Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 214

July 2, 2019

Tuning surveillance software with African faces

Presidents Zuma, Xi Jinping and Mugabe. Image credit Kopano Tlape for Government of South Africa via Flickr (CC).

With growing technological advances, more countries are being propelled to implement data privacy and protection measures. But such laws may not offer comfort in countries like Ethiopia and Zimbabwe, where there is little institutional will and capacity to protect privacy and means to enforce the rule of law.

Current research explores how data privacy legislation across the globe is rising in popularity; however, hardly anyone discusses the inadequacy of legal instruments. Though the problem of ensuring privacy of personal data is greater than simply whether data privacy laws exist, the capacity to enforce and protect those rights is crucial in the quest for human rights and dignity.

Meanwhile a techno-dystopian future is an encroaching possibility, where internet controls and surveillance technology reach unregulated extremes. The 2011 internment of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, a province in northwest China, foreshadows the impact of facial recognition technology and other apparatuses which facilitate surveillance programs that track everything about everyone at all times.

Western mainstream media has explored the vastly expanding domestic surveillance architecture in China, but has mostly ignored its growing global footprint in Africa. African states, including Zimbabwe, Kenya, and Zambia, with the support of the Chinese state, are following the Chinese Communist Party���s (CCP) efforts to unbridled data collection, which is threatening traditional conceptions of privacy. For instance, the Zimbabwean government, with the help of ClouldWalk Technology, a Guangzhou-based start-up, is providing mass facial recognition programs. The agreement between the government and CloudWalk is part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a comprehensive plan to promote infrastructure development across Africa, Asia, and Europe with Chinese financial aid. These programs capture personal data to engender one of the world���s most sophisticated and racially diversified facial recognition databases.

Zimbabwe���s control of online and offline spaces is largely based on Japanese and Chinese support. Admittedly, the Zimbabwean ministry of communication has maintained that the technologies garnered from foreign suppliers are used for digital forensics and facial recognition systems. These systems, and accrued data, empower the state to control communication devices for crime prevention, and ultimately advance the state���s cybersecurity and law enforcement aims.

Worry accompanies these advances. Firstly, Zimbabwe may be giving away citizens��� private data to an unaccountable Chinese tech firm. Secondly, activists, technology experts and academics underscore how these tools may help Zimbabwe���s government crackdown on political dissidents. Relatedly, trepidations extend to places like Ethiopia where this wave of imported surveillance technology has also aided in targeting independent voices.

Ethiopia���s hybridized surveillance apparatus reveals the state���s capacity to do patchwork with diversely sourced technology. The government has acquired monitoring tools through commercially available spyware. Namely, the UK and German-based Gamma International FinFishers, Cyberbit an Israel-based cybersecurity company, and the Italian based Hacking Team���s Remote-Control System. These apparatuses extend Ethiopia���s surveillance capacities, and effectively enable access to files on targeted laptops. They also log keystrokes and passwords as a way to turn on webcams and microphones as a means to make them spy gadgets. These tools run on Chinese funded Information and Communications Technology (ICT) systems. Such trends present a challenge to the future of privacy and the prospect of democratic politics in Ethiopia���and beyond.

Ethiopia, as a nation seeking development, is instructive for its novel approaches to ICT systems and its collaboration with the Chinese state. Ethiopia is notorious for its low levels of internet penetration. Yet, with the help of China, it has charted new avenues of ICT development and changed the country���s modes of governance. That is to say, it has championed the use of ICT mechanisms as instruments of development. These apparatuses have empowered development, but also the means, like Zimbabwe, to bolster suppressive practices. In other words, Chinese support has enabled the Ethiopian government to increase internet access while maintaining Addis Ababa���s callousness towards freedom of information.

For Ethiopia, and other African states, the purchase of spyware and the implementation of ICTs, with foreign support, raises pointed concerns. Regardless of whether China is thought to be an active teacher that purposefully exports its anti-democratic developmental strategies, Ethiopia���s weak rule of law, poor record of internet freedom, and limited independent oversight over government programs means that technologies are likely to be abused. A techno-dystopian future is more likely if African governments and publics continue to overlook the current crisis. Digital authoritarianism, in Africa and beyond, is on the rise. Securing data privacy and internet freedom against these novel forms of repression is fundamental to preserving our rights and fragile experiments in democracy.

July 1, 2019

Nostalgia for empire

Ajit Chambers and Boris Johnson. Image credit Annie Mole via Flickr (CC).

With his penchant for colonial nostalgia, the prospect of Boris Johnson as Prime Minister of Great Britain does not bode well for the development of a society which would recognize its history of imperial brutality. Instead, the rise of Boris Johnson would ensure the continuance of the prevailing understanding of the British empire as “something to be proud of.”

Some lowlights.

In 2002, Johnson wrote for the right-wing Telegraph newspaper that former UK Prime Minister, Tony Blair���s visit to the Democratic Republic of Congo would mean that ���the pangas will stop their hacking of human flesh, and the tribal warriors will all break out in watermelon smiles.��� The fact that the man who wrote these words later became Foreign Secretary for Britain is astounding.

Also in 2002, Johnson stated that Africa ���may be a blot, but it is not a blot upon our conscience.��� He argued that ���The problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge any more.���

In 2016, Johnson waded into a confrontation with then-President of the United States, Barack Obama, when he stated that the removal of a bust of Winston Churchill from the Oval Office was perceived by some as ���an ancestral dislike of the British Empire.��� This dislike, Johnson argued stemmed from Obama���s ���part-Kenyan ancestry.����� (Obama had replaced Churchill with one of Martin Luther King Jr., ���to remind him of the people who helped get him there.������Ed.)

Though Johnson didn���t say more, he was alluding to Obama���s paternal grandfather, Hussain Onyango Obama.��The old man ���had served with the British army in Burma during the second World War and later found work back in��Kenya��as a military cook.��� As the UK Times revealed in 2008:

Like many army veterans, he returned to Africa hoping to win greater freedoms. But his aspirations soon turned to resentment of the occupying British. He became involved in the��Mau Mau��independence movement and was arrested as early as 1949, probably on charges of membership of a banned organization. During two years��� detention he was subjected to horrific violence, according to the story’s authors, Ben Macintyre and Paul Orengoh. Tortures inflicted on Kenyan prisoners sometimes involved such barbaric implements as “castration pliers.”

In 2011, a group of former Kenyan freedom fighters, then in their 70s and 80s took the British government to court in London over torture within the detention camps set up during the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya from 1952-1960. The rebellion has remained a controversial topic and a traumatic segment of both British and Kenyan history. The system of detention camps housed the accused Mau Mau warriors and supporters, who mostly consisted of the Kikuyu people.

These camps were built under the fa��ade of rehabilitation���in reality, they were punitive institutions, which detained 80,000 Black Kenyans. The camps allowed brutal interrogations, which often consisted of torture and in some cases, murder. Some accounts of the barbarous actions taken by camp officials can be found in the British National Archives, though many were destroyed upon the eve of Kenyan independence.��These acts of torture were carried out all in the name of maintaining British colonial sovereignty.

The memory of the Mau Mau rebellion in British history has been overshadowed by the official account of the rebellion provided by the British government. As a result, for decades the former detainees of these camps have gone without apology or recognition for their suffering.

However, with the advent of the 2011 Mau Mau court cases, it seemed that the former detainees may finally receive some form of justice. During this case, the Foreign Commonwealth Office (FCO) were brought to court by ex-detainees and tried for their crimes���since then, many more cases concerning over 40,000 Kenyans have followed.

However, the Mau Mau court cases resulted in the Hanslope Park Scandal. Where the Foreign Commonwealth Office (FCO) were revealed to have been secretly withholding thousands of documents from the colonial era, under the guise that government officials did not know that they existed.

When the court case began, the FCO tried to cast off responsibility. They stated that the responsibility for these grievances had been passed on to the Kenyan government upon independence. The FCO also argued that the case could not go to trial due to a lack of evidence. Once the court case had begun, the FCO were asked if they were withholding any documents in relation to the case, to which they originally answered, no.

After pressure from the court and historians, the FCO were forced to admit that they were secretly holding 1,500 colonial documents at the Hanslope Park location.��It was later disclosed that this government location held a further 20,000 undisclosed files from 37 former colonies.

The existence of the hidden documents at Hanslope Park can provide insight into how public history in the UK has been influenced by the government���s attempts to disseminate its preferred narrative of empire.

The court case resulted in the British government providing monetary compensation to 5,200 Kenyans. They also decided to pay for the erection of a memorial in Nairobi which was completed in 2015. Accordingly, it seemed that the British government may have finally begun to face to consequences of colonial rule. However, it is unlikely that such a movement will continue if Boris Johnson becomes the next head of state.

Even now, four years on from the memorial���s completion, Britain���s commemoration and representation of the Mau Mau rebellion has failed to accurately represent its events. Upon the day of the unveiling of Nairobi���s new Mau Mau monument, the British High Commissioner stated that “we should never forget history.” Yet, Mau Mau has continued to be an era of British history which has been misrepresented to protect the idea of the Great British Empire.

In May 2019, the Imperial War Museum in London contained no mention of the Mau Mau rebellion. Considering the truly imperial nature of the conflict. It is damming to the British heritage industry to see no discussion of this within the museum.

However, the National Army Museum contains a small exhibit discussing the rebellion. The discussion of the Mau Mau rebellion was featured in a display with the word “torture” directly behind a small collection of Mau Mau weapons. Underneath them, lay the words “is torture justified if it provides valuable intelligence?” In the context of the Mau Mau rebellion, the “valuable intelligence,” which interrogation attempted to collect, was to be used to prevent the liberation of oppressed African people from the violent grip of the British empire.

Upon reading this, it seemed that a more historically accurate representation of the Mau Mau detention camps would be apparent in this display. Yet, the exhibit only highlights that “torture and summary executions occurred in British detention camps.” Little detail was provided, and the extent of the violence was left undiscussed. The display only revealed that 11 detainees were killed at the infamous Hola camp and 20 Mau Mau suspects were killed at Chuka camp. Interestingly, this exhibit stated that the Mau Mau fought against the British “often with brutal methods.” This has signified that the British were somewhat justified in their actions.

The exhibit states that it was “alleged” in 2009 that 90,000 Kenyans were “executed, tortured or maimed” in the conflict. There has been no text added to the exhibition to highlight that the findings of the trial.

This limited discussion of the rebellion, has done little to deconstruct British colonial myths. Evidently, British public history of the rebellion has provided little insight to the disgraceful activities of the colonial authorities during this period.

More must be done to ensure that the history of the British empire is represented bereft of ideas of British imperial piety and the archaic ideology of the civilizing mission. It is exceedingly unlikely however, that this notion will be a priority for a Prime Minister who believed that ���the best fate for Africa would be if the old colonial powers ��� scrambled once again in her direction.���

June 25, 2019

From Mogadishu to Toronto

Toronto. Image credit Mike Hewitt via Flickr (CC).

Partway through Hassan Ghedi Santur���s new novel The Youth of God, eighteen-year-old Nuur sits alone in an empty playground at night, staring up at the lights of the apartment complex that is home to his and numerous other Somali families in the neighborhood of Dixon in Toronto. Dixon is a neighborhood that, outside the world of the novel, is consistently portrayed in the media as a breeding ground for violent gang activity and is notoriously associated with late former mayor, Rob Ford, and his illicit drug activity. One of two Somali ��migr�� protagonists, Nuur is reminded of a book he has recently borrowed from the library, ���From Mogadishu to Dixon: The Somali Diaspora in the Global Context. [Nuur] found it interesting but dry and academic, full of statistics and lacking life.���

By contrast, Santur���s new novel foregrounds the lived experience of multiple inhabitants of Dixon as they negotiate their varied Muslim and migrant identities in the 21st century. Rather than statistics and graphs, readers are taken on a journey through the Somali diaspora in a literary narrative that engages with the abuse, exodus, and regret of numerous characters who ���had nomad blood surging through their veins. It was in their DNA always to seek a better place, to find it, and make it their own.���

While readers saw Santur give voice to harrowing accounts of African migration across the Mediterranean in his 2017 reportage “Maps of Exile” for Warscapes, in the The Youth of God we are privy to the affective experiences of resettlement and its aftermath in a deeply convincing work of fiction. It is convincing, no doubt, in part due to Santur himself having left Somalia to Canada at the age of 13. He appears to draw on this personal experience in setting the novel in Toronto, a city more often associated with being a home to Canada���s liberal democracy than with the struggling migrant communities we encounter in this novel.

In a contemporary climate rife with Islamophobia, Santur humanizes the radicalization of Nuur, a remarkably bright and motivated high school student who is alienated from his peers and family by his unwavering faith. Born in Toronto after his parents escape civil war in Somalia, Nuur flees school bullies and his abusive father, seeking refuge in different homes that he carves out for himself, particularly once his older brother moves away to work the oil rigs in western Canada. Nuur turns into himself and his ���consciousness was as vivid as a dream and as welcoming as home��� as he disappears into his schoolwork and extra-curricular reading.

Santur alternates the narrative focus between Nuur and his second protagonist, Nuur���s biology teacher Mr. Ilmi. The middle-aged Ilmi returns to Somalia after a 25-year absence, enacting a form of migrant return that has been the focus of a number of contemporary African literary works (prominent in fellow Somali writer Nuruddin Farah���s work but also works by Chimamanda Adichie, Sefi Atta, Teju Cole, Fatou Diome, Yaa Gyasi, Okey Ndibe, and Taiye Selasi). Mr. Ilmi, like many of his fictional contemporaries, returns to an all-too-familiar but foreign environment that fulfills his sense of nostalgia at the same time that it departs from his cherished childhood memories. In the recounting of his travels home to Mogadishu before an audience of academics at the University of Toronto, Mr. Ilmi feels uncannily ���like a novice reporter from some Western country, on his first foreign assignment, stringing together seemingly important facts for the edification of an ignorant reader.��� His inability to publicly call out the causes of conflict or the failure of the international community to provide adequate help stands in direct opposition to his prowess to immediately recognize and name ���Bach���s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major��� when he walks by a student rehearsal. The shame he feels in such moments of assimilation at the expense of his Somali identity compounds with his guilt for having left Somalia in the first place. Like his favorite student Nuur, Mr. Ilmi also struggles to belong.

The migrant struggle that Mr. Ilmi and Nuur face is also articulated through the experiences of those who come with them. The Somali-Canadian experience���similar to migration narratives���is one of disillusionment, in terms of employment, standard of living, and personal relationships. When Nuur���s parents flee Somalia, his father is a successful and fairly-renowned architect while his mother, Haawo, is a respected flight attendant. In Toronto, however, his father is forced to drive a taxi cab while Haawo works at Walmart, downward shifts in status that are so common to the diaspora that Santur doesn���t emphasize the point. Their relationship suffers when Nuur���s father moves to Minnesota to marry a second wife but returns home to assert his authority at will. Mr. Ilmi���s wife, Khadija, on the other hand, is forced to abandon Kismayo and her feelings for a local man when she marries the biology teacher in an arranged union that takes her to Canada but enables her to send remittances home to support her sisters. Mr. Ilmi, whose life in Toronto is marked by a ���litany of regrets,��� abandons his youthful fantasies of what love and marriage would be like to marry Khadija.

While Santur provides compelling and complex characterizations of Nuur and Mr. Ilmi, the depiction of the fanatic Imam named Yusuf is more straightforward, to the point that the homophobic and misogynistic imam who celebrates the 2015 terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo embodies a stereotype of Islamic fundamentalism. The contrast between Nuur���s two main mentors, Mr. Ilmi and Imam Yusuf, represents a general good versus evil dichotomy that Santur (as narrator) himself critiques as simplistic through his verbal undressing of Imam Yusuf who ���tak[es] it for granted that there were only two paths in life.��� Unfortunately, the risk of not humanizing the imam further in a book that is bound to circulate in the West is that the character potentially feeds into what is already an Islamophobic and vilifying discourse on the subject.

Santur has a clear interest in foregrounding moments of education for his characters who, in their yearning to belong and understand the world, demonstrate a clear passion for learning. The relationship between migration and education is illustrated through several instances in which Nuur or Mr. Ilmi are introduced to new anatomical, philosophical, and religious ideas and concepts that in some scenes are referenced at length. Here, Santur gestures to the notion that there is always more to be learned and perhaps always more to a story. Such a point is certainly underlined by the end of the novel as narrative closure is foregone in favor of remaining authentic to the world that Santur has so meticulously carved out for readers.

Such a world, and the characters that inhabit it, evokes the work of Santur���s Somali contemporaries. In writing The Youth of God, Santur has carved a space within what is an expanding canon of Somali literature written in European languages, a canon he shares with the likes of Nuruddin Farah, Cristina Ali Farah, Nadifa Mohamed, and Diriye Osman.

The Youth of God is a compelling narrative of Somali assimilation in an Islamophobic western world. Santur eloquently depicts various struggles of the Somali diaspora that cut across generations, genders, and geographies as he simultaneously humanizes but does not justify a radicalization that transcends borders.

Victory over Vedanta

Zambia, Barotse Floodplain, November 2012. Image credit Felix Clay via WorldFish Flickr (CC).

In a historic ruling, the UK Supreme Court has allowed 1,826 Zambian villagers to continue to pursue their case (Lungowe v. Vedanta) against UK-based mining giant Vedanta in the UK courts. The villagers from Chingola, in Zambia���s copper belt, have been fighting for over a decade for compensation following serious pollution from a mine owned by Vedanta���s Zambian subsidiary, Konkola Copper Mines (KCM), which poisoned their land and waterways. (More on the background of the case here.)

The ruling is a significant step forward.��A positive outcome isn���t certain���the company has vowed to ���defend itself against any such claims at the appropriate time������but for now, the door is still open. The case has significant implications for other victims of business-related human rights abuses and for multinationals, because it expands the parameters of a company���s legal ���duty of care.���

Such cases also raise a familiar question: are Western multinationals��� investments in Africa delivering sufficient financial and developmental benefits to the host countries? And what more can be done to ensure they don���t palm off their responsibilities?

The ruling

In the Vedanta case, the Supreme Court ruled that a UK parent company can arguably owe a duty of care to people affected by its subsidiaries��� operations, on the grounds that they could be impacted by the degree of control exercised by a parent company over its subsidiary. This expanded on a 2012 ruling (Chandler v Cape Plc) which found that a UK parent company could owe a duty of care to employees of its subsidiaries.

The judges gave clear examples of what could constitute ���control.��� A parent company might establish policy and guidelines for its corporate group, take active steps to make sure these are implemented, or make public commitments relating to its responsibility to communities and the environment which it then fails to put into practice.

In this case, the judge cited Vedanta���s own public commitments which stated that the company had control over the Zambian mine and was responsible for KCM���s operating standards. Significantly, this implies that a company���s ���Corporate Social Responsibility��� commitments are worth more than the glossy pages that they���re printed on���companies must be held accountable for them.

The judge also acknowledged that the claimants would have faced significant barriers to bringing the company to justice in their own country, including lack of funding to advance their claims in a Zambian court.

Vedanta���s shady activities in Zambia

One month after the ruling, the Zambian Government announced plans to liquidate KCM and renationalize or distribute its assets, alleging that Vedanta had violated its mining license (in a possible reference to the Chingola pollution) and failed to pay tax.

The news has rattled foreign investors, with some seeing the move as an attempt to offset Zambia���s debts and shrinking foreign currency reserves. And while the Government claims Vedanta has not been investing in KCM, the company says it operates in a challenging financial environment, with KCM not making a profit in recent years.

But this is not the full story. Campaigners have documented the parent company���s opaque financial structures, revealing how operating through shell companies registered in secrecy jurisdictions has allowed the firm to evade tax���despite being granted generous terms by the Zambian Government. In May 2014, a video emerged showing Anil Agarwal, Vedanta���s founder and chairman, mocking the Zambian Government for selling KCM for peanuts.

What next for parent company liability?

The Zambian farmers��� case will either be settled or will go to trial in the High Court at a date to be determined. In the event of KCM���s liquidation, the approval of the Zambian courts would be needed to allow the UK legal action to continue.

But there is less clarity for victims in other cases���and for companies. Last year, in a case brought against Royal Dutch Shell and its Nigerian subsidiary for devastating oil spills in the Niger Delta, the UK Court of Appeal found that publication of group-wide human rights policies was not in itself sufficient to place the parent company under a duty of care. Precisely the same argument was rejected by the Supreme Court in the Vedanta case.

This creates a great deal of uncertainty about the responsibilities of companies and the prospects of redress for people harmed by corporate activities. The claimants in the Shell case are now waiting to find out whether they too can take their fight to the Supreme Court.

Calls for a new law

In April, 25 UK NGOs and trade unions launched a call for a new law to make UK companies take action to prevent negative impacts on human rights and the environment from their international operations (including their subsidiaries) and supply chains.

This would provide clarity for business on their responsibilities. If harms did occur, the burden would be on companies to prove that they had implemented appropriate procedures, making it easier for people from communities like those in Chingola to hold them to account in court.

Such regulation will undoubtably face some opposition from business. But the current situation cannot continue. It is essential to ensure that UK companies benefiting from their investments in African countries do not so at the expense of Africa���s citizens.

June 24, 2019

Skin politics in northern Ghana

A soccer game in Bawku, Ghana in 2008. Image via G-list Foundation Flickr.

Between the years 2007 and 2012 alone, the United Nations Development Program���s (UNDP) draft report for conflict mapping captured over 59 violent conflicts in the northern part of Ghana. The most notable among these are chieftaincy disputes in Bimbilla, Dagbon (now resolved) and the Bawku Skin Affair.

Bawku is a municipality in the north-eastern corner of Ghana. It is also the site of a long-standing conflict dating back to British colonialism in 1930s over who should rule the area. At the heart of the conflict is the ���Bawku skin affair.��� Two groups���the Mamprusis and the Kusasis���are at the heart of the conflict over political power. The violence between these communities is intermittent and has resulted in the loss of human lives and the destruction of properties.

As Christian Lund, a Danish development studies scholar wrote in 2003, in a now seminal article, ���skin is the symbol of chiefly authority in northern Ghana, equivalent to the stool in the south ��� When a chief is enskinned, he is seated on the skin of an ox sacrificed for the occasion.��� In the 1950s, just before and immediately after independence, these conflicts took on a particular urgent turn: political parties exploited these tensions and at various points, both military regimes and democratic governments in Ghana have exploited the conflict to their advantage. Subsequently, the skin affair has implicated post-independence party politics, conflicts over markets and land and, obviously, over names of places.

Bawku is also where I conducted fieldwork for my PhD. I wanted to know why the educational, health, economic and the general welfare of the people of Bawku have been neglected for so long.

For instance, local people don���t trust the national government to solve the crisis. Although the state remains indispensable if this conflict is to be permanently resolved, it has so for shown it lacks�� political will to implement any meaningful decision. During former President John Kufuor���s reign, huge resources were invested into this conflict through the National Peace Council. What has become of that report? An interviewee concluded: ���President Kufuor only wasted national money on us and the National Peace Council. Hotel accommodation, food, allowance for several days, all gone wasted. Nothing came out of it. Where is that report? No government commitment!���

Unemployment, especially among the youth in the area, is high at 10.9%. The youth feel trapped in the conflict and are becoming psychologically disoriented and absorbed by a violent war culture. Mutual suspicion between the Mamprusi and the Kusasi makes Bawku still volatile. Each of them have become so cynical and distrustful that there is a build-up of reciprocal negative images, which is perpetuating antagonism and solidifying the conflict.

Arms and ammunition circulate widely in the area, which not even the National Commission for Small Arms and Light Weapons (NCSLW) and the security agencies can deny. The porous nature of Ghana���s borders and lack of effective internal mechanisms for arms control, coupled with instability in neighboring Togo and Cote d���Ivoire, make access to fire arms easy. When I inquired from a chief about the sources of the arms, his response was:

I know that people go to Accra, Kumasi, Tamale, Ouagadougou to get the weapons. Those Burkinabes who were involved in the Ivorian crisis returned with weapons and were ready to sell. So, if you have contacts and you inquire discreetly you will get them. If you are desperate you will sell cattle and buy. ��� But the weapons in the system are uncountable. Who is a fool to return them? Who knows when there will be an eruption? (Emphasis is mine).

Another interlocutor, a director of an NGO involved in the peace process, said:

There are a lot of arms in the system. As for that there is no doubt. But where they get them and hide them you can���t tell. Both sides have them in abundance and of all kinds but where they hide them you never can tell and the availability of arms is a threat to the community and the nation.

In Bawku, the acquisition of a weapon is treasured more than building a house. The youth take pride in selling pieces of land and cattle, and using the proceeds to acquire guns. Nobody can deny the proliferation of small arms in the area. Bawku chiefs and elders cannot claim to be ignorant of the “arms race” going on particularly between the two main ethnic groups in the conflict.�� Even more alarming is that, the other ethnic groups have joined in the “arms race” as they are always caught between crossfire each time the conflict flares up.

Besides, the conflict has assumed another worrying trend, resulting in a covert collective resolve by the Kusasis to attack any Mamprusi and Mamprusi sympathizer in their communities should the conflict recur. Hitherto, the conflict was purely between the Mamprusi and the Kusasi within Bawku. That was why each time there was an outbreak of hostilities, a Mamprusi could seek refuge in Kusasi dominated communities and vice versa outside Bawku. The development of a separate satellite market where the Kusasis conduct their business on market days confirms the continued existence of strict divisions between the two ethnic groups. Trust has completely broken down while mistrust and suspicions have become the norm. Actions are driven by the “we” and “them” syndrome, which can only block opportunities for peace.

The Bawku Interethnic Peace Committee (BIEPC), as well as the execution of the “Burial of the Okro Stalk” program cannot be the panacea to the Bawku crisis. The BIEPC, per its terms of reference, has no mandate to discuss the substance of the conflict let alone resolve it. The conflicting parties are two completely different ethnic groups with completely different cultures. As for the “Burial of the Okro Stalk,” it is a Kusasi traditional conflict resolution mechanism in which the stalk of an okro plant is planted and all parties to the conflict swear to it never to engage in any act of violence in the community thereafter. The Burial of the Okro Stalk is not a Mamprusi tradition and I, therefore, do not see how the Mamprusis can be committed to it as a way of reuniting the protagonists.

Ironically, this conflict can easily be resolved if any ruling government shows the will and commits a third of the energy and resources invested in the Dagbon Crisis. So much evidence exists that it only requires political will, well-resourced state institutions and individuals with integrity to resolve this seemingly intractable conflict. A committee of eminent chiefs, the Ghana National House of Chiefs and the Ghana National Peace Council are capable of investigating the claims of parties to determine whose is legitimate.

Politicians, particularly ethno-politicians, chiefs and people of Bawku must take bold steps to give stable peace a chance in Bawku. Let us ignore claims out there that the conflict is over. Yes, the guns are silent, but the conflict is far from being over.

Palm oil production, good or bad for Africa?

Sonni Nyumah, palm oil market seller, Liberia. Image credit Flickr user Hodag (CC).

Palm oil is one of the most rapidly expanding crops in Africa, and has been lauded as a valuable contributor to poverty alleviation and food independence in developing countries. But it has also been accused of producing harmful externalities; most notably bad health and environmental degradation.

The African oil palm tree (Elaeis Guineensis) is native to West Africa, where it was originally used as a staple food crop, its use has been dated to as far back as 3,000 BC Egypt. During the 1800s, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, it was brought to South-East Asia as a cash crop by European traders. Indeed, until recently, most cultivation took place in Indonesia and Malaysia. As an agricultural��crop, oil palm trees are grown across tropical, high rainfall, low-lying areas, typically occupied by moist tropical forests and rainforests, particularly in Africa. This zone is one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems on earth.

Palm oil comes from the fruit of oil palm trees and is exceptionally versatile, used for everything from cooking oil and as a key ingredient in many processed foods���including bread and even ice cream, to non-edible products, like cosmetics and biofuel. It is also an extremely efficient crop, offering significantly higher yields and lower price of production compared to other oil crops. But at what cost to the environment and local communities in the countries in which it is cultivated?

Environmental and social concerns are amplified by the escalating expansion of palm oil plantations in tropical areas. The obliteration of the forests to make way for plantations and the devastating affect this has had on wildlife has received the most press, especially around the decimation of orangutan and chimpanzee populations and other endangered species through the loss of their habitat. Less publicized, but equally concerning, are the impact on climate change and severe soil erosion resulting from deforestation.

Herakles Capital has been accused of breaking several national and international environmental laws in its 19��000 hectare palm oil concession in Cameroon, including illegal deforestation and illegally exporting timber from its deforestation activities (Greenpeace, 2013). There are also several critically endangered species living within the contracted land area and within the nature reserve adjacent to the project.

Herakles Capital has been accused of breaking several national and international environmental laws in its 19��000 hectare palm oil concession in Cameroon, including illegal deforestation and illegally exporting timber from its deforestation activities (Greenpeace, 2013). There are also several critically endangered species living within the contracted land area and within the nature reserve adjacent to the project.There are serious social consequences associated with the booming palm oil industry as well. From a human rights perspective, the alarming prevalence of abuses, including child labor and exploitation of workers, is gradually being brought into the open by organizations such as Amnesty International, however, conflicts between local communities and plantations on access to and ownership of land, as well as marginalization of smallholders in innovations in oil palm production and management, still receive little attention. In addition, local farmers are marginalized in the processing of palm fruit to oil, utilizing old technology resulting in low yields, and African governments have played a limited role in harnessing palm oil for value-added manufacturing to date.

Several human rights abuses have been reported in Sime Darby���s 300,000 hectare palm oil investment in Liberia, for instance, the community were never consulted and several households were forcibly displaced from their land, while their crops were destroyed. The company has now taken corrective action, such as ensuring consultations with the community are undertaken before planting occurs.

Several human rights abuses have been reported in Sime Darby���s 300,000 hectare palm oil investment in Liberia, for instance, the community were never consulted and several households were forcibly displaced from their land, while their crops were destroyed. The company has now taken corrective action, such as ensuring consultations with the community are undertaken before planting occurs.Access to land is closely linked to food security, poverty alleviation, sustainable livelihoods, and rural transformation. Monitoring LSLAs, which can limit access to land, is therefore an important issue. But the controversial context and complex realities of LSLAs, as well as their potential for creating conflict, mean land deals often take place behind closed doors and information on land tenure is not always available. This lack of transparency can lead to the exclusion of local stakeholders and weaken their position in the process.

The Land Matrix is an independent global land monitoring initiative that promotes transparency and accountability in decisions over LSLAs in low- and middle-income countries. By capturing and sharing data about land deals on its online open access platform, including intended, concluded, and failed attempts to acquire land through purchase, lease or concession for agricultural production, industry, and mining, the Land Matrix aims to stimulate inclusive debate on the trends and impacts of such acquisitions and, in so doing, contribute to strengthening the positions of weaker stakeholders in the political and administrative processes that govern access to land.

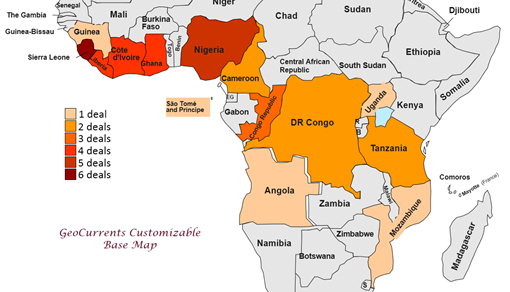

Using Land Matrix data to compare family farms in Africa, which range from around 0.5 to a maximum of 10 hectares, with the 1.58 million hectares currently being used for palm oil concessions���an area similar to the size of the whole of East Timor in South East Asia, or equal to 2.2 million soccer fields���paints a stark picture of the situation the majority of local communities already face. Moreover, these land area figures only relate to land deals where palm oil is the only crop���if we consider all deals which contain palm oil (and produce several other crops), the concluded land area size swells to over 3.4 million hectares, and in fact is the crop with the largest concluded land area in Africa, with jatropha coming in second at 2.5 million hectares. Added to this, several countries have recently expressed interest in attracting increased investment in palm oil production and processing, such Tanzania. Even more important than the size of the land area, however, is the location of the deals themselves, which, as the map depicts, is across the sensitive tropical belt.

Number of deals per country.

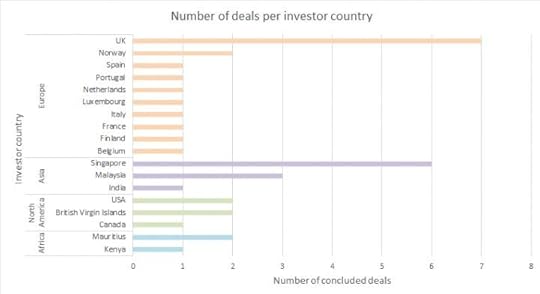

Number of deals per country.Palm oil sector-related LSLAs in Africa are dominated by foreign investors, from stock exchange-listed, public, and private companies, to individual entrepreneurs from countries across the globe. Investors from the United Kingdom, Ireland, Singapore, and Malaysia have concluded the highest number of deals, but regional investments by companies based in Kenya and Mauritius are also significant. Nevertheless, the lack of local investors is glaring. Furthermore, although contract farmers, or “outgrowers,” are used by foreign investors to increase their output, they are seldom given fair payment, and are subject to strict conditions for payment, such as when delivery should take place. In addition, foreign investors generally process fruit to oil in the country of origin, and then ship the oil to their warehouses in other countries for further processing. Few jobs are therefore created locally in the processing and manufacturing sectors.

In many ways, the debate around palm oil is futile, given that there is no better alternative currently. Other vegetable oils would be as, if not more, detrimental to the environment and surrounding communities since they require a lot more land for a lot less yield, and besides, palm oil is by no means the only culprit when it comes to the destruction of biodiversity and ecosystems; cocoa, coffee, and soy are just a few of the other perpetrators.

Number of deals per investor country.

Number of deals per investor country.But there are less harmful, more sustainable ways of cultivating and producing it, while maximizing the benefits to local populations, from economic development, to job creation and upskilling. Several sustainability initiatives have already been introduced in response to the social and environmental concerns, including the Indonesian Initiative for Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) and Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Formed in 2004, the RSPO is a not-for-profit international initiative which has developed a set of environmental and social criteria that companies must comply with in order to produce Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO). These include not clearing primary forests or areas which contain significant concentrations of biodiversity or fragile ecosystems, minimizing erosion, and protecting water sources. Other RSPO principles stipulate a significantly reduced use of pesticides and fires, fair treatment of workers according to local and international labour rights standards, and the need to inform and consult with local communities before the development of new plantations on their land.

Consumers themselves also have an extremely important role to play. Firstly, they can educate themselves and make others aware of the environmental and social consequences of palm oil. Secondly, they can put pressure on companies to only use palm oil from CSPO certified companies or improve their environmental and social practices if they produce it themselves.

Ultimately though, despite the intervention of global conservation organizations and buy-in from major consumer companies, like Unilever and Nestl��, without government support in producing countries, the changes required to harness the benefits of palm oil and minimize the negative impacts will not be realized. But with the right data we can help influence the policy-making process around LSLAs for the palm oil industry and facilitate greater public involvement in critical decisions that affect the lives of all land-users.

June 23, 2019

Gender in Cameroon’s anglophone crisis

Mendouga Rita plants Gnetum in the village of Minwoho. Leki��, Center Region, Cameroon. Image credit Ollivier Girard via CIFOR cifor.org blog.cifor.org (CC).

Women have undertaken measures to cope and resist against the backdrop of Anglophone���Francophone tensions in Cameroon, a country that is currently embroiled in political crisis, escalating human rights abuses, and on the brink of civil war because of separatist conflict. These tensions date from 1918, when Britain gained control of the smaller, western part of Cameroon, the regions then known as the Northern and Southern Cameroons, and France gained control of the more substantial eastern part, French Cameroun. In 1960, Francophone Cameroon gained independence through a violent struggle and Anglophone Cameroon through a UN vote. Through a process Anglophones have long decried as unjust, the former Southern Cameroons unified with former French Cameroun in 1961, and Anglophones have been politically and economically marginalized ever since, as Piet Konings and Francis Beng Nyamnjoh highlight in their work on Anglophone identity.

Anglophone resistance and state repression intensified in 2016, creating highly militarized settings that subject women to displacement, gender-based violence, loss of loved ones, and other forms of violence as Anglophone men on both sides of the Atlantic protest Anglophone subjugation. Women find themselves in crosshairs, whether they encounter conflict with state security officers or armed Anglophone separatists, and are encouraged to participate in “Ghost Town��� protests, or strikes, where Anglophones withdraw from public life, desert the streets, and bring economic activities to an abrupt end.

���I am happily reading the first article [but] our environment is not the best because of gun shot[s],��� Annie wrote to the African Feminist Initiative (AFI) listserv. Annie���s congratulations to some of the AFI members who had contributed to a special journal issue on African feminisms in December 2018 were very enthusiastic, yet her depiction of her circumstances were troubling. She explained that she ���was writing [from] under [the] bed��� in her home in Buea, a large English-speaking town in southwestern Cameroon. Members reached out in solidarity. Amina Mama, who helped found the African gender studies journal Feminist Africa, wrote back:

I was so sadly moved by your account, as a person who remembers hiding under her bed with carnage all around (as a child).��I want to note what you said���you are reading African feminist writing, while hiding under your bed and hearing gunshots!

Mama offered words of encouragement: ���[P]lease keep your head down���we have every reason to survive, re-group and re-sist the scourge of militarization on our continent.���

Women like Annie and Amina frequently face erasure in narratives about violent (militarized) political movements. As an African feminist, I have been interested in adaptations like theirs, and have explored them as vital strategy to survive and exercise agency in the context of violent conflict. As feminist scholars have pointed out, stories of violent conflict often portray women as passive victims, failing to highlight their agency in unstable settings (e.g., Jill Vickers, 2016).

This report will highlight the experiences of a few Cameroonian feminists, bringing to life the many ways women strive to cope in a turbulent Cameroon, to counteract those portrayals. Highlighting snapshots���moments of agency���of some women���s everyday lived experiences belies representations of women as mostly passive subjects and victims in violent and militarized surroundings.

Debates about the ongoing crisis in Cameroon tend to ignore how women have and continue to navigate the tempestuous political landscape in unique ways, exercising both individual and collective authority. This work will examine how women living in militarized locations in Cameroon survive, resist and exercise agency by, for instance, fighting for gender equality when attempting to create a more hospitable environment for girls and women. As Alicia Decker reminds us in her 2014 work on gender and militarization in Uganda, women ���employ various strategies to mediate the violence��� they face, rather than being ���simply victims.��� Amina Mama and Margo Okazawa-Rey��similarly remind us in a 2008 issue of Feminist Africa that women engage in ���feminist activism against militarism���: ���Women all over the African region have not only participated in, survived and resisted violent conflict, but played key roles in facilitating negotiations and peace-brokering efforts.��� Thus, this report complements those by AIAC contributors such as Kangsen Feka Wakai,��Meredith Terretta, and Melchisedek Ch��tima, which highlight the various dynamics of the Anglophone crisis by examining how women refuse to be ���simply victims.��� I might do this by privileging their voices and experiences, peering at freshly developed snapshots of their current lived realities.

As in other African countries, Cameroonian women have long used traditional associations and organized obstructs to gain collective power during political and economic crisis. As Filomina Steady asserts in her work on women���s collective activism and women���s traditional secret societies in Liberia, such societies ���serve as mechanisms for the mobilization of women for development and democratization.��� In keeping with this heritage, traditional forms of protests have been a feature of women���s protests in today���s Cameroon. In late 2017, for example, Anglophone Cameroonian women mobilized Takumbeng, (or Takembeng), using traditional forms of protest and transnational networks to foster political solidarity, Anglophone inclusion, and nationalist aspirations. Twitter and YouTube videos show that protests took place in both Anglophone Cameroon and abroad in September and November 2017. This rural-based, traditional secret society of women in their sixties and seventies dates to pre-colonial traditions. Because Cameroonians, such as male state security officers, still consider the sight of a vagina in public to be bad luck, the women���s frequent use of naked protests still intimidate and shame. The protests have also innovated by including women of all ages���although only menopausal women disrobe���drawing on the traditional maternal authority of the Takumbeng while increasing their numbers and expanding their powerbase.

However, less traditional women���s organizations have also mobilized in response to the ongoing conflict. As one news report about Cameroonian women���s leadership actions revealed, women���s ���near invisibility in the media has not stopped the leadership aspirations of a growing group of female leaders.��� For instance, Zoneziwoh Mbondgulo-Wondieh is a Cameroonian feminist activist and has been a leading voice amidst the crisis. Mbondgulo-Wondieh is Executive Director of Women for a Change, Cameroon (Wfac), an organization that works on the empowerment and leadership of women and girls, and their sexual and reproductive health rights. Also, an AFI member, Mbondgulo-Wondieh attested in a recent AFI audio conference that women���s organizations in Cameroon are holding press conferences and reaching out to government officials to describe their pain and suffering due to the current conflict. In a follow-up conversation with me via email, Mbondgulo-Wondieh shared that Wfac collaborates with other organizations such as the South West/North West Women���s Task Force��(SNWOT), and that its ���peaceful activities��� include campaigning on social media and reaching out to ���top government officials,��� demanding that officials include women (of all ages) in ongoing dialogues about the crisis. Mbondgulo-Wondieh outlined the ultimate goals of many Cameroonian feminist activists:

Complete cease fire between the conflict parties.

Lobby your respective government authorities to pressure the government of Cameroon to initiate dialogue and accept [to] mediate for peace.

The peace negotiations must include women.

Be our loudspeaker [read: help advocate on their behalf] as many of us living in the country can’t be very vocal as we have become targeted by both conflicting parties.

She sent me the SNWOT Position Statement, which dated from Human Rights Day in December 2018 and urged me to circulate the petition.

Mbondgulo-Wondieh also informs me that on International Women’s Day (March 8), Wfac organized a social media campaign to bring global attention to the plight of women and girls in the conflict in Cameroon. Like many female leaders in today���s Cameroon, she sought to express agency in addressing women���s grievances in political crisis across national borders. Further, Mbondgulo-Wondieh���s actions demonstrates that women are not merely passive victims amid violent political strife. Instead, many women seek to find ways not only to end the crisis, but place women at the forefront of conflict resolution.

But women also act as individuals to bring attention to the ongoing crisis. Monique Kwachou, a Cameroonian feminist journalist and blogger, is a friend of mine. When she announced she would be returning home to an Anglophone town in Cameroon to write her dissertation after defending her PhD proposal at a university in South Africa, I told her how much I feared for her safety, but she was determined. She later penned an emotional blog post in January 2019 about her many answers to the question ���how is home?���, highlighting the daily realities for Cameroonians generally and women particularly in Anglophone towns, such as the constant fear of kidnapping and the fact that many young girls cannot attend school. But she also wrote of how everyday women find ways to survive, for themselves, for their daughters. As Monique recounts, mothers who know she is highly formally educated frequently ask her to adopt their daughters, saying, partly in Cameroonian Pidgin English, or Cameroonian Creole: ���This my girl is smart eh … she was performing very well in school before this crisis and she has not yet known ���life,�����abeg [I beg] take her so she can be helping you in the house.��� She later shared in a private email that she has been seriously considering fostering a child, most likely, as I concluded, as part of her endeavors to help girls in her community.

One day she sent me a video via WhatsApp of what life outside her window looks like on a ���Ghost Town��� protest day. The video opens with an image of lush palm trees, their bright green palms fanned out toward the sky. Birds chirped. The sunny scene immediately made me miss my family in Cameroon. Monique���s voice interrupted my reverie, though: ���I don���t know what���s happening [in] town, but this is the highway, and there is no car moving. So you can imagine��� The Ghost town is being respected; we���re all staying indoors.��� She panned the camera to show an empty road, not a car in sight. Just the sound of birds. It���s clear that this road is normally busy, cars honking, music. The 32-second video reflects Monique���s varied multi-layered experiences of today���s Cameroon. Stories like hers, like Annie���s, like Mbondgulo-Wondieh���s, remind us that women in Cameroon continue to employ various strategies to cope, resist, survive no matter the circumstances and, in many ways, go beyond their own individual needs to improve the lives of their female counterparts. Their stories are complex, showing the daily realities of women in Cameroon; Monique wrote pointedly in her blog, ���To properly respond to ���how is Cameroon[?]��� would demand I tell several stories of Cameroonians.��� In today���s Cameroon, women cope. Women act. Everyday.

Gender in Cameroon’s anglophone crises

Mendouga Rita plants Gnetum in the village of Minwoho. Leki��, Center Region, Cameroon. Image credit Ollivier Girard via CIFOR cifor.org blog.cifor.org (CC).

Women have undertaken measures to cope and resist against the backdrop of Anglophone���Francophone tensions in Cameroon, a country that is currently embroiled in political crises, escalating human rights abuses, and on the brink of civil war because of separatist conflict. These tensions date from 1918, when Britain gained control of the smaller, western part of Cameroon, the regions then known as the Northern and Southern Cameroons, and France gained control of the more substantial eastern part, French Cameroun. In 1960, Francophone Cameroon gained independence through a violent struggle and Anglophone Cameroon through a UN vote. Through a process Anglophones have long decried as unjust, the former Southern Cameroons unified with former French Cameroun in 1961, and Anglophones have been politically and economically marginalized ever since, as Piet Konings and Francis Beng Nyamnjoh highlight in their work on Anglophone identity.

Anglophone resistance and state repression intensified in 2016, creating highly militarized settings that subject women to displacement, gender-based violence, loss of loved ones, and other forms of violence as Anglophone men on both sides of the Atlantic protest Anglophone subjugation. Women find themselves in crosshairs, whether they encounter conflict with state security officers or armed Anglophone separatists, and are encouraged to participate in “Ghost Town��� protests, or strikes, where Anglophones withdraw from public life, desert the streets, and bring economic activities to an abrupt end.

���I am happily reading the first article [but] our environment is not the best because of gun shot[s],��� Annie wrote to the African Feminist Initiative (AFI) listserv. Annie���s congratulations to some of the AFI members who had contributed to a special journal issue on African feminisms in December 2018 were very enthusiastic, yet her depiction of her circumstances were troubling. She explained that she ���was writing [from] under [the] bed��� in her home in Buea, a large English-speaking town in southwestern Cameroon. Members reached out in solidarity. Amina Mama, who helped found the African gender studies journal Feminist Africa, wrote back:

I was so sadly moved by your account, as a person who remembers hiding under her bed with carnage all around (as a child).��I want to note what you said���you are reading African feminist writing, while hiding under your bed and hearing gunshots!

Mama offered words of encouragement: ���[P]lease keep your head down���we have every reason to survive, re-group and re-sist the scourge of militarization on our continent.���

Women like Annie and Amina frequently face erasure in narratives about violent (militarized) political movements. As an African feminist, I have been interested in adaptations like theirs, and have explored them as vital strategy to survive and exercise agency in the context of violent conflict. As feminist scholars have pointed out, stories of violent conflict often portray women as passive victims, failing to highlight their agency in unstable settings (e.g., Jill Vickers, 2016).

This report will highlight the experiences of a few Cameroonian feminists, bringing to life the many ways women strive to cope in a turbulent Cameroon, to counteract those portrayals. Highlighting snapshots���moments of agency���of some women���s everyday lived experiences belies representations of women as mostly passive subjects and victims in violent and militarized surroundings.

Debates about the ongoing crises in Cameroon tend to ignore how women have and continue to navigate the tempestuous political landscape in unique ways, exercising both individual and collective authority. This work will examine how women living in militarized locations in Cameroon survive, resist and exercise agency by, for instance, fighting for gender equality when attempting to create a more hospitable environment for girls and women. As Alicia Decker reminds us in her 2014 work on gender and militarization in Uganda, women ���employ various strategies to mediate the violence��� they face, rather than being ���simply victims.��� Amina Mama and Margo Okazawa-Rey��similarly remind us in a 2008 issue of Feminist Africa that women engage in ���feminist activism against militarism���: ���Women all over the African region have not only participated in, survived and resisted violent conflict, but played key roles in facilitating negotiations and peace-brokering efforts.��� Thus, this report complements those by AIAC contributors such as Kangsen Feka Wakai,��Meredith Terretta, and Melchisedek Ch��tima, which highlight the various dynamics of the Anglophone crisis by examining how women refuse to be ���simply victims.��� I might do this by privileging their voices and experiences, peering at freshly developed snapshots of their current lived realities.

As in other African countries, Cameroonian women have long used traditional associations and organized obstructs to gain collective power during political and economic crisis. As Filomina Steady asserts in her work on women���s collective activism and women���s traditional secret societies in Liberia, such societies ���serve as mechanisms for the mobilization of women for development and democratization.��� In keeping with this heritage, traditional forms of protests have been a feature of women���s protests in today���s Cameroon. In late 2017, for example, Anglophone Cameroonian women mobilized Takumbeng, (or Takembeng), using traditional forms of protest and transnational networks to foster political solidarity, Anglophone inclusion, and nationalist aspirations. Twitter and YouTube videos show that protests took place in both Anglophone Cameroon and abroad in September and November 2017. This rural-based, traditional secret society of women in their sixties and seventies dates to pre-colonial traditions. Because Cameroonians, such as male state security officers, still consider the sight of a vagina in public to be bad luck, the women���s frequent use of naked protests still intimidate and shame. The protests have also innovated by including women of all ages���although only menopausal women disrobe���drawing on the traditional maternal authority of the Takumbeng while increasing their numbers and expanding their powerbase.

However, less traditional women���s organizations have also mobilized in response to the ongoing conflict. As one news report about Cameroonian women���s leadership actions revealed, women���s ���near invisibility in the media has not stopped the leadership aspirations of a growing group of female leaders.��� For instance, Zoneziwoh Mbondgulo-Wondieh is a Cameroonian feminist activist and has been a leading voice amidst the crisis. Mbondgulo-Wondieh is Executive Director of Women for a Change, Cameroon (Wfac), an organization that works on the empowerment and leadership of women and girls, and their sexual and reproductive health rights. Also, an AFI member, Mbondgulo-Wondieh attested in a recent AFI audio conference that women���s organizations in Cameroon are holding press conferences and reaching out to government officials to describe their pain and suffering due to the current conflict. In a follow-up conversation with me via email, Mbondgulo-Wondieh shared that Wfac collaborates with other organizations such as the South West/North West Women���s Task Force��(SNWOT), and that its ���peaceful activities��� include campaigning on social media and reaching out to ���top government officials,��� demanding that officials include women (of all ages) in ongoing dialogues about the crisis. Mbondgulo-Wondieh outlined the ultimate goals of many Cameroonian feminist activists:

Complete cease fire between the conflict parties.

Lobby your respective government authorities to pressure the government of Cameroon to initiate dialogue and accept [to] mediate for peace.

The peace negotiations must include women.

Be our loudspeaker [read: help advocate on their behalf] as many of us living in the country can’t be very vocal as we have become targeted by both conflicting parties.

She sent me the SNWOT Position Statement, which dated from Human Rights Day in December 2018 and urged me to circulate the petition.

Mbondgulo-Wondieh also informs me that on International Women’s Day (March 8), Wfac organized a social media campaign to bring global attention to the plight of women and girls in the conflict in Cameroon. Like many female leaders in today���s Cameroon, she sought to express agency in addressing women���s grievances in political crisis across national borders. Further, Mbondgulo-Wondieh���s actions demonstrates that women are not merely passive victims amid violent political strife. Instead, many women seek to find ways not only to end the crises, but place women at the forefront of conflict resolution.

But women also act as individuals to bring attention to the ongoing crises. Monique Kwachou, a Cameroonian feminist journalist and blogger, is a friend of mine. When she announced she would be returning home to an Anglophone town in Cameroon to write her dissertation after defending her PhD proposal at a university in South Africa, I told her how much I feared for her safety, but she was determined. She later penned an emotional blog post in January 2019 about her many answers to the question ���how is home?���, highlighting the daily realities for Cameroonians generally and women particularly in Anglophone towns, such as the constant fear of kidnapping and the fact that many young girls cannot attend school. But she also wrote of how everyday women find ways to survive, for themselves, for their daughters. As Monique recounts, mothers who know she is highly formally educated frequently ask her to adopt their daughters, saying, partly in Cameroonian Pidgin English, or Cameroonian Creole: ���This my girl is smart eh … she was performing very well in school before this crisis and she has not yet known ���life,�����abeg [I beg] take her so she can be helping you in the house.��� She later shared in a private email that she has been seriously considering fostering a child, most likely, as I concluded, as part of her endeavors to help girls in her community.

One day she sent me a video via WhatsApp of what life outside her window looks like on a ���Ghost Town��� protest day. The video opens with an image of lush palm trees, their bright green palms fanned out toward the sky. Birds chirped. The sunny scene immediately made me miss my family in Cameroon. Monique���s voice interrupted my reverie, though: ���I don���t know what���s happening [in] town, but this is the highway, and there is no car moving. So you can imagine��� The Ghost town is being respected; we���re all staying indoors.��� She panned the camera to show an empty road, not a car in sight. Just the sound of birds. It���s clear that this road is normally busy, cars honking, music. The 32-second video reflects Monique���s varied multi-layered experiences of today���s Cameroon. Stories like hers, like Annie���s, like Mbondgulo-Wondieh���s, remind us that women in Cameroon continue to employ various strategies to cope, resist, survive no matter the circumstances and, in many ways, go beyond their own individual needs to improve the lives of their female counterparts. Their stories are complex, showing the daily realities of women in Cameroon; Monique wrote pointedly in her blog, ���To properly respond to ���how is Cameroon[?]��� would demand I tell several stories of Cameroonians.��� In today���s Cameroon, women cope. Women act. Everyday.

June 21, 2019

Coming to voice in Cuba

Cuban dance troupe, Havana Jan 2014. Image credit Marjorie Kaufman via Wikimedia Commons.

The history of the black body in Cuba is one deeply interconnected with slavery, exploitation, systems of oppression, and the arguable emancipation of these oppressions through the 1959 Revolutionary process. Dr. Esteban Morales Dom��nguez, writes that the relics of slavery and colonialism which encompassed ���prejudice, negative stereotyping, and discrimination��� against black people or non-white Cubans moved from the colony to the Republic and while the Revolution attempted to undo this history, it was only suppressed and silenced, rearing it���s head with the onset, post-Cold War, of the Special Period in the 1990s.

I spent two months in Cuba last summer. One afternoon as I walked along the Malec��n, Havana���s famed seawall, I started talking to a local, Ronald. To my surprise, our conversation about race was extremely direct. As I talked about my own experiences with race and racism in the US, he blurted out that ���it is hard for us here.��� He pointed to his skin and then to me and said, ������and even harder for [people like you].��� He meant for black women.

I was navigating my own racial and gendered identity, as an Afro-Caribbean womxn born in the United States, in a country where anti-black racism was often not acknowledged or widely discussed. Historically, in Cuba, there has been little room for the voice and identity of Black Cuban women.

In varied social interactions, I witnessed how welcoming and approachable Cubans were toward white or non-black people, but showed some resistance to my presence or that of other black women. Before traveling to Cuba, I had spent much time with the words of poet, Georgina Herrera, among other writers, and the visuals of filmmakers Sara Gom��z and Gloria Rolando, deepening my own understandings of Black Cuban identities and seeing the ways in which black women in Cuba were asserting their voices by and for themselves.

With the Cuban Revolution (1959) came the Federaci��n de Mujeres Cubanas (the Federation of Cuban Women), to reassess and redefine the role of women in society, as well as in land redistribution, and literacy campaigns in efforts to reorder the nation and give voice to those communities and identities, which had been historically oppressed.

Notably, Che Guevara���s 1965 letter, ���Socialism and Man in Cuba��� puts into motion a shaping of Cuban identity that exists monolithically and in surrender to the state.�� What became central to building a socialist discourse and new man/woman in Cuba was the moral and spiritual commitment to the nation. But do the relics of slavery, oppression and inequality, particularly for Black Cubans, and Black Cuban women, disappear that easily? In a conversation one afternoon towards the last weeks of my time there, a Black Cuban woman said to me: ������Remember, Cuba was one of the last nations in the Caribbean to abolish slavery [in 1886].���

Social structures upheld by the euphoria of the 1959 Revolutionary process began to fall apart���inequalities silenced and buried beneath revolutionary discourse and rhetoric re-emerged as the economy collapsed. As Roberto Zurbano, a Black Cuban writer and activist, argues, the dual currency (one pegged to the US Dollar) has only proliferated social inequalities, such as racism and discrimination.

The racial situation in Cuba has affected black women in a particular way, as they have suffered exponentially because of gender, extreme poverty, and race: a ���triple discrimination.���

Black consciousness movements of Latin America and the Caribbean Diaspora (i.e. Garveyism, negrismos, and negritude movements), created and in some ways renewed an interest in black identity, histories, culture and voices, previously excluded, however most understandings of the black woman ���focused on her beauty and her external physical features,��� according to Gabriel Abudu, a professor of French at York University in the US, who studies Cuba. The recovering of, or ���rehabilitation��� of, the black female identity always ���manifested itself��� in illuminating her sensuality and capacity of ���sensual love������the female solely perceived as another element in a ���[exotic] tropical environment��� and disregarded any thought beyond her skin color.�� This can be seen in newspaper ads which ���praised��� the strength and infinite abundance of the black woman during slavery, like in volumes/issues of Carteles magazine of the 1950s, or in the writing of poet Nicolas Guill��n, himself of mixed descent and a prominent figure in the Cuban state after the Revolution. The speaking of and for the black woman created a ���voicelessness��� rooted in the history of representations in which she was the object. Writers such as Excilia Salda��a, Georgina Herrera, and Nancy Morej��n, for example, during and following the Revolution, asserted their identities as Cuban, black, and woman���all three simultaneously.

As the editors of the 2011 edited volume, Afrocubanas: historia, pensamiento y pr��cticas culturales, wondered: ���[d]��nde queda la realidad historico-social de la mujer de color/negra [where does the historical and social reality of the women of color/black woman exist?]

Through the internet Black Cuban women are creating and accessing a wider network of imagining identities that intersect with and challenge the layered political and social grammars of the Revolution in the present.

Journalist Sara M��s suggests that while the black female in Cuban society remains the least visible, this voicelessness has been subverted by the emergence of informal internet spaces that make visible the stories and experiences of Black Cuban women in the diaspora.�� Whether through blogs or Twitter, black female journalist, artists, essayists, rappers, and poets have begun to make visible their experiences, making way for possibilities of engaging with the nation from black or afro-feminist perspectives, exploring Cuban identity through the intersections of race and gender. Blogs, such as Directorio de AfroCubanas, TUTUTUTU-Un bolet��n para la mujer lesbiana afrocubana, or Negra Cubana Ten��a Que Ser, have allowed for the negation of the stereotypes that have historically been associated with black women and are initiating a ���coming to voice��� of these identities through the digital sphere.

June 20, 2019

I, Surya

[image error]

Surya Bonaly. Image credit Xtraice via Wikimedia Commons.

The video streaming service, Netflix,��recently premiered a new show called Losers, chronicling the stories of athletes known for their failures. The athletes featured range from Canadian curler Pat Ryan, Sicilian runner Mauro Prosperi, French golfer Jan van de Velde, English soccer club Torquay United, and several others. French figure skater Surya Bonaly���s 1998 Nagano Olympics failure is also featured. You may remember Bonaly for her groundbreaking backflip that landed on one blade at these same Olympic games or, sadly, you may not know her story at all.

ESPN previously featured Bonaly���s story as part of Eva Longoria���s Versus series and she has appeared on a few podcasts, but did not return to the public eye until the release of I, Tonya (2017), which resulted in calls on social media for a biopic on Bonaly herself. At first, I balked at the notion that Bonaly could be included in any kind of show about losers; but upon further reflection, her unfair treatment due to unspoken racial stereotypes and prejudices did make her a loser, even if her athletic ability and performance was unparalleled.

Born in 1973, Bonaly was adopted in Nice, France by a white couple, Suzanne and Georges Bonaly. Although Bonaly���s parents and coaches told the media that Bonaly had been born on the French island of R��union, they later admitted that they concocted this story for publicity and that figure skater���s biological mother had been born on the island.��Initially, Bonaly trained as a gymnast, even winning the junior world championships in tumbling before becoming a figure skater in the mid-1980s after attracting the attention of famous French national coach, Didier Gailhaguet. This background in tumbling translated into Bonaly���s skating where she displayed great skill in jumping and landing, skills typically only performed by men. She quickly moved up the international junior ranks, winning gold at the 1990 Grand Prix International de Paris, the 1991 World Junior Championships, and the��1991 European Championships.

In 1992, she moved into the adult ranks, winning the 1992 European championships and qualified for the Albertville Olympics hosted on the same year. It was at this competition that Bonaly began to be penalized for her gravity-defying feats on the ice. In a practice session for the 1992 Olympics, she landed a backflip on the ice and was quickly ordered never to do so again by officials seemingly concerned with the safety of the other skaters. She also became the first woman to attempt a quadruple toe loop (a jump wherein the skater approaches backward, takes off from the outer edge of a skate, makes four revolutions in the air, and lands on the same outer edge) but again received backlash from officials who claimed her jump was under-rotated. Officials also criticized Bonaly���s appearance. In the Losers episode, white judge Vanessa Riley criticized one of Bonaly���s practice outfits, stating that it was ���more like a court jester. I think that something smart and dignified would have been more appropriate.���

After placing poorly in these Olympics, Bonaly parted ways with her coach, and took on her mother as coach. She struggled to recover from this shift, but recovered quickly, winning the European Championships in 1993 and 1994. She nearly medaled at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, but due to some falls placed fourth behind Oksana Baiul, Nancy Kerrigan, and Chen Lu. At the 1994 World Championships, Bonaly���s final score equaled Yuka Sato but the judges gave the gold to Sato in a 5-4 tiebreaker decision. Bonaly refused to stand on the medals podium and took off her medal after it was presented to her.

Again in 1995, at the World Championships, Bonaly lost by a small margin and Chinese skater Chen Lu took the gold. In an interview with Sports Illustrated after the controversial decision, legendary skating coach Frank Carroll explained the rationale behind the judges��� decision:

I���m genuinely fond of Surya, but they���d take Chen Lu because there���s just too much bad rap, too much bad publicity, too much bad talk about Surya that���s gone by. And, you know, it���s always the but that does her in: “Surya���s a great jumper, but . . .”; “Surya is a good skater who jumps well, but . . .” With Chen Lu, it���s just, “She���s a beautiful skater.”