Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 194

December 20, 2019

The black son shines

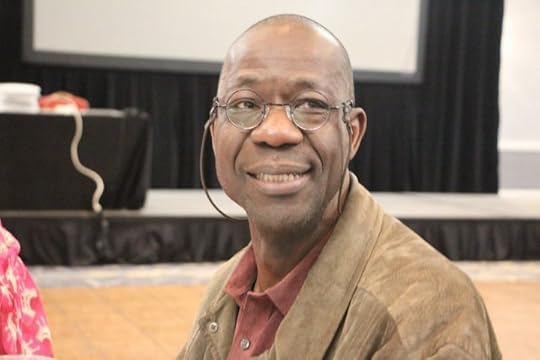

Masauko Chipembere in NY.

Given his tremendous musical output, it is hard to believe the Malawian-American musician Masauko Chipembere just released his first solo album, Masauko. It came out in June 2019. The album is about liberation, love, resilience, activism, giving voice to the powerless, a usable past, and connecting the world of his ancestors, Malawi, with that of his childhood and youth, Los Angeles. But a forthright review wouldn���t do justice to what he has achieved here. To get a full sense of the complex, remarkable world where Masauko���s music comes from, you need to know the man.

This means that you have to start before he was born, with the story of his parents, especially his father, the late Henry Masauko Chipembere, to whom he dedicates the album.

��� from ���Come to Life��� by Masauko.Poor water up this seed come to life

Nurture the growing dream come to life

In 1954, 27-year old Henry Masauko Chipembere graduated from South Africa���s Fort Hare University and returned home to colonial Nyasaland. The territory, now known as Malawi, was landlocked between Mozambique and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). Nyassaland and its people were governed by the British as part of a federation with Southern Rhodesia. The British maintained power via a mix of paternalism, Christian missionaries���who preached obedience to colonialism and liberation in the afterlife���and a local African elite of indirect rulers. While in South Africa, Chipembere had joined the ANC Youth League of Nelson Mandela, which was radicalizing that country���s largest liberation movement. (Even in this, Chipembere stood out: He was one of the first non-South Africans to join the ANC Youth League.) At Fort Hare, his mentor was Z.K. Matthews, a professor and legendary ANC leader. Masauko captures his father���s dilemma:

My father wanted to stay and fight the apartheid he saw growing in South Africa. But Z.K. Matthews told him to go back to Malawi. Matthews felt the federation was simply apartheid heading north. He told my father to take what he was learning in South Africa about protest and struggle and apply it to Nyasaland.

Chipembere was understandably restless when he got home. Soon he immersed himself in the independence struggle for Malawi. Though he quickly developed a reputation as a leader, Chipembere felt himself too inexperienced and too young to be in charge of the independence movement. He and his closest comrade, Kanyama Chiume, were in their early 30s. So, on the advice of Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, they convinced an older Malawian medical doctor, Hastings Kamuzu Banda, to lead the movement, though Banda was living outside of the country. Banda had studied in the United States and Scotland, and had publicly condemned a colonial plan to merely reform British rule in the region. He also had an air of authority which was needed to convince elder Malawians, especially chiefs. ���We needed some grey hair,��� Chipembere later wrote in his biography, Hero of the Nation. For the next few years, Chipembere shuffled between doing the grunt work of revolution and spending time in prison for his politics. By July 6, 1964, Malawi was independent, partly due to Chipembere���s organizing skill. Banda���s party���the Malawi Congress Party (MCP)���won the independence vote outright. In the new government, Chipembere became Minister of Local Government and Education.

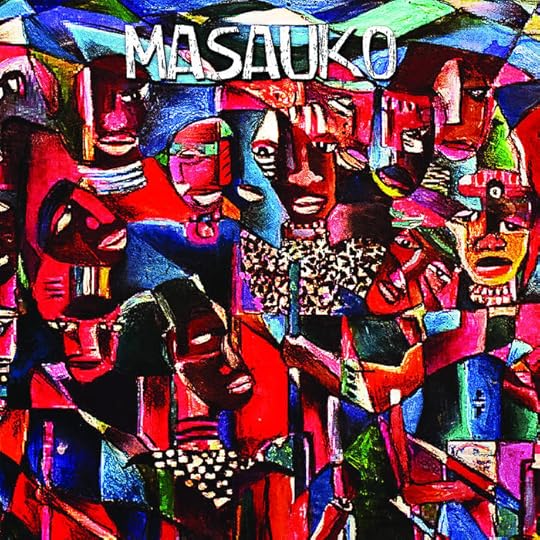

Masauko album cover.

Masauko album cover.The honeymoon did not last long as Chipembere soon clashed with Banda over the latter���s growing authoritarianism, personality cult and rightwing politics. Far from transforming Malawi, Banda supported Portuguese colonialism in Mozambique and Angola, South African apartheid and retained colonial British officers in key positions in Malawi���s military. Banda���s increasingly corrupt regime also failed to implement necessary social and economic programs to alleviate the poverty and degradation wrought on Malawians by colonial racism. In September 1964, Chipembere left government in support of other cabinet members who were removed unfairly by Banda for attempts to question his totalitarian leadership. Chipembere made a classic speech as he left parliament in which he said:

��� history takes long to declare its judgement. The scoundrels of today may be the heroes of tomorrow, the villains of today may be declared saints tomorrow, it may be after their death. So, although today I am condemned, I may be declared a traitor, I know that ultimately, however long it may take, my stand will be justified.

Banda ordered him arrested and he went underground. By the next year, Chipembere was leading an armed rebellion against Banda���s regime. The rebellion failed because Banda was tipped off and had his military and police prepared.

��� from ���Selassie and Chipembere��� by Masauko.Out on the corner of Chipembere and Haile Selassie

Up in Malawi, a part of my destiny was spelled out to me

Through a message from my ancestry

Exile became Chipembere���s only option. After a brief stay in Tanzania where he linked with other liberation movements and leaders, he ended up in Los Angeles, where he was eventually reunited with his wife, Catherine Ajizinga (a political activist in her own right), and their five children, who were smuggled out of Malawi six months after Chipembere fled. In LA, Chipembere became a professor of history at Cal State University-Los Angeles and began his doctoral work at UCLA. But he never lost his sharp political insight. A lecture to students at the University of California-Santa Cruz in 1970 displayed Chipembere���s clarity in tying together critiques of colonialism and third world authoritarianism. Discussing migrant labor in Southern Africa (Banda���s government was acting as a recruitment agency for South African mining companies on terms undermining workers), Chipembere told his audience that, ������ supplying South Africa with cheap labor means perpetuating her economic and therefore military superiority which is used to keep the Africans of South Africa down and poses a threat to the rest of Africa.���

In September 1970, Chipembere and Catherine Ajizinga���s seventh and last child was born (and the only one to be born in the US���their 6th child was born in Tanzania). They named him Masauko Glyn Chipembere, after his dad. Sadly, young Masauko would only spend a short time with his father who passed away from complications related to diabetes on September 24th, 1975. This was just two days before Masauko’s 5th birthday.

In Pasadena, the Chipemberes lived down the street from the famed South African musicians, Caiphus Semenya and Letta Mbulu. Like some of their contemporaries���Hugh Masekela, Abdullah Ibrahim, Sathima Benjamin and Miriam Makeba���the Semenyas had left South Africa in exile in the mid-1960s and settled in Los Angeles. Mbulu had completed five albums by 1977 and with her husband had made a name for herself working with Quincy Jones on the soundtrack music for the TV series Roots.

By serendipity, their son Mosese attended Catherine Chipembere’s 24-hour daycare (a first in Los Angeles to provide 24-hour care). When Letta and Caiphus were on tour, their son stayed at the Chipemberes. Masauko often swam in the pool at the Semenya house, and crucially, took in the musical lessons. There he heard songs like ���Angelina��� (later a cult classic) coming from Caiphus��� studio even before it was released. Caiphus Semenya also bought Masauko his first record player as a child. This is how he got introduced to music, his older brother, Vita, brought home from college: Bob Marley���s Exodus, Steel Pulse���s True Democracy, The Clash���s Sandinista, and UB40���s Signing Off. You can still hear those influences in Masauko���s music, which is a unique mixture of Southern African traditional music with jazz, folk, funk, hip-hop, reggae, and what became known as World Music in the late 1980s.

Whether he planned to or not, in connecting with the Semenyas, Masauko was continuing his father���s regional and pan-African politics, especially linkages between South Africa and Malawi. As Masauko recalls: ���In Steve Biko���s I write what I like, he mentions that he was not inspired by events in the United States as many would have suspected, but by events in places like Malawi in the 1960s.��� For Masauko, this means essentially that pan-Africanist consciousness was circular in nature: ���Matthews inspired my father to go home and fight. Later, Biko was inspired by the successful resistance he had witnessed in Malawi as a youth. I believe one of our huge problems in the region is the failure to see how all of these struggles have always been connected.���

��� ���Africa Calling��� by Masauko, M. Ntaka, L. Klaasen.Africa is calling you

back to the strength in your soul.

If young Masauko was picking up politics from his mother and the Semenyas, he was also being shaped by Los Angeles. The late 1980s and early 1990s was a particularly violent and oppressive period in the city for black people, culminating in the LA Riots of 1992, when the city���s black population orchestrated an uprising against the brutal LAPD after the Rodney King beating. During this time, Masauko also received his musical education in an LA scene that included Ben Harper, Leon Mobley, Primus, Jellyfish, and Freestyle Fellowship, among others. Like most LA artists, Masauko started by playing a mixture of rock, funk, ska, reggae, and hip hop. Bands like the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Fishbone and Jane’s Addiction were the standard; collectively they didn���t sound like anyone else. Especially Fishbone. Masauko had met their keyboardist Chris Dowd at age 14. ���He literally gave me a list of music to go study: Sly Stone, Don Drummond, U-Roy, Funkadelic, The Meters, The Skatalites. He told me straight up that if I wanted to make my mark in music I couldn���t be a copycat. I needed to go to the roots of the music and create my own sound. Best advice ever given to me by an elder musician.���

Masauko Chipembere in NY.

Masauko Chipembere in NY.In the early 90s Masauko���s band Skin brought down the house at the Whiskey A Go-Go, a famed rock venue on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, scouted by record executives. Masauko was rewarded with a record deal by RCA Records through Bruce Flohr, who also signed Dave Matthews at that time. A few songs were recorded but never released because RCA changed presidents and recruited a new batch of artists.

If Masauko���s world was changing fast, so were politics back in Malawi. In 1994, the by now 96-year old Kamuzu Banda had finally stepped down as Malawi���s President after thirty years in power. A mixture of factors���the end of the Cold War, old age, a restive population and regional contagion���had caught up with him. The winds of change were blowing all over Southern Africa. Even South Africa was politically free. Catherine Chipembere announced her return home from exile after 30 years in Los Angeles; to help put an end to the Kamuza era. Leaving behind her seven adult children, she was invited to run for political office upon her return. Her inclusion in the UDF government was a sign to many Malawians that the reforms were irreversible. The Chipembere name brought credibility to the party opposing Banda. She was elected to the country���s Parliament and served as Deputy Minister of Education. None of her children were, however, especially keen about going to visit her in Malawi. Except her youngest, Masauko. In 1996, he traveled to Malawi, ���That���s when Malawi and the whole Chipembere story became real to me, more especially the thought of my mother taking a flight to Malawi to fight someone who was an enemy of pan-Africanism.���

��� from ���Welcome Home��� by Masauko and Mongezi Ntaka.Welcome home

this is our hour

this is our place

this is our time

let���s show some grace

In Malawi, Masauko stayed for a year, getting to know his mother���s world. She was now a Minister, traveling widely in the region and speaking Chichewa, a language he did not speak. His mother blossomed in her return home. It was in the loneliness of living in his mother���s house, away from his life in the US, that he began playing music with local artists and studying traditional Malawian music. He had a grand idea to develop the local music industry and start a band there, but felt he���d be better off decamping to South Africa, following stops in Mozambique and Zimbabwe, hoping to re-connect with the Semenyas, who had returned to South Africa post-apartheid. And this is how he became a pop star in Africa.

In February 1997, at Jahnito���s, a small jazz caf�� in Yeoville, Johannesburg he met songwriter Neo Muyanga, from Soweto, working as a journalist for local station, Radio 702. They started to perform as an acoustic duo called Blk Sonshine. They chose this name for their band as an affirmation and command: ���Black son, shine!���

It made sense that Masauko landed in Johannesburg in the late 90s. It was the region���s most capitalist economy with a deeply embedded music industry. South Africa was also a new country. Black creatives were coming into their own. Spaces were opening up for musicians and artists to try new things. In 1998, Blk Sonshine recorded a self-titled album, which quickly charted. One song, ���Building,��� climbed to number one on the South African jazz charts. The music was what could broadly be described as black folk music. Kwaito, a hybrid of slowed down house music and hip hop dominated in the clubs and on the airwaves, so the album came out of left field. Kwaito was characterized by sparse lyrics and celebration. There was little time for introspection. Blk Sonshine���s music did the opposite. It widened the horizon for what was musically possible in South and Southern Africa. Blk Sonshine took another decade to record a second album, ���Good Life.��� But by then, Chipembere and Muyanga had moved onto other projects. Muyanga began a series of university fellowships, explored South Africa���s musical histories and made an opera. As for Masauko, who by now was married and a father of two young children, he moved to Brooklyn, New York, where he performed locally and internationally as well as being part of a scene that included Talib Kweli and Mos Def. Now and then the duo performed together at major concerts, like they did for Nelson Mandela at his ���46664��� charity concert in 2005, in front of thousands of fans and millions watching on television.

Masauko Chipembere in NY.

Masauko Chipembere in NY.Masauko also played regularly with South African musicians based in the US. One of these was Mongezi Ntaka, the original guitarist for reggae artist Lucky Dube (murdered in 2007) and who currently plays with Vusi Mahlasela, another South African musician. Mongezi is a master of the township jazz guitar style made popular in the west by Ray Phiri (another South African with roots in Malawi) on Paul Simon���s Graceland. Mongezi���s mom is Malawian and his father is South African. Masauko and Mongezi met in the early 2000s:

I saw him play and his vibe reminded me of John Blackie Selowane from Masekela���s band. I told him so. He dug that because Selowane had lived in Malawi when Mongezi was young and was actually a big influence on his playing. We hit it off right away. They are both guitarists who come from township music but can play all Southern African styles.

Like his father, Masauko retained a certain rebelliousness and a desire to travel. After an eight year career as sound engineer at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, countless projects in Malawi with his mother���s organization and his own musical ambassadorship, he and his family took the leap to leave the United States as the Obama-era was coming to an end. With a budding black teenage son and a curious pre-teen daughter, Masauko and his wife read the signs that were telling them that life outside of the US was their best option. With the increasingly depressing atmosphere for black people in the United States (police violence, the election of Donald Trump), Masauko moved his family to Costa Rica. (His wife���s family is from there; Natasha Gordon-Chipembere, who he met in South Africa, is an English professor.) He now lives between Costa Rica, Los Angeles, and New York.

��� from ���Birds will Sing��� by Masauko.One day my bird will sing a song to heal us all.

The song will give us wings

The song won���t let us fall.

Masauko immersed himself in his new surroundings, learning Spanish by playing with local musicians, and eventually forming a band of musicians from all over Latin America, including Roberto Roque from Cuba and Huba Watson, an Afro-Costa Rican rapper. They began building the concept of ���Casa Africa��� which were African-based cultural and musical ���pop-up��� events throughout San Jose, which featured a wide arrange of art from the African Diaspora. Masauko also became the DJ of a jazz radio show called Connections, on 95.5, the national jazz station of Costa Rica. At the same time, he continued to travel internationally, to play music, and eventually, at a concert in Salt Island, Vancouver hosted by the tea company Guyaki, he was approached about recording an album under their new record label Come To Life. In July 2017, he was flown to Malawi with Darryl Chonka, his co-producer and engineer at Guyaki, to meet his Malawian band and rehearse. A week later, the band was flown to Cape Town, South Africa to be recorded. His album ���Masauko��� was made with a stellar cast of young Malawian jazz musicians, including on lead guitarist and background vocals, Ernest Ikwanga; Sam Mkandawire on keyboards (and background vocals); bassist Chambota Chirwa; and drummer Kyle Luciano Phikiso.

It is no surprise that the ensuing years of traveling between the US and Southern Africa profoundly inform Masauko���s music and politics: ���Music is about connection for me. As I have traveled back and forth to Africa over the years, I have found every form of music I learned in the States has some roots in Africa. There is even village music that feels like reggae in Malawi.���

The songs on the album reflect Masauko���s hybrid nature. ���Ilala������on which he shouts out his family name and ancestors���has South American and Southern African sounds mixing. ���Birds will sing��� and ���Building��� reprise two songs off Blk Sonshine���s 1998 album. The guitar-driven ���Watch this woman��� sounds like something Harry Belafonte would have done; in the late 1980s it would have been called World Music. ���Chilembwe,��� is a homage to John Chilembwe, an earlier revolutionary liberation figure in Malawi who had led a bloody, but unsuccessful , insurrection against British rule in the first decade of the 20th century. It has the same reggae inflections of ���Ichi Chakoma��� and ���Selassie and Chipembere.��� The latter songs make explicit the politics of the founder of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and his father. ���Old Shackles��� and ���Come to Life��� have the feel of Soul Brothers��� Mbaqanga. The songs are conscious and the lyrics expansive. From the very beginning of Masauko���s musical journey, he says he understood that songwriting was the medium to give voice to people struggling against inequality and to show solidarity.

Half the songs on the album were written with Mongezi. As a child, he lived in both South Africa and Malawi and brought Masauko tons of knowledge about township jazz, Malawian Kwela, and reggae. He now lives in the Washington DC area. ���Mongezi has really been a teacher to me as a child of exile. He was the one always pushing Lucky Dube to add the Southern African touches to the reggae and stay away from imitating Peter Tosh���s sound which Lucky loved.���

In the end, what drives Masauko is, as he emailed to me in October 2019:

Music has a role to play in shaping consciousness back home. This is conscious music. I’m not with the rappers who say they are not trying to make conscious music. I’m trying to hit folks where Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Fela, Bob Dylan, Hugh Masekela, Chuck D., Nina Simone and Miriam were hitting them. I’m not interested in being the next big pop sensation. I’m interested in liberation. African governments are still controlled by old men from the Banda era. The old men are still clinging to power though they understand few of the issue at play in modern reality.

The black son shines.

Skewing sexuality

A classroom in Ghana. Image credit Ben Gray via Flickr CC.

In May 2011, the then-President of Ghana, John Evans Atta-Mills, declared at the annual convention of the Pentecost Church of Ghana: ���Christ is the president of Ghana,��� and that he owes no one any apologies for the statement which, according to him, is his ���guiding principle as head of state.��� Atta-Mills��� statement at the time collapsed the complex religious composition of Ghana���which includes Islam, traditional African religions, and those who identify as atheists among others���and essentially proposed Christianity as Ghana���s national religion.

Atta-Mills��� utterances underscored the political dominance of Christianity in Ghana since its introduction by Europeans during the slave trade and under colonialism, but also how, as a religion, it has been deployed to define citizenship and deny basic human rights���especially in respect to LGBTQ people. The very beings of LGBTQ in Ghana are decried and derided as ���un-African��� and a western import. At the lead of anti-LGBT groups are a set of organizations that vehemently advocate for the preservation of ���proper��� family values in Ghana.

Front and center is the National Coalition for Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values, a tripartite coalition made up of the Christian council, Catholic secretariat, Catholic Bishops Conference, Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council, the Muslim community and traditional rulers. It was founded in December 2013. These organizations, despite their historical differences, unify in opposition to the rights and freedoms of LGBTQ people.

Founded in December 2013 by Moses Foh-Amoaning, the coalition is fiercely anti-LGBTQ. On its Facebook Page, Foh-Amoaning declares: ���I may lose some friends over this, but homosexuality is a sin.��� He is citing Leviticus 18:22, a Bible passage often quoted by homophobes to support their views that homosexuality is abominable.

What has particularly drawn the ire of the coalition is the decision, in September 2019, by the Ghana Education Service (GES) to introduce a new sexuality education policy. This policy, which is supported by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), incorporates gender, human values, and sexual and reproductive health and rights perspectives into the current curriculum of primary schools on sexuality education. According to the director of the GES, the policy will facilitate ���positive attitudes, open-mindedness, respect for self and others, non-judgmental attitudes, and a sense of responsibility concerning their sexual and reproductive health issues.��� On a sociocultural and political level, sexuality education programs are crucial because they also touch on human rights, gender equality and empowerment, and have been shown to enhance ���young people���s knowledge of gender and social norms.���

A wave of LGBTQ-phobia���mainly under the guise of protecting children and preserving family values and couched in such rhetoric���followed the announcement, with anti-LGBTQ organizations complaining that the policy would ���legitimize LGBT identification.)��� Organizations like the aforementioned National Coalition for Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values, the Christian Council of Ghana (CCG), and the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council (GPCC) interpreted the content of the policy as “legitimizing LGBT identification.” The President of the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council (GPCC), Paul Yaw Frimpong-Manso, referred to the policy as ���Comprehensive Satanic Engagement.���

No surprise that evangelicals and conservatives outside Ghana, especially from the US, chimed in. Last month, the African Family and Sustainable Development Summit, a two-day conference supported by the US-led network called The World Congress of Families (WCF), was held in Accra. The WCF has connections to white supremacist, anti-LGBTQ, and Islamophobic organizations.

To make sense of the current anxieties around rights-based sexuality education in Ghana, however, it is important to situate them in a history that produced the current discourses and attitudes on what constitutes family values. In 1961, the Christian Council of Ghana (CCG) established the Committee on Christian Marriage and Family Life (CCMFL) ���to promote positive Christian teaching on sex, marriage and family life.��� Some of the projects pursued by the CCFML included youth outreach programs that introduced Ghanaian youth to ���proper sexual behaviors.��� The projects, funded mostly by the Christian Aid, an organization based in Britain, pursued the Christian marriage and family life projects in some parts of Ghana. Their execution not only transplanted Euro-American ideas of ���proper��� family values onto indigenous ideas of gender, sexuality and desire, but also radically redefined them. Letters exchanged between the Christian Council of Ghana and the Christian Aid between 1965-1975 expose how some politicians and clergy relied on funding from Britain and other European nations to circulate western notions of the heterosexual family and monogamy.

Evangelical groups like the WCF, based in the US���a country with a violent history of racism���repeats these dangerous liaisons by supporting organizations like the National Coalition for the Preservation of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Family Values. The WCF���s recent conference in Accra exemplifies its links to the coalition, provoking what the Zambian theologian Kapya Kaoma calls ���the global cultural wars.��� In the midst of these cultural wars, some Ghanaians make the questionable claim that heterosexuality is authentically African while supporters of LGBTQ visibility view homophobia as a phenomenon imported to Africa from the west.

If the history of the relationship between Christian Aid and CCG has taught us anything, it is how the meanings of gender, sexuality, and marriage shift over time. It is critical, then, that we situate these conversations in the contexts of complex histories. Such a pursuit prompts us to ask how feminist and LGBTQ movements in Ghana can become the vehicle for envisioning a future in which ���preserving proper family��� values does not become an alibi for the rape and violent abuse of girls, as the veteran Ghanaian journalist Elizabeth Ohene���s recent expose�� demonstrated? How can such collaborations dismantle the virulent male supremacy that allows gender-based abuse to continue? In a country where Christianity has become the reason for indefensible actions like scapegoating members of the LGBTQ community, duping the poor, infirming the sick, and targeting ethnic and non-Christian minorities and the country���s most vulnerable people, it is clear that our communities and broader society needs fundamental moral, spiritual and political restructuring.

December 19, 2019

I only have eyes for Bobi Wine

Bobi Wine. Screenshot from SABC News.

Ever since Bobi Wine, Uganda���s biggest pop star, won his seat in parliament in a contested 2017 race, western journalists have flocked to the country���s capital, Kampala, to conduct interviews with and profile him. The interest is certainly justified: in a short time, Wine, real name Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, has turned a decade-long career in music, often addressing the problems faced by Uganda���s poor, into a political movement of which he is, undoubtedly, at the center (and what that has the Ugandan state nervous). He has announced he will challenge President Yoweri Museveni for the presidency in 2021. Far from replicating the conventional trappings for which western journalists are often criticized with regards to reporting on Africa and its politics, reporting on Wine has presented a rather distinct challenge, one that reinforces a formidable challenge in Uganda political history.

In June, at a cafe in Kololo, Kampala, I spoke with Moses Khisa, Assistant Professor of political science at North Carolina State University and a regular contributor to Uganda���s opposition newspaper, the Daily Monitor:

I���ve been fascinated ��� by the overwhelming interest, and perhaps even obsession if I may put it that way, with Bobi Wine. So, I keep asking myself ���Why? What is it that you see that I, as a Ugandan, haven���t quite figured out?��� Okay, so I know that this guy is a celebrity, he appeals to young people, he���s a new kid on the block ��� But I have never in my lifetime seen such enormous western media interest in an African politician, let alone a Ugandan politician ��� Almost every media house that matters has been reporting on Bobi Wine.

Though my own reasons for focusing on Wine have certainly changed, for many western journalists (especially those who spend very little time visiting, let alone living in, the countries they report about), Bobi Wine represents the latest shiny new object through which to grow by-lines. The nexus of music, politics and Africa where Wine resides, makes for a rather sexy subject matter that can grab a readership interested in any of those areas. It certainly doesn���t hurt that Wine is quite handsome, has an incredible voice, catchy songs, an absurdly cool joie de vivre that gets pronounced by his slight, purposeful limp, and a political lexicon as aesthetically radical as the red berets worn by his movement, People Power. But for Khisa, as for many Ugandans, including People Power supporters and Wine himself, the singer-turned-politician represents little that could be considered new for the national political landscape.

These parachute journalists also make elementary mistakes. For example, journalist Philip Pilling, in an article based on his interview with Wine in Kamwokya and published in The Financial Times in July, not only confused the ingredients of his own lunch, but also one of Wine���s associates. However, the bigger problem with the FT coverage, and many of the outlets that have reported on Wine, is that they fail to deliver anything of substance or context regarding the nuances of Uganda politics and the challenges facing Wine and People Power. With few exceptions (one being Helen Epstein���s reporting in The New York Review of Books), the only context usually included in interviews with and short profiles on Wine are the one or two lines devoted to Museveni and his 33 years in power, often written in the same brain-numbingly similar formula.

While it could be convincingly argued that the mountain of media attention heaped on Wine has benefited both himself and his movement by assuring his continued safety, his rise and People���s Power���s significance within Uganda���s post-colonial history is vastly more complex than western journalism represents. In focusing strictly on Uganda���s ���Ghetto President��� (as Wine likes to be known) and merely mentioning his autocratic rival, Museveni, readers are led to construct a simple, bipolar model of young vs. old, good vs evil���a pitched political battle between two equal and opposite forces. This could not be further from the case. Most significantly, and as someone who has spent considerably more than a few days in Uganda researching the Ugandan political landscape, there are other political actors to consider. Take Dr. Kizza Besigye and his Forum for Democratic Change, which prior to the emergence of Bobi Wine and People Power, were the primary force of Uganda���s opposition.

Besigye, a former army officer, medical doctor and one-time confidante of Museveni, has until recently been the most prominent opposition leader. For his troubles, he has faced multiple arrests, is likely under constant surveillance, and he and his supporters have been subjected to violent attacks by the police. Besigye has been, and remains, a critical figure on the Ugandan political landscape. So much so, that many believe Wine���s success in defeating Museveni depends on Besigye���s cooperation in forming a coalition that could front a single candidate.

When I spoke with Nabilah Ssempala, the MP for the Kampala Women Parliamentary Constituency and so-called ���rogue member��� of Besigye���s Forum for Democratic Change, she illuminated further the nature of Besigye���s relationship to People Power.

It’s existed since independence, people power; but with different generations it has dawned different clothing. But it’s generally the hope of Ugandans for a better government, for better policies and for fundamental change. Even President Museveni in the bush days, he dawned the people power ��� [Nasser] Sebaggala, who was a very popular mayor [of Kampala] ��� he got that baton for some time, which he handed over to Besigye.

In other words, and as I heard it many times, Besigye was People Power before People Power was People Power. Besigye has, in fact, consistently been the runner-up in all four presidential elections since multi-party dispensation was restored in 2005, receiving a high of 37% of the vote in 2006. It is true that we can never know the real vote counts of elections in Uganda where every public institution���from the Electoral Commission, to the police and military, to the Supreme Court���rests firmly in the grip of Museveni���s tentacular authority. Besigye���s electoral performance, in spite of this corruption, is all the more impressive.

Plenty of others, including Besigye himself, have so little faith in the democratic process ���being of the belief that President Museveni, through various institutions, has rigged some or all of the presidential and parliamentary elections���that the notion of a coalition as a solution to the problem is laughable. Still more, like Ssempala, believe Besigye has developed the same narcissistic tendencies inherent to the despot he has for so long tried to unseat, and that his own desire for power will prevent him from forming any coalition or falling in behind Wine���s People Power front. This is, perhaps, one of the reasons undergirding the emergence of the latest political force in Uganda, a breakaway from the FDC: the Alliance for National Transformation led by General Mugisha Muntu.

These details, critical as they are to understanding Bobi Wine���s chances going forward, are not what you would read in the Financial Times, let alone the Los Angeles Times, The Guardian or any other mainstream publication. There is also little or no mention of others who have more recently aided in the opposition to Museveni���s regime. For example, Francis Zaake, the MP who was arrested and tortured on the same day as Wine; or Ziggy Wine, the People Power musician who was abducted and then died shortly after his body was dumped at Mulago Hospital; or the nearly thirty opposition politicians and supporters (including the MP���s Kassiano Wadri, Gerald Karuhanga or Paul Mwiru) who were arrested in Arua in August of 2018 and continue to face trumped-up treason charges.

Nor do mainstream publications broaden the discussion of Wine���s political movement, and therefore, readers are precluded from understanding what People Power is���and what it is not. Some attention has been given to Wine���s views on homosexuality, which���from what I have seen and heard���seems to have undergone a shift. Though People Power lacks an overt policy recognizing LGBT rights, it is far from participating in the violent anti-homosexual rhetoric that is pervasive in Uganda���s Parliament. Reporting on policy positions beyond this, which has always been more focused on Wine���s personal sentiments than on his movement, are virtually nonexistent. Admittedly, People Power as a political organization (Wine and his affiliates would object to this label) suffers from an extreme lack of policy.

Apart from rhetoric regarding corruption, unemployment, and the need to build stronger, independent institutions, People Power offers little in terms of a substantive or divergent agenda. This does not, however, necessarily make them an outlier among Uganda���s political parties. If one cannot envision wielding power, knowing what to do with it becomes a rather difficult hurdle. Hence, People Power���s primary message of uniting across identity groups���a closing of the fist as it were���to coalesce around the collective aim of unseating Museveni.

People Power���s mission is what its name implies, a realization of the supreme agency of the masses. But what happens after? If the pressure that accompanies journalistic attention could force Wine to reconsider his views on homosexuality, could not this same attention provoke deeper considerations of policy on the part of his movement? Perhaps such policies���whatever they may be���that might strike at the heart of Uganda���s perpetual strongman problem?

For mainstream publications and the drop-in journalists who write for them, Bobi Wine is the sole star of the show. For whatever number of obscure reasons���naivet��, a lack of resources, or just plain journalistic vanity���painting a more nuanced portrait of Uganda politics remains outside the interests of mainstream western publications. In this way, mainstream publications reinforce the condition from which Ugandan politics has suffered since independence. While there is certainly much that can be said���too much to say here���regarding the colonial origins of strong man politics, it is worth questioning the ways in which contemporary journalism is complicit in its continuation. If journalists are to be truly dedicated to the practice of speaking truth to power���whether that journalist be western or that power be African or not���is it not worthwhile to get to know the subtleties and complexities of that power?

Time travelin’

Chimurenga: Pan African Space Station at the Vera List Center Forum 2019, Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, The New School, October 23-25, 2019. Image credit Jordan Rathkopf, courtesy Vera List Center for Art and Politics.

In January 1977, Nigeria���s government hosted 17,000 artists from Africa and its diaspora for 29 days at the 2nd World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC) in the country���s commercial capital, Lagos. (The first such festival was held in Dakar, Senegal in 1966). FESTAC remains the largest gathering in one place of black and African artists as well as intellectuals from the continent and in the diaspora. One group that stood out by their presence was the African-American delegation. This contingent included Sun Ra, singer-songwriter Stevie Wonder, the feminist academic Audre Lorde, and writer Alice Walker, among many others.

Fast forward to October 2018, when the Vera List Center for Arts and Politics (VLC) at The New School awarded its prestigious Jane Lombard Art Prize to Chimurenga���the Cape Town, South Africa-based pan-African artist collective. The finalists for the prize included Vietnamese-American artist Tiffany Chung, Russian-Ghanaian photographer Liz Johnson Artur and the artist-run, Bethlehem-based initiative Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir.

At the beginning of October 2019, three Chimurenga staffers���Ntone Edjabe, Dudu Lamola, and Graeme Arendse���were to travel to New York City to accept the prize. Chimurenga is widely known for its publications, most notably the Chronic, but it also runs a music project, the Pan-African Space Station (PASS). The latter consists of concerts, an archive, and a pop-up radio event, which Chimurenga has hosted in a number of cities including Cairo, Harare, Helsinki, London, and previously in New York. As part of the festivities for the prize-giving, Chimurenga wanted PASS to recreate the experience of FESTAC.

Upon Ntone, Lamola, and Arendse’s in New York, the white-cube gallery of the Aronson Galleries at The New School���the venue for PASS���transformed almost overnight. Before a wall covered in a soft but serious red���Chimurenga red���was a plush sofa set adorned with kitenge print fabric. Pastel colored, retro armchairs huddled around coffee tables throughout the rest of the room. A black and white photomural of young, African-American artists in a conference hall in Lagos covered the adjacent wall. This image was captured by Calvin Reid, a photographer who had been a part of the US delegation at FESTAC. Once the setup was complete, the room felt like a personal library, but one owned by an erudite person with a taste for making guests feel at home.

Chimurenga: Pan African Space Station at the Vera List Center Forum 2019, Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, The New School, October 23-25, 2019. Image credit Jordan Rathkopf, courtesy Vera List Center for Art and Politics.

Chimurenga: Pan African Space Station at the Vera List Center Forum 2019, Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, The New School, October 23-25, 2019. Image credit Jordan Rathkopf, courtesy Vera List Center for Art and Politics.As the first day of the broadcast got closer, I tried to articulate for friends and on the VLC���s social media platforms what was meant by a ���Pan-African Space Station.��� It���s a literal space station? Well, it���s at the New School gallery. Oh, so it���s an exhibition. No, there won���t be anything hanging on the walls. It���s more like a radio show. So, they���ll be recording there and we can listen in? Yes, but the point is to have guests present. Huh? Yes, think of it as a radio show hosted before a studio audience. I exhaled. That sounded close. But I knew it wasn���t quite right. This implied a separation between audience and speakers, between backstage and frontstage. But the layout spoke to something else entirely.

PASS would begin with a reflection on afrofuturist bandleader Sun Ra Arkestra���s performances at FESTAC. Jazz musicians Craig Harris and Ahmed Abdulla, who traveled to Lagos as then members of the Arkestra, would join Edjabe, photo documentarian Calvin Reid, and jazz educator Richard Harper for this conversation. On day two, the poet Harmony Holiday would host black, female artists who had attended FESTAC. Among her guests were official FESTAC photographer Marilyn Nance, sculptor Valerie Maynard, and novelist Louise Merriweather. Day three would explore the visual memory of FESTAC through the archives of photographers who had documented the event, including Nance and Reid.

PASS would culminate in a rare performance led by Craig Harris, who had written a jazz suite commemorating the spirit of FESTAC soon after his return from Lagos. Harris had only performed the suite once before, in 1982.

The day finally arrived, and it felt like a homecoming. FESTAC alumni greeted one another with such emotion; some had not met since Lagos more than 40 years ago. Students, academics, artists and others slowly streamed in, walking around the room with keen interest but keeping a respectful distance. The alumni excitedly pointed out their younger selves on the photomural, a photograph by Calvin Reid, and in the massive book of FESTAC archives that Chimurenga launched at PASS.

Craig Harris, FESTAC ’77 at the Vera List Center Forum 2019, Tishman Auditorium, The New School, October 25, 2019. Image credit Jordan Rathkopf, courtesy Vera List Center for Art and Politics.

Craig Harris, FESTAC ’77 at the Vera List Center Forum 2019, Tishman Auditorium, The New School, October 25, 2019. Image credit Jordan Rathkopf, courtesy Vera List Center for Art and Politics.As the room filled up, FESTAC participants settled in on the couches up front. An ���On Air��� light flickered on. The room fell into a hush. The alumni recalled stories of their time in Lagos like it was yesterday. As they talked, recorded sounds floated in the background���radio interviews from the FESTAC venue, performances by various groups that had been in attendance. I can only liken it to time travel. When the lights came back on for a brief break, I had forgotten where I was.

As Tadiwa Madenga, a PhD candidate of African and African American Studies put it, ���when an older person looks you in the eye and says: ���This was the best event in my life,��� it is different from hearing it in a podcast.��� This was part of Chimurenga���s intention and design, to construct a space that allowed time for these questions to form and to inform conversations between FESTAC participants and audience members gathered to hear them speak. As I replaced thermoses full of hot coffee, I overheard a few of those questions. Did you meet Kenyan artists while you were at FESTAC? How did the event influence you personally? And your artistic practice?

All of a sudden, there was so much to talk about. These stories from this largely forgotten event gave us a shared history in the recent past. For me, it felt personal. Coming to the US from Ethiopia as an undergraduate, I had felt a strong kinship but was sometimes at a loss among the various communities of black people from the US and from around the world. We were of Africa but recent histories had diverged our paths. What was our common language?

I would later learn that, during their studies in the US, front-runners of the Ethiopian Student Movement had fought and organized alongside black Americans in the Civil Rights Movement. That Claude McKay, a literary giant of the Harlem Renaissance, had written Amiable with Big Teeth about the African-American campaign to support Ethiopia at the onset of the fascist Italian invasion in 1935.

Rediscovering this shared legacy gave me a stake in the conversation, and much more. But, learning about FESTAC was entirely different. The very scale of this gathering in Lagos was epic.

Craig Harris, FESTAC ’77 at the Vera List Center Forum 2019, Tishman Auditorium, The New School, October 25, 2019. Image credit Jordan Rathkopf, courtesy Vera List Center for Art and Politics.

Craig Harris, FESTAC ’77 at the Vera List Center Forum 2019, Tishman Auditorium, The New School, October 25, 2019. Image credit Jordan Rathkopf, courtesy Vera List Center for Art and Politics.Neither was FESTAC simply a celebration of black culture. The festival became a lobbying ground against apartheid South Africa and the still-colonized Rhodesia. On a larger scale, the organizing committees became embassies of new imagined black states, ���Black Britain,��� ���Black America,��� ���Black South Africa������alongside recently independent African states. This facilitated a direct line of communication among black peoples that was not mediated by the official state apparatuses that invariably oppressed the people they claimed to represent.

During her conversation with the female alumni, Holiday read a reflection about the communities of black female artists that had emerged from FESTAC. Among many questions, she asked, ���can a festival turn into eternal solidarity?��� ���Can we defeat our common enemies ��� [and] ��� capitalism���s ability to turn all creative output into a commodity?���

These questions highlight how relevant FESTAC remains to global discourses about blackness and diaspora, community and resistance. While we no longer have the same colonial apparatus to battle on the continent, these questions still remain. What does global black solidarity mean in this day and age? How do we institutionalize solidarity towards a concerted outcome? The possibilities are endless.

In the meantime, it was enough that the event just happened. ���I was so moved to be in that space and to be transported to this time and place [that] I had imagined largely by myself,��� said Kleaver Cruz, a writer in the audience who is independently researching FESTAC for a forthcoming book������imagine��� being the key word here. For curator Koyo Kouoh, the Jane Lombard Prize jury chair, Chimurenga ���boldly and unapologetically reclaim[s] the African imaginary.���

Craig Harris���s concert brought PASS���s three-day journey full circle. A spirit of generosity and communion permeated the concert, as undoubtedly it had done at FESTAC. By the end, there was a murmur floating around from conversation to conversation. It sounded like, ���imagine what FESTAC might look like in 2020 ���”

December 18, 2019

On meeting Pastor Evan

Pastor Evan. Image credit This Flag Citizens Movement.

April 19, 2016���It���s night-time in a small, fluorescent-lit church office. A man sits alone, anxious and ashamed. He cannot provide for his family. His rent is due and so are his children���s school fees. He has a knack for fixing things, but not this. Not when his country���s economy has collapsed. Not when its President���in power for thirty-six years���rules with an iron fist. In the man���s office hangs a flag. He reaches for it as he considers the promise that a nation���s flag represents. He drapes the flag around him, picks up his phone, and begins recording. Hunched in front of the camera, hands toying with the ends of the flag, words pour out of him with passion and urgency. He ends his lament on a call to action:

���This is the time that a change must happen. Quit standing on the sidelines!”

Posting the video to social media would be preposterous, he knows. People in his country have been beaten, imprisoned, and disappeared on the mere suspicion of dissent. But a few hours later, he does it anyway. He uploads the video to Facebook and tags it: #ThisFlag. By morning, his four-minute video has gone viral and soon virtually everyone with a cellphone in his country, as well as many thousands who have fled the country, will see it. This hitherto unknown man is now a marked man.

#ThisFlag

What Evan Mawarire cannot foresee when he posts his video is that thousands of Zimbabweans will be emboldened to join him in speaking out, many for the first time, on the injustices, corruption, and decades-long collapse into poverty of their once prosperous nation. Within weeks, #ThisFlag will give rise to the largest social media movement his country has ever witnessed, and Evan will be called ���the flag guy,��� heralded far and wide as the spark for Zimbabwe���s Arab Spring. In a clever act of subversion, inspired by his act of wearing it, Zimbabweans from all walks of life begin displaying their nation���s flag.

Initially, the government appears clueless about the reach and power of social media with the government Minister of Higher Education dismissing #ThisFlag as a ���pastor���s fart in the corridors of power.��� At one point and farcically, the government attempts to ban the flag, but within weeks they realize its power. Evan starts receiving threats that range from anonymous phone calls to blatant physical assaults, which include being accosted by the government Minister of Information. Undeterred, he continues posting his videos���one a day for the month of May, and more in June which he now narrates both in English and Shona thereby expanding his audience and reach. At the start of July, Evan narrowly escapes an abduction attempt. He moves to a safe house. Then he takes his social media activism one step further.

Evan calls for peaceful protests in the form of a series of national stay-aways. Under President Robert Mugabe, any form of public protest is banned. And yet, on July 6th, 2016 Evan���s call for the first stay-away is, to everyone���s surprise, heeded by the entire nation as people stay at home. The nation comes to a standstill and the ruling Zanu-PF Party will almost certainly resort to its usual, brutal playbook. Under Mugabe, opposition leaders and activists are routinely imprisoned, beaten, and disappeared���and all for doing far less than bringing a whole nation to a halt. Preparing for the worst, Evan records a video to be released should he be arrested or abducted.

The day after the national shut down, I land in Zimbabwe for a family visit. The US has issued travel warnings and there is talk of riots; but on our drive from the airport to the northern suburbs of Harare, things appear calm. Visibly, not much has changed since my last visit three years earlier, other than further deterioration of the roads. But there is something new���all the roadside vendors are selling Zimbabwe���s national flag. The flag is now on cars, in shop windows, around people���s shoulders���it���s everywhere. Even more striking is what I hear. Everyone, from relatives to friends and even strangers, seem animated with mention of ���the flag guy.��� It���s the first time in my twenty-four years of visiting Zimbabwe that I���ve heard Zimbabweans speak so openly, almost fearlessly, in support of someone critical of Mugabe and his Zanu-PF government. What���s more, I learn that the flag guy is a pastor.

Over the years, I had been following the rise of Pentecostal preacher-prophets and their mega churches in countries where I once lived: Nigeria and Kenya as well as Zimbabwe. I���d seen how these preachers enjoyed extravagant lifestyles funded by the tithes and donations of their congregants while many of these same congregants struggled to make ends meet. In Zimbabwe, millions were surviving on food aid. These same preachers often courted the favour of repressive leaders in power, blessing them, and welcoming them into their churches. I had grown disillusioned with such leaders who, to my eyes, were not setting a Christ-like example of humility and service to others. So, to hear of a Pentecostal pastor of a small congregation, who was not only brave enough to speak truth to power, but to speak on behalf of ordinary citizens, was both inspiring and exciting.

The Junior President

When Evan was born, in 1977, Zimbabwe was still Rhodesia and under white, apartheid-style, minority rule. At that time, the black majority lived either in dense, segregated city townships or in the rural areas labeled maruzevha (native reserves). Evan���s family lived first in the rural areas and then later moved to Glen Norah, one of the older black townships on the margins of the capital. As the first-born of six children, Evan was expected to set a good example for his younger siblings and especially so once admitted to Prince Edward School.

I have visited this boys school on a number occasions���my husband was one of the first black students admitted after Independence in 1980. Until then, Prince Edward was a whites-only school steeped in the nation���s colonial history from its royal name and famous Jubilee Field to its school motto: Tot Facienda Parum Factum (So Much to Do; So Little Done) attributed to the imperialist Cecil Rhodes, who named the country after himself. This hundred-year-old school continues to be known for its academic excellence and sporting prowess with its own astronomy observatory, vast acres of lawns, sports fields, and state-of-the-art science labs.

When Evan started at Prince Edward in the early 1990s, this was an exciting time for him and for the country. Zimbabwe was doing well and seemed to be bucking the trend of other African countries. Its President, Robert Mugabe, was lauded at home and abroad as a model for Africa. Yet under the surface all was not well. Unbeknownst to many, a genocide had been committed in Matabeleland in the 1980s under Mugabe���s orders, and the news of this was kept suppressed. Meanwhile, at school, Evan was not faring as well as expected. He performed poorly on his Form Three exams, and his father decided to withdraw him. The fees were high and the family couldn���t afford to keep a child, who wasn���t doing well, in an expensive school. To Evan���s consternation, he was sent to a Salvation Army mission school under the supervision of a strict disciplinarian uncle.

Charles Clack Secondary School in Magunje could not be more different than Prince Edward. It was located in the rural areas and designed for black Africans pre-independence. It had no running water, no electricity, and only pit latrines for toilets. Cattle routinely wandered the school grounds. But at Charles Clack, Evan studied hard and did well. He became a school prefect and discovered an interest in civics. He joined the inter-schools��� competitions for Zimbabwe���s Junior Parliament and through this countrywide competition he would ultimately be selected, from students all across the country, as Zimbabwe���s Junior President.

A flag seller at a sports event. Harare, July 2016. Image credit James M. Manyika

A flag seller at a sports event. Harare, July 2016. Image credit James M. ManyikaThe first arrests

July 12, 2016���Evan has been in hiding for several days when his wife sends urgent word that the police are looking for him. On advice from the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights (ZLHR) he turns himself in and reports to a police station. Accompanied by a ZLHR lawyer, he is questioned for hours. Then his home is searched. No incriminating evidence is found. Regardless, he���s detained and charged for ���inciting public violence and disturbing the peace.��� He is thrown into Baghdad���a crowded holding cell in Harare���s Central Police station, where two dozen men sit huddled on the concrete floor. It���s wintertime. Evan has never been to prison before. The only spot available is next to the open toilet. His blanket, the last remaining one, is stained with fresh feces. Hours later, in the middle of night when other prisoners have fallen asleep, two men quietly remove Evan from Baghdad.

He is handcuffed and marched to a basement cell. Here he is ordered to remove his shoes and sit on the floor. The interrogators play good cop/bad cop. He is asked repeatedly for whom he is working and who funds his media activism. They don���t believe him when he says he���s acting alone. It���s freezing, and Evan soon loses sensation in his bottom and feet. The interrogators ask: What will you do if we send someone to rape your wife while we hold you in jail? How will you feel if we release you to bury your children? When they dump him back in Baghdad, they warn him to watch out for vamwe vacho vanoda varume (the men that like men).

July 13, 2016���It���s morning and Evan has been awake all night, shivering. He is transported to Rotten Row Magistrates Court. A crowd of several thousand has gathered. Inside, Evan is shuttled between one filthy holding cell and another. Finally, when night falls, he is led into the courtroom which has been opened to hear his special case. His face lights up when he sees his wife. She doesn���t look harmed. She isn���t under arrest. His lawyer is asked to stand, and alongside him are nearly one hundred more lawyers who have shown up in support. But then comes the pronouncement that his charge has been escalated. He is now being charged with attempting to subvert a constitutionally elected government. He looks visibly shaken. This new charge, akin to treason, carries a twenty-year prison sentence.

Then Evan hears the crowds outside singing���freedom songs and church songs! Like the Biblical battle of Jericho, the metaphorical walls collapse. His lawyers successfully argue that the switch to this second charge is unconstitutional and Evan is released. Now he���s outside with a moment of freedom, fresh air, and the noise of the crowd. Then the whisper, from one of the guards, that he will be immediately rearrested. To save him from rearrest, he���s told to go out through the crowds. The crowds in their excitement nearly crush him. They also act temporarily as a shield, but his lawyers know this is not enough. Another safe house, a quick disguise, and a fast journey south through a quiet border town into Botswana, and Evan is in exile.

Days after Evan escapes, President Robert Mugabe himself rebukes Evan on national television, questioning whether ���he���s a true man of God���. Days later, on July 23rd, the government-sponsored newspaper, The Herald, carries the headline: Mawarire Is No Saint. The article claims that Evan made up his story of financial woes and that he was in fact ���sponsored by Western governments to distabilise (sic) the country.���

When news arrives that Evan is safely out of the country, many Zimbabweans feel relief, but soon there are grumblings. What good is their Savior outside? And now that the State had lost its prey, officials are undeterred in their efforts to discredit Evan. Fueled by clever disinformation, people���s disappointment grows. Evan is called a ���sellout��� and after the years of war, the pastor knows well what happens to a sell-out. Meanwhile, President Mugabe continues to ridicule him in public. It is clear that Evan is not welcome back in the country.

Evan spends the next six months out of Zimbabwe, first in South Africa and then in the United States, during which he finds the support to get his family out of the country too. Abroad, his wife gives birth to their third child. Evan is safe, his family is safe, but he is dislocated. He has no job in this place of safety, no friends, no community. He had acted on impulse, impulse born of desperation, and his voice had been the voice of the people, but now he feels rudderless. After discussion with a few close friends, and his lawyers, he decides to return. He knows it���s dangerous for him to return to Zimbabwe but he also doesn���t want to abandon the cause. He makes plans to return telling only a few people the date of his arrival.

February 1, 2017���Evan is met by the authorities as soon as his plane lands. Five men march him away, interrogate him, then turn him over to the police. He is arrested and sent to remand prison. That night, Evan is thrown into a truck and told that he���s going to Chikurubi. He���s the only prisoner in the truck. His leg irons began to clatter as his legs shake. The mere mention of Chikurubi (like Robben Island, Rikers, or San Quentin), is enough to instill terror. Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison is known for housing the most hardened of criminals, and for its prison violence, overcrowding, and disease. It is here, in the years before Independence, where the white Rhodesian government used to throw the leaders of the struggle. Evan asks his guard if this is the end. He���s imagining being dumped in a ditch or worse. They arrive at Chikurubi���high concrete walls, razor wire, security lights, and armed guards everywhere.

Inside, Evan is given a bucket to hold all the possessions he���s allowed to take���his Bible, some underwear, and a striped prison-issue sweater made by the prison guards��� wives. He���s placed in the D Wing. D is reserved for the most serious offenders���from murderers to rapists���those serving eight years to life. Now comes his crash course on life in a maximum-security prison���a beating from a prison guard and some unexpected kindness from fellow inmates.

For the next few months, Evan will be in and out of prison in a continuing cycle of arrests, imprisonment, and release on stringent bail conditions that include the surrender of his passport as well as the title deeds to his parents��� house. This pattern persists until November. Then, the unimaginable happens.

November 14, 2017��� Major General Sibusiso Moyo appears in full military fatigues on Zimbabwe���s national TV. He announces that the armed forces have stepped in to ���pacify a degenerating social and economic situation in the country.��� It is not ���a military take-over��� or a coup, he insists, even as troops appear on the streets of Harare. The troops block government buildings and occupy the State House. Within days, Robert Mugabe is forced to step down. And with him goes his wife���his one-time secretary and hugely unpopular would-be successor, mocked as the ���The First Shopper��� and ���Gucci Grace.���

Two weeks later, Evan���s case is finally brought to trial and he is acquitted of all charges. He becomes a free man as Robert Mugabe is deposed. The country goes wild with jubilation at Mugabe���s removal���people crying, ululating, dancing, horn-blaring in the streets. Pastor Evan is amongst them. He���s ecstatic���laughing and crying, as people pose with him to take selfies with their flags. Flags are everywhere���on cars and buildings and wrapped around people like superhero capes. Mugabe is out and his former Vice President-turned rival, Emmerson Mnangagwa (nicknamed ���The Crocodile��� for his suspected role in the Gukurahundi genocidal killings) is made interim President. Mnangagwa (also known as ���ED���) proclaims a ���New Zimbabwe��� wearing a scarf in Zimbabwe���s flag colours. The fact that Evan was the first to wear the flag as scarf appears forgotten. The scarf is now called the ���ED Scarf.���

Abroad

It���s early evening in the summer of 2018 and Evan is wearing jeans and a Stanford university sweatshirt. I notice the Zimbabwean flag tied around the straps of his backpack which he puts down as he arrives. My husband, who had met Evan two years earlier after Evan had escaped to the United States, has invited him to our home in San Francisco for dinner. Two others join us, both Zimbabweans���one is a cousin visiting from out of town and the second, an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley.

When Evan sees me, his greeting is warm and effusive: ���Hello ma���am, how are you? It���s a pleasure to meet you,��� he says, smiling broadly as he turns to greet the others. As I watch the ease with which he interacts with the younger student, it���s easy to see what made him a popular, humorous youth pastor. ���Wow!��� he exclaims enthusiastically when hearing what each of us is doing, even though we are more interested in hearing about him and the situation in Zimbabwe.

We are meeting in the run up to Zimbabwe���s first election following Mugabe���s��removal from power, and Evan is running for political office. He is running as an independent for a seat in Harare���s city council, which is where he feels he can make the most difference to improve people���s daily lives. He had been campaigning up until a few weeks prior. But then, as he explains, being offered the prestigious Draper Hills Summer Fellowship at Stanford University was an opportunity he couldn���t turn down, as it enabled him to see his family in America whom he hadn���t seen in a year and half. Meanwhile, he remains in close touch with Zimbabwe via phone and social media, and his excitement for the promised hope of this election is palpable.

A few days later, with the election results now in, we meet up with Evan again and this time his mood is subdued. He says his disappointment is not about his own electoral loss, but about the lives of the peaceful protestors and bystanders shot dead on the streets of Harare in the wake of the election. The election has been won by Mnangagwa, the interim President who replaced Mugabe. Mnangagwa is from Mugabe���s Zanu-PF party, not the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). For years, Mugabe had brutally repressed the MDC. He had also cheated the party, most blatantly, out of the 2008 election.

Indignant and angry, Evan sits hunched at the dining table with his muscular forearms braced in a semi-circle in front of him���a stance like that of his first #ThisFlag video. Our conversation around the election and the ensuing violence pauses when, after dinner, we attend the first International Congress of Youth Voices, where our son is a delegate. As we listen to the passionate presentations, Evan is visibly heartened. One of the congress mentors is Congressman John Lewis, the much-revered civil rights leader who once worked with Martin Luther King, Jr. When Congressman Lewis speaks of the necessity of getting into what he calls ���good trouble��� and ���necessary trouble,��� his words strike a chord with us all. By the end of the evening, Evan is the first to stand in applause. Soon after, he leaves California to return to Zimbabwe.

In the words of others

I am now keen to know, with the passage of time, what people think of Evan. In Zimbabwe, I ask everyone who will speak with me���from young to old, black and white, formally educated or not, rich and poor, professors, students, artists, and business leaders. Similarly, I ask Zimbabweans in the diaspora���in South Africa, the U.K., and the U.S.���many of whom left Zimbabwe either because of the country���s economic collapse or simply to escape Mugabe���s brutal ruling party. Everyone I ask expresses admiration for what Evan did, or attempted to do. Most, however, only seem to know a small part of his story and few are aware of his ongoing work within civic society, which includes mobilizing for clean water services in the wake of a cholera epidemic.

Of the many who praise Evan, some know him from his church, others from what they have heard or read in the news or social media, and one from a chance encounter at Avondale Shopping Center where, in the carpark, they had discovered a shared love of Land Rovers. People describe Evan as a ���good person,��� as ���grounded,��� ���level-headed,��� ���a church man of morals,��� ���humble,��� and a man of ���Presidential potential.��� Several highlight the fact that Evan never set out to be a political leader and that his aim all along was to engage citizens���to start a citizen���s movement. He had resisted joining any political party and refused to run for President as many had wanted him to do. Nevertheless, one Pan-African businessman suggests that Evan ought to have done a better job of acknowledging the activists that came before him (such as Morgan Tsvangirai, a respected leader of the opposition MDC).

One student says that in a country like Zimbabwe where most people are religious, Evan could have done more to harness the power of the pulpit. Others say that Evan should not have ���run away��� from Zimbabwe after his first arrest in 2016. In a heated conversation between a group of Zimbabwean students studying at the University of California, Berkeley, one claims that had Evan stayed in Zimbabwe just two more weeks in August of 2016, something ���fundamental��� would have happened. ���Yeah,��� quips another, ���he would have been dead!��� Others make the point that so much was beyond Evan���s control. Funding was a challenge, says a struggling Harare-based entrepreneur, explaining how difficult it was for Evan to get his message to the rural communities where people, though connected to social media, didn���t have funds to buy ���bundles��� (data packages) to download his videos.

Many blame Zanu-PF as well as ex-President Mugabe for destroying Evan���s credibility by pushing the story that Evan was backed by Western sponsors. Also, as one businessman puts it, Zimbabweans had been conditioned to see their opposition leaders (such as Nelson Chamisa and Tsvangirai) beaten up and because Evan never appeared to have severe cuts or visible bruising, this made some people suspicious.

In his own words

When Evan speaks, his passion and oratory skills are reminiscent of other preacher-activists such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Bishop Desmond Tutu. His speech has a Biblical ring to it when he uses phrases such as ���the least among us,��� ���those who are heavy laden,��� or references ���widows and orphans,��� and occasionally he quotes scripture. He has an ear for accents and a natural feel for the poetry and rhythm of language. What is also striking is the conviction and passion conveyed through his words.

Evan becomes particularly animated when he speaks of some of the most marginalized people who have had a lasting impact on his life, including prisoners he met while at Chikurubi.

He is humble when talking about himself, frequently referring to others as brighter and more courageous. Those that he mentions as having inspired him are not the famous people he has sometimes been compared to, but ordinary, everyday people including his parent���s pastor and a caretaker at Prince Edward School.

When I ask Evan to describe the events following his first arrest, he does so with a sense of timing and drama that keeps me rapt, sometimes adding deadpan humor at the tensest moments of his story. When being transported���handcuffed in the back of a pickup truck���to his first court appearance, he describes the moment when he asks the heavily armored guards if he might pray with them and, to his surprise, they all lower their weapons and close their eyes. And when recalling his first stint at the notorious Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison, he describes the way prison guards looked at him as though he were a rare, wild animal caught in a residential area. They were surprised to find him so young and so short.

Evan is not only quick to draw on humor, often poking fun at himself, but he is also candid when chronicling the rollercoaster of emotions felt in the course of his journey. He admits to sobbing uncontrollably and to nearly convulsing on the first night he was interrogated, to struggling to hold back tears when he saw his pregnant wife patiently sitting in court on the following day. Often in the course of conversation, Evan is contemplative, reflecting on what he has learned since the events of 2016 which brought him to national prominence:

One of the things I learned when people responded by calling me a sellout [was] the realization that if you���re going to do it, you have to do it out of conviction and not out of the applause or what people want to hear. The way I learned the lesson was that my two major arrests had one very distinct difference. The first had thousands of people gathered there. The second, when I was arrested at the airport, there was nobody. No one! It was a shock but also the penny dropped that if you���re going to do this, you can���t do it for the crowd because they���ll be there when it���s exciting, but when it gets tiring, they don���t have an obligation to be there at all.

I lost a lot of friends along the way when I started speaking out. I still have one or two but it���s a very small circle. I���m in one of these strange situations where you feel like everybody knows you, but you know no one.

One of the fears in the kind of space that I���m in right now is that I would disappoint the people who do love me [���] Sometimes I���m caught off guard, I���m not in the space of “here���s the other cheek.” That���s why, as a pastor, it has been such a terrible thing for me and I���ve said to people: “you know what, I���m not speaking as a pastor. I���m speaking as an ordinary person who has hurts, who has frustrations, who has fears, and who is concerned about how they���re going to deal with a future that has been messed up by someone who���s no longer here.”

When people look at me and my life through the lens of the high moments���the different nominations for prizes and the invitations to speak at these high-level gatherings, or amazing institutions of learning���they don���t understand the aspect of cost. None of that could ever be a replacement or a reward for being away from my kids for three years, missing all of their birthdays. None of that could ever help me explain why my daughter would ask me, after she hadn���t seen me for fourteen months, if I���m her dad. So sometimes people see my life through the lens of some of those things and they think that the cost is easy, but it���s quite a cost to bear. The prison arrest and the attempted abductions and threats to life���all put a value on how much I value my family. I���m prepared to die for them, I���m prepared to go to prison for them, so that my children understand what freedom means, what justice is. And it���s my hope that my kids will learn earlier in life what it means to fight for what you believe in. In many ways, it started off being about my family, but it has become much bigger. Sometimes I regret it. Many times, I regret it. When I speak in public, I have to find the courage to be brave for everyone else, to not say I���ve had enough, to not say I can���t take it anymore even though I feel like that a number of times. It���s just not the thing you say when you happen to be the symbol of hope for everybody else.

Evan at an Avondale coffee shop. Harare, July 2017. Image credit James M. Manyika.

Evan at an Avondale coffee shop. Harare, July 2017. Image credit James M. Manyika.More arrests

January 16, 2019���In the dead of night, armed men arrive at Evan���s Harare apartment and attempt to abduct him. They assault the caretakers in his block and try ramming down his front door. Unable to get in, they send police to arrest him early the next morning. The arrest is filmed by neighbors and posted online. Evan is remanded and charged with inciting public violence and for being in support of the trade unions who called for peaceful demonstrations protesting the doubling of fuel costs. His charges are later escalated to that of subverting a constitutionally elected government���identical to the charges leveled at him =two and half years earlier. He is thrown back into Chikurubi. This time, he���s placed with fifty-three others in a cell measuring just eight by five meters. Many of these inmates had been rounded up in the course of the fuel protests. Some have broken bones while others have open wounds from police beatings. A few are minors only sixteen years old.

January 30, 2019���Evan is released on bail. He is suffering from a chest infection. One of the first questions a reporter can be heard asking on a posted video is: ���Were you beaten?��� As in 2016, the conditions of his bail are stringent. At each successive court date, Evan���s case is kicked down the road. Between January and September 2019, he makes ten court appearances.

Meanwhile, things in Zimbabwe continue to deteriorate. An Amnesty International report published in August describes Mnangagwa���s first year in office as marked by a ���systematic and brutal crackdown on human rights including the violent suppression of protests and a witch-hunt against anyone who dared challenge his government.��� On August 26th, Evan writes an op-ed for TIME Magazine describing the depth of the nation���s economic hardships and the government���s brutal response to those who dare to protest. Then, in September, the unimaginable happens again. Ex-President Robert Mugabe is dead. He was ninety-five years old.

September 6, 2019���On the day Robert Mugabe dies, I am in Cape Town participating in South Africa���s Open Book Festival. In a surreal moment, I awake to the news of his death from the animated chatter of Zimbabwean housekeeping staff that I can hear standing outside my hotel room. I understand enough of what they are saying in Shona to guess that something significant has happened. I switch on the TV and that���s when I hear Zimbabwean government officials speaking of a deceased Mugabe as though he were a hero���the same officials that had cheered at his ousting less than two years earlier.