Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 202

October 3, 2019

The Cuban Atlantic

Bakos�� dancing. Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

British sociologist Paul Gilroy suggested the history of culture in the Atlantic world is characterized by constant exchange. One of the most traceable elements of that exchange, is the musical connections between communities of African descent on either side of the ocean. These musical practices operate as sites of resistance, cultural retention, and social cohesion that allow us to understand some of the ways we all are formed by trans-continental processes.

During the dawn of recorded music in the early part of the 20th century, Cuba���one of many New World sites of African and indigenous resistance to European colonization and enslavement���would become a hotbed for musical export in the emerging industrialized system of music distribution. Folk musical traditions from across the island would come together in Havana���s studios, and then get dispersed around the entire Atlantic world. In the early part of the 20th Century, Cuban musical styles like son, mambo and guaguanco followed migrants and sailors out across the Atlantic, hitting radio waves in the ports of landing, and spreading throughout the interior of the countries they landed in.

With its strong traces of West and Central African rhythms, this music would find legions of devoted followers on the African continent. Local artists would try their hand at recreating the sound, and start to mix elements of their own local traditions creating what we now know as rumba, soukous, mbalax, semba, kizomba, and highlife, etc. These styles, amongst many others on the continent, would go on to form the backbone of national identity in the post-independence period, their propagation supported with enthusiasm by leaders of the new nations. They are also the ancestors of many popular music sounds on the continent today.

Kiki on Conga. Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

Kiki on Conga. Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.While Cuba had technically been independent for at least a half century before sub-Saharan African nations, one could argue that Cubans found their true independence in conjunction with their peers on the continent. The Cuban Revolution in 1959 shook off the final shackles of American empire and posed a challenge to the hemispheric dominance of US imperial capitalism. Cuba would go on to become the western hemisphere antithesis to everything its larger and more powerful neighbor to the north stood for.

After the Cuban Revolution, Cuban people and cultural production would become cut off from capitalist networks of trade, though it would retain some influence in the Caribbean and South America despite US attempts to prevent it. In Africa, countries like Angola would strengthen their ties with Cuba during the Cold War, but the outsize cultural influence that Cuba held in the Atlantic world, pre-revolution, would leave a void that would quickly be filled by Jamaica, Brazil, and the Cuban and Puerto Rican diasporas in the US. Cuba itself would turn more inward, its cultural production burdened by the heavy weight of nostalgia and nation building���European, indigenous, and African roots fighting it out in a perennial dance on top of the ruins of the Spanish empire.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.The beauty in black Atlantic cultural formation is in the continual exchange of information that persists between peoples of African descent across language, national borders, and even time. This “counter-culture” of western modernity utilizes and navigates systems that were designed to exploit and repress the communities from which it comes. So naturally, on the back of western capitalism, African popular music influenced by Cuba would repeat the process initiated in the early 20th Century, finding receptive audiences back on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean. In places like Santo Domingo, Port au Prince, Cartagena and Baranquilla, the process of acculturation and hybridization would repeat, and Africa would have its turn to make its mark on the popular musics of the Caribbean in the latter part of the 20th Century.

It would take until more recently, in the wake of a political and cultural youth revolutions on the African continent, and a global revolution in communication technology, for similar processes to happen in Cuba. And that���s where Puerto Rican brothers Eli and Khalil Jacobs-Fantauzzi���s latest documentary Bakos��: Afrobeats in Cuba picks up.

The opening scene in the film shows Havana-based DJ Jig��e tuning into a radio interview with an artist named Ozkaro to hear that ���something��� is happening 700 km away in his home province of Santiago. A new musical genre, bakos��, was developing, and local artists such as Ozkaro, were blending Afro-Cuban folk and popular music with contemporary continental genres such as afrobeats, afro-house, and kuduro. There are huge parties with hundreds, maybe thousands of fans in a public square, new dance styles and crews, and the city���s set of rappers and reggaetoneros are enthusiastically taking to the genre.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.Jig��e decides that he needs to go back home after being disconnected and see what is going on in Santiago. This personal journey home, to a place of roots, serves as a metaphor in the film itself, for bakos�����s origin story and for Cuban���s engagement with African culture in general. This, along with other devices employed by the directors, such as the folkloric dance performance that bookends the film, create a form-defying, yet accessible introduction to Cuba���s cultural landscape.

Once in Santiago, we travel with Jig��e to meet Ozkaro in his home studio where they discuss the difficulties in being an artist in Santiago: the lack of technology with which to produce, and the challenge of being distant (or rather disconnected) from the capital of Havana where the largest media houses are. Such hurdles are taken for granted in the global North. In the formation of the current mainstream global pop sound, access to technologies are necessary prerequisites. Even with this disconnection, Cubans have no problem accessing sounds from the continent. That’s because contemporary African genres arrived in Cuba from a surprising source: medical students from Angola, Mozambique, Tanzania, South Africa, and across the African continent.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.In the film, some bakos�� producers offer explanations as to why they think the African students��� music has been taken up with enthusiasm by the public in Santiago. Reasons dance around the idea of African retentions, sometimes slipping into essentialist tropes common across Latin America like ���Santiageras have a certain sexuality.��� But, it���s Ozkaro who provides one of the most profound insights when he explains the importance of the clave to the Cuban public. This insight is interesting because it is an electronically programmed clave rhythm that has become the most pronounced element across many African popular music genres, and was one of the main rhythms that African audiences had originally connected with when Cuban music reached their shores.

The film moves on from there to explore more of the African retentions embedded in Santiagero culture, and explains the conditions that birthed a strong African consciousness in this part of the island. In a scene where the group Conexi��n Africa is recording a song called ���Africa��� with an Angolan soccer club���s banner on the wall of the booth, one can tangibly feel African consciousness in Santiago manifesting.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.While this celebration of Africa in Cuba is inspirational, the film is a bit overburdened by the weight given to the personal allegory of a return to African roots (and subsequent journey out to share them with the world). Beyond just a connection to roots, it must be understood that the birth of this new musical genre was assisted by Cuba���s state foreign policy of building global South solidarity, and aiding the African liberation movements. The film lightly touches on this. For example, Jig��e mentions the history of Cuban military support for Angola, and how this action is thought upon fondly by many of the Angolan students who arrive to Cuba. The film, however, would have benefited from more of this political context to balance out Jig��e���s romanticism.

One section, if expanded on, would have gone a long way to rectify this issue, and that was the story of how a nationwide Africa Day celebration came to be in Cuba. Nayda Gordon, the founder of a youth African dance troupe, Sangre Nueva, explains how years ago African students would only practice their cultures with each other in parties and celebrations behind the closed doors of the medical schools. The cultures of these students piqued her interest, so she reached out to a medical student named Demba and together they organized to form the troupe. A former African medical student, Dr. Ibrahim Keita, mentions Demba and a committee that was formed ten years ago with the aim of integrating African students more with the local community. Keita alludes to the fact that this committee helped bring about the Africa Day festivities and claims, ���if Kuduro is being accepted by Cuban youth today, it���s because that was our intention.���

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.Gordon���s personal motivation to connect with strangers is fascinating. It would be interesting to contextualize her initiative in relation to Cuban social norms and find out why it was important for her to connect Cuban youth with African culture. And, the modes available for building programs of integration through grassroots solidarity in Cuba are unfamiliar to me. In the film, this section passes very quickly. It left me wondering: What was the committee? Who all was involved? And, how did they managed to gain state support? An international audience especially would have benefited from further exploration of these questions.

Jig��e mentions over and over that this or that could happen ���only in Santiago.��� This perhaps works best in a local context amidst a continued struggle with racial inequality on the island, but not so much outside of Cuba. Because, rather than exceptional, the formation of a genre like bakos��, and the conditions that allowed it, is a process that I have personally seen repeated over and over across the Atlantic world (admittedly thanks to a little passport privilege and a fast internet connection). Kuduro, afrobeats, and afrohouse themselves are a result of such processes, and this is not the first time director��Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi has been there for such moments either. He previously documented the growth of hip hop in Cuba with his film Inventos: Hip Hop Cubano and the rise of hiplife in Ghana in Homegrown: Hiplife in Ghana.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.

Image credit Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi.What is exceptional about Santiago that makes it stand out amongst its hemispheric neighbors are the political and social conditions that allowed this exchange to happen. In contrast to North America���where corporate streaming platforms and an ���Africans! They���re just like us��� narrative are propelling Afropop into the mainstream���in Cuba a state policy of global South solidarity, has merged with an African consciousness embedded amongst the people to open pathways for integration between Cubans and their African immigrant neighbors.

Paradoxically, at a time when much of us are hyper-connected, Cubans were able to connect with Africa in the face of digital disconnection. So, bakos�� remains as a unique cultural space in a world where cultural difference seems to be melting away. Bakos����is wonderful, simply because it is still a story of a specific place, and a sound for a specific people, at a specific moment in time.

What may be most exciting about both��the film and the music itself is in their allowing us to romanticize the potentials and possibilities symbolized by the inadvertent transfer of music. Bakos�� is a gift to Cuba from the African nations that were touched by Cuba���s influence, being sent back to the island that helped define what it means to be African in the modern world. With beautiful cinematography, and an innovative take on the documentary genre, the Jacobs-Fantauzzi brothers have done a great job in documenting this exchange on another leg of its journey.

The place of race in Cuba

Santiago, Cuba. Image credit Fernando via Flickr CC.

Race is possibly the most difficult and least understood issue in contemporary Cuba. Many Cubans don���t even want to hear it brought up in conversation. And when it is, reactions are still unpredictable, covering a wide range of attitudes that go from negation and cynicism to denial and disinterest.

Racism has historically been seen as a decisive topic, so there is very little effort to address it on a societal level. Sure, there are racially conscious black and mestizo Cubans, but they have had to wait too long for any kind of public debate on the subject. This is a flagrant contradiction and great dysfunction in a society that claims to be extraordinarily humanist, and whose people have fought for social justice and equality, reaching the borders of egalitarianism.

There is still a wide range of opinions on racism in Cuba, including denying that it even exists. And although there is still some ignorance, a false belief that the topic would effect our national unity. There is a persistent tendency to launch the accusation of ���racist��� to anyone who brings the idea of race to the surface. (In March of 1959, Fidel Castro put forth the need to address the issue of racial discrimination in Cuba, but there were those believed that this was an issue that had already been resolved. It is not surprising that such attitudes persist today.)

Unfortunately, after many years of silence on the subject, it has come to be a taboo, and today our country is significantly behind other countries when it comes to this question, whether among intellectuals or in cultural, scientific and political spheres. Race is not even mentioned in most contemporary analyses of the social and cultural reality of the Cuban nation. This is reflected, without a doubt, within our intellectual tradition, by the fact that there are many different views on where we are even at in terms of our development in the national project.

We have to stop accepting that everyone who calls themselves Cuban today received the same opportunity to contribute in the building of our nation. In order to have a more realistic attitude about the different racial groups, social inequalities, and the reality of race in Cuba today, it is essential to keep in mind the diverse contributions of different groups at distinct points in Cuban history. The truth is, some of us came as colonizers (whites) and others as slaves.

In Cuba, public debate is still discrete, incomplete, and unpublished. The work that is needed to address the root of racism still existing.�� Inequalities continue to have a global component, even, when they are focused on our most vulnerable communities. Regardless, the variable ���race or color of skin,��� even with the existence of a policy of ���affirmative action��� in Cuba, continues to be a subliminal facet of public life, or at least people don���t admit when they are considering it. (Without a doubt, in 2005 after an increase in pensions, the minimum wages, and the distribution of subsidized basic needs���a humanistic political act���benefited blacks and mestizos because these groups were classed more proportionally amongst the country���s poor.)

Our Cuban society is, without a doubt, a ���multiracial��� society, or better said ���multi-colored.��� We should not only treat it as an issue of numeric representation, of whites, blacks and mestizos in different positions, but also to put an end to stereotyping and have it reflect it in the equality of conditions. Above all, the question of the distribution of power appears as an important one, because not all racial groups can assert themselves in order to reach the equilibrium of a truly multiracial (multicolored) society.

As the very wise founding father of Cuba, Don Fernando Ortiz, said, Cuba is an ���Ajiaco��� (a type of stew). An idea that we clearly share, only that I would modestly shift it to say that the ���stew is still cooking.��� We still have people who not feel like they are inside of the pot, and there are those who would even like to get out of it, or at least to diminish the intensity of the flame. On the other hand, inside of the pot we have more meat and vegetables than we had even imagined, from before the economic crisis of the nineties, that still haven’t softened. To paraphrase Issac Barreal, ������we shouldn���t only calibrate the stew by the expected result, but also during the process of cooking.��� It is a reality on which not all of us are in agreement, but this is of vital importance for the process of consolidation of the national unit, as well as for our political alliances with the rest of the colonized peoples (indigenous, and Afro-descended) of the world, and in particular with those of our continent.

It is at this crossroads that we the Cuban people find ourselves at today, although, many of us do not understand or are ready to take concrete action in every way so that the stew can finish simmering. If we don���t do it, we will lose the last opportunity to finish constructing the society in which the large majority of Cubans really hope to live. At the same time, it will effect our alliance with 150 million Afro descendants and the indigenous populations of our continent, who look to Cuba not only as a paradigm for political emancipation, but also social emancipation. It is not possible to share with these groups the ideas that ���a better world is possible��� and continue bypassing the ���challenges of color��� internally.

Culture and education are, in our opinion, the first options of defense for the armies of this battle. Because it has already been more than proven that although racism has comfortably situated itself inside of capitalism, to getting rid of that regime is not enough to get rid of racial discrimination, and above all the prejudices and stereotypes that feed it. So, paraphrasing Antonio Gramsci, one has to do away with simplistic ���popular culture��� and the innocuous ���common sense��� of the public; one must clear the battlefield for the formation of the true revolutionary culture. But the bourgeois ideology is so strong that it has had the ability to make many of us believe, that all those bad habits of racism and discrimination, are the most natural thing in the world.

I have a friend that said to me one day, ���why do you think black people need to be on television more? You already have a station for yourselves: the sports channel.��� Repeating that joke here, even though I don���t want to, shows the cynicism with which not a few Cubans approach the situation. Only an open debate, from the perspective of culture and science, could do away with that luck of hypocrisy, inherited from Spain, for which there is no place in the culture of the truly integrated and revolutionary society that we want to build.

We have ample examples in film, literary, dance, music, history, integrated culture that in general vindicate the African presence in the formation and development of our national culture, but not much of that laudable labor directly addresses our actual reality, where there is still the presence of negative stereotypes about non-whites, prejudices, racial discrimination and racism.

The three most ample investigations of the last 40 years (this, this and this)�� around the issue of race in Cuba, were not produced in this country, nor by intellectuals that live on the island. Inside Cuba, very little has been published that treat the issue as a contemporary problem.

We have a written history, in which blacks and mestizos are still insufficiently represented inside the processes of the formation of our nation and its culture. This sincerely still effects our national identity. We have to finalize the introduction of ethnic-racial studies at all levels. They have to be constantly present and built into our education and our media systematically, above all on television.

We must educate ourselves to become Cuban, not to become white, like sometimes happens. We must assume the challenges, although also the spoils, from introducing color-consciousness into the formation of our children and young people.

Our education system cannot be qualified as racist, because all Cubans are able to access it equally, although limitations persist. Nevertheless, not all the foundational roots of our nation and its culture share equally in the opportunities for and programs of study. While we do not exclude blacks and mestizos in our educational system, lately, in daily practice, they are excluded as being part of the lesson in the classroom. What doesn���t enter into one���s education, doesn���t pass into the culture, and if our education is weak, or even absent in regards to questions of ���color,��� racism and discrimination, and the problems that come with, will never be solved.

The circumstances relative to the formation of a multiracial or multicolor identity have to finish taking their place in the Cuban education system. It is a problem that effects us all, and effects the identity of the nation as a whole. As long as it is not there, we will not be really be educating people to become Cuban in a holistic manner.

Regardless, in the last 20 years, we have advanced a lot. We are working hard to introduce new content into our school curriculum, and a new form of teaching national history; we start to explain the problem of color in school; Africa, Asia and the Middle East have started to find their place, not only in the cultural but also in the social and the educational realms. In community projects, study groups, and the press, a debate has been taken up with great enthusiasm, and has forced its way into academic and cultural institutions���albeit much more slowly in research at the university level, and in science in general. The Aponte Commission of the Union of Writers and Artists in Cuba (UNEAC) has begun to make their presence on the matter felt, in their strong ties with the national government and the state. They are advancing the need to recognize and constitute an institutionally that allows the issue of race to be recognized as a necessary issue for the national stage, with a governmental resolution that recognizes the need to consider race at the national level���as much from the point of view of the educational system as in culture, politics, and government. The National Assembly has adopted a structure with a greater representation of blacks, mestizos and women at a national level. So, blacks and mestizos today are present in political and governmental structures at rates proportional to the greater society.

Former president, Raul Castro, in the National Assembly, strongly pushed the issue of black, mestizo and female representation in our parliament���achieving in it a racial composition like has never before existed. At the level of the political organization, as much nationally as provincially, and all the levels of government, one can see the presence of black and mestizo people like has never been seen before in the country. So, things have advanced considerably, and the political will exists to keep doing so. We have started a period in which the determination to advance strongly towards a consolidation of the social project that is the Cuban Revolution, eradicating a problem that threatens us. Because, racial prejudices, discrimination, and racism are totally incompatible with the Cuban socialist project.

October 1, 2019

No country for poor men

Rwanda. Image credit lksriv via Flickr CC.

Had I been running with my headphones on, I wouldn���t have paid much attention to the lone machine gun-toting guard, pacing on the sidewalk outside the sparkling spiraling glass dome that is the Kigali Convention Center. But out-of-shape, winded, and without anything to listen to, I heard the guard���s firm order to cross the street. Confused, I obliged. There didn���t seem to be a conference happening. Why the tight security?

Yet, the entire road outside the Convention Centre���a convenient thoroughfare connecting large sections of the city���remained closed for the entire length of my stay in the Rwandan capital, and traffic flowed around the obstacle knowingly.

Showy yet vacant, the Kigali Convention Centre, much like Rwanda���s development record, stands guarded like a badly kept secret. And, despite the immense focus on sustainable development in this year���s United Nations General Assembly���the 74th in the body���s history and the 25th since the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsis���the controversy went entirely unmentioned.

Scholars and journalists alike have shared their concerns about the growing authoritarian and repressive qualities of the Rwandan government under the Rwandan Patriotic Army���s former general and the country���s current president Paul Kagame���and which I echoed previously on this site. However, until more recently these concerns went largely ignored by an international community perfectly satisfied by the incredible economic progress being made. That is, the progress that was being reported.

Relying on the substantial investigative work��originally published by The Review of African Political Economy (Roape)���and as an extension of the debate initiated in 2015 by Filip Reyntjens, lawyer and professor at the University of Antwerp���the Financial Times, as well as the Economist, recently published articles detailing the apparent manipulation of the country���s poverty statistics from within. In the last 20 years, the Rwandan government, specifically the National Institute of Statistics Rwanda, has collected data on various rates of consumption for their Integrated Household Living Conditions Surveys (EICVs). Citing the results of the fourth such survey, from data collected between October 2013 and October 2014, the Rwandan government claimed a reduction in overall poverty from 45% in 2010/11 to 39%. Anywhere in the world, a fall of such magnitude would be nothing short of miraculous. Skeptics were swift in pointing out, however, that certain survey criteria had changed.

Long-held in high esteem by NGOs and Western donors for its rapid economic growth, and frequently compared to the likes of Singapore, Rwanda may not actually be making the strides reflected in the fourth Integrated Household Living Conditions Surveys (EICV4). Economists, like Sam Desiere of the University of Lueven, noticed that the new data had been collected using an altered food basket (the term given in economics to the total amount of goods purchased and consumed on a daily basis by one individual in order to meet basic dietary needs) in which more expensive, low calorie products were replaced with cheaper, high calorie ones. It also used rates of inflation (for food goods) much lower than reasonable estimates suggested. In other words, the National Institute of Statistics Rwanda changed the poverty line, making it easier to categorize more people as having risen out of poverty.

When the poverty line is readjusted using the food basket scheme from previous EICVs, along with more accurate inflation rates (which can be done using Rwanda���s own data), rather than showing a 6% decrease in poverty the data suggests as much as a 6% increase in poverty. As Roape reported, if the new trend is sound there is only one country in the world which experienced a more precipitous increase in poverty than Rwanda: South Sudan. To say the drop from a comparison with Singapore to one with South Sudan represents a fall from grace would be an understatement.

But how much blame does Rwanda, or even President Kagame, who explicitly denied the allegations made by the Financial Times, deserve? What evidence is there that shows that Rwanda���s rose-colored data was intentionally manipulated? What sign is there of wrong-doing��besides repeated denial in the face of empirical evidence? And, how might we assess the alleged complicity of the World Bank, which expanded its financial commitment to the Maryland-sized East African nation��from $201 million in 2017 to $545 million in 2018 (more than 270%), well after the first reports of false statistics were published?

���This conversation [about Rwanda���s poverty statistics] has been happening for a while now and it needs to be placed in a broader context,��� said Dr. Pritish Behuria, Hallsworth Research Fellow at the University of Manchester. It is ���tough to say the World Bank is complicit,��� he continued, “many countries are guilty of manipulating their own poverty statistics,” a point with which Reyntjens agrees.

The debate on poverty statistics aside, Rwanda���s economy has not been without significant positive change since the genocidal war of 1994. As Behuria points out, Rwanda���s dependence on unprocessed coffee before 1994 (the fluctuation of market prices were historically accompanied by dramatic changes in power) has been slightly padded out by increased processing, as well as Rwanda���s transition to mineral dependence. Though, being a small, land-locked country, it has also been able to implement��a plan to increase domestic manufacturing of locally consumed goods, such as clothing.

Surely stability counts for something. After all, as Rwanda���s Minister of Finance and Economic Planning, Uzziel Ndagijimana, offered in his rebuttal of the Financial Times report: The only reason this entire debate around poverty statistics is taking place is because Rwanda has had the capability of collecting data and has disseminated it transparently.

Despite the Rwandan government���s position, Behuria still has some reservations: ���Perhaps [there is] pressure within the system to manipulate data… whether it is being strategically manipulated? I think that���s a bit far. Maybe they do turn a blind eye to some of the more… heavy handed policies.���

Other scholars, like Reyntjens, who has spent the past 20 years writing critically of the Rwandan government���s human rights abuses (earning a ban from entering the country), are less convinced of various actors��� innocence. In his 2015 article on African Arguments, Reyntjens noted that the Oxford Policy Management team, which had collaborated with the National Institute of Statistics Rwanda for their 2011 survey (for which they were strongly acknowledged in the survey���s publication), abandoned their work with the agency over a difference of view. Reyntjens argues: ���The question then becomes whether the Rwandan government deliberately fools the world and its own population. There are strong indications this is indeed the case.���

While this is far from the proof necessary to make a judgment of the Rwandan government���s guilt, in the larger context of the regime���s increasingly authoritarian, repressive, and violent tendencies, this assessment does not stretch the imagination. Significantly, it was the Integrated Household Living Conditions Survey 4���with its food basket criteria that reduced certain more expensive, but nonetheless common, food staples by as much as or more than 70%���that immediately preceded the passing of the 2015 constitutional referendum. This referendum allowed President Kagame to not only stand for a previously legally impossible third term, but to also potentially extend his rule to 2034.

Reyntjens explains:

The international community has been very understanding, so to speak, of the Rwanda regime. They have tolerated major human rights abuses, authoritarianism, the destruction of a political level playing field… in exchange for an economic and social success involving poverty reduction… if those [poverty statistics] are not reliable, then surely there���s a problem with the trade off.

Though the 74th UN General Assembly and its accompanying Sustainable Development Summit have come and gone, it is worth questioning the role that large international financial and governmental institutions play in creating the conditions that at best allow, and at worst facilitate, the development of authoritarian repressive regimes���especially those that disguise the continued impoverishment of their own populations. Though, as Reyntjens says, ���It���s not just the UN, it���s also the donors. They simply don���t want to rock the boat… Donors and recipients need each other. The recipients need the money, and the donors need success stories.��� For this reason���or the sake of preserving the facade that is Rwanda���s developmental success���it is unlikely that Rwanda���s statistics manipulation will ever be discussed at any of the numerous high-level meetings on the UN���s Sustainable Development Goals.

(Though I attempted to contact Rwanda���s UN delegation, as well as a number of other individuals working for the UN, it came as no surprise���after sifting my way through just a few articles and documents and enduring the wordy,��technocratic slurry��that is the UN���s website���that no one I was passed off to would respond to my simple questions: Does the UN use Rwanda���s statistics in their own assessments? Will they discuss data collection and statistics manipulation, perhaps as a “critical entry point” into the discussion of “megatrends impacting the implementation of the SDGs?” Though��one article��states that the ���UN development system is undergoing its ���deepest reform in decades��� to be able to respond to the paradigm shift at the heart of the 2030 Agenda,��� it is clear that this reform, like all reforms, is a mild and vague defensive maneuver designed to protect the solidly entrenched Washington Consensus���the boat they really don���t want to rock.)

Is all this hard focus on Rwanda by academics, economists, and journalists justified? After all, as Behuria acknowledged, many countries are guilty of the same form of statistics manipulation that has taken place in Rwanda���Reyntjens even points out President Trump���s own record of misrepresenting economic gains. So, is this much criticism heaped on a small African nation some form of afro-pessimistic bullying disguised as good intentions?

Perhaps. Though, as a member of this same group of critics, I can at least attest to the fact that I never personally chose Rwanda as the recipient of my criticism; a long history beginning with my Peace Corps service and the very personal relationships I made there led me to simply notice that things weren���t right. And that seems to be the case for many people involved in this work who level criticism and hope it makes an impact that will ripple outward. Illustrating this point, Reyntjens brought up a helpful, European example:

If the EU accepted Greece into the Eurozone knowing���probably knowing���that they doctored their figures, Greece was not at the same time massively arresting people, putting them in jail, torturing them and extrajudicially executing them; We tolerate certain things from Kigali that we should not tolerate, and we do it because they���re successful. And yet, the evidence base of their success is extremely flimsy.

So again, as the UN Sustainable Development Goals plod along forever in a circle like a donkey working a horse mill, it is worth asking: To what extent are the World Bank, Western donors, and the United Nations by virtue of its own silence, complicit not only in the continued impoverishment of the populations of developing countries, but in the human rights abuses, structural violence, and extrajudicial killings committed by the governments of those countries? If the developmental model so widely agreed upon, the Washington Consensus, not only forgives but grows and strengthens authoritarian regimes that cause violence and beget further violence down the road, then of what use is the model? Like a less demonic Anton Chigurh, we must ask: If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?

And, of course, the question always lingering in the background of such large, leftist, structural questions: who���s going to do something about it? If massive institutions, like the United Nations, are��primarily populated by the well-meaning sycophantic zombies of capital, then how can they be trusted to arrive at the precipice of the massive paradigmatic, psychological and political shift required to make any difference in the lives of most people in a real way���whether in Rwanda, the US, or anywhere?

September 30, 2019

Refuting that precolonial Africa lacked written traditions

A mill owner���s advertisement for grinding grains reads: ���Ku b��gg w��llu w��lla soqlu w��lla tigadege w��lla nooflaay; kaay fii la. Waa K��r Xaadimu Rasuul [If you want (your grains) pounded or grinded or peanut butter effortlessly; come here. The People of The Servant of the Prophet (Ahmadou Bamba)]���. Image credit Fallou Ngom, 2015.

Ajami, the centuries-old practice of writing other languages using the modified Arabic script, is deeply embedded in local histories and socio-cultural practices in West Africa. Grassroots Ajami literacy has been historically high in the communities and across countries in the region. While often viewed through the lens of its religious historical origins, it is increasingly evident that the use of Ajami scripts in a variety of African languages extends far beyond religious and educational contexts. African Ajami can be observed in a growing multiplicity of secular environments, including interpersonal communication, commercial advertising, street posters, billboards and road signs, political campaign ads, and the insignia of local businesses and services.

Arising from Islamic clerical and educational campaigns of the 15-16th centuries, Ajami constituted an early source of literacy for a variety of local languages in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Yoruba, Mande, Wolof, Fula, and Afrikaans. Its history refutes the oft-prevailing claims that Africa lacks written traditions. The downplaying and devaluing of the significance of African Ajami has long characterized both Arabic and European scholars and administrators of the colonial era, and its legacy still often persists, perpetuating racial stereotypes, limiting political participation, and obscuring ethnographic accounts of local practices and institutions.

We���re all three based at the Boston University African Studies Center and working on the research project ���Ajam�� Literature and the Expansion of Literacy and Islam: The Case of West Africa��� with a NEH Collaborative Research Grant. Collecting, digitizing and interpreting manuscripts in Ajami in four major West African languages���Hausa, Mandinka, Fula, and Wolof. The project provides a new window into the history, cultures, and intellectual traditions of West Africa.

Having flourished throughout centuries, Ajami has established itself as an important means of communication and a mediator of historical and contemporary knowledge in many areas of Africa where Qur���anic schools have been the primary source of education. Consider the example of Senegal. It is estimated that over 50% of the population of this “French-speaking country” are illiterate in French, and adequate skills in written and oral French largely remain the purview of urban elites. Many ethnic groups of the country, including Wolof, Pulaar, and Mandinka, use Ajami scripts for their written communication. Ajami Wolofal (the language of the Wolof ethnic group) is used both for religious and secular purposes in the local communities, including personal written communication such as private letters, as well as in business records and advertisements of the informal sector.

It is interesting to note that the role of Ajami as an effective tool to reach grassroots communities has not gone unnoticed by large multi-national corporations expanding their business in Africa, as well as by organizers of national and local political campaigns. The adverts of mobile telephony and mobile money services of large telecommunications companies such as Orange S.A. and Tigo of Millicom adorn huge billboards on highways and can be found painted on the walls and fences of modest neighborhood shops and kiosks. Our photos illustrate the Ajami ads of Orange and Tigo telecoms in the Diourbel area of Senegal where Ajami dominates French literacy. In Diourbel, a majority of important public announcements are first issued in Ajami, and then translated into French for wider national outreach. It is no surprise that companies such as Orange S.A., a French multinational telecommunications corporation, have understood the economic and social benefits of reaching their consumers in locally accessible and accepted ways.

Shopkeeper���s Ajami advertisement in Diourbel, Senegal, reads: ���Fii da��u fiy wecciku ay Qas�����id aki band(u) ak kayiti kaamil aki daa��� [Poems, audiocassettes, Quran-copying quality paper and ink are sold here].��� TIGO is a reference to a mobile phone company. Image credit Fallou Ngom, 2015.The growing use of Ajami in public life can be observed also in neighboring Nigeria.

Shopkeeper���s Ajami advertisement in Diourbel, Senegal, reads: ���Fii da��u fiy wecciku ay Qas�����id aki band(u) ak kayiti kaamil aki daa��� [Poems, audiocassettes, Quran-copying quality paper and ink are sold here].��� TIGO is a reference to a mobile phone company. Image credit Fallou Ngom, 2015.The growing use of Ajami in public life can be observed also in neighboring Nigeria.

During the 2019 Nigerian general elections, political posters using Ajami script were widespread among Nupe language speakers in the country, for instance. The Nupe ethnic group is situated in the Middle Belt and northern Nigeria and are widespread in Niger State as well as in Kwara and Kogi states. The origins of the ethnic group trace back to the 15th century when Nupe formed loose confederations of settlements along the Niger river. Converting to Islam in late 18th century, they retained many indigenous features of social organization and cosmology. Nupe have also historically maintained close contacts with their Yoruba and Fula neighbors, now all part of a large multi-ethnic state.

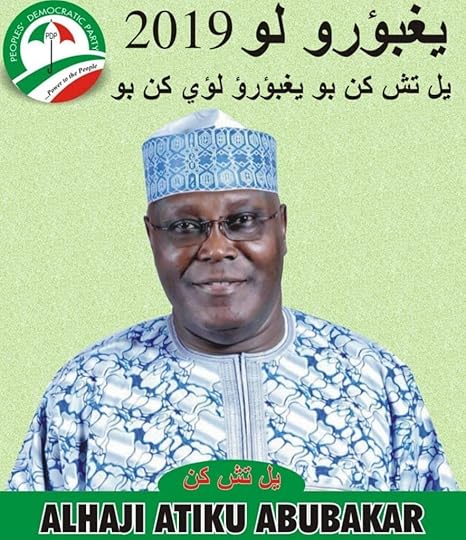

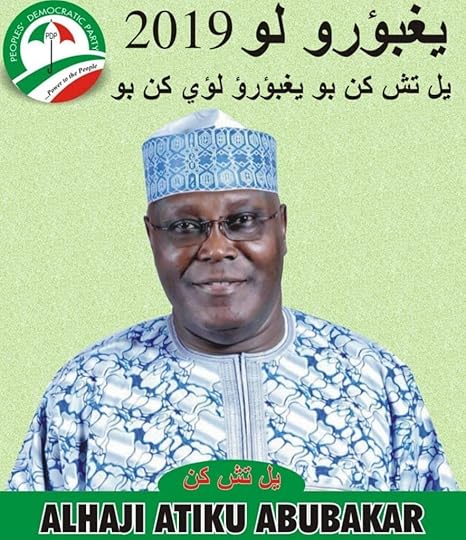

Below are examples of political campaign posters in Ajami Nupe, collected by Mustapha Kurfi. Nigerian general elections took place in February 2019, with incumbent president Muhammadu Bahari (All Progressives Congress) winning his re-election bid with 55.6%, against the 44.2% of the opponent Atiku Abubakar (People���s Democratic Party). The political posters feature Ajami Nupe use in national and regional political campaign materials.

A poster published during the 2019 general elections depicts the image of the Presidential aspirant, Muhammadu Buhari, of the All Progressive Congress (APC). The translation of the Nupe Ajami inscription reads “Vote President 2019” and “Let’s vote credible president for positive change.” To the left is the political party’s logo.

A poster published during the 2019 general elections depicts the image of the Presidential aspirant, Muhammadu Buhari, of the All Progressive Congress (APC). The translation of the Nupe Ajami inscription reads “Vote President 2019” and “Let’s vote credible president for positive change.” To the left is the political party’s logo. A poster published during the 2019 general elections depicts the picture of a Presidential aspirant, Atiku Abubakar, of the opposition party���the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The translation of the Nupe Ajami inscription reads��“Vote President 2019”��and “Let’s vote credible president for positive change.” To the left is the party’s logo. The��last inscription (in red) says��“For president.���

A poster published during the 2019 general elections depicts the picture of a Presidential aspirant, Atiku Abubakar, of the opposition party���the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The translation of the Nupe Ajami inscription reads��“Vote President 2019”��and “Let’s vote credible president for positive change.” To the left is the party’s logo. The��last inscription (in red) says��“For president.��� A poster from the 2019 general elections depicts the gubernatorial aspirant in Niger State, Alhaji Abu Sani (Lolo) of the ruling party, APC, who was bidding for the second tern and won. The translation of the Nupe Ajami at the top reads “Vote Governor 2019,”��whereas the second line says,��“Vote Governor for the Progress of the state.”

A poster from the 2019 general elections depicts the gubernatorial aspirant in Niger State, Alhaji Abu Sani (Lolo) of the ruling party, APC, who was bidding for the second tern and won. The translation of the Nupe Ajami at the top reads “Vote Governor 2019,”��whereas the second line says,��“Vote Governor for the Progress of the state.”While Ajami is thus increasingly used as a mass communication tool in the commercial and political life of numerous West African ethnic groups, there is still room for the formal recognition of its central role in mediating the grassroots by African national governments, supra-governmental bodies, and international development actors. And although there exists an increasing scholarly awareness about the importance of studying diverse historical records of African Ajami, few are those who know about Ajami as a fascinating lens into everyday livelihood practices, political struggles, and social imaginaries of many contemporary African communities.

Refuting the claim that precolonial Africa lacked written traditions

A mill owner���s advertisement for grinding grains reads: ���Ku b��gg w��llu w��lla soqlu w��lla tigadege w��lla nooflaay; kaay fii la. Waa K��r Xaadimu Rasuul [If you want (your grains) pounded or grinded or peanut butter effortlessly; come here. The People of The Servant of the Prophet (Ahmadou Bamba)]���. Image credit Fallou Ngom, 2015.

Ajami, the centuries-old practice of writing other languages using the modified Arabic script, is deeply embedded in local histories and socio-cultural practices in West Africa. Grassroots Ajami literacy has been historically high in the communities and across countries in the region. While often viewed through the lens of its religious historical origins, it is increasingly evident that the use of Ajami scripts in a variety of African languages extends far beyond religious and educational contexts. African Ajami can be observed in a growing multiplicity of secular environments, including interpersonal communication, commercial advertising, street posters, billboards and road signs, political campaign ads, and the insignia of local businesses and services.

Arising from Islamic clerical and educational campaigns of the 15-16th centuries, Ajami constituted an early source of literacy for a variety of local languages in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Yoruba, Mande, Wolof, Fula, and Afrikaans. Its history refutes the oft-prevailing claims that Africa lacks written traditions. The downplaying and devaluing of the significance of African Ajami has long characterized scholars and administrators of the colonial era, and its legacy still often persists, perpetuating racial stereotypes, limiting political participation, and obscuring ethnographic accounts of local practices and institutions.

We���re all three based at the Boston University African Studies Center and working on the research project ���Ajam�� Literature and the Expansion of Literacy and Islam: The Case of West Africa��� with a NEH Collaborative Research Grant. Collecting, digitizing and interpreting manuscripts in Ajami in four major West African languages���Hausa, Mandinka, Fula, and Wolof. The project provides a new window into the history, cultures, and intellectual traditions of West Africa.

Having flourished throughout centuries, Ajami has established itself as an important means of communication and a mediator of historical and contemporary knowledge in many areas of Africa where Qur���anic schools have been the primary source of education. Consider the example of Senegal. It is estimated that over 50% of the population of this “French-speaking country” are illiterate in French, and adequate skills in written and oral French largely remain the purview of urban elites. Many ethnic groups of the country, including Wolof, Pulaar, and Mandinka, use Ajami scripts for their written communication. Ajami Wolofal (the language of the Wolof ethnic group) is used both for religious and secular purposes in the local communities, including personal written communication such as private letters, as well as in business records and advertisements of the informal sector.

It is interesting to note that the role of Ajami as an effective tool to reach grassroots communities has not gone unnoticed by large multi-national corporations expanding their business in Africa, as well as by organizers of national and local political campaigns. The adverts of mobile telephony and mobile money services of large telecommunications companies such as Orange S.A. and Tigo of Millicom adorn huge billboards on highways and can be found painted on the walls and fences of modest neighborhood shops and kiosks. Our photos illustrate the Ajami ads of Orange and Tigo telecoms in the Diourbel area of Senegal where Ajami dominates French literacy. In Diourbel, a majority of important public announcements are first issued in Ajami, and then translated into French for wider national outreach. It is no surprise that companies such as Orange S.A., a French multinational telecommunications corporation, have understood the economic and social benefits of reaching their consumers in locally accessible and accepted ways.

Shopkeeper���s Ajami advertisement in Diourbel, Senegal, reads: ���Fii da��u fiy wecciku ay Qas�����id aki band(u) ak kayiti kaamil aki daa��� [Poems, audiocassettes, Quran-copying quality paper and ink are sold here].��� TIGO is a reference to a mobile phone company. Image credit Fallou Ngom, 2015.The growing use of Ajami in public life can be observed also in neighboring Nigeria.

Shopkeeper���s Ajami advertisement in Diourbel, Senegal, reads: ���Fii da��u fiy wecciku ay Qas�����id aki band(u) ak kayiti kaamil aki daa��� [Poems, audiocassettes, Quran-copying quality paper and ink are sold here].��� TIGO is a reference to a mobile phone company. Image credit Fallou Ngom, 2015.The growing use of Ajami in public life can be observed also in neighboring Nigeria.

During the 2019 Nigerian general elections, political posters using Ajami script were widespread among Nupe language speakers in the country, for instance. The Nupe ethnic group is situated in the Middle Belt and northern Nigeria and are widespread in Niger State as well as in Kwara and Kogi states. The origins of the ethnic group trace back to the 15th century when Nupe formed loose confederations of settlements along the Niger river. Converting to Islam in late 18th century, they retained many indigenous features of social organization and cosmology. Nupe have also historically maintained close contacts with their Yoruba and Fula neighbors, now all part of a large multi-ethnic state.

Below are examples of political campaign posters in Ajami Nupe, collected by Mustapha Kurfi. Nigerian general elections took place in February 2019, with incumbent president Muhammadu Bahari (All Progressives Congress) winning his re-election bid with 55.6%, against the 44.2% of the opponent Atiku Abubakar (People���s Democratic Party). The political posters feature Ajami Nupe use in national and regional political campaign materials.

A poster published during the 2019 general elections depicts the image of the Presidential aspirant, Muhammadu Buhari, of the All Progressive Congress (APC). The translation of the Nupe Ajami inscription reads “Vote President 2019” and “Let’s vote credible president for positive change.” To the left is the political party’s logo.

A poster published during the 2019 general elections depicts the image of the Presidential aspirant, Muhammadu Buhari, of the All Progressive Congress (APC). The translation of the Nupe Ajami inscription reads “Vote President 2019” and “Let’s vote credible president for positive change.” To the left is the political party’s logo. A poster published during the 2019 general elections depicts the picture of a Presidential aspirant, Atiku Abubakar, of the opposition party���the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The translation of the Nupe Ajami inscription reads��“Vote President 2019”��and “Let’s vote credible president for positive change.” To the left is the party’s logo. The��last inscription (in red) says��“For president.���

A poster published during the 2019 general elections depicts the picture of a Presidential aspirant, Atiku Abubakar, of the opposition party���the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The translation of the Nupe Ajami inscription reads��“Vote President 2019”��and “Let’s vote credible president for positive change.” To the left is the party’s logo. The��last inscription (in red) says��“For president.��� A poster from the 2019 general elections depicts the gubernatorial aspirant in Niger State, Alhaji Abu Sani (Lolo) of the ruling party, APC, who was bidding for the second tern and won. The translation of the Nupe Ajami at the top reads “Vote Governor 2019,”��whereas the second line says,��“Vote Governor for the Progress of the state.”

A poster from the 2019 general elections depicts the gubernatorial aspirant in Niger State, Alhaji Abu Sani (Lolo) of the ruling party, APC, who was bidding for the second tern and won. The translation of the Nupe Ajami at the top reads “Vote Governor 2019,”��whereas the second line says,��“Vote Governor for the Progress of the state.”While Ajami is thus increasingly used as a mass communication tool in the commercial and political life of numerous West African ethnic groups, there is still room for the formal recognition of its central role in mediating the grassroots by African national governments, supra-governmental bodies, and international development actors. And although there exists an increasing scholarly awareness about the importance of studying diverse historical records of African Ajami, few are those who know about Ajami as a fascinating lens into everyday livelihood practices, political struggles, and social imaginaries of many contemporary African communities.

The poetic revolution will not be anthologized

The Afrikaans poet Ronelda Kamfer. Image credit Writers Unlimited.

The recent outrage against violence against women in South Africa has revealed how we, as a nation, are responsible for the erasure of black womanhood. The eruption signals a period of tardy reflection about who falls outside the lines of citizenry and about how this is a despicable way to conceive of ourselves in relation to others.

A first of its kind, Makhosazana Xaba���s edited collection, Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000-2018 reiterates these fault lines within the South African literary imaginary by illustrating how the textual bodies of Black Women���s poetry has been largely ignored or denigrated in the world of South African letters. In doing so, this book destabilizes the notion of the literary anthology itself and demands a different reading praxis of us.

Discussing the evolution of literary collections, novelist and critic Barbara Mujica describes how anthologies ���create and reform canons, establish literary reputations, and help institutionalize the national culture, which they reflect.����� She compares this notion to an earlier form called miscellany; derived from the word miscellance, meaning ���a dish of mixed corn���, which offers ���an unordered gathering of writings on the same topic or of the same genre.���

In very conscious ways, Our Words, Our Worlds uses the form of miscellany to expose how entrenched ways of thinking cannot and do not serve the fullest expression of black female livelihood in South Africa ��� poetic or otherwise. Hybrid and ideologically non-prescriptive, miscellany views inclusiveness as a far greater ambition than overarching ideological ideals���and what better form to reflect on the nature of Black women���s poetry in South Africa than this?

For a group of writers who have been consistently overlooked by literary canons, miscellany strikes out against the cruel exclusion and denigration of women���s poetry and presents us with a more fundamental opportunity to rethink the nature of literary practice itself. This is immediately apparent in Xaba���s editorial choice to incorporate various genres in the book: Part One offers readers formal pieces of literary criticism and Part Two includes a series of personal essays by Black women poets. Meanwhile, Part Three consists of a collection of interviews and documented conversations. The lack of homogeneity in style and responsive modalities is, by far, one of the book���s strongest and most remarkable features; which in turn breeds a spirit of plurality, of voices that converge to unpack nuance rather than ones that combine to iron them out.

Consequently, each piece stands out with rare distinctiveness, but none more so than the personal essays in Part Two, which has left a mark on me. As a literary academic, I was caught off-guard, and deeply challenged by the emotional response this section elicited but I soon realized that this is precisely how the form of miscellany disrupts our preconceived ideas about the nature of knowledge production; which reminded me of Mujica���s assertion that the anthology is ���a vehicle through which a cultural elite could inculcate critical literary values.��� And when it comes to Black women���s poetry, this usually involves perpetuating ideas of their work as sentimental and unskilful. Yet Our Words, Our Worlds outwits and outperforms elitist academic and patriarchal prejudices by presenting us with a unique opportunity to learn differently. These candid and beautifully written personal essays require you to sit beside each respondent as they outline how anger, frustration and alienation forms part of the practice of poetry in contemporary South Africa. It felt like an enormous privilege to listen in on the background noise, to learn of experiences that I imagine only personal acquaintances of writers are privy to���and to consider how it amplifies the poetic sounds produced by these writers.

Both Myesha Jenkins and Lebogang Mashile highlight the grit it takes to enter male dominated poetry spaces in which women are trivialized and belittled. For Jenkins, in a world where women are told to be polite and quiet, spoken word is an act of political defiance. Similarly Mashile unpacks how her success has made her an easy target for sexist dismissals that deride both the nature of her body and her poetry. Sedica Davids, Tereska Muishond, Toni Stuart, Makgano Mamabolo, Ronelda Kamfer, Maganthrie Pillay and Phillippa Yaa de Villiers all offer reflections on how and why writing entered their lives, of struggle against largely unsupportive systems, of seeking visibility in a world and poetic canon that offers no reflection of you.

Equally intellectually and emotively charged, these essays resonated with so many of my personal experiences, and just as Muishond highlights how encountering Malika Ndlovu changed everything for her, we learn the enormous importance of having mentors; of being encouraged by women who make you feel seen. As a whole, the book itself performs this function, it has stepped up to put these stories in circulation for other Black women who are looking for stories of women who have walked the paths they are trying to navigate.

Davids highlights how poetry is about being seen as successful, but is quick to redefine success as that of learning how to use poetry as a tool for self-actualization, for finding and building reflections of our more authentic selves. And, as Stuart���s essay attests, the benefits of using poetry to explore personal vulnerability are socially and politically significant as it taps into a collective human experience. According to Stuart, ���it is in creating space for another���s voice to be heard that we build community��� and as many of these authors suggest, this occurs by first modeling vulnerability through poetry, much like these essays do. These reflections demonstrate how poetry can meaningfully cut through our preconceived ideas; a gut-wrenching surgery we are seemingly in need of as a collective if we are ever to restore dignity to all who live in South Africa.

In Part Two, though one gets a real sense of the collaboration that exists amongst Black women poets in South Africa, Part Three, which is entitled ���Conversations,��� confirms the collective nature of their engagement in both style and content. Conversation is, again, yet another form of women���s discursive practice that has been subject to sexist dismissal, but here it exhibits the richness of miscellany. These interviews include voices that listen and share space on the page with a democratic ease that does not have to result in concord, certainty or canonization of any particular individual. Just as the form of the conversation implies, these interviews attest to the consistent hard work and collective dedication that goes into creating space for Black women���s poetry. Marking this feature as a point of personal pride, Jenkins declares that ���my journey continues as a networker, someone who links women through different projects and genres,��� and, I would add, generations.

Reading through this text, I often felt ashamed to learn, for the first time, of certain details and initiatives that have gone into producing our current Black women���s poetry scene. It is indeed true that we have failed to treat this journey as properly historical, as we would if these were the lives of men. But Xaba has stepped in, producing not an archive to add to the national voice but a counter-archive that helps us to not forget what it excludes. Unlike the anthology that helps to ���define the national culture��� as Mujica suggested, this edited collection uses various strategies to draw our attention to the generative margins that Black female poets occupy in our society.

The notion of contemporary women���s poetry as inherently disruptive to the status quo is made explicit in Part One, where Duduzile Mabaso accounts for Black women who write poetry in indigenous languages. The irony that she presents here is compelling; women are seen bearing the role of tradition���as women always have���but in a manner that completely undermines the patriarchal identity that often governs the role of the imbongi. These indigenous language poets simultaneously affirm and break with the past to insist on space for women���s voices in contemporary times.

Similarly, V.M Sisi Maqagi and Barbara Boswell illustrate how women are always writing against various forms of marginality and silence. These chapters show the enormous burden placed on women���s writing that, by necessity, must represent, condemn, and then transform a society that supports the systemic devaluation of women���s bodies and being. Maqagi outlines how resistance can also find more affirmative expressions by bearing witness to experiences of overlooked pleasure and erotic delight. Taking this point further, Boswell offers a close reading of poems by contemporary Black women who affirm their bodies in ways that reframe the misogynistic idea of disgust that has been used to denigrate and control it. For example, she cites Shelley Barry���s ���pee poem,��� which narrates the humiliation of a disabled subject after their catheter leaks over everything. Yet, at the end the subject turns to witness their lover tenderly wiping down their wheelchair and states, ���cleaning my pee/this is romance.��� As Boswell explains, the malfunctioning body is not an adherence to love but a direct conduit for intimacy between the couple. Poems of this nature, she suggests, perform the revolutionary work of showing women���s experiences as multiple and complex; thereby disrupting heteronormative ideals of women���s bodies and their erotic and poetic lives.

As Mujica reminds us, ���anthologies tell us much about the cultures that produce them,��� and in contrast Our Words, Our Worlds rather proposes a ���culture��� under production. Xaba���s rigorous archival account of women���s publication in South Africa reveals both the paucity of historical recovery in South African letters, but also the rich production of Black women���s poetry in the 21st century. In her essay, Xaba explores how women negotiate their way around facts that lie ���beyond their control,��� but as this book cumulatively reveals, it is in fact women who are beyond control, who go on to produce their contexts as opposed to being produced by them. Xaba remains hopeful in this regard, in her stats, she cites a post-transitional proliferation of Black women writing poetry and of readers who ���desire a wider narration of the black women.���

Yet this remaking of public space can only occur by ensuring agency, access and control in word, body and publishing, meaning that Black women���s poetry does not and cannot settle. It is its own revolution at odds with a society that often co-opts our words and our worlds. As Maqagi opines, we must never be satisfied with unthinking celebrations of Black women���s writing, and must rather look at how women have constituted an alternative vision of public discourse in a way that enriches the fabric of South African democracy. And in Xaba���s miscellany, Our Words, Our Worlds, we see that the Black South African women���s poetic revolution will not be anthologized, because it offers something far more significant, a counter discourse that widens and enriches the public sphere, which saves it from stagnation and bourgeois singularities through acts of poetic disruption and documentation.

September 26, 2019

Witchcraft studies

A Vodun shrine in Benin. Image credit Linda De Volder via Flickr CC.

Belief in witchcraft remains a confounding issue in many African societies. An increasing number of people say they believe in the suzerainty of one God, but activities abound that show a reverence to whatever spirits remain. In Ghana for instance, filmmakers, actors, and producers in Ghallywood, who have to film a scene involving witchcraft, have been known to perform various Christian rituals like praying before and after to prevent evil spirits from coming into their lives.

The recently published, Witchcraft as a Social Diagnosis, by Roxanne Richter, Thomas Flowers and Elias Bongmba, presents an interesting convergence of humanitarian work and scholarly research to examine the gendered nature of witchcraft accusations in Ghana and across Africa. It interrogates feminist discussions on the marginalization of women accused of witchcraft. The book focuses specifically on the field of medicine, presenting and analyzing statistical data on gendered medical issues, health insurance, etcetera, as they relate to witchcraft in Ghana. It also provides readers context by exploring the notions of taboo and issues such as the stigmatization of people with albinism, epilepsy, and ostracism towards the birth of triplets in certain parts of northern Ghana. The book examines the stigma surrounding these medical issues and its connection to the widespread belief in witchcraft in that region.

In connecting the stigma towards these medical conditions across other African societies outside Ghana, the book shows that the tendency to accuse elderly people, particularly women who deviate from social norms, is not limited to Ghana. We see how the accusations and banishment to witch villages adversely shape the physical and mental health, material reality, and lived experiences of victims of these accusations. ���I am sixty-six years old now,��� one man says, ���I have been here for about twenty years now. Because of that, I missed my family for many years. However, I was very strong when I was brought here and one juju woman who claimed to be somebody who could detect somebody who has witchcraft powers.���

Though most work (documentaries especially) on witchcraft in northern Ghana have focused on the Gambaga witch village, a shelter for women accused of witchcraft, this book focuses on the Gnani, also in the north. Gnani witch village serves as a shelter to both men and women accused of witchcraft. There, the researchers interact with people accused of witchcraft, and present the subsequent social, religious, and economic implications of witchcraft accusations on their lives.

The attempt to generalize from one community to across a country and continent comes up against a number of limits, however. One of the arguments presented in the book is the claim that among ethnic groups in this area there is ���medical pluralism,��� meaning that there are no institutions or individuals assigned to be in charge of medical issues. This claim is untrue as the Dagbamba, like many ethnic groups in Ghana, have traditional healers. Community members look to these healers for remedies for various sicknesses. In fact, among the Dagbamba there are traditional health specialists in orthopedics. As far as the treatment of bone fractures is concerned, the tu��lana was/is usually preferred over western medicine. This argument of ���medical pluralism��� was based on past research on the Dagbamba that drew unfounded conclusions on the medical practices of the people in the area.

In the sphere of contemporary culture, the decision to draw on Kumawood (Kumasi���s film industry) films to understand people���s perceptions of witchcraft is baffling. Though both Kumawood and the Dagbanli film industry are Ghanaian film industries, Tamale���s film industry provides more context since it mediates the socio-cultural reality of the Dagbamba in the region where the Gnani witch village is located. This is especially since Dagbanli films like Kali Duu have complicated depictions of the ways in which African traditional religions are practiced, perceived, and have been maintained in this part of the country.

So while the book attempts to make an empirical sense of issues surrounding witchcraft accusations and diseases, it fundamentally stumbles over how to effectively explain the turn to the supernatural realm for answers. In this way, the main argument becomes a Manichean battle of western medicine against African epistemologies and belief systems. It also doesn���t help that the book���s ���feminist��� argument���that the Abrahamic religions and African traditional religions collude to reinforce harmful notions about gendered witchcraft accusations���is confused with an effort to speak from a position of ���objectivity.��� This causes it to inadvertently demonize African traditional religions. An extensive discussion of African traditional religions would have provided the authors with a stronger contextual foundation upon which to build their argument, by demonstrating to readers how witchcraft is embedded, embodied, and conceptualized within this region.

The recommendations offered to address the issue of stigmatizing elderly women who are accused of witchcraft seem practicable. Many, including Ghana���s Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection would be wise to implement them. Although people accused of witchcraft are usually women,��in the Gnani witch village there are also men accused of witchcraft. So while it makes sense that the book examines the gendered dynamics of witchcraft accusations focusing disproportionately on women, it would have made their main argument stronger to explore the roots of this phenomenon.

September 25, 2019

Self-devouring growth

President George W. Bush in Botswana, 2017. Image credit Paul Morse via George W. Bush Center Flickr CC.

Economic growth, the hegemonic progress narrative of our time, is revealing itself to be more complicated than its proponents would allow. Across Africa, indeed across the globe, national and municipal governments, investors, economic institutions, politicians, policy makers, and development experts look to growth as the basis of future wellbeing. So much is done in the name of growth. But as growth remains the common sense, the unexamined imperative, a cascade of unseen consequences, side effects, many of them environmental, also become second nature;��which is what I call self-devouring growth.

Self-devouring growth is a name for a set of material relationships whereby something with physical properties is being devoured. Unlike healthy forms of growth, self-devouring growth operates under an imperative���grow or die; grow or be eaten���with an implicit assumption that this growth is predicated on uninhibited consumption. The perversion happens in two ways: first, how the protagonists of growth envision and appropriate the resources upon which it is fed; secondly, how they attend to the production of waste that is a by-product of consumption-driven growth. This particular model of growth has become a logical means of constructing healthy, robust societies, such that there is something intractable about this thinking���grow the economy, grow a business, grow a market, grow Grow GROW! is mantra so powerful it obscures the destruction it portends.

Across the globe at present we are in a world structured by self-devouring growth. In Africa, the consequences of this fact are starting to reveal themselves as crucial water sources run dry, coastal lands flood and cede ground to the sea, pollution escalates, and people buckle under the weight of personal debt, even as jobs with decent wages remain elusive for most.

Botswana offers a good place to understand this dynamic, and to contemplate how and why we humans must think beyond a simple turn to growth. The country has been called a miracle for its ability to achieve forms of growth that produced a steady development trajectory. Yet from Botswana we can see how even that success presents its own horizon as growth becomes self-devouring. Remade under colonialism as a migrant labor reserve for racial capital, Botswana negotiated its independence from Britain, while surrounded by institutionally racist states on all sides. Yet against all odds, in the ensuing four decades it had one of the fastest growing economies in the world, a growth based mainly on the mining of its significant diamond wealth. This impressive achievement has been terrific in many ways���because the government used its revenues in part to build various safety nets and infrastructure. The standard of living has risen. There is a functioning system of universal health care, pensions, and public education. But there is also collateral damage���including an ever-widening gap between rich and poor. Botswana is now the tenth most unequal country on earth. And as I describe in my new book, growth has unleashed a set of unfolding environmental processes that threaten to bring the whole thing down.

Botswana forces difficult questions onto the table yet the moral of the story is not a simple one. If global temperatures continue to climb the way scientists predict, Botswana will be one of the many places that will have more days of extreme heat, with predicted increases in heat-related deaths, an upsurge in malaria and dengue fever and increasing drought, with attendant food and water insecurity. Grassland pasture is giving way to thorn bush, the water table is sinking, and from 2015 the central dam for the capital city and populous southeast of the country ran completely dry for nearly two years. Scientists caution that the spectacular Okavango Delta, a primary site of carbon sequestration, the hub of Botswana���s high-end eco-tourism industry���the nation���s second largest income earner and site of some of the earliest human societies, will lose biodiversity as flooding and water distribution patterns shift and the water table drops. The day will eventually arrive when the diamonds that propelled Botswana���s climb out of poverty will run out.�� Yet the story is not limited there���Botswana is but one node in a vast formation of self-devouring growth that animate economic life across the globe. The predictions for our planet are so dire that many either turn away in fatalism or dismiss it as exaggeration. Our current consumption-driven growth is self-devouring. How else are we to organize our energies? How are we to live through what is to come?

What were Batswana to do but grow their economy as best they could when the British left them deeply impoverished, and proletarianized, on a planet already polluted and warming through no fault of Batswana themselves? Batswana have managed their development trajectory quite well���and yet, all this and more is in jeopardy in the coming years. Climate change and environmental conditions have long been part of a national conversation in Botswana, where technical expertise in conservation, agriculture, and geology are deep and authoritative. And yet��� The story of self-devouring growth in Botswana helps elucidate our planetary predicament���an existential crisis if there ever was one, for those who live in the interstices of what are often described as the great political and economic divides of the contemporary world���rich/poor; first world/third world; north/south.

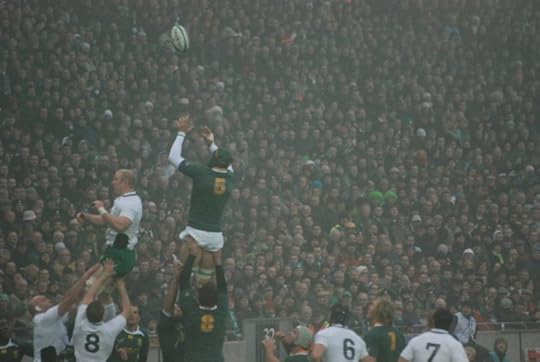

The long short history of post-apartheid South African rugby

Ireland vs. South Africa in Dublin, 2009. Image credit Martin Dobey via Flickr CC.

It is now history that all the warnings issued by the South African Council on Sport (SACOS), which dominated anti-apartheid sports protests inside South Africa, were ignored by the incoming ANC government after 1994. In every part of the country we are paying a heavy price for the ANC government’s mistaken belief that leaving apartheid sports structures relatively intact would earn them both brownie points and votes from the white electorate. In May 1990, the National Sports Congress (NSC) was launched as the sports wing of the ANC and soon the SACOS mantra: ���No normal sport in an abnormal society��� was turned on its head.

About a year or two ago, I delivered a paper at a sports conference at Stellenbosch University. I called it ���Mande|a���s Sports Legacy Revisited.��� I spoke about a fallacy that had taken root just before and after the 1995 Rugby World Cup tournament.