Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 193

January 19, 2020

Where will neoliberalism end?

The old derelict beach pavillion at Macassar, South Africa. Image credit Steve Crane via Flickr CC.

As the world was overtaken by upheaval last year, one photo emerging from the uprisings depicts a protestor bearing a promise: ���Neoliberalism was born in Chile and will die in Chile.��� Spilling over into the new year, the revolts in Chile, Lebanon, Iraq, Sudan, Hong Kong, Algeria, Uganda, France and elsewhere have led many to believe that the present insurgency spells the definitive end of the neoliberal consensus that has unraveled since the 2008 financial crisis. In particular, the outbreak of resistance in Chile was a watershed moment for some, a symbolic requital for the suffering endured by it as the ���birthplace��� of neoliberalism. With the close counsel of The Chicago Boys, General Pinochet imposed the doctrine through a brutal dictatorial regime from 1973 onwards and spurred more than 30 years of orthodoxy based on trade liberalization, financial deregulation and privatization that fundamentally transformed the world economic order.

A notable absentee from the recent flare-ups is South Africa, especially when considering how plagued by turmoil it had been in the months prior to the ���season of discontent��� that erupted in October 2019. It is no overstatement to say that around that time, things looked miserably bad. In September, the country experienced a surge in xenophobic attacks helped along by the state���s targeting of informal traders in Johannesburg���s inner city, as well as nation-wide demonstrations against rampant gender-based violence precipitated after a university student was horrifically raped and murdered at a post-office in Cape Town. Anger and outrage, both reactionary and righteous, brought the country to a standstill.

Handed a fleeting piece of supposedly good fortune, this powder keg of disaffection was disarmed by South Africa���s triumph in the Rugby World Cup held in Japan. After that, the mood of most South Africans was a mix of genuine jubilation and uneasy relief, the shared sentiment being that ���we needed this.��� This was even understood by the rugby team itself, with captain Siya Kolisi and coach Rassie Erasmus talking frankly after the tournament about the extent of hardship at home which fueled the team���s thirst for glory, and Siya���s own background of personal adversity functioning as a feel-good story of black uplift. Indeed, one doesn���t have to search too deeply to find evidence for the scale of problems. With inequality framed as a key trigger for the worldwide unrest comes the circulation of literature breaking down the disparities between rich and poor���in Chile and Lebanon, they are frighteningly high. But in this respect too, South Africa unfortunately comes out on top, consistently crowned the world���s most unequal country.

And so, we should not be deceived by the additional respite provided by the just-passed festive period���things are still miserably bad, they have been for a long time. Unemployment sits appallingly at 40%, leaving 55% of the population mired in poverty. The most recent research indicates that 10% of the country owns 90% its wealth, and carrying the legacy of Apartheid, these disparities are highly racialized. Unable to meet energy demands, the national power utility regularly implements rolling blackouts, prompting flirts with privatization as a strategy to save it from collapse. All the while, a spate of freak weather incidents brought the incontrovertible fact of climate change to the lives of ordinary South Africans. Any calm is just a reckoning postponed.

A brief glimpse into the historical record suggests that things did not have to turn out this way. South Africa���s economic future came to the fore in the early 1990s at a crossroads where, tasked with devising a suitable post-apartheid political settlement the question of how to integrate South Africa into the world capitalist system while rapidly improving living standards also lingered. We came depressingly close to charting a redistributive alternative that envisioned a central role for the state in promoting development. Persuaded by the Congress of South African Trade Unions, one of its key alliance partners, the African National Congress, in 1990 circulated a discussion document pushing forward a ���growth by redistribution��� approach to economic policy through its nascent economic research arm, the Department of Economic Policy.

Efforts to assert a progressive economic agenda culminated with The Macro-Economic Research Group���s report, ���Making Democracy Work��� in 1993. Set up by the ANC in 1991, MERG established a neo-Keynesian policy framework combining a ���strong private sector interacting with a strong public sector��� undergirded by public-investment led growth. By the time it was published, however, the situation had dramatically changed. The ANC came under enormous pressure to clarify its economic strategy, further strained by its long-standing neglect of developing sound economic policies of its own. A great variety of corporate-sponsored scenario planning exercises gained momentum looking to enlighten the ANC of ���the economic realities of the world.��� South Africa���s future Finance Minister and Reserve Bank governor, Tito Mboweni and Lesetja Kganyago, even underwent training at Goldman Sachs���Mboweni at the time headed the ANC���s department of economic planning. By the mid-1990s the MERG���s report was sidelined, and in the words of journalist Hein Marais in his acclaimed study of the transition ���the embrace of orthodoxy would be unnervingly swift and emphatic.���

On Labour Day in 1994, a few days after being elected South Africa���s first black president, Nelson Mandela declared to domestic and international capital: ���In our economic policies, there is not a single reference to things like nationalization, and this is not accidental. There is not a single slogan that will connect us with any Marxist ideology.��� The volte face was complete. The story of the triumph of market dogma in South Africa is the subject of many a book and all too familiar. It begins with the infamous lifting of decades old capital controls in 1995, and develops to South Africa becoming the most financialized economy in the Global South excluding Asia. If neoliberalism was born kicking and screaming in a Chile, it confidently strode into maturity in South Africa.

The ANC���s economic leadership has mostly brought about rapid deindustrialization, the consolidation of an extractive and financialized minerals energy complex, and the creation of a black bourgeoisie whose poster boy and billionaire mining magnate Ramaphosa, is now president. This is not to deny that significant changes have happened for the poor, especially in basic service delivery. Yet these have been motivated by the goal of minimum provision and sufficiency rather than equality, and are proving in fact, insufficient. The decay of this social compact has been obvious. Since former president Jacob Zuma���s corruption-ridden regime came to power a year after the global financial crisis, South Africa has been in permanent crisis: from the state���s murder of miners at Marikana in 2012 to the #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall protests in 2015 and 2016. Service delivery protests are a daily routine, and escalating gang wars in some parts, especially the Western Cape, make obscene violence a daily reality. The students were right to demand that ���everything must fall.��� But if so, what will rise in its wake?

Last year���s general elections are a poor indicator of things to come. The leading story of that was low turnout, with only two-thirds of registered voters pitching up, and another ten million eligible to vote not registering at all. The center held nevertheless, with the ANC prevailing and the center-right Democratic Alliance maintaining its role as official opposition–although both parties fielded their weakest electoral performances to date, and are caught in a global pattern witnessing the erosion of the political center. So, for good reason in these unsettled times, it has become vogue to invoke the words of Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, who, writing of the fall of the laissez-faire liberal order after World War I, warned that ���The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying but the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.���

One of the first casualties in these moments of disequilibrium is the left-right axis along which politics is traditionally mapped, as ruling coalitions start to wither and lose internal coherence. For the last couple of years, the ANC and DA have been hotbeds of dysfunction. Factional battles in the ANC are playing out between Ramaphosa and forces loyal to the embattled Zuma (the latest is that Ramaphosa will be out as president before the end of the month), including politicians implicated in wrongdoing during Zuma���s reign of ���state capture.��� That this is happening is not simply incidental or motivated by personal grievances, but expresses serious disagreement between state officials and business elites about which accumulation strategy should rule the day. Zuma���s repeated calls for ���radical economic transformation��� were a pushback against the perceived privileging of white and foreign capital in South Africa���s private sector. His crony-capitalist alternative offered routes for accumulation to the ���excluded��� in state-owned enterprises. Ramaphosa and his acolytes are best understood as longing for what can only be called, in their view, a more ���civilized��� or pure model of accumulation, one premised on the outdated assumption that markets and the state can be disentangled.

The DA has been imploding too. Styling itself as distinct from the ANC for its ���classically liberal��� values, in truth, it has always lacked any sophisticated ideological commitments. Instead, it relies on flimsy signifiers of what it is not���and for the most part, all they had to be was not the corrupt ANC to get enough votes. This method especially worked during Zuma���s presidency, and when the DA elected Mmusi Maimane as its first black leader in an ostensibly earnest attempt at racial transformation, his platitudinous charm and appeal to the Black middle class added to the flourish. Now, Maimane has unceremoniously resigned from that role, only after the anti-poor, anti-immigrant and Michael Bloombergesque Mayor of Johannesburg, Herman Mashaba, did the same. Their complaint? The return of the repressed in the person of former DA leader and strongwoman, Helen Zille. Having reinserted herself as the locus of power, she���s leading a crusade to remake the DA into a culture-war fighting force, using old rightwing dog whistles as new tricks���the DA is now not the ANC, not corrupt, and crucially, not Black.

Make no mistake, both of these parties are the faces of the neoliberal establishment. Their differences on affirmative action and land reform, which increasingly harden as a tepid distinguishing tool, are nothing more than a recourse to the realm of culture and identity as a smokescreen for their lack of political legitimacy. Like most center parties staring down political unviability, instead of breaking with the status quo, they are opting to present more of the same by hustling together shaky alliances with otherwise hostile political forces. The DA started with the seemingly left-wing Economic Freedom Fighters to take power in Johannesburg and Pretoria���this alliance has collapsed, and since the Afrikaner Nationalist Freedom Front Plus��� minor-but-not-insignificant increase in vote share last year, the DA has been making overtures to them. The ANC has tried with the EFF, but they remain intransigent. Ramaphosa reportedly set out to assemble a ���government of national unity��� with some of their high profile members in key cabinet positions, but had to settle for Patricia de Lille, a former DA member with a controversial floor-crossing past who scraped two seats in Parliament with her new feeble formation, ���GOOD.���

Otherwise, where it matters, both the ANC and DA are marching stubbornly with an austerity neoliberalism future. The DA praised Tito Mboweni���s Medium Term Budget Policy Statement in October which announced sweeping spending cuts���Mboweni quoted from the Bible, and preached that ���Whoever sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and whoever sows generously will also reap generously.���

Where is the South African Left in all this? First, the notion that the EFF is left-wing must at last be firmly dispelled. For some time, the EFF captured the imagination of the South African Left. After being expelled from the ANC and formerly leading its Youth League, Julius Malema launched the party in 2013, on the site of the Marikana massacre. An outgrowth of the ANC���s disappearing hegemony, the EFF���s vibrant and combative energy in Parliament was initially commended as a useful way of bringing Zuma to book over his use of state funds to upgrade his personal homestead. Their radical posture���officially being ���Marxist-Leninist-Fanonian������has attracted scores of admirers, including small portions of the working class and disgruntled youth, particularly university students (the EFF controls the Student Representative Council���s on a number of campuses) and young, downwardly-mobile members of the professional managerial class. Thus, since its inception, it is the only major political party that has exhibited growth in electoral support, and as noted above, has played the role of kingmaker where the DA or ANC have been unable to secure parliamentary majorities.

Presently in its early maturity, the party has become too loaded with contradictions for it to be considered left-wing in any credible sense, both in ideology and practice. Besides its lack of internal democracy and the cult of personality surrounding Malema, some of the EFF���s lead figures have been embroiled in various financial scandals including municipal tender fraud and the ransacking of a mutual bank primarily serving informal friendly societies. Additionally, the party���s advent was funded by notorious South African cigarette smugglers who enjoy a close relationship to Malema; this, despite him disparaging the influence of ���white monopoly capital��� in South African politics. Displeased with the media���s interest in its dodgy dealings, the EFF prohibited a group of investigative journalists from attending and covering its most recent elective congress in December.

Although breaking with the tenets of neoliberalism, the EFF are more of an economic nationalist front than left. Suspicious of globalization and the dominance of foreign capital, it seeks to lead an industrial revival that generates capital formation opportunities for local business elites and jobs for the domestic working class through initiatives like special economic zones���in so doing, establishing their own version of a state-led, indigenous capitalism. Their politics are driven more by retribution than redistribution, evident in their fetish of ���the land question��� as being the most decisive in South African politics. For them, land expropriation is not chiefly a means to advance an egalitarian politics to empower South Africa���s rural population (the EFF still supports mineral extractivism), but to divide the country into historically dispossessed ���African natives,��� versus everyone else who are ���settlers,��� in order to set the record straight of who does and doesn���t belong.

The EFF���s crude nativism and race essentialism make a mockery of the radical, anti-racist thinkers it cynically deploys, from Marx to Fanon. Underneath all that revolutionary chic, the EFF project is not about deepening democracy, but about reclaiming a perceived loss of national sovereignty against what are deemed culturally foreign forces���almost as if to say, in lockstep with Zuma���s RET bloc that, ���We don���t actually mind that capitalism inevitably concentrates wealth in the hands of the few, but we do mind that this few are predominantly White and Indian.���

No truly class-rooted political force exists in South Africa today. Politics in the interregnum are located at an awkward place where as parties decline, the evisceration of other sites of political struggle and mass collective organizations such as trade unions, nonetheless make them important avenues of struggle, if not as shadows of their former selves. This is the void that recent experiments in left populism aim to fill, from Corbynism in the Labour Party, Podemos in Spain and the Sanders moment in the States. There is no such equivalent in South Africa today, and where anything came close, it failed so disastrously in ways that gesture towards the limits of a politics that is class-focused, but not class-rooted. As the British trade unionist Andrew Murray explains, this means a politics that, ���While it places issues of social inequality and global economic power front and center, it neither emerges from the organic institutions of the class-in-itself nor advances the socialist perspective of the class-for-itself.���

In 2013, the largest union in South Africa, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) broke away from the ANC���s Tripartite Alliance, of which COSATU and the moribund South African Communist Party are a part. At once, it resolved to form a new working class party. It spearheaded the formation of the United Front, a wide coalition of workers, the unemployed, rural people, civic organizations, academics and activists that would unite workplace and community struggles and lay the groundwork for a worker���s party. The project stalled, and feeling that it had been taken over by NGOs, NUMSA left, throwing the UF into quiet death. In 2017, NUMSA then also played a hand in the creation of the South African Federation of Trade Unions so as to displace COSATU as South Africa���s largest trade union confederation. Right then, the sense that a new party was on the horizon began to lift a second time, and at the end of 2018, the Socialist and Revolutionary Workers Party held its pre-launch convention with delegates drawn primarily from SAFTU.

Inexplicably, its official launch only happened in March 2019���two months before the May general election. Foreseeably, charismatic NUMSA general-secretary Irvin Jim was paraded forward as its leader, and it began the rushed work of campaigning to contest the elections. To be honest, the SRWP didn���t work all that hard. It advanced its campaign mainly on social media and quickly put together a threadbare manifesto of outdated, Bolshevik-inspired slogans. Yet, unlike the many ���pop-up populisms��� faltering today, the SRWP saw itself as a party operating with a concrete base by having links to NUMSA���s 339,000 members. In addition, it won the endorsement of Abahlali baseMjondolo, a shack-dweller���s movement fighting against evictions and for public housing based in KwaZulu Natal and with 50��000 members. In the end, SAFTU would not support the SRWP, with general-secretary Zwelinzima Vavi citing that the party���s decision to contest the elections was not discussed with them. Yet, this did not deter the SRWP, and a mood of triumph punctuated its online posts in the days before the election.

The defeat was nothing short of humiliating. The SRWP only amassed 25,000 votes, below the threshold required to obtain at least one seat Parliament. In the embarrassment of defeat, the SRWP was quick to absolve itself of blame, instead alleging electoral fraud and pointing to the rise of the conservative right. Ultimately, the SRWP���s character was more vanguardist than left populist. Its top-down treatment of the working class starved them of agency and reduced them to instruments to be shepherded towards an electoral objective that never took seriously the difficulty of state transformation, and unwilling to confront the extent of disorganization haunting the working class today. Ignorantly, it stuck to an exhausted party form made obsolete by 30 years of neoliberal onslaught. Unlike during Apartheid, where masses were active and organized, today���s politics are that of a swarm���and as political theorist Anton Jager puts it: ���Swarms roam, rage, scream, only to end in monotonous drones.��� It is a phenomenon of party politics without parties, of politicization without the political.

Political scientist Rune M��ller Stahl predicts that in periods of interregnum, the space for democratic politics and contestation will only be further crowded out by forces wanting to continue the neoliberal program. Late last year, Ramaphosa signed into law the Traditional and Khoisan Leadership Act, which places rural South Africans, who are the two-thirds of the population, under tighter control by traditional leaders, allowing them to enter into commercial agreements with third parties without first acquiring the consent of the communities whose land and livelihoods will be affected. It���ll undoubtedly be challenged, but the move���s embrace of colonial vestiges is striking for its bold-faced disregard for the enormous strides rural South Africans have made in resisting destructive mining projects in their communities.

The trouble with periods of crisis and confusion is that they can also devolve into a regressive actionism that goes for quick fix solutions in addressing deep-seated problems. The Marxist culture critic Theodor Adorno viewed this as ���incomparably closer to oppression than the thought that catches its breath.��� This was the case when the military rolled into the Cape Flats to curb the tyranny of organized crime and gang violence, and as South Africans started to call for a state of emergency to deal with gender-based violence. Recently, a new common sense is developing that insists key sectors should be declared essential and workers within them prevented from disruptive strike action. This catastrophism only serves as a handmaiden for more authoritarianism. Meanwhile, core institutions of representative democracy here have become increasingly incapable of fulfilling their functions. Once praised for its fearless investigations into state-wide corruption, the Office of the Public Protector is regularly in the news for the wrong reasons. Busisiwe Mkhwebane���s tenure has been marred by controversy for court judgments handed against her after investigations into many high ranking politicians, including Ramaphosa, were done sloppily���prompting many to these disputes as nothing more than a microcosm of the ANC���s factional battles.

In these moments of profound despair and disorganization, the South African left has no Sanders or Corbyn to rally behind and provide a desperately needed awakening. But, Corbyn���s recent defeat and the political wilderness that its thrown the Labour Party into perhaps indicates that this is not so terrible a lack. In fact, we���ve been roaming the wilderness for a long time now, and the left has no option but to make an intrinsic transformation if it has any hopes of rebuilding.

South African writer and historian��(and Africa Is a Country Contributing Editor) Benjamin Fogel correctly points out two components to this. First, doing the intellectual labour of crafting a new vision for South Africa���s future that confronts the political, social and ecological crises before us. This vision has to champion what philosopher Andre Gorz called a ���socialist strategy of progressive reforms��� which have the effect of restructuring social life by democratizing the workplace, creating non-marketized forms of social production and reproduction, and enlarging the room for more class politics, not less. In this regard there are plenty of historical precedents from which to draw inspiration and extend, including the findings of the MERG.

However, this all depends on having a strong enough social movement capable of not only seizing power, but ensuring that despite also having to manage a capitalist state in crisis if successful, it maintains a strong connection to popular forces maintains a transformative agenda with an eye to transcending capitalism. Working class hegemony of the most expansive kind has to be built from below, and this is in the form of both a new organization and an organization of a new type, one beyond the anachronistic organizational forms of the old left, and the leaderless and horizontalist ones of the new. What this looks like is difficult to prescribe. It suffices to say that either way, the task of reviving sorely lacking institutions that are entrenched in working class life, such as mass worker education programs and socialist schools, is integral. Admittedly, this has been happening in pockets in some places. But, they are largely NGO-led, fractured and confined to special interest projects at the behest of donors and budget constraints, geared towards creating new legions of professional activists to sustain the legacy of this or that organization instead of constructing broader class hegemony. This, and the gatekeeping tendencies that come with it, have to be overcome.

The world is in no revolutionary situation, but it is one that presents many prospects for the left. Chileans are in the streets chanting: ���Chile has woken and it will not sleep again.��� A latecomer once more, it is time for South Africa to wake up as well. The final question then, is not how, or where, or when neoliberalism will end, but if it will. As Stahl reminds us, ���If we should draw one lesson from history, it is the astonishing ability of capitalism to overcome crisis, transform itself and emerge in new institutional forms.��� On the other hand, capitalism has no natural tendency towards stability, and so interregnums can last indefinitely without resolution. In circumstances not of our own choosing, history can still be made, but it is up to us to birth the new.

Before his passing, on August 31 last year, the radical sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein wrote his final commentary in July. Titled ���This is the end; this is the beginning,��� it ends with a passage that bears constant repeating in the new decade:

So, the world might go down further by-paths. Or it may not. I have indicated in the past that I thought the crucial struggle was a class struggle, using class in a very broadly defined sense. What those who will be alive in the future can do is struggle with themselves so this change may be a real one. I still think that and therefore I think there is a 50-50 chance that we���ll make it to transformatory change, but only 50-50.

The time for defeatism is over. The left must take its chances.

January 18, 2020

Fela enshrined

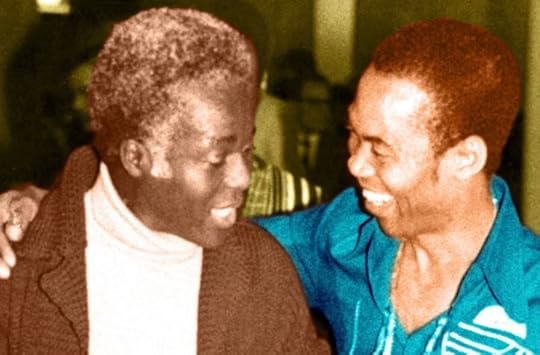

Carlos Moore and Fela Kuti. Still from film My Friend Fela.

Twenty-two years after his death of complications from AIDS, Fela Kuti stands as one of the most documented, analyzed, and celebrated African artists in any medium. There have been at least seven books in English and three feature-length film documentaries, Music is the Weapon, Finding Fela and now, My Friend Fela. In 2003, the New Museum staged an exhibition of contemporary artworks inspired by the artist (The Art and Legacy of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti), and 2008 brought Bill T. Jones and Jim Lewis���s Broadway musical, Fela! (whose production is documented in Finding Fela). To be sure, Fela deserves this volume of attention, both as stylistic innovator, whose Afrobeat funk changed global pop music, and as fiery activist���the ���Black President��� who continues to inspire insurgent movements by the likes of Uganda���s Bobi Wine. Yet, as the Fela retrospectives pile up, one wonders what new perspective on the man and his times each new contribution can possibly bring.

As its title suggests, Carlos Moore���s film My Friend Fela is a highly personal account, meditating not only on the artist, but also on the intersection of Moore���s own eventful life and Kuti���s. Born in 1942 in Cuba to Jamaican parents, Moore moved to New York and immersed himself, under Maya Angelou���s tutelage, in the Black liberation struggle. He eventually became one of Malcolm X���s closest assistants in charge of security and logistics���his ���everything man,��� in Moore���s words. In 1961, following the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, Moore organized a groundbreaking black sit-in protest at a UN Security Council session. Footage of this event appears in the film, along with rare footage of Malcolm X in Paris.

After Malcolm���s death, Moore met Fela and the two bonded over their shared commitment to Black radical politics, with the more politically seasoned Moore filling Kuti in on what he was eager to learn. In 1982, Moore published, in French, Fela: This Bitch of a Life, the first biography of the artist, which, in various translations, did a great deal to raise global awareness of Kuti. In 2010, Moore made news when he filed a lawsuit against ���Fela!��� the musical, claiming that substance from his book had been used without his consent or knowledge. In 2012, a settlement was reached: all future promotional materials for the production would include the phrase ���inspired by Fela: This Bitch of a Life by Carlos Moore.���

In his new film, Moore vows to ���set the record straight��� on Fela: the Nigerian was no mere ���cultural icon��� or ���ghetto hero,��� but a man who ���challenged the whole moral basis of the society in which he was involved.��� It is not clear whom exactly Moore is defending Kuti���s reputation against���most of what is said today about the artist/activist seems positive, even adulatory. Indeed, given Fela���s increasingly legendary status, I for one welcome depictions of the artist that take his complex, flawed personality into account along with his genius.

One valuable recent contribution in this vein is the 2013 autobiography by Tony Allen, Fela���s drummer and the most important co-inventor of the Afrobeat style (co-written with Michael E. Veal). In his book, Allen expresses deep admiration for Fela the artist and visionary, yet he does not neglect to recall his frustration with Fela���s ���politics business,��� which ���sometimes ��� took the whole night��� to the displeasure of audiences and his fellow performers. For Allen, Fela���s political propensities were a mixed blessing: on the one hand the Black President was bravely saying things that needed to be said; on the other, it was sometimes impossible to disentangle Fela���s anti-government tirades from what Allen calls the ���ego-tripping��� side of his personality. Whether or not one agrees with Allen, his measured, multifaceted assessment of Fela the man is honest and historically valuable.

Moore allows a complex image of Fela the man to appear on screen, but there are times when his mission to elevate Fela and defend him against unnamed critics keeps such a nuanced portrait from emerging. This is most pronounced in Moore���s interview with Sandra Iszadore (formerly Sandra Smith). Iszadore, whom Fela met in California when he first traveled to the United States in 1969, powerfully kindled the young Nigerian���s political awakening, in much same way that Angelou kindled Moore���s. Her appearance in My Friend Fela is one of this documentary���s unique assets, yet it is marred by Moore���s leading and unnecessarily combative interview approach. He presses Iszadore hard on her decision not to join Fela���s polygamous household in Lagos. Choosing her words carefully and with some reluctance, Iszadora explains ���I chose not to be a part of the harem.��� Moore then sternly corrects her: ���No. Polygamy is not a harem! And that���s why I say poly-conjugality.��� Whatever his views on Fela���s polygamy, Moore might have shown more deference to Iszidora���s depiction of what was, after all, her own experience. Rather than trying to defend Fela���s actions and attitudes with words like ���poly-conjugality,��� Moore could have listened receptively to what this key person in Fela���s life had to say. The interview remains informative, and some viewers may be less bothered by Moore���s domination of the frame; ���My Friend Fela��� is, after all, a film which purposefully and unapologetically puts its own director front and center.

This is as much a film about Moore as it is a film about Fela, and viewers will likely appreciate the film to the degree that they are interested in Moore (as many likely will be, given his rich history as an activist and writer). There is not much new, unseen footage of Fela here, and the film draws heavily on Jean-Jacques Flori and Stephen Tchal-Gadjieff���s indispensable 1982 documentary Fela: Music is the Weapon for material. Viewers who already know that film may find themselves waiting impatiently for unfamiliar shots to appear. Given the title, one might expect a narrative focus on an evolving and complex friendship between Moore and Kuti, with their two oversized, uncompromising artistic personalities. Werner Herzog did this with great success in his similarly titled My Best Fiend, about himself and Klaus Kinski. Moore and Kuti���s actual personal relationship, however, seems not to have been eventful enough to serve as the central narrative axis for this film.

My Friend Fela is more about Moore���s re-imagination and theorization of two parallel and intersecting black lives in a time of political and artistic ferment, one beginning in Cuba, the other in Nigeria���both finding new meaning in the struggles of the United States. Taken as such, it makes for rewarding viewing.

January 17, 2020

The short, white woman with a South African accent

Urdang, left, with Jennifer Davis at the Women's March for the Equal Rights Amendment in 1976. Image credit Suzette Abbott.

On October 15th 2019, exactly two months before her 86th birthday, Jennifer Davis passed away. Towards the end of her two-week visit to my home in Montclair, New Jersey, she had a massive brain hemorrhage. She remained unconscious until, without life support, she passed away six days later in hospice.

It is hard, always, to lose a close friend. She was one of my very closest, closer than any sister, someone I learned from, admired fervently, argued with, and was at times intimidated by for her brain and political acumen. She was a friend in the truest sense of the word, but I lost more than a friend, more than her sisterhood, I lost an anchor.

Jennifer was older than me by 10 years. But, unlike my family, her family had longevity. Her father Seymour, a highly respected pediatrician, lived until 95. Her mother Friedel, a German who trained as a pharmacist, escaped the holocaust by marrying him and immigrating to South Africa in the early 1930s. She lived to 102. I had assumed that Jen would outlive me.

We both emigrated from South Africa to New York City in the late 1960s. In 1968 we met at the wedding of a mutual South African friend. She entered the small living room of our friend���s apartment, her two young children in tow, somehow changing the energy in the room as everyone responded to her. She was scarcely more than five foot to my five foot nine, her brown hair long and straight, a lovely smile on her face.

Jennifer hadn���t wanted to leave South Africa. Her activism began in high school in the late 1940s. At university she joined the Unity Movement, one of South Africa���s liberation organizations. Her activism and commitment to the struggle gained momentum and banning, and incarceration loomed for both her and her husband, Mike Davis (since divorced), a lawyer handling political cases. Because of their work, they were targets of the security police. They had little option but to leave. She also harbored concerns about raising her children under the dense shadow of apartheid. Five-year-old Sandy came home from school one day and asked if Andrew, a close African friend, was a bad person. ���Not at all,��� Jen assured her. ���Why do you ask, darling?���

���The teacher told us today to be careful of black people because they are bad people.��� Jen knew then that it would be impossible to protect Sandy or four-year-old Mark from the influences of apartheid and the bigoted thinking that came with it.

That wedding was the starting moment of our friendship and camaraderie. Jennifer was then Research Director of the American Committee on Africa��(ACOA) and we both were members of the Southern African Magazine Collective. Beginning in 1972, a group of close friends formed a women���s group. Jen and I were founding members. At the time, women���s conscious-raising groups were blossoming like daffodils in the spring. Most faded over time. Ours didn���t. For 47 years, a core of five have continued to meet���three South Africans, two Americans���all involved in the anti-apartheid and solidarity movements. Recently, for the first time, we met without her.

When Jen died, I lost someone who channeled me into better decisions about life and politics, and her sharp editing eye kept my writing from flying off into directions that would not have served it. She was caring, loving, principled. She never allowed a sloppy thought or careless utterance to go unchallenged. With her I was more considered, more insightful. She expected nothing less and could show irritation when she thought I did not reach to her exacting standards.

Those who worked for her have similar memories. Jennifer became the Executive Director of the American Committee on Africa and of The Africa Fund in 1981, and remained there until her retirement in 2000. Jim Cason was ACOA Associate Director at a critical time in the 1980s. He remembers: ���Jennifer didn���t just give me her impressions, but listened carefully and cared about what I had to say. As a young person coming into the progressive movement, this was very important to me. And unusual.��� It wasn���t just that she listened, people felt listened to. ���It was a rare skill,��� he added. She also always insisted on asking, ���What is the goal here?�����as they strategized. She understood the importance of this clarity before moving on. He has carried over into his own work on strategic advocacy for the Friends Committee on National Legislation.

Prexy Nesbitt, a close friend and fellow activist, began to work with ACOA as its first Field Staff in Chicago in early 1970, soon after he returned from Tanzania where he worked with Frelimo as it fought its war of liberation against colonial rule in Mozambique. Among his many fond memories of their friendship over five decades is the way Jennifer interacted with the African-American community. He accompanied her to Reverend Wyatt T. Walker���s Canaan Baptist Church of Christ in Harlem. Reverend Walker, a prominent leader in the African-American community in Harlem and beyond, was for a time the Chair of the American Committee on Africa and a founder and leader of ACOA���s Religious Action Network aimed at helping to unify the efforts of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim congregations to end apartheid. A strong supporter of Jennifer and her work, he invited her to address his congregation from the pulpit on a number of occasions. Skeptical at first, the congregation was soon responding positively to this short, white woman with a South African accent. Or on another occasion, holding her own with Jesse Jackson, the forceful civil rights activist and prominent leader. At one of his events, Prexy recalled: ���There she was, tiny in stature, barely peeking over the mic. Her content was so clear that she soon won the audience over. Her size probably helped her!���

Canon Fred Williams, another African-American religious leader in Harlem, and member of the board of ACOA and RAN, would toast her at her retirement in 2000: ���Here was this Jewish woman who made it possible for ACOA���s Religious Action Network to do its work���this coalition of primarily black, male clergy and their churches.��� Referring to Jennifer���s tendency to be reserved and self-effacing, he continued: ���The public Jennifer is so reliable���the one to look more deeply, to insist on principle, to keep focused even in the face of terrible opposition.��� As Prexy put it, ���She was non-stoppable when she decided, come hell or high water, to do something, to follow her instincts and her principles, and that often meant going into high water.���

Then there was Dumisani Kumalo. A South African political exile and journalist, he joined forces with Jen at ACOA just as the divestment movement was gaining force. Her work in the public arena as a white South African was at times contentious, given the tensions and conflicts between different groupings of activists. She appreciated Dumisani���s presence and support. In an interview with No Easy Victories, she said, “I developed, I think, a fair amount of credibility, but to have ��� Dumisani [with me] meant that me being a ���white lady��� didn���t matter.”

Dumisani and Jennifer were a formidable team. Dumisani, with a strong personality and a rich sense of humor that came with an infectious laugh that lurked behind his serious work, had no ego and cared deeply about the same issues as Jen. They were the perfect match, balancing off their polar opposites in personality and background. As serious and reserved, even shy as Jen could be in public situations, Dumisani always seemed to be enjoying himself. He held audiences in his thrall���whether local, state, or national legislators, religious groups of all faiths, organizations of all political persuasions, or campus activists. Together���Jennifer, the strategist and compelling speaker who had a way of making apartheid understandable to even the most ignorant, and Dumisani with his charisma, charm, and ability to convince even the most die-hard conservative of the evils of the system���they helped forge a divestment movement that would have a major impact on how Americans viewed apartheid and the downfall of apartheid itself. (Dumisani Kumalo was appointed the first Ambassador to the United Nations of the new South Africa after 1994. He too died in 2019.)

Would apartheid have held its ground longer than it did without the US divestment movement and the subsequent Sanctions Act? We do know that sanctions had a real, effective impact on the economy and hastened apartheid���s demise. We also know that without Jennifer���s brilliance as a strategist, her principled approach to her political work, her innovative ideas, and, like a pug at a bone, her insistence to never gave up or gave in, it may not have worked either. Although ACOA was not alone in pushing the divestment campaign, her quiet, persistent activism in defining its purpose and its achievable goals was essential. While she, like others, saw the importance of changing the minds of elected officials and put considerable effort in that form of education and protest, she insisted that unless the grass roots were mobilized among their constituents, they would happily continue as business as usual. While she gave testimony at hearings at the UN and Congress, while she cajoled heads of corporations investing in South Africa to desist, while she confronted those with power to change their ways, she understood that real change would only come through pressure from below.

The ACOA developed close relationships with many organizations and communities���trade unions, students at colleges and universities, state and city councils, faith-based institutions, community groups, human rights coalitions���and had dedicated staff members organizing among them. Particular targets were the billion-dollar funds of state and city governments, often held in public employee pension funds.

By the time I joined the staff of ACOA and The Africa Fund as Research Director at the end of 1984, 40 US companies had withdrawn their investments from South Africa; another 50 would do so the following year. By the beginning of 1985, Citibank had refused to make any new loans, and Chase Manhattan refused to roll over its short-term loans. From 1982 to 1985, the divestment campaign drove over $4 billion of US Capital investment of out South Africa. This combined to create a major financial crisis in South Africa. At ACOA, Richard Knight kept track of it all, publicizing the results on a regular basis at a time well before the advent of social media.

Meanwhile, US President Ronald Reagan continued to argue for ���constructive engagement.��� Sanctions would only hurt black South Africans he claimed; change could only happen through dialogue. Those youth in South Africa trying to storm South Africa���s Bastille had given up ���dialogue��� a long time before. All they experienced was increased violence and repression; increased imprisonment and death.

Reagan had his comeuppance in 1986 when Congress overrode his veto of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, which banned all new US trade and investment in apartheid. It is important to remember���as incredible as it might seem in today���s political climate���that enough members of the Republican-controlled Senate broke from their President to override his veto. There was something of a pincer movement that pressured Congress. While critical organizing was being undertaken with the Congressional Black Caucus and at the policy/leadership level, it was the grassroots activism that exerted the real pressure on members of Congress in their local communities who feared future elections if they did not respond to the demands of their constituents to ���do something��� about apartheid.

Jennifer���s apartment on Riverside Drive and West 86th Street, with its expansive view of the Hudson River, served as a hub for revolutionary traffic passing through New York. It provided a meeting space, and often a bed for representatives of the African liberation movements, as well as the South African Trade Unions and other anti-apartheid organizations. Seated on folding chairs and on the floor, we listened keenly, learning about the progress of their work and their regard for our solidarity work. We would leave reinvigorated. One such meeting changed the trajectory of my life. Sitting on the floor literally at the feet of Amilcar Cabral, leader of PAIGC, which was fighting for the liberation of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde from Portuguese colonialism, I drank in the words of this renowned theoretician, analyst, and influential thinker. Towards the end of his presentation he turned to the role of women in the revolution. “Women were fully engaged,” he said. “Needing little encouragement, they demanded an equal role with men in the movement.” This was the early 1970s, when heated debates were common-place among American women drawn to feminism, and here was a man articulating what we were grappling with. It was hard enough to dislodge patriarchy in the United States, could this evolution in a small African country achieve what we could only dream of?

Some months later, traveling in Africa shortly after he was assassinated, I was invited to visit the liberated areas of Guinea-Bissau as a journalist. I decided to gather material for a book on the role of women in Guinea-Bissau. I needed to write a synopsis for a prospective publisher. I nervously showed the draft to Jennifer. She was an incisive if formidable editor, if she declared it was bad, I���d be sunk. I waited while she read my draft. There was no point in searching her face for her reactions, she concentrated without expression. She reached the end, flipped back to the first page to reread sentences, and sat thoughtfully for a moment longer. She then pronounced it good, very good. She made a few small editing suggestions. I couldn���t have felt more relieved if I had aced a grueling exam. She was one of my strongest supporters throughout the process of writing the book, and beyond. In no small measure I have her to thank for the development of my writing career.

Gail Hovey worked with Jen as ACOA Research Director before I did in the early 1980s, and is one of our five-member women���s group. She and Jennifer went to South Africa in April 1994 as members of the US team of election observers of the first democratic elections. Their group was assigned to Empangeni and its environs in KwaZulu. Since the mid-1980���s violence between the Inkahta Freedom Party based in KwaZulu and the ANC had resulted in thousands of deaths. The violence sharply escalated in the weeks leading up to the election. The organizers wanted the group to be assigned to another area, away from potential violence at the polls, depriving voters of independent observers. Jennifer would have none of it. ���If the people are willing to risk their lives to vote,��� she insisted, ���they deserve to have observers.��� The location remained.

The public Jennifer is who she is remembered for. The private one, the friend, the sister, the comrade, is who I, and those who were close to her now mourn. As I mourn, I remember her feistiness. her unfailing commitment to her work, to her friends, to her family. Gail reflected:

Jennifer has been one of my closest friends for over 40 years, and I have to be reminded by the external world how phenomenal she was. Day by day she was so unpretentious. She was self-deprecating and would have denied being a hero. What a force she was. She would always say it was a joint effort. It was. But only because she was instrumental in making it that way.

Who was the woman behind Lumumba?

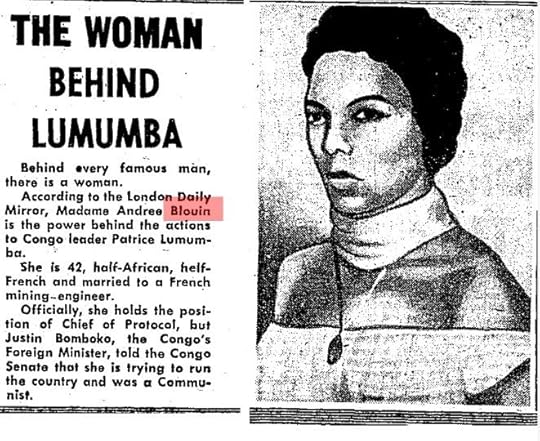

A screenshot from an article in the Baltimore Afro-American in 1961.

Fifty-nine years ago today, on January 17, 1961, Congolese prime minister and independence leader, Patrice Lumumba, was assassinated by firing squad. In the months leading up to his death, the world���s attention was riveted on the Congo as a crucial arena in which Cold War politics were to be played out. European and American media coverage of the ���Congo Crisis��� revealed a fascination with Lumumba and an attempt to cast him as an authoritarian ruler. The Guardian, for example, ran a headline describing ���Lumumba as a Congo ���King.������ The New York Times opted for the title of ���’Messiah’ in the Congo.������

Amid the non-stop international media coverage of Lumumba���s life, leadership, and death, one curious headline stands out for turning its spotlight onto an enigmatic figure adjacent to the Congolese leader.

Three months before the assassination that would rock the world and destabilize the movement toward decolonization in Africa, the Baltimore Afro-American ran a feature titled ���The Woman Behind Lumumba.��� The article itself was very short:

Behind every famous man there is a woman.

According to the London Daily Mirror, Madame Andree Blouin is the power behind the actions to Congo leader Patrice Lumumba.

She is 42, half-African, half French and married to a French mining-engineer.

Officially, she holds the position of Chief of Protocol, but Justin Bomboko, the Congo���s Foreign Minister, told the Congo Senate that she is trying to run the country and was a Communist.

Who was Andr��e Blouin? Was she really the woman behind Lumumba? The article���s four sentences do not tell us much about her. They do, however, speak volumes about the reasons for which politicians and the media viewed her as a suspicious and illegitimate presence in Lumumba���s government. And, even more importantly for us today, they offer lessons about the historically racialized and sexualized representations of women of color in politics.

Blouin was born in the Central African Republic in 1921 and spent her early years in an orphanage for ���mixed race��� children in Brazzaville in the French Congo. She later became an anticolonial activist in what was then the Belgian Congo. Her movements back and forth between French and Belgian territories gave her firsthand knowledge of the particular cruelties of each imperial power. While the Belgian practice of sequestering children born of Belgian fathers and Congolese mothers in orphanages has recently drawn attention, Blouin���s autobiography reveals her own experience with this practice of segregation and discrimination as a child in an orphanage for ���mixed race��� girls on the French side of the Congo River. Years later, when her two-year-old son, Ren��, was ill with malaria, the French colonial administration insisted that quinine medication was for Europeans only. A frantic Blouin pleaded with the mayor but he refused to grant her access to the life-saving medicine.��She had to watch her son die.

Blouin���s experiences of racism at the hands of French colonizers highlight the interlocking racial and gendered violence of colonialism. By separating her from her parents as a child and designating her an orphan, the colonial administration tried to erase her identity as a daughter. Later by causing the death of her infant son, colonial powers tried to exclude her from motherhood.

Blouin therefore came to political activism in the Belgian Congo armed with the insight gained from her intimate knowledge of colonial violence under French rule. She began her grassroots mobilization of women in the Belgian territory on the eve of independence in 1960 as an organizer for the Feminine Movement for African Solidarity. The organization���s charter outlined projects for women���s health, literacy, and their recognition as citizens of the emerging postcolonial nation. Her work was informed by the conviction that ���if she so chose, the woman could be the foremost instrument of independence.��� That year, Patrice Lumumba appointed her to the position of chief of protocol in his cabinet. Blouin was one of three members of Lumumba���s inner circle, working so closely with the Congolese prime minister that the press nicknamed them ���team Lumum-Blouin.���

Even as international media trained an obsessive lens onto Lumumba during his short tenure at the helm of an embattled Congo, Blouin too became an object of fascination. Yet, as the Baltimore Afro-American, citing the London Daily Mirror, shows, the media representation was couched in the same language of intertwined racialized and gendered discrimination that marked her life under colonial rule.

The article begins by relegating Blouin to the background of Lumumba���s government, the proverbial woman behind a powerful man. But that relegation also contains suspicion about her supposedly hidden agenda and manipulative role in this position. Blouin emerges as a mysterious shadowy figure pulling the strings of decolonial politics in the Congo.

To be ���behind��� Lumumba, then, is to occupy both a location of subordination and a position of power. But it is also clear that this power projected onto Blouin is fragile at best, because it is rooted in sexualized fears of women as exotic objects to be both desired and reviled. Thus, in an article about Blouin as a political figure, we find no mention of her activism to obtain a reform in colonial quinine laws, or her work towards increasing literacy and access to healthcare for Congolese women. We learn instead that she is ���half-African, half-French and married to a French mining engineer.��� Other newspaper articles about Blouin described her with even more exoticizing language. The Washington Post, for example, called her the ���Eartha Kittenish Clara Petacci of the Congo���s brief strong arm regime,��� likening her to African American actress Eartha Kitt and Mussolini���s mistress Clara Petacci. To liken someone to Eartha Kitt is far from an insult. But when wielded to make Blouin hyper-visible as an object of desire in the Western imaginary, the comparison becomes a way to elide her political activism.

A journalist once asked Blouin whether she was a Communist. She responded, ���Let small fools call me what they like. I am an African nationalist.��� The breakdown of her lineage into half and half, as in the Baltimore Afro-American���s coverage, is a gesture that was used many times to challenge Blouin���s authenticity. Neither French enough to benefit from the Europeans-only quinine card, nor African enough to be fully embraced as a pan-Africanist, public representations of Blouin sought to delegitimize her work by questioning her racial, national and even continental affiliations.

Negative representations of Blouin in the media became commonplace throughout her time in office. She reports that Lumumba acknowledged the gendered nature of these portrayals: ���Our enemies attack her all the time. Not for what she���s done, but simply because she���s a woman, and she���s there, in the thick of it.���

When Lumumba was assassinated in 1960, Blouin likewise became a target. Her daughter Eve recounts that her mother, who she remembers as ���a pivotal figure [and] freedom fighter in Africa,��� was sentenced to death. She fled the Congo, ultimately living in exile in Paris until her death in 1986.

Today, Andr��e Blouin remains an enigmatic figure, relatively unknown in historical narratives about the long and painful march towards Congolese independence. She is elusive, not because she was the shadowy manipulator of Lumumba���s leadership, but rather because like many of the African women who were engaged in anticolonial activism, she remains on the periphery of historical narratives that privilege the so-called founding fathers of African independence. 59 years after Lumumba���s death, it is fitting to remember Andr��e Blouin too, and with her the many women who lived and died for African liberation.

January 16, 2020

The pitfalls of symbolic decolonization

Slave holding room, Elmina Castle, Ghana. Image credit Kevin Thai via Flickr CC.

In January of 2019, I traveled to Ghana to visit slave castles and forts for the book I am currently writing on the relationship between Africans and Black Americans, Somewhere between Black and African: A Biography of my Skin. I visited Keta, a coastal town that Maya Angelou in All God���s Children Need Traveling Shoes described as melancholic���you see this was once a village from where slaves were kidnapped.

There is a question we do not ask often enough���what happened to villages and towns in Africa after slave traders started disappearing their populations? The slaves had to come from somewhere���what happened to those communities that were raided for their mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers, aunts and uncles? One of the answers is inherited psychological trauma and inherited poverty.

Conversely, what happened to the towns and cities where the slaves were brought for trade and labor? Shortly after leaving Keta, I visited Bristol, England. Bristol rises from the ocean to hills that are more like ridges. The river front where the slave boats docked is now busy with commercial ships and tourist boats. Along the waterfront all kinds of bars and bohemian like restaurants proliferate. Keta is a town wrapped in a blanket of melancholia, while in Bristol its bohemian happy excess.

To be sure, in Bristol there are attempts at remembering history and decolonization. For example, Edward Colston was a major slave trader who brought wealth to Bristol���streets and buildings are named after him. The effort to get them renamed is underway. As England tries to grapple with its own slavery legacy, in the US monuments celebrating the purveyors of slavery are being reluctantly toppled.

As an aside, in a somewhat strange move, Evanston, Illinois, the town I was born in, recently legalized marijuana���the revenue raised from taxes will go ���will be used for investment into the African American community and to make amends for racial inequalities.���

Universities are also reckoning with the past. For example, debt ridden Georgetown University sold 272 slaves owned by Jesuit priests in order to stay afloat. As part of its reckoning, the university now offers free tuition to the decedents of those sold, and the students recently voted to raise their tuition by $27.20 as a form reparation. That Jesuit priests owned slaves should not come as a surprise���every slave castle I visited had a church in its own compound. In Elmina and Cape Coast the church was built directly above slave dungeons. The pious white Christians would pour water through the cracks in the wooden floor to ease the thirst and heat. If there is one institution in dire need of decolonization, it is the church.

But here is the question. Consider all the unresolved historical inequalities where slavery becomes indentured servitude as Indians are imported into British colonies, colonialism becomes neocolonialism, and neo-colonialism opens up to unequal globalization. Also consider the inherited trauma still suffered by comminutes all over the world that have been, generation after generation, at the brunt end of global exploitation. Can what we in the West are calling decolonization in philosophical and material terms, really address historical inequalities?

Or to put it differently: how does renaming the streets of Bristol speak, in real terms, to towns like Keta still reeling from slavery? Or countries like the Congo where you can draw a straight line from King Leopold, Belgium slavery and colonialism, the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the continued exploitation of its resources and consequent wars that have left millions of people dead? What do we with these sedimented oppressions?

I am not asking for ideological purity or some dogmatic goal. If for Fanon, ���the battle against colonialism does not run straight away along the lines of nationalism��� decolonization cannot run along the straight lines of conscientious liberalism. That is the sort of liberalism whose sincerity is severely undermined by its insistence on being ahistorical. But there are some fundamentals, some basic truths, some basic laws of decolonization that we have to follow if we are to move from symbolic decolonization to real philosophical and material decolonization.

Symbolic decolonization is useful, but it is also useless without material decolonization. The point of decolonizing the mind has always been in the service of material decolonization, in the same way that black consciousness in South Africa was not an end in itself but a necessary step in the struggle against apartheid.

Therefore, yes, let us decolonize the universities but let us also make sure that they are paying their fair share of taxes in the towns and countries they are in. Rename the streets, but also struggle for economic justice���that means calling for redistribution of wealth.

Steve Biko when asked about a post-Apartheid future argued that ���[t]here is no running away from the fact that now in South Africa there is such an ill distribution of wealth that any form of political freedom which does not touch on the proper distribution of wealth will be meaningless.��� Decolonization that does not address economic inequality will be meaningless.

We should also acknowledge that decolonization in the West does not work unless it addresses African towns and peoples that still suffer from the effects of slavery/colonization and unequal globalization.

All in all, decolonization should as a matter of principle be in the service of ending exploitation and its legacies.

In short, decolonization achieves nothing unless it is first and foremost a revolutionary act.

Opening remarks delivered at the Writers Unlimited International Literature Festival The Hague, January 17th, 2020.

January 15, 2020

Finding a way through the deluge in Zimbabwe

President Cyril Ramaphosa attending dinner hosted in his honor by President Emmerson Mnangagwa. Image credit the Government of South Africa via Flickr CC.

The euphoria that marked the end of Robert Mugabe���s stay in power in the November 2017 coup quickly dissipated in the aftermath of these events. The resurgence of authoritarian politics in the form of the post-2018 election violence and the repression of opposition and civic dissent in January, August and November 2019, marked the predictable path of the former president���s legacy. The post-2017 regime of Emmerson Mnangagwa quickly slipped into the regressive forms of political rule that have defined the multi-layered Zimbabwean crisis since the late 1990s.

The much-proclaimed pronouncements on political and economic reform, adherence to constitutionalism, the respect for human rights and political pluralism, international re-engagement and the overall promise of a ���new dispensation,��� were quickly discarded. The tiresome political apparel of domestic repression was easily re-appropriated and paraded once again before the Zimbabwean citizenry.

The indicators of the economic catastrophe underway in Zimbabwe are well-known. With about 94% of the working population now fighting for survival in the informal sector, this figure represents the massive loss of formal employment in the post-1980 period. The country once again faces a surging inflationary spiral with the latter set to reach an average level of about 250% in 2019, according to economist Tony Hawkins.

This inflationary cycle has been driven by a combination of unsustainable state expenditure, with an estimated budgetary deficit of ZW$5.2 billion in 2019, in an economy whose production levels have sunk below the levels at independence, and in which there is little or no articulation between the central components of agriculture, mining, and manufacturing. This fiscal deficit has been financed for the most part through domestic loans from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe and commercial banks, in the form of increasingly worthless treasury bonds.

The result has been a rapid loss of value of the official Zimbabwe dollar, which was returned to circulation after the multi-currency approach was abandoned in June 2019. The value of the fantasy currency dropped from a purported 1:1 at its inception to its current value of about 1:15 at the interbank market rate, and 21:1 on the parallel market.

When this inflationary crisis is combined with increasing poverty levels, the disastrous condition of the health and education sectors, an energy crisis that has resulted in 18-hour electricity blackouts, fuel shortages, major water shortages, and the fact that the World Food Program (WFP) has had to arrange for 240,000 tonnes of food aid for approximately 4,1 million Zimbabwean citizens, the country clearly faces a major crisis of social reproduction.

In response to the growing precarity of their livelihoods and the broader crisis of social reproduction, trade unions responded through strike action. In setting out their recourse to strike action various unions described the desperate, incapacitated state of their membership.

Such declarations of incapacitation have become the common refrain of both public and private sector workers as they seek redress for the demands. These desperate conditions of service also pertained in the security sector. In an admission to the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Defense and Home Affairs in 2019, it was reported that the morale of soldiers and police forces had hit rock bottom due to a shortage of food and uniforms.

The result of these demands was a steady growth of strike action in the public sector. For much of 2019, public sector workers, including doctors, specialist doctors from the Senior Hospital Doctors Association (SHDA), nurses, teachers, air traffic controllers, and other civil servants have either been on strike or threatened strike action. Even the Apex Council, hitherto always considered a body close to the state and ruling party, threatened in July 2019, ���to paralyze government operations if our demands are not taken seriously.���

With the public sector representing the largest part of the formal sector workforce in the economy, the importance of strikes should not be underestimated. In 1996, the public service strike was the largest labor action in the post-1980 period. It brought much of the state to a halt and strengthened ties between the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions and the public sector unions. Significantly, the two-week strike in 1996, by more than 70��000 workers, was also ignited by health workers.

In the context of politics in 2019 this public sector strike is already adding to the legitimacy and capacity issues of the Mnangagwa regime. This is because every attempt to increase the salaries of the public sector workers has been rapidly eroded by the central failure of the regime to deal with issues around employment creation, new investment and expanded productivity.

These policy deficits have, in turn, created the conditions for the inflationary spiral and currency depreciation that, under current conditions, will persistently negate any wage increases and reproduce the strike wave. These challenges have been exacerbated by the deeply embedded corruption in the state. This was exemplified by the US$2,8 billion from the command agriculture subsidies that has not been accounted for, and the gross irregularities in the accounting of several parastatals as reported by the 2019 Report of the Auditor-General. Altogether, between 2015 and 2018, over US$9 billion in unauthorized expenditure was reported.

The response of the state to the strikes has been predictably violent and repressive. A report by the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum in 2019 observed that overall violence has increased since the November 2017 coup. This includes an increase in abductions, arrests. armed clashes, attacks, looting/property destruction, mob violence, sexual violence, and violence against citizens. The report also warned of the increase in the involvement of citizens in violence indicating a marked growth in the danger of civil unrest. The deteriorating human rights situation in Zimbabwe was also observed by a UN report that reported the ���fear, frustration and anxiety among many Zimbabweans��� in 2019, as a result of the deteriorating political, economic and social conditions in the country.

Since the November 2017 coup, there have been several calls for a national dialogue involving not just the major political parties but inclusive of various groups in civil society. In September 2019 a National Citizen���s Convention, organized by the Citizen���s Manifesto composed of various civic and faith-based organizations as well as academics and business leaders, called for a new social contract in Zimbabwe. The aim of such a contract would be to build a foundation for social cohesion, national healing and reconciliation and enduring peace in the country.

In a similar vein, a grouping of the major religious denominations in the country, under the auspices of the Zimbabwe Heads of the Christian Denominations (ZHOCD), has called for a Sabbath on elections in the country for seven years.

The proposal sets out that during this period a structure would be set up to: establish an emergency recovery mechanism to address the dire national situation, especially for the most vulnerable groupings; rebuild trust and confidence by healing all the hurts of the past; develop a shared national reform agenda to deepen democracy; establish a shared and inclusive national economic vision. This proposal was complemented by the position of the Platform for Concerned Citizens, which since 2017 has called for the establishment of a National Transitional Authority (NTA).

Among other tasks, such an NTA would facilitate a national dialogue and assist in the establishment of internationally mediated talks between the two major political forces in the country, with a neutral mediator.

In response to the call for national dialogue the two major political parties, Zanu PF and the MDC Alliance, have thus far either rejected the idea or agreed to it under specific terms. In the case of Zanu PF Mnangagwa rejected the church���s call for a temporary stay on elections, on the grounds of its ���subversion��� of the constitution. In addition, Mnangagwa implied that the churches had set out an agenda of action that could be identified with the political agenda of Chamisa���s MDC. Mnangagwa���s position was confirmed by Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga who stated that there would be no need for external mediation in Zimbabwe as the country has the capacity to solve its own problems.

The MDC has similar reservations about the ZHOCD proposal because of its ���significant legal and constitutional implications���. However, the party indicated that it would agree to a national dialogue with an ���independent convenor to map a way forward.��� Central to the strategy of the MDC in pushing such a dialogue has been a combination of denying Mnangagwa political legitimacy, protests, and continued calls for international and regional pressure, through the sanctions narrative.

Thus, at present there is little sign of movement towards a national dialogue. However, there are indications that there are voices in the ruling party that would like to enter broad discussion with Chamisa���s MDC. Zanu PF Youth League political commissar, Godfrey Tsenengamu, is reported to have complained about the ���saboteurs who are proponents and promoters of anarchy, political and economic instability��� in Zanu PF, who are opposed to a dialogue between Mnangagwa and Chamisa. These forces, he claims, are the ���sharks strategically positioned in the party and government who are benefiting from the status quo and who stand to benefit if the situation degenerates.���

The political polarization that characterizes the national context is also apparent at the regional and international levels. The European Union and the U.S. have insisted that the crisis in Zimbabwe is the result not of sanctions but ���years of mismanagement and corruption.��� The Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) has stood in solidarity with the Mnangagwa government and called for the end to sanctions because of their adverse effects on the Zimbabwean economy and the region. For the most part, the hopes for international re-engagement that followed the removal of Mugabe have dissipated.

Yet, despite the bleakness of the political and economic situation, there are small signs of a way beyond the current impasse. A recent statement by the South African Minister of International Relations and Co-operation, Naledi Pandor, showed a clear understanding of the need for a more substantive national dialogue in Zimbabwe. While the Minister reiterated the SADC call for the end of sanctions, she also stated that the economic and political challenges needed to be confronted, simultaneously, through the coming together of political forces in Zimbabwe.

Both major political parties in Zimbabwe face considerable obstacles that could provide them with a major incentive to move towards a national dialogue, with the assistance of key players in SADC. Zanu PF is confronted with major economic challenges on several fronts, to which it has no adequate response, and is in desperate need of outside assistance. The regression in its hopes of international re-engagement combined with continued factionalism in the ruling party is likely to push the latter into an increasing reliance on violence and repression. This response would only raise further questions around the party���s capacity to lead the country forward.

For the MDC and Chamisa the combined strategy of denying legitimacy to the Mnangagwa government, protests, and the idea that the collapse of the economy will lead to the eventual breakdown of the current regime also has its limits.

The state retains the capacity to shut down protests, and the increasing decline of the economy will most likely continue to weaken the capacity of the largely informal workforce for sustained protests. This would push workers further into individual survival strategies. The outcomes of the public sector strikes remain an open question.

Although the actions of public sector workers have without doubt placed major pressure on the state, it will still require broader pressure at national, regional and international levels, to provide a decisive push for a meaningful national dialogue.

This piece was first published in the Zimbabwe Independent. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author.

January 14, 2020

On conspiracy theories

[image error]

Image credit Dee Mula via Twitter.

Once canonized and unassailable, the legacy of Nelson Mandela, South Africa���s most iconic political figure, is now tortured. That post-apartheid South Africa exists in a state of unending political, economic, and social despair has led many to disillusionment with Nelson Mandela and the political settlement that he came to represent.

The current South African political order���in terms of the Constitution, the governance system and economic policy framework���bears the imprint of Mandela���s generation. Mandela���s reputation as a world statesman derived from the so-called success of the transition. But South Africans are divided about their first democratic president. Depending on who you ask, Mandela is either fondly remembered as a hero of liberation, or scornfully derided as a ���sellout.��� And more recently, those unwilling to seat themselves on either side of what feels like an existential divide, have become satisfied with a third option: one where Mandela is neither a god nor fallen angel, but with atheistic incredulity is cast as nothing more than myth���literally.

Last week, South African social media was ablaze with fresh allegations that the real Nelson Mandela died in 1985 at the age of 67 years. This, the conspiracy went, explained why on Mandela���s birthday South Africans are encouraged to perform ���67 minutes��� of charity. But more importantly, that after Mandela supposedly died in 1985, the Apartheid government-installed an imposter by the name of Gibson Makanda to play Mandela. That is the man who negotiated the end of Apartheid and would be the country���s first democratic president. For good measure, some on Twitter, credited the Illuminati, an anti-Semitic conspiracy whereby a supposed small network of individuals run the world, for all this. The implication of all this was that the man leading the ANC���s negotiations with the National Party in the early 1990s was not the radical freedom-fighter, but instead a puppet of his very opposition. Although this conspiracy has circulated for a while without gaining real traction, it made a proper comeback in July last year when an image of a younger Mandela���s face was inputted into the popular FaceApp application. FaceApp ���revealed��� that its version of an aged Mandela looked nothing like the man released to the world from Victor Verster Prison on 11 February, 1990.