Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 205

September 7, 2019

The emptiness of an ending

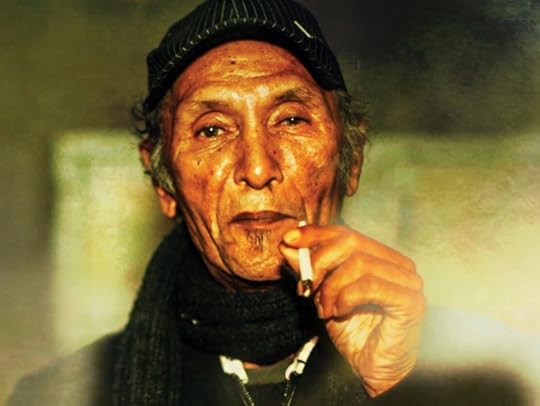

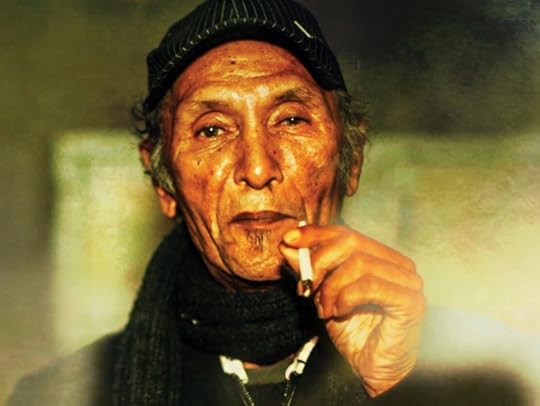

Robert Mugabe in Uganda 2010. Image credit Stttijn via Flickr (CC).

A day dawned with an early call.

Mugabe was dead.

And then, nothing. Nothing at all

in my heart and mind.

Just a gaping, blank canvas, waiting for a clear script to form out of the morass of both shadowy and sharp memories that had defined so much of the texture of the past four decades.

A day later, the emptiness begins to fill, first with older images floating up like old newsprint, in black-and-white. Hopeful ones like the signings at Lancaster House, a new flag raised, the jubilant mass rallies of the first independent elections. But others too: the dark silhouettes of government soldiers and brutalized bodies from the Gukurahundi era. Then full-color clips start to run like a speeded-up film. A collage of the personal and the political. Times of optimism and loss at both the intimate and the national scale. A spectrum of people and places reconstituted over time by the fortunes and misfortunes of Zimbabwe, shaped so profoundly by the dominating presence of Mugabe.

Mugabe, the grand overseer of progress, and simultaneously the master of darkness. A figure of national liberation and narrow authoritarianism.�� Discordance between promises and deeds, between narratives of inclusion and practices of exclusion. The constant abuser of ordinary hope within an increasingly heartless political landscape.

I came to know these contradictory forces early on, soon after independence, working together with committed ex-combatants and bureaucrats in government ministries in the “development decade” of the 1980s and into the early 90s. There was the invigorating energy of sharing a seemingly common national project of transformation with tangible results, but only if one wasn���t critical in any way of The Party (Zanu PF); only if one didn���t confront its self-proclaimed authority. The threats were either subtle or not, depending on who and where you were.

Into the 1990s, the trans-continental wave of democratization eased some of the tight constraints of authoritarianism, and generated a new sense of political freedom. But it was accompanied by the debilitating effects of neoliberalism and structural adjustment, undermining government���s ability to deliver public goods, and sowing seeds of discontent in many quarters.��The Party began to lose its credibility and monopoly of control, as multiple oppositional voices emerged and began to make political headway, embodied by the successful mobilization of a “no” vote in the constitutional referendum in early 2000, countering Mugabe���s call for a “yes.”

The backlash by Mugabe and The Party was immediate and extreme.�� Shrewdly rebuilding political legitimacy through a radical redistributive land reform program, widely recognized as necessary, it facilitated wide-scale and sustained violent attacks on all forms of opposition throughout the decade. The mask of an inclusive nation was crudely stripped away. Instead, the language of national belonging became narrower and narrower, reinforced by a discourse that linked the opposition with a form of neo-imperialist alliance.

For ordinary Zimbabweans, the everyday effects of the combined political and economic crises and mass rural and urban displacements were extensive, even while a political, military and business elite linked to Mugabe and his second wife Grace, dug in deep, indeed benefitting from the chaos of crisis.

A brief period of respite came in 2009���2013, when the devastation of the economic crisis forced concessions by Mugabe, and gave the main opposition MDC a foothold in a unity government. Sadly, through its own fragmentation, inexperience, and limited national vision the opposition squandered the opportunity to consolidate its political credibility, to the immense disappointment of so many that had suffered in the struggle to support it. To be fair, Mugabe���s political experience, backed up by The Party���s machinery and history of control, not least of the security sector, was hard to counter. Once again, Mugabe���by then over the age of out-maneuvered his opponents, “winning” his seventh successive election as Head of State.

Repeatedly, Mugabe���s presence dominated not only the political landscape, but the everyday lives, future possibilities, and consciousness of all Zimbabweans, one way or another. When he was finally deposed through a non-violent “non”-coup in November 2017, the relief of an imagined Mugabe-less future was, for a vast majority, momentarily exhilarating. Yet that future didn���t come. Instead, Mugabe���s legacy of intolerance and violence, that had defined The Party from the outset, continued to dominate its trajectory, even in the face of his demise.

Now with Mugabe���s death, some might wonder if at last there might be space for a new self-definition as a nation, as a broad family of nationals, with a shared national project. Sadly, this seems doubtful. With current President Mnangagwa���s public reverence for his predecessor, who was his mentor and protector for decades���despite being the man who deposed him���we are still refused the kind of closure of a Mugabe-dominated era we had so long hoped for.

September 5, 2019

Nativism and narrow nationalism in South African politics

Hillbrow. Image credit Matthew Stevens via Flickr (CC).

With a history riddled with racial and gender oppression, economic inequality and ethnic disputes, contemporary South Africa is facing mounting and legitimate pressures to resolve profound social challenges. Multiple organizations and political groups have joined the quest to tackle racism, patriarchy, poverty, and inequality. What unites these groups is the desire to be a voice for the historically disadvantaged, and to build an African nationalism.

How to build such a nationalism, in the context of South Africa, has historically been called the ���National Question,��� the question of who belongs in South Africa. Currently, equality, and equity is merely an aspiration as the country is one of the most unequal societies in the world. In addition, socio-economic and institutional discrimination continues to undermine the full development of the black majority. South African political groups are rightfully aligned in their pursuit for complete socio-economic and political liberation for the historically disadvantaged, however, the way some of these groups have chosen to respond to these challenges is problematic. They mostly dwell on racial and ethnic mobilization centered on fear and intolerance for different ethnicities, religions, and racial groups.

Nativism and nationalism can be found to be problematic in contemporary South African politics. Fairchance Ncube, a columnist with News24, asserts that there is a propensity among some nationalists and Afro-radicals���which in this instance would be the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and Black First Land First (BLF) among others������to appeal to narratives of nativism and indigeneity as the indispensable basis for certain entitlements (particularly the land and its natural resources).��� Considering the exclusionary and oppressive history of colonization and apartheid, some of the claims lodged by these groups are justified, particularly considering the inherited inequalities from those governments and the present-day challenge to eradicate them.

Achille Mbembe uses the analogy of Nongqwase, the 16 year-old Xhosa girl who in 1854 prophesied to the Xhosa people, via her uncle, to kill all their cattle en masse to combat the deprivation suffered under British colonialism. The prophecy was that the Xhosa ancestral spirit would subsequently resurrect and sweep away the white colonizers to the sea. None of this happened and:

…by May 1857, 400,000 cattle had been slaughtered and 40,000 Xhosa had died of starvation. At least another 40,000 had left their homes in search of food ��� the whole land was surrounded by the smell of death, Xhosa independence and self-rule had effectively ended.

According to Mbembe, “Nongqawuse syndrome is a populist rhetoric and a millenarian form of politics which advocates, uses and legitimizes self-destruction or national suicide, as a means of salvation.”

It is evident from contemporary politics that some political groups have dragged progressive nationalism into irredeemable disrepute for their own self-enrichment. Such discourses replicate colonial and apartheid logics based on simplistic conceptions of who belongs and who does not. These discourses do not reflect the reality of a diverse South Africa. They thus pose a threat to the realization of a non-racial, inclusive, and democratic society. This is particularly problematic for political parties which aspire to one day rule the country���such as the EFF���as ���their limited conception of the nation will, therefore, yield action and policy that does not account for the complexities and nuances inherent to a culturally and racially heterogeneous society.���

In addition to black nationalism and nativism in post-apartheid South Africa, the chauvinist narrow white nationalist Afriforum has emerged as a conservative Afrikaner group. Afriforum is concerned with protecting the interest of white Afrikaners. Afriforum has constantly opposed the redistribution of land among all South Africans and this shows that their narrow nationalism emerged to protect white minority interests at the expense of the majority of South Africans.

In the transition to democracy, the ANC was committed to the ideals of inclusion and non-racialism. However, it is becoming trendy to constantly attack white people regardless of their class position and ideological orientation in the spirit of nativism and narrow nationalism. This does not mean certain attacks on white racists and organizations such as Afriforum are not justified. These organizations are gatekeepers of white privilege and are resistant to measures that would improve the socio-economic conditions of black people, such as expropriation of land without compensation. The likes of Afriforum feed into the frustrations and sometimes the hatred of white people, especially considering the white population���s historical and contemporary privilege.

Parties such the EFF and BLF exploit strands of nativism and use the above frustrations over the slow wheels of justice���under the ANC���to advance narrow nationalism and stoke racial tensions. The use of people���s genuine struggles to advance populist agendas and to score political points misleads the public into getting stuck on differences and current problems rather than focusing on developing and practically implementing sustainable solutions to improve the conditions of black people in the country.

Examples of populism and racial nationalism by these political parties can be found on social media. It is reflected in BLF���s president Andile Mngxitama���s encouragement for supporters to kill five white people for every black person killed. Mngxitama went as far as threatening to take South Africa to the dark ages of apartheid. Jesse Duarte, the ANC���s deputy secretary-general, asserts that racial nationalism is poisonous as it rejects non-racialism and national reconciliation. Ncube contends that this is troublesome because:

There is a certain degenerated strand of nativism that is nothing but an embodiment of racism and narrow social chauvinism of the highest caliber that can hardly be associated with the ideals espoused [sic] some of South Africa���s most celebrated bulwarks of the anti-apartheid struggle.

What the country needs is leadership that is targeted at resolving racial and structural tensions and inequalities that feed racism and narrow nationalism. This would require finding creative strategies to engage all stakeholders to create an equal society where there is an equal distribution of resources.

One of the most devastating implications of nativist nationalism is xenophobia. Presently in South Africa, in areas such as KwaZulu-Natal, there are heart-breaking attacks on African foreign nationals. Such attacks have been taking place since the realization of the democratic dispensation, with government struggling to discover the root cause of these attacks and how to mitigate them. Claude Ake (1996) cited in Norbert Kersting���s 2009 article, describes this wave of nativism as a ���second��� or ���new nationalism.��� Claude Ake (1996) describes this ���new nationalism��� as ���a rule, no longer directed toward other countries but against denizens (non-citizens) living within an African state.��� The pitfalls of such a nationalism is that it alienates itself from inclusiveness founded in the decolonization process and promotes exclusivity among Africans.

Socio-economic inequality is a contributing factor to the mounting resentment and attacks against African foreign nationals. The way in which foreign nationals are spoken about by organizations and political leaders breeds contempt and perpetuates xenophobic attitudes. For instance, the EFF has been vocal about dismantling borders and creating an African community, yet at the same time, in their 2019 manifesto the language used to speak about foreign nationals is one of criminality and distrust. The Democratic Alliance (DA) is no better than the EFF, with the Johannesburg mayor Herman Mashaba (from the DA) spewing harmful comments about foreign nationals in South Africa.

Additionally, a meeting in April 2019 between the ANC���s international relations minister Lindiwe Sisulu��and president Cyril Ramaphosa confirmed the ruling party believed that the problem of xenophobia was a problem of criminality. This simplistic conception of xenophobia is problematic as it erases accountability from political leaders and does not adequately deal with the threat that the discourses of nativism, Afrophobia, and narrow nationalism pose to our country today.

The recognition of traditional authorities and land redistribution powers granted to them in the democratic dispensation is one of the cruelest versions of nativist nationalism. It undermines the political freedom of people residing in the countryside and women. Mahmood Mamdani shows that under the colonial and apartheid states, South Africa was divided into two dimensions of bifurcated states���direct and indirect rule. Indirect rule was presided over by traditional authority. To enforce ethnic pluralism, urban and rural divisions, the colonial and apartheid governments decentralized their powers, using traditional leaders as instruments for control over Black people. These governments collaborated with traditional authorities as they recognized the strength of indigenous rulers in socially organizing black people.

What the role of traditional authorities in a democratic state should be, has been disputed. Arguments in favor of the preservation of these structures claim that they form part of African culture and identity that predates colonization. The opposition contends that traditional authorities infringe on the rights of people living in rural areas and that they have historically acted as extended authoritarian structures, which assisted in the oppression of black people under the colonial and apartheid governments.

The EFF, in its 2019 manifesto, showed great favor towards the continued existence of traditional authorities. One of us has argued that:

The EFF misses the point. Today���s organized traditional authorities are the culmination of colonization and of apartheid history. Historically, traditional leaders in Africa were not attached to the ownership of the land, unlike in Europe, because the land was abundant and did not broadcast their power to their subjects.

The EFF���s stance on traditional authorities feeds into the gender-based violence and inequality in land ownership experienced by women. Women���s access to land and tenure security are compromised by predominately two factors; firstly, due to the legacy of racially driven land dispossession, and secondly because of gender discriminatory customary law and patriarchal interpretations of culture. This places women in rural areas in a unique intersection between the law and traditional practices. This means that women in rural areas do not enjoy the same rights as men in rural areas and people in urban spaces.

Women���s inability to access land puts them in precarious socio-economic positions where they are subject to exploitation. Women often remain in violent relationships because of poverty and unequal power relations to their male counterparts who own land. In these positions, women have little to no power to mitigate their social and material security. However, ownership of land would enable women to enjoy the economic liberties and political independence.

However, women in rural areas often can only access land through their relationships with men���husband, son, father, uncle, etc. Single women cannot be allocated land and are often unable to inherit after their parents die.�� Like widows after the partner dies, they are evicted from their homes. This means that women are obliged to take the men in their lives���sons, uncles, fathers, etc���as their representatives when going to talk to traditional leaders concerning important decisions about land rights. Women are not allowed to represent themselves in front of these structures concerning land. This means that women are excluded from key decisions taken about land rights. Even when women are included in these conversations, traditional courts are usually dominated by men who overshadow and undermine women. Subsequently, women often do not receive impartial assistance in land disputes.

Therefore, if the EFF was committed to the liberation of black people it would be supporting the abolishment of traditional authorities instead of advancing nativist nationalism that subjects the very same people the party wants economic freedom for to hereditary, unaccountable, and authoritative structures. It is questionable whether strategies to protect women by challenging discriminatory laws and abolishing patriarchal customary customs can be developed by organizations and political parties that advance strands of nativism that empowers elements of sexism, tribalism, and patriarchy. Ncube affirms this by arguing that ���this strand of nativism is not only a threat to ideals of gender parity that are expected of any democracy, but they also thwart any meaningful attempt to land (re)distribution.���

For the realization of equality and equity in a non-racial, inclusive society, it is critical that South Africans remain vigilant and critical to ensure that no claim goes unchecked, or is above criticism, whether that claim comes from the mouth of a colonial or African descendant. These include philosophies and actions taken in the name of nativism and nationalism framed to be for the improvement of the material conditions of Black people. This is significant, because unchecked ideologies of nativism and nationalism can be exploited to preserve oppressive structures such as traditional authorities whilst also advancing populism, racialism, and patriarchy.

Last of all, it is pivotal to note that this piece merely seeks to advance a more inclusive conception of who belongs. It also seeks to advocate for a united, democratic, non-sexist, non-racial, and prosperous society. This piece also does not undermine the struggles and realities of the black majority and is therefore in full support of a radicalism that challenges white oppression and racism and all forms of inequality in our society.

This is an edited version of a piece first published in New Agenda, a journal of the Institute for African Alternatives.

A trap nomad finds a home

Hibotep and Houdini at Nyege Nyege. Image credit Zahara Abdul.

Hibotep, otherwise known by her birth name Hibo Elmi, or the alter ego Trap Priestess, is of Somali ancestry. Born and raised in Ethiopia, she currently lives in Kampala, Uganda, where she moved to reconnect with her twin sister, Hoden, also a DJ who goes by the name Houdini. Hibotep, like many other immigrants in Kampala, first came for a visit, then never left. She says that she feels more at home in Uganda than in Ethiopia, where she grew up cluttered in between Somalis and Ethiopians, and the everyday disputes between the two groups. ���Coming to a place where everybody is calling you sister made me feel at home. And later on our mom passed away in Kampala, so now it has become a motherland.”

These nomadic beginnings have shaped her creative processes. When Hibotep deejays, she can delve deep into everything from American trap, South African gqom, and German dub techno to Kenyan taraab and Moroccan gnawa, in one set. Her style is not based on any one genre. Instead, she���s confusing the audience with different styles, and songs with different BPMs. One song is destined to be completely different from the next. An an interview I had with Hibotep she explained:

I���m listening to music 24 hours a day, even when I���m sleeping���the music is playing… If you are passionate about something; you study it, you learn it and in the end you breathe it. Most DJs don���t challenge themselves. They play only one genre���it all sounds the same. When I deejay, I don���t want to play the best song everybody heard, I want to bring in something new, and I want the audience to say: where did you find this? I like to surprise myself as much as the audience. I���m like a different person every time I���m DJ���ing. So when the Trap Priestess is playing it���s rap music and trap, and when Hibotep is on, it���s African and electronic music.

With such a cosmopolitan outlook, Hibotep has found a creative home in Kampala with��Nyege Nyege Tapes, a label that is increasingly embraced for its vernacular electronic music���popular and folk music styles merged with electronica from the wider East African region.��Founded by two immigrants to Uganda, Greek-Armenian Arlen Dilsizian and Belgian Derek Debru, their background as internationally connected outsiders has helped establish a left-field international electronic music hub in East Africa.��For Hibotep and her twin sister, two cosmopolitans who��end up as outcasts in their own community���finding such a welcoming creative space was an affirmation for their nomadic life experiences.

Nyege Nyege’s most important platform is the Nyege Nyege Festival, situated on the banks of the source of The Nile River (its latest edition kicks off today and goes through the weekend). The festival is part of the reason why Kampala has become an epicenter of a movement showcasing electronic music from East Africa. Their international bookings show that they are by no means limited to East Africa, but that they are always searching to put bigger acts in new spaces.

The popular music of the day across Uganda includes Ugandan dancehall (which includes the internationally recognized Bobi Wine), West African Afrobeats, and Afro house. Nyege Nyege is more about cosmopolitan culture than Bobi Wine’s grassroots movement, but their activities are no less polemic, especially since Nyege Nyege events have become a haven for gender non-conforming communities. Last year, Uganda���s minister of ethics and integrity, Father Simon Lokodo, tried to shut down the festival around the same time that Bobi Wine fled the country after an assassination attempt on his life. Both events felt closely related. In a country like Uganda, just being free and ready to shake one’s ass is a political matter.

The crew involved with Nyege Nyege have been in demand within underground music scenes around the world for the last few years. Over 20 acts connected to the label are now touring worldwide, with new additions such as aspiring DJ Catu Diosis, who just had her official debut in Europe in June. One of the most important DJs in the Nyege Nyege collective, queer feminist Kampire, was one of several acts showcased at club Razzmatazz in Barcelona. Electro acholi champions Otim Alpha & Leo Palayeng and Nyege Nyege-affiliated electronic chaabi producer Gan Gah, from Morocco via Brussels also performed there.

Last year Kampire, electrified the crowd at the S��nar Festival in Barcelona. Eager to continue the process of catapulting young Nyege Nyege-affiliated acts up into the DJ stellar system, S��nar put Hibotep and Slikback on the bill for this year’s festival. The festival took place between 18th and 20th of July in Barcelona, and the two acts performed their unusual duties of connecting disparate genres from East Africa with everything from Chicago footwork to UK grime and South African gqom. Slikback, who is the most well-known producer on the Hakuna Kulala label��(a sister label equally respected for showcasing rap music in local languages, and its global minded bass music out of Kampala), was featured on year-end-lists in Pitchfork, The Quietus and Fact Magazine, and performed across Europe these last few years.

Promo image from Hibotep.

Promo image from Hibotep.Meanwhile, Hibotep has become a master in mixing old Somali- or Arabic-sounding songs over badass trap music. She���s recontextualizing old songs for new audiences. ���I like haunting, deep voices, and I���m trying to put them in the mix. It allows me to play something I really feel passionate about���and if I mix it with trap, it makes something old feel young and fresh. I���m searching for the unheard, but I also try to play something that people can relate to.��� Sometimes Hibotep even throws in Michael Jackson songs over trap, like in the Boiler Room session from last years Nyege Nyege Festival. The Trap Priestess knows no limits, but her love for trap is rooted in a knowledge that the kids are always right���no matter how despised or pushed into a corner their music is. So when Michael Jackson���s ���They Don���t Care About Us��� screams over some booming bass and grooving hi-hats, the world feels completely in the right place:

What appeals the most to me about trap is that people hate it. When rock & roll was getting started, people didn���t understand it. When hip hop started, people didn���t get it. Trap is the sound of a new generation. When I hear it without the words, the raw 808 drums, that whole sound, it makes me want to try something new.

Rap music means a lot to Hibotep, but simultaneously she is a multidisciplinary artist crafting films, fashion designs, art installations and poetry���but, she���s secretly also a rapper:�� ���I���m an undercover rapper. Usually when it���s like 3am there���s this activist that comes out of me.�����She doesn���t like to rap on stage, but sometimes she puts her own rap vocals in DJ sets. Although her ambitions as a rapper are limited, her roots in poetry stretch deep. Hibotep tells us about the Somali tradition, where all parts of life are connected to poetry:

I write poetry, my mom used to write poetry, my sister writes poetry, it���s part of our identity: Somalia is known as the land of the poets. When your grandmother or auntie are talking to you, they���re talking in riddles���it���s poems. They have poems for everything, and every life experience has a poem. Somali poetry is really hard to write, especially when it comes to making rhymes, because so few words in the language are alike at the end.

Hibotep will perform at the Nyege Nyege Festival by the source of the Nile River, between the 5th and 8th of September 2019.

September 3, 2019

Getting the story right

Mobile phone user in Cameroon. Image credit Carsten ten Brink via Flickr (CC).

To vaguely ask what the biggest development has been on the African continent this past year would most likely be meaningless. Unless, if one was to follow Binyavanga Wainaina���s eloquently satirical argument on effectively writing about the continent: treat it as if it were a country; keep the stories “simple” and entirely episodic and be confident with sweeping generalizations. It is the strategy of domination, of marginalization, of dispossession; and it continues to be the way most narratives on and about Africa are being shaped. Indeed, they are not unlike Karl Marx���s depiction of the masses during the French Revolution; masses who ���are unable to assert their class interests in their own name��� [Who] cannot represent one another, [and who] must��� be represented.”

When The National Interest recently published a piece with an inquiring title ���Is Africa���s Narrative Changing?��� (co-authored by Michael O���Hanlon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, and Hannah Markey, an intern at the same think tank), one would expect the possessive to imply an African ���ownership,��� and the interrogative to allow the continent some space to independently decide the direction, the tone, the timing, the priorities in shaping its own narratives. Only, it did not. Indeed, it needed not.

The article was mainly concerned with security and political dynamics in Africa in the past year, because this year, “the big story in Africa is less about growth rates, or big changes for better or worse in conflict dynamics. Instead, the biggest story is in the realm of politics.��� Although it is nowhere close to the omnipresent negation, or the traditional negative stereotypes about the continent, it nevertheless leaves out major issues and details that are as crucial. If Africa���s narrative, or if narratives on and about Africa are changing, these issues and details warrant discussions. Unfortunately, “Is Africa’s Narrative Changing?” seems to have completely missed that point.

Consider, for instance, the glaring omission of the signing and entry into force of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)���the largest free trade area since the establishment of WTO���that aims to boost intracontinental trade, drive innovation, bring prosperity, and help fight the hard battle against extreme poverty. Such an omission is unconscionable, especially given that the article avowedly adopted a utilitarian framework by considering ���the numbers of people affected and the trends that could be created or reinforced��� to justify its choice of the ���big six��� countries to analyze.

Moreover, one would also expect the ongoing talks on reforming the African Union (AU) to make it as a big story of the year. Indeed, if one story should deserve the epithet ���African,��� the perceptible winds of change of the AU, the push to make the continental body more effective in its activities, more efficient in its spending, and more self-reliant in sourcing of its finances should have been on anyone���s shortlist. But the cut is hardly surprising; it is another reminder that writing about Africa fundamentally entails wiping out anything that does not fit into the set agenda or interests of those telling the story. Africa or African, here, is more an idea than a palpable reality.

The piece argues, for instance, that the ���trends in democracy��� are OK,��� completely ignoring the disconcerting trajectory being taken by a growing number of countries, erstwhile promising democracies, since across the continent, and more recently in West Africa, there are growing concerns about ���democratic decay.��� Benin, once lauded as West Africa���s model democracy, and Guinea, whose Alpha Conde has become a shadow of his old self, morphing from ���democratic savior��� to a lethal threat to his country���s democratic aspirations, are two examples that readily come to mind. This is not necessarily a subscription to the claims of democratic recession in the region, but it is to point out that a balanced analysis of the recent political dynamics in Africa ought to consider such developments. Similarly, the silent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan warrant a passing mention, if only because of the trends that could be created or reinforced by these developments.

Also, it is intriguing that the article failed to consider the conflict in the Sahel Region, especially in Mali, as a major playing ground for both regional and continental security apparatus. For instance, the Economic Community of West Africans States (ECOWAS) warned that the Malian crisis could spill into neighboring countries and destabilize the region. More striking, however, is the article���s complacent section on DR Congo. The authors frustratingly failed to elaborate on the country���s worrying Ebola crisis. The current epidemic in DR Congo is said to be the second-biggest Ebola epidemic outbreak since that of 2014���2016. In fact, on July 17, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a global health emergency, and the assessments mentioned fears that it might spread into neighboring Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan. These concerns were echoed by the UNSC, which observed that ���the disease could spread rapidly, including to neighboring countries, possibly having serious humanitarian consequences and impacting regional stability.���

Thus, rather than simply wondering if Africa���s narrative has changed, perhaps the real questions should be: how are narratives on and about Africa changing? Could there be a room for Africa to claim their ownership? And how to best do that? The task is not to replace one single story with another. Rather, as Peter da Costa eloquently argues: ���There is a need to push the boundaries, to find new ways to communicate about [developments], to represent Africa in all its complexity and contradiction������

Only then will we have in-depth and informed analyses; and only then will we offer balanced perspectives about the complex dynamics unfolding in Africa. The real challenge, in a nutshell, is to provide balanced and substantiated perspectives, rather than catchy titles with hollow contents.

September 2, 2019

Hendrik Witbooi’s Bible and the Humboldt Forum

Hendrik Witbooi with his son Isaac and German officers. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Germany boasts some of the finest museums in the world, including an array of ethnographic ones. In former times, these were deemed to cater to the curiosity of the German public to glimpse something of the lives of ostensibly ���primitive��� peoples and at the same time, to showcase the successes of German colonialism as well as the work of Christian missions operating from the country. Those peoples were presented as colourful representatives of stages of humanity German viewers felt they had long left behind. Satisfying curiosity was thus linked with bolstering feelings of superiority.

This basic approach has persisted until quite recently when museum operators increasingly saw the need to adopt a more critical, postcolonial approach. The turn was dramatized when in July 2017 eminent art historian B��n��dicte Savoy resigned from the advisory body of the Humboldt Forum, which is intended to present the ethnographic collections of the former Prussian state in the reconstruction castle of the Hohenzollern in central Berlin. Savoy���s intervention, when she graphically called for knowledge about ���how much blood is dripping from a work of art��� helped to propel the issue of the provenance of museum holdings centre stage.

In late 2018, Savoy, along with Senegalese philosopher Felwine Sarr published a celebrated policy paper to guide sweeping restitutions of African cultural heritage objects from French museums and to give substance to French President Emmanuel Macron���s foray of late 2017 when he made ���the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Africa��� his priority. Not accidentally, when the new German federal government was formed in March 2018, federal state minister of cultural affairs Monika Gr��tters declared provenance research into ���colonial heritage in collections and museums��� a priority comparable to efforts towards dealing with Nazi robberies of art. Meanwhile, much of the euphoria has evaporated in the face of the sad state of museums and their collections as well as their lack of staff and funding. Actual restitution, which hinges on the clarification of provenance remains limited to singular cases.

It has become clear that restitution is not a simple matter. Savoy has quipped that after wholesale return of the collections, the Humboldt Forum in Berlin might be stocked by fake (copied) objects in a fake castle. This may be an attractive proposition, but there are also serious problems. Not least, these begin with the way artifacts have been treated once they entered the museums. As a result of precautions against pests and insects, most of the objects from former colonies in the care of the museums are now heavily toxic, since arsenic as well as DDT have been applied on them. Such artifacts can only be approached or handled with gloves, dust mask and protective clothing, since they emit carcinogenic micro particles. Even by that token, the evident concern inherent in restitution, to set right the injustice perpetrated against those who have been robbed, viz., their descendants, comes up against a very massive obstacle. On account of this, most of the artifacts can only be returned to their country of origin, at best for safekeeping by appropriate institutions. Sadly, even given the best of intentions, colonial injustice cannot simply be undone in a postcolonial situation. The postcolonial situation remains marked by what colonialism has perpetrated.

Such issues came to the fore when in late February 2019, the first actual restitution from Germany to Namibia was carried out. This concerned the bible and riding whip of the legendary Hendrik Witbooi, today one of Namibia���s national heroes. Both objects had been taken as booty by the German military during a raid on Witbooi���s settlement in 1893. After a long process of negotiation, The Linden Museum in Stuttgart, which had held the artifacts since 1902, along with the State Ministry of Science and Culture of Baden-W��rttemberg pioneered this restitution. Shortly before the envisaged date, obstacles emerged on account of competing claims by the Namibian state on the one hand and the Witbooi community on the other. The Namibian government claimed ownership on account of Hendrik Witbooi���s status as a national hero, whereas his descendants insisted that the bible and the whip were family heirlooms and Namibia had not existed as a territory at the time of the raid in 1893. A working accord was eventually reached, and the return ceremony went ahead at the Witbooi traditional capital of Gibeon in southern Namibia.

Still, the incident demonstrated that the effects of colonialism cannot be undone by independence���postcolonial states, as modern states, are the heirs of colonial ones. They are under heavy constraints to act as such, also in their self-interest. From a German perspective however, such issues and considerations must not divert from the central demand of restitution. For German institutions, restitution, if requested, is the main avenue for setting things right���as far as this may be possible today. In this sense, Felwine Sarr has made the basic point that the responsibility to restitute applies regardless of what will happen to artifacts thereafter. This is not for the colonizers or their successors to decide.

However, it would be a mistake to take this as a release from responsibility. In erstwhile colonial metropoles, the colonial past must not be erased by sweeping colonially acquired artifacts out of museums and collections. It is here that diligent provenance research remains a responsibility, both in order to know from where objects have been taken, and to live up to accountability. Generally, such work is much more complex than in the case of the Witbooi bible and whip, or the Benin bronzes, where circumstances of colonial violence and theft are well known.

At the same time, museums can and should be turned into sites of educating the public not only about the richness of human existence and activity, but inextricably linked to this by the provenance of the objects exhibited and their colonial origins. In Germany, some forays have been made. Even there, accounts of provenance as one basic requirement remain scanty in the exhibitions. The Humboldt Forum, officially advertised as a venue to showcase Germany���s opening to the world, will still have to measure up to such requirements.

September 1, 2019

The Coloured Gangster

John W. Fredericks. Image credit Penguin Random House.

The gangster, especially the coloured (���mixed race���) gangster, is a loaded cipher in South Africa. He is, simultaneously, a figure of panic, an outsider, loser, avatar of moral decline, byproduct of apartheid���s negative effects, defiant outlaw, and, more recently, a reflection of the deep, systematic failures of the twin promises of postapartheid and capitalist society, as well as a neoliberal entrepreneur. The gangster has baffled academics, mostly sociologists and historians, tabloid journalists, and filmmakers alike.

The new film, Noem My Skollie (in English, Call Me Gangster, or Thief), released in 2016, explores some of these themes. Noem My Skollie (NMS) is set in 1960s Cape Town, and the action moves over a ten-year period between Kewtown, a section of Athlone township, and Pollsmoor prison, an infamous institution on the southern edge of the Table Mountain next to a white suburb and vineyards. The protagonist, Abraham, or AB, is molested as a teenager, forms a gang to take revenge on his attacker, gets arrested for a robbery, along with a close friend, Gimba, and is sent to Pollsmoor. Inside the prison, AB encounters ���the Number,��� which is how the country���s prison gangs collectively are known. It comprises the 28, 27, and 26 gangs. There, to fend off the 28s (a gang that uses sodomy as a means of power within the gang), AB presents himself to cellmates as a storyteller���becoming the ���prison cinema������and as a letter writer. The plan works; Gimba is not so lucky. On AB���s release, he starts a new life as a writer and finds love, only to be framed for another murder, which builds to the film���s dramatic denouement.

The gang history recounted in NMS has deep roots in South African history and culture. The Number includes the most violent and also the most mythologized gangs. Gang history is also as old as modern South Africa. The Number traces its origins to the discovery of gold in the 1880s in the Witwatersrand region, specifically, to a band of black men, led by a Zulu migrant, who robbed and killed colonists and whites and who extorted black migrant workers. By the middle of the twentieth century, the Number���which developed its own lexicon, a polyglot of South African languages, as well as a complex rank structure of order and punishment mimicking colonial and Afrikaner armies of the Boer War���had grown to dominate South African prisoners. Outside prisons, and in the wake of large-scale urbanization of blacks, were turf gangs, drawing inspiration from American crime films, and formed from the social disaffection of young men. They mostly preyed on their fellows. Drum magazine���s black writers in the 1950s���the South African equivalent of the Harlem Renaissance���covered the exploits of these gangs in detail in the black, coloured, and Indian parts of the cities of Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban. The gangs even developed a certain kind of glamor. They included the Gestapos, the Vultures, the Berliners, and the Americans. After a while, some gangsters turned to the word, as did the poet Don Mattera, of Italian and Tswana descent, who would go on to write about his gang exploits in inner-city Johannesburg.

But it would be in Cape Town that gangs would come to dominate social and economic life for the city���s mostly coloured working class. More than criminal in general, the city has hundreds of thousands of organized gang members and boasts the country���s highest murder rate as a result. Much of this violence is contained on the Cape Flats, the vast, inhospitable floodplain beyond the central city to which, in places like Manenberg, Kewtown, and Hanover Park, its mostly coloured population had been resettled. More recently, some of the violence has spread to the city���s mostly white suburbs.

Gangs thrived in Cape Town���s creolized suburbs, such as District Six, Kirstenbosch, Newlands, and Claremont, on the edges of Table Mountain, in the first half of the twentieth century, before these neighborhoods were ���sanitized��� by apartheid for whites after 1948. The Mongrels, a notorious Cape Flats gang, had their start in District Six. Though the Mongrels were certainly violent, older Capetonians remember these gangs fondly, noting that they became particularly violent after forced removals to the Cape Flats. By the 1970s, newer gangs, like the Hard Livings (HLs) and the Cape Town version of the Americans, made their presence felt on the Flats. (One curiosity is gangs��� insignia: the HLs swear to the British flag). Apartheid police were notorious for cooperating with coloured gangs, spying on activists and on occasion soliciting them for political hits.

Gangsters were always a staple onscreen, even under apartheid. In films like the liberal, Hollywood-infused Cry, the Beloved Country (1951), Absalom, the gangster brother of the lead, was used to moralize. In the more radical Come Back Africa (1959), the sociological and historical causes of gangsterism come through. These were films set in Johannesburg, so the gangsters were black. (Coloured gangsters still served as a comedic device in musical revue films like Zonk! [(1950]). It is, however, Mapantsula (1988), with its exploration of the short life of Panic, a gangster pulled between loyalty to his police handlers and growing admiration for activists in late 1980s Soweto at the height of the last phase of anti-apartheid resistance, that has stood as the most complex portrayal of a gangster up to that point and since. The film was a joint project of white director Oliver Schmitz and black writer/lead actor Thomas Mogotlane. (Even the exiled ���cultural desk��� of the African National Congress [ANC] felt compelled to debate the film in its journals. They could not agree on its cultural merit.)

Nelson Mandela���s release and the negotiations between the ANC and the apartheid state opened up further portrayals of gangster life on film. Artists were now comfortable tackling subjects other than exile and struggle. Cape of Fear, a 1994 documentary film by British director Daniel Reed about two coloured HLs, the twins Rashied and Rashaad Staggie, and their violent rule of Manenberg, should receive partial credit for the torrent of postapartheid interest in cinematic depictions of coloured gang life (including on television). The film not only focused on the Staggies but also gave a wider sense of the structural effects of apartheid on coloureds���the destitution, cramped housing, high unemployment, sexual violence���and the role of religion, especially Christianity, as redemptive ideology in the community. The film provided an unabashed glimpse into the daily struggles of gang life. Cape of Fear achieved cult status. The film was screened on a local cable channel, but those who did not have a subscription passed around bootlegged VHS copies in neighborhoods and workplaces in Cape Town (which is how I, too, came into possession of it, via my sister, who worked at a shoe factory in Cape Town). The Staggies would later be the target of the anti-crime group PAGAD (People Against Gangsterism and Drugs) whose members burned Rashaad alive and then shot him to death in front of his house. Cape of Fear suggested, more than anything, that gang life on the Cape Flats was a subject worthy of serious exploration. By the early 2000s, coloured gangsters were sensationalist tabloid fare (gruesome and gleeful stories of gang assassinations and the high life) in the local press. They had also quietly and strategically taken control of extortion rackets and were now in open warfare with older, more established crime syndicates, who extracted protection money from the lucrative restaurant and nightlife in Cape Town���s city center.

Meanwhile, feature films like Hijack Stories (2000), Tsotsi (2005), which won an Oscar, and Gangster���s Paradise: Jerusalema (2008) covered aspects of gang life in Johannesburg. All three films were directed by white directors. Tsotsi, for all its significance, individualized crime and reflected white liberal politics about the end of apartheid; Gangster���s Paradise: Jerusalema came across as a South African knock-off of Carlito���s Way (1993). But these were more morality tales about crime, and their political message appeared forced. (A documentary film that went under the radar was late photographer Peter McKenzie and French codirector Sylvie Peyre���s film What Kind … ? [2007], in which McKenzie returns to his childhood home, Wentworth, a coloured township in Durban, to interview his now middle-aged childhood friends years after they were released from prison over a mid-1980s gang killing).

In 2013, the filmmaker Ian Gabriel (he had also made a film about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Forgiveness [2004]) directed the film Four Corners (2013), the story about a chess prodigy and his family connections to the 26s and 28s. The film received mixed reviews, mostly for adding very little to themes already explored in films such as the Brazilian film City of God (2002) and the 1994 American film, Fresh. Since the release of Four Corners, depictions of South African gang and prison lives seem to be everywhere in local (and international) media���in short films, documentaries, books, photography, and so forth. It would not be a harsh judgment to argue that only two other pieces of media have since come close to the honesty and empathy of Cape of Fear: the documentary film The Devil���s Lair (2013) by Riaan Hendricks, about his high school friend turned gang leader in Mitchells Plain, Braaim; and the journalist Rehana Rossouw���s novel What Will People Say (2015), set in working class Hanover Park.

NMS has some familiar elements and is not a bad film, though some critics may fault it for being overly sentimental. If it seems that way, it may be because much of it is real life. The script for NMS was written by John W. Fredericks, a seventy-year-old former security guard, who lives on the Flats and has for years written plays to be performed in community halls around the city. The film is based on his life. Fredericks has also made documentary films���most notably, one about a local rapper, Devious, who was fatally stabbed by a gang in Mitchells Plain in 2004.

Despite its familiar elements, Noem My Skollie attempts to break with the gangster film genre. As one of the executive producers, Moshidi Motshegwa (she starred in Hijack Stories), put it to a journalist: Noem My Skollie is not about ���the Number.��� Its makers want to avoid the sensationalism attached to ���the Number��� and instead to explore human drama. The producers picked a young, coloured director, Daryne Joshua. It was Joshua���s first film. The art direction, which painstakingly tries to recreate 1960s Cape Town, was the responsibility of another coloured artist, Warren Gray. And Kyle Shepherd, a young Cape Town jazz pianist often favorably compared to Abdullah Ibrahim wrote the film score. Like Cape of Fear, Noem My Skollie was well received by the audiences Fredericks had in mind. The film played in prisons, in schools, and in community halls before its release in local commercial cinemas. One of the actors who played the leader of the 28s in prison had to fend off members of the 28s who attacked him on the street, mistaking acting for real life (James de Villiers, ������I Don���t Know if It Was 28s or Drunk People��� Assaulted Noem My Skollie��Actor,��� News24, December 14, 2016). The film was also submitted as the South African entry for Best Foreign Language Film to the 2017 Academy Awards, although it was not nominated in the end.

Noem My Skollie is not a perfect film, and its critics may easily point to some of its shortcomings, but that should not be the focus of critiques or debates about import. It has more value as a piece of South African cinema history and for what it says about film production in postapartheid South Africa. The film is a production of Maxi-D TV Productions in association with cable network M-Net, cable channel kykNET, the National Film and Video Foundation (NFVF) and the government Department of Trade and Industry. One of the production companies, kykNET, has been accused of trafficking in white nostalgia for colonialism and apartheid, so its decision to support NMS is seen as a way to counter that perception. The dialogue is mostly in Afrikaans and brings to the center the voices and experiences of the bulk of Afrikaans speakers, that is, coloured Afrikaans speakers, but Noem My Skollie stands out for how it depicts a real social and political problem in working-class communities on the Cape Flats: the gangs are real, so is that social world, and so are gangs��� effects on people lives. Gangsters from the Cape Flats are rarely humanized, their histories worthy of being accounted on film. Noem My Skollie, for better or worse as a work of fiction, begins that process.

This post first appeared as a review in��The American Historical Review��(2018) 123 (2): 534-536, doi: 10.1093/ahr/rhy006. It is reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association. Please visit.

This figure is not included under the Creative Commons license of this website. For permissions, please email:��journals.permissions@oup.com

John W. Fredericks, 1946-2019

John W. Fredericks. Image credit Penguin Random House.

The gangster, especially the coloured (���mixed race���) gangster, is a loaded cipher in South Africa. He is, simultaneously, a figure of panic, an outsider, loser, avatar of moral decline, byproduct of apartheid���s negative effects, defiant outlaw, and, more recently, a reflection of the deep, systematic failures of the twin promises of postapartheid and capitalist society, as well as a neoliberal entrepreneur. The gangster has baffled academics, mostly sociologists and historians, tabloid journalists, and filmmakers alike.

The new film, Noem My Skollie (in English, Call Me Gangster, or Thief), released in 2016, explores some of these themes. Noem My Skollie (NMS) is set in 1960s Cape Town, and the action moves over a ten-year period between Kewtown, a section of Athlone township, and Pollsmoor prison, an infamous institution on the southern edge of the Table Mountain next to a white suburb and vineyards. The protagonist, Abraham, or AB, is molested as a teenager, forms a gang to take revenge on his attacker, gets arrested for a robbery, along with a close friend, Gimba, and is sent to Pollsmoor. Inside the prison, AB encounters ���the Number,��� which is how the country���s prison gangs collectively are known. It comprises the 28, 27, and 26 gangs. There, to fend off the 28s (a gang that uses sodomy as a means of power within the gang), AB presents himself to cellmates as a storyteller���becoming the ���prison cinema������and as a letter writer. The plan works; Gimba is not so lucky. On AB���s release, he starts a new life as a writer and finds love, only to be framed for another murder, which builds to the film���s dramatic denouement.

The gang history recounted in NMS has deep roots in South African history and culture. The Number includes the most violent and also the most mythologized gangs. Gang history is also as old as modern South Africa. The Number traces its origins to the discovery of gold in the 1880s in the Witwatersrand region, specifically, to a band of black men, led by a Zulu migrant, who robbed and killed colonists and whites and who extorted black migrant workers. By the middle of the twentieth century, the Number���which developed its own lexicon, a polyglot of South African languages, as well as a complex rank structure of order and punishment mimicking colonial and Afrikaner armies of the Boer War���had grown to dominate South African prisoners. Outside prisons, and in the wake of large-scale urbanization of blacks, were turf gangs, drawing inspiration from American crime films, and formed from the social disaffection of young men. They mostly preyed on their fellows. Drum magazine���s black writers in the 1950s���the South African equivalent of the Harlem Renaissance���covered the exploits of these gangs in detail in the black, coloured, and Indian parts of the cities of Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban. The gangs even developed a certain kind of glamor. They included the Gestapos, the Vultures, the Berliners, and the Americans. After a while, some gangsters turned to the word, as did the poet Don Mattera, of Italian and Tswana descent, who would go on to write about his gang exploits in inner-city Johannesburg.

But it would be in Cape Town that gangs would come to dominate social and economic life for the city���s mostly coloured working class. More than criminal in general, the city has hundreds of thousands of organized gang members and boasts the country���s highest murder rate as a result. Much of this violence is contained on the Cape Flats, the vast, inhospitable floodplain beyond the central city to which, in places like Manenberg, Kewtown, and Hanover Park, its mostly coloured population had been resettled. More recently, some of the violence has spread to the city���s mostly white suburbs.

Gangs thrived in Cape Town���s creolized suburbs, such as District Six, Kirstenbosch, Newlands, and Claremont, on the edges of Table Mountain, in the first half of the twentieth century, before these neighborhoods were ���sanitized��� by apartheid for whites after 1948. The Mongrels, a notorious Cape Flats gang, had their start in District Six. Though the Mongrels were certainly violent, older Capetonians remember these gangs fondly, noting that they became particularly violent after forced removals to the Cape Flats. By the 1970s, newer gangs, like the Hard Livings (HLs) and the Cape Town version of the Americans, made their presence felt on the Flats. (One curiosity is gangs��� insignia: the HLs swear to the British flag). Apartheid police were notorious for cooperating with coloured gangs, spying on activists and on occasion soliciting them for political hits.

Gangsters were always a staple onscreen, even under apartheid. In films like the liberal, Hollywood-infused Cry, the Beloved Country (1951), Absalom, the gangster brother of the lead, was used to moralize. In the more radical Come Back Africa (1959), the sociological and historical causes of gangsterism come through. These were films set in Johannesburg, so the gangsters were black. (Coloured gangsters still served as a comedic device in musical revue films like Zonk! [(1950]). It is, however, Mapantsula (1988), with its exploration of the short life of Panic, a gangster pulled between loyalty to his police handlers and growing admiration for activists in late 1980s Soweto at the height of the last phase of anti-apartheid resistance, that has stood as the most complex portrayal of a gangster up to that point and since. The film was a joint project of white director Oliver Schmitz and black writer/lead actor Thomas Mogotlane. (Even the exiled ���cultural desk��� of the African National Congress [ANC] felt compelled to debate the film in its journals. They could not agree on its cultural merit.)

Nelson Mandela���s release and the negotiations between the ANC and the apartheid state opened up further portrayals of gangster life on film. Artists were now comfortable tackling subjects other than exile and struggle. Cape of Fear, a 1994 documentary film by British director Daniel Reed about two coloured HLs, the twins Rashied and Rashaad Staggie, and their violent rule of Manenberg, should receive partial credit for the torrent of postapartheid interest in cinematic depictions of coloured gang life (including on television). The film not only focused on the Staggies but also gave a wider sense of the structural effects of apartheid on coloureds���the destitution, cramped housing, high unemployment, sexual violence���and the role of religion, especially Christianity, as redemptive ideology in the community. The film provided an unabashed glimpse into the daily struggles of gang life. Cape of Fear achieved cult status. The film was screened on a local cable channel, but those who did not have a subscription passed around bootlegged VHS copies in neighborhoods and workplaces in Cape Town (which is how I, too, came into possession of it, via my sister, who worked at a shoe factory in Cape Town). The Staggies would later be the target of the anti-crime group PAGAD (People Against Gangsterism and Drugs) whose members burned Rashaad alive and then shot him to death in front of his house. Cape of Fear suggested, more than anything, that gang life on the Cape Flats was a subject worthy of serious exploration. By the early 2000s, coloured gangsters were sensationalist tabloid fare (gruesome and gleeful stories of gang assassinations and the high life) in the local press. They had also quietly and strategically taken control of extortion rackets and were now in open warfare with older, more established crime syndicates who extracted protection money from the lucrative restaurant and nightlife in Cape Town���s city center.

Meanwhile, feature films like Hijack Stories (2000), Tsotsi (2005), which won an Oscar, and Gangster���s Paradise: Jerusalema (2008) covered aspects of gang life in Johannesburg. All three films were directed by white directors. Tsotsi, for all its significance, individualized crime and reflected white liberal politics about the end of apartheid; Gangster���s Paradise: Jerusalema came across as a South African knock-off of Carlito���s Way (1993). But these were more morality tales about crime, and their political message appeared forced. (A documentary film that went under the radar was late photographer Peter McKenzie and French codirector Sylvie Peyre���s film What Kind … ? [2007], in which McKenzie returns to his childhood home, Wentworth, a coloured township in Durban, to interview his now middle-aged childhood friends years after they were released from prison over a mid-1980s gang killing).

In 2013, the filmmaker Ian Gabriel (he had also made a film about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Forgiveness [2004]) directed the film Four Corners (2013), the story about a chess prodigy and his family connections to the 26s and 28s. The film received mixed reviews, mostly for adding very little to themes already explored in films such as the Brazilian film City of God (2002) and the 1994 American film, Fresh. Since the release of Four Corners, depictions of South African gang and prison lives seem to be everywhere in local (and international) media���in short films, documentaries, books, photography, and so forth. It would not be a harsh judgment to argue that only two other pieces of media have since come close to the honesty and empathy of Cape of Fear: the documentary film The Devil���s Lair (2013) by Riaan Hendricks, about his high school friend turned gang leader in Mitchells Plain, Braaim; and the journalist Rehana Rossouw���s novel What Will People Say (2015), set in working class Hanover Park.

NMS has some familiar elements and is not a bad film, though some critics may fault it for being overly sentimental. If it seems that way, it may be because much of it is real life. The script for NMS was written by John W. Fredericks, a seventy-year-old former security guard, who lives on the Flats and has for years written plays to be performed in community halls around the city. The film is based on his life. Fredericks has also made documentary films���most notably, one about a local rapper, Devious, who was fatally stabbed by a gang in Mitchells Plain in 2004.

Despite its familiar elements, Noem My Skollie attempts to break with the gangster film genre. As one of the executive producers, Moshidi Motshegwa (she starred in Hijack Stories), put it to a journalist: Noem My Skollie is not about ���the Number.��� Its makers want to avoid the sensationalism attached to ���the Number��� and instead to explore human drama. The producers picked a young, coloured director, Daryne Joshua. It was Joshua���s first film. The art direction, which painstakingly tries to recreate 1960s Cape Town, was the responsibility of another coloured artist, Warren Gray. And Kyle Shepherd, a young Cape Town jazz pianist often favorably compared to Abdullah Ibrahim wrote the film score. Like Cape of Fear, Noem My Skollie was well received by the audiences Fredericks had in mind. The film played in prisons, in schools, and in community halls before its release in local commercial cinemas. One of the actors who played the leader of the 28s in prison had to fend off members of the 28s who attacked him on the street, mistaking acting for real life (James de Villiers, ������I Don���t Know if It Was 28s or Drunk People��� Assaulted Noem My Skollie��Actor,��� News24, December 14, 2016). The film was also submitted as the South African entry for Best Foreign Language Film to the 2017 Academy Awards, although it was not nominated in the end.

Noem My Skollie is not a perfect film, and its critics may easily point to some of its shortcomings, but that should not be the focus of critiques or debates about import. It has more value as a piece of South African cinema history and for what it says about film production in postapartheid South Africa. The film is a production of Maxi-D TV Productions in association with cable network M-Net, cable channel kykNET, the National Film and Video Foundation (NFVF) and the government Department of Trade and Industry. One of the production companies, kykNET, has been accused of trafficking in white nostalgia for colonialism and apartheid, so its decision to support NMS is seen as a way to counter that perception. The dialogue is mostly in Afrikaans and brings to the center the voices and experiences of the bulk of Afrikaans speakers, that is, coloured Afrikaans speakers, but Noem My Skollie stands out for how it depicts a real social and political problem in working-class communities on the Cape Flats: the gangs are real, so is that social world, and so are gangs��� effects on people lives. Gangsters from the Cape Flats are rarely humanized, their histories worthy of being accounted on film. Noem My Skollie, for better or worse as a work of fiction, begins that process.

This post first appeared as a review in��The American Historical Review��(2018) 123 (2): 534-536, doi: 10.1093/ahr/rhy006. It is reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association. Please visit.

This figure is not included under the Creative Commons license of this website. For permissions, please email:��journals.permissions@oup.com

August 28, 2019

Beyond White Jesus

Cameroon near Bamenda Bamessing. Image credit Flickr user Jbdodane (CC).

When images of a white preacher and actor going around Kenya playing Jesus turned up on social media in July 2019, people were rightly stunned by the white supremacist undertone of the images. They suggested that Africans were prone to seeing Jesus as white, promoting the white savior narrative in the process. While it is true that the idea of a white Jesus has been prevalent in African Christianity even without a white actor, and many African Christians and churches still entertain images of Jesus as white because of the missionary legacy, many others have actively promoted a vision of Jesus as brown or black both in art an in ideology.

Images of a brown or black Jesus is as old as Christianity in Africa, especially finding a prominent place in Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which has been in existence for over sixteen hundred years. Eyob Derillo, a librarian at the British Library, recently brought up a steady diet of these images on Twitter. The image of Jesus as black has also been popularized through the artistic project known as Vie de Jesus Mafa (Life of Jesus Mafa) that was conducted in Cameroon. The most radical expression of Jesus as a black person was however put forth by a young Kongolese woman called Kimpa Vita, who lived in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century. Through the missionary work of the Portuguese, Kimpa Vita, who was a nganga or medicine woman, became a Christian. She taught that Jesus and his apostles were black and were in fact born in S��o Salvador, which was the capital of the Kongo at the time. Not only was Jesus transposed from Palestine to S��o Salvador, Jerusalem, which is a holy site for Christians, was also transposed to S��o Salvador, so that S��o Salvador became a holy site. Kimpa Vita was accused of preaching heresy by Portuguese missionaries and burnt at the stake in 1706.

It was not until the 20th century that another movement similar to Vita���s emerged in the Kongo. This younger movement was led by Simon Kimbangu, a preacher who went about healing and raising the dead, portraying himself as an emissary of Jesus. His followers sometimes see him as the Holy Spirit who was to come after Jesus, as prophesied in John 14:16. Just as Kimpa Vita saw S��o Salvador as the new Jerusalem, Kimbangu���s village of Nkamba became, and still is known as, the new Jerusalem. His followers still flock there for pilgrimage. Kimbangu was accused of threatening Belgian colonial rule and thrown in jail, where he died. Some have complained that Kimbangu seems to have eclipsed Jesus in the imagination of his followers for he is said to have been resurrected from the dead, like Jesus.

Kimbangu���s status among his followers is however similar to that of some of the leaders of what has been described as African Independent Churches or African Initiated Churches (AICs). These churches include the Zionist churches of Southern Africa, among which is the amaNazaretha of Isaiah Shembe. Shembe���s followers see him as a divine figure, similar to Jesus, and rather than going to Jerusalem for pilgrimage, his followers go to the holy city of Ekuphakameni in South Africa. The Cameroonian theologian, Fabien Eboussi Boulaga, in his Christianity Without Fetish, see leaders like Kimbangu and Shembe as doing for their people in our own time what Jesus did for his people in their own time���providing means of healing and deliverance in contexts of grinding oppression. Thus, rather than replacing Jesus, as they are often accused of doing, they are making Jesus relevant to their people. For many Christians in Africa, therefore, Jesus is already brown or black. Other Christians still need to catch up with this development if we are to avoid painful spectacles like the one that took place last month in Kenya.

General Sisi’s empty seats

Egypt's players celebrate goal. Image credit Amr Abdallah Dalsh for Reuters. Uploaded to Flickr under Creative Commons license.

The 2019 African Cup of Nations (AFCON)���held in June and early July 2019���was not especially well attended, except when Egypt played. Egypt was eventually knocked out in the quarterfinals by South Africa. During semifinal matches, for crowd reactions shots, camera operators zoomed in to avoid the swathes of empty chairs. But they could not do it all the time. In wide shots, anyone watching on television could not help notice the dozens of empty seats and rows with no fans at the continent���s premier tournament. Rather than being a sign of disinterest, these empty seats were engineered by the Egyptian regime, who actively discouraged Egyptian football fans from attending.

The way they achieved this goal tells us a bit about the nature of authoritarian neoliberalism.

Why the Egyptian regime would want to restrict attendance to a sporting event held in Egypt and watched around the world is simple: the dictator Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and his reactionary retinue hate crowds. They especially hate crowds of the working class who make up the majority of Egyptian football fans, known as ultras. In the 2011 revolution, the intervention of ultras in Tahrir Square became famous.

Demonstration against Port Said massacre. Image credit Alisdare Hickson via Flickr (CC).

Demonstration against Port Said massacre. Image credit Alisdare Hickson via Flickr (CC).Many committed fans of Egyptian heavyweights Zamalek and Al Ahly put aside their legendary rivalry to provide material support to the ongoing occupation. And they brought flare-waving passion, coordinated chanting, and raucous cop fighting to the heart of pitched battles and massive demonstrations. Whatever their actual effect on a revolutionary process that drew from a much larger swathe of Egyptian civil society, it is clear that the security forces of Egypt noted and resented the role of football ultras.

The knee-jerk response to the danger of this crowd was immediate state repression and regulation. Many blame Egyptian security forces for inciting a football riot in Port Said that left 74 dead, and then using the incident to justify severely restricting fan attendance in the league. Under intense pressure, organized groups of ultras of Egyptian club teams have disbanded and major matches have been played in front of completely empty stands.

The instinct to just ban everyone could not work for an international tournament with a global viewership, however. Instead, citing some legitimate concerns about security as justification, Egyptian officials used a fan ID system to restrict and monitor who was attending the matches, while also hiking the ticket prices. Despite widespread outcry and subsequent reduction in the purchase price, tickets remained beyond the reach of the average Egyptian ultra.

Of course, football fandom extends beyond the stadiums as fans still gather in cafes, public squares, and in homes to watch matches before streaming onto city streets to celebrate. But the transformation of the stadium into a place too pricey and over-policed for the vast majority is still a loss for a working class, whose access to public space is increasingly restricted. Using the coercion of market forces to continue and extend repression to eliminate any threat or perceived threat from people coming together, is a hallmark of neoliberalism.

The African Cup of Nations might be over, but these measures and tendencies will long outlive it.

August 26, 2019

Ghana’s Rastas and the year of return

[image error]

Image credit Sam Broadway.

Twice this year, so far, the cannabis decriminalization efforts of the Rastafari Council of Ghana have been blocked by their own police. Securing injunctions through two different courts, first on May 8th and again on June 26th, the Ghana Police prevented the group from proceeding with peaceful demonstrations in favor of ushering in a cannabis economy they view as increasingly legitimate.

Coming out of their annual conference in Kumasi, the seat of the Ashanti region, the Rastafari Council decided that 2019 was the year to ramp up their advocacy of cannabis legalization. Among the topics discussed was the persistent profiling of Rastas during routine traffic stops, which led to a much larger conversation.

���One of the things that came up was that we needed to step up the advocacy for decriminalization because it is the criminalization of herb that leads to police people wanting to pick on you because they think you carry and once you’re implicated, you know, it’s either a way of extortion or something,��� said Rastafari Council President Ahuma Ocansey Bosco, better known as Daddy Bosco.

Ironically, and perhaps fortuitously, the Rasta community���s increased advocacy has coincided with what has become widely known as the Year of Return.

Speaking at the UN General Assembly in September of last year, Ghana���s president, Nana Akufo-Addo, declared that 2019, which marks the 400th anniversary of the first African slaves reaching the shores of Jamestown, Virginia, would be the year to welcome members of the African diaspora back to the country where over 70% of West Africa���s slave forts can be found.

���We know of the extraordinary achievements and contributions they [Africans in the diaspora] made to the lives of the Americans, and it is important that this symbolic year���400 years later���we commemorate their existence and their sacrifices,��� said Akufo-Addo in his speech.

While Akufo-Addo and his administration intends, through the Year of Return, to recognize the ���achievements and contributions��� of American descendants of enslaved Africans, some of Ghana���s earliest returnees, members of the Rasta community, still face discrimination and are denied, through the prevention of their right to peaceful protest, full citizenship.

Arrival of the first Rastas

���Here in Accra there’s a place they call Brazil House. That is where the first, or some of the first, returnees, who came from Brazil, lived,��� Daddy Bosco said describing the origins of Ghana���s vibrant and robust Rasta community. ���So, there is that connection to Ghana and the African diaspora, especially in the West…I remember growing up in the 70s, you know, seeing the Brethren that came from particularly the UK. So those Brethren lived in Labadi.���

Labadi is a subregion of Greater Accra where the popular Labadi Beach, which hosts weekly Reggae nights that famously last until sunrise, is located.

During our interview, Daddy Bosco, reminiscing about the early days of Rastafari culture, told me of returnees, like Zebbi Carlos, the first Rasta he encountered in his youth, and Big Dread, who lives in the Amamole Rasta Camp, also known as Ethiopian World Federation Local 24. Dread whose origins are mysteriously unclear (some said Jamaica, some Birmingham, though he himself told me he was from Ghana). It was abundantly clear from Bosco���s memories that musicians played an outsized role in the establishment and proliferation of Rasta culture in Ghana. Bosco spoke passionately about musicians of days past, such as Felix Bell, who not only recorded several hit reggae songs but also acted in a local television series, as well as a band called Classic Candles which, after the rest of their members locked their hair, changed their name to Classic Vibes. But music is not where it started and not where it ends.

Surviving the stigma

The early days of Rastafari culture in Ghana were rife with familial rejection and systemic discrimination. ���Cast your mind back 40 years, conservative Ghana���Rasta was a strange phenomenon back then,��� said Bosco. Rastas in Ghana have never had the sort of privilege of multitude like those in Jamaica enjoyed.

It wasn���t until 1983, when many of Ghana���s Rastas, along with over one million Ghanaians, returned from Nigeria, where they had emigrated as economic refugees and subsequently kicked out under the Ghana Must Go policy, to a home country in the midst of a severe famine brought on by drought.