Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 212

July 16, 2019

A very American story

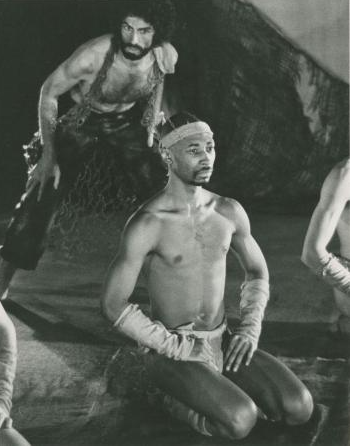

Night Before Thinking production at La Mama 1989. Image credit La Mama archive.

The past few months have seen much cultural ferment in the North African (in particular, Berber) communities of the United States. There were the Yennayer New Year celebrations across American cities in mid-January���2019 corresponds to the year 2969 on the Amazigh calander. There was the all-day��Tafsut��celebration in Union City, New Jersey on April 27. This was a pan-Berber gathering that drew Amazigh-Americans of Algerian, Moroccan and Malian descent���to commemorate the Berber Spring (Tafsut), the period of protest and civil activism that erupted in Kabylie, Algeria in March 1980. The recent activity���including the weekly Sunday afternoon rallies at Union Square in Manhattan, New York���is prompted by ongoing events in Algeria and Morocco, but is also evidence of the cultural work done by the growing Amazigh-American community. At the center of it all is Hassan Ouakrim, the Moroccan director, choreographer, art collector, and elder statesman of the Berber community in the US, who has just published the first volume of his autobiography.��Memoir of A Berber, Part I. It chronicles Ouakrim���s childhood in colonial Morocco, his attempts to create a nationalist theater movement after independence, his three decades as artistic director at La Mama Theater in New York, and fifty years as ���master teacher��� who introduced myriad Berber and Saharan dances (like��ahwach) to the United States.

On Sunday April 29th, a patterned��caidale��Moorish tent was set up on the sidewalk in the East Village, just outside the Algerian restaurant Nomad. Online the event was billed as the great ���Maghreb Night Celebration,��� though in truth it was a book launch for and celebration of the seventy-nine year-old Ouakrim. As various musicians took to the makeshift stage, and dancers and drummers swirled around, Ouakrim sat cross-legged inside the patterned tent, receiving guests, many of them former students. Turbaned, bejeweled, with lanterns hanging overhead, and a burning brazier in front of him, he looked (intentionally, no doubt) like a North African sorcerer.

Inossis Berber Ballet Theatre 1968. Image credit the Oukarims archive.

Inossis Berber Ballet Theatre 1968. Image credit the Oukarims archive.���My story is quite different,��� he explained in between book signings, ���but it���s a very American story.��� Next to him stood an old-time friend, Mrabet, who was wearing a ���star-spangled djellaba.��� The ���red, white, and blue��� robe, visitors were told, was designed for Mick Jagger for his visit to Morocco in 1989.

Ouakarim���s memoir begins in 1947, in the ���earthen village��� of Aday, deep in French-colonized central Morocco, near Tafraout, a town in the anti-Atlas mountains. The opening scene has seven-year Hassan standing on the side of road with his mother, waiting for a bus that will take him a thousand miles north to be with his father, a charcoal vendor in the kasbah of Tangier. ���My mother, dressed in black, standing next to me, prayed and cried silently. She handed me a small bundle of a loaf of bread, a few boiled eggs, and a small jar of argan oil,��� he writes. ���I kissed her hand and ran to the bus.��� Thus, begins a charming account���told through a seven-year old���s eyes���of a journey through the mountain ranges of French Morocco to Spanish Morocco to the International Zone of Tangier. Ouakrim encounters the sea for the first time in Agadir and then Mogador (Essaouira), changes buses in Casablanca, before crossing the border to the Spanish-controlled north. In colonial Tangier, the seven-year-old sleeps on a straw-mat on a rooftop in the medina with distant cousins. Every morning he would walk from the impoverished native quarter to the European area to attend the��Ecole Poncey��where his father enrolled him.

He quickly learned basic French and Spanish, earning his Certificat d���Etudes Primaires in 1953. His father couldn���t afford to pay for high school, so he was sent to stay with an uncle back south in Marrakech. The 12-year-old moved from one guardian to another and to different colonial schools; he would be mocked for his accent, spurned for being ���a low-class Berber��indig��ne.��� He survived deprivation and mistreatment, in part by taking flight with his imagination and escaping into the world of the��jinn��(spirits).

Though departing my birthplace of Aday left me numb and my heart broken, my Berber spirit did not leave me. In dreams at night, a flying horseman would sweep down from above on a glowing white horse, raising a sword. In my��burnous��and turban, I would join him. We would fly over the Atlas Mountains, free, exploring the contours of the land.

Ouakrim giving a gnawa master class.

Ouakrim giving a gnawa master class.In Marrakech, shunned and bullied by classmates and teachers, he would find refuge in Jamaa El Fna, the city���s famous plaza. He would disappear into the throng of troubadours, musicians, healers and fake doctors���awed by ���the magic of showmanship.��� As he writes, ���I connected with the fantasy of Jemaa El���fna in the fifties mainly to distract myself from my negative thoughts in times of despair and emptiness.��� The boy was enchanted by the street performers as well as by the ���invisible ghosts and spirits��� that inhabited in the medina���s alleyways. One day while he stood watching a Sufi master who could make milk flow from an empty jug, the healer grabbed him by the wrist and yanked him forward: ���You don���t belong here. Go back north where you came from;��� he then added, ���later in your life, you will leave this land… You will fly over the ocean��� by the power of baraka, the blessing of Sidi Moulay Brahim������referring to the saint whose spirit soars over the Atlas Mountains. ���When you cross the ocean, where you find large bridges, that���s where you must spend your life, in��Blad al-Marikan, America.��� The first volume of Ouakrim���s memoir ends with him landing at JFK airport one icy afternoon in January 1972, and while crossing the Williamsburg Bridge to lower Manhattan, he recalls the healer���s prophesy.

La Jilsa 1974. Image credit La Mama.

La Jilsa 1974. Image credit La Mama.Ouakrim paints a rich portrait of life in colonial Marrakech, where the French are ruling through the Berber strongman Thami El Glaoui������lord of the Atlas������while cracking down on the fledgling nationalist movement. ���Kill the terrorists, wherever they hide,��� was the colonial state���s motto. The young Ouakrim begins to develop a nationalist consciousness, mainly through his uncle, Ahmed Ouakrim, a leader in the Moroccan Liberation Army, and future head of the Moroccan Veterans��� Association. In August 1953, the Moroccan sultan Mohammed V was sent into exile by the French and replaced by his cousin Ben Arafa, who is widely viewed by the Moroccan population as a puppet king. One day in early 1954, Hassan, a precocious student at his��coll��ge,��was summoned to the principal���s office, and told that he had been selected to present a bouquet of flowers to Ben Arafa who was to visit the school soon. The principal���s assistant even took measurements for the white djellaba that the boy would wear. Upon conferring with his friends, the 12 year-old decided that he would not make a ���public offering to a fake king.��� When he returned to the principal���s office and informed them that he couldn���t get permission from his father, the principal kicked him and threw him against the metal cabinets. ���My only sensory awareness was the sound of my head crashing against metal.���

The fourteen-year old did well in refusing to honor the puppet sultan. Some days after visiting the��coll��ge, Ben Arafa went to pray at the ancient Berrima mosque in the medina of Marrakech. On the other side of the medina���s wall, Ouakarim and his cousin Dabelk were strolling through the alleyways shopping for lamb chops. They could hear the drums and trumpets from the other side, the pomp and circumstance surrounding Ben Arafa���s visit. Suddenly, they heard an explosion: a grenade had been tossed at the sultan as he was leaving the mosque. In the smoke, panic and mayhem, the boys saw Ben Arafa being escorted into a car, his robe stained with blood. Hundreds of soldiers sealed off the medina���s gate, trapping everyone inside. Hassan and his cousin were thrown up against a wall, as military officials with dogs searched every individual. One of the dogs suddenly growled and jumped at Hassan���s cousin, yanking him down to the ground. The police rushed and found that Dabelk was, per tradition, carrying a kilo of lamb chops in the hood of his djellaba; that���s what drew the dog���s attention.

Hassan Ouakrim and his friend Khalil Mrabet at the book launch of Memoir of Berber.

Hassan Ouakrim and his friend Khalil Mrabet at the book launch of Memoir of Berber.Ouakrim would return to Tangier soon thereafter, where he would finish high school. He began attending theater workshops, classes in vocal training and mime techniques. In 1958, he was selected to dance at the Royal Theatre in Gibraltar, where he was given an award by the British governor and his wife; this was his first time traveling overseas and representing Morocco. When Tangier became part of Morocco in 1960, he and the actor Bachir Skiredj worked to create a nationalist theater movement in the city. Ouakrim would go on to work as a school inspector and university administrator���shuttling between Rabat and Tangier. In 1968, he founded Inossis, the still existing Berber theater group, that mixes ballet with Amazigh folklore. Ouakrim came up with the name by using his friend William Burroughs��� ���cut-up technique”: he cut up a few words into single letters, shuffled the letters randomly, and accepted the result������Inossis.”

Memoir of A Berber contains hilarious vignettes, lots of gossip, and descriptions of the most popular bars, bordellos and nightclubs of 1960s Morocco. But the memoir also captures the exhilaration that many Moroccan artists felt at independence, and just as poignantly the heartbreak as the monarchy, worried by leftist protest, clamped down on artists and intellectuals. ���The late sixties saw a flourishing in all kinds of arts,��� writes Ouakrim, but ���most [artists] came up against bureaucratic walls impossible to break��� Since Morocco���s independence, artists have been interested in giving back to their country��� However, the government has had other interests��� red tape ties up the efforts of artists in Morocco, diminishing our cultural identity day by day.���

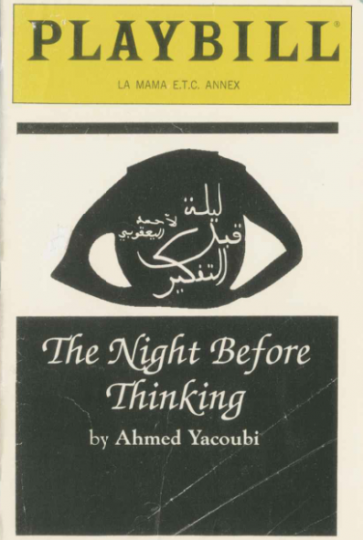

In early 1972, Ellen Stewart, the legendary director and founder of La Mama Experimental Theater, invited Ouakrim to help her stage the play ���A Night Before Thinking,��� an adaptation of a story recounted by the Moroccan painter Ahmed Yacoubi to novelist Paul Bowles. (The introduction to��Memoir of A Berber��is actually written by Stewart: she refers to Ouakrim as her ���son������and ���the cultural ambassador of Moroccan culture in the United States.���) Ouakrim would rise to become artistic director at La Mama. Almost 50 years later, Ouakrim still lives in the East Village, a few blocks from the theater. His fourth-floor apartment is museum-like, with artifacts from around the world: tableaux by the late Moroccan painters Ahmed Yaqubi and Mohammed Hamri as well as 18th century Syrian wooden room divider, rare fabrics and tapestries, antique teapots and silver rosewater bottles from across North Africa, and baskets and baskets of North African jewelry. When talking to guests or journalists, Wakrim, will sit atop a mosaic wooden chair, in a blue Tuareg robe and turban, adjusting his gem-studded bracelets and rings, as he discusses ancestor-veneration in Berber societies, his friendship with Jean Genet, and his love of ���Kabbalistic knowledge.���

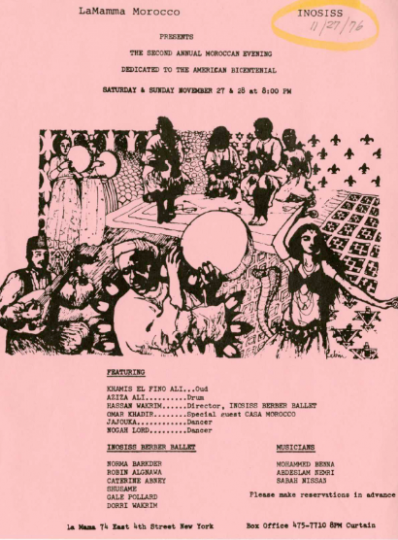

1976 Moroccan evening celebrating Americas Bicentennial and Morocco being first country to recognize American independence.

1976 Moroccan evening celebrating Americas Bicentennial and Morocco being first country to recognize American independence.Memoir of A Berber is eighty pages of text and thirty pages of fascinating photographs: we see Ouakrim with his father in their ancestral village; shots of early performances by Inossis; photographs of the author with a number of celebrity musicians and writers he has collaborated with (novelist Mohammed Choukri, Jean Genet, Allen Ginsberg, Randy Weston). There is also one intriguing photo of Ouakrim dressed up as a French-colonial soldier, posing with Donald and Ivanka Trump, at a dress-up party in the Hamptons in 1992.

The final chapters recount Ouakrim���s escapades with the late painter Mohammed Hamri, and the Master Musicians of Jajouka, the Sufi group that Burroughs termed the ���4000-year old rock and roll band.��� Jajouka have recorded with the jazz musicians Ornette Coleman, and Weston, as well as Brian Jones, founder of the Rolling Stones. The latter recorded ���Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Jajouka��� after visiting Morocco in 1968���and hoped to incorporate the group���s rhythms into the music of the Rolling Stones. But on July 2, 1969, Jones was found motionless at the bottom of the pool at his farmhouse.�� Rolling Stone fans have long wondered about the circumstances surrounding his mysterious death. (The coroner���s report stated ���death by misadventure,��� noting that Jones��� liver was enlarged by drug and alcohol use.)

In the last pages of ���Memoir of A Berber,��� Ouakrim���who was initiated into the Jajouka group���offers an alternative theory for the English musician���s death: Jones was cursed by the Jajouka after a payment dispute���and was subsequently struck by lightning while in his pool at Catchford Farm. ���I was part of that somber ceremony when the Master Musicians gathered outside to clean up business with Brian Jones,��� writes Ouakrim, ���They formed their circle, calling upon the spirit of Jajouka. Instead of praying to the sky, for all, they turned their palms down, and did the prayer in reverse��� Brian Jones was struck by lightning in his pool while the musicians were delivering their curse. The powerful energy from the cosmos came down and struck him, piercing his heart.��� The Jajouka would later make a recording���in Ouakrim���s possession���where they forgive Jones and ask the spirits to bless him. The Rolling Stones would, in 1989, visit Tangier and record the track ���Continental Drift��� with Jejouka, as a tribute to Jones.

1989 production at La Mama.

1989 production at La Mama.Ouakrim suspects it was Mick Jagger���who envied Jones���who prevented the latter from paying the Moroccan musicians: ���Personally, I never liked Mick Jagger.”

July 15, 2019

What role for the Black American Left on Sudan?

Image credit Jedrek B via Flickr (CC).

In the wake of former Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir���s fall from power in April 2019, the Black Agenda Report (BAR)���one of the oldest and most respected Left black online publications (including a podcast) in the United States���published its first analysis of the uprisings that had been growing in Sudan since December 2018. The BAR published an article entitled ���Saudi Arabia, Israel, US all Sought Bashir���s Ouster: So how Real was the Sudan Revolution?,��� by a Chile-based journalist, Whitney Webb, who suggested that the uprising had merely been manufactured by Saudi Arabia, the US, and Israel. As a a BAR listener and a Pan-Africanist, I was disappointed both by the fact that BAR took so long to offer analysis on the events in Sudan, and by the simplicity of the analysis itself.

The author pointed to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf state actors��� support for the Transitional Military Council (TMC) as evidence to back their claim that foreign actors have manufactured the revolution. In doing so, the author is conflating the formation and leadership of the TMC with the popular uprising. To be clear, protests continued even after Al-Bashir had stepped down and the TMC had been established by military leadership. It is by now evident that even with Al-Bashir gone, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the US are interested in his policies remaining in place under new leadership. For example, Saudi Arabia is keen to maintain the presence of Sudanese troops in its war on Yemen.

Rather than pay attention to the months of organizing, or the root causes of popular unrest (most notably, adverse economic conditions), the author concludes that the Sudanese revolution began and ended with the arrest of Al-Bashir on April 11, 2019. By reducing everything to this event, the author bastardizes the term ���revolution��� that many of us associate with mass long-term organizing and protests. For months, organizers in Sudan coordinated the transportation of thousands of protestors from throughout the country to participate in marches and sit-ins both within the capital city of Khartoum as well as smaller cities. Protestors established neighborhood committees to maintain communication without the assistance of the internet. Attending a rally on June 30th in London in solidarity with the Sudanese revolution, I was speaking to a Sudanese friend who is active in the protests. When I mentioned the BAR article, she responded, ���tell them to come to Khartoum, I���ll show them how real it is.���

The BAR has long been committed to offering critical analysis of global empire and the racist, anti-black, and colonial logics that undergird contemporary global politics. In this vein, it has raised important questions about the interests and motivations behind Al-Bashir���s indictment by the International Criminal Court. Yet it appears that BAR���s critique of the ICC on Sudan has rendered it incapable of listening to those with the most at stake in the future of Sudan. BAR���s single-minded focus on the dismantling of US and European empire has had an unintended blinding effect towards popular demand for change.

The April BAR article is representative of a paradigm that has rendered self-identified Black American Leftists unable to recognize the emergence of grassroots uprising on the African continent. The conventional position continues to hope for a revolutionary black consciousness on the horizon yet to come, or to lament the distance we now have from the material and ideological successes of the 1960s and 1970s. In other words, we have lost our sensitivity to revolutions that are actually already existing. The dismissal of such uprisings renders little practical difference between the Black American Left and the social and political scientists of Euro-American universities whose analyses following the so-called Arab Spring predicted that similar political mobilization was impossible or improbable in African countries south of the Sahara. In each case, the analysis is either over-determined by empire or by the repressive nature of authoritarian regimes, rendering the African masses unthinking and unimaginative subjects.

What is lost in such accounts is the opportunity for the Black American Left to learn and to bear witness to the strategies and processes that have enabled nationwide organizing in Sudan, home to the oldest communist party on continental Africa. As members of the Black American Left, the endurance of such an uprising on the continent should have garnered ardent attention. As marches and public protests in the US are often limited to highly curated events, negotiated with local police, we should pay attention to the organic and durable organizing that characterize the uprisings in Sudan. Our commitment to global liberation should open us up to how and when new revolutionary processes of demonstrating, organizing, and protesting emerge and inscribe themselves into the global political imagination. In the wake of last week���s negotiated agreement between the TMC and opposition leaders, it is all the more incumbent for those of us who identify as Pan-Africanists to be in dialogue with and learn from people on the ground who are strategizing about how to maintain the channels for continued resistance.

What role for the Black American left on Sudan?

Image credit Jedrek B via Flickr (CC).

In the wake of former Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir���s fall from power in April 2019, the Black Agenda Report (BAR)���one of the oldest and most respected Left black online publications (including a podcast) in the United States���published its first analysis of the uprisings that had been growing in Sudan since December 2018. The BAR published an article entitled ���Saudi Arabia, Israel, US all Sought Bashir���s Ouster: So how Real was the Sudan Revolution?,��� by a Chile-based journalist, Whitney Webb, who suggested that the uprising had merely been manufactured by Saudi Arabia, the US, and Israel. As a a BAR listener and a Pan-Africanist, I was disappointed both by the fact that BAR took so long to offer analysis on the events in Sudan, and by the simplicity of the analysis itself.

The author pointed to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf state actors��� support for the Transitional Military Council (TMC) as evidence to back their claim that foreign actors have manufactured the revolution. In doing so, the author is conflating the formation and leadership of the TMC with the popular uprising. To be clear, protests continued even after Al-Bashir had stepped down and the TMC had been established by military leadership. It is by now evident that even with Al-Bashir gone, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the US are interested in his policies remaining in place under new leadership. For example, Saudi Arabia is keen to maintain the presence of Sudanese troops in its war on Yemen.

Rather than pay attention to the months of organizing, or the root causes of popular unrest (most notably, adverse economic conditions), the author concludes that the Sudanese revolution began and ended with the arrest of Al-Bashir on April 11, 2019. By reducing everything to this event, the author bastardizes the term ���revolution��� that many of us associate with mass long-term organizing and protests. For months, organizers in Sudan coordinated the transportation of thousands of protestors from throughout the country to participate in marches and sit-ins both within the capital city of Khartoum as well as smaller cities. Protestors established neighborhood committees to maintain communication without the assistance of the internet. Attending a rally on June 30th in London in solidarity with the Sudanese revolution, I was speaking to a Sudanese friend who is active in the protests. When I mentioned the BAR article, she responded, ���tell them to come to Khartoum, I���ll show them how real it is.���

The BAR has long been committed to offering critical analysis of global empire and the racist, anti-black, and colonial logics that undergird contemporary global politics. In this vein, it has raised important questions about the interests and motivations behind Al-Bashir���s indictment by the International Criminal Court. Yet it appears that BAR���s critique of the ICC on Sudan has rendered it incapable of listening to those with the most at stake in the future of Sudan. BAR���s single-minded focus on the dismantling of US and European empire has had an unintended blinding effect towards popular demand for change.

The April BAR article is representative of a paradigm that has rendered self-identified Black American Leftists unable to recognize the emergence of grassroots uprising on the African continent. The conventional position continues to hope for a revolutionary Black consciousness on the horizon yet to come, or to lament the distance we now have from the material and ideological successes of the 1960s and 1970s. In other words, we have lost our sensitivity to revolutions that are actually already existing. The dismissal of such uprisings renders little practical difference between the Black American Left and the social and political scientists of Euro-American universities whose analyses following the so-called Arab Spring predicted that similar political mobilization was impossible or improbable in African countries south of the Sahara. In each case, the analysis is either over-determined by empire or by the repressive nature of authoritarian regimes, rendering the African masses unthinking and unimaginative subjects.

What is lost in such accounts is the opportunity for the Black American Left to learn and to bear witness to the strategies and processes that have enabled nationwide organizing in Sudan, home to the oldest communist party on continental Africa. As members of the Black American left, the endurance of such an uprising on the continent should have garnered ardent attention. As marches and public protests in the US are often limited to highly curated events, negotiated with local police, we should pay attention to the organic and durable organizing that characterize the uprisings in Sudan. Our commitment to global liberation should open us up to how and when new revolutionary processes of demonstrating, organizing, and protesting emerge and inscribe themselves into the global political imagination. In the wake of last week���s negotiated agreement between the TMC and opposition leaders, it is all the more incumbent for those of us who identify as Pan-Africanists to be in dialogue with and learn from people on the ground who are strategizing about how to maintain the channels for continued resistance.

Demystifying the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Johannesburg. By Stanislav Lvovsky. Via Flickr CC.

In South Africa, ���The Fourth Industrial Revolution��� is proving to be a catchphrase with tiresome longevity. In a radio interview not so long ago, the prominent South African columnist Peter Bruce exclaimed, ���We���re actually in the middle of it, and we���ve done nothing about it!��� To be fair, President Cyril Ramaphosa has in fact established a commission tasked with recommending policies and strategies to prepare for this ���new frontier��� if that counts as doing something. While Ramaphosa will chair the commission, some of its members are high profile executives such as Calvo Mawela, the CEO of satellite television operator, MultiChoice as well as Shameel Joosub, CEO of mobile communications giant, Vodacom.

It is well-known that Ramaphosa has a penchant for tackling issues by assembling high level task teams of ���experts������credentialed business executives, academics and politicians. In classic Ramaphosa fashion, the effects of technology on the labor process and commerce is a puzzle solvable only if the right people are involved. Yet, part of why the visible evolution of technology happens so haphazardly and with a sense of menacing rupture comes by shrouding its underlying drivers in a mystery knowable only to these experts.

When South Africans started to realize that major banks had for the past year quietly retrenched workers in apparent efforts to ���digitize,��� anxieties about automation peaked. In a country with already staggering levels of unemployment, the panic is understandable. Obviously, real changes in technology are happening and earlier ones are becoming easier to adopt. The problem is that as we spend all our energy trying to understand the scientific intricacies of these developments, the balance of power that determine their pace and extent stand unnoticed.

If we understand capitalism as fundamentally concerned with maximizing profits within fiercely competitive markets���then the profit motive is what drives the introduction of technology, with the surrounding market pressures determining when such implementation is appropriate. Corporations then, will not always roll out new technologies from their advent, nor just because they improve productivity. Only when technology increases profits by reducing costs will it become worthwhile, that is, when the machines are cheaper than the workers they would replace.

This raises the predictable view of: surely, it must always be cheaper to use machines instead of humans. Seemingly���until one also realizes that this cannot be the case given that before Ramaphosa���s now frequent invocations of the phrase (although to his credit, he only mentioned it twice in the post-election State of the Nation Address), the onset of the Fourth Industrial Revolution has actually been with us since the dawn of the new millennium when optimistic futurists started trumpeting it. Despite that, most industries almost twenty years into the 21st century preferred to employ real people. The turning point, which is revealing enough, was in the hangover of the 2008 financial crisis when the use of machines climbed.

To better grasp the march of technological change���which upon scrutiny really shows itself to happen in fits and starts, it���s helpful to go back to one of the earliest, and as will be argued, most prescient theorists on the role of technology under capitalism: Karl Marx. For many, Marx���s name probably orbits around those of supposed techno-skeptics such as the infamous Luddites���the 19th century English textiles workers who destroyed machinery as a protest method���than it does around those who would encourage technological progress. However, Marx viewed the productive efficiency created by technology as opening new possibilities, including saving people from the drudgery of modern work. In the Grundrisse (Marx���s collection of rough notebooks published only after his death), he had this to say about machinery:

The free development of individualities, and hence not the reduction of necessary labour time so as to posit surplus labour, but rather the general reduction of the necessary labour of society to a minimum, which then corresponds to the artistic, scientific etc. development of the individuals in the time set free, and with the means created, for all of them. Capital itself is the moving contradiction, [in] that it presses to reduce labour time to a minimum, while it posits labour time, on the other side, as sole measure and source of wealth.

In short, Marx envisioned that the development of machinery would render the production of goods and services so inexpensive that it could provide fertile ground for a post-capitalist society. Part of this thinking has found contemporary expression in the slogan of ���Fully Automated Luxury Communism,��� a creed that champions technological expansion to abolish work, end class distinctions, and create a post-scarcity world of comfort, relaxation and luxury. This is a position advanced in a recent book by Aaron Bastani, the co-founder of left-wing British media organization Novara Media. Bastani argues that rising technology presents a threat to capitalism, breaking its internal dynamics which depend on scarcity.

Still, having spirited faith in technology alone to positively transform society can become as unhelpful as having doom and gloom misgivings about its place within it. Both surrender to what the Frankfurt School critical theorist Herbert Marcuse called a ���technical rationality.��� Per Marcuse, this rationality develops when technology and its instrumentality become a superimposing logic, one that molds technology as a force unto itself rather than being situated in and limited by a prevailing social, political and economic context.

Technology, as with everything in a classed society, is relational. Whatever impact technology has on society is shaped by the antagonism between the interests of labor and the interests of capital, chief of which is maximizing profits. But as Marx explains, technology can complicate the pursuit of profit as much as it benefits it. At the heart of this internal contradiction is Marx���s value theory, which at its simplest posits that if uninterested in making a profit, a firm would only recover enough money to compensate itself for the inputs of commodity production. However, seeing as they also want to pocket something extra, a new value is ���extracted��� over and above the inputs��� but it can���t be from the machinery or raw materials which are already accounted for at the point of production, and only from the labor time of the employee that transforms this matter (which is meaningless by itself), into something worth selling on the market.

The unpaid labor of workers is what constitutes this surplus value, and machines as a means of production merely contain the crystallized labor performed by other workers in the past. The function of machines is first to increase profits by pushing down labor costs while spiking productivity, made possible by paying whatever remaining workers the same as before, if not less. The conundrum for capital happens when market competition compels other firms to do the same, so gradually, the widening availability of technology cheapens commodities and eventually shrinks the profit margins that firms can attain.

This is why technology doesn���t take off so as to fully realize its promise. It is in the interests of companies to park in a goldilocks zone of just enough automation that keeps profits high and reduces labor costs, all without losing the very markets of consumers that have to buy what is produced. The randomness of the scale of when and how these rollouts happen, shadowed by the sense that ���something is happening������which is what most research is only able to definitively conclude, is simply because what ultimately happens is dictated by market pressures which chaotically fluctuate.

Grappling with the role of technology in South Africa is challenging. Consider that the lines of work often flagged to be at most risk of automation here is ���low-skilled, low wage labor.��� The groups of workers that come to mind are probably assembly-line workers or mine workers. That said, these sectors don���t seem to be facing the brunt of automation as suddenly as others. Conversely, workers in South Africa���s services industry, which include clerks, cashiers and tellers are the ones taking a hit. As it appears, it���s cheaper to replace workers in these sectors notwithstanding the fact that far-reaching labor saving technologies in the others have existed for some time.

But if we understand this phenomenon as a matter of class power and distribution, its curious happening makes a bit more sense. Mineworkers and metalworkers have strong union histories, with the nature of the work being more amenable to cultivating sector-wide solidarities when their interests are undermined. By contrast, a call-center operator, for example, has to spend the majority of their day endlessly interacting with customers such that human interaction becomes stultifying and alienates them from their fellow colleagues. It additionally helps that mining and manufacturing hold strategic significance in the South African economy, so resistance to sweeping and abrupt changes is more effective���at least in the short term.

Already, a host of heavyweight companies have announced plans to retrench workers in the last couple of months, most of them in media, communications and banking. Even though these announcements have attracted a flurry of media attention, what is mostly ignored are the labor struggles unfolding across the country, such as the ongoing 3-month long strike at Oak Valley Farm in the Western Cape over wages, housing and labor broking. Another was a devastating 9 day long underground sit-in at Lanxess Chrome Mine near Rustenburg against the unfair dismissal of workers, a lack of union recognition, and alleged sexual harassment (the strike eventually ended after some concessions were made).

The sad truth about labor especially in the developing world where unemployment is rife, people are desperate and unions have lost strength and militancy���not helped in South Africa by our largest trade union federation, COSATU (the Congress of South African Trade Unions) remaining tame and tethered to the pro-business Ramaphosa alliance���is that workers remain so easily exploited that a shift to new technologies doesn���t completely maximize profitability, not always. As this paper from the Center for Global Development points out, ���given widespread low-skilled manual routine work, work tasks that are prevalent in developing countries are easier to automate from a technological viewpoint,��� but at the same time, ��� labor is cheaper than in high-income countries, thus more competitive vis-��-vis machines, and there is thus less of an incentive to automate.����� In other words, the contradiction of automation in the developing world is that it is simultaneously more technologically feasible, but less economically so.

What is clear is that despite the chorus of complaints typically leveled by companies in South Africa about suffocating labor laws, they remain lax enough for the traditional challenges of the labor force to greatly prevail. And so even the infamous, aforementioned Luddites, viewed in history as oppositional to technology, were misinterpreted���and were originally just modestly engaged in class struggle hitting at the heart of labor���s fundamental relation to capital. According to the great Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, they were, ���using attacks upon machinery, whether new or old, as a means of coercing their employers into granting them concessions with regard to wages and other matters.���

Poor working conditions, low wages and constraints on organizing persist, with new challenges to worker���s power coming not by any outward and concerted effort from capital, but through a stealthy, mutating neoliberalism that brands job precarity and insecurity as labor ���flexibility��� and ���freedom.��� The move to the informalization and casualization of work sees the traditional risks of capitalist enterprise being directed away from capital and onto labor. This turn towards ���responsibilization��� undergirds much of what is being said about the Fourth Industrial Revolution too. Tshillidzi Marwala, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg and deputy to Ramaphosa on the commission recently wrote that, ���we need to educate our people so that they are able to understand these developments���Different skills are required; the 4IR demands critical thinking rather than memorizing facts.���

True as that may be, the regurgitated soundbites imploring people to upskill in order to prepare for its arrival is as political theorist Wendy Brown describes, ���the moral burdening of the entity at the end of the pipeline.��� Individuals become liable for undertaking the necessary strategies for surviving these structural shifts in the economy over which they exert little control, thereby becoming the ���only relevant and morally accountable actor.��� The role of capital, the agents precipitating these shifts, tectonic or otherwise���is obfuscated, and technological change is rationalized as purely a natural and inevitable process for which individuals must adapt or die.

What is to be done? Figuring that out is tricky. To be sure, properly understanding the direction of automation in South Africa is a worthwhile endeavor since much too much of the discourse recycles the trends happening in North America, Europe and East Asia when they don���t always comfortably apply to our situation. At the very least, it suffices to say that whatever ends up happening cannot solely be understood as an indomitable march of progress that leaves all helpless in its wake. Technology can be wielded positively, it depends on who���s doing the wielding���and so the answer really comes back to reviving a mass struggle politics in South Africa capable of articulating programs centering jobs and living conditions, with technology featuring only as the means to make things better, not the ends that pretends things are better.

If the South African Left ever gets its house in order, we will be prepared enough for the havoc outside. Getting too swept up in the Fourth Industrial Revolution buzz means surrendering to technical rationality, the consequence being that capital is well placed to manufacture consent for the new world that comes, under the guise of�� ���it���s just the way things are.��� While changes trickle in, we could consider agitating for cushions like a Basic Income grant as some on the Left have proposed���but even then it must be on the terms of labor to be a ���non-reformist reform,��� and not on the terms of whatever the Silicon Valley equivalent is here.

To do that, we must in any case rebuild the vision of radical and emancipatory alternatives, the world that comes is as contestable as ever. To quote Marcuse, ���Progress is not a neutral term; it moves toward specific ends, and these ends are defined by the possibilities of ameliorating the human condition.��� Technology presents new possibilities for the world we want to live in, ours is the challenge of specifying what that world is, and how we get there.

Quietly queer in Senegal

Cristian Leonardo, "Dakar." Via Flickr CC.

When in April this year, a video went viral of two high school girls kissing, Senegalese media reported about the “scandal” and the Islamic NGO Jamra was quick to accuse Sourire de Femme, the country���s only known organization for queer women, of promoting lesbianism. Over the past decade numerous of such “scandals” about the immoral behavior of women and queer persons (both male- and female-bodied) have featured in the media, causing strong reactions from society that warns of the moral decay of Senegalese society.

In the West, such reactions feed into the imagination of Africa as the most homophobic continent. Over the past two or three decades, dissident sexualities and gender identities, “Western but now increasingly globally circulating LGBTQI acronym, have taken center stage in debates in and about Africa. Western conceptions of Africans” problematic relation to sexuality is not new. When HIV/AIDS was discovered in Uganda in the mid-1980s and quickly spread to all corners of the African continent, sexuality became a serious concern and reason for action for many international donors and NGOs. Today, such global health interventions in Africa are accompanied with concerns for human rights, and LGBTQI activists in several African countries, supported by larger international financial solidarity and support networks, have been fighting for the recognition of their sexual rights with some measure of success: on 23 January of this year, Angola decriminalized homosexuality, and immediately criminalized discrimination based on sexual orientation; Botswana followed on 11 June of this year. Meanwhile the effort has met resistance in others: in May, Kenya���s High Court ruled against the repeal of colonial laws that have criminalized same-sex sexual conduct.

Whether successful or not, these cases demonstrate a growing international concern for sexual rights. The world seems to be�� on a quest to rescue the “closeted,” vilified, rejected queer African. But what if Senegalese tell a more complicated story of being queer, one that is not just dictated by homophobic colonial laws and utterly restrictive sexual normativity? I do not want to gloss over the serious violence, both psychological and physical, inflicted on non-conforming individuals, as an earlier article about gay life in Senegal explored. However, I want to expand our perceptions of queer life in Senegal, because mediatized attacks on homosexuals do not provide a complete story. What does queer life look like for the majority who never find themselves part of a mediatized “scandal”? In particular, how do queer women give shape to their queerness, navigating the simultaneous desires of same-sex intimacies, family life, societal expectations, and urban success?

Homosexuality is criminalized in Senegal, and the Senegalese sexual imaginary stresses the importance of heterosexual marriage and its concomitant proper (deemed natural) gender roles and behavior. Yet, when I visited one of my interlocutors, Fama, one last time before returning to the Netherlands, she told me that should she leave Senegal one day���a dream that she held and expressed to me in relation to the possibilities for same-sex marriage in the Netherlands (where I am from)���what she would miss most about her country were “the meetings of the koba”��(urban slang for homosexual, in use since the release of Wally Seck���s song koba yi). Despite official and societal denouncements of homosexuality, for Fama and many others it is the extensive network of friendly and erotic relationships that queers maintain that precisely makes Senegal the country they love. It is only if we move beyond the discourse of sexual orientations and gender identities, which has shaped both sexual rights activism and its antithetical political and social discourse of homophobia, that we can come to understand what it means to live a queer life in Senegal. Why? Because much of the everyday lived realities of queer persons in Senegal escapes discourse.

Queerness-beyond-discourse rests for a large part on the Senegalese value of sutura. Sutura does not have a direct, singular translation from Wolof into English, but it connotes discretion, modesty, privacy and protection. It signifies both an attribute you have and something you do: you can give someone else sutura by hiding their misbehavior, and you can show your sutura by avoiding certain practices, such as discussing sexuality with elders, or discussing homosexual practices in general. Sutura is easily seen as limiting the space for non-normative sexualities, but queer women in Senegal strategically employ sutura to navigate their same-sex intimacies, resisting precisely the normative framework that tries to deny their existence. This is enabled by the fact that, according to Wolof morality, shame is declared upon public exposure, and a bad deed that is not visible to others does not lead to dishonor. Opening up frontiers in the interstices between normative frameworks and individual autonomy, the juxtaposition of queer with sutura calls for a nuanced notion of dissent.

A mastery of the ethical practices of sutura thus allows queer persons in Senegal to navigate both personal desires and societal expectations while maintaining their status as jig��en bu baax (Wolof for good women). Quite different from the frontier that sexual rights organizations form in the public sphere, the queer frontier that young queer women in Senegal imagine and construct, is one that is flexible and responsive in time and space. It expands wherever it can, and it takes a step back whenever needed. The challenge is to know when and where to take a step back. Instead of getting involved in overt discussions in the public sphere, queer women choose a tactic that gives them more space to negotiate norms than the public sphere does: they do not speak. As many of my interlocutors regularly reiterated, in various versions: “the first enemy of your life is your mouth. If you want to succeed and live a long life: close it!”�� Instead of seeing such acts as straightforward surrenders to heteronormativity, we should see them as acts of social navigation that open up queer opportunities elsewhere. The following examples illustrate how different types of silence are used to negotiate space to enact same-sex intimacies. Another interlocutor, Lafia, was known by her friends and family for exclaiming “vie priv��e!” (private life) whenever someone asked her about her love life. And Hawa, a 30-year-old football player who dresses in masculine fashion and has shaved her head, always covers her head with a scarf whenever she visits her father, who is very critical of everything “un-womanlike” that Hawa does. Such demonstrations of sutura in public performance enables women to create space in the private domain, as well as allowing for the creation of queer public spaces such as organized clubbing, (birthday) parties, and sports like football.

By transforming sutura from a restrictive normative framework into an enabling asset, these women pave the way for a broader understanding of queer: as a constant, yet indeterminate, possibility to negotiate normative frameworks. They propose an alternative to an international queer frontier of overt resistance and protest, and suggest that the silences that sutura prescribe are productive for queering their urban environment. By navigating the simultaneous desires of same-sex intimacies, family life, societal expectations, and urban success, these women are exemplary for what Nyanzi (2014) calls Queering Queer Africa: a plea for queering Africa beyond the discourse on sexual orientations and gender identities, and recognizing instead how queer erotic desires and gendered subjectivities are embedded and played out in people���s diverse engagements in everyday life.

Queer does not necessarily mean fierce resistance and blatant rebellion against restrictive gender and sexual normativity.�� Queer in Senegal means making use of the ambiguity of normative frameworks like sutura, to negotiate these and to seek room for dissent in the vicissitudes of everyday life. Women may be quiet but they are also very queer.

July 13, 2019

The twin legacies of Ray and Dora Philips

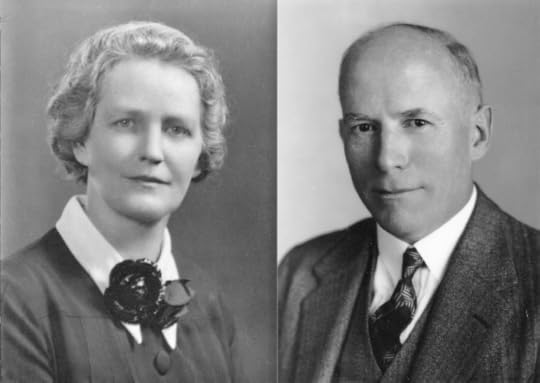

Dora and Ray Philips.

In April this year, South Africa���s government honored��Dr. Ray and Mrs. Dora Phillips, with the country���s highest national honor, The Order of the Baobab. The Philips worked in Johannesburg at the height of racial segregation and Apartheid and influenced a whole generation of black liberation figures, especially women. Ray and Dora’s philanthropy impacted millions of people of color.

Ray and Dora Philips were two American missionaries who had established the Jan Hofmeyr School for Social Work, the first of its kind for Blacks in the Southern African region, in Johannesburg. As historians Meghan Healy-Clancy and Jill Kelly reminded us at the time of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela���s passing the founding of the Jan Hofmeyr School would have far reaching consequences for liberation politics in Southern Africa. ���Students would become leaders in liberation movements across the region: for instance, Joshua Nkomo of Zimbabwe and Eduardo��Mondlane��of Mozambique preceded��Madikizela-Mandela, and the South African activist Ellen��Kuzwayo��was her classmate. Nelson Mandela was the school���s patron.���

There were some reports in local media about the ceremony, most notably on the country public broadcaster and most media mentioned the Philips along with the other awardees, but the achievement deserves wider celebration and reflection.

At the ceremony, South Africa���s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, said: ���The Order of Baobab in Silver is awarded to Dr. Ray and Mrs. Dora Phillips posthumously for their excellent contribution to the creation of the first social work network designed to improve the terrible living conditions of the growing population of the oppressed. They also established the South African Institute of Race Relations, one of the oldest liberal institutions in the country.��� (More recently, the SAIRR, famed for collecting social and economic indicators of Apartheid���s effects, has veered to the right and does not have the same kind of political influence.)

Ray and Dora Philips arrived in South Africa in 1918. They had graduated from Carleton College, a private liberal arts college in Minnesota and had decided to go work in South Africa. Carleton, about an hour south of Minneapolis, was started by the Congregational Church. The Philips arrived at Inanda Seminary outside of Durban, on South Africa���s east coast. The mission station at Inanda was started by the American Zulu Mission (AZM) in the mid-1800s. Ray and Dora absorbed for a year the spirit of upliftment and empowerment growing in their immediate neighborhood, most notably at the Phoenix Settlement established by Mohandas Gandhi and at the Ohlange Institute, the first industrial education school for blacks founded in 1900 by John Langalibalele Dube (the first President of the ANC at its founding in 1912) and his first wife Nokutela Mdima Dube, a previously forgotten pioneer, who herself, posthumously, was awarded the Order of the Baobab in Gold in 2017, one hundred years after her death at the young age of 44. She was the subject of my documentary film titled, uKukhumbula uNokutela/Remembering Nokutela��(2014).

Probably Ray and Dora���s most important legacy is training black social workers to tackle the multifaceted challenges of the growing black population in Johannesburg. In 1941, Ray founded the Jan Hofmeyr School of Social Work. The groundbreaking school was named for Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr, an Afrikaner philanthropist who served as Minister of Education and Finance in the Government of Jan Smuts. Its most notable alumni include the late Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and her fellow classmate, Ellen Kuzwayo (the women���s rights activist), Nkomo, Mozambican freedom fighter Eduardo Mondlane and younger graduates such as Dr. Brigalia Bam and Mrs. Esline Shuenyane, both of whom credit Ray and Dora���s mentorship and generosity as key to their success as anti-apartheid activists on the national and world stage. Given the school���s strategic importance, it was no surprise that Henrik Verwoerd, the architect of Apartheid, targeted it for closing in 1958, in spite of Ray���s efforts and protest:

It is most disheartening to realize that the Hofmeyr School of Social Work must close; to be replaced by courses in the Bantu rural universities. So tremendous is the need for social workers, especially in the towns! And these cannot be adequately prepared under rural conditions, even if the right staff can be obtained. We hope and pray for a last-minute reconsideration by Dr. Verwoerd and his Department.

Unfortunately, such a reconsideration never came. The school was closed in 1960, one year after the Phillips���s departure from South Africa.

For the past few years, as part of my research on the missionaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in South Africa (ABCFM or American Board for short), I had taken a lot of interest in the pioneering work done by Ray and Dora Phillips, and as a result, I networked with the United Church of Christ of Southern Africa-South Africa Synod and with the last survivors of the hundreds of female and male social workers trained by them.

From the outset, a key focus of Ray and Dora Phillips’s missionary work was providing the black youth and adult populations in Johannesburg access to wholesome leisure and entertainment activities. It is in the pursuit of this goal that they made the greatest impact on popular culture in South Africa. In 1924, he founded the Bantu Men Social Center,��at 1 Eloff Street, in the heart of downtown Johannesburg, where South African musicians like��Hugh Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa, Kippie Moeketsi,��Miriam Makeba, and many others, played their first concerts and built successful careers performing for mixed audiences. It became known as the only place where young blacks could access a tennis court (information from my old friend and mentor, the late Dr. Stephen Kalamazoo Mokone) and watch boxing matches and performances by touring American Jazz bands and athletes. Mrs. Esme Matshikiza, also a graduate of the Jan Hofmeyr School, said this about the center: ���The Bantu Men Social Center was very much the meeting place in the 40s and 50s ��� Very vital meeting place. People automatically met there. Everybody used to come there. It was really great.���

It is the place where many upwardly mobile blacks like the Sisulus, the Mandelas and others, had their wedding receptions and other special social occasions. In countering the critics who often claim that the action of Liberals like Ray Phillips was solely geared toward turning black people away from politics, one can point out that it is under the very roof of the Bantu Men Social Center that the very dynamic Youth League of the ANC was formed in 1946 by Anton Lembede, Peter Mda and Walter Sisulu. Ray played an equally nurturing role in the life of many pioneers of Black literature in South Africa: Peter Abrahams, the Dhlomo brothers, and many others satisfied their thirst for literature at the rich library of the BMSC, as it was commonly known among the black population of Johannesburg.

Ray was also a pioneer in establishing film viewership among blacks in South Africa with his introduction of movie nights first in the mine compounds and later at other venues around the city. This model is often cited by film historians of the former British colonies in Southern Africa. Charlie Chaplin, known as ���Sidakwa��� (the drunk little man, in Zulu) quickly became the audience favorite.

When I was informed that the Phillips would be honored, I contacted their granddaughter, Ann Phillips, a 1972 graduate of Carleton College, where I teach. She wrote to President Ramaphosa���s office about the tremendous honor it is for her late grandparents to be given this prestigious award.�� Anne Philips and her brother, Ray, and some cousins would attend the ceremony in Pretoria on April 25 at the Presidential Guesthouse. In the end, nine grandchildren and great-grandchildren attended the event, 70 years after Ray and Dora left South Africa. The visit by the Philips descendants and this official recognition generated a lot of excitement among both older and younger generations of social workers, in the UCCSA-South Africa Synod and at the Department of Social Development of UNISA and the Thabo Mbeki Foundation. An annual memorial lecture and other educational activities are now being jointly planned for the future.

Yes We Can���Football and Nationalism

Image by Ag�� Barros. Via Flickr CC.

The African Cup of Nations (Afcon), hosted by Egypt this year, is in its decisive stages. For football fans, this is an opportunity to watch the game together, to sing the anthem of their country together, to conspire against your opponent and insult the referee who is always too hard on our team and too tolerant of the opposition. The atmosphere requires the antagonism of “us” versus “them.��� It’s all part of the game and the show. Nothing bad in itself because it starts from a very good feeling.

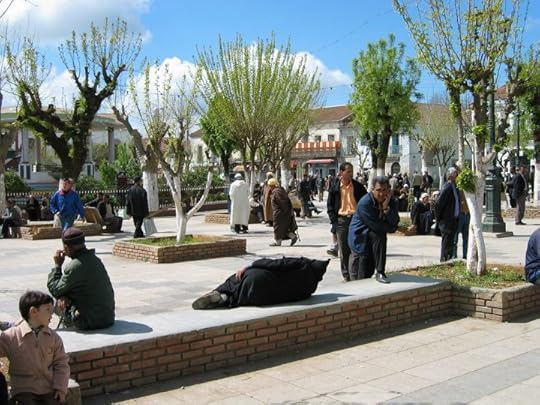

For Moroccan fans everyday life seems more or less to stop on match day. The Afcon reveals, beyond the symbolic stakes, the fundamental characteristics of our society: the merit of certain players to be on the field, the construction and representation of collective identities, socialization, solidarity between Moroccans and the projection of the socio-economic structuring of a large part of society onto the players.

This competition indeed represents a major event from a political, economic and cultural point of view. According to French sociologist Marcel Mauss, this ���total social fact��� mobilizes and exposes all the resources of those that participate in it. Participation costs a lot of money. Enough to fuel discussions and fire up detractors on the technical choices of the coach. This is not what concerns me here. Instead, I am concerned here with the expression of the passion, especially by our compatriots and our Maghreb neighbors. This nationalism that emerges from exchanges amongst each other around a football match.

Image credit Neil Faz via Flickr (CC).

Image credit Neil Faz via Flickr (CC).Yes, seriously, football contributes to strengthen the membership of the ���nation.��� We can even say that football is the nation. I have seen fans in the cafes chanting slogans that extol the merit of Tunisia or Algeria. My compatriots do the same. Friends have also invited me to share these moments in front of small screens to live the same emotions and enjoy these warm moments in this cold period. Otherwise we do not have so many opportunities to find each other. With tight schedules, opportunities are very rare, and the national team playing is of course a very good excuse. It is basically the only time we get to communicate around the Moroccan flag. The match begins and we are already dreaming of crushing Cameroon or Ghana by 3-0. This strengthens our sense of belonging and shared national feeling.

During those 90 minutes, we experience the same range of emotions. We move from one feeling to another: anguish, hatred, admiration, and joy in case of victory. And of course, we are stating all this on social networks. The red flag and the green star float and submerge the canvas and the profile photos on social media take on more vivid colors. We feel comfortable together as we participate in a national epic.

During those 90 minutes of the match, Moroccans from here and elsewhere are able to forget the daily problems, the heat wave, the cold, the human coldness, the flavorless meals, and collective experience the feeling of the “Nation” found again. We sing psalms and praises. As long as it lasts throughout the Afcon and a little more afterwards.

Morocco was knocked out in the Round of 16 by Benin on penalties, after they were pre-tournament favorites.

July 12, 2019

What is universal about the Algerian national ‘Hirak’?

Solidarity protest with Algerians in Columbus, Ohio. Image credit Paul and Cathy Becker via Flickr (CC).

���Revolution is an intense and dense reclamation of universal, not identitarian, human rights,��� wrote the Tunisian philosopher Fethi Meskini in the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution in 2011. This does not mean that national identity is necessarily incompatible with universality. On the contrary, the national, taken beyond the confines of nationalism as an ideology, is that through which the universal can manifest itself. By universal, I mean what is shared or sharable with humanity across, not above, difference. An irreducibly normative multiplicity marks the human experience, and it is across this multiplicity that the shared horizon of the universal lies (al-mushtarak al-inssani). Yet, the universal does not reduce multiplicity into oneness, but opens the one to the multiple. Following this understanding, a healthy national identity is a mode of expressing potentially universal concerns. The problem, therefore, as Meskini tells us, does not lie in identity per se, understood as a specific politics of belonging that structures the collective life of a people, nor in the phenomenon of belonging as such. Rather, it lies in the degree to which identitarian concerns are used by the modern nation-state to determine our subjectivity.

The use and abuse of these identitarian concerns by the nation-state is one of the reasons behind the ongoing national Hirak or ���movement��� in Algeria. The peaceful force of the massive protests marks a new beginning for Algeria. It signals the universal reclamation of the people���s right to perform who they are and who they want to be. Against a regime that turned fear over national security, which it generated, into a state mechanism of population control, the people peacefully asserted and enacted their own narrative about themselves. They performed their collective subjectivity by regaining the power over life without the ���security��� state���s bio-political mediation. The nation-state must be transformed, and a genuine, radical democracy is what people demand.

The Hirak began on 22 February after former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, old and ailing, decided to run for a fifth presidential mandate. People took to the streets in staggeringly large numbers, ending the ban to protest in public spaces since the so-called black decade of the 1990s, and demanding the departure of the president. After four weeks of relentless peaceful protests that swept the whole country, the president was forced to resign under the pressure of the army who appeared to have sided with the people���s Hirak. But that was only the beginning. The Hirak has continued, demanding the departure of the interim president and the current government, seen as relics of the old regime. The head of the army, Ahmad Gaid Saleh, has moved to the forefront of the political scene. He has stated many times that the army���s mission is to ���accompany��� the Hirak in its aspiration for a genuine democracy. However, the ambiguous and powerful influence of the army over politics has become the target of the Hirak���s increasing suspicion and criticism. This is due to the regime���s reluctance to engage with any initiative for a democratic transition.

The history of postcolonial Algeria���postcolonial in the historical sense that includes the colonial���has seen the army as a key player in Algerian politics since the War of Independence against France (1954-1962). The military branch of the National Liberation Front (FLN), which was behind the 1954 Revolution, had the upper hand in steering the country after independence. What followed was the story of the triumphant one party ruling the country with presidents who were military figures. However, the crisis of 1988 saw Algerians, fed up with the then deteriorating socio-political conditions, protesting against the government. The protestors were crushed by the army, yet the crisis led to the end of the one-party system and the institution of political pluralism. The Islamists made the most out of this transition, winning the first round of the 1991 parliamentary elections. Taken aback, the army intervened and ended the electoral process. As a result, the country plunged into turmoil that lasted for a decade, and the army maintained its power over politics. In the twenty-year rule of Bouteflika, who is credited with ending the black decade with his initiative of ���national reconciliation,��� institutional corruption and social inequality amplified, despite the relative economic improvement brought about by the country���s oil revenues. But the new generation, the youth of the post-black decade, became increasingly disillusioned. The ���Arab Spring��� did not spread to Algeria, but there were socio-economic protests in 2010 after which the government put an end to the state of emergency in place since 1992. In 2013, the president suffered a stroke which put into question his ability to govern. His brother, now under arrest, who was also his adviser, is said to have been the de facto president, with a powerful oligarchy around him, recently dubbed al-���issaba or ���the clan.��� President Bouteflika���s decision to run for a fifth mandate was the straw that broke the camel���s back. Now the people want a true civic democracy where the army and the old oligarchies do not meddle into politics.

This is the particular historical and social context of the Algerian Hirak. Yet where is the universal in this particularity? It must be pointed out that the universal here does not denote the antithesis of the particular, nor does it mean something that is by its very nature transcendental. Rather, the universal stems from a particular form of life or a mode of living, knowing, sensing, believing or acting that is socially, culturally and historically conditioned, but which has elements that are potentially universalizable within a ���pluriversal��� global context, to use Walter Mignolo���s term. In the light of this understanding, what is universal about the Algerian Hirak?

The nation-state is a modern institution of European provenance. In its postcolonial Algerian embodiment, the nation must be distinguished from the state. The latter, in the aftermath of independence, derived its power from the so-called ���revolutionary legitimacy.��� Its sovereignty, therefore, was not predicated on the will to representation, but was assumed in this legitimacy in whose name the regime seized the state and, consequently, monopolized the official identitarian discourse about the nation. This discourse became what Meskini calls a ���structure of identity,��� whose purpose is to turn individuals into consumers of a ready-made identitarian narrative imposed by the tools of legitimate violence. This structure of identity, however, cannot exhaust the nation and the way the individuals feel about the nation.

The word for nation in Arabic is ummah, but it also, and perhaps more accurately, translates as watan, which means a place where one resides, a house of one���s residence but also of one���s belonging. Algerians call it leblad, literally meaning the country, a word that connotes a shared space of living and belonging. This organic and spatial understanding of watan or leblad locates it, on the one hand, beyond ethnicity and race, and, on the other, outside the official discourse of identity imposed by the state, outside loyalty to the regime that speaks and governs in the name of revolutionary legitimacy. The Hirak, which witnessed the coming together of people from all walks of life, has moved the nation away from the state. Hirak means is a movement: people in active and politically conscious mobility reclaiming the nation as that house where all Algerians live and should live in dignity and freedom, the watan or lebled as a living space of freedom unexhausted by the state. In other words, the Hirak has placed freedom before identity, or, to put it differently, it has freed identity from the state���s monopoly. This means, crucially, that it is against the undemocratic appropriation of the state by the regime, not against the state as such.

The Algerian revolutionary past, thus, is no longer a source of governmental legitimacy. It has become one condition of possibility for a future genuine democracy. In this respect, not only is the nation imagined across time and space (Benedict Anderson���s thesis); it is actively reclaimed, reinvented and liberated as a (potential) house of democratic living by the bodies that are occupying the public spaces previously restricted by the state. The body of the citizen, thus, can regain its power over life with the aim of peacefully transforming the state on the condition of a free watan or bled. This peaceful, transformative movement���in the literal sense of the word���aims for a kind of political life that does not simply liberate the citizen from the state���s biopolitical control. It is a continuous movement���now entering its twenty first week���that seeks the transformation of the state itself after reclaiming the nation as a free space of living together, and not a revolution in the sense of violently ���turning around��� (the meaning of revolution in Latin) the state. This is the first universal element of the Hirak. Whether it succeeds to do (and how), however, remains to be seen.

Yet the healthy balance between identity and freedom, to draw again on Meskini, is not easily maintainable. With the Hirak in its fifth month now, not all the demands of the protestors have been met. People in the streets are demanding the departure of the interim president and the prime minister, both of whom are seen as illegitimate representatives of the people and therefore as ineligible to oversee the coming presidential elections that were set to take place on 4 July, but which are now postponed under popular pressure. In the meantime, the discourse of identity, even if it is liberated from the state, can be still distracting and divisive.

On social media, and especially on Facebook, the debates and discussions over possible initiatives for a democratic transition sometimes slip into fake quarrels over Algerian identity and what should constitute it. Some of these quarrels are widely believed to be fueled by state sponsored ���electronic warfare��� units under the auspices of various security apparatuses. These divisive identitarian discourses are also openly promoted by public figures, including some members of the parliament known for their proximity to the current military leadership. The movement holds these to be a part and parcel of a ���divide and rule��� strategy on the part of the those in power. By falsely pitting the ���Arab Muslim��� against the ���Berber,��� or vice versa, these exclusivist identitarian claims rest on a certain selective, and therefore distorted, knowledge of the past. This is the case with the recent vacuous principle of ���Badissi���ya Novembar���ia.��� Badissiya refers to the Islamic revival led by Abdelhamid Ibn Badis, the founder of the Algerian Association of Muslim Ulama in 1931. Ibn Badis had a strong vision and commitment to reform the Algerian society, which was under French colonial rule at the time, by reviving Islamic teachings and ethics. His, therefore, was an Islamic, social movement of reform, not a political or (as might be inferred) an Islamist one. Novemberia, however, refers to the principles of the revolutionary declaration of 1 November 1954, the starting date of the Algerian War of Independence, which the Muslim Ulama endorsed two year later. By an ideological sleight of hand, these two distinct elements were combined by some public figures to allegedly form the identitarian basis of the Hirak in its aspiration for a “new Algeria.”

The actual bodies on the streets, however, are maintaining the national unity of the Hirak and its unified multiplicity, laying bare the falseness of those quarrels and the triviality of identitarian discourse. What is more, it is on Facebook that the Hirak���s democratic force on the streets of the capital and many other Algerian cities is best captured and reported. Facebook here becomes a democratizing tool of disseminating news, a powerful alternative platform of reporting, representing and debating the Hirak. The latter���s organic force on the streets testifies to a mode of being-together that unifies the multiplicity of the people beyond any divisive discourse of identity, forcing this discourse to the margin of this continuous event week after week. In contrast to the UK and the US, where Facebook has come under suspicion over its controversial role in Brexit and Trump���s election, the Hirak demonstrates that it can still be deployed for democratic, not imperialist, ends. Democracy is everywhere jeopardized by the rise of ultra-nationalism. But in a country where a genuine democracy is determinedly sought, the unrelenting biopolitical reclamation of the power over life by the people in the streets has kept in check the virtual means that jeopardize it. Exclusive claims to identity are perhaps inescapable, yet the free collective performance and preservation of a people���s unified multiplicity can contain and isolate this exclusivist identitarianism in both the actual and virtual worlds. This is the second universal element of the Hirak.

These universal potentialities of the Hirak should not be understood as universal actualities. They remain potentialities that are open, promising and disruptive of imperialist ways of thinking about countries of the global South like Algeria. This imperialist mode of thinking often looks at the particularity of countries of the South in a way that obscures this particularity, seen not its difference but through the lens of the same, thereby foreclosing any potentially universal element(s) within it. Algeria���s ongoing, peaceful quest for a long-awaited, authentic democracy and a genuinely free society is yet to be realized, but it is essential to recognize that this particular quest, to be cautiously optimistic, can offer or inspire a universal hope for a better future.

July 11, 2019

All of them must go

Image credit RNW via Flickr (CC).

On July 5, Algeria���s Independence Day, the country���s citizens defiantly demonstrated that they, not the former revolutionaries clinging to power, are the true successors of the Algerian independence movement (also known as the Hirak). The national holiday happened to fall on a Friday, the day that has been dedicated to protesting the military-controlled government for the past 20 weeks. What was just a coincidence of the calendar took on a deeper resonance: parallels and contradictions between the old and new liberation movements rose to the surface.

���The past year, on July 5 2018, framed pictures of [ousted president Abdelaziz] Bouteflika were carried down the streets of Algiers,��� said C., a protester who did not want his name published for fear of reprisal. ���This year it���s the people celebrating their independence.���

For 57 years, Independence Day belonged to the ruling party, the National Liberation Front (FLN), which won Algeria���s independence from France in 1962. The political class is still largely made up of veterans of that struggle, including the 92-year-old Bouteflika. Now, Algeria must be liberated anew from a political elite that drew its legitimacy from the revolution. As a popular protest sign has it, the land was freed in 1962; now to free the people.

���It���s almost like a new independence for us,��� university student Fatima Boumediene (no relation to deposed Algerian president Houari Boumediene) said. ���Personally it kind of hurts my heart too, because FLN is what got us independence in the first place.���

But Algerians distinguish the revolutionaries, who they have a strong emotional attachment to, from the current power holders. The FLN as it exists today has left the country, as it was under French colonialism, ���a rich country with poor people,��� in the words of Roza Fidila, an exile from Bejaia who I spoke to at a solidarity protest in New York this spring.

Mohammed Mouaki was also among the many who left Algeria reluctantly but felt they had no choice. ���I lost both my sisters in their age of 50 for not having health care. My sister went to the hospital for a breathing problem, passed away three days after,��� Mouaki told me via text. ���The military go to France to be treated when sick and let the people die in Algeria.���

The FLN has come to exemplify everything it originally fought against and should be challenged in the name of the original liberation movement, said Khadidja Bouchellia, a PhD student who protested in Algiers.

���The remnants of the French colonization are manifested in a neocolonial regime that robbed the people of its freedom,��� Bouchellia said. ���I went to the protests on Independence Day to honor the legacy of my grandparents and to support my fellow Algerians in their fight.���

The difference between the revolutionary FLN and the party as an oppressive cartel has become more apparent as former freedom fighters like Djamila Bouhired and Lakhdar Bouregaa spoke out against the government. As reported by local media, Bouregaa, 86, was jailed on June 29 after criticizing military chief, and de facto holder of power, General Ahmed Gaid Salah.

Protesters on Friday were seen carrying pictures of Bouregaa. Drifa Ben M���hidi, the sister of revolutionary leader Larbi Ben M���hidi, who was assassinated by the French in 1957 and remains a national hero.

Thousands, defied a heightened police presence and blazing heat after noon prayers. Many volunteers in Algiers were seen spraying crowds with water to help cool them down, with the temperature reaching highs of 35��C.

C., who said he had been protesting in the suburbs of Algiers since early March, felt that a unique atmosphere reigned.