Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 198

November 11, 2019

A worthy ancestor

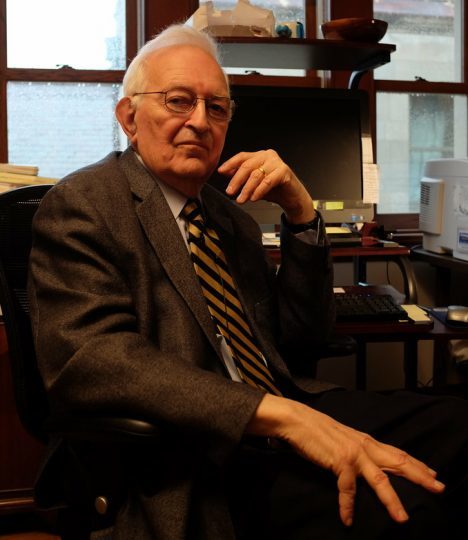

Image from Immanuel Wallerstein interview with David Martinez, Yale University, 2015. Credit Brennan Cavanaugh via Flickr CC.

Immanuel Wallerstein passed away long before another world was made possible. His hope that somehow���out of this final crisis of the world���s capitalist system���another world would emerge, still hangs in the air. For those of us who worked closely with him in the last two decades (in the International Sociological Association and with the project The World is Out of Joint), his mentoring will be missed. It was in and through his stewardship that saw me lead a wonderful ensemble of sociologists to produce��Gauging and Engaging Deviance 1600-2000��in 2013.��Last but not least was his his support and contribution in constructing the Charter for the Humanities and Social Sciences in 2011 in South Africa, which in turn spawned the National Institute for the Humanities and the Social Sciences.

I was fortunate to be elected president of the South African Sociological Association in 1996, during Wallerstein���s tenure as the president of the International Sociological Association. It thrust me onto the global stage thanks to his Regions initiative. It allowed me to work closely with Teresa e Cruz Silva to gather Southern African sociological voices and allowed us to meet wonderful Latin American scholars, such as Anibal Quijano and Raquel Sosa Elizaga. My first tentative step in India was also thanks to him. Our host was non-other than TK Oommen, who is now being forced to submit his CV to the fundamentalist authorities of the JNU administration to keep his Emeritus status. It was in turn TK Oommen, Hermann Schwengel and I who created the tri-continental Global Studies Masters Program. My indebtedness to him runs into reams of paper.

Many of us after all owe to him the privilege of going global and local, even though we got lost often, in-between.

Image from Immanuel Wallerstein interview with David Martinez, Yale University, 2015. Credit Brennan Cavanaugh via Flickr CC.

Image from Immanuel Wallerstein interview with David Martinez, Yale University, 2015. Credit Brennan Cavanaugh via Flickr CC.Most important was his contribution to, in his language, the vital anti-systemic movements of the late 20th century: African and Latin American national liberation movements; their successes and failures their limits and possibilities. Although he was fond of Frantz Fanon, Amilcar Cabral, Julius Nyerere and Aquino de Braganza, the Mozambican scholar and activist, he was gentler in his critique of the aspirant national bourgeoisies on the continent. Whereas for them the failures were subjective and a question of the wrong choices that led to neo-colonial nightmares, for Wallerstein they were objective, a product of world systemic situations that created insurmountable obstacles to choice. This idea he carried over to his assessment of South Africa���s ruling party, the ANC, in the late 1990s.

Later on, he was to embrace��with open arms the varied movements that came to constitute the World Social Forum and see in their variety a strength that ought not be abandoned. They were about the substance of an alternative as opposed to formal politics that were only defensive reactions to a weakening status quo. In this he kept the spirit of world-historic moments alive��� 1848, 1968 and 1994���revolutions that failed but that have changed the world. The year 1994 although generous to South Africa has its jury still out of court, the dismantling the last race autocracy in the world has led to a serious impasse. We just hope that Wallerstein was right and that the proliferation of racism and authoritarian restorations everywhere are but the final kicks of a dying donkey.

Image from Immanuel Wallerstein interview with David Martinez, Yale University, 2015. Credit Brennan Cavanaugh via Flickr CC.

Image from Immanuel Wallerstein interview with David Martinez, Yale University, 2015. Credit Brennan Cavanaugh via Flickr CC.What was Wallerstein���s contribution? That a world capitalist system was in creation since European foraging and settlement; slavery and the construction of race were key to its creation; that the industrial revolution was not a ���virgin birth��� but a consequence of it; that the system was defined by cores and peripheries; that this system of endless accumulation has its booms and slumps; that European hegemony established a system of inter-state relations; that labor, social and anti-colonial movements have been the animus of change; that we are living through a final crisis that is by now insoluble within a capitalist carapace; that Eurocentrism and the disciplines that were created in and through European hegemony (and colonial and imperial networks of power) have outlived their fictions; that we need��to open up the social sciences and make them serve an array of human forms of flourishing.

But the world is out of joint! In Wallerstein���s words:

Who will win this battle? No one can predict. It will be the result of an infinity of nano-actions by an infinity of nano-actors at an infinity of nano-moments ��� But this uncertainty is precisely what gives us hope. It turns out that what each of us does at each moment about each immediate issue really matters ��� This is an intellectual task, a moral obligation, and a political effort.

November 10, 2019

The identity politics of wax print

Image still of the director Aiwan Obinyan from Wax Print Film.

���Is wax print African?��� Debates about the authenticity of African print or Dutch wax as it is also called, flare up regularly, with some arguing the fabric is un-African, even Dutch. When English designer Stella McCartney was accused of ripping off African designs by using wax print in her Summer/Spring 2018 collection, some of the push back questioned whether the fabric could even be called African.

This same inquiry���whether wax print is even African���lies at the heart of British-Nigerian filmmaker, musician, and fashion designer, Aiwan Obinyan���s Wax Print Film. Interlacing interviews with makers, sellers, and wearers of African print, with narration about her own personal familial history with the fabric, Obinyan���s 2018 documentary, as its subtitle promises, takes us on a journey through ���1 Fabric, 4 Continents, 200 Years of History.��� In so doing, Wax Print Film makes poignant observations about counterfeiting and cultural identity.

Although wax-resist-dyeing existed for centuries in many regions of the world, the specific style that informed wax print was Javanese batik. The Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) tried to machine manufacture batik in bulk and thereby crowd out local artisans. However their factory printed cloth developed ���cracks��� in the wax, and subsequently in the dye, which made it unattractive to the Javanese. These same ���cracks��� were characteristic of African fabric, and were appreciated for ensuring that no two pieces could ever be the same. The Dutch therefore shifted their focus to the West African coast. With the help of local market women, they adapted the color palettes and patterns of their factory-made fabric to match local demands. Over the decades, designs such as ���sword of kinship,��� ���the ungrateful husband��� and ���you fly, I fly��� remain bestsellers because they so successfully match the tastes of their African clientele.

Today, Vlissingen & Co. (VLISCO) one of the first manufacturers of wax print for the African market in 1848, is still one of the industry���s biggest players. But fake-VLISCO prints from China also now capture significant shares of the market. Wax Print Film considers the detrimental effects that the popularity of these ���modern��� European and Asian prints has on the demand and profits for more traditional, locally-produced fabrics such as kente. It also asks insightful questions about the nature of counterfeiting e.g. how different, really, are the Chinese attempts to copy Dutch wax today, from the Dutch attempts to copy Javanese batik nearly two centuries earlier?

Visually, the film contains some delightful rhymes both about the wax-resist-dyeing process and about working with fabrics as a designer. Among a group of female-dyers in Ghana, Obinyan tries her hand at applying wax onto cotton fabric before it is dyed and then watches the rest of the process, right up until the batik is hung out to dry on lines outside. And later, in the Netherlands, we watch her follow this process again, this time on a much larger scale: in a factory with massive machines and wax rollers. The juxtaposition of the two processes, aptly underlines her point about how wax print has been tailored to African tastes. Although it is possible nowadays to dye fabric without cracks, the cracks are still artificially manufactured onto the fabric���in essence, she tells us, the imperfection has been perfected. Added to the cinematography, which highlights the richness of the fabrics��� colors, Obinyan���s enthusiasm for wax print and her excitement at being witness to the process of its making are infectious.

A second visual parallel exists between the stories of Obinyan and her grandmother, Mrs Elisabeth Oboh. Following the observation in an earlier interview that textile practices are intergenerational and passed down through families, it is endearing to learn how her grandmother was able to build a successful career for herself at a difficult historical period by teaching women to sew, and then to see later how Obinyan herself has made a living designing and selling clothes made with wax print.

Another nice touch, following the interviews where various Afro-descendents speak about wax print as a marker of blackness, is to watch Obinyan narrate her own struggles with identity growing up as a Black-British child in the 1980s, and to hear how the decision to proudly wear African print represented her own gradual growth and decision to stop ���hiding��� or being ashamed of this part of her identity.

That said, it would have been interesting to hear how young Africans on the continent, and not only in the diaspora, think about and use wax print. Though the film interviews women who make and sell wax print in Ghana and Nigeria, it does not engage any young, continental Africans on the subject of wearing wax print, not in the same way that it speaks to festival-goers at Afropunk in Paris, or Cutie BiPoC in Berlin. Given that Wax Print Film insists that the tastes and preferences of African customers shaped the fabrics��� early development, neglecting to interview present-day customers in Africa is a missed opportunity.

Between its personal reflections, observations of the industrial process, vox pop and expert interviews, historical and archival interludes, etc. Wax Print Film occasionally feels like it is juggling too much. This is particularly the case in one of its final scenes, where the director and producer, having just been through a heart-wrenching tour of the Elmina Castle, speak about the hurts done to our black ancestors through slavery, religion, capitalism, etc. These meditations on black pain, though important, seem not to have much, concretely, to do with the subject of wax print.

And yet, all this is perhaps redeemed when, at the end, Obinyan answers the question she has been asking everyone else throughout the film: ���Is wax print African?��� Acknowledging its multi-continental origins, she ultimately ties the fabric���s identity to the black experience itself:

���The fact is, when I walk into a room, my skin speaks before I do and people see a black person before they hear my accent and realize that I���m British too, and so it is with wax print. It���s instantly identified with Africa and Africans before people are made aware of its vast history. So academically, and historically, it���s a fusion of ideas, culture and techniques, but to me it���s African.”

November 7, 2019

The Kenyan Hunger Games

Nairobi, Kenya. Image credit Amy Ashcraft via Flickr CC.

About a month ago, Jeff Koinange, a leading news anchor and household name in Kenya made a fervent plea to Kenyans on behalf of his 13 year-old guest, Bianca Wambui who had been diagnosed with breast cancer but could not raise enough money for treatment. In an hour, 2.4 million shillings had been raised.

The comments on the tweet by Citizen TV announcing the success of their fundraiser were varied and ranged from praise of Koinange and tweets by people moved by the generosity of Kenyans. However, like a dark cloud on a sunny day, one comment asked, ���What about the other Bianca���s out there?��� A question which brought to the fore the unsustainability of philanthropy as a method of healthcare management.

In 2015, Denis Onsarigo ran a story titled “Desert of Death,” an expose of toxic waste dumping in the 1980s carried out by an American Oil Company, Amoco in Marsabit County in Kenya during an oil exploration mission. Buried in pits dug in the earth was toxic mercury and arsenic that percolated into the water table and contaminated the drinking water in the wells. The residents and livestock drunk the poisoned water and it began to slowly kill them. The rate of throat and stomach cancer increased and in 2011, two residents were referred each week to hospitals in Meru town or Nairobi city for a biopsy. Most of the time, the residents could not afford the transport or medical bills for treatment.

But this skewed form of existence, where one���s life or death depends on the philanthropy of others, who determine whether or not your story is worthy of a prime-time feature, does not only end with medical stories, it extends to how one earns their daily bread.

These are the hunger games of capitalism where the sponsors or overlords are corporates like Safaricom or Coca Cola, or individuals like SK Macharia, who owns Citizen TV. Their scouts are Jeff Koinange and other influencers who have the clout to lift your life from poverty or fund raise a lifesaving medical procedure.

To see just how pervasive this analogy is, look at the format of popular game shows like East Africa Got���s Talent. The participants showcase their talent to a team of judges who decide whether or not their talent qualifies them for the next round bringing them closer to USD$50,000 cash prize, which could mean a lot of things to the participants, such as better housing, education, healthcare, professional nurturing of their talent and so on. Never mind that their labor power, which is their talent is uncompensated while Citizen TV which airs the show in Kenya makes their cut from advertising, meanwhile Rapid Blue, the South African Company that produces it, rakes millions through sales of the show.

In July, the story of Kevin Obede, a first-class Actuarial Science Graduate who was living on the streets due to unemployment grabbed the headlines on prime-time news. It was tear jerking story. Though his pain and hopelessness were not uncommon among many other graduates around the country, within a week of the story airing, he was flooded with job offers.

On the #IkoKaziKe���a twitter hashtag that helps Kenyans hunt for work���the number of graduates looking for jobs far outweighs the job listings and #unemploymentdisasterke, the testimonies of “tarmacking” (slang for job hunting) can scare you into accepting whatever job is offered to you. Pictures of graduates holding placards of their qualifications in traffic becomes a game of who will spot you, take a picture of the card, post it on social media and when it goes viral, then the job offers come flooding in. But then the participants in the “game” became too many and the posts and pictures lost their effectiveness so they turned to TV. One feature by Koinange and you have unlocked the level of prosperity that is otherwise unreachable in the average person���s life.

Another example is KCB Lion’s Den. Here, aspiring entrepreneurs pitch their businesses to a team of judges���the “lions” who are a group of successful business moguls who have the cash and know-how of what it takes to succeed. As the prey, you have to impress these “overlords” or corporate sponsors who have the power to turn your life around.

There is nothing wrong with competition, but if the ground is uneven, is it now a fair fight or simply playing God?

In the Hollywood film, The Hunger Games, the Capitol���the wealthy city-state of the center of the world���stages a series of competitions involving the 12 districts in a fight to the death scenario where the winner gets access to a better life than they lived in their districts. The games were set up by the Capitol as punishment to the 12 districts who had staged a rebellion years before. The districts are kept impoverished and each year, a boy and a girl from each district are put forward as representatives or tributes in the games. If one has sponsors who give you gifts critical to the winning of the games, then you have a better chance of making it. It is a competition for your humanity and the odds are unevenly stacked among the poorer districts in comparison to the wealthier district 1 and 2, who train their tributes for the games from birth.

We should think of the “districts” as the Northern Frontier Districts, the rural areas and urban settlements. These were areas that were marginalized during colonialism and remained marginalized during flag independence and beyond, when our country���s founding leaders entrenched colonial violence by taking for themselves the land that belonged to the peasant farmers who had been dispossessed during colonialism, and later on through structural adjustment policies by the World Bank and IMF that heralded the neoliberal era.

Wambui came from Huruma, a ward in Mathare constituency. Mathare first started as a quarry where commercial stone mining took place. Most of the miners who worked at the quarry also lived there in caves hewn out of the rock. Later on, the British colonial government allowed them to build shacks. During the state of emergency, the crackdown of Africans suspected to be part of the Mau Mau mostly affected Mathare as it was believed to be the center of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, also known as Mau Mau. Their homes were demolished during the raids. Even after the war for independence, the new government led by Jomo Kenyatta did nothing to make the lives of those who lived in Mathare better, and instead asked them to go back to the rural areas as they made Nairobi look like a slum. Yet, where was the land? Had they not come to Nairobi because of precisely this reason���to find an alternative livelihood after being dispossessed of their ancestral land?

As you can see, one can draw parallels between the dystopian Hunger Games in Panem���the fictional country were the games take place���and the Hunger Games of capitalism in Nairobi.

Therefore, if you do not get a sponsor who will help you win at the games, you will die of cancer like the residents in Northern Frontier Districts who have to choose between sustaining their families or paying for cancer treatment, and who do not have the smartphones to ask for funds from well-wishers or get on Koinange’s show, or sink into debt as you struggle to pay a medical bill in, or travel back home empty handed if your talent or idea does not please the judges of a reality game show. Perhaps the biggest irony is that these shows serve as weekend or weekday evening entertainment for the workers in the “districts” before they wake up to serve capital. For them (the workers), the taste of hope stays fresh on their tongues and the thought, “If only I get on the show,” are carried like a prayer until the next opportunity to be on a primetime reality show to share their story. The corporates like Safaricom that sponsor the shows are absolved of the crimes of their exploitation of labor and complicity in this cruel capitalist system because they made one person���s dream come true on a game show.

At the end of the day, it is a zero-sum game between capital and labor. A game where capital is always the winner and doles out the “spoils”���healthcare, right to dignified work, food to whomever is lucky and whoever wins in the diabolical game of life in Kenya.

This is an edited version of a post previously published on ROAPE.net.

November 6, 2019

James Barnor, ever young

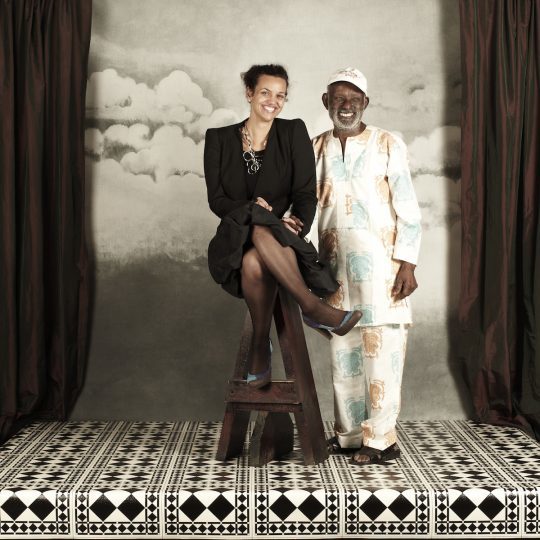

James Barnor and Ren��e Mussai, 'Ever Young' studio at Rivington Place, London, 2010. Photo by Zoe Maxwell, courtesy of Autograph,��London.

This article is being published online on Africa Is a Country only. The images appear courtesy of Autograph, London. These images are not under a creative commons license. These images are not for further distribution to any third party without prior written consent by Autograph, London.

In October 2010, I was one of seven African curators invited by the Tate Modern in London to talk about our recent exhibitions. During those few days we visited, as a group, Autograph at Rivington Place, then showing the photographic exhibition James Barnor: Ever Young. I was struck by this exhibition: the conceptualization, the history contained in the images, the power of the photography and of the curating, the beauty of and in the images, the finesse of the printing and the overall installation. A few months later, in 2011, I organized to show the exhibition at the South African National Gallery (SANG)���in partnership with Autograph and with the assistance of the British Council���where I was director at the time. It was the first tour of the exhibition following the inaugural Autograph show and significantly, the first���and perhaps only���to the African continent thus far. James Barnor attended the opening at the SANG and was so excited to see his images displayed abroad, he paid his own way from London to Cape Town to be there again for the closing week of the show a few months later.

Fast-forward seven years and guess who I ran into at the 2018 Paris Photo last year, and then in June this year as a fellow resident artist at the Cit�� internationale des arts in Paris? Why, none other than the same master photographer James Barnor! I caught up with the legendary Ghanaian photographer on the occasion of his 90th birthday celebrations and his latest solo exhibition entitled Colors then running at Galerie Cl��mentine de la F��ronni��re in Paris.

James Barnor, Eva, London, 1960s. Courtesy Autograph, London.

James Barnor, Eva, London, 1960s. Courtesy Autograph, London.Barnor filled me in on his rags to riches story: the exhibition Steve Flynn and Rachel Pepper were involved in organizing at the Acton Arts Festival in 2004 via the Acton Arts Forum; his subsequent inclusion in the exhibition Ghana at 50 curated by Nana Oforiatta Ayim at the Black Cultural Archives (BCA) in London in 2007; and following that the meeting between curator Ren��e Mussai and himself that led to his first major solo entitled Ever Young: James Barnor at Autograph, London in the autumn of 2010, which also doubled as his retrospective exhibition, touring internationally since.

The Autograph show set the standard and art professionals, institutions and collectors started to take notice of Barnor���s work with the exhibition travelling to Cape Town; the Impressions Gallery in Bradford in the United Kingdom (2013); Galerie Cl��mentine de la F��ronni��re, Paris (2015); Stony Island Art Bank, Chicago, USA (2016); Black Artists’ Network in Dialogue (BAND), Toronto, Canada (2016); The Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA (2016). This was after a smaller iteration exhibition preview at Harvard University���s Rudenstine Gallery in 2010, a few months prior to the opening at Autograph. As a result Barnor���s work has since been acquired by international private and public collections in the United Kingdom such as the Eric and Louise Franck Collection (now at Tate Britain), Government Art Collection, Victoria & Albert Museum, and the National Portrait Gallery in the UK, as well as further afield including the Wedge Collection (Canada) and Mus��e du quai Branly (France), etc.

Barnor���s photographs were first formally displayed in Ghana in an exhibition at the British Council and Silverbird Lounge, Accra Mall (2012). Since then his pictures have been included in group exhibitions on photography held at Nasher Museum, Duke University, USA (2012); Tate Britain, England (2012); Tropenmuseum, Netherlands (2014) and in 2015 at The Photographers��� Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum and Foam Fotographiemuseum, (Netherlands).

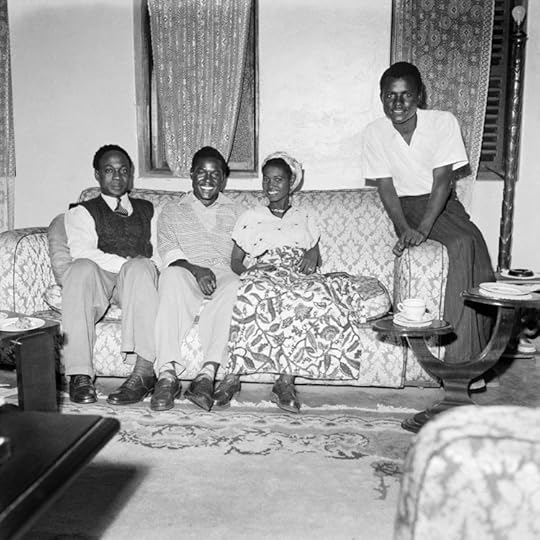

James Barnor, Self portrait with Kwame Nkrumah, Roy Ankrah and his wife Rebecca, Accra, c.1952. Courtesy Autograph, London.

James Barnor, Self portrait with Kwame Nkrumah, Roy Ankrah and his wife Rebecca, Accra, c.1952. Courtesy Autograph, London.Since his gallery Cl��mentine de la F��ronni��re showed Ever Young: James Barnor in Paris (2015) in partnership with Autograph, it has been busy days with Barnor���s work presented at the 11th biennale des Rencontres de Bamako, Mali (2017), Mus��e du quai Branly, vitrine jardin, Paris, France (2017-18), Mupho Mus��e de la Photographie, Saint Louis, S��n��gal and Gallery 1957, Kempinski Hotel, Accra, Ghana, the latter two in 2018.

The interview is based on a spontaneous ���stream of consciousness��� (her words) via on-going email conversations since June 2019 with Ren��e Mussai.

Riason Naidoo

What was it like to see James Barnor’s work for the first time?

Ren��e Mussai

The writer, artist and curator Nana Oforiatta Ayim kindly introduced me to James in early 2009, if I remember correctly, after��she had organized an exhibition at the Black Cultural Archives for Ghana���s 50th anniversary of independence in 2007, showing a selection of existing prints from Barnor���s archives. At this time, we were in the middle of a Heritage Lottery-funded archive program at Autograph, with the mission to promote and preserve the work of key���and often unrecognized���artists working in photography and cultural identity politics, so the timing was perfect.

Encountering a treasure trove of negatives, vintage prints, and transparencies reflecting the breadth of his practice spanning sixty years in a seemingly “ordinary” apartment suite in the Elderly People���s Home in Brentford, where James Barnor still resides today, was overwhelming and humbling ��� in many ways a dream come true for a curator with a vested interest in the archive: such incredibly fascinating history, and��culture, stored in an��array of Tupperware [food containers], plastic bags, cardboard boxes, often��still inside��original transparent or brown paper negative pouches, with hand-written notes to contextualize and���importantly���James��� voice and remarkable memory to give meaning and context to it all ��� That day was a great moment, and one I will always be grateful for���to both James, for his work and his trust, and Nana, for the introduction that opened the door to a fruitful, long-term collaboration with the artist.

James Barnor, Drum cover girl Marie Hallowi #1, Rochester, Kent, 1966. Courtesy Autograph, London.

James Barnor, Drum cover girl Marie Hallowi #1, Rochester, Kent, 1966. Courtesy Autograph, London.Over the past decade, and intensively between 2009-2011, I���as well as colleagues working in the team���have spent many, many hours listening to James�����stories, his transatlantic journeys, while researching his extensive archive of photographs ��� It���s been a��pleasure and a��privilege.��As you know, and anyone who has met James knows, he is an endlessly fascinating person: he epitomizes ���(for)ever young��� perfectly, and poignantly.

Riason Naidoo

What was going through your mind?

Ren��e Mussai

Joy,��curiosity and the overwhelming sense that everything we have done, collectively, as an organization towards the development of this new archive���a photography research program focused on showcasing post-war culturally diverse photography and different “missing chapters”���and personally as a curator working in this field, was culminating in this moment. The main objective and stated mission of the archive program I was leading at the time was to ensure that important but often overlooked practitioners like James Barnor and their crucial contribution to the cultural/global history of photography are not forgotten. The intention was to advocate for their practice to be recognized as key ���chapters��� missing from the wider narratives: re-introduced into mainstream, for lack of a��better word, cultural histories of art or photography as well as the collections of major institutions who can ensure the legacies of the work long term.

As I researched James Barnor���s archive, which was later temporarily relocated to Autograph, I was amazed to��find ten-thousands of negatives���many still in their original Kodak sleeves, unopened since the 1950s and 60s when they were originally produced���and even more so amazed to see that the work he produced for Drum magazine was in fact shot in London, featuring a multinational host of aspiring black cover models, to then be redistributed on the continent ���

This was an archive of images that��capture individually, and more so collectively, cultures��in transformation, new identities coming into being���both “here” e.g. UK and “there” e.g. Ghana���which��brilliantly��illustrated��the��fragmented experience of migration, of modernity, of��diaspora formation, the shaping��of��cosmopolitan, modern societies and selves, of social mobility, and��changing��representation of blackness, desire and beauty across time and cultures �����I personally do not know of any other African studio photographer from that period who left the continent to practice abroad���professionally, as well as to study���whose camera captures such a diverse range of subjects, in and outside the studio confines, and whose work travels���spans continent���in the way James��� photography does.

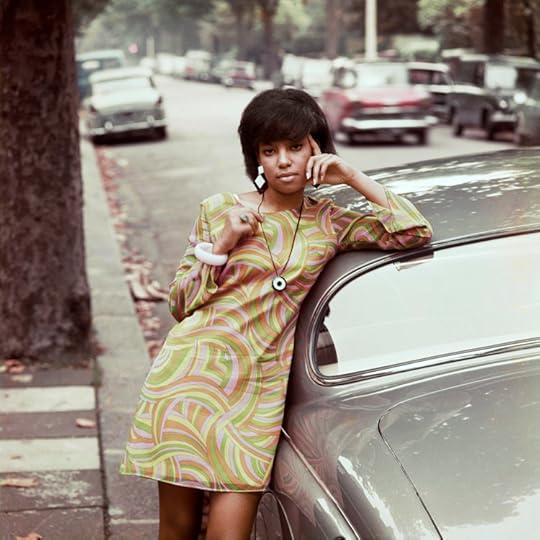

James Barnor, Untitled #1, Drum shoot (unpublished) at Campbell-Drayton Studio, London, 1967. Courtesy Autograph, London.

James Barnor, Untitled #1, Drum shoot (unpublished) at Campbell-Drayton Studio, London, 1967. Courtesy Autograph, London.A majority of the images that I eventually selected for the exhibition had not been seen before, in a curated exhibition���the original film stock, untouched for decades, was digitally preserved first, then later printed from restored negatives and transparencies. My curatorial objective was to build a show that spoke to different chrono-political and transcultural moments: the “here” and “there” in the 1950s and 1960s respectively, as mentioned earlier ��� to create a curatorial dialogue across time and place. Part of this story was to highlight Barnor���s own extraordinary transatlantic journey, and how that impacts on and cross-pollinated, if you will, his practice: after a decade of practicing and studying in the UK, he returned to Ghana with the gift of color photography in the early 1970s, opening one of the first���if not the first���color processing laboratories in Accra ��� So, one of the things that always struck me was how his archive��speaks not only of the��journey of the photographer, but also to the��journey of the medium of photography itself, as it evolves and expands across the world.

Riason Naidoo

Can you take me through the process from that first moment of meeting James to the exhibition at Autograph? (Please, if you can, also describe the technical details of digitization of slides, printing, storage, etc.)

Ren��e Mussai

I first met James a few months before his 80th birthday, and on his birthday, I told him that we had just secured the first of many exhibitions to come: at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was over the moon ��� I remember him telling me that ���for someone with no secondary school education or A-levels������his words!������this was quite something ������ The exhibition opened there in the spring of 2010, as a prelude to the retrospective at Autograph later that same year. At Rivington Place his work was shown [in the main gallery space on the ground floor] alongside a display of W.E.B. Du Bois��� The Paris Albums 1900 [displayed in the smaller space upstairs], to open a conversation between photography and the politics of representation 110 years apart. At Harvard, we also held an exhibition-opening symposium on photography and diaspora, which I had the pleasure to moderate, with key figures in the curatorial and scholarly field: the late Okwui Enwezor, Deborah Willis, and Kobena Mercer ��� I believe it may be online somewhere?

During this period���every time James Barnor came to visit us at Autograph, he was laughing out loud���or smirking���either way always beautiful to witness���the moment he stepped into the office: there would be a white-gloved archivist buried in boxes of hundreds, thousands of his negatives, busy cataloguing and transferring original material into archival sleeves and boxes; another member of the team, busy scanning prints and transparencies; large computer screens all displaying Barnor���s photographs being digitally preserved, restored and retouched back to their original state, while other colleagues including myself were working on different aspects of “Operation Barnor” that had taken over Autograph���s offices for the time being ��� that time being at least twelve months if not closer to eighteen months! Which, for a small charitable arts organization, is a big investment in terms of resources.

James Barnor, Selina Opong, Policewoman #10, Ever Young Studio, Accra, c.1954. Courtesy Autograph, London.

James Barnor, Selina Opong, Policewoman #10, Ever Young Studio, Accra, c.1954. Courtesy Autograph, London.The exhibition I organized in 2010 emerged as a direct result of this urgent and rigorous initial process of research, cataloguing, high resolution scanning, digital preservation, and contextualizing led by Autograph and our dedicated if small archive team���and, of course, in-depth curation. The show represents only select aspects of Barnor���s archive: James and I often spoke about how many countless other exhibitions could and should be curated in years to come, from his wide-ranging practice. I���m very glad to know that this is now happening, and excited to see what other curators, gallerists and archivists will introduce.

Riason Naidoo

I saw the exhibition at Autograph in 2010. It was amazing. Some prints were blown up really large and worked fantastically well and then you retained the small-scale postcard size of the original photo album prints. What was the thinking behind that?

Ren��e Mussai

Thank you ��� from a curator���s perspective the idea was to create a dialogue or juxtaposition between the several stages of his practice���street and studio, London and Accra���and to represent the quality of his work at different scales: to make a bold statement, if you will. To��introduce his work as not merely an archive of prints related to his country of origin (as it had been seen before, at BCA for example) but as key contemporary artworks reflecting his talent and visual politics of (trans)cultural history and identity, re-positioned in a gallery context, printed, largely, from digitally preserved internegatives���new surrogate large format negatives made from restored scans of the originals. Enlarging the studio���as well as the street���portraits brought all the finer details and intricacies of his prints to life, magnified: his trademark studio figurine, the pigeons at Trafalgar Square, and importantly representing the��Drum��models such as the formidable Erlin Ibreck or broadcaster Mike Eghan larger-than-life. It imbued the works, and his sitters, with a presence and��stature: commanding admiration, and claiming space. Seeing the works at this scale enabled a different viewing experience �����At the same time, I felt it was important to preserve and respect the intrinsic quality of the archive; hence the exhibition featured both, modern and vintage prints. The show was conceived as a transnational dialogue, a curatorial conversation across time, and place, enabling the [art] world and wider community to celebrate a key figure in the global, cultural history of photography.

James Barnor, Drum cover girl Erlin Ibreck at Trafalgar Square, London, 1966. Courtesy Autograph, London.

James Barnor, Drum cover girl Erlin Ibreck at Trafalgar Square, London, 1966. Courtesy Autograph, London.Riason Naidoo

Can you also fill me in on what happened before Autograph and after (SANG) that you were still responsible for? How did that feel as curator of the exhibition and what was it like witnessing James experiencing all that attention for the first time?

Ren��e Mussai

As a curator working within an institution advocating for black photographers to be recognized for several decades (Autograph was established in 1988), it was a wonderful opportunity to be able to help Barnor achieve the recognition he so deserves, enjoys, and importantly���during his lifetime. Too often this happens too late, and/or posthumously. I was very pleased that we at Autograph were in a position to invest the necessary resources at a crucial time, and with the exhibition���s critical international reception, and everything that has happened as a result since, especially the acquisitions by major public institutions as these investments ensure the permanent legacy of his work ���

Working with James���s archive constituted an��important phase in my curatorial career and one I look back to with��pride, and gratitude.��It���s always wonderful to be part of something that���s transformative for an artist���s practice���and especially so for a nonagenarian!���as well as addressing a gap or what we tend to describe as a “missing chapter” in existing narratives.

The exhibition at Harvard���s Hutchins Center (formerly Du Bois Institute) was the first exhibition of Barnor���s work I curated, following the initial phase of cataloguing, digitizing, archiving���it was a kind of ���prelude��� to the 2010 autumn retrospective, if you will. In addition to international touring venues, works were also loaned to several group exhibitions internationally���such as Work, Rest and Play: British Photography from the 1960s to Today, organized by The Photographers��� Gallery and shown at the Shenzen and Misheng Art Museum, Shanghai, China or Swinging Sixties London���Photography in the Capital of Cool at Foam in Amsterdam. Major acquisitions we negotiated resulted in James��� work to be featured in blockbuster museum exhibitions such as Another London: International Photographers Capture London Life 1930-1980 at Tate Britain, London; as well as at the Victoria & Albert Museum as part of Staying Power. These moments are always a highlight: when our curatorial work directly affects the diversification of institutional���or “mainstream”���collecting.

Another highlight was witnessing James Barnor participate on the main stage at the Black Portraitures symposium in Paris, for instance, where he was on a panel with other great African photographers such as the late J.D. ���Okhai Ojeikeire.

James Barnor, Drum cover girl Erlin Ibreck, London, 1966. Courtesy Autograph, London.

James Barnor, Drum cover girl Erlin Ibreck, London, 1966. Courtesy Autograph, London.In 2015, I had the pleasure to edit his first monograph, which was published in 2015 with his gallery Cl��mentine de la F��ronni��re, in partnership with Autograph.

The exhibition is still traveling, on and off���we are currently in the process of confirming the��next iteration of the Ever Young: James Barnor at Casa Africa, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in Spain for 2020.

Riason Naidoo

How you feel about it all looking back?

Ren��e Mussai

When I first met James Barnor in 2009,��I knew then that once preserved, and re-presented within a gallery or museum context, these photographs would be celebrated widely, for the illuminating visual evidence they offer not only of an important chapter now deeply embedded within the cultural fabric of the UK���s national story with regards to race, diversity and��representation, but the wider cultural history of photography and most��importantly: African history, African��contemporary art, Ghanaian��history of independence, global cultural��politics, and visual culture.

Looking back today, after almost a decade of continued advocacy by Autograph, I feel proud that this mission has been achieved ��� and that others are continuing this work and keeping Barnor���s practice in the public eye: my colleagues at Autograph, fellow curators and writers such as yourself, dedicated gallerists such as Cl��mentine de la F��ronni��re, other scholars and graduate students and researchers �����as well as his peers, of course.

But above all, I am delighted that James is��alive and well to enjoy the much-deserved recognition, if late in life, traveling��with his work, meeting new people and forging alliances.

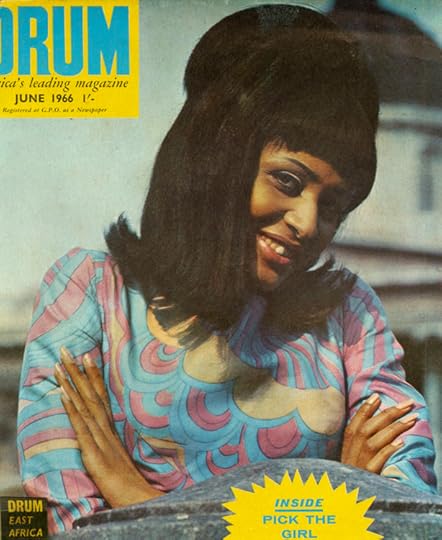

James Barnor, Drum magazine cover with Marie Hallowi, East Africa edition, June 1966. Courtesy Autograph, London.

James Barnor, Drum magazine cover with Marie Hallowi, East Africa edition, June 1966. Courtesy Autograph, London.Riason Naidoo

The book James Barnor: Ever Young was published by les����ditions Cl��mentine de la F��ronni��re��in 2015 in partnership with Autograph. It���s a beautiful publication. Can you talk a little bit about the book and the collaboration, if possible?

Ren��e Mussai

Thank you. The book project was championed by gallerist Cl��mentine de la F��ronni��re and Sarah Preston of Neutral Grey agency who first approached us in 2014, I believe, to discuss a collaboration ��� we then began planning the tour of the original Ever Young: James Barnor exhibition to Cl��mentine���s gallery in Paris. Since there was no publication to accompany the show, the obvious next step was to produce a catalogue and that���s how the partnership ensued. Given that we had already digitized and selected key works from James��� archive over the years, including many additional works not featured in the exhibition, it made sense to collaborate and create a book that reflected the curatorial vision of the inaugural show for James��� first artist monograph, in a series of chapters ��� It gave me the opportunity to finally write the story of the exhibition in my opening essay, and to reflect on the work and process. We also invited the great editor, writer, publisher and broadcaster Margaret Busby OBE and leading photography critic professor Francis Hodgson���who had originally reviewed the exhibition for the Financial Times in 2010���into a conversation with James, which was edited and transcribed for the book. Kobena Mercer���s brilliant text ���People Get Ready������also originally commissioned as an extended exhibition review/essay of our 2010 show by the New Humanist���was also reproduced in the book.

Exhibitions disappear, eventually, but books as you know represent a permanent legacy; hence publishing continues to be of utmost importance: knowing that a copy of James��� first artist monograph is forever lodged at the British Library makes me���and I am sure I can speak on behalf of my colleagues at Autograph���very, very happy indeed. It���s part of our original, and ongoing, critical mission to generate new knowledge, affect wider narratives and advocate for black photographers and artists globally.

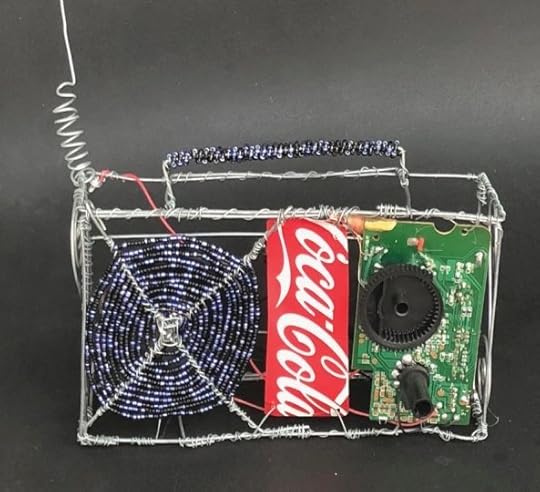

Rugby and rainbows

Image via screengrab from YouTube. Credit World Rugby.

News24 is one of South Africa���s largest media outlets and Adriaan Basson is its editor. Because of its size and reach, News24 is an important site for shaping public opinion in South Africa. As a result, when Basson shares his opinion, many people listen.

My sense of Basson is that he is a good man with good intentions and he wears these intentions on his sleeve when he writes about the Rainbow Nation. This sleeve-wearing and rainbow-writing happens fairly frequently because Basson believes that black and white South Africans ought to be able to live together without acrimony. I am more comfortable than Basson seems to be with the inevitable conflict that comes with living in a multiracial society forged in the shadows of apartheid. Still, Basson and I share the same social instinct: we reach for cohesion rather than pull against it. Despite this, our political analyses are often wildly different.

There are some people in our country who believe journalists are the enemy. There is an army of online bots that have been programmed to insist that Basson himself is a serious enemy of black people. He is particularly targeted by members of the ruling ANC and opposition party EFF. Whenever he points out the moral failings of their leaders, particularly in relation to corruption, he is especially and virulently targeted. But the idea of Basson as an enemy is nonsense. I disagree with Basson in this case���and indeed I often do���but he is not my enemy. The very notion of enemies in a democratic system���rather than competitors or interlocutors���is strange to me. When used in service of genuine clarification, rather than point-scoring, disagreement can be useful rather than polarizing.

If you haven���t noticed, South Africa won its third Rugby World Cup last Saturday. The win was remarkable for a number of reasons, not least was that for the first time in its history the team was captained by a black player, Siya Kolisi. From the Eastern Cape, Kolisi seems particularly aware of his role in history. His post match comments, in which he spoke of the class and racial inequalities in South Africa, is already the stuff of legend. Strikingly also, has been how black South Africans have responded to the win. In previous World Cups, many black South Africans have been ambivalent about whether or not to openly support the team. This time there was no question���the team had no shortage of fans.

Rugby culture in South Africa has been stubbornly resistant to change. But the usual crowd shots of all-white South African crowds at rugby matches���sometimes waving the old Apartheid flag���are becoming a thing of the past. It is precisely for this reason that Kolisi���s captaincy and the presence of a number of other black players in key positions has been so important.

As the historian and rugby fan, Derek Catsam, wrote on this site on Monday, ������This was no ‘quota squad,’ ��� but rather it was a squad led by its black players.” It was a squad that would not have been able to ���win the World Cup without those black players.��� Whites are not at the center of the game anymore and so there is a qualitative shift at play in South African rugby. This is what the homecoming scenes of the boys arriving from Tokyo symbolize. This is what the excitement amongst black people is about.

In this spirit then, let me address my concerns about a recent piece in which Basson writes about the Springboks��� brilliant World Cup win. It seems to me that at its core, the piece misses many of the points that critics of the Rainbow Nation (and of the function of rugby and the Springboks for that vision) have been making for many years. This misunderstanding sets us up for further, deeper misunderstandings that can be exploited over time until they drive people of good will further and further apart.

Basson writes: ���The Springboks have revived the much-maligned concept of South Africa as a rainbow nation with a historic Rugby World Cup championship victory.��� He goes on to argue that the Rainbow Nation, ���has been given a second chance by Springbok captain Siya Kolisi, coach Rassie Erasmus and the team, who emphasised one nation working together after its stunning win over England.���

This is simply not the case.

Try as he might, Basson seems unable to genuinely understand that the problem at the core of the idea of the Rainbow Nation lies in the way it centers the experiences and feelings of white people. This���more than anything else���makes it a hard concept to reuse in this millennium, given all we know about white supremacy and late capitalism.

Each and every day, South Africans are offered opportunities to work together across race and across class lines, even as many white people in this country, who have the power to work towards unity, choose to turn away from the national project.

Basson���s sentimentality���his idea that our nationhood will be made in moments of glamour in which white people play a central role���is seductive. And yet, if the last twenty-five years has taught us anything, it is that a captain and a coach can make us weep, but a rugby match cannot give us a second chance at nationhood.

Day after day, year after year in the news cycle that Basson curates, it is evident that the events that tend to move black South Africans, do not on the whole, move white South Africans. Basson���s idea of the rugby match as a second chance functions as a softcore racial imaginarium in which white people���s inclusion is a prerequisite for unity.

If the team had no white members, would the win have meant this much to our white compatriots? This question gets to the heart of what it means to be South African. For white South Africans it means inclusion (even if they are already over-represented) while for black South Africans belonging means justice and equity���it means seeing a group of young men on the field who are there in spite of every obstacle thrown in their paths.

I remember the heady days of the #FeesMustFall movement. While many white South Africans supported the students in broad terms, there was no mass outpouring from white South Africans claiming that all those black children on the streets provided a glimpse of the country South Africa���s liberators had hoped it might become. Instead, there were a number of self-satisfied opinion pieces pointing out that white children were on the streets too, but far too few white South Africans claiming the struggles of black children as their own.

The almost pathological need to place white people at the center of the national narrative about the future is a blind spot for many well-meaning white people. For too many of our white compatriots, the South African story is built around the fate of white people. This inability to see the future without insisting that the photo frame includes white images represents a strange sort of race-consciousness for a group that often professes not to care about race. The stories that count are their stories even though it is widely accepted at an intellectual level that for South Africa to thrive socially and economically, it is black people who will need to make significant progress.

In spite of the objective facts about what constitutes progress for this country, the desire of so many white people to celebrate stories in which white people play a central role while ignoring the national importance of stories in which black children are the focus, should worry all of us.

The point is not that white people shouldn���t also thrive, but that the idea of nationhood should not be contingent on white people continuing to take up disproportionate space within the national story.

I remain committed to the idea that South Africa can be a place of opportunity and justice for all of us. Yet I cannot see how we will achieve this objective is our white compatriots do not rejoice with all their hearts when black children are uplifted.

The Springbok win is great but it is hard, hard indeed, to watch the frenzy of white excitement about it. It is painfully clear that there would not be such joy if rugby were not seen as a “white” sport. Indeed, Basson���s article begs the question of why it takes a rugby match to spur a reclamation of nation-building when all around us each and every day South African whites who have every opportunity to promote unity in private lives flatly refuse to do so.

If the dream of a united South Africa is truly important then white South African managers will hire young black talent without reservation, without resentment or anger about affirmative action. They will see in the faces of young black graduates a second chance rather than a last resort. If the dream of a united South Africa in which each of us can live to our fullest potential is to be realized then the middle class���white and black���will put their children back in public schools. The segregated suburban schools that have been abandoned by whites stand as a testament to how far we have to go to move beyond the seduction of the glittering moment.

Perhaps this summer, white South Africans who want to keep the idea of racial equality alive will celebrate when the beaches are bursting with black people who are free���wonderfully free!���to bathe and swim and share in the beauty of our country���s coastlines. Perhaps they will remember that once upon a time black people were not allowed on our own shores.

While lying in the sun alongside their fellow South Africans who happen to be black, our white compatriots will be able appreciate that very quietly and without much fuss, day after day, month after month for the last twenty-five years, they have accumulated an extraordinary set of second chances. Perhaps this summer they will re-dedicate themselves not to certain colors in the rainbow but to the vision itself.

November 5, 2019

Can an American TV sitcom get anything ‘right’ about Nigerians?

Promo image from Bob Hearts Abishola.

When American TV network, CBS, first announced that its TV sitcom Bob Hearts Abishola would feature a Nigerian protagonist, a sense of dread came over many Nigerians concerned with their country’s representation in the western media. Just starting with the name ���Abishola������or, rather, its spelling���the title of the show struck many as questionable. Why the ���h,��� when ���Abisola��� is arguably far more common? And how could Bob Hearts Abishola, a Chuck Lorre sitcom, possibly get anything ���right��� about Nigeria and Nigerians? Lorre, known for blockbuster sitcoms (including The Big Bang Theory), is not often associated with nuance.

Nigeria is, on American television, typically reduced to subplots about internet fraud (419 jokes) and other references to, allegedly, endemic Nigerian corruption���when the country is cited at all. Depictions of Nigerian scams have proliferated in British and American popular culture, strengthening racist stereotypes. For instance, the pilot episode of the television series Leverage (2008)���titled ���The Nigerian Job������suggests that all Nigerians are corrupt. Similarly, the Futurama spin-off film Bender���s Big Score (2007) uses a dreaded Nigerian internet scam as a source of terror, pity, and apparent hilarity.

For its part, however, the HBO comedy series Flight of the Conchords (2007 ��� 2009) satirizes the sort of stereotyping that feeds anti-Nigerian prejudice: when the eponymous band���s lovably inept manager, Murray (Rhys Darby), enlists the help of a Nigerian investor, Nigel Saladu (Michael Potts), the other characters assume that Saladu is a 419 schemer, and that the disastrously dim-witted Murray has managed to err once again���this time in a really big way. In the end, however, Saladu emerges as a hero, having demonstrated his keen investment skills and earned a much-needed windfall for Murray and the band. In Flight of the Conchords, essentializing Nigerians as corrupt can only lead to shame and embarrassment for those peddling such parochial views.

Set in Detroit, Bob Hearts Abishola is about the ���unlikely��� romance that develops between a white businessman (played by Billy Gardell, the Mike of Lorre���s earlier sitcom Mike & Molly) and the Nigerian nurse he meets while a cardiac patient. Played by Nigerian-born actress Folake Olowofoyeku, Abishola recalls Saladu in her hyper-competence, which puts the other characters���including, memorably, the physician with whom she, a ���mere��� nurse, works���to shame. (Abishola knows better than the doctor and isn���t afraid to say so, and her willingness to intervene���to act on her hard-won knowledge���saves a patient���s life.) Olowofoyeku���a Nigerian performer playing a Nigerian role���is among the selling points of the series, and she is matched by two other actors of Nigerian descent, Shola Adewusi (who plays Abishola���s meddlesome aunt, and whose rabble rousing comedy style recalls that of Nollywood icon Funke Akindele) and Gina Yashere (who plays Abishola���s closest friend, an incorrigible gossip).

Bob Hearts Abishola does not pretend that African immigrants speak only English, and the series is full of subtitled Yor��b��, featuring, as well, some welcome discussions on the intricacies of the language. The program is very much an advertisement for ���low��� culture���a mere sitcom that is somehow more respectable, more accurate and evocative, than those strenuously ���serious��� accounts of ���Africa,��� like Netflix���s Beasts of No Nation (which can���t even be bothered to identify its national setting even as it makes ample use of Twi).

At its best, Bob Hearts Abishola evokes the Nigerian sitcom tradition, particularly in scenes set in Abisola���s crowded home, which recall Amaka Igwe���s Fuji House of Commotion, a spin-off of Igwe���s popular television serial Checkmate. Tambay Obenson has eloquently described what Bob Hearts Abishola does so well, noting that Gina Yashere was instrumental in the development and execution of the series. Hired as a consultant, Yashere eventually earned a credit as the sitcom���s co-creator, and her oversight pays some obvious dividends: indebted to Bridget Loves Bernie (1972-1973) and other clash-of-cultures sitcoms, Bob Hearts Abishola avoids egregious misrepresentations of Nigeria���including those for which non-Nigerian actors (like Concussion���s Will Smith) have been notoriously responsible.

I expected to detest Bob Hearts Abishola, but I was surprised by how much I liked the first six episodes. The series is full of Yor��b��, and it���s not nearly as exoticizing as typical American accounts of African characters. I tweeted some praise, then deleted the post as soon as I noticed that many users were upset about the show���because of a (rather funny) parody of African chauvinism: there is a memorable scene in which two African-born characters ���troll��� their African-American friend (played by the great Vernee Watson-Johnson) by suggesting that they would date African-American men only as a last resort. Watson-Johnson���s lively character gives as good as she gets, however, critiquing the immigrants��� stereotype-driven hierarchy even as all three women share a hearty laugh over the difficulties of dating and the quest for sex.

As of this writing, over 3,000 people have signed a Change.org petition demanding that CBS cancel Bob Hearts Abishola on the basis of the sitcom���s alleged anti-African-American bias, which, the petition���s author maintains, ���supports the ongoing narrative being proliferated in mainstream media today, that African immigrants are a more desirable class of ���blacks��� in America than American Descendants Of Slavery.��� What the author appears to ignore is the role of two-time Emmy-Award-winner Vernee Watson-Johnson as Gloria, the receptionist at the hospital where Abishola works: as cutting as she is wise, Gloria goes out of her way to mentor the much-younger Abishola in what amounts to a lovely depiction not merely of inter-generational intimacy but also of cross-cultural exchange.

The Change.org petition also claims that Bob Hearts Abishola is being ���presented to a predominantly white network audience������an unsupported assumption that is difficult to maintain at a time of significant demographic shifts, particularly in relation to the medium of television and the platforms on which it is watched.

Bob Hearts Abishola begs the question ���Why Nigerians?������and the answer is perhaps obvious: as the global popularity of Nollywood films, and their growing presence on platforms like Amazon and Netflix, attests, Nigerians are major consumers of popular media, and it makes sense that CBS would target them. Indeed, I know a lot of Nigerian-born Americans who are not only watching Bob Hearts Abishola (on whatever device) but who are also enjoying it���and who are marveling at the extensive use of Yor��b�� on an American network sitcom.

November 4, 2019

What’s the point of opposition politics in Southern Africa?

Fees Must Fall Demonstration 2, Pretoria. Image credit Paul Saad via Flickr CC.

Recently, the first black leader of South Africa���s opposition Democratic Alliance (DA), Mmusi Maimane, stepped down as leader of the party. Maimane had been seen by some as having a real chance to reorient South African politics by tapping into long-simmering discontent with the ANC by many in the black majority who still do not feel seen or serviced by government. The DA also hoped to capitalize on Maimane���s youth���he was only 34 when he took over as party leader. It was, thus, his race and his youth around which the party hoped to rally younger voters, whose support for the ANC is the lowest of any group.

The idea that opposition parties might be able to tap into the large number of underemployed youth and other discontented citizens across the southern African region has long been a feature of political commentary and politician discourse. Apart from South Africa, in Lesotho, Botswana, and Zimbabwe, the idea that opposition parties might harness those disconnected from the system has a certain appeal. These analyses, however, all assume that these individuals and groups feel like the political system can fundamentally reform to meet their needs. What if, however, the disaffection has spread so widely that youth and marginalized adults are reaching a tipping point, where people are going to demand not merely inclusion into previously exclusionary political systems, but rather a fundamental reorientation of political and economic systems they view as corrupt for having shut them out entirely for so long? Could we be seeing the start of a “new Southern Africa 1968” where protests by youth and the disaffected have a chance of fundamentally altering, or at least shaking the foundations of current systems?

False hope in oppositions?

While some South Africans put forth Maimane (and other now-departed, black, younger leaders in the DA such as Lindiwe Mazibuko) as the youthful, black faces of the future who could lead the DA from being a thinly disguised rump of the old National Party into a national force, it was never clear that the party had fundamentally changed. That is, many viewed it as still being in the hands of a white economic elite living off apartheid-era-based financial privilege. Maimane, in his exit speech, hinted that the party had never truly transformed to the point where it could reasonably represent South Africa���s poor majority, saying that it was clear ���the DA is not the vehicle best suited to take forward the vision of building One South Africa for All.���

Similarly, across the border in Lesotho, the roles of the ruling party and opposition have been rapidly shifting back and forth since the advent of the coalition era of Lesotho politics in 2012. Rather than thinking in terms of ruling/opposition, it is perhaps better to think of them as those in power versus those seeking power since policy differences between the parties are not very substantial. In any case, none of the parties that have been deemed the opposition over the past seven years have adequately represented the majority of the citizens in Lesotho who lack access to the political system and who are struggling economically.

In Botswana, long lauded as an exemplar of functional African democracy, the opposition Umbrella for Democratic Change, led by 50-year old Duma Boko, fell far short in its efforts to unseat the ruling Botswana Democratic Party. Its main strength prior to the election was the media attention given to its endorsement by former present Ian Khama, rather than any strong evidence of mobilization among Botswana���s disaffected. Thus, the opposition here, much like in Lesotho, was based around personality grievances among a ruling class rather than on significant policy differences that had a chance of addressing the unmet needs of the poor.

The destructive stasis of opposition

It seems reasonable to conclude that regional politics in Southern Africa are not in a state of flux, but rather at a point of destructive stasis. Rather than looking to opposition parties for change, many people are expressing their frustrations with the inequality and lack of political access through street protest, strikes, and other out-of-the-system protest actions. Will these lead to accommodation from the systems, or are we reaching a tipping point whereby systems break if they do not address the concerns of the historically-disenfranchised majority?

In South Africa, the ANC continues to be the ruling party, but its faction fights and the recent drop in the numbers of people voting suggests a large degree of alienation from the political process. In Lesotho, similarly, electoral participation has also fallen since the 1993 return of multi-party democracy. Zimbabwe has seen an increasing number of street protests against the government of Emmerson Mnangagwa. Lesotho teachers, who walked out of their classrooms in February over pay grievances, are back again on strike because the government failed to address their issues. There is currently no resolution in sight. Massive protests have also rocked the National University in Lesotho early this term after the government failed to distribute bursaries on time, and the university shut down for weeks. Protests regularly break out in South African communities large and small over the failure of government to provide services. In all of these cases, protestors are notably not appealing to opposition parties or asking for inclusion into political systems but are calling simply for their grievances to be addressed.

At best, opposition politicians, themselves, seem to be merely tinkering at the margins of the problems. The DA has reverted to the leadership of John Steenhuisen and Helen Zille. This is the same Zille who was roundly roasted for describing colonialism as ���not all bad��� multiple times on social media���a stance that signals her and the party���s inability to connect with the majority of South Africans. Perhaps change from within the system could come from the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), under the leadership of Julius Malema. However, many worry that the EFF simply represents a disgruntled faction that broke politically with the ANC, but displays similar autocratic and kleptocratic tendencies, as evidenced by the VBS Mutual Bank scandal. In Lesotho, Parliament is at a stand-still and the political reform process that was supposed to be completed by May of 2019 remains incomplete (though still taking public money). Botswana opposition parties not only can���t win an election, but they also fail to represent those who are disenfranchised either! The opposition in Zimbabwe at least talks about the disenfranchised and poor, but in an autocratic system it is not clear that their tactics have any ability to penetrate a system of massive state failure. Where is the hope for those wanting change within the system? It is certainly not visible to many in the opposition party platforms and actions in South Africa, Lesotho, Botswana, or Zimbabwe.

Opposition malaise and new protest forms?

Although the politics of opposition seem to be out of alignment with the increasingly sour mood of the majority in a number of Southern African countries, is this really any worse than what the rest of the world is facing at the moment? Politics in many places seem to be in disarray���from the abject anarchy of the Brexit process/general election in the UK to the muddle that is the ongoing impeachment inquiry in the United States, and then, of course, the massive street protests playing out in places as disparate as Hong Kong, Iraq, Lebanon, Spain, Bolivia, and Chile, among others.

Perhaps what we are seeing is the beginning of another age of global protest, led by youth and those feeling disaffected by political systems the world over. Are we at a new 1968? It is, perhaps, too soon to tell, but what is going on in Southern Africa is at once part of that trend of global protest, and something more than these other direct actions. For one, the structural problems in Southern Africa are significantly worse than the rest of the world. Southern Africa is home to six of the top nine most unequal countries (South Africa, Botswana and Lesotho) in the world according to the GINI coefficient calculations. This, of course, is a lingering legacy of the history and long reach of racial capitalism in South Africa and other regional settler colonial states. It is also, however, a trend that has been perpetuated and accentuated by contemporary politicians. These trends have coalesced in a large generation of disaffected adults and youth who have lost any hope that they will be able to access the political process, economic prosperity, or the social standing that comes with full membership in society. Amplified by social media and wider access to informal networks of solidarity that mobile apps allow, the disparate disconnectedness of marginalized groups in all of these countries could lead to national or even a region-wide movement. Although internet usage rates remain low in the SADC region, it is easy to both see how this will expand rapidly in the coming years, and how it could play out in terms of organizing and mobilization.

So far Botswana, South Africa, and Lesotho have not yet seen mass movements like national stay-aways or strikes to force systematic change. Zimbabwe has. Is this the future for the rest of the region? Another factor that could play into increasing protests is the continued collapse of the informal social safety net precipitated by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Many of the striking students at the National University of Lesotho (NUL) are not simply “entitled kids,” but heads-of-household with no other means of support because so many of their parents passed away prematurely from AIDS. The social safety net that many have relied on in recent years���grandparents���are also passing away, as Ellen Block has detailed in her book. With the ongoing demise of this informal safety net, there will be even more vulnerable youth and young adults. What the impact of this will be on protest movements is, as of yet, unknown, but when something like government bursaries are delayed (as was the case at NUL), this meant that many students were unable to eat. The urgency felt by those asked to study on empty bellies trumped the desire of the political system and institution to silence them.

At the moment, the politics of stasis, the politics of moderate reform, and opposition parties in Southern Africa all represent the politics of failure. Appointing yet another commission to study the problem of poverty or including the same few political leaders in yet another reforms dialogue does not address root problems that leave the majorities in most Southern African countries outside the political and economic systems.

Time will tell, but current political dispositions that attempt merely to engage those already in the political process are running even more risk that the tinderbox of poverty, inequality, and disenfranchisement will soon break out into the flames of more radical protest. Is the current regional political leadership listening?

November 3, 2019

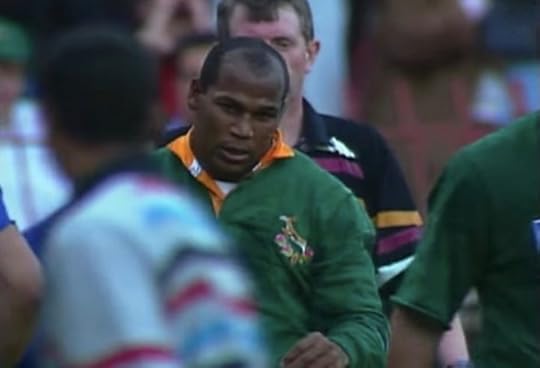

Why, despite it all, I���m still a fan of the Springboks

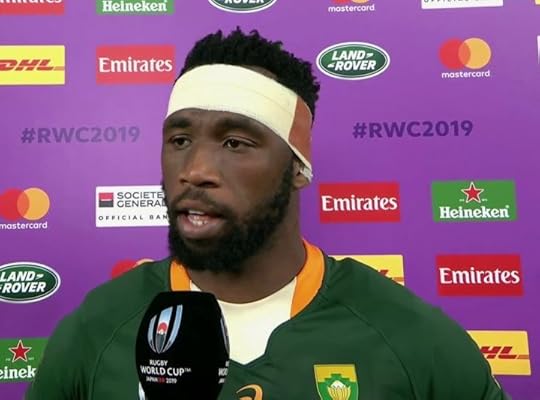

Youtube screenshot of post match interview by Springbok captain, Siya Kolisi.

The Springboks are world champions again after their 32-12 pummeling of England in the final of the Rugby World Cup in Japan. Team captain Siya Kolisi���s post game interview has gone viral, capturing the ideals of the Rainbow Nation; an ideal that has been discredited more recently. Kolisi reminded the world of South Africa���s race and class divides: ���I never dreamed of a day like this at all. When I was a kid all I was thinking about was getting my next meal.��� He later added:

That���s what we wanted to do today and we really appreciate all the support, people in the taverns, people in the shebeens, people in farms and homeless people that had screens and people in rural areas. Thank you so much, we appreciate all the support. We love you South Africa and we can achieve anything if we work together as one.

Similarly, Springbok head coach Rassie Erasmus has been praised for having said all the right things in his post-match press conference. The videos of the most interracial team in Bok history have spread far and wide. Even the most cynical journalists are talking and writing about harmony and hope and inspiration and that most South African of words, ���transformation.��� (Large sections of South Africa���s rugby press are cynical about changing the game���s white face on and off the field.)

By the time the Springbok party lands at O.R. Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg, the victory, Kolisi���s inspirational words, Erasmus��� acknowledgment of things beyond rugby, the clips of black and white players dancing���these will all be commodified and commercialized, neoliberalism being the true force beyond rugby. The 2019 Springboks will be used to sell beer and mobile phones, satellite TV, and sports drinks. Above all, they will be used to sell ���Transformation ���.��� Lock Eben Etzebeth���s missteps (he is accused of racially abusing a coloured man back in Langebaan, South Africa), the mysteries of potential exclusion of black players surrounding the ���Bomb Squad��� (when an exclusive group of white Springboks celebrated separately on the field), and the realities of South African lives in Kolisi���s hometown of Zwide in the Eastern Cape province���these will be swept away, out of view, at least for now, as those with the best of intentions but dubious perspective insist that the 2019 Springboks have changed things, have had an impact, have shown what South Africans can only do if they all just come together as one. It will be the 1995 Springboks 2.0. ���Siya���s Spell meets Madiba Magic.���

And let me be clear, I too am riding the wave of euphoria. For all of Springbok Rugby���s problems, both historically and today, I was supporting this team. I have been swept up in the emotions.

Being a sports fan is always problematic. There is no moral or ethical perfection. You support the All Blacks because you supported them against South Africa during apartheid? That���s great. But you could only support them because they continued to play South Africa, offering a rare port in a storm buttressing apartheid rugby when teams like Australia had chosen disengagement. New Zealand���s South African support always had a whiff of sanctimony to it given that for the vast majority of All Black interactions with Springbok rugby prior to 1992, New Zealand was willing to sell out its own Maori players by not allowing them to tour to South Africa to play the Green and Gold until 1970 (when visiting Maori players were granted the dubious ���Honorary Whites��� status). There is little doubt that All Blacks supporters in South Africa developed their loyalties out of a deep sense of principle. But that principle nonetheless comes with a healthy dose of opportunism. Look into the history of the great New Zealand fullback George Nepia and ask yourself why he never did play against the Springboks. Then think again about principles, but also about opportunism. Even principles can be problematic in the context of elite sport.

If you support an elite sports team the odds are that whether you know it or not you support perpetrators of domestic violence or racists, you support homophobes or Make America Great Again chuckleheads, you support young men and women, some of whom you would not like if you met them and many of whom would look down on you with barely shielded scorn and condescension if they met you. And let us not think about the reprobates and troglodytes who populate every fan base on earth. It is a clich��, but if you support big-time sport and have chosen a side, you cheer for laundry. That laundry might be washed not far from where you live. It might get dried by people who speak your language or refer to your grilling of meat as a ���braai��� rather than a barbecue. It might get sponsored by Castle instead of Budweiser, MTN instead of T-Mobile. It may be the color you once wore or that your dad or mum once wore. But it���s laundry. And as professional athletes show by rightfully exercising their agency whenever possible, that laundry is interchangeable.

And yet the laundry I was supporting on Saturday was green and gold. To me it was the laundry of Beast Mtamawira and Cheslin Kolbe, of Makazole Mapimpi and Lukhanyo Am, of Bongi Mbonambi and of course of the inspirational captain, Siyamthanda Kolisi, a man who, if all of the Rainbow Nation palaver even vaguely lives up to he country���s hopes and ideals and rhetoric, will earn a place more esteemed in the annals of South African sport then 1995 Springbok captain Francois Pienaar.

South African rugby is imperfect and has an appalling history. If they abandon the Springbok logo I will shed no tears and gnash no teeth. As fans we inherit the histories of the teams we support. I loathe the long history of the Springboks even as I support the current if flawed iteration. I wanted Eben Etzebeth to make crushing tackles and to earn hard meters and to play the role of enforcer because that was good for the Springboks, even if I cannot stomach what may have happened in Langebaan just a few weeks ago.

I arrived in South Africa in 1997 knowing shockingly little about rugby, and left a supporter of the only team that made sense to support, not as a historian of race and politics, where the Springboks continually fell short, but that made complete sense in the context of someone who played his first rugby match in the country, whose friends, black and white, were supporters of the Boks, and of their own local teams, and who allowed himself to get caught up in the heat of the still-glowing post-1995 embers. I supported Chester Williams but also Joost and Os, James Small, Percy Montgomery, and Mark Andrews.