Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 197

November 17, 2019

The politics of Thanksgiving in Ethiopia

[image error]

Irreecha. Image credit Serawit Bekele Debele.

The Irreecha, which takes place at the sacred lake of Arsadi, is an annual ritual celebrated by the Oromo and other peoples at the end of Ethiopia���s rainy season and when blue skies usher in September/October. My book, Locating Politics in Ethiopia���s Irreecha Ritual, explores the country���s politics by making this popular thanksgiving ritual its entry point. The book is about (re)centering ���other voices��� that hegemonic structures and discourses silence. It is about the unemployed youth, women, elderly and spirit mediums whose take on politics and religion rarely finds an outlet because their meaning-making processes, practices and experiences do not always mobilize conventional vocabularies and venues.

In the book, I situate Irreecha in the context of Ethiopia���s post-1991 socio-political transformations, following the toppling of dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam by the current ruling Ethiopian People���s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The decades under EPRDF���s rule are marked by profound changes in the socio-cultural, economic and political domains.

With the introduction of ethnic federalism, previously marginalized groups of people enjoyed a certain degree of freedom to promote their ethno-religious and cultural heritages. Owing to this momentum, Irreecha became popular and it received attention from various sections of Oromo society. A previously marginalized ritual performance was now endorsed by Oromos across educational, generational, religious, gender and class differences. Soon, it became one of the most defining elements of an Oromo national identity: a highly politicized site where Oromo identity was asserted and celebrated. What was once a local ritual, confined to Bishofu (a town formerly called Debre Zeit) and its surrounding rural areas, expanded to become a national celebration. Besides its (re)positioning in the discourses and narratives of national identity, Irreecha also attracted the attention of politicians of divergent persuasions for ���doing politics.���

The post-1991 Ethiopian state under EPRDF, while initially open to the political expression of Oromo and other groups, was soon characterized by increasing authoritarian tendencies leading to dwindling possibilities for open popular political participation. Irreecha came in handy to channel grievances, criticisms, resistance and alternative political propositions against state dictatorship and the lack of freedom. As such, the ritual became a launching ground for Oromo identity and emerged to be central to articulating contemporary political demands.

This reached a climax in the #OromoProtest years of 2014-2016, when the youth openly protested against the then government. The October 2016 Irreecha celebration was notable for the pronouncement of the slogan ���down down woyane��� (down down TPLF)���a reference to the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, which had evolved into the then dictatorship. Against the backdrop of years of protest, October 2016 was a moment when the Oromo youth (mostly known as Qerroo) openly showed ���the will not to be governed��� and demanded change at all costs.

The government reacted by by declaring a state of emergency that lasted for a few months. Despite being remembered for the death of hundreds, it is at the same time significant as ���a point of rupture��� that ushered a transformation that led to the change in the political domain in today���s Ethiopia.

This is the socio-political context in which my book arose. In the course of conducting research for it, I asked: what constitutes politics from the point of view of various stakeholders? In what ways do state politicians and their opponents, (mainly the Oromo Liberation Front) and their respective supporters appropriate Irreecha as a political space to mobilize the populace around their ideologies? How do grassroots politics operate at Hora Arsadi (the sacred lake where the ritual takes place) and what are the mediums through which these politics are articulated? How do political subjects shape how we understand political processes in Ethiopia in particular, and Africa in general?

At the same time I pondered if we can ascribe a singular and coherent meaning to Irreecha. For example, is it really a monolithic spiritual/cultural event/practice/performance? How do the tensions between pan-Oromo (Orommuma) and pan-Ethiopian ideologies play out at Irreecha? Does Irreecha have a history(ies) that speaks to and enables us to understand broader cultural/religious and socio-political processes in today���s Ethiopia? How do we account for archives and voices that hegemonic narratives about Irreecha omit?

As the title suggests, the book is an attempt to find politics elsewhere, as it is practiced by those who are on the margins. The book goes beyond interpreting Irreecha as solely an Oromo ritual and situates it within a wider framework, so as to interrogate the deeper political and religious realities of and practices in the country. By locating Ethiopia���s politics in a ritual most Oromo political elites confine to the limits of Oromo national identity, I tried to situate the Oromo political struggle as well as Irreecha within the wider national context.

Irreecha offers a window into contemporary political issues. I believe the ritual can be used to rethink the meaning of Ethiopia and enrich that meaning by embracing various narratives. Towards this end, it is high time for scholars to pay attention to other vocabularies and ways of articulating politics. In this spirit, I hope the book stirs much-needed conversation and engagement with the meaning of politics, political subjectivities and the production of political spaces other than those of the state, civil society and political parties.

History time

Lusaka, Zambia. Image credit Bengt Flemark via Flickr CC.

Namwali Serpell���s novel The Old Drift arrives at a moment in contemporary African literature deeply committed to revisiting the past. The thicket of historical novels released in recent years overwhelms: Yvonne Owuor���s Dust (2013), Jennifer Makumbi���s Kintu (2014), Yaa Gyasi���s Homegoing (2016), Novuyo Tshuma���s House of Stone (2018), Ayesha Attah���s The Hundred Wells of Salaga (2019), and Way��tu Moore���s She Would Be King (2019) were joined most recently by Maaza Mengiste���s The Shadow King (already optioned for cinema). What���s more, these recent novels join a field already populated by breakout historical hits such as Chimamanda Adichie���s Half of a Yellow Sun (2006) and Zakes Mda���s The Heart of Redness (2000). Things Fall Apart is itself a historical novel so we could even argue that the African novel emerges precisely to address the problem of history.

When theorized, the historical novel is most frequently understood as a nationalist undertaking that affirms the nation through literature or, as is the case more recently with various postcolonial historical novels, critiques it, excoriating its material and political failures.

True to form, Serpell���s The Old Drift tells mainly a Zambian history. And like many historical novels, this history unfolds through a series of interconnected chapters that trace one sprawling Zambian family���s 20th century. What counts as Zambian is complicated from the start, however, as the white pater familias, who recounts his arrival at Victoria Falls in 1901, is a mediocre racist British colonialist who stays on to become a postcard photographer. As the novel progresses, its Zambian ambit includes the family���s Italian, British, and Indian branches, as well as its indigenous Tonga and Bemba ones. Zambia���s proximity to Zimbabwe������Zim or Zam?���one character asks���forms another through line in the book so that Zambia���s history is always already both local and pan-African; matriarchal and patrilinear; international, multilingual, and interracial. But it is the stories of individuals that flesh out the trajectory of the nation.

We meet people from across the social and economic and racial spectrum: sex workers who become hairdressers, HIV/AIDS researchers, dam builders, teachers, tennis players, wig sellers, and even the astronauts who spearheaded Zambia���s space race to the moon, which Serpell has written about here. For indeed Serpell writes actual history.

As she puts it in the book���s acknowledgements, ���The Old Drift includes many fictions and quite a few facts,��� a central one of which is the monumental fact of the Kariba Dam. Located in the Zambezi river between Zambia and Zimbabwe, the Kariba Dam forms the world���s largest man-made reservoir still in continual use for hydroelectric power.

Two improbable lovers escape Italy early in the novel to administer the construction of the dam. Circuitously tracing the dam���s disastrous history, Serpell recalls the deaths involved in its construction in 1958, six years before Zambia���s independence. ���So many men��� died���the majority of whom were African locals: some ���died in a collapsed tunnel��� while others ���plunged seventy metres into wet concrete when a platform collapsed.��� In a brief essay on the Hoover Dam by Joan Didion, she also recalls the men who lost their lives ���to make the desert bloom.��� But unlike at the Hoover Dam, on the borders of the American states of Nevada and Arizona, where a plaque memorializes these losses, Serpell���s novel must do this salvage work in fiction instead, because the state has buried these everyday histories beneath the more triumphalist fictions of national progress and technological advance. As the gravestones at The Old Drift burying ground bemoan, so many of the dead resurrected in this novel are otherwise ���Unknown! Unknown!���

The dam���s creation relocated abundant wildlife������lions, leopards, elephants, antelopes, rhinos, zebras, warthogs, even snakes,��� ���and the project forced approximately 57,000 Tonga people to resettle elsewhere. Their displacement onto less arable lands had dire and ongoing economic consequences, made even harder by the periodic flooding caused by the new dam.

And so at the book���s end, set in the near future, Serpell imagines that the descendants of those who constructed Kariba Dam inadvertently become those who destroy it, annihilating this massive symbol of exploitation and devastation. A trio of friends (and lovers)���Jacob, Joseph, and Naila���set out to protest the government���s increasing technological control over everyday life, but instead they bring about a flood of biblical proportions accidentally terminating the family line by drowning Naila, the story���s last pregnant protagonist.

A novel this large in scope, that plays with genre, too, defies neat review. However, its turn, at the end to an Afro-future freed of this symbol of man���s dominance over the natural world aligns neatly with its focus throughout the rest of the book on a host of other technological dreamers. In addition to the Zambian astronauts, one character makes the development of an AIDs vaccine the centerpiece of his life���s work, while his illegitimate son works furiously to perfect new drone technology. (Here is another instance of Serpell���s art imitating life, for drones are increasingly used on the continent for delivering medicine to remote areas.)

The historical novel exists then to help us understand our present as much as our past, so that we might envision other schemes for thinking about tomorrow that extend beyond the quarantine of our present. Serpell���s focus on the innovators who have dared to think otherwise is no exception.

But there is a postmodern narrative thread that operates like an intermittent Greek chorus to comment on the characters in the novel through the collective voice of a swarm of mosquitoes. They regularly caution us about the role played by accident in history���s haphazard trajectory, with the mistaken destruction of the dam providing one such example. What causes things to happen is not only the historical forces of domination, racial capitalism, and patriarchy that the novel interrogates, but also what the mosquitoes praise as ���that tiny chaos,��� randomness and error that disrupt political and social agendas. This force of mishap and misrule renders the future opaque, reminding us, too, that the past is as heterogeneous and unpredictable as any future we dare imagine.

November 14, 2019

The (Im)possibilities of Ugandan patriotism

Kampala, Uganda. Image credit Oli Matthews via Flickr (CC).

I am not patriotic. This country nauseates me. This country has not given me reasons to have or even express devotion. This country will kill me and walk over my body on its way out. This country has already killed me. So many times over. Without flinching. Without remorse. I was the target. I did not get caught in a crossfire.

A few days after moving to Entebbe, you realize that the road along which you stay has been in the news before. You do not watch the news. You deliberately avoid the news. You care for your mental health. But there���s news that finds you. You do not look for it. It finds you in the form of warnings. Women are getting killed in such chilling spectacles. We say their names. We try to remember them as more than just another dead woman. They deserve better. The news cycle, as it always does, eventually moves on.

Two months later, you find a cosy nook in a gated compound. You move to the clean air of Entebbe town. You are walking along the road from the house to catch the bus to work when it hits you. Nansubuga Gorreti. Kasowole Aisha. On some such morning in 2017, the residents of this area woke up to find bodies. Mutilated. Dead. Exactly five weeks apart. That���s what the news reported. Sometimes with grim images. The news, it is always an abstract concept, a far-off thing that you watch to know what is happening to the grand idea of the nation. That is, until it is right outside your door. It is not news then. It is a chilling reminder of helplessness, the senseless kind. You get a bottle of wine on your way back. If we die, we die.

Goretti and Aisha. You think about them every morning as you walk to the bus for work. Life seems normal here. Going on as it should with the man that sells roasted sausages outside the supermarket and the lady that sells fresh fruit right next to him. Everything seems normal. You wonder if you had been here on either of those mornings if everything would have been normal. You want to ask them, the people, if they remember, if it bothers them that whoever did that could be laughing with them at the boda boda stage, how long it took for the “normal” to return after those mornings.

In the Netflix series, Sex Education, when a photo of a teenager���s vagina is leaked to her classmates, the victim faces the threat of all the consequences that come with revenge porn. The photo, however, has no face and therefore the owner is being blackmailed to own up to it. She tells her friends about it and one of them owns up to it at the school assembly when the principal asks. To the principal���s surprise, one more person stands up and says, no, it is my vagina. Another person stands up and soon, the whole school is up saying, it is my vagina. Frustrated, the principal says, it cannot be all your vaginas!

The trick here is that one person can be shamed for the photo, the whole school cannot.

On a Saturday evening after grocery shopping at Millennium Supermarket located in the heart of Kisementi, the Kampala middle class hub, you order a Safe Boda to take you home. The rider calls and you ask him to find you in front of the supermarket. When he gets there, his bike is “arrested” by the other riders who work at the boda boda stage (where the boda bodas wait for customers). Only those who work at that stage are allowed into this area, and there is a sign at each end threatening a heavy fine. He is pleading with them to let him go, he did not know. The riders at the stage are very angry and are not giving him a chance to construct a full sentence.

They ask you to order another Safe Boda and leave them to finish this. They are threatening him with all sorts of things; including taking him to the police station. You know the violence that will happen as soon as you leave. You insist it was your fault and say you will not leave without him. Eventually, they let him go “for his customer���s sake.”

The trick here is that none of the threats can be followed through if you are taking the blame. Class privilege.

In June of 2018, there is a Women���s March to demand justice for the lives of Aisha and Gorretti and so many women like them that have lost their lives senselessly. It is impassioned, fearlessly fueled by Dr. Stella Nyanzi���s cheerleading skills. There is a lot of emotion caught in your throat. Here, in this Kampala, women, queer people, sex workers marching. It feels surreal. There are different signs about the importance of women���s lives (imagine that) as well as photos of Aisha and Gorretti and other women like them who have lost their lives senselessly. Yours says, fuck the patriarchy. There are some men, holding the same signs.

They are there for the women.

For the women.

Some are (obviously) lauded for showing up for the women.

My friend got arrested by the traffic police. They did not give him an explanation why. They were simply having a bad day and he happened to be the person who they could exercise their authority over for laughs. He was not allowed any calls and was not charged or whatever the law requires. He was, however, locked in a cell and his car impounded. He spent a night there before his worried father managed to track him down. His father is a high-ranking army general, unbeknownst to the officers who made the arrest. My friend was released with many apologies. Someone probably got fired.

My friend and people like him, people with that kind of privilege, are not the targets of the police. It is the people who can go missing for days with no one to look for them, or whose people have no access to the technology to track them down. It is the people who, if found in a cell, would need to beg to be released. These are the people the police target, people who would not need profuse apologies for unlawful arrest, people for whom, ���we would not have arrested him if we knew he was your son��� could never be an option.

In the book, Race After Technology, Ruha Benjamin describes how ���tools of social exclusion are not guaranteed to impact only those who are explicitly targeted to be disadvantaged.��� They wonder if this knowledge is enough to rally more people against social structures that benefit some and work against others. Part of being an ���ally��� is an exercise in this.

In this country, however, the concept of being an ally is a laughable one.

High profile politicians with state security have been killed in broad daylight. You might die because you are queer. You might die because you are a woman. You might die because the healthcare is trash���we know a lot of those. You might die because you literally cannot afford to live. Not a physical death but a never-ending agonizing one where you are always hanging from the precipice, one push away from the final destination all the while hoping that what killed Aisha and Goretti is a news item, far-off and not at all connected.

I am hungry for a love that my country cannot afford ��� A love that has mapped out the possibilities of my existence and made room for each one of them. ���H(Angry), Poetra Asantewa.

There is the popular proverb that talks about how first they came for the Jews, and the rest thought they were safe until eventually no one was safe. That is not the case for anyone living in this country. Women are experiencing physical, emotional, and psychological violence at the hands of men. Queer people are living under the threat of death. We are all in the firm grasp of a national security epidemic. This is the place to recognize that our struggles are connected. To say we are “allies” would be to delude ourselves into thinking that some of us are safe. We are not safe.

Out of the pigeonholes

Image via Charles Etubiebi on Facebook.

Victor Chimezie is a Nigerian actor who hopes to make it big in Hollywood. At long last, his agent lands him a part in a major studio production���an action film that promises to be a blockbuster. The catch, however, is that the project is premised on an all too familiar notion���namely, that Africa is nothing but a war zone, a place where child soldiers run amok. The ambitious Victor has convictions: he had vowed never to appear in such a film, but the opportunity, odious as it is, will mean good money, and it may lead to other, better projects.

The actor���s dilemma forms the core of Africa Ukoh���s remarkable play 54 Silhouettes, which offers a stinging critique of Hollywood���s penchant for pigeonholing Africa and Africans. Writer-director Ukoh recently transformed 54 Silhouettes into a one-man show���a vehicle for rising Nollywood star Charles Etubiebi, who performs all the parts. ���The title,��� in Ukoh���s words, ���alludes to the perception of a culturally diverse people as a homogenous block���54 being the number of officially recognized African countries at the time the play was created (it was actually 53 while I was writing it because the Sudan referendum was in process).���

The play will have its New York premiere on November 20th, 2019, at the prestigious United Solo, the world���s largest solo theater festival, which celebrates its 10th anniversary this year.

���The play seeks to confront issues of African identity and representation in global media,��� Ukoh told me. ���It seeks to grapple with the complexities of the portrayal of Africans and ask questions about creative responsibility.��� 54 Silhouettes suggests a sort of love letter to Nigeria���to the country���s cultural and linguistic dynamism. ���A big part of my writing style was influenced by the sharp-tongued and delightfully raucous nature of Nigerian conversations���particularly from my secondary school experience in Jos, Plateau State���and 54 Silhouettes was the first work where I finally got a good technical handle on how to translate that into dramatic form,��� Ukoh said.

���I���m always looking to tell stories that are uniquely Nigerian/African yet connect with global audiences,��� he added. ���There���s a uniqueness of perspective, of style, of aesthetic, of form, that is tapped into when the story isn���t just about Africa but from Africa. There���s also a remarkable range to African storytelling because of the multiplicity of cultural influences we have engaged with.���

In Etubiebi, Ukoh has found a performer ideally suited to the task of shattering stereotyped notions of Nigeria and Nigerians. Born in Kano but raised in Jos, Etubiebi attended the illustrious National Film Institute, where he crossed paths with a number of other rising stars and future collaborators, from directors to scriptwriters to fellow actors. He and Ukoh, a trusted artistic partner, were ships passing in the night during their time in the National Youth Service: by a curious twist of fate, both ended up serving in the same Nigerian state, though on successive years.

While still a student, Etubiebi maintained a steady work schedule, appearing on both stage and screen. Even before beginning his university studies, Etubiebi was asked to appear in a film that, while never released, was a useful learning experience for the young actor, who, growing up in Jos, had always aspired to earn a living as a performer. His uncle owned a video store in the city, and Etubiebi would often rent the latest Hollywood hits. (���Sweet, sweet VHS!��� he recalls with infectious nostalgia.) The uncle also made his own movies, which often starred members of his own family, with one conspicuous exception: Charles Etubiebi, who, due to various quirks of scheduling, was never available for these family-centered shoots, but who has more than made up for it with a thriving career in the movies, on television, and on the stage.

After relocating to Lagos, Etubiebi became co-director of Theatre Emissary International, a Nigerian organization that not only produces plays, but also seeks to connect aspiring performers and playwrights with opportunities both at home and abroad, all while working to advance the cause of theater education.

I spoke with Charles Etubiebi as the actor prepared for his New York debut.

Noah Tsika

What was it like growing up in Jos?

Charles Etubiebi

Jos is a calm, amazing city to grow up in. Everybody knows everybody. Everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who knows somebody ��� I went to one of the same secondary schools as [Nollywood star] Desmond Elliot ��� Everyone���s interconnected somehow ��� I met [Nollywood director] Kenneth Gyang in Jos, at the National Film Institute.

I went to Lagos in 2013. It���s supposed to be the center���the place where dreams come true ��� It���s this big city in which everything is happening, and you want to be a part of it ��� And then, around March 2013, my friend Taiwo [Afolabi, the founder and director of Theatre Emissary International and the producer of 54 Silhouettes] called me and said, ���We got this gig in Sudan.��� Theatre Emissary got into the Al Bugga International Theatre Festival [in Khartoum]. That was when I registered for and became a part of the International Theatre Institute [ITI], the performance arm of UNESCO. So, we went to Sudan in 2013 with a two-man performance piece, 2 Characters Undefined [by Nigerian playwright Paul Ugbede]. Before we went, we rehearsed the play for nine days, including at Benue State University, just to test it out, to see the students��� reactions to it. And when we got to Sudan, we performed it as part of a festival, a competition���different countries were performing, competing. I got the award for Best Male Actor���that was shocking. And that gave me the drive to say, ���You know what? You���re still on the right path. You should be doing this.��� So, I went back to Lagos, and ��� it was another dry spell. I was supposed to work on a TV series, but it got cancelled. But sometime around November, a friend of mine called me and said, ���A friend of mine is in Jos, he���s got this new play called 54 Silhouettes������ And I ask, ���OK, how much are they paying?��� And he says, ���Well, we���re all starting out, and we have to help each other ������ And I���m, like, ���OK ��� I mean, I���ve got bills, but ��� OK.��� So, I call Africa [Ukoh, the friend-of-a-friend in question], and we hit it off immediately. I read the script, and I loved it. I went to Jos, and we started rehearsing.

We staged [54 Silhouettes] in Jos, and they loved it. We took it to Abuja, and they loved it there, as well. I go back to Lagos, I start going on auditions, calling all my contacts. I got my big break in a [2015] show called Desperate Housewives Africa. So I do that, and then from there I move to another set, and it just kept on going from there, from job to job to job.

In January 2018, I got accepted to go to a festival in Brazil, in Rio. I���d been to Armenia in 2016 for a Shakespeare festival, and someone [from that festival] recommended me for the festival in Brazil. At the time, I was working on this big TV program, so I was getting paid, and I could afford to travel on my own. The TV show was easy work���wake up in the morning, go on set, run my lines, rehearse with other actors, and then shoot. I had done that, at this point, for about two months, and I [wanted a new challenge]���so I asked [Africa] if he could change the play [54 Silhouettes] to a one-man play, and he said, ���You know what? Yeah, maybe I will!��� He sent it around July [2018], and then around August, I just went cold turkey on everything else���my TV subscription, everything. And I just read the script over and over again, and rehearsed ��� eventually with a director from Jos, on my time off [from shooting the Africa Magic TV series Forbidden].

Noah Tsika

What was it like working for Africa Magic?

Charles Etubiebi

It was cool! I mean, every actor wants to work there. It���s like working at a big studio. You���re shooting a show that���s going to show in 44 countries, for up to three years.

Noah Tsika

You���ve managed to maintain a balance between stage and screen. How would you describe your career in theater?

Charles Etubiebi

One thing we like to do as a company [Theatre Emissary] is to try to stage whatever play we���re working on in front of an audience, early on, to get feedback, which is what we did at Benue [State University], before we went to Sudan, and which is what I did in Lagos before I went to Brazil with 54 Silhouettes. In Brazil, most people who saw [the play] spoke Portuguese, but the play was translated [from English into Portuguese], and the translations were projected for the audience to see. And the audience wanted a second show���I was shocked! We couldn���t do a second show, because the schedule was packed, but [the audience response was encouraging]. I got back to Lagos and thought, ���What���s the biggest place we can take this [play] next? New York City!���

[But, before we started planning a trip to New York], we got accepted to the Lagos Theatre Festival, which is run by the British Council. We performed [54 Silhouettes] there, and this time Africa came to Lagos and directed it himself. And this is when I most enjoyed the performance, because when you work with someone who actually created the thing ��� Working with Africa, we have a special dynamic. We ate the play, we talked the play, and when we did it in Lagos, at the festival, I genuinely enjoyed being this character, and telling this story. It was absolutely amazing.

As an actor, I know that I���m supposed to cry on demand, but I don���t do that easily. But the last rehearsal we had [in Lagos] ��� there���s a scene where the main actor gives this monologue about how we as Africans have to confront stereotypes of Africans���what people see from far off. They say, ���Let���s just put them in a box and leave them there.��� No, we���re more than that. We���re like every other person. Before you can get to know us���who we really are���you have to really look. Don���t just chalk us up as ���black Africans������first of all, in Nigeria, we have many languages. Let���s just start there, first of all. So we���re a lot more than you see. Africa���s a big continent. Those lines [in 54 Silhouettes], about how we need to educate and reeducate the world about who we really are���at the last rehearsal, I got emotional. And Africa said, ���You���re ready.���

Noah Tsika

How does it feel to be part of this new wave of Nigerian artists���not just Nollywood artists, but Nigerian artists working in multiple media?

Charles Etubiebi

It feels amazing. It���s a good time to be an actor���to be a Nigerian actor. Especially at this time when more people seem to be looking at the continent. Just to be able to tell our stories. For me, one of the works I���m honored to have been a part of was [the 2016 film] 93 Days [about the containment of Ebola in Nigeria]. There are a lot of problems with Nigeria, but this was the one time we got something right. And to just be a part of that���to tell that story. And the work���the process, the rehearsals. If you were playing a real person, they would set it up so that you could meet that person. So I met [the late Dr. Ameyo Adadevoh���s] son���we sat and we had a conversation. And the weird thing is we look alike! We all know [Dr. Adadevoh] as this hero, but what I wanted to know was who she���his mother���was, what she was like as a person. This was a child who lost his mom on his birthday. She died on his birthday. He said that even on her deathbed, even as he was crying, she was asking him about his birthday, and his girlfriend���on her deathbed! She was so concerned about everyone else���she put everyone before herself.

At this point, I���m happy that we���re telling our own stories, as Nigerian actors. We���re telling stories that are particular to us. We���re telling the world, ���Look, this is who we are, this is what we���re about, and this is how you should address us.��� It���s important so that when we come here [to the United States], people know that, if I���m [auditioning] for the part of a Nigerian, I���m not going to be speaking in the same generic ���African��� accent that everyone has been expected to use. I mean, I love Will Smith [who played a Nigerian role in the 2015 film Concussion], but���

People are beginning to realize the importance of casting Nigerian actors in Nigerian roles���look at Bob Hearts Abishola. It���s a start���a Nigerian actress in a Nigerian role. That���s a start! And I���m excited that at this point in time people are beginning to look for the authenticity that comes from a Nigerian actor playing a Nigerian role. So, as an actor, it���s a good time, and it���s important to come over to this side, to represent yourself authentically here, in the United States���not just as a black actor, but as a Nigerian actor. But I���m also interested in playing non-Nigerian roles, and 54 Silhouettes is helping me with that, especially because of the accent work involved; it lets me play with accents. I met someone here recently, and, after I said, ���Hi, I���m Charles,��� he said, ���You���re from Nigeria?��� I���m, like, ���Yeah������ He said, ���I thought I wasn���t going to understand you!���

Noah Tsika

Could you say more about Theatre Emissary���about its origins and what the future may hold for it?

Charles Etubiebi

Theatre Emissary is a theatre company in Nigeria. We started out in 2012���just me and Taiwo. At that point, we were really just trying to find our footing. We would go out to festivals, like the one in Sudan, but we were also trying to find our footing in Nigeria, as well. Around 2013, we kind of disbanded, because everyone needed to do other things. Taiwo had to go to Canada, as a Queen Elizabeth Scholar at the University of Victoria. We reunited for 54 Silhouettes, and, with Theatre Emissary, we get to travel all over the world. But what we���re also trying to do, right now, is build a theater community back home, in Nigeria. What we���re trying to do is be that channel for Nigerian artists to reach the black world. We���re able to recommend Nigerian artists for various programs and festivals and other opportunities���including in China. We���re here to say to Nigerian artists, ���As much as you���re doing here [in Nigeria], there are opportunities outside for you���broaden your spectrum!��� Because so many Nigerian artists are working under some of the worst conditions, as artists, and they���re [still] doing very well. If they can do this well here, back home, what would the possibilities be���what would their potential be���outside? So, one of our goals is connecting Nigerian artists to opportunities outside of Nigeria. That���s one of the reasons we remain connected to ITI [International Theatre Institute], which is committed to taking artists from around the world. It���s about a convergence of the arts.

Noah Tsika

How would you describe 54 Silhouettes? What can audiences expect?

Charles Etubiebi

54 Silhouettes is a reintroduction to what it means to be Nigerian, what it means to be African. It���s about the need to look past stereotypes���lots of stereotypes. If I���m chatting with a woman on my phone, here in the United States, and she asks where I���m from, and I say, ���I���m from Nigeria,��� she���ll block me immediately! She���ll think, ���419 scam, or Ebola������ There are so many misconceptions. 54 Silhouettes is an in-depth look into what it means to be from Nigeria, about the heritage that we have, the kind of people that we are. It���s about an actor who is caught in this image���this box���that has been created for him, but it���s too small. He���s saying, ���That���s not me. This is who I really am.��� It is, in a way, an introduction to the American audience, here���an introduction to what it means to be Nigerian. Look at me for what I am. This is what I am. We are a proud nation. A nation of hardworking people. Things may not be the best, or what they should be [in Nigeria], but we still are here. We have passion. We have things that make us distinct. This is who we are.

Noah Tsika

And how would you, in your own words, describe what it means to be Nigerian? How do you conceive of your own identity as a Nigerian in 2019?

Charles Etubiebi

To be a Nigerian is to be relentless. No matter the odds, no matter what comes���relentless. The odds aren���t fair. You live in a country where the leaders aren���t really concerned about the masses. So, you���re on your own, to work, and make something of yourself. People often say that it���s a broken system���I think that it���s a system that would have been, with broken and unformed pieces everywhere. So what you need to do is pick up whatever pieces you can, create some vehicle, something that makes you mobile���get some form of mobility���and hope that, while you���re doing that, you can pull one or two people up, and hope that they pull up one or two people. I���m not trying to fix Nigeria. I���m trying to live my life, and help the people around me, and hope that they hold their hands out to other people. Because that���s how change starts.

What is home?

Union Square, NY, 2014. Image credit Michael Fleshman via Flickr (CC).

Professional mixed martial fighter, Israel Mobolaji Adesanya, is one of the finest combat fighters of modern times. Adesanya was born in Nigeria before moving to New Zealand when he was 13. Both Kiwis, as people from New Zealand are known, and Nigerians claim Adesanya, and he has fans in both countries. Internationally, he has competed under the New Zealand flag.

Adesanya also doesn���t shy from speaking his mind. In mid-August this year, at a press conference preceding one of his fights, Adesanya was interrupted by a member of the audience. The man wanted to know which country Adesanya considered to be home. It is hard to tell if this line of questioning was innocent and random. It seemed odd for a press conference. But it is not unusual in New Zealand. Like elsewhere, in countries that identify with the West, whites have questioned the identity of black and brown people they consider ���immigrants��� and politics have moved to the right. In one instance, it resulted in tragic violence when a gunman murdered 50 worshipers at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand in March 2019. New Zealand First, a party that promotes a restrictive immigration policy, is in a coalition government with the ruling Liberals,

Adesanya seemed ready for it. From his reaction, it was quite obvious he was tired of explaining himself, tired of having to choose one country over the other and publicly explain why to random people at a press conference. Adesanya replied in a rather forceful and philosophical manner saying ���Home ��� I said home is where the heart is. I have Africa and Nigeria outline tattooed on my chest for a reason. Look at my skin, my (expletive) skin is black, do I look like a Kiwi to you?��� Adesanya made sure he addressed the issue of his appearance. Adesanya went on to list places he grew up in New Zealand before concluding that home is where one���s heart is.

Adesanya���s philosophical and symbolic reply to this line of questioning was akin to dancing in the ring against opponents. He referenced the images of Nigeria and Africa tattooed on his chest and their symbolism to his identity. He also reflected on the pride he feels when he flies back into New Zealand. He ensured that he gave gratitude to New Zealand, the country that raised him. This was a smart political dance by a man who had the awareness to appreciate the burden of belonging to two places at the same time and to the treacherous politics of loyalty.

Adesanya���s responses have not just occupied my mind because Adesanya was put to task to explain his loyalty. That happens all the time. ���Go back to Africa,��� a common racial slur is just one that white nationalists use to disenfranchise and deprecate black and brown people in the United States. US President Donald Trump used a similar card from a racist playbook against two black members of Congress, Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, a few months ago. His words were meant to remind these women of the perceived lesser value of their citizenship.

The concept of home is therefore something that black people, especially black immigrants are very aware of. This puts pressure on immigrants at all levels to express absolute gratitude to these countries that ���saved��� them when immigration in many instances, confines people to hard labor, in small peripheral spaces in the society, where immigrants live under a dark cloud of fear of backlash from the majority.

In the month of June, 2019, Rui Hachimura was selected ninth by the Washington Wizards in the NBA. Hachimura was a standout star for Gonzaga, and as basketball lovers we were excited to see him join other players of African descent in the NBA. Unlike Adesanya, Hachimura did not give a philosophical answer to questions about his home and identity. Hachimura identifies as Japanese, the country of his birth and where he was raised. Hachimura���s father, on the other hand, is African from Benin, a West African nation. His mother is Japanese. Hachimura���s home is obviously where his heart is���in Japan. There is no doubt he does not consider Benin his home and he doesn���t consider himself black or African either. And it is within every individual���s right to identify with one nationality or race when they are of mixed ancestry and nationalities.

This choice might be easy to make in Japan and other places. In the United States, this choice is complicated by the legacy of slavery and the ugly reality of racism���where race can determine if you live or die during a routine police stop or wellness check. And as Hachiumura will realize, some of the paths he will walk, have been paved by black people who fought against this systemic racism. Hachimura may also come to recognize that he has been connected to black people in the United States for hundreds of years, through Benin, his father���s country, and through the transatlantic slave trade that flourished from Dahomey Kingdom of Benin.

As my mind was sifting through these different responses from supremely talented athletes with African roots, I reached out to Wyclef Jean���s album, Welcome to Haiti/Creole 101 to revisit a dialogue on identity between a Haitian father and his son. This album has a powerful opening interlude, an excerpt from an interview with the late Jean Dominique, a very well-known Haitian journalist. His voice beams over the speakers:

I was 4 years-old when the US Marines left Haiti, I was a kid. And every time a Marine battalion passed in front of the house, my father took my hand and said: Don’t look at them. Don’t look at them. And every May 18th, the Flag Day, defiantly he put the Haitian flag in front of the house.

And I said: ‘Father what is that? What does that mean for you?’

He said: ‘That means that you are Haitian. That means that my great-grandfather fought at Verti��res. Never forget that! You are Haitian! You are from this land. You are not French! You are not British! You are not American! You are Haitian!’

Wyclef Jean must have had explicit intentions of reminding immigrants never to forget their roots and homes.

In his early life, former US president Barack Obama grappled with this question of home and identity. He captures this odyssey in his book, Dreams From My Father. He writes: ���The world was black, and so you were just you; you could discover all those things that were unique to your life without living a lie or committing betrayal.��� Obama is expressing his feeling on discovering home in Kenya. In this place, Obama was struck by the blanket of kinship he enjoyed freely amongst Kenyans. Obama was black, the people were black, and most importantly, this was his father���s land. Even though Obama���s heart may have not been in Kenya, he realized he was home. This place, where he could enjoy freedom without anticipating any boundaries for looking different from the majority, was home.

Can your home reject you? In the month of June, the Kenyan parliament recommended that Mwende Mwinzi, a presidential nominee for a diplomatic position, renounce her US citizenship before taking up this post. Mwinzi was born to a Kenyan father and a white American mother in the United States. Both Mwinzi���s parents relocated to Kenya where she grew up and has held various senior positions within government. Mwinzi has since taken her case to the Constitutional Court.

Mwinzi���s case is as interesting as it is confusing. Her heart is in Kenya, her home. Kenya is also her father���s land, yet she cannot get unconditional acceptance to serve her nation because of fear that the United States may claim her. This perceived tussle for loyalty and continuous suspicion between country of birth, country of residence and ancestry is one of the biggest dilemmas of immigration. Is home where the heart is? Or is home where one derives identity from no matter their ancestry and or roots? Or is home the lands that one���s ancestor���s fought for as according to Jean Dominique���s father? Or is home the place one can achieve freedom, a powerful sense of belonging and identity, and automatic kinship on arrival as Obama experienced in Kenya? The complexities surrounding the concept of home amongst immigrants is precisely why Adesanya danced around this question.

November 13, 2019

A cinema for (some of) the people

Promo image for the film Stroomop.

Driven by what seems to be a Hollywood-cum-nationalist fantasy, the film production house kykNET Films has created an enclave for mainly white Afrikaaner filmmakers to occupy a disproportionate amount of space on the silver screen, leaving the rest of South Africans��� stories untold. In a country plagued by inequality along class, race, and gender lines, we need more people telling smaller stories, rather than a few people telling big stories.

There is a common myth that people of color in South Africa are not a ���cinema-going��� audience, but according to a 2015 report by the South African National Film and Video Foundation, there is no unambiguous evidence to support this claim. Yet, of all South African productions released in theaters during 2018, the three highest-grossing films were in Afrikaans, featured predominantly white cast members and were all produced by kykNET Films. An absurd idea, given that only 13% of the population speak Afrikaans (and nearly 50% of cinemagoers prefer watching films in English or isiZulu).

KykNET Films, an affiliate brand of the kykNET satellite TV channels, produces Afrikaans-language feature films for theatrical release. It is a subsidiary of the multinational media conglomerate Naspers, which owns amongst many other brands, Media24, Multichoice, DSTV, Supersport, Showmax, and MNet.

A white Afrikaans-speaking population that has mostly maintained its economic and social privilege after the end of apartheid, has ensured a viable market for Afrikaans media companies such as Naspers. Naspers used to be the mouthpiece of the National Party during apartheid and after the end of apartheid cleverly repositioned itself within a consumerist discourse.

Although Naspers now caters for a variety of demographics, its cinematic theater releases are almost exclusively in Afrikaans and cater for white audiences. More concerning, however, is how Naspers���s repositioning has led to the segmentation of audiences along race, class, sexuality, and gender lines, while simultaneously avoiding any recognition of those differences.

The representation of group identity in cinema is important, because cinema, even when redefined for the multiple-screen digital context of today, has extraordinary power to construct our idea of the Other. The camera���s gaze is able to put power in the hands of those who look and decides to either empower or disempower those who are looked at.

Historically, cinema in South Africa and elsewhere has been limited in its representation of black, femme, and LGBTQ+ bodies. In a country where identity politics inevitably occupies huge amounts of space in our public discourse, it is important that our cinema contains progressive representations of group identities. A cinema that disavows the differences between classes, races, genders and sexualities, is an impotent one.

The 1996 South African Constitution explicitly challenges the arts, including cinema, to partake in reconciliation, reform, and nation-building. Yet, since the end of apartheid, South African films have tended to rely on Hollywood conventions and lackluster representations of some identities, prohibiting us from forming a national cinematic voice.

The three highest-grossing South African films of 2018 were Stroomop���an adventure-cum-drama about a road trip by a group of mostly white women in a self-help group; Ellen���the real-life ordeal of a coloured Cape Flats mother and her drug-addicted son; and the chick flick Susters (about three adopted daughters, including one black, of a white woman on a road trip to scatter her ashes). Collectively, these films do little to deconstruct the roots of colonialism and apartheid. Although these films are neither overtly offensive nor explicitly racist, they are forgettable. Predominantly white casts, as in Stroomop and Susters, constitute a concept of ���whiteness��� against which the few characters of color are immediately defined. The story worlds in these films are severed from the lived realities of most South Africans, allowing white viewers to enter and exit the theater without reflecting on themselves.

Given that close to 60% of Afrikaans-speakers in South Africa are not white, representing people of color should come naturally to kykNET. But the few attempts that have been made at telling these stories (for example, Ellen), fall short of the progressive representations the constitution calls for. These representations are harmful when ���standard��� Afrikaans (the official dialect of Afrikaans associated with the apartheid state and whiteness) and the Christian faith are equated to respectability. Ellen arguably sends a message, albeit discreet, that ���colouredness��� is an affliction that haunts the Cape Flats and whiteness is the solution to the problems.

Mainstream Afrikaans films can thus be seen as creating a cinematic world for white viewers to absolve themselves from historical baggage and escape into (and be trapped by) a barren Hollywood myth. The money it takes to produce one kykNET film could be used to produce at least three smaller films with broader thematic, artistic and discursive reach. If we are to take the constitutional mandate for the cinema seriously, we need to redefine the role it can play in a South African context.

Jennifer Davis: Fearless and visionary

Jennifer Davis and Oliver Tambo, New York, 1987. Image credit David Vita via the African Activist Archive.

Gail Hovey worked for the American Committee on Africa (ACOA), an organization that coordinated the sanctions campaign against apartheid South Africa, where Jennifer Davis served as research director of the American Committee on Africa (ACOA). Hovey remembers traveling to South Africa with Davis as observers for that country���s first democratic elections in 1994. ���If people are brave enough to vote, they deserve to have observers,��� Hovey remembers words from Jennifer Davis that stopped her and fellow elections observers in their tracks. A debate as to whether they should provide staffing in potentially violent spaces during South Africa���s 1994 election had been animated to that point.

Davis, who died October 15, 2019, at 85, connected Americans and Southern Africans beyond her capacity in elections monitoring. She began her career arguing with a teacher about the National Party���s rise to power in 1948. She continued through the university movement at home in South Africa. As a young adult, she engaged in protest alongside her husband Michael, who had served as an advocate with Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, both of whom would go onto to lead the largest liberation movement in South Africa, the ANC. When death threats, state harassment, and subsequent exile took them to New York City, the pair hosted Namibians and South Africans pleading their cases before the United Nations, and they assisted fellow lawyers in seeking funding for political trials. Within this sphere, she funneled some of the guilt she later expressed at leaving home into maintaining connections between the birth home and the new.

Home and exile had not been strangers to Davis in her life to that point. Her Jewish, German mother moved to South Africa and married her father during a tide of rising anti-Semitic nationalism in Europe in the 1930s. Jennifer was born just a few years after. Though she grew up physically removed from much of her mother���s family, the young child and her family received news from family as the Holocaust unfolded. In the book, No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half-Century 1950-2000, editors Bill Minter, the aforementioned Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr. wrote that ���For Davis, ���Never Again��� meant that every Jew should be an activist, resisting religious and racial oppression wherever it occurred.���

And so she was.

She then succeeded George Houser to serve as executive director of ACOA and the Africa Fund for nearly two decades, as international movements against apartheid reached their apex and as Southern Africans transitioned their domestic politics.

In this capacity, Davis often served as a link to Americans seeking to understand Southern Africa���s complexities, within and beyond their understanding of apartheid. Keeping with ACOA���s mission of moving Africa from the periphery of US foreign policy debates, Davis���s research undergirded much of the organization���s ability to connect with citizens of her new home. This ability came from a belief that sharing stories of the continent would help nuance it to Americans and, thus, change policy toward the region. Throughout, she continued to advocate for connections and, more than that, to advocate in the interests of Southern Africans. More than once, archival records have revealed her speaking her mind to Americans who she scolded as too sympathetic to gradual change and cooperation with the apartheid regime.

In her realm, she contributed to a dialogue that centered Southern African liberation as a continuing tenant of US civil rights work and helped to usher in the era of “global rights.” Alongside co-worker Dumisani Kumalo (post-apartheid South Africa���s first Ambassador to the UN, and who also died earlier this year) and American and Southern African activists, she facilitated public protest against the apartheid regime on university campuses, in front of government offices, and through shareholder activism, among other means. When Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act and���perhaps more significantly���overrode Ronald Regan���s veto of it in 1986, it codified federal restrictions on trading with the South African government. Davis and Kumalo had worked within grassroots coalitions to pass such legislation at local and state levels for years prior. While she focused her work on connecting two sides of the Atlantic, she remained equally emphatic that change work take place in solidarity and worked broadly within and beyond Washington DC, where she worked and lived during her life���s last decades.

Joel Carlson, a close personal friend and one of the attorneys whom she hosted, held meetings with prominent American attorneys that led to the formation of the Southern Africa Project of the Lawyers��� Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. Davis hosted him in New York as the pair worked frantically to find monies for a trial that would save the lives of thirty-seven SWAPO leaders under the Terrorism Act. The Lawyers��� Committee funneled monies into political trials and death inquests, including the trial of the Namibians, trials of the Cassinga detainees, Robert Sobukwe���s cases around his exit visa, and inquests into the deaths of Neil Aggett, Steve Biko, James Lenkoe, Isaac Muhofe, and more. In doing so, American lawyers materially connected their support for decolonization to Southern African colleagues working on it. In her capacity with ACOA, Davis managed much of the infrastructure of this relationship alongside stalwart American women, such as Jean Sindab and Gay McDougall..

Throughout all of this, Davis earned the distinction of being, as an SABC broadcast last week called her ���fearless��� and ���tremendously visionary.��� She had often called herself ���intense.��� Minter, Hovey, and Cobb would add ���analytical��� to that list.

Many Southern Africans, Americans, and allies from across the globe have no doubt viewed Davis���s passing as yet another bookend on the era of global anti-apartheid politics that transformed not just South Africa, but spaces like the United States, which viewed apartheid as a proxy in its own anti-racist struggles, and indeed global political advocacy itself.

Still others know Davis���s work, if not her name. Jackie Wilson Asheeke wrote in the Namibian newspaper, Windhoek Observer:

Sadly, so many builders of the foundation upon which an independent Namibia and a free South Africa were built, like Jennifer Davis, will not be remembered or appreciated. But, I think that���s ok with them. Their anti-apartheid work wasn���t for applause or riches, it was done because it was the right thing to do.

Indeed, the “rightness” was far more okay with Davis than the applause. To researchers such as this one, she as a subject was almost maddeningly difficult to access. I spent more than a decade calling and e-mailing her, having brief conversations, but always hearing her demure opportunities to discuss her own work. Within her sphere of action, she simply did not see speaking of her laurels as a priority. Those laurels, however, remain active in the connection between people engaged in anti-racist struggles on two sides of the Atlantic. With Davis���s influence, many of them found ways to be brave enough.

November 12, 2019

The virtual reality of Walter Sisulu

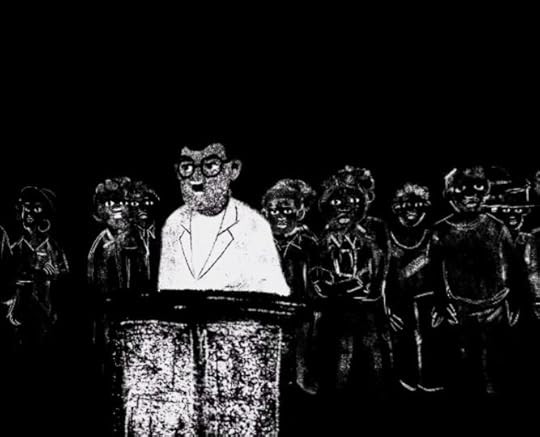

Still from film "Accused No. 2: Walter Sisulu."

When Walter Sisulu passed away in 2003, at age 90, some obituaries described him as ���one of Nelson Mandela’s earliest political mentors and his closest collaborator for half a century in the campaign against South Africa’s racist political order.��� The two men had served time together on Robben Island and Victor Verster prisons for conspiring to overthrow the apartheid state. As The New York Times concluded in its obituary, ���Mr. Sisulu’s political career was less celebrated than Mr. Mandela’s but not much less remarkable.���

One of the last public events associated with Mr. Sisulu before he went to prison was the Rivonia Trial where, along with Nelson Mandela, he was sentenced to life in prison. The short VR film ���Accused No. 2: Walter Sisulu,��� transforms archival audio of that trial into an immersive retelling of the courtroom drama as Sisulu, Mandela and other top anti-apartheid leaders defended themselves.

Produced by French filmmakers Nicolas Champeaux and Gilles Porte, the film has been screened at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, Munich International Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival and several other international documentary film festivals.

Still from film “Accused No. 2: Walter Sisulu.”

Still from film “Accused No. 2: Walter Sisulu.”The film places you first in the middle of the courtroom action, under the imposing judge���s seat and next to the witness stand. The 360�� animation is charcoal drawing style artwork, bringing a stylized element to the environment and weaving neatly with the scratchy audio recordings. Walter Sisulu is called forward and the interplay between him and the rest of the court begins. His defense attorney explores Sisulu���s background and then the imperious prosecutor Percy Yutar drills into him, all while he resolutely answers each inquiry. The filmmakers take advantage of their chosen form by morphing the size of the characters and periodically interrupt the court scene with metaphorical black circles and white squares to illustrate the struggle of the non-white African in South Africa. The courtroom scene ends as Sisulu reacts in frustration to Yutar���s interrogation, ���I wish you were in the position of an African in this country! I wish you were an African and knew the situation in this country!��� At the end of the film, we see a triumphal scene of Mandela���s later presidential inauguration, with Walter Sisulu at his side.

Sisulu, with Mandela and others, along with their influential wives (Winnie Madikizela Mandela and Albertina Sisulu), led the postwar movement to challenge the increasingly brutal policies of the white ruling government in South Africa. Mandela���s prominence has overshadowed his quieter ally internationally, an imbalance this film attempts to correct. The short VR story left me wanting to know even more about the subject and surrounding historical proceedings.

Walter Sisulu, born in South Africa���s Transkei, moved to Johannesburg for work in 1928 where he eventually met Mandela and became involved in nationalist politics. He held various jobs over the years���gold miner, a domestic servant, a baker and a factory worker���before establishing himself as a real estate agent. Along with other young ANC members like Mandela (then a young lawyer) and Oliver Tambo, (another lawyer), Sisulu helped build the ANC���s mass base and its alliances across racial lines.

Still from film “Accused No. 2: Walter Sisulu.”

Still from film “Accused No. 2: Walter Sisulu.”Sisulu also played a key role in the ANC���s decision to adopt violence in the wake of a 1961 police massacre of ordinary Africans protesting further restrictions on their movements via Pass Laws. He had been arrested and acquitted already before his arrest and sentencing in 1964. In prison he emerged, along with Ahmed Kathrada, as one of Mandela���s closest advisors. He was released from prison in 1989 along with Kathrada, a few months before Mandela, and lived to see the transition to democracy. (Some of his children ended up as government ministers.)

We continue to struggle in the 21st Century against the forces of racism, xenophobia, and corruption. South Africa has a journey ahead to fully achieve a society built on multiracial equality. The physical and rhetorical violence in the US, set free in the public square by the 2016 election, demonstrate how premature the expectations of a post-racial America really were. In the midst of these uncertain times, I look to the triumphs of our historical progress for insight and inspiration.

When the viewer first steps into the world of ���Accused No. 2,��� the epochal words of Mandela roll out to an animation not unlike a heart monitor, declaring, ������ I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all people will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal for which I hope to live for and to see realized. But, My Lord, if it needs to be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.��� The focus of this film is not, of course, on the charismatic figure of Mandela, but on his confidant Walter Sisulu. Champeaux and Porte have built an immersive world for viewers to be in the room as the anti-apartheid leaders displayed dignity in the face of ruthless oppression. This film creates space for reflection on lessons learned in past freedom struggles; particularly important as we continue to work for a better world.

Decolonization can���t just be a metaphor

"Museum conversations." Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).

In the museum world, particularly in Europe, conferences and workshops around ���decolonizing��� colonial collections and what to do with stolen artifacts turned ethnographic objects have become commonplace. Small parts of those collections are displayed in exhibition halls while much of the material culture and human remains from Africa are kept in boxes, locked up in basement storerooms. European museums often invite artists and activists from Africa and the diaspora to ���mine the museum.��� Namibian scholar and artist Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja names this ���practice of museuming��� as one that asks the victims of colonialism to handle its baggage.

The issue is pressing and it is taking place on the African continent too, which is how the Goethe-Institut Namibia came to run a conference in Windhoek, the country���s capital, called “Museum Conversations.” The conference concluded a series of regional meetings with key stakeholders in the museums sector from around Africa and Europe. In the opening speech, the director Daniel Stoevesandt explained that Goethe-Institut is positioning itself as a facilitator on the continent, creating connections between regional stakeholders and players in the field.

Suzana Sousa of Angola, Ciraj Rasool of South Africa, Nina Katangana of Namibia. Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).

Suzana Sousa of Angola, Ciraj Rasool of South Africa, Nina Katangana of Namibia. Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).“Museum Conversations” included a range of voices from around the continent. Prominent scholars in the museum sector, such as George Abungu from Kenya and Ciraj Rassool from South Africa, advocated for the need to urgently address the histories of violence in the museum in order to shape the museum of the future. Veteran educator and activist Mandy Sanger from the District Six Museum in Cape Town spoke about how hierarchies of suffering and trauma are used as currency in these conversations. Others, like Wandile Kasibe of IZIKO Museums of South Africa, likened museums to crime scenes, highlighting the complicity of museums in maintaining the silences of the crimes committed during the colonial period, including theft, murder, and genocide.

So how are European museums addressing the question of return, restitution, and repatriation? For the most part, not very well. From personal experience, in attending many of these kinds of forums, the return or repatriation discussion is still framed as a ���debate��� and I get the sense from colleague-elders that these ���debates��� have been going on for a very long time. To quote the title of a text by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang: ���Decolonization is not a metaphor.��� It is time to move from talk to action.

Audience member at the “Museum Conversations” in Windhoek, Namibia. Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).

Audience member at the “Museum Conversations” in Windhoek, Namibia. Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).Here is an example, involving the German return of Namibian artifacts, that treats decolonization as a metaphor. Facilitated by the Museums Association of Namibia, 20 objects will soon be returned from a German museum with conditions: 1) the objects are initially loaned for a three-year period after which the Namibians can apply for a permanent loan; and 2) the Namibian government must fund the return of the objects in addition to other costs involved, like the process of cleaning the artifacts���removing the poisons and toxins used by conservators to preserve them for posterity. The German government claims that the loans system is a way to bypass German laws around ownership. Some others have argued that the artifacts of African origin have an entangled and shared heritage as they now belong to both Europe and Africa. But this a shared history based on violence and theft. Can one really claim ownership of something that was stolen?

The question of human remains and cultural material held in European ethnographic museums is also a question of the largely devastating afterlives of European colonial rule. The extractive nature of colonialism meant that European nations could build their countries��� wealth through the extraction of culture, resources and people from Africa. Colonialism enforces displacement, and while the period of formal European colonialism has ended in Africa, coloniality persists. As Walter Mignolo argues, coloniality ���is the continuing hidden process of expropriation, exploitation, pollution, and corruption that underlies the narrative of modernity, as promoted by institutions and actors belonging to corporations, industrialized nation-states, museums, and research institutions.���

Goodman Gwasira of UNAM. Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).

Goodman Gwasira of UNAM. Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).The issue at hand also seems to be that European Museums as instruments of the state suffer from what Anne Laura Stoler calls colonial aphasia������In aphasia, an occlusion of knowledge is the issue. It is not a matter of ignorance or absence.���

We cannot keep having debates for the next 50 years. We need strategic intervention. A more productive use of the time for museum professionals in Germany for example would be to lobby the government to create policy to speed up the returns process. In September 2019, B��n��dicte Savoy, who together with Felwine Sarr authored the report commissioned by Emanuel Macron: Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain, has, with others, set up the appeal�����Open Museums Inventories of��African��Artifacts.��� It relates to the��German context and demands that public museums and authorities in charge in Germany:

��� make the inventories of African objects in their respective collections available��worldwide as quickly as possible, regardless of the degree of completeness or supposed perfection of these inventories. Simple scans and lists are sufficient. We need them now. Only then can the��dialogue begin.

Ciraj Rasool of UWC. Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).

Ciraj Rasool of UWC. Image credit Goethe Institute, Johannesburg (CC).That dialogue should then be one that focuses on how Europeans can return objects in a way that respects their original purposes (sometimes spiritual or ritual) and without putting the burden of that labor on Africans. It should also be one that asks not whether African museums have the conditions to preserve and exhibit such objects but, rather, how to create spaces that don���t operate with colonial logics.

As Namibian scholar and artist, Memory Biwa asks: ���Are there other spaces that we can create where communities themselves can narrate histories of objects?���

November 11, 2019

Tunisia’s surveillance state

Tunis, Tunisia. Image credit

Stephen Downes via Flickr CC.

Tunisia is often heralded as an anomaly of the 2011 Arab uprisings, with commentators pointing to the country���s political stability and the country���s progress on liberalization. There are some discordant notes���Sofia Barbarani, a journalist with Aljazeera recently shared her sober assessment of Tunisia���s economic problems, such as high food prices and unemployment���that the positive assessments miss. Yet, hidden beneath the progress are legal and extralegal measures that have increasingly restricted freedom of movement and obtruded people���s privacy.

In 2013, the Tunisian government enacted S17, a 17-part national program to control the Tunisian border and combat terrorism that was clandestinely applied and later challenged. The program arbitrarily restricts Tunisians��� freedom of movement in the name of preventing terrorism. In January 2018, the Tunisian Ministry of Interior said that under S17 it had prevented 29,450 people from traveling to internal conflict areas. In October 2018, Amnesty International reported that its research identified at least 60 people were also banned from traveling abroad under the program. The government���s justification: that movement bans would curtail the ability of Tunisians to join ISIS (an approximately 7,000 Tunisians are estimated to have joined ISIS since December 2015). The illuminating Amnesty report unveils what we already know: counterterrorist measures are expansive for governments and restrictive for individuals. By the end of 2018, S17 did not go unnoticed by Tunisian judiciary and legislative bodies. One Tunisian judge declared S17 unlawful and the Tunisia House of Representatives drafted a law to overturn it.

The S17 program is part of a number of Tunisian government initiatives to ���increase security.��� In the spring of 2012, the Tunisian government created the National Intelligence Agency (ANR). By late November 2014, the government had also set up a new military intelligence agency called Agence des Renseignements et de la S��curit�� pour la D��fense (ARSD) working under the authority of the Ministry of Defense. Also in 2014, former President Mehdi Jom��a established a new security and judicial center as part of a broader project for the Security Counter Terrorism, to oppose terrorism and money laundering. Over the past several years, the United States and Germany have contributed $25 million and $41 million, respectively, to surveillance technologies including mobile observation and securitization of the Tunisian-Libyan border. As the Associated Press noted in 2017, German politicians are polarized about the use of this surveillance technology because of the implications it has for preventing migration. Nevertheless, the Tunisian Ministry of Interior is directly receiving funds and equipment from two major industrialized nations to carry out the surveillance technology along the Libyan border and the Mediterranean Sea.

In light of the global war on terror, Tunisia���s proximity to Libya, and Tunisia���s position as a non-voting member of NATO, national security has also been aligned with new and increased surveillance. Tunisia became a non-voting member of NATO in 2015, contributing to a military alliance between NATO and Tunisia: the Tunisian navy and naval forces of various NATO countries engage in joint exercises. However, this liaison deepened when the Tunisian National Security Council and NATO proposed to create an intelligence fusion center in late 2016.

As Tunisia has transitioned from an authoritarian police state towards a more democratic civil society, it has replaced the old regime���s military intelligence apparatus with a new system. Prior to 2011, radar and security cameras were used by then Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to monitor people���s movements. One of the many sources that has documented this is Wikileaks. In September 2013, their collection of ���Spy Files��� demonstrated how 92 global intelligence contractors sold surveillance systems throughout the world. Unsurprisingly, authoritarian regimes were not immune to using and abusing surveillance technology. What was surprising was that most surveillance corporations were in the Global North while their clients were in the Global South. One particular company that profited under the Ben Ali regime was the German outfit ATIS Huer. Founded in 1946 and based outside of Frankfurt, the corporation specializes in voice and data surveillance with a system named 100 Klarios��. As early as 2013, 80% of the German company���s 100 Klarios�� had monitoring centers in the Middle East and Africa. In Tunisia, the Klarios system was deployed in Alcatel and Tunisie Telecom as early as 1998 and had been collecting voices since 2005.

Today, Ben Ali���s authoritarian regime has not been dismantled, rather, the security apparatus has been integrated into the new parliamentary system. Since 2016, the Tunisian government has installed 1000 surveillance cameras and 300 electronic checkpoints in the capital city. Mass surveillance is an intricate and complex phenomenon, ranging from predictive policing and individually designed advertising to facial recognition. Closed circuit television (CCTV) has become incorporated in cities such as London and New York City as have the debates about the extent to which people are monitored. However, little is said in the western media about the growing cases of camera and data collection outside of North America and Europe, even though people of Muslim heritage and Arab/North African descent are often targeted in the West by those technologies.

This technology is incrementally and unknowingly creeping into people���s lives without their knowledge. When I corresponded online in July 2019 with Farah, a 30-year-old Tunisian researcher, she told me about what the security state was like during her childhood. ���I remember before the revolution, you could hear your own voice echoing during phonecalls.��� For Farah, the transition in Tunisia from an authoritarian police state towards a democratic civil state has not proceeded smoothly since increased surveillance measures have undermined the initial spirit of the 2010-2011 Arab uprisings. She fears that the evolution of Tunisia���s surveillance state contradicts the democratic principles that she and her friends fought for.

This expansion of surveillance programs is not unique but has also included contracts with European telecommunication companies, such as Trovicor (Germany) and Sundby (Denmark) as Privacy International documented. Even with the transition from an authoritarian state to a more parliamentary structure, the incoming government has extended existing contracts.

The Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Defense have had budget increases since 2014, far more than their budgets were under Ben Ali. This increase is partially to do with the increase in personnel and the increase in salary; it is not clear how much they are spending on new equipment. Given that there is still grave unemployment and economic issues in the country, the increased military budget is concerning because that money could be used for social and job programs.