Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 209

July 30, 2019

One way to resist capitalist food production

Agroecological Farmer in Lesotho. Image credit Chris Conz, 2015.

African agricultural innovators have long resisted the technocratic capitalist development model that hinges on market logics and commercial inputs. James Machobane of Lesotho, for instance, developed an intercropping system in the 1950s designed to produce diverse food, protect soil, and empower poor people, especially women. Through calculated husbandry, Machobane���s followers have resisted the violence of colonial land dispossession and the political-economy of monocropping and migrant labor, which continue to damage ecologies and human health.

Machobane���s system exemplifies the multidimensional objectives of agroecology. In short, agroecology is farming that prioritizes food production that utilizes the earth���s resources while not damaging them. It is an approach that works with ecosystems, for instance, to improve soil and plants using manures rather than chemicals. Drawing on deep wells of local and global knowledge and technology, practitioners strive for ecological and human wellbeing and fair markets for their produce. On diverse lands, farmers cultivate community and self-reliance. Through this act, farmers resist capitalist food systems that seek only consumers and dependent wage laborers to produce uniformity, scale, and profit.

Agroecological approaches to transforming food systems must be taken seriously everywhere. While true, the political and ecological fruits of such movements might ripen more evenly when understood within a historical context where farming has been a central, yet partial aspect of African societies. Among other leaders today, the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa and its affiliates deploy agroecology to resist industrialization of agriculture, land grabs, destruction of biodiversity, and climate injustice. Africans are not alone. La Via Campesina, perhaps above all, has asserted itself globally. Yet the public remains misinformed about agriculture and food in the global south.

A recent New York Times article, ���Millennials Make Farming Sexy,��� perpetuates harmful myths about agriculture in Africa. The article reports on how ���agripreneurs��� in Ghana were returning to the land to make money, investing capital that they had earned elsewhere. These Ghanaian men���yes, readers learn little about women���grow snails, grasscutter, and cassava for market. The comment feed ranged from praise for the ���new��� capitalist spirit to another person insisting that Africans were farmers, naturally, and should return to it because ���gold and diamonds were an afterthought until Europeans arrived.���

Not true. Long before colonialism, people of ancient Mali, for example, mined and traded gold and salt. Not only did Africans create non-agricultural products and diverse foods, they produced knowledge, culture, and cities. The same was true of Egypt, Axum, Great Zimbabwe, Asante, and so on. Always, many Africans have worked as artisans, teachers, traders, nurses, doctors, scholars, and more. People knew these professions by name in African languages long before colonialism. It was missionaries and colonials who established the myth that Africans were���at least at their ���stage of development������farmers, herders, and hewers of wood.

These ideas were inseparable from colonial capitalism and assumptions about race. In this view, bad farming, which meant subsistence production, intercropping, shifting cultivation, and extensive grazing, caused poverty. Improved farming, which meant markets, row planting, fertilizers, exotic seeds, and intensive grazing, was the answer. In 20th-century Africa, colonial agricultural departments sought to instill a capitalist ethic by providing technical support, usually to male farmers who already possessed land and capital. Not surprisingly, some Africans profited by producing tobacco in Malawi, coffee in Uganda, cocoa in Ghana. In Apartheid South Africa, education systems aimed to produce farmers and industrious workers. Stick to the land and out of our cities unless you are on labor contract, so the logic went.

Burkinab�� Bounty: Agroecology in Burkina Faso, a film recently reviewed in AIAC, illustrates a local agroecological movement. ���It is only the soil that can make us free,��� explained one male interviewee. This powerful sentiment echoes across time and space but sounds apolitical when isolated from people who do not grow their own food. At the expense of broader appeal, Machobane of Lesotho cared little for political organizing, encouraging followers to ���stick to thy hillock��� while lamenting that educated Africans were ���devoid of the power for work.���

Agroecological movements advance important cultural, political and ecological projects in innovative ways. But it is also worth asking: what can people like the agripreneurs in Ghana and non-farmers everywhere contribute? Afterall, the future health of people and planet, like the past, belongs to everyone. On the verge of a substantial victory, Food Sovereignty Ghana, ���a grassroots food advocacy movement,��� is drawing on expertise from farmers and lawyers to sue their government over the commercialization of genetically modified cowpeas and rice, which they see as impeding their agroecological objectives. Ghana���s supreme court was set to hear the case on July 9. Agripreneurs too, like those producing snails for market, must throw their financial and political weight behind this cause that prioritizes food and health over profit.

In South Africa���s Eastern Cape, local groups have resisted the proposed Xolobeni Mine Sands Project. Central to their platform, they argue that extraction of metals poses an ecological threat to the agricultural systems that sustain their communities. To rebut claims that mining operations would bring economic benefits, local groups have developed their own proposals to strengthen agriculture and promote new ecotourist projects. In this struggle between varied local groups on the one hand, and foreign capital and its allies in South Africa on the other, resistance has and must continue to enlist the would-be titanium miners and local business people as well as farmers.

In the big picture, it should be acknowledged that for many people past and present, farming or even gardening, is not possible, desirable, or necessary. Social dynamism from the past can inform agroecology systems that both respect diverse aspirations of people while acting to completely transform global food systems that currently marginalize and destroy far more than they nourish.

There is a way to resist capitalist food production

Agroecological Farmer in Lesotho. Image credit Chris Conz, 2015.

African agricultural innovators have long resisted the technocratic capitalist development model that hinges on market logics and commercial inputs. James Machobane of Lesotho, for instance, developed an intercropping system in the 1950s designed to produce diverse food, protect soil, and empower poor people, especially women. Through calculated husbandry, Machobane���s followers have resisted the violence of colonial land dispossession and the political-economy of monocropping and migrant labor, which continue to damage ecologies and human health.

Machobane���s system exemplifies the multidimensional objectives of agroecology. In short, agroecology is farming that prioritizes food production that utilizes the earth���s resources while not damaging them. It is an approach that works with ecosystems, for instance, to improve soil and plants using manures rather than chemicals. Drawing on deep wells of local and global knowledge and technology, practitioners strive for ecological and human wellbeing and fair markets for their produce. On diverse lands, farmers cultivate community and self-reliance. Through this act, farmers resist capitalist food systems that seek only consumers and dependent wage laborers to produce uniformity, scale, and profit.

Agroecological approaches to transforming food systems must be taken seriously everywhere. While true, the political and ecological fruits of such movements might ripen more evenly when understood within a historical context where farming has been a central, yet partial aspect of African societies. Among other leaders today, the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa and its affiliates deploy agroecology to resist industrialization of agriculture, land grabs, destruction of biodiversity, and climate injustice. Africans are not alone. La Via Campesina, perhaps above all, has asserted itself globally. Yet the public remains misinformed about agriculture and food in the global south.

A recent New York Times article, ���Millennials Make Farming Sexy,��� perpetuates harmful myths about agriculture in Africa. The article reports on how ���agripreneurs��� in Ghana were returning to the land to make money, investing capital that they had earned elsewhere. These Ghanaian men���yes, readers learn little about women���grow snails, grasscutter, and cassava for market. The comment feed ranged from praise for the ���new��� capitalist spirit to another person insisting that Africans were farmers, naturally, and should return to it because ���gold and diamonds were an afterthought until Europeans arrived.���

Not true. Long before colonialism, people of ancient Mali, for example, mined and traded gold and salt. Not only did Africans create non-agricultural products and diverse foods, they produced knowledge, culture, and cities. The same was true of Egypt, Axum, Great Zimbabwe, Asante, and so on. Always, many Africans have worked as artisans, teachers, traders, nurses, doctors, scholars, and more. People knew these professions by name in African languages long before colonialism. It was missionaries and colonials who established the myth that Africans were���at least at their ���stage of development������farmers, herders, and hewers of wood.

These ideas were inseparable from colonial capitalism and assumptions about race. In this view, bad farming, which meant subsistence production, intercropping, shifting cultivation, and extensive grazing, caused poverty. Improved farming, which meant markets, row planting, fertilizers, exotic seeds, and intensive grazing, was the answer. In 20th-century Africa, colonial agricultural departments sought to instill a capitalist ethic by providing technical support, usually to male farmers who already possessed land and capital. Not surprisingly, some Africans profited by producing tobacco in Malawi, coffee in Uganda, cocoa in Ghana. In Apartheid South Africa, education systems aimed to produce farmers and industrious workers. Stick to the land and out of our cities unless you are on labor contract, so the logic went.

Burkinab�� Bounty: Agroecology in Burkina Faso, a film recently reviewed in AIAC, illustrates a local agroecological movement. ���It is only the soil that can make us free,��� explained one male interviewee. This powerful sentiment echoes across time and space but sounds apolitical when isolated from people who do not grow their own food. At the expense of broader appeal, Machobane of Lesotho cared little for political organizing, encouraging followers to ���stick to thy hillock��� while lamenting that educated Africans were ���devoid of the power for work.���

Agroecological movements advance important cultural, political and ecological projects in innovative ways. But it is also worth asking: what can people like the agripreneurs in Ghana and non-farmers everywhere contribute? Afterall, the future health of people and planet, like the past, belongs to everyone. On the verge of a substantial victory, Food Sovereignty Ghana, ���a grassroots food advocacy movement,��� is drawing on expertise from farmers and lawyers to sue their government over the commercialization of genetically modified cowpeas and rice, which they see as impeding their agroecological objectives. Ghana���s supreme court was set to hear the case on July 9. Agripreneurs too, like those producing snails for market, must throw their financial and political weight behind this cause that prioritizes food and health over profit.

In South Africa���s Eastern Cape, local groups have resisted the proposed Xolobeni Mine Sands Project. Central to their platform, they argue that extraction of metals poses an ecological threat to the agricultural systems that sustain their communities. To rebut claims that mining operations would bring economic benefits, local groups have developed their own proposals to strengthen agriculture and promote new ecotourist projects. In this struggle between varied local groups on the one hand, and foreign capital and its allies in South Africa on the other, resistance has and must continue to enlist the would-be titanium miners and local business people as well as farmers.

In the big picture, it should be acknowledged that for many people past and present, farming or even gardening, is not possible, desirable, or necessary. Social dynamism from the past can inform agroecology systems that both respect diverse aspirations of people while acting to completely transform global food systems that currently marginalize and destroy far more than they nourish.

The power of African women’s bodily practices

Image via author.

Every year, the African-style clothes of female scholars of African descent paint the vibe and air of the annual meeting of the US-based African Studies Association (ASA), from the boubou, a traditional West African women���s robe, to the tobe, the Sudanese traditional dress. Women plan outfits weeks or months ahead. Many have the garments made in their respective countries, either traveling across the Atlantic with the attire themselves, or having visiting relatives or even neighbors, from back ���home,��� carry the clothing or fabric to them. ���Your aunt sent this for you,��� a neighbor from childhood might say, presenting a package, wrapped in familiar plastic.

Ablaze with colorful fabric, such as Akwete, Kanga, Kente and Shweshwe, the vibrant dynamics of women���s clothing practices also unfold in more intimate spaces within the conference, in moments of exchange. Here, women���as friends, colleagues, mentors���knit small gatherings, admiring one another���s latest attire. Friends ask permission to touch the material they find attractive, delicately feeling the fabric, inquiring about its origins. Stories unfold about visits back ���home������gifts of cloth, latest styles observed at social gatherings. Discreetly, some exchange gifts���fabric, adornments.

Friends pose for photographs to show to the architects of their ensembles, seamstresses (most are women) who may live in the United States or on the African continent, to show their gratitude, solidarity, and pride. The seamstresses will show the photos on their own cellphones to (potential) clients. Similar dynamics take place at parties, burials, church services, meetings of local US-based African cultural associations, and important public events. Women play key roles in facilitating and preserving cultural traditions and norms in many of these spaces, affirming cultural linkages to the African continent through visual bodily aesthetics, drawing from local and global ideas about African fashion trends, cosmetic rituals, and other bodily performances. Women���s bodily practices matter in potent and tangible ways, in hidden unconscious ways that continually shape the lives of women of African descent in the diaspora and on the continent.

Women attend a Women���s Caucus event at the African Studies Association meeting in Georgia, Atlanta. December 1, 2018.��Bidget Teboh,��Oy��r��nk����� Oy��w��m��, the author��and��J. Jarpa Dawuni.

Women attend a Women���s Caucus event at the African Studies Association meeting in Georgia, Atlanta. December 1, 2018.��Bidget Teboh,��Oy��r��nk����� Oy��w��m��, the author��and��J. Jarpa Dawuni.Women on the continent, like their diasporic counterparts, frequently (re)negotiate bodily practices in diverse spaces, expressing various forms of agency and ideas about aesthetic rituals that navigate cultural and national boundaries. They play a key role as ���authentic voices,��� or ���true representatives��� of their respective cultures, communities, and nations. Consequently, women���s daily actions carry weight for the preservation of ���true��� African cultural ideals, the concerns resonating on a larger scale, socially, politically and economically. Thus, women���s bodily practices, such as clothing choice, often prompt surveillance in largely patriarchal communities and societies. Previous AIAC contributors have examined how African women���s varied body rituals, and beauty ideals, have stirred anxiety and provoked intense scrutiny: from how (black) African women���s hair is policed from a young age in homes and schools in South Africa, to public surveillance of women���s clothing practices in Morocco and Kenya.

Yet, as a recent issue of African Studies Review (which happens to be the official journal of the ASA) illustrates, women of African descent continue to express agency and pleasure in shaping their own ideas about varied bodily practices, and thus modeling varied identities in diverse spaces.

For example, and going back in time, newspaper advice columns by and for women in English-speaking regions of Cameroon from the 1960s exemplified women���s attention to and pleasure in what was called in the local colloquial term nyanga���beauty and stylishness. As I discuss in an article in the African Studies Review, in their advice columns female journalists documented how women exercised agency through bodily and clothing practices. However, the journalists also sought to regulate such bodily practices in their columns by striving to define the parameters of ���natural,��� or ���authentic,��� black/African beauty ideals.

In contemporary Nigeria, as Oluwakemi Balogun outlines, beauty pageant contestants and other stakeholders in Nigerian beauty pageants undertake similar negotiations between varied ideas of Nigerian nationalism and contesting cultural ideas, particularly around the question of bikini-wearing. Personal, domestic, and international frames about women���s bodies determine these discussions of embodied respectability at two contemporary national beauty contests in Nigeria.

Meanwhile, online, Sudanese women and girls discuss cosmetic and bodily practices in female-only Facebook groups, sharing advice to sculpt their bodies and even their voices to conform to aesthetic ideals. In Niger, women bring their understanding of childbirth to constructions of their postpartum bodies and the significance of the placenta and umbilical cord. Hausa, Zerma, Tuareg and Fulani women in Niger engage in ritualized practices that reflect their understanding of childbirth, the shaping of birthing practices in urban and ethnic interaction, and their understanding and experiences of medical practices. And in Mauritania, women have long worn the mala���fa, a veil that creates certain everyday constraints and possibilities.

These examples are only snapshots of the numerous ways in which African women all over the continent and the diaspora have reimagined bodily practices in aesthetic rituals in vibrant and imaginative ways.

July 29, 2019

Like family

Like Family book cover artwork.

Shortly after their arrival at the Cape in 1652, Maria and Jan van Riebeeck, the Dutch ���founding father��� of South Africa, employed a young Khoi girl to take care of their children. Krotoa learnt to speak Dutch fluently, and Van Riebeeck realized she could act as an interpreter during bartering expeditions and negotiations with the local people. Not simply a pawn in Van Riebeeck���s strategy on behalf of the Dutch East Indies Company to gain the upper hand at the Cape, Krotoa also had agency. Her position as both the first black nanny to work for a white family at the Cape and an important go-between figure, made me realize that the millions of black women who have worked in white households through the centuries since then are in their own ways also intermediaries, pivotal figures in the interracial South African contact zone. Like Krotoa, they are “outsiders within”; people with an exceptional knowledge of both black and white cultures.

The liberal social and economic historian CW de Kiewiet had already suggested in 1957 that the deepest truth about South Africa lies in the realization that the continued demand for land by white people was the cause of the entanglement between black and white which lead to exploitation and hostility. Parallel to this hunger for land ran the need for workers. “Precisely as this dependency grew, so whites tried to preserve their difference through ideology���racism.” Black people became landless and extremely poor, which led to even greater mutual involvement and interdependence. The migration of black women to cities and the work they did in the private spaces of white households led to a special kind of entanglement, and, in particular, to the racist assumption by even the youngest white child that black hands do the dirty work. The relationship between black domestic workers and white families over generations has inevitably led to patterns of decorum and behavior which convey much of the historically-grown entanglement between black and white.

The lives of practically all South Africans have been touched by the institution of paid domestic work: either because of the presence of an often motherly carer and cleaner, or by the absence of a mother who does paid housework for others. A complicated image of entanglement is therefore held in the collective South African memory, and during the past couple of years research has shown that white people often construct their memories of apartheid around domestic workers, realizing that the “learning” of white dominance hinged on their contact with black women in the home.

My new book, Like Family: Domestic Workers in South African History and Literature (published by Wits University Press) is an investigation into the complex role and meaning of domestic workers in South African communities and literature. It argues that the intercultural contact zone of “maid & madam” relations is an important source by way of which an insight can be gained in the history of everyday interactions between black and white South Africans.

Like Family is a blend of sociology, history and literary analysis of an array of fictional and nonfictional stories. These are situated in Cape Town, Pretoria, Durban and Bloemfontein, though most are set in Johannesburg, with its unique migrant history. In a sense, the book may be regarded as a biography of domestic workers, and, without suggesting that there is a direct correspondence between “servants of art and those of life,”��Like Family is meant to be a form of archival restitution.

In the first chapters of Like Family, information from life stories collected mainly by welfare and activist organizations and autobiographical work is combined with an overview of the historical and sociological development of labor relations in South Africa. Autobiographies of authors such as Es���kia Mphahlele and Sindiwe Magona are analyzed against the background of these demographical and political factors.

The second half of the book concentrates on literary representations of domestic worker characters, focusing on urban situations where the pass laws impacted extremely harshly on the lives of black people migrating to cities. Millions of lives of black women remain undocumented, but for every literary figure in a novel, song or poem over the centuries, some “real” woman was the inspiration and model. In some such stories domestic workers take a central role, but in many more even their brief and seemingly incidental appearances in “supporting roles,” whether opening doors or carrying trays, are insightful and often distressing. When reading these stories, Stuart Hall���s concept of the “circuit of culture,” the cycle of representation needs always to be taken into account: the way in which domestic workers are described influences the behavior of readers.

In Like Family, practically all the autobiographical narratives, short stories, novels, plays and poems that are discussed focus on the issue of borders, whether these were formally��constructed by laws, or whether they relate to informal patterns of behavior and conventions, some of which have persisted since the times of slavery. Any story which deals with the issue may be told in such a way that it perpetuates stereotypes, or in a manner that results in a questioning of an entangled set-up. While it is possible that a “contact” is mutually beneficial, any benevolence on the part of the employer is inevitably entwined with paternalism, and therefore remains problematic.

The approach in this book has been to foreground the personal in the political sphere: the focus therefore falls on individuals such as Krotoa and a few enslaved women who had gained entry into the historical archive, as well as the Sophies, Evelina���s and Flora���s who are to be found in literary work by authors such as Andr�� Brink, J.M. Coetzee,�� Imraan Coovadia, Nadine Gordimer, Elsa Joubert, Antjie Krog, Sindiwe Magona, Zakes Mda, Es���kia Mphahlele, Sisonke Msimang, Zukiswa Wanner, Ingrid Winterbach and Zo�� Wicomb. Like Family uncovers wry and subversive insights into South African society, capturing paradoxes relating to shifting power relationships.

This is an edited extract from the introduction to��Like Family: Domestic Workers in South African History and Literature��(Wits University Press 2019).

The South of Algeria has something to say

Image credit Joan Vila via Flickr (CC).

The massive protests in Algeria that began in late February 2019 have clearly shaken the core of political institutions in the country. While media focus, both by journalists and on social media, has been on northern Algeria, strikes and protests in Algeria���s oil-rich south have been occurring for decades.

A large swathe of the rural population in Algeria���s massive Saharan south continues to live in economic precarity. While the national unemployment rate in Algeria is estimated at 20 percent, ���many living in the Sahara say that the true rate is close to 50 percent in their region.���

The Sahara comprises over 85% of Algeria���s territory, yet it is populated by less than 10% of the population. It is also ethnically diverse, composed of Amazigh confederations, such as Mozabites of the northern Sahara and Kel Ajjer Tuareg of the southern Sahara, and nomadic Arab tribes.

Saharan inhabitants have been protesting regularly since the 1970s because they feel alienated from an elite ruling class in the north who do not understand the south���s unique needs, shaped by the challenging natural elements and relative isolation of the Sahara. The region���s oil wealth further contrasts with the government���s structural neglect of its inhabitants. The neglect of the south also reflects larger tensions over identity and politics in Algeria.

In February 2016, a group of unemployed men from the southern province of Ouargla sewed their mouths shut, cut their arms and chests with sharp razors and placed nooses around their necks in a public protest against worsening unemployment in the Sahara. The protest, combined with weeks of sit-ins and hunger strikes, failed to garner the attention of officials. Earlier, in 2015, the residents of Ain Salah, an oasis town in the southern province of Tamanrasset, protested against government plans to drill for shale gas nearby. The anti-shale gas movement, called Soumoud, cited environmental concerns as reasons for their protests that rapidly spread across Tamanrasset. Following the onset of the February 2019 protests across northern cities, industrial and wildcat strikes took place across the south, crippling Sonatrach, the country���s national oil and gas company, and demonstrating how political sentiment in the north remains tightly connected to that of the south.

Protests in the Algerian Sahara express differing political demands but they reflect shared concerns regarding the worsening inequalities plaguing the country. Some protests (such as the anti-shale movement) rapidly gain traction, while others (such as the Ouargla protest) lack organized structure and die down as quickly as they emerge. Some demonstrations (such as the 2019 protests) are large-scale and demand the dismantling of the existing political system, while others (such as the intermittent protests in the south) are smaller-scale and swiftly placated by the state through oil money. Payoffs, subsidies and wage increases channeled to the south are no more than temporary fixes that hide the shrinking of the social welfare infrastructure, leaving Saharan residents in constant health precarity and socio-economic neglect. Such a strategy serves to preserve the elite���s oil interests in the region, enriching regime loyalists, Sonatrach oligarchs and business tycoons at the expense of rural and proletarian Algerians.

In particular, the province of Ghardaia, situated in central-southern Algeria in the M���zab region of the Sahara, reveals how relations between Saharan communities are impacted by the region���s oil wealth. Ghardaia has witnessed sporadic intercommunal clashes since the 1970s between two groups native to the Sahara: Mozabites (an Ibadi Amazigh community) and the Chaamba (a Maliki Arab tribe). Amazigh refers to the heterogenous ethnic groups indigenous to north-western Africa. As Hamza Hamouchene notes, most Algerians are Arabized Amazigh. Algerians who maintain deep ties to Amazigh identity, such as the Kabyles of the north, often identify strongly with local Amazigh cultures and speak regional Tamazight languages. Due to the spread of Islam, migration and pro-Arabization government policies during Algeria���s history, Arab culture and Arabic are also seen as integral to Algerian national identity. Whether one identifies Amazigh, Arab or otherwise, however, remains largely a matter of personal or political choice���a complex product of one���s familial upbringing, regional location and individual circumstance.

The Mozabite-Chaamba conflict in Ghardaia is reflective of how existing national anxieties regarding Amazigh and Arab identity are further exacerbated by the politics of natural resources. Since the discovery of oil in the 1950s, Ghardaia has experienced an influx of job-seekers from across Algeria and the presence of international oil companies to construct Ghardaia���s petroleum infrastructure. The discovery of oil, however, did not bring about economic development for the region, as jobs remained scarce for locals and the social welfare infrastructure left under-developed.

Mozabite-Chaamba tensions in Ghardaia occur due to contestations over limited resources, jobs and land. Tensions date back as early as 1975, when the first clashes occurred, and has continued with intermittent, small-scale violence in Beni Isguene, Berriane and Guerrara. In 2008, violence broke out in Berriane and caused two deaths. In May 2013, it was alleged that Chaamba Arabs forged property documents to seize control of a Mozabite cemetery, leading to the burning of shops and vehicles and physical altercations between sword-wielding youth gangs. Later that year, Mozabite cemeteries and mausoleums were desecrated in Ghardaia, with the tomb of Amir Moussa, a sixteenth-century Mozabite Amazigh leader, destroyed in the process���the tomb is designated a UNESCO World Heritage. Mozabite residents claimed that the Gendarmerie Nationale, the Algerian rural police force, had sided with the Chaamba and did nothing to protect Mozabite property.

Accounts of the conflict���s causes vary. Some view it as an ethnocultural conflict���Mozabites are Ibadi Amazigh Muslims (Ibadism being a distinct school of Islam that is neither Sunni nor Shi���a) while the Chaamba are nomadic Arabs who adhere to the Maliki ma���hab of Sunni Islam. Mozabites demand the recognition of Mozabite claims to land, framing their protests as part of preserving the region���s Amazigh identity against the incursion of a “foreign” Arab influence, despite the fact that the Chaamba are Saharan nomads native to the region. Conversely, the Chaamba view security forces and the state as unfairly favoring the Mozabites and demand equitable access to resources.

Each group articulates specific ethnocultural claims to land, resources and jobs as part of a broader project implicating the state. Other accounts point to how Mozabites and the Chaamba have co-existed peacefully for centuries; tensions only emerge out of immediate economic grievances. As Dalia Ghanem-Yazbeck notes, ethnocultural divisions are used to frame economic disparities:

The Berbers accuse the Arabs of benefiting from preferential treatment by the government, including obtaining better jobs and places to live, because they are Arabs. Meanwhile, the Arabs accuse the Berbers, who are generally perceived to be wealthier, of hindering poorer Arabs��� integration into their exclusive social structures.

Each group accuses the other of benefiting from the state���s preferential treatment, with property disputes and access to jobs making up the bulk of grievances.

The government views Ghardaia as a security risk to be managed through short-term policies such as boosting the number of security forces in the region, increasing wages and offering compensation to families of victims. Those are solutions revealing the government���s usual practice of collaborating with local institutions to temporarily placate social unrest with oil money, while leaving underlying structural problems, including the province���s alarmingly high youth unemployment rate, unresolved. Algeria���s economy remains overly dependent on oil and gas. Despite the fact that profits have been in decline since the 2011 Arab Spring, energy sales in Algeria compose up to 60 percent of the state budget and constitute 95 percent of the country���s exports, resulting in a rapidly-shrinking labor market where well-paying jobs outside the oil sector are increasingly scarce.

Ghardaia reveals how Saharan communities in Algeria can be rapidly transformed by the exploitation of natural resources, producing economic rivalries and aggravating sectarian divisions either latent or inexistent before. Because oil-rich reserves often sit under lands long-settled or occupied by both sedentary and nomadic communities, the government requires the deepening of sectarian divisions such that indigenous Saharan claims to land can be contested and then claimed under the custody of the state. That is why, in the 1960s, the government encouraged nomadic Saharan Arab tribes to settle permanently in Ghardaia���a policy-driven demographic change contributing to the current state of Mozabite-Chaamba tensions. It was only after sectarian divisions worsened that the Algerian state is able to lay claim to the region���s oil. Indigenous Saharan claims to the land���s resources become forgotten and abandoned as the Mozabites and the Chaamba are instead competing with one another for the scarce resources that remain. The Algerian Sahara���s social dilemmas are therefore a bellwether reflecting a common issue at the core of the protests that erupted in February: how corruption, political kleptocracy and the diversion of wealth to an elite few is not a localized issue but a national phenomenon, impacting the destinies of Algerians across social divisions. A prominent rallying cry, “Yetne7aw ga3!��� (They must all go!), expresses protesters��� complete rejection of the entire political system as it currently stands.

‘The South [of Algeria] has something to say’

Image credit Joan Vila via Flickr (CC).

The massive protests in Algeria that began in late February 2019 have clearly shaken the core of political institutions in the country. While media focus, both by journalists and on social media, has been on northern Algeria, strikes and protests in Algeria���s oil-rich south have been occurring for decades.

A large swathe of the rural population in Algeria���s massive Saharan south continues to live in economic precarity. While the national unemployment rate in Algeria is estimated at 20 percent, ���many living in the Sahara say that the true rate is close to 50 percent in their region.���

The Sahara comprises over 85% of Algeria���s territory, yet it is populated by less than 10% of the population. It is also ethnically diverse, composed of Amazigh confederations, such as Mozabites of the northern Sahara and Kel Ajjer Tuareg of the southern Sahara, and nomadic Arab tribes.

Saharan inhabitants have been protesting regularly since the 1970s because they feel alienated from an elite ruling class in the north who do not understand the south���s unique needs, shaped by the challenging natural elements and relative isolation of the Sahara. The region���s oil wealth further contrasts with the government���s structural neglect of its inhabitants. The neglect of the south also reflects larger tensions over identity and politics in Algeria.

In February 2016, a group of unemployed men from the southern province of Ouargla sewed their mouths shut, cut their arms and chests with sharp razors and placed nooses around their necks in a public protest against worsening unemployment in the Sahara. The protest, combined with weeks of sit-ins and hunger strikes, failed to garner the attention of officials. Earlier, in 2015, the residents of Ain Salah, an oasis town in the southern province of Tamanrasset, protested against government plans to drill for shale gas nearby. The anti-shale gas movement, called Soumoud, cited environmental concerns as reasons for their protests that rapidly spread across Tamanrasset. Following the onset of the February 2019 protests across northern cities, industrial and wildcat strikes took place across the south, crippling Sonatrach, the country���s national oil and gas company, and demonstrating how political sentiment in the north remains tightly connected to that of the south.

Protests in the Algerian Sahara express differing political demands but they reflect shared concerns regarding the worsening inequalities plaguing the country. Some protests (such as the anti-shale movement) rapidly gain traction, while others (such as the Ouargla protest) lack organized structure and die down as quickly as they emerge. Some demonstrations (such as the 2019 protests) are large-scale and demand the dismantling of the existing political system, while others (such as the intermittent protests in the south) are smaller-scale and swiftly placated by the state through oil money. Payoffs, subsidies and wage increases channeled to the south are no more than temporary fixes that hide the shrinking of the social welfare infrastructure, leaving Saharan residents in constant health precarity and socio-economic neglect. Such a strategy serves to preserve the elite���s oil interests in the region, enriching regime loyalists, Sonatrach oligarchs and business tycoons at the expense of rural and proletarian Algerians.

In particular, the province of Ghardaia, situated in central-southern Algeria in the M���zab region of the Sahara, reveals how relations between Saharan communities are impacted by the region���s oil wealth. Ghardaia has witnessed sporadic intercommunal clashes since the 1970s between two groups native to the Sahara: Mozabites (an Ibadi Amazigh community) and the Chaamba (a Maliki Arab tribe). Amazigh refers to the heterogenous ethnic groups indigenous to north-western Africa. As Hamza Hamouchene notes, most Algerians are Arabized Amazigh. Algerians who maintain deep ties to Amazigh identity, such as the Kabyles of the north, often identify strongly with local Amazigh cultures and speak regional Tamazight languages. Due to the spread of Islam, migration and pro-Arabization government policies during Algeria���s history, Arab culture and Arabic are also seen as integral to Algerian national identity. Whether one identifies Amazigh, Arab or otherwise, however, remains largely a matter of personal or political choice���a complex product of one���s familial upbringing, regional location and individual circumstance.

The Mozabite-Chaamba conflict in Ghardaia is reflective of how existing national anxieties regarding Amazigh and Arab identity are further exacerbated by the politics of natural resources. Since the discovery of oil in the 1950s, Ghardaia has experienced an influx of job-seekers from across Algeria and the presence of international oil companies to construct Ghardaia���s petroleum infrastructure. The discovery of oil, however, did not bring about economic development for the region, as jobs remained scarce for locals and the social welfare infrastructure left under-developed.

Mozabite-Chaamba tensions in Ghardaia occur due to contestations over limited resources, jobs and land. Tensions date back as early as 1975, when the first clashes occurred, and has continued with intermittent, small-scale violence in Beni Isguene, Berriane and Guerrara. In 2008, violence broke out in Berriane and caused two deaths. In May 2013, it was alleged that Chaamba Arabs forged property documents to seize control of a Mozabite cemetery, leading to the burning of shops and vehicles and physical altercations between sword-wielding youth gangs. Later that year, Mozabite cemeteries and mausoleums were desecrated in Ghardaia, with the tomb of Amir Moussa, a sixteenth-century Mozabite Amazigh leader, destroyed in the process���the tomb is designated a UNESCO World Heritage. Mozabite residents claimed that the Gendarmerie Nationale, the Algerian rural police force, had sided with the Chaamba and did nothing to protect Mozabite property.

Accounts of the conflict���s causes vary. Some view it as an ethnocultural conflict���Mozabites are Ibadi Amazigh Muslims (Ibadism being a distinct school of Islam that is neither Sunni nor Shi���a) while the Chaamba are nomadic Arabs who adhere to the Maliki ma���hab of Sunni Islam. Mozabites demand the recognition of Mozabite claims to land, framing their protests as part of preserving the region���s Amazigh identity against the incursion of a “foreign” Arab influence, despite the fact that the Chaamba are Saharan nomads native to the region. Conversely, the Chaamba view security forces and the state as unfairly favoring the Mozabites and demand equitable access to resources.

Each group articulates specific ethnocultural claims to land, resources and jobs as part of a broader project implicating the state. Other accounts point to how Mozabites and the Chaamba have co-existed peacefully for centuries; tensions only emerge out of immediate economic grievances. As Dalia Ghanem-Yazbeck notes, ethnocultural divisions are used to frame economic disparities:

The Berbers accuse the Arabs of benefiting from preferential treatment by the government, including obtaining better jobs and places to live, because they are Arabs. Meanwhile, the Arabs accuse the Berbers, who are generally perceived to be wealthier, of hindering poorer Arabs��� integration into their exclusive social structures.

Each group accuses the other of benefiting from the state���s preferential treatment, with property disputes and access to jobs making up the bulk of grievances.

The government views Ghardaia as a security risk to be managed through short-term policies such as boosting the number of security forces in the region, increasing wages and offering compensation to families of victims. Those are solutions revealing the government���s usual practice of collaborating with local institutions to temporarily placate social unrest with oil money, while leaving underlying structural problems, including the province���s alarmingly high youth unemployment rate, unresolved. Algeria���s economy remains overly dependent on oil and gas. Despite the fact that profits have been in decline since the 2011 Arab Spring, energy sales in Algeria compose up to 60 percent of the state budget and constitute 95 percent of the country���s exports, resulting in a rapidly-shrinking labor market where well-paying jobs outside the oil sector are increasingly scarce.

Ghardaia reveals how Saharan communities in Algeria can be rapidly transformed by the exploitation of natural resources, producing economic rivalries and aggravating sectarian divisions either latent or inexistent before. Because oil-rich reserves often sit under lands long-settled or occupied by both sedentary and nomadic communities, the government requires the deepening of sectarian divisions such that indigenous Saharan claims to land can be contested and then claimed under the custody of the state. That is why, in the 1960s, the government encouraged nomadic Saharan Arab tribes to settle permanently in Ghardaia���a policy-driven demographic change contributing to the current state of Mozabite-Chaamba tensions. It was only after sectarian divisions worsened that the Algerian state is able to lay claim to the region���s oil. Indigenous Saharan claims to the land���s resources become forgotten and abandoned as the Mozabites and the Chaamba are instead competing with one another for the scarce resources that remain. The Algerian Sahara���s social dilemmas are therefore a bellwether reflecting a common issue at the core of the protests that erupted in February: how corruption, political kleptocracy and the diversion of wealth to an elite few is not a localized issue but a national phenomenon, impacting the destinies of Algerians across social divisions. A prominent rallying cry, “Yetne7aw ga3!��� (They must all go!), expresses protesters��� complete rejection of the entire political system as it currently stands.

July 28, 2019

Decolonizing Africa’s past

Jubilant crowds listening to the speech of President Nelson Mandela. 10/May/1994. UN photo credit Sattleberger.

��� Antonio Gramsci, ���I Hate New Year���s���They say that chronology is the backbone of history. Fine. But we also need to accept that there are four or five fundamental dates that every good person keeps lodged in their brain, which have played bad tricks on history.

April this year marked the 25th anniversary of the start of the Rwandan genocide (observed on 7 April with Genocide Memorial Day), and South Africa���s first multi-racial democratic election (observed on 27 April with Freedom Day). The Rwandan genocide and the end of apartheid influenced the West���s perception of political violence in Africa and forced questions as to whether a liberal democratic nation-state can defuse ethnic conflict and racial animosity. These dynamics were constructed, historically, as natural social antagonisms that could only be managed through institutions governed by democratic procedures; while the impact of inherited politico-legal identities were minimized.

In South Africa, 1994 initiated changes for the better. It would be misguided to rebuke completely a historical moment where states facilitated the return of land to the dispossessed, allowed families to learn what happened to disappeared relatives, and permitted freedom of movement across the country. But twenty-five years later, after showing the world that the African nation-state can endure, it is unclear what or who has survived.��

Is it a set of institutions and procedures, a mythic people who are redefining inherited identities or those who have survived in spite of rather than because of the 1994 transformation? Before 1994 becomes a ���fundamental date��� or plays ���tricks��� on the link between democracy and colonialism, there is the chance to construct a meaning of this year and highlight the (dis)continuity with the past. A meaning that undermines Africa���s subordinated position within European-defined modernity and privileges alternate historical trajectories that counter the nation-state.

National anniversaries and holidays create spectacular rituals of belonging that remind citizens of their state���s power and longevity. While every state commemorates dates specific to their trajectory; the national holiday/anniversary homogenizes political ritual across the globe and further naturalizes the nation-state as the most dominant and socially ingrained form of political organization. In the African context, national anniversaries also become moments to assess a state���s democratic progress, a chance to measure whether life has fulfilled past expectations about the future. The subtext being how government officials and economic leaders have wielded inherited institutions. But the temporal proximity to African independence makes many outside observers skeptical of the nation-state as a legitimate political form in the continent.�� Such perspectives imply that the state could collapse at any moment, as its historical origins would always be always at odds with the so-called ���traditional��� desires of the (indigenous) people ��� rumors of Afrikaners suffering a white genocide or a Zimbabwe-like land grab in South Africa exemplify such sentiments. And the only antidote to such crises is time. But time in African politics is elusive as there is simultaneously an abundance and shortage of it. Homo sapiens originated in Africa, there were the ancient kingdoms of North Africa and the medieval empires of West and Central Africa and the countless other nomadic and sedentary communities with distinct modes of social organization. Yet liberal democracies still need more time. In time, South Africa will redistribute land or in time, Rwanda will have a different president or in time, country x will accomplish y goals. Even though all nation-states have their legitimacy questioned; African states appear to be held to a different standard, perhaps because in the 20th century the nation-state became similar to Western products designed for export; a commodity to be consumed, or a set of tools to be mastered. But as the legitimacy of Western governments is questioned, there is a chance to decolonize the nation-state, to disrupt its position as the primary site of meaningful politics, practices, and organization.

While decolonial theory disrupts European modernity by illustrating the symbiotic relationship between freedom and unfreedom, #decolonize social movements dismantle the epistemic violence of the colonial era, and its post-independence residues, by calling for the deracialization of socio-cultural spaces. But these discourses are difficult to translate into practical politics, especially in the muddied waters of this current era in which imperially-forged identities are widely embraced, threatening essentialization and obscuring other solidarities. Ultimately, current decolonial discourses are antithetical to the formation and maintenance of the nation-state as they try to reveal the historical consequences of how the exploitation and erasure of the colonized benefited the colonizer. Decolonial theory along with concepts such as biopower, necropolitics, and the dispossessed, have stridently argued that the nation-state���s survival comes from its ability to produce manageable communities, docile citizens, and expendable populations. But there has been a failure of imagination when it comes to understanding the politics that allowed the dispossessed reproduce their lives. Survival is often viewed as the bare minimum of what marginalized communities achieve; given how they are acted upon by the state. But it can also be the ability to create meaningful places and relationships that allow for the reproduction of one���s life and community regardless of a state���s actions, such as Abdu Maliq Simone���s idea of people as infrastructure. Such survival suggests a mode of democracy that eschews history, institutions, and procedures and focuses on the crafting of relationships that relate to one���s survival, indefinitely.�� �� �� �� ��

In South Africa, the renewed displacement of communities from desirable property and the intertwined housing and eviction crisis appear eerily similar to apartheid. Suggesting a continuity between the apartheid and multi-racial democratic states, especially in terms of how marginalized groups are treated, signals the reproduction of the spatialized relationship between capital and labor that constituted apartheid. While the survival of those who are neglected by the state is easily portrayed as new citizens exercising their rights or the continuation of the resistance against apartheid, it obscures the intricacies of how these communities work alongside, outside, or against the nation-state for their survival. By focusing on how these communities survive, rather than how the state compels their docility; we can outline an alter-politics to state policies rather than an anti-politics. Ghassan Hage���s alterpolitics encapsulate those politics of place that articulate alternative modes of political, social, and economic organization and were never fully incorporated into the nation-state. These politics also find continuity with the histories of those communities silenced during their struggles to transform the colonial and apartheid states colonialism. Consider the organization of townships, especially when community members create solutions to the purposeful lack of infrastructure and services; inter-generational and gender dynamics that challenge patriarchy and sexual abuse in the home, school or workplace; or the networks foreign and domestic migrants create to address their needs in new environments. Even though these issues may appear as social or a question of policy rather than politics, these communities are simultaneously addressing historical and contemporary state actions by disrupting socio-political hierarchies that have calcified and current neoliberal policies that curtail their social welfare. In 1994 there was no need to see these communities as outside or in opposition to the nation-state, as they were citizens of a new democracy, which at the time was enough. But as time marches on the survival of these and other communities on their terms transforms their survival into an achievement, rather than an accident, of history. If decolonial discourses are to make an impact in the academic discipline of politics and real-world politics, then it will need to ask different questions about the nation-state; questions that transcend the objective of trying to capture control of the state and envision the survival of those communities that have survived in spite of rather than because of the nation-state.

Pirates and Chiefs

An image of a previous encounter between Pirates vs Chiefs in July 2011. By John Karwoski. Via Flickr CC.

On Saturday, July 28, South Africa���s national rugby team, the Springboks faced off against New Zealand���s All Blacks in a clash with international implications in world rugby. Later that same day, two local football clubs,��Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates faced off in a local preseason derby clash with virtually no implications in world football.

Yet, in South Africa the latter meant significantly more than the former. Part of this is because, despite the Invictus myth that has enveloped the Springboks, rugby is far less significant for South Africans than soccer is. But beyond that there is no questioning it: There is no such thing as an insignificant Orlando Pirates-Kaizer Chiefs match.

Consider this: The Pirates-Chiefs match this Saturday involved a barely disguised money grab couched as a preseason tournament wrapped in a sponsor���s title. Fans got to choose the starting lineups online. In what amounted to a reality show, contestants won the right to be honorary game-day coaches (and wept with legitimate emotions after winning their crown). The match took place days before kickoff of the local Premier Soccer League season, a cutthroat competition unmatched from top-to-bottom in Africa and underrated in the rest of the world. And it gathered 70,000 passionate fans to the Calabash, the FNB Stadium in Soweto that was the symbolic and literal epicenter of the 2010 World Cup in South Africa. This game did not matter. At all. And yet it mattered. Enormously.

To put it another way, Springboks-All Blacks ���matters��� in pure rugby terms. Pirates-Chiefs just simply fucking matters. And the ways that it matters tells us a great deal about sporting cultures in South Africa and perhaps beyond.

There are several components to this. One connects to the disproportionate role that rugby plays in the public dialogue in South Africa, which itself speaks to the predominant whiteness that still dominates the sporting and cultural landscape in South Africa. Another connects to some frankly byzantine politics and history within South African soccer. And a third connects these two points: South Africans take an inordinate pride in the best of South African-ness, whether it be the Springboks, the success of the national netball team, or, the ultimate example of sporting South-African-ness, the Pirates-Chiefs derby.

One: I am as guilty as anyone of propagating the rugby narrative in South Africa. I am an American who has spent more than 22 years traveling to and working in South Africa. I played rugby at Rhodes. I have been writing about the sport for years, shocking press box denizens in South Africa with my accent and my knowledge and passion for South African rugby. I am working on a book on rugby in the apartheid era. And yet let us be clear: Rugby is fractionally as important as its role in the media and popular culture would lead you to believe. Those who love rugby love it unconditionally. Yet Currie Cup (the provincial championship) matches play to empty stadia, and grassroots rugby tends to play out at the elite prep schools that still wield disproportionate influence in South Africa. South African rugby matters because we are told relentlessly, by guys like me, it turns out, that it matters.

Two: Oh dear. If my criticisms of the political status of rugby led you to believe that I was going to be kind to South African soccer, I apologize now. Because the Pirates-Chiefs rivalry is a function of the sort of small-minded, petty, angry, complex, and frankly childish political rivalry that will surprise no one who understands South Africa but will shock anyone who buys into a Mandela-driven mythology of South Africa full stop.

Imagine this: The Orlando Pirates were founded as a football team in Orlando, in the heart of Soweto in 1937, taking a central place among soccer-mad fans in one of the most densely populated and most politically active populations in Sub-Saharan Africa. Chiefs were founded in 1970 as a breakaway club by former Pirate, Kaizer Motaung. (He had borrowed the name and the club crest from Atlanta Chiefs where he played in the late 1960s.) From the start, the rivalry between the two teams dominated local soccer. Motaung and Irvin Khoza, chairman and owner of Pirates, pretty much dictate the rules of South African soccer. Khoza is also vice president of the South African Football Association, which controls local football. Neither Kaizer Chiefs nor Pirates has even dominated local soccer in recent years. That honor goes to Mamelodi Sundowns, who have won the Premier Soccer League title nine times total since the league was established in 1996-97 and are current champions. By comparison Prates and Chiefs have won a total of eight championships in that time, four apiece. And yet in some ways this is a perfect encapsulation of South African politics more broadly. Not one in ten South Africans could differentiate the platforms of the African National Congress and the Democratic Alliance, the country���s main opposition party. Yet they know where they stand in terms of their party loyalty. Similarly, not one in ten South African football fans could differentiate between Pirates and Chiefs when it comes to the roles they play in the politics of the South African Football Association. Yet they know where they stand in terms of party loyalty.

Yet my third observation raises some hope, perhaps. For South Africans are fantastic at performing their preferred image of South African-ness. I was on a media pass for the South Africa-Australia rugby match ten days ago. And in the days before the match Springbok rugby legend James Small and South African music legend Johnny Clegg had passed away. And the pregame show was little more than a performance of the sanitized meaning of bad boy James Small (who was found dead, naked in a strip club) with the rainbow utility of Clegg all blended with the sainted image of Mandela. And even as a cynic of this sort of performative rainbow nonsense I could not help but find my goosebumps raised and my adopted South African pride boosted. (Interestingly, in the prematch festivities for the Chiefs-Pirates match, a minute of silence was held for Small, Clegg and another white footballer player, Mark Batchelor, who had played for both Pirates and Chiefs and who was allegedly gunned down over a drug deal.)

Truth be told though, the New South Africa is to be found, for good and for bad, in FNB Stadium, where corrupt soccer officials broker deals that line the pockets of the few while cynically tossing coins to the many: online player selection! Reality coaching shows! A worthless pre-season cup! All of which just happened to bolster the sponsor, Carling Black Label, one of South Africa���s more prominent beers. Yet 70,000 showed up, painted their faces, donned their makarapas, and few knew or cared about the score of the Springbok match. This is South African sport, for good, for ill, for indifferent.

And none of this matters. The final score was Pirates 2, Amakhozi 0. Saturday night the black and white, the Buccaneers, had bragging rights. The politics, the posturing, and certainly the Springboks were simply irrelevant. They were dancing in Orlando. And millions of South Africans know what that means.

July 26, 2019

Sport, history and politics at the African Cup of Nations

Image credit Bein Sports.

I have been struck lately by how strongly held our ideas about race and nationhood are. That these ideas are socially constructed or artificial���I teach a course on their historical construction in Africa through colonial science���does not mean they are not powerful.

Living in Cairo, I attended the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) finals between Senegal and Algeria. The closing ceremony before the match featured an impressive light and fireworks show with music by Ghanaian Afropop singer Fuse ODG and Egyptian pop diva Donia Samir Ghanem. But was also a preview of racial binaries that would become more apparent once the football started. Algeria won the match 1-0 on Baghdad Bounedjah���s deflected ball in the second minute. A stout Algerian defense prevented the Senegalese, favored by many to win the tournament, from equalizing.

Senegalese fans comprised a relatively small contingent in the 70,000-seat stadium: perhaps a few hundred in comparison to the tens of thousands of Algerian supporters who made the trek from Algeria and France, many on charter flights provided by the Algerian football federation. The rest of the fans came mostly from Egypt. The majority of Egyptian spectators clearly supported Algeria. Why? After all, there has been bad blood between Egyptian and Algerian football fans since at least 1989, when a qualifying match in Cairo for the 1990 World Cup led to attacks on Egyptian fans and an Egyptian coach. Violence between football fans of the two nations erupted again in 2009 in qualifiers for the 2010 World Cup.

Yet the ties of a putative ���Pan-Arab��� identity (in spite of old Egyptian tropes about Algerians as violent and barbaric Berbers) seem to have driven most Egyptian loyalties toward Algeria and away from Senegal. My wife, watching the AFCON final at home on BeIN Sports, noted a similar affinity from the Qatar-based TV channel. The coverage focused on Algerian players and coaches at the expense of the Senegalese: there were few images of the Senegalese team in comparison to the Algerians, and BeIN journalists interviewed mostly Algerian players and coaches before and after the game. The voices of the BeIN commentators became more animated when Algeria had the ball. Taken together, these factors demonstrated a clear bias favoring Algeria. This bias seemed to confirm the binaries of race and nation displayed in the pregame closing ceremony.

Perhaps I should not have been surprised. After all, shortly after my 2017 move to Egypt, a taxi driver told me that the Egyptian national team was getting ready to play against Uganda, ���an African team.��� When I asked him if Egypt was not also in Africa���after all, it was an AFCON qualifying match���he responded, ���Yes, but we Egyptians think of ourselves more as Arab than African.��� After posting on social media that I was ready to watch the AFCON final, an Egyptian friend and colleague responded that ���of course��� she was cheering for Algeria but she hoped that we enjoyed the game. Why ���of course?��� Did it have something to do with an assumed cultural division between ���Arabs��� of North Africa and ���Blacks��� from sub-Saharan Africa? By the way, other friends from Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Uganda were ���of course��� supporting Senegal. Why? Why ���of course?���

Some students in my sports history class protest at the start of the course that sport should not be ���political.��� But they learn that sports became political when European colonial officials and merchants first began organizing sporting events in Africa as a way to export the values of the ���civilizing mission,��� like hard work and fair play���as if Africans had no sense of these values themselves���and ���muscular Christianity��� to Africans. As the students consider their families��� experiences in Egypt with sport and corruption, with race, nation, and colonialism, this more critical (or perhaps cynical) view of sports history begins to make more sense. To the chagrin of those who still believe that sports can maintain some sort of ���purity,��� sport continues to be influenced by race, ethnicity, religion, social class, and of course, capitalism and nationalism. In the colonial era, race divided the ���winners��� from the ���losers��� as determined by global capitalism. Sport provided the allegedly non-lethal laboratory for demonstrating the racial hierarchies into which Westerners divided the world, especially after the publication of Charles Darwin���s theory of ���natural selection.��� If sport was the laboratory, war was the proving ground���manifest on the battlefields of the ���Scramble for Africa��� and the two world wars that followed.

Thus, perhaps I should not have been surprised to see binary conceptions of race and nation displayed in the stands of Cairo International Stadium or on the BeIN Sports Channel. Far from being a natural case of ���us��� against ���them,��� such racial and national consciousness emerged with capitalism and colonialism in mid-nineteenth century Africa. Though colonialism ended around 1960 in most of the Continent, its legacy was alive and well around the championship match for the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations.

July 25, 2019

Is Rammstein racist?

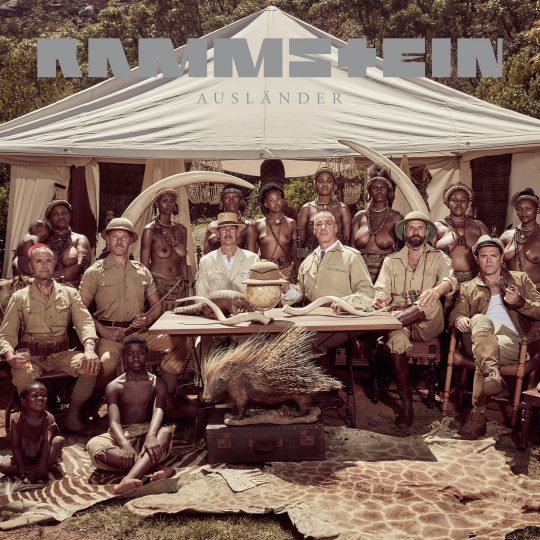

Still from video clip "Ausl��nder" by Rammstein.

At the end of May 2019, after a 10-year break, the German metal band Rammstein delivered a new album, the self-titled Rammstein. Then they dropped the music video for one of the lead singles, ���Ausl��nder��� (Foreigners). Rammstein is one of the best-selling German music acts ever. It is the most successful German rock band on the international scene. As a sign of their cultural impact, David Lynch used parts of their second album Sehnsucht (Longing) for his 1997 Lost Highway movie.

In the video clip for ���Ausl��nder,��� the band���s white members, arrive on a rubber boat (the likes that refugees use to cross the Mediterranean), at an African village. You can quickly make out that the video was filmed in Cape Town.��What follows, are a series of vignettes, of a colonial encounter that foregrounds the nakedness of black women and perhaps the ridicule of white men in Africa. The white men co-habitate with the black women and then leave; the women stay behind with mixed race children.

The new album very quickly registered a quarter of a million downloads. The live tour that was launched together with the album sold out across the world. By the time of writing, on June 29th, the video already had 14.2 million views on Youtube.

The reading that seems to dominate online commentaries in German is that this is a critique of colonialism. The lyrics are about furtive, casual sexual encounters, such as may have taken place during colonial times, and the title ���Ausl��nder��� does not refer to black people but to the white men who land on African shores. Yet, we cannot ignore the hapless ridicule that the black people elicit: they perpetuate a well-trodden path of racist depictions of black people. And black women are not only laughable, but they are also easily and eagerly available for the sexual gratification of white men. It is a grotesque, racist representation of black people.

Most Germans (and Europeans) do not see the video as racist. That black people are deployed here for the purpose of white entertainment, is mainstreamed. The other published video clip ���Deutschland��� (Germany) of the same album also instrumentalizes the black body for its own purposes.

Herein lies perhaps the banality of this (non)-event: Europe has regressed to a society in which, despite the apparent liberal openness to people of different backgrounds, and despite anti-racist legislation, black people are regularly depicted as stereotypes and are being used in a self-serving quest for fun, entertainment, and for facile art-with-a-political-subtext messaging.

The cover art for “Auslander.”

The cover art for “Auslander.”Like most of what passes as art, ���Ausl��nder��� contains different layers of meaning. It can be read as a critique of colonialism and sex tourism or masculine quests for sexual adventures, but this does not undo the racist representations. The intent may aim for progressive politics but the means are contrary. Chinua Achebe made a similar critique of Joseph Conrad���s Heart of Darkness. More than 40 years after he made that critique, the same still holds true.

Rammstein is a spectacular band���they deliver a spectacle.��The live shows are bombastic, even humorous, perhaps ironic or cynical, at times disgusting with a tremendous set, overwhelming displays, pyrotechnics, simulated porn, sadism, and so on. In short, jaw dropping entertainment. Ever since they entered the rock scene in the 1990s, they traded on extremes: exaggerated masculinity, Nazi scenography and hence they courted controversy that fueled their fame, and fortune.

They are a band that polarizes���one either loves them and appreciates how the break taboos and how they show little respect for historical and emotional fine-tuning; or one hates all the gruesome iconography, repetitive riffs and monotone electronic sounds and tries to ignore them.

German mainstream music criticism falls into the first category. Besides the imaginative re-interpretation of German history and national symbols, the over-the-top persiflage of what Germans hold dearly, in high and low culture, commentators point out that every now and then the band declares themselves if not left-leaning then rather ready to undermine German totalitarianism, from the left and the right.

However, what gets lost to the harmonious chorus of admirers of these pop-disruptors, is that right-wing neo-nazis also enjoy the fascist iconography even though the meaning is ironic. In a mass-consumer democracy, the audience makes their own interpretations. Far right neo-nazis are reportedly equally attracted to the martial, neo-fascist mise-en-scene as are those who “simply” enjoy the spectacle. Real fascists can ignore the ironic subtlety of the show and lyrics yet indulge in the spectacle that celebrates fascist aesthetics, including black people as happy, na��ve savages. In this role as spectators of black ridicule, mainstream audiences join neo-nazi, alt-right extremists.

In the face of the threat that the new, racist alt-right poses, Paul Gilroy turns to a renewed call for black humanity in his 2019 Holberg lecture. To counter a rising, global fascist threat, Gilroy proposes the reactualization of humanist ideals and practice, a radical humanism, that goes beyond the advocacy of rights and pushes against violence, nationalism and ethnic and racist essentialism, through mutual care and the recognition of all as ���vitally and mortally human.���

This is then perhaps what the reception of Rammstein in Germany reminds us: that racism comes in many forms and that liberal tolerance towards racist imagery easily supports re-emerging fascism rather than helps to chip away at deadly stereotypes.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers