Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 201

October 15, 2019

Neutral by nature?

The first showing of ��Converting Eviction��, May 30, 2019, at The Centre for the Less Good Idea, Johannesburg. Picture credit: Zivanai Matangi.

More than most people can imagine, Switzerland���s history is closely aligned with that of South Africa. Swiss banks, corporations, artists, solidarity movements have all intersected in the former���s relationship to the latter. If we take Switzerland���s relation to South Africa during apartheid; the Swiss government���s ���neutrality��� towards the Swiss corporations and banks was one of the core concepts. The enterprises ���just�����did business���never politics. The state too pretended to not be responsible. This of course was just the public pretense. Behind the curtains, the Swiss government supported relations with the apartheid system, for financial, racist and���allegedly���anti-communist reasons. From 1958 on, the Swiss government and the apartheid regime worked together to relocate companies such as UBS Bank (formerly known as SBG) to South Africa, in case of nuclear attacks or political fallouts in Europe.

Exploring ���political neutrality��� (more on that later), is one of the themes of Converting Eviction (working title), a performance-project and a transnational collaboration between the Johannesburg-based collective Ntsoana and KMUProduktionen from Zurich, Switzerland. Within a trans-national framework, together we try to reflect upon the history of exploitation, property and��eviction of people out of their living conditions.

Some of our starting points were: The actual threat of evictions resulting from the Xolobeni mining project in the Wild Coast region; the movement to reclaim the recently discovered remains of the Kweneng Kingdom; Swiss-South African relations during apartheid; the attempts by the Jubilee 2000 movement for cancellation of apartheid debt; and the Khulumani Support Group���s work to hold to account 28 companies and banks that profited from dealing with the racist apartheid regime.

As we approach the following questions, we are strongly aware of our respective positions: That of Swiss-based cultural workers, struggling for some kind of global solidarity while still profiting from involvements into a colonial past and a strong neo-colonial, neoliberal present. And, that of African artists, who reflect upon self-images shattered by apartheid, while re-constructing new futures.

In our conversations as Converting Eviction, here are some of the questions we���ve asked and reflected upon:

What political and economic structures lead to people being evicted?

Wealth �����Wealth should not be material accumulation, but rather ���wealth in people���. Housing is wealth from and for people.

Naturalized Economy�������Evictions are enabled when capitalist economy is defined as ���neutral���, rather than anti-social. Such an economy attempts to turn every human relation and all basic needs into quantifiable and extractable commodities. Be it water, housing, emotions or friendship. Through this process, capitalist economy has been split from collective living, culture and politics, and thus is conceived as ���neutral by nature���.

As Felwine Sarr puts it: In African societies, the economy used to be embedded into a broader social system. It is no longer like that. To anchor the economy in society again, African societies could reconnect to relational economy; that is ���including the whole palette of positive and negative relations, that individuals build up, produce, exchange, or perpetuate���independently from material considerations or pure material interest.��� So called ���informal economy�����would also be an important part of that relational economy, even though contested from the point of view of ���good government��� and not considered if it comes to estimate the gross national product of a country.

Political neutrality ��� Again, with Sarr, such economical abstractions have been the very motive of colonialism for ages. They were meant to dehumanize black workers, render their landscapes into extractive economies and universalize the Global North/western concept of the human being. African societies were framed as needy and inferior. In combination with the physical eviction of people out of their ancestral and legitimate spaces, the eviction of colonized people out of their cultural realm was a necessary and horrible stepping stone towards the extraction of wealth.

These structures persist until today, spatially and mentally. They have been reinstalled by neoliberal concepts, that, again, pretend the economy would be ���neutral��� or ���natural.��� The colonial scheme has shifted to ���no alternative��to neoliberalism������exploiting black labour while wielding the threat of violence, as shown by the horror of the Marikana-massacre and workers dying in Swiss-based Glencore���s mines every year.

Emptiness �����Switzerland participated in upholding the apartheid-idea of South Africa as an empty and basically white country. The relocation of bank head offices���a dislocation-agreement between Switzerland and South Africa���was conceived directly after the Sharpeville massacre, and at a time in which, cynically, international investment to South Africa grew from all sides. In the eyes of the investors, it seemed, the apartheid-state had violently proven its will to keep cheap black labour under control.

It was crucial that apartheid did this not only on its own terms, but with international support and esteem. Nowadays, it���s poverty and the lack of education, which are used to discriminate against people, force them into underpaid jobs, and move them out of areas that are claimed by the rich and so called knowing�������who are, historically, still white. As long as the education-system is not changed radically, such discrimination along racial lines will stay in place.

What are the minimum appropriate conditions needed to make a home for oneself and one���s family?

Colonial phantasmagorias ��� If we speculate about what ���standards of living��� means, the structural global injustice becomes obvious. Too often conceptions of ���liveable life��� are compared with the north/western standards of the colonizers���including��the ideas of success, self-realization, or how a family should look. These phantasmagorical visions are omnipresent and very much still responsible for wrong approaches not only in the former colonized countries, but in the Global North/west as well. As these phantasmagorias of wealth grew themselves on colonial land-taking and exploitation, specifically in the USA, they were wrong from the beginning. The US-American standard of each family living in a house of their own, owning two cars, following heteronormative gender- and job-relations��was enabled only by huge amounts of violence against indigenous people, enslaved black workers and nature. Now why should these ideas still be exported globally, to solve housing problems on the African continent? To conceive houses for a core-family of father, mother and two kids?

Ubuntu, again �����Together with the reestablishment of a relational economy, relational family- and social-structures, a broader understanding of human networks through friendship, solidarity and migration should be reconsidered. To enable such networks that produce sustainable living conditions for every human being, idea of shared properties, ubuntu, cooperatives and transnational communes have to be picked up and improved. Private property has to be overcome.

What are the traumas of the past that are restricting people?

Recognition �����As long as there is no recognition of all the harm done by white colonialists, the trauma of violence and eviction will remain. After so many perpetrators got away unpunished through the process of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, it���s time to re-evaluate the crimes committed,��on the physical level as well as on psychological, cultural and material ones.

Economically, the colonial north/west is afraid of making any confession. The South African Khulumani Support Group wanted to hold 28 international corporations and banks to account in a New York court, for trading with and thus supporting apartheid. The case was lost, in 2014.

Silenced history �����If corporations would have been sued for their profit making with Apartheid,��and such a precedent could have been made, the opportunities for other de-colonizing countries to do the same would have risen enormously. A big threat for colonial profiteers! That���s why Switzerland, obstructed its own official research: The very executive, the ���Bundesrat,��� which ordered the research project into the Swiss-South African relations from 1948���1994 (the so called NFP42+ ��� National Funds Project 42+, from 2001���2004), decided to close all relevant documents in the Federal Archives regarding the Swiss-South African relations, as soon as the historians started their research. This silencing is no approach to historical harm, but on the contrary trauma-extension.

What is the agency that people have to convert hostile environments in a way that suits them?

Voicing Involvements �����We could research and document experiences of witnesses, digging into our personal relations, and make them speak. Everybody should have a very close look into his or her or their involvements into any kind of racist policies. Only then can our societies start redefining themselves, by changing the passive role of the victim into an active one, and unlocking the perpetrators��� silent aggression. And only then, can we find ways for perpetrators who profited on a very abstract or structural economical level from racism and colonialism to pay back what they took.

Deviant Narrations �����The legitimation for eviction lies in ways of ���narrating space,��� i.e. naturalized narratives about what belongs to whom and why, and then embedding these stories into a legal framework. Therefore, we have to start telling new stories and produce counter-narratives that enable a redistribution of resources, which are no longer solely based on the idea of private property.

Ghosts �����The countries that suffered and still suffer from colonial exploitation need the opportunities and means to re-center their understanding of themselves. These decolonizing countries offer crucial insight into rethinking the concepts inherited from colonialism, and to confront them with their ancestral economic and social ideas���ideas that are older than liberalism or neoliberalism.

These ghost-like social relations need to be reactivated to confront nowadays��� neoliberal exploitation of the world���s wealth. One important step will be to question the form of the nation-state itself. We have to bring up new concepts of migration, and understand how it is weaving peoples and families together, creating places, housing opportunities and alliances beyond nationality, as social theorist Achille Mbembe insists. On a small-scale level, it will be all about sharing-economies and sharing the legal and economic knowledge that allows us to create small cells of collective wealth.

The reading habits of Ngugi wa Thiong’o

Image credit Kanaka Rastamon via Flickr CC.

In February 2019, the Kenyan cultural studies scholar Joyce Nyairo moderated a public discussion between celebrated novelist Ngugi wa Thiong���o and his son, Mukoma, also a writer. In a write up of the event, a few days later, Nyairo said the event confirmed something for her: ���… what I have always suspected about Ngugi: Outside his own children, he doesn���t read anyone else.��� Hers was a suspicion I share. To me the real surprise was that he still reads at all.

Ngugi finished what he considers his magnum opus, Wizard of the Crow on 10 March 2002 as he announces in . Since then he has published in two forms of writing that require the least critical engagement with other writers: memoirs and lecturers. A great memoir or lecture is easier to write than, say, a great novel or play.

In an interview from 2008 Ngugi asserts that ���if you ever arrive at the complete truth, you will have nothing else to live for. Except maybe living that truth over and over again.��� Could it be then that Ngugi arrived at his truth years ago unwittingly, and has since then been repeating it, trying unsuccessfully to patch up something old and torn?

Ngugi’s advocacy for the Mau Mau liberation movement

One way to interpret what Ngugi told an interviewer in the late 1970s, that he ���feels that Kenyan history, either precolonial or colonial has not yet been written,��� is that Kenya was doomed to cultural stagnation until Ngugi felt satisfied with the composition of Kenya’s historiography.

On account that his most recursive theme, the Mau Mau liberation movement,��ceased to be regarded as terrorists by the state in 2003, hence marking a turning point in Kenya’s historiography. Had Kenya’s foremost author reached his truth, the apex of creative expression, after which an author begins to repeat himself or herself? If the answer is in the affirmative, then Ngugi���s series of memoirs published between 2010 and 2018 can be read as a long sigh of relief, a sign of contentment and even achievement.

But this is not quite how things went. In fact, Ngugi had been repeating himself for decades when the Mau Mau movement ceased to be for the republic of Kenya what Al Qaeda is for America. That is to say, it is possible he reached his truth much earlier than 2002-2003.

Old from the very beginning

Ben Okri, in his introduction to Weep Not, Child published by Penguin books (2002), states that ���if Ngugi had published nothing other than Weep Not, Child, he would have earned a distinctive place in the African literary canon.��� Responding to the claim, Evan Mwangi asserts that unlike some of his peers, Ngugi���s career took some time to bloom. I agree with Mwangi to a certain extent, but Okri makes a point here related to what I have discussed above. It is this: despite his half a century in letters, Ngugi has really written one book, his first. In the same introduction, Okri writes that ���in a sense, all the future Ngugis are embryonic in this novel��� which again suggests the numerous repetitions, reviews, and retells in Ngugi���s body of work.

However, while I’m for the idea that Ngugi reached his truth before Wizard of the Crow and the Mau Mau acquittal, I do not think he reached it as early as first published work.

Ngugi reaches his truth

In Weep Not Child, England was for Ngugi the “home of learning” where people go, once they have exhausted learning in Kenya, to study further. But later he changes this view in Writers in Politics referring to his own education in the literatures of the West as an “impoverished diet.���

However, from the Bertolt Brecht quote that marks the end of Decolonizing the Mind to the The Waste Land quote at the beginning of Dreams in a Time of War, Ngugi shows the ornaments of a man who has spent thousands of hours poring over books of Western literature.

And so in referring to them as ���impoverished��� Ngugi flouts the very books that helped him become the writer he is today, or at the very least he owes them for his writing in the 1960s which is for me the decade he produced his best work in.

I place Ngugi’s culmination of truth roughly between the publications of A Grain of Wheat and The Trial of Dedan Kimathi, with perhaps the earliest display of Ngugi���s ambivalence with books being when he let a peasant who would not read at all to provide the lyrics for the Gatiiro dance in The Trial of Dedan Kimathi, as we read in Simon Gikandi’s book on Ngugi. In this incident, Ngugi downplays not just the importance of literacy in creative composition, but of education as well.

In the early Ngugi, Shakespeare and Achebe ���assert their immortality most vigorously��� as T.S. Eliot put it. Regardless, Ngugi is still extremely well-read and diversely knowledgeable in a way those that adhere to these assertions without prior interrogation will never be.

October 14, 2019

Are you safe? Please stay safe

Cape Town���Late Town part 02. Image credit Anne-Sophie Leens via Flickr.

I was very excited when I was given the opportunity to study in South Africa in 2017. Cameroon���s political crisis had reached boiling point. On October 1 of that year, the Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Consortium United Front had declared its independence from Cameroon���s French-dominated central government. Foolhardy boys were being encouraged by online ���leaders��� of the Anglophone secessionist movement to take on the Cameroon government. Meanwhile the mercenaries also known as the Cameroon armed forces were killing these boys from Ambazonia (also known as Amba boys) like flies. Still, the news of my scholarship came with apprehension, knowing what I had heard of South Africa: Periodically, locals had gone on pogroms against Africans from elsewhere on the continent, there as immigrants, refugees, students or temporary migrants. Hundreds had been killed, often in a gruesome manner and thousands left homeless.

Several people asked if I would be safe and I responded with false bravado, ���Would you ask me that if I was going to the US given how often mass shootings happen?��� Still I recall breaking down one evening, a month before my departure. I had read an academic article by my then-prospective supervisor about horrific sexual harassment statistics among South African students. I wrote to a close Cameroonian friend and told her I felt like having sex before I left, so the first time would at least be pleasurable. God forbid, I traveled to South Africa and that first time was a rape.

I was having this conversation in the dark, due to the power outage in my part of Buea that evening. I struggled to find a taxi heading into town to meet another friend, someone I was meeting in person for the first time. As I crossed Mile 16, I came across men wearing heavy armor, their presence frightening. But despite the violence and instability at home, South Africa seemed scarier because of its rape statistics; scarier than America���s mass shooting; and even more so than La Republique Du Cameroun���s hired men with guns who made getting a taxi difficult, and robbed me of the very sense of security they were meant to ensure. I remember my new friend telling me not to be so worried about South Africa. Later that night, I prayed, ���Lord, I will not experience what my mother has not experienced.��� It was a silly prayer because I���ve never asked my mother if she���s been raped or sexually molested. And she���s never asked me either.

I stayed in South Africa for nine months uninterrupted before I visited Cameroon again. During my time away, the crisis back home grew even worse. I often joked with friends that the fear I had of South Africa was now directed towards home, as we increasingly heard of both soldiers and Amba boys raping young women, of homes being burned with its occupants inside, of kidnappings, and of mutilations. By the time I returned in December 2018, I wrote out a will; dramatic, I know. I prepared my mind and friends in case I was kidnapped: ���This is what you should do for me and who to contact.��� I bought a stun gun and pepper spray for myself and several female friends.

Back home in Cameroon, I adjusted to the insecurity. We have all adjusted to it. We have learned when and where to speak. Not to speak freely in public transport for fear of informants, nor to visit certain neighborhoods for fear of kidnapping. This was very similar to the way I protected myself in South Africa, by never being off campus late by myself. Never going downtown alone. The way I had my seamstress adjust my clothes prior to traveling to South Africa so they wouldn���t show cleavage, so too I adjusted my schedule in Cameroon and my identity to suit whoever I was dealing with; whether it was a Francophone soldier or an Ambazonia fanatic.

So, after one year, after experiencing a similar insecurity at home and abroad, when people write and ask if I am okay, I sometimes wonder how to respond. But these days, the simple answer is, ���Yes, I���m safe. I���m not at risk of xenophobia given my profession, socio-economic privilege and location on campus ������ Yet the more honest answer is: ���No one���s safety is sure anywhere. Today just wasn���t my day by God���s grace.���

Growing up, I moved around a lot so having a home of my own has truly been a great aspiration. Packing out of my place in Buea earlier this year was heart-wrenching, though I can���t complain when I know how many Cameroonians are lining up to leave the country by any means necessary. Still, this is the first time in a long while I can be classified as a real immigrant because it is the first time I am unsure of when my return ticket will be booked. When I considered writing the piece about my perceptions, as an uncertain immigrant, I thought of how one determines where one can be home.

I am often asked; ���Can you live here? Do you want to remain in South Africa?��� This question is generally posed by South Africans, while other immigrants mostly assume I will stay and even suggest what I could do after the PhD. I was told by a friend���who has never been to South Africa���that I should never let South Africans know I���m staying in their country for long, or else they will feel I came to take their opportunities and I will experience hostility. Luckily for me, my truthful response is considered the safe answer. I typically say, no, I���m not planning to live here. I want to return home, but I just don���t know how soon for sure. I have noted that this response puts some South Africans at ease, but not by way of, ���oh you���re not going to take my opportunities.��� I sense the ease comes from their sense of my privilege. This one isn���t desperate. This one has a choice. This one is just passing through because Ja, neh, if I was doing a PhD, I too would be passing through.

I feel the issue of privilege is often missing from discourse on the immigrant experience in South Africa. Oh, yes we know that xenophobic attacks do not target all immigrants equally, we have factored in race, but we haven���t really considered the power of perception. Who is seen as a threat and why? Where does the class struggle come from? I have only ever sensed hostility as an immigrant twice. The first time, it happened after I ventured towards an old white guy who drives a taxi and who had once driven me to my place on campus. The black brother on the side was upset, saw it as an affront that I had chosen the white guy over him without registering that I had used the old man before, or considered that the white guy���s taxi was nearer and I was struggling with bags. So, I was jeered at and made to feel small. Yet, I understood the brother, because when you have lived with racial inequality day in and day out, you tend to see everything as being about race (the reason why living in America can kill you). Every experience is then colored by race.

The next experience involved a group of young lawyers who accosted my colleagues and I���all of us immigrants doing PhD���s or postdocs. After the introductions, they asked us if we were government ministers��� kids because they couldn���t fathom us, immigrants, living on campus and enrolled in our respective programs, unless we were the kids of the government mis-managers looting the wealth of our home countries. When we told them that we were on full scholarships from the university their expressions changed. They asked us: ���Don���t you find it odd that the university can give you enough to get accommodation on campus when so many of its students have to come in from downtown and the townships because they can���t afford living on campus?” I did find it odd. I could have debated and told them that I deserve my sponsorship because I am providing a service to the university through my research. But, I recognized that even though I felt their hostility was against me, what they really hated was the unjust system. I was just a symptom of the disease. That I could see this, and that I could empathize with the black brother who was offended when I approached the white taxi driver, is in itself a privilege; the privilege of being educated enough to know better. A privilege many don���t have, and many were intentionally robbed of.

These two instances being my only experiences thus far, I feel ill-equipped to respond to queries about safety in the face of xenophobia, or to raise my voice in anger about it. To be honest, I see too many similarities between those who carry out xenophobic attacks and the Amba boys in my country. Their anger is justified, though they are expressing it in the wrong way and directing it at the wrong people. Victims of xenophobic attacks are the poor immigrants, the ones who can���t get white collar jobs and so have to struggle in the already brimming field of entrepreneurship, and blue collar work. The victims of xenophobic attacks are seen as threats because the South Africans who didn���t benefit from the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) wave see them as their only competition. Meanwhile the white minority and BEE beneficiaries couldn���t care less about correcting that misconception. I���ve yet to hear of a xenophobic attack against a university professor. And let me tell you, many are immigrants. Yes, there are stories of immigrant white-collar workers being passed up for South Africans, but nationals getting preferential treatment is not rare, and being a runner-up is a reality for immigrants everywhere.

Xenophobic attacks, however, are different. A bottom-level occurrence. As I learned in Cameroon earlier this year, being poor and of low socio-economic status amplifies everything. Those who are being attacked run small shops, vending kiosks, and work in the service industry. They live and work in the congested areas, in low-income housing, and are therefore not protected by the distance and aura of the suburbs. Just as is the case in Buea, where those who are forced to respect ghost towns and those who can have their homes raided at any time live in Mile 16, Bomaka and Muea. Just like I implied earlier, there is Buea and there is Buea. So too, there are immigrants and there are immigrants. We must not act like we are ignorant of why xenophobia is a thing. That ignorance is dangerous whether fake or real.

It shocks me every time I hear an immigrant complain about how lazy South Africans are, how much crime there is here, how much we immigrants deserve the opportunities because we are obviously more educated, more qualified, more willing to take pay that is lower than that of the white South African���s pay, and be happy doing the work. It surprises me, because I feel like before coming to South Africa, everyone should do their homework. Understand the policies, the history, and the social factors that contributed to a people not respecting the system of education. Be grateful���if you must��� that if we are ���better��� it is because we did not experience what they went through in their recent past. And finally, consider how the environment for crime was created. Actually, the last part makes me laugh because for a country with a supposedly crazy crime record, South Africa is still able to maintain its shops and buildings with glass doors and windows���something that couldn���t be done in Cameroon. We would rather have windows with bars, steel gates, and fences with prison wire and shattered glass at the top��� But I digress.

I hope you understand that I am in no way excusing xenophobia. Nor am I trying to paint South Africa to be better than it is. What I am trying to do is pass on a lesson I learned from Cameroon’s crisis. As much as we can call out the violence, let us not be ignorant about why it happens. A viral post that was wrongfully attributed to comedian Trevor Noah stated that those who participate in xenophobic attacks have ���misplaced anger and prejudice built on an inferiority complex.��� That is correct. So while calling them out for their attacks, can we address the roots of the anger they���re misplacing? Can we address the socialization that builds the prejudice and the inferiority complex? That could be a more sustainable solution.

My ongoing research examines the assumption that acquiring higher education empowers Cameroonian women by first re-conceptualizing empowerment based on relevant theory and the opinions of Cameroonian women themselves. As I followed tweets on #UyineneMrwetyana (a University of Cape Town student murdered by a postal worker when she went to pick up a package), my research came to mind. This young woman would be considered empowered for acquiring higher education in a country where statistics show she would have had to overcome a great deal to get there. But how empowered was she indeed? In light of her rape and murder, what power did she truly have to exist?

During my stay at home earlier this year, I was discussing with a group of friends and older colleagues about my ���protective measures���: the stun gun and the pepper spray. It began with them suggesting I was exaggerating, but the conversation unearthed a well of information about tactics women have devised to get themselves out of dangerous situations. If I planned to write a post about it, the title would be ���Things women shouldn���t have to know.��� I would mention things like carrying a red pen and a sanitary pad if visiting a male friend or new boyfriend���s house so you can go into the bathroom and fake a period if they come on too strong. Things like giving the wrong name and phone number when asked by a guy you do not want to share that info with but then putting off your phone and explaining that your battery is dead so they can���t try the number until you���re gone. Things like carrying your drink while dancing at a party so it is never left unattended to avoid getting drugged. Or, when having a boy visit your room, leaving your door open��� things like this and many more that prove we all know men have a problem with accepting a ���no.���

So when I hear ���stay safe��� or ���please take care��� in the wake of #UyineneMrwetyana, what I am reminded of is the need to take more protective measures to ensure I am not next. Because we expect another victim. A conversation with one of my research participants comes to mind. I said:

I am well educated, earn an income, speak more than one language, can vote and articulated my thoughts. I am so empowered��� So much so that I can worry about my dressing and change three times before leaving my house. So much so that a ���sorry��� starts nearly every other sentence I make. So empowered that I can���t wear a pant suit and gain entrance to certain government buildings in my own country. So empowered that I mentally debate word choice so I am not perceived as rude, unladylike, and unlikable. So empowered that I use my mom, or an imaginary partner as an excuse to fend off unwanted advances. So empowered that I walk around with pepper spray. So empowered that I know all these ways to survive. And yet, so obviously disempowered because I need all these ways to survive.

And that is how we are, learning to stay safe.

A lesson from a philosophy class has remained with me over the years. As Mr. Afanyi, my upper sixth philosophy teacher explained, one of the reasons Philosophy took off more in Greece despite the fact that the Greeks learned from the Egyptians, was because ���the Greeks had sufficiently answered the question of subsistence.��� In other words, one must address basic needs before emotional, psychological and intellectual battles. When you have no food, you don���t question whether you are using it to feed emotional wounds. Your stomach growling is far more pressing than any emotional hunger which would make you crave sugar.

So when I receive a message saying ���Seen the news of what is happening in South Africa, are you safe?��� I usually appreciate the concern, but then wonder if I should respond truthfully; should I say that I am not safe, especially from myself?�� Then I remember, no, they are asking about physical safety, and not the insecurity of your mind that cripples your ability to function.�� But the irony of responding that I am safe amidst the xenophobic attacks while still struggling with, and recovering from, thoughts of self-harm is one which I don���t have the words to capture here. Let���s just say it���s a poignant incongruity.

What is more of an enigma is how one responds to those concerns being shared by people who are contributing or have contributed to your poor mental health. Imagine the effort it takes to unlearn toxic thinking and heal unseen wounds by yourself. Then imagine that the person responsible for your wound writes to wish you to stay safe in the midst of the violence. Yet, as much was one would like to scoff at these concerns knowing that even the threat of physical harm trumps the reality of emotional and mental harm. So, when asked, ���Are you safe?��� You don���t respond that you���re dying slowly; fighting hopelessness and looking for a reason to believe you should keep trying every day. You don���t say you are not okay. You don���t say you are walking around scathed, ���faith-ing it till you feel it.���

You take the question the way it is given, not the way it could matter. You interpret it simply as ���are you out of harm���s way?��� To which you respond, ���Yes, I am safe. My neighborhood hasn���t had any xenophobic attacks yet.���

October 12, 2019

Eyes on the Prize

Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in Hawassa, Ethiopia. Image: Fitsem Arega, Chief of Staff, Prime Minister Office, Ethiopia.

Ethiopia���s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed won this year’s Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to end the two decades long Ethiopian-Eritrean ���no peace, no war��� stalemate. In its citation, the Nobel Committee got all lyrical: ���When Prime Minister Abiy reached out his hand, President [Isaias] Afwerki grasped it, and helped to formalize the peace process between the two countries.��� But, does this deal bring the kind of cooperation between the two countries that it aspired to do?

A year has lapsed since this historical deal was signed. Even though the peace deal seemed promising at first, and the land routes were re-opened in September, 2018, it was short lived; because, all the land routes were eventually closed by mid-April 2019 without any official explanation from both sides.

But at least the re-opening gave a chance for a brief moment of an intensified cross-border trade. During those brief months around 1,500 trucks used to cross the border per day carrying different agricultural products such as teff (Ethiopia���s staple food), barley, coffee, sesame and corn as well as timbers, house bricks, furniture and petroleum from Ethiopia. The same trucks would return from Eritrea with textiles and garments, and various electronic goods, although not fully loaded. These were taking place without any trade protocol, so the border crossing trade agreements paving a way for uneven and hostile trade relations.

Granted, this unregulated trade looked positive on the surface, it had been also a source of tension. Concerned about the untaxed goods, Ethiopian manufacturers were the first to profess their disquiet. Similar feelings were also forthcoming from the Eritrean agricultural goods��� importers whose prices deflated due to the influx of goods from Ethiopia. Meanwhile, this mass exportation of agricultural products such as teff had created fear of supply shortage among Ethiopian consumers.

The export of petroleum from Ethiopia to Eritrea – whose access to petroleum is restricted by government ratios ��� had created tension. This is because even if the exportation was done at a household level, it had created a shortage in border-crossing areas. The tension created by the shortage was further fueled as the petroleum was imported and meant to be sold only for Ethiopian citizens at a subsidized price. This was another jab to the Ethiopian economy which is already on its knees due to a foreign currency crunch.

This uneven and chaotic trade may make one to wonder, if the two countries��� new relationship would revert back their previous hostile economic cooperation.

Previously, the two countries were economically integrated till 1998 starting from Eritrea���s independence in 1991. During these years of economic cooperation, the two countries had strengthened their ties through a number of trade agreements. This includes the 1995 free trade agreement and the 1991 agreement on the use of a common currency, the Ethiopian Birr, used by Eritrea until it adopted its own currency. Significantly, in the 1991 agreement Eritrea formally granted Ethiopia free access to use the port in Assab and Massawa port for an ���insignificant transit charge��� of 1.5 percent. The agreement also allowed Ethiopia to run and maintain the Eritrea-based Assab oil refinery, necessary for providing its citizens with refined oil. The implementation of the agreements was overseen by a joint ministerial committee from both nations.

Although good on paper, both sides worried about being sold a raw deal. The agreement on the Assab Oil Refinery was one such source of tension. When the refinery was built in 1967 it was financed by a loan from the former USSR and a contribution by the Ethiopian government. When ownership of the refinery was transferred to the Eritrean government, no arrangement was made for retribution to Ethiopia. This was later seen by Ethiopians as benefiting Eritrea at their expense. Even though Ethiopia was now allowed to use the refinery, the agreement mandated them to pour 30 percent of its refined petroleum products back into the barrels of the Eritrean government. Over the following years, the allocation of refined petroleum to Eritrea rose from 17 percent in 1992 to 54 percent in 1997. As the demand for petroleum in Eritrea went up creating a shortage, Ethiopia found itself spending millions of dollars on petroleum imports to fulfill its domestic demand. Moreover, Ethiopia had to spend hard currency to purchase crude oil, which Eritrea got to buy at a subsidized rate in the local Birr currency after it was refined.�� This helped Eritrea to save hard currency otherwise spent on the purchase of crude oil.

Similarly, the deal that made it possible for Ethiopia to use the Eritrean ports of Assab and Massawa also had its downsides. Given Ethiopia���s dependence on these ports for most of its imports and exports, the ���insignificant��� 1,5% transit charge for the Massawa port turned out to be far from insignificant. According to an IMF���s 1998 report Ethiopia���s port service fees made up around 10 percent of Eritrea���s GDP.

Trade deficit was another source of tension. In the few years of the economic cooperation, Eritrea depended heavily on Ethiopian food imports to feed its population. Leather was also the second most imported commodity of Eritrea from Ethiopia. Since all of these purchases were made in Birr, the Eritrean government was expected to save its spending on hard currency. Meanwhile, the products Ethiopia imported from Eritrea consisted mostly of manufactured goods, such as machinery and transport equipment. In the years 1992, 1993 and 1994, Eritrea exported from 130,207 million to 345 million Birr worth of items to Ethiopia, according to a 1998 publication by The Reporter. By comparison, Eritrea exported only 47, 58 and 76 million worth of items to Sudan in those same years. By 1996, Eritrean exports to Ethiopia had reached as high as 70 percent while only nine percent of Ethiopian exports made it to Eritrea.

On the other side of the aisle, Eritrea accused Ethiopia of violating the spirit of the free trade agreement through protectionist policies, according to a 1995 report by the joint ministerial committee. The committee found that Ethiopia subjected Eritrean products to indirect taxes and various intermediate payments in every Ethiopian region. Tensions further escalated when Eritrea in late 1997 introduced its own currency, the Nakfa, the adoption of which required a clear delineation of their borders. Months later, a crisis erupted in Badme town, when an Eritrean patrol barged in to Ethiopian administered area. This ensued a clash that lead to the death of at least one Eritrean. In response, the Eritrean army marched in and forced Ethiopians out of Badme. The Badme incident proved to be the tipping point; in response, the Ethiopian government declared war on Eritrea.

In evident to this history where economic tension between the two nations played a huge role because of the 1998 war. We should draw caution before jumping into the trade opportunity opened by the reconciliation. Because trends are showing that this history of uneven trade and economic tension could repeat itself.�� The fact that the two countries are yet to set up a trade protocol and border crossing trade agreement should further raise our concern, so that we can prevent this vicious cycle. It also puts the Nobel Peace Prize in a more realistic light.

October 10, 2019

A living monument of the struggle

Ann Seidman speaking in 2006.

When Ann Seidman died this summer, her family received many tributes from veterans of the struggle in Southern Africa, including former South African President Thabo Mbeki and members of the Sisulu clan (originally from Soweto). It soon became clear that Seidman was an inspiration to generations of politically committed Africanists and to Africans directly engaged in liberation struggles.

Geraldine Fraser Moleketsi, who had been in exile in Zimbabwe and was a cabinet minister after apartheid (in Mbeki���s government), wrote an appreciation of Ann (and her husband, Bob) for ���the rigor with which they tackled their disciplines ��� their commitment to liberation ��� and above all to critical thinking,��� and ���of the way ��� they opened their family home to all of us.����� Barbara Masekela, for a while head of the ANC���s cultural desk and later ambassador to the US (trumpeter Hugh Masekela was her brother), wrote: ���Ann Seidman���s work is a living monument which will always be cherished.���

None of this would come as a surprise for those with knowledge of African liberation movements and the history of committed scholarship about the continent. In fact, Ann Willcox Seidman (born in 30 April 1926; died on 13 August 2019) dedicated her life to scholarly activism and to her deep commitment to the struggle for African liberation. She focused in her long career as an intellectual, academic, and activist on the impact of skewed economic development on the lives of people in Africa and the Third World, and on ways to confront and counter the inequalities that have grown within global capitalism.

Ann spent much of her life as a teacher and advisor on the continent. In December 1962 she and her husband, Bob, began lecturing at the University of Ghana, and she worked with Kwame Nkrumah on an economic theory and strategy for breaking neocolonial economic domination of Africa, serving as his economic advisor for the first Pan-Africanist Conference in Addis Ababa in 1963. As a leading dependency theorist, she authored, co-authored and edited numerous books and articles on African political economy. In the late 1960s she published two ground-breaking books as part of this anti-neocolonial project:�� Unity or Poverty: The Economics of Pan-Africanism (with Reginald Green) and An Economics Textbook for Africa, aimed at African students, which remained the leading economics textbook in English-speaking Africa for many decades.

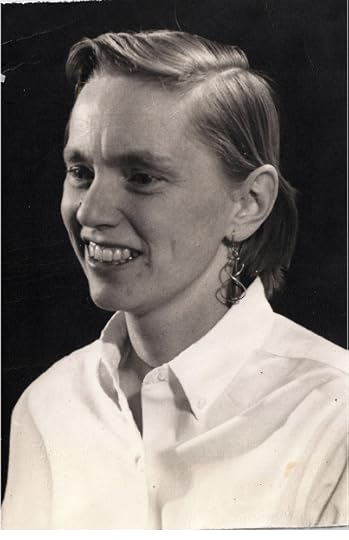

Ann Seidman in the early 60s. Courtesy of Judy Seidman.

Ann Seidman in the early 60s. Courtesy of Judy Seidman.After the 1966 coup against Nkrumah, Ann and her family left Ghana. But, she spent many years teaching economics in universities in East and Southern Africa during times of intense efforts at progressive social and economic change���as Senior Lecturer at the University of Tanzania from 1968 to 1970, Professor of Economics at the University of Zambia from 1972 to 1974, and Professor and Head of Department at the University of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1983.

From the mid-1970s, Ann worked jointly with Robert Seidman in the area they termed Law and Development, advocating the use of law to construct institutional change that could redress embedded socio-economic inequalities.�� During the mid-1980s, based at the University of Boston Law School, they jointly founded an institute to apply these theories in Africa, then in developing countries around the world (including China, where Ann taught at the University of Beijing from 1988-89).

In the US Ann taught at Boston University, Brown University, Clarke University, Wellesley College, the University of Rhode Island, and at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, but her job opportunities in the US were limited by discrimination by academic institutions against women as well as against Left economists. In the late 1970s she sued the University of Rhode Island for discrimination after the Economics Department reversed a decision to offer her a named professorship; while she won the case after years of litigation, she decided that she could not work harmoniously with those who had barred her.

Despite not holding a tenured post in an American university, her work became highly influential within African studies in the US as well as in Africa. Ann was also active in the African Studies Association, serving as its president from 1989-1990. She was an initiator of the ASA Task Force that developed strategies for changing US economic policies in Africa. In her presidential address she called on Africanists to challenge corporate power in Africa, and to help Americans understand the connections between corporate-created poverty in the US and in Africa. Within ASA Ann was an early activist in the Association of Concerned Africa Scholars (ACAS). The ACAS was founded in 1978 to pressure ASA to take political positions on American imperialism in Africa. She chaired ACAS���s Research Committee from 1977 to 1980 and 1983 to 1988, and also engaged in the writing and publishing of US Military Involvement in Southern Africa, edited by the Western Massachusetts ACAS.�� ANC intellectual Pallo Jordan, whose father A.C. Jordan, was the first black professor at the University of Cape Town and later went into exile, wrote: ���Ann Seidman played a crucial role in the early years of the solidarity movement in the USA. Her family���s involvement in our struggle and South Africa���s future is testified to by [the work of her daughters] Neva, Gay and Judy.���

It is striking that one of the most ringing endorsements of Ann���s life work came from a postapartheid South African soldier. Colonel I. S. Moss, a former MK soldier who became part of the new postapartheid army, the SANDF, was a participant in the Legislative Drafting Workshop held by Ann and Robert Seidman in 1994 at Pretoria University. In a recent comment, he spoke for many veterans:

She was a mother to many of us in the liberation movements. She always taught us to be critical and to separate perception from reality in order to formulate laws and policies that will spearhead and consolidate our new found democracy. May her soul rest in peace. African revolutionaries will always salute her��contribution together and in association with that of her late husband. I am privileged to have been taught by them.

October 8, 2019

The resistance music of the Ugandan people

Image credit Martin Giraldo via Flickr CC.

Robert Kyagulanyi, a.k.a. Bobi Wine, continues to make waves in Ugandan politics, unbowed by the Museveni regime���s violent attempts to crush him and his red beret-wearing People Power movement. Before Wine entered politics in 2017, he had already established himself as the ���Ghetto President��� of Uganda���s pop music world. In his reggae-inflected hit ���Ghetto��� (with singer Nubian Li) he excoriated the regime for exploiting slum dwellers for their votes, then abusing them with its neoliberal policies. Wine���s lyrics were blunt, indecorous, and rooted in street life, recalling another African pop music ���Black President,��� Fela Kuti, as well as the political reggae of Bob Marley and hip hop artists like KRS One. In his angry directness, Wine represents a generational shift in Uganda���s long tradition of musical politics, though he also builds upon this tradition.

The pre-colonial Uganda region was the site of kingdoms that were heterarchical rather than purely monarchical in nature. It was assumed that the power of kingship would be balanced by other semi-autonomous powers���namely, the clans with their clan heads, as well as the spirits with their spiritual healer representatives. Ngoma (music and dance) was used to express this balance of power in public. Each king, clan elder, and spiritual healer possessed his own troupe of musicians, battery of instruments, and repertoire of songs. Even today, drumming on clan-proprietary instruments is still used to keep the Buganda kingdom ���in tune,��� as Damascus Kafumbe has detailed in his book, Tuning the Kingdom. Within this musical system, critical singing, expressive of the political concerns of the common folk, was both possible and expected, but it had to be done carefully and politely. Grievances were to be couched in esoteric and ambiguous proverbs and cushioned with praise of the powerful. Besides being in keeping with the values of empisa (manners) and ekitiibwa (honor), this indirectness in song gave the artists and their backers plausible deniability, should the king or clan leader rise to vengeful anger.

The arrival of phonograph records, radio, and cassettes introduced a new democratic potential to music and politics in Uganda. Whereas live performance had always been pitched to the most powerful dignitaries in the room, mechanically reproduced music put every listener in the privileged auditory position of a chief or king. This was truly ���popular��� music in the political sense of the term. A new, distinctively Ugandan sounding music crafted for mass media came to be known as kadongo kamu (���one small guitar���). Kadongo kamu singers, such as Christopher Ssebaduka, Paul Kafeero, Herman Basudde, Fred Ssebatta, Matiya Luyima, Sauda Batenda, and Florence Namirimu, carried on the old bardic tradition of singing long, elaborate, stories in veiled, suggestive, Luganda language. Thematically, however, these singers focused much more on the trials and tribulations of ordinary people. They sang songs about the difficulties and indignities of getting by with little money in the city���an alternately exciting and alienating space that was becoming increasingly important in ordinary Ugandans��� lives. They sang songs praising and criticizing the actions of the new nation-state���s leaders. The kadongo kamu pioneer Ssebaduka, for example, praised President Idi Amin for his expulsion of the South Asian merchants, whom the singer reviled as ���bloodsuckers.���

Bobi Wine has paid homage to kadongo kamu as the genre historically most representative of Uganda���s lower classes. In 2010, he remade Paul Kafeero���s famous song ���Dipo Nazigala��� (���I Left that Depot���), as ���Ghetto Nazigala,��� perhaps signaling that he was the true inheritor of the legacy of this esteemed kadongo kamu master who died in 2007. It is clear, however, that Wine does not wish to be seen as a card-carrying kadongo kamu singer���he is doing something new, which his fans have dubbed ���ghetto��� music. One notable departure from kadongo kamu is in Wine���s unapologetic celebration of the urban slum. While kadongo kamu singers have often mused about the pains and pleasures of city living, the moral heart of that genre has remained in the rural villages. It is in idealized rural space that singers like Kafeero have searched for the traditional social values that animate their art. Wine���s music, by contrast, speaks powerfully to a new generation of young people who are urban to their bones. Many have lived their whole lives in the slums and do not feel the same emotional ties to a rural home space that their parents did. The celebration of the streets, in all their roughness, is of course a prominent theme in reggae and hip hop, which partly explains why these globalized genres have appealed so powerfully to youth in swelling cities around the world.

Wine���s ghetto music also stands apart from kadongo kamu in its bluntness. In refusing to comply with the regional tradition of elegant indirectness in singing (still very much alive in kadongo kamu), Wine seems to signal his refusal to work within the traditional heterarchical politics which that kind of singing has long helped to maintain. It is no longer enough, he seems to suggest, for coexisting gerontocracies to supposedly balance each other out, preserving the peace and enabling some freedom of movement in their lower strata. What Uganda needs today is a revolution from the bottom up, with little regard for traditional values of order and deference. It is this message, articulated in song, which may make Wine���s political ascendancy especially threatening to the Museveni regime.

Multimodal memories

Zuhair Mehrali in Sketches 2017.

Zuhair Mehrali is an East African artist of Indian descent living in Birmingham in the United Kingdom during the Brexit era. His project, Sketches, is an award-winning and groundbreaking multimodal digital experience exploring fascism, identity, and transnationalism. Sketches combines charcoal sketches, interviews, media clips, and film. In an effort to understand this project and Mehrali���s goals in creating it, I interviewed him and include his responses in full below.

Liz Timbs

The first shot in your film is of a Victor Hugo quote:

Exile is not a material thing, it is a spiritual thing. All the corners of the earth are exactly the same. And anywhere one can dream is good, providing the place is obscure, and the horizon is vast.

How does Sketches build from/build on these reflections on place and identity?

Zuhair Mehrali

Hugo���s quote brought me great comfort during a time of feeling alienated. I discovered it as the prelude to Czech photographer Josef Koudelka’s Exiles, a powerful collection of photographs documenting physical and spiritual detachment. Being born and raised in England’s multicultural second city, Birmingham, living in the Cornish South-West during university left me feeling ���away from the culture.��� It was there that I began recognizing the inextricable link between place and identity. This self-interrogation was exacerbated in my final year [of university] by the knowledge that after graduating I’d be returning home to my parents with a fractured, unresolved sense of the cultural and religious values they’d instilled in me growing up. And it was in this period that I chanced upon Hugo and Koudelka, before deciding at my tutor’s suggestion to explore ancestry in my final project. (I recognize that my experience was not of any physical injustice or economic insecurity, but more of a psychological sense of dislocation���probably something hard to avoid when entering an institutional bubble.)

I began [this] inquiry by interviewing my parents���Indians born in Uganda and Tanzania in the second half of the twentieth century���while scouring several archives pertaining to East Africa, such as the Uganda Collection held by Carleton University [in Canada] and the Watson Kintner Film Collection at Penn Museum [in the United States]. At this point, I hadn’t considered the project’s form or narrative, until an almost unconscious moment during a break back home in Birmingham, I sat in front of the TV in a kind of slumber. Images of bright shirts and sharp ties, Donald Trump’s quackeries, and refugees at sea cross-faded with each other, as if my eyes were stuck in a DSLR auto-focus loop, interrupted by my parents behind me jokingly referring to one another as ���refugee��� and ���immigrant.��� I’d never properly confronted the realities behind these labels; there was a disparity between what I know of my parents’ experiences and those ���other��� subjectives being shown on the news.

An abstract of the project was essentially delivered to me in that moment: a dream-like film construction of displaced identity, collaging the places before me with the voices behind me.

Liz Timbs

One of my favorite parts of the film is when you are sketching a drawing of Trump while video footage of Idi Amin plays in the background. How does this film help understand the present in terms of fascism in past contexts? How do your parents’ memories of living under dictatorial regimes in Uganda and Tanzania help you understand current politics?

Zuhair Mehrali

That scene in the film presents a sort of triangle of connections between a) Idi Amin, b) Trump, and c) my parents (voice-over). To understand any one of these subjectives and surrounding contexts, I seem to refer to the other two. For example, to construct a meaning of East African politics and regimes in the 1900s, I draw from my parents��� oral history accounts and whatever media and current events I’m experiencing at the time. Or: ���a��� from ���b��� and ���c.��� During the making of the film, ���b��� was American politics, but that vertex in the triangle can be replaced with other contemporary examples, such as the Brexit fiasco on my doorstep (though it remains true that I find it easier from the thick of my host locale to observe ���external��� over ���internal��� politics, looking from the outside in, through other people rather than myself). Or the vertex can be switched to [Narendra] Modi’s authoritarian populism in India, another geography to which I am ancestrally linked. All this also works vice versa; ���the personal is political.���

Liz Timbs

What does art mean to you? Is it criticism, nostalgia, memory, or something else?

Zuhair Mehrali

I’m not naturally articulate and have always found it difficult to synthesize what’s in my head with���to borrow from Stuart Hall���the ���confusing fabric��� presented by ���the real.��� Art weaves these together, demystifies them, and is more truthful than either. It is for me a way to live consciously and engaged, to feel less alone, and in continuing with the clich��s I would say it allows us all to carve out spaces in which we are at liberty to be entirely ourselves. Within the accumulative, dehumanizing effects of integrated world capitalism, this space is both refuge and vantage point, especially when held by collectives. And I intend to uphold it, inspired by John Berger’s compulsion to re-render a Rembrandt of Simeon and the infant Jesus: ���My wanting to try to do a drawing of the painting had nothing however to do with words. I simply wanted to look closer at the way the swaddled child was lying like a fish across the old man’s outstretched forearms, with the thumbs and eight fingers of the two hands almost but not quite touching.���

Liz Timbs

Do you think that the multiple media presented to the viewer simultaneously provides a commentary on identity? Or was there another intent with that?

Zuhair Mehrali

It does, although it wasn’t intentional at the time of making. My intention was only to arrange multiple media by layering and juxtaposing them, which I learnt is known as ���montage.��� My tutor brought this form to my attention as the philosophy behind the inspiring work of John Akomfrah, who describes its outcome as the production of a ���third meaning.��� This is dialectical, and in the context of Sketches, it was borne from the collision of focused archive and oral history, current news and HD digital video, and a (subtle) fiction narrative. The interactive version of the film, Sketches Studio, offers a real-time deconstruction of the montage, in which these elements can be interrogated.

In retrospect, I believe that creating such discourse was in pursuit of what constitutes my own identity, perhaps in seeking an antidote to this question. But multiple possibilities continue to arise in the discussion and I’m learning that identity, or the concept I am interested in, doesn’t pertain so much to my nature as it does to the realities I’m connected to.

Combining multimodal stories from different perspectives creates a beauty in its output of new meaning(s), which can be shared and embodied by people to encourage deeper understanding of each other and themselves. I suggest that identity resembles montage.

Liz Timbs

Where/what is home?

Zuhair Mehrali

Anywhere one can dream.

Liz Timbs

Do you think the digital media experience you created through this project���with simultaneous video, audio, text, images, etc.���mirrors the refugee experience?

Zuhair Mehrali

Probably not, but if it does, it does so reductively; I’m not sure to what extent the experiences are symmetrical. Sketches presents a particular, fragmented refugee experience by using unedited/unverified oral histories and aesthetic transitions between HD video and archival film to suggest the bilateral impact of past and present, retaining an honesty of uncertainty. I think it’s important to remain conscious of fallibility���of narratives, of personal prism���and so Sketches Studio was built to serve as the tool for interrogating the veracity of exact details and references for oneself. So it’s probably more appropriate to say the project mirrors the non-refugee’s perception of the refugee experience.

This was embedded in the film in traces left on environments and objects to which people were once associated, but who are not present within the frame’s timeline, in a sense of erasure. For the majority of the film we see large landscapes of the present, focusing at times on features suspended in inertia, such as barren trees, derelict aircrafts and satellite dishes. Until the final act, the lack of life and motion in these scenes is filled in by the voices of my parents recollecting the past of another geography, and by archive film of that geography, all visibly synthesized by the main character in charcoal sketches. As this is a montage, the project expects the output of new (or “third”) meanings, which will inevitably differ between people, and this is why it can only be a conscious perception of the refugee experience, rather than its mirror.

Liz Timbs

How do the recollections/memories of your parents challenge the dialogue on identity politics in Africa in particular?

Zuhair Mehrali

My parents’ recollections for this film challenged my early picture of the politics they came from���a picture painted with a child’s excitable binary mode of thought. One as simple and singular as what I’d tell friends in the school playground, that ���Idi Amin was bad because he kicked my dad out of Uganda along with all the other Indians,��� before thinking: ���My dad is good, so all Indians must’ve been good.���

One night, when I was 11, he and I started watching The Last King of Scotland (after much pleading on my part.) The film dramatizes Idi Amin’s quicksilver temperament and post-coup activities from the eyes of his fictional Scottish confidant. At that age, its overt political set-pieces went over my head, and I only really registered the more shocking scenes, the most memorable being that of Amin’s ex-wife’s decapitated-then-reassembled body (supposedly by his hand). I asked whether this actually happened, and dad said yes, and that Amin did far more and worse than what’s depicted throughout the film. Then he turned it off. In later months, mum would tell me of the disturbing atmosphere during the Uganda-Tanzania War, when she was fourteen growing up in Dar es Salaam, some six years after the expulsion. In my early teenage years, such anecdotal contributions from family and media meshed in my mind to depict Idi Amin as a Macbethian dictator (he also claimed God spoke to him through dreams), enforcing my bias towards my parents (and Ugandan Indians, by extension), and probably subconsciously suggesting some insubstantial Indian vs. African narrative. This was long before I came to read an article published in 2003 by Ugandan-Asian expellee Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, while Amin was on his deathbed. In it, she confirmed my picture of the dictator’s monstrousness, wishing peace on ���the relatives of all those Amin killed, buried alive, raped, even ate.��� She also enforced that it was the Africans who suffered most during his reign: ���It was the blood of black people which flowed. They paid for our misguided foreign policies and post-colonial games.���

I hardly gave any thought whatsoever to the indigenous East-African populace before these events. Coming of age and making Sketches led me to understand that the Indians controlled most of the businesses and economy in East Africa, and that their racism against black Africans is deeply embedded since early colonial regimes when the British Empire pitted them against each other by way of ���divide and conquer.��� My general understanding is of the British as Master, the Indian as Servant, and the African as Slave. (This archived news footage is revealing, reported by Jonathon Dimbleby in Uganda just before the ’72 Asian expulsion.) There was a clear class system of economics and power, and James Baldwin would clarify that ���power is the arena in which racism is acted out.��� Of course, to attempt an understanding of the indigenous populace’s concerns is not to say I agree or sympathize with Amin’s methods of addressing them���he leeched off local contentions to establish his own brutal regime���but generally to warn myself against being so convinced of the certainty of my own solutions (as he was with his, and many authoritarians are with theirs).

In short, I think my parents’ recollections proved that my dialogue on Africa’s identity politics was a sketch-in-progress. And for me it probably always will be, as I carry a double-barreled ethnicity, and have never visited its origins. Vik Sohonie has previously written an honest, articulate piece on African-Indian relations for Africa is a Country.

Liz Timbs

What’s next for you? Do you foresee creating a full-length project based on��this short film/digital experiment? Do you have other digital projects in mind for the future?

Zuhair Mehrali

The Sketches project is ongoing. With the short film and interactive component (Sketches Studio, available online in public beta) complete, the next part is a hip-hop mixtape called Charcoal, which extends the meaning of the film from first-generation immigration (my parents) to second-generation immigration (me and my peers), hinging on the notion that my character in the film was silent and is now expressing himself. The music and lyrics have been written, and I am rehearsing and recording the songs this summer. After this, the final artefact in the series should be an assemblage/installation piece based on a specific anecdote from my mum’s life in Tanzania. The completed Sketches project would be a “proof-of-concept” or demonstration of my practice as a transmedia artist, in which I will also make less conceptual films (one currently in the works) and music, in addition to doing more creative writing.

In the future I’d like to write and direct a feature film based on my mum’s life, but wouldn’t attempt this until having had enough experience in narrative film-making.

October 7, 2019

A particular kind of black man

John. Image credit David Robert Bliwas via Flickr CC.

Tope Folarin became, for me, a literary voice to follow after I read his essay, ���To Be Where We Are,” in the fall 2015 edition of Transition Magazine. Two years before, in 2013, Folarin won the Caine Prize for African Writing. But, his win was met with much debate, the thrust of which was: Could this man, who was born and raised in America, and has never set foot in Nigeria, claim a Nigerian identity and win a prestigious literary award in the name of said claim?

���To Be Where We Are��� reads like a response to that debate. Folarin writes beautifully, that creation is working on itself in him. ���What does it mean if I say to you that creation is working on itself inside me?��� he continues:

Well, it means that I am made up of the stuff of the universe, like everyone else. Stardust and starlight and words and images and America and Nigeria and Africa and who knows what else. It also means that these familiar components have assumed new forms within me, that to spend some time with me is to glimpse possibilities that have yet to manifest themselves in our shared reality.

It���s a remarkable insight, one that I reach for in mild jest when I encounter Instagram skits of ���African parents��� that recall little of my childhood, and in desperation, when I fear that my Nigerianness, already tenuous in some settings, has been irrevocably eroded by my years in a mostly white, liberal United States. ���Preach, Brother Tope! Speak that truth!��� my heart yells. This notion���that social categories are not fixed as traditional thinking suggests, but that each of us, in living, come to clarify and reveal the possibilities in them���how liberating!

How true.

In a sense Folarin���s debut novel, A Particular Kind of Black Man is the story of a young man���s difficult journey to this insight. That boy, Tunde Akinola, is born black in the United States to parents who at the time of their arrival are so insufficiently attuned to American realities of race and difference that, when they are deciding where to settle, they make the tragically human decision to premise desires for isolation over other considerations, e.g. ���Are there other black people there?��� or ���Is this a sundown town??��� They land in predominantly white, small-town Utah.

American race drama ensues. There is a racist neighbor, though her breed of racism is uniquely Mormon. Kids at school don���t understand why the brown won���t come off Tunde���s skin. Tunde himself starts to wonder about the brown won���t come off his skin, and about his hair���s natural kinkiness. In the midst of this, mother becomes seriously ill with schizophrenia. Folarin does not explicitly identify the stress of migration and racism as a factor in the emergence of her illness, but one cannot help wondering. He does carefully lay out schizophrenia���s painful effects, the violence and upheaval it unleashes on the family.

Ultimately, Tunde���s mother returns to Nigeria. He is left with his father, a man working through his own relationship with America, as the primary source of love, identity, and a sense of home. (There is also, briefly, an unhappy stepmother, but Tunde never finds her love despite his best efforts). Mr. Akinola does point his son to ���a particular kind of black man������Sidney Poitier, Hakeem Olajuwon, Bryant Gumbel���as model for how to be. Yet, while he studies these men and makes himself in their image, Tunde knows that they ���do not match what is on the inside.���

Outside Tunde���s home, the world is in as much disarray. There is no stable definition of black boy, or later, black man for him to inhabit. Depending on where he looks, to Fresh Prince, to his little brother, to his friend AJ, to other black kids in a new school, what it means to be black moves and slips. Tunde moves through these shifts with a longing that is moving to witness, and an unrelenting bewilderment that comes off na��ve as he grows older.

By the time he is 18 and at Morehouse, the renowned HBCU, he makes a leap in insight and starts to intuit that he has been putting his energy in the wrong place all this time: ���I decided that the problem was that I spent my entire life trying to fit in one box or another; I decided I needed some time to figure myself out.��� Folarin���s wisdom about identity shines here, as he reminds us, through Tunde, that the more significant human task is to come to know oneself well, rather than rely on social categories alone for a sense of identity.

At the same time, Tunde has begun suffering from double memories and worries he may have inherited his mother���s schizophrenia. What follows is, for me, one of the most poignant passages in the book, for how it weaves the disorientation of double memories with the disorientation of modern identity tasks:

It���s hard to explain but I���ve always felt like I���m supposed to be somewhere else. I have no idea where that somewhere else is, or how I���d even get there, if it���s some other place or time, but I know it���s not here. I���ve never admitted these things to myself because I always hoped that I���d figure something out, because what���s the alternative? The alternative is the way I feel now: lost, bewildered, terrified.

The double memories, this business of figuring out who he is, it���s all too much for Tunde, so he turns from writing about himself to writing about someone else. Folarin has written about his intent with this perspective change, the gist of which is: Tunde is writing about himself and not himself at all.

I will admit, that as a reader, I may not have the complexity to engage those simultaneous realities. So as I read on, I assumed Tunde is still writing about himself. I do see how switching perspectives perhaps makes room for Tunde (and Folarin) to explore the more unseemly parts of self-making in a world shaped by ���identity by negation���we are what they are not.���

For instance, when he arrives a predominantly white college as an exchange student, Tunde-not-Tunde is preoccupied with blending in with the white majority and infiltrating their world for personal advancement. To be clear, this is not especially abominable behavior. It���s the sort of profoundly human thing that happens as people with marginalized identities navigate their lives. In fact, I appreciate Folarin���s integrity in representing these parts of identity negotiation that many of us carry, quiet and ashamed.

But beyond representing them, Folarin doesn���t engage the unseemly parts of identity negotiation that Tunde-not-Tunde reveals. Nor does he present a complex view of Tunde-not-Tunde���s judgment of the black kids that he is lumped with at Bates, clearest in the following passage:

Here, among these black folk, he detects a kind of determined provincialism. It seems the only thing they wish to discuss is home���the food they ate, the clothes they wore, the music they listened to, the stories they created and traded for themselves. The main currency in these conversations���the only currency, perhaps���is nostalgia. He now senses why it might be so difficult for these people to fit in. It seems they are all more interested in lugging their pasts around with them than stepping into the future.

Again, Folarin���s wisdom about identity shines (God knows that I have become the most obsessed with Nigerian cultural products���especially those of my childhood���since I left Nigeria). But I find it difficult to get over how incomplete this assessment is. Surely, a character who is observant enough to notice ���determined provincialism��� can also identify the conditions of marginalization from which it emerges. Surely, they can also see the possibilities for true connection that exist within it. So, what���s up with Tunde-not-Tunde? We never come to understand.

It is almost as if Folarin, as author, is disinterested in the ways self-making interacts with community-making amongst the marginalized. Of course, this is not a profound error, or any kind of ethical failing. But it is, to my mind, a missed opportunity. Another task that is crucial to self-making is figuring out how to be in community with those with whom one shares characteristics that are the basis of exclusion���race, gender, sexuality, etc.

Folarin doesn���t engage with this. Instead, he brings his focus on personal relationships: Tunde-not-Tunde meets and falls in love with a girl, Noelle, who eventually encourages him to reconnect with his mother. The book closes with that reunion, and we imagine that Tunde (he has returned to writing in the first-person) has found a version of the peace/home that he has been looking for all his life.

It���s a fine ending, in the way that it is committed to Tunde���s journey. And isn���t that all that we can ask of a book? To be committed to its characters? I suppose. Still, I find myself wishing that Folarin brought his keen mind to a more circumspect view of modern identity, not only one that identifies the private, intimate relationships where we can be our full selves, but one that is attentive to the challenges of and possibilities for community making in a world circumscribed by marginalization.

The end of revolutionary radio in South Africa?

Image credit Bush Radio.

In the small meeting room buried deep within Bush Radio���s second-floor offices on Victoria Road in Salt River, central Cape Town, and lying alongside an ancient Zenith Trans-Oceanic analog radio are two maroon leather cases. These cases are marked with the iconic golden dog and gramophone logo of His Master���s Voice, formerly the Victor Talking Machine Company. These cases contain original recordings of speeches, debates, poetry, and music performed by South African anti-apartheid activists���those deemed so dangerous that they were banned from gathering or speaking publicly by the then-government.

These recordings of illegal meetings and rallies, and the subversive thoughts expressed, were copied from the original cassette tapes onto many more tapes, and illegally distributed to oppressed communities throughout South Africa during the 1980s when a state of emergency led to mass arrests, murders, and torture of those who dared to rise up against the apartheid state. The tapes include speeches by now left luminaries like Professor Jakes Gerwel, then vice-chancellor of the University of the Western Cape and organizations like the then-banned African National Congress (ANC). They also include crucial information on healthcare, financial literacy, history and mathematics. These cassettes were designed to give millions of Black South Africans access to information and learning materials. These cassette tapes are known as the archives at Bush Radio���the fossils of what was officially called the Cassette Education Trust (CASET), the work of a group of activists whose struggle against apartheid would later morph into the mother of all community radio in Africa���Bush Radio.