Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 210

July 25, 2019

Rammstein and Racism

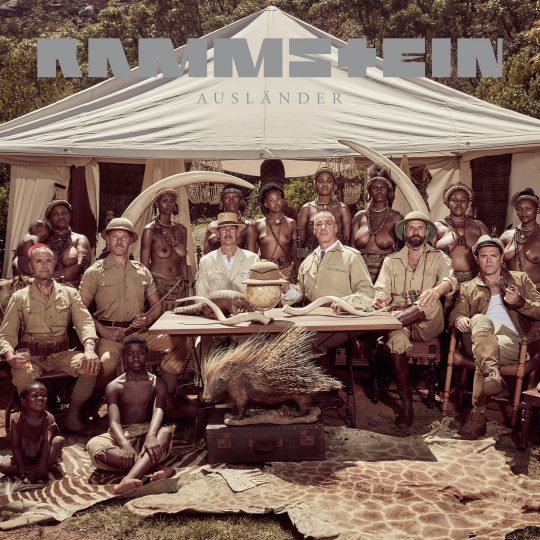

Still from video clip "Ausl��nder" by Rammstein.

At the end of May 2019, after a 10-year break, the German metal band Rammstein delivered a new album, the self-titled Rammstein. Then they dropped the music video for one of the lead singles, ���Ausl��nder��� (Foreigners).

Rammstein is one of the best-selling German music acts ever. It is the most successful German rock band on the international scene. As a sign of their cultural impact, David Lynch used parts of their second album Sehnsucht (Longing) for his 1997 Lost Highway movie.

In the video clip for ���Ausl��nder,��� the band���s white members, arrive on a rubber boat (the likes that refugees use to cross the Mediterranean), at an African village. You can quickly make out that the video was filmed in Cape Town.��What follows, are a series of vignettes, of a colonial encounter that foregrounds the nakedness of black women and perhaps the ridicule of white men in Africa. The white men cohabitate with the black women and then leave; the women stay behind with mixed race children.

The new album very quickly registered a quarter of a million downloads. The live tour that was launched together with the album sold out across the world. By the time of writing, on June 29th, the video already had 14.2 million views on Youtube.

The reading that seems to dominate online commentaries in German is that this is a critique of colonialism. The lyrics are about furtive, casual sexual encounters, such as may have taken place during colonial times, and the title ���Ausl��nder��� does not refer to black people but to the white men who land on African shores. Yet, we cannot ignore the hapless ridicule that the black people elicit: they perpetuate a well-trodden path of racist depictions of black people. And black women are not only laughable, but they are also easily and eagerly available for the sexual gratification of white men. It is a grotesque, racist representation of black people.

Most Germans (and Europeans) do not see the video as racist. That black people are deployed here for the purpose of white entertainment, is mainstreamed. The other published video clip ���Deutschland��� (Germany) of the same album also instrumentalizes the black body for its own purposes.

Herein lies perhaps the banality of this (non)-event���Europe has regressed to a society in which, despite the apparent liberal openness to people of different backgrounds, and despite anti-racist legislation, black people are regularly depicted as stereotypes and are being used in a self-serving quest for fun, entertainment, and for facile art-with-a-political-subtext messaging.

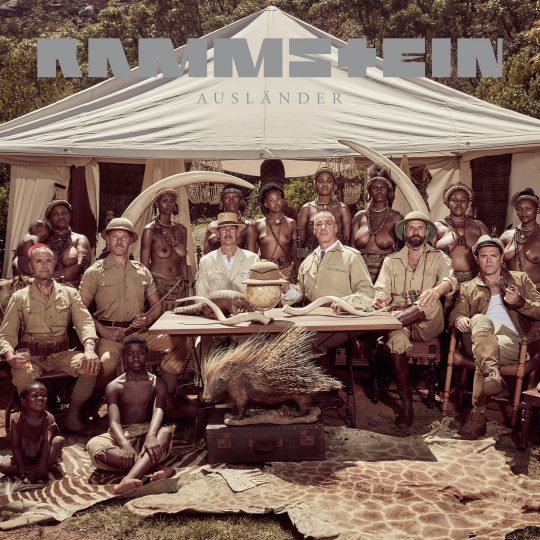

The cover art for “Auslander.”

The cover art for “Auslander.”Like most of what passes as art, ���Ausl��nder��� contains different layers of meaning. It can be read as a critique of colonialism and sex tourism or masculine quests for sexual adventures, but this does not undo the racist representations. The intent may aim for progressive politics but the means are contrary. Chinua Achebe made a similar critique of Joseph Conrad���s Heart of Darkness. More than 40 years after he made that critique, the same still holds true.

Rammstein is a spectacular band���they deliver a spectacle.��The live shows are bombastic, even humorous, perhaps ironic or cynical, at times disgusting with a tremendous set, overwhelming displays, pyrotechnics, simulated porn, sadism, and so on. In short, jaw dropping entertainment. Ever since they entered the rock scene in the 1990s, they traded on extremes: exaggerated masculinity, Nazi scenography and hence they courted controversy that fueled their fame, and fortune.

They are a band that polarizes���one either loves them and appreciates how the break taboos and how they show little respect for historical and emotional fine-tuning; or one hates all the gruesome iconography, repetitive riffs and monotone electronic sounds and tries to ignore them.

German mainstream music criticism falls into the first category. Besides the imaginative re-interpretation of German history and national symbols, the over-the-top persiflage of what Germans hold dearly, in high and low culture, commentators point out that every now and then the band declares themselves if not left-leaning then rather ready to undermine German totalitarianism, from the left and the right.

However, what gets lost to the harmonious chorus of admirers of these pop-disruptors, is that right-wing neo-nazis also enjoy the fascist iconography even though the meaning is ironic. In a mass-consumer democracy, the audience makes their own interpretations. Far right neo-nazis are reportedly equally attracted to the martial, neo-fascist mise-en-scene as are those who “simply” enjoy the spectacle. Real fascists can ignore the ironic subtlety of the show and lyrics yet indulge in the spectacle that celebrates fascist aesthetics, including black people as happy, na��ve savages. In this role as spectators of black ridicule, mainstream audiences join neo-nazi, alt-right extremists.

In the face of the threat that the new, racist alt-right poses, Paul Gilroy turns to a renewed call for black humanity in his 2019 Holberg lecture. To counter a rising, global fascist threat, Gilroy proposes the reactualization of humanist ideals and practice, a radical humanism, that goes beyond the advocacy of rights and pushes against violence, nationalism and ethnic and racist essentialism, through mutual care and the recognition of all as ���vitally and mortally human.���

This is then perhaps what the reception of Rammstein in Germany reminds us: that racism comes in many forms and that liberal tolerance towards racist imagery easily supports re-emerging fascism rather than helps to chip away at deadly stereotypes.

Racism comes in different guises

Still from video clip "Ausl��nder" by Rammstein.

At the end of May 2019, after a 10-year break, the German metal band Rammstein delivered a new album, the self-titled Rammstein. Then they dropped the music video for one of the lead singles, ���Ausl��nder��� (Foreigners).

Rammstein is one of the best-selling German music acts ever. It is the most successful German rock band on the international scene. As a sign of their cultural impact, David Lynch used parts of their second album Sehnsucht (Longing) for his 1997 Lost Highway movie.

In the video clip for ���Ausl��nder,��� the band���s white members, arrive on a rubber boat (the likes that refugees use to cross the Mediterranean), at an African village. You can quickly make out that the video was filmed in Cape Town.��What follows, are a series of vignettes, of a colonial encounter that foregrounds the nakedness of black women and perhaps the ridicule of white men in Africa. The white men cohabitate with the black women and then leave; the women stay behind with mixed race children.

The new album very quickly registered a quarter of a million downloads. The live tour that was launched together with the album sold out across the world. By the time of writing, on June 29th, the video already had 14.2 million views on Youtube.

The reading that seems to dominate online commentaries in German is that this is a critique of colonialism. The lyrics are about furtive, casual sexual encounters, such as may have taken place during colonial times, and the title ���Ausl��nder��� does not refer to black people but to the white men who land on African shores. Yet, we cannot ignore the hapless ridicule that the black people elicit: they perpetuate a well-trodden path of racist depictions of black people. And black women are not only laughable, but they are also easily and eagerly available for the sexual gratification of white men. It is a grotesque, racist representation of black people.

Most Germans (and Europeans) do not see the video as racist. That black people are deployed here for the purpose of white entertainment, is mainstreamed. The other published video clip ���Deutschland��� (Germany) of the same album also instrumentalizes the black body for its own purposes.

Herein lies perhaps the banality of this (non)-event���Europe has regressed to a society in which, despite the apparent liberal openness to people of different backgrounds, and despite anti-racist legislation, black people are regularly depicted as stereotypes and are being used in a self-serving quest for fun, entertainment, and for facile art-with-a-political-subtext messaging.

Promo pic.

Promo pic.Like most of what passes as art, ���Ausl��nder��� contains different layers of meaning. It can be read as a critique of colonialism and sex tourism or masculine quests for sexual adventures, but this does not undo the racist representations. The intent may aim for progressive politics but the means are contrary. Chinua Achebe made a similar critique of Joseph Conrad���s Heart of Darkness. More than 40 years after he made that critique, the same still holds true.

Rammstein is a spectacular band���they deliver a spectacle.��The live shows are bombastic, even humorous, perhaps ironic or cynical, at times disgusting with a tremendous set, overwhelming displays, pyrotechnics, simulated porn, sadism, and so on. In short, jaw dropping entertainment. Ever since they entered the rock scene in the 1990s, they traded on extremes: exaggerated masculinity, Nazi scenography and hence they courted controversy that fueled their fame, and fortune.

They are a band that polarizes���one either loves them and appreciates how the break taboos and how they show little respect for historical and emotional fine-tuning; or one hates all the gruesome iconography, repetitive riffs and monotone electronic sounds and tries to ignore them.

German mainstream music criticism falls into the first category. Besides the imaginative re-interpretation of German history and national symbols, the over-the-top persiflage of what Germans hold dearly, in high and low culture, commentators point out that every now and then the band declares themselves if not left-leaning then rather ready to undermine German totalitarianism, from the left and the right.

However, what gets lost to the harmonious chorus of admirers of these pop-disruptors, is that right-wing neo-nazis also enjoy the fascist iconography even though the meaning is ironic. In a mass-consumer democracy, the audience makes their own interpretations. Far right neo-nazis are reportedly equally attracted to the martial, neo-fascist mise-en-scene as are those who “simply” enjoy the spectacle. Real fascists can ignore the ironic subtlety of the show and lyrics yet indulge in the spectacle that celebrates fascist aesthetics, including black people as happy, na��ve savages. In this role as spectators of black ridicule, mainstream audiences join neo-nazi, alt-right extremists.

In the face of the threat that the new, racist alt-right poses, Paul Gilroy turns to a renewed call for black humanity in his 2019 Holberg lecture. To counter a rising, global fascist threat, Gilroy proposes the reactualization of humanist ideals and practice, a radical humanism, that goes beyond the advocacy of rights and pushes against violence, nationalism and ethnic and racist essentialism, through mutual care and the recognition of all as ���vitally and mortally human.���

This is then perhaps what the reception of Rammstein in Germany reminds us: that racism comes in many forms and that liberal tolerance towards racist imagery easily supports re-emerging fascism rather than helps to chip away at deadly stereotypes.

Waterless scars and pipe dreams in Nairobi

Children fetching water. Image credit Annie Pfingst.

There will be no long rains in Kenya this year. After a season of much higher than normal temperatures, the meteorological department finally confirmed what we least hoped for: more famine, more drought.

But many segments of the population have already been living in drought conditions for years across our republic: an estimated 41% of Kenyans still use ���unimproved water sources, such as ponds, shallow wells and rivers��� to access this resource. Considering we just paid 447 billion Kenya shillings (roughly $3.2 billion) for a geriatric train, there is really no reason why citizens don���t have any water.

While participating in community research on water rights in the East of Nairobi, more popularly known as Eastlands, one mother told us that sometimes she has to choose between using water to wash her baby or to cook. Other family members told us about how children died a day after drinking unclean water, and another elderly aunty told us about how the water she has access to smells and looks like sewage. In this same locality, a small NGO clinic reported that they received, at least, 15 cases of cholera and 200 cases of typhoid every day.

This is happening even as the Governor of Nairobi continues to promise ���water for all.���

Granted the dry taps, ponds and dams are now exacerbated by climate change, a process beyond both our making and the continent���s sole control, as the floods in Mozambique tragically demonstrate. However, many Kenyans have already been living in situations of semi-permanent drought, as have historically lacked access to the ���clean, safe and adequate water��� provided for in the 2010 Constitution.

Much of their day is then spent looking for water: waiting for it to arrive, holding jerri cans in the line behind a tap or broken pipe, and then storing in in whatever medium is available.

Fetching water. Image credit Annie Pfingst.

Fetching water. Image credit Annie Pfingst.Rich people can overcome water limits (and still drench their immaculate lawns) by either having their own boreholes, conducting rich people advocacy and even, get this, creating their own water company as Runda (enclave of embassies, UN and embassy staff) did. And even when there is water rationing, they get timetables for when it will disappear.

Meanwhile, a few kilometres from Runda, on the other side of Thika Superhighway, residents are drinking one glass of water a day, even when our County water budget is 360 million shillings (36 million dollars). They don���t have water pipes, and so that means that they have to purchase unsafe water from unreliable sources. As a consequence,

for our city���s majority in poor urban settlements, ���cholera inabeba watu kama transporter������cholera is carrying people away like a truck.

And they still pay more for this cholera-infested water.

Indeed the costs are excessive. Vincent Ng���ethe at Africa Check writes that:

At KSh2 per 20 l jerrycan, slum dwellers pay KSh100 per m��, increasing to a massive KSh2,500 per m�� when the price is at��KSh 50 per jerrycan. In comparison,��residential customers��of the Nairobi Water Company pay KSh204 for their first 6,000 l (KSh29.4 per m��), KSh53 for water use between 7,000 and 60,000 l and KSh64/m�� thereafter. Those living in flats or gated communities pay KSh53 per m�� for bulk supply.

Ultimately, poor Nairobi residents pay close to four times more for water that is much less clean, adequate or consistent.

All the small business owners, local activists, mothers, students and, even, carwash operators who took part in our participatory research on water rights know this intimately.

Broken pipes. Image credit Annie Pfingst.

Broken pipes. Image credit Annie Pfingst.Like those in Flint, Palestine, Khayelitsha and beyond, they know that the lack of water is not an issue of a limited public purse, but rather state will. It is also a business. Cartels at both the Nairobi County level and the Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company create shortages, control the supply and the cost of water. They also neglect or don���t establish much needed water infrastructures for poor residents, and even, it is rumored, prevent neighborhoods susceptible to fires from getting water hydrants because these could potentially give residents free water.

When community members devise their own means of getting what the County of Nairobi/Nairobi Water and Sewerage Company deem ���illegal��� or ���non-revenue��� water, they are violently penalized.

Because of this, Eastlands residents involved in the water rights research demanded that the government:

Restructure systems to make sure that water is not privatized and is accessible to all

Close bottled water companies since they are cartels

Build safe, secure and adequate piped water networks in all marginalized neighborhoods in Nairobi and in other counties, and close all cartels associated with the Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company

Distribute water according to population density and not according to wealth

Improve and increase sanitation facilities in all marginalized neighborhoods to prevent diseases like cholera and typhoid.

Provide free health care services for those affected by inadequate and dirty water, sanitation and sewage infrastructures

Improve water policies, comprehensively implement the current water legislation, and include strong people-centered accountability mechanisms

Install fire hydrants in all marginalized neighborhoods with frequent fires

All water bodies should have at least three representatives from poor urban settlements on their board. These should include a woman, a community activist, and a person with a disability chosen by the community

Impeachment of all presidents, governors and water company CEOs who do not implement article 43 of the Kenyan Constitution.

While impeachment of all presidents, governors and water company CEO���s would be the best case scenario, for now residents just want some water: there are too many ���waterless scars��� one said, and water infrastructure should not be a pipe dream.

July 24, 2019

Ladan Osman’s urgent poetry and our founding myths

Cordoba, Spain September 2018. Image credit Joe Penney.

The poet Ladan Osman���s work is lyrical, forceful, playful, piercing, fun, funny, and also sexy. Perhaps its impact is felt most deeply because of a trait so often lacking in today���s discourse: its sincerity. In her second collection of poems Exiles of Eden (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2019), Osman delivers an incredibly urgent call to action against founding narratives that are so prevalent in American society, and which are poisonous to women and people of color. It is a strong antidote to the Vice-style cynicism that has helped usher a white supremacist into the US presidency by soaking popular culture with the dangerous notion that taking things seriously is uncouth.

Raised in Columbus, Ohio, Osman won the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poetry for her first collection of poems, The Kitchen Dweller���s Testimony. Her experience in the American Midwest is the backdrop for many of her poems, but her speakers carry us around the world, and have a special longing for Osman���s birthplace Mogadishu and the sea that surrounds Somalia���s capital city. In Exiles of Eden, a title that refers to Adam and Eve and implies that the original human story is that of seeking refuge, the poems inhabit worlds of immense love, intense anguish, and quiet contemplation, sometimes all within the same stanza. Osman refuses to be defined by anyone else���s vision of who she is and what she can do in poetry. Her lack of engagement with common tropes of writing for voices cast as ���marginalized��� in popular American narratives is part of what makes her work so compelling.

Given the singularity of her work and the relevance and importance of a Somali-American woman���s experience to the current political moment, I asked Osman if she would share her thoughts on some of her poems, white supremacy in America, and Adam and Eve.

Joe Penney

As someone who looks so closely at what home and citizenship mean, what was your reaction to Trump���s comments about the four Congresswomen ���going home���?

Ladan Osman

I think the obvious thing is that it’s important to determine who the other is and what the other deserves, so that you can clarify to yourself or to the masses, who it is that actually belongs and who it is that has the right to exclude, and even the right to identify and label.

So much of it seems to have to do with who is seen and who does the seeing, and why it’s so important to unsee aspects of citizenship, aspects of civic duty, especially when we’re talking about Congress. These are people who have been elected to represent the people and to execute civic duties. For them to be attacked on the basis of their citizenship is pretty unnerving. It���s so glaringly illogical, and so lacking in decorum.

I mean, I think the point is to be disturbing, the point is to be disruptive. And I think the point is to cover up the ways that these Congresswomen are disruptive in their politics, and to shift the emphasis to who a racist would like them to be on the basis of perceived nationality when they’re all American.

I think another thing that I wish I saw more conversation about in public discourse is that when you try to exclude a person from the place where they’re rooted, where they’re invested, where they’re serving, and to define home as something that they are outside of, or don’t deserve���the intention seems to be to create a sense of dislocation, and one that’s not just physical or geographic, but psychic, emotional. Something that disrupts the psychology of the citizen. And it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with logic or legality, it’s just to create harm, and to set a standard for what’s OK in discourse.

Reading at the Sapanca Poetry Festival in Sakarya, Turkey October 2018. Image credit Joe Penney.

Reading at the Sapanca Poetry Festival in Sakarya, Turkey October 2018. Image credit Joe Penney.Joe Penney

There seems to be a singling out of Ilhan Omar specifically, as a target of hate. Trump linked her to Al Qaeda and brought up that ���some people��� comment again. Besides AOC, it seems like she’s almost become the main target of hate, and sort of the right wing���s painting of a nightmare for what America has become. How do you see this particularly disturbing racism against Omar, the first Somali-American elected to Congress?

Ladan Osman

Ilhan is a black woman who is visibly Muslim, and doesn’t shy away from her identity. Besides that, she and the other targeted Congresswomen are vocalizing a set of policies that are beyond uncomfortable for this administration. There’s hope in the appearance of these politicians: that they’re here, that they can run, that they can succeed, that they can be so widely celebrated. It’s something that I believe is beyond the imagination of the typical racist and typical misogynist.

I��can see why people who think like that would experience her as a nightmare, because she is disrupting the order of things and the order of how things are supposed to be, and forcing them to confront their limitations in real time. You can’t argue with who or what���s already there. Just because you call it a blight in your vision, or a blight upon the American record doesn’t undo her appearance, it doesn’t undo the fact that she’s there. And so what can you do, then, except to assassinate the character of this Congresswoman and to attempt to undermine her policies and everything that she stands for, and attempt to also isolate her further from these already isolated Congresswomen.

You asked about the ���some people��� comment. There are certain words and phrases that I’m really uncomfortable saying, because people are already prepared to read me as a threat, and as violent and as in cooperation with terrorists. So the words ���terrorism,��� ���9/11,��� there’s a long vocabulary list������bomb������there are things that I know not to say in public. And the same goes for so many Muslim people I know.

I noticed that most of us, instead of saying bomb, we say the ���b-word��� or for terrorist, we say the ���t-word.��� I wondered if it was a (now) very natural avoidance of saying that word, especially in front of a crowd of people, in official space, and when you’re being recorded. So many of us now, in trying to be careful, in ways that we’ve been forced to be careful, trying to demonstrate loyalty, caution, especially as someone living in the US but never read as an American, I wonder if it’s possible that was just a very typical verbal glitch. Because I would be very surprised if she or anyone in her family were throwing any of those words around, especially in public places.

Joe Penney

In your poem ���Boat Journey,��� the speaker asks, ���What is it like to be so free? / To drift in a water in a country you call/Your own. Unprepared because you can laugh/Into an official���s face. Explain, offer no apology.��� Is this descriptive of whiteness in America?

Ladan Osman

I��was actually watching these young women in a boat. I noticed that���except for a fleeting concern about their safety because they didn’t really seem prepared���I didn’t really think anything. But then when I tried to draft what a speaker would think, and what another voice could offer, especially in the context of other crises, those questions of citizenship and of whiteness, of privilege, and who’s free very quickly rose to the surface and became the obvious thing that was worth exploring.

Part of whiteness is not really being seen for your whiteness, it’s something that���s meant to be almost atmospheric, you know, you just take it for granted that it’s there, and it’s supposed to be there. And it’s what���s supposed to sustain everything. Anything that tries to challenge it is unnatural; it’s like a kind of biosphere that you’re attempting to destroy. And so I don’t think that those real-life women who were at Promontory Point in Chicago, I don’t think that they were thinking at all about their whiteness. I presume that they’re American citizens just based on hearing them speak and their very Midwestern accents.

But that I knew inside myself, actually, and the speaker of the poem would agree, I would never get in a boat like that. I would never assume that I could do that kind of experiment and things would be fine, that I would be safe, and onlookers would possibly help me if I was doing something I wasn’t supposed to do, or drifting in water I wasn’t supposed to be in.

I would assume that, you know, you can’t carry a lot of stuff with you for fear of it falling into the water. I would be really nervous about that. Because then what if there’s a question, as there has been a question on American highways and American streets, about my citizenship, and I don’t have proof of those documents with me. And I’m doing something that could very easily be seen as suspicious, you know, ���What are you doing on this water? What’s your aim? Leisure, taking in the beauty of the water? That’s ridiculous.��� Like, of course, I could be doing that and have every right to. But it would be hard for the people who enforce the law to imagine someone like me taking up that space and exercising that freedom.

Cordoba, Spain September 2018 by Joe Penney.

Cordoba, Spain September 2018 by Joe Penney.Joe Penney

You end the book on such a triumphant and affirming note.�� There are parts in the poem ���Refusing Eurydice��� where you affirm your identity and where you’re from and who you are. And it ends on ���We���re looking for a better myth. / We’ve only been looking since Eve.��� It’s very positive but at the same time, it’s very ambitious, because from what I understand, you’re challenging the founding myth of three major world religions. How is this ambition in storytelling received, in particular by an American audience?

Ladan Osman

I think it depends which American audience, but I think in general, not well. I’ve had editors write to me, ���Who do you think you are? What do you think you’re doing to American poetry?��� Which is an interesting accusation. There���s a veiled accusation there; what would I be trying to do to American poetry? As if it’s a specific figure, and I’m trying to stab it or something. I think that attempting to do anything in literature is read as an affront. I’ve had people tell me (and this was acceptable in my MFA program) that if they saw any poem or submission with my name on it, they would immediately throw it in the garbage, and I���ve been told even by loved ones that I should consider publishing under a different name because people would not be willing to receive anything I was saying with my own name.

The last poem addresses most specifically women, femmes and non-binary people, although the ���we��� does include everyone. There are specific images that link to those identities because the myth that we have in place comes with its heaviness, and it comes with its melancholy. The story of Eve���though in general, not a lot of Muslim people look at it this way���you know, it’s all her fault, basically. And it’s like, wouldn’t it be just like a man to say, ���it was her, she did it.��� And now there’s all this commotion.

So many different things play out that way. You can be considered frail and inept, but then at the same time be considered a walking chaos. On one hand, you’re the whole center of humanity, some kind of like cosmic womb walking around, but then on the other, very likely to be the downfall of society by not being submissive enough, by not being conventional enough, by not submitting to the world order that is already at hand, which has never been advantageous for us.

We do need different and better stories. We need to see the stories that were tossed out because they had women voices in them, or they had woman interpreters, or they had woman spiritualists that were depicted or who were in conversation. And that’s not, you know, talking about the holy books. That’s really just even in the history and the interpretations of religion itself, like, who are the custodians of those myths? And not only what are considered the holy books but this is also true for the foundational artworks and the foundational poetry and what established the lyric. Where’s our place in that? And if you can’t find your place, you have to break it open, you have to reconfigure it and see what there can be for you.

That act of invention, for me, is how I show my respect for the power of storytelling, and the power of myth and the fact that people need to recite things to keep themselves going. And so it becomes critical for all of us to be able to have things to recite that we belong inside of. It’s ambitious for me to wake up day to day and walk around the world and think that, to know that I have the right to my intellectual exercises. That’s already much more ambitious than what���s been laid out for me. So it’s like, why not put that stuff down on a piece of paper and bind it in a book?

Brooklyn NY July 2019. Image credit Joe Penney.

Brooklyn NY July 2019. Image credit Joe Penney.Joe Penney

In a writing sense, what type of narrative is expected of you?

Ladan Osman

I think that it’s really necessary to have some of these narratives, and this is not at all to disparage the people who have come before me and my contemporaries, many of whom are friends, and the people who are coming after me. But I think the expectation for me is to be a bruised, sad, black girl, who is absolutely overcome with these harms. To let myself become preoccupied with the stereotypes, resisting them trying to prove my humanity, and then adopting some of this imperialist language to talk about Somali people as being nothing, of having no home, nothing to go back to, having no dignity. You know, these things that really speak to a poverty of the heart, because you’re still a human and intact���and this is such an obvious thing to say���but you’re still a human and you’re intact, regardless of the material situation that you’re in, regardless of the thing that you’re attempting to flee.

I think that if I were more willing to disregard my own humanity and the humanity of people who look like me, that approach would be more welcome. Those are some of the notes I’ve gotten in the past: “Well, why don’t you just explain your Somali-ness, or just randomly put the names of towns or rivers and explain who you are and where you come from to a western sensibility.” But the explanation is always coming from a position of need, a position of pain, a position of brokenness. I know that I can’t be broken. So how can I write those poems?

Landan Osman’s urgent poetry and our founding myths

Cordoba, Spain September 2018. Image credit Joe Penney.

The poet Ladan Osman���s work is lyrical, forceful, playful, piercing, fun, funny, and also sexy. Perhaps its impact is felt most deeply because of a trait so often lacking in today���s discourse: its sincerity. In her second collection of poems Exiles of Eden (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2019), Osman delivers an incredibly urgent call to action against founding narratives that are so prevalent in American society, and which are poisonous to women and people of color. It is a strong antidote to the Vice-style cynicism that has helped usher a white supremacist into the US presidency by soaking popular culture with the dangerous notion that taking things seriously is uncouth.

Raised in Columbus, Ohio, Osman won the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poetry for her first collection of poems, The Kitchen Dweller���s Testimony. Her experience in the American Midwest is the backdrop for many of her poems, but her speakers carry us around the world, and have a special longing for Osman���s birthplace Mogadishu and the sea that surrounds Somalia���s capital city. In Exiles of Eden, a title that refers to Adam and Eve and implies that the original human story is that of seeking refuge, the poems inhabit worlds of immense love, intense anguish, and quiet contemplation, sometimes all within the same stanza. Osman refuses to be defined by anyone else���s vision of who she is and what she can do in poetry. Her lack of engagement with common tropes of writing for voices cast as ���marginalized��� in popular American narratives is part of what makes her work so compelling.

Given the singularity of her work and the relevance and importance of a Somali-American woman���s experience to the current political moment, I asked Osman if she would share her thoughts on some of her poems, white supremacy in America, and Adam and Eve.

Joe Penney

As someone who looks so closely at what home and citizenship mean, what was your reaction to Trump���s comments about the four Congresswomen ���going home���?

Ladan Osman

I think the obvious thing is that it’s important to determine who the other is and what the other deserves, so that you can clarify to yourself or to the masses, who it is that actually belongs and who it is that has the right to exclude, and even the right to identify and label.

So much of it seems to have to do with who is seen and who does the seeing, and why it’s so important to unsee aspects of citizenship, aspects of civic duty, especially when we’re talking about Congress. These are people who have been elected to represent the people and to execute civic duties. For them to be attacked on the basis of their citizenship is pretty unnerving. It���s so glaringly illogical, and so lacking in decorum.

I mean, I think the point is to be disturbing, the point is to be disruptive. And I think the point is to cover up the ways that these Congresswomen are disruptive in their politics, and to shift the emphasis to who a racist would like them to be on the basis of perceived nationality when they’re all American.

I think another thing that I wish I saw more conversation about in public discourse is that when you try to exclude a person from the place where they’re rooted, where they’re invested, where they’re serving, and to define home as something that they are outside of, or don’t deserve���the intention seems to be to create a sense of dislocation, and one that’s not just physical or geographic, but psychic, emotional. Something that disrupts the psychology of the citizen. And it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with logic or legality, it’s just to create harm, and to set a standard for what’s OK in discourse.

Reading at the Sapanca Poetry Festival in Sakarya, Turkey October 2018. Image credit Joe Penney.

Reading at the Sapanca Poetry Festival in Sakarya, Turkey October 2018. Image credit Joe Penney.Joe Penney

There seems to be a singling out of Ilhan Omar specifically, as a target of hate. Trump linked her to Al Qaeda and brought up that ���some people��� comment again. Besides AOC, it seems like she’s almost become the main target of hate, and sort of the right wing���s painting of a nightmare for what America has become. How do you see this particularly disturbing racism against Omar, the first Somali-American elected to Congress?

Ladan Osman

Ilhan is a black woman who is visibly Muslim, and doesn’t shy away from her identity. Besides that, she and the other targeted Congresswomen are vocalizing a set of policies that are beyond uncomfortable for this administration. There’s hope in the appearance of these politicians: that they’re here, that they can run, that they can succeed, that they can be so widely celebrated. It’s something that I believe is beyond the imagination of the typical racist and typical misogynist.

I��can see why people who think like that would experience her as a nightmare, because she is disrupting the order of things and the order of how things are supposed to be, and forcing them to confront their limitations in real time. You can’t argue with who or what���s already there. Just because you call it a blight in your vision, or a blight upon the American record doesn’t undo her appearance, it doesn’t undo the fact that she’s there. And so what can you do, then, except to assassinate the character of this Congresswoman and to attempt to undermine her policies and everything that she stands for, and attempt to also isolate her further from these already isolated Congresswomen.

You asked about the ���some people��� comment. There are certain words and phrases that I’m really uncomfortable saying, because people are already prepared to read me as a threat, and as violent and as in cooperation with terrorists. So the words ���terrorism,��� ���9/11,��� there’s a long vocabulary list������bomb������there are things that I know not to say in public. And the same goes for so many Muslim people I know.

I noticed that most of us, instead of saying bomb, we say the ���b-word��� or for terrorist, we say the ���t-word.��� I wondered if it was a (now) very natural avoidance of saying that word, especially in front of a crowd of people, in official space, and when you’re being recorded. So many of us now, in trying to be careful, in ways that we’ve been forced to be careful, trying to demonstrate loyalty, caution, especially as someone living in the US but never read as an American, I wonder if it’s possible that was just a very typical verbal glitch. Because I would be very surprised if she or anyone in her family were throwing any of those words around, especially in public places.

Joe Penney

In your poem ���Boat Journey,��� the speaker asks, ���What is it like to be so free? / To drift in a water in a country you call/Your own. Unprepared because you can laugh/Into an official���s face. Explain, offer no apology.��� Is this descriptive of whiteness in America?

Ladan Osman

I��was actually watching these young women in a boat. I noticed that���except for a fleeting concern about their safety because they didn’t really seem prepared���I didn’t really think anything. But then when I tried to draft what a speaker would think, and what another voice could offer, especially in the context of other crises, those questions of citizenship and of whiteness, of privilege, and who’s free very quickly rose to the surface and became the obvious thing that was worth exploring.

Part of whiteness is not really being seen for your whiteness, it’s something that���s meant to be almost atmospheric, you know, you just take it for granted that it’s there, and it’s supposed to be there. And it’s what���s supposed to sustain everything. Anything that tries to challenge it is unnatural; it’s like a kind of biosphere that you’re attempting to destroy. And so I don’t think that those real-life women who were at Promontory Point in Chicago, I don’t think that they were thinking at all about their whiteness. I presume that they’re American citizens just based on hearing them speak and their very Midwestern accents.

But that I knew inside myself, actually, and the speaker of the poem would agree, I would never get in a boat like that. I would never assume that I could do that kind of experiment and things would be fine, that I would be safe, and onlookers would possibly help me if I was doing something I wasn’t supposed to do, or drifting in water I wasn’t supposed to be in.

I would assume that, you know, you can’t carry a lot of stuff with you for fear of it falling into the water. I would be really nervous about that. Because then what if there’s a question, as there has been a question on American highways and American streets, about my citizenship, and I don’t have proof of those documents with me. And I’m doing something that could very easily be seen as suspicious, you know, ���What are you doing on this water? What’s your aim? Leisure, taking in the beauty of the water? That’s ridiculous.��� Like, of course, I could be doing that and have every right to. But it would be hard for the people who enforce the law to imagine someone like me taking up that space and exercising that freedom.

Cordoba, Spain September 2018 by Joe Penney.

Cordoba, Spain September 2018 by Joe Penney.Joe Penney

You end the book on such a triumphant and affirming note.�� There are parts in the poem ���Refusing Eurydice��� where you affirm your identity and where you’re from and who you are. And it ends on ���We���re looking for a better myth. / We’ve only been looking since Eve.��� It’s very positive but at the same time, it’s very ambitious, because from what I understand, you’re challenging the founding myth of three major world religions. How is this ambition in storytelling received, in particular by an American audience?

Ladan Osman

I think it depends which American audience, but I think in general, not well. I’ve had editors write to me, ���Who do you think you are? What do you think you’re doing to American poetry?��� Which is an interesting accusation. There���s a veiled accusation there; what would I be trying to do to American poetry? As if it’s a specific figure, and I’m trying to stab it or something. I think that attempting to do anything in literature is read as an affront. I’ve had people tell me (and this was acceptable in my MFA program) that if they saw any poem or submission with my name on it, they would immediately throw it in the garbage, and I���ve been told even by loved ones that I should consider publishing under a different name because people would not be willing to receive anything I was saying with my own name.

The last poem addresses most specifically women, femmes and non-binary people, although the ���we��� does include everyone. There are specific images that link to those identities because the myth that we have in place comes with its heaviness, and it comes with its melancholy. The story of Eve���though in general, not a lot of Muslim people look at it this way���you know, it’s all her fault, basically. And it’s like, wouldn’t it be just like a man to say, ���it was her, she did it.��� And now there’s all this commotion.

So many different things play out that way. You can be considered frail and inept, but then at the same time be considered a walking chaos. On one hand, you’re the whole center of humanity, some kind of like cosmic womb walking around, but then on the other, very likely to be the downfall of society by not being submissive enough, by not being conventional enough, by not submitting to the world order that is already at hand, which has never been advantageous for us.

We do need different and better stories. We need to see the stories that were tossed out because they had women voices in them, or they had woman interpreters, or they had woman spiritualists that were depicted or who were in conversation. And that’s not, you know, talking about the holy books. That’s really just even in the history and the interpretations of religion itself, like, who are the custodians of those myths? And not only what are considered the holy books but this is also true for the foundational artworks and the foundational poetry and what established the lyric. Where’s our place in that? And if you can’t find your place, you have to break it open, you have to reconfigure it and see what there can be for you.

That act of invention, for me, is how I show my respect for the power of storytelling, and the power of myth and the fact that people need to recite things to keep themselves going. And so it becomes critical for all of us to be able to have things to recite that we belong inside of. It’s ambitious for me to wake up day to day and walk around the world and think that, to know that I have the right to my intellectual exercises. That’s already much more ambitious than what���s been laid out for me. So it’s like, why not put that stuff down on a piece of paper and bind it in a book?

Brooklyn NY July 2019. Image credit Joe Penney.

Brooklyn NY July 2019. Image credit Joe Penney.Joe Penney

In a writing sense, what type of narrative is expected of you?

Ladan Osman

I think that it’s really necessary to have some of these narratives, and this is not at all to disparage the people who have come before me and my contemporaries, many of whom are friends, and the people who are coming after me. But I think the expectation for me is to be a bruised, sad, black girl, who is absolutely overcome with these harms. To let myself become preoccupied with the stereotypes, resisting them trying to prove my humanity, and then adopting some of this imperialist language to talk about Somali people as being nothing, of having no home, nothing to go back to, having no dignity. You know, these things that really speak to a poverty of the heart, because you’re still a human and intact���and this is such an obvious thing to say���but you’re still a human and you’re intact, regardless of the material situation that you’re in, regardless of the thing that you’re attempting to flee.

I think that if I were more willing to disregard my own humanity and the humanity of people who look like me, that approach would be more welcome. Those are some of the notes I’ve gotten in the past: “Well, why don’t you just explain your Somali-ness, or just randomly put the names of towns or rivers and explain who you are and where you come from to a western sensibility.” But the explanation is always coming from a position of need, a position of pain, a position of brokenness. I know that I can’t be broken. So how can I write those poems?

Nigeria’s first lesbian documentary

Pamela Adie. Still from Under The Rainbow.

I first watched Under the Rainbow, a visual memoir by Pamela Adie, the day after Binyavanga Wainaina died. This was not intentional. I was preparing for an upcoming research trip to Lagos and had been in touch with Adie about her film. She was kind enough to send me a screener so that I could watch it before our interview. But thinking about Under the Rainbow alongside the passing of Wainaina underscored the confessional texture of the film, which, like Wainaina���s�����I am a homosexual, mum,��� is a layered coming out story that is told in order to make a larger political gesture about queer visibility in Africa.

There are several reasons that one should take note of Under the Rainbow. First, the film is written and produced by Adie and shot by award-winning Nollywood director Asurf Oluseyi, who directed the ground-breaking queer short Hell or High Water. In other words, unlike so many documentaries about LGBTQ life in Africa, Under the Rainbow was not made by or for westerners. When I met with Adie she told me that she had two primary reasons for making the film: to combat the notion that queer Nigerians don���t exist and to challenge the idea that homosexuality is un-African by demonstrating that it is not a phase or a learned behavior. The documentary is intended to circulate in African contexts and, as Adie states in the film, to ���create awareness and accelerate acceptance.���

It premiered at a private event on June 28th at the residence of the British Deputy High Commission in Lagos, who offered a safe space for the screening. Yet, the event was very much a Nigerian affair. Several high-profile Nigerians were in attendance���including Nollywood actors, media entrepreneurs, and human rights activists. At the premiere Adie emphasized that the film was also made to contribute to the conversations by and about Nigerian lesbians who are often excluded from conversations about equal rights in the country.

Under the Rainbow is very much part of a larger strategy within the LGBTQ movement in Nigeria to use storytelling for advocacy. ���We���re at a point in Nigeria,��� Adie says in the film, ���where, as a movement, one of our immediate goals is to change hearts and minds.�����This is being achieved in part by films and web series like Hell or High Water, We Don���t Live Here Anymore, and Everything in Between, all produced by The Initiative For Equal Rights which currently shares office space and several board members with The Equality Hub.��But it is also being accomplished through the telling of personal stories.��Under the Rainbow comes on the heels of Lives of Great Men, the award-winning memoir by Nigerian globe-trotting journalist Chik�� Frankie Edozien, as well as two powerful collections of testimonials by queer Nigerians, Unoma Azuah���s Blessed Bodies and Azeenarh Mohammed, Chitra Nagarajan and Rafeeat Aliyu���s She Called Me Woman. (Azuah is also currently putting finishing touches on her own much-anticipated memoir about growing up as a lesbian in Nigeria).��All of these stories work to counter narratives that erase, undermine, and stereotype queer voices in Nigeria by insisting that queer Nigerians exist and feel and matter.

Another reason that Under the Rainbow stands out is that it highlights narratives of queer success without denying queer vulnerability. Adie talks about how at age 25 she married a man (whom she describes as a ���true gentleman���) because she felt that that was what she was supposed to do. She talks about ending the marriage and her depression and the liquid that looked like gutter water that her mother asked her to drink as part of a spiritual cleansing.��But she also talks about returning to Nigeria in 2014 (the same year the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act was passed) and getting a job as a senior campaign manager for All Out Africa. She discusses her role in getting homophobic pastor Steven Anderson banned from South Africa and the UK and also kicked out of Botswana.��She also mentions her attendance at the 2017 World Economic forum in Davos and her selection as one of 200 Obama Foundation Leaders in the Africa program. Despite, or perhaps because of, her struggles, Adie has been able to be an out, vocal leader in her community.

Under the Rainbow is decidedly not a story that perpetuates what Keguro Macharia, in 2010, called the single story of African homophobia. In fact, at one of the screenings in Lagos, Adie said that although some of her friends have distanced themselves from her because of her visibility, the film has actually helped connect her to many supporters and allies, both queer and straight.��Adie, then, models some of the ways that queer people and allies can begin to change the narratives about LGBTQ Nigerians.

Towards the end of the film, Adie mentions how she tried to get other LBQ women to appear in the film but that they were concerned for their security.��She then asks, ���who is providing security for me?��� What is fascinating is not the threat of violence that lingers behind the question but rather that she does not seem overly concerned by it.��The film, helped by Oluseyi���s beautiful score and cinematography, conveys Adie���s self-acceptance as so steadfast that she seems to be saying that whatever happens (and nothing has so far) will have been worth it.

The film will be screening Friday, July 26th in Accra and more screenings will be organized in both Lagos and Abuja.��If you are in any of these cities, or have friends or family there, please make sure this incredibly important film is seen.��Information on screenings will be on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook.

July 23, 2019

Eight hours in Addis

Image supplied by author.

There are blue and yellow taxis at Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa. Taxi color is a code for age. Blue taxis are old cars. Three decades old. Sometimes more. Yellow taxis are a bit newish. Not posh, luxurious taxis. Just new.

Bole International Airport is fascinating chorus of organized chaos. A line of passengers form somehow within this chaos. A uniformed airport worker pulls every African looking person aside. Asks if any of us has visited the Congo in the recent past. He says something about Ebola and looks relieved that none of us has visited the Congo. Another one follows closely enquiring about our visas. I don���t have one. I pull out my Kenyan passport and hand it over to him. Then it happens. The man lights up. I have come to learn that any smile in an airport when one bears an African passport is always a good thing. It signals a promise of African brotherhood, to fill any gaps an African passport may be too weak to fill. Then it happens. I am pushed to the head of the line. First time ever, I am receiving privileged treatment based on my Kenyan passport. I quickly learn that Ethiopia has special relationship with Kenya and Eritrea. We, Kenyans, do not need any form of visa to visit Ethiopia. We just show up. And get special treatment too. My mind is blown. Kenya is a home to many Ethiopian immigrants. And in most instances, Kenya has assimilated foreigners successfully without discrimination. This is one of the reason why Nairobi is a melting pot of African culture and those of other foreign nations, floating in the rich spirit of Ubuntu. But this special treatment must be in appreciation of something Kenya and Ethiopia did to each other many years ago. Something special probably between President Jomo Kenyatta and Emperor Haile Selassie. Or before. Something about pre-independence Pan-African brotherhood. Haile Selassie Avenue in the heart of Nairobi permanently sealed this brotherhood in our national psyche.

A few months before this trip, I arrived at Jomo Kenyatta National Airport, Kenya from Dakar, Senegal. The flight arrived at dawn. JKIA was alive nonetheless. I was walking in the midst of Africans and white foreigners when I arrived at some random check point mounted by the airport health team. They were looking for yellow fever certificates. Almost frantically. There was only one problem. Only Africans were being pulled aside for questioning about yellow fever vaccination certificates. I protested loudly at this glaring discrimination. This logic that decreed that only African looking people are thought to carry disproportionate risk of spreading infectious diseases. This disease and health politics so entrenched in international development. I protested in Swahili and received muted apologies. ���Sorry, we thought you were West African. Or Nigerian.�����This is why I take this special treatment at Bole International Airport seriously. It is rare, a good sign of things to come as African nations open their borders to each other. Kenya and South Africa have opened their borders to each other. East Africa to all East Africans. ECOWAS to their member nations.

Back in Addis, a taxi pulls up and I negotiate with Aaron, the taxi driver to guide me around the city. One of the attractions is the prime minister���s residence. We drive up the hill.

���The new prime minister is a good man,��� Aaron says between shifting gears. How? I ask.

���Because if you have something disturbing you in your chest, you say it freely and you do not go to jail.” He says. Freedom of speech. Ethiopian governments have had a dubious distinction for jailing journalists for speaking, for writing anything the regime does not like.

What of growth? I ask as we pass upcoming construction for hotels by the Hyatt and Marriot groups and other American brands. Things are getting better. Aaron says. But again, with people importing cheap twenty-five year old cars from junk yards in Dubai, it is hard to tell if enough money is circulating in this economy.

It is now 6 o’clock in the morning. Men and women are jogging up and down the well paved road leading to prime minister’s residence. Then I see it. The imposing building hidden behind high fences and paramilitary watch. I point at it excitedly. Aaron looks alarmed. He tells me to put my hands down.

“We get into trouble if soldiers see us.” He says. You just said things are different now. I tell remind him. I am confused. And become more aware of the camera on my lap.

Now, this country, proud and uncolonized, should do better than this. Ethiopia was indeed meant to be a great African experiment. Something we, Africans, could refer to when looking straight at the eyes of the British and say, “You see how great Ethiopia is doing?” ���Yes, this is how well we would be without you.” After all, we all know royal blood from ancient union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba flows freely here. But alas, wars, famine and strong men like President Meles Zenawi showed up and Ethiopia got stuck in this space, like a black and white photo of a poor family looking into the future, with an uncertain smile, and a lot of hope. There is always hope.

If only the new prime minister can build the national consciousness around peace and democracy, this nation can thrive. Or maybe not. Who knows? What is for sure, is that there is always a ghost of former strongmen shaping the fears of the new men and women in power.

July 22, 2019

Drones over Djibouti

Image credit Staff Sgt. Samuel Roger via Flickr (CC).

On August 7, 1998, simultaneous explosions at the American embassies in Nairobi and Dar-es-Salaam claimed the lives of 212 Kenyan and Tanzanian citizens; 12 Americans, mostly embassy staff, were killed, too. The bombs were hidden in cars driven by members of a small group of Muslim extremists called al-Qaeda. Already ten years old, it was led by three men: an engineer and ex-police officer named Mohammed Atef; a physician, Ayman al-Zawahiri; and Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden, a Saudi multimillionaire. Though they had met in Afghanistan in the CIA-backed mujahideen during the Soviet invasion, the men had since come to view the United States, bulwark of the House of Saud and staunch ally of Israel, as an existential threat to the Islamic revival they hoped to inspire.

Today, of course, we know the three as the architects of the September 11th hijackings in New York and Washington DC. In the twenty years since then, the United States has invaded three countries outright (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya), one more discreetly (Syria), and carried out low-profile tactical military operations���often without pretext���in countless others. These wars have spawned a vast network of bases, 4,800 by some counts, at a cost of anywhere from $85 to $100 billion a year. And the very idea of a war against “terror,” against an enemy neither definite nor definable, has inured the American public to war not as a discretely bounded event but instead as a continuous and continual state of being���one that has become indistinguishable from normalcy itself.

In 1998, most Americans knew nothing about al-Qaeda, Nairobi, or Dar-es-Salaam. History had ended; to them, war was a��few seconds of grainy night vision footage of missiles landing in Libya or Kosovo. Then the towers came down, and the Pentagon burned, and suddenly, the legions of fanatics ���sent to hide in countries around the world to plot evil and destruction��� were no longer treated like so much filmic hyperbole. America���s defense establishment seemed to leap into action, invading Afghanistan before the year was done. But that was because its preparations had begun much earlier���three years, one month, and four days earlier���set in motion by events thousands of miles away from Arlington and Fulton Street, in Nairobi and Dar-es-Salaam. As Newt Gingrich, Speaker of the House in 1998, put it in a speech to Congress while dust still hung over both embassies��� remains, ���[this] is a dangerous world as we enter the 21st century.���

The bombings were a revelation for US defense planners; it was clear that they had no grasp of the strategic realities of the post-Cold War world. Regions that had been of secondary or even tertiary importance in their eyes were now incubating effective resistance to American power projection. The African continent had been an almost deliberate blind spot; it never even merited a unified command, one of the coordinating bodies established after the Second World War to harmonize regional operations between all five branches of the military. These were meant to prevent balkanization, joining defense and intelligence assets together with traditional instruments of foreign policymaking. Africa, alone among continents, was passed around in chunks between commands, and sometimes not at all. By the beginning of the ���70s, most African countries were excluded from the unified command system completely. In 1983, the Department of Defense, realizing its oversight, finally assigned the lion���s share, including Tanzania, to US European Command (EUCOM). Egypt, Sudan, the Horn of Africa, and Kenya, however, went to US Central Command (CENTCOM), which handled the Middle East.

These jurisdictional divisions had a predictable effect on coordination between US agencies. Embassy officials in Nairobi were warned about a bomb threat several months in advance, by an informant who claimed to have had a hand in planning the attack. But the CIA station in Kenya deemed the source unreliable, and no permanent security measures were taken. That same informant then arrived in Tanzania and, according to local authorities, took part in the planning and execution of the bombing in Dar. His confession was never reported to embassy staff there.

The sting of the humiliation spurred defense planners to radically rethink their plans. So US Africa Command, or AFRICOM, was born. A decade in the making, after several more in absentia, it has more than made up for lost time. Today it is the second most expensive unified command after CENTCOM and the most active militarily by number of combat operations, with at least 30 publicly acknowledged since 2015. And as of last year, on the back of the Pentagon���s new National Defense Strategy sidelining the war on terror in favor of ���inter-state strategic competition,��� it finds itself at the center of force projection for a new era of American power.

Under Bush and then Obama, AFRICOM exemplified war-on-terror thinking, borrowing combat personnel from special operations forces like the Rangers and Green Berets. Few in number���a thousand at any one time���they were deployed on a brief, tactical basis, and always with low visibility. This last point has been especially important: the public has been deliberately kept in the dark about their activities. The foreign policy establishment is wary of being seen as colonialist���or was, until last year, when all that seemed to change.

As Thomas Waldhauser, AFRICOM���s commanding general since 2016, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in February, ���[What] we really need are some predictable general purpose forces that can do things with regular armies on a somewhat episodic but yet predictable basis.��� The measure of “predictability” here is the basis of deployment: in this case, the most “predictable” forces are those which are there for the long haul. His remarks came on the back of a Pentagon proposal to cut staff at all unified commands, AFRICOM included. Waldhauser agreed to the downsizing, with a large part of the cuts coming from combat personnel. But that was only because there was a bargain implicit in his assent: in exchange for giving up these special operators, AFRICOM wanted an open and abiding US military presence on the continent.

The committee, for its part, sympathized. Jim Inhofe (R-OK), who took over from John McCain as Chairman of Armed Services after the Arizona senator was diagnosed with brain cancer last year, suggested creating a ���Security Force Assistance Brigade��� or SFAB, dedicated solely to Africa. SFABs are a clever solution to the PR problems which are attendant on having boots on the ground. Officially classed as ���advisory units,��� they are in fact identical in composition and armament to a standard 800-person Army combat brigade.

Another issue that came up at the hearing was AFRICOM���s headquarters���currently in Europe, they are a logistical challenge to the command���s independence. Would they be moved onto the African continent, the committee asked? Inhofe, though aware of the rhetorical dangers ���perceived colonialism��� might have on the US���s reputation, was in favor of the idea. Waldhauser was more circumspect; he mentioned the possible logistical and technical challenges of moving out of Stuttgart, but was silent on its strategic implications. Still, he was open to debate.

The Bush administration had wanted AFRICOM to be headquartered in Africa, but backlash from African governments, and a lack of suitable facilities, forced the plan to be shelved. The world has moved on quite a bit in the decade since. As The Intercept and other outlets have reported over the past two years, the military is now spoiled for African real estate: at least 34 sites across the continent are under its direct supervision. One, at Agadez in Niger, is reported to have cost over $100 million, a price tag comparable to some of the fortified mega-bases the US operates in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But nowhere has the Pentagon invested more in guaranteeing ���predictability��� than in the Horn of Africa. Even as the new National Defense Strategy admitted that terrorist groups ���might not necessarily be a risk to the homeland,��� Vice reported last year that the military was adding 800 beds to its Baledogle base in Somalia, as well as building six new facilities inside the country. These are meant to accommodate the estimated 500 US special operations troops who are now on active deployment in Somalia, a dramatic increase from the meager 50 that AFRICOM acknowledged just two years ago.

But it is at Camp Lemonnier, a few minutes’ drive from Djibouti City, that the scale of America���s military investment in Africa is most viscerally and visibly felt. Lemonnier is for all intents and purposes detached from the country surrounding it: US personnel are forbidden to leave the base without special permission. 88 acres when it was first leased by Bush���s administration in 2001, today it has swelled to over 600, hosting both the Combined Joint Task Force ��� Horn of Africa and Special Operations Command (Forward) ��� East Africa. With 4,000 military personnel and private contractors, it is the largest US military base in Africa and among the largest in the world. It has also spawned a second base at nearby Chabelley Airfield, with one of the world���s biggest drone operations���deployed, most recently and most infamously, in support of the horrific Saudi-led invasion of Yemen.

All of this manpower and material is said to be part of an aggressive war against al-Shabaab, a radical religious militia whose aim is to reconstitute Somalia as an Islamic state. One wonders if Somalian instability really demands such expensive attention. Piracy is a persistent problem, and both Kenya and Ethiopia, staunch American allies with large Muslim populations and non-Muslim governments, have no interest in having a radical Islamic state across their borders. But these are important regional considerations, not supra-regional ones. It���s been twenty years since Nairobi and Dar; even the war in Yemen will eventually end. The logic of Lemonnier lies elsewhere.

Djibouti happens to lie on one side of the Bab el-Mandeb, the straits that control entrance to the Red Sea. Anywhere from 12 to 20 percent of world trade passes by it every year, including 5 million barrels of oil a day. With less than a million inhabitants, the straits have nevertheless allowed Djibouti to take on an outsized role in regional diplomacy. The French, Italians, and the Japanese have their own bases in or near the capital���and, as of 2017, the People���s Republic of China does, too. It opened its first overseas military facility in the world near the port of Doraleh northwest of Djibouti City���and right on the Bab el-Mandeb, too.

The Chinese state has invested heavily in soft-power projection over the past two decades, and nowhere more so than in Africa. Twelve percent of the continent���s industrial production now flows through Chinese businesses, and the PRC has signed more than $500 billion in new construction and procurement contracts with African governments since 2013. It has spent generously on its Doraleh facility, too: $590 million by some estimates, and is negotiating for exclusive use of the port after Djibouti���s government seized control of it from Dubai-based DP World.

The National Defense Strategy calls out China specifically for being a ���strategic competitor��� whose ���military modernization��� and ���predatory economics��� are intended ���to achieve global preeminence��� at the expense of the United States. In prepared statements, however, the Pentagon has been more cautious about linking its African expansion to a policy of Chinese containment. ���At this point in time, it���s too early to make that leap,��� Waldhauser told the Armed Services Committee when asked if Doraleh signaled a shift from soft- to hard-power diplomacy on China���s part. But, he added, ���Djibouti is not the first, and it won���t be the last port.���

That national defense planners have responded to Chinese trade diplomacy with further militarization should surprise no one. It is a logical consequence of two decades of militarizing American foreign policy. In Africa, there are now seven Department of Defense employees for every one US government civilian; the majority of US officials interfacing with African governments are attached to the National Security Administration. In practice, this means that the military has taken over roles it is not supposed to play, and it is unlikely to relinquish them any time soon.

Speaking to the Heritage Foundation last December, John Bolton, Trump���s National Security Advisor, was candid in this regard. After announcing a new round of aid and investment, ���Prosper Africa,��� promising soft-power projection through increased “transparency” and “cooperation,” Bolton got down to brass tacks. ���[T]his is a very important point for the US and the West as a whole to wake up [to],��� he said; if Djibouti leased the port to the PRC, ���the balance of power in the Horn of Africa, a major artery of maritime trade between Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia would shift in favor of China.��� Echoes here of Gingrich���s “dangerous world.” We should be under no illusions as to what this kind of talk means, and neither from a man with Bolton���s career. The race to win America���s place in the sun is on, and men like him and Gingrich, men for whom career and conflict are hopelessly blurred, do not intend to be left in the shade.

Mozambique is a Dutch business

[image error]

Girl in Ilha Mozambique. Image credit St��phane Neckebrock via Flickr (CC).

In Mozambique, about half of the 29.7 million inhabitants are living under the official poverty line, many of them as impoverished farmers. After decades of above-average growth (compared to other sub-Saharan economies), about 80 percent of Mozambicans work in agriculture. It���s a sector which successive governments���from the Portuguese colonizers to the democratically elected Frelimo���have historically failed to develop, experts explain. Instead, they focused on developing profitable, capital-intensive “mega-projects” in the extractive sector, in which foreign investors were more than willing to invest. Mozambique exports coal, aluminium, and gas���soon, much more of the latter as foreign companies plan to develop a massive gas field discovered off the country���s coast in 2011.

The country is also no stranger to natural disasters���and global climate change is making the storms more frequent and severe. The latest hurricanes���Idai in March and Kenneth in April���flooded the port city of Beira and the northern province Cabo Delgado, killing hundreds. The lack of public funds to develop decent drainage systems and coastal protection around Beira were painfully visible in the pictures of the city in the aftermath of Idai.

A business approach to aid

The Netherlands has been active in Mozambique for decades, spending, in recent years, about ���30 million of its annual development budget on rural development, water projects in the Southern African country. The Dutch offer expertise to address challenges for Mozambique that are similar in nature to those The Netherlands has experienced in the past, such as Dutch disease���the negative economic consequences from large-scale gas exports on other sectors in the economy���and threats to low lying areas from rising seas.

The Dutch also contribute via companies which have an increased interest in Mozambique since the discovery of its massive offshore gas field. For example, the Dutch oil and gas company Shell is planning the construction of a gas to liquid (GTL) plant in Mozambique, a mega project worth a possible $5 billion dollars. Heineken has predicted increased demand for beer in Mozambique and is constructing a new brewery, an investment worth about $96 million. Development aid and promoting the foreign interests of Dutch businesses are seen to reinforce each other. Since 2012, aid and trade policies now fall under the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation.

This trend has been criticized from the start by development experts and NGOs, with the effects on the ground in Mozambique also raising concerns. Internal documents obtained through a freedom of information act request by Platform Authentieke Journalistiek (PAJ) and described in one of its reports, revealed that the Dutch embassy in Maputo cooperated with and lobbied in favor of Shell before it won a public tender in 2017 for the construction of a GTL plant. One of the documents is a thank you note to the Dutch Ambassador, Pascalle Grotenhuis, sent on December 4th, 2015, ending with: ���Your dedication to trade and investment opportunities in Mozambique has been of immeasurable value to our activities and the future of our project.���

Another report of PAJ outlines concerns over land grabbing in the zone where gas companies plan to build onshore facilities, including where Shell���s plant is to be built. Other companies have also been cited for dubious practices in this regard. Anadarko, a US gas company, has been sued by Mozambican lawyers for illegally expropriating land. Mozambicans interviewed by the Dutch NGO Milieudefensie indicate that Shell misled people into signing agreements about land and relocations. The internal documents also reveal that the Dutch government lobbied the Mozambican state for a bilateral tax break that would be favorable for Shell and other Dutch companies.

Beira master plan 2035

As experts in water management, the Dutch are intensively involved in development plans around the port city of Beira, recently flooded and destroyed by hurricane Idai. The ���Beira Master Plan 2035��� was developed in 2012 by a coalition of Dutch public and private players. Its aim is, on paper, to protect all citizens of Beira, rich and poor, against the storms and floods, through coastal protection and housing projects on higher, safer lands.

However, as the latest PAJ report describes, the plan is in fact a collection of business plans for which investors are yet to be found. As an internal document from the Netherlands Enterprise Agency from 2016 notes, the master plan would provide ���multiple opportunities for the Dutch business community.��� Yet, to date, very little of the plan has been realized, as Peter Letitre���a representative of Deltares, one of the institutes designing the masterplan���explained. It has been particularly difficult to find investors for coastal protection as it ���limits damage, but does not generate income.���

The housing project included in the plan has also been criticized, for serving wealthier Mozambicans. As the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) wrote in a 2018 report: ���On paper the plan is aimed at all the city���s inhabitants��� However, the road layout and plot sizes lead us to suspect that ultimately the richer middle classes will be the ones who have the money to build homes in this new plan.���

The authors are part of the Platform Authentieke Journalistiek and the article was first commissioned by Down to Earth Magazine��in conjunction with Follow the Money. This publication came about with the support of Both ENDS��and the Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten.

Poverty, inequality and virtuousness in South Africa

Image credit Lorenia via Flickr (CC).

Nkosikho Mbele is a petrol attendant at a Shell garage located on the N2 highway, near Makhaza in the Western Cape. No one would have noticed him until local news site, News24, reported on 28 May 2019 that Mbele had paid R100 (about US$8) of his own money to cover a customer, Monet van Deventer���s petrol bill. She had forgotten her bank cards at home. In response to Mbele���s kindness, Van Deventer set up a fundraising campaign to raise R100,000 to go to Mbele���s benefit.