Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 189

February 20, 2020

Decolonization���s borders

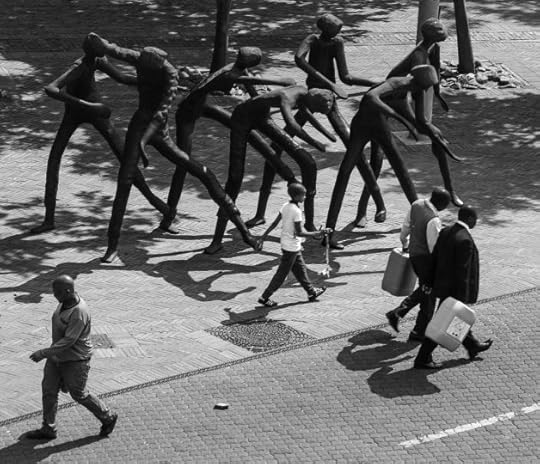

Pretoria Market. Image credit Herve Jakubowicz via Flickr CC.

Echoing global moves to restrict access to asylum, the South African government has recently limited the right of asylum seekers to work, has narrowed the grounds for claiming asylum, and most controversially, has all but silenced refugees��� political voice. Already prevented from voting in South African elections, refugees will now risk losing their status if they vote or campaign for change in their countries of origin. This holds even for those claiming for asylum on grounds of political activism. Should they try it, they would be at risk for speaking up about conditions in South Africa too.

This decision is about far more than the rights of South Africa���s substantial population of refugees and asylum seekers. South Africa���s Constitution promises the country to “all who live in it.” Since the end of apartheid, this has meant legally recognizing the fundamental rights of everyone. Even if constitutional protections have translated poorly into reality for foreigners and South Africans, the principle was sound. Recent changes to the Refugees Act are an assault on this constitutional universalism. What were once guaranteed protections for non-nationals now become privileges.

More alarming is that the government has effectively transformed the Constitution by arbitrary order and regulation, not open parliamentary debate or amendments. Most of these changes do not appear in the amended Refugees Act itself, but in accompanying regulations not vetted through normal legislative amendment process. If left unchallenged, the government is likely to continue reshaping the constitutional landscape in additional areas.

The recent restrictions on refugees���and the limited protests against them���reflect the degree to which many South Africans see ���xenophobia��� as a legitimate hate. Few see it as akin to the racism and exclusion so many South Africans continue to suffer. Ironically, many claiming to ���decolonize��� the country���s institutions often reinforce its colonial borders. Many accept opposition leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi���s proposition from all those years ago: that immigration spells the end to positive transformation. Rather than condemn the exclusion, citizens and politicians embrace it.

Even when South Africa was deporting hundreds of thousands a year in the early 2000s, citizens took to the streets calling for the rest to go. The consequences have been death or displacement for thousands of non-nationals in repeated bouts of ���xenophobic violence.���

As the ruling African National Congress has faced declining public support, it increasingly relies on immigration to rally the masses. Drawing isolationist language from the streets and political margins, it calls for closing borders, workplaces, and public services to non-nationals. Such appeals featured prominently in the 2019 election campaigns.

Perhaps most worrying is what these moves reveal about the nature of activism and commitment to constitutionalism among South Africa���s civil society. Only a small group of activists and officials decry these moves. Some critics argue that they align South Africa with Donald Trump���s America or the European Union. While the US and EU might approve, this is not their doing. Rather, it reflects the manifestation of an isolationist tendency baked in to South Africa���s post-apartheid politics. Most South Africans have responded to these changes with deafening silence or quiet nods of approval.

Pro-refugee activism in South Africa continues to play into these hostilities, as it does elsewhere in the world. By making migrants the center of action, middle-class activists alienate the poor and draw lines in the township soil between groups who have similar struggles with economic marginalization, hostile policing, and insecurity. Yet, activists continue to highlight the vulnerability of refugees and migrants alone. More damagingly, they speak of an obligation to assist. This is not just a legal duty outlined by the Constitution and the Refugees Act. Rather, they argue South Africa has a responsibility to protect people from countries who once sheltered South African exiles or mobilized against apartheid. Others appeal to pan-Africanist ideals.

An ethics of reciprocity has its place, but also severe limits. For one, it says nothing about people from countries that did little for South Africa, or for those from other continents. Moreover, neither reciprocity nor pan-Africanism have much traction with the “born-frees”: people who know little about the anti-apartheid struggle, but recognize that not much has changed for their families since its end. They can vote, but jobs are scarce. Many feel aggrieved and marginalized. Among this group, appeals to hospitality and reciprocity gain no traction. Many across Africa support Trump���s nationalism despite his evident racism. Pro-refugee campaigns naturalize the line between citizen and foreigner and reinforce the idea that we must care for others even as we struggle to make ends meet.

The politics of exclusion behind South Africa���s new restrictions have evidently offered short-term political gains for some. Other leaders now seek similar benefits, but elements of these proposals are almost undeniably unconstitutional. Their widespread acceptance reduces the prospects of constitutional protection and democratic forms of disputation for the many. Every anti-immigrant victory creates further incentives for exclusion by parliamentarians or gangsters on the street. When migrants cease to become a threat because of the success of these policies, exclusionary politics will seek another outlet. Politicians who have been rewarded for their politics of exclusion are unlikely to change course, they are more likely to change target. What we need now is not hand wringing over refugee rights, but a revitalized commitment to constitutional principles. This demands a new politics that delivers on promises for South Africans and foreigners, and holds accountable those who have failed to deliver.

February 19, 2020

Au nom du roi, des roitelets et de la divine providence

Douala Airport. Image credit Guillaume Colin & Pauline Penot via Flickr CC.

For English .

La majorit�� des commentaires relatifs �� la derni��re ��lection pr��sidentielle au Cameroun soulignent et saluent l���effervescence qu���elle a suscit��e. Ce moment est apparu comme un tournant historique, laissant entrevoir la possibilit�� d���une alternance �� la t��te de l���Etat. Une analyse attentive des dynamiques d��ploy��es, montre pourtant, que l���ordre politique en vigueur n���a pas ��t�� fondamentalement modifi��. Il reste structurellement autoritaire, m��lecentr��, oligarchique et client��liste. C���est ce dont t��moigne l���exp��rience du personnel politique f��minin camerounais tr��s minoritaire, et, plus g��n��ralement, l���invisibilisation structurelle des femmes dans l���espace politique. Celle-ci a ��t�� particuli��rement marqu��e lors de la pr��sidentielle. Absentes des candidatures officielles, les Camerounaises le sont ��galement de l���espace m��diatique. Celles qui ont pu prendre part au syst��me politique en transcendant la chape de plomb que leur imposent les contraintes sociales et ��conomiques nourries par des repr��sentations de genre, restent minoritaires et marginalis��es au sein de cet espace. Interrog��es entre 2011 et 2012 sur les dynamiques de l���espace public camerounais, et la mani��re dont elles s���y d��ploient, des figures politiques f��minines (issues de la soci��t�� civile, et des formations politiques de l���opposition comme du parti au pouvoir) ont livr�� des t��moignages qui dressent un constat accablant. Toutes y d��noncent la persistance de contraintes sociales, ��conomiques et politiques structurelles, qui entravent, non seulement, leur capacit�� d���agir politique, mais ��galement, celle de l���immense majorit�� de la population. De plus, le r��gime ne fait pas l�����conomie du recours �� la violence physique, face �� ses adversaires potentiels ou av��r��s, comme le soulignent celles qui militent dans l���opposition. Ainsi, la position de ces femmes au sein de l�����chiquier politique, tout comme leurs t��moignages et les ��v��nements politiques r��cents ��clairent les dynamiques qui expliquent la p��rennit�� du r��gime en place. Trois processus concomitant sont �� l���oeuvre. Il y a une tendance �� la personnification et �� la confiscation du pouvoir par une oligarchie, qui entretient, autant qu���elle se nourri, de la pr��carit�� sociale et ��conomique d���une part, et recourt �� des m��canismes autoritaires pour assurer le maintien de l���ordre dominant.

Le principe de l���expression de la citoyennet�� camerounaise est l���universalit��. Pourtant, dans les faits, lorsqu���elle se d��ploie au travers des institutions, elle est marqu��e par une exclusion sociale et de genre importante. Dans ce cadre, elle n���est pleinement endoss��e que par une oligarchie, dont les membres incarnent l�����thos du pouvoir politique au Cameroun, mat��rialis�� par le tryptique masculinit��, s��niorit��, notabilit��. Les institutions politiques importantes (pr��sidence de la r��publique, Premier minist��re Assembl��e nationale et S��nat) sont dirig��es par des hommes qui ont largement d��pass�� la soixantaine. On retrouve un sch��ma similaire au sein de l���ex��cutif de certaines formations politiques, parmi les plus visibles dans l���espace politique. C���est notamment le cas de l���UNDP (alli�� au RDPC au pouvoir), de l���UDC ou encore du SDF (partis d���opposition) qui ont ��merg��es dans les ann��es 1990, et dont les pr��sidents ont entre 71 et 77 ans. De plus, convaincus d���incarner leur parti, comme la volont�� du peuple et/ou le changement souhaitable, ces dirigeants s���accrochent �� l���ex��cutif de leurs formations politiques. La conservation et la personnification du pouvoir sont donc bien souvent les moteurs de l���action politique des acteurs, au-del�� des clivages ��ventuels. L��, r��side sans doute une des raisons de l���impossible coalition de l���opposition, qui est une condition n��cessaire, bien qu���insuffisante, pour renverser le r��gime actuel. La pr��sence de candidats moins ��g��s lors de la pr��sidentielle (4/9 avaient moins de 50 ans), n���a pas fondamentalement chang�� la dynamique. Chacun a endoss�� le r��le de l�������homme providentiel����. Et alors que le principe de s��niorit�� semble avoir ��t�� ��br��ch��, le consensus tacite d���un espace politique r��git par un entre-soi masculin est sauf.

Cette attitude participe du maintien du r��gime. A cet ��gard, elle s���accommode, autant qu���elle entretient, un contexte socio��conomique caract��ris�� par une absence de justice sociale. Les militantes interrog��es soulignent en effet, l���impact d��plorable sur la repr��sentation et l���agir politique de la majorit�� des populations, d���un contexte d��l��t��re, r��git par des in��galit��s importantes dans l���acc��s aux ressources et aux droits sociaux, ��conomiques et politiques. La paup��risation amorc��e �� la fin des ann��es 1980 dans le cadre des politiques d���ajustement structurel, n���a fait que s���accentuer avec la mauvaise gouvernance caract��ristique du r��gime. Enserr��es dans des probl��matiques de survie (besoins alimentaires de base, acc��s �� l���eau, �� l�����lectricit��, �� la sant��, �� l�����ducation ���), les populations en sont r��duites �� l���urgence d���assouvir des besoins imm��diats. Elles orientent plus leurs attentes vers des personnes identifi��es comme d��tentrices de ressources sociales, ��conomiques et politiques, que vers les institutions ��tatiques, dont la d��faillance semble relev��e de la norme. Cette dynamique se nourrit du discours officiel du RDPC, parti au pouvoir, qui tend �� occulter la responsabilit�� du r��gime dans la paup��risation continue des populations. Suivant le discours officiel, les autorit��s, et encore plus le chef de l���Etat, ne sont pas comptables de la situation d��sastreuse du pays. Dans une rh��torique largement diffus��e dans les m��dias, mais qui sert ��galement de trame au fonctionnement des instances du parti, la charge de l���am��lioration des conditions de vie est report��e sur les populations elles-m��mes. Celles-ci sont alors invit��es ������ prendre en main leur propre destin���� (Petit guide ��conomique et social du RDPC). C���est une logique qui tend �� entretenir des dynamiques relevant de ce que Jean-Fran��ois Bayart a appel�� la ����politique du ventre����. Les populations r��duites �� la subalternit��, sont alors transform��es en une client��le ��lectorale, qu���on entretient a minima, par la distribution ponctuelle de produits de premi��res n��cessit��, durant les p��riodes ��lectorales notamment. C���est ce dont t��moignent les actrices interrog��es lorsqu���elles pr��cisent que la mobilisation politique des citoyen��nes suppose de satisfaire au pr��alable leurs besoins urgents, et de prendre en charge les modalit��s mat��rielles et financi��re de leur action. Cette r��alit�� s���applique �� tous les ��chelons (national, r��gional, partisan) de la vie politique. Cet ordre social est entretenu par un mode de gouvernance politique autoritaire.

Celui-ci repose sur l���exercice d���une violence politique syst��mique aussi bien symbolique que physique. Les politiques publiques (lorsqu���elles existent), tout comme la participation des populations aux institutions modernes, sont pr��sent��es comme des gratifications que le chef de l���Etat accorde �� ses concitoyen��ne��s. Le pr��sident est donc ��rig�� en monarque absolu, voire m��me en une divinit��, qui doit ��tre c��l��br�� pour chaque action entreprise. C���est une approche qui tend �� minorer, absorber, voire m��me, �� nier, les mobilisations sociales et politiques, ainsi leur impact sur l���agenda social et politique officiel. L���objectif est de neutraliser toute perspective critique dans l���espace public, ou, �� d��faut, d���en contr��ler les contours et l���impact, en organisant des sc��nes cathartiques, comme ce fut le cas pour le contentieux ��lectoral d���octobre 2018, retransmis en direct. Lorsque ces strat��gies s���av��rent inefficaces, et que la dissidence (qu���elle s���exprime dans un cadre institutionnel, ou en terme de mouvement social) brave les m��canismes de mise sous silence, le recours �� la violence physique vient compl��ter l���arsenal autoritaire. Les autorit��s proc��dent alors �� des arrestations et d��tentions arbitraires, des personnes au comportement jug�� s��ditieux, qu���il s���agissent de cadres et militant��e��s politiques, des journalistes, des acteurs sociaux, ou encore de citoyen��ne��s ordinaires. Tou.te.s font r��guli��rement les frais de la r��pression polici��re/militaire, et certain��e��s sont m��me soumis �� des actes de torture dans ce cadre. C���est ainsi que les mouvements sociaux men��s par des avocats et enseignants dans les r��gions anglophones en 2016, ont ��t�� violemment r��prim��s. Des journalistes, telles que Mimi Mefo (arr��t��e et incarc��r��e du 7 au 10 novembre 2018), ou encore de Michel Biem Tong (en d��tention du 23 octobre au 15 d��cembre 2018), ont ��t�� incarc��r����e��s pour des affaires en lien avec l���exercice de leur m��tier. Dans l���espace politique, des militant��e��s des formations de l���opposition, comme des personnalit��s politiques de premier plan, sont ��galement victimes de r��pression polici��re, lorsqu���elles initient ou participent �� des activit��s contestataires. Ca a notamment ��t�� le cas de Mich��le Ndoki, avocate et cadre du MRC, parti du principal challenger du pr��sident �� la derni��re pr��sidentielle, ou encore de Kah Walla, pr��sidente du CPP et coordonnatrice de l���initiative Stand Up for Cameroon, qui se pr��sente comme un mouvement social protestataire en lutte contre du r��gime et sa mauvaise gouvernance. La violence du r��gime est encore plus f��roce lorsqu���elle s���abat sur les mouvements contestataires issus des classes populaires. Cela a notamment ��t�� le cas en f��vrier 2008, lors des mobilisations des jeunes qui visaient, entre autre, �� d��noncer la modification de la constitution.

En somme, le r��gime politique camerounais est un syst��me qui s���organise autour d���un roi et de ses roitelets, d��positaires de la sainte providence. Par-del�� des soubresauts ponctuels, sa p��rennit�� est assur��e au sein d���un espace public r��git par la tryptique suivante��: une gouvernance politique autoritaire, fond��e sur une gestion personnelle et essentiellement g��rontocrate et masculine du pouvoir, qui se nourrit, autant qu���elle entretient la subordination sociale, ��conomique et politique des populations.

In the name of the king

Douala Airport. Image credit Guillaume Colin & Pauline Penot via Flickr CC.

Pour Fran��ais cliquez ici.

The bulk of commentary prompted by Cameroon���s 2018 presidential elections not only underscored its significance, the elections represented a historic moment that signaled a possibility of change at the country���s helm. However, any pointed analysis must consider that the dynamics of the country���s political status quo is impervious to change. The country���s political landscape remains structurally authoritarian, patriarchal, oligarchical, characterized by an entrenched patronage system wherein women are hardly represented and rendered invisible. This was the case during the 2018 elections, which did not have a female candidate, and neither did they feature prominently in the media landscape leading up to the vote. Then, those who have defied the economic and social barriers imposed on them by the current system to engage politically are minority and remain marginalized within it. In interviews conducted in 2011 and 2012 with women political figures representing civil society and political parties, both of the opposition and party in power, provided a damning appraisal of their experiences. They denounced a political system that erects economic and social barriers, which disempowers them from full engagement, consequently denying political access to the majority of the population that are women. In addition, the women from opposition parties argue that the regime doesn���t hesitate to resort to violence against their current and potential political opponents. Thus the place of women on the country���s political chessboard, as their experiences revealed in interviews and as recent political developments illustrate, explains how the regime in power has managed to sustain itself. Three related issues are at play; firstly, power is confiscated and personified by an oligarchy who enable a system they impoverish, which on one hand results in social and economic precariousness while using tools of the state to violently maintain law and order to safeguard their interests.

While the experience of women in the political landscape can be said to be global, but in the case of Cameroon it takes on a particularity as evidenced in their relative absence in the country���s main institutions. Those who overcome existing barriers to partake in governance are often at the whim of the oligarchy whose ranks are filled with those who personify the three fundamental ethos of political power in the country, which are patriarchy, gerontocracy and prominence. The institutions that lever the most power; the president of the republic, the prime minister, president of the national assembly and senate president, are far over sixty years old. This scenario is no more different in the ranks of prominent opposition parties, especially those that emerged in the 1990s. It is most glaring in the case of the Union Nationale pour la D��mocratie et le Progr��s (UNDP), an ally of the ruling Rassemblement d��mocratique du Peuple Camerounais (RDPC); the Union D��mocratique du Cameroun (UDC), also the Social Democratic Front (SDF) whose leaders range from their early to late seventies. Convinced that they embody their party���s values, like the will of the people for eventual change, these founding leaders cling to their positions. Therefore, retaining and personalizing power has emerged as the engine driving these political figures, rendering it impossible to form the kind of opposition coalition that could take on the regime. Though four out of the nine candidates in the 2018 presidential elections were fifty-years old and younger, the political landscape remains unchanged despite each of them casting themselves in providential terms. While their efforts might have chipped at the gerontocracy, it also demonstrates an entrenched patriarchal political landscape where elections are contested amongst men.

This tendency is partly why the regime remains in power. In this context, the women in politics tend to have no choice but adapt in a society where social justice is nonexistent. In the interviews, the women politicians addressed the impact this has had in the nonparticipation of women who constitute a majority of the population thereby denying them access to resources, social, economic and political rights. The economic downturn that resulted from the structural adjustment program (SAP) of the late nineteen eighties only entrenched a regime, which has misgoverned the country. With dwindling access to basic daily needs, clean water, electricity, healthcare and education, the masses have been reduced to seeking instant gratification. Due to the failure of state institutions, the bulk of the population has grown to rely on those who control the levers of social, economic and political power. Despite these realities, the ruling RDPC party has been steadfast in deflecting the regime���s role in the pauperization of the masses. In their declarations and speeches, the ruling party leadership, government officials, including President Paul Biya have never taken responsibility for the disastrous state of the country. In messages deployed in the media, which also represents the party���s position, the ruling RDPC, often defers the responsibility of raising standards of the living to the masses themselves. The masses are encouraged ������ to take their destinies in their own hands��� (petit guide). This dynamic has resulted in a system that can best be described as ���belly politics,��� according to Jean Francois Bayart. Barely surviving on the margins, the masses are transformed into electoral pawns whose votes are battered for basic food supplies during political campaigns. In the interviews, the women politicians observed that the masses��� political engagement is often driven their preoccupation with daily survival, in which they stand a chance to benefit materially and financially. It is a reality of the country���s political that transcends region and ideology, and which is sustained by an authoritarian system.

This authoritarian hold on the politics of the country is reliant on systematic violence that is at once physical and symbolic. Public policies as well as citizen inclusion in political institutions are often portrayed as privileges granted at the benevolence of the head of state. Consequently the head of state has been elevated to a divine monarch who is glorified for every public initiative. This political culture has reduced, absorbed, and negated any meaningful political mobilization that could lead to changes in the political order. The status quo���s tendency has been to neutralize criticism in the media, or by working in the shadows to sow disruption as was the case in the 2018 presidential elections���an incident that was broadcast on live TV. Oftentimes, when these methods do not yield results, the system digs into its authoritarian arsenal, deploying violence to impose its will. They often resort to the arbitrary arrests and detention of ordinary citizens, prominent civil society activists, trade unionists, journalist and political opponents of the regime. In the process, they are often brutalized, and in some cases have been tortured. It is no surprise then that the protests led by lawyers and teachers in the Anglophone regions in 2016 were violently suppressed. Journalists like Mimi Mefo, arrested and detained from November 7th-10th, 2018, and Michel Biem Tong, detained from October 23rd, 2018 to December 15th, 2018, were both detained for issues related to them practicing their profession. Meanwhile, in the political landscape, militants and political figures of opposition parties have often been violently repressed, especially when engaging in public political activity. Notably, is case of Mich��le Ndoki, a lawyer and official of the Mouvement pour la Renaissance du Cameroun (MRC) led by Professor Maurice Kamto���the incumbent���s principal challenger during the 2018 elections���was arrested during a protest march against electoral irregularities in Douala. Also, Kah Walla, leader of the Cameroon People���s Party (CPP) and coordinator of the Stand Up for Cameroon initiative, a grassroots movement that engages in direct action against the regime and its bad governance. In fact, the regime often at its most violent when faced against grassroots movements that champion issues of masses on the margins as was the case in February 2008 when youths in Douala and cities across the country contested rising living costs and Paul Biya���s decision to amend the constitution to enable him to run for president.

Beyond occasional jolts, the survival of the current regime is assured because the political landscape in Cameroon is governed by a political authoritarianism based on a personalized, and in essence a gerontocracy and patriarchy, which feeds on itself, while stifling the social, economic and political aspirations of the masses.

February 18, 2020

A ditch to climb

Constitution Hill. Image credit Damien Walmsley via Flickr CC.

In late January 2020, a South African police officer was shot in Diepsloot, a densely populated township in the north of Johannesburg. Fifty-four year old Detective Oupa Matjie was tracking down suspects in a case when he was killed by what media reported as an ���undocumented immigrant.��� Some residents of the squatter community then took to the streets, barricading roads with rocks and burnt tyres, describing the week���s tragedy as a ���wake-up call to fight crime,��� and that foreigners ���behave or leave the country.���

Diepsloot, which means ���Deep Ditch��� in Afrikaans, mirrors the social and political dynamics of the country as a whole. Although it borders the wealthy suburbs of Dainfern and Steyn City outside Johannesburg, Diepsloot is excluded from its neighbours��� prosperity. Since its advent, it���s been widely regarded as a melting pot of people with different ethno-linguistic backgrounds and nationalities. But over the past 10 years, immigrants have been increasingly blamed for crime and social disorder, becoming the targets of violence.

The events last month provided the South African government the opportunity to defend immigrant rights and denounce xenophobia. Instead, Home Affairs Minister Aaron Mostsoaledi was quick to dismiss what little kernel of regard for the plight of immigrants is left in our popular consciousness, glibly stating that ���We must be very careful to label people xenophobic when they have got concerns.���

This aligns with statements made by Gwede Mantashe, who doubles as chairperson of the ruling party, the African National Congress, and Minister of Mineral Resources, who after the violent flare-ups last year said that ���I think it is a lazy analysis when you just limit it to xenophobia ��� without looking at the context and the scramble for resources.��� There is a narrow truth to these utterances, namely that the issue of xenophobia ought to be approached carefully, and with due nuance to the factors giving rise to its prevalence. But South Africa���s recent history of xenophobic violence, met not with condemnation but empty bromides from politicians who profess affected sympathy towards the conditions of South Africa���s poorest, is meant not to clarify anything. Rather, it is to obfuscate their own collective role in reproducing the economic conditions for which they now use foreign nationals as scapegoats.

In Diepsloot, the circumstances of its residents are dire. Originally established as a transit camp in 1995 after a nearby informal settlement was destroyed, the sprawling township has become a permanent home for 300,000 people. As with many South African communities on the margins, the township routinely attracts bad press in mainstream media for being a hotbed of crime and unrest. The government has long been the first target of the public���s frustrations, given its persistent inability to provide fundamental services such as housing, sanitation, and effective policing. It is this same government that now suddenly develops the capacity for swift action, promising to rapidly deploy immigration officials to verify migrant documentation on the streets. This move would be unprecedented for the township.

Since the discovery of minerals in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the region���s economic structure was fundamentally transformed, as the then British administration dispossessed South Africans of their land and imposed colonial taxation, making near obsolete the independent subsistence farming that was then the lifeblood of rural communities. What follows is a well-known brutal and painful history��� what is thought of as ���South Africa���s history,��� one telling the story of the ���South African people.���

But South Africa itself was entirely constituted through international political and economic relations at the nexus of imperialism and capitalism, and it is within this entanglement that many black men and women, by force or compulsion, flocked to find work in or close to South African mines. From the 1860s, they steadily came from Mozambique, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania and Angola. Before that, it was slaves arriving from the Indian subcontinent, and before that, no South Africa to speak of but only disparate and loosely organised settlements of Bantu or Khoisan speaking groups. There are no truly indigenous South Africans; there conceptually cannot be any. What we now call the nation-state of South Africa is a modern invention that has always been a land of foreigners.

It is this shared history of domination and exploitation that the ruling ANC now seems to be forgetting. Many point out the hypocrisy of it having once relied on the aid of other independent African states during Apartheid, yet now failing to act decisively to protect the human rights of immigrants despite sometimes reiterating its commitment to ���pan-Africanist values.��� Yet there has always been a gap between the ANC���s rhetoric and the content of its immigration policies, which reveal a long-standing, conservative orientation. The existing trajectory indicates only more constriction, securitization and deterrence. For example, new amendments to the Refugees Act which came into effect at the beginning of 2020 provides that refugee status can be withdrawn if one engages in political activities or campaigns��� the very basis of civic engagement in a democracy.

The Democratic Alliance has been even more adamant in its anti-immigrant stance. During last year���s election campaign, its posters brandished the words ���Secure our Borders,��� believing that ���uncontrolled immigration violates the rights of ordinary South Africans who have to compete for scarce resources.��� The edifice of anti-immigrant beliefs in South Africa has been built using this idea that immigrants steal jobs, yet there is no reliable evidence to support these claims; if anything immigrants are likely to create jobs where they settle. Still, this doesn���t matter, since the character of anti-immigrant sentiment are precisely hasty generalizations without evidence. As the sociologist Kitty Calavita explains it, ���If immigrants serve as scapegoats for social crises, it stands to reason that the specific content of anti-immigrant nativism will shift to encompass the prevailing malaise.��� In South Africa, this is the worsening despair in the face of entrenched joblessness, with unemployment rates continuing to skyrocket.

The truth is then, that the foundational feature of South Africa���s economy is its structural unemployment. In an economy where the organising principle is the profit motive and the golden rule accumulation, once these ends are met, anyone inessential to that process becomes part of, in the words of Karl Marx, a ���relatively redundant working population, i.e. a population which is superfluous to capital���s average requirements for its own valorization and is therefore a surplus population.��� Even if South Africa deported all immigrants, documented or not, it���s unlikely that South Africa���s unemployment figures would change. As Carilee Osborne puts it, the ���processes of both deindustrialization and financialization have curtailed South Africa���s ability to expand employment, grow wages, and lift people out of poverty.��� South Africans are thus misled into believing that unemployment is natural and it���s inevitable that competition for the few good jobs available should arise. In this set-up, immigrants become perceived as a threat.

Rising xenophobia, criminality and violence is not only attributable to our economic malaise, but the moral decay and social disintegration that flows from it, fulfilling Marx���s ���doctrine of increasing misery.��� The unabating crisis triggered by the 2008 financial crisis has created a world of unending economic distress and anxiety, weakening social bonds and fragmenting communities. It is no surprise then that in this neoliberal order characterized by individualism, social competitiveness, and the triumph of the consumer over the citizen, that people turn to some pseudo-concrete grand subjects to form the basis of an imagined community, such as ���the nation,��� and really anything that draws lines between an ���us��� and ���them.���

This is why the Economic Freedom Fighter���s pronouncements on race and belonging, in spite of their spoken commitment to Pan-Africanism, nevertheless contributes to the discursive stage in which xenophobic violence takes place, entrenching the notion of there being essential differences between groups of people��� if there���s such differences between blacks and whites, and even blacks and browns, why not between blacks and other blacks? The antidote to divisions based on identity is not a retreat into more distinctions, but a politics of solidarity that organizes people around a shared social or political goal. The fundamental question one should ask in this instance, writes British author Kenan Malik, is not ���who are we��� but rather, ���in what kind of society do I want to live?���

Talking about the conditions of people living in Diepsloot, the South African radio show host Bongani Bingwa likened the township to the Gaza Strip and Israel, as a sort of open air prison with restless, immobile residents living in close proximity to fabulously wealthy and resourced suburbs. The South African-based, Cameroonian Achille Mbembe described the Gaza Strip in a recent interview as representing a new kind of social control ���in which people deemed surplus, unwanted or illegal are governed through abdication of any responsibility for their lives and welfare,��� and ���great swathes of humanity [are] judged worthless and superfluous.���

The Assembly of the Unemployed is a burgeoning social movement that seeks to give voice to those deemed surplus in South Africa���s population. Pushing an expanded concept of the working class, it consists of Abahlali baseMjondolo, the Amadiba Crisis Committee, Amandla Botshabelo Unemployed Movement, Progressive Youth Movement, South African Green Revolutionary Council, and the Unemployed People���s Movement. Last week, along with South Africa���s second largest union federation the South African Federation of Trade Unions and the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, it launched ���The Cry of the Xcluded,���a mass campaign against austerity and unemployment, and advocating the expansion of social provision. This nascent coalition presents a unique opportunity to show once and for all, that immigrants are and always have been, part of the excluded.

A people cannot bid farewell to their history

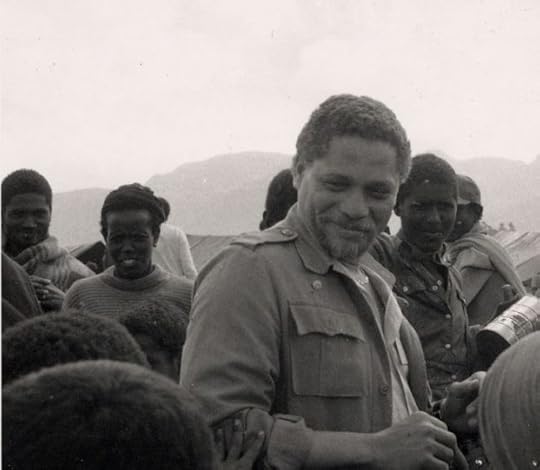

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

This week, Mozambican liberation leader and national hero Marcelino dos Santos (90) will be laid to rest alongside Eduardo Mondlane and Samora Machel in Maputo���s Heroes��� Square. His death severs the last tie between the ruling party Frelimo (Mozambique Liberation Front) and its socialist revolutionary past. Whether this break offers an opportunity for the resurgence of a progressive political movement outside of the confines of Frelimo, remains to be seen. Towards the end of his life, Dos Santos was searching for an alternative political project but ultimately remained loyal to Frelimo until his death.

Dos Santos, or Kalungano as he is affectionately known, was born in Nampula in 1929. He paid his way through secondary school in Louren��o Marques (now Maputo) by working in a factory, and it was there that he was exposed firsthand to the racist violence of the labor regime under Portuguese colonial fascism. That experience planted in him the seed of nationalism, which he would nurture during more than 25 years in exile, returning to Mozambique as an avowed Marxist-Leninist.

Initially, Dos Santos left to pursue an engineering degree in Portugal. There, he met fellow nationalists Am��lcar Cabral (Guinea Bissau) and the Angolans, Agostinho Neto and M��rio Pinto de Andrade, among others. Their cultural and political activism soon caught the attention of the the Portuguese secret service, PIDE, forcing him to flee to France in 1951. At the time, France was a hub of African revolutionary activity, and it was there that he was introduced to likes of Aim�� Cesaire, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

To characterize Dos Santos as a Mozambican liberation leader would be a misnomer, for he was committed to the liberation of the Third World as whole and had a network of close comrades that spanned the continents of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In 1959, Dos Santos got together with President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Cabral (of PAIGC in Guinea Bissau), Miguel Trovoada (CLSTP of Sao Tome and Principe), and Jo��o Gabriel Du (MPLA in Angola) to file a complaint against Portugal with the International Labor Organization on behalf of the people of Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and Mozambique. Portugal had just ratified ILO Convention 105 on the abolition of forced labor, with no intention of implementing it. With help from Nkrumah, Dos Santos and company called its bluff. The ILO set up a commission of inquiry, and the findings triggered widespread reforms across the colonies including: the abolition of the Indigenato, which legally differentiated between indigenous and non-indigenous; and an end to Xibalo (forced labor) and forced cropping. For the first time in almost a century, not working for colonial capital was no longer a criminal offense���at least in law.

The findings of the ILO commission also helped to build the diplomatic case for armed struggle. In 1960, Dos Santos co-founded the National Democratic Union of Mozambique, which merged into the FRELIMO two years later, with support from Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere. In 1964, FRELIMO launched its armed struggle for independence. The following year, the General Assembly of the United Nations, recognized the legitimacy of armed struggle and requested that states provide material and moral support to national liberation movements. Although, it would take a decade of war before the Portuguese colonial state would buckle, diplomacy was key to ensuring the international recognition of liberation movements as the legitimate representatives of the aspirations of colonized peoples.

In 1975, Mozambique gained independence. Dos Santos was FRELIMO���s chief ideologue and the force behind the Front���s decision to transform itself into a vanguard party and proclaim Mozambique a Marxist-Leninist state in 1977. His belief in the power of proclamations was rooted in his conviction that if the structures of socialism could be put in place, the transition to socialism would follow. Not all in FRELIMO agreed, however. As President Samora Machel famously retorted: ���Socialism is not created in a sausage factory.��� In other words, material improvements in people���s lives was a more meaningful measure of progress towards socialism than the structures of the state and party.

Dos Santos was also the first Minister of Economic Planning, and in his approach embodied a combination of the bureaucratic Soviet and popular Maoist principles. He rejected the Soviet characterization of Mozambique as a socialist leaning country that must first undergo capitalist development; and argued for a phased approach to socialist transition rooted in the creation of a worker-peasant alliance. However, he was also an avid promoter of the expansion of state farms, even where these were opposed by the peasantry. He had a tendency to see the countryside as a source of surplus that would feed the process of industrialization, often to the detriment of rural livelihoods. Like many leaders of his time, he was a contradictory figure, capable of acts of incredible authoritarianism, but simultaneously open to popular democracy.

Much has been written about Dos Santos since his passing. Paradoxically, most reflections have ignored the fact that he was a committed communist until the end of his life, preferring to focus on his nationalism, poetry or bohemian qualities. I first met Kalungano at the World Social Forum in Nairobi in 2007. He was sprawled on the grass, talking to young activists from across the world, trying to refine a kernel of an idea. I last met him at a May Day march in Maputo. He was the only high ranking FRELIMO leader who still bothered to attend the ceremonies.

Dos Santos��� passing marks the end of a political era, but as he famously quipped, ���A people cannot say farewell to their history.���

February 17, 2020

Twitter and a new criminal type

South African Police Minister General Bheki Cele at the law enforcement parade. Image credit Government of South Africa via Flickr CC.

In July 2018, the popular Twitter account run by Yusuf Abramjee (@Abramjee), a self-described ���anti-crime activist” and former CEO of popular South African radio staion Radio 702, posted photos of four men, arrested allegedly for cash-in-transit robberies in Gauteng province. In spite of Abramjee���s triumphant tone, some followers were dissatisfied. They were unhappy with the way the men were pictured���each handcuffed and faced away from camera. ���Why are they letting them hide their faces,��� one comment reads, ���we deserve to know them.��� Another: ���am I the only one who wants to see their faces?��� Still others: ���Show them to us,��� ���show us their faces,��� ���please show their faces;��� ���we need to see their faces.���

These comments are by no means exceptional. In recent years, police officials and crime-obsessed accounts like Abramjee’s have taken to posting photos of arrestees, obscuring their faces in part or in whole in keeping with the Police Act of 1995. Though they are aimed at demonstrating the efficacy of the cops, these posts always spark indignation that, as one user put it, ���crime committers��� faces are always hidden.���

What does one make of this seemingly sincere desire to see the faces of ���criminals?��� Commenters offer a range of justifications for their demands. Obscuring faces prevents witnesses to other offenses from coming forward; it affords ���criminals��� rights to privacy they don���t deserve; it allows the cops to stage fake arrests; it prevents citizens from ���knowing��� them when they show up on their ���doorstep.���

As Nicolas Smith points out in his recent book, these attitudes evidence how South Africans distrust not only law enforcement, but also the country���s liberal legal order itself, which many South Africans say values due process too much and often lets the guilty go free. Knowing the face of ���the criminal��� then allows citizens to hold government to account or to defend themselves in the event that the state fails to provide safety. Indeed, much of ���crime Twitter,��� replete with recriminations against the cops and BOLOs (���be on the lookout���) for citizens, operates under this logic. It is part civil society, part neighborhood watch.

But this seems to be only part of the picture. Commenters are indignant even when those pictured have [click warning: graphic violence] been shot dead by the police and pose no possible threat. What then do the faces of dead ���criminals��� reveal? And what might this fascination in displaying and seeing the body of ���the criminal��� tell us about South Africa today?

In considering this question, it is useful to remember that for much of South African history the imagined figure of the criminal has been remarkably stable. White settler rule engineered a legal regime geared around the criminalization of black labor, leisure, and resistance. And as the state monopolized wealth and power for the minority, it forced those it dispossessed into criminalized economies to survive. The results were predictable. One need not read clippings from the turn-of-the-century Rand Daily Mail���s ���Police Courts��� section to know that the country has long been fixed on the young, poor, black man as the figure of criminality par excellence. (The Rand Daily Mail would later became associated with liberal opposition to apartheid; its early days, however, betrays its more racist roots.)

South Africa, of course, is not unique in this respect. The United States and Brazil, among other nations, have been built on similar racist libels. And Stuart Hall famously documented how in the 1970s, the UK became panicked over ���muggings,��� which newspapers and television attributed to ���black youths.��� Indeed, Hall���s analysis might lend insight into this puzzling fascination with seeing the face of ���criminals��� today. In his book Policing the Crisis, Hall argues what was unprecedented about ���mugging��� was not the crime itself���a form of petty theft���but the label, imported by British media from the US and laden with connotations of racial enmity. The effect was the invention of a new criminal type, ���the mugger,��� a threat against which the state could re-build its legitimacy among the white segment of the working class in a moment of political and economic crisis.

South Africa is in the midst of a political and economic crisis at least as deep that of the 1970s UK’s. But despite decades of panic over crime and a brutal policing apparatus, the country lacks a new criminal type to mobilize against. The inherited figure of the criminal is so freighted with the baggage of apartheid and too close to a description of the majority of men in the country. It survives very uneasily alongside the ruling ideology of rainbowism and black uplift. One can glimpse this mismatch in the public comments of Police Minister Bheki Cele who often ends up scolding, rather than acquiescing to communities demanding greater safety. At a recent ���crime imbizo,��� Cele lectured his audience in isiZulu, saying: “Azik��� izigebengu e���fike imvula. Wonke ama-criminals aphuma ezindl���enu” (There is no rain that rains criminals. All criminals come from your houses). Needless to say, accusing your constituents of being ���criminals��� is not the soundest electoral strategy.

But if Cele cannot find his way beyond the contradiction between the regnant criminal type and the exigencies of the contemporary crisis, those on Twitter might have a better view on things. Indeed, in the online fascination with displaying and seeing the body of ���the criminal������even of those deceased, we can glimpse users trying to work inductively, developing a generalizable criminal type by reading closely the bodies of arrestees. The hidden face, however, presents a certain blockage to this process: it veils what might be the telltale signs.

By wanting to read the body in its fullness, commenters���who are mostly black South Africans���demonstrate the inadequacy of a purely race-based criminal type. But crucially, they do not dispose of its logic entirely. The convenience of race, after all, lay in its illusory ability to make criminality into something that was inherent to a definite group of people, and legible���able to read off the body itself. By subscribing to the notion that there exists a group of people who are essentially and visibly ���criminals,��� users seem to be trying to develop a new criminal type in the image of its predecessor.

In this strange way, hiding the faces of ���criminals��� facilitates, rather than blocks, citizens��� ability ���to know them.��� After all, there are no telltale signs. Should they be presented, nothing would be revealed. They would be familiar faces, those of neighbors, relatives, friends, acquaintances���victimized like the majority of South Africans by decades lost to austerity, corruption, and grinding inequality.

February 16, 2020

Reading List: Benjamin Talton

Mickey Leland. Image credit Penn Press.

In my book, In This Land of Plenty: Mickey Leland and Africa in American Politics, US Congressman Mickey Leland���s activism inside and outside of government is a window into the tangled relationship between the US and Africa. During Mickey Leland���s tenure in Congress, from 1979 until his untimely death in August 1989 while traveling to a refugee camp in southeastern Ethiopia, he was Congress���s most dynamic and active voice on African issues. Leland, with a small but impactful group of former black radical activists with well-defined connections to Africa, used the power of their office to play an outsized role in the international movement to end white-minority rule in southern Africa. This period was the pinnacle of African Americans��� long, dynamic history with African politics.

While writing, I consulted a diverse collection of scholarly texts, novels, and memoirs that deserve special mention. Space here limits me to briefly highlighting four texts that uniquely resonated with my ambition to craft a multinational narrative in the book and to enhance my understanding of the Ethiopian revolution, its aftermath, and the conflicting relationship between pan-Africanism and national sovereignty in Africa.

With these goals in mind, I framed Leland���s activism broadly within Cold War politics and liberation struggles in Africa. Vijay Prashad���s The Darker Nations: A People���s History of the Third World is a nuanced, far reaching analysis of the Third World and the Cold War. Few texts match the strength of his explication of the perilous rise, fragility, and ultimate failure of Third World solidarity. The Darker Nations also illustrates the value of histories of failed and unfulfilled movements. The histories of leftist student movements, pan-Africanism and black power, which all converge in In This Land of Plenty, demonstrate the intellectual rewards of scrutinizing the offshoots, afterlives, and inspirations from Third World internationalism.

It was challenging to present these movements as strands powerfully yet loosely connected. I grappled with how to effectively convey unity���s elusiveness within the global south, whether built on Third World solidarity or, more narrowly, on pan-Africanism. Leland worked through the Congressional Black Caucus, the United Nations, and on his own accord to build a network of political leaders, policymakers and activists to work toward eliminating chronic hunger in Africa. His failed effort reflects the tenuousness of African solidarity built across multiple issues and national borders. Monique Bedasse���s Jah Kingdom: Rastafarians, Tanzania, and Pan-Africanism in the Age of Decolonization shows the similar challenges that constrained pan-Africanism. She presents Tanzania as the heartland of pan-Africanism in the wake of the coups that ousted Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Ethiopia���s Haile Selassie. Countless pan-Africanists of the time traveled to and temporarily relocated to Tanzania. Mickey Leland, as I describe in my book, was one of them. For him and others, Tanzania was pivotal to their political education. Yet, through the experiences of small groups of Jamaican Rastafarians who sought to migrate and settle in Tanzania during the 1970s and 1980s, Bedasse presents the difficulty pan-Africanists had reconciling their pan-Africanist sensibilities and aspirations with the domestic and foreign policies of African nation-states.

Jah Kingdom is a vital addition to an increasingly rich scholarship on pan-Africanism and decolonization in Africa and the diaspora. I similarly entwine decolonization, black power, pan-Africanism, in In This Land of Plenty, with the added dimension of the international student movement. Although these movements had divergent outcomes, they were inspired by many of the same social, economic and political grievances, conditions, and philosophers. Student activism in the US, Europe, and South Africa has been well documented, but there is surprisingly little scholarship on the Ethiopian student movement and its connections to decolonization elsewhere in the continent and African-American radical activism. Important exceptions are Bahru Zewde���s The Quest for Socialist Utopia: The Ethiopian Student Movement, c. 1960-1974 and Gebru Tareke���s The Ethiopian Revolution: War in the Horn of Africa. The former is a robust, comprehensive exploration of the students and intellectuals who were active in the movement that ultimately led to the fall of the Ethiopian monarchy. It proved to be an invaluable resource for me as I gained an understanding of the Ethiopian revolution���s innumerable factions, organizations, issues, and events. The Ethiopian Revolution rounds out this history of activism and revolution in Ethiopia. Tareke provides an exegesis of the complexities of the revolution and the civil wars, the Ogaden War, and the Eritrean secessionist war that erupted in its wake. Again, in light of the local and regional implications of the Ethiopian revolution and civil wars, it is perplexing that Tareke and Zewde���s books remain among the only comprehensive English-language analyses of the Ethiopian revolution.

In This Land of Plenty ties these historical events and processes in Ethiopia to issues and events in the US, Sudan, and in southern Africa. I emphasize the events of late stage Third World solidarity and the end of the Cold War in Africa. I place black power, the Ethiopian student movement, black consciousness in South Africa, and the anti-apartheid movement within this framework as constrained by the hegemonic forces of the US and other western powers��� dogged crusade to undermine challenges to western-style neoliberalism, even at the expense of African nations��� sovereignty.

February 13, 2020

The mysterious death of a UN Secretary-General

[image error]

Dag Hammarskj��ld with Egidio Ortona in New York, 1959. Image via Immaginario Diplomatico (1861-1961) on Flickr CC.

It was the night of 17 to 18 September, 1961. A DC6 plane named Albertina (officially: SE-BDY) was approaching Ndola, the mining town in Northern Rhodesia (today Zambia) bordering with the Congo. On board was Dag Hammarskj��ld, the Secretary-General of the United Nations. 15 other people (crew and entourage) were in his company. Considered a risky mission, the aim was to meet Mo��se Tshombe, leader of the secessionist Katanga province, to find a solution to the conflict in the Congo. The spontaneous intervention, decided only shortly before by Hammarskj��ld after arriving in the Congo, was followed with suspicion by various Western diplomats and intelligence agencies. They were afraid that a deal bringing Katanga back into the Congolese state might threaten the vested Western interests. After all, this was at the height of the Cold War, who had started to leave its marks on the continent. Their worries were unnecessary: about to land, the plane crashed under hitherto unclarified circumstances. This meeting never took place.

Why Katanga?

Katanga had declared its break away after Congo���s Independence in June 1960. The mineral-rich province was of utmost geostrategic relevance and the world���s leading producer of uranium. US American nuclear armament in the 1950s was dependent upon the local Shinkolobwe mine, which had also delivered the nuclear material for the bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The mine���s history has been captured by Susan Williams in the book Spies in the Congo. Katangese resources were mainly exploited by the Belgian Union Mini��re du Haut-Katanga and other Western mining companies, jealously guarded and protected by Western interests. The Katangese separatists had also direct military support from Belgium and mercenaries from all over the (Western) world. Afraid to lose control over Katanga with Congo���s Independence, the secession was encouraged, supported or at least tolerated by the Western states.

Enter Hammarskj��ld

As Secretary-General of the United Nations since 1953, the Swedish diplomat succeeded the Norwegian Trygve Lie as the highest international civil servant. He is widely considered as having set norms as a role model for this job and received much praise since then, notably by Brian Urquhart, Manuel Fr��hlich and Roger Lipsey. Others were less affirmative, expecting him to act as an instrument of Western imperialism. Ludo de Witte even accuses him for being personally responsible for the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, who was brutally tortured and executed only nine months before Hammarskj��ld died.

In a recent book, I have advocated a different perspective. It follows to some extent the belief that values and principles do matter even in asymmetric power relations. Individuals do have choices and options, despite all the limitations of an office in a global governance institution in which the powerful states have the say. They thereby can make a difference in leading positions with some influence over decision-making processes. As I try to show with reference to Hammarskj��ld���s interpretation and application of the global normative frameworks, not least the UN Charter itself, he was guided by a firm belief in codified values. Promoting decolonization made him a Secretary-General, mainly of those new member states of the United Nations who had no voice at the table of the big powers. I maintain also, with reference to the mandates obtained and pursued with regard to the Suez crisis and in the Congo, that in today���s jargon his diplomacy would qualify as anti-hegemonic. Towards the end of his time in office, his critics were from both the Soviet and the Western world. In contrast, many among the new member states entering the United Nations, considered him���despite some failures���as ���their��� Secretary-General.

Hammarskj��ld personifies by his approach, as I tried to explain in a recent conversation that even in an office limited by big power interests and politics, personal ethics, a moral compass, and solidarity do matter, and that individuals are not predetermined by a specific socialization. Individuals have choices: ethical leadership and conscience affects politics, as also argued by Roger Lipsey.

Death at Ndola

Dag Hammarskj��ld, and with him all but one, died in the wreckage of the Albertina shortly after midnight on September 18, 1961. The bodyguard Harold Julien succumbed to his injuries six days later in a local hospital. Evidence suggests that he could have been saved if treated properly���and if taken care of earlier: While the plane had been in contact with the tower at the airport before disappearing, with a range of diplomats, secret agents, mercenaries, officials, journalists, and other people on the ground awaiting the arrival, a search mission was delayed until the next morning. The wreckage was officially discovered only in the afternoon. But several eyewitnesses testified later that the crash site was already cordoned off and access denied early in the morning. Suspicions were immediately nourished that there might have been foul play involved. Not only did investigative journalists then already point in this direction, even former US President Harry S. Truman was quoted in the New York Times on September 20, 1961 stating: ���Dag Hammarskj��ld was on the point of getting something done when they killed him. Notice that I said ���When they killed him���.���

The inquiry by a United Nations Commission ���noted that the Rhodesian inquiry, by eliminating to its satisfaction other possible causes, had reached the conclusion that the probable cause of the crash was pilot error. The Commission, while it cannot exclude this possibility, has found no indication that this was the probable cause of the crash.��� With Resolution 1759 (XVII) of October 26, 1962, the General Assembly therefore requested the Secretary-General ���to inform the General Assembly of any new evidence which may come to his attention.��� But aside from some conspiracy theories and other speculations, as well as a half-hearted and inconclusive additional investigation initiated in Sweden dismissing some of these in the mid 1990s, the case was shelved for half a century.

New investigations

Fifty years later, Susan Williams���a historian with the Institute for Commonwealth Studies/School for Advanced Study at the University of London���presented a bombshell with Who Killed Hammarskj��ld?. The new evidence, pointing to many flaws and failures of the earlier findings, triggered a new inquiry conducted by an independent, international commission of jurists, which produced a report in 2013. As a direct consequence, a series of official investigations mandated by the United Nations followed since then. The chronology of events is listed by the Dag Hammarskj��ld Library at the United Nations in New York. The United Nations Association Westminster Branch in London provides continued updates on developments since 2014 on a dedicated website. It is striking to note, that all of this happens because of a scholarly book and a subsequent private initiative taken by a handful of individuals, who were able to convince the UN system that the open-ended resolution adopted in 1962 deserves new efforts to find out what really happened then.

A panel of three experts was set up by Ban-Ki Moon to verify the findings of the independent commission. Headed by the former Chief Justice of Tanzania, Mohamed Chande Othman, it presented a report in 2015, which considered the findings as credible. Following more explorations, Othman was appointed in 2017 as Eminent Person, tasked with further investigations. His report concluded ���that there is likely to be much relevant material that remains undisclosed��� and ���that the continued non-disclosure of potentially relevant new information in the intelligence, security and defense archives of Member States constitutes the biggest barrier to understanding the full truth on the event.��� Most importantly, based on the new evidence collected, ���an aerial attack on SE-BDY would have been possible using resources existing in the area at the time.��� As a result, and due to a resolution submitted again by the Swedish Permanent Mission (co-sponsored by another 70 states, notably including as the resolution before Belgium, France, Germany and Russia, but once again without support of the USA and the United Kingdom), the General Assembly extended Othman���s mandate.

He presented his second report in September 2019, summarizing the current knowledge. It based his conclusions on some reports of ���independent high-ranking officials,��� which several Member States were requested to appoint. This move was seeking to shift the responsibility to the Member States directly involved in the events then. These appointees were supposed to investigate local archives and other intelligence sources in search of additional information not yet accessible. However, those states where most of this information could be expected (the USA, the UK, and South Africa) were among those who made no efforts to comply. However, more evidence was gathered by other private individuals. These included the French journalist Maurin Picard who presented new insights mainly into the Belgian mercenary networks of the time, as well as the Katangese capacity to launch an aerial attack. Torben G��lstorff discovered a German link to Katanga.

���The new information received,��� concluded Othman, ���highlights the fact that there were many more foreign mercenaries in and around Katanga, including pilots, than had been considered by earlier inquiries.��� These had the logistics and necessary conditions (suitable planes and airfields close enough for such operation) to intercept the approaching plane. New information also confirmed original eyewitness reports that the crash site was much earlier discovered than officially reported. Not only did this most likely contribute to the death of the only survivor, whose treatment was delayed for hours, it also, as Othman notes, ���calls into question the acts of various Governments directly after the crash and leaves open the issue of why the earlier crash discovery time was not reported.���

Most importantly, for Othman ���it remains plausible that an external attack or threat was a cause of the crash.��� He therefore recommends:

that an independent person is appointed to continue the work;

that key Member States be again urged to (re)appoint independent high-ranking officials to determine whether relevant information exists within their security, intelligence and defense archives;

that a conclusion be reached if Member States have complied with this process;

that key documents are made publicly available online.

As a follow up, the Swedish Permanent Mission again submitted a draft resolution to the General Assembly, following to a large extent the recommendations by re-appointing Justice Othman as the Eminent Person to continue the investigation. In December 2019 it was adopted with a record number of 128 co-sponsoring countries���but again, and revealingly so, without the support of the United States and the United Kingdom.

Current challenges

It might be indicative of diplomatic constraints and reluctance that the resolution omitted the recommended commitment to take those member states to task, states who might not comply with the renewed appeal to identify and provide access to hitherto unknown or classified information. Naming and shaming are not in the diplomatic etiquette, though it would in this case be one of the very few (if not only) forms of leverage handed to the Eminent Person.

The other major constraint which continues to hinder the investigations is the limited budget, which tends to degrade the activities to mere tokenism. Reinforced by the liquidity problems the world organization is facing more than ever before, the amount allocated is about US$350,000 (roughly $150,000 for 2020 and $200,000 for 2021, including all costs for translating the report to be submitted into the official languages). While this limits the efforts considerably, the continued efforts authorized continue to have a significant symbolic meaning. As the Westminster Branch of the UK���s UN Association observes on its Hammarskj��ld Inquiry site: ���Noting the UN���s current funding shortfall ��� observers view this decision ��� and a record number of cosponsoring Member States to be a clear indication to those few states which have failed to cooperate.���

With all evidence gathered during the last few years, it is not premature to categorically dismiss the pilots��� error assumption as a convenient smokescreen and potential cover up. Considering what is known today, it is far more likely that the value-based policy of Dag Hammarskj��ld came at the highest price, not only for him but also for the 15 others in his company. After all, he was trying to find a solution for the conflict in the Congo against the interests of the West. This casts doubts on the perception that the Swede was (despite his looks) the blue-eyed boy of the Western world. Rather, as I suggested in my recent book, ���he seemed to believe that taking sides with the less influential members of the world community would be in many (if not most) cases the right thing to do.��� Hammarskj��ld can indeed be considered an example that neither pigmentation, nor nationality or cultural background, despite their socializing influences, necessarily define criteria for being aware of what is right and what is wrong���and how to act accordingly.

February 12, 2020

A Green New Deal for South African workers?

Pruning fruit trees in South Africa. Image credit Trevor Samson via World Bank Flickr CC.

Speaking recently on a proposal for significant economic reform, Matthews Parks, Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) Parliamentary Coordinator, made the following extraordinary statement: ���Both environmental and economic denialism are dangerous and should not be entertained. We think we can and must tackle climate change and unemployment simultaneously. All it requires is creativity, political will, planning and resources.���

Until now, a recognition of the link between questions about climate crisis mitigation and other economic crises has largely been missing in African countries. Unions in particular have often been seen as the enemy of climate politics, especially in countries like South Africa which have large extractive industries and strong unions of miners and other workers. However, there has been a shift recently with more and more radical climate activists recognizing the necessity of getting unions on board. Unions on the other hand are also more frequently being convinced of the necessity of political projects like the Green New Deal, especially within the context of growing inequality and job losses.

South Africa has some not so-coveted titles: most unequal country in the world, 13th largest carbon emitter, and some of the highest rates of unemployment globally. Within this context, COSATU���s proposed interventions represent a flicker of hope in an otherwise dire picture for South Africa���s commitment to tackle both the triple threat of poverty, inequality, and unemployment, and the climate crisis. While the expanded proposition focuses on a range of struggling state-owned entities, the primary intervention relates to the dire situation at Eskom, the state-owned power utility.

COSATU���s ���Key Eskom and Economic Interventions Proposals,��� emphasizes that it is poor and working-class people who will bear the brunt of continued inaction, especially as talk of an IMF loan continues to percolate. The presentation calls for a commitment to concerted and urgent interventions in the economy before this month���s annual State of the Nation (by President Cyril Ramaphosa) and budget (by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni) speeches, on which a decision about whether to downgrade South Africa���s credit rating to so-called ���junk status��� are said to partly rest.

Under the banner of a ���pro-worker Eskom turn-around strategy,��� COSATU insists on guarantees that, amongst other things, Eskom will not be privatized, no worker will lose their job and major investments will be made into stimulating local industries, including the expansion of the use of renewable energy. In return, COSATU will support the use of funds from the Public Investment Corporation (PIC) which manages public assets including for the Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF) and the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF). This will be done in order to bring Eskom���s debt down to the ���manageable��� R200 billion mark.

Likely speaking both figuratively and literally, Parks is quoted as saying:

The waters are rising. We���ve been keen to stop all this talking about a just transition and actually get things moving, so that we have it. We know we could lose whole sectors, we know we are facing a bloodbath, so we need government to use whatever sticks it���s got to force industry to look at just transitions for every sector of the economy, not only energy.

COSATU appears to be following this advice themselves, using the Eskom crisis as the linchpin for securing a pro-worker strategy and, for now at least, it may be working. The proposal is said to have garnered ���wide-support��� within the ANC���s highest decision-making body and reports indicate that a deal may have been struck by representatives from government, business, and labor following recent talks.

Understandably, there are skeptics. Many on the right responded with the usual fearmongering, presenting the move as an attempt to ���loot��� pensions. However, as is argued in detail by Dominic Brown, Economic Justice Program Manager at the Cape Town-based Alternative Information and Development Centre (AIDC), there is a sound economic foundation for expanding the investment profile of the PIC and using surpluses in both the GEPF and UIF to aid and develop state-owned entities as opposed to financing them out of the fiscus. This is especially when the latter option would deepen austerity limiting the potential for investment in social services and meeting infrastructure developments, thus threatening to further contract the economy.

While the developmental case for using PIC funds for entities like the state-owned airline South African Airways may be weaker, the importance of Eskom cannot be overstated. Eskom cannot be allowed to fail, but it needs major interventions both operationally and financially. Appropriately used, a massive investment into Eskom, which not only reduces its debt but also builds renewables and ensures financial security for workers in the coal mining sector would be highly beneficial.

Commentators regularly call for ���structural reforms��� in the South African economy with little attention given to what kind of structural problems need reforming. One of these is the fact that the post-apartheid era has been characterized by ���high-profit, low-fixed investment.��� This is linked to how processes of both deindustrialization and financialization have curtailed South Africa���s ability to expand employment, grow wages, and lift people out of poverty. The deeply unequal legacy of apartheid among other factors in South Africa���s political economy make these processes particularly brutal. COSATU���s proposal, carried out coherently and in line with the various conditions attached, could be a starting point to undoing this.

Getting support for this is not straightforward, and skepticism has not only come from the right. It has become increasingly difficult to counter distrust in the state given the depth and scale of corruption and inefficiencies that we are exposed to daily. Zwelinzima Vavi, General Secretary of COSATU���s rival federation, the leftist SAFTU (the South African Federation of Trade Unions), has warned about how the loss of legitimacy in public institutions has resulted in a bolstering of conservative forces to such an extent that even the working class can be mobilized to defend a conservative agenda. A recognition of the impact of State Capture is also evident in additional demands made by COSATU that relate to an audit of the public service and the removal and prosecution of corrupt individuals. The state���s loss of legitimacy represents a real and very present challenge for the left and it must be reckoned with. COSATU acknowledges this in the proposal introduction:

Not only must the Alliance and government defend the right of both the private and public sector workers to a living wage and labor protections but equally it is critical for the Alliance and government to defend the role of the state to deliver critical public services and goods, to participate in and to ensure competition in the economy. If not we face the real risk of the state being forced to retreat on all these fronts given the extent of the state and economic crises. This would leave workers exposed and unprotected.

COSATU���s alliance with the ANC (and the South African Communist Party) is regularly derided given the trajectory of the ruling party in the post-apartheid era. They have been criticized for not breaking with them over neoliberal reforms in the 1990s, nor during the State Capture period under former president Zuma. This in part led to the breakaway of a major union, NUMSA (the National Union of Mineworkers), and the formation of SAFTU. While the federation is undoubtedly weakened as a result, they are still a major force in South African politics. Structural change at Eskom is almost impossible without them and thus their support for such proposals���akin to the start of a Green New Deal���goes a long way to shoring up support for these ideas within the country.

There are, however, important limitations that should be flagged. The links between the climate and economic crisis is far less explicit in the proposal than in the comments by Parks, and there are worrying references to the need to invest in ���clean-coal,��� which experience has shown is a dangerous misnomer. COSATU should be unequivocal in the demand for decarbonization while they continue to push for a deep and just transition for mining communities. The push back from those with vested interests in the fossil fuel industry, many from within the ANC and COSATU itself, will be strong and will require concerted struggle to counter.

Parks is right that this needs to cut across all sectors of the economy in order for a proposal of this sorts to radically change South Africa���s socioeconomic and emissions profiles. But, it also requires that this not be limited to only unions or the protection of the already-employed and unionized workers. Indeed, job creation and protection are necessary but not sufficient conditions to realizing real socioeconomic change in South Africa. Proposals to use the PIC and to link changes to a just transition have come about by civil society groups, like AIDC, working with unions to develop plans that are inclusive of worker���s needs. The same process needs to happen in broad alliance with groups like the Assembly of the Unemployed, housing rights movements like Reclaim the City, public transport activists like #UniteBehind, and crucially, groups like the Mining Affected Communities United in Action.

In her book, This Changes Everything, Canadian writer Naomi Klein makes the argument that the climate crisis, because it poses an almost existential threat, gives us points of leverage from which to force major changes. Parks himself seems aware of this: ���Never let a good crisis go to waste,��� he said.

February 11, 2020