orthodox labor roles. Amongst the proposals of the book is a revolutionary reconfiguration of free time as pure leisure and other non-monetary pursuits, as a system of universal income substitutes salaried employment for the workforce. In this book, the writers outline how the political struggles of the 20th century have mostly failed and they label them as a type of ���folk politics,” while the real power of global financial systems and multinational corporations has remained unperturbed. They suggest that in order to really challenge the neoliberal global order, new forms of resistance are required to take on financial systems and the logic of capitalism. This book has become more poignant than ever given the challenges of this new decade.

Writing in this article in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis is redolent of the three books mentioned, as the virus has exposed the fragility of anthropocentrism and its unsustainability into the future. My own book, Cairo���s Ultras, is a modest contribution to address how the future is inscribed in the present. In the current moment, we may now be facing another tipping point of progressive change, witnessing the debunking of capitalism and the repurposing of technology in order to make it truly useful to a global society.

April 17, 2020

The contested narratives of a dead man’s legacy

Daniel Arap Moi in 1979. Image credit Rob C. Croes via Wikimedia Commons.

This post is from a new partnership between the Kenyan website The Elephant and Africa Is a Country. We will be publishing a series of posts from their site every week. Posts are curated by Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

The death of former president Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi has drawn mixed reactions from various quarters. On social media, there are those who are feting his strengths, from his health and discipline in keeping physically fit, to the Maziwa ya Nyayo school feeding program, to keeping Kenya ���an island of peace.��� Then there are those who remember him as the man who ruled Kenya with an iron fist, under whose regime there were several hugely controversial and still unresolved murders, most glaringly that of former foreign affairs minister Robert Ouko. Then there are those others who, in cynical Kenyan fashion, are demanding a public holiday because���well, I am not sure why, but that���s just the Kenyan condition, in its fearful and wonderful glory. To say the reaction to Moi���s death is a mixed-bag is an understatement. That different people have different ideas of his legacy should not be something to be resisted, but something to be accepted and celebrated.

I remember as a child in the early 90s sitting with my late dad, an avid historian���and my sisters, watching Moi on television addressing a huge crowd. One of my sisters wondered why people would choose to come out and cheer such an awful politician with such a terrible political record. (For context, I was born and raised in a region that made no bones about its disdain for Moi. Combine that with a household that approached politics with a critical fascination and that conversation wasn���t out of place.) It is my dad���s response that I so clearly remember: ���Regardless of what we know or think about him, look at that turn-out, history will judge him as a popular man.���

In a country with a short memory, a terrible grasp of history and a hugely youthful population where more than two-thirds is under 25 years old, it may be difficult to recall a time when the level of expression and openness we are currently experiencing was unheard of. That we can say what we think about the late president should be celebrated as a sign of freedom of expression, one that wasn���t available under his regime. Moi is like that elephant in the old poem that several blind men touched and interpreted to be different things. Just like the elephant was a wall, a fan, a tree, etc., Moi was a dictator, a tribalist, a corrupt individual, a political strategist of Machiavellian genius, the man who ruined a country, the tree planter, the gabion builder and, of course, just Baba. Baba who walked with his ivory rungu (with all its phallic symbolism), the emblem of his power and exclusivity. Moi was all these things to different people.

However one felt about Moi, we can collectively agree that Moi made his presence felt everywhere. It was in the way his activities dominated the news bulletins, in the way graduation ceremonies were at the mercy of his diary because he was chancellor of all public universities. It was in the way we were reminded of his benevolence through the milk that was periodically delivered to primary schools. It was in the way development projects were withheld from the areas of the country he perceived as opposed to him. It was in the way schools and other public institutions were named after him. It was in the way he hired and fired senior government officials on a whim and kept them glued to the one o���clock news. How he mastered and liberally weaponized divide-and-rule politics, creating and destroying political careers like the all-powerful sovereign he had fashioned himself to be. It was in the various random acts of kindness he extended to certain citizens, for which the recipients were eternally loyal, whilst others viewed them as nothing but exercises in pious performativity. It was in the way he named a public holiday after himself, and on the very first Moi Day got the popular Congolese musician Mbilia Bel, then in the prime of her career, to re-write one of her hits and perform the song live in praise of his regime. It goes without saying, the song was played all the time on national radio. Many other songs were composed in his praise, ad hoc compositions for the numerous harambees he attended. Moi also captured the national imagination with his almost invisible private life. The wife we only heard about, but never saw, not to mention the rumors of the incident that led to her banishment. Moi captured the state, made the ruling KANU party his domain, and remained a fixture in the visuals and imagination of Kenyan citizens. He was the Sun King of his time, l�����tat,��c���est moi could have been his alternative slogan���it certainly was the zeitgeist of the time for those who remember his rule.

It is Moi���s luck that he ruled at a time when the flow of information could be controlled by the government. With limited independent news and TV stations outside of the compromised state broadcaster, it was difficult to get news narratives outside of what the government wanted reported. Distance, in terms of geography, and a lack of freedom of speech meant that we got to hear what the government wanted us to hear, any alternative stories were quickly killed. And, if they couldn���t be contained they would be easily delegitimized. Of course, it really helped that his regime existed in a technologically different time, before the era of citizen journalism. He did not have to deal with the narrowcasting headache of citizens practicing everyday resistance by filming, shaming and naming his political misdeeds, socially organizing beyond geographical limits, and demanding political accountability.

And so, there are stories that we will never know unless we actively endeavor to record them as part of our history. We will never know the accounts of the victims of tribal clashes in Kenya, particularly the 1992 clashes. The Parliamentary Select Committee chaired by Kennedy Kiliku compiled a report, popularly known as the Kiliku Report, but it was shot down by Members of Parliament and its findings aren���t available to the public. One of the few things we do know is that six cabinet ministers were adversely mentioned in the report and they wasted no time in pre-emptively lawyering up. This is but one example of the histories that we have failed to record under the Moi regime.

Reminders of Moi���s violence are present with us, physically and metaphorically. They are in the Nyayo House Torture Chambers, where unspeakable acts of violence were committed against people whose only crime was to have a contrary imagination of societal happiness. They are in the shame of our complicit national silence, that we refuse to honor these individuals who risked so much to give us the political freedoms we enjoy today. The freedom that allows me to write this article, which at the time of my birth would have been labeled seditious material, eliciting dire consequences. It is in the failure to open the torture chambers to the public as a memorial to our dark history. We are reminded of him by the Nyayo Monument at Uhuru Park, which looms over the city like an avenger ready to whip errant citizens back into line.

Perhaps Moi���s greatest political legacy is being felt today as his political acolytes of the early years of his rule now run the country. In a country that is struggling economically and experiencing a social breakdown of order of sorts, many have been quick to draw the symmetry between the current times and the economic dire straits of the Moi regime, especially from the 1990s to the early 2000s. The Jubilee government has been kind to Moi, sanitized him some will say, and helped erase his little black book of political misdemeanors, leaving in its place the image of a benign granddaddy/Baba whose leadership Kenyans fondly miss and yearn for. More glaringly for those pursuing the symmetry angle, is the transition politics Kenya is currently undergoing. Deputy President William Ruto is facing hostility and frustration from sections of a government that he is part of, and this has been linked to efforts to prevent him from ascending to power in 2022 when President Uhuru���s term comes to an end. Ruto���who entered into a political pact with Uhuru Kenyatta in 2013 as a way of countering the charges brought against both of them at the International Criminal Court in The Hague���has been likened to Moi, who faced humiliation and opposition from a section of President Jomo Kenyatta���s regime.

As Kenyans get to express their various opinions about their second president, he will also be remembered abroad. For the people of South Sudan, there will be those that will remember the support Moi gave to the Sudan Mediation Process in one of Africa���s longest-running conflicts, a process that, under the stewardship of Rtd. General Lazarus Sumbeiywo, led to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 and ultimately to the birth of South Sudan as a nation state in 2011. During the Sudan Civil War, the Kenya government gave the Sudan People���s Liberation Army (SPLA) leadership tacit support, allowing them and their families to live in Kenya and taking in refugees from South Sudan. Kenya���s role during the Cold War cannot go without mention either. As a littoral state, geographically positioned in the horn of Africa, Kenya was of great interest to the Cold War powers. The country allied itself with the capitalist Western Bloc and proved to be a significant American ally, signing military agreements giving the US naval access at the coast. At a time when most countries in the Horn were deemed to be socialist-leaning, Kenya became a key entry point for the Western Bloc in the proxy Cold War excursions in the Horn of Africa.

A lot can be written about Moi; these contested narratives about him should be taken as a boon, an opportunity to write the complete and contrary histories of this man who ran a country for 24 years as head of state, but whose political career preceded the birth of Kenya as a nation state. This was a man who joined the Legislative Council in 1955, was part of the Lancaster House delegation of Kenyan leaders that negotiated our country���s independence. Moi was in the first opposition government of newly independent Kenya as a member of Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU). He served as a cabinet minister and eventually as vice-president under Jomo Kenyatta. All this took place more than two decades before he ascended to the presidency. All Kenyans, and specifically the critical thinkers of our time, ought to explore the structural consequences of Moi���s regime on the Kenyan condition. While Moi might have been credited with keeping Kenya peaceful during his tenure, as events in 2007/2008 would show, this was but a Potemkin village whose internal contradictions eventually unraveled. The vagaries of Moi���s regime, the physical, economic, political, and psychological violence all took a toll on the nation state; something had to give. He perpetuated a political legacy that he had inherited, where the country was at the mercy of powerful political and economic interests keen on extracting and enriching themselves. Beyond the political repression were the economic consequences of his regime: rampant looting and corruption. It is our responsibility to critique these political and economic actions and their effect on the social breakdown of our society.

That we must deconstruct and interrogate Moi���s political career is not just about freedom of expression. It is our civic duty. It is our responsibility to future generations whose only glimpse into who this man was will be in the written and oral histories we will leave behind. We should as a nation engage with this man���s political career, especially since he was present during so many critical political moments in Kenya���s history. Part of understanding our history involves understanding pivotal political personalities around this history. So we must critique him, we must hold him accountable for his wrongs, we must allow the stories he suppressed to be told. This is as necessary as it is cathartic. This exercise can be the beginning of an exorcism that this country���s troubled soul so desperately needs. From Moi���s death we can find life, we can choose to reconstruct what our country will look like into the future as we discard the ills his regime, and those before him, foisted on us. From these contested narratives we can set a new trend where we honor dead public figures by thoroughly examining what their life as a public leader was. This is how we create a culture of transparency and accountability, holding our public leaders accountable in life, as well as death, particularly those whom we couldn���t fully hold to account when they were alive. Ours is a nation with a troubled soul, this could be the beginning of our healing.

Moi���s death will certainly expose Kenyans to an experience similar to what Zimbabweans went through following the death of their founding father, Robert Mugabe, in 2019. There are those that will love him and will let that love come shining through. There are those that will hold him accountable for the grievous political, economic, and social injury he inflicted on the country and its citizens. For those whom he wronged, the victims that never received recognition, compensation, and/or closure, they will experience a myriad of emotions; from anger at justice miscarried to sadness. This is a time when they are likely to relive their trauma at the hands of the former president. The Kenya government’s position is clear: instructions for flags to be flown at half-mast, national mourning up until the burial, and a state funeral. A hero���s send-off. Given that the President and Deputy President have a shared history with the late former president, this doesn���t come as a surprise. For the rest of Kenyans, we are passionately split into two constituencies: those that remember him as vile and reprehensible and those that remember him as Baba. Then there is that other constituency that couldn���t care less, the one that just wants a public holiday.

To remember selectively

Nyakane Tsolo. Image via author.

On March 21, 1960, my father, Nyakane Tsolo, only 20 years old, led the Positive Action Campaign Against Pass Laws march in Sharpeville Township, south of Johannesburg. The march was organized by the newly formed Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). A few years later he went into exile, via Lesotho and Egypt, to East Germany, where I was born.

Why is it that 26 years after so-called democracy was introduced, the South African public and the world at large do not know about Tsolo? How come the telling of stories around Sharpeville have never considered to dare mention his name���or any of the names of the other PAC leaders in Sharpeville? While my father led the Sharpeville March, Philip Kgosana led the PAC March in Langa in Cape Town. Zachius Botlhoko Molete led the PAC March in Evaton south of Johannesburg, while George Ndlovu led the PAC March in Alexandra Township and Robert Sobukwe led the PAC March in Soweto.

Perhaps, they belonged to the wrong side of history, the wrong side of the fence; but they belonged to one political organization and not another. And this rendered them as persona non grata, unwelcome figures in the domain of history telling, people of no significance, shadows of history to be forgotten. This is why we seriously need to reflect on the construction and narration of public memory about historical events and public holidays in South Africa. The mere fact that Sharpeville Day has been renamed as “Human Rights Day”���just like the Soweto Students��� Uprising was also renamed ���Youth Day������attests indeed to part of this denialism and distortion.

This past February 27, 2020, marked the 42nd anniversary of the death in banishment of Professor Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe by South Africa���s apartheid government. In remembering Sobukwe, a lecturer in African Studies at Wits University in the 1950s, we must introspect, look deep within ourselves to weed out any vices that make us less of the beings we ought to be: free and dignified.

Last month, March 21st, 2020, also marked the 60th anniversary of the Sharpeville-Langa Massacres, as well as 54 years since the proclamation of this day as the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination by the United Nations (UN) in 1966.

This year is merely 26 years since the end of formal apartheid. Judging from the denialist utterances of former apartheid President Frederik Willem de Klerk, and subsequent statements made by the FW de Klerk Foundation in February 2020 (De Klerk insisted apartheid was not a crime against humanity and dismissed it as ���Soviet propaganda���), it is evident that there are still unresolved questions in this country, particularly issues that continue to poison and distort the narrative of our history, national consciousness and our collective memory.

One such poisonous issue is apartheid denialism and the historical distortion of our past and historical facts related to the collective experience of black people in Azania (South Africa).

In fact, this denialism and distortion extends far beyond the realm of apartheid, it stretches right into the periods of settler imperialism (starting with the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck), the enslavement of AbaTwa (Khoi and San) in the Cape, and reaches into the colonial period into the colonial period-especially since narratives around these histories remain distorted and dismembered.

Apartheid denial and historical distortion refers to the dismissal of irrefutable and established facts, as well as the deliberate and intentional whitewashing, downplaying of the actual brutal, savage and barbaric events and experiences of black people during the white days of apartheid rule. Such denialism and distortion���operating to ease white guilt���belittles the suffering of the victims and survivors of the atrocities perpetrated by the racist apartheid government and its institutions. In my view, apartheid denial and historical distortion are a form of hate speech, a continued violation that dehumanizes the victims and survivors, and aims to justify the acts of barbarism meted out on the African masses by white society. Part of this denialism is the very deliberate act of distorting and misrepresenting historical facts���the silencing meant to to completely erase from public memory the role played by many ordinary citizens and activists like my father, Nyakane Tsolo, the PAC leader who led the Positive Action Campaign Against Pass Laws in Sharpeville.

However uncomfortable this might sound, the ruling party African National Congress (ANC) has played a big role, whether intended or not, in enabling this gross denialism and historical amnesia exhibited by the likes of De Klerk.

The negotiated settlement at CODESA (the forum where the apartheid state and the ANC negotiated a post-apartheid order), the privileging of a ���Sunset Clause��� (whereby apartheid civil servants would keep their jobs), and the theatrics of ���forgiveness without repentance��� displayed at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) set the stage for the De Klerks of this world to insult black people. But the denialism and distortion extends beyond De Klerk the individual right into the realms of white society, the curricular, how we teach history, what histories we teach, how we remember, recollect and repackage the past.

Our current approach to how we tell narratives about apartheid is selective and partisan, demonstrating that we have no inclusive approach to historical remembering. We remember selectively and we forget collectively. The denialism and distortion demonstrates that how we choose to commemorate our past, how we tell stories, how we re-member or dis-member events; from Sharpeville to Boipatong, and Northcrest to Marikana.

These annual, pompously decorated state ceremonies, publicized and splashed all over media, have become repugnant spaces of no particular significance, void of any historical substance. They are events where the painful history of our struggle becomes sanitized. The ease with which we accepted the redrafting of our history, all in the name of reconciliation, presents to the apartheid denialists the picture that we ourselves don���t take our reality, our experience, and our history seriously. We have become so desensitized and disconnected to the pain, experience and evils of apartheid that we even allow the likes of De Klerk to belittle and insult our people without any consequence; simply because we don���t honor, acknowledge and respect our veterans and ancestors enough.

Whilst we must condemn racists like De Klerk without fail, we must also introspect and interrogate our own complicity in enabling and accommodating white supremacy and supremacists who feel like they didn���t kill enough black people under apartheid.

By failing to challenge apartheid denialism and historical distortion, we risk the danger of repeating false narratives and thereby blurring the line between historical truth, lies or propaganda. This calls for a serious reexamination of the educational system. And certainly, the decolonization of the curriculum that the #FeesMustFall campaign called for remains relevant, albeit the latter remains unattended to, unresolved, and unaddressed.

We need to ensure that we, and generations to come, are well equipped to distinguish and decipher facts from fiction. People all over the world guard their history; they ensure that denial is rooted out, and criminalized. We must do the same, without any fear or shame.

We owe it to our forebears.

April 16, 2020

South Africa���s one-sided lockdown: coercing the poor, coddling the rich?

Minister Tito Mboweni delivers 2019 Budget Speech. Image credit Government of South Africa via Flickr CC.

From the perspective of reducing the negative public health effects of the coronavirus, national lockdowns will almost certainly���if adhered to���reduce the number of coronavirus transmissions while they are in place. The important question of when, and for how long, to implement them remains a matter of debate. But the main concern with such policies is their negative consequences for economic activity (businesses and workers) and other aspects of people���s well-being. While all countries will suffer on these dimensions, less wealthy and more unequal countries will experience greater relative harm and have fewer national resources available to offset this. Every state has to grapple with, and adequately answer, the question as to how they will offset the harms caused by lockdowns. And it is primarily these costs that make the question of viable ���exit strategies��� almost as pressing, and contested, as how individuals are expected to survive while they are in place.

There is not yet reliable evidence as to whether death rates vary significantly by socioeconomic status in South Africa or elsewhere. Given that the virus causes death among those with underlying health conditions and through respiratory mechanisms, there are very real fears that the proportion of deaths could be worse in a country like South Africa where HIV, tuberculosis and other diseases afflict a significant portion of the population. Yet it is also clear that personal wealth is no guarantee of recovery. So while lockdowns in countries like South Africa are sometimes rationalized as being for the benefit of the poorest and worst off, they arguably benefit the well off at least as much. However, when it comes to the downsides of drastic measures, whatever their direct public health merits, the already-poor and vulnerable are unquestionably the worst affected. Poverty and inequality research abounds in South Africa, so there is no shortage of statistical information and analysis of how stark the already-obvious divides are. A particular concern in the current context is the risk of hunger and starvation.

That means a lockdown without significant compensating social and economic policy measures amounts to an inequitable socialization of the cost of this public health intervention: the poor suffer relatively more than the rich for the same benefit to society. Besides being profoundly unjust, and exacerbating existing inequalities, this could also ultimately undermine the public health benefits in the longer-run of the pandemic.

A bourgeois logic?

This perspective does not shine a flattering light on the South African government���s current approach: whether or not the lockdown was the right decision at the right time, it is a relatively stringent intervention but with compensating measures that so far have been much smaller than in other countries and are inadequate to protect much of the population. Furthermore, these measures focus disproportionately on formal businesses and workers, neglecting casual labor, the informal sector, and the broader population who survive on state grants and the scraps of the formal economy.

It was evident before the lockdown decision was taken that a political climate had been created amongst the chattering classes in which less-drastic measures were associated with bigoted clowns like Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, while more drastic measures were associated with authoritarian countries like China that seemed to be getting their epidemics under control or democratic nations with leaders who deferred to scientific advice. For that reason alone, it seemed likely Ramaphosa would err towards drastic action. But in addition, many of those who most loudly called for, and subsequently, endorsed the lockdown were part of a small elite who are relatively protected from its immediate consequences. Among these are permanently-employed academics, senior civil servants, civil society players receiving donor funds (at an increasingly favorable exchange rate), and journalists who could continue operating as ���essential service workers��� anyway.

An interesting paradox is that many of those calling for a lockdown did so on the basis that government should defer to ���scientific evidence,��� but had little or no capacity themselves to understand or critically interpret such evidence internationally or for the South African context. But that is something for another time.

A striking failure is the half-hearted effort to raise funds in the face of the state���s reluctance to borrow���for reasons discussed below. The power to tax is often argued to be at the core of the modern state, yet while the coercive power of the state, via the police and military especially, is being used (and abused) in South Africa to keep poor people in their homes and away from work, it is not being used to tax the wealthy. (In the early days of the lockdown, the number of deaths from police brutality almost matched the number from the virus���though some have argued that this is just ���normal��� police brutality under a different guise). One consequence of this approach has been a reliance on the philanthropy of the local super rich, rather than simply taking a portion of their wealth to ensure the survival of the society they have profited from.

That decision is significant in a broader political economy perspective. The Ramaphosa government adopted a policy approach which enabled the local super rich to frame themselves as benevolent philanthropists, personally named and thanked in the president���s addresses to the nation (see his ���Solidarity Fund���). That has carried over into the press. In truth, every precariously employed person who adhered to the lockdown for a week probably sacrificed more in relative terms than any of these billionaires through their donations.

Meanwhile, a number of commentators in the press���particularly in the business press���have suggested that the crisis presents an opportunity for Ramaphosa to establish sufficient leadership credentials to push through ���structural reforms.���

What are these ���structural reforms���? Nothing and everything. First, an empty vessel: the South African economy has been performing poorly, it is tautological that it needs structural reform. Second, a Trojan horse: private sector interests are seeking to use pressure on government finances and energy generation capacity to implement a series of quasi-Thatcherite reforms. Privatizing state-owned enterprises beyond what their current state requires, weakening unions, introducing private sector competition into sectors like rail transport through misguided economic regulators, and so forth. The intent is encapsulated in a piece by a recent CEO of Business Leadership South Africa which misleadingly weaves together different strands of the country���s pre-coronavirus state to conclude that: ���Because the government currently has no money, our only salvation is business.���

In his most recent speech, these sentiments were echoed by the Finance Minister: ���Most importantly, the crisis is an important opportunity for government to implement structural reforms to: restructure the network industries; liberate SMMEs to be the engines of growth and employment; and broad-based measures to lower the cost of doing business.���

On the funding side it could be argued that, pragmatically, donations and charity are easier than tax, which would require new or amended legislation to be approved by Parliament. Avoiding that, however, suggests government has little faith in, or wants to avoid the scrutiny of, a pillar of constitutional democracy. In doing so it also evades broader public accountability and scrutiny. And indeed, even existing measures that require legislation are being treated like they will be rubber-stamped, confirming that Parliament���s ineffective oversight in normal times continues even during such critical periods.

While legislatures in other countries like Kenya and Canada are putting together serious, well-substantiated policy options, South Africa���s highly-paid parliamentarians and parliamentary staff are missing in action. Despite requests from the main opposition party and civil society, senior office-bearers appear to have opted for an extended holiday under the nonsensical excuse that they cannot be seen to be interfering in government decisions during a crisis.

Proposals from civil society

As has often been the case since 1994, it is left to civil society organizations to pressure government for greater accountability and social protection. Even as some, including ANC parliamentarians, have argued that the state should be left to make its own way unhindered, broad coalitions have formed rapidly to ensure accountability and that ordinary South Africans��� interests are considered. Unsurprisingly, much of this activism relates to pre-existing concerns that are likely to be amplified by the pandemic and many measures to address it. These include domestic violence, spatial dislocation, hunger and food insecurity, educational inequality, limited access to healthcare including mental health support, and many others.

Unlike in normal economic downturns the initial problem is not that people and businesses do not want to buy and invest but that they are prevented from doing so. As others have noted internationally and in relation to South Africa, framing economic policy responses as ���stimulus packages��� suggests a misdiagnosis and incorrect prioritization.

One very specific proposal has been to increase the existing, monthly child support grant. This makes sense because it requires little additional capacity from the state and gets cash into many poor households. Doing so addresses the immediate priority of social protection and has the secondary benefit of providing some stimulus to the parts of the economy still allowed to function.

Another set of 18 broad proposals calls for everything from state-facilitated childcare for essential service workers to a grant of R1,000 (about US$100) per person per month for four months. Many of these seem desirable.

But where should the money come from?

Making proposals on how best to spend money is a worthwhile exercise but arguably not the hardest. There are some major practical difficulties that civil society proposals have demurred on. Public finances were already in a dire state prior to the crisis. The negative impact of the lockdown and global economic downturn on the local economy will reduce tax revenue substantially and worsen measures of public finance stability. Already big tobacco has been arguing that the restriction on cigarette purchases should be lifted because of the millions the government is losing in excise duties. And while the lockdown has ended the country���s loadshedding by the national power utility Eskom, it also expected to lose R4 billion in revenue in the first three weeks of the lockdown���compounding a dire financial situation that had already necessitated enormous bailouts from the Treasury.

Another issue is that the state often fails to deliver services in normal times���as civil society organizations often point out. Such basic capacity issues will not change during a crisis. At best, desirable outcomes might be achieved by focusing existing strengths on a small number of priorities. But that necessarily means that a large range of important concerns will be neglected.

Unwillingness to seriously consider costs and trade-offs is not uncommon in civil society. And in the current case is arguably the result of unconditionally enthusiastic support for the lockdown: many are unwilling to consider that saving lives might come with intolerable costs, including to the lives of those it is supposed to protect. This is reflected in the narratives of most opinion pieces which are premised with a statement along the lines of: ���We recognize the lockdown was essential and applaud the bold and decisive leadership ������

Taking as given the necessity of a lockdown is an unwise stance that will seem less and less advisable as the current situation persists. Responsible decision-making requires giving some serious thought to the alternative, even if one ultimately decides against it. And here again one wonders how much a certain bourgeois logic is at play, when premature death is so much a normal part of many poor and vulnerable South Africans��� lives. The seemingly benevolent argument that ���we cannot choose the economy over lives��� ignores the historical fact that this is precisely what has been done for centuries in South Africa���including in the post-apartheid period. Curiously, some South African commentators have found it easier to see the problem elsewhere, through Arundhati Roy���s poignant piece on Narendra Modi���s lockdown in India as an extension of his general brutality.

To the numbers, then. Proponents of an increase in the child support grant (in an open letter published on The Conversation) estimate it would cost R6.2 billion per month: R74.4 billion if maintained for a year. That would be a 35 percent increase in the current social protection budget, or three times the R23 billion total allocation to HIV/AIDS, but is merely referred to as ���certainly not a prohibitive cost.��� Since the current lockdown could be extended further, or reinstated later, and negative economic effects will linger for some time, it is not realistic to think of interventions as only covering the existing lockdown period.

Similarly, the signatories to the open letter provide no cost estimates for any of their proposals, only one of which (a proposed allocation of R1,000 per person for four months) could cost in the realm of R220 billion: equivalent to 14 percent of proposed non-interest spending for 2020/21, or the entire social protection budget.

It is important not to lose sight of the recent history of South Africa���s economy and public finances. The country���s efforts to emerge from the aftermath of the global financial crisis have failed. And that has recently been reflected in the downgrade of the country���s sovereign debt to sub-investment (���junk���). Contrary to some slightly hysterical claims at the time, the country had arguably been benefitting from a favorable view of Ramaphosa by the last ratings agency, Moody���s, that delayed its decision to downgrade the country long after the other two main agencies had done so. In contrast to what some critics claim, the government did not adopt an austerity policy after the crisis: public expenditure continued to grow as planned, so the collapse in economic growth and tax revenue meant a relatively rapid increase in national debt relative to the size of the economy (���debt to GDP ratio���). It would be an exaggeration to call that a stimulus, but the (sensible) intention was to try and use the government���s role in the economy to offset the downturn in the private sector and smooth the path to a recovery.

But the recovery did not come���partly for external reasons but increasingly due to internal failures associated with state capture. That led to the adoption of a policy of ���fiscal consolidation,��� which simply meant designing budget proposals to align with a tapering off in increases to the national debt to GDP ratio. As those targets were also missed, the government introduced measures in some expenditure areas that equated to austerity by stealth. Notably, in the healthcare sector, this has involved capping personnel budgets in a manner that would inevitably lead to reductions in personnel, albeit accompanied by rhetoric that ���frontline posts should be protected.��� Such historical policy stances provide an important backdrop to the current crisis in developed countries like the UK (even as the conservative tabloid press try to turn it into a triumph for the culprits) and developing countries like Ecuador.

Beyond the usual limitations, one reason for these rather obvious failures in the current context may be that rich countries have rapidly adopted dramatic increases in government spending, partly facilitated by unconventional measures by central banks.

However, whether unconventional monetary policy measures are as feasible for developing countries was already a matter of debate prior to the current crisis. As things stand, most proposals for measures like ���helicopter drops��� and implementing massive economic stimulus plans do not seem to reflect much substantive understanding of such concepts or do the hard work of establishing whether international experiences carry-over to developing countries. While they are based on a correct premise���that government is not doing anywhere near enough���the prescriptions seem remarkably irresponsible given how past fiscal crises wrecked, and were used to destroy, many African countries.

At the same time, the senior leadership of the Reserve Bank (South Africa���s central bank) largely consists of former Treasury officials from the era of President Thabo Mbeki and his finance minister, Trevor Manuel: the same era when the BIG was swatted away, parliamentary oversight of the budget was entirely neutered and the importance of addressing inequality for sustained economic development was sneered at (until the IMF gave this credence decades later). So the South African Reserve Bank would, like the Treasury, also usually be very poorly placed to consider unusual policies to address the crisis. With the foreign institutions that they too-often look to imitate all adopting relatively radical stances, one might have expected past limitations might fall away much more easily���though there is as yet no sign of that happening at the Treasury.

The more substantive challenge is establishing, under very difficult circumstances and with limited time, what radical policies could work in South Africa. Unlike wealthy Western countries, South Africa has less resources per person, less flexibility in its public finances, and receives less generous treatment in global financial markets. For instance, at the somewhat more trivial level of currency fluctuations, while Cyril Ramaphosa has shown markedly better leadership than Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, investors nevertheless rush to dollar and pound assets and the Rand exchange rate hits dramatic lows against both currencies.

While South Africa���s sophisticated financial sector is an advantage in facilitating inflows of foreign capital, it also means that rapid capital outflows are also possible. And in a debatable, and unfortunately-timed move, the government recently announced a relaxation of restrictions on capital outflows���when some experts argue the opposite is required to deal with the current crisis. If anything, there was a case to be made for a tax on speculative and other capital flows, but even serious consideration of such measures would require an independent intellectual capacity that is sorely lacking.

The way forward

While uncosted proposals are being made for new initiatives, there are resources available from initiatives defunct under the lockdown like the national school nutritional scheme which should be redirected. If the state lacks the capacity to quickly repurpose such schemes, as appears to be the case, the money should certainly be transferred directly to households through grants. Furthermore, the state should immediately initiate a process to significantly increase taxes on individuals in permanent employment receiving stable monthly salaries��� most of whom work for large corporations or the public sector���especially in the top tax brackets. And further tax measures will need to be considered after the crisis is over. The bottom line being: those most privileged in the current crisis must contribute substantially, not merely be given an option to donate.

The recent announcement by the President that Cabinet members will take a 33 percent salary cut for a period of three months sets a good, symbolic precedent within the state and has been followed by some other public and private sector officials. But it is less than 10 percent of their annual remuneration and, given their large initial salaries, that still leaves them better off than more than 99 percent of the population. Taxation is ultimately the best instrument for society at large.

Using the existing grants system for such redistribution is a good start, but it is not enough. Had the government, especially the Treasury, and many economists been less hostile to historic proposals for a Basic Income Grant it would be possible to reach almost all those in need. The Treasury���s hostility was, characteristically, merely an imitation of attitudes elsewhere that undermined the construction and maintenance of broad social safety nets. In contrast, the Treasury strongly advocated an employment tax incentive, despite good reasons to believe it would merely be a subsidy to businesses. And subsequently extended it, despite a lack of supportive evidence. In a grim irony, the employment tax incentive system is now being used to subsidize businesses even as those outside the narrow social safety net receive almost nothing.

In the absence of an existing comprehensive social security system, new ways must be found to rapidly transfer support to the neediest. A significant number of them fall outside the current safety net, which is implicitly premised on the notion that the able-bodied of working age who are not in employment or education do not deserve social support. Given the limited capacity of the state, this is a severe challenge.

In terms of funding such initiatives there is some scope for monetary policy to play a role, both at the macroeconomic level and in facilitating state spending. The Reserve Bank���s lowering of interest rates and buying of government bonds, including from the Unemployment Insurance Fund, are sensible measures that contribute to government���s ability to finance current measures. (Though bureaucratic obstacles are already hindering the efficacy of the UIF measures). The appropriateness, feasibility and even definitions of more unconventional measures like quantitative easing remain debated, but have long-term risks that must also be considered. The Reserve Bank also has an important role to play in encouraging and enabling the financial sector to allow individuals and businesses to delay the costs of servicing debt.

But the stark reality is that developing countries, whether in Africa, Asia or Latin America are unlikely to be able to fund measures to offset the consequences of their own chosen interventions, and the international economic crisis, without corresponding international support. It would be unjust if such support were to be anything other than unconditional, but it remains to be seen whether wealthy countries and multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, National Development Bank and others have the will and enlightened self-interest when most nations are busy scrambling to save themselves. There are some interesting proposals on how such support could be structured to avoid some forms of exploitation, but these fail to address the history of neoliberalism and structural adjustment that still casts a shadow over funding from the likes of the IMF.

Meanwhile, such legitimate concerns are also apparently being used by the state capture faction in the ANC to advance an entirely different political agenda and the opposition Democratic Alliance���s enthusiasm for indebtedness to international financial institutions appears deeply suspicious. Yet Mboweni���s recent assertion that IMF structural adjustment will be avoided rings hollow, since it is a certain kind of structural adjustment-type logic that underlies his and the Treasury���s ongoing obsession with deeply flawed conceptualizations of structural reforms. The tragic irony being that South Africa could simultaneously shun international assistance that would be used to assist the poor, yet impose quasi-structural adjustment measures anyway.

Internationally, there are encouraging noises from various quarters about possible multilateral action to assist poorer countries, but time is short. It remains to be seen if anything substantive will come of the initiative by the African Union, currently chaired by Ramaphosa, to raise funds for Africa countries to bolster their fight against the pandemic. And if compensating measures cannot be funded, then lockdowns could have to be lifted for the simple and fundamental reason that they might harm more than they prevent. What is shameful is that almost three weeks into the lockdown and with at least two further weeks in store, the state has yet to announce a package to protect those suffering the most and there currently seems to be little commitment to doing so.

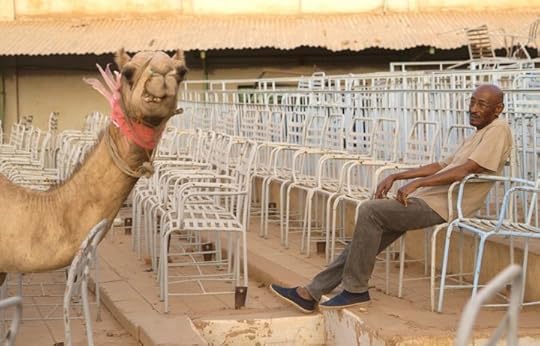

Talking about trees

Still from Talking About Trees.

Jaafar Nimeiry was President of Sudan from 1969 to 1985. This period produced much art about the regime, ranging from the illustrations that filled Ibrahim El-Salahi’s prison notebooks to the poetry of Mahjoub Sharif. In contrast, Omar al Bashir’s reign is notorious for crushing it. The 1989 coup brought with it the imposition of austere Islamic laws that sought to transform the cultural sphere and eliminate perceived heterodoxies: cinemas were closed, books were banned, public gatherings were severely restricted and cultural archives were left to decay. Many of Sudan’s most famous filmmakers, poets and musicians went into prison or exile during in the early years of his regime, whilst others were censored into obscurity. Reflecting the view of many at the time, the late novelist Tayeb Salih (whose book Season of Migration to the North was initially banned by the regime for its sexual references) penned an oft-cited article questioning “From where did these people come?”

Today, in the capital and elsewhere, anti-government graffiti from the dawn of the uprising remains, and the painted faces of martyrs guard the streets. Before it was violently dispersed, the sit-in outside army headquarters routinely featured musicians singing in support of the uprising, whilst activist murals rapidly spread like tentacles across its walls and into the streets. The recent flourishing of revolutionary art, music, cultural exhibitions, and calls to archive the past is often contrasted with the perceived dearth of artistic expression under Bashir.

Suhaib Gasmelbari’s film Talking About Trees takes its name from a Bertolt Brecht poem, one fit for the Bashir era, named “To Those Born Later,” and references the following lines: ���What kind of times are these, when/To talk about trees is almost a crime/Because it implies silence about so many horrors?��� The film follows four aging Sudanese filmmakers in their quest to revive cinema in Sudan, and in so doing, poignantly and often humorously depicts the nuances and frustrations of daily life under the military dictatorship.

Life after the 1989 coup was marred by state violence, mass displacement, and an escalation of wars. It was also characterized by an absurd authoritarian bureaucracy that made the simplest interactions with the state a mammoth undertaking. Control over the cultural sphere would be achieved not only through coercion, but through the construction of a bureaucratic labyrinth featuring an endless list of impossible criteria that seemed designed to frustrate. The act of securing simple permits or updating papers became increasingly lengthy and fragmented, requiring various levels of approval and documentation that often seemed to be made up on the spot.

Talking About Trees traces attempts by four filmmakers���Ibrahim Shaddad, Suleiman Ibrahim, Manar Al-Hilo and Altayeb Mahdi���to screen a film at the defunct Revolution Cinema. It is the above mentioned bureaucratic barriers, from the omnipresent stat, that drive the narrative of the movie. In one scene, their colleague Hana Abdelrahman attempts to obtain authorization from the security services for a film screening and is sent to countless offices, each telling her she needs to go elsewhere for authorization. The absurdity of the circular, never-ending journey is perfectly captured; the security services are never seen in the film but their mark is everywhere.

The moments are coupled with a gentle depiction of a touching friendship between the filmmakers. Like Gasmelbari, the four all studied filmmaking abroad���Shaddad at the Konrad Wolf Film University of Babelsberg in Brandenburg in the 1960s, Ibrahim at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography in Moscow in the 1970s, and Mahdi and Al-Hilo at the Cairo Higher Institute for Cinema in the 1970s���before returning to Sudan to produce several films that would go on to win international prizes. These experiences come through in their works and humor; in one heart-warming scene celebrating Ali-Hilo’s birthday, the four recount the experiences of their generation���colonialism, three democracies and three dictatorships���before going on to mock his age: “Supervised by Lenin himself/And Maxim Gorky/Eisenstein’s classmate!” By the time the film wrapped, the filmmakers would have lived through another popular uprising, culminating in the overthrow of Sudan’s third military dictator.

Gasmelbari allows them to tell these stories and experiences in a way that allows their good-natured, gallows humor to come through. Familiar irritations also abound; the interruptions of poetic moments by the deafening call to prayer emanating from blaring loudspeakers are a familiar occurrence. Countless masjids have mushroomed across Sudan over the years, with six surrounding the cinema at the time of filming. They threaten to drown out the film with their evening call to prayer, and like everything else, the four approach this challenge with humor and pragmatism: viewers will be permitted a prayer break and then, in Shaddad’s words, invited to return “to this place of ill repute” to finish the film.

Touching on deeply political issues such as exile, imprisonment, and interrogation, the film nevertheless confines the faces of the regime to the shadows, centering instead on its everyday manifestations and the daily lives of the filmmakers. The exception is a brief scene towards the end when the 2015 election results are announced in the background; Bashir has won 94.5% of votes and gives a speech saluting the people and democracy in Sudan.

Talking About Trees is a wonderfully understated film about artistic expression and repression in Sudan, inevitably political without being about politics, carefully and unassumingly illustrating the beautiful relationship between four filmmakers who dreamed of returning to a different Sudan, and the ways the regime���kept firmly in the background���permeates every aspect of daily life.

April 15, 2020

Will COVID-19 keep out of Africa?

Image credit Lynn Greyling via Public Domain Pictures.

There is little doubt that the coronavirus has the potential to sweep through Africa with deadly consequences. Some have queried why it hasn���t done so already, and question whether the relatively low number of infections is more a function of the lack of testing. Perhaps this is related to the fact that Africans have found borders to the north being increasingly closed to them in recent years. In November of last year, we organized a conference at the Balsillie School in Waterloo, Canada on South-South migration. Four of our five African participants, all highly-esteemed academics in their own countries, did not receive visas to come to Canada. We were, it seems, caught up in an ���unofficial��� policy of tightening restrictions on all visitors from Africa.

The European Union requires citizens of virtually every African country to obtain a Schengen visa in order to enter any member country of the Schengen Area, which comprises most European countries. Thus, it seems that the borders designed to keep Africans out of Europe have also helped keep the coronavirus out of Africa. Even so, data from South Africa shows that community spread is accelerating following the arrival of European tourists and well-heeled South Africans returning from holidays in Italy. Small wonder that some in poorer communities have taken to calling it the ���tourist sickness.���

The coronavirus COVID-19 could spread extremely quickly in Africa for three reasons. First, Africa���s own borders are extremely porous and cross-border movement���to buy, to sell, and to visit���is commonplace. Countries will try to shutter their borders, but this is a logistical nightmare since land travelers vastly outnumber airport arrivals. Second, Africa���s cities have been growing extremely rapidly. In many cities, a large proportion of the population lives in what are euphemistically called ���informal settlements.��� These areas are sprawling shack slums where poverty is rife, people live cheek-by-jowl, and basic services (like clean water and sanitation) are absent or wholly inadequate. These are not Chinese cities, where millions can be locked-down in residential compounds. They represent, instead, an ideal mass for a contagious virus to spread within. As our keynote speaker at the South-South migration conference, Cecilia Tacoli, has written: ���in crowded spaces, people are forced to share accommodation and���when available���toilets. Residents are constantly on the move, often traveling on packed mini-buses to workplaces within settlements, between settlements, and between the city and rural homes. Attempting to control this kind of movement would be extremely difficult.���

Finally, the residents of African cities are highly dependent on the informal economy for income and food. There are no supermarkets and few formal sector food outlets in large sections of the cities. Our research shows that people depend on informal vendors and crowded city markets for food, and because income flow is limited and irregular, people shop almost daily. Stay-at-home orders and ultimatums are recipes for hunger and food insecurity and are virtually unenforceable for people who need food. South African police have been firing rubber bullets at supermarket shoppers who are not social distancing and pepper-spraying customers at informal shops. Such draconian responses will not keep hungry people indoors.

The health-related consequences of rapid spread of COVID-19 in Africa are almost unimaginable. Europe���s well-resourced and modern hospital systems are collapsing under the strain. Those in Africa would quickly be overwhelmed. Kenya, for example, has a population of 44 million and only 518 critical care beds. Many other countries are even worse off. The brain drain of health professionals to the global North has left many facilities under-staffed and most who remain lack the PPEs necessary to keep the virus at bay. South Africa has a first-world private health system but it services only a small proportion of the population and hardly anyone in the informal settlements and townships can afford the insurance premiums. Public hospitals were seriously overburdened long before COVID-19 arrived. Many residents of African cities have underlying conditions, which it appears from studies elsewhere, will make them more vulnerable to severe infection by COVID-19. Currently there is no definitive evidence that people with HIV are at greater risk of serious illness. But if they are, the prevalence of HIV, tuberculosis, and HIV-TB co-infection are extremely high in the southern part of the continent. Non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes, constitute a rising burden in sub-Saharan Africa as a whole.

The epidemiological evidence also suggests that COVID-19 is generally a relatively mild infection for children and a deadly killer for the elderly. Here, theoretically at least, there is some reason for optimism. Africa���s burgeoning cities are primarily populated by young people and children. The elderly are, by and large, still living in (or have retired to) rural homes in the countryside. The most vulnerable demographic may already inadvertently be self-isolating. However, there are reports in some countries of people leaving the cities (as they tried to do from Wuhan and northern Italy, and are now doing in India) to ���escape��� the virus. We have all seen how well that worked out for the rest of Italy. Migrants trying to leave South Africa are being turned back at the border, but there are fewer barriers on movement within countries if people decide they are better off away from the urban hot spots.

Even if Africa���s cities don���t empty, the reality is that urban-rural links are still very strong in most African countries, and there is a continuous flow of people and goods backwards and forwards between town and countryside. COVID-19 will likely ride in the taxis and buses out of the cities and penetrate deep into the countryside where the most vulnerable live, and where health facilities are even more rudimentary. In time, the bells may well toll loudest in the rural areas of the continent.

I mourn in deafening silence

Image credit Ivo Brandau for OCHA via Flickr CC.

Residents of Ngarbuh-Ntumbaw, which is in Donga-Mantung���one of the two English-speaking regions of Cameroon plagued by conflict between separatist groups and government forces for the last four years in the northwest of the country���suspected nothing when they went to bed on the night of February 13, 2020, hoping that the next day would be like any other. Unfortunately, their morning was brutally interrupted by an alleged army operation which started at dawn and turned into veritable carnage. Indeed, an unprecedented massacre took place on February 14 in the village. Children and pregnant women were among the victims, and the shocking images of their burned and bullet-riddled bodies were widely shared on social media, sparking outrage.

A controversy ensued over the number of victims. According to various reports, there were 22 dead, including 14 children and two pregnant women. This number was confirmed by the spokesperson for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Ruppert Colville, and by the Bishop of Kumbo, a locality in the northwest region, not far from Ngarbuh-Ntumbaw. At this time, it is still difficult to determine the exact circumstances of this horrific killing. But the opposition, local NGOs and some civil society actors, including barrister F��lix Agbor Nkongho and the journalist Mimi Mefo, accused the army of being responsible for it.

The Cameroonian government has formally denied these ���fake allegations,��� arguing that it was an ���unfortunate incident,��� which occurred following the exchange of fire between the security forces and secessionist rebels. But Human Rights Watch (HRW) researcher, Ilaria Allegrozzi, has contradicted the government, claiming it was a planned massacre by security forces and armed ethnic Fulani. HRW has also released a report confirming that at least 21 civilians, including 13 children, were killed. On the other hand, relatives of victims presented a fresco bearing the names of twelve of the children killed in this carnage at a requiem mass in Kumbo.

Defense and Communication Ministers have announced the establishment of a commission of ���inquiry;��� a euphemism often used to calm the controversy and to cover up the misdeeds of the army. In general, the Cameroonian authorities respond in three ways to the accusations against its army: first, they deny all of these accusations, evoking gross manipulation to tarnish the image of Cameroon; second, they accuse local human rights NGOs of having a hidden agenda and of using their humanitarian covers to import weapons from abroad (e.g. the NGO Ayah Foundation is actually accused of bringing in arms for the benefit of the Ambazonian separatists); and third, if indignation seems to be gaining strength, the government will announce the establishment of a national commission of inquiry, preventing the international community from getting involved.

However, investigations are rarely carried out. If they are actually carried out, the reports are never published. In the course of time, the indignation gradually dies out; the perpetrators of the crime go unpunished, and everyone forgets the drama, except the relatives of the victims.

For instance, in July 2018, a horrible video of the killing of two women and their children���including a seven-year-old girl and a two-year-old baby���was circulated on social media. The then Minister of Communication, Issa Tchiroma Bakary, formally condemned a ���vast orchestrated conspiracy��� against the Cameroonian regime, before acknowledging the responsibility of the army a few weeks later, undoubtedly under the weight of international pressure. An investigation was announced, and the government claims to have arrested seven soldiers who are on trial, but no other details have been released to date.

Today, a majority of Cameroonians have lost faith in political actors and don���t believe any promises from them. Rather than winning the battle of hearts and minds, the government until now hasn���t shown much interest; instead it seems driven by a desire to defeat the separatists militarily. In the meantime, the conflict has become more and more deadly.

This conflict also reveals the failure of an authoritarian and hyper-centralized system, which ensures its survival on the basis of systemic and endemic corruption. Cameroon has literally become a bula matari���a Kikongo word meaning stone breaker���used by Crawford Young to describe the colonial and postcolonial state in Africa. The Cameroonian state has managed to defang and fragment the opposition by using both violence and bribes. The state succeeded in squashing people���s protest impulses either by co-opting or coercing those who dissent.

To be very clear, I am not an apologist for Ambazonia, an imaginary state whose independence was symbolically declared on October 1, 2017 by the English-speaking separatist leaders. There is no doubt that the latter have committed serious violations and crimes against civilians. However, I stress that the radicalization, resistance, and ability of the separatists to recruit adherents have been continuously fueled by atrocities committed by state forces. When civilians are killed, resentment is generated, especially among young people, who sometimes end up joining the secessionists to avenge their killed parents.

Whether in the war against the separatists or against Boko Haram in the north, reports from several sources indicate that thousands of civilians suspected or accused of conniving with the ���terrorists������another euphemism used, not only to label the separatists and Boko Haram, but also to combat any social protest in the country���are arrested and detained in inhumane and degrading conditions. For example, in Kossa in February 2015, 32 men were arrested after rumors spread that the village was providing food to Boko Haram.

We should remember that what is now known as the ���Anglophone crisis��� began with corporatist demands from lawyers and teachers who, in 2016, took to the streets to protest against what they called ���francophonization��� of the judicial and educational systems in the two English-speaking regions. Instead of engaging in dialogue with the protesters, the central administration chose a path of repression, arresting hundreds of demonstrators, killing at least four people and wounding several others. Faced with growing complaints against its repressive policy, the government finally met with the consortium of teachers and lawyers, but failed to find common ground, leading to the arrest of some of the people negotiating, including barrister F��lix Agbor Nkongho. Subsequently, a video showing Cameroonian police ruthlessly mistreating students at the University of Buea in the southwest region has further radicalized a section of the population, especially young people. In this video, policemen are seen forcing students, including women, to plunge their face into the mud.

In this way, the horrific images from Ngarbuh are not an isolated incident. They are instead part of a systematic approach. They provide visual evidence that atrocities are committed against civilian populations, including children and women. Some of these violations are now documented and stored in a digital database housed at the University of Toronto in Canada.

Despite numerous calls from national and international NGOs, the international community has so far remained silent, a situation that the former President of Ghana, Jerry Rawlings, vigorously denounced following the publication of the recent massacres of children in Ngarbuh. Rawlings also criticized the failure of the African Union to stop the spiral of deadly violence that is affecting civilians. Recently, the United Nations has stepped up to the plate, requesting an independent investigation to shed light on this tragedy. The US has also called on the Cameroonian authorities for real dialogue, saying that the military response favored by the government will only strengthen the separatists.

French President Emmanuel Macron also denounced the intolerable human rights violations after pressure from an activist at the Paris International Agricultural Show. ���I will call President Paul Biya next week and we will put maximum pressure on him to stop the situation. [���]. I am doing my utmost,��� Macron said.

Yet, France has always offered its diplomatic umbrella to the Cameroonian regime, particularly when the European Parliament adopted a resolution on April 2019 to condemn the gross human rights violations perpetrated against opponents and dissidents. During an official visit to Nigeria in July 2018, Macron publicly underlined his support to Paul Biya. But the Ngarbuh massacres could be a turning point in the political relationship between Cameroon and France. Some Cameroonian politicians have already strongly condemned Macron���s words. They propagate conspiracy theories on social media which allege that France and the USA are the main actors in this ���hybrid war,��� acting through their ���separatist puppets.��� Some media like Vision 4 and Afrique Media have also taken up this idea of a destabilization plan sponsored by foreign powers to control the succession of Biya, who recently celebrated his 87th birthday; 38 years of which he���s been in power.

At the same time, some political actors supported students to organize a demonstration in front of the French Embassy on February 24 to denounce the ���condescending attitude��� of Macron towards his Cameroonian counterpart. Rallies were also organized in other cities of Cameroon, including Garoua and Bafoussam.

In such a context, Paul Biya can continue to sleep peacefully and to retain power for a long time to come. He was re-elected with 71 percent of the votes for a new seven-year term in the presidential elections held in October 2018. His party, the Cameroonian���s People Democratic Rally (CPDM), has at least 150 of the 180 seats in the National Assembly. The road is clear for Biya to keep his prophecy of 2004: that of governing Cameroon for another 20 years. As Achille Mbembe joked, he might even be able to rule from his grave. The use of repression, both by the army and armed movements, which have assumed the right to administer death as they see fit, will also probably continue.

Meanwhile, the people of Ngarbuh will continue to mourn the loss of their loved ones without any justice for their deaths. How long should the Anglophone populations continue to live in the cauldron of the crisis? And are the international community and the African Union really powerless to stop this fratricidal war, or are they just indifferent?

April 14, 2020

Destroying public trust during a pandemic

Tom Thabane, Lesotho's Prime Minister, in happier times with the Obamas. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The arrival of the coronavirus COVID-19 on the world scene has profoundly disrupted many aspects of life for people on every continent. Whether for lack of testing or because Lesotho somehow has managed to escape the fate of anyone infected crossing the border, it is one of two African countries at the moment still reporting zero cases of the virus locally. The country, however, still followed South Africa in declaring a three-week lockdown that has brought most of the country to a standstill. This has been profoundly disruptive to many people, especially those who work in the informal sectors.

One area that was stilled prior to the lockdown was Parliament. Embattled Prime Minister Tom Thabane prorogued that body on the 20th of March, declaring that it would not reopen until mid-June. While Thabane claims he shuttered Parliament on account of the COVID-19 virus, keen observers note that the country did not go on lockdown until nine days after Parliament was closed, suggesting the closure was done to keep Thabane from losing his position as Prime Minister. This all comes on the heels of Thabane and his wife, the First Lady Maesaiah Thabane, facing murder charges���the first time a head of government on the African continent has been charged with murder while still in office. The charges have led to serious political fallout, upending political alliances, and bringing the long-standing fissures in the ruling All Basotho Convention (ABC) to a head. Coalition partners (the Basotho National Party (BNP) and the anti-Thabane faction in the ABC) along with the main opposition party (the Democratic Congress (DC)) brought a case in the High Court challenging the closure of Parliament as illegal. Despite the lockdown, that case is ongoing with arguments heard on Monday the 6th of April.