Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 206

August 24, 2019

Salif Keita’s incomparable call

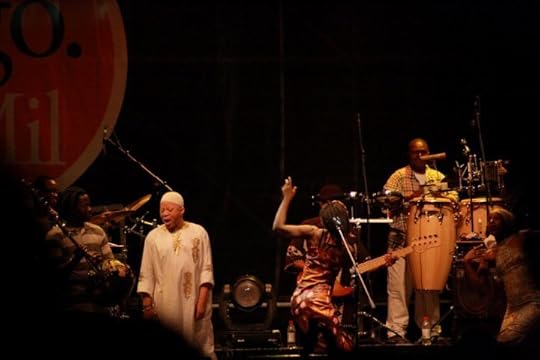

Salif Keita. Image credit Flickr user Sebasu (CC).

On November 17, 2018, Afropop superstar Salif Keita (who turns 70 in August) announced his retirement from the recording studio at a raucous concert in the otherwise sleepy town of Fana, Mali (125km east of Bamako). Released in conjunction with the concert, Keita���s most recent album, Un Autre Blanc (Na��ve Jazz 2018), would be his last. But, much like the show in Fana, the album signaled not so much a closing, as a new beginning.

The French title means ���An Other White,��� a reference to those, like Keita, who live with albinism (a congenital lack of pigment in the skin, eyes, and hair) on the African continent. On stage in Fana, Keita announced the end of a long and storied musical career in order to focus his efforts on raising awareness about albinism and combatting prejudice and violence against these ���other whites��� in Africa. In May that same year, an albino girl named Ramata Diarra, just five years old, was the victim of a ritual killing in Fana. Keita had come to make a statement.

He did so by drawing on his most precious tool, his voice. While subdued in speech, Keita���s voice is strident and soulful in song. It is difficult to imagine a retirement that would quiet its potency. Even as Keita enters the golden years of his life, his famously golden voice (voix d���or) resounds as forcefully as ever, as he demonstrated on stage in Fana. So far as one can tell, retirement from the studio does not mean retirement from the stage. Indeed, as of this writing, Keita is still on tour.

For more than half a century, the political force of Salif Keita���s music has been intimately bound up with the distinctive grain of his voice, its embodied resonance. That voice is gritty, but pitch-perfect. And it is loud. It wells up from the core of his body, takes shape in his chest, gathering texture in his throat before projecting from his mouth. At its most intense, when Keita���s voice cries out (often at the outset of a song, and again at its climax), his body is still, but tense and reverberant, every inch devoted to the act of voicing. When Keita sings, his body is an instrument. And when he cries, Salif Keita is his voice.

In the Mande heartland of southern Mali, Keita���s homeland, there are many ways to understand what it means to sing. Functionally, singing is represented as ���a call to dance��� (d��nkili), or, when addressed to a particular interlocutor, a ���laying down of lineage������a call to praise (fasada). At its most virtuosic, singing is compared to the playful banter of marketplace haggling (t��r��m��li). At its most esoteric, it commands the subtlety and style borne of a deep linguistic acumen, literally ���the language of the griot��� (jelikan).

Keita is an undisputed master of all these modes, though to achieve and be recognized for such mastery has meant transgressing quite a few social norms in Mande society (the story of which is best told by his cousin and childhood friend, Ch��rif Keita, in the book Outcast to Ambassador: The Musical Odyssey of Salif Keita). But what sets Salif Keita apart���what makes his voice ���golden��� and his vocal statements so forceful���is something more fundamental about the sung voice in Mande music. For when Keita cries out, his voice is nothing less than a call to community. (You can hear what this musically tailored ���call��� sounds like right from the start of the 1987 track, ���Sina,��� a praise song for Keita���s father.)

Perhaps the most salient cultural reference for Keita���s call is the vocal form known as ���calling the horses��� (ka sow wele). A battlefield cry intended to gather and inspire the mounted ranks of past kingdoms���a call to arms������calling the horses��� is today a vocal prelude to any lifecycle ceremony in the Mande world, calling on family and friends to come together in celebration. Keita���s incomparable call captures both senses, affectively combining a sense of activism and entertainment���politics and pleasure���that constitutes his community of listeners as a feelingfully engaged audience.

To be sure, Keita���s call resounds among multiple audiences, and has been made to imagine many communities in the course of his long career, different in kind and occasionally dissonant in character. For example, Keita���s ���stunning voice��� (voix terrible) as front man of the Rail Band in 1970s Bamako brought him and his new band Les Ambassadeurs to S��kou Tour�����s Guinea in 1975, where he famously (some say infamously) knelt before the Guinean President (some say autocrat) and improvised a praise song that would launch his international career, ���Mandjou.���

Consider also the political force of the track ���Nous Pas Bouger��� (which Manthia Diawara pithily translates as ���We Won���t Budge���), released in 1989 and directed to the plight of undocumented African migrants in France. If ���Mandjou��� charts a musical path from the local to the global (via the postcolony), ���Nous Pas Bouger��� interpellates the everyday realities of those marginal to, yet no less embedded in the forces of globalization. All of these communities���urbanites and migrants, cosmopolitans and autocrats���have, at one time or another, heeded Keita���s call.

Which brings us back to Fana. By announcing his retirement as a ���call to arms��� in support of albino communities throughout Africa, through a ���call to dance��� before a select gathering of friends and locals, Keita affirmed, once again, the irreducible potency of his verbal art, at once intimate and expansive. Whether or not Keita decides to enter the studio again, it is clear that his politics will remain substantively vocal, and will continue to resonate among communities from Fana to the world.

August 23, 2019

Jour des morts

Image credit Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.

For English click here.

For Aranud Esquerre , “the living have unimaginably changed their relationship to human remains. It is undoubtedly through this thought that the reflection that we begin here, supported by an empirical field investigation at once exciting and dangerous, at the heart of the Gabonese political power in collusion with the fetishism, the sorcery that we are interfered. The latter leads to a finding that, whenever a political election is in sight in Gabon, graves are systematically desecrated and looted since October 2006.

This November 2, 2012, the cemetery Mindoub�� welcomes the world. The family members of the deceased come for the traditional cleaning of the graves or to “spend time” with the dead, as they say in Libreville. This is the sign of a society that has not broken with death as in postmortal western society . In Gabon, All Saints’ Day is an important day, during which Christians commemorate the feast of saints and dead. Of Catholic origin, this celebration is characterized by requiem masses and the traditional cleaning of graves in cemeteries. It is a moment of communion with the disappeared and the highlighting of the place of the dead in the social life of the living .

Cr��dit d’image Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.

Cr��dit d’image Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.On November 2nd, however, brawls broke out as well as cries of indignation. The reason for this anger is that some places in the cemetery have been rendered inaccessible by lack of maintenance, sewage, and collapse of the fence. Indeed, the cemeteries in Libreville are all in a state of extreme abandonment and are sometimes closed to the public. Some graves are literally buried in tall grass. Or the family discovers that, due to lack of space, several dead people were buried on the same compound, a common practice in Libreville, where we speak of “elevator” burial. Even worse, parents realize that graves have been desecrated. A few meters from the entrance of the cemetery, a privileged area by the desecrators of graves, Mr. Mba discovers that his sister’s resting place was smashed and looted. And most importantly, his sister’s grave was emptied.

Selon mon enqu��te de terrain, c���est plus de cent cinquante tombes qui ont ��t�� vid�� de leur contenu �� Mindoub�� entre 2009-2012.�� L���indiff��rence des pouvoirs publics contraste avec la col��re, l���indignation et la frustration des parents des d��funts rencontr��s sur les lieux.�� Pourtant, le vol des morts n���est pas une question taboue au Gabon.�� Au contraire, c���est un ph��nom��ne social manifeste qui fait la ����une���� des journaux et du��kongossa (rumeur) �� Libreville, lesquels accusent g��n��ralement les hommes et femmes politiques, s��nateurs, d��put��s, ministres et autres officiels d���y ��tre impliqu��s.

Dans cette ��conomie du corps, du magique et du politique, les cimeti��res �� Libreville et dans le reste du Gabon alimentent le march�� occulte des restes humains. Ils sont devenus des sites d���extraction d���une ����mati��re��premi��re �� exceptionnelle que nous appelons ����or blanc����, au sein d���un vaste r��seau de recyclage magique et th��rapeutique du corps humain.

Cr��dit d’image Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.

Cr��dit d’image Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.Finally, this article starts from the looting of the dead, observed during All Saints Day in Gabon, in order to highlight the nature and mixes of all kinds that structure the Bongo-PDG political system; who uses the body (dead and alive) to live. It is a necrophagous political system that does not hesitate to draw its vital force in death. All this suggests that Gabonese political power is in reality the sovereign power theorized by Foucault.

Day of the dead

Image credit Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.

Pour le Fran��ais cliquez ici.

For Arnaud Esquerre, noteworthy sociologist at EHESS (Paris), ���the living have changed their relationship to human remains in an unprecedented way.��� It is undoubtedly through this notion that I was inspired to embark upon a dangerous but exciting investigation into the heart of Gabonese political power, by meddling in the shadowy world of sorcery. My years-long investigations have resulted in the observation that each time our country has approached political elections, tombs have been systematically desecrated and pillaged. For instance, as early as October 10, 2006, the government daily L’Union reported more than forty tombs looted at the well-known Mindoub�� cemetery.

Six years later, on November 2, 2012, the cemetery of Mindoub�� welcomed the public. Family members of the deceased came for the traditional cleaning of the tombs or just to ���pass the time��� with the dead, as we say in Libreville. It is the sign of a society which has not distanced itself from death, as in many post-mortal western societies. In Gabon, All Saints��� Day is an important day during which Christians of all denominations commemorate both the saints and the deceased. Of Catholic origins, this celebration is characterized by requiem masses and the cleaning of graves. It is a moment of communion with the departed and showcases the privileged place of the dead in the social life of the living.

On this particular Friday, however, brawls and cries of indignation erupted into the torpid Libreville smog. The reason for this anger was that some places in the cemetery had been rendered inaccessible by lack of maintenance, open sewage, and the collapse of fencing. Indeed, most of the cemeteries in Libreville remain in a state of extreme neglect and are sometimes closed to the public. Some graves are literally buried in tall grass. Or, the family discovers that due to lack of space, several dead people were buried in the same plot, a common practice in Libreville where there is often talk of such “elevator” burials.

Even worse, relatives realize that graves have been desecrated. A few meters from the entrance to the cemetery, an area favored by grave robbers, Mr. Mba (whose real name remains anonymous) discovered that his sister’s resting place was smashed and looted. And, most importantly, his sister’s grave was completely emptied of its contents.

Image credit Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.

Image credit Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.According to my own field survey, more than one hundred and fifty graves were emptied of their contents in Mindoub�� between 2009-2012. I knew this because as part of my direct participation, I worked with local women volunteering to clear the cemetery���s trash and helped the guardian to shut opened graves���an ungrateful task given the sheer weight of the concrete. I also conducted several interviews with municipal officials. The indifference of these public authorities contrasted with the anger, indignation and frustration of the relatives of the deceased on the scene.

Yet the theft of the dead is not a taboo issue in Gabon. On the contrary, it is a social phenomenon that continues to make headlines in newspapers and features frequently as a subject of kongossa (rumor) in Libreville. Politicians, senators, deputies, ministers and other officials are generally accused of being involved. On April 28-29, 2012, Jonas Moulenda penned an article for L���Union titled ���Five Human Skulls Discovered in a Cabin;��� while on January 3, 2013, the bi-monthly news and analysis periodical, La Nation, implicated Pierre Claver Maganga Moussavou (recently removed as Vice President by Ali Bongo) of ritual crimes. Then in 2012, Gabriel Ekomy, a senator from the Estuary, was openly accused of pillaging graves, though he avoided the fate of Jean Ondeno Rebieno, a popular singer arrested in 2008 for the same act. More recently in 2015, Rigobert Ikhamboyat Ndeka, a Parti D��mocratique Gabonais (PDG) deputy from Ogoou��-Ivindo, was publicly cited for his involvement in the same scandal.

In this economy of the body, magic and politics, the cemeteries in Libreville and the rest of Gabon feed the occult market of human remains, all of which is evident to this day for those willing to look. The cities��� untamed graveyards have become sites of extraction of an exceptional “raw material” that we call “white gold,” nodes within a vast network of body parts where value is measured by the potential for magic and therapy.

Image credit Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.

Image credit Lionel C��drick Ikogou-Renamy.The theft of bodies and the desecration of graves are just a few elements, which betray the true nature of the political system put in place by the Bongo-PDG tandem, in place for 51 years. In both symbolism and reality, it is a regime which uses the body (dead and alive) to live. It is a necrophagous political system that does not hesitate to draw its vital force in death, even as death and paralysis threaten the system���s leading beneficiaries. In a very real sense, one can say that the biopower theorized by Foucault and others is embodied in the methods and idiosyncrasies of Gabonese political power.

August 22, 2019

The problem with post-race comedy

Image credit Marta Tveit.

I am a melanin-rich lady, and the other day my (very) young friend turned to me and went: ���I cut myself, I need some cotton. Could you go pick some for me?�����I thought: Did a Norwegian child just call me a field slave? I just stared at him. At that age all they want is a reaction, any reaction, rage, sadness, whatever. My poker-face, therefore, made him nervous, and he began defending himself. It was an argument I have heard many times before: ���That���s what black rappers and comedians call each other and stuff! Like, ���cotton-picking ass n*gga���. it���s just for fun! We���ve got to be able to joke about everything. You can���t get mad, I���m brown too!���

Post-race giggles

My young friend is half-Palestinian, half north-Norwegian. He goes around calling himself Sami the Sand N*gga. When I was young, I would also crack jokes about the color of my skin all the time, encouraging those around me to do it as well, making it ���safe.���

Here in Norway, one of the most progressive, well-adjusted countries in the world, race-jokes are becoming quite meta, or post-… something. Cracking a race joke is like saying ���our millennial generation is so post-everything, we know about history, we are so down with human rights and what not that we can allow ourselves to go around calling each other dirty Jew and potato (a Norwegian slur for white people) and sand n*gga.��� A new wave of post-modernism, just look at how crazy memes have become, increasingly detaching signifiers from their old meanings and laying them out side by side to dry in the sun.

But even while on this meta-wave, joking about my color never felt quite right. As I got older, I began to ask myself who I was doing it for; it wasn���t necessary, and I didn���t really need it to fit in, so why was I still doing it? For my closest friends, I think it was quite obvious that my slightly manic “black humor” came from my own insecurity about being dark-skinned in predominantly white spaces. Not as funny when you see it like that.

Like my young friend, I���ll hear people say: ���I love comedian so-and-so, he talks about everything man, just says it like it is! NO LIMITS!���

These types of statements are strikingly similar to people describing why they voted for Donald Trump. I wondered if having no filter really is such a good thing.

Of course, an entertainer has to be able to speak the language of the audience. But there are smarter ways of doing it without basing your show solely on stereotypes for instance. Comics have power, especially over the young, and perhaps more than we care to acknowledge.

Dancing monkey comedy

There is a certain type of comedy I like to call “Dancing Monkey Comedy.” Old school, based solely on racial fault lines and stereotypes, which is just a tiny step up from the minstrel show. The subtext to the minstrel show was “Look! Fake black people! Hilarious!” In modern Dancing Monkey Comedy, the underlying subtext is: “Look at me! I���m a black man! Black people are known for doing certain things! Isn���t that hilarious?”

It must be extra challenging being an entertainer of color in a predominantly white space. It is difficult to strike the balance between laughing at everything and maintaining self-respect. When I was cracking jokes based on my color, the laughs would switch at some point; at first my white friends would join in because I initiated it, and suddenly it was just a bunch of white kids pointing and laughing at the black girl for being black. What happened, we were supposed to be so “meta?”

I felt like I had to keep it going, keep making black jokes, I���d painted myself into a sad-clown corner.

I recently heard a successful young comedian, Jonis Josef, talk about being a black comic in Norway. He described how he came to fame by basing his sets solely on Somali stereotypes and black jokes. Things were good, until he toured the provinces up in the very north of Norway. There people laughed just a little too hard. He experienced what it meant to walk the fine line between being laughed with and laughed at. Being part of the woke post-everything millennial generation, he had made some assumptions that clearly did not apply here. He felt like he had dragged his family and entire culture through the mud. And for what? For kicks? To entertain white people? The experience sent him spiraling. For a whole year after that, he refused to mention his background or color, talking about anything else on stage, traffic lights, audience members, whatever. But that felt wrong as well, after all creators draw material from what they know. Now he does get personal, but in a very different way.

Being a black comic in a predominantly white space is a difficult role to play also because of the responsibility inherent in being one of few role models for minority youngsters. The kids are hanging on your every word, Jonis, watch your step. They are learning from you how to talk about minority culture, race and their own space in this society. Entertainers, rappers and comics and the like, are telling young people of color how to feel about themselves in between those lines they spit.

���I can say that, I���m black!���

What really makes my blood boil is when people of color, especially comics, legitimize whatever they are saying by referring to their skin color. That act in itself sets us all back, by making skin color more than skin color, by strengthening and re-entrenching racial essentialism. And young people, children, like my friend, are watching very carefully. They will crack jokes about slavery, Africa, whatever, and end by saying “it’s okay I���m black.” The color of your skin does not qualify you for anything other than buying special skincare products my friend. Imagine how absurd it would be if a white comedian held a set completely denying the holocaust or something and ended by saying “It’s okay, I���m white!” It’s cowardly and it’s a cop-out.

We���ve got to joke about everything.

Like when girls go around calling each other sluts, bitches and whores, ���but like, in a fun way.��� In the same way that frequent use of the n-word does its part to keep racial essentialism alive, those type of words do their part to promote a reductionist view on women, even if the intention behind using such words is good and can feel empowering in the moment.

The problem is we are keeping historically-charged words alive when we don���t need to. Why? We don’t need to do that. Let it die. Just let it die already. Like when I was making jokes about the color of my skin; it came from a place of insecurity. That has never been a good starting point for well-crafted humor. Let it die. The world is full of funny things, leave horrible words from the past in the past.

We are keeping dead words, with all their connotations, artificially alive. I call them zombie-words because language is not set in stone.��Language is dynamic and everyday conversation is among other things instructional. We are continually teaching each other how to talk to one another, what is acceptable and not, what is funny.

It is nearly impossible to separate a word that has such strong historical meanings from its history and connotations. A zombie-word, kept alive with good intentions, yet reeking of a horrible past, still creepy, never quite as good as a real solid new word.

Power to everyday people

I am not saying we shouldn���t talk about difficult subjects or ever mention race. But everything is context. I would like to read an academic article, but would not perhaps like to go to a full night���s stand-up show about female genital mutilation. I���m not saying this type of show should be illegal, we have free speech. Some people might get mad, but that’s the whole point, right?.. To get any reaction, no matter what it is? If it is really true that the more shocking the funnier, if shock-factor is the only criterion for good entertainment, then FGM-Extravaganza Night would be a hit.

It appears to me that female comics competing in a male dominated world, seem to often rely on “the shock effect,” saying vulgar or outrageous things in order to have impact and not be forgettable.��Women are taking on the shock factor, trying to compete in a male dominated world. Chafing jokes all damn day (that’s you Amy Schumer), but it’s so painfully crude. Get into the craftwomanship of it, step it up. 2 Dope Queens are lifting up black female voices, in a way that you start to forget that they are black and female and you just hear stories, voices. Isn���t that the whole idea? To move beyond?

And don���t give me that ���Shucks, you can���t joke about anything nowadays,�����and go hide in your Reddit stream. My favorite comedian, Gareth Reynolds, A writer on Comedy Central and co-host of history podcast The Dollop, has never in his life cracked a joke based on the premise: ���Black people are fundamentally different and that is hilarious.��� And he is certified funny.

You see creatives like Donald Glover, challenging the old ways of approaching race in entertainment. Atlanta is funny as hell, but I don���t feel devalued as human being by watching it.

Comics, you can do better, I know you can.�� ��

On the whole, I don���t think ���joking about everything��� is the answer, even if you are part of the group you are putting down. If we are honest with ourselves, we are keeping zombie words, like n*gger and slut alive, essentially out of insecurity. While it is a way of processing pain, it is not fighting racism; calling one another sluts and whores is not weakening the patriarchy. So, we can just stop. Leave it in the past. Let it die already.

The real struggle against outdated mindsets happens in everyday life, everyday conversations. Blazing leaders and brilliant thinkers might lead the way but most of us will not dedicate our lives to the struggle. We will become nurses and office workers; we want to see Spiderman on the weekend and get that fancy new washing machine, and that’s it. We are too busy picking up the kids at daycare and planning spring break to be PC-warriors. No time for marching or thinking about words like essentialism, decolonization or pseudo-feminism. And that���s okay! Don���t feel bad! On the other hand; there are more of us, millions, invisibly fighting the good fight in everyday life. Everyday people still alter minds, drip by drip, through our strongest weapon: everyday conversation. In fact, with small talk and humor.

As audiences, we also have power. El festival de Female Gential Mutilation would fail, not because it is prohibited, but because most people wouldn���t find that funny. That is audience power.

We can reflect on what is funny and why is it funny. We have the power to alter the premises of our everyday conversations. We can change the significance we attach to the tiny differences in our appearance.

Language and conversation are acts of creation, so what we laugh at matters. Jokes of the dancing-monkey-comedy type rip open old wounds, re-digs the fault lines that the old-school race narrative imagines between black and white, again and again and again.

Let���s all step up the game, together.

Thankfully things are changing. It is not enough to just be black as a TV presenter here in Norway anymore. You���ve got to deliver. Similarly, a black comedian with an entire hour about being black��� It’s not that people would get mad or anything, it would just be dull. And that’s the key, that’s where I want to get. Let’s “make racism dull again.”

Make stereotypes dull again, for that matter. Use your audience-power, you don���t need to commit much, just don���t laugh if you don���t find it funny. You don���t have to laugh just cause he���s black, in fact, doing so is slightly racist. Laughing out of politeness at a black comedian who just repeats the n-word 65 times a minute is not only untrue to yourself; it is holding us all back. Say loud and clear “that guy was terrible!”

Things are changing, but content does not come from the God of Netflix or whatever, it is created in response to what you and I like and find funny. Even in small things, in everyday life, content is created in response to demand. When your drunk-ass buddy cracks his 19th pussy-p��t�� joke that evening, have the courage to say: “Dude that is fucking lame. Let���s do something else.” He���s only doing it because he thinks it’s what you want, what will make you accept him. Grab him by the teaching-moment. Pussy-p��t�� is lame.

So, I didn���t laugh at my young friend���s slavery-joke in the end. It’s gonna be a NO from me dawg. Not because it was racist, ignorant of history or offensive. Just because��� that’s just lame.

Imagine a comedian who only talks about the size of his ears. All day, all his shows, hour after hour about those giant kettledrums. He won���t quit, he goes on and on about big-ear culture, how big-eared people are known for liking pineapple or some shit, talks irreverently in passing about the bloody big-ear massacre of 1882, how small-eared people can���t dance.

That���s how bad, dull and obscure I want race-based comedy to get in the end. I want the audience to go: “Common man, talk about something else. Talk about something that matters.”

August 21, 2019

The confrontation with France’s slave past

Killmonger. Still from Black Panther via Marvel/Disney.

In one of Black Panther���s memorable scenes, Erik Killmonger, the cousin of Wakanda���s new king, views an exhibition of African art at a fictitious British museum. When the guide describes the mask in a glass case as Beninois, the film���s anti-hero objects, corrects her, questions the museum���s display of stolen objects, and eventually rescues the artifact from its colonial captivity. It is a scene that crosses my mind every time I visit a European museum, which I did several times this summer. While the fraught history of museums is being addressed through initiatives to decolonize museums, my experience at three different European museums was a reminder of the tremendous amount of work left to be done. Even museums that have launched expensive initiatives to re-frame their colonial heritage from a more critical perspective are complicit in performing erasure, lacking context, and making a spectacle of suffering. In the midst of debates about the re-institution and repatriation of African art, these exhibitions put the problems with memorialization of a violent and traumatic past on prominent display.

At the Aquitaine Museum in Bordeaux, which re-opened earlier this year after a ten year��renovation project, slavery is acknowledged primarily as the source of economic wealth for the French port city. The enslaved people whose lives were sacrificed to amass this wealth are mere lifeless objects. The section in the first of four rooms trumpets the ���black presence��� in Bordeaux. Portraits of mixed race people of color include a paintings of an enslaved woman with a white child. As Denise Murrell���s groundbreaking exhibition��at the Mus��e d���Orsay,��Le mod��le noir, brought into great relief, black subjects have been rendered invisible in paintings throughout art history. These paintings depicting life for the Bordelais bourgeoisie are certainly no exception. The enslaved people in the frame of the painting function as objects signaling the wealth of their owners. No details about their identities are included.

Among the artifacts presented are replicas of ships, maps of colonial Saint-Domingue and the French Antilles, shackles for hands, necks and ankles. These objects evoke the violence of slavery without calling it into question. Much of the exhibition focuses on the commercial aspects of the transatlantic slave trade, emphasizing slavery as first and foremost linked to capital. The written descriptions are especially troubling. For example, the continued use of ���la traite n��griere,��� which translates from French to the ���trade of Negroes.��� This repetition is dissonant with concerted contemporary efforts to use ���enslaved people��� rather than ���slaves��� as a way to center the humanity of the victims of the slave trade.

Another description reads:

The triangular trade involved the shipping of products to the African countries where they were exchanged for slaves. Nearly a hundred different products were in demand in Africa, including cotton cloth, silk, bar iron, manufactured goods, guns, ammunition, alcohol, cowry shells (used as a form of currency) and tobacco. The slaves were then sold or bartered in the American colonies in exchange for colonial products���sugar, tobacco, indigo, cotton, etc���which were shipped back to Europe and sold.

Missing from the text is how the products were procured���through the devastating labor of the enslaved people forced to work on the plantations in the Caribbean. The absence of this connecting point emblematizes the erasure that the museum repeatedly performs.

There are also several references to slavery as a common practice with a long history that dates back to medieval times, as well as its widespread use on the African continent. As one student and I discussed, the plaques with these descriptions operate as implicit disclaimers seeking to justify the French involvement in the slave trade. Furthermore, that no distinctions are made regarding how slavery was transformed because of racism undermines any efforts to honor the descendants of the slave trade.

Another disturbing feature is a short film documenting scenes of the enslaved Africans being forced onto a ship���s hold, where the captives remained in inhumane conditions while enduring the Middle Passage.

While some French scholars have argued that the changes in the museum have been appreciated by people of African and Antillean descent who are pleased ���to see their history on display,” for me and my students the encounter and non-encounters with the slave trade were remedial at best, and often jarring.

Overall, the Aquitaine Museum was a huge disappointment. Still, the questions that the Aquitaine Museum introduced are worth taking seriously. In the midst of a French debate over the ���restitution of patrimony��� and the need to return objects taken under colonial rule back to their countries of origin, how should the history of enslaved people be accounted for? What does the repatriation of objects held in museums mean for the descendants of people who were also held captive, first in ships then on plantations? As Crystal Fleming points out in her book Resurrecting Slavery: Racial Legacies and White Supremacy in France, part of the difficulty of grappling with this racial past is that it must be done in the context of a French society that purports to be color-blind. As the lived experience of racism that Black- and Arab-French people continuously decry attests, France���s color-blind ethos is at best a myth and at worst a pernicious cover-up.

In Noirs d���Aquitaine: Voyage au Coeur d���une presence invisible, Bordeaux-based academic Mar Fall examines the black past and present in order to ask questions about the future. Throughout the book he interviews a number of Black Bordelais scholars, activists, politicians, and civilians on the question of blackness in the port city. In my view, the hope that he expresses in the conclusion for people to be ���libres d���envisager leur present et leur future dans le monde��� [free to imagine their present and future in the world] begins with confronting the past. As it is today, the Mus��e d���Aquitaine is an example of what it looks like when that confrontation barely scratches the surface.

August 20, 2019

The Erasure of Dulcie September

Robben Island / Mayibuye Archive.

On March 29, 1988, Dulcie September, the Chief Representative of the ANC for France, Luxembourg and Switzerland, took the elevator to ANC���s fourth floor office in 28 Rue des Petites ��curies in the center of Paris. As she opened the door, she was shot five times in the head with a silenced 22. calibre rifle. Her murder has never been solved and September is not a household name in South Africa. Neither of those things are coincidental.

Dulcie September grew up in Athlone on the Cape Flats in Cape Town. Apartheid would only become official policy years later, but racial segregation was already deeply entrenched. Her father was a school principal, but also, as Michael Arendse, Dulcie���s nephew says, ������ an abusive man.��� Dulcie stood up to him and eventually had to leave her childhood home. She became a teacher and an activist, eventually joining the newly formed National Liberation Front. The NLF worked to organize black South Africans (what they termed non-white South Africans)��in the struggle against imperialism and for political freedom. It was mainly a call for unity against oppressive institutions.

In October 1963, the security police arrested Dulcie for her NLF activities. Dulcie spent six years in jail where she experienced mental and physical abuse at the hands of the authorities. Three years after her release, she left South Africa for London. Here, she joined the ANC, already banned in South Africa and operating from exile and eventually moved up the ranks to become the chief representative in the Paris office.

The relationship between South Africa and France has been a long and complicated one. The first contact between South Africa and France was in 1671 when the Dutch allowed Huguenots (French settlers claiming religious persecution in France) to settle at the Cape Colony.��This population was integrated into the local white community.

During apartheid, France and major French corporations were some of the most loyal supporters of South African apartheid government. French companies quickly became the second largest suppliers of arms to South Africa.

There was some pushback from within both France and South Africa against these oppressive ties. In 1965 representatives from the French and South African communist parties had a meeting, where solidarity was discussed. However, the French government continued to support South African���s repression by supplying arms.

At the end of 1983 Dulcie was appointed chief ANC representative in Paris. Then, between 1986 and 1987, September became involved in an anti-apartheid movement called the Albertini Affair, which angered and embarrassed both the French and South African government.��(A French national, Pierre Andre Albertini, on an exchange program at Fort Hare University, had become politically involved in South Africa. He was arrested. September, as ANC representative, became a vocal activist for his release and insisted France refuse to accept South Africa���s new ambassador unless Albertini was released. Neither the French nor South African governments were very comfortable with the attention this brought to their close relations.)

One year later, in March 1988, Dulcie was murdered. She was 52-years old.

At the time she was murdered, Dulcie was beginning to understand, how powerful networks involving European banks, arms companies across the world, shipping companies and middlemen made fortunes arming apartheid in violation of a mandatory UN-embargo. What all these actors have in common, is that none of them have been held to account to any meaningful degree. This is detailed researcher Hennie van Vuuren���s book Apartheid Guns and Money: tale of profit, which is the starting point of the podcast.

A single, but telling example, is the French arms company Thompson CSF, which was heavily involved in the illegal arms trade with South African during apartheid. Later, the company changed its name to Thales. To this day Thales is part of the corruption case against former South Africa President Jacob Zuma stemming from the 1999 arms deal. A deal that was not only mired in corruption, but also meant that the ANC government spent billions of Rand on weapons the country did not need. Weapons often bought from the same companies and people who had armed their opponents during the struggle.

In South Africa, there are no statues of Dulcie September, no airports or grand boulevards named after her. This is in spite of the fact that she was the highest ranking ANC-official ever to be killed outside of Southern Africa. In part, the podcast series is an investigation of why she has not become the icon her career and sacrifice would suggest. Of course, there is no simple answer to this, but on the day she could have turned 84, it is worthwhile to consider a couple of factors.

Firstly, it is Women���s Month in South Africa. For many, it is also an opportunity to highlight how South Africa���s policy of non-sexism continues to fail when for example three women die by the hands of their partner every day. This tragically mirrors the experience of woman freedom fighters who not only experienced violence and sexual abuse at the hands of the security forces, but also from their own comrades. As former MK-commander and current speaker of the South African Parliament Thandi Modise has argued, women were not only discriminated against during the struggle, but also in its history, where especially the armed struggle has been largely recounted from a male centric perspective.

This silencing of women���s role in the struggle is undoubtedly part of the reason for the erasure of Dulcie September. Archival documents show, how she always spoke up against gender based discrimination both outside and within her movement. But it is not the only reason. Beyond her duties as chief representative, we know that Dulcie September was investigating the illegal arms trade between South Africa and Europe during apartheid. Much of trade was coordinated through the South African embassy in Paris. Before Dulcie September was assassinated, she reported she was being watched and feared an attempt on her life. In spite of this, she never received protection from neither the French authorities or the ANC.

Remembering Dulcie September is not only an inconvenient reminder of past and present gender based discrimination. It is also a reminder of the seamless way some ANC leaders entered into corrupt relationships with the very people arming the murderers of their comrades. The cost of erasing Dulcie September and others like her, is not only the billions that could have been spent on a society in dire need. It is also the opportunity to accurately understand the past in order to improve the future. And, of course, justice.

They Killed Dulcie is made by Sound Africa and Open Secrets. The podcast draws from research by Open Secrets for the book Apartheid Guns and Money: A tale of profit.

August 17, 2019

Long live Ruth First

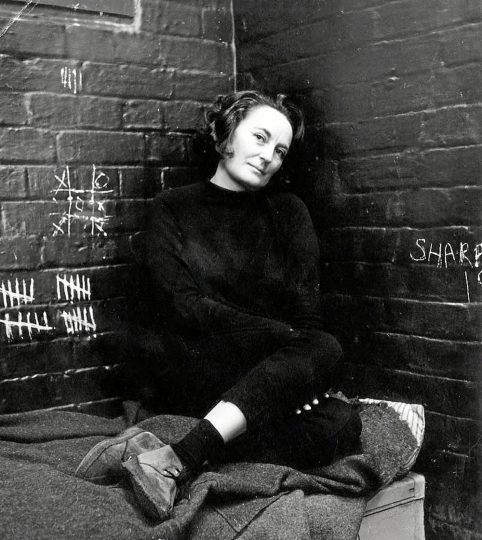

Ruth First, in 1966, in a promotional image for the film about her detention in South Africa.

At a memorial meeting for Ruth First, after she was assassinated on the streets of Maputo by South African agents, Ronald Segal, another prominent exile figure and her close friend, described Ruth, as a ���journalist, author, intellectual, teacher,��� whose ���whole life was essentially a political act.���

I remember Ruth as elegant, forceful, efficient and often impatient. Ruth���s remarkable body of writing ��� from investigative journalism to memoir to political and literary analysis ��� was driven both by her political commitments and by her frank curiosity about people and the worlds they inhabited and was characterized by the clarity of her prose, her rigorous research, her careful use of the narrative form and her interest in addressing the widest possible audience. Jack Gold, who directed her in Ninety Days, the 1966 BBC adaptation of her vivid account of her detention under the notorious 90-day law, in which she played herself, said of the script that she wrote: ���her [use of] language is absolutely phenomenal, so clear, clean, powerful and of the essence. [There is] nothing wasted��� in her storytelling.��� (He made these comments at a screening of the film on the 20th anniversary of her death, 2012, at the University of London School of Advanced Study.)

Nelson Mandela recalled her in her student days at the University of the Witwatersrand as ���brilliant����� [S]he did not suffer fools, she was energetic, systematic, hard-working ��� and make the maximum effort to produce the best result. She was fearless, she could criticize anybody and she rubbed people ���in the wrong way at times.��� As a student, Ruth engaged in disputes with J.D. Rheinhalt Jones, Director of the South African Institute of Race Relations on behalf of the Young Communist League and also with Mandela and Walter Sisulu of the ANC Youth League. She continued to differ from liberal and from nationalist politics. She always identified with anti-colonial solidarity.

Ruth was drawn to practical political action. As a student, Ruth taught literacy to African workers at the night schools run by the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). In 1946, during the strike of the African Mineworkers Union, the largest action by black workers in South Africa until then, Ruth, recently graduated, engaged in duplicating and distributing pamphlets, quitting her job at the Department of Social Welfare of the Johannesburg City Council. She then turned to journalism. She was a prolific contributor to a succession of leftist weekly newspapers, which were each banned and renamed until 1962. From 1947 Ruth, alongside Gert Sibane and the Rev. Michael Scott, exposed the brutal treatment and forced confinement of farm laborers in the, then, Eastern Transvaal. In 1954, she became editor of Fighting Talk, a literary journal that carried political comment and created spaces for new fictional writing.

Questions of capitalism, (male) labor, and class were always at the center of Ruth���s practice and writing. In her journalism, Ruth confronted South African capitalism in the cities and in its most brutal forms, on farms and in the mines. Ruth published three particularly incisive analyses in Africa South (in Exile) edited by Segal. The first was an account of the bus boycotts that began in Alexandra, a black township north of Johannesburg, and spread through the Reef, down to Port Elizabeth: ���Through the long weeks of the boycott, the political initiative passed out of the hands of the Government and the Cabinet and into the hands of the people,��� she wrote. The second documented the recruitment of contract labour and the rounding up of ���foreign natives,��� supplemented by private farm prisons to labour on Bethal potato farms. The third presented a compelling account of the emergence of the political economy of Southern African labour migration since the turn of the twentieth century that preceded later abstract Marxist analyses. Mining companies she explained, found labour that was ���abundant��� and cheap��� by ���us[ing] only contracted migrant labour at cut-throatwages, on the assumption that African mineworkers���brought from their rural homes to the Reef for stipulated contract periods���were really peasants, able to subsidize mine wages from the land��� by establishing ���a labour recruiting monopoly and [reducing] costs of wages, food and quarters by setting up a highly centralised system for controlling wages.���

In conveying the impacts of that system far beyond South Africa���s border, she prefigured her later research and writing on Namibia, in South West Africa (1963) and in Mozambique:

While two in every three African miners on the Witwatersrand come from countries other than the Union, and one in five from a Central and East Africa rapidly advancing towards independence, low wages, debased compound life, the suppression of all trade union activity, contraventions of international labour conventions���all these are the concern not only of South Africa, but of the peoples of half a dozen African countries, indeed, of all the continent.

In 1975, Ruth was to perceptively note that, ���All too often, Marxist analyses��� [are] mechanically transposed to African societies schema of the class relations characteristic of western capitalism.��� She was not immune to these tendencies. The conclusion to Govan Mbeki���s Revolt in Pondoland (1964), which was likely penned by Ruth, its editor, reveals a conception of political consciousness despite numerous rural rebellions and Mbeki���s own analysis: that only when African ���workers were removed from the land and based on factories [would] they turn from their Chiefs and their tribal loyalties.���

Ruth later reflected that her family and their white friends enjoyed ���the good living that white privilege brought��� but that this way of life appeared more precarious, ���as the struggle grew sharper [and] the privileges of membership in the white group were overwhelmed by the penalties of political participation.��� After the government banned the CPSA in 1953, the ���Congress Alliance��� brought together the ANC, the South African Indian Congress, the Coloured People���s Congress and the (white) Congress of Democrats. The last three were led by the reconstituted underground South African Communist Party (SACP). The ANC always claimed leadership of this alliance. Alongside her husband, communist lawyer and activist, Joe Slovo, Ruth contributed to the Freedom Charter adopted by the Congress of the People of 1955, which owed more to the U.S. Declaration of Human Rights than to the Internationale. The regime responded by charging 156 men and women, Joe and Ruth included, in the Treason Trial which lasted from 1956-1961.

She was not involved in the initiation of the Federation of South African Women by two fellow communists,��Hilda Bernstein and Ray Alexander in 1954, when the Women���s Charter was adopted. It was��only partially��incorporated into the Freedom Charter. Ruth was directly involved in the activities of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the newly armed wing of the ANC.

Exiled to England in 1964, where she and her daughters joined Joe, Ruth���s communist identity and presumed Marxist bias went ahead of her and was she unable to find secure employment as a journalist. Encouraged by Segal, she began a new career as an author, working across genre and posing diverse questions. While 117 Days (1965) eloquently documented her experience of detention, The South African Connection: Western Investment in Apartheid, which she co-authored with British journalist Jonathan Steele and activist historian Christabel Gurney, linked international capitalism with apartheid.

Her books began in South Africa, she then moved northwards to The Barrel of a Gun (1970), an incisive and comparative analysis of military coups and governments with particular emphasis on Ghana, Nigeria, and Sudan.�� Ruth was sharply critical of the corruption and selfishness of African elites: African development has been held to ransom by the emergence of a new, privileged African class. ���It grows through politics, under party systems, under military governments, from the ranks of business, and from the corporate elites that run the state, the army and the civil service.��� The book is still a classic study of the military in politics and the chapter on Nigeria is still one of the finest accounts and analyses of the civil war. She followed this with her wry and insightful account of Muammar Gadaffi���s enigmatic rule in Libya: the Elusive Revolution��(1974). She then wrote a book on Olive Schreiner:, the South African novelist, feminist, abolitionist, and socialist, ���pro-Boer��� and anti-imperialist. Can a biographer ���come to dislike her subject the more she writes about her?��� Ruth once asked me.

Ruth joined the Department of Sociology at Durham University in 1973 where she was an inspiring and demanding teacher. A term at the University of Dar es Salaam in 1975 turned out to been disappointing, after her initial ���elation���: ���All of them, radicals included, are within a year or two of being turned into bureaucrats. Technocracy rides the waves here, as elsewhere,��� she wrote to me in a letter from from Dar es Salaam in 1975. In 1979, she took on the Directorship of Research in the Centre of African Studies at the Eduardo Mondlane University in Maputo.

The ambitious plan of the Centre was to combine teaching, research, and practice to ���make social research an acceptable step in the making and acceptance of policy.��� The Development course which she established had a significant impact. Ruth edited the first three issues of Estudos Mo��ambicanos with Aquino de Bragan��a, the Director of the Centre. She and her colleagues directed several large field studies on relations between agriculture and the state.��She now had the chance to carry out the research on mine workers from the Mocambican side of the border, which led to the posthumous publication of Black Gold: the Mozambican Miner (1983). The final edition was a collective project which combined text with photographs and workers��� songs. In contrast to the assumptions which underpinned Ruth���s research in the 1950s, researchers found that mine waged fueled a dynamic rural economy ���Mine wages were used to purchase sewing machines, and carpentry, and building tools, and the proceeds of mine work purchased the finished products from this sector. Mine wages were needed to ensure the reproduction of the peasant sector; and the peasant economy in turn reproduced successive generations of mine workers.���

Ruth had to find a way between the political line and policy objectives of Frelimo and creating an environment for critical teaching and the protection of space for independent research on practical questions.��Her style and academic politics could often be intimidating and did not always win approval. As Dan O���Meara, then a South African researcher at the center, said (quoted by Alan Weider in Ruth First and Joe Slovo in the War Against Apartheid),�����We would discuss everything and once the leadership decided anything, that was it. Ruth was the leadership.���

At its Third Congress (in 1977), the now governing FRELIMO declared itself to be a Marxist-Leninist Party, which it was ���quite capable of being,��� Ruth commented, whereas Socialism, ���had always proved a more difficult problem.��� In the 1950s, after returning from international conferences, Ruth had publicized her experiences in China and the Soviet Union, enthusiasm which was tempered when the Soviet Union reconquered Hungary. Hilda Bernstein once told me that in 1967, neither she nor Ruth accepted the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet tanks. Their husbands, Joe Slovo and Rusty Bernstein followed the Soviet line. Ruth and Hilda did not state their positions, at least in public; it would have meant exclusion from the ANC and, for Ruth, her continued membership of the SACP, which Joe protected. When Ruth arrived in Durham in 1973 she said to me: ���I am not a communist,��� surprised that I should have thought that she was. She disagreed publicly with SACP (and Soviet) policies on Eritrea and on Zimbabwe (she was hissed loudly at a meeting of the Anti-Apartheid Movement for questioning the AAM line), but wrote to me in 1982 that while she disagreed, of course, with the international policy of the SACP, it protected the ANC from African nationalism.

Immediately after her death, her fellow editors at the Review of African Political Economy, published a short statement (Vol. 9, No. 23, 1). We wrote: ���Ruth would not wish us to claim some special victim���s privilege for her as white, a woman, an intellectual and a writer of some distinction. Nor do we do so.��� And yet, her death mattered terribly to us all: ���We can hardly believe she is dead for we remember her sharpness of intellect, her trenchant comments at our meetings, her dedication to constructing a relevant political theory and practice, and the warmth and humor of her personal relationships with us. It���s a terrible blow, one from which those who knew Ruth and worked with her in South Africa, in anti-apartheid work, on the Review, and recently in Mozambique will find it hard to ever recover.���

Rosa Williams assisted in preparing this post.

August 16, 2019

Cake politics

Screenshot from the "Stronger Together" TV advert.

Before the All Blacks-Springbok match in Wellington on Saturday, July 27th, a Checkers supermarket in Cape Town displayed two cakes. One was frosted in black with the familiar silver fern of New Zealand Rugby���s All Blacks. The other had the green and gold with the contested Springbok logo, but instead of reading ���Springboks��� the baker wrote ���Quota Squad,��� the clear implication being that the Springbok selection process was politicized and black players were being selected because of a (nonexistent) political quota.

The accusation itself, so often heard by white rugby fans (and held by some in the media), so infrequently legitimate, was even more absurd in the context of the 2019 Springboks.

The cake predictably caused a furor. But like most furors in our Twitter-fueled world it largely faded. Checkers apologized. An unnamed baker���s head may or may not have rolled. The Boks and All Blacks played to a 16-16 draw. Two weeks later, South Africa smashed Argentina in Salta to win The Rugby Championship, the first time the Boks had won the vaunted southern hemisphere championship in ten years, since then-coach Peter De Villiers��� Boks had won the Tri-Nations in 2009.

With all due respect to the Six Nations, The Rugby Championship is by far the most significant, highest quality international tournament every year when a World Cup is not played.��Want numbers using World Cup experiences as a rough proxy for relative hemispheric��domination? There have been eight IRB World Cups. Southern Hemisphere nations have won seven. In the eight World Cups there have been six-teen finalists. Ten have come from the Southern hemisphere powers, six from Six Nations, despite there being fifty percent more of the European teams. There have been thirty-two semi-finalists. Nineteen have come from SANZAAR, thirteen from Six Nations countries. There has never been a Cup when fewer than two southern hemisphere nations qualified for the semis. There has never been a year when more than two European countries qualified for the semis. In 1999 all three of the then-SANZAR nations qualified for the semis; in 2011 all four Rugby Championship teams qualified for the four semifinal spots. Three of the four Rugby Championship nations (and all three Tri-Nations participants) have won at least two World Cups. None of this takes into account head-to-head matches between the Southern Hemisphere teams and their Northern Hemisphere counterparts, where the Southern Hemisphere has been even more dominant. (South Africa, for example, is 96-36-3 against the Six Nations teams since their return from isolation and has a comfortably-to-overwhelmingly winning record against all six.) To say the Southern Hemisphere tournament is better with fewer teams is not merely uncontroversial. It���s silly to even consider the question.

But in World Cup years, The Rugby Championship, because of when it is played, is a shadow of its usual self. Where Six Nations, played in the first months of the year far from the World Cup, maintains its structure, status, and quality during World Cup years, the Championship is a truncated shadow of its usual self. The teams are the same and the quality is unquestionable. But by July and August, New Zealand, South Africa, and Australia are very much interested in adding to their tally of world championships and Argentina is itching to join their ranks.

So it is in 2019. The Rugby Championship has already wrapped, because this year, as is typical for World Cup seasons, the traditional home-and-home setup where each team plays six games was scrapped for one-off matches where luck of the draw determined location and each team played the other only once. This year the Springboks and Australia���s Wallabies opened the competition in Johannesburg on July 20th, with the South Africans earning a bonus point win at Ellis Park where later that night (South Africa time) New Zealand defeated the Pumas in Argentina. The next week South Africa traveled to play their blood rivals, New Zealand, in Wellington where the titans fought to that draw that sure felt like a Bok win, while Argentina visited Brisbane and lost to their hosts in a close contest. The Championship closed out on August 10 with the Boks crushing Argentina to win the Championship after Australia had racked up a record number of points in defeating New Zealand. The All Blacks had gone down to 14 men after a red card in a Bledisloe Cup clash at Eden Park in Auckland earlier in the day and from that point on Australia cruised to a victory.

Let there be no mistake���all four countries wanted to win the Championship. But 2019 will not be assessed, especially for New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa, based on who won The Rugby Championship. And since no team has ever won the Championship/Tri-Nations and also the World Cup, it is even more clear that the focus for the Championship was on how events will play out in Japan, not how they have played out across the SANZAAR landscape in July and August. That said, when the final whistle blew, the South Africans were dancing and singing on the trophy presentation stage. Winning that title this year did not mean everything. It does not follow that it meant nothing.

Thus the peculiarities of the 2019 Rugby Championship… and also the latest in an endless line of allegedly politics-fueled selection decisions by Bok management.

So, back to cake-gate and quota talk.

Initially Springbok coach Rassie Erasmus effectively created two Springbok squads. One group faced off against Australia. It would be unfair (and frankly ridiculous) to call that squad a B-side, as some tried to do in the week leading up to the contest. After all, any Springbok side with Beast Mtawarira, Lood de Jager, Eben Etzebeth, Elton Jantjies, Jesse Kriel, Francois Louw, and Peter-Steph du Toit in it is no B-side, and some of the younger and less experienced players seemed ready to make a leap forward. And while the Boks blooded three new caps in starters Herschel Jantjies and Rynhardt Elstadt, with Lizo Gqoboka earning his first cap off the bench, well, there have been plenty of great Springbok A-teams with debutantes in the lineup. And Herschel Jantjies has proven to be nothing shy of a revelation in his first two matches in green and gold and certainly has sealed his trip to Japan. It is also worth noting that this so-called B-side had eight black players in the starting lineup, making accusations of it being a ���B-side��� all the more problematic, and, in light of the comfortable win over Australia, mildly ridiculous.

The other squad settled down in New Zealand to acclimate beforehand for the clash against the All Blacks. After the Australia game a further group of players and staff flew out almost immediately (as soon as Rassie Erasmus could get away from the press conference) with yet another contingent that departed on Sunday. It was clear that both teams still definitely wanted to win even if the match was not their long-range priority for 2019. The two teams will meet up in the second match of the World Cup in Japan where the two giants of world rugby are in the same pool and neither wanted to yield psychological advantage to the other. South Africa had perhaps more to prove as the country���s national team continues to recover from the depths they hit in 2016-2017. Thus, the draw in Wellington was a positive result for the Springboks but served merely as an appetizer to the September 21st meeting in Yokohama, with neither team gaining any sort of advantage, concrete or intangible, at the Cake Tin last week.

By the third match in Argentina most of the talk of ���A��� and ���B��� squads had faded. It was clear that Erasmus and his staff were in search of combinations, were getting a penultimate look at his options (The Springboks play another match against Argentina at Loftus Versfeld Stadium in Pretoria this Saturday) and are trying to figure out which 31 players to take to Japan. The health of the Captain, flanker Siya Kolisi, and wing Aphiwe Dyantyi are in question, but otherwise the decisions are to be made on talent.

And this is the key factor.

For going on thirty years now white accusers have levied the charge of ���quotas,��� of ���politics��� every time black players are chosen, whenever a black coach is hired (or considered). Yet these accusers are often far more politically driven than those they accuse. Springbok rugby���rugby in the country generally���has been accused of falling short on ���transformation,��� the effort to make the sport representative of the population. And rightfully so���the Springboks and the green-and-gold, a long contested symbol long embodied white supremacy and Afrikaner nationalism.�� There is a long way to go, and in any case the idea that rugby transformation will have a powerful effect on the country is a hoary overstatement borne of naivet�� and romanticization of a sport that means little for vast swathes of the South African population no matter the cultural presence of the Springboks in the elite media and popular culture where whites (still the group that most passionately supports Springbok rugby in particular) still hold disproportionate sway.

Yet the reality is that the Springboks, because of the pressure brought to bear on them from the government and elsewhere, have actually done a better job of bringing in black players than maybe they have been given credit for. The main reason for this is less virtue than it is the simple reality that the Springboks want and need to win. To ignore a vast swathe of the population that can help them do so would be suicide. There have always been black rugby players in South Africa, despite a self-serving myth that whites created that ���blacks are not rugby people.��� So-called coloured and African rugby federations survived and sometimes thrived during apartheid. Facing similar pressures to the national setup the elite rugby playing schools are recruiting black students from a young age and in some circles with an eye toward cultivating rugby talent, though these schools remain stubbornly and disproportionately white.

This year���s Springboks will be multiracial unlike no other Springbok World Cup side. They will do a far better job, for example, than the recently heralded South African Proteas Netball team that made the semi-finals of the World Cup and rarely had more than two black players on the court at any one time.

And the key to the Springboks selection conundrum, and to understanding the absurdity of the ���Quota Team��� accusation? I defy any accusers to name one of the potential candidates for this year���s World Cup squad for whom a clear case for their inclusion cannot be made. I defy them to do so, because it cannot be done. That is not to say that every black candidate is a slam-dunk choice. It is not to say that every black player shined at every moment in the Championship, which would be to put a burden on black Springboks that white players do not confront. It is simply to say that this is a deep, talented group of players, not a single one of whom has been or will be chosen for ���political��� reasons. (This discussion also serves to remind us of is just how much talent there is in South African rugby across the color lines. There are certainly issues with an inability to retain players for Super Rugby and Currie Cup in light of the salaries on offer across multiple European leagues and in Japan. But one can also watch the ongoing (and also truncated) Currie Cup and in a fair number of the matches see players with Springbok caps, many of whom have not worn the green and gold for the last time.)

The Springboks have won The Rugby Championship. But mostly that victory serves as a declaration of intent. They���like New Zealand and Australia and at least a handful of the Northern Hemisphere teams���intend to go to Japan to win. And after the last month one can easily imagine Siya Kolisi, the first black Springbok captain who hails from the black rugby heartland of the Eastern Cape, holding the Webb Ellis trophy aloft. That, at least, is something.

August 15, 2019

Architectual resistance

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.

The directions were standard for Accra. About five lines of intricate orientation followed by: ���Then take the first right and at the building site, ask for Emil.�����A friend was hosting a bonding session at her pool for all the contributors to the inaugural ���LIMBO // ACCRA������a collective of artists and architects working to re-imagine public space in Accra. Too late now to question the whiff of unwaged labour in her earlier message: ���If you���re free today and wanna come by and help out then you too are officially involved in the LIMBO project lol.���

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.To even the untrained eye, rampant property development (and abandonment) in Accra is hard to miss. Yet as with global trends, rapid construction does not mean widespread affordable housing. A lack of regulation and arbitrary pricing means those who can afford to build in Ghana exploit the chaos for significant returns. Measuring the scale of the problem is guesswork with reliable data shockingly difficult to find. Despite government and UN intervention to boost housing supply, completed new homes remain unaffordable for average Ghanaians. Across the capital, developers barely hit 60% occupancy in new builds. As one developer put it: ������the prospective homeowner���s budget or affordability is a complete mismatch���that is why there is this big disparity.���

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.Despite the obvious solutions, developers are doing little to provide affordable solutions to house Ghana���s urban poor.

Into the dilapidated dwelling I stepped. The upper floor, sprawling into contact with an orange tree, was crowned with metal rods, spires for the roof that never was. The team���s activity was so infectious that I changed into my swimming trunks to better wade in and help. Emil was sunny and his throaty Danish accent lent a reassuring depth to everything he said. I warmed to his efficiency as he gave me a tour, bringing me up to speed on the installation. The exhibition was opening the next day and only the prominent plastician Serge Attukwei Clottey had filled his space.

Clear blue sky beckoned to us above the naked central staircase. We rose through a hole ringed in iron and concrete lattice. The precarious landing led directly onto a first encounter with Clottey���s installation. His signature yellow plastic containers had been tessellated neatly into the gaps in the walls and popped with artificial cheer against the crumbling concrete. Above, the blue expanse domed in every direction, providing the view that his artwork denied the windows. As dusk settled into the dusty ruin, more contributors floated up through the floor. Dominique, Limbo���s co-founder, arrived by moped and ran through her to-do list before expanding on their vision.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.���It���s a direct challenge to the extractive property market, the system that takes. Land, manpower, resources, community space. These unfinished properties are everywhere just trapping it all as frozen capital and that���s why we called it Limbo. What���s all this negative space doing to people���s minds?���

This attitude of taking and making for yourself was the blueprint for Limbo���s architectural exercise in resistance. As we parted that evening, I wondered what lessons Accra���s art consumers would take from this sprawling offering.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.Exhibition day arrived and I hung back, capturing peoples��� interaction with the space. Nene, a whizkid designer who was bunking his third day of class filmed alongside me. First came the group of artists, offering their points of view amidst pointless walls. A stray iron girder became a crutch to hang Patrick Tagoe-Turkson���s rubber tapestry. His hefty patchworks use discarded chalewote (flip-flops) and evoke Kente, pixels and pollution. One also served the double function of blocking a large archway over a steep drop. Guests would have to venture deep into the space to discover David Alabo���s afro-surrealist works, spectrums of technicolor and shade peeking out from unfinished en-suites. Diego Asamoa���s photographs of shrouded models in motion were uncanny reminders of life frozen still. The final room upstairs had been earmarked for Free The Youth. The liberated lads burst into the event a fashionably late rocking their graphic laden garms. Throughout the night guests ducked into their leafy photo booth to be snapped in front of a large Ghana flag.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.Next came the public who were greeted with a blue van parked across the entryway by Nana Osei Kwadwo. Nana had installed a Trotro (Ghana���s most common mode of transport), complete with driver, the shrill call of his mate and a TV playing his films on Trotro life. Behind the van, Deryk Bempah���s quieter monochrome works invited guests inside. Bempah���s award winning photojournalism resurrects Ghana���s defunct national rail network. The tracks and stations now stand ossified, relics from the postcolonial era of infrastructure investment. Cramped as they were, it was a rare chance for the urban audience to inspect those fossils up close.

As my shutter clicked away, I watched Accra���s creatives and her misfits, her excluded and most privileged rub shoulders beneath the baking sun. It had cost them nothing to bask in an open space filled with a world of music and political art. If the government is serious about empowering young people through the creative arts, then providing spaces that encourage creativity is the best start. Why not transform abandoned properties as evidence for a transformation in policy?

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.

Image credit Anthony Comber-Badu.The crowd grew thicker as evening approached. Harmattan Rain who���d provided an eclectic ambience for the day upped the BPM and pushed the crowd towards the whiskey bar. Adjoa Armah perched regally on a stool as she drew them round. She delivered a monologue on existing between alienation and familiarity since her move ���back��� to Accra. Each forceful line began ���Home is������ and she spoke beyond the audience that arced around her. She spoke for me and the disaffected youth of the diaspora, turning back towards Africa to find the best way forward. For the free youth of Ghana, unshackled from reliance on their inert elected officials. For young artists with too few public spaces to wonder and grow in together. For young collaborators spreading a message of resistance. For a global generation facing extinction as a firm possibility. For all these potential people, she spoke the truth���our home is a place that has long been in limbo.

There is no Africa in African studies

Duke Humfrey's Library Oxford, UK. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

There is no Africa in African Studies. This has become apparent with the year we spent studying the continent in London. We are an intersectional group of African women who are on a search for a deeper understanding of Africa but continue to find ourselves in echo chambers of white noise. We share our experiences with the hopes that it will encourage and add to the global campaign to decolonize university curricula and cultures.

African Studies has a contested origin story ranging from Black liberation and civil rights campaigns to the advancement of colonial and neocolonial agendas. For example, at its founding the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), according to its own press release, ���immediately became integral in training British administrators and colonial officials for overseas postings across the British Empire.���

The dubious beginnings of African Studies means that the absence of Africa in our British program should not have come as a surprise. The first class of our core African Studies module at the University College London (UCL), a Russell Group university, used Europe as a launching pad both theoretically and literally. The class began with ���forgotten��� pre-Victorian Africans from London and France who were skilled in European sport, music, and writing. These people were presented as important because their talents were regarded as extraordinary within European societies; they were the exceptions. Within that same class, Africa was described as the ���other��� and as a land of ���gold and monsters.��� Instead of focusing on the rich history of Africa and its magnitude of innovation, we were asked to think of ���Africa as a reflection of Eurasia,��� and were later told that there is no difference between Western and African theories. This idea is contrary to the work of numerous African scholars. Imagine, wanting to study Africa only to focus on how Africa is represented and seen by white Europeans?

Using European perspectives unquestionably resulted in the same professor informing us that the Portuguese who established a trading port at Arguin, off the coast of Mauritania, did so because they were interested in buying gold, and that it was Africans who encouraged them to accept slaves as goods. However, the Portuguese were already enslaving Africans and were seeking additional labor for their sugar plantations on the island of Madeira. Such historical revision is detrimental to students who may move on to positions in which they repeat what they have learnt and continue to establish and reinforce the cycle of unseeing and mis-seeing Africa.

When European ideas and perspectives of Africa take the spotlight in African Studies, it infuriates us and causes us to deeply question the validity of the degree we are pursuing. We were not given the opportunity to consider how Africans see and perceive themselves until the final day of our class. This is a remnant of the colonial past and an example of how African Studies today remains paternalistic, thus limiting the agency of people and places we seek to learn about.

Diversity of voices

The curriculum of our African Studies master���s course featured a disproportionately large number of cis-white male voices. For example, 87% of the list of key texts in one of the modules (see the program���s website) are white authors. To discuss Africa through the lens of white academics is Eurocentric and needs to change. With such a one-sided education, we risk leaving university without the language to actualize and conceptualize African visions of Africa.

Universities need to ensure their curricula deconstructs the Eurocentric format of studying Africa. Africa should not be studied through the simplistic categorizations of various ���African issues.��� There are nuances and intersections which flow together and silencing alternative voices and representations of Africans throughout the diaspora should not be the norm.