Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 199

October 31, 2019

A pioneer of excellence

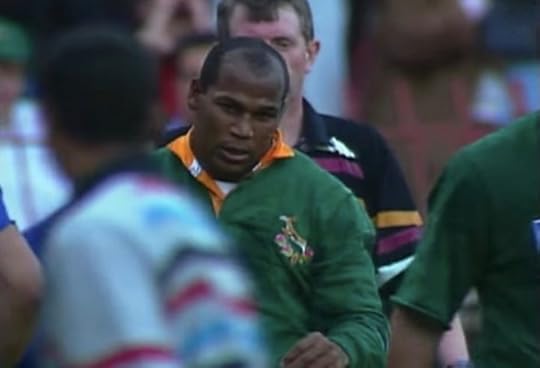

Screengrab from Youtube.

It���s November 26th, 1994. At Cardiff Arms Park, South Africa���s national rugby team, the Springboks are playing Wales and a lineout move leaves Springbok flyhalf Hennie le Roux isolated in the midfield. A ruck forms with South Africa on the backfoot.

The familiar voice of television rugby commentator Hugh Bladen blares: ���They need to just get it loose now. They need to loosen it up.”

The ball emerges for the dangerous young South African scrumhalf, Joost van der Westhuizen, who snipes through a half gap.

Bladen���s excitement rises: ���This is van der Westhuizen. And he���s got a gap. Look how he goes through it.”

The Springbok backs are suddenly flying, shifting the ball towards the left wing where Chester Williams, South Africa���s lone black player, is sprinting upfield in support.

Bladen���s pitch jumps again: ���Oh look at this, Andre Joubert.���

Bok fullback Joubert sends a final pass to Williams who receives the ball just inside the touchline, with 15 meters to the tryline, and with both Welsh halfbacks bearing down on him.

Bladen can hardly contain himself.

���Chester Williams!��� he shouts, as Williams bounces off the attempted tackle of the Welsh flyhalf.

���Chester Williams!��� he bellows again, racing against the opposition number 9, Williams shifts into fifth gear and dives, with arms outstretched, towards the try line.

���Chester Williams!���

���Chester Williams makes the try!���

A quarter century ago, major rugby test matches were far rarer than today, and each result perhaps more cherished. The Wales test took place only two years after South Africa���s readmission into international competitions. The Springboks had been isolated by the international community, viewed rightly as a symbol of the shame tied up in apartheid���s cultural machinery. The country itself had just emerged from its first democratic election. With a representative government and a progressive constitution promising socio-economic justice and dignity for all, South Africa was preparing to host the world for the first time at the following year���s Rugby World Cup. It was also to be the first time that the Springboks could compete at the tournament, which had its inception in 1987.

Chester Williams was democratic South Africa���s first black Springbok. Inevitably, with the world soon to be watching, he would be presented as a bridge to a new existence for South Africans.

As he rose from his diving match winner against Wales, Chester Williams raised his arms in victory. His all white teammates ran over to congratulate him.

���For me, Chester is a pioneer of greatness,��� said Gio Aplon, a former Springbok outside back:

For us. For a young boy that grew up in Hawston. A coloured boy, from a small community, our hero was Chester. We could relate to him. He made a dream possible for us. We could see him playing on TV and that made everything for us, playing for the Springboks, a reality.

Another coloured Bok flyer, Dilyn Leyds, echoes Aplon���s sentiments. ���All I wanted to do, playing rugby in the streets with mates, was be like Chester Williams. He was the guy that made it possible, that made us all believe that we can do that.���

In Invictus, Clint Eastwood���s Hollywood attempt at capturing John Carlin���s telling of the 1995 Rugby World Cup, Chester is offensively and baselessly reduced to an unthinking rugby playing machine, separated from any sense of the world off the field. In one of the only speaking lines given to the character,��the on-film Chester is asked his views during a team meeting. The players are debating whether the Springboks should take the time to attend a coaching clinic for a community of kids in an informal settlement. A fictionalized Afrikaner Springbok lock asks Chester to share his perspective with the team. The screenplay captures the scene:

Springbok Lock: What do you think about this, Chester?

All eyes on Chester, as if the poor guy is a magic guide to a world they barely understand.

Chester Williams: I try not to think. It interferes with my rugby.

As with many of the absurdities unnecessarily written into Invictus the film, Carlin���s wonderful book, originally published as Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and the Game that Made a Nation, makes no mention of this conversation. And there is no reason to think it happened.

In fact, contrary to Eastwood���s bizarre depiction, a young Chester Williams was acutely aware of what he meant to the country, and took his role seriously. In the lead up to the 1995 World Cup, the 24 year-old��told a journalist, ���I am representing my country. Being the only coloured as well, [I am] helping my community, to tell them that they must believe that they can also get into the Springbok side, no matter their skin or their colour.���

Young as he was, Chester understood that future Aplons, Leyds, and countless others had their aspirational eyes on him. ���All I wanted,��� he told the Economist in 2019, ���was an opportunity so that I can prove to the world that black people can also play rugby.���

Former Springbok captain Francois Pienaar recalled how it was Chester who reported to the World Cup team on the impact they were having. Drafted back into the squad just before the quarterfinals, after having been omitted from the pool stages due to injury, Chester Williams had a unique perspective from outside the camp.

It is true that Chester felt discomfort at his own commodification as the poster-boy of all black South Africans in 1995, and reflected on the marketization of his image to promote a change in the country that had a long way to go in substance. Still, he recognized the potential impact he could make as a role model. While reserved by disposition, Chester did not shy away.

It���s June 24th, 1995. The Springboks play the New Zealand All Blacks at the Rugby World Cup final at Ellis Park, Johannesburg. South Africa looked formidable coming into the game. Two weeks earlier, Chester Williams had scored a South African record breaking four tries against Western Samoa in the quarterfinal. For their part, the All Blacks had destroyed everyone on the road to the final, culminating in a 49-25 demolition of England in the semifinal in Cape Town. Their own incredible number 11, Jonah Lomu, had emerged through the tournament as a combination of speed, strength and skill unlike perhaps any other in the game���s history. Like Chester in the quarters, Lomu had scored his own now famous four tries in New Zealand���s semifinal. He had seven in the tournament overall���a record at the time and one that would be eclipsed by the eight tries he would score at the next Rugby World Cup in 1999. No team had figured out how to keep New Zealand, and Lomu in particular, at bay.

New Zealand lead South Africa 6-3 with around 15 minutes gone. It���s an All Black lineout just inside the Bok half of the field. A prime attacking opportunity. New Zealand move the ball wide quickly. Center Walter Little throws a skip pass out to his right wing, Chester Williams��� opposite for the day, the brilliant runner Jeff Wilson. As Wilson attempts to step inside, Chester rushes him. Dropping low for a thigh level tackle, Chester lifts Wilson off the ground, tipping him 90 degrees to the left, and unceremoniously dumping him back into the turf. In 2019, it is likely a red card tackle. In 1995, it was a legal and laudable cruncher. Wilson left the field later in the game, seemingly injured.

After an exchange of place kicking between flyhalfs Joel Stransky and Andrew Mehrtens, scores are tied at 9-9. The Springboks have a lineout, but the All Blacks steal it. With New Zealand shifting the ball from the right side of the field to their left, the Springboks are at their most vulnerable. They were set up to attack from their own line-out ball, and have no structured defensive line. As Jonah Lomu shifts in off his left wing for a cleverly timed switch call, he finds a sliver of space between Springbok flanker Ruben Kruger and inside center Hennie Le Roux. But Chester Williams has read the move. Sweeping from over on his left wing to the middle of the field, hanging just behind the line of Kruger and Le Roux, Chester meets Jonah. Dropping again into a copybook tackle, Chester does what no Englishman could do one week before. He brings Lomu down clean.

The Rugby World Cup final has gone, for the first time, to extra time. The score is 9-9. New Zealand scrumhalf Graeme Bachop spirals a kick deep into the left pocket of South Africa���s territory. Chester Williams sprints to field it, racing against Marc Ellis (who had replaced Wilson, and had famously scored six tries against Japan in the tournament���s pool stage). Under the pressure of a lifetime, Williams beats Ellis to the ball, deftly collects a difficult bounce, and introduces Ellis to the ground with a strong hand-off. To the resounding roar of the crowd, Chester Williams sprints the ball out of South Africa���s 22 meter area and into safety. The Springboks go on the win the match in extra-time with Stransky���s perfect late drop-goal constituting the difference on the scoreboard.

Chester Williams had planned to attend this year���s Rugby World Cup in Japan, where his new branded commemorative beers would be available. On Friday, September 6, he tweeted a video showing himself swinging boxes of lager with workers at the Goodfellows warehouse in Cape Town. He looked fit and strong, and handled the boxes as well as he had collected that bobbling ball under the impending shadow of Marc Ellis those 24 years earlier. Chester���s tweet told fans that he would be watching that afternoon���s Springbok test match at the Tyger���s Milk restaurant in Durbanville, a suburb north of Cape Town. Later that afternoon, the country learned that Chester Williams had died from a heart attack. He was 49.

Chester struck fans as a cerebral and technical genius on the field, and a kind, warm and humble hero off it. That combination endeared him to the world. His life inspired a generation of black and coloured rugby fans. That is his enduring legacy. But he also reached beyond racial divides. As an eight year-old middle class white kid watching the Rugby World Cup, I also wanted to be like Chester Williams. He was the Springboks��� and Western Province���s, star. The try scorer, the speedster. I remember noticing him at Newlands Stadium when I went to my first match in 1994, and I remember the special issue of Chester Magazine that I cut pictures from to paste around my bedroom walls in 1995. I would play out Springboks vs. New Zealand rugby matches by myself, imagining the remaining 29 players, and always scoring in the corner as Chester Williams. I fell in love with Chester first, and then rugby. Heroes humanize, and I suspect that Chester Williams helped develop the humanity in some amongst a generation of white children who may have been otherwise shielded from developing admiration, and adoration, for black heroes.

As the Springboks now prepare to contest its first Rugby World Cup final since 2007, Chester���s number 11 jersey is likely to be worn by the brilliant and in-form Makazole Mapimpi, a black South African whose story demonstrates both the reality of an unfulfilled societal transformation (Mapimpi walked 10km a day to attend an under-resourced school in the rural Eastern Cape) and the continued promise of a new dawn. The team is more representative than ever, but remains shrouded in the continued class and race challenges of South Africa. Mapimpi himself recently took to social media to confirm that a short online clip of post-match celebrations by a group of his white teammates had been misinterpreted as an act of racism against him, and to assure supporters that the team is unified. But despite the ���Bomb Squad��� debacle having been largely cleared up, Springbok lock Eben Etzebeth remains under investigation for his alleged involvement in a racist and violent incident leading up to the World Cup. While we can hope that this team has, at an internal level, bonded together, it would be na��ve to think that it could exist in a vacuum unaffected by prejudices and divisions that continue to permeate our country. That���s why Chester���s legacy needs to be sustained, and the hope that he represented is perhaps more critical than ever.

It���s July 20th, 2019. The Springboks have just defeated Wales at Ellis Park, Johannesburg. Debutant scrumhalf Herschel Jantjies scored a brace of tries. Jantjies is a coloured South African, born in the small town of Kylemore, some 20km from Chester William���s childhood hometown of Paarl. In 2017 he had been coached by Chester while playing for the University of the Western Cape.

Following the win, Siya Kolisi, the Springboks��� first Black captain, jogs over towards the section of the crowd occupied in large part by the Gwijo squad ��� an ever-growing legion of Springbok fans, led by black South Africans, who bring African songs of struggle and victory to the sport of rugby. Along with teammates Mapimpi, Trevor Nyakane, Bongi Mbonambi, Sbu Nkosi, Aphiwe Dyantyi, Lizo Gqoboka and Bok backline coach Mzwandile Stick, Siya joins the Gwijo squad in song. To Nyakane���s left stands Loodt de Jager, one of the Springbok���s four white Afrikaner locks and the lone white player to head over to the Gwijo squad. He (probably) doesn���t know the words of the song, but he claps along.

October 30, 2019

The people’s movement in Algeria, eight months on

2019 protest in Algeria. Image credit Khirani Said via Wikimedia Commons.

Within seven weeks of its start on February 22nd, 2019, the people���s revolt (Harak) in Algeria forced the cancelation of the presidential elections scheduled for mid-April and shook the then teetering power equilibrium to its core. The militaro-oligarchic tripod, composed of the Presidency, Military High Command (MHC), Intelligence, and their respective foreign patronage and clientelist networks, which had carefully been crafted over the previous three decades, was dealt a significant blow by a peaceful but determined people���s movement. Yet despite these gains, the movement has been struggling against a three-dimensional counter-revolutionary constellation bent on aborting the potential of the movement and reproducing the system under a new guise.

On April 2nd, riding the popular wave, the MHC made its move against President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, promising a power handover to appease the movement. Next, they went for the head of intelligence, Athman Tartag, bringing his security apparatus under its command and assuming total control of decision-making mechanisms in the country. In all but name, it was a coup d�����tat.

A wave of arrests ensued in the following weeks targeting former (prime) ministers, corrupt businessmen, political figures, and military/intelligence officers associated with the disgraced wings who might possess the capability to cause nuisance. The MHC hoped that the spectacular manner in which this settling of old accounts campaign was carried out and represented, would help to appease the people���s movement. It would demonstrate the seriousness with which the MHC approached the cleansing of “corruption” and the influence of “unconstitutional forces” within the state. Algerians, however, were not easily swayed by this performance of self-mutilation, in which the military-oligarchic cabal hacked some of its limbs to save its nervous system.

Bouteflika���s removal, and the jailing of his brother, Said, who was assumed to be the actual power behind the office for the last 6 years, automatically triggered the relevant constitutional transitional mechanisms. Most importantly, Article 102 allows for the interim head of state and interim government to organize presidential elections within a period of 90 days. Recognizing the MHC���s agenda- to use the elections (scheduled for July 4th) as a front to assure its own primacy, the Harak���s slogans on the street mutated to reflect the new stakes. The new slogans included ���Yetnehaw Ga���a”��(They must all be wrenched, “Makach intikhabat maa al-issabat“��(There won���t be any elections with these cabals), ���Dawla Madaniyya, Machi Askariyya” (A Civilian, not a Military State), and ���Jumhuriyya machi caserna/thakana” (This is a republic, not a barracks).

Having ensured the cancelation of the July 4th elections, the popular movement goaded the MHC into its nightmare scenario, a constitutional crisis. The MHC���s attempts to turn a political crisis into a constitutional one failed miserably. With the expiry of the 90 days period in early July, neither the interim presidency nor the interim government could claim any shred of legitimacy, even in the eyes of the most accommodating elements of the popular movement. As far as the movement was concerned, even by the standard of the ruling cabal���s constitution, the country had entered a period of de facto rule by the MHC. Although Algerians have always been aware of the centrality of the MHC to the country���s power constellation, it had always managed to shroud itself in a civilian fa��ade to mystify its role in the country���s decision-making process. For the first time since independence, however, the MHC finds itself in a direct face-off with the people and, this time, there is nowhere for it to hide.

The MHC has turned its back on every single roadmap proposed by actors with an actual social base and presence in the movement, and have ignored all appeals for a genuine dialogue. This includes the National Coordination for Change in Algeria���s Platform for Change in Algeria��in March, followed by propositions and appeals made in May and June by the National Organization of Veterans, the National Association of Ulama, the National Civil Society Conference, the Forces for a Democratic Alternative, as well as the multiple appeals and statements issued by various groups of independent national personalities.

By late June, realizing that the July 4th elections were a chimera, the MHC began a more concerted campaign of repression, this time targeting historical symbols and leaders of the movement. The counter-revolution revealed its ugly face���not only with its repressive security apparatuses on the streets, but also with its increasing assaults through the media. All audiovisual and most print media, public and private, were tamed. Not a single Algeria-based TV channel has covered the protests or the demands being made by the millions of Algerians on the streets. Social media campaigns led by an electronic army of trolls (humans and bots), operating from Algeria, Egypt, UAE and elsewhere, have worked around the clock to spread disinformation, fake news and pro-MHC propaganda. They work to stifle oppositional Twitter accounts and Facebook pages, and to defame and tarnish the reputation of historical symbols and popular opposition figures, etc.

Holding the people���s unity to be a red line, the Harak humored the least radical segment within it and accompanied it on its journey to discovering the impossibility of redeeming certain elements within the MHC. It became crystal clear to anyone involved that certain generals, along with their civilian and business counterparts, were hopeless. Their long, obedient and loyal service to the putschists and criminals of the 1990s, their total submission and active complicity in the plunder of the country in the 2000s and 2010s, their complete capitulation to foreign powers with jurisdiction over their ill-gotten assets, and their “treasonous” acts in surrendering national sovereignty and subservience to imperialist and neo-colonial designs on the continent���these are only a few of the reasons that prevent MHC from now claiming the vocation of ���serving the people��� with any legitimacy.

Ostensibly adopting as its motto Einstein���s definition of insanity���doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results���the MHC directed a simulacrum of dialogue with Algeria���s D-list of political actors closely linked to the oligarchy. It appointed an “independent” electoral commission, amending the electoral law and setting December 12th, 2019 as the date for presidential elections. Such provocations galvanized the popular movement even more, mobilizing new sections of society. By mid-October, the numbers on the street regained the levels of March and April. Slogans targeting the MHC and specifically the Army Chief of Staff (Ahmed Gaid Salah) became common currency, e.g. ���Generals to the trash bin, and Algeria will be independent,��� ���Gaid Salah, the UAE���s shoe-shiner,��� ���Release our children [political prisoners] and jail Gaid���s Children.���

The movement has been masterful in defusing every single boobytrap sown by status quo forces. The Harak has consistently insisted that the only lines of division are horizontal (governors/governed and haves/have nots) and not vertical as the oligarchy wants Algerians to believe (Islamist/secularist, Arabophone/Berberophone, men/women, etc). It is of the utmost importance to examine the hostile context in which a people���s revolution is unfolding and the ways in which counter-revolutionary forces labor tirelessly to crush the Algerian people���s resolve.

A 3D counter-revolution

The efforts of the global-regional-local constellation of counter-revolutionary forces working to abort the people���s revolt in Algeria are practically the same as those working towards similar ends on the continent and elsewhere in the world. These efforts are inscribed in the much larger and longer project designed to empty the mid-20th century global decolonization process of its liberatory and emancipatory content, and to lay the foundations for a neocolonial/imperialist/racial-capitalist world order.

Over the last three decades, scholarship on Algeria dealing with the long decade (1988-1999) has rightly diagnosed the foundational importance of this period. However, the attempts at understating developments through the categories of failed states, civil wars, ethnic, sectarian and religious conflict���hegemonic post-Cold War framings of Global South political violence���have done more to distort the picture than to clarify it. This tendency has, intentionally or otherwise, served as a conduit for official narratives of this pivotal period in Algeria���s and world history. They have helped to reify these narratives to the detriment of more wholistic accounts that incorporate social, economic and political trends and dynamics on the local, regional, and global levels alike.

As we have argued elsewhere, approaching this foundational moment/period as an enclosure process, a form of (primitive) accumulation through dispossession, and ultimately a conjuncture that the neocolonial project capitalized on to make inroads in spaces that had been previously liberated in the process of anti-colonial struggle through a shock therapy. Such an approach allows us to better grasp the stakes involved, the influential actors on the scene, as well as affords us a finer appreciation of the root causes of the current people���s revolt and greater intelligibility of recent developments and likely future trajectories.

The past three decades and the post 2011 regional experience has taught us that while people���s uprisings terrify imperialist powers and transnational capital, the latter also sees them as conjunctures with opportunities to extract more concessions from their local military-oligarchic vassals. The power calculus and interest prioritization of imperialist actors is three-fold: deepening, preservation, or damage limitation as the worst-case scenario. It is no coincidence, for example, that the trade agreement the EU has been trying to shove down Tunisia���s throat since the 2010-11 revolt is entitled ���Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement.”

The counter-revolutionary campaign currently underway in and on Algeria is driven by a constellation of local, regional, and inter/transnational state and corporate actors. Locally, elements within the MHC and their national business proxies, sections of the business elite who had lost their military and intelligence patrons but managed to replace them with foreign power patronage, and disgruntled sections of both that had been pushed into exile remain, despite their differences, were adamantly opposed to any genuine change. Globally, the US, Canada, and France along with the major oil, media, and tech corporations have played an especially noxious role. Regionally, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt as the subcontractors of imperialism and zionism, have thrown their weight to crush any liberatory and emancipatory impulses in large parts of Africa and West Asia.

Additionally, the counter-revolution seeks to break the movement, solidify and deepen where possible its influence, or at least create “facts on the ground” that would shackle and make it impossible for a potential revolutionary government coming to power to act with any real sovereignty. The two strategies are employed concomitantly and function on the material as well as ideational planes.

The increasing military repression of the movement has been accompanied by a campaign of defamation against war of liberation martyrs such as Ali la Pointe and living heroes like Djamila Bouhired and Lakhdar Bouragaa. The latter has been in detention for the last four months for ���contempt towards a constitutional body [army] and undermining the army���s morale,��� an elastic charge that has been applied liberally to silence opposition to military rule. Aided by intelligence operated local troll farms and their Gulf and Egyptian counterparts, massive campaigns of disinformation aimed at creating divisions in the movement along ideological and cultural lines, promoting the MHC���s electoral agenda and ceaselessly spewing pro-military propaganda have saturated the social media sphere. Facebook, with its regional headquarters in the UAE, has closed hundreds of accounts and pages belonging to political activists and opposition figures engaged in the movement. The connections between military oligarchies in the region, Gulf states and capital, social media giants and western militaries has been amply established.

Gulf and Egyptian owned satellite media along with their Algerian counterparts have neither (adequately) covered the movement nor allowed for dissident voices to be heard. There has been an equally eerie silence in Canada, the UK, the US, and France. Unlike the incessant coverage of the Hong Kong protest movement, there has been an almost radio silence on struggles in Algeria or Haiti, undoubtedly for their anti-imperialist orientations.

There has also been European complicity in the silencing of alternative voices within the Algerian media sphere. Just this past week, within the space of two days, the Paris-based European satellite provider Eutelsat, at the request of the Algerian government, pulled the plug on two independent Algerian TV channels (Al Magharibia and Hirak TV), which had been providing full coverage for the people���s movement. It is the same Eutelsat that pulled the plug on the oppositional Al-Asr TV in June 2011, hours before it was supposed to go live. Activists involved in the popular movement are convinced that such a decision could not have been taken without the complicity of the French political establishment.

The official French support for the Algerian militaro-oligarchic junta goes back decades. The support for Bouteflika remained unwavering since the beginning of his reign, and went so far that the former French president looked the world and Algerians straight in the eye in mid-June 2015, and bore false witness to Bouteflika���s good health. France backed Bouteflika���s fifth term, threw its weight behind his initial plan to bestow upon himself an additional year to his fourth term, and has since made apparent its, and the EU���s support for the MHC���s program to exit the current crisis by organizing elections that are categorically rejected by the millions on the streets.

The French oil giant Total has taken advantage of the current moment to declare its takeover of the American Anadarko portfolio in Africa, which include its assets in Algeria. A takeover that effectively gives it control of a large part of oil production in Algeria. The timing and manner in which the acquisition has been undertaken with total disregard for the country���s laws regulating such transactions are clear signs that the takeover is meant to increase French influence over decision-making processes in the country.

Total has not been alone in its efforts to secure influence while the focus of Algerians is elsewhere. The illegitimate minister of energy recently declared that the proposed hydrocarbons law was devised after ���direct negotiations with the five oil majors,��� including ExxonMobil and Chevron. The law will allow oil corporations to secure long-term concessions, expatriate proceeds, absolve them from any tax responsibilities and transfers of technology. The movement has been unanimous in opposing this proposed law and brandished the current illegitimate rulers as traitors��in the protests that followed the announcement.

In addition to the new energy law there has been the budget law of 2020, which is set to reopen the door for international borrowing, and institute harsh austerity measures by lifting subsidies on electricity and diesel and subjecting consumers to international market prices. This would��increase taxes on the most vulnerable classes while exempting multinational from tariffs and taxes. Added to these are the host of proposed bills that have been tabled and are being pushed through, designed to administer yet another dose of shock therapy to a people in revolt. These proposed bills are set to deepen and accelerate the liberalization process began three decades ago. In doing so, they will mortgage the country���s natural resources and further surrender the people���s sovereignty in the name of creating a better investment and business climate.

The proposed amendments to the code of penal procedures is set to entrench the security state by giving the “judicial police” wide powers and freeing it from the shackles (judicial warrants) of the justice system. This very judicial police had been annexed to the MoD in mid-June and has been instrumental in the campaign of repression the country has seen since then.

The current illegitimate government has also put in place commissions to reform the retirement system. These commissions are charged with studying the feasibility of pushing retirement age from 60 to 65 year, reducing the pension rates from 80% to 60%, reducing the pension calculation index from 2.5 to 2.3, and stretching the calculation base of annuities to cover the last 10 years of service instead of the current 5 years. In short, the junta is prepared to continue performing and deepening its role as a conveyor belt for northbound wealth transfers, the dispossession of Algerians, and the endangerment of national security and regional stability.

Meanwhile, the wealth drain represented by international money laundering out of Algeria continues unabated. Canadian government statistics indicate that the first half of 2019 saw a 50% increase of capital transfers from Algeria to Canada. Not a surprise given that the same government continued to supply arms and ammunition to Algeria five months into the people���s revolt with the latest deals concluded in June and July of this year. Canadian capital is no exception to the rule. SNC-Lavalin’s criminal track record in Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria has recently galvanized the Algerian community in Quebec to stage protests in front of it its headquarters.

The US has equally signaled its support for this de facto military rule and has used the current conjuncture to extract the maximum concessions possible. The last three months (August-October) have witnessed frantic US activity in Algeria. The arrival of a high level military delegation in early August, was followed by the State Department reception of the illegitimate culture minister in Washington DC and the signature of a Memorandum of Understanding on Cultural Property Protection. This is a move that not only signals the US’s willingness to deal with an illegitimate government, but also its push for the country���s further integration in a globalizing intellectual property regime without the consent of the Algerian people.

September was the reserve of economic interests. Representatives of��Chevron were in Algiers exploring “areas of potential partnership” with the opaque National Agency for the Valorization of Resources and Hydrocarbons (ALNAFT). That same week ALNAFT signed a partnership agreement with ExxonMobil for the ���evaluation of oil and gas potential��� in the Sahara basin, making ExxonMobil the fourth oil corporation to have a horse in the race after the Italian ENI, the French Total, and the Norwegian Equinor. The presence of these oil giants in the country is tightly linked to the negotiations over the proposed Hydrocarbons Law as the MHC energy minister has declared.

In early October, a congressional delegation led by Rep. Stephen F. Lynch (of Massachusetts 8th Congressional District) visited Algeria to discuss ���efforts to promote economic cooperation, combat terrorism, and enhance security in the region, and other areas of bilateral cooperation.��� Given his hawkish track record on US imperialist aggression in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere, as well as the highly sensitive timing of the visit, Algerians view these efforts as direct interventions in the internal politics of the country. The movement���s slogans have demonstrated its unanimity in refusing and condemning all forms of foreign meddling.

Counter-revolutionary narratives

In the midst of its intensification of cultural and exchange programs, the US Embassy in Algiers announced this past August its sponsoring of an Apprentice-like TV show ironically entitled I Have A Dream, featuring oligarchic figures as judges, and in which young entrepreneurs battle it out for a sum of $5000. The show is set to be aired on Echourouk TV, which has been the mouthpiece of the military chief of staff and observed a total blackout on the people���s movement since April.

The European intervention at the level of shaping perceptions and narratives also focused on normalizing neoliberal ethos and promoting a racial colonial telos as an aspiration. ARTE, the Franco-German Television Network focusing on cultural programing, aired a program, entitled Algeria: The Big Waste��explaining the historical and political causes of the country���s stagnation and potential futures. The title���s colonial undertones and its inscription in a Lockean discursive tradition of under-utilization and improvement are telling. Cloaking itself in scholarly expertise, the program opines that amongst the main causes of this stagnation are the over-involvement of the state in economic matters, an un-friendly climate for foreign investment, and a restrictive visa regime for foreigners���read Europeans to enter the country freely. The solutions to “The Big Waste,��� it follows, are none other than: less state and more free-market, a liberalization of the investment code for foreign capital especially in the tourism sector, and the jettisoning of the principle of diplomatic reciprocity underpinning the visa regime to allow freer (European) movement into the country. In short, the fulfillment of Algeria���s potential, viewers are told, lies in its imitation of Tunisia and Morocco.

In October, ARTE aired yet another reportage entitled Algeria: Youth in Revolt, which essentially paints the movement as having ended with Bouteflika���s ouster. Ignoring the clear demands of the millions still occupying the streets week in and week out, and the popular movement���s refusal of any election under the auspices of the MHC and the current conditions, the reportage presents the MHC electoral roadmap for 12/12/2019 as a fait accompli. It ends with an outright distortion of the people���s will, claiming that the youth has high hopes for these elections. Such narratives ignore the slogans of the protestors, including the latest: ���Degage Gaid Salah, hedh el���am makach el vote”��(Get out Gaid Salah���There won���t be any elections this year), and their explicit refusal to see that these elections will provide a cover for the repression of the movement.

The French cultural establishment���s involvement, however, does not only focus on liberal proselytizing. Consistent with its racist and Islamophobic tenets, it continues to evoke the “Islamist threat.” A centerpiece of the military-oligarchic junta���s psychological warfare on Algerians since this 1990s, the French state, media, intellectual, artistic, and cultural circles have been accomplices in perpetuating this narrative over the last three decades. The above program, for example, does not even recognize the 1992 coup d’��tat as a coup. Similarly, another program by the same networks, entitled Algeria: the Promises of Dawn��aired in early July urges vigilance of the Islamist threat lurking in the background of the popular movement, and paints the movement as misogynist based on an isolated incident largely believed to be the work of provocateurs.

The Film Festival in Cannes did not lag either in reinforcing these themes. The selections of two Franco-Algerian movies Abu Leila and Papicha, both of which deal with the 1990s and reify the official narrative of the Civil War, is hardly a coincidence. While the former enjoyed two nominations at Cannes and the award for Best European Fantastic Feature Film��in Neuch��tel, Papicha received four international nominations, an award, and much more media hype. The official refusal to allow its screening in Algiers, many suspect, is a backhanded shoring up of legitimacy for the film after the negative reviews it received from non-Francophone critics describing the film���s ���loosely inspired by real events��� tagline as ���conspicuously manipulative.���

Looking ahead ���

Despite these colossal odds, the movement continues to grow and draw new sections of society into the equation. With lawyers starting to make their presence felt, the independent trade unions preparing to launch a general strike by the end of October, judges observing a general strike, and the heroic stands and statements of political prisoners such as Bouregaa re-centering the movement���s compass; the movement still lives its best days.

The 65th anniversary of the declaration of the War of Liberation against French colonialism on November 1st coincides with a Friday this year. Given the movement���s unshaken resolve and iron steadfastness, the mobilization promises to be legendary. November 1st, 2019 will be a turning point for the movement. The Harak will enter the phase of civil resistance.

The disdain and contempt have changed camps over the last several months. Aware that the plunder of the country���s resources has reached mythical proportions, conscious of the MHC���s and its head���s complicity in France���s recolonization of Mali, as well as the opening up Algeria���s airspace for French and American drones to collect intelligence, and, in the case of the latter, use Algerian military installations; Algerians��� scorn for the current rulers is only comparable to their disdain for the Harkis during colonial times. Surrendering national sovereignty to foreign governments and multinationals rather than the Algerian people in revolt have dispelled any illusions Algerians had of the treasonous character of their rulers, and the absolute necessity for their removal.

Defying historical necessity, the current MHC seems unable to grasp that Algerians will no longer, and under no circumstances acquiesce to the supremacy of the military command over civilians in political life. If the thesis of militarized colonial rule occasioned the anti-thesis of armed liberation struggle resulting in a synthesis of a militarized “post-colonial” coloniality; then the people���s movement���s exemplary peacefulness and civility is the very antithesis of this neocolonial thesis. It is time for these militaro-oligarchic cabals and their foreign backers to understand that their fight is not only with the Algerian people, but also with History.

October 29, 2019

Burkina Faso: Nothing will be as it was before

Place Nations Unies, Ouagadougou. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

A few years after the Jasmine Revolutions had shaken up North African countries, events came to a boil south of the Sahara in Burkina Faso. On October 31, 2014, massive street protests toppled President Blaise Compaor�� who was in power for 27 years. Revolutions, uprisings or insurrections, whatever label you give them, tend to be presented as clear-cut turning points in history books, but the truth is that the first few years after such upheavals are often confused, complex, and sometimes downright demoralizing. It is still not clear how the outcome of the 2014 Burkina Faso insurrection will go down in history books���indeed, there is not yet even consensus on how the events should be referred to, though with time, the term ���insurrection��� has come to displace the term ���revolution.��� Awaiting the clarity of hindsight, here is a look back through the eyes of an ordinary bystander to the extraordinary events that occurred at the end of October five years ago.

Those October days

October 21, 2014: In anticipation of the November 2015 elections, Compaor��, who has governed Burkina Faso since ousting Thomas Sankara in a coup d�����tat in 1987, announces that parliament will vote on changing Article 37 of the constitution to remove the current limit on presidential terms. This would enable him to run for elections as incumbent for a fifth time, so it elicits very strong responses from opposition political parties and civil society groups. Going through parliament is a new tactic for the president, who up until this point had talked of holding a general referendum on the amendment���a two-thirds majority in parliament would allow him to avoid the referendum altogether. This is a bit of a surprise blow and provocation to those who had been mobilizing against a referendum for several months already. It smells of a ruse.

October 21-27, 2014: Civil society and youth groups organize spontaneous small-scale demonstrations to warn the government of the unacceptability of what it is trying to do. At rush hour, several main arteries in Ouagadougou, and other towns, are blocked by youth burning tires, inciting people to join the mass demonstration called for by opposition parties on October 28. In the meantime, some members of the ruling party, CDP, are making incendiary comments such as: ���Blaise will run in the 2015 elections, in the 2020 elections, and as for 2025, we will see.��� (Compaor�� being a common last name in Burkina, locally the president is almost always referred to by his first name).

On Saturday October 25, our whole family, toddler included, goes to one of the most vibrant theater festivals in West Africa, Recreatrales, which is being held in this tumultuous, yet still peaceful time. The main event that night is a dance show called ���Nuit blanche �� Ouaga��� (Sleepless Night in Ouaga). It���s a jerky frenetic choreography by Serge Aim�� Coulibaly about a revolution in a city somewhere in Africa. It features the rapper Smockey, who is the key figure behind the civil society group��Le Balai Citoyen��(The Citizen Broom) that would play an instrumental role in the uprising. Our toddler is a bit frightened by the violent dancing, while his elder brother is enraptured and spends the next week trying to recreate the moves. My husband and I debate on how prophetic the piece is: “No, surely Blaise will read the clear signs, and annul the constitutional amendment.”

October 27, 2014: In anticipation of Tuesday���s mass demonstration called for by opposition leaders, the women of Ouagadougou take to the streets in a colorful, peaceful demonstration. They brandish huge traditional wooden spoons used to prepare the national dish, t��.��When women leave the household with their spoons, it means there is trouble. Furthermore, a lot of the women in the march are elderly, yet another signifier to the level of frustration being expressed���you have gotten grandmothers out of their chairs and yards!

October 28, 2014: Ouagadougou and towns across Burkina Faso come to a standstill as there is historic participation in mass demonstrations against the constitutional amendment. Starting in the early morning hours, from our neighborhood we can hear the demonstrators marching to city center about 5 km away. They are blowing on whistles. Whistling, like in football matches, is a popular part of the demonstrations���giving Blaise a red card, or telling him the game is over. Several demonstrators brandish banners equating Blaise with the Ebola epidemic that our West African neighbors are busy trying to kick out. Opposition parties claim that one million people participate in the Ouagadougou demonstration, which is about half the population of the city.

Demonstrators in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina���s second biggest town, pull down a bronze statue of Blaise. He is standing next to Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi (it was erected several years ago to celebrate Burkina���s friendship with Libya). They take care not to touch a proverbial hair on Gaddafi���s statue to make it clear whom they have a problem with.

October 29, 2014: Ouagadougou comes back to life and people get on with their daily occupations. It is the day of the scheduled vote and the government announces that the time of the vote tomorrow has been pushed forward from 4pm to 10am. Azalai Hotel, strategically located just behind the parliament, vehemently denies that it is housing ruling party members ahead of the contested vote.

Despite the denials, everyone knows that the MPs are indeed at the five-star hotel and that a door has been opened up between the hotel and parliament so that the MPs do not have to step out into the street to get to their voting chamber. A Burkinabe journalist would later win the CNN Multichoice Best Journalist award for his report on the night he spent with the holed-up MPs at the hotel. Some MPs were terrified, some voiced doubts about whether it was right to hold the vote, and others focused on making the most of the government���s largesse, wining and dining to the hilt. There are also rumors, this time denied by the government, that mercenary troops from Togo have been brought in to counter demonstrators on the day of the vote.

That night, from 11pm, we start to hear demonstrators marching past our neighborhood to the city center. This continues all night until morning hours. Those that we see are young, some still looking like teenagers. The economist, Ra-sabgla Ouedraogo later noted that almost 60% of Burkina���s population was born under Blaise Compaore���s 27-year reign; it would be these ���children of Blaise��� whom would control his fate in the coming days.

October 30, 2014: Holed up safely at home, we follow events on radio, television, and social media. From 8:00am the mass of demonstrators is pushing forward against security forces to get into the Nation Square, that a few hours later people would start calling again by its Thomas Sankara-era name ���Revolution Square.��� Elements of the security forces are sympathetic to the demonstrators; there are stories of armed forces giving demonstrators tips on how to neutralize tear gas or how to get around the barricades. But there are also violent clashes. Images of ordinary citizens taking risks go viral. Of those that achieved particular fame was the photo of a 27-year old engineering student, who later told journalists that he woke up that morning with no fear of dying, saying, ���I had unusual courage.��� He donned a shirt on which he had scrawled ���Shoot at me!��� followed by Burkina Faso���s motto, ���Homeland or death, victory will be ours!��� unchanged since Sankara���s time. Another memorable image is of a man, in his forties, standing defiantly as two helmeted and bullet-proof vested soldiers prepare to beat him with a large tree branch. It later emerged that he was a tax inspector. I kept thinking he bore a striking resemblance to the mild-mannered and very helpful tax clerk who had provided me with all the necessary information for getting my new tax number a few months prior.

By 9:30am demonstrators have managed to push through to the House of Parliament. They sing the national anthem and then proceed to set the parliament on fire. Honorable MPs flee helter-skelter, some stealing clothes from housecleaning to disguise themselves. At this point, there are rumors that Blaise had fled to Ivory Coast the previous night. I think to myself, ���Thank God, he finally he came to his senses.��� Unfortunately, this is not the case; Blaise is still not reading things clearly. After some weak declarations from his ministers rescheduling the constitutional review and total silence from Blaise himself, the mass demonstration, initially against just the constitutional amendment, has galvanized into a movement to get rid of the president once and for all. Mid-morning, the leader of the opposition is heckled by the crowds during a press conference for his timid ambitions focused on the annulment of the constitutional review, until he finally calls for Blaise to step down.

In our neighborhood, we pick up news through the grapevine of young demonstrators coming back home to recharge their batteries. We continue listening to the radio; local stations are blasting evocative songs such as Tikken Jah Fakoly���s ���Quitte le pouvoir��� (Leave power) in between their news bulletins.

For several hours more there is complete silence from the presidential camp and confusion reigns as to who is in charge of the country. The French international news channel France 24 stuns with its partiality, incompetence, or just pure laziness in reporting on events. It rushes to call ���coup d�����tat��� what other media outlets are calling insurrection, uprising, or mass demonstrations.

On Thursday night, Burkina Faso goes to sleep after Blaise finally breaks his silence, not to resign, but to announce a state of emergency. In French the unfortunate term is literally ���a state of siege.���

“Siege? Who is under siege? Us or him?!” many Burkinabe ponder, aggravated by this poor choice of words.

October 31, 2014: Demonstrators amass again in Revolution Square, calling for Blaise���s resignation. Finally, at around lunch time the long-awaited announcement of Blaise vacating the presidency is made on a private television station. Hours of confusion follow and after several back-and-forths, an army man, Lt. Col. Zida takes power and announces the instauration of a transitional government within a few weeks.

There is widespread jubilation at the news of Blaise stepping down, but celebrations are quietly cautious because: 1) a 7:00pm curfew is still in place, and 2) there is widespread mistrust of the army which has taken power. A few days later, our supermarket attendant would lament the painful joy of that day, ���Imagine, you have just been given Christmas and New Year���s rolled in one, and you can���t even go to a bar, you have to go home at 7:00!���

Simon Compaor��, Ouagadougou���s former mayor and long-time ally of Blaise, who defected to the opposition at the beginning of the year, calls for Operation Mana-mana��to clean up Ouagadougou from the debris of days of demonstrations starting at 5:00am Saturday morning. The name ���mana-mana��� is a reference to obligatory clean-up operations that communities had to participate in during the Sankara era to keep their neighborhoods clean.

November 1, 2014: A surprising number of people, mostly youths, report present for Operation Mana-mana and by lunch-time, when we decide to venture into town to finally see with our eyes the scene of the recent historic events, the streets of Ouagadougou are clean. Gone are the burnt tires, the broken glass, and the rubble. The Ouagadougou of that moment presents a strange map of completely ransacked, sometimes burnt buildings, next to buildings completely intact. The lootings that international media kept reporting on, without further explanation, were for the most part targeted: the parliament where the vote was to take place, the hotel that housed the MPs (several in the crowd of demonstrators allegedly tried to dissuade against this), the headquarters of Blaise���s ruling party. They also targeted houses, businesses and property belonging to Blaise���s widely despised brother Fran��ois Compaor�� and his mother-in-law Alizeta Ouedraogo, both of whom were believed to have strangleholds on most of Burkina Faso���s economy, as well as the property of other regime cronies considered to have played a key role in pushing for the constitutional amendment, or to have amassed riches through mass fraud and corruption. The looting also had a very pragmatic character to it. To ensure the total destruction of what were considered ill-gotten goods and thus send a clear message to alleged perpetrators of economic crimes. Property of the former governing elite was burned. But before setting the properties ablaze, anything useful that could be recycled was removed. Thus, on this day, houses are completely gutted���their window frames stripped, doors unhinged, even electrical wiring removed. A friend who had been active on the streets the past two days told us how mechanics had followed demonstrators around, pleading with them to wait a few minutes before setting luxury cars ablaze, so that they could remove batteries, tires, and other valuable spare parts.

On the streets, vendors sell photocopies of documents found in Fran��ois Compaor�����s house, which had become a sort of sinister museum. Blaise���s younger brother was implicated in several crimes, the most notorious being the assassination of journalist Norbert Zongo in 1997, and was regarded by many ordinary Burkinabe as a massively corrupt figure. A few years previously, when Blaise and his allies had started insinuating that Fran��ois could be the presidential candidate in 2015, it quickly became clear that this would not be accepted. A few months later, talk of amending the constitution started.

Impromptu parking attendants, seeing opportunity, briskly organize the parking of hundreds of motorcycles and bicycles of curious by-passers. Burkinabe want to see for themselves what Fran��ois did with the wealth he amassed and whether the widespread reports of discoveries of all kinds of strange paraphernalia, and a basement with blood-stained walls were true. A few days later a��statement released, supposedly by Fran��ois Compaor�����s family, claims Fran��ois���s daughter did her art homework in the basement, thus explaining what looked like blood stains on the wall. The documents being hawked on the streets include alleged secret police reports on the assassinated journalist Norbert Zongo, lists of houses being shared out by the regime to influential figures, and photos of witchcraft practices.

November 3, 2014: Life regains a sense of normality; people go to work, children go to school, and everyone seems to have a story to tell about the events of the past few days.

November 16, 2014: Lt Col Zida, the provisional head of state, signs the transitional charter organizing the transitional period until elections planned scheduled for October 2015. In his speech handing over power to the transitional president, Michel Kafando, he makes several references to the Sankara era and brings tears of emotion to the eyes of many. Zida is appointed Prime Minister of the transition.

Official ceremonies would later be organized in homage to the 24 people who lost their lives and the hundreds injured during the insurrection.

Life goes on, post-insurrection

���Nothing will be as it was before��� was the refrain in the immediate days after the insurrection. This has not quite proven true. Prime Minister Zida became a controversial figure, believed by some to be embroiled in corruption himself. In September 2015, as Burkina prepared for the elections to end the transitional period, a military putsch led by General Diender��, Blaise���s right-hand man, occurred. This event, aptly summed up on a demonstrator���s sign as ���the stupidest coup in the world,��� incited another extraordinary wave of determined collective action. People took to the streets, an underground resistance radio station was set up, the Twittersphere was filled with revolutionary haikus to incite resistance. The army, after a brief period of indecision, showed a great sense of civic duty and protected civilians, taking decisive action to end the coup. The coup was swiftly countered, and the perpetrator of the military coup ended up apologizing, followed by the streets being cleaned again. And unfortunately, another dozen deaths were mourned.

Elections were held peacefully in November 2015, and in January 2016, Burkina Faso suffered its first large-scale terrorist attack on its soil, a harbinger of one of the most trying moments in Burkina Faso���s history. Today, terrorism has become deeply entrenched in certain regions of Burkina Faso, straining the country���s legendary inter-religious and inter-ethnic tolerance and generally sapping morale, all the more so because there is no clear understanding of what exactly is behind the wave of terrorist attacks. Faced with a much more diffuse and nebulous target than bringing down a president who overstayed, decisive collective action has been more difficult. But Burkinabe can at least remember that they have been capable of such action in the past.

Nothing will be as it was before

Place Nations Unies, Ouagadougou. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

A few years after the Jasmine Revolutions had shaken up North African countries, events came to a boil south of the Sahara in Burkina Faso. On October 31, 2014, massive street protests toppled President Blaise Compaor�� who was in power for 27 years. Revolutions, uprisings or insurrections, whatever label you give them, tend to be presented as clear-cut turning points in history books, but the truth is that the first few years after such upheavals are often confused, complex, and sometimes downright demoralizing. It is still not clear how the outcome of the 2014 Burkina Faso insurrection will go down in history books���indeed, there is not yet even consensus on how the events should be referred to, though with time, the term ���insurrection��� has come to displace the term ���revolution.��� Awaiting the clarity of hindsight, here is a look back through the eyes of an ordinary bystander to the extraordinary events that occurred at the end of October five years ago.

Those October days

October 21, 2014: In anticipation of the November 2015 elections, Compaor��, who has governed Burkina Faso since ousting Thomas Sankara in a coup d�����tat in 1987, announces that parliament will vote on changing Article 37 of the constitution to remove the current limit on presidential terms. This would enable him to run for elections as incumbent for a fifth time, so it elicits very strong responses from opposition political parties and civil society groups. Going through parliament is a new tactic for the president, who up until this point had talked of holding a general referendum on the amendment���a two-thirds majority in parliament would allow him to avoid the referendum altogether. This is a bit of a surprise blow and provocation to those who had been mobilizing against a referendum for several months already. It smells of a ruse.

October 21-27, 2014: Civil society and youth groups organize spontaneous small-scale demonstrations to warn the government of the unacceptability of what it is trying to do. At rush hour, several main arteries in Ouagadougou, and other towns, are blocked by youth burning tires, inciting people to join the mass demonstration called for by opposition parties on October 28. In the meantime, some members of the ruling party, CDP, are making incendiary comments such as: ���Blaise will run in the 2015 elections, in the 2020 elections, and as for 2025, we will see.��� (Compaor�� being a common last name in Burkina, locally the president is almost always referred to by his first name).

On Saturday October 25, our whole family, toddler included, goes to one of the most vibrant theater festivals in West Africa, Recreatrales, which is being held in this tumultuous, yet still peaceful time. The main event that night is a dance show called ���Nuit blanche �� Ouaga��� (Sleepless Night in Ouaga). It���s a jerky frenetic choreography by Serge Aim�� Coulibaly about a revolution in a city somewhere in Africa. It features the rapper Smockey, who is the key figure behind the civil society group��Le Balai Citoyen��(The Citizen Broom) that would play an instrumental role in the uprising. Our toddler is a bit frightened by the violent dancing, while his elder brother is enraptured and spends the next week trying to recreate the moves. My husband and I debate on how prophetic the piece is: “No, surely Blaise will read the clear signs, and annul the constitutional amendment.”

October 27, 2014: In anticipation of Tuesday���s mass demonstration called for by opposition leaders, the women of Ouagadougou take to the streets in a colorful, peaceful demonstration. They brandish huge traditional wooden spoons used to prepare the national dish, t��.��When women leave the household with their spoons, it means there is trouble. Furthermore, a lot of the women in the march are elderly, yet another signifier to the level of frustration being expressed���you have gotten grandmothers out of their chairs and yards!

October 28, 2014: Ouagadougou and towns across Burkina Faso come to a standstill as there is historic participation in mass demonstrations against the constitutional amendment. Starting in the early morning hours, from our neighborhood we can hear the demonstrators marching to city center about 5 km away. They are blowing on whistles. Whistling, like in football matches, is a popular part of the demonstrations���giving Blaise a red card, or telling him the game is over. Several demonstrators brandish banners equating Blaise with the Ebola epidemic that our West African neighbors are busy trying to kick out. Opposition parties claim that one million people participate in the Ouagadougou demonstration, which is about half the population of the city.

Demonstrators in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina���s second biggest town, pull down a bronze statue of Blaise. He is standing next to Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi (it was erected several years ago to celebrate Burkina���s friendship with Libya). They take care not to touch a proverbial hair on Gaddafi���s statue to make it clear whom they have a problem with.

October 29, 2014: Ouagadougou comes back to life and people get on with their daily occupations. It is the day of the scheduled vote and the government announces that the time of the vote has been pushed forward from 4pm to 10 am. Azalai Hotel, strategically located just behind the parliament, vehemently denies that it is housing ruling party members ahead of the contested vote.

Despite the denials, everyone knows that the MPs are indeed at the five-star hotel and that a door has been opened up between the hotel and parliament so that the MPs do not have to step out into the street to get to their voting chamber. A Burkinabe journalist would later win the CNN Multichoice Best Journalist award for his report on the night he spent with the holed-up MPs at the hotel. Some MPs were terrified, some voiced doubts about whether it was right to hold the vote, and others focused on making the most of the government���s largesse, wining and dining to the hilt. There are also rumors, this time denied by the government, that mercenary troops from Togo have been brought in to counter demonstrators on the day of the vote.

That night, from 11pm, we start to hear demonstrators marching past our neighborhood to the city center. This continues all night until morning hours. Those that we see are young, some still looking like teenagers. The economist, Ra-sabgla Ouedraogo later noted that almost 60% of Burkina���s population was born under Blaise Compaore���s 27-year reign; it would be these ���children of Blaise��� whom would control his fate in the coming days.

October 30, 2014: Holed up safely at home, we follow events on radio, television, and social media. From 8:00am the mass of demonstrators is pushing forward against security forces to get into the Nation Square, that a few hours later people would start calling again by its Thomas Sankara-era name ���Revolution Square.��� Elements of the security forces are sympathetic to the demonstrators; there are stories of armed forces giving demonstrators tips on how to neutralize tear gas or how to get around the barricades. But there are also violent clashes. Images of ordinary citizens taking risks go viral. Of those that achieved particular fame was the photo of a 27-year old engineering student, who later told journalists that he woke up that morning with no fear of dying, saying, ���I had unusual courage.��� He donned a shirt on which he had scrawled ���Shoot at me!��� followed by Burkina Faso���s motto, ���Homeland or death, victory will be ours!��� unchanged since Sankara���s time. Another memorable image is of a man, in his forties, standing defiantly as two helmeted and bullet-proof vested soldiers prepare to beat him with a large tree branch. It later emerged that he was a tax inspector. I kept thinking he bore a striking resemblance to the mild-mannered and very helpful tax clerk who had provided me with all the necessary information for getting my new tax number a few months prior.

By 9:30am demonstrators have managed to push through to the House of Parliament. They sing the national anthem and then proceed to set the parliament on fire. Honorable MPs flee helter-skelter, some stealing clothes from housecleaning to disguise themselves. At this point, there are rumors that Blaise had fled to Ivory Coast the previous night. I think to myself, ���Thank God, he finally he came to his senses.��� Unfortunately, this is not the case; Blaise is still not reading things clearly. After some weak declarations from his ministers rescheduling the constitutional review and total silence from Blaise himself, the mass demonstration, initially against just the constitutional amendment, has galvanized into a movement to get rid of the president once and for all. Mid-morning, the leader of the opposition is heckled by the crowds during a press conference for his timid ambitions focused on the annulment of the constitutional review, until he finally calls for Blaise to step down.

In our neighborhood, we pick up news through the grapevine of young demonstrators coming back home to recharge their batteries. We continue listening to the radio; local stations are blasting evocative songs such as Tikken Jah Fakoly���s ���Quitte le pouvoir��� (Leave power) in between their news bulletins.

For several hours more there is complete silence from the presidential camp and confusion reigns as to who is in charge of the country. The French international news channel France 24 stuns with its partiality, incompetence, or just pure laziness in reporting on events. It rushes to call ���coup d�����tat��� what other media outlets are calling insurrection, uprising, or mass demonstrations.

On Thursday night, Burkina Faso goes to sleep after Blaise finally breaks his silence, not to resign, but to announce a state of emergency. In French the unfortunate term is literally ���a state of siege.���

“Siege? Who is under siege? Us or him?!” many Burkinabe ponder, aggravated by this poor choice of words.

October 31, 2014: Demonstrators amass again in Revolution Square, calling for Blaise���s resignation. Finally, at around lunch time the long-awaited announcement of Blaise vacating the presidency is made on a private television station. Hours of confusion follow and after several back-and-forths, an army man, Lt. Col. Zida takes power and announces the instauration of a transitional government within a few weeks.

There is widespread jubilation at the news of Blaise stepping down, but celebrations are quietly cautious because: 1) a 7:00pm curfew is still in place, and 2) there is widespread mistrust of the army which has taken power. A few days later, our supermarket attendant would lament the painful joy of that day, ���Imagine, you have just been given Christmas and New Year���s rolled in one, and you can���t even go to a bar, you have to go home at 7:00!���

Simon Compaor��, Ouagadougou���s former mayor and long-time ally of Blaise, who defected to the opposition at the beginning of the year, calls for Operation Mana-mana��to clean up Ouagadougou from the debris of days of demonstrations starting at 5:00am Saturday morning. The name ���mana-mana��� is a reference to obligatory clean-up operations that communities had to participate in during the Sankara era to keep their neighborhoods clean.

November 1, 2014: A surprising number of people, mostly youths, report present for Operation Mana-mana and by lunch-time, when we decide to venture into town to finally see with our eyes the scene of the recent historic events, the streets of Ouagadougou are clean. Gone are the burnt tires, the broken glass, and the rubble. The Ouagadougou of that moment presents a strange map of completely ransacked, sometimes burnt buildings, next to buildings completely intact. The lootings that international media kept reporting on, without further explanation, were for the most part targeted: the parliament where the vote was to take place, the hotel that housed the MPs (several in the crowd of demonstrators allegedly tried to dissuade against this), the headquarters of Blaise���s ruling party. They also targeted houses, businesses and property belonging to Blaise���s widely despised brother Fran��ois Compaor�� and his mother-in-law Alizeta Ouedraogo, both of whom were believed to have strangleholds on most of Burkina Faso���s economy, as well as the property of other regime cronies considered to have played a key role in pushing for the constitutional amendment, or to have amassed riches through mass fraud and corruption. The looting also had a very pragmatic character to it. To ensure the total destruction of what were considered ill-gotten goods and thus send a clear message to alleged perpetrators of economic crimes. Property of the former governing elite was burned, but before setting the properties ablaze, anything useful that could be recycled was removed. Thus, on this day, houses are completely gutted���their window frames stripped, doors unhinged, even electrical wiring removed. A friend who had been active on the streets the past two days told us how mechanics had followed demonstrators around, pleading with them to wait a few minutes before setting luxury cars ablaze, so that they could remove batteries, tires, and other valuable spare parts.

On the streets, vendors sell photocopies of documents found in Fran��ois Compaor�����s house, which had become a sort of sinister museum. Blaise���s younger brother was implicated in several crimes, the most notorious being the assassination of journalist Norbert Zongo in 1997, and was regarded by many ordinary Burkinabe as a massively corrupt figure. A few years previously, when Blaise and his allies had started insinuating that Fran��ois could be the presidential candidate in 2015, it quickly became clear that this would not be accepted. A few months later, talk of amending the constitution started.

Impromptu parking attendants, seeing opportunity, briskly organize the parking of hundreds of motorcycles and bicycles of curious by-passers. Burkinabe want to see for themselves what Fran��ois did with the wealth he amassed and whether the widespread reports of discoveries of all kinds of strange paraphernalia, and a basement with blood-stained walls were true. A few days later a��statement released, supposedly by Fran��ois Compaor�����s family, claims Fran��ois���s daughter did her art homework in the basement, thus explaining what looked like blood stains on the wall. The documents being hawked on the streets include alleged secret police reports on the assassinated journalist Norbert Zongo, lists of houses being shared out by the regime to influential figures, and photos of witchcraft practices.

November 3, 2014: Life regains a sense of normality; people go to work, children go to school, and everyone seems to have a story to tell about the events of the past few days.

November 16, 2014: Lt Col Zida, the provisional head of state, signs the transitional charter organizing the transitional period until elections planned scheduled for October 2015. In his speech handing over power to the transitional president, Michel Kafando, he makes several references to the Sankara era and brings tears of emotion to the eyes of many. Zida is appointed Prime Minister of the transition.

Official ceremonies would later be organized in homage to the 24 people who lost their lives and the hundreds injured during the insurrection.

Life goes on, post-insurrection

���Nothing will be as it was before��� was the refrain in the immediate days after the insurrection. This has not quite proven true. Prime Minister Zida became a controversial figure, believed by some to be embroiled in corruption himself. In September 2015, as Burkina prepared for the elections to end the transitional period, a military putsch led by General Diender��, Blaise���s right-hand man, occurred. This event, aptly summed up on a demonstrator���s sign as ���the stupidest coup in the world,��� incited another extraordinary wave of determined collective action. People took to the streets, an underground resistance radio station was set up, the Twittersphere was filled with revolutionary haikus to incite resistance. The army, after a brief period of indecision, showed a great sense of civic duty and protected civilians, taking decisive action to end the coup. The coup was swiftly countered, and the perpetrator of the military coup ended up apologizing, followed by the streets being cleaned again. And unfortunately, another dozen deaths were mourned.

Elections were held peacefully in November 2015, and in January 2016, Burkina Faso suffered its first large-scale terrorist attack on its soil, a harbinger of one of the most trying moments in Burkina Faso���s history. Today, terrorism has become deeply entrenched in certain regions of Burkina Faso, straining the country���s legendary inter-religious and inter-ethnic tolerance and generally sapping morale, all the more so because there is no clear understanding of what exactly is behind the wave of terrorist attacks. Faced with a much more diffuse and nebulous target than bringing down a president who overstayed, decisive collective action has been more difficult. But Burkinabe can at least remember that they have been capable of such action in the past.

October 28, 2019

Kenya’s mobile money revolution

Iringa, Tanzania. Image credit Brian Harries via Flickr CC.

One of the most talked about issues within the international development community and many governments in Africa today is that of fintech (financial technology). Defined as ���computer programs and other technology used to support or enable banking and financial services,��� Africa has become a hot-spot for the global fintech industry, with massive amounts of foreign investment flowing into the continent for a whole range of new fintech institutions and initiatives. Much of this excitement stems from the proliferating claims that, in a number of important ways, fintech will significantly improve the lives of poor people.

Africa���s new role in spearheading the rise of the global fintech industry can be attributed to one supposedly ���best practice��� example: M-Pesa, Kenya���s agent-assisted, mobile-phone-based, person-to-person payment and money transfer system. M-Pesa is both widely revered in the global business community for its demonstrated ability to make considerable profits, and in the international development community for its perceived ability to drive development and poverty reduction across the Global South.

The growing excitement surrounding M-Pesa has undoubtedly been stimulated by the work of the high-profile US-based economists Tavneet Suri and William Jack. Based on their long-running work, Suri and Jack suggest that the M-Pesa model of fintech has the potential to make a major contribution to resolving poverty and promoting sustainable local economic development in Kenya. They have specifically claimed in the prestigious journal Science that ���access to the Kenyan mobile money system M-Pesa increased per capita consumption levels and lifted 194,000 households, or 2% of Kenyan households, out of poverty.��� This dramatic assertion went viral, and fueled the perception of M-Pesa as a developmental miracle. M-Pesa is now widely seen as a model to be emulated, and has even been honored by the US-based Project Management Institute as one of the ten most influential projects to have emerged around the world in the last 50 years.

Although it is patently clear why the global investment community has such a great appreciation for M-Pesa���s profit-generating potential (more on this below), we argue that the accompanying poverty reduction and development claims attributed to M-Pesa are questionable.

There is no doubt that M-Pesa has played a role in stimulating petty microentrepreneurship in Kenya���especially microenterprises run by women���but much, if not most, of this activity has been woefully unproductive and largely unsustainable. In a business environment where one-person street stalls, retail units, fast food ventures, and shuttle traders have been operating in abundance for many years, it is not surprising that the microenterprise failure rate is very high, with half of new businesses failing in the first year. Promoting the establishment of even more such units is therefore seriously questionable. It is only likely to negatively impact the functioning of the local economy, as well as the livelihoods of micro-entrepreneurs.