Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 216

June 11, 2019

We are all Haitians

Haiti. Image credit Siri BL via Flickr (CC).

The passing of J. Michael Dash on June 2 in New York City has left the academic community on both sides of the Atlantic in shock. As we come to terms with the weight of this loss, we should remember his many contributions to how we think, understand, and write about the Caribbean.

Michael Dash was born in Trinidad in 1948, one of a generation that had its intellectual coming of age in the heyday of independence in Trinidad and Jamaica after 1962. He went to Jamaica in the 1960s to pursue a degree in French at the University of West Indies (UWI) Mona campus. There was nothing unusual about this. The campus in the 1960s featured a healthy mix of some of the best and brightest students from across the region who interacted, collaborated, and sometimes married each other. The Mona campus at the time of Dash���s undergraduate years was a rich place for cultural exchange and intellectual growth. It had evolved greatly over the course of a decade from what an earlier undergraduate, Derek Walcott, referred to facetiously as ���the ranch��� to a gradually more developed place of ideas and culture. Dash would later recall, in a 2012 interview with The Public Archive:�����The Mona campus was the place to be in the late sixties. Lloyd Best, Orlando Patterson, Kamau Brathwaite, Rex Nettleford and so on were all on the faculty at Mona. The Wailers played at the Student Union fetes. We had had the Walter Rodney demonstrations in 1968, shut the university down and occupied the Creative Arts Centre. I think the times encouraged risk-taking.��� Mona was a place of great ferment for Dash and it became a major part of his adult life.

The influence of black consciousness had taken a strong hold on the campus.��Conscious students interrogated everything through the lenses of black history. A productive consequence of this was the curriculum change to include writers from the Caribbean in course material. Lecturers such as Gabriel Coulthard in Spanish taught material from the Spanish, French, and English speaking parts of the Caribbean, introducing students at Mona to areas underexplored in their earlier education. In a 1969 Twentieth Century French literature course, as Dash tells it, he learned about Aim�� C��saire and Frantz Fanon from Martinique and Jacques St��phen Alexis���who would be the subject of Dash���s first book���and Jacques Roumain from Haiti. The Haitian writers fascinated him. After winning a scholarship for graduate work under the direction of Beverley Evans (Omerod), Dash was encouraged to visit Port-au-Prince in April 1970.

This visit was during the last year of the dictatorship of Fran��ois Duvalier which was continued under the rule of his son, Jean-Claude. The news that reached the rest of the Caribbean about Haiti was universally negative. Indeed, most chose not to discuss Haiti let alone consider it seriously as part of the evolving radical Caribbean. Dash���s personal interests in Haiti were partly the influence of his advisor, the work of fellow Trinidadian CLR James whose The Black Jacobins cast a an enduring influence on Caribbean scholars of Dash���s generation, and his own curiosity to learn more about the source of the great literature he immersed himself in.

Dash���s commitment to study Haiti in 1970 was no small decision. No one save for David Nicholls���a British historian, who, significantly, was employed at the Department of Government at the St. Augustine campus in Trinidad���was working on Haiti in a serious way. Nicholls, who wrote the seminal From Dessalines to Duvalier (1979) often spoke of the logistical challenges of doing archival-based research in Haiti. Dash encountered the same challenges but persevered. Without the privilege of long-term research funding he would visit Port-au-Prince in the summers, reading all he could from Haiti���s giants���Roumain, Alexis, Price-Mars, Depestre, Marcelin, Nau, Chauvet, and others���finding their texts in private collections and the drawing rooms of close friends. The result of this devoted labor which spanned the seventies, was a doctorate and a major publication, Literature and Ideology in Haiti (1981).

To say that the book was important is to underestimate its value. Not only was it the first work in English to treat seriously and extensively with Haitian literature (Coulthard���s Race and Colour in Caribbean Literature (1962), based on studies made on trips taken from Mona to Jamaica���s neighbors in the 1950s, paved the way, but was more regional in scope) it more significantly placed Haitian literature firmly within the longer political development of the country. Dash drew connections between the voices of the generation that wrote against United States Occupation of Haiti (1915-1934) and those that opposed the internal fissures created by the arrival of the Duvalierist state in 1957. The book ended with Alexis��� assassination in 1961. A history that had remained obscure to an English-speaking audience was vividly made clear in this book through the words of the Haitian writers Dash closely analyzed.

As with many a great study its influence was not immediately registered. At a distinguished lecture at the Creative Arts Center on the Mona campus on the 200th anniversary of Haitian independence in 2004, Dash confessed that he felt alone as a scholar of Haiti at a time when there was very little interest in Haitian matters. He did not let this prevent him from more work. He followed Literature and Ideology with a range of important essays published in Caribbean and North American venues and the provocative, Haiti and the United States: National Stereotypes and the Literary Imagination, published in 1997. That book reflected the evolution in his scholarship. By tracing the way Haiti figured into United States stereotypes through literature, film, and art, from the nineteenth century to the 1990s, Dash made much larger arguments about the frequent injustices in US-Caribbean relations. By the time the book appeared Dash was established as a leading figure in Haitian studies, which, thanks in part to his contributions, was beginning to attract younger scholars, though, as he lamented, not many in the Caribbean.

This position afforded Dash a certain prestige. Being a Caribbean scholar with a global voice on Haiti who wrote and taught in the Caribbean gave Dash a unique view of Haiti vis-��-vis its relations with the rest of the world. When assessing the views of others he could be unsparing. In essays, critical reviews, and lectures he was as quick to point out the flaws in literary interpretations as he was in celebrating their virtues. Yet even when he made his most cutting remarks they were, at least in public, softened by an earnest laugh and a trademark smile that seemed to relax his tall frame when it broadened.

Dash consistently maintained the centrality of Haiti to Caribbean self-understanding. He encouraged students and colleagues to acquaint themselves with Haiti as much as they could. His underappreciated survey, Culture and Customs of Haiti (2001), reflected an unessentialized view of Haiti that most of his predecessors missed. Indeed in his work he was quick to point out many things that he believed observers in North America and the Caribbean had got wrong. In an article written for Jamaica���s Daily Gleaner in 2004 he wrote: ���Haiti cannot be saved by those on the outside if only for the simple reason that a modern democratic society can neither be imposed by the well-armed nor inserted by the well-meaning.��� ���No more helpful,��� he argued, ���are those who, blinkered by Afrocentric solidarity, reduce Haiti to the victory of 1804 and try to see Boukman or Toussaint in the face of every Haitian.���

One of his principal insistencies, made directly at the 2004 lecture in Jamaica, was that the idea of freedom, in art and life, was one that Caribbean people fully appreciated after the Haitian Revolution. His closing words at the lecture crystallized his argument that if we think of the modern Caribbean in this way as being connected to the Haitian Revolution, which James famously evoked as the beginning of Caribbean freedom, then we must accept that, ���we are all Haitians.���

Whatever forum he entered, Dash made clear that the Caribbean needed to be taken seriously. Even when his views collided with popular sentiment they were predicated on a sense that narrow ways of seeing the region, regardless of the politics of the viewer, were dangerous. He contributed frequently to local discussions on Haiti. He accompanied CARICOM members to Haiti on fact-finding missions; was a regular guest on radio programs in Jamaica; wrote in the newspapers; and gave public lectures. On a radio appearance in Jamaica in the early 2000s, he questioned why it was that the Jamaican media sought him out only when things go wrong in Haiti and not when there were improvements. It was a pointed comment that indicated years of frustration with the narrow-minded way in which Haiti was regarded by its neighbors who should know better.

After some two decades on the staff at the UWI, Michael Dash relocated to New York in the late nineties to take up a position as Professor of French literature, thought and culture. His departure was a loss for the UWI though he maintained a relationship with colleagues and the institution. He thrived in these years, publishing several other critical works on Haiti and the Caribbean. He also translated the works of the celebrated Martinican poet and philosopher, ��douard Glissant with who Dash enjoyed a close personal relationship. This work expanded his profile in the United States. His students and colleagues in New York were clearly impacted by his presence there. He supported his graduate students and selflessly mentored younger scholars with interests in French Caribbean studies.

I benefited greatly from his guidance and example. On my first research trip to Haiti in the mid 1990s I sought counsel with Michael in his office in the French Department at Mona. I found him packing up books for his imminent relocation to New York. It was my first meeting with him and he was genial and very supportive. He generously shared with me his contacts, especially that of the celebrated late historian, Roger Gaillard.

Before we parted Michael wished me well. He said Haiti is a place that for many of us from the Caribbean when we first visit we either are frustrated with it or love it a great deal. Michael loved Haiti a great deal. He loved the Caribbean a great deal, never missing a Trinidadian Carnival or any new work of art from younger writers and artists who caught his attention.

I have taught Michael���s work in my own classes on Haiti at the UWI. I preface discussions of his text with his biography and explain why students must know him. I have done so not only because of their enduring relevance but because I believe strongly that his achievement as a pioneering Caribbean scholar of Haitian studies should be appreciated by each generation who has the privilege of being at the UWI.

My last encounter with Michael was nearly two years ago in a museum in Denmark. We were there with his partner Stella, and scholar of Haiti, Marlene Daut, for a conference on Haiti at which we presented. On our final morning in Aarhus we explored the ARoS Art Museum together. Michael engaged us on new literature and old histories. All the while he offered insights on life and work, reflecting casually on the Caribbean as he lived it.

For those of us who were lucky to receive Michael���s reflections in person they were a link to a tradition of Caribbean intellectualism that he helped shape that is increasingly less visible. Fortunately for all of us his gifts are contained in his many writings; his books and the numerous essays that he left behind. This is the legacy that we must cherish as we remember him now. These, like good art, will live on.

June 10, 2019

The crisis of Ghana’s fisheries

Jamestown, Accra. Image credit Adam Cohn via Flickr (CC).

The fisheries sector in Ghana, beset with overfishing and a dramatic depletion of stocks, is facing an imminent crisis. There is widespread illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. As a result, there has been a significant loss of potential income for coastal communities. The country���s fishery sector creates jobs for 20% of the active labor force (2.7 million people), and industrial and artisanal fishing vessels compete for small pelagic stocks. In both sectors, there are severe political obstacles to addressing the crisis.

Currently, there are 82 registered industrial trawlers operating in the Ghanaian waters, down from the peak number of 103 in 2014. However, average fishing capacity of trawlers has been increasing, so it is not clear that the reduction in the number of trawlers has led to a reduction in total trawling activities. Trawlers are obliged to acquire licenses in order to operate. The licensing fees are the main source of government revenue from the trawling sector.

According to official data, catches from the trawlers constitute about 6% of total marine catches. However, this figure is likely to be an underestimation by a significant margin.

First, the Fisheries Commission (FC) lacks the capacity to determine actual catches: catch figures are based on self-reporting by the trawlers, which is subject to manipulation. Then, the trawlers actively engage in illegal fishing activities. Until recently, many trawlers fished within the inshore exclusive zones (IEZ), competing with artisanal fishers over the dwindling small pelagic stocks. Such species are disguised as by-catches (locally termed saiko), frozen in pallets and transshipped at sea to artisanal boats. These catches are not reported.

There are also weaknesses in the prosecutorial system for offenders. When trawlers are caught violating fishing regulations, the case may either be taken to law court or the offenders may opt for an arbitration arrangement known as Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), which often assigns less severe punishments. These settlements fail to deter offenders. It is alleged that many officials within the government have stakes in these businesses. By implication, any attempt at promulgating stricter regulation of the industrial fisheries face political backlash.

Canoe fishing constitutes, by far, the largest part of the fishing industry. More than 200 coastal villages rely on fisheries as their primary source of income and have limited alternative sources of livelihood or employment. Over the past 10 to 15 years, average annual income per artisanal canoe has dropped by as much as 40%. Like the industrial fisheries, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activities characterize the sector.

Canoe fishing has severe overcapacity. There are no license requirements and no fishing quotas. With limited opportunities for alternative employment, this creates a classic “tragedy of the commons” situation. Moreover, the government has limited capacity to enforce existing rules and regulations and has been unable to prevent the use of illegal fishing methods.

The government subsidizes premix fuel used by artisanal fishers. The premix fuel administration has significant political influence, and members of the political party in power benefit directly from the proceeds from diverted fuel sold to the manufacturing industry. Thus, the premix fuel subsidy has continued due to reasons of political expediency (to win the votes of artisanal fishers) as well as for financial gains to the political elites involved in fuel diversions to industries.

It is a major challenge to persuade canoe fishermen to scale down their efforts in the absence of alternative livelihoods. Any effective reduction in canoe fishing would have to be accompanied by a good strategy for creating alternative sources of income and employment. Without alternatives, it is unlikely that the fishers will voluntary comply with a policy which restricts fishing opportunities. Another problem is that the nature of electoral politics makes it extremely difficult to implement policies that restrict access to fishing for canoes. Political parties and leaders are reluctant to impose such restrictions, fearing electoral losses, since losing votes in fishing communities could prove decisive in elections. For the same reason, it is also politically difficult to cut or reduce fuel subsidies.

If efforts are made to limit canoe fishing, there is a risk that fishing communities will be adversely affected. Canoe-fishing communities are among the poorest communities in Ghana and rely entirely on fishing. Any restriction on fishing activities must therefore be accompanied by a direct support to the affected communities in the form of alternative employment, training and education or direct economic transfers. These challenges���elite interests in preserving the current system, limited administrative capacity, lack of trust in authorities, lack of alternative livelihoods and electoral risks���make it very difficult to limit fishing activities. Ultimately, the challenges are political. There are strong political interests, such as risks of electoral losses and resistance from political elites who profit from overfishing, that prevent the implementation of more sustainable fisheries management policies. Addressing them requires a strong political will and capacity to challenge the interests of those benefitting from the current situation.

Pan-African aspirations by neoliberal means

Image credit Simon Davis for UK DFID via Flickr (CC).

On 29 April, the Chairperson of the African Union (AU) Commission, Moussa Faki Mohamet, received the ratifications from Sierra Leone and the Saharawi Arab Republic for the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). With these, the minimum number of ratifications was reached for the Agreement to enter into force. Faki hailed the ratifications as a milestone, representing a substantial step in eliminating the fragmentation of African economies. AfCFTA entered into legal operation on 30 May 2019. It will come to market on July 7, 2019.

The AfCFTA is a project of the AU to create a continental economic bloc. This free trade agreement, its promoters argue, has the potential to boost intra-African trade by more than 50 % through the elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers on trade. Through a single undertaking, AfCFTA seeks to achieve the elimination of most intra-African trade barriers at once.

As Quartz Africa reported after the agreement came into effect: “���In a nutshell, it means a single market of goods and services for 1.2 billion people with an aggregate GDP of over $2 trillion. UNCTAD, the UN���s trade body,��predicts��reducing intra-African tariffs under AfCFTA ‘could bring $3.6 billion in welfare gains to the continent through a boost in production and cheaper goods’.”

With average tariffs above 6 %, African businesses already face higher costs when they export within the continent than when they export to the rest of the world. By gradually eliminating tariffs on intra-African trade, AfCFTA seeks to make it easier for African businesses to exchange within the continent. AfCFTA is also expected to benefit Africa���s industrial exports by diversifying trade and encouraging a move away from commodities.

Officially, AFCFTA has its roots in an old Pan-African aspiration���namely, that African countries no longer import from Europe, but from other Africa partners. Several commentators from the continent have hailed the Agreement, seeing it as a ���game changer��� that will put ���Afro-pessimists��� on the ropes. This enthusiasm has also been echoed by international organizations, such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Intra-African commerce is currently meager, representing only 10 % of the continent���s total trade. The main impediment is transport and logistics costs. These infrastructure disadvantages reinforce other structural deficiencies, like the excessive reliance on commodities and the divergence of economic development.

One could hardly be against such a laudable goal such as increasing intra-African commerce. However, praiseworthy as it may be, one must question whether this quintessential neoliberal policy will be the most effective tool to achieve it���and what costs will be borne by African peoples. Three crucial issues need to be addressed concerning AfCFTA: (a) the vast disparities in the size and composition of African economies; (b) the differing ways in which African countries have integrated themselves to the world economy; and (c) the African nations��� ability to switch to less commodity-based exports.

With regards to the existing economic disparities within the continent, even the World Economic Forum acknowledges that a significant challenge in the harmonization of African economies is the wide variation in their levels of development. AfCFTA has the highest levels of income disparity of any regional free trade agreement, doubling the levels present in blocs such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). For example, whereas over 50 % of Africa���s cumulative GDP is contributed by three countries (Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa), Africa���s six island nations contribute just 1 % combined. As for Europe, Africa Check also reminds us that it has taken more than 60 years after the signing of the Treaty of Rome (1957) to create a European common market; furthermore, the European Union devotes almost a third of its budget to finance structural and cohesion funds, enabling the least developed member States to reduce their gap with the EU15. No such mechanism is envisaged for AfCFTA.

In fact, the economic diversity explains the different responses that African countries have had regarding AfCFTA. South African leaders, for instance, have expressed their full support for the trade bloc, as AfCFTA could particularly favor South Africa in terms of manufacturing exports. For example, South Africa���s automotive sector, which currently represents 58 % of the country���s total manufacturing output and almost 7 % of its GDP, is likely to expand as a result of the continental free trade area.

Other African nations have not been so eager to ride the free trade bus. Currently, there is much discussion in Nigeria about AfCFTA���s implications for employment and the potential damage to the Nigerian economy. Despite strong support for AfCFTA coming from many business leaders and commentators, Nigeria���the largest African economy in terms of GDP size���is yet to join the free trade bloc.

African leaders might have MERCOSUR or even the European Common Market in mind when thinking of AfCFTA, but the level of economic divergence amongst African economies is much more similar to that found in a different free trade bloc: NAFTA. And when it comes to disparities, NAFTA���s record offers valuable lessons for African countries���especially the least industrialized.

In the case of Mexico, the poorest member of the bloc, as a result of NAFTA, real wages decreased, GDP per capita barely rose, and labor conditions did not experience a significant improvement. As one study points out, Mexican wages in some industries were five times lower than in the U.S. before NAFTA; yet, even as U.S. wages stagnated, Mexican wages became nine times lower after NAFTA. In fact, NAFTA���s labor standards proved entirely ineffective, creating race-to-the-bottom incentives for U.S. firms to outsource production.

In the case of agriculture, between 2 and 4.9 million Mexicans engaged in agricultural activities became net losers from the free trade agreement, as NAFTA eliminated not only Mexican tariffs on corn and other commodities, but also other policies that supported small farmers. For Mexico, NAFTA has meant a four-fold increase of exports as a percentage of GDP, while making Mexico a manufacturing powerhouse in Latin America; but it has also meant the creation of a trade bloc in which its weaker member���s exports remain with low value-added, unable to diversify trade beyond the United States, which now concentrates almost 90% of Mexico���s foreign trade. If anything, because of the disparities between the United States, Canada, and Mexico that proved beneficial to certain conglomerates, NAFTA exacerbated the decline in working conditions and labor rights in each country, to the benefit of a few, concentrated sectors.

This history of this free trade area established in a context of substantial economic disparities must serve as a warning to African nations in their efforts to establish a similar scheme on a continental scale. As with NAFTA, there are no guarantees with AfCFTA that companies will refrain from threatening to outsource to other countries with a cheaper labor force, which would further weaken workers��� bargaining power and contribute to the widespread stagnation of wages.

Even though any comparison with NAFTA might seem far-fetched, considering that nations such as Nigeria and South Africa are not close to having the economic power of the United States, NAFTA���s lessons should not be discarded by Africa���s small economies. In comparative terms, the levels of economic disparity found amongst African countries are just as high as those found in Northern America. There is one important difference, however, when drawing comparisons between AfCFTA and NAFTA: Mexico already had a sizable industrial base when NAFTA entered into force; this is hardly the case with many African nations.

The other area of concern is the integration of African nations to the world���s economy. Despite the AU���s efforts to boost economic integration through the establishment of Regional Economic Communities (RECs), African economies continue to trade mostly with other partners outside of Africa. RECs have proven unable to facilitate and enhance intra-continental trade, in no small part due to the different trade agreements already in place between African countries and their partners in the developed world. This is especially the case with the European Union, which has already signed economic partnership agreements with several RECs. The vast presence of multinational firms in Africa has served to maximize the economic relations with Western countries even further, to the detriment of intra-regional trade. Instead of fostering continental integration, AfCFTA has the potential to hinder it even further, by facilitating benefits to those multinational firms already present in most African countries, as these firms will even have more incentives to concentrate their activities in the most competitive countries.

In other words, because of the current trade patterns of African nations and the presence of transnational firms, AfCFTA would serve to facilitate the movement of extra-African products���imported mainly from Europe���across Africa. The prospects of subsidized agricultural products from the EU spreading throughout sub-Saharan Africa are grim if one considers that African farmers make up more than half of the total labor force in this region. With this in mind, it is not difficult to see AfCFTA as merely creating a large African market, but with relatively few African products traded.

The third area of concern has to do with the ability of African nations to diversify their export bases, transitioning from commodities to high value-added products. But for this to happen, industrialization policies are key. Despite the ���Africa Rising��� narrative that started getting a foothold some years ago, no effective industrialization policy has been put in place. What is more, the share of manufacturing in the GDP in most African countries has actually declined in the last decades; if anything, the vast African labor force has moved out of agriculture in large numbers, but the beneficiary has not been manufacturing but services (the former sector admittedly less productive than the later). In the absence of strong industrial development policies, AfCFTA is not likely to induce the export diversification that its proponents argue.

To some extent, AfCFTA has the potential to contribute to the economic growth of Africa, to the creation of employment, and the reduction of poverty in the continent���but all will depend on the ability of each country to restructure their respective economies. The economic disparities among the 55 African nations suggest that the implementation of AFCFTA will be more challenging than expected. Many analysts already acknowledge that it will take time to reach tariff elimination agreements and adequate protocols to enhance intra-continental trade. As mentioned earlier, because of many structural deficiencies, the success of the African common market is linked to the construction of physical infrastructure and connectivity, as well as the creation of jobs and the integration of markets.

However, the near absence of such discussions in African policy-making circles when it comes to AfCFTA is disturbing. As the World Economic Forum further acknowledges, the lack of a comprehensive policy-making and preferential treatment for Africa���s most at-risk economies can make AfCFTA a driver (rather than an inhibitor) of increased economic divergence.�� UNCTAD already admits that countries will bear some tariff revenue losses and adjustment costs in the short-run, which may not be distributed uniformly across the continent. Others predict that several countries in Africa would become poorer in real income after the creation of the AfCFTA, as a result not only of losses in tariff revenues but also of the intensification of competition, coupled with the rise in world food prices.

International trade is not neoliberal per se. The idea of an African market was envisioned long before the emergence of neoliberalism. Kwame Nkrumah was one of the most avid advocates of an African common market, writing extensively on the subject; Walter Rodney lamented the lack of ���integration of the markets across large areas of Africa.��� However, Pan-African intellectuals spoke of an African common market, arguably different to what merely constitutes a free trade area. Furthermore, the fulfillment of this aspiration through AfCFTA is being carried out in a context of neoliberal globalization, in which deregulation, financialization, and rising corporate power are still rife.

Earlier Pan-African ideals were not only aimed at improving standards of living for the majorities; they were also aimed at reducing the inequalities amongst African countries in production and access to world markets. As Nkrumah put it, the prospective African common market had ���to eliminate the competition [existing] between us,��� beating ���the undercutting tactics of the buyers who set us one against the other.��� Conversely, AfCFTA is taking place in a context of limited or non-existent redistributive policies, with many African leaders openly embracing the neoliberal consensus.

In all likelihood, AfCFTA will definitely boost intra-African trade. The AU will have to finalize the work on AfCFTA’s support instruments���rules of origin, monitoring, digital commerce, electronic payments and establishing the African Trade Observatory���in order to launch the operational phase of the free trade area.

Yet it remains to be seen how beneficial AfCFTA will be to African nations and peoples, taking into account its limitations. Without a minimum of redistribution among African states, as well as heavy investments in industrial and transport infrastructure, purely trade integration attempts may only marginalize the least competitive African States and regions. More importantly, it remains to be seen how this free-trade area will serve to foster the Pan-African ambition of a continental bloc that will no longer have to import from the Global North.

June 9, 2019

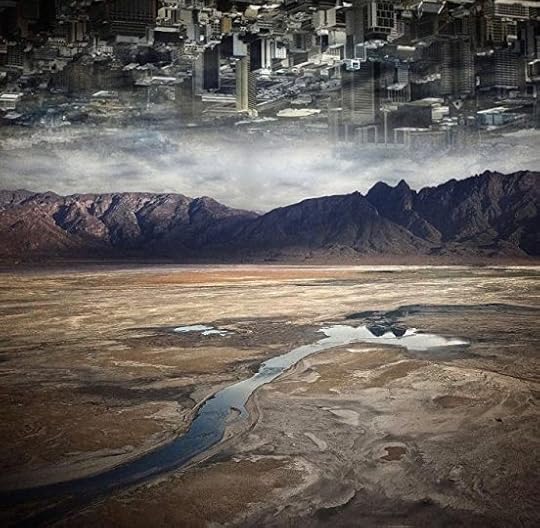

Scenes from a Dry City

From the poster art for 'Scenes from a Dry City"

The documentary film, Scenes from a Dry City, can feel disorientating. It jolts viewers from shot to shot, often without clear explanation of the context. Those unfamiliar with Cape Town and its racialized political ecology might not be sure where to focus or how to interpret events. Disorientation, however, might be one of the Fran��ois Venter and Simon Wood���s film���s strength. It enables a porosity between past, present and futuristic dystopias that uses the relationships between water, the state and citizens to raise profound questions about the character and stability of South Africa���s post-apartheid trajectory.

The film���s focus is Cape Town���s water crisis. In 2018, the city made international headlines, as years of drought and possible mismanagement brought it dangerously close to being one of the first major cities internationally to ���run out of water.��� Despite almost reaching ���Day Zero���, the moment when the taps would run dry, 2018���s heavy rains temporarily saved the city. While restrictions remain in place, the City of Cape Town has lowered them to Level 3, limiting consumption to 105 liters per person per day. This is more than double than just over a year ago, when the film was shot. At the time, with restrictions set at Level 6B, Capetonians were restricted to 50 liters.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the experience of the water crisis fragmented along the city���s racialized economic geographies. The film depicts these geographies in almost universally recognizable ways. Cutting between shots of outdoor toilets in township areas and images of wealthy suburbs, it illustrates how, even in moments of shortage, surplus appears to be available for the wealthy. More subtle, however, is how water usage and race shape relationships to the state. The film opens with an action sequence. The police are on the hunt for an ���illegal��� car washing business in one of Cape Town���s black township areas. Initially shot from the view of the police, viewers are brought into the narrative as if they are on a hunt. The targets are black men. As the police reveal their presence, the men flee. A few minutes later, we see police peering over the walls of working-class Coloured households to check for water infractions, entering properties to check their water usage.

The police���s interactions bring the past into the present. It is almost impossible for any South African above a certain age to see shots of police running after fleeing black men in townships to not have a deja v�� moment of apartheid militarization of black residential areas. Similarly, the peeking over walls and entering home spaces echo urban legends of police peering through windows in attempts to catch couples breaking apartheid���s Immorality Act, which forbade sexual relations between people of different racial categorizations. What Scenes from a Dry City draws attention to then are the perpetuation not only of the racialization of resources that characterized apartheid, but the longevity of the securitization practices that accompanied this. In contrast to these securitized relationships, we introduced to a wealthy white suburban resident who is getting a borehole drilled so that she can preserve her garden. No police interrupt, even though, by January 2018, borehole usage was meant to be monitored. While frustrating and life changing for all Capetonians, restrictions only transformed into violence for some.

With these haunting images of race and class inequality marking the viewer���s experience, the film ends on a fundamentally ambivalent note. At certain moments, in others we are proffered possibilities of hope. A protest against the privatization of water suggests push back against the market logics that perpetuate historical inequality. Those familiar with post-apartheid South African politics will know that the struggle against the privatization of water and electricity has been one of the period���s most prominent areas of mobilization. However, the protest seems to go nowhere. We are rapidly taken back to someone driving a golf cart through lush green lawns. Despite mobilization, surplus remains in privatized, largely white, wealthy spaces. Inequality initially appears overcome in the idyllic scenes of cooperation shown at the Newlands Spring. This public water source, located in an elite Cape Town neighborhood, for years not open to everyone, appears to bring people together. People of different racial categorizations stand side-by-side to collect water. Gradually, however, the viewer realizes that some of the Black poor are collecting and transporting water for wealthier white residents. Equality turns out to be a myth, racialized labor relations persist.�� As the film draws to a close we are presented with the only genuine but fleeting moment of community building ��� a mass prayer meeting. South Africans from a variety of backgrounds congregate against the pending apocalypse. As the rain suddenly returns and rescues Cape Town, the film suggests that only divine intervention might resolve the city���s, and, indeed, the country���s problems. Scenes from a Dry City, therefore sends a profoundly ambivalent message. On the one hand, change is possible. The existing practices of politics however, will not be the ones to deliver it.

June 6, 2019

Are the Russians forging an ’empire’ in Africa?

Vladimir Putin via Wikimedia Commons.

The��cover of��a recent issue of��Time��magazine left��little to imagination. It featured��a menacing looking president of Russia, Vladimir Putin, looming over a globe dotted by white location pins bearing red stars. The issue���s feature article claimed in its title that Russia was��engaged in a wide-ranging��and largely successful��effort to cobble up an empire of failed states and rogue regimes, many of��them on the African continent.��Almost simultaneously with this��Time��piece, the��New York Times��published��a lengthy article on Russia���s alleged military expansion across��Africa. Putin���s Russia, asserted the article, seeks out openings in the regions and countries where the rule of law has been compromised or non-existent. In the absence of US interest and commitment on the continent and against the background of America���s ���disengagement��� under Trump, the Russians are staging a��post-Soviet��comeback in Africa���as the famous Russian saying goes ������������������������������������������������������������ (a holy��space won���t stay empty).

Such reports of Russia���s expansionist policies on the continent have proliferated in the last couple of years, and reached a crescendo in the aftermath of��the mysterious murder of three Russian opposition-financed journalists��that took place in the Central African Republic (CAR) last summer. The tragedy highlighted Russia���s growing clout in an African country torn asunder by��civil and religious strife���it has been reported that Russian mercenaries and special forces now provide security for the nation���s beleaguered president Faustin-Archange Touad��ra. At the same time,��it was not lost on western reporters��that the former chief rebel and one-time president Michael��Djotodia��had been educated in the Soviet Union, where he resided for an extended period of time.

In Sudan,��the recently deposed��president Omar Hassan al-Bashir, the notorious long-time strongman, under indictment by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity,��engaged in direct diplomacy with Vladimir Putin and brought in��Russian mercenaries to help him curb��the��massive popular protests threatening his rule. If one��assumes, as many a western journalist��is��apparently prone to do, that these examples of collaboration between Putin���s regime and African strongmen are indicative of a broader and well thought out strategy of dislodging the western powers from their long-held positions of geopolitical arbiters then the panicky headlines and sensationalist reporting may well be justified. Yet knowing the uneven and difficult history of Soviet and Russian involvement in Africa one might counsel some caution.

The current flare-up of western concerns about Russia���s African expansionism is somewhat reminiscent of earlier such panics. In 1960, Americans had convinced themselves that Congolese nationalist Patrice Lumumba was in fact Moscow���s stooge. The consequences of these fears proved to be lethal for Lumumba and dire for the Congo. In 1967,��after the Soviets had thrown their weight on the side of the Federalists in the��Biafran��War, western observers��predicted Moscow���s rise as a major power broker in West Africa. A decade later Soviet and Cuban��involvement in Angola and the Horn of Africa were supposed to be the harbingers of another Soviet takeover of Africa. However, the reality of Soviet adventurism was far messier whereby the return on the investment of political capital and resources often proved to be��inadequate. There was little evidence that��Patrice��Lumumba harbored any particular affinity for Marxism-Leninism and plenty of evidence that he only reached out to the Soviets after having been rebuffed��(and insulted) by the Americans. The wartime honeymoon between Nigerian federalists and their Soviet friends hardly survived the war, while Angolans, even at the height of their Marxist-Leninist��phase, continued to profitably sell oil to the west. Even during the Cold War, when ideology did matter to some extent, Soviet commitments on the continent sometimes belied their claims to ideological purity. Much of the decision-making was motivated by crude pragmatism and opportunism. The��Biafran��War offered a case in point: in��that conflict, Moscow backed��a side that had absolutely no interest in any aspects��of Marxism-Leninism. In fact, the leadership of Biafra tended to be far more ���leftist��� in their outlook than their staunchly pro-western opponents in Lagos. In 1977, at the height of the��Ogaden��war, the Soviet Union readily dropped the ���socialist��� Barre regime in Somalia to pursue a more promising alliance with Ethiopia.

Obviously, the Russia of Vladimir Putin bears few similarities to the Soviet Union of Leonid Brezhnev. Yet��historians may want to acknowledge certain historical continuities. Now as then,��the Russians in their dealings��with their African partners claim to present an alternative model. Where the Soviets peddled the ostensible benefits of socialist modernization their Russian successors care little about socialism. But there is��also��a continuity of sorts, which can be generally summarized as a politics of anti-liberalism. While the Soviets assaulted western liberalism from the left, the twenty-first century Russian leadership challenges the west from the right or, on occasion, from a place that cannot be easily defined ideologically���there is a distinct postmodern aspect to their critique.��Putin���s regime has placed the principle of sovereignty and territorial integrity above the pieties of western liberalism; to Putin, democracy, transparency and human rights are far less important than stability. It���s a fundamentally conservative vision that emphasizes the zero-sum nature of global politics and places no demands on individual rulers beyond their ability to ���maintain order��� and provide business opportunities to the Putin oligarchy.

I would argue that contrary to common western apprehensions the Russians have returned to Africa not to build an ���empire��� of any sort but rather to pursue lucrative business opportunities. It is likely that the ���omnipotent��� and ���omniscient��� Putin is the product of a feverish imagination of those western observers who have been taken in by the ongoing handwringing over Russia���s alleged interference in the 2016 presidential elections in the United States. Whether or not Moscow actually influenced the outcome of the elections in any substantive way remains an open question, but the agony over��the election of Donald Trump may have inspired a search for other areas of Russian global mischief. Some of these anxieties are not entirely unfounded but it would help not to exaggerate the power and reach of Putin���s regime. But what about his despotic clients in Africa, kept afloat by their alliance with Moscow? one might ask. Well, as of this writing, one of Putin���s closest African partners, Omar al-Bashir,��finds himself��under arrest in Khartoum���overthrown in a military coup, which may have been an attempt to satisfy the demands by the��hundreds of��thousands of protesters.

June 5, 2019

Religion and conflict in Cameroon

A hospital in Southern Cameroon. Image credit Alvise Forcellini via Flickr (CC).

Much has been written about the��ongoing conflict��over the��status of the��Southern Cameroons.��The��genesis of the conflict��and the issues at stake have been��well covered elsewhere. What has not been clearly articulated is the role religion is playing in the conflict and the effect the conflict is having on the religious imagination in��the��region.��This piece suggests��that the conflict has��perhaps intensified the dynamics of suspicion and trust of religious��rituals and authority: Rituals and authorities��seen to��favor��the cause of separation are trusted��by the separatists while those who seem to��favor��other outcomes are treated with��suspicion and hostility��by them. The same goes for Cameroon���s military, which also treats with suspicion��and hostility all religious authority that seem��to favor the cause of the separatists.��This dynamic has affected��the major��religious rituals and authority in the country, such as��those connected to indigenous traditions, Christianity��and Islam.

Indigenous religious authorities��such as chiefs and��fons��(heads of��villages and kingdoms)��who��have, in the main, been treated as respected figures in their communities, have come under increasing suspicion��and targets of hostility��since the war began. This��suspicion��is not new.��Since the advent of multiparty politics in Cameroon in the 1990s, chiefs and��fons��have been treated this way.��Community members who do not support the ruling party of President Paul Biya (he has been in power since 1982)��have treated with suspicion and even disdain��those chiefs and��fons��who have supported��Biya���s��party, the Cameroon People���s Democratic Party (CPDM).��What seems new in the current conflict is that��the��suspicion has turned to murder,��and many indigenous leaders have been assassinated by separatists while others have abandoned their��people and fled for safety��to��other parts of Cameroon.��The government has also��treated with suspicion those chiefs and��fons��who have fled their communities, seeming to see them as��unreliable allies.��These leaders, who often mediate the��spiritual and the physical realms in their communities, are now seen as reliable or unreliable depending on the side they take in the conflict. Their social and spiritual authority are being eroded in the process.

Indigenous healers��have also come under increasing suspicion and hostility��depending on��the side to which they are seen to belong. Some indigenous healers are highly��respected by separatists because these healers are believed to have the ability to protect them spiritually against the onslaught of Cameroon���s army.��For example, these healers often perform rituals involving the cutting of the skin and the application of potions that are believed to protect the fighters against��bullets. This is similar to��the belief in spiritual fortification that characterized the��Maji Maji uprising��in��Tanzania during the colonial period.��In addition to these rituals, use is also��made of what is known as��Odeshi, which includes the��creation of various objects such as��bracelets, amulets, and others, that are part of the arsenal that renders fighters invisible��and invincible��to their opponents. Those indigenous healers who��are seen to be collaborating with��the separatists��have��become��targets��of Cameroon���s military and are sometimes��killed.

In��Odeshi, however,��we��see��a��m��lange��of��indigenous religious��and Islamic beliefs��and rituals. The amulets that are believed to protect the fighters��is��part of indigenous beliefs but��it is also connected to��the Islamic practice of��creating��amulets��that may protect one from the evil eye, for example,��as David Owusu-Ansa��describes.��Apart from the connection the amulets have to Islam,��one of the significant advocates��of the separatist cause is��Abdul Karim, who is often described in separatist sources as��a ���Muslim Scholar.��� He has emerged as one of the most trusted voices in��separatist circles.��Even though Muslim clerics have joined with Christian clerics to��call for peace��in the��region, these calls have hardly been taken seriously.

Suspicion of Christian authority��and rituals may be exemplified by two important��events. Christian Cardinal Tumi, the only Roman Catholic Cardinal from Cameroon, is a highly respected figure in the country. However, when he spearheaded the��effort to organize an��Anglophone Conference��in 2018��so that��the elite who hold various beliefs about the future of��Southern Cameroons could meet and begin the process of dialogue, he was rebuffed��by separatists.��Also,��when��the Prime Minister of Cameroon, Joseph Dion��Ngute,��posted on Twitter that he had met with some��anglophone elites��to pray for peace��in the region, many rejected��the event as posturing.��While some Christian leaders are said to have been killed by government forces, others have taken to making��diplomatic statements��that��would��not place them on the wrong side of any of the camps��in the conflict.��As��the war��goes on, it appears that the nature of religion��in Southern Cameroons is being redefined,��demonstrating that Cameroonians are hardly passive consumers of religion.

Climate, conflict and capitalism fuel xenophobia

The truck carrying South Sudanese refugees in Uganda. Image credit F. Noy via UNHCR Flickr (CC).

It is often asked where xenophobia���experienced predominantly and violently by black foreign nationals in South Africa���comes from.��It is a difficult question to answer, but the legacy of a racist and repressive state is��a common��starting point.��The prevailing status quo���a society deeply divided along race and class lines���can be traced back to colonization and Apartheid. Xenophobic violence��is generally��linked to��the��socio-economic inequalities, systemic unemployment and conditions of poverty that the majority of black African people continue to��suffer��in the��post-Apartheid��dispensation.

This��raises��serious questions��about the��current��democratic state, one in which��institutionalized��xenophobia��further exacerbates the crisis. Negative experiences of��foreign nationals,��especially vulnerable indigent people,��attempting to��access the asylum system��through the Department of Home Affairs are well-documented.��Their vulnerability��is compounded by policy shifts being promulgated by parliament���including removing the right to work of asylum seekers and��detaining asylum seekers in so-called processing centres at the border.

South Africa has a very progressive constitution, thus such policy shifts��go against the ethos and vision of the��founding document, which frames a rallying call for transformation and redress of the wrongs of capitalist��Apartheid.��As former Constitutional Court Judge,��Dikgang��Moseneke, argued��in 2014,�����our constitutional design is emphatically transformative. It is meant to migrate us from a murky and brutish past to an inclusive future animated by values of human decency and solidarity. It contains a binding consensus on or a blueprint of what a fully transformed society should look like.���

Yet, the recent elections��in South Africa��saw��both new and older��political parties opportunistically blame black,��indigent Africans��from the rest of the continent��for the state of crisis��in��the public health system.��This is disingenuously��extended to��blaming foreign nationals for the��economic crisis of chronic unemployment and crime, both consequences of rampant corruption and looting under the��rule of the former president Jacob Zuma and his cronies in the��ruling��African National Congress.��Such��othering and��scapegoating by both states and communities fuels xenophobic violence��in the country and beyond.

Movement of people is a global phenomenon.��The��United Nations��High Commission for Refugees��(UNHCR)��statistics reveal people��forcibly displaced��worldwide��increased from��65.3 million��in��2015 to 68.5 million in 2018.��Climate change is a critical factor in the��phenomenon.��According��to the��UNHCR:�����one person every second is being displaced by climate factors, with an average of more than 26 million people displaced by climate and weather-related events annually since 2008.�����In��some parts of the world this��increases��the risk of conflicts and worsening conditions for refugees and displaced people.

We��need to��understand how climate change impacts the current and future flow of refugees and displaced persons, and ask why��the��protection needs of climate refugees are not being met.��For example, the 2015-2016 El Ni��o phenomenon had a severe impact on vulnerable people in Somalia;��it worsened an already widespread drought in Puntland and Somaliland with a devastating impact on communities and their livelihoods, increasing food insecurity, cash shortages and resulting in out-migration and death of livestock.

More recently, Cyclone��Idai��hit Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe with horrendous impact, proving��(again)��that��vulnerable��people in countries contributing least to adverse climate change,��but with limited infrastructure and capacity to respond to��such��extreme events,��are experiencing its most devastating consequences.��In Mozambique alone, 1.85 million people are affected, nearly 200,000 displaced,��600 dead, and nearly 5000 confirmed cholera cases. Close to one million people in Malawi are affected, and nearly 100,000 displaced. Zimbabwe,��a country already in severe socio-economic crisis,��is now burdened with one quarter��of a million people affected, 300 dead and��16,000 households��displaced.

In December 2018, for the first time the UN Global Compact for Migration launched at a meeting in Marrakesh, Morocco recognizing��that the climate crisis is a driver of migration. Yet States are under no obligation to recognize the protection needs of climate refugees. There is an urgent need to put in place mechanisms that ensure the protection of climate refugees and this must be enforced. An international emergency must be declared, along with a plan of action to mitigate and eventually put a stop to the man-made carnage destroying the planet and its people.

The vulnerability of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants is used opportunistically by politicians globally. In South Africa this has the direct consequence of fueling xenophobic violence which results in the displacement of hundreds of people, loss and damage to property and in many instances the loss of innocent lives. States cannot ignore the scientific evidence which speaks to the dire consequences of the climate crisis. These facts must inform our policy. The SADC region must adopt an accessible SADC visa to manage the movement of people. Xenophobia and its consequent violence will otherwise continue unabated.

This��is an��edited version of��a chapter in the most recent volume in the series of Democratic Marxism entitled:��Racisim��after Apartheid�� [2019],��edited by��Vishwas��Satgar.

Climate, conflict and capitalism fuel xenophobia in South Africa and beyond

The truck carrying South Sudanese refugees in Uganda. Image credit F. Noy via UNHCR Flickr (CC).

It is often asked where xenophobia���experienced predominantly and violently by black foreign nationals in South Africa���comes from.��It is a difficult question to answer, but the legacy of a racist and repressive state is��a common��starting point.��The prevailing status quo���a society deeply divided along race and class lines���can be traced back to colonization and Apartheid. Xenophobic violence��is generally��linked to��the��socio-economic inequalities, systemic unemployment and conditions of poverty that the majority of black African people continue to��suffer��in the��post-Apartheid��dispensation.

This��raises��serious questions��about the��current��democratic state, one in which��institutionalized��xenophobia��further exacerbates the crisis. Negative experiences of��foreign nationals,��especially vulnerable indigent people,��attempting to��access the asylum system��through the Department of Home Affairs are well-documented.��Their vulnerability��is compounded by policy shifts being promulgated by parliament���including removing the right to work of asylum seekers and��detaining asylum seekers in so-called processing centres at the border.

South Africa has a very progressive constitution, thus such policy shifts��go against the ethos and vision of the��founding document, which frames a rallying call for transformation and redress of the wrongs of capitalist��Apartheid.��As former Constitutional Court Judge,��Dikgang��Moseneke, argued��in 2014,�����our constitutional design is emphatically transformative. It is meant to migrate us from a murky and brutish past to an inclusive future animated by values of human decency and solidarity. It contains a binding consensus on or a blueprint of what a fully transformed society should look like.���

Yet, the recent elections��in South Africa��saw��both new and older��political parties opportunistically blame black,��indigent Africans��from the rest of the continent��for the state of crisis��in��the public health system.��This is disingenuously��extended to��blaming foreign nationals for the��economic crisis of chronic unemployment and crime, both consequences of rampant corruption and looting under the��rule of the former president Jacob Zuma and his cronies in the��ruling��African National Congress.��Such��othering and��scapegoating by both states and communities fuels xenophobic violence��in the country and beyond.

Movement of people is a global phenomenon.��The��United Nations��High Commission for Refugees��(UNHCR)��statistics reveal people��forcibly displaced��worldwide��increased from��65.3 million��in��2015 to 68.5 million in 2018.��Climate change is a critical factor in the��phenomenon.��According��to the��UNHCR:�����one person every second is being displaced by climate factors, with an average of more than 26 million people displaced by climate and weather-related events annually since 2008.�����In��some parts of the world this��increases��the risk of conflicts and worsening conditions for refugees and displaced people.

We��need to��understand how climate change impacts the current and future flow of refugees and displaced persons, and ask why��the��protection needs of climate refugees are not being met.��For example, the 2015-2016 El Ni��o phenomenon had a severe impact on vulnerable people in Somalia;��it worsened an already widespread drought in Puntland and Somaliland with a devastating impact on communities and their livelihoods, increasing food insecurity, cash shortages and resulting in out-migration and death of livestock.

More recently, Cyclone��Idai��hit Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe with horrendous impact, proving��(again)��that��vulnerable��people in countries contributing least to adverse climate change,��but with limited infrastructure and capacity to respond to��such��extreme events,��are experiencing its most devastating consequences.��In Mozambique alone, 1.85 million people are affected, nearly 200,000 displaced,��600 dead, and nearly 5000 confirmed cholera cases. Close to one million people in Malawi are affected, and nearly 100,000 displaced. Zimbabwe,��a country already in severe socio-economic crisis,��is now burdened with one quarter��of a million people affected, 300 dead and��16,000 households��displaced.

In December 2018, for the first time the UN Global Compact for Migration launched at a meeting in Marrakesh, Morocco recognizing��that the climate crisis is a driver of migration. Yet States are under no obligation to recognize the protection needs of climate refugees. There is an urgent need to put in place mechanisms that ensure the protection of climate refugees and this must be enforced. An international emergency must be declared, along with a plan of action to mitigate and eventually put a stop to the man-made carnage destroying the planet and its people.

The vulnerability of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants is used opportunistically by politicians globally. In South Africa this has the direct consequence of fueling xenophobic violence which results in the displacement of hundreds of people, loss and damage to property and in many instances the loss of innocent lives. States cannot ignore the scientific evidence which speaks to the dire consequences of the climate crisis. These facts must inform our policy. The SADC region must adopt an accessible SADC visa to manage the movement of people. Xenophobia and its consequent violence will otherwise continue unabated.

This��is an��edited version of��a chapter in the most recent volume in the series of Democratic Marxism entitled:��Racisim��after Apartheid�� [2019],��edited by��Vishwas��Satgar.

June 3, 2019

The radical afterlives of Frantz Fanon

Still from film Fanon:��Hier,��Aujourd���hui�� (Fanon: Yesterday, Today).

When Frantz Fanon was in late stages of leukemia at age 36, he was flown to a hospital in Bethesda, Maryland��in the United States, for surgery. His five-year-old son, Olivier, walked in on an ongoing blood transfusion and, seeing the bags of blood, feared that his father had been cut into pieces. Little Olivier was later found waving an Algerian flag��on the street��since the brutal and ongoing Franco-Algerian war in which both his parents were deeply engaged was his only understanding of violence and blood in the world.

I was reminded of this heartbreaking story, included in David Macey���s Fanon biography, during the screening of Hassane Mezine���s film��Fanon:��Hier,��Aujourd���hui�� (Fanon: Yesterday, Today), which features Olivier Fanon, now an adult, reading excerpts from his father���s work. Interviews with him add a particularly melancholic note to the beautifully composed summary of Fanon���s life comprising the ���yesterday��� portion of the film���s first half. ���I was molded into the pro-independence scene of the Algerian war,��� Olivier explains as he recounts living underground because of the constant threat to his father���s life.

Mezine��encases Fanon���s story���a life lived defiantly for a short, energetic and prolific burst of time���between his beginnings as an 18-year old World War II soldier fighting against Nazism to his ���ultimate fight against colonialism.��� Here, the focus is on Fanon���s Algeria years, starting with his posting to Blida, where he was appointed chief doctor at the psychiatric hospital. Coming on the heels of the recently published Alienation and Freedom: Frantz Fanon, which has recuperated and translated almost two-thirds of Fanon���s work on psychiatry, the film also attempts to place Fanon���s psychiatric work at the center of his anti-colonial thought. It was in Blida where he was able to try out new, progressive methods in a place and moment where colonial, racist treatment of North African patients had become the norm.

Fanon was an intern of Dr. Francois��Tosquelles, who had asked the paradigm-shifting question, ���How can you treat patients if the institution itself is sick?��� and��had gone on��to invent institutional psychotherapy. Pushing these ideas further, Fanon completely reorganized activities and treatments at the hospital, adding art therapy, music, storytelling sessions, and even had a football pitch built on site. The film alternates between old and new images of the hospital in Blida, moving from the menacing photos of a rack of chains, handcuffs and belts to contemporary ones of people relaxing by the hospital cafe with a portrait of Fanon hanging prominently on the wall, evidence of the long-lasting structural changes he made there.

The films takes the viewer��through��Fanon���s time��as a revolutionary in the Algerian struggle through an intimate and personal lens���stories of friends who gathered over meals to have long, agitated discussions about the war; Fanon playing guitar and singing at a holiday party; Fanon pacing through his bare and unfurnished room, in which he dictated entire books to his then��assistant, Marie-Jean��Manuellan; Fanon pushing toddler Olivier on his tricycle. All these memory fragments allow the audience to access a sociable, congenial and vibrantly alive Fanon���someone always at one with a community, and who had boundless energy and ideas for fighting colonial injustice everywhere.

Still from film.

Still from film.A groundbreaking feature of this documentary is a simple one: a short portrait of Fanon���s partner in life and love, Josie. Epitomizing revolutionary love, ���Algeria served as a catalyst to bring Fanon and my mother closer,��� Oliver explains. ���She was there on the battlefield, on the borders,��� he adds, and indeed Fanon, Josie and Algeria were ���indissociable��� from each other.

While Josie Fanon has been left out of history books, this short homage does the necessary work of prodding and reminding Fanon experts to reckon with the extent to which revolution is continually framed as masculine, with women simply treated as temporary accessories to the larger project. Josie was a respected and beloved figure��who��continued working as a journalist in Algeria and was a strong ally of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, essentially remaining fearlessly engaged in politics until her death in 1989.

While touching on many new iterations in Fanon���s biography, it is the ���today��� section that forms the crux of the documentary. It contains the longer and meatier thesis: the idea that Fanon���s work has been transformative and influential, and that it undoubtedly possesses radical afterlives.

What, after all, is the relevance of Fanon today? Unlike��Che��Guevara, Fanon has not become a mainstream icon. There are no t-shirts, badges or tote bags upon which he appears, and this is simply because Fanon���s ideas are not easy consumption, nor do they lend themselves to short, pithy slogans. Yet as a global right wing movement now takes root, so too does a ferocious, belligerent and resistant��decolonial��ideology.

The documentary finds that Fanon has a lot to offer to today���s youth, who are disenfranchised by neoliberal economic policies, fed up of pernicious racism and heavily radicalized due to the ample online availability of a roster of contemporary injustice, inequity and corruption in the world. ���Misery is the unique destiny promised to hundreds of millions of humans,��� narrator Marie��Tsakala��stoically declares.

The film���s journey begins in Martinique, Fanon���s birthplace (where the documentary has been screened to enthusiastic audiences in massively packed auditoriums).��Mezine��was surprised at how little Fanon���s work is known in Martinique. Yet this eager reception is perhaps evidence that there is a desire to look underneath the mistaken stereotype of Fanon as an ���apostle of violence,��� and a real hunger to return to his ideas that might offer answers for a troubled present.

In Portugal, rapper and activist��Fl��vio��Almada�����LBC��Soldjah��� speaks of having been transformed by��Black Skin, White Masks.��A leader in ���Plataforma��Gueto,��� a black social movement that devises methods for popular education and community building,��Almada��claims that institutional racism and police violence towards the black population is entrenched in Portugal. Thus, the��Fanonian��notion that ���we revolt because we can���t breathe��� resonates urgently. Fanon���s ideas are important because they illuminate that it is not the fault of the marginalized people, and it is not their destiny, explains��Almada, but that racism and violence is ideologically organized, and can actually be decolonized, eradicated and overcome.

Traveling to France, South Africa and Niger, the documentary attempts to track the relevance of Fanon for a younger generation intensely cognizant of the fact that imperialism continues unabated in a host of creative and deceptive mutations. ���We are not the ���wretched of the earth��� that Fanon talked about,��� French-Algerian activist��Houria��Bouteldja��explains. ���We are the post-colonial subjects of Europe; we are the South in the North.���

Still from film.

Still from film.Hassane��Mezine��himself is very much a product of these ideas, and chose to make this documentary because of his ���Algerian identity,��� which became conflicted when growing up France. He explains that one is ���confronted with French republican myths about justice and equality that do not really apply when you are born out of French colonial history.��� For��Bouteldja, as for��Mezine, Fanon clarifies the processes of an internal colonialism, and his writing offers strategies to decolonize from these suffocating structures.

Exceptionally sharp observations come from the young activist��Ibrahima��Diori��in Niamey, Niger, who says that��Fanonian��ideas become particularly relevant as his country plays a pivotal role in exacerbating the so-called ���migration crisis.��� Divisive colonial laws between black Africa, white Africa and North Africa prevent an internal freedom of movement. As heads of states in these North African nations become brokers for European agendas, borders extend and proliferate throughout Africa, becoming ���a game of encirclement put in place by European anti-migratory policies.��� Despite statistics that prove, again and again, that the majority of migrants do not desire to enter Europe, but rather to travel freely within Africa, this discourse is promoted in the media as a justification of draconian and repressive border policies.

Diori��pleads for a simplification of relations between human beings, and Fanon offers him a bridge for these ideals of solidarity and unity. Journalist and activist��Salima��Ghezali��has similar reflections in Algiers, Algeria, and speaks of an internal racist discourse that has been furthered by the group Fanon referred to as the corrupt ���national bourgeoisie��� in light of refugees and migrants arriving from within Africa.

As the Fanon journey continues, it seems clear that women are at the forefront of these contemporary mass movements against racism, corporate greed and structural colonialism. This is further illustrated as��Mezine��ends with a beautiful section in Palestine with��Samah��Jabr, who is one of only 22 practicing psychiatrists and the sole woman in this profession in the West Bank. Deeply influenced by Fanon���s writings,��Jabr��explains that ���trauma described in western manuals does not look similar to the trauma we have in Palestine.��� She compares an oppressed group to a rape survivor who blames herself for the rape and wonders if she deserved it in the first place. An oppressed group like the Palestinians have to work through this immense inferiority complex, and activism inspired by Fanon���s theories can be therapeutic,��Jabr��adds. In a powerful symbolic move,��Mezine��projects Fanon���s words onto the radiant face of��Ahed��Tamimi, a teenage girl who was jailed for her confrontation with Israeli soldiers, inciting global outrage and protests.

Indeed,��Mezine��ushers Fanon into a twenty-first century generation that has, perhaps, never known colonialism proper, but has inherited all of its enduring brutalities. Portugal���s��Almada��insists that ���activists, rappers and academics must read Fanon, but not to transform Fanon into something fashionable. Fanon is for liberation.��� Elsewhere, Cornel West���s hypnotizing words on camera stay with us: ���Much of the world remains pre-Fanonian. But we will catch up with Frantz Fanon because many of us have decided that we want to be faithful unto death to his truth-telling, to his witness-bearing…���

As the melancholic strains of��Yazid��Fentazi���s��oud, which have accompanied us throughout the documentary, now give way to Tunisian musician��Neyssatou���s��fiercely blasted cover of Bob Marley���s ���War,��� there is a sense of jubilance. The mission might not yet be accomplished, but the stage has been set and the work of��liberatory��decolonization is being attempted in earnest across our planet.

Judgement Day

Still from Yommedine.

Around this time last year, Egyptian film��Yomeddine��(Judgement Day) was screened at Cannes Film Festival to great acclaim. The film, the first for writer/director Abu Bakr Shawky, is also the first Egyptian movie ever to be nominated for the Palme d���Or. The film���s success at Cannes was indeed a jumping-off point for sizeable international attention; and frankly, from my perspective, a welcome respite from the overwhelmingly politicized���and inevitably somewhat monotonous���content gaining broader attention in the last several years. Films like��The Nile Hotel Incident, or��Clash, while notable, seem on some level to capitalize on moments in history for which there is both fatigue, and, for many, sadness.

Still from Yommedine.

Still from Yommedine.Yomeddine��follows the journey of Beshay, a man who has recovered from leprosy, but bears its scars, and his young companion Obama, an orphan. Beshay, played by Rady Gamal, who Shawky met at the Abu Zaabal leper colony while working on a short documentary for a university project in Egypt, had no prior acting experience. Nor did Ahmed Abdelhafiz, who plays Obama. The film, while in part a commentary on how Egyptian society treats the abandoned, disabled, or those suffering from ailments deemed a risk, has an undeniable universality. The desire to turn away from that which makes us uncomfortable is a feeling we can all relate to.

This relatability situated in an unfamiliar backdrop, combined with characters that so naturally embody the underdog we wish to see succeed, is likely what lies behind the film���s international success. What I found perhaps even more profound than its reception among international audiences, was how it was received locally. It is rare that Egyptian films with global reach also do well locally. I remember sitting down in a sparsely occupied Cairo theatre to watch��Clash���which was released inside Egypt long after being widely screened outside the country. But inside Egypt, I had both friends and aunties speaking fondly of��Yommedine.

Still from Yommedine.

Still from Yommedine.While reviewed positively overall, it seems there were cultural nuances lost on some international critics. One reviewer, for example, calls the choice of the nickname ���Obama��� as ���slightly condescending��� and ���ill-considered.��� The unfortunate assessment of this particular cinematic choice was, I assume, made without knowing the prevalence of the use of such nicknames in Egyptian culture. Obama is a common nickname placed on those resembling the former US President either in looks, skin-tone, or both. One of Zamalek football clubs star midfielders, for example, is Youssef ���Obama��� Ibrahim, most commonly referred to simply as Obama. Whatever the intentions of the filmmakers, the use of this name becomes a commentary on Egypt���s relationship with race.

This same review seems also to take exception with the ���implausibility��� of several of the events that take place. This too seems a case of lack of cultural context. Roadside donkey theft and hitching a ride from a ragtag group of misfits, among other events in the film are indeed totally plausible in Egypt. That being said, improbable events seem to take place constantly in the country.

Still from Yommedine.

Still from Yommedine.Yommedine is an undeniably touching film, and one that shows slivers of richness, warmth, darkness, and humor, that many depictions of the country sorely miss.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers