Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 213

July 10, 2019

The unseen archive of Idi Amin

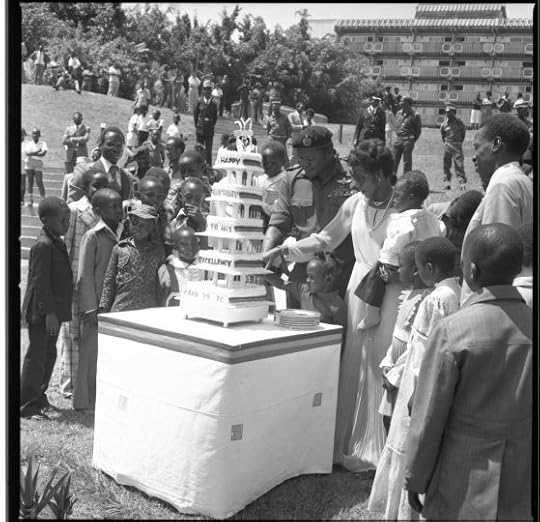

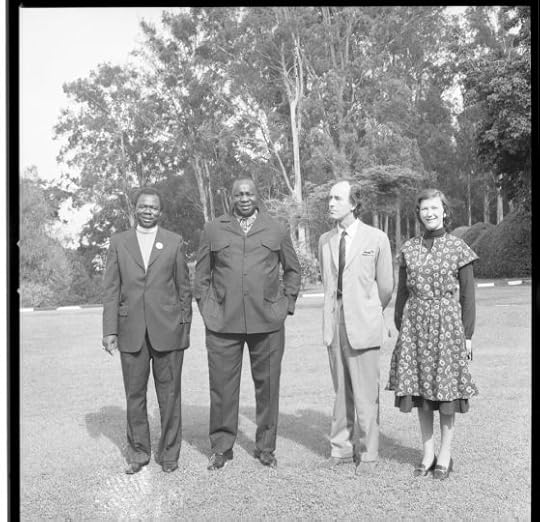

H.E. opens Jjajja Marina. 24 July 1975.

The recent discovery of a major archive at the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC) in Kampala is shedding new light on the photographic practices, and wider media engagements, of the Idi Amin regime (which was in power from 1971-79). The archive includes more than 70,000 photographic negatives, several hundred hours of radio records, and one hundred film reels, the majority of which were produced by the many official photographers, and other media professionals, who worked under Amin���s Ministry of Information.

Black Americans meet H.E. 11 August 1975. The delegation included Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan.

Black Americans meet H.E. 11 August 1975. The delegation included Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan.Idi Amin came to power on 25th January 1971, following a military coup against President Milton Obote. Amin enjoyed calling his regime a “government of action,” and he regularly launched public campaigns aimed at transforming Uganda���s economy and society. The most notorious of these was the “Economic War,” which began in August 1972 with the summary expulsion of the country���s Asian community. As many as 80,000 Ugandans of Asian descent���many of whom had lived in Uganda for generations���had to flee the country within 90 days. Beyond the public eye, the Amin regime was even more brutal still: during the 1970s, as many as 300,000 Ugandans died in prison barracks, police cells, and government-run torture chambers. Amin was eventually overthrown in April 1979, following an invasion led by the army of Tanzania.

By the time the archive was unearthed, in 2015, very few of the photographic negatives had ever been printed. Although all of the negatives had been developed and carefully placed into wax envelopes (each meticulously labeled with information about the date and subject of its images), very few of the images were ever used to produce actual photographs. They were never displayed, or published, in any forum. This was, quite literally, an unseen archive.

H.E. opens Jjajja Marina. 24 July 1975.

H.E. opens Jjajja Marina. 24 July 1975.In January 2018, UBC Managing Director Winston Agaba launched a project to digitize this unique collection of photographic negatives, as well as the Corporation���s holdings of radio and film reels. With funding and technical support from the University of Michigan and the University of Western Australia, the UBC���s dedicated team of archivists has to date digitalized around 25,000 of the negatives, as well as several dozen of the radio reels, and some of the film reels. It is hoped that this project will be the forerunner to a project that will create a much larger digital national media archive for Uganda.

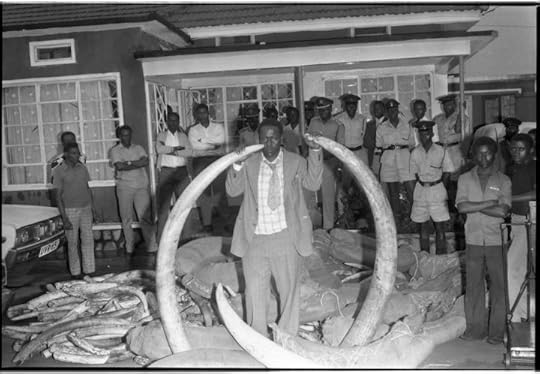

51st Birthday of H.E. 1 Jan. 1979.

51st Birthday of H.E. 1 Jan. 1979.In May 2019, an exhibition of 150 of the recently digitalized images opened at the Uganda Museum in Kampala, curated by the authors of this article. The exhibition���entitled The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin: Photographs from the Uganda Broadcasting Corporatione���will be open in Kampala until the end of 2019, after which it will move on to venues in several municipalities around Uganda (including to Arua, Mbarara, and Soroti), before traveling to international museums and galleries. A series of publications relating to the archive, including a photo book based on its contents, are also coming soon. So what do these previously unseen photographs reveal about the position of photography in Amin���s Uganda?

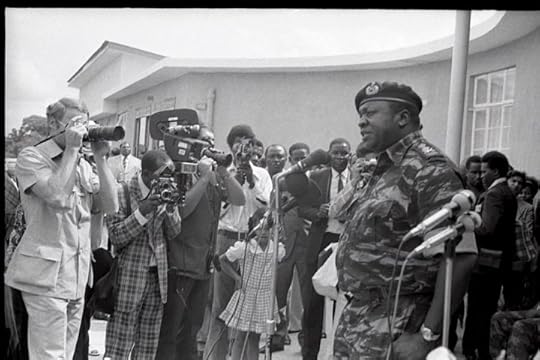

Smugglers of elephants tusks. 21 August 1975.

Smugglers of elephants tusks. 21 August 1975.Firstly, the sheer volume of negatives found here demonstrate the great emphasis that both Amin, and his senior officials, placed upon having all of their public engagements���including everything from their political rallies, to their visits with foreign dignitaries, to their many development “drives” (which were a regular undertaking for Amin���s “government of action”)���documented photographically. The fact that so few of the resulting images were ever printed or published suggests that the role of the photographers here was primarily performative. It was the presence of the cameraman that was consequential, not the pictures that he generated.

International Year for the Child. 1 Jan. 1979.

International Year for the Child. 1 Jan. 1979.Yet even if the photographs weren���t destined for printing or publication, the men who took them (all of the photographers were men) nevertheless worked either directly for the Ministry of Information, or under its accreditation. As a result, the images tend to represent Amin and his associates in a generally positive light; in ways that offer an elevated view of his government, and of its “achievements.” As curators of the exhibition, we were mindful that we did not want to display the photos here in ways which might reinforce this more propagandistic dimension of the imagery. In response, we held a series of participatory workshops at Makerere University (chaired by Derek Peterson), and in rural South-western Uganda (at anthropologist Richard Vokes��� long-term field site), in which Ugandan audiences were invited to respond to the digitalized images, and to share ideas about how they might be exhibited in ways that would deprive them of their proclamatory power.

Archbishop Janani Luwum with President Amin. Assassinated on 17 February 1977.

Archbishop Janani Luwum with President Amin. Assassinated on 17 February 1977.In the end, we decided that the best way to do this was to display the exhibition in two halves. In the first half, the photographs are laid out as a timeline, which presents images of grand state events, yet also includes portraits of the Amin regime���s victims, organized according to the date on which they were killed. This layout is meant to remind viewers about the reality of violence that undergirded the public life of the 1970s. In the second half of the exhibition, we have highlighted particular episodes from Amin���s Uganda���the expulsion of the Asian community, the Economic Crimes Tribunal, and the crackdown on magendo (“black-marketeering”)���in which innocent people became victims of the regime. At the end of the exhibition, we have also put on display images made by the photographers of the Uganda National Liberation Front government (which came to power following the overthrow of the Amin government in 1979). The UNLF photographs include pictures of the torture chambers that were used by Amin���s notorious intelligence agency: the State Research Bureau.

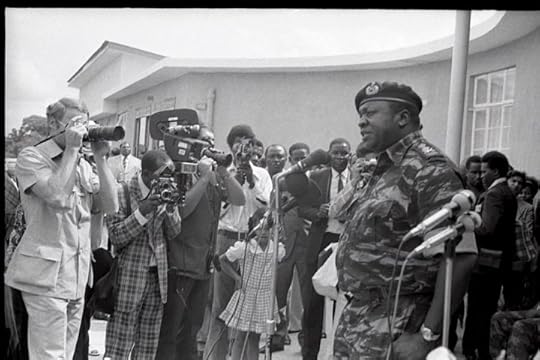

H.E. at a press conference in Command Post. 20 June 1973.

H.E. at a press conference in Command Post. 20 June 1973.The curators conceive of this exhibition at the Uganda Museum as a starting point, and a work-in-progress, rather than a final product. We hope that later exhibitions���including the ones that are already scheduled for Ugandan regional centers, and international venues���might include additional photographs, and other audio-visual material, to develop a more fully representative view of the experience of ordinary Ugandans in the 1970s, including of the friends and families of the approximately 300,000 Ugandans who lost their lives at the hands of the Amin regime.

If any readers of this article have photographs, or other materials, that they would be willing to share with us for this purpose, then please contact us at: amin.exhibition.2019@gmail.com

African Cup of Nations: A PR fiasco for Egyptian hosts

Image: Mark Fisher. Via Flickr CC.

Former coach and player Farouk Gaafar put his finger on Egyptian soccer���s fundamental problem even if his call for the military to take over and run the Egyptian Football Association (EFA) with an ���iron fist��� amounted to inviting the fox into the chicken pen. Mr. Gaafar issued his call after Egypt, once the undisputed king of African soccer, was knocked out (by South Africa) of the African Cup of Nations that it is hosting in a bid to bolster its international image tarnished by systematic violations of human rights. Egypt���s government is headed by general-turned-president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who initially came to power in a military coup.

Egypt���s bid has been marred by multiple events besides its poor performance in the tournament.

Fans exploited matches to honor legendary but controversial retired player Mohamed Aboutreika as well as the deaths of 94 fans in two separate politically charged incidents in 2012 and 2015. A legendary player, Mr. Aboutreika, who was consistently public about his politics, retired in 2013 after helping Egypt clinch three African Cups. He has since been forced into exile in Qatar after being accused of having been a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, a political group that Mr. Al-Sisi has brutally tried to crush.�� Last Novenber, Aboutreika was sentenced to a jail in absentia for tax evasion in what many view as trumped-up charges.

World soccer body FIFA, in a legally controversial move, took over management of its Cairo-based affiliate, the corruption-riddled Confederation of African Football (CAF), on the eve of the tournament.

As if all of this were not enough, Egyptian midfielder Amr Warda was initially banned early in the tournament from further participation amid mounting allegations of online sexual harassment, but then under pressure from his team mates (especially by star player, Mohamed Salah) reinstated.

Like many fans and some executives, Mr. Gaafar, who managed the military���s Talaee el Geish (Army���s Vanguards) Sports Club for seven years, blamed Egypt���s poor performance in the African tournament as well as last year���s World Cup in Russia on EFA���s lack of accountability.

EFA president Hany Abo Rida sacked national team coach Javier Aguirre and resigned together with the majority of the group���s board members hours after the Egyptian national team���s crucial defeat at the hands of South Africa.

���The state has done everything, but the football federation and the players have done nothing. There is nothing better than the discipline of the armed forces ��� football needs to be run with an iron fist,��� Mr. Gaafar said on a pro-government television show.

There is no doubt that Egyptian soccer desperately needs deep structural reform. The problem is that the state of the sport reflects Egypt���s broader structural problems. The country���s military is as much part of the problem as it is part of the solution.

Add to this the fact that a military takeover of soccer would deepen problems because it would violate FIFA���s insistence on a fictional separation of sports and politics and likely lead to a suspension of the EFA���s membership of the world soccer body.

Alaa Sadek, a Qatar-based Egyptian critic of Mr. Al-Sisi, moreover, noted that Egypt had failed to qualify for the World Cup in the 31 years between 1936 and 1967 that it was headed by a military officer.

Mr. Sadek charged that Egyptian soccer had recently failed domestically and internationally ��because Mr. Al-Sisi since coming to office in 2013, had turned the EFA into an ���army camp.���

Newspaper editor Gamal Sultan noted that the government and the military���s recent assault on the EFA occurred only after Egypt lost its decisive match against South Africa.

���Only last week, the EFA was clean, acceptable and patriotic. They were received by Sisi and the minister of defence and celebrated only when their victories served the image of the regime. One week later, the EFA has become corrupt and wanted for investigations. These are the standards of justice in today���s Egypt,��� Mr. Sultan said.

In a rare broad-based lifting of an eight-year old ban on unfettered attendance of soccer matches by fans, Egypt���s defeat in the African Cup was witnessed by 75,000 mostly Egyptian spectators, many of whom have long accused the EFA of mismanagement and corruption.

Egypt has with brief exceptions banned fans from stadia since the first day of the January 2011 popular revolt that toppled president Hosni Mubarak in a bid to stop soccer from being a venue for the release of pent-up popular anger and frustration as well as anti-government protest.

The government has made exemptions for international matches so that it could not be blamed for weak national team performance and to avoid putting the ban on international display.

More recently, small groups of fans have been admitted to domestic matches but only after identifying themselves with their IDs and with approval of their club.

Fans, nonetheless, defied bans on political slogans and jerseys during the African tournament by chanting Mr. Aboutreika���s name in the stadium and in online videos that went viral.

Fans also ignored rules imposed to prevent political expression by lighting up the stadium with their mobile phone flashlights during the South Africa match in commemoration of the 72 supporters that died in 1972 in a stampede and 22 others in another stampede three years later.

Many fans believe the incidents were instigated in an effort to intimidate fans and cut the most militant among them down to size.

Militant soccer fans played a key role in the 2011 uprising as well as subsequent protests, including against Mr. Al-Sisi���s coup that overthrew Mohammed Morsi, a Muslim Brother and the country���s first and only democratically elected leader.

The role of the fans highlighted the threats and opportunities posed to autocrats by soccer, the only thing that evokes the kind of deep-seated passion associated with religion.

As a result, stadiums as a public space that were contested and difficult to control threatened autocratic leaders��� grip on power. Yet, soccer���s popularity offered autocrats an opportunity to shore up their tarnished image by associating themselves with something that had immense public acceptance.

If anything, Egypt���s African Cup of Nations demonstrates, however, that exploiting soccer for political purposes is a tricky business.

Tweeted journalist Karim Zidan under the trending hashtag ���Team of sexual harassers:��� “Egypt’s national team is ��� its national embarrassment … Plenty of Egyptians are basking in the team’s loss today.”

Much like in the latter part of toppled Mr. Mubarak���s 30-year rule, Mr. Zidan was inferring that fans see the national team as Mr. Al-Sisi���s squad rather than Egypt���s.

In a country in which all expressions of dissent are brutally repressed, that is as clear a rejection of Mr. Al-Sisi���s effort to polish his and Egypt���s severely tarnished image as it gets.

July 9, 2019

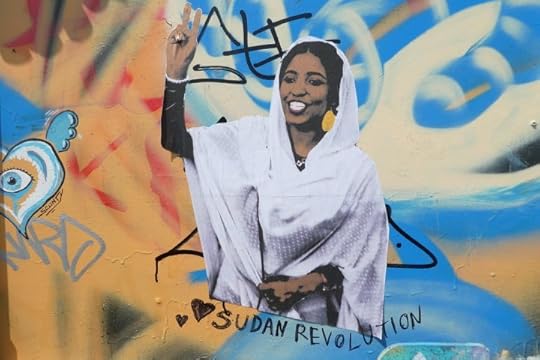

Solidarity with Sudan begins at home

Image credit Hossam el-Hamalawy via Flickr (CC).

After the news broke that security forces led by the Sudanese Transitional Military Council (TMC) massacred, beat and raped protesters in the early hours of the morning in Khartoum on June 3, calls for ���solidarity with Sudan��� spread across social media.��The TMC���ostensibly the body negotiating Sudan���s transition to democracy but widely understood to be a military regime set on keeping power���did its best to curb the circulation of news about the massacre by enforcing an internet blackout throughout Sudan. This meant that the majority of the calls for solidarity, and the responses, came from outside Sudan.

Logging on to the internet for the first time from Khartoum, more than a week after the atrocities of June 3, was a surreal and depressing encounter with the ways in which media attention can distort and sidetrack attempts at solidarity, even as it helps to disseminate information about injustices.

Much of the effort to spread the message about Sudan���s revolution and garner support for Sudan���s protestors has been taken up by the Sudanese diaspora, who have worked hard to ensure that family and friends fighting and dying in Sudan are not ignored by the rest of the world. Yet once that message circulated among those who were not already familiar with the Sudanese uprising, the calls for solidarity quickly lost focus. From relatively benign but ultimately unhelpful celebrity tweets to far more worrying calls for US military intervention, the rising storm of ���solidarity��� risked overshadowing the issues at stake in Sudan and provided little of use for those interested in pushing solidarity further than awareness raising.

A number of Sudanese commenters���both from within Sudan and in the diaspora���raised concerns about the lack of context and historical background displayed in some calls for solidarity, not only because they spread misinformation, but also because these calls often run counter to revolutionary solidarity within the Sudanese rebel movement itself. Claiming that the violence and abuse of the TMC is ignored because it is violence against Muslims, for example, erases the ways in which non-Muslim communities in Sudan have been targets of terror and discrimination throughout Sudan���s history, including during the recent uprisings.

These misjudgments point to some of the pitfalls of attempting solidarity across difference and across borders (as well as, less charitably, to the ways in which careers that capitalize on hurt and anger often undermine genuine struggles for justice). Some of these problems can be offset by listening closely to activists who work to inform the global public despite systematic campaigns by many states to repress information about rebellions. In the case of Sudan, twitter accounts such as @YousraElbagir, @BSonblast, and @ReemWrites all provide reliable and up to date information in English. Google Translate works more or less adequately for the many Sudanese accounts tweeting updates and analysis in Arabic, for example @wasilalitaha and @MuzNote. These sources and many others provide a wealth of information for anybody wanting to better understand exactly who and what they are standing in solidarity with.

Just as important as doing the research is using the lessons learned from it to inform action, wherever and however it is that we are able to act. For those living in countries facing similar troubles, paying close attention to both the victories and losses in Sudan can help guide future strategies for revolt. The timeline of the Egyptian revolution has provided useful context for the Sudanese protests and sit-ins, as well as the continued counter-revolution and is often referenced by Sudanese protestors. Libya provides valuable lessons about the dangers of both multiple competing centers of power in a post-revolutionary environment and international military involvement. Ethiopia, on the other hand, provides an example of the equally present dangers of foreign interference through international institutions such as the World Bank.

There is also a lot to be learned by supporters of the revolution who live in countries with contexts that feel distant from those in Sudan. One lesson that jumps out is that while individual struggles for justice are deeply embedded in their local contexts, the systems of oppression that allow for injustice to occur operate globally.

The massacre in Khartoum on June 3 may not have occurred without support from other international actors. For example, an EU program, known as the ���Khartoum Process,�����provided funds to organizations in Sudan to curb migration. Although the EU did not give funds to the Sudanese government directly, they also did not provide effective mechanisms of control. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF, commonly referred to as the Janjaweed) led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (also known as Hemedti), began patrolling Sudan���s border with Libya, stating publicly they were carrying out the EU���s agenda. (In addition, European countries like the UK and Italy have bilateral deals with Sudan on migration; the details of which are not made public.) These militias are known to be responsible for atrocities including murder, rape and mass displacement in Darfur. Today, they provide the strength the regime needs to suppress, abuse, and kill protestors around Sudan.

Others have left even clearer evidence of their support of the Sudanese regime and its security forces. Money from Saudi Arabia and the UAE in particular has kept the Sudanese regime afloat, giving the government a $3 billion aid package and producing pro-regime propaganda. This was likely in exchange for Sudan���s continued support of their war efforts in Yemen in the form of thousands of Sudanese security forces, primarily RSF. The Saudi war in Yemen has of course also been supported through arms supplies from the United States and the United Kingdom. (A court recently ruled that UK arms sales to Saudi are unlawful in a case brought by activists in the Campaign Against Arms Trade.) Russia is also known to have provided al-Bashir���s regime with strategic advice and are alleged to have trained Sudanese security forces through private contractors.

These global connections show that working in solidarity with protesters in Sudan can take place far away from Sudan itself���in any of the places that support the systems protesters are struggling against. For those of us with stakes in countries or institutions that exert their power globally, solidarity therefore has to mean first striving to better understand how the decision making of governments and institutions that are accountable to us do their part in supporting and perpetrating terror around the world. This isn���t a new insight. Internationalist revolutionaries have long understood that the hard work of global revolution begins at home.

Working to change the systems and institutions over which we do have some control, and using the information that is broadcast by those who are hurt by those systems, is probably the best we can do to stop horrors from occurring, and re-occurring. This can take the form of short term actions when we hear about crises that occur anywhere in the world. A concrete way of putting awareness into action is finding out what the roles of governments, companies and organizations close to home have been, in order to either support or obstruct them. Petitions, donations and awareness campaigns are all tools that can be used to this effect.

Then there is the work that takes sustained attention. This is harder than crisis driven solidarity that is based on shallow depictions of ���tragedies,��� which absolve the watching world of any complicity. It requires tracing the lines of neocolonial interference and uncovering the new patterns of global subjection, then using this information to inform our local actions. This work involves being politically active within our own communities while remembering to prioritize struggles elsewhere alongside our own. It means understanding and keeping at the forefront of our consciences the consequences in Sudan of our efforts to better the political systems we have direct access to.

Franz Fanon spoke directly to this kind of work when addressing the role of Europeans (and by extension European settlers across the world) in the fight of colonized people against empire. He recognized that while European governments and leaders were lost causes, there was still a chance that solidarity from their people could help to address the wrongs of colonialism. To do this, those claiming to stand in solidarity must ���first decide to wake up and shake themselves, use their brains, and stop playing the stupid game of the Sleeping Beauty.���

In Sudan, the TMC continues to orchestrate its counter-revolution���most recently with the announcement of a deal that will keep its key players in power for at least three years. It is important that the rest of the world keep watching as closely as it did after the acute crisis of June 3. This should include watching who supports these counter-revolutionary efforts, and how. In solidarity, we have to destabilize the global networks that support oppression and counter-revolution. Ultimately, we will have to use what we learn from Sudan to topple our own regimes.

Can women’s football be a game changer?

Image credit Andrew Ryan Turner via Flickr (CC).

Some comments that female footballers in Senegal regularly receive as they make their way to the football pitch, include: “Hey, go back to the kitchen!,������ ������is it a boy or a girl?������ or ������don���t play football, it will make you barren.������ Football is not deemed an acceptable leisure activity or career choice for women by everyone.

Large disparities were evident in the level of the teams that competed in the FIFA Women���s World Cup in France. Think of the 13-0 result in the United States vs. Thailand game, which revealed that women���s football has not developed equally everywhere in the world. This is as much due to the negative image of women’s football as it is the lack of money invested in the game in many places around the world. Perceptions are slowly changing though, and its status is quickly rising with the success of some of the teams.

This appreciation for women���s football may be precarious however: as a team books success, an opportunistic nationalism may inform the pride for the women���s team; but without success, women���s teams are quickly reduced to derogatory ideas, such as “lazy lesbians.” When Nigeria���s women���s team, the Super Falcons, failed to qualify for the Olympic Games in 2016 in Rio de Janeiro, lesbians were blamed. Despite the Super Falcons being Africa���s most successful football team, having won 9 out of 11 editions of the African Cup of Nations until then (and 11 out of 13 now), their poor performance in 2016 was blamed on lesbian relationships that “kill teams.������ The occasional alarmist stories in the media about the prevalence of lesbians in women���s football happen in parallel to a tacit acceptance of queer identities in women���s football. Particularly in West Africa, female football represents a public space for gender dissidence where young women���s masculine style and same-sex relationships are��tolerated.

Although various articles��reported recently the spectacular growth of women���s football around the world and on the African continent, what remains unanswered is how women themselves negotiate this status, and how they navigate the perceptions of their families and society at large for their engagements in football. How does the masculinity expressed by many female football players relate to societal visions of womanhood? Female masculinity in Senegal is captured in the category of jump, a self-identification of young women who embody a certain masculinity. Football women are often criticized for their masculine styles, which people link to lesbian identities. Most female football players in Senegal do indeed present in a masculine fashion, both on and off the football field. What is interesting is not debating whether or not these women are lesbians, but rather to explore how these women negotiate respectability and status, reconciling their gender and perceived sexual dissidence with normative expectations of womanhood.

Female masculinity is not restricted to the football field, but jump are most visible there. In fact, “it is the identity card of footballers,” said my interlocutor Hawa. She argued that the abundance of jump in women���s football is not a matter of expressing “true selves,” but rather “a way to show other hidden lesbians, that there is another one here… one who plays football… it���s a way to show girls, big ladies, others.” Despite its visibility, the nonverbal character of masculine dressing styles allows for discreet communication about its meanings and intentions, and follows the Senegalese value of sutura (Wolof for discretion, modesty) and a certain unspokenness of practices.

Jump female masculinity in Senegal is not only a way of making a same-sex desire readable for other women; it also addresses gender nuances between women and it is an argument against the universalizing tendencies of hetero-patriarchy to construct one vision of womanhood and of female beauty. The “imitation” of men has the potential to de-essentialize such identities and acts, revealing that they can be embodied from different positions and can thus take on new and unexpected meanings. Many football women adopt the names of famous (male) football players as a nickname, through which they express an aspiration to masculinity because of its promise of a certain mobility, autonomy and economic and social independence. They herewith present a simultaneous commentary on modernity and gender, both of which leave women out of positions as stars. By presenting themselves as these football stars, they make a fist against everyone who says that football is not a serious activity for women and they claim that they too can bring home pride, money, success, and responsibility: they turn an alleged male leisure activity that women should stay far from into a valid option for respectable womanhood.

On an organizational level, Senegal has some strong ambassadors for women���s football. Seyni Ndir Seck, former captain of Senegal���s national women���s team, has led the Women���s Football Committee of the Senegalese Football Federation since her election on 8 July 2017. In 2009 she had established Ladies’ Turn in collaboration with Jennifer Browning and Gaelle Yomi, an association that seeks to promote women���s football in Senegal through the organization of a biannual tournament. At other levels, football players and enthusiasts themselves find ways to advance the status of the game in Senegal. Yaye studied law at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, and although she had stopped playing football at the age of 13 at the request of her parents, she has been involved as the secretary general of one of the Dakarois women���s football teams for a couple of years now, having been reintroduced to the milieu via a girlfriend. She is particularly committed to advancing the status of women���s football in Senegal and she tries to do so among other things via the movement “Je suis football f��minin”��that she initiated. Reminiscent of “Je suis Charlie”��after the attacks on the office of Charlie Hebdo in Paris in 2015, her movement is a call against the stigmatization of women in football in Senegal. She established a Facebook group to update (female) footballers of their competition, as well as of developments in women���s football elsewhere. She also used the hashtag #jesuisfootballf��minin to comment on concrete cases of marginalization of women���s football in Senegal, such as when during one match, two players broke a bone on a sandy pitch full of stones���the proper fields had all been reserved for the men���s competition. Such efforts reflect the political potential of sport, where societal gender norms can be challenged.

Yaye���s goal is not only to promote women���s football as such however. She is also seeking to educate women on how to properly behave on and off the football field, in order to garner more respect from society. She explained to me:

The girls didn���t know what private life was before��� it is important that they know sutura and proper behavior. Some girls like to walk with their trousers below their buttocks. How can you expect someone to respect you then? Some girls just do not understand that not everywhere is the football field. I try to teach them the difference between private life and public life.

With her efforts, she shows how adhering to the Senegalese norm of sutura in her eyes enhances one���s respectability as a football player, while simultaneously defending the football field as a legitimate space for women to frequent, a space that only tacitly represents a queer space.

By carefully balancing their masculine presentation and active engagement in football with societal expectations of normative womanhood, jump have the ability to produce and accumulate transgressive capital: the opportunity to demonstrate gender transgressive behavior in the urban environment, and actually acquire status with it in the spaces they frequent, despite the simultaneous (official) denouncement of such behavior. This capital transforms with time and space, and it may be particularly attainable in the life stage that most footballers are in: below thirty and unmarried, when their behavior does not directly threaten the social order of marriage and procreation. Irrespective of its particular life-stage attachment, football women in Senegal negotiate respectability through various practices, whereby they critique binary oppositions between masculinity and femininity; men and women; and the respectable and the immoral. They clear the field for new generations of girls to join their male friends on the field and share their enthusiasm with their families���an important step in the advancement of equal chances for women and men. Women���s football is an important arena through which such changes can occur, and change will happen, slowly but surely.

July 7, 2019

‘They���re our Black Stars. We have to support them’

Ghana play England in a friendly football match at Wembley Stadium in London, Tuesday, March 29, 2011. Image credit

Akira Suemori for FIA Foundation via < ahref="https://www.flickr.com/photos/makeroa..." target="_blank"Flickr (CC).

With a few weeks to the start of the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations, the head coach of the Ghana Black Stars Kwesi Appiah surprised the nation by as the team���s new captain. This looked like a demotion for the previous captain, Asamoah Gyan, who had been the team���s captain and leading striker for years.

Gyan immediately announced his permanent retirement from the national team, citing the captaincy situation as the reason. President Nana Akufo-Addo surprised the nation when he��intervened and persuaded Gyan to rescind his decision and facilitated a ���compromise��� which involved Ayew being maintained as captain and Asamoah Gyan being named ���General Captain.��� Some Ghanaians remarked that they wished that the president had prioritized responding to floods and kidnappings over football.

This drama was the latest in what seems like a never-ending series of controversies involving the Black Stars and was received as an omen of another dramatic and ultimately disappointing tournament. The team has often been a unifying symbol of hope, but waves of disenchantment stemming from the corruption scandals involving the Ghana Football Association and disappointing results are threatening this. The Black Stars are beginning to feel like yet another failing state institution.

If there were a moment this disenchantment began, it would be on 26th June 2014. The Black Stars��� players had publicly threatened to boycott the World Cup if they were not paid their agreed fees, so the government loaded up a plane with US$3 million in cash and flew it to Brazil to pay them. Many Ghanaians understood why the Black Stars demanded their bonuses in hard cash before the end of the tournament. Our governments have been notoriously slow in paying debts, whether to the teachers and junior doctors who sometimes go up to 18 months before they receive a pesewa in salaries or to the contractors who construct roads and have to wait years to be paid. But this did not make the pain of the public humiliation and disappointment any less intense. When a photograph of defender John Boye kissing his wad of crisps dollar bills in the hotel corridor was leaked to the public, it was almost too much to bear.

To understand this perpetual state of being ���disappointed but not surprised,��� it is necessary to understand that the Black Stars are supposed to be���and used to be���one of the few national institutions that Ghanaians could be genuinely proud of. The establishment of the team was part of Kwame Nkrumah���s grand nationalist and pan-Africanist identity strategy, but the quick subscription from Ghanaians owed to the fact that there was already a bedrock of popular support for the football in the country. (Stephen Borquaye���s book The Saga of Accra Hearts of Oak Sporting Club charts this rapid spread of enthusiasm for the game from the introduction of football first into the Philip Quaque Government Boys School in the early 1900s to then its rapid spread of the game throughout towns in the then Gold Coast.)

In first twenty years of the team���s existence, they simultaneously represented national and pan-Africanist interests. They boycotted the 1966 FIFA World Cup in a protest against racist discrimination and united much of Africa and the diasporas in support of them. They won the African Cup of Nations in 1963, 1965, and 1978 and were runners-up in 1969 and 1970. Even when they weren���t winning, their fans were always full of hope and devotion. They were The Black Stars, whether they won or lost, and they would always be back to win again.

But it���s 2019 now, and the last time the Black Stars won a tournament was thirty-seven years ago. Popular support for the team is waning, but people continue to support the Black Stars above all other national football and sports teams. That it is the men���s national football team that occupies this prime position is no coincidence given the dominance of patriarchal ideas in Ghanaian society. State resources, private sponsorship and popular support have also been concentrated in the team to the detriment of women���s football and other sports.

The current mix of emotional attachment and cynicism that Ghanaians currently feel for the Black Stars is perhaps best understood as a form of wary nostalgia. It is a longing for a time when the Black Stars carried the hopes of a nation and a continent, and when there was widespread optimism about the country���s future.

In a troski from Madina to Tema, the radio blares scratchily with static. There���s a sports program on, and the presenter is bitterly complaining about the poor management and ���dirty politics��� in Ghana football. After a 3-minute tirade he pauses, sighs and says ���anyway they���re our Black Stars, we have to support them������ That idea���of having to support the Black Stars���shows how deeply Ghanaians still believe in the idea of Ghana despite decades of disappointment, underachievement and betrayal.

Does the deal in Sudan represent an actual democratic transition?

Image credit Duncan via Flickr (CC).

On July 5, Sudan���s military leaders and opposition coalition reached a long awaited compromise to share power until national elections can be held. Both sides agreed to establish an autonomous council with a rotating military and civilian presidency for a period of three years. The two sides also agreed to launch an independent inquiry into the violence that ensued in the weeks leading up to the deal. Yet this deal far from guarantees Sudan���s democratic transition.

While the natural requirement for revolution (mass dissatisfaction with the government in charge) is commonplace, successful democratic transition is rare. Not every outburst of collective discontent or joint act of defiance leads to a successful revolution. Underlying factors such as youth unemployment and widening inequality, while common to most of the Middle East and North Africa, do not always translate into popular uprisings. The disparity between cause and consequence is grounded in the strength of the state, more specifically the state���s ability to maintain a monopoly on the means of coercion. If the state���s oppressive structure is sufficiently well organized and effective, it can resist popular disaffection and crush democratic reform initiatives from below.

Such was the case in Egypt in 2011, which saw President Hosni Mubarak step down to widespread celebrations but then was co-opted by the military. The protest movement which ousted President Omar al-Bashir has some parallels to this revolution. In both instances, various groups used their grievances regarding a number of domestic conditions to call on their respective governments to bring about democratic reform. In addition, as in Egypt, the military played a significant role. Military generals in Sudan assumed power after removing a dictator from government in order to place themselves in the driving seat of a transitionary government. These similarities are concerning given the outcome in Egypt. After the removal of Mubarak, a poorly constructed transition to democracy fragmented revolutionary groups and led to a coup in 2013 when the military re-assumed power.

One factor which proved vital to securing a transitionary deal in Sudan was the importance of a unified revolutionary force. One reason for Egypt���s failure to democratize was the various disagreements between the secular and Islamist branches of the revolution regarding the terms of transition. Both of these groups mistakenly subordinated the common goal of establishing democracy in favor of advancing their own political ideas and interests. The revolutionary coalition in Sudan will have to maintain their focus and organization in the coming months in order to secure their common goal of bringing a democratic, accountable and civilian-led government into power. While the revolution is still young, at first glance it appears as if the diverse protest groups in Sudan have learnt important lessons from Egypt���s failed democratic project.

Where revolutions have succeeded in the region and other parts of the world, protest movements have transcended ethnicity, religion and socio-economic class by rallying around a common set of goals. It is worthwhile analyzing Sudan���s history of popular protest in order to appreciate the challenges facing the current movement. From the October Revolution in 1964 to protests during the 1980s, the main challenge that determined the outcome of past movements was that of nationality. In other words, one of the chief obstacles has been reconciling and organizing a country consisting of various different cultures and ethnicities. The inability to form an inclusive national identity has been a source of troubled relations between Sudan���s urban and rural revolutionary forces. Therefore, the extent to which protest organizers are able to address this ongoing challenge by fostering associations between urban and rural constituencies is key to the success of the current movement. For example, former President Bashir attempted to blame students form Darfur for the protests, by alleging that they had set fire to an office of the ruling party. However, the usual strategy of divide and conquer failed miserably as protestors refused to give in to the regime���s attempt to sow division and fear on the basis of difference. Rather, the Sudanese people became more united by transforming Bashir���s racist ruse into a rallying cry against him, with protestors chanting, ���We are all Darfur!���

Still, protestors on the ground will be the first to admit that democratic revolution in Sudan has not yet emerged. While the uprising has been successful in deposing the Bashir regime from office, it has yet to overturn the predominant value systems and behaviors which entrenched authoritarianism in the first place���something that will take years. The revolution may better be described as a minimal revolution as it has achieved the first demand of the Sudanese people namely, the removal of the old regime. The completion of the revolution would entail the transformation of political structures and norms so as to enable society to assume its rightful place as the driver of human development.

To secure democracy in Sudan, regional stakeholders and revolutionaries must prioritize the construction of effective bureaucracies, impartial state institutions and an inclusive national identity which can transcend ethnic rivalries and unite people around a common set of goals. In the absence of the above mentioned conditions, eliminating the state���s oppressive structure will create a political vacuum, which will be more susceptible to the revival of authoritarianism rather than the success of democracy. Hence, there is a need to distinguish between the process of eliminating authoritarianism and establishing democracy.

It is also crucial that transitional groups resist the intrusions of regional states, such as the UAE, who have a vested interest in preventing the establishment of viable democracies in the region. For instance, Sudanese protestors have previously taken to the streets to oppose Emirati aid packages thereby denouncing unwarranted foreign intervention in the transition process.

At present, there are two main possibilities for Sudan. The first is a successful transition from authoritarianism to a sustainable democracy. However, as outlined above, democratization requires a process of consolidation whereby various actors must be made to conform to newly established democratic rules and norms. The second possibility is that the transition towards democracy will be hijacked by an authoritarian regime which assumes power once the post-revolution honeymoon period finishes. From this perspective, the events in Sudan are seen as a brief interval before the inevitable return of authoritarianism. While the transitionary agreement in Sudan represents a step in the right direction on the journey towards democracy, only time will tell whether the power of the people is truly greater than the people in power.

That being said, the events which are unfolding in Sudan are complex. It is therefore crucial that, African students in particular invest the necessary time and effort to understand these developments. The desire to understand the struggles of the continent must be channelled into a force which helps, wherever and whenever possible, to change Africa for the better. Students ought to take courage from the initiative shown by the youth in Sudan, who through their perseverance have advanced the cause of democracy. Contemporary events in North Africa have confirmed the idea that courageous African students remain the most progressive force for positive change. In Sudan, it was students who showed initiative by being the first to take to the streets, thereby transforming a mainly student-led rebellion into a national uprising. From Cape Town to Khartoum, students must see themselves as part of an African youth who are determined to reshape the continent���s reality.

Making sense of regional integration in Africa

Following the tracks from the Zimbabwe border to Zambia at sunset. Image credit Youngrobv via Flickr (CC).

A highly anticipated coordination meeting between the African Union (AU) and the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) will take place in Niamey on July 08, 2019. The Summit is one concrete measure of the latest round of institutional reforms of the AU, initiated by its previous chairperson President Kagame. Discussions will be centered on the subsidiarity principle: what level and organization is best placed to deal with regional policy making, problem-solving or norm-setting? But is this enough to ensure coordination given the multitude of other (and overlapping) regional organizations in Africa? Strengthening African regionalism may be less a matter of engaging the RECs, and more about solving specific regional problems, where the RECs are but one of a set of regional actors.

Constructing a continent

The Niamey Summit will see discussions between the AU and eight officially recognized RECs. These are the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and Southern African Development Community (SADC). There are six other RECs, and several other regional bodies. These serve as the building blocks towards the African Economic Community. Although some are more effective than others���the AMU and CEN-SAD have been somewhat dormant in recent years���in July 2006, the AU decided to stick to these eight with a moratorium on recognizing any more RECs.

But a plethora of regional bodies and agencies exists beyond these RECs, carrying out functions that overlap and often cut across them. SADC, ECOWAS and ECCAS all contain a smaller but more historically rooted sub-region in the form of SACU, UEMOA and CEMAC, respectively. These are the Southern African Customs Union, l’Union ��conomique et Mon��taire Ouest Africaine, and Commission ��conomique et Mon��taire de l���Afrique Centrale respectively.

Plus there are a range of river basin organizations, sub-regional organizations and partnerships as well as regional peace and security arrangements. As a result, the average African country belongs to no less than eight different regional bodies. The DRC is member of at least 14 different regional entities���15 if their request to join the EAC is accepted. This has resulted in the (in)famous metaphor of an African ���spaghetti bowl��� of regional institutions, often with limited organizational capabilities and weak supranational authority.

To some, such as the EU, this suggests a need�� for rationalization of regional memberships.��Rather it may reflect a real need for multiple regional platforms to address the cross-border and regional challenges African countries face. For those countries, joining different regional fora is a rational decision���with a relatively limited cost given the reliance of most regional organizations on external finance���even if the rationale is not always clear to outsiders. That raises a challenge to the relatively limited scope of the AU summit.

Member states are the ultimate drivers of regional integration and cooperation. A shift in focus towards regional politics and their relation to national interests can shed light on why there are so many regional bodies, and why some work better than others.

History and politics matter

Regional cooperation and integration is an outcome of historical path dependencies, negotiation, bargaining and power games between and within states and between states and different regional organizations. Discussions about rationalization to avoid the overlap in membership and duplication of efforts often ignore why countries set up regional organizations in the first place. For instance, while members of UEMOA are also in ECOWAS, the two groupings have very different origins and levels of integration. ECOWAS is a customs union with both anglophone and francophone countries, while UEMOA is a monetary union of the West African francophone states. Consequently, the internal power balance and member state allegiances vary a lot. Nigeria dominates ECOWAS, accounting for 70% of its economy, giving it great ability to influence regional dynamics by promoting or blocking the bloc���s efforts. On the other hand, UEMOA states tend to speak with one voice in ECOWAS negotiations. While it aims for a full economic community with a common currency, ECOWAS has no mechanisms to ensure the primacy of its policies over those of UEMOA, often leading to tensions.

While they have inter-institutional meetings to improve convergence, UEMOA countries would have little to gain were the group subsumed into ECOWAS. C��te d���Ivoire for example would simply become a small fish in a bigger pond. Moreover, a common currency based on Nigeria���s oil-driven economy would mean importing petro-volatility, a 180 degree turn from the Euro-bound stability of the CFA franc. At the same time, it is also recognized that UEMOA needs ECOWAS for further economic integration, and this cannot be done without or against Nigeria. ECOWAS has also made progress on the security front as well as nudging its members towards a democratic path. Hesitant positions within UEMOA are thus more a reflection of their balancing act between competing choices.

Relevance of functional organisations

Although countries are members of multiple regional organizations, there are often frustrations with how these actually function, due to slow implementation or ineffectiveness. Political traction at the regional level is, to a large extent, determined by national interests. Moreover, the role of regional hegemons or swing states such as Nigeria, South Africa and Ethiopia can also be important in solving (or perpetuating) regional problems. While RECs tend to have comprehensive mandates including areas such as agriculture, industrial policy, trade facilitation, peace and security and so on, this does not automatically imply leadership, or major influence over decisions by member states in these areas. In many regions, cooperation has made more progress in some areas, notably conflict prevention and resource management, partly out of a sense of urgency, than in others such as trade, where there are lots of agreements but implementation is trickier.

Member states work with, or through, organizations that best represent their interests (however those might be defined). This includes (sub)regional bodies that fall outside the purview of the eight RECs or the other regional economic groups. For instance, transboundary water governance is exercised through river basin organizations. These are intergovernmental bodies with the single purpose of managing freshwater resources between countries that are part of a watershed. West Africa is home to several of these functional organizations. Among these is the OMVS (Organisation pour la mise en valeur du Fleuve S��n��gal) which has joint ownership of key hydrological infrastructure with equitable distribution of costs and benefits and is by many considered a model for the management of transboundary resources. The wider REC (ECOWAS) has less influence over national positions on water and energy even if it has a regional water policy.

There is also the Lake Chad Basin Commission. While ostensibly created for joint management of water resources, it hosts the Multinational Joint Task Force, a joint military effort to combat the threat of terrorism posed by Boko Haram under the leadership of Nigeria. With member states split between ECOWAS and ECCAS, the Commission presents a useful cross-REC platform to discuss the issues of porous borders and security threats. Though outside the official framework of the eight RECs that are the preferred implementing agents of the African Union Peace and Security Architecture, this platform aims to address a specific regional problem or need.

Way forward?

Given the complex dynamics at play, it is important to accept the political economy���actors, interests and incentives���of regional integration, and the processes that shape national priorities, bargaining power and implementation. Pragmatism and improvised institutional arrangements may at times provide better solutions to regional problems than a normative position of what regional integration “ought to be,” i.e. an understandable form of subsidiarity, by working through the RECs in coordination with the AU.

It would be important to integrate broader regional dynamics into the discussions. Thematically focused continental meetings and regional learning may prove a more effective way to dig into the spaghetti bowl.

July 6, 2019

Is the world ready to support a Green New Deal for Africa?

Vanderbijl Park, South Africa. Image: World Bank.

When US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez introduced her now-famous Green New Deal resolution to the press, she called climate change ���one of the biggest existential threats to our way of life, not just as a nation but as a world.��� To combat the threat, she said, ���we must be as ambitious and innovative in our solution as possible.���

The Green New Deal is surely the United States��� most ambitious vision for climate justice to date. But the crisis, as Ocasio-Cortez knows, is a global one. Tackling it equitably, therefore, requires a worldwide effort that accounts for the unique challenges developing nations���particularly those in Africa, the continent considered most vulnerable to global heating���face in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change. Ocasio-Cortez���s 14-page Green New Deal resolution, however, includes just one sentence concerning the United States��� obligations to the rest of the world. Other Green New Deal proposals that have recently emerged in European countries such as Spain are also largely focused within their own borders.

A Green New Deal, by definition, emphasizes climate justice, which means that domestic decarbonization plans within that framework may be less likely than others to produce damage in other countries. Still, African countries have good reason to be wary of potentially myopic Western climate agendas. In an article for The Conversation this February, Ol��f�����mi O. T����w��, a Nigerian professor of philosophy at Georgetown University, raised the concern that such plans could exacerbate ���climate colonialism��� by exploiting poorer nations��� resources. In Uganda, Mozambique, and Tanzania, for instance, thousands of people have been forcibly evicted from land purchased by a Norwegian company implementing forestry-based carbon offset projects. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, meanwhile, is struggling to manage the surge in demand for cobalt, a key component in the production of electric vehicles and renewable-energy batteries. The DRC has half of the world���s cobalt reserves, and about 20 percent of it is mined by children in dangerous, unregulated mines that the government has proved unable to close.

Previous global climate plans have mostly ignored the needs of the world���s vulnerable people, and that���s particularly true when it comes to climate finance. At COP24, the 2018 version of the United Nations Climate Change Conference, the chair of the Least Developed Countries Group���a body representing 48 nations that are especially vulnerable to climate change but have done the least to cause the problem���told the leaders of developed nations that merely making their own domestic climate plans more ambitious won���t be enough to address the global crisis. Gebru Jember Endalew, from Ethiopia, said for developing nations, ���trillions of dollars in climate finance (are) needed to cover the costs of adapting to climate change impacts, coping with loss and damage, and pursuing clean development pathways to avoid emissions.���

The Green Climate Fund, which was created at COP16 in 2010, exists to manage those kinds of investments, but it���s being grossly neglected. Initially, developed countries agreed to contribute $100 billion to the fund annually by 2020. To date, however, only $10.3 billion has been pledged and only $3.5 billion has actually been committed. African countries, meanwhile, are ���on a perpetual treadmill of paperwork��� as they struggle to access what limited funds are earmarked for them.

Recent proposals for a planet-wide Green New Deal seek to make climate finance a powerful instrument of climate justice. Yanis Varoufakis and David Adler of the Democracy in Europe Movement have proposed an International Green New Deal that would raise $8 trillion annually for renewable energy investment and climate protections ���on the basis of countries��� needs, rather than their means.��� People���s Policy Project, a socialist think tank, has a plan for a Global Green New Deal, which calls on the United States to transfer $680 billion a year to the Green Climate Fund, and for other OECD nations to contribute their fair share. Such proposals don���t just make sense morally; they also make sense scientifically. Greenhouse gas emissions are rising precipitously in developing countries. To avoid a planetary catastrophe, developed nations must give developing nations the technical and financial support they need to transition to low carbon economies.

Are Africans clamoring for such a transition? Not exactly. A recent Bloomberg look at global polls revealed that among voters in three African nations���Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa���climate concerns are far outweighed by everyday anxieties about employment and security. In an article for the the South African Mail & Guardian, for example, the University of Cape Town���s Co-Pierre Georg argued that South Africa needs to first improve education, create jobs, and strengthen the agricultural sector before it can worry about the planet. What such arguments miss is that the line between economic development and climate adaptation in Africa is a blurry one, and it will only get blurrier as the planet gets hotter.

The American Green New Deal, after a resounding defeat in the Senate in March, remains a gleam in Ocasio-Cortez���s eye. International proposals that share its emphasis on climate justice are even further from political reality. For African leaders who are concerned about the climate crisis, that could be seen as greatly discouraging. But it could also be greatly hopeful, as it means that there���s still time to push the international community toward a truly ���ambitious and innovative��� climate plan���one that works not just for Western nations, but for the entire world.

July 5, 2019

Democracy and the left in post-apartheid South Africa

Ben Turok. Screen grab from Ian Landsberg Youtube.

Professor Ben Turok, now 92 years old, was an African National Congress (ANC) Member of Parliament in South Africa for 20 years. Turok is the sole surviving member of the original underground leadership of the South African Communist Party, which he joined in the late 1950s and from which he was expelled in 1976, while in exile, after a dispute over dispersing funds to a trade unionist in South Africa. He was an accused in the 1956 Treason Trial (156 opposition figures were arrested, tried and eventually acquitted four years later), served 3 years in prison (he was convicted under the Explosives Act in 1962) and was in exile for 25 years.

In exile, Turok taught political economy at universities across Africa and at the Open University in the UK. During this time, he also established the Institute for African Alternatives (IFAA) as a vehicle to oppose the structural adjustment programs of the IMF and the World Bank, choosing to rather promote African self-reliance. Turok returned to South Africa in 1990 during the transition to democracy.

In the post-1994 democratic government, he was first head of the Commission on the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) in the Gauteng Provincial Cabinet and then moved to the National Assembly in 1995. He was the Co-Chair of the Committee on Ethics and Member���s Interests of both Houses in Parliament. Since leaving parliament, he has been a vocal critic of corruption and governance problems in the ANC since Jacob Zuma���s presidency. He is the editor of the journal New Agenda published by IFAA, of which he is now the Director.

Carilee Osborne

South Africa has just gone through its 6th democratic election. What are your overall impressions of how that has played itself out?

Ben Turok

Well I was, on the whole, quite pleased that the ANC managed to maintain a substantial vote. [The ANC has had the largest share of MPs in the national assembly since all South Africans first voted in 1994 when it got to appoint 252 of the 400 MPs in the national assembly. Its high point was in 2004, when the party seated 279 MPs. In the 2019, the ANC could only secure 230 seats���Ed.] Of course, there was a substantial abstention. That is something we all expected���there is no doubt that there is a lot of disenchantment with the ANC. However, people still appear to have loyalty to the ANC. I am talking about the masses. I am not so concerned with marginal groups and when they rise or don���t rise. A great deal of attention has been given to the Freedom Front Plus for example. [The Freedom Front Plus, a small party which appeals primarily to Afrikaans speaking whites, increased its number of MPs from 4 seats in 2014 to 10 seats in 2019 elections���Ed.] I think those are marginal issues. The main issue is what do the mass of our people think���and they voted for the ANC despite all the issues. The ANC does still speak to the people.

Carilee Osborne

A lot has been made in the media about the growth of the EFF and the fact that they will now hold 44 seats in parliament, up from 25 seats when they first contested national elections in 2014. What do you make of their performance?

Ben Turok

Well, they are a very dynamic group and they are actually very visible and very good politicians in a way. However, they are clearly populists without a real program. We don���t really know what they stand for. Like all populist parties all over the world, they sloganize a great deal and articulate what they think are popular policies which attract young people and the masses and they succeeded in doing that. And, frankly, the ANC has been rather flat-footed���it is a tired organization and many people have been there a long time and have lost energy. People can sense that. The EFF is young and dynamic. They wear their berets and have all the paraphernalia, and so I think they are targeting and triggering a sort of gut reaction among young people. This is very dangerous because the EFF are irresponsible and they don���t articulate a serious policy. For instance, now���absolutely surprisingly���they support the public protector (South Africa���s version of the attorney general). Everyone else is against the public protector who is obviously incompetent and is breaking the law with every judgment she makes, but the EFF stands behind her because she is prosecuting Pravin Gordhan. [Gordhan, the current minister of public enterprises and former minister of finance, is a key ally of current President Cyril Ramaphosa and is widely considered to have been a bulwark against corruption efforts by former president Jacob Zuma and his allies, making him a target for the latter group. He has also been targeted by the EFF for allegedly instructing officials at the South African Revenue Services (SARS) to investigate EFF leader Julius Malema. The EFF claims that Gordhan is himself guilty of acting unconstitutionally.]

That is how the EFF works. They work on current affairs, on immediate issues, on populism. Also, one has to say that there is a strong suspicion of corruption with the VBS Bank scandal in particular. [VBS was a mutual bank primarily serving lower-income communities which, upon being placed under curatorship in early 2018, was found to have undergone widespread looting and corruption by various government and political party officials]. The EFF are denying everything of course but the connections look very suspicious. They are doing what the ANC did but with less credible organizations. Of course, the ANC gets money through these kinds of networks. The ANC has gotten a lot of money from people trying to curry favor with them. The case of the mayor in Durban right now is indicative of this. Form my personal knowledge it appears that she has been running something of a parallel state and that is corrupt to the benefit of the ANC. The tenders are designed to benefit the ANC. When you have this, the word gets out and you lose a lot of credibility.

Carilee Osborne

I���d like us to talk, as we move forward from elections, about parliament which often doesn���t get the attention it should. You spent 20 years as an MP. What are your overall thoughts about that time?

Ben Turok

I have been brooding on this a lot lately. It is a very mixed experience. On the one hand you feel very honored to be in the South African democratic parliament and it gives you a very nice feeling, especially in the days of Mandela and even Mbeki. One shouldn���t underplay that���the pride in one���s country and in the ruling party at the time. Of course, things went rather differently under Zuma when one became rather disgusted being part of a machine, which was really not taking any action against a corrupt president. I must say that we didn���t know just how corrupt he was. I am interested to see that even a person like Dennis Davis, in his recent book Lawfare, admits that he���as a judge and as a professor���was not really aware of the scale of corruption under Zuma. Zuma was very clever and careful in many ways. Although we knew something was wrong, we couldn���t always identify where and how. You knew some appointments were bad���Brian Molefe [former CEO of ESKOM, the state-owned electricity corporation], for example���but you couldn���t always say why it was wrong.

To get back to your question, as an MP you have access to an enormous amount of information. You get the budget, you get the annual reports of all the departments, the Auditor General reports. If you have time to read, you have an enormous amount of material. It is a matter of time and of diligence. So, you are sitting in the middle of a vortex of paper and you can often only skim these documents. And you have a lot of responsibilities and obligations within a highly bureaucratized system.

Let���s start with the ANC caucus where you meet every week at a set time chaired by the chair of caucus with the chief whip. Here you run through the legislation that is coming and Ministers will report on their legislation. They will often present you with supporting documents that aren���t public. So you really get an inside picture of why the ANC is taking certain positions on certain issues. Of course, you also get the President [of the country] or the [ANC] Secretary-General addressing caucus and laying down the political line. It is made very clear to you that you are there at the bequest of Luthuli House [the name of ANC headquarters]. It is made very clear that you can think what you like personally but, in parliament, you are there as the party and there is a line and that creates many problems. I think back to the time of AIDS denialism and the many people in caucus who had reservations about [then-President Thabo] Mbeki���s position. What these people did is went to the chief whip and said that they couldn���t support this. What the chief whip would say is that they could ���play sick��� that day. But, by and large, there is a line and this is what you obey. Similarly, in your ANC study groups, you will discuss a piece of legislation as an in-house group, as the ANC.

Carilee Osborne

Could you tell me about the work of the committees? How important are they?

Ben Turok

The multi-party portfolio committees are really where the work happens. On the whole they are very co-operative. You get tensions and some disagreements but it is not difficult to get an agreement. The parties will usually compromise in the end. From there, the decisions are drawn up by the officials and sent through the Speaker and a debate is arranged, the legislation tabled etcetera. The curious thing I always say is that some very helpful opposition people in the portfolio committee will come into plenary and be your biggest enemy. There is often real confrontation because the cameras are on so people are playing to the TV. This is very different to the working group in the portfolio committee and it creates a lot of problems.

Carilee Osborne

There has been a great deal of controversy recently about the role of the Reserve Bank [how South Africa���s central bank is known]. This is something that you worked on when in the finance committee. Could you tell me a bit about that?

Ben Turok

Around 2005���I can���t remember exactly���the finance committee appointed a multi-party committee, which I chaired, on the role of the Reserve Bank. We travelled to Chile, Mexico, Sweden and I had personal interviews with the Governor of the Bank of England who helped me a great deal. We drafted a report and that report dealt with all the issues which are under discussion at the moment about the role of the Reserve Bank: about its quasi-independence, the question of inflation targeting and all that. It is all dealt with in that report. I find it just amazing that the decisions that we took then, which we concluded on a multi-party basis, and which were approved by parliament have now raised their head again with little reference to this process.

Another thing I worked on [earlier] in Parliament was the finalizing of the Constitution [passed in 1998]. I was put on a committee on the Bill of Rights. When I saw a draft, I was perturbed that there was no socio-economic clause. I had been working in Geneva at the United Nations on the UN Convention on Socio-Economic Rights, so I knew it backwards. I went to see Fink Haysom, who was Madiba���s lawyer in parliament, and explained this to him. He asked for some documents. I gave him the UN convention and various other documents. He called me two days later and said I was right and that we needed to include socio-economic clauses. I was over the moon as you can imagine. I left it to him because he was drafting. However, what he did was to also include the limitation clauses. These limit the application of a socio-economic right to available resources. This has been used over the years to justify not implementing socio-economic rights. The minister of finance has repeatedly used the limitation clause to justify not carrying out those rights. As it happens, in Lawfare, they deal with the clause. Actually, it is quite limited and cannot be used freely to deny socio-economic rights. I think this remains a problem and I want to put this on record.

Carilee Osborne

There was also a lot of controversy around your role in Parliament���s Ethics Committee. Could you tell me about that experience?

Ben Turok

I was very fortunate to chair the ethics committee. However, when I was first appointed, I thought, ���Oh my god, this is some sort of backwater.��� In fact, Gwede Mantashe [then ANC Deputy Secretary-General] and Kgalema Motlanthe [then-ANC Secretary-General] called me to Joburg and said they wanted me to me head of the ethics committee and I wasn���t happy because of that. I thought it was a backwater. But that is what they had for me and so I agreed. At the first meeting of the committee, I asked what the agenda was, and I was told that our job was to monitor the financial interests of members. Members fill in a form, officials compile a report from the forms and if there are any questions, they call in the member for questioning. And I felt this was a very unsatisfactory approach, so I phoned Frene Ginwala, the former speaker [from 1994 to 2004]. And I asked her, ���When you adopted the constitution and set out parliament���s role, did you have a philosophical position?��� And she said, no.

I felt that you couldn���t have an ethics committee without a political philosophy. This is not just box ticking where you say, ���I received this and I didn���t receive that.��� It is about the integrity of an individual. I phoned the UK House of Commons and I asked them what their philosophical underpinnings were, and they sent me a couple of documents. But I have to say I wasn���t impressed. So, I wrote a paper for the committee. My co-chair thought I was crazy, but I didn���t want to be there if we didn���t have an understanding of the foundations of what we wanted to do. Case law is not enough. We have to interpret the rules. This requires ethical judgement. You can���t just depend on precedent. My paper was then adopted and thank goodness because, thereafter, we began to exercise ethical judgements and became a lot more sophisticated.

It was soon after, for example, that we began to investigate Dina Pule [Minister of Communications from 2011 to 2013]. I don���t know if you remember the story of the red shoes? Well here is a minister who goes to Europe [in 2012] and gets herself a pair of extremely expensive shoes and the Sunday Times prints this on the front page. [The Sunday Times reported that her boyfriend, not Pule, had used sponsorship money for a government run IT conference in Cape Town to buy her expensive shoes.] Immediately my hackles were raised. I thought this was out of order and we needed to investigate. We found that she was involved in corrupt practices with certain companies. She was organizing a big [conference] in Cape Town and a lot of money had been allocated to that. There was a genuine exhibition company that had been marginalized for a number of reasons, that had lost a huge amount of money because the money was going somewhere else. When we enquired about where it was going, a boyfriend of Dina Pule emerged and the plot began to thicken. I contacted the police. We got hold of the public servants in her department and we subpoenaed them to tell us how the contracts were drawn up. We went into great detail and had to piece together many small bits of evidence that we felt was very compelling.

The parliamentary code of conduct makes provision for a parliamentary court of sorts. The ethics committee appoints nine members to set up a court. I chaired that. We summoned Dina Pule. She was very angry, very resentful that she was a minister and had been summoned here to us.

In this process you are allowed to be defended by another member of parliament, preferably a lawyer. Mike Masutha was her lawyer, the later minister of justice. I was furious with him. I felt he had conducted a Stalingrad defense. It was a tricky exercise but we finally found her guilty. I went to the chief whip with the evidence. The rules require that we now report to the House as the committee had no powers of its own. We couldn���t dismiss anybody because the House has to make that decision. She was a member of the House and he said no. So, I had a fight with him. He said that the order paper was too full and it was the end of term etcetera. I emphasized to him that this was critical and that we had been working very hard on this.

By the way during, this I was summoned by the political committee of the ANC, chaired by Kgalema Motlanthe which consisted of him, ministers, the chief whip, among others. I had to explain what this was all about and the procedures we had followed, and they said go ahead. Then I was summoned by the ANC whips. It was a very controversial and heated moment. They said, ���Why are you attacking an African woman?��� It was a very stormy meeting. They didn���t say ���white man��� and all that, but it was there. I was facing the music. They had a go at me. I had to explain that the code of conduct dictated this. Finally, they let it pass.

After a lot of maneuvering, I got it on the order paper and I presented a speech to the house. I said she was guilty of an offense and the House must take the necessary steps. She was there. As she left the chamber, a whole lot of women hugged her and kissed her and really made me feel as if I was the enemy. So, she had a lot of support. People didn���t like this, but we stood our ground and ultimately she was sanctioned.