Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 195

December 12, 2019

Ben Turok���s commitment to liberation, non-racialism and equality

Ben Turok. Screen grab from Ian Landsberg Youtube.

Since the news of his passing broke, tributes have poured in for Professor Ben Turok who died at his home in Cape Town in the early hours of the morning on December 9th, 2019. These have lauded his many public contributions: a dedicated anti-apartheid activist, he wrote the nationalization clause of the 1955 Freedom Charter, served time in solitary confinement and as an exile in the UK before returning to South Africa in 1990. Under a democratic dispensation, he served as an MP and chaired the Ethics Committee where he (in)famously investigated Minister Dina Pule and abstained from voting on the Secrecy Bill (as discussed in an interview on this site earlier this year).

In articles, radio and television interviews, and tweets, we have seen a common thread: an outspoken activist with strong convictions that was fiercely independent. Ben���s commitment to a set of principles even when these were unpopular is what set him apart from most. That was true of him as a white person under apartheid who chose to reject the benefits, which may come with that identity in a racist system; and it was also true of him as a member of the ANC who didn���t always agree with what his party was doing. These characteristics and contributions are critical and must be remembered. But for us who worked with him at the Institute for African Alternatives (IFAA), it is the projects that he chose to pursue in the last five years of his life that indicate where his passions lay and which we hope will not be lost in his commemoration.

Democratizing debate

Ben was a strong believer in the idea that everyone, everywhere should be able to access and engage with policy debates. He loathed jargon. ���Who are they trying to impress?��� he would ask, and then pressed us to simplify our prose and clarify our meaning. This was a firm principle for New Agenda, the journal that IFAA published and he edited. Ben was adamant that its purpose was to allow for ordinary South Africans to have access to important debates and that this prohibited technical language or unnecessary detail. While the staff often focused on increasing New Agenda sales in Johannesburg or Cape Town, one of Ben���s points of pride was that the journal found shelve space in the tiniest town in the most remote province. He would relish reading out the names of all the rural areas where even just one copy had been sold.

Student and youth politics

Ben was fiercely committed to the development of political consciousness in South Africans, especially young people. He was always ready to develop and deliver courses on South African political history, political economy and revolutionary social theory for university students, comrades in the ANC and the broader liberation movement. Tweets from young activists about the impact of his political education program would have made him happier than any of those from people in power.

He believed political education was key for any movement to achieve emancipation. He printed pamphlets on Fanon, on socialism, on Marxism, on old ANC policy documents and debates, and then demanded they be distributed widely, as years of IFAA interns can attest. He was insistent that face-to-face contact was the only way to build power and was reluctant to rely on social media or ���on-the-line��� activities as he called them. This belief gave him the energy to continue to go out and speak to young people even as he tired of reliving his history in the struggle. During our time at IFAA, Ben delivered lectures in numerous departments at several universities across the country. More recently he visited the University of Cape Town���s Department of Philosophy and Politics, the University of the Western Cape���s Department of Education, and Stellenbosch University���s new Social Justice chair under the direction of Thuli Madonsela (the country���s former Public Protector). He never refused an invitation if he could help it.

Of course, Ben took a serious interest in the student movement that began in 2015 and saw much promise in the new political energy of young people. In an editorial he wrote in New Agenda, he praised the students for showing ���great courage and tenacity��� in winning commitments for fee increase freezes, for an end to outsourcing and forcing through debates on curriculum reform. In addition, he praised those who stood up to ���massive intimidation by police and private security guards��� and for ���rightly calling out the Oxbridge mentality of our universities.���

It was in this context that we met Ben as graduate students sympathetic to the cause of ���decolonizing��� the universities. In the years prior to 2015, he had been conducting political education work at UCT���his alma mater and an institution that he believed he had a personal duty to reform. He gave these classes to keep a tradition of political and progressive thinking alive at a university that badly needed shaking out of its smug liberal complacency. However, he���and we���felt that more needed to be done to promote an intellectual and political culture, which perhaps needed to take place outside of campus. That is how the IFAA Forum began, taking place each Sunday morning in IFAA���s offices in the Cape Town CBD. It would be an opportunity for progressive students to share their work and ideas with peers. Despite being nearly three times the age of the next oldest person in the room, Ben���as was his way���was frequently the most vocal and challenging contributor to the conversation. The first topic was ���Kant and Ubuntu,��� something that Ben enjoyed but thought���in his words���a little ���indulgent.���

The topic in fact presaged an emerging conversation about the relationship between so-called ���Western��� and ���African��� knowledge. This conversation hit fever pitch not long after the student movement for ���decolonization��� became more and more pronounced. The mandate of the forum continued on, but the discussions became increasingly political and tense. The idea was to stage actual political debates and test ideas in real time, but this proved difficult to manage given the intensity with which arguments were being promoted and defended. The results were often productive but turned sour as an orthodoxy settled in determining and policing what constitutes authentic ���black��� or ���white��� or whatever forms of knowledge. It was easy, at the worst of times, for critics of this emergent discourse to be labeled ���counter-revolutionary,��� ���non-white��� and so on. It took significant courage and fortitude to persist in this environment.

Ben���s encouragement, along with other politically experienced comrades within the organization and in the broader left civil society space (including editors of this blog), was crucial for a group of progressive students who were supportive of the mission to decolonize but could not reconcile themselves to a politics of racial essentialism and nativism. Ben demanded that forums continue and that IFAA provide a platform for a wide range of views. He often joked that our reluctance was precious and na��ve. He would fondly retell a story of how, while approaching a platform at a mass rally in Zambia, the Guyanese leftist historian, Walter Rodney, once hid him from the view of black nationalist Stokely Carmichael in order to secure a ���whitey��� a place on the stage. Once the trick was done, Carmichael was furious, but neither Ben nor Rodney faltered in their principled commitment to non-racial comradeship.

Ben���s own politics on race and decolonization were on show at a recent speech he delivered to an audience at UWC on ���Africa Day.��� He wasn���t a na��ve color-blind ���rainbowist,��� a popular slur hurled at anyone defending non-racial politics these days. As he stated:

Let us recognize, and be bold about it, that the legacy of internal colonialism is still very strong and affects our society every day. The question in my mind, as one who believes in non-racialism, as one who believes in the Freedom Charter, as one who believes in the Constitution of South Africa, and that South Africa belongs to all of us, I hope that that formulation does not cover up the fact that the colonial legacy is still very strong. We can���t deny that. Even though we are for non-racialism, even though we are against racism, we can���t deny the continuation of colonial relationships in our society.

Yet this recognition did not lead to a politics of despair or one circumscribed by the walls of ���identity.��� He continued:

I told you that I am a white African. I have no identity crisis at all. I know what I am. I know what I have done. I know what I stand for. I apologize for nothing at all. I know my identity [applause], and I am not going to get into debates about my identity. I know who I am. I understand if some people want to raise questions about their role in society, but let us not say that that is more important than understanding the legacy of internal colonialism as a system ��� We have a hell of a lot to do.

Economy

Ben���s major obsession, however, was with the South African economy and the profound failures of the dominant macroeconomic orthodoxy of the post-apartheid era. He would often quote from the ANC���s 1969 Morogoro Conference:

We have already referred to the special character of the South African social and economic structure. In our country���more than in any other part of the oppressed world���it is inconceivable for liberation to have meaning without a return of the wealth of the land to the people as a whole. It is therefore a fundamental feature of our strategy that victory must embrace more than formal political democracy. To allow the existing economic forces to retain their interests intact is to feed the root of racial supremacy and does not represent even the shadow of liberation.

In the same address at UWC he noted various attempts of postcolonial governments to achieve self-reliance and return the wealth of the land and economy to the people as a whole. But also how that was historically undermined by the Bretton Woods institutions and in the present day by the apostles of fiscal discipline and macroeconomic consolidation. IFAA was founded, by Ben and other radical political economists, to challenge this orthodoxy and has continued to do so with great enthusiasm and energy under Ben���s lead.

Office conversations would almost always end up in the context and the results of the transition: The Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP) being drawn up and prepared, the work of the Macroeconomic Research Group MERG group with which one staff member participated, the hopes of a ���growth through redistribution��� strategy, all finally being washed away with the emergence of Growth Employment and Redistribution (GEAR). And later, the emergence of a Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) corporate elite, a development that Ben bemoaned and linked to Fanon���s concept of the ���national bourgeoisie��� who profited off limited race-based instruments of redistribution and would always be ready to deploy intense racial invective���like ���White Monopoly Capital��� and ���Radical Economic Transformation��� to secure expanded means of accumulation.

Ben made it an obsession to keep interrogating both the orthodox macroeconomic consensus and the emergent new black elite, which he saw as mutually self-constitutive, a point since elaborated on in an influential work by sociologist Karl von Hodt. Ben remained deeply concerned with understanding why some within the ANC had adopted orthodoxy, and he fiercely rejected simplistic accounts of a ���sell-out.”

In the last few years we were at least buoyed by growing global recognition that structural adjustment was a failure, that austerity has not worked, that privatization, corporatization, and the deregulation of financial markers has led to vast increases in global inequality. The ���End of History��� was actually only the ���Beginning of Insanity.���

All seem to agree, except South Africa���s mainstream economic commentariat who are joined only by the most outwardly reactionary global figures whose support for the rich has now lost all veils of pretense. Ben made it a priority to voice this in public as regularly as he could through various op-eds he wrote, radio interviews, and television broadcasts. The staff at IFAA were tasked with carrying out this work and challenging mainstream economic thinking in South Africa to move with the times while also acknowledging the deep dysfunction that has beset state institutions after years of plunder in the name of ���black empowerment.���

In his final year, Ben felt it necessary to communicate directly to the country���s highest office, such was his sense of the urgency of the situation. With a group of comrades, he penned several letters to President Cyril Ramaphosa demanding government abandon its orthodox positions. He arranged several seminars with progressive economists to map an alternative path for South Africa���s economic renewal, trying to inject confidence and coherence to a growing community that has been nonetheless marginal in actual policy decision making. He was frustrated with the release of Finance Minister Tito Mboweni���s latest budget speech, which seemed to reaffirm government���s commitment to fiscal ���discipline.���

But Ben would not give up. Another letter came and this time to ordinary MPs. If the presidency wouldn���t listen, perhaps those on the benches would carry on the fight as he did from their position years ago. He wrote: ���Wide ranging budget cuts will do much damage to the economy as it will reduce aggregate demand for goods and services which is what the economy sorely needs.��� The Treasury ���…has based their policies on austerity an approach that has been severely criticized internationally even by members of the IMF.��� His message to MPs was clear: reject austerity! We hope that his efforts to fight this will not be in vein.

Ben���s ethic of openness and debate

We did not always agree with Ben on all issues of politics or economics. Office debates were lively and robust, yet always enlightening. Ben���s life was immersed in the debates of the liberation movement and his outlook was fundamentally shaped by that. As leftists who grew up in a democratic South Africa and outside of party structures, Ben���s political formation was largely foreign to us.

But Ben���s commitment never circumscribed the scope of his conversation and the breadth and depth of his knowledge. He forced us to take seriously the intellectual traditions that shaped the broader South African and international left, while instilling in us an ethic of openness and debate. Ben had never wavered on this principle which had led him into much trouble historically within the South African Communist Party and structures of the ruling ANC, a history which seemed to fill him with pride. This was the ethos of New Agenda, which published from a variety of political orientations making up the broader liberation struggle and movement.

Ben was insistent that his staff read widely; our desks are littered with article clippings that he would diligently cut out and bring to the office, always with the added note that we should be reading more newspapers. He challenged us���sometimes quite forcefully���to say what we mean and to avoid equivocation. His pet peeve was when someone would begin to explain their research agenda with the phrase, ���I���m looking at ������ ���What does ���looking at��� mean?��� he would quip with irritation. His insistence that research had purpose, clarity and was grounded in the real problems of the world is undoubtedly something to which more modern academics should aspire.

The country will surely miss his astute commentary and fearless voice. Ben���s legacy will live on with those continuing to fight for the politicization and conscientization of the youth, the realization of substantive non-racialism and economic equality in our country. We are proud to have been comrades in that struggle during our time under his leadership at the Institute for African Alternatives.

December 11, 2019

Detritus of revolution

Karoo, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Image credit Fiver Locker via Flickr CC.

The South African writer Nthikeng Mohlele garnered wide attention last year for his novel Michael K (2018), a revisiting of J. M. Coetzee���s Life and Times of Michael K (1983), which received the Booker Prize and firmly established Coetzee���s reputation in the South African canon following his earlier achievement, Waiting for the Barbarians (1980). Mohlele���s novel is in part an homage of influence���Coetzee has supported Mohlele���s work through cover endorsements, and Mohlele has expressed his admiration for Coetzee in interviews. But Michael K is also a critique of the limitations of Coetzee���s characterization of the mute figure of K, a coloured man who is caught amid a civil war in a reimagined apartheid-era South Africa. Like The Meursault Investigation (2015), a reworking of Albert Camus���s The Stranger (1942) by the Algerian writer Kamel Daoud, Michael K gives voice to a fictional character in a way that mutually enlivens both novels through a literary dialogue that crosses identities, generations and time periods.

Mohlele���s project of reimagination further encourages a rereading of his earlier work. His second novel Small Things (2013)���he has published six so far���in particular can be read in retrospect as another response to Coetzee, albeit in a more indirect fashion. More specifically, it can be approached as a rejoinder to Disgrace (1999), Coetzee���s allegorical account of white male privilege and its delegitimation in post-apartheid South Africa. In the latter novel, as soon as the reader finishes the title page, one encounters the main protagonist David Lurie consorting with a prostitute���Coetzee���s work, it should be said, possesses moments of the bleakest humor���with Lurie���s status and life unraveling from there. After engaging in a non-consensual relationship with a student and losing his academic post, he moves to the eastern Cape to live with his adult daughter, Lucy, on her farm. This temporary retreat is disrupted by an act of violence���Lucy is raped by assailants who ultimately go unpunished���and Lurie, who once took advantage of the unspoken rules of academia, now finds himself the victim of an unwritten set of laws in rural South Africa. At the end of the book, with no home, no sense of justice, and no future, Lurie is left without the possibility of redemption, with what remaining sense of humanity he has expressed through his care of dogs that are destined to be euthanized. Coetzee���s novel presses the question of where the limits of sympathy lie, eliciting the reader to address whether such parameters are to be determined in a present political moment, or whether they reside within an ethics located more deeply in the human condition.

Mohlele���s novel offers a number of surface contrasts, but in different ways approaches a similar set of questions to that of Coetzee. In Small Things the unnamed black narrator���and, thus, an everyman in Mohlele���s usage���is the same generation as Lurie, born at the time of apartheid���s birth and that era henceforth shaping his life and outlook as a result. He attends a mission school, resides in and witnesses the demolition of Sophiatown, and becomes a political journalist, which leads to a period of imprisonment. At a certain level, these are familiar points of orientation. However, Mohlele���s narrative becomes more interesting when it reaches the recent past. His protagonist, now older and hardened by his time in activism and incarceration, finds himself adrift in Johannesburg���an existential condition in the wake of political transformation that approximates Lurie���s, although not one due to his own immoral behavior but, rather, the growing immorality of post-apartheid South African society. Flush with cash and with wealth inequality motivating spectacles of fortune and criminal behavior alike, the Johannesburg of Mohlele���s imagination has no time for social reflection or the past. As he writes, there are ���two Johannesburgs���one for vagabonds and the other for senior executives…In this other Johannesburg, the one of plush, air-conditioned cars, the revolution is without the slightest meaning.���

These circumstances leave Mohlele���s protagonist a lost figure. Indeed, the long middle section that depicts this predicament is entitled ���Nausea,��� a seeming reference to Jean-Paul Sartre���s existential novel of the same name. Unlike David Lurie, whose status and privilege were unearned and whose fate goes unmourned, if not vocally celebrated either, Mohlele makes a different argument about post-apartheid futures and more particularly, how those who participated directly in the struggle have not been beneficiaries of a new dispensation. ���Is eighteen years that long, that existence seems to be turned on its head?��� Mohlele���s main character ruminates. ���Or is it aftershocks of prison life that have slowed me, all those weeks in solitary confinement when it mattered not whether time moved or didn���t? Everyone in this city seems programmed to be in a hurry, to hop on the speed train to nowhere.���

As in Disgrace, the story in Small Things has an act of violence placed midway, serving neither as a climax nor a conclusion, but nonetheless rupturing the narrative in a way that reshapes what came before and what comes after. It is an act of violence both universal and specific to the ���new��� South Africa. Mohlele���s unnamed narrator recuperates by way of a relationship with a younger woman, Mercedes, by learning to play the trumpet, and, at one point, by caring for a dog, Benito, in a way that Lurie would appreciate. But these circumstances, too, gradually evaporate, with Mercedes leaving, Benito returned to his original owner, and Mohlele���s protagonist finding himself homeless during a Johannesburg winter. He recovers slightly, finding work as a waiter in a restaurant and living with the boyfriend of an ex-lover, Desiree, though both situations accent what he has lost and will never have again.

Small Things and Disgrace both touch upon universal themes of aging and loss, the promise of change and the impossibilities of redemption. The fates unfolded in both novels are unique, but they share common ground regarding ordinary lives under post-revolutionary conditions. They point to how such lives can become human detritus in the face of an ever-moving futurism, a destiny even among those who committed their lives to such change. Mohlele glosses a Fanonian view on such matters���how, paradoxically, only elites benefit from political revolution���but a more meaningful message comes through in a letter to Mohlele���s protagonist from Mercedes, who returned to Cuba from where her family originated. ���You should have come here,��� she writes, ���You would have loved Cuba and its contradictions���our outdated American cars, desperate people dying, drowning en route to becoming Cuban Americans. Fleeing from a revolution that yielded small things: aging sugar-cane plantations and rum distilleries. Socialism. Phew!���

The title expression appears in this instance, and it recurs at several points in the novel, including near the start and in the conclusion. Mohlele���s fixation on these words invokes a provisional source of personal rehabilitation, if not quite redemption, through which the concrete details of ordinary life can provide a source of explanation and meaning when larger dreams and transformations prove to be illusory. Desiree, whom Mohlele���s central character falls in love with during his youth, ends up in a coma toward the end of the novel, a symbol of how the passions and ambitions of the past can eventually become unreachable���both impossible to communicate with and powerless to restore once more to complete health. In this, Small Things imparts a complex vision of ideas and feelings about post-apartheid South Africa as captured by Mohlele, one that is irreducible to words like revolution, or disgrace.

December 10, 2019

Lagos in its filthy glory

Still from The Ghost and the House of Truth.

Nigeria���s commercial capital, Lagos, is an enigma that defies logic, an attractive villain that seduces its victims with faux commercial hopes and gaslights them into an abusive relationship. Nollywood often plays into its hands, portraying it as a glorious city, one full of merriment and rich people who fight over the most mundane things at big parties. Akin Omotoso���s feature film, The Ghost and the House of Truth, sees right through the bullshit; it acknowledges that Lagos is a mad, violent man.

The film is an authentic but unpalatable dramatic and visual feast that captures the filth and brutality of Lagos, without apologies. However, despite its many stunning aerial shots capturing the filth of Makoko, there is nothing exploitative about this film. It is not poverty porn. Omotoso is from Nigeria, after all, so he knows better. He, instead, has created a cinematic experience about the cruelty of Lagos. He shows the audience the Lagos that pushes the sane to insanity, the meek to thuggery, and the lawful to anarchy.

To unmask Lagos’ fa��ade and show its true colors, Omotoso���working with the terrific duo of Christian Epps (gaffer) and Kabelo Thathe (cinematographer)���shoots in low light and uses less cinematic cosmetics, so the picture is very raw and realistic. The actors��� faces look dark and sweaty, and the environment: dirty and ugly. The ugliness is not for fun; the story is distasteful and distressing, and Omotoso wants to create the appropriate world for it.

The story���s protagonist, Bola, is a dedicated counselor who helps convicts reconcile with their victims. In an early scene, we see her facilitate a reconciliation session between a convict, Debo (Seun Ajayi), and his victim, Mrs. Douglas (Gloria Young). Bola is calm and collected during the session. But one day her daughter, Nike, does not return home from school.

As the hours tick by, Bola moves from calm to unsettled to paranoid. She visits Joe, who drives Nike and her cousin to school, and scourers the city looking for her child. Finally, she goes to the police.

���My daughter is missing,��� she tells the policewoman at the counter. ���Please, write statement,��� the officer replies. But Bola is impatient, she wants answers immediately, and she knows writing a statement will not help her situation. Then enters the pregnant inspector Folashade Adetola aka Stainless (a steely, intense Kate Henshaw), who recognizes Bola from court meetings. She takes Bola upstairs, after brief questioning she promises to handle the case following due process. Bola knows “due process” takes forever in Lagos, so she offers money to help speed up things. ���Dem dey call me Stainless,��� inspector Adetola says, refusing the bribe.

True to her word, Stainless takes up the case, and she gives Bola regular updates. The first suspect is the aforementioned Joe. Bola says the kids love and trust him, but when she hears he was imprisoned in Kano for ���touching��� small boys, he becomes guilty in her eyes. Another name comes up, Mr. Ayodeji (who is also a sex offender), he seems guilty but says he is innocent. Stainless believes so, too. Bola does not. She starts to stalk him. One day after shadowing Ayodeji, she returns home to the news that her daughter has been found dead. Nike was raped and murdered.

After Nike’s death, the investigation accelerates. Stainless calls Ayodeji for more questioning, when things get intense, he calls for his lawyer, and suddenly he has an alibi. Heartbroken and feeling helpless because the law cannot help find her daughter���s murderer, Bola becomes vengeful. It would be a disservice to discuss the events that follow, but it all points to one thing: Lagos is cruel.

British-Nigerian actress Susan Wokoma, who plays Bola, brings incredible humanity to her character. As the taciturn inspector Stainless, Kate Henshaw is terrific, her contained intensity praiseworthy. Her performance echoes an unpopular sentiment I share: Nollywood actors are not often well-directed, and the stories are not layered enough to evoke strong performances. In the heartbreaking scene where Stainless informs Bola of Nike���s death, Henshaw and Wokoma emote quietly, but powerfully. It shows how in control they are of their performances.

There is an excellent cameo towards the end by a character who appears in a fantastic chase sequence that captures artfully the brutality of Lagos, the limits of the law and the painful reality of poverty. I have always believed the slums of Lagos are cinematic settings unlike anywhere else; this chase sequence proves so.

The film is a reminder that we need more representation of this Lagos in our cinemas. Succeeding this scene is the film���s emotional climax, a sucker punch powered by haunting music and one last dose of quiet, powerfully emotive performances from the cast. I left the cinema delighted but also desolate: the film reveals our reality as Lagosians.

At the edge of sight

Cover image of Ambivalent: Photography and Visibility in African History. Used with permission of the publisher.

For years, a number of colleagues and I have been exploring our shared interest in visual material produced about and within the African continent. We read a lot while pouring over our respective historical image collections. Reading became a crucial part of the process of looking, mediating one���s own contemplation in order to find the language to weave narratives about the images at our disposal. Such images had granted themselves to our scrutiny, allowing us to develop a profound intimacy with them. And, while existing literature occasionally provided crucial frameworks to make sense of practices by which Africa has been looked at, mapped, surveyed, measured, and displayed, at times the images appeared unruly when placed squarely within this vast scholarship. Some even seemed weary of analytical closure, insisting we become comfortable with holding conflicting viewpoints, hinting to us that photography in Africa ���is doing much more labor than imagined and this labor is more ���strange��� than anyone expected.���

Ambivalent: Photography and Visibility in African History is a result of our collective effort. It is an edited volume whose contributors inhabit that space of ambivalence through their long-standing engagements with visual material, particularly photographs, but extend these conversations to other historical material that pertain to visibility, on the continent. The editors write that photographs perhaps, ���draws us to the edge of sight.��� They make us aware of a world that lies beyond that which we see without fully disclosing it. For a number of scholars on the continent, including me, this has been an important meditation to hold on to in that dual process of looking and reading. Indeed, in this volume, essays by Isabelle de Rezende, Patricia Hayes, Vilho Shigwedha, Drew Thomson, and Napandulwe Shiweda, in different ways, go beyond the confines of what is visible by reflecting critically on photography���s attachment to language and the very repositories in which such collections often reside. The authors consider the dialectics of visual interpretation and the manner in which imagery can inhabit non-visual texts. They remind us that while photographs carry an immense capacity for display, they can eclipse important histories that often emerge through oral engagements as well. They also suggest that photographs can exceed the parameters of discursive frameworks that scholars and institutions impose on them, including narratives of (de)colonization.

In conversations with individuals at Omhedi who recall native commissioner Carl Hung���s and Alfred Duggan-Cronin���s photographic expeditions to the region in the 1930s to record the “eroding traditional way of life,” Shiweda is surprised at the oft-positive responses to such images that at once fix and contain. In their re-circulation, they allow for re-fashioning and can transform as signifiers. If ambivalence implies a degree of immoderation, several authors in the volume are concerned with precisely that. Essays by Ingrid Masondo and Gary Minkley draw attention to bureaucratic photographs that lend themselves easily to critic Allen Sekula���s widely cited dictum on repressive photographs. Both authors, however, suggest that such photographs are unstable in their very composition and in their capacity to circulate for re-purposing, thus calling us to question the dichotomy of the repressive and honorific.

One of the most striking images in the book is a digitally retouched photograph by Nigerian photographer Mbadimma Chinemelum who inserts a young woman into what appears to be a sea of textile. In his essay, Okechukwu Nwafor writes about the practices of digital reworking and re-contextualization in Nigeria and questions the assumption that ���photography is a spatial-temporal phenomenon that must follow a narrative consequence.��� In my own work on East London based photographers Joseph Denfield and Daniel Morolong in South Africa, I found it productive to think about both photographers��� work oceanically in order to allow two sets of collections that are separated by time to speak to each. Looking at Denfield���s Victorian-era photographs through Morolong���s apartheid-era photographs at the beach allowed me to unstitch the former from settler historiography.

���We have to constantly worry about what photographs do and don���t do, not just what they are seemingly or ostensibly of,��� writes Minkley in his concluding remarks. This is precisely George Agbo���s concern in his essay on the production and circulation of Boko Haram imagery on the internet. Such images precipitate violence and simultaneously, are put to work to undo that very violence. Nwafor, Ago and I foreground technology as the means by which such resurfacing and transfiguration takes place. Jung Ran Forte���s essay, which concludes the book, is thus, a welcome challenge to those of us whose accounts hinge on such technologies. She reminds us of other forms of transfiguration through spirit possession on the continent that predate photography, and the reliance on non-photographic imagery to mediate those processes. What camera operators do digitally in Nigerian cities in the 21st century to shape-shift, manipulate, excite, and celebrate, it appears that the water spirit Mami Wati has been indulging in for much longer.

Does location matter? I think a great deal. Most of the contributors are based on the African continent. This is where we live, work and play. And all the contributors���whether as research fellows or professors���have drawn on interlocutors across institutions on the continent. I can���t say with certainty that writing about African photography from “within” chips away at perspectival distance with its promises of illumination and clarity, but I suspect something of the sort. Perhaps a different kind of viewing takes place, one that is translucent but attentive to the mist at the corner of one���s eye. Daniel Morolong���s subjects in East London in the 1960s on the cover of this volume are framed tightly on the train and transport us to visibility���s edge. Yet, the train���s mobility has been suspended, however briefly, and deferred as well are the rhythms of black labor, so intimately tied to the train, with its predestined routes. In front of us, instead, is a captivating energy. Perhaps if we allowed ourselves to respond in kind, photography in Africa could take us to unexpected destinations in the most regenerative fashion.

December 9, 2019

Pan-Africanism and the African artist

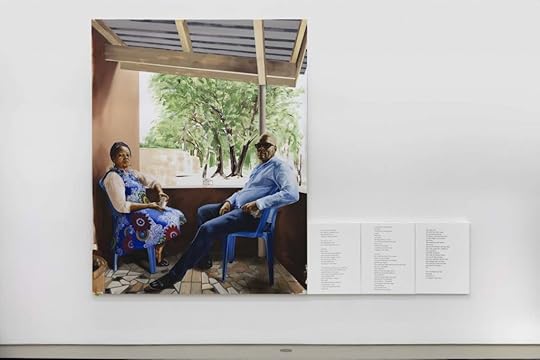

Meleko Mokgosi. Image courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery.

The Botswana artist Meleko Mokgosi opened two exhibitions in early November of this year, at Jack Shainman���s New York City galleries, The social revolution of our time cannot take its poetry from the past put only from the poetry of the future and Pan-African Pulp. Democratic Intuition another multi-year and multimedia exhibition is on view until Spring 2020 at Jack Shainmen���s The School located in Kinderhook, New York. These shows are impressive for their scale and scope, and come on the heels of exhibitions in Johannesburg, South Africa at the Stevenson Gallery and at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor.

The opening of Mokgosi���s New York City shows presented an opportunity for me to speak to the artist, who I know from our shared time as art majors at Williams College, about his educational and professional trajectory. Born in Francistown, Botswana, Mokgosi currently teaches painting at the Yale University���s famed School of Art, where luminaries like Kehinde Wiley, Barkley Hendricks, Howardena Pindell, and Wengechi Mutu amongst many other black artists have trained. Ironically, Yale and other top MFA programs had rejected Mokgosi, who after the Whitney Independent Study Program trained with the artist Mary Kelly at the University of California-Los Angeles. Mokgosi���s multimedia works take years to produce and unfold for the public in various iterations and chapters, thereby offering complex views of history and powerful critiques of pan-Africanism and the postcolonial moment we are currently living.

Drew Thompson

How do you think of yourself in relation to the history of art in Botswana? Do you have any artistic influences?

Meleko Mokgosi

The way I got into the fine arts was having drawn for a long time, copying comics, copying stuff from the newspapers [and] magazines, and just kind of randomly. It was just through a high school teacher, who was a British artist and had been in Botswana for like 25 years. I was introduced to art basically through like Weimar Republic, German Expressionism. There wasn���t any African art [in Botswana]. There was no South African art, which would have made sense. We [Botswana] share a border with South Africa[, and] we share a close history with it. I did not know any of those people, whether like William Kentridge. So, it was kind of a precarious and weird thing. But I guess it is just the baggage that we have as we developed.

The Social Revolution HR 2 �� Meleko Mokgosi, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

The Social Revolution HR 2 �� Meleko Mokgosi, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.Drew Thompson

That came with the colonial institution or the legacy of education in Botswana?

Meleko Mokgosi

[T]he education system [in Botswana] for a long time has been based on the Cambridge education system. I read Jane Austen through and through. That kind of work took me to English literature. Actually, at Williams College I focused more on English literature than like painting. So even without the fine arts, the cultural production was British oriented. I was just speaking to someone in Chicago who was organizing a really amazing exhibition around Medu [Art Ensemble], a poster collective. I met a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, Felicia Mings, and one of the questions she asked, ���Did you know of this thing [MEDU Art Ensemble]?��� I was like ���No.��� Even if I was to go back home, no one knows what MEDU is. No one knows the connection them starting in South Africa, moving to Botswana, and still producing these really important cultural artifacts. I guess it is the same thing with the Pan-African Pulp stuff. Not many people know them. Like, no one knows a lot about it in Southern Africa.

Drew Thompson

You talk of yourself as this artist of the West who could be from Botswana? Could you talk about your educational trajectory as an artist?

Meleko Mokgosi

My approach, which again comes from this very peculiar entry through German Expressionism, was the idea of the artist as someone, who first and foremost invested in a kind of socio-political engagement with the contemporary. People, like Max Beckmann and Kathy Kollwitz, were engaged with the questions of the day, which had to do with fascism and the working class, a kind of specific inequities and inequalities and also with pedagogy. They were interested in a public dialogue in a critical setting. That���s what being a painter meant. Going to Williams College really was an important step for me. I came in with very specific tools of painting. Then I was taking classes with Ed Epping, Laylah Ali, and Mike Glier, really building the conceptual tools. It really was not so much fine tuning the painting. It was kind of building that conceptual framework under which I wanted to make these statements.

Drew Thompson

But we might want to add that Ed Epping, Laylah Ali, and Mike Glier, were all drawers at their core?

Meleko Mokgosi

Totally. I had to paint in that way [of drawing]. I drew in charcoal for seven or eight years. Until 2003, again this high school teacher after a while, he was my mentor, he brought me some paint. You look at how I paint, then it looks like I use paint as if I am drawing with charcoal. Charcoal is very reductive. You put down pigment and you remove it to the volume, and so forth. That is literally how I paint. I don���t paint in terms of additive formulations. It is more subtractive basically. It was really amazing to go there [Williams]. The art history made me aware of it, the history. But, then again, I was really narrow. I left Williams without knowing any African artists, any African art history. It was mainly Europe and America, you know. But, it actually prepared me to go to the Whitney Independent Study Program. Because I think without that strong foundation of history and [a] conceptual [framework], I don���t think I would have been able to fit in, be accepted into the Whitney Program. It was there, always political, always trying to figure out what I was trying to do. And at the Whitney was also a big game changer. I was forced to think about the natural language of painting. This was also where I met Mary Kelly, and this was where I was like it was not about painting.

Drew Thompson

It is an interesting point you make about your trajectory and schooling in art. It seems to me your practice is about unschooling, reschooling on certain concepts that have been formative to your life as well as to the cannon. Who do you envision as the audience of your work?

Meleko Mokgosi

I guess it depends. The paintings, like if someone is from Maun, which is where I am from, [my paintings] would make sense at a certain level. They can identify with the kind of texture and the kind of atmosphere. But, they wouldn���t need postcolonial theory to unpack it. There is a certain identification that comes with it. Whereas in academic contexts, someone might not be able to identify with this history or context but they might be able to identify with the discursive framework, which [relates to] a certain kind of critique of art history, a critique of representation, postcolonial theory, critical theory, and so forth. So, as far as the audience is concerned, the most important thing for me is for the viewer to acknowledge and reconcile an intense amount of investment [that they] have in the things that are being represented.

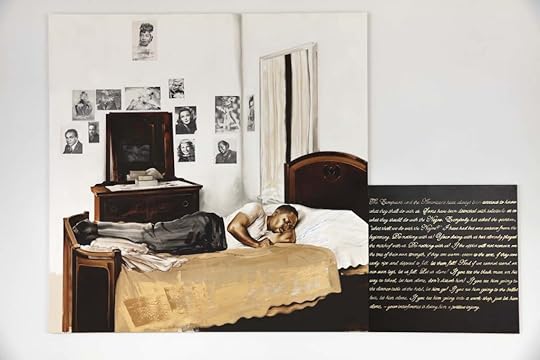

Pan-African Pulp �� Meleko Mokgosi, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Pan-African Pulp �� Meleko Mokgosi, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.Drew Thompson

A lot of work is going into institutions which until 2003 you had never visited before. What is it that having institutions collect this work and it being in institutions that you hope that work will allow institutions to do?

Meleko Mokgosi

I think again, at the basic level, is for the viewer to see that there is an intense amount of investment in these things that do not occupy the center, that are not a part of the West [and] not part of the grand narrative. The center does not matter that much. I think that is a very important part as someone who is kind of Westernized, that tries to antagonize the idea of being from the Diaspora. You know I think of myself as very much from Botswana and not of the Diaspora. Having worked so much to convince people that I am like them, that I am Western, that I know English, that I went to the right school, that I am part of the institution of art. There is a certain way in which when you are not from the West, you try to make yourself legible to the West in some way. I have done that in a personal way but not through the art work. That is where I draw the line. The artwork tries to make the argument that is it possible for the Western viewer, or any kind of viewer, to look at these things and find a way to abstract themselves outside of their one subject position and find a way to empathize with another subject position that does not occupy the grand narrative, again engage with this material with the recognition that they are going to fail at some point.

Drew Thompson

How much do you take into consideration the history of the people that you are trying to portray in relation to the question of scale?

Meleko Mokgosi

It is all about [scale]; it is a way of monumentalizing and bringing into center things that have not been allowed to occupy certain space. [H]istory painting [is] a way to communicate very specific kinds of historical events of very monumental people. So, I am using that scale. But then inserted in the idea of cinema, which is why the work tries to mimic the film strip, as a way of building an installation that allows the viewer to enter it and become a part of it and to engage with it. And also, the idea of genre painting, the idea of a Dutch trope, the mundane quotidian space, where someone made doing something. In a kind of art historical context, the genre painting was kind of the ordinary thing. So, I am mixing these tropes to kind of produce representation. Also, I think scale has to have a 1:1 relations. In cinema, it is important to think about the kinds of shots you are using. So, I don���t use any long shots or close-ups because those have very specific kinds of functions. I use a medium shot, which allows a certain amount of context. The long shot is about the contextual thing. I am not interested in that. I am not interested in saying these are the facts; these are the things I am talking about. I am always skeptical of the idea of history.

Drew Thompson

What has the use of photography taught you about your painterly technique? How have you used photography to rethink painting as a mode of representation?

Meleko Mokgosi

I do work mostly from photography, pretty much exclusively. Half from pictures I take and half from appropriated images. I would say it [photography] is more limiting than I found, not just for myself. But, if you look at painting in general, in the last 150 years, it is very much tied to the pictorial framework about the picture, about how photographycaptures space. It is something that I am trying to overcome now. I am trying to figure out how to expect space, how to think about space differently, how to think about things like the pose, setting, lighting���these things tied to the photographic context. But, I have pretty much painted with that kind of mechanism. But, it is also a way to relate to the history of representation, which, if we think of the black African subject, that subject enters the visual language of West through an ethnographic and anthropological framework. Again, that is an important part I tried to think of: what kinds of images have been reproduced and what politics do these images reproduce?

Drew Thompson

You give space in your paintings to your photographs. In this exhibit, I see Winnie Mandela and Hollywood stars.

Meleko Mokgosi

How photography functions in the Southern African context in general is very much tied to liberation struggle. Especially, if you look at South African photography. A lot of the precursor to a lot of South African contemporary artists, mostly photographers.

Drew Thompson

You could say that as well of Mozambique?

Meleko Mokgosi

People weren���t sitting around painting. People weren���t doing installations. Photography was a medium of communicating struggle and trying to get the word out there, that is what was happening or these were the politics, domestic servants and mine workers. That only exists in a documentarian historical context, unless someone like Ernest Cole is known in the art context. Then again, he is more well known as someone who has documented the apartheid regime more than a fine arts photographer. It is important to fold in these other forms of representation, that have to do with someone like Albertina Sisulu or Winnie Mandela, who are important figures in the struggle [and] to do so in painting in the form of photographic representation.

The Social Revolution HR 1 �� Meleko Mokgosi, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

The Social Revolution HR 1 �� Meleko Mokgosi, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.Drew Thompson

It also shows how photographs inhabited people���s lives. They [the photographs you reproduce] were the images they saw every day?

Meleko Mokgosi

Absolutely, these are all things we lived with. That���s why I use a lot of posters. They are objects and images that we lived with. They fed our imagination and tried to get us to conceptualize things differently.

Drew Thompson

Pan-Africanism and nationalism embodies your work. Sometimes, I saw your scenes and thought they could be of anywhere in Africa. But, as we know, the pan-African vision was not kind to everyone in Southern African. Botswana inhabited a very different geography when it came to pan-Africanism and apartheid.

Meleko Mokgosi

Well, Botswana was not touched by those things. Again, it depends. Most of the images I deal with mostly happen in Botswana or South Africa. Because, I think there is a certain kind of physiognomic difference when you look at people from like Mozambique, who are of Portuguese heritage. People have different kinds of heritage. That���s part of my politics. I don���t think I can speak from subject positions that I don���t know anything about. Maybe that why it is hard for me to paint things about African-Americans. I don���t think it���s my place. I don���t want to enter those politics, a part from that painting based on the Aaron Siskind photograph. The pan-African part has molded with the new project, the new kind of desire to try and overcome the limitations that have been put in terms of the idealization of pan-Africanism as a political strategy and also as a patriarchal structure from 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and so forth. To kind of figure out, it���s more personal, as well as political, continuously trying to reconcile my position in the American context as someone who does not identify as black. But, I identify as African. The American historical context is very invested in interpolating my subject position as a black subject and having to deal with that modification that I am black.

Drew Thompson

Then, there is the diaspora framework?

Meleko Mokgosi

Totally. I had to come to this country [the United States] to experience my blackness in a certain way, which I am trying to reconcile with. And, I am trying to do it through this thing of pan-Africanism, as very naively my understanding, trying to use it as a political strategy that is sustainable as a way of fighting white supremacy.

Drew Thompson

How much does titling the work as well as the way you use color factor into that approach of pan-Africanism and wanting to rethink [your] positionality?

Meleko Mokgosi

I had to unlearn academic painting to formulate another way of painting the black subject as a way of engaging with the history of representation [and] of not using white or academic formulas, again white, magenta, green, and blue. But, you know I basically had to come up with a concoction of painting flesh tones in a way that capture the likeness of the black skin. And, I think that is a part of the politics. The instruments that you use to communicate should also be part of the content. I think in art historical frameworks people tend to think of the content and technique separately and actually it is not. The tool is very much a political gesture. The same with the titling. I usually never start a project without the title.

With pan-Africanism, I am trying to figure out how blackness manifests in specific contexts. If you look at Kerry James Marshall, the way he is thinking about blackness is very specific. He uses color in a very particular and political way. He also uses acrylic paint not oil. He uses highlights. I would make the same argument of how I use paint to try to engage with a certain kind of blackness, which is, in the Kerry James Marshall case, blackness circumscribed in the discourse of whiteness and the limitations that [representation] has put on access to the black historical subject in that cannon. Whereas, I would say that the way I am thinking about blackness has nothing to do with race discourse; it is much wider, I would say. It is related to the colonial discourse, which is about a certain kind of whiteness. It is not whiteness that has to be in blackness.

I think the idea of blackness in the West, and in the art historical narrative, is really narrow. I think it is so narrow that it is actually kind of violent, because there is only one kind of blackness that is legible and that is African-American blackness. There is no other kind of blackness, African blackness, South African blackness, Brazilian blackness, Australian blackness, blackness in Eastern Europe. I am thankful the African American blackness is at least visible and that there is a certain kind of gesture towards it. There is a certain kind of hope for the kinds of blackness that we want to deal with, that they might be legible at some point.

December 8, 2019

#Metoo in Nigeria

Lagos Street scene. Image Credit oneVillage Initiative via Flickr CC.

In July 2019, about a week after a Nigerian photographer Busola Dakolo went public with claims that she had been raped by Biodun Fatoyinbo, the charismatic mega-pastor of the Commonwealth of Zion Church, another woman came forward with evidence against him. The second woman���s story shared similarities with Dakolo���s, but it was also remarkably different. Dakolo had been a teenager just out of secondary school when she says Fatoyinbo raped her twice. The second woman, who chose to tell her story anonymously in a video chat that blurred her features, had been an adult member of Fatoyinbos staff when she was allegedly assaulted.

Her account was detailed, episodic even. The event, she alleged, took place in 2017 just about a year after she accepted a job offer to act as legal guardian to the Fatoyinbos children in an unnamed foreign country.

She says that prior to the assault, she���d been aware of previous harassment claims against Fatoyinbo, but did not believe them. He was, until the moment of the alleged rape, a mentor and father figure. In the days after the assault, she���d carried on with her life, showing up at work, determined to will the violence away while she planned her exit. What was most striking about her story was her resolve not to press charges even though Dakolo had already come forward.

And yet her reaction is not unusual at all in a place where people who experience sexual violence are afraid to press charges or speak publicly for fear of losing their livelihood or safety. In a country like Nigeria, survivors of workplace sexual harassment know that facts are not enough.

A #TimesUp moment dead on arrival

Still, the attention the Fatoyinbo case garnered in the weeks after both women shared their stories raised expectations that this time the accusations would be weighty enough to tip the scales in favor of justice. Some thought that this was going to be the beginning of Nigeria���s reckoning with our pervasive culture of violence against women and vulnerable people���s bodies. And perhaps, this would snowball into a cultural shift with the necessary policy changes.

Days ago, however, that hope was put to rest after Dakolo���s suit against Fatoyinbo, who has continued to maintain his innocence, was thrown out of court for being, “purely sentimental and an abuse of the judicial process.” More than the legal merits of Dakolo���s case, this ruling speaks to the power Fatoyinbo wields as the founder of one of Nigeria���s wealthiest churches.

Online, Nigerians disavowed the mega-pastor���s victory, but this time the pushback lacked the zeal that had inspired protest marches in the country���s major cities after Dakolo���s story broke. The usual skepticism towards the country���s legal system and its inability to hold sexual perpetrators accountable returned. With the ruling, Nigerians had again confirmed that the country was not yet ready for the equivalent of #MeToo.

Worse, according to Nigeria���s Labor Act Fatoyinbo���s former staff was not even in the position to file a sexual harassment suit against her former employer. If she had chosen to hold him accountable on those grounds she would not have had a case in the first place, because Nigeria���s labor law does not criminalize sexual harassment in the workplace. The only options available to her as an employee raped by her boss, by law, would have been to continue her job in silence, make a complaint to the church, and hope for the best or resign.

Fixing a broken system

An attempt in 2008 to update the country���s workplace laws, with a new Labour Standards Bill that made provisions for sexual harassment, fell through in the House of Representatives. Eleven years later, Nigeria has yet to update its labor laws.

When we collectively talk about sexual harassment in workplaces across the country, it is often discussed as an industry-specific problem. One that affects women in, say, banking or the service industry, not necessarily progressive startup-type workplaces with a young, upwardly mobile, and liberal workforce. And while it is a more pervasive problem in certain industries, more people are enduring sexual harassment across a wide spectrum of work spaces and in universities where male academic staff have long been suspected of coercing sex from students in exchange for better grades. Not acknowledging this means that people are less willing to take collective action and more likely to ignore isolated claims. By contrast, South Africa has a Code of Good Practice for the Handling of Sexual Harassment Cases spelt out in its labor laws, and in East Africa many organizations are working to change cultural norms that enable violence against women and vulnerable people with programs like SASA!

Mobilizing communities to prevent violence against women and vulnerable people, including changing policy, matter because they tilt the scale against rulings like Dakolo���s that make survivors less willing to speak up. While it seems that Nigeria is falling far behind, organizations like Project Alert are working to change the culture from the ground up with outreach programs in schools, churches, mosques, and online. In addition, Nigeria now has a publicly accessible list of registered sex offenders. It���s not a lot, but it is progress.

Is there a line, and who makes the rules?

In spaces where the conversation is already taking place, people are often willing to admit that they are uncertain about what crosses the line, especially when the predator has not been caught pants down or accused publicly by multiple victims. But, there are easy signs to watch out for, and everyone can do something. If a colleague says that they have been raped or subjected to an act of sexual assault, an appropriate response would be to say: ���I���m sorry this happened to you��� and ask the victim what they would like you to do or what they need in that moment. You can also refer the victim to a place like the Mirabel Center where they can get help. Keep in mind that showing anger may not help much, and no matter how strongly you feel about what has occurred, it is not your place to try to fix it or take action without their consent.

If you are not sure a colleague is being harassed or someone you know is crossing the line, specifics like unwelcome sexual advances or innuendos, sexually suggestive jokes or comments, unwelcome or inappropriate touching, and unwanted sharing of sexual content are signs to look out for. And if you are certain that you have just witnessed a workplace sexual harassment incident, it���s important to intervene if that is a possible option. Do your best to stop it from continuing. You can offer support to the affected person as well. When possible, document what happened in order to support a possible investigation.

Employers can do more as well. A sexual harassment policy that clearly defines harassment goes a long way as does having a zero tolerance approach. In the end, we need to be deliberate about creating work spaces that make it impossible for predators to thrive, and to take serious action when cases are reported.

This article is published as part of the 16 days of activism online campaign to end violence in the workplace. This is led by the��GBV Prevention Network, coordinated by the Uganda-based organization��Raising Voices. Tweet @GBVNet or visit the��GBV Facebook or Instagram pages to join the conversation.

December 3, 2019

Women’s political consciousness in Senegal

Road photography between Dakar and Mbour. Image credit Carsten ten Brink via Flickr CC.

I have known Ruth Bush for many years and we share a passion for reading Francophone literature, especially by African writers. The year I lived in Bristol, where she teaches, Ruth introduced me to AWA: La revue de la femme noire, one of the earliest independent African women���s magazines published between 1964 and 1973. At the time, Ruth was digitizing the magazine into an online archive as part of a fascinating project she started with Dr. Claire Ducournau. We started a conversation on the topic and she later invited me to the exhibition of the project at the Mus��e de la Femme Henriette Bathily in Dakar, which was co-produced with IFAN-Cheikh Anta Diop and launched as part of that year���s Ateliers de la Pens��e.

Earlier this year, I had a project that required me to write an article I provocatively titled: “‘The left and its leftovers’: Documenting women���s political activism in Senegal between 1950 and 1979��� as part of the Revolutionary Left in Africa Conference. I discussed with Ruth and she shared valuable material with me. I decided to focus not only on AWA���s voice through its editorial choices, but also critically analyze AWA���s silences in what was to become a central period for the revolutionary left in Senegal; from liberation movements and social movements culminating in May 1968, the musings of political pluralism, and last but not least, the rise and rise of a female political consciousness.

Rama Salla Dieng

Your passion has led you to dedicate a book to analyzing institutions, authors and ideas involved in the complex architecture behind your book, Publishing Africa in French. Can you please tell us more about this research, its motivations and findings?

Ruth Bush

My research began from a love of work by writers such as Aim�� C��saire, James Baldwin, Cheikh Hamidou Kane and Richard Wright, who lived in Paris in the mid-20th century. I was living in Paris and learned a lot about the city and its paradoxes through these writers: its claims to represent freedom and the avant-garde alongside its deeply rooted social and racial inequalities. It was illuminating to connect these writers��� literary work to larger political debates concerning decolonization and tiers-mondisme that came to the surface via journals and publishing houses such as Pr��sence Africaine and Editions Maspero. I spent a lot of time during my PhD working in the archives of publishing houses (many held at the Institut m��moires de l�����dition contemporaine. I looked at readers��� reports on manuscripts submitted by African writers, including Cheikh Hamidou Kane and Malick Fall, in this period. These reveal how these manuscripts were evaluated and according to what notions of aesthetic value they were measured. This led to the central concern of my book, which is to diagnose the structural inequalities and forms of domination that obtained in the French literary field during the period of decolonization (from 1945���1967), and to show how African writers and publishers actively negotiated these contexts. The book shows how the material contexts of literary production and reception (from paper shortages following WWII and anthology culture, to self-publishing and the distribution networks of Pr��sence Africaine on the African continent) were intrinsically linked to ideas of autonomy and aesthetic freedom.

Rama Salla Dieng

Your analysis takes place in a specific political context: To what extent was the French language a battlefield of literary resistance or revolution between editors and authors? And, what were the roles of literary translation in such a vibrant context?

Ruth Bush

This is such an important question. The French language has been, and continues to be, a battlefield, shaped by political contexts and institutions such as the Acad��mie Fran��aise, the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, and respective national education systems on the African continent. Senghor acted as a passeur for many African writers in the 1950s and 1950s, given his close friendship with Paul Flamand from Editions du Seuil, we can see his influence too in some relatively conservative decisions about language and genre. Literary prize culture has also been a space for consolidating the status of hegemonic languages, as seen in the institutional history of the Grand Prix Litt��raire d���Afrique Noire.

The ���language question��� continues to spark avid debates concerning the ���Africanization��� of French (seen in work by Ahmadou Kourouma, Boubacar Boris Diop, and Tobias Warner���s recent book. Overall, it often seems there is less inguistic experimentation in francophone African writing than in anglophone African writing���though this is changing, and partly through contact with other media. Language varies hugely, from the urban Wolof of Dakar, which blends in French and English, to Nouchi in Abidjan to Camfranglais in Yaound��. There are of course literary works that use these spoken registers in the francophone space, but still relatively few. The arguments made for producing literary texts in African languages also varies widely across francophone sub-Saharan Africa, and there have been important initiatives here. The publishing scene has, I think, been less concerned with material presentational details in publishing such as glossaries, footnotes, and italicization that have attracted widespread polemical comments in the anglophone space.

Literary translation clearly has an important ethical and social role to play in the African publishing landscape, but faces challenges in terms of sustainable funding models and training support. These challenges are structural and political. The final chapter of Publishing Africa in French discusses the French translations of novels by Amos Tutuola, Chinua Achebe, and Peter Abrahams. It shows how translators appropriated these writers��� work in ways that enriched the French language, and in ways (especially in the case of Tutuola, translated by Raymond Queneau) that often marginalized the author���s subjectivity. This is also a structural issue, where translations of African works have continued to be mostly produced by non-African translators based in the global North. There is an urgent imperative to translate and re-translate African literature. This imperative fuels ideological debates concerning pan-African identities. It���s also underpinned by the material realities of the African literary commons (the pool of linguistic and imaginative resources on which writers draw). My current book project explores new archival sources on the translations of early francophone African “classics,” and research on more recent initiatives to build literary translation infrastructure on the African continent through independent publishing, prizes, festivals such as Bakwa, C��ytu, Cassava Republic, Writivism, or the Mabati-Cornell Kiswahili Prize.

Rama Salla Dieng

With Claire Ducournau (Universit�� Paul-Val��ry Montpellier 3), you led an AHRC-funded project on Popular Print and Reading Cultures in Francophone Africa, which digitized the pioneering francophone African magazine AWA: la revue de la femme noire (1964-1973) can you please tell us more about what inspired you to focus on AWA? Was it a fascination for Annette Mbaye D���Erneville, one of its founders, or the idea of francophone women organizing in the immediate post-independence period?

Ruth Bush

It was both of these things which inspired this work. This project was a collaboration between myself and Claire Ducournau, alongside the Mus��e de la Femme-Henriette Bathily and IFAN-Cheikh Anta Diop in Dakar. Annette Mbaye d���Erneville is very well known in Senegal for her inspiring work as a journalist and former program irector of the national radio, and poet. She had a very popular radio show called Jigeen ��i degluleen (Women, listen!) in the 1970s and 1980s, and is still known as “Tata Annette” by many people today. The digitization of AWA: La revue de la femme noire was accompanied by the production of a multimedia exhibition, held in Dakar, Montpellier and Bordeaux in 2017���19. I became interested during my PhD in print culture that existed on the African continent beyond the contours of the French literary field and its institutions and came across AWA while working in the National Archives in Senegal in 2009. It jumped out as a fiercely independent publication produced in Dakar at the Imprimerie Abdoulaye Diop at a time when most press was dominated by French-owned monopolies.

AWA���s blend of content is very eclectic: political news, profiles of inspiring career women and celebrities (Younousse Seye, Miriam Makeba���), fashion photography, literary texts by writers including Birago Diop, Virginie Camara, Joseph Zobel, and translations of Cuban and American writers. The readers��� letters pages are particularly fascinating and give a glimpse of how the magazine curated correspondence with a network of readers in West Africa, and further afield in Brazil, Martinique, Eastern Europe, and Israel. This was a magazine that was also actively read by women in Senegal, albeit an elite part of the population. The traces of female solidarity across borders are inspiring. AWA���s editorial team were mostly female, though many men contributed to its pages, offering advice and pointers which might be read as mansplaining today, but which were clearly integral to how the magazine���s founders saw the need for collaboration and “complementarity” between genders at this point in history.

Rama Salla Dieng

You explain in an insightful article titled Mesdames, Il faut Lire! that AWA was more a glossy magazine interested in ���re-fashioning��� la Femme Noire, and preparing her for the task of nation-building; does this mean that AWA did not have a feminist consciousness?

Ruth Bush

AWA did not explicitly describe itself as “feminist,” and at times actively rejects the term. But its militancy lies in its form and material history. Retrospectively we might position AWA within the plural feminist movements of the 20th century���especially the idea of the “Modern Girl,” which has been traced in the parallel women���s magazine culture from Japan to Egypt to the United States in this same period. But AWA is not a highly commercialized magazine���it received very limited revenue from advertising, and there are, for example, no adverts for skin-lightening creams found in other magazines of the period. AWA���s contributors wanted a space in which to debate how to combine the pleasures and challenges of womanhood with the task of nation-building, through reproductive labor, and through new career avenues, from politics and law, to being a sports woman, secretary, or radio presenter. It���s also key to situate AWA in relation to women���s associations and women���s local level community organizing across francophone West Africa in this period and to recall again the bias of AWA towards a certain elite segment of the population. This is something the editorial team were clearly AWAre of and attempted to tackle in various ways in response to calls from their readers.

Rama Salla Dieng

If AWA still existed, what in your opinion, would it look like today?

Ruth Bush

When the exhibition was launched, there were a couple of people who contacted us to say they were inspired to start a new AWA magazine. I don���t know if those initiatives have yet come to fruition, but it���s exciting to think that historical examples can inspire new incarnations. AWA���s longevity was stalled by a lack of funding and its desire to retain complete autonomy. The editors refused to sell the magazine to French press entrepreneur, Michel de Breteuil; Breteuil subsequently launched his own women���s magazine, Amina, which continues to be produced and widely distributed today. In 2018, an American artist, Fahamu Pecou, made a painting, exhibited in NYC, inspired by AWA. His painting, titled “Jig����n Bu B��s Fenkna,” features AWA���s masthead against the indigo dye found in West African fabrics, superimposed by portraits of two strong and strikingly dressed female figures. One is masked and the other stares directly at the viewer. I think that AWA would exist in the digital realm inhabited by these two women, if it still existed. It would continue to be bold in content, beautiful in aesthetic, and I hope it would retain its founder���s sharp sense of humor!

Rama Salla Dieng

If you were to cite three lessons from women organizing offline that you learned from your work on AWA, what would those be?

Ruth Bush

One, retain autonomy and own the means of production (or borrow them from good friends). Two, remember who your readers/public are and listen to them. And, three, keep laughing.

Rama Salla Dieng

What three recent novels from francophone writers would you recommend? Why?

Ruth Bush

I���ve been reading lots of African campus fiction recently, in French and in English. I enjoyed Mbougar Sarr���s De purs hommes, Fran��ois Nk��m�����s Le cimeti��re des bacheliers, and J��r��me Nouhoua�����s Le piment des plus beaux jours. They show���in very different contexts���how fiction can nourish reflection about institutionalized, bureaucratic and dehumanized spaces in the university. I also read V��ronique Tadjo���s poetic meditation on the Ebola crisis this summer���En compagnie des hommes���and was once again impressed by her stunning command of narrative voices.

Rama Salla Dieng

In the context of ���fallism��� and ���decolonial��� claims in South Africa, the UK, etcetera, what are your views on the future of ���La Francophonie���?

Ruth Bush

I���m very interested in how these “decolonial” claims are echoing in francophone spaces on the continent���especially in public universities, which are suffering the structural effects of the LMD system, massification and ongoing aftermaths of structural adjustment policies, and which are increasingly multilingual spaces. Colleagues in those universities have suggested that these debates about decolonizing the curriculum and the staff body took place much earlier (e.g. in 1968 student protests. There remains an embedded pedagogical tradition inherited from the French higher education system, but initiatives such as the Ateliers de la Pens��e are pushing at the boundaries, rethinking epistemic diversity and the ecology of knowledge production and circulation on the continent. The ways in which epistemic diversity can encompass multilingualism, without reproducing imperial paradigms or hierarchies, is an important next step. I think translation���as a creative practice, an ethic, and writerly craft���has a crucial role to play here. I���d be interested to hear your thoughts about this question, Rama!

Rama Salla Dieng

Are you a feminist yourself?

Ruth Bush

Yes. I grew up with a feminist historian mother who convened Women���s Studies reading groups in our living room in the 1980s and early 1990s. The matriarchs of my family have been very important figures in my life: one working-class grandmother who grew up in Northern England at a time when women were not encouraged to pursue education, lived through the difficulties of bringing up children during WWII, and retained a strong and intelligent sense of who she was. My other grandmother was from a middle-class background; she did study at university and went on to campaign actively in the peace movement, taking me and my brother on marches when we were small. My mother was never dogmatic about imparting her views, but I see now how much has rubbed off on me, especially since becoming a mother myself last year and facing a new set of challenges defined by this changing aspect of who I am. I enjoy reading feminist writers of fiction and non-fiction���of late books about motherhood (Adrienne Rich, Sheila Heti, Maggie Nelson, Leila Slimani). As a feminist, I try to support women colleagues, students, friends, and strangers whenever needed, and to anticipate situations where gendered injustices (including issues affecting LGBTQ+ communities) might arise. These everyday forms of feminist practice are essential to building a more equal forms of society.

Rama Salla Dieng

How do you practice self-care?

Ruth Bush

Self-care very often comes in the form of a piece of cake and a cup of tea. Since having my daughter, I am also much stricter about my working hours. Academic work can easily fill the whole week, but I find I am more relaxed if I spend weekends with friends, at the park, and pottering in the garden, and keep my evenings screen free as far as possible. I am also now trying to reduce my overseas travel for work���this is partly for reasons of self-care and recognizing the benefits of slower modes of thought and reflection, but also due to the unsustainability of long-distance air travel in the context of our shared climate crisis.

Women’s Political Consciousness in Senegal