Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 185

April 2, 2020

A Letter Unanswered

Franz Fanon getting on a boat. (Leo Zeilig / I B Tauris / HSRC Press -

South Africa)

���Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the EarthTo quote the biting words of Senegalese patriots on the maneuvers of their president, Senghor: ���We asked for the Africanization of the top jobs and all Senghor does is Africanize the Europeans.���

In his 1961 book, The Wretched of the Earth, Martiniquais political philosopher and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon wrote, ������Negro-African��� culture grows deeper through the people���s struggle, and not through songs, poems, or folklore.��� The context was a scathing assessment of new Senegalese President L��opold Sedar Senghor���s political leadership.

Senghor had played a founding role in the Negritude movement, a literary and philosophical movement that emerged in Paris during the 1930s as a reaction against colonial racism, alienation, and the presumed superiority of western values. Negritude writers of the period composed poetry and prose celebrating Black experience���Senghor would later refer to this as a celebration of ���African ontology.��� For Fanon, however, Senghor���s brand of Negritude, which was turning out to be foundational to the political ideology and national aesthetic of the newly independent Senegalese state, seemed to essentialize Black identity, depoliticize Black experience, and mask a fair dose of hypocrisy. Fanon had watched as Senghor, an avowed Francophile, sided with France during the Algerian War; he had even gone so far as to oppose Algeria���s bid for independence before the UN. Even after Senegal���s independence, Senghor was working hard to maintain close ties between Senegal and France. In Fanon���s view, Senghor had failed to recognize that truly meaningful ���support for ���Negro-African��� culture and the cultural unity of Africa��� must be ���contingent on an unconditional support for the people���s liberation struggle.���

Just a few years before writing this scathing critique, however, it appears that Fanon had written a letter to Senghor, asking him for a job.

It was 1953. Senghor was serving in the Assembl��e Nationale Fran��aise as a Deputy for Senegal. Fanon had published Black Skin, White Masks the previous year. He had also just completed the battery of competitive examinations that made him eligible to serve as director of a psychiatric hospital in France or its colonies. According to Alice Cherki, who would later work alongside Fanon at Blida-Joinville in Algeria, there was no place Fanon had wanted to work more than Dakar, not only because of his desire to learn more about Black Africa, but because Dakar was, in Fanon���s mind, the perfect place ���to both practice psychiatry and to continue his study of societies in which the modern and the traditional exist side-by-side.��� The letter, however, was never answered. Senghor never sent a response.

In my recent book, An Impossible Inheritance: Postcolonial Psychiatry and the Work of Memory in a West African Clinic (published by University of California Press in 2019), I briefly take up Fanon���s letter to Senghor in order to engage in a bit of speculative history. Before I go further, though, I should say this: I���ve not seen the letter myself. I���m not entirely sure it still exists, or that it ever did. I���ve seen it mentioned in passing in several French and English sources, with the earliest reference coming from Peter Geismar���s 1971 book Fanon: The Revolutionary as Prophet. None of the authors, however, give any indication of having seen Fanon���s letter with their own eyes, and none cite the letter directly. So, the letter, which has come to be taken as fact, may be, or may not be. Still, I take its possibility as an invitation to think about the many forks in the road of history���the paths closed, blocked, or not taken, as well as the pasts, presents, and futures that these might have brought into being.

The mid-1950s was a time of enhanced welfare colonialism in Dakar. That is, during this period, France attempted to assert its legitimacy not by force but by reforming its colonial institutions and implementing new modernization projects that would showcase French ���beneficence��� and provide justification for its continued colonial presence. This was a space in which Senghor���s leadership flourished. Colonial psychiatry was also transformed during the period, leading to the closure of a carceral psychiatric facility called Cap Manuel (an annex of l���H��pital Le Dantec), and the establishment of the Fann Psychiatric Clinic (part of the Centre National Hospitalier Universitaire (CNHU) de Fann) in 1956. Under the directorship of French military psychiatrist and colonial liberal Henri Collomb, Fann became the site of a renowned project in transcultural psychiatry that would bridge the colonial era and the early post-independence years.

During the two decades (1959-1979) that he served as director of the clinic, Collomb and his colleagues at Fann (most of whom were also European) channeled their energy and resources into sociological and anthropological research, clinical practice, and theoretical inquiry. They also trained the first generation of Senegalese psychiatrists. L�����cole de Fann, or Fann School, as the group came to be called, positioned itself as a departure from colonial psychiatry. Taking a culturalist approach, the group challenged conventional western psychiatric and psychoanalytic models by attempting to establish a transcultural psychiatry that would, among other things, bring local ideas about madness and therapy into conversation with western approaches. For these reasons, Senghor touted the Fann Clinic as an exemplary institution of the nascent Senegalese state.

Collomb���s Fann embodied and symbolized Senghor���s new national aesthetic, rooted in Negritude, and contributed to his desired ���Civilization of the Universal.��� In 1980, Senghor wrote that the Fann Psychiatric Clinic brought to life a new kind of Senegalese modernity that merged the ���art of our ancestors��� with the ���discursive reason of Europe.��� One year earlier, Senghor (in an article in the journal Psychopathologie Africaine, ���Henri Collomb (1913-1979) Ou L���art de Mourir Aux Pr��jug��s���) had not only praised Collomb for being a ���Frenchman [who] knew how to kill the most firmly established prejudices��� but even went so far as to credit him for having made himself ���n��gre avec les n��gres��� or ���black amongst blacks,��� while working at Fann.

Fanon���s letter to Senghor���the very possibility of the letter���invites us to imagine how things might have turned out differently. What if Fanon had been hired in Dakar in 1953 to oversee the transition from Cap Manuel to the Fann Clinic? What if Fanon had directed the Fann Clinic toward a sustained investigation of the psychological effects of colonial subjugation, rather than toward the study of ���traditional��� or ���cultural��� (mainly Wolof and Lebu) interpretations of mental disorder and local therapeutic traditions, as Collomb had at Fann? What sort of political impact might Fanon and his work have made in Dakar during the 1950s and during the early independence era? Would Fanon have had Senghor���s ear, influenced him even? Would he have openly challenged Senghor���s desire to maintain close ties with France? ���Fanon���s Fann��� would have certainly been anathema to Senghor���s political objectives, and to the distinctly Senegalese style of modernity that Senghor promoted during the nation���s early years. Would Senghor have made space for Fanon���s critiques? As for Fanon, would his anticolonial critiques have developed along the same lines? What would have come of Blida-Joinville, of the FLN, and Fanon himself?

Another poignant question, for me at least, is this: If indeed there was a letter, why didn���t Senghor respond to Fanon? Why didn’t Senghor simply write back to Fanon and tell him that there was no position available for him in Dakar? Did Senghor already view Fanon as an adversary in 1953? Were Fanon���s politics already incompatible with Senghor���s vision of what Senegal���s future could and should look like? Perhaps it would have been an uncomfortable letter for Senghor to write, and so became the task that ended up being deferred indefinitely. Did Senghor mean to respond, and simply never get around to it? On Fanon���s end, how did he understand the silence? Did this make him resent Senghor, or lead him to question Senghor���s character and ambitions all the more? When Fanon invoked the ���Senegalese patriots��� in The Wretched of the Earth, those who lambasted Senghor for ���Africaniz[ing] the Europeans��� rather than Africanizing the top posts in the country, did he think back also to that unanswered letter? Did he think of Dr. Henri Collomb, of the Fann Clinic, and of the fate of post-colonial psychiatry in Senegal?

April 1, 2020

Addressing a pandemic on a continental level

Malaria Diagnostics and Control Center of Excellence microscopy training, Nigeria. Image credit Rick Scavetta via US Army Flickr CC.

When COVID-19 first hit western countries, health experts asked why it had not reached Africa despite its links to China and the continent���s fragile health systems. Reasons given included ���weak travel connections, effective border screening and travel restrictions, local climate effects, a lack of screening or a lack of reporting.��� However, the question that mattered was what will African countries do once the virus arrives considering their limited capacities to contain it?

Fast forward a few weeks, and there has been a spike in the number of cases in Africa. In response, major airlines like South African Airways have suspended all international flights and Ethiopian Airlines has canceled its flights to 80 international destinations. As African countries scramble to address the crisis by limiting the movement of their citizens through the closing of schools, cancelling of large gatherings, putting curfews in place, not allowing foreign nationals from certain high-risk countries to enter, among other protocols, the African Union (AU) and the Africa Center for Disease Control (Africa CDC) have stepped up to address the pandemic on a continental level.

The Africa CDC was established on April 13, 2015 and officially launched on January 31, 2017. The center has a number of strategic objectives which include the establishment of early warning and response surveillance platforms to address in a timely and effective manner health emergencies; support and/or conduct regional-and country-level hazard mapping and risk assessments for member states; and promote partnership and collaboration among member states to address emerging and endemic diseases and public health emergencies. As the AU continues to centralize its efforts, it was recently announced that Kenya has agreed to host the Africa CDC which, not surprisingly, will be funded by the Chinese government.

As an organization, the AU has highlighted the importance of partnerships for the Africa CDC. A central partnership is that with the World Health Organization (WHO). The AU and WHO signed an agreement in 2015, and building on previous pronouncements and commitments, have recently reaffirmed their shared mission to improve the health in Africa. The reaffirmation of their commitment comes after a high-level meeting of the AU Commission (AUC), the WHO, Africa CDC and its counterparts at the WHO Regional Office in Brazzaville, Congo. This relationship was further solidified with the signing of an agreement in 2019 that sought to ���reinvigorate, expand, and deepen��� the AU and WHO���s partnership in key areas. But, regardless of this support, the COVID-19 pandemic will serve as the Africa CDC���s ultimate test following the Ebola epidemic.

So far, a number of actions have been taken to address COVID-19. Starting in January, the Africa CDC called on member states to ���enhance their surveillance for severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) and to carefully review any unusual patterns of SARI or pneumonia cases��� and shared that it was ���working with laboratories in Member States to identify facilities that are able to receive and test specimens for novel coronavirus infection.��� Since then, regular outbreak briefs have been issued by the Center as the situation escalates. Following the first case announced in Egypt, the African Ministers of Health called an emergency meeting where the need to scale up laboratory diagnosis; enhance screening at entry points and surveillance; and strengthen infection prevention and control measures were emphasized. Other high-level meetings included an emergency meeting of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Ministers of Health which reiterated the Africa CDC���s key goals.

Handouts outlining what the virus is and associated risks along with a guideline on social distancing to limit the spread of the virus have been made publicly available. Most importantly, on March 20 the AU and Africa CDC published the Africa Joint Continental Strategy for COVID-19 Outbreak.

The AU and Africa CDC should be applauded for their transparency during this time. They have issued warnings to those who spread misinformation and are continuously tracking the number of countries affected, reported deaths, and recovery cases. Still, as the number of cases continue to rise and the global system remains in turmoil, the WHO���s Director General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has warned that ���Africa should prepare for the worst and prepare today.��� And, the question of whether the AU and the Africa CDC can tackle this crisis remains. Much attention has been placed on prevention but in this situation, as many countries have discovered, it is important to prepare for what happens when prevention is simply not enough.

In the back and in the side

A beach for Whites only near the integrated fishing village of Kalk Bay, not far from Capetown. January 1, 1970. Image credit UN Photo.

Each year on March 21 South Africa celebrates Human Rights Day, a national holiday. The date is no coincidence. On that date in 1960, apartheid police opened fire on a crowd gathered at Sharpeville (by the PAC) to protest apartheid Pass Laws. Sixty-nine people were killed and scores were wounded. Although the generally agreed upon totals are about 180 hurt that day in the shootings and subsequent chaos, the reality is that since people knew that going to hospital might result in their being identified as having been at Sharpeville, those who could avoided any official institution, hospitals and clinics included. Most of the victims had been shot in the back and in the side, indicating that they were running away and posed no danger whatsoever.

Sharpeville shocked the world and helped to accelerate the nascent global anti-apartheid movement. The apartheid system was no longer something the world could overlook, no longer a distant clash involving undifferentiated Africans in the face of a seemingly harsh but generally westernized white state. The National Party responded with draconian measures that ensured that any opposition to apartheid whatsoever could land people in prison, in exile, or worse. Sharpeville was inarguably the single most important event in bringing the realities of apartheid to the world���s consciousness, and the country���s status as a polecat of a nation was assured from that date forward.

But the rest of the world was still appalled mostly in the abstract. A sporting and cultural boycott would develop over the next quarter of a century, taking longer to grow roots in some parts of the world than others, just as at some times the criticism and scrutiny of South Africa���s National Party government was more intense than others. The global gaze tended to move on rather quickly, responding to events and human rights violations as they emerged. The United States and the UK, the English-speaking nations that could have made the most difference, shook their heads and said the right words but rarely followed up with real action. Meanwhile, opposition in South Africa became increasingly difficult with masses of activists operating in exile across the African continent and abroad or else imprisoned on Robben Island and elsewhere. There was always opposition���the myth that the anti-apartheid struggle became quiescent after 1960 has always been overstated���but it did not gain serious traction until the young people of Soweto collectively shouted ���Enough!��� in 1976.

But Sharpeville is not the only reason why March 21 is such an important, solemn, vital date in South African history. Almost unimaginably, on March 21 1981, exactly 25 years to the day after the events of Sharpeville, another horrible atrocity took place, the contours of which are gruesomely familiar.

On that day a funeral party was traveling between townships of Uitenhage, the industrial city outside of Port Elizabeth in the United Democratic Front (and therefore ANC) activist stronghold of the Eastern Cape���an area known most for automobile manufacturing (making it South Africa���s Detroit, in effect). Township funerals in the 1980s were most often political affairs and the one that day���honoring the deaths of young people killed in protests earlier in the month���was no different. The state had effectively made funeral processions of this sort illegal. Police showed up on the scene, the funeral marchers���defiant, but unarmed���stood their ground, and the police opened fire. Nearly a score lay dead, and an uncountable number of people were wounded, shot in the back and in the side, a grim echo of history. The horrors that day came to be known as the ���Langa Massacre.���

As long as we recognize that apartheid was definitionally a gross violation of civil rights and that the anti-apartheid opposition was motivated by a desire for human rights, broadly defined, it is perhaps easier to understand why March 21���the anniversary of Sharpeville, the anniversary of Langa���is so well chosen, and this national holiday so necessary.

March 31, 2020

The necropolitics of COVID-19

Downtown Johannesburg. Image credit Martyn Smith via Flickr CC.

The first sentence of Achille Mbembe���s essay ���Necropolitics��� (2003) begins with the assertion that ���the ultimate expression of sovereignty resides, to a large degree, in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die.��� The pandemic of COVID-19 appears to be a test of this contention. Though Mbembe���s argument for the emergence of a new form of politics centered on power over death, recently elaborated in a book of the same title, precedes this pandemic and has been applied primarily to the context of Africa, his concept provides a way of thinking through the politics of the current moment without resorting to conventional frameworks of left and right that have preoccupied discussions so far in the global north. Though this established set of politics has fundamentally shaped the infrastructural capacities of states to respond to the crisis, namely with neoliberal northern democracies such as Britain and the United States facing a distinct challenge in responding from years of austerity and the privatization of medical care, neither should the opportunity be lost to think differently about what is at stake. COVID-19 isn���t simply a medical or epidemiological crisis; it is a crisis of sovereignty.

The events of the past weeks and months cannot be completely recapitulated in this instance, but they can be characterized as an attempt to reclaim sovereignty. They reveal an emergent necropolitical landscape defined by states that have power over life and those with only power over death. A brief sketch of notifications, bans, and closures is useful in this regard: medical doctors in Wuhan, China, first report the existence of an unspecified virus in late December 2019; on January 23, 2020, the city of Wuhan with 11 million people is placed in a mandatory quarantine with additional travel restrictions in place for other cities in the Hubei province (totaling 57 million people); Italy declares a state of emergency eight days later on January 31; Italy imposes a national quarantine on March 9; a travel ban is put into place on March 11 by the Trump administration for travelers from Europe who are not US citizens; Spain announces a national quarantine on March 15; on the same day Germany implements new border restrictions; South Africa places a travel ban on foreign nationals from high-risk countries on March 18; Australia imposes a travel ban on foreign nationals on March 19, and so forth. What this brief summary outlines is a return to the most basic techniques of territorial control and state power���a politics of border restriction, community management, evening curfews, business closure, public dispersal, and empty streets. Citizens are further asked to self-discipline, in a Foucauldian fashion, through social distancing. The scale, speed, and global extent of these sovereign measures appear unprecedented.

To be clear, these measures should be pursued. In contrast to normative conditions when such methods would be seen as authoritarian, they are essential for sustaining life in this instance. Taken together, they constitute a reactionary version of necropolitics concerned with the management of life and death���to reduce disease proliferation, mortality numbers, and the rate of infection more generally. However, this reactionary stance equally indicates an unevenness of state capacity, that not all governments are able to respond equally. COVID-19 has highlighted a long-term failure among some states to sustain public health, to sustain life, through their commitment to neoliberal agendas to end state welfare in favor of privatization. The US and British governments are particularly egregious in governing on the basis of provisional schemes of affordable death through privatization and austerity measures, respectively. Prime Minister Boris Johnson���s initial proposal of ���herd immunity��� whereby COVID-19 is allowed to run its course through the UK population exemplifies this approach���a laissez-faire economic attitude applied to ordinary, vulnerable people in the context of a disease pandemic.

If COVID-19 has evinced a necropolitical approach to the lives of citizens and non-citizens that has remained latent until now, it is because this power over death contrasts with Mbembe���s original emphasis on the spectacle of war machines and suicide bombing, among other features. The necropower dynamics of COVID-19 and other epidemics, whether Ebola or HIV, are of slow violence. After decades of reduced infrastructure for medical care in many countries, whether through limited medical facilities in rural areas or through the sheer scarcity of life-saving hospital equipment witnessed now, national governments cannot guarantee or even administer life, except through the crudest forms of non-medical state control and cold violence against non-citizens as cited earlier. Approached differently, who gets to live and who gets to die is dependent on the goodwill, ability, and expertise of medical workers and others directly engaged with the situation. The power to dictate who may live has been outsourced and increasingly privatized, available only to those who can afford it.

A word on economy: if this necropolitical landscape has largely remained invisible until now, it is because the spectacle of global capitalism has also concealed this political dispensation. Even now, a brief glance at daily news headlines highlights how the sharp decline of the world economy and fears of capitalist recession have garnered equal attention to the disease itself, with global north solutions to the pandemic being envisioned in monetary terms in addition to the sovereign measures described earlier, whether through interest rate cuts by central banks, industry bailouts, or checks in the mail. The framing of the COVID-19 pandemic as an economic crisis is not only revealing of what priorities of sovereignty are at work, but it also indicates the limited tools of neoliberal state power in relation to matters of crisis and social disorder that do not relate directly to fiscal policy.

To be clear, policy measures that sustain the economic livelihoods of those hardest hit should be implemented. But such immediate measures should not distract from or appease the pursuit of long-term solutions to economic injustice. Indeed, the emergent economics of COVID-19 discloses in stark terms what we already know: the corrosive effects of neoliberal policies over economic life, whether through the erosion of social security programs, unemployment welfare, or public education, has reorganized sovereign state power away from securing life and sustaining well-being, to being solely concerned with the arbitration of death as seen now.

The necropolitics of COVID-19 consequently uncovers both the strengths and limits of Mbembe���s original intervention, as important as it was and still is. Published shortly after a millennial moment of reflection, with the 1994 Rwandan Genocide and civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone during the 1990s still in the conscience of many, his argument sought to provide an answer to the basic question as to why episodes of violence continued to afflict the African continent despite decades of independence, well after the violence of the colonial period. As an alternative to the structural argument of colonialism and its ethnic legacies as described by Mahmood Mamdani in Citizen and Subject (1996), Mbembe proposed the postcolonial consummation of a new kind of state regime that drew upon legacies of colonial biopolitics, but also departed from them by becoming more flagrant in assuming power over death���creating ���death worlds��� for citizens and non-citizens rather than the ���life worlds��� associated with more normative understandings of state sovereignty. What Mbembe could not easily foresee is how the state itself in a global context of neoliberal pressures has been re-instrumentalized in different ways, resulting in its marginalization vis-��-vis questions of life versus death. Being charged with capacity to dictate over life and death in a de facto way, as seen now during a time of epidemiological crisis, is not the same as pursuing it proactively as first described by Mbembe.

Nonetheless, the concept of necropolitics provides a different register for thinking through the dimensions of this unfolding political moment, in particular the situation of state failure in the global north, thus extending the uses of this concept beyond its origins. The crisis of sovereignty that COVID-19 has produced in the US, Britain, and other northern liberal democracies underscores the interpretive power this global south approach has for readdressing the claims and limits of state power. Though it is too early to be conclusive about either the immediate or long-term political effects of COVID-19, the geography of response that has surfaced underscores how states are attempting to recoup sovereign power over matters of public health.

Although the idea of necropolitics has never been strong as a rallying point for political solidarity, it can, as a critical method, contribute to a more progressive and radical political vision of what states could be like in the future���with the ambition and purpose of sustaining life, rather than solely, and belatedly, administering death.

Keep the phones on

South Africa Police. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

On the first morning of South Africa���s lockdown, a team of police officers and private security contractors with big assault rifles forced their way into our home in Johannesburg. They patted us down, searched the whole house, poured our beer into the fireplace and aggressively interrogated and berated us. When I tried to walk out of a narrowly crowded passageway, a security contractor stepped in front of me and said, ���I���m not police, I don���t have to abide by their rules, I���ll break your fucking face.��� I asked him why he would break my face. What I really wanted to ask is why he was wearing one of those balaclavas with the fascist-style print on the front. But then he put his hand on his weapon, so I did as he commanded.

Ten minutes earlier I had been in bed on my laptop. My brother had noticed commotion as the police gathered around a homeless man who lives on the pavement across from our home in Melville. Since the announcement of the lockdown, we had been concerned about the many people who live and/or work as informal traders, beggars, and car guards on what is usually a busy street. We knew only of a single press release that included one sentence about the government identifying ���temporary shelters that meet the necessary hygiene requirements��� for the homeless. But we also knew that there was hardly any information about what these shelters would look like or what life there would mean. We stood behind the burglar gate at the entrance of our two-bedroom home and watched quietly as the man desperately gathered what he could carry by hand, and ran off after being told that they would burn all his property if they found him on the street when they came back around. Then they turned their attention to us.

At first we thought it was a case of mistaken identity. One of them had pointed at my 20-year-old brother and said ���that���s the guy.��� About 10 of them walked over and demanded we unlock our gate and let them in. But, the more they searched and interrogated us the more confused I became. Suddenly three police officers were in my bedroom inspecting the anxiety medication on my desk, ���looking for drugs.��� They shouted at us for having beer, ���choosing to live like this,��� when we are so young. ���You don���t know how old I am,��� I whimpered. And why did they keep demanding to know who lives here after we explained again and again? Before they left, one of them said that they had just needed to know we weren���t running an illegal shebeen. As a young black person in Johannesburg, I���m fairly used to being profiled by law enforcement, but that didn���t explain why they stayed for so long or behaved so belligerently. After they left, I was glad I had not provoked them by mentioning that I work for a human rights law firm, or pointing out the laws they were breaking. I couldn���t stop wondering what would have happened if I had panicked or lost my temper.

One of the first friends I spoke to helped calm me down, then said, ���If they���re doing this in leafy Melville, imagine what they���re doing in the townships, informal settlements and packed low-income urban areas.��� Sure enough, anyone with the courage to open their social media account is immediately flooded with countless recordings and narrations of senseless violence from police, soldiers, and even private security. This was all happening on day one of a lockdown that had only been announced three days earlier. They���re riding around the country hunting the poor and vulnerable. Teargas, guns, water-cannons, brutal beatings and a wide array of innovative tactics to taunt and humiliate. It made our experience feel insignificant, but it also made the senselessness of it all make sense.

But why would they do this? Well, this is what South African police and private security companies do. I suppose they think it���s their job to go around the country heavy-handedly making sure that people are in their homes scared. And who could blame them? After all, we���ve heard the militaristic rhetoric coming from our leaders. It took me nearly five years of living at a public university residence to get it. Every time politicians, powerful bureaucrats, and rich people got nervous they would send the police to teargas us, chase us down, and shoot at us. As students we���d peek out from under our beds and scream ���we live here!��� As though, if only we could differentiate ourselves from the troublesome protestors (or the poor and homeless) and establish our status as innocent bystanders that might make us safe. In that same vein, we call on more brutality against whoever the bureaucrats tell us the bad guys are. But the problem with brutality is that it is brute���it doesn���t recognize bystanders, and it has no understanding of innocence. I tweeted our Friday home invasion experience immediately (I tweet everything immediately), and by the end of the day I was shocked at the number of strangers angry with me because they assumed I was lying or exaggerating for attention, or that we had surely done something to provoke the incident, or simply expressing pleasure at what they decided was a small price to pay for an increase in their safety.

I do not feel safer.

The people you would expect to be defending civil liberties are too busy celebrating false positives. Or embracing petty authoritarian ideas such as embracing alcohol prohibition and jailing people for fake news. Of course the army found some lawbreakers in their nation-wide raid. There was always a public health crisis in overcrowded townships. Stop celebrating action just because it is decisive. Decisive action mitigates some risks. But what exactly are we willing to call victory?

The independent police watch-dog (IPID) had encouragingly released ���stand-by��� numbers to further support the organization during the lockdown. What was unclear was whether this was IPID institutionalizing an ���emergency��� hotline available to the public to report cases of police assault during the lockdown. My friends and I repeatedly attempted to call the Gauteng number which kept going to voicemail because the mailbox was full. As it turns out, these stand-by numbers do not change the status quo of accessing IPID as the public. We are still expected to file a charge at a police station, wait to see if our charge goes anywhere, and if not, then escalate to IPID. We are expected to do this during lockdown when police are exercising their ramped-up powers to brutalize us for leaving our homes (or standing inside it).

At the end of the first day of lockdown, when Minister of Police, Bheki Cele, was asked about the risks of police using excessive force, he responded that the police were still being ���very kind���, and added after a derisive laugh, ���wait until you see more force.��� The Financial Times spoke to a SAPS spokesperson about my experience and untold worse. The response they were met with assured them that nothing would go wrong if people simply complied with the regulations. By Monday morning, police raids had reportedly killed at least two innocent people. We have also discovered that the ombudsman responsible for military misconduct is closed for the 21-day lockdown period. We are living at the mercy of the security state and the government has turned the phones off.

We���re all afraid. We have been for weeks. But who are we protecting and from what?

Perhaps COVID-19 presents an unprecedented threat, but a campaign attempting to grind defenseless people into dust does not guarantee success. If there���s anything South Africans should have a knowledge of, it���s that people never grind that fine.

March 30, 2020

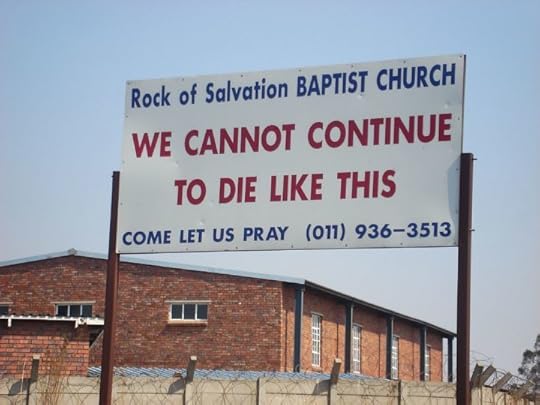

Pentecostal promise and a South African dream deferred

Image credit Babak Fakhamzadeh via Flickr CC.

The church had no outward sign to indicate it was a place of worship. As I drove up on a hot summer afternoon, the only thing guiding me was a set of GPS coordinates the pastor had sent me ahead of time. I had traveled from Johannesburg to one of the city���s outlying townships, marginal lands settled under apartheid to house black urban laborers that remain de facto segregated today. After greeting me and sharing a cup of tea in the unadorned chapel erected adjacent to his home, Pastor Mabuza told me of the challenges facing young people trying to grow up in a broken community: poverty, alcoholism, and a lack of social support that the years of post-apartheid governance has failed to reverse. However, what preoccupied him on a daily basis as he preached in the township���not far from where he grew up���was a frightful specter I came to hear described to me again and again: the ���prosperity gospel.��� He insisted that these prevailing Pentecostal or charismatic leaders around him, influenced by heretical teachings from abroad, were engaging in ���false preaching��� by manipulating Old Testament passages to promise their followers material riches on earth if they are faithful and loyal enough. Their churches may have been much flashier than his modest setup, but they harbored dangers behind a shiny facade.

Indeed, my time with Christians in South Africa was punctuated with whispers of likewise sinister threats about nefarious characters who take advantage of people���s often-desperate search for deliverance. The arrest of Prophet Shepherd Bushiri, the Malawian head of a South African charismatic church, on fraud charges in 2019 ignited public anxiety over the ethics and legitimacy of these preachers, who have dominated the religious landscape not just in South Africa but across the continent. Even when the bona fides of these pastors are not directly in question, secular media cast suspicion at the devotional fervor people exhibit toward them, as when three of Bushiri���s followers died in a stampede at one of his services. As Pastor Mabuza argued, blind devotion to charismatic figures misguided South Africans to ingest harmful substances like Doom, a popular pesticide, in a parallel to American snake handling or poison-taking, itself an expression of Pentecostalism across the Atlantic. Stories of pastors who abuse the trust placed in them mingle with fears of ���cultish��� worship of powerful men and women.

Placed in a broader context, it is not long before these worldly concerns meld into those of a supernatural order: rumors of occult powers and potent witchcraft brought in from afar. Who in South Africa has not seen advertisements for an exceptionally powerful sangoma or healer visiting from up north? Why do people in Africa���across cultural difference and the color bar���reach out to new avenues through which to access hidden possibilities? Black and white South Africans I spoke to, including both professed Christians and non-Christians, recounted fears of witchcraft entering the country from outside its borders at the same time as they expressed fascination with the powers these spiritual forces might conjure. Although at times voiced by different people, these widespread concerns move between material exploitation and otherworldly danger, perhaps blurring the lines between them.

The meteoric rise of Pentecostal Christianity around the globe, including in Africa, has motivated social scientists to put forward various models to make sense of it. Whether seen as a political critique of existing modes of capitalist distribution, a resonance with existing materialist practices that mix African traditions and Abrahamic frameworks, or a way to cope with the exigencies of urban life, these popular and relatively ecstatic forms of religious practice can be approached through their ability to speak to deep-seated socio-historical phenomena. Just as Pentecostalism and witchcraft have received such close scrutiny, so too should those���like Pastor Mabuza���who position themselves against the charismatics be understood as participating in a broader socio-political network. What are these Christians saying that reflects the conditions of living in contemporary South Africa, and perhaps the world?

In short, they, like their Pentecostal counterparts, are figuring out how to confront widespread suffering. Despite socially and theologically divergent responses to the problem, Pentecostals and non-charismatic Christians agree that all is not well in South Africa. Things have not been going right for some time, and something (or someone) is to blame, not necessarily in the sense of a scapegoat, but there is a need to explain why what liberation promised in the 1990s has not materialized. Take Pastor Mabuza���s concerns with prosperity preachers in the township. Although his criticism might be read as disdain for ���improper��� forms of Christianity or (more cynically) as hostility toward his competitors on the religious landscape, it also constitutes an answer to the age-old question of theodicy: from a Christian perspective, how to explain why an omnipotent and benevolent God allows bad things to happen.

For Mabuza, preaching focused on material prosperity ignores the true biblical message of spiritual salvation and, as a sinful misreading, deceives people into the false hope of escaping poverty. Yet his theodicy is not an abstract, universal theodicy, but one emerging from and inextricably bound to a place and time. With the rise of disaffection with the results of post- apartheid reconciliation, anxieties about crime and social disorder, and a resulting pervasive suspicion, it is little wonder that South Africans target not only the demons and witches who terrorize worshippers, but also the charismatic leaders themselves, who are imagined to extract value in the form of tithes and empty promises. No one is safe from scrutiny, but that���s the point.

In the words of Langston Hughes, a ���dream deferred��� might ���dry up like a raisin in the sun,��� or perhaps it ���sags like a heavy load.��� The poet at last asks, ���Or does it explode?��� For South Africans 25 years after the supposed transition to democracy, the dream of a racially just nation has certainly been ���deferred,��� if not precluded entirely. Economic prosperity continues to accrue only to a sliver of the population, while the majority face increasing demands of poverty, joblessness, and a lack of societal transformation. In some ways, this story echoes contemporary conditions of societal angst not exclusive to this setting. Caught in a web of barriers to living the ���good life,��� South Africans turn, as do people the world over, to spiritual promises of deliverance in the absence of political or earthly ones, even if those supernatural promises turn out to be empty at times. It is unclear what the detritus of the ���explosion��� of a dream deferred might look like in a post-apartheid context, but religious critics, such as Pastor Mabuza, remind us that debates over religious orthodoxy���far from existing in their own hermetically sealed, esoteric domain���can be a marker of much deeper social discontent than they may otherwise appear.

Rouge Imp��ratrice

Boulevard Krim Belkacem, Algiers, 2010. Image credit John Perivolaris via Flickr CC.

Franco-Cameroonian writer L��onora Miano published Rouge Imp��ratrice in August 2019 (literal translation: Red Empress). Part romance novel and part geopolitical essay set in the year 2124, Rouge Imp��ratrice envisions a prosperous and united African federation no longer divided by colonial-era borders or neocolonial interventions: the unified Katiopa (Katiopa unifi��). The novel is largely driven by the passionate and controversial relationship between Ilunga, Katiopa���s head of state, and Boya, an academic���a relationship that brings to light cracks in the Katiopian project as Boya encourages Ilunga to diverge politically from the Alliance that governs Katiopa.

Shortlisted for a French literary prize (the Prix Goncourt), Miano���s novel received quiet acclaim in France. But it has yet to make its mark in global circles���perhaps due to its current unavailability in other languages. Yet the cultural, social, and political projects at the heart of the unified Katiopa resonate with current pan-African debates and social movements, making Rouge Imp��ratrice a timely contribution by a francophone Afropean writer.

The utopian ideal of a unified Katiopa is challenged by the minority presence of the Fulasi (French) population, known as ���the Stricken��� (Sinistr��s). The Sinistr��s are descendants of French immigrants who, troubled by the rise in immigration and the shifting cultural and racial landscape in Pongo (Europe) in the early 2000s, left their home country and settled in Katiopa, hoping to connect with an imagined lingering colonial influence. As the unified Katiopa came into being���as colonial borders were destroyed, international presence expelled, and a pan-African federation constructed���these Sinistr��s were permitted to remain.

The presence of the Sinistr��s is complex. They have failed to integrate themselves but have not caused any active harm to the unified Katiopa. Yet the key debate punctuating the novel is whether their very presence is harmful. As the unified Katiopa has built itself as a proud, diverse, pluralistic, and nationalist entity, is the very existence of a minority white population a threat to Katiopa���s identity?

Rouge Imp��ratrice is a novel about imaginaries���about the possibility of imagining a future African continent and a future pan-African identity. It is not a novel about neocolonial forces retreating, but about Katiopans ejecting these forces and claiming territorial, cultural, and political sovereignty. Rouge Imp��ratrice challenges us to ask: can Africa ever fully move away from the legacies of colonialism, and if so, through what mechanisms? What might it take to create a unified pan-African structure, freed from foreign interventions and influence, financially independent and prosperous?

In a video interview with independent French news outlet M��diapart, Miano explains that ���the great challenge of sub-Saharan Africa today is really to reinvent itself, and to accept perhaps to not have a model anywhere. And I find that very exciting���maybe because I am an artist���to tell ourselves that maybe, after all, the world is unfinished and that we can bring something to it, that the world as it is is not static forever, that we can create something new. We can propose a different civilization.��� Rouge Imp��ratrice embodies these ideas, this desire to craft a vision for an innovative space (both physical and ideological) and to put that vision into practice.

Rouge Imp��ratrice is also a novel about France.

Like all utopian inventions, it is rooted in the present while challenging us to look beyond it. Implicit throughout the novel is the reality of present-day French nationalism, obsessed with the idea of an ���African invasion.��� Miano challenges French audiences to flip their gaze and reflect upon an alternative scenario, one where white French populations in a future Africa are perceived as invasive, where they become the problem to a unified African federation and identity.

Perhaps the novel is also hinting to the increasing rise of anti-French sentiment in francophone West Africa, a response to France���s neocolonial interventions, particularly military and financial. Are these movements the beginning of the end of France���s neocolonial presence in Africa���and could they be setting the stage for a future Katiopa?

In the aforementioned video interview with M��diapart, Miano explains how her novel aims to go beyond decolonial and postcolonial logic, breaking away from the expectation that writing about Africa must always respond to colonialism and its legacies. The novel seeks a space where identities and politics are liberated from the divisive legacies of colonialism and the constant backdrop of neocolonialism. Yet the very identity of a unified Katiopa is challenged by the Fulasi presence, which allows colonial legacies to nonetheless seep into a political imaginary supposedly entirely freed from the colonial ills it initially sought to eradicate.

I want to conclude by briefly emphasizing the importance of the love story at the center of Rouge Imp��ratrice. Ilunga and Boya are not just vehicles through which Miano explores complex social and political questions. Sensual and romantic scenes are at the novel���s core. Miano emphasizes that ���Africa, too, has the right to embody love.��� Committed to exploring intimacy among sub-Saharan and afro-descendant populations throughout her literary career, Miano makes clear that a unified Katiopa is defined not solely by a flourishing political and social vision. Love and intimacy are just as integral to the Katiopan imaginary.

March 29, 2020

The People vs 4G internet and other corona stories from Kenya

SDI, via Flickr CC.

On February 28, two weeks after Nigeria confirmed its first COVID-19 case, and one week after South Africa did the same, our Cabinet Secretary for Health, Mutahi Kagwe, appeared on TV to announce Kenya���s first confirmed patient with the virus on March 13. Since then, barely two weeks later, we are at 31 cases with one recovery and one fatality.

From the outset, the government���s response was seemingly very uncoordinated, and committed what the economist David Ndii refers to as ���fatal errors.��� That there appeared to be no quarantine plans for those who came from abroad (returnees are taken to either Mbagathi hospital, another government facility, or can pay up to US$125 a day for two weeks to ���self-quarantine��� in a hotel where they are not separated from other travelers), the fact that there are not enough ICU beds, or that the national Corona hotlines don���t work consistently, are evidence for the bungled nature of the formal COVID-19 response locally.

Since March 13, the most common statements from the government are: ���stay at home��� ���work from home��� and ���social distance.��� Coupled with the much PR-hyped declaration by the President on March 23 that Kenya has allowed Google loon balloons to provide 4G internet at this time that we should all be working from home (and it is not even free!), these interventions have (re)emphasized to many that Uhuru Kenyatta is just the ���president for the rich.���

First, very few Kenyans have the kind of jobs where they can ���work from home���: many are workers in the sectors that pay wages daily — what we call mjengo (construction), food sellers, hawkers, industrial zone workers, etc. And, in addition, principally in urban areas, many are unable to engage in social distancing since they live in densely populated settlements. What���s more, the enduring neoliberal governance of our country has privatized the provision of water, effectively denying this basic right to many. Therefore, the appeals to ���wash hands often��� or ���buy sanitizers��� don���t sit well with the majority of folks who don���t have and can���t afford either water or sanitizers.

On these accounts, forcing people to ���stay at home��� without delivering people-centred economic initiatives is only going to propel what the Social Justice Centre Working Group (SJCWG), a collective of 30 community centres in Kenya, called ���financial disability and starvation.��� This is why activists like Gacheke Gachihi, speaking on a Daraja Press podcast, called for a rethinking of the impending lockdown, and the innovation of corona interventions locally so that we are not just ���copy pasting solutions from Europe.���

Following the 4G internet announcement on March 23, Kenyans, not known to hide when they have taken offense, started a hashtag called #WaterAndFoodFirst on Twitter. And Boda Boda motorbike transport operators, firmly supported by the majority, stated that ���we wanted Uhuru to tell us about food and coronavirus and not about balloons.���

But, though the 500 hand washing stations that were set up around Nairobi on March 21, and a number of which were vandalized and had taps stolen two days later, may make us question how worried Kenyans are, rest assured, that from Eldoret to Nairobi the restrictions brought about by COVID-19 have caused pain.

Basic commodity prices still remain the same, and the cost of public transport has doubled as operators have sought to make up the deficit rendered by the directive that only a minimal amount of passengers should be allowed to be on board at any one time.

Ultimately, the economic conditions of Kenyans is in sharp decline, and, perhaps, in a small bid to hear their plea, two days after the 4G internet announcement, Kenyatta announced a ���stimulus package,��� which, among other interventions cut value added tax (VAT) from 16% to 14% effective April 1. This package also implements tax cuts for people earning up to 24,000 Kenya Shillings (roughly $240) a month, and facilitates the recruitment of additional health workers.

Uhuru, his Deputy and other public servants have also subsequently announced that they will take pay cuts.

Though the package will bring some reprieve, the proposed tax cuts, for example, target those who have fixed employment contracts, while a large section of Kenyans earn daily wages, if at all, with no fixed terms. It also does not help those who have lost their jobs, nor recognize the real cost of food for every Kenyan who is dealing with a drop in the value of the shilling.

The government has not yet imposed a total lockdown, though it says this is ���an option.��� Some commentators, including former governor William Kabogo, call for a lockdown with sufficient rent and wage support for all. Currently, all but essential movement is restricted, and a 7pm-5am curfew would be in place effective Friday, March 27.

Beyond these government interventions, unsatisfactory to many, Kenyans are seeking to help each other where they can, and as they have always done: communities have come together to make sure the most vulnerable, like the sick and elderly, have access to food and water. And even in spaces where water has to be bought, activists have ensured that hand washing posts have been established in as many places as possible.

Though Africa is behind the curve of infections at the moment, will these everyday forms of solidarity cushion us when infections peak? In the same Daraja Press podcast, Gacheke Gachihi argues that this crisis has further emphasized the neglect of the poor by the government, and is therefore ���a wake up call that we are on our own.��� For those who ���cannot just stay at home and use Google��� he says, we need to continue building ���a social justice movement.���

Certainly, that may be all that is possible, the only option, for the Kenyans who can���t enjoy Google loon internet balloons.���

March 28, 2020

Reading List: T.J. Tallie

Stop.Time.Photo, via Flickr.com Creative Commons.

In the months since my book, Queering Colonial Natal: Indigeneity and the Violence of Belonging came out, I���ve been reading a wide and eclectic mix of books as I try, like everyone else, to make sense of what���s happening in 2020 and beyond.

First, I���ve had a chance to return to Jill Kelly���s powerful and engaging history of Zulu identity and authority, To Swim with Crocodiles: Land, Violence, and Belonging in South Africa, 1800-1996. Kelly���s book travels from the late 1700s to the post-apartheid period, tracing how the Zulu concept of ukukhonza, or chiefly deference, developed and shifted to changing contexts. For Kelly, African men and women depended upon ���both the physical security endangered in times of violence and the social security produced by the order of homesteads and chiefdoms that enabled familial and community well-being ��� New ways of seeing land and polities did not erase the old, but came to exist alongside them.��� Ukukhonza existed as a social concept that bound people together before the rise of the Zulu empire, and it continued to evolve after the rise of Shaka and the later establishment of the British and South African states. The term was capacious and flexible enough to encompass a wide variety of social relationships, binding people in new and complicated ways during moments of crisis. Kelly examines the uses of this chiefly concept in a close study of the region surrounding KwaZulu-Natal���s Table Mountain, particularly around the village of Manqongqo, where we both studied isiZulu as graduate students. To Swim with Crocodiles is more than just a well-documented history; it���s also a testament to African cultural survival and adaptation over centuries.

As someone working on questions of blackness, indigeneity, and belonging, I absolutely needed Tiffany Lethabo King���s new book The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies; simultaneously haunting and arresting, beautiful and urgent. In it, King argues for a critical new formation in understanding black studies and native studies simultaneously and arrives at a powerful geologic metaphor. King offers:

the space of the shoal as simultaneously land and sea to fracture this notion that Black Diaspora studies is overdetermined by rootlessness and only metaphorized by water and to disrupt the idea that Indigenous studies is solely rooted and fixed in imaginaries of land as territory ��� The shoal creates a rupture and at the same time opens up analytical possibilities for thinking about Blackness as exceeding the metaphors and analytics of water and for thinking of Indigeneity as exceeding the symbol and analytic of land.

What would it mean to think of the fruitful and painful intersections of nativeness and blackness in North America? How is black racial terror simultaneous with and shaped by and through anti-indigenous genocide? King deftly explores these questions in stunning and meticulous prose, offering more than critical theory, but an arresting vision for understanding the many violences that shape our contemporary world.

Continuing on that theme, I���m still fascinated by and re-reading Michael Twitty���s The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South. Twitty is a queer, black Jewish culinary historian who wants to tell a new history of the American South, particularly through the brutal intimacies of food cooked in plantation kitchens. ���The Old South is a forgotten Little Africa but nobody speaks of it that way,��� offers Twitty by way of introduction. Part cookbook, part memoir, part culinary history of enslavement, The Cooking Gene explores what blackness���and specifically Africa���has offered the emerging settler American nation. Twitty doesn���t shy away from the daily violence of the plantation and the dehumanizing erasure of black labor and genius in everything from music to barbecue to agriculture. But his prose also offers a constant and gentle exploration of these complicated intersections of history, violence, and survival. From lovingly describing the process of cooking a morning meal to the uncomfortable encounter with an ancestor���s grave at a former planation, Twitty offers a spellbinding journey, every step of the way.

Finally, two very different novels sit on my bedside table at this moment, both offering something necessary for our heartbreaking and confusing year. First up is Kira Jane Buxton���s surreal and affecting Hollow Kingdom, which tells the story of a human apocalypse from the perspective of the animals left behind. Buxton���s primary narrator is a crow named S.T. raised from an early age around humans and who is trying to make sense of the continued destruction of the world he loves. Hollow Kingdom rises above the easy genre of ���zombie apocalypse��� by widening our perspective beyond humans to include how the rest of the planet puzzles over and struggles to comprehend the vanishing of such a terrifyingly destructive and dizzyingly creative force in the world. It���s well worth the time.

Of course, no list of reads for this year would be complete without returning to Octavia Butler���s prescient, horrifying, and deeply hopeful novel The Parable of the Talents. Butler���s story is set in a climate apocalyptic California, as a deeply privatized American state has splintered beyond repair. In the face of a deeply declining country, the populace turns to a cynical religious conman who promises to ���make America great��� (the book was published nearly two decades before Trump popularized the slogan). Butler dedicates considerable pages to considering just how and why people afraid of the destruction of their privileged hold on the world would embrace an openly religious fundamentalist fascism, but that is not the core of the book. Instead, the novel focuses on Lauren Olamina, a black woman with a radical vision of the future she titles ���Earthseed.��� The Parable of the Talents is less a story of cruel contemporary authoritarianism and more of a focus on the transformative power of hope, renewal, and change.

As Earthseed teaches, ���Here we are���Energy, Mass, Life, Shaping life, Mind, Shaping Mind, God, Shaping God. Consider���We are born Not with purpose, But with potential.��� As we���re surrounded by fear, panic and uncertainty, such potential is worth holding onto now more than ever.

March 26, 2020

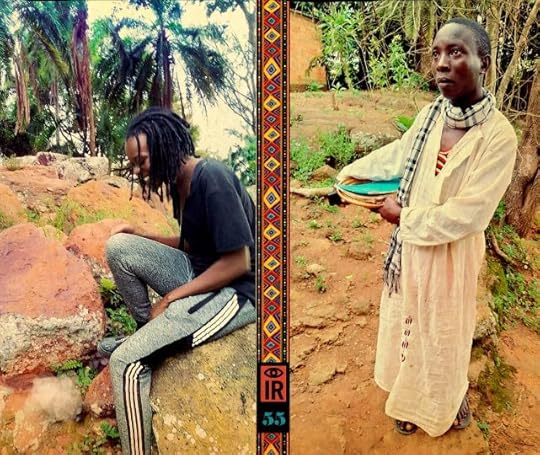

African political techno

Indigenous Resistance mini-album cover. Design credit Dubzaine.

In the African futuristic track ���Wire Cutter��� by Sankara Future Dub Resurgence (SFDR), a group of musicians from Uganda inspired by the philosophy of the Burkina Faso revolutionary, Thomas Sankara, sing: ���Yes I seek to inspire / Yes I move with guile / Underground Resistance my style.���

With their love of dub and experimental music, they decided to create a futuristic style of music that draws equally on ancient African knowledge. The video for ���Wire Cutter��� video was filmed in Kampala, Uganda���s capital. It���s a live recording, but it���s also more than that. ���Wire Cutter��� is a piece that calls viewers to look closely and notice the images layered throughout the performance space. It���s also important to take note of the space���the one and only Dub Museum.

For example, when the lyrics mentioned above are heard in the video, the camera zooms in on images of Detroit techno artists Underground Resistance (UR). The shot ends with a close-up of Cornelius Harris, a key member of the group. At another point in the track, where the lyrics state ���We only fear fear itself, we only fear the collapse of the imagination,��� an image of UR���s founder, Mad Mike, is foregrounded.

Images of other experimental musicians and socially conscious visionaries are also featured, such as Laraaji, Turiya Alice Coltrane, Cedric ���Im��� Brooks, and Audre Lorde. They coexist alongside photographs of ancestral shrines in Uganda, as well as Zar spiritual trance ceremonies in Ethiopia. Lastly, there is a special wall devoted to the West Papua liberation struggle.

The sonic anchor of ���Wire Cutter��� is as much about sound as it is about dub poetry and powerful visuals. Driving this narrative is an assemblage of minimalistic electronic noise and non-metric rhythms generated by Dhangsha. In between these sounds, one hears deliberate moments of deep meditative silence, raw and at times distorted African dub poetry vocals, and djembe-driven, percussive grooves created by SFDR.

When the djembe rises to the surface, it reveals acoustic drum patterns that are actually hand -to-skin translations of Dhangsha���s digital rhythms. This is more than simply a moment of ���fusion;��� it signals the completion of a musical cycle.

When enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to the Americas, they brought their music with them. During the course of almost 500 years, this music continued to change in response to the reality of violent oppression and social survival. For future generations, this music symbolized���and continues to symbolize���resistance, creativity, and the triumph of the human spirit.

The evolution of techno from within Detroit���s African-American community is an overlooked chapter in that story of resistance, but in ���Wire Cutter,��� a critical exchange takes place as this music returns to the African continent and is reunited with a group of African youth who naturally embrace their ancestral traditions, while looking clearly to the future with outernational vision.

Aniruddha Das, the creative force behind Dhangsha, explains this cycle further:

The flow of the same energy between Detroit and Uganda [gets] filtered by the diaspora currently based in Europe, [transforming] pain and searching and yearning into positive vibrations and frequencies and texts of resistance… Another SFDR track, “Two Thousand Seasons Dub“, really shows how Detroit vibes���specifically UR���are echoing now in Uganda to create an African political techno. It is also lyrically influenced by the anti-colonialism tome by Ayi Kwei Armah.

The first time I watched ���Wire Cutter��� and ���Perfect Black Light��� (also by SFDR), it felt like a work of science fiction, especially because of the setting. When you look at the settings of the videos, you see a community of people at the outer limits. They���re not connected to any scene because they are their own scene, and unlike the club scenes that most of us frequent, this is a scene that people actually live in. It���s not self-conscious. You can���t be self-conscious when you���re trying to get on with the routines of everyday life.

The sci-fi sense also comes from the fact that these are African people in settings that are neither metropolitan or rural. Again, they���re at the outer limits where no one���no tourists, that is���are likely to go. And here they are using technology, experimenting with it, having fun, being creative, and it���s obviously for themselves, and not for some festival-size crowd or even for the internet. But like I said: outer limits + technology = creativity. And that���s Afro-futurism.

Re wild

Re define

Re design

Thoughts from a Black anarchist mind

��� ���Perfect Black Light��� (Sankofa Future Dub Resurgence)

The world of the Dub Museum, as captured in these two videos, is far removed from the downtown nightclubs, EDM festivals, and other places we usually associate with underground and experimental electronic music. These videos take you deep into the Kireka neighborhood in Kampala, the location where the SFDR music was recorded. This is a neighborhood with a food market, corner shops, plots where people plant food, a school for the children. A simple place of day-to-day living, and of struggle and survival in this African city.

The manner in which the Dub Museum was created���independently, and autonomous of NGO or political party support���certainly makes it flow with the ideals of Thomas Sankara and beyond. Filmmaker Eyi Safi, in the liner notes to a Sankara Future Dub Resurgence album, describes a typical day at the Dub Museum:

In one corner of the yard people were sitting around a fire that was going, listening to the music that was playing and chatting among themselves. Coming from the speakers one heard the Sankara Future Dub Resurgence track, then a roots reggae track by Gregory Isaacs was put on and this was followed by a heavy instrumental dub track by Augustus Pablo and then experimental beatless noise track from the Dhangsha cassette ���Future Tense,��� and throughout the evening this musical cycle would be repeated. Different musical styles from roots to experimental noise music played as a soundtrack to daily living as people prepared and cooked food, laughed, chatted and most importantly enjoyed music. Throughout the afternoon and night, various Dhangsha tracks were played ���

During the rehearsals for the filming of the SFDR video, a beautiful scene was witnessed in the Dub Museum yard. An eight-year-old girl, whose mother makes and sells banana pancakes in the space adjoining the yard, was watching rehearsals. People said that she came to rehearsals every day because she just loved the music. The mix for ���Perfect Black Light��� was put on the sound system speakers that were set up in the yard. Out of the corner of our eye, we saw the little girl start dancing in perfect timing to this experimental music track! Whereas it might be possible that many adults would have difficulty and hesitancy on how to dance to this track, she had no such problem. She found her groove in the music and she was dancing, raptured in own journey with the track.

Not only had the music returned back to the African continent, but also it was now passed to the next generation or, as the Ugandan musicians say in the track “Perfect Black Light”:

In perfect black light

We see the dub seedlings grow

Apachita generation

the next generation

Jah know

Prasad Bidaye would like to acknowledge the dub guidance and resources of the Indigenous Resistance collective.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers