Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 211

July 20, 2019

Zionism and global African studies

Oxford University. Image credit hnphotog via Flickr (CC).

On June 27 and 28 of this year, we attended a conference titled ���Racialization and Publicness in Africa and the African Diaspora,��� hosted by Oxford University���s Africa Studies Center and their School of Global and Area Studies. The conference was held to ���address the contemporary problem of racialization in Africa and the African Diaspora.��� Organizers wanted to explore how ���people of African descent are racialized��� [and] why and how racial identities and categories are constructed, imagined and inscribed (in)to the social, political and economic processes, practices and relationships in Africa and the African Diaspora.���

Instead, an international academic conference on Global Africa was co-opted into a project to legitimize the settler-colonial, apartheid state of Israel and ���black-wash��� its racist policies and practices. As such, and in light of Israel���s ongoing attempts to normalize its relations with African states in coordination with US imperialism, while ingratiating itself to African diaspora communities, we want to sound a warning to future Black Studies and African Studies conference organizers who may encounter similar tactics by Zionist organizations.

In the original call for papers, conference organizers used the languages of anti-racism, anti-colonialism, Pan-Africanism, and intersectionality. They invoked the murder of Trayvon Martin and the UK���s unlawful detention and deportations of members of the Windrush generation, and they referenced the work of radical black intellectuals including W.E.B. Du Bois and Frantz Fanon. The conference���s 12 panels were to be anchored by keynotes from anthropologist Faye V. Harrison and philosopher Achille Mbembe (Mbembe was unable to attend).

Of the 12 panels, two were listed under one title (as Part 1 and Part 2): ���Notions of Diaspora and Homeland: The Impact of the Contemporary Emergence of Racism(s), Antisemitism(s), Nationalism(s) and White Supremacy in the Age of Globalization.��� At first glance, the collective title appeared innocuous. It seemed properly scholarly, if slightly outdated, and appeared to fall within the expressed themes of the conference. Yet a closer look at the make-up of the panels revealed some surprising things.

Both panels were organized by a group called the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy (ISGAP)���an advocacy body, not an academic organization. It was founded by Charles Asher Small, a Canadian without a permanent academic position who holds a degree from St. Anthony���s College, Oxford. In a 2019 interview, Small described ISGAP as ���an intellectual grassroots movement within the academy��� whose main aims include fighting the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, a movement Small has equated with anti-Semitism. The ISGAP works by ���conducting strategic research and providing intelligence��� in order to ���influence future generations of policymakers, scholars and community leaders.”

Whereas other Zionist organizations have used lawfare and blacklisting to dampen Palestine solidarity on university campuses, the strategy adopted by ISGAP appears to be somewhat different. On one hand, their approach is one of targeting of scholarly spaces and appropriation of academic language. On the other they aim to incite dissent and strife within academic circles for the purposes of self-promotion and publicity, using the banner of ���academic free speech��� as a bludgeon against critique.

The ISGAP panelists at the Oxford conference formed a strange unit. Their panelists included a Likud Party member of the Israeli Knesset, a clinical psychologist and ISGAP board member who had never written on Africa, a Grinnell college anthropologist interested in ���double consciousness��� and Israeli diversity, a Tel Aviv University political scientist, as well as Charles Small himself. Many of the presenters on the two ISGAP panels were from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the United States. They included Harold V. Bennett of Morehouse, Valerie Ann Johnson of Bennett College, Carlton Long, an educational consultant formerly of Morehouse, and Ansel Brown of North Carolina Central University. Brown took over the entire time allotted to the first ISGAP panel with a fifty-minute presentation titled ���Zionism and Pan-Africanism: A Common Journey to Recapture Ethnic Self-Realization.���

The HBCU connection is important. In recent years, the right-wing American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) has been recruiting at Black colleges, targeting students and faculty interested in international politics. The AIPAC has sponsored travel to Washington DC to meet with politicians who are supporters of Israel, and provided all-expenses paid trips to Israel. Its aim is to cultivate sympathy for Zionism while driving a wedge between Black and Palestinian liberation��struggles.

Even before the ISGAP panels began, many conference participants expressed concern about their inclusion in the program. They were disturbed by the connections asserted between Israel, a state founded on ethnic cleansing and the dehumanization and dispossession of the indigenous Palestinian population, and the radical histories of Pan-Africanism. And they were surprised and troubled by the prominence given to this view by the conference organizers. Many conference participants discussed how the ISGAP-sponsored panels appeared to be designed to disrupt the proceedings, mirroring what was seen at previous conferences, especially when it came to questions of BDS.

In response, the conference participants demanded a public conversation with the organizers in order to discuss the Oxford African Studies Centre���s relationship to ISGAP. But our questions and concerns were met with redirection, and in some cases a dismissive mirth, and we were frankly surprised by the unwillingness to have an open conversation. Meanwhile, some ISGAP-affiliated participants attempted to squelch our inquiries by alleging that our concerns were encouraging anti-Semitism, racism, and, ironically, denying ���freedom of expression.���

On the second day of the conference, a number of conference participants ceded their presentation time, allowing us the opportunity to meet to discuss our concerns. A majority of conference participants attended the meeting during which they expressed relief that we were able to come together as a collective, especially since academic settings often encourage isolation, atomization, and alienation. Collectively, we drafted a statement disassociating ourselves from ISGAP, and we asked that the Oxford���s African Studies Centre post our statement on their website. The Centre refused to do so. Instead, the leadership of the Centre released its own statement, denying any connection to ISGAP while asserting a commitment to free intellectual exchange.

We strongly believe that part of the African Studies Centre���s response was to mitigate the fact that so many conference participants were disturbed by ISGAP���s prominent presence. To this end, it was even suggested by some conference organizers that one prominent senior male scholar had spearheaded this protest.

This was not the case. Indeed, despite the efforts of the organizers, as a group we had spontaneously taken over the conference and turned it into a collective, self-organized, multi-generational forum for political education, each of us learning and making new calculations and interventions in response to the pushback from the African Studies Centre and ISGAP affiliates. Our collectively-written response was posted on the website of the Frantz Fanon Foundation on July 4, 2019.

To be sure, there was some anxiety expressed about the collective statement. Some participants worried that if we made our concerns public, we would implicate the Oxford African Studies Centre, which would have a grave impact on efforts to diversify the university. Indeed, ISGAP���s Charles Small, who sat in the audience observing our deliberations, suggested that we not do anything that could jeopardize the position of the Center���s director (Oxford���s first Black Rhodes Professor), whom he described as an old friend.

We worried about the potential backlash from Oxford and elsewhere to those graduate students and untenured faculty who wanted to lend their voices in support. A number of senior faculty were concerned about reprisal, and one scholar, who at the last minute asked for their name to be removed from the statement, encouraged us to ���acknowledge the atmosphere of intimidation and fear fostered throughout this process.”

But in the end, for the signatories (and for many who expressed support, but felt they could not sign), there was a sense that we could not let the study of Global Africa be hijacked by a Zionist lobbying group. We also could not support the defamation and desecration of the history of pan-Africanism by academic charlatans and agents of a racist, settler-colonial��state.

The organized attempt by ISGAP to influence the conference was little more than a continuation of Zionist racism, dressed up in the finery of academic language and, in particular, the staid gowns of Oxford. But we should note its significance and understand that such efforts will be repeated again.

If we are to maintain the political and intellectual integrity of the study of Global Africa, we must be wary of such campaigns in the future���and we need to continue to strengthen and renew the connections between struggles against neocolonialism, racial capitalism, and imperialism across the globe in order to combat them.

Zionism and the infiltration of global African studies

Oxford University. Image credit hnphotog via Flickr (CC).

On June 27 and 28 of this year, we attended a conference titled ���Racialization and Publicness in Africa and the African Diaspora,��� hosted by Oxford University���s Africa Studies Center and their School of Global and Area Studies. The conference was held to ���address the contemporary problem of racialization in Africa and the African Diaspora.��� Organizers wanted to explore how ���people of African descent are racialized��� [and] why and how racial identities and categories are constructed, imagined and inscribed (in)to the social, political and economic processes, practices and relationships in Africa and the African Diaspora.���

Instead, an international academic conference on Global Africa was co-opted into a project to legitimize the settler-colonial, apartheid state of Israel and ���black-wash��� its racist policies and practices. As such, and in light of Israel���s ongoing attempts to normalize its relations with African states in coordination with US imperialism, while ingratiating itself to African diaspora communities, we want to sound a warning to future Black Studies and African Studies conference organizers who may encounter similar tactics by Zionist organizations.

In the original call for papers, conference organizers used the languages of anti-racism, anti-colonialism, Pan-Africanism, and intersectionality. They invoked the murder of Trayvon Martin and the UK���s unlawful detention and deportations of members of the Windrush generation, and they referenced the work of radical black intellectuals including W.E.B. Du Bois and Frantz Fanon. The conference���s 12 panels were to be anchored by keynotes from anthropologist Faye V. Harrison and philosopher Achille Mbembe (Mbembe was unable to attend).

Of the 12 panels, two were listed under one title (as Part 1 and Part 2): ���Notions of Diaspora and Homeland: The Impact of the Contemporary Emergence of Racism(s), Antisemitism(s), Nationalism(s) and White Supremacy in the Age of Globalization.��� At first glance, the collective title appeared innocuous. It seemed properly scholarly, if slightly outdated, and appeared to fall within the expressed themes of the conference. Yet a closer look at the make-up of the panels revealed some surprising things.

Both panels were organized by a group called the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy (ISGAP���an advocacy body, not an academic organization. It was founded by Charles Asher Small, a Canadian without a permanent academic position who holds a degree from St. Anthony���s College, Oxford. In a 2019 interview, Small described ISGAP as ���an intellectual grassroots movement within the academy��� whose main aims include fighting the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, a movement Small has equated with anti-Semitism. The ISGAP works by ���conducting strategic research and providing intelligence��� in order to ���influence future generations of policymakers, scholars and community leaders.”

Whereas other Zionist organizations have used lawfare and blacklisting to dampen Palestine solidarity on university campuses, the strategy adopted by ISGAP appears to be somewhat different. On one hand, their approach is one of infiltration of scholarly spaces and appropriation of academic language. On the other they aim to incite dissent and strife within academic circles for the purposes of self-promotion and publicity, using the banner of ���academic free speech��� as a bludgeon against critique.

The ISGAP panelists at the Oxford conference formed a strange unit. Their panelists included a Likud Party member of the Israeli Knesset, a clinical psychologist and ISGAP board member who had never written on Africa, a Grinnell college anthropologist interested in ���double consciousness��� and Israeli diversity, a Tel Aviv University political scientist, as well as Charles Small himself. Many of the presenters on the two ISGAP panels were from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the United States. They included Harold V. Bennett of Morehouse, Valerie Ann Johnson of Bennett College, Carlton Long, an educational consultant formerly of Morehouse, and Ansel Brown of North Carolina Central University. Brown took over the entire time allotted to the first ISGAP panel with a fifty-minute presentation titled ���Zionism and Pan-Africanism: A Common Journey to Recapture Ethnic Self-Realization.���

The HBCU connection is important. In recent years, the right-wing American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) has been recruiting at Black colleges, targeting students and faculty interested in international politics. The AIPAC has sponsored travel to Washington DC to meet with politicians who are supporters of Israel, and provided all-expenses paid trips to Israel. Its aim is to cultivate sympathy for Zionism while driving a wedge between Black and Palestinian liberation��struggles.

Even before the ISGAP panels began, many conference participants expressed concern about their inclusion in the program. They were disturbed by the connections asserted between Israel, a state founded on ethnic cleansing and the dehumanization and dispossession of the indigenous Palestinian population, and the radical histories of Pan-Africanism. And they were surprised and troubled by the prominence given to this view by the conference organizers. Many conference participants discussed how the ISGAP-sponsored panels appeared to be designed to infiltrate and disrupt the proceedings, mirroring what was seen at previous conferences, especially when it came to questions of BDS.

In response, the conference participants demanded a public conversation with the organizers in order to discuss the Oxford African Studies Centre���s relationship to ISGAP. But our questions and concerns were met with redirection, and in some cases a dismissive mirth, and we were frankly surprised by the unwillingness to have an open conversation. Meanwhile, some ISGAP-affiliated participants attempted to squelch our inquiries by alleging that our concerns were encouraging anti-Semitism, racism, and, ironically, denying ���freedom of expression.���

On the second day of the conference, a number of conference participants ceded their presentation time, allowing us the opportunity to meet to discuss our concerns. A majority of conference participants attended the meeting during which they expressed relief that we were able to come together as a collective, especially since academic settings often encourage isolation, atomization, and alienation. Collectively, we drafted a statement disassociating ourselves from ISGAP, and we asked that the Oxford���s African Studies Centre post our statement on their website. The Centre refused to do so. Instead, the leadership of the Centre released its own statement, denying any connection to ISGAP while asserting a commitment to free intellectual exchange.

We strongly believe that part of the African Studies Centre���s response was to mitigate the fact that so many conference participants were disturbed by ISGAP���s prominent presence. To this end, it was even suggested by some conference organizers that one prominent senior male scholar had spearheaded this protest.

This was not the case. Indeed, despite the efforts of the organizers, as a group we had spontaneously taken over the conference and turned it into a collective, self-organized, multi-generational forum for political education, each of us learning and making new calculations and interventions in response to the pushback from the African Studies Centre and ISGAP affiliates. Our collectively-written response was posted on the website of the Frantz Fanon Foundation on July 4, 2019.

To be sure, there was some anxiety expressed about the collective statement. Some participants worried that if we made our concerns public, we would implicate the Oxford African Studies Centre, which would have a grave impact on efforts to diversify the university. Indeed, ISGAP���s Charles Small, who sat in the audience observing our deliberations, suggested that we not do anything that could jeopardize the position of the Center���s director (Oxford���s first Black Rhodes Professor), who he described as an old friend.

We worried about the potential backlash from Oxford and elsewhere to those graduate students and untenured faculty who wanted to lend their voices in support. A number of senior faculty were concerned about reprisal, and one scholar, who at the last minute asked for their name to be removed from the statement, encouraged us to ���acknowledge the atmosphere of intimidation and fear fostered throughout this process.”

But in the end, for the signatories (and for many who expressed support, but felt they could not sign), there was a sense that we could not let the study of Global Africa be hijacked by Zionists. We also could not support the defamation and desecration of the history of pan-Africanism by academic charlatans and agents of a racist, settler-colonial��state.

The infiltration of the conference by ISGAP was little more than a continuation of Zionist racism, dressed up in the finery of academic language and, in particular, the staid gowns of Oxford. But we should note its significance and understand that such infiltrations will happen again.

If we are to maintain the political and intellectual integrity of the study of Global Africa, we must be wary of such infiltrations in the future���and we need to continue to strengthen and renew the connections between struggles against neocolonialism, racial capitalism, and imperialism across the globe in order to combat them.

July 19, 2019

Fanon forever

Image Credit Leo Zeilig (I B Tauris or HSRC Press -

South Africa)

The restoration of power to people, the Arab spring, peaceful regime change, the Arab spring 2.0 or whatever might be the new nomenclature used or the latest twitter hashtags introduced, this transcendental need for a genuine experience of liberation continues to find its meaningful impulse in the life and writings of Frantz Fanon. The psychiatrist and anti-colonial theorist who, through his experiences with European anti-black racism and French colonialism in Algeria, has become the anti-colonial thinker and activist par excellence, in his time and ours.

In his first documentary, Fanon: yesterday, today, Hassane Mezine renews our attention to the historical and political project of freedom, humanism, and justice central to Fanon���s life and work. Mezine, a Franco-Algerian and a photographer by training, interweaves a polyvocal, at times conventional, view of Fanon���s life and work with an overlooked materialist analysis of Fanon���s legacy. His film offers a timely and sweeping re-presentation of Fanon���s philosophy and its contemporary relevance through a journey into the personal and political dimensions of his life, and the influence his ideas continue to have on new generations of readers and activists around the world.

Mezine���s documentary opens in an unexpected way, the voice of Nicolas Sarkozy, the former French president, delivering his statement on the ���tragedy of Africa��� during his 2007 Dakar speech, highlighting that the racist and dehumanizing discourse of a neocolonial Europe is pervasive. To counter the degrading undertones of Sarkozy���s blatant attack, a succession of archival footage of chained bodies, mutilated corpses, and severed heads offers a visual emphasis on the terrible legacy of French colonialism in Algeria. This visual dissonance pre-empts Fanon���s intervention through an audio recording of his 1956 speech on ���Racism and Culture,��� and suggests Mezine���s interest in disrupting the continuity of neocolonial discourses and institutions through the use of Fanon���s philosophy of revolutionary struggle. Since discursive violence is the late performance of colonial physical violence, there is an urgency to re-appropriate Fanon���s critical, fightback commitments today.

For Mezine, Fanon is a timeless and relevant thinker and activist because his experience of racism and neocolonialism continues to shape how the African is viewed and framed. In the film, the subversive materiality of Fanon���s enduring legacy illuminates the present struggle against neocolonialism because it articulates violence, alienation, and discrimination as a material and political reality. To challenge the moral and political catastrophe, we still need Fanon���s humanism and fightback ideology.

Mezine���s documentary announces its methodology right from the title, the timelessness of Fanon���s work and legacy is presented through the recollections of those who encountered the Fanon of yesterday in Martinique, Algeria, Tunisia, and Mali, and also during our time through diasporic activists and writers, in Palestine, Portugal Unites States and Niger who continue to celebrate and live by his philosophy and ideals today. Fanon: yesterday, today juxtaposes conventional footage and selected readings from Fanon���s Black Skin, White Masks, A Dying Colonialism, and The Wretched of the Earth with an impressive number of diasporic encounters, which insist that Fanon���s liberation theory is timeless because we are still struggling with the same ideologies and structures of exclusion and dehumanization.

Fanon in time

Fanon was a man of his time���an exceptionally revolutionary time. Through still photographs of Fanon���and interviews with his son Olivier, Abdelhamid Mehri, the minister of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (PGAR) in Tunisia, and Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, his assistant in the general hospital in Tunis���the first part of Mezine���s documentary starts with the major events that marked Fanon���s transition from an eighteen-year-old Martiniquais soldier serving with French troops during WWII, to his early disillusionment with racial politics, which later influenced his writings on colonial ideology of racism and domination, which was pervasive among the political, academic, and institutional apparatuses of French colonialism.

In Fanon: yesterday, today, we are reminded that Fanon was not only a brilliant writer and theorist, but also an innovative psychiatrist. He developed new treatments at the Hospital of Blida-Jointville to challenge the racist theories of the Algiers School of Psychiatry, established by the French psychiatrist Antoine Poirot and taught in France till the 1970s. These stipulated that the North African is a pathological liar and that the Black African is a lazy, primitive subject. Fanon also adopted the new methods of institutional psychotherapy to dismantle the inherited structural racism he encountered at Blida hospital.

The events of November 1954 and the beginning of the armed struggle against the French colonizers marked a decisive moment in Fanon���s transition from a radical psychiatrist to a fightback militant. It explores his appointments as a PGAR representative in Modibo Keita���s Mali and later in Kwame Nkrumah���s Ghana, his encounters with the African intellectual diaspora in Paris and Rome, and his disenchantment with impure, unfinished independence in Houphouet-Boigny���s Ivory Coast (and to some extent in Habib Bourguiba���s Tunisia), gradually transformed him to an iconic figure of African liberation and Third World revolutions.

Fanon was also a Tunisian, through and through. His thoughts on decolonization and his disillusionment with the national bourgeoisie in A Dying Colonialism were influenced by his experience in post-independence Tunisia during the early days of Bourguiba���s rule, along with encounters with the Tunisian bourgeoisie. It was in Tunisia, I think, that his transformation into the revolutionary thinker started.

In Fanon: yesterday, today, time and again, Fanon appears as a larger-than-life figure who passionately and seriously engaged with the Algerian struggle, but also enjoyed being invited to parties and showed compassion, generosity, and sensibility. As biographer Alice Cherki remembers, ���Fanon loved to talk with people who commanded his admiration, or simply with friends, and while his brilliant eloquence was riveting, he was also quite capable of being a generous and sympathetic listener. He was an excellent conversationalist, who never spoke openly about himself.���

Mezine���s ability to offer interventions from such central figures as Olivier Fanon, Abdelhamid Mehri, Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, Arnoldo Palacios, Lilyan Kesteloot, and his nod to Josie Fanon as Fanon���s spouse, muse, and comrade, are commendable in providing a compelling and nuanced account of Fanon���s life and personality. However, when presenting bibliographic information about Fanon���s death, Mezine rehearses the conventional version of his last days. The film would have benefitted from a deeper investigation of the relationship between American secret services (CIA) and the under-reported account of Fanon���s death to shed more light on what could have possibly been a political assassination. This is especially important when we take into consideration Fanon���s long meditation of the human experience in the face of annihilation and how, before his death, he wanted to write a book on death and dying. This is one of the reasons why every time I read Macey���s observation that ���there is nothing particularly shocking about an intelligence agency���s attempt to use him [as a potential asset]��� (487 my emphasis), I become more aware that his biography should not be the definitive one on Fanon���s life and work. Fanon���s death at age of 36 left many chambers open.

Despite these abstractions, Fanon���s legacy continues to make a difference. His philosophy of universal humanism and revolutionary solidarity transcends his time and offers a genuine materiality and imaginary of freedom that continues to inspire new generations of dreamers and fighters against neocolonial injustice and nihilism. In the words of Houria Bouteldja, one of the activists interviewed in the documentary and a member of the Party of the Indigenous of the Republic (PIR) in France, ���Fanon left us a legacy, and I feel like his heir. As simple as that.���

Fanon in motion

The contemporary relevance of Fanon���s life and work and the radical vision of his ideas and fightback militancy across a wide range of engagements, understandings, and practices find resonance in Mezine���s film. While the intellectual dimension of Fanon���s work is widely celebrated in academic and theoretical works, the materialist dimension of his political project continues to be overlooked. Mezine offers to ground Fanon���s internationalism in the appropriation of his thoughts by a variety of activists and thinkers, such as the Martiniquais writer Rapha��l Confiant, the activist and chair of the Black History Month in France Maboula Soumahoro, and the Palestinian psychiatrist Samah Jabr, to confront and resist neocolonial forms of exploitation and violence.

Two of the strongest and persuasive contributions in highlighting the pervasive influence of Fanon���s vision on today���s activism in Fanon: yesterday, today come first from Cornel West. It is worth being quoted at length:

Much of the world remains pre-Fanonian, but we will catch up with Frantz Fanon because many of us have decided that we want to be faithful until death to his truth telling, to his witness bearing in the face of the CIAs of the world, in the face of the FBIs of the world, in the face of nation-states being in France, England. It is a human affair, and given the impending ecological catastrophe, the escalating nuclear catastrophe, the corporate greed running amok transnational, the trans-specific partnerships reshaping the whole world in the corporate���s interest and image, the moral catastrophe of our mass culture that ties us to the instant gratification and bodily stimulation rather than a nurturing of heart, mind, soul and body to be truth tellers and to be willing to organize and mobilize in the face of a substantial conception of freedom, the spiritual catastrophe, the spiritual blackouts, the spiritual suicide trying to convince those everyday people to give up or to cave in, or for professional classes no matter what color to sell their souls for a massive potage, I thank god as a revolutionary Christian that Frantz Fanon was not a polished or smart professional, but rather a love and intellectual warrior in organic connections with the struggles of the wretched of the earth.

For West, Fanon is the transcendental face of the freedom struggle; the pervasive experiences of dehumanization and alienation calls into practice Fanon���s ideas of revolutionary consciousness, resistance, and invention of new humanism.

West���s commentary on the visual identity of Fanon resonates with Mezine���s film; Fanon yesterday, today is not a polished or smart professional film. Financed through a crowdfunding campaign, his documentary supplants sophisticated cinematic visuals with the gravity of the “real” and the plasticity of Fanonian interventions into the personal, the symbolic, and the political. There is no stylish backgrounds or slick graphics and the seamless economy of the movie is loosely created through the repetitive aesthetics of direct quotations, straightforward interview, and traditional animation. Mezine���s film doesn���t overwhelm; it never reaches a culmination, but it stirs our consciousness by the force of its iconic protagonist.

Salima Ghezali, one of the most charismatic interviewees, delivers a powerful insight on how Fanon continues to be misread and the need to save him from his critics. Ghezali, an Algerian writer and journalist, notes that Fanon ���is not present where he is being celebrated.��� In a moment of superb intimation, she notes, with a smirk on her face, the absurdity and ���sacrilege��� of celebrating Fanon and Albert Camus together. Despite Fanon���s iconic dimension, there is a persistence of anachronistic accounts and readings of his ideas and arguments as ���passionate,��� ���romantic and idealistic.��� There is a revisionist attempt to dissolve Fanon���s anti-colonial, confrontational positions into textual activism. It is like ���trying to take hip hop and make [it] r&b … or funk.��� Even worse, just a few years ago, one postcolonial scholar noted that I should not use the verb ���theorize��� when analyzing the writings of Fanon.

It is important of course to acknowledge that his life and work are bound by the contradictions and pressures of his time; however, Fanon���s work needs to be rediscovered, re-historicized, and especially saved from textualism. Let me put in a bold way: It is not enough to read Fanon���s books; it has to be explained to you the same way Marx���s work has to be clarified to avoid misconceptions and unnecessary abstractions. What needs to be fundamentally understood is that for Fanon and Marx the point is not just to interpret the world, but to change it. It is urgent in this sense, as Benita Parry argues, to delink Fanon���s theory from the poststructuralism of Homi Bhabha and the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre and to re-read Fanon���s philosophy within a materialist framework.

For Ghezali, Fanon���s rejection of the African bourgeoisie that highjacked the ideals of the Algerian revolution remains relevant because the national bourgeoisie has reproduced the racial and economic forms of neocolonial domination. This is especially visible in ���the refusal to build a social Algerian state��� and the racial discrimination against ���our brothers,��� black sub-Saharan Africans.

Mezine brings together different encounters with Fanon around his life and ideas and their relevance to the understanding of complex issues in his time and ours. Fanon yesterday, today departs from academic and at times theoretical interpretations that come to confine artistic work on the author of the Wretched of the Earth to a visual essay. This includes Aloysio Raulino���s fifteen-minute musing on Fanon���s Black Skin, White Mask in O Tigre e a Gazela (Brasil 1976), Isaac Julien���s classic docudrama��Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask (1995) and his emphasis on identity politics, Cheikh Djema�����s heavily bibliographic film on Fanon���s rising into a revolutionary figure in Frantz Fanon, His Life, His Struggle, His Work (2011), and recently G��ran Olsson���s Concerning Violence and his visual study of Fanon���s widely-analyzed eponymous text on the relationship between violence and decolonization. Mezine���s documentary contributes to these projects by fostering our understanding that the personal is political in Fanon���s life and that a genuine engagement with Fanon as a timeless figure requires aims to generate a materialist articulation of resistance and revolution.

In Fanon yesterday, today, there is an explicit suggestion to reconsider the relevance of Fanon���s work and to urgently re-appropriate it to our neocolonial condition. While it is mostly conventional in its chronological structure and interview-based visuals, his documentary offers a sustained engagement with Fanon���s life and legacy by fostering our understanding of his revolutionary time while inviting reflection on the multiple adaptations of his liberation vision of a better tomorrow in our present time. For Mezine and for many of us, Fanon remains ���the legend, a hard act to follow.���

Neoliberalism and the march of impunity in Equatorial Guinea

President Teodoro Obiang at a South Korea summit. Image credit The Embassy of Equatorial Guinea via Flickr (CC).

On 31 May 2019, one hundred and twelve Equatoguineans and foreign nationals were sentenced in Equatorial Guinea for several crimes against the state related to the alleged coup plot of December 2017. Three of the convicts were key dissident figures, and were given 96-year sentences in absentia. The regime���s crackdown, led by the longest-serving republican head of state in the world, drew harsh criticism from NGOs and western governments alike. But even as opposition members were languishing���and likely being tortured���at the Playa Negra Prison, the ���luxurious��� Sipopo Conference Center (just 15 kilometers away), was hosting the AfDB���s flagship event featuring 3000 public, private, and civil society delegates from across the continent. Meanwhile, the IMF was considering extending a generous loan package in return for EG���s good-faith adherence to the EITI���s standards. How exactly has the regime avoided harsh criticism to remain one of the most improbably successful autocracies in the world?

Oil is the simplest and most proffered answer. When Equatorial Guinea was a relatively isolated, ex-Spanish colony under the torrential and violent reign of Francisco Mac��as Nguema, it was inherently unstable. Studies suggest that the former president���s ���reign of terror��� killed or expelled one-third to half the population, contributing to acute economic depression and alienating even his own family.�� The regime was eventually toppled in a palace coup in 1979 by Mac��as��� nephew, current President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. But in 1995, the discovery and beginnings of large-scale extraction of vast crude reserves by Exxon-Mobil brought political stability and entrenched today���s ruling clan. The ruling family in particular has been enriched beyond any reasonable public salary through bribes, laundering, and embezzlement. When the President���s son and Vice President Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue (“Teodor��n”) was convicted and sentenced for embezzlement by a French judge in 2017, a fine of $35 million was levied and a ritzy Parisian mansion seized. But as the country���s wells dry up (300,000 b/d in the early 2000s to roughly 120,000 b/d today) and fiscal insolvency looms, the government has drastically reduced social spending, while recent arrests of insiders suggest the regime has relied less on patronage and more on fear and force. Nevertheless, most if not all analysts agree that President Obiang will successfully transfer power to his son, with little margin for substantive political change on the horizon.

Perhaps the best way to conceive of the Equatoguinean ���state��� is not as such, but as a private enterprise, or even a family business. State security and important ministries (e.g. hydrocarbons) are dominated by the ruling Esangui clan of Mongomo, who are now at work assuring compliance with local content laws which will inevitably benefit family-held businesses, such as Teodor��n���s old shell company, Somagui Forestal. The internationally recognized prerogative of rewarding and withholding lucrative oil contracts has been the regime���s lifeblood. That said, statehood is also problematic for a family which has proved itself keen to convert public funds into family fortunes. Statehood implies compliance with international treaties on human rights and exposes the regime to unwanted press attention, thanks to the pretense of public accountability. As the family are counseled by American consulting firms Greenberg Traurig and Centurion, addressing these concerns is likely to be considered a sunk cost of doing business. To keep the press lid from boiling over, overtures and olive branches are extended which might allow the most important western companies to look the other way; President Obiang adhered to CPLP standards by abolishing the death penalty in April, while Don Alfonso Nsue Mokuy, Third Vice Minister of the Government in charge of Human Rights, defended criticism following the country���s third UPR by claiming that they are an ���open democracy��� and that ���there is no violence against women.��� The very frequent hosting of summits or sporting events serves to guarantee positive news coverage and line pockets. The occasional donations to UNESCO and other charities have been made with no shortage of pageantry.

In addition to the costs of statehood, the regime has proven skillful at taking full advantage of its privileges and immunities, especially when it comes to heading off political contestation from below.�� In a shockingly unequal socioeconomic climate, a cult of personality around President Obiang helps bolster domestic legitimacy, where state media have been successful in convincing many people of His Excellency���s mystical powers and near-godlike status. To preempt any non-state political formations, associations are restricted to a dozen or so people and are regularly monitored, while the non-oil business climate is kept arduous and small; non-state capital formation is dangerous and a direct threat to both the private and public entities owned and operated by the ruling family. If bureaucratic sanctions do not dissuade contestation, the fear of imprisonment and torture will do.�� In addition to the trials outlined above, the law is interpreted broadly by a captured judiciary so as to seal convictions, disband opposition parties, or approve landslide election results. Diplomatic immunity is used to shield the assets of the ruling family���s private fortune, sometimes unsuccessfully, while the diplomatic corps itself is used to cultivate close relationships with regional autocrats like the now-departed ex-presidents Omar al-Bashir and Robert Mugabe.

This is how the regime���s violence and criminality have achieved chronic impunity, by making well-informed use of statehood and resources to deter foreign intervention and block domestic troublemaking. Agreeing with most analysts, the prospects for substantive change in this environment are unsurprisingly slim. Even if oil proceeds are dwindling, a recent and relatively successful round of licensing promises future discoveries, while further development of the country���s gas sector should supplement this. In addition, the clout that oil multinationals have with their home governments means that the most powerful countries have not been and are not likely to be overly receptive to humanist concerns. Above all, Equatorial Guinea is the paragon extraverted state in a neoliberal world, where capital moves and acts freer than labor. In a global system underpinned by carbon energy, the regime will remain intact until it is no longer willing or able to substantially supply for hungry markets.�� Until then, the long-term bottling of any attempts at contre-pouvoir leave the Equatoguinean population bereft of tact, unity, or political-economic collateral.

Apartheid, anthropology and Johnny Clegg

Image credit Dominique Cardinal via Flickr (CC).

Johnny Clegg, the South African musician, best known for his band Juluka, died at his home in Johannesburg on July 16. Most people know Clegg from his album Scatterlings (1982), which can still be found in the “world music” section of most second-hand music shops, or from his 1986 anti-apartheid song “Asimbonanga,”��which pays tribute to Mandela and fallen struggle heroes. He was also a trained anthropologist, who used his training to develop a unique hybridized sound that challenged the apartheid state���s political manipulation of culture.

Growing up in middle-class white South Africa in the late 1990s, Clegg���s music was the background to my childhood and captured much of the optimism of the time. Understandably, as one of the few white musicians who performed in an African language, his music has been associated with the “rainbowism” of this period. While his songs do celebrate a non-racial humanism, they also capture the violent colonial histories that lurk beneath rolling hills and open veldt.

In the song “Mdantsane (Mud Coloured Dusty),” for example, he is asked:

Why don���t you sing about the African moon?

Why don���t you sing about the leaves and the dreams?

Why don���t you sing about the rain and the birds?

In the next verse, he answers. Because, while on the road to the township of Mdantsane, he saw, ���mud coloured dusty blood/ bare feet on a burning bus/ broken teeth and rifle butt.��� Mdantsane is a township in the Eastern Cape outside East London, established in the early 1960s under the Group Areas Act to house black residents evicted from urban townships in the city. As a child, I grew up driving along the same road, usually to go to the beach on family trips. Blinkered by the myopia and cultural provincialism of white South Africa, it would take me years to understand the violence embedded in these landscapes. In a sense, this was the aim of Clegg���s music, to not merely celebrate the natural beauty of South Africa but to situate it in relation to histories of war, migration and hope for a better future.

Apartheid and Censorship

Image credit Dominique Cardinal via Flickr (CC).

Image credit Dominique Cardinal via Flickr (CC).Juluka���s songs were not overtly political. This is to say that while they thematically touched on colonial histories, worker repression and struggle figures, they were not traditional protest songs. While some songs (Asimbonanga, for instance) were banned for political reasons, the real threat that Clegg and Juluka posed to apartheid was the free and open association of black and white artists. The mixing of languages and cultures posed a threat to apartheid���s attempt at creating a Manichean social order.

Apartheid was not only a system of racial segregation, but a form of enforced cultural balkanization. Different ethnic and language groups were seen as discrete and unchanging, with African culture and language, in particular, seen as a relic of an ancient past that needed to be shielded from western modernity. This saw the establishment of distinct ethnic homelands and forms of media production and control for each group.

Starting in the early 1960s, the state turned its attention to the control of publications and music. Control over music was controlled through government ownership of the airwaves and a government censorship board. The Bantu Programme Control Board was formed in the 1960s to oversee radio programming for black South Africans on the state-owned South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC). The SABC was divided into multiple stations that catered to each particular language group, and official policy dictated that languages were not to be mixed.

It was for this reason that the first Juluka song to be censored by the apartheid state was a pop song that celebrated romantic love at the end of the work week. In 1976, Juluka released their first album Ubuhle Bemvelo, which included the track Woza Friday. The song included a mix of English and Zulu lyrics, including the lines ���Woza, woza, Friday my darling; Woza, woza Friday my sweetie.��� The white head of Zulu radio told the band that they should have either used all Zulu or all English, mixing Zulu and English was declared an insult to the Zulu people. The comment reveals the state���s cynical manipulation of culture for political ends, and how censorship was justified under the guise of maintaining the “integrity” of African culture. In another example of this, Pietersburg town council (today Polokwane in Limpopo Province) banned Juluka from performing in the city limits due to the band���s corruption of western culture by mixing it with African culture.

As Clegg points out in a book chapter he co-wrote on Juluka and censorship, this ignored the fact that the version of isiZulu spoken by most people in the country bore little resemblance to a classical Zulu free from western influence. As a spoken language, Zulu in the 1970s, particularly its urban dialect, was already a patois as many South African languages are. The notion of African languages as frozen and emblematic of some romanticized past ignores the dynamism of culture and language.

While control of the airwaves was one mode of censorship, a more direct one was simply police harassment. In the 1970s and 80s white performers were supposed to apply for a permit to perform in townships. Many, including Juluka, did not do so out of principal, which gave police reason to shut down the show. In a Juluka show in Duduza township on the East Rand, for example, three undercover police officers came onto the stage with shotguns, grabbed the microphone and declared the show over. There is also evidence that Clegg and Juluka were subject to police surveillance. Apartheid security branch office Paul Erasmus revealed to researcher Michael Drewett that the branch had a personal file on Clegg. It seems likely that surveillance intensified in the mid-1980s as Clegg came to play a prominent role in the South African Musicians Association, which helped enforce the cultural boycott of South Africa.

While Clegg and Juluka were not overtly political in the way that other apartheid artists were���they did not play ANC fundraisers or align themselves with any particular political faction, they were deeply threatening to the cultural hegemony of the apartheid state. By hybridizing African and western music, they publicly challenged the ideology of racial and cultural separation. They also allowed many South Africans to glimpse a post-apartheid future in which opportunity, friendship and culture would not be narrowly defined by race or ethnicity.

The Anthropologist

Image credit Dominique Cardinal via Flickr (CC).

Image credit Dominique Cardinal via Flickr (CC).Clegg was an anthropologist long before enrolling as a student at Wits University in Johannesburg where he earned a BA and worked alongside the anthropologist and activist David Webster��(later assassinated by an Apartheid death squad). At the age of 14, he visited migrant worker compounds in Johannesburg where he learned to play guitar in the Zulu maskanda style. He visited shebeens and townships around the city, watching Zulu dances and listening to musicians sing about home, movement and work���all themes that permeate his music. Through his friendship with Juluka member Sipho Mchunu, he developed a rich knowledge of both the Zulu language and its musical heritage.

But Clegg���s anthropology did not end merely at observation, he used these experiences to develop a hybridized art that challenged cultural and racial essentialism. In an interview published in Anthropology Southern Africa, he describes his ongoing discomfort with narrow racial and cultural categories. ���Culture is form of coding reality. Codes are constantly changing as each new generation brings in a new way of coding.��� The role of the anthropologist, he notes, is to decode this social world, to make sense of the views, systems and practices that place boundaries around identities and practices. In doing so, we ���facilitate a communication, understanding and celebration of everyone���s endeavor��� We take out of this a deep understanding of what it is to be human.���

Clegg���s personal and musical journey was a pursuit of a humanist universal culture, one that refused the narrow boundaries of racial and cultural essentialism. It was an attempt at using anthropology as performative practice, to not only decode and interpret but to communicate common hopes and struggles. ���Anthropology tells us that before all culture is human culture,��� he says, ���There exists a different expression of the same human need. We are all involved in one project.���

July 18, 2019

Algerian football success is a double-edged sword

Algeria fans at the 2010 World Cup in South Africa. Image credit Nathan Gibbs via Flickr (CC).

It took Algeria barely two weeks to charge one of its own football fans, Samir Sardouk, and sentence him to one year in jail for harming the national interests of his country. Mr. Sardouk was convicted for shouting ���There is no God but Allah, and they will come down��� in Cairo, the capital of neighboring Egypt on June 21 during the African Cup of Nation���s opening match. Four other Algerians were given six-month suspended sentences for lighting firecrackers in the stadium.

Mr. Sardouk���s slogan referred to the months-long mass anti-government protests in Algeria that demanded all those associated with the country���s long-standing president,��Abdelaziz Bouteflika (who was toppled in April), be removed from office. Sardouk���s sentencing casts a shadow over the Algerian squad���s achievements, reaching the African Cup final for the first time in 29 years after defeating Nigeria.

Autocrats historically have used sports���football in particular���to polish their country’s image abroad or their own image locally. However, if celebrations after Algeria���s wins are anything to go by, an Algerian triumph in the finals, like past football victories in countries like Egypt and Iran, are likely to inspire rather than distract anti-government protesters.

Celebrations after the semi-final win did end up turning into mass anti-government protests. Algerian police reportedly detained a dozen demonstrators. This prompted Said Salhi, vice president of the Algerian League for the Defense of Human Rights (LADDH) to�� tweet: ���There is a clear desire to prevent peaceful marches in Algiers, the deployed security device says it all.��� Algerians fans in France took to the streets in Paris, Marseille and Lyon within hours of Algeria reaching the final. Their celebrations were mired by violence. These events added context to the conviction of Mr. Sardouk as protestors demanded a ���civilian, not a military state.���

Algerian fan violence at the��African Cup is not new. A massive brawl between players and fans mired a 2014 Libya-Algeria African Cup qualifier. Yet, the violence associated with this year���s tournament was minimal when compared to violence in the past.��An apparent shift away from violence is all the more remarkable given Algerian psychologist Mahmoud Boudarene���s assessment in 2014:

Violence in Algeria has become ordinary and banal. Hogra, the word Algerian use for the government���s perceived contempt for ordinary citizens, has planted a sickness in Algerian society. People feel that the only way to get anything done is to have connections or threaten the peace. It is a system where hogra and social injustice rule. Social violence has become the preferred mode of communication between the citizen and the republic���today in our country everything is obtained through a riot.

This year���s popular revolt, inspired by lessons learnt from the 2011 popular Arab revolts, has emboldened protesters and given them a sense of confidence that is likely to ensure that any potential African Cup final celebrations-turned-protests remain largely peaceful.

On the government’s side, in spite of an increased police presence, the Algerian defense ministry was preparing six military planes to fly 600 fans to Egypt for the African Cup final. The gesture underlined football���s political importance and constituted an attempt by the military to align itself with the Algerians squad���s success.

The significance of football in Algeria makes Mr. Sardouk���s sentencing all the more remarkable despite the government’s assertion that his slogan mired Algeria���s march towards football victory.

For starters, it sought to draw a dividing line between national honor and protest in a country where a majority are likely to be football fans. He was convicted at a time that Algeria has been wracked by protests since February in support of political reforms that would dismantle the country���s long-standing, military-dominated regime with a more transparent and accountable government. The conviction is also noteworthy because Mr. Sardouk���s protest, coupled with acts of defiance by militant Egyptian football fans, threatened to turn the African tournament into a venue for the expression of dissent from across the Middle East and North Africa, a region populated by autocratic, repressive regimes and wracked by repeated explosions of poplar anger.

Finally, the sentencing was striking because it violated the spirit of both the military���s effort to retain a measure of control by co-opting the protests and a long-standing understanding with militant football fans that preceded the recent demonstrations that allowed supporters to protest as long as they restricted themselves to the confines of the stadium.

The Algerian military���s attempt to curtail fans and co-opt the revolt bumps up against the fact that the protesters, like their counterparts in Sudan, Morocco, Pakistan and Russia, have sought to avoid the risks of the military seeking to implement an a Saudi-United Arab Emirates template to blunt or squash the protests.

The core lesson protesters learnt is that the protests��� success depends to a large extent on demonstrator���s willingness and ability to sustain their protests even if security forces turn violent. An Algeria that emerges from the African Cup final as the continent���s champion would give the protesters a significant boost. It also constitutes an opportunity to ensure that Algeria does not revert to an environment in which violence is seen as the only way to achieve results.

Said, a former senior Algerian intelligence official proclaimed: ���We will return to violence if there is no real democratic transition. The African Cup doesn���t fundamentally change that but does offer a window of opportunity.���

July 17, 2019

Africa’s first UNESCO city of literature gets a new literary festival

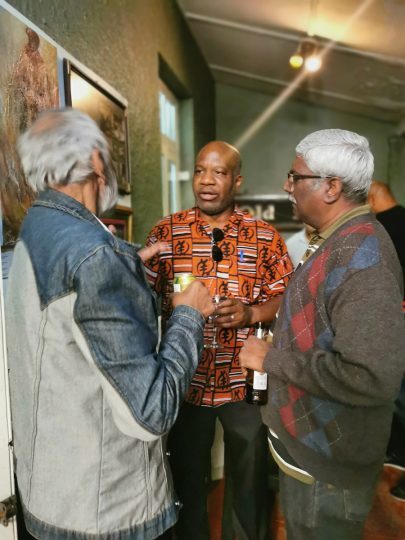

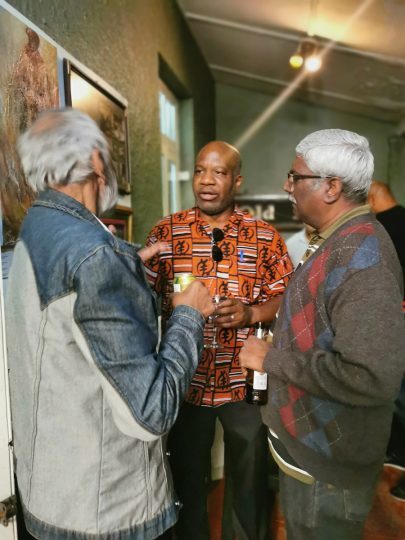

Jackie Shandu and Gcina Mhlophe talk. Fred Khumalo in front row.

Ike���s Books, in Durban, is no ordinary bookstore. In 1988, with South Africa in a seemingly endless ���state of emergency��� as the apartheid regime desperately tried to hold power, Joseph David “Ike��� Mayet, an Indian man, opened his shop. This seemingly trivial act very much contributed to the struggle against apartheid. Its first location was in the Overport neighborhood, designated under the Group Areas Act as reserved for South Africans of Indian origin. However, by the late 1980s, anti-racist South Africans of all backgrounds lived around���and patronized���this bookstore, and so it became one of the many theaters in the vast struggle to break apartheid. As people of all races���Black, Coloured, Indian, and White���browsed for books, bought books, debated ideas, and interacted with each other at Ike���s, they engaged in a collective, radical, and very much political act.

Ike���s current location, on Florida Road, was officially opened in 2001 with a reading by none other than J.M. Coetzee, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2003. To this day, as a contributor to Johannesburg���s Mail and Guardian���s opined in 2013: ���One can���t resist a bookshop that makes you want to read the moment you enter it; not later, not when you get home, but right there, right that minute. Ike���s Books and Collectables in Durban is such a place.��� After Mayet passed away, in 2002, Joanne Rushby ably stepped into the breach and has continued the Ike���s tradition.

Ronnie Kasrils speaks. Aswin Desai listens. Image credit Peter Cole.

Ronnie Kasrils speaks. Aswin Desai listens. Image credit Peter Cole.Durban has a vibrant cultural scene. Its annual Film Festival is quite popular. Plenty of writers and activists have called Durban home including Steve Biko, Alan Paton, Bessie Head, Lewis Nkosi, Zuleikha Mayat, and more. However, until Jo Rushby,��Ashwin Desai,��Darryl David, and friends decided to create one, the city had only one major literary event,��the��Time of the Writer International Writers Festival���this despite being named a����in 2018. Hence, Ike���s first-ever Durban Literary Festival, held over three days in late June, filled a yawning gap. (Full disclosure: At the festival, I spoke about my book, Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area. I���ve also spent many an hour browsing the shelves at Ike���s.)

Opening night was packed on a lovely winter evening for which Durban is rightly renowned. With chairs set up on the wraparound balcony, and the crowd filling the aisles inside the shop, more than one hundred people squeezed together. First, they listened to ANC veteran and former government minister, Ronnie Kasrils, regale with stories from his life and in advance of his latest memoir, Catching Tadpoles, which should be published later this year. Kasrils is best known for being a leading figure in Umkhonto we Sizwe (���Spear of the Nation��� or MK), the armed underground wing of the African National Congress (ANC). In the early 1960s, after the Sharpeville Massacre, Kasrils moved from his native Johannesburg to Durban to figure out how to get involved in the struggle. He ended up commanding MK���s Natal regional command before going into exile where he continued his work with MK and the ANC.

Robert Trent Vinson and two audience members. Image by Joanne Rushby.

Robert Trent Vinson and two audience members. Image by Joanne Rushby.Ashwin Desai served as something both more and less than a master of ceremonies. An accomplished writer in his own right���including We Are The Poors and The South African Gandhi: Stretcher Bearer for the Empire (co-authored with Goolam Vahed), Desai introduced Kasrils and asked entertaining and probing questions. However, even Desai���s wit paled in comparison with Kasrils��� captivating, powerful stories of coming of age in 1950s Johannesburg where he tried���as a white South African���to embrace the vibrancy of life as a cultural bohemian while rejecting the horrific contradictions of apartheid. Ultimately, after Sharpeville, Kasrils found that it was not possible to be an apolitical existentialist so he joined the Congress of Democrats (basically, a front group for the banned Communist Party of South Africa) and, soon thereafter, served as the Natal regional commander of MK.

In the best style of Ike���s, which offers books of many varieties, the second author to speak on opening night was Erica Platter discussing her book Durban Curry: So Much of Flavour���People, Places, and Secret Recipes (with delicious photographs by Clinton Friedman). Though based in Cape Town, Platter is from Durban; though white, she���s an experienced journalist who found numerous Indian Durbanites to share their recipes that explore the flavors, variety, and indeed spices of Durban���s legendary Indian cuisine���South Asia meets South Africa.

Flow Wellington speaks to audience. Image by Joanne Rushby

Flow Wellington speaks to audience. Image by Joanne RushbySaturday and Sunday were filled with another fifteen authors discussing an array of topics too numerous to discuss here. Joy Chimombe, a Zimbabwean now living in KwaZulu-Natal, talked about growing up in Rhodesian townships during the 1970s���her father a teacher who joined the armed struggle. Chimombe and thirty other women contributed chapters to their anthology Township Girls: The Cross-over Generation (Weaver Press) which chronicles their coming of age in an era that transitioned from a brutal, white minority regime to, in 1980, a democratic nation.

Another highlight was Robert Trent Vinson discussing his new short biography of Albert Luthuli. An African American who grew up in 1980s Los Angeles and watching on TV how the South African police���s notorious armored personnel carriers, dubbed ���hippos,��� attack black students in the townships, Vinson could relate as he watched, close to home, LA police battering ram tanks (popularized by rapper Toddy Tee���s 1985 ���Batterram���) and helicopters (���ghetto birds���) intended to surveil and contain black Americans. Using a trove of letters, reports, and more smuggled out of South Africa in 1967 by Thandeka (Thandi) Luthuli, one of the Nobel Peace Prize winner���s daughters, Vinson has crafted a powerful, concise biography that deserves wide readership in South Africa and worldwide.

Author Peter Cole speaks. Organizer Aswin Desai to left. Image by Joanne Rushby

Author Peter Cole speaks. Organizer Aswin Desai to left. Image by Joanne RushbyThe journalist and author Fred Khumalo, based in Johannesburg, discussed his latest book of essays, the widely praised Talk of the Town. An earlier book of his, the historical novel Dancing the Death Drill, imagined one man who survived the tragedy of the SS Mendi, which sank off the Isle of Wight during World War I and claimed the lives of more than 600 mostly black soldiers; this novel recently was released as a Zulu translation. Khumalo���s latest effort explores contemporary South Africa���s and South Africans��� conflicts over identity, the reality that millions of people from other African nations live in South Africa and the intense xenophobia they experience, the relationship between South Africa and the rest of the continent, South Africans who live abroad, South Africans who went into exile during apartheid, and more.

The poster for the Durban Literary Festival.

The poster for the Durban Literary Festival.Closing out the festival, on Sunday afternoon, Khumalo, Jackie Shandu (who heads the Policy, Research and Political Education program of the Economic Freedom Fighters in Kwazulu-Natal province), and Gcina Mhlophe mixed it up. Mhlophe, also born and raised in KZN, has had a long career as a writer, story-teller, and actress and continues traveling the world to perform. These three thoughtful figures wowed the audience as they discussed South African authors of old, jazz, and more.

Durban���s first literary festival was a rousing success but could have benefited from wider publicity to draw more people, particularly young people and black people, to the lovely space at the foot of Florida Road, just outside of Greyville. Let���s hope that there is a second, third, and many more iterations of this worthy endeavor.

Africa’s first UNESCO city of literature gets its first literary festival

Jackie Shandu and Gcina Mhlophe talk. Fred Khumalo in front row.

Ike���s Books, in Durban, is no ordinary bookstore. In 1988, with South Africa in a seemingly endless ���state of emergency��� as the apartheid regime desperately tried to hold power, Joseph David “Ike��� Mayet, an Indian man, opened his shop. This seemingly trivial act very much contributed to the struggle against apartheid. Its first location was in the Overport neighborhood, designated under the Group Areas Act as reserved for South Africans of Indian origin. However, by the late 1980s, anti-racist South Africans of all backgrounds lived around���and patronized���this bookstore, and so it became one of the many theaters in the vast struggle to break apartheid. As people of all races���Black, Coloured, Indian, and White���browsed for books, bought books, debated ideas, and interacted with each other at Ike���s, they engaged in a collective, radical, and very much political act.

Ike���s current location, on Florida Road, was officially opened in 2001 with a reading by none other than J.M. Coetzee, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2003. To this day, as a contributor to Johannesburg���s Mail and Guardian���s opined in 2013: ���One can���t resist a bookshop that makes you want to read the moment you enter it; not later, not when you get home, but right there, right that minute. Ike���s Books and Collectables in Durban is such a place.��� After Mayet passed away, in 2002, Joanne Rushby ably stepped into the breach and has continued the Ike���s tradition.

Ronnie Kasrils speaks. Aswin Desai listens. Image credit Peter Cole.

Ronnie Kasrils speaks. Aswin Desai listens. Image credit Peter Cole.Durban has a vibrant cultural scene. Its annual Film Festival is quite popular. Plenty of writers and activists have called Durban home including Steve Biko, Alan Paton, Bessie Head, Lewis Nkosi, Zuleikha Mayat, and more. However, until Jo Rushby, Ashwin Desai, Darryl David, and friends decided to create one, the city had no literary festival���this despite being named a in 2018. Hence, Ike���s first-ever Durban Literary Festival, held over three days in late June, filled a yawning gap. (Full disclosure: At the festival, I spoke about my book, Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area. I���ve also spent many an hour browsing the shelves at Ike���s.)

Opening night was packed on a lovely winter evening for which Durban is rightly renowned. With chairs set up on the wraparound balcony, and the crowd filling the aisles inside the shop, more than one hundred people squeezed together. First, they listened to ANC veteran and former government minister, Ronnie Kasrils, regale with stories from his life and in advance of his latest memoir, Catching Tadpoles, which should be published later this year. Kasrils is best known for being a leading figure in Umkhonto we Sizwe (���Spear of the Nation��� or MK), the armed underground wing of the African National Congress (ANC). In the early 1960s, after the Sharpeville Massacre, Kasrils moved from his native Johannesburg to Durban to figure out how to get involved in the struggle. He ended up commanding MK���s Natal regional command before going into exile where he continued his work with MK and the ANC.

Robert Trent Vinson and two audience members.

Robert Trent Vinson and two audience members.Ashwin Desai served as something both more and less than a master of ceremonies. An accomplished writer in his own right���including We Are The Poors and The South African Gandhi: Stretcher Bearer for the Empire (co-authored with Goolam Vahed), Desai introduced Kasrils and asked entertaining and probing questions. However, even Desai���s wit paled in comparison with Kasrils��� captivating, powerful stories of coming of age in 1950s Johannesburg where he tried���as a white South African���to embrace the vibrancy of life as a cultural bohemian while rejecting the horrific contradictions of apartheid. Ultimately, after Sharpeville, Kasrils found that it was not possible to be an apolitical existentialist so he joined the Congress of Democrats (basically, a front group for the banned Communist Party of South Africa) and, soon thereafter, served as the Natal regional commander of MK.

In the best style of Ike���s, which offers books of many varieties, the second author to speak on opening night was Erica Platter discussing her book Durban Curry: So Much of Flavour���People, Places, and Secret Recipes (with delicious photographs by Clinton Friedman). Though based in Cape Town, Platter is from Durban; though white, she���s an experienced journalist who found numerous Indian Durbanites to share their recipes that explore the flavors, variety, and indeed spices of Durban���s legendary Indian cuisine���South Asia meets South Africa.

Flow Wellington speaks to audience.

Flow Wellington speaks to audience.Saturday and Sunday were filled with another fifteen authors discussing an array of topics too numerous to discuss here. Joy Chimombe, a Zimbabwean now living in KwaZulu-Natal, talked about growing up in Rhodesian townships during the 1970s���her father a teacher who joined the armed struggle. Chimombe and thirty other women contributed chapters to their anthology Township Girls: The Cross-over Generation (Weaver Press) which chronicles their coming of age in an era that transitioned from a brutal, white minority regime to, in 1980, a democratic nation.

Another highlight was Robert Trent Vinson discussing his new short biography of Albert Luthuli. An African American who grew up in 1980s Los Angeles and watching on TV how the South African police���s notorious armored personnel carriers, dubbed ���hippos,��� attack black students in the townships, Vinson could relate as he watched, close to home, LA police battering ram tanks (popularized by rapper Toddy Tee���s 1985 ���Batterram���) and helicopters (���ghetto birds���) intended to surveil and contain black Americans. Using a trove of letters, reports, and more smuggled out of South Africa in 1967 by Thandeka (Thandi) Luthuli, one of the Nobel Peace Prize winner���s daughters, Vinson has crafted a powerful, concise biography that deserves wide readership in South Africa and worldwide.

Author Peter Cole speaks. Organizer Aswin Desai to left.

Author Peter Cole speaks. Organizer Aswin Desai to left.The journalist and author Fred Khumalo, based in Johannesburg, discussed his latest book of essays, the widely praised Talk of the Town. An earlier book of his, the historical novel Dancing the Death Drill, imagined one man who survived the tragedy of the SS Mendi, which sank off the Isle of Wight during World War I and claimed the lives of more than 600 mostly black soldiers; this novel recently was released as a Zulu translation. Khumalo���s latest effort explores contemporary South Africa���s and South Africans��� conflicts over identity, the reality that millions of people from other African nations live in South Africa and the intense xenophobia they experience, the relationship between South Africa and the rest of the continent, South Africans who live abroad, South Africans who went into exile during apartheid, and more.

Closing out the festival, on Sunday afternoon, Khumalo, Jackie Shandu (who heads the Policy, Research and Political Education program of the Economic Freedom Fighters in Kwazulu-Natal province), and Gcina Mhlophe mixed it up. Mhlophe, also born and raised in KZN, has had a long career as a writer, story-teller, and actress and continues traveling the world to perform. These three thoughtful figures wowed the audience as they discussed South African authors of old, jazz, and more.

Durban Literary Fest poster.

Durban Literary Fest poster.Durban���s first literary festival was a rousing success but could have benefited from wider publicity to draw more people, particularly young people and black people, to the lovely space at the foot of Florida Road, just outside of Greyville. Let���s hope that there is a second, third, and many more iterations of this worthy endeavor.

Justice in the Sahel

Image credit G��rard Bontoux via Flickr (CC).

In the long memory of most societies, the first and last obligation of the sovereign���or as we now say, the state���is justice. In interviews, I had with Fulani from the border that Niger shares with Mali, this was the dominant theme: justice, or rather its absence, and its necessity.

Across the tough ecological terrain of the Sahel-Sahara, in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, the ���Fulani��� are the focus of conflict. Their foes in central Mali, we are told, are the Dogon; in Burkina, the Mossi. Their enemies in Niger would be Tuareg, but mainly Tuareg from Mali (who, however, have brotherly connections in Niger).

They are seen as ���terrorists,��� the foot army of the Macina Liberation Front and its leader Amadou Kouffa. The impression that arises is of a vast war of the Fulani against everyone else, which might be described in an either/or fashion. Either the Fulani are the villains, because so many different peoples can���t be all wrong and they are known for being aggressive, as nomads often are; or they are persecuted in the mode of the abhorrent shared aversion that explains the plight of the Jews. One hears the two notions, though more often the latter (or a combination of both). They are difficult, or perhaps impossible to verify. They also obfuscate the fact that there are distinct conflicts in the region involving subsets of Fulani who do not have the same interests���and in so doing, they play into the agenda of outside forces who would rather have everyone enlisted in two big camps, the Jihadists and their foes, so that the Sahel could become the type of battlefield that places like Afghanistan have been turned into. These outside forces are the Salafi extremists who initially descended from North Africa (especially Algeria) in the early 2000s, and the western armies who are here to prevent them from menacing Europe from strongholds in West Africa. Indeed, western commentators often compare the Sahel to Afghanistan���dubbing it at times ���Sahelistan��� or ���Africanistan.��� But they conveniently forget how Afghanistan came to be what it is: Salafi extremists imported from Arabia, and western armies airlifted to fight them���with everyone in the area forced to choose a camp.

In the borderlands of Mali and Niger where I conducted research, the story I heard varied little, whether it was told by a Fulani or by someone from a different ethnicity. It starts somewhere in the 1970s, when rogue Malian soldiers who were rotting in idleness in their remote outposts of Gao and Kidal, took to pillaging nomadic Fulani herders from Niger. Though at first occasional and limited���in particular the soldiers were careful not to cross into Nigerien territory���this behavior started something bad. A pattern took shape of raiding Fulani for cattle, sheep and goats, in which some local Tuareg groups got involved. Via networks overseen by rogue elements in Mali���s military and administration, the animals were carted to southern Malian markets where they brought huge profits���especially since they were stolen, not bought. In sum, this was good old (if one may say) freebooting.

Later, in the chaotic context of the 1990s, where both Mali and Niger were rattled by Tuareg rebellions and unruly democratization processes, the freebooters were emboldened and started attacks within Nigerien territory. In the past, it was difficult for the Fulani herders to seek redress in Niger since everything was happening in Mali. Now, however, they were able to appeal to the state of Niger for justice and protection, especially since attacks within their home base were more devastating than those on the transhumance path. Niger���s authorities shrugged their claims off, the Fulani formed a self-defense militia, and things predictably got out of hand. A major Malian Tuareg leader was killed by the militiamen in 1997 and this set off a cycle of razzia and vendetta in the parched borderlands.